Abstract

This article constellates N.K Jemisin’s The Broken Earth trilogy with decolonial epistemologies to push the boundaries of storied curricula and explore how we come to know. I argue that the imaginative world-building of science fiction can serve as worlding stories—not wording stories—that act, move, and connect knowledge, reader/listener, and writer/teller in ways that interrupt modern/colonial logics and invite otherwise orientations to teaching, learning, and knowledge. Worlding stories center dynamic, living, moving, changing relationships between text, reader, writer, and world. Using language “to world” is thus fundamentally different from using language in order “to word,” a move that modernity/coloniality relies on to categorize reality into objective, separate, fixed boxes. In order to discuss science fiction as worlding stories and therefore decolonial curriculum, I first situate speculative fiction within epistemologies that embrace what is invisible, intangible, imagined, and alien. I then present worlding stories as theoretical framework and methodology. To use language “to world” in this article, I tell a worlding story of my own. After the telling, I discuss how the The Broken Earth danced with decolonial theories to shift my orientation to stories as curriculum. I conclude by emphasizing worlding stories’ epistemological resistance: a relationship between author–reader-text-life that creates space to imagine “the way world ends… for the last time” and “how a new world begins.”

Is it myth or reality? Is it science or folklore? Is it true?

− Hospicing Modernity

You are home. You are safe. … Your paneer curry will be a disaster.

− The Paneer Disaster of 2023

This is the way a new world begins.

− The Stone Sky

Introduction

This article is about the work that stories do. I begin this article by relating together some stories that have done some work in my life.

When I am alone, I surround myself with stories. I happen to live alone, so the buzz of stories around me is almost constant. While brushing my teeth, while cooking, while running errands, while commuting to the Education building where I teach and learn, I am accompanied by the sounds of the stories I borrow on my library-powered free audiobooks app. And as I listen to stories during these minutes and hours of my personal time, I also go looking for stories in my work as a researcher.

Before I worked as a researcher, when I taught U.S. history, I began every class with a request for stories. “Tell me about a time when you took a risk,” I asked, to begin a class about the youth organizers of the East LA Blowouts of 1968. I learned this pedagogical move from my mentor teacher, Sam Texeira, who taught me that relationships are everything when it comes to teaching and learning for social justice. Many relationships were born in my class’s storytelling spaces. My students and I laughed and cried and stayed silent, and, by design, our stories forged relationships between us, our lives and the history content. As a history teacher who taught Sheltered English Immersion classes—classes purposefully and politically comprised of immigrant students who had not yet passed a state-mandated English proficiency test—I was simultaneously a language teacher, a literacy teacher, and a history teacher. So this work was all about stories.

In Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (Citation1932), everyone has a place to belong, pleasure abounds, and this ostensible utopia has successfully eliminated art and history’s power to tell disruptive stories. In that world, a writer working for the world state admits, “Words can be like X-rays if you use them properly—they’ll go through anything. You read and you’re pierced.” When I read these words in Brave New World as a teenager almost twenty years ago, I paused. I wrote them down in neat block letters: “Words are like x-rays … You read and you’re pierced.” I posted these up on my bedroom wall to join other words I had collected and hung up from inspirational texts of my childhood: The Lord of the Rings and the Bible.

I was surrounded by stories back then, too.

The first time I was acutely aware of a book changing my life, the transformation happened on two fronts simultaneously. The magical realist novel 100 años de soledad (Garcia Marquez, Citation1967) and school ethnography Up Against Whiteness: Race, Class, and Immigrant Youth (Lee, Citation2005) changed my life and my orientation to the world at the same time. They both pierced me. I became aware of structures of power shaping our lives, and the ways these structures reached their tentacles into children’s learning and becoming. Surrounded by these stories, I committed myself to teaching and walked into the classroom with a clear political desire to read and rewrite the world with immigrant youth. That’s what happened with that piercing.

In my last year of doctoral coursework, I met with a professor of English to discuss whether I should join his undergraduate Creative Writing seminar. I was starting to become obsessed with the process of writing stories. I was looking for any space where I could write. The professor asked me why, as an ethnographer, I was interested in a fiction writing workshop.

“I don’t see much difference between 100 Years of Solitude and a really good ethnography,” I replied.

When an x-ray pierces you, provided that it is hooked up to the correct machine, something inside you becomes visible that wasn’t visible before.

This article is about another set of books that pierced me, but it doesn’t stop at piercing.

This article imagines that when you are pierced by words, not only is something made visible, but also that thing is made living. This article is about the dancing, transmuting, playing, experimenting, growing together that happens after the piercing.

The piercing, dancing, transmuting words at the heart of this article are written into The Broken Earth trilogy by N.K. Jemisin (Citation2015, Citation2016, Citation2017) and Hospicing Modernity by Vanessa Machado de Oliveira (Citation2021). From the very beginning, both texts concern themselves with worlds and world-endings. “What if,” asks de Oliveira in the preface to Hospicing Modernity, “collective healing will be made possible precisely by facing – together – the end of the world as we know it?” (2021, p. xxv). The first sentence of the first book in the Broken Earth trilogy, The Fifth Season, asks, “Let’s start with the end of the world, why don’t we?” While they begin with world-endings, the two authors also build worlds—emphasis on the plural. They tell stories of worlds that are ending, that must end, and worlds of possibility that are in creation.

This article constellates N.K Jemisin’s The Broken Earth trilogy with Vanessa Machado de Oliveira’s Hospicing Modernity to push the boundaries of storied curricula and explore how we come to know. By experimenting with language, style, and genre, I write myself and these two texts into a tender corner, interrupting modern/colonial logics and inviting otherwise orientations to teaching, learning, and knowledge. That is the work that worlding and world-building stories do. After beginning here by introducing myself as a pierced reader/writer, I go on to claim epistemological space for the multi-genre, multi-voiced, speculative thinking that I engage in and engage with in this article. I then explore the concept of worlding stories in two layers, first by explaining what is meant by worlding stories and then by enacting the work of worlding stories. In between these two explorations of worlding stories, I shift my writing in tone, style, and purpose. The shift is marked by and explained in a methodological note. With my discussion and conclusion, I circle back to knowledge, worlds, The Broken Earth, and the relationships in stories that are powerfully alive and ready to dance with.

