Abstract

The EU Cosmetic Products Regulation requires neither environmental data nor environmental risk assessment for individual ingredients or finished cosmetic products. Instead, it relies on REACH to address environmental risks linked to cosmetic ingredients, including preservatives. We investigated how the environmental risks of cosmetic preservatives are managed by REACH. We identified preservatives of environmental concern and examined if any of these had been selected for Substance Evaluation, proposed for or identified as an SVHC, required authorization or were proposed for, or subject to, restriction under REACH. More than half of the preservatives approved under the Cosmetic Product Regulation, 70 of 137, were identified as being of environmental concern according to the criteria set in this study. Some of the approved preservatives were no longer produced or used in the EU due to their hazardous properties. However, they remained approved and may still enter the EU via the imported products. Our results also indicate that the environmental aspects of cosmetic ingredients, including preservatives, are not efficiently managed by REACH. Besides the known issues in REACH, we identified additional areas in the interface between REACH, CLP and the Cosmetic Products Regulation that call for improvement. Here, we provide practical suggestions in line with the Chemicals Strategy for Sustainability. If implemented, these measures would strengthen the protection of the environment from hazardous cosmetic ingredients.

Introduction

In 2020, the European Commission introduced the Chemicals Strategy for Sustainability, an ambitious plan toward a toxic-free environment ([EC] European Commission Citation2020). One of the specific aims of the strategy is to strengthen the EU chemicals legislation to better protect human health and the environment. To achieve that, the Commission proposed a line of measures, including strengthening requirements across legislations to enable comprehensive environmental risk assessment and addressing regulatory inconsistencies between the different pieces of chemicals legislation through a “one substance, one assessment” approach (EC Citation2020). One such inconsistency concerns substances used as ingredients in cosmetic products and their environmental impact (EC Citation2019).

Cosmetic products are everyday chemical mixtures for consumer use, such as toothpaste, soaps, shampoos, perfumes, and make-up. In the EU, cosmetic products are regulated by a product-specific regulation, the Cosmetic Products Regulation (EC) 1223/2009 ([EPCEU] European Parliament and Council of the European Union 2009). In addition, the substances contained in cosmetic products fall under the two overarching chemicals regulations: Regulation (EC) 1907/2006 concerning the Registration, Evaluation, Authorization and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) and Regulation (EC) 1272/2008 on Classification, Labeling and Packaging (CLP). More detailed information about REACH, the CLP, and their processes is available in Supplementary materials.

The Cosmetic Products Regulation applies to finished cosmetic products and aims at ensuring their safety for human health. This is achieved through a general prohibition of the use of substances with carcinogenic, mutagenic, or reprotoxic (CMR) properties in cosmetic products. Further, the use of other substances harmful to human health may be restricted or prohibited under Annex II and III to the Cosmetic Products Regulation. In addition, cosmetic ingredients used as UV filters, colorants, and preservatives require a safety assessment by the Scientific Committee for Consumer Safety (SCCS) and approval by the European Commission. Only the approved UV filters, colorants, and preservatives may be used in cosmetic products. The safety of the remaining ingredients is evaluated together with the safety of the finished product by the manufacturers or distributors in a so-called cosmetic product safety report. The report includes information about the composition of the product, intended uses, exposure assessment, and toxicological information on the ingredients. The report is not reviewed by, or submitted to, the authorities but should be made available upon request (EPCEU Citation2009).

The above measures only focus on the protection of human health. The Cosmetic Products Regulation requires neither environmental data nor environmental risk assessment for individual ingredients or finished products (EPCEU Citation2