The subjunctive epistemologies of visionary fiction

The consideration of what counts as knowledge, the internal logic of what counts as knowledge, and the subsequent categorization of claims based on their proximity to what counts as knowledge is called “epistemology.” This is what makes epistemology a “system of knowing” rather than simply “ways of knowing” (Ladson-Billings, Citation2000, p. 257). The system produces knowledge through logics that naturalize, name, and draw lines around what is deemed to be knowledge. The necessary byproducts of this system of determination are, thus, knowledge and not-knowledge.

Anyone who engages in an educational interaction encounters and reproduces this system of knowledge-distinction or knowledge-production. In formal institutionalized educational settings, the dominant system of knowledge-production relies on concepts like data, evidence, and truth or evaluations like academic, logical, and valid to filter what is deemed to be knowledge. Something must be counted as knowledge in order to be worth teaching or learning. This system of knowledge is a closed, circular system. The system’s foundational concepts like logic, evidence, validity are defined in specific ways according to the standpoints and worldviews of a given sociohistorical context. For example, in the context of contemporary research publications, the definitions of what counts as knowledge, especially knowledge about people, stem from the historical, global system of domination whose purpose was to define who was and was not human in order to promulgate and justify the “spectacular and mundane violence” of colonialism (Fanon, Citation1961; Quijano, Citation2000; Said, Citation1979). Modern colonial structures of power attributed the capacity to create knowledge to certain bodies. Abstract values like knowledge and truth were marshaled to justify raced, linguistic, and gendered supremacy through occupation and exploitation (de Oliveira, Citation2021; Delgado & Stefancic, Citation2003; Lugones, Citation2007).

These dominant epistemologies continue to shape the common-sense ways in which we know what is knowledge and what is not knowledge. To be counted as knowledge within dominant epistemologies, claims must present linearity, generalizability, and genealogy. These claims, vested with the authority given by dominant epistemologies, then become rational-evidence-based-academic-truth-knowledge, and go on to support the farce of universal truth that underlies the story of modernity/coloniality.1Footnote1

I call the demand for objective, categorizable, tangible knowledge a farce because the current system of modernity/coloniality has always already relied on the tricks of invisibility and imagination. These tricks tell a story that makes modernity/coloniality’s requisite death and violence invisible, requiring those who benefit from it to maintain myths in which we are not complicit in harm, that the earth will sustain us, that problems are easy, and that we are separate from other beings (de Oliveira, Citation2021). These denials are how the invisible and the intangible—the violent lines of force that have divided humans into compartments and cast the colonized into the abyss (Fanon, Citation1961)—continue to work at our imagination. Racial capitalism, for example, is always already embedded into the educational systems and institutions that we work in, as one of the axes around which our modern world spins (Ladson-Billings & Tate, Citation1995; Quijano, Citation2000). No one can see axes, yet we know that our planet spins around them. This world is full of world-ending violence, and the structures that keep this broken world together, as-is, are inherently invisible and intangible, and yet no less worth knowing.

I wish to operate in epistemologies that embrace what is invisible, intangible, imagined, and alien. I sometimes call this thinking in the subjunctive mood, reminding myself that the ability to make meaning out of the unreal, the wished-for, the hypothesized, the yet-to-be is already part of our linguistic grammar. I invoke subjunctive thinking in subjunctive spaces where “audience members and artists exist temporarily and, hopefully, strive to enact in the future” (Woods, Citation2021, p. 344). Subjunctive thinking is part of my praxis of the abolitionist imperative to “privilege the necessary over the possible” (Shange, Citation2019, p. 16).

Part of this imperative is to sit in the dark space of death and dying that is always already a part this reality’s structures. Abolitionist, de/anticolonial and critical race scholars remind us of the fatal stakes and the production of death that underlies the modern colonial racial capitalist structure. Ruth Wilson Gilmore (Citation2002) defines racism as “the state-sanctioned and/or extralegal production and exploitation of group-differentiated vulnerabilities to premature death.” Achille Mbembe (Citation2019) points us to the “ways in which, in our contemporary world, weapons are deployed in the interest of maximally destroying persons and creating death-worlds, that is, new and unique forms of social existence in which vast populations are subjected to living conditions that confer upon them the status of the living dead” (p. 92). Michael Dumas (Citation2014) reminds us to return to theorize Black suffering in education, to find meaning in and to give it space to exist, to “imagine the horror of what this must look like, how it must feel. The sound.” (p. 26).

None of these scholars fixate on death as a pessimistic end, but rather acknowledge the reality of what has been otherwise made invisible. In introducing Faces at the Bottom of the Well (1992), Derrick Bell imagines freedom “beyond survival”: “While no one escapes death, those who conquer their dread of it are freed to live more fully … beyond survival lies the potential to perceive more clearly both a reason and the means for further struggle” (Bell, Citation1992, p. 12). Bell closes his book by explaining that to acknowledge racial realism and the permanence of racism is to have “no choice but to accept … our fate. Not that we legitimate the racism of the oppressor. On the contrary, we can only delegitimate it if we can accurately pinpoint it” (Bell, Citation1992, p. 198). To reckon with the abyss of death, and to add to this “imagination, will, and unbelievable strength and courage” is to carry us beyond despair (Bell, Citation1992, p. 198). Abolition’s horizon, decoloniality’s otherwise, and Black Critical Race Theory’s insistence on visibilizing Black futures—these resonate with each other in their practice of subjunctive thinking.

Thinking with and beyond death requires subjunctive thinking—the ability to hold impossibility in our heads and make futures that don’t exist with our hearts and hands. Speculative fiction’s wild imagining is a critical friend in being able to enter and navigate through impossibility. If, as Rita Segato says, the elements of violence are in the very “atmósfera que respiramos” (Segato, R., December 13, 2019), the very air we breathe, then how else can we root out violence than to enter imaginative worlds where no one breathes air at all? What technologies and scyborgs (paperson, Citation2017) might be tooled together in order to stop us from breathing in toxic air? While reading imaginative worlds, we might become curious, feel sparks, and hear resonances with our worlds. In these interactions, we make the impossible a little bit more possible, through our connection with the subjunctive, or what Jose Muñoz (Citation2009) describes as “the anticipatory illumination of art”, the “representational practices helping us to see the not-yet-conscious” of the utopic future (p. 3). adrienne maree brown and Walidah Imarisha begin their anthology of visionary fiction (Citation2015) by naming this alliance between speculative fiction and otherwise imagining:

“Whenever we try to envision a world without war, without violence, without prisons, without capitalism, we are engaging in speculative fiction. All organizing is science fiction. Organizers and activists dedicate their lives to creating and envisioning another world, or many other words - so what better venue for organizers to explore their work than science fiction stories?” (p. 5)

My own ability to think subjunctively was primed by my relationship to the Broken Earth trilogy. The visionary world-building of N.K. Jemisin’s Broken Earth trilogy took my hand and danced with me as I reread the world. I didn’t realize it at the time—didn’t pay attention to how many of my handwritten notes on the margins of critical race theory and decolonial theory texts read simply “Essun”, “Schaffa”, “Alabaster”, “Hoa.” My notes were shorthand references to the meaning I read into the lives, actions, beliefs and narrations of characters in The Broken Earth trilogy. As I experienced my doctoral curriculum, I listened to the trilogy on audiobook repeatedly. During my regular two-hour drives to the airport one semester, I would consider how in the world of The Broken Earth, ideological dehumanizing narratives served to justify a hierarchical and scarcity-driven world system, and I would realize that the trilogy was about critical race theory (Delgado & Stefancic, Citation2003). While cooking dinner during another semester, I would listen to the books’ excerpts from long-lost lore and historical research field notes included at the end of each chapter and think that the trilogy was about the fallible, political, and constructed nature of curriculum (Pinar et al., Citation1994). The next semester, I would listen to Hoa talk to Essun at the end of the series and think that the series was about rememory and the blurring of the boundaries that are imposed on the self and the present (Rhee, Citation2020).

The joke here is that the series is about all of or none of these things. If I were to treat The Broken Earth like a wording story, I would pick one of the analyses about or one of the many other analyses of the trilogy that have run through my head (it’s about the impossibility of being a good teacher, it’s about transnational literacies, it’s about aftermaths of the past in the present, it’s about posthumanism, it’s about land-based rhetorics) and write a paper arguing that this what The Broken Earth is about. I think that task would be impossible for me. Because for me, The Broken Earth is a worlding story: “meaning will change as a worlding story lands deeper into the body, a story will have many layers of changing meaning, and some layers will only reveal themselves years after the story arrives” (de Oliveira, Citation2021, p. 47). The meanings of the Broken Earth’s stories changed, as it worlded, and I changed too.

Wording stories and worlding stories in teacher education

“Books are sometimes windows, offering views of worlds that may be real or imagined, familiar or strange. These windows are also sliding glass doors, and readers have only to walk through in imagination to become part of whatever world has been created or recreated by the author. When lighting conditions are just right, however, a window can also be a mirror” (Sims Bishop, Citation1990).

In Teacher Education classrooms today, the importance of diverse literature on classroom bookshelves often reference the “Mirrors, Windows, and Sliding Glass Doors” framework conceived by Rudine Sims Bishop in 1990. In the introduction to her seminal article, Sims Bishop engages in subjunctive thinking herself, narrating the transmutation of a book into a window, a sliding glass door, a mirror. Mirrors and windows give important information about how something looks. Mirrors can tell you if you look great today, or if you have some yogurt stuck to the corner of your mouth. Windows can show you a beautiful sunset over a parking lot that you initially didn’t think was much to look at. Mirrors and windows are also flat panes. They don’t act, move, or do much except for be looked at or looked through. In contrast, the sliding glass door moves, is moved, invites one to not only move through it but also invites any other being to enter in. And, when the doors are open, new air from a different type of place often blows in to clear the old air out.

More than two decades after Sims Bishop’s article, the framework is more commonly known in literacy education as “Windows and Mirrors.” It is a generative metaphor to engage in conversations about why classroom bookshelves should contain diverse literature representing many different types of people. Within this framework, stories about non-normative people become flat objects that serve as sources of information about oneself (mirror) or Others (windows).

These objective uses of stories are wording stories. Wording stories are the most common ways that we understand the work that stories do. Language is used to define, describe, and inscribe experiences into an informative source. By wording a story, the relationship between writer, story, and reader is transactional. The story which has been worded remains flat. It is not alive and is not expected to shift or change. The story is a stagnant source of information which is to be consumed by the reader. Wording stories serve to make sense of the world from “a secure place of description and prescription” that seek to “wrap the world in a heavy blanket of interpretation” to “convey and confer mastery, authority … or to win a debate” (de Oliveira, Citation2021, p. 46). While describing and interpreting are reasonable intentions for wielding language, the insidiousness of wording the world arises from the way that dominant epistemologies position wording “as the only possible relationship with language, meaning, knowledge—and, consequentially, with the world” (de Oliveira, Citation2021, p. 21, emphasis mine). Wording the world involves “putting everything in the world in boxes that can be labeled, categorized, and described accurately” (p. 21)—which can in turn be efficiently decontextualized, compartmentalized, analyzed, taught, regurgitated, and assessed.

Wording stories are essential and important. The mirrors and windows functions of multicultural literature add diverse sources of information about varieties of life to curriculum. Mirrors and windows also play a role in teacher education. Stories and narrative analysis in teacher education frequently serve as aspirational examples of practice. Reading narratives of critical teachers in action serve as mirrors or windows for critical pedagogs that help them to believe in the operationalizability of critical pedagogies. These accepted roles for stories in critical teacher education are effective because they tap into stories’ use of language to explain concepts and social theories in relatable ways. In other words, stories as explicative tools do much to increase readers’ knowledge of the world, and stories that serve in this role are what de Oliveira (2021) names as “wording stories.”

Wording stories, however, have taken on a position as the singular source of knowledge and teaching within dominant epistemologies. The wording role, where stories become flat objects of stagnant, analyzable, consumable, dead knowledge, is often the only role that stories are cast in within a teacher education curriculum. The continued reliance on wording stories as the singular orientation to the use of stories in teaching and learning ultimately leads to the reproduction of the same logic of modernity/coloniality even within justice-oriented or critical teachers. Everything becomes analyzable and debatable, and transformative imagination that strays too far from the logical becomes not worthy of teaching or learning or thinking about. Wording forecloses the otherwise possibilities of stories.

Worlding stories, in contrast to wording stories, are

“not there to be ‘thought about’, but thought, felt, and danced with and through. They play with the ambivalence and dynamic force of meaning. In this sense, meaning will change as a worlding story lands deeper into the body, a story will have many layers of changing meaning, and some layers will only reveal themselves years after the story arrives. Worlding stories invite us to experiment with a different relationship between language and reality. These stories do not require anyone to believe in anything; rather they invite you to believe with them. However, these stories cannot work on you without your consent. Taking worlding stories seriously makes possible a significant change in your ways of seeing, sensing, and relating to the world” (de Oliveira, Citation2021, p. 45).

I highlight five significant aspects of de Oliveira’s framework of worlding stories here. First, worlding stories are alive—they move, feel, and dance. Importantly, they dance with you, and also serve as a space or a song that moves you to dance. A second fundamental aspect of worlding stories is that they are fluid and multiple. Their meanings are not fixed and instead change in relation with you and in relation to time. Third, worlding stories embody a curious and experimental orientation to the use of language. Fourth, worlding stories, in inviting belief, emphasize a consensual and mutual relationship of authority between the story, the teller, and the listener. Finally, worlding stories open possibilities for transformative, otherwise, previously unseen and unthought-of ways of being. In these five ways, worlding stories differ fundamentally from wording stories’ purposes of describing and explaining by naming and indexing. They center dynamic, living, moving, changing relationships between writer-text-reader-world.

In the “Warm-Up” to Hospicing Modernity (Citation2021), de Oliveira worlds our reality by writing a story about a post-dystopian, hopeful future of 2048. Engaging in visionary fiction writing herself, de Oliveira imagines us on a worldwide conference call in 2048 conferring on how we should educate our children and ourselves. She worlds the near future, inviting us to believe with her: “We will start by recalling significant events that happened in the last three decades. What you will see next is just the text of this presentation; the associated images and videos are now being transferred to your body implants—please blink twice to accept the files” (p. 7). Readers are asked to embody their consent to the story that follows by blinking.

De Oliveira guides readers through a near future that begins in 2018 and extends the violence, inequality, and climate instability of our present to a plausible apocalypse-in-formation that has killed 70% of living beings on the Earth by 2039. Using the second-person “you,” she refuses to let the reader disassociate from the dystopic two decades that follow our present. She also includes us and you and me in a turning point event that reorients humanity: “In 2039, a massive event made us all suddenly recognize the enormous cost of our mistakes. Finally, we could see that we were addicted to arrogance, consumption, and unaccountable autonomy. We realized that we needed mass rehabilitation … we understood … we recognized …” (de Oliveira, Citation2021, p. 8). In other words, something happened, and we somehow learned (realized, understood, recognized) and then changed. The imagined future of the narration closes with an opening that brings readers back to the imagined educational convening in which we blinked to accept de Oliveira’s story: “Today we decide how to do this together, as a planet-wide human and non-human family” (p. 9). From here, de Oliveira returns to the very present moment of the reader, herself, and her book, asking us readers,

“What do you think was the event that made us realize we needed to find another way to (co)exist?”

“What motivated us to keep going on an unsustainable and violent path until 2039?”

“What do you remember wanting most during that time?”

“What did we fail to learn before 2018 that could have prevented the most harmful events of the two decades that followed?”

And,

“Knowing what you know in 2048, if you could go back to 2021, what advice would you give to the people about to face the events that unfolded? … Choose one person and craft a special message for them (p. 9-10).”

This essay is my special message for you.

In the midst of her questioning, de Oliveira asks, “Did you know the answer? How did you come to know?” (2021, p. 9).

I came to know because The Broken Earth was a worlding story that made possible “a significant change in [my] ways of seeing, sensing, and relating to the world” (de Oliveira, Citation2021, p. 47). I write this in response to de Oliveira’s questions as a result of my dancing with The Broken Earth while studying decolonial theories. My special message follows below, after I briefly address my methodological choices about my writing in this essay.

Writing as methodology

By seeking to describe what I understand worlding to mean and how I see it acting in a way that fits into the rhetorical and logical demands of an essay in an academic journal, I worded the concept of the worlding story. I set myself in a genealogy stemming from critical liberatory thinkers, and explained myself, my goals, and the worlding story with as much linearity as I could muster.

The intent of this essay is to explore the pedagogies of science fiction by explaining how The Broken Earth trilogy was a worlding story in my life. In order to accomplish this goal, I must now shift to a different approach to writing and meaning, for speaking of worlding stories invites play and movement away from describing the world through boxing it into a series of definitions. Taking a cue from de Oliveira, I invite you to blink twice to accept the shift.

I am able to shift my writing in this way because I am utilizing a constellating methodology. Constellating is a decolonial methodology of writing about knowledge that privileges how it is inherently embodied and embedded (Powell et al., Citation2014). Invoking the storied nature of constellations in the night sky, my methodology emerges from cultural rhetoricians, who “understand the making of cultures and the practices that call them into being as relational and constellated. All cultural practices are built, shaped, and dismantled based on the encounters people have with one another within and across particular systems of shared belief” (Powell et al., Citation2014). So, culture, meaning, and knowledge are “never built by individuals but is, instead, accumulated through collective practices within specific communities” (Bratta & Powell, Citation2016). Under this constellating epistemology, knowledge is never a static object to be boxed and consumed. Rather, knowledge is active and alive (Bratta and Powell Citation2016). Knowledge is not only seen as dynamic and contextual, but also it is seen as a living mover: knowledge and the cultural practices that generate knowledge work to “create the community; they hold the community together over time even when many of them are no longer practiced day-to-day but are, instead, remembered” (Bratta & Powell, Citation2016).

Here is an example of how knowledge is cultural, alive, creates, and holds community. It is also an example of constellation in action. When I was first learning to make Korean food on my own, far away from my mom’s kitchen, I used to laugh at the incomplete recipes that she sent me. I would ask her how to make a sauce for my favorite mixed noodles, and she would send a list of ingredients followed by numbers. “It’s the ratio,” my mom would say in explanation. To learn to cook the dish, I ultimately needed to try it multiple times. Through repeatedly tasting my own experiments, I ultimately learned how to decipher my mom’s recipe texts and produce my own delicious dishes. I became a translator. I learned that “Sugar” written down in her recipes meant “plum extract” for me. I learned about plum extract from another Korean woman, by watching her cook a different recipe in a Youtube video. I had to ask my mom what plum extract was. “Oh, it’s kind of sweet,” she explained. Curious, I went to the store to buy a bottle and try it out. My mom doesn’t use plum extract in any of her recipes, but I do. I prefer plum extract’s more complex and slightly bitter flavor to replace the role of sugar in recipes. If I were to write down my recipe, undoubtedly someone might ask, “How much plum extract?” I have never measured it. My answer is, “A certain squeeze of the bottle. Not too much – it’s very sweet and it can get bitter.”

My mom wrote down her knowledge on a piece of paper. What she wrote was neither linear nor reproducible. She wrote it in a format that required much from its reader: memory, experiment, movement, taste. Through her composition, not only did I learn, but also my mom’s and my continued relationships with food, flavors, satisfaction, nurturing, and memory interacted. Seen through the demands of dominant epistemologies, it was entirely inadequate as a representation of knowledge. As an enactment of constellating methodology, however, it does a great job of bringing me, my mom, and SeonKyeong Longest’ on Youtube together in a community that creates living cultural knowledge.

Constellating as a writing methodology helps me to further this article, which is about worlding work that stories do. Constellating and worlding both emphasize knowledge as a moving, acting entity. It is this very awareness of knowledge as active, shifting, and capable of creating communities in movement that drives me to reach across disciplines and genres in my reading and my writing. Honoring the ways that knowledge creates communities as it moves, I will move across and within genres, taking up de Oliveira’s invitation to “experiment with a different relationship between language and reality” (2021, p. 45) to approach worlding stories through the telling of a story.

This is a story

The Paneer Disaster of 2023

You’re moving from one thing to the next. The air in the parking lot is sharp and chilly—the crisp spring of a March dusk in Minnesota. It’s Thursday. The workweek vibes are starting to bleed into weekend vibes. You’re almost happy. You and your partner are housesitting for an older friend who has gone on vacation. That house has a great kitchen. You’re heading home for a special weeknight dinner with your fiancé in the Great Kitchen.

But before then. The memory of other Thursdays and the memory of your upcoming weekend jostle for room in your brain as you attempt to swat away the remaining reminders of the work you’ve done today, what remains to be done tomorrow and this month and this season and in the world and the work in general, and your plans for your dinner and your evening and your weekend, your week, your upcoming wedding, your work and your life in general. You carry your thoughts in through the sliding glass doors of the grocery store and step into its comforting fluorescent halls.

You consult the list in the book. This book is your key to wielding the mystical, sensory, nurturing knowledge of other mothers. Instapot Indian Recipes. You walk around the aisles, gathering the requirements listed in the book for tonight’s planned ritual, swatting thoughts as you go.

Cilantro, $2.29, why is cilantro so expensive this week?, swat.

Thai green chilis, you need to send that email to Bill before tomorrow, swat.

Red onions, you can’t wait to get to this house and start cooking, swat.

Nonfat Greek yogurt, what a nice kitchen, this one is nicer than yours at the moment, but a home like this is your future, only a matter of about five to ten years, swat.

Eggs, probably $15. Swat.

Cream of coconut, let’s hope. No one knows with this economy. You’re not really on track to buy a home if you’re talking actual salary, savings, and down payment numbers, but who says numbers are real? You’re guaranteed a house of your own, big deck, separate kitchen and living room, stairs inside the walls of your home, within your lifetime. You’re almost certain.

The looming empty space that is left by that little bit of uncertainty that you feel about this guaranteed future home with a nice kitchen—you just fill that in with other thoughts that you think and swat away.

In the meantime, this weekend you get to playact house in anticipation of your future. Instapot Indian Recipes.

You are home. You are safe. The barrage of others is less relevant once you enter the familiar confines of your home. You follow a routine once you enter your home. Shoes off in the doorway. Coat tossed on to the back of a chair. Your cat appears.

You open your computer to finish writing some emails. You open and close some tabs.

You start cooking.

The recipe book lies open on the counter along with your knife, cutting board, and vegetables.

You have never made this dish before; you did not grow up eating this dish. Instapot Indian Recipes has given you access to the knowledge and opportunity to indulge in paneer curry in your own home.

You chop the vegetables and sauté them in your Instapot.

You smell the aromatics giving off their flavor and watch the colors change.

You spoon in the requisite spices.

You look down at the book. “One can of coconut cream.”

You grab a can opener to open the coconut cream.

The open can slips in your hands and a little bit of coconut cream spills out. The coconut cream is sticky and thick between your fingers.

You look down at it and frown. This cream is so sticky, you think, it’s got to be full of sugar.

You taste some and confirm that the white liquid is indeed, sickly sweet. This? An entire half-can?

You hesitate. Your mind rifles through memories of other North Indian curries you have eaten in your life—sweet was not their dominant flavor profile.

You hesitate.

You read the recipe: canned coconut cream.

You read the label on the can: cream of coconut.

You tip the can into the Instapot.

Your paneer curry will be a disaster. There are 1,189 grams of sugar in your paneer curry.

Everybody makes mistakes.

Discussion

I am reading Hospicing Modernity with my dear friend Noah. We both work with youth, seeking the healing power of stories. As long-time friends who live in different states, we read chapters and come together online to connect with each other and with this book that we both encountered through our different work (me through a course syllabus; he through an artist friend). After each reading the Warm-Up chapter that contained the book’s first worlding story, Noah and I met on Zoom. As could be imagined when two friends first meet up, we caught up on how our weeks were going. Noah told me about the very bad paneer curry that he made the night before. It was inedible.

The worst thing about it, said Noah, is that he knew something was wrong with that coconut cream. (. Coconut milk is different from cream of coconut). He felt it between his fingers. He tasted it himself and it felt very wrong. He also knew how to read and follow recipes written in a book. Faced with these two types of knowledge—the kind of knowledge he felt sticking to his fingers, lingeringly cloying in his mouth, suggesting that it was not meant to be eaten, versus the written instruction to put the can of coconut cream into the Instapot—he relied on the list of steps written in text ().

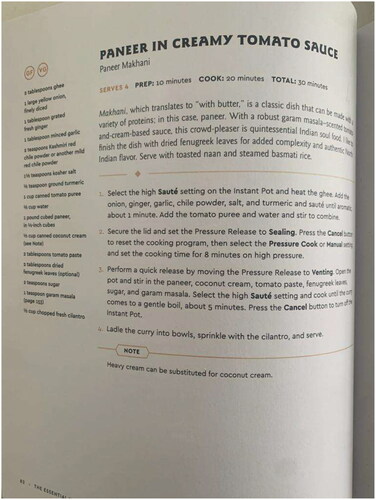

Figure 1. Cream of coconut (left, a sweetened blend of coconut and water used to make tiki cocktails such as Piña Coladas and Painkillers) and coconut cream (right, a blend of shredded coconut and water).

Figure 2. The recipe for paneer in creamy tomato sauce, including ½ cup canned coconut cream stirred into the pot.

To learn to make the paneer is to learn to follow this list of steps.

The presence of this recipe in the book is saying that this is how to learn to make paneer curry in the instapot. To create paneer curry is to follow the text.

As a literate person, to follow the steps and follow the text is to know and to be skilled.

In her worlding story, De Oliveira (Citation2021) asked her readers, “What is the event that made us realize we needed to stop and change (p. 9)?” If it is not touching the sickly sweet liquid in your fingers and tasting it to be wrongly sweet, how powerful is the written text and the agreed upon list of steps?

What types of knowing do we rely upon as the default, unquestioned ways of knowing, so much so that we end up following them even as we have seen, tasted, felt, and known them to be wrong? How does this epistemological dominance stop us from stopping, recognizing, understanding, changing the structures that produce death in our reality? What does it really take to decolonize, and as educators, how does our orientation to knowing open possibilities for people rather than produce cracked people?

Yes, Noah told me that story. Or he didn’t. Noah didn’t pick the wrong coconut can and make a terrible curry in order to make a point about dominant epistemologies and their impact on literacy and knowledge. Coco Lopez didn’t make a sugar-filled fabrication and call it “cream of coconut” to make a point about modernity and the mimicry-based harm of canning. I wrote a parable that presents two competing types of knowledge, how all the time we are making choices about which knowledge matters. These choices have stakes.

Further, as my response to de Oliveira’s questions “what motivated us to keep going on an unsustainable and violent path until 2039?” and “what did we fail to learn before 2018 that could have prevented the most harmful events of the two decades that followed? (p. 8)” this parable specifically points to the nature of text-based, school-taught, alphabetic and academic literacy (the steps in the recipe book) as a misleadingly convincing path toward a guarantee that doesn’t taste very good in the end. In the meantime, on this guaranteed path toward a sweet disaster, notions of valuable knowledge as easy-to-follow progressions in alphabetic, formally written text may cause us to ignore very overwhelmingly obvious evidence that something is wrong and this is not meant to be (the sticky white cream in your hand).

I heard and wrote The Paneer Disaster of 2023 because I was in a subjunctive space of possibility and interpretation already, primed by living simultaneously in this world and in the world of The Broken Earth. As my classmates referred to Sylvia Wynter’s theories of man, race, and culture, I thought about how Stone Lore, a manmade invention, turned into a common-sense awareness of orogenes as monsters and the subsequent dehumanization, discrimination and murder of orogenes. As I read Said (Citation1979)’s arguments about the intricate ties between colonialism, the production of knowledge, and the production of subjectivities, I thought about the history of the Fulcrum School and its creation by the Sanzed Empire as a way of producing orogene subjectivity: “Tell them there is a standard for acceptance; that standard is simply perfection. They will break themselves striving for what they will never achieve” and they will “collaborate in their own internment” (Jemisin, Citation2015, Citation2017). The structure of the Sanzed Empire and its control over the subjectivity, authority, labor, and reproduction of the Stillness manifested as a concrete accompaniment to Quijano’s patterns of coloniality (Citation2000). The invisible nature of knowledge production through Stone Lore, common sense, and the Fulcrum curriculum tied together a connection between coloniality, racialization, and schooling. The way that Nassun and Ykka used magic came to mind as I read about indigenous epistemologies such mindbodyspiritemotion knowledge (Cajete, 2004) and the knowledge generated with and through the land in land-based pedagogy (Rios, Citation2015; Simpson, Citation2014). Seeing through Essun’s eyes, I discovered with Essun how much we didn’t know about the magic of the world when we took the Fulcrum’s definition of orogenic ability for granted. As I researched transnational, translanguaging, hybrid literacies with immigrant children and taught future ESL teachers in their methods requirement, I tried to bring Essun’s realization into the classroom: “Maybe she couldn’t shift a pebble because who the rust needs to shift pebbles? That’s the Fulcrum’s way of testing precision. Ykka’s way is to simply be precise, where it is practical to do so. Maybe she failed your tests because they were the wrong tests” (Jemisin, Citation2016).

I danced between Jemisin’s world, Quijano’s world, Simpson’s world, Said’s world, Noah’s world, my world, as I shifted my awareness of structures of power, the production of knowledge, and the storying role of curriculum, pedagogy. I am aware of this dance, of how Essun, Howha, Alabaster, Schaffa, Nassun have peppered the margins of my notes, my books, and my memos as I have made sense of my world and my role in education over the past two years. And as I read Hospicing Modernity’s warm up and considered again why dystopic futures ring so true to the current state of this world, Noah told me about his bad dinner the night before. The Paneer Disaster of 2023 was born out of the movements that The Broken Earth made in my worldview.

You, and me, worlding

Here, at the end, I turn to explicitly discuss relationships that are part of the worlding and world-building stories. To world together is to speculate together is to know together is to create otherwise worlds together.

The relationship between the storyteller and the listener is something that Shawn Wilson (Citation2008) pointed out to me in Research is Ceremony. “The direct relationship between the storyteller and the listener” is important and salient in Indigenous epistemology, and so is explicitly allowing the roles of both “in shaping both the content and the process,” which allows for patience and consent as ideas are developed and explained in context (p. 8–9). This is a profound description of what stories do and how they do it. Storytelling and worlding opens possibilities of a relationship between the reader and listener.

In The Broken Earth trilogy, Jemisin engages in this relationship building on two levels. Much of the story is told in the second person. The narrator speaks the entire contents of the novel to a You, the main character in the story. The world is revealed by You experiencing, learning, doing, thinking. The entire world of The Broken Earth is an oral story told for a specific, profoundly educational purpose. The narrator says, “I have told you this story, primed what remains of you, to retain as much as possible of who you were. Not to force you into a particular shape, mind you. From here on, you may become whomever you wish. It’s just that you need to know where you’ve come from to know where you’re going. Do you understand?” (Jemisin, Citation2017). To fulfill his purpose of shaping his listener, the narrator builds a world and fills it with the lives and stories of other people across eons, some whose worlds ended to begin the current world of the trilogy and some whose worlds ended just days ago. The narrator repeatedly explains to his listener-reader, his You, that the internal worlds, travails, intentions, experiences of these other people are “part of you.” The narrator educates by building a world for their listener-reader, telling one, long, massive story—to You. As readers, we learn about this world as witnesses to the narrator telling You a story, to form You, to let You know that You are part of many others, and You are tied to a grander scale of existence, time, and space. The narrator teaches You about the world. This two-layered storytelling also means that Jemisin, the author, has written this series to us, her readers. She has taught us about her worlds. When Jemisin told me this worlding story, the story moved around in me so much, convinced me so well of its truth, that what truth meant to me began to change. She taught me about the world and who I am. I am You. We are You.

Conclusion

I have written about my shifting orientation to knowledge as I danced with The Broken Earth and Hospicing Modernity, illustrating one way in which the Broken Earth trilogy visited my world and moved me toward a significant shift in my orientation to knowledge. Put another way, this worlding story animated and embodied theories, breathing life into theories that were lying on a page and walking them over to pierce me right in the heart. Ultimately, this essay is a testament to the moving work that worlding stories do, and here I have crafted a worlding story of my own in an attempt to constellate, or connect, within and across disciplines in order to world my relationship to The Broken Earth trilogy and its pedagogical work in my life. This article is an offering to honor the relationship that has been created between theorists, authors, writers, readers, tellers, readers.

Through the ability to contextualize, and through the establishment of an explicit, mutual, consensual relationship between the teller/writer/listener/reader, stories that seek to world can create beings that make you want to “leap into the air and whoop for joy” (Jemisin, Citation2017). The contextualizing nature of world-building, in addition to the relationship that is explicitly built within the teller and listener can imagine versions of ourselves who, to paraphrase de Oliveira (Citation2021), care for rather than compete with, who plant, who abolish, who heal, who “own up, sober up, clean up, grow up, show up, and exist differently” (p. 8).

Worlding stories can allow for understanding in full context, without abbreviating, referencing others, or squeezing oneself into boxes that don’t fit. To shape the one he loved with a sense of her full humanity, Houwha relied on a long tale that encompassed tens of thousands of years—the contents of which fit into a trilogy of novels. The size of the trilogy reflects perhaps the size of the impact that a commitment to knowledge-as-shaping, knowledge-as-relational, knowledge-as-co-imagining could make on curriculum deliberation and teacher education. As a storyteller here in this article, I have included many of my own stories, too, constellating my life and my loved ones’ lives together in this exploration of the relational, visionary, transformative, living nature of worlding and world-building stories.

Thomas King writes in “The Truth About Stories” (2006) that origin stories explain what the world is composed of, how those components are related, and how the people who tell and listen to them understand what the world is about. If origin stories explain what the world is really composed of and how it came to be composed that way, then Jemisin’s dystopian future story is an invitation to understand our world and imagine “the way a new world begins” (Jemisin, Citation2017). Another world begins, as the Broken Earth series illustrates, with a lengthy, complex, brutal, beautiful, ongoing ending of the current world.

In its worlding, the storytelling refuses to deny the ways in which we are entangled in each other. “I am you,” Houwha tells his listener, his love. “You are me.” (Jemisin, Citation2017).

In its worlding, the storytelling refuses to deny the deeply complex historical magnitude of the current failing system. The Broken Earth’s brokenness reaches back to over 40,000 years before Essun’s time, to before the shattering that began the fifth seasons that mark the regular apocalyses of this world.

In its worlding, the storytelling refuses to deny everyone’s complicity in the atrocities of the system. Even our hero, Essun, leaves Castrima knowing that Ykka must ultimately recreate the atrocity of the node-maintainers system at least a few more times.

In its worlding, the storytelling refuses to deny that the earth is an entity with a finite ability to sustain. “The earth is ALIVE!” reveals Alabaster (Jemisin, Citation2016). The Earth is alive, has an agenda, is pissed, and has a long memory.

In its worlding, the storytelling refuses to deny that for some people, the world ends over and over again, because the structures of the world depend on the death of those who have been storied to become “vulnerable to premature death” (Gilmore, Citation2002, p. 262).Footnote2

In worlding The Broken Earth trilogy, Jemisin dares to imagine “the way world ends - for the last time” (Jemisin, Citation2015). By doing so, The Broken Earth is “rescuing hope from the cages of projections into the future and enabling it to weave relationships and movements in the present—the very texture that futures are made of” (de Oliveira, p. 45). It is these futures that our stories must work toward, and it is this worlding hope that makes The Broken Earth trilogy a powerful friend.

Acknowledgment

The author would like to acknowledge Dr. Alex Allweiss, Dr. Sandro Barros, Dr. Kristin Arola, Dr. Jungmin Kwon, Bri Markoff, and candace moore for their thoughtful comments, guidance, and support.

Disclosure statement

The author declares no interests that compete or conflict with the writing of this article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Christine Seon “Sol” Rheem

Christine Seon Sol Rheem is an immigrant daughter of an immigrant mom who grew up crossing borders between worlds of multiple stories. She is a former history and English language teacher who studies stories that immigrants tell, how they tell them, and the spaces where they are told. She is currently a PhD Candidate in the Department of Curriculum, Instruction, and Teacher Education at Michigan State University.

Notes

1 De Oliveira uses the terms modernity/coloniality together to reinforce the notion that “modernity cannot exist without expropriation, extraction, exploitation, militarization, dispossession, destitution, genocides, and ecocides” (2021, p. 18). In other words, our current state is inextricable from violent systems of racial capitalism and colonialism.

2 These refusals are framed as “refusals to deny” in response to what De Oliveira has named “The Four Constituve Denials of Modernity/Coloniality” in Hospicing Modernity (2021).

References

- Bell, D. (1992). Faces at the bottom of the well: The permanence of racism BasicBooks.

- Bratta, P., & Powell, M. (2016). Introduction to special issue: Entering the cultural rhetorics conversations. Enculturation: A Journal of Rhetoric, Writing, and Culture, 21 http://enculturation.net/entering-the-cultural-rhetorics-conversations.

- Brown, A. M., & Imarisha, W. (2015). Octavia’s Brood: Science fiction stories from social justice movements. AK Press.

- Chang, E. Y. (2021). Imagining Asianfuturism(s). American Studies, 60(3-4), 159–162. https://doi.org/10.1353/ams.2021.0043

- De Freitas, E., & Truman, S. E. (2021). New Empiricisms in the Anthropocene: Thinking with speculative fiction about science and social inquiry. Qualitative Inquiry, 27(5), 522–533. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800420943643

- de Oliveira Andreotti, V. (2021). Hospicing modernity: Facing humanity’s wrongs and the implications for social activism North Atlantic Books.

- Delgado, R., Stefancic, J. (2003). Critical race theory: An introduction. http://site.ebrary.com/id/11336407

- Dumas, M. J. (2014). ‘Losing an arm’: Schooling as a site of black suffering. Race Ethnicity and Education, 17(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2013.850412

- Fanon, F. (1961). The wretched of the earth Grove Press.

- Garcia Marquez, G. (1967). 100 años de soledad. Editorial Sudamericana, S.A

- Gilmore, R. W. (2002). P. J. Taylor, R. J. Johnston, & M. J. Watts (Eds.), Race and globalization. Blackwell.

- Grattan, S. (2023). Aesthetics of the fucked. Textual Practice, 37(9), 1388–1404. https://doi.org/10.1080/0950236X.2023.2248795

- Huxley, A. (1932/2010). Brave new world (11th ed.) Vintage.

- Jemisin, N. K. (2015). The Fifth Season. Orbit.

- Jemisin, N. K. (2016). The Obelisk Gate. Orbit.

- Jemisin, N. K. (2017). The Stone Sky. Orbit.

- King, T. (2003). “You’ll Never Believe What Happened” is always a great way to start. In The Truth about Stories: A Native Narrative. Harper Collins.

- Ladson-Billings, G. (2000). Racialized discourses and ethnic epistemologies. In N. K. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed.) SAGE.

- Ladson-Billings, G., & Tate, W. F. (1995). Toward a critical race theory of education. Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education, 97(1), 47–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146819509700104

- Lee, R. Y. (2023). A new geological (R)age: Orogeny, anger, and the anthropocene in N.K. Jemisin’s the fifth season. Science Fiction Studies, 50(3), 321–345. https://doi.org/10.1353/sfs.2023.a910324

- Lee, S. J. (2005). Up against whiteness: Race, school, and immigrant youth Teacher’s College Press.

- Lugones, M. (2007). Heterosexualism and the colonial/modern gender system. Hypatia, 22(1), 186–209. https://doi.org/10.1353/hyp.2006.0067

- Mbembe, A. (2019). Necropolitics Duke University Press.

- Morvay, J. K. (2021). Learning response-ability: What the broken earth can teach about crafting a Chthulucene. Journal of Curriculum and Pedagogy, 18(2), 154–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/15505170.2021.1920517

- Muñoz, J. E. (2009). Cruising Utopia: The then and there of queer futurity New York University Press.

- Palma, T. (2019, December 13) Rita Segato: La Antropóloga Que Inspiró a Las Tesis. La Tercera,

- Paperson, l. (2017). A third university is possible. University of Minnesota Press.

- Pinar, W. F., Reynolds, W. M., Slattery, P., & Taubman, P. M. (1994). Understanding curriculum: An introduction to the study of historical and contemporary curriculum discourses. Peter Lang.

- Powell, M., Levy, D., Riley-Mukavetz, A., Brooks-Gillies, M., Novotny, M., & Fisch-Ferguson, J. (2014). Our story begins here: Constellating cultural rhetorics. Enculturation: A Journal of Rhetoric, Writing, and Culture, 17(1). http://enculturation.net/our-story-begins-here.

- Quijano, A. (2000). Coloniality of power: Eurocentrism and Latin America. Nepantla: Views from the South, 1(3), 533.

- Rhee, J. (2020). Decolonial feminist research: Haunting, rememory and mothers (1st ed.) Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429273933

- Rios, G. (2015). Cultivating land-based literacies and rhetorics. Literacy in Composition Studies, 3(1), 60–70. https://doi.org/10.21623/1.3.1.4

- Said, E. (1979). Orientalism. Knopf.

- Shange, S. (2019). Progressive dystopia: Abolition, antiblackness, + schooling in San Francisco. Duke University Press.

- Simpson, L. B. (2014). Land as pedagogy: Nishnaabeg intelligence and rebellious transformation. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 3(3), 1–25.

- Sims Bishop, R. (1990). Mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors. Perspectives: Choosing and Using Books for the Classroom, 6(3).

- Wilson, S. (2008). Research is ceremony: Indigenous research methods. Fernwood Publishing.

- Woods, P. J. (2021). The aesthetic pedagogies of DIY music. Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies, 43(4), 338–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714413.2020.1830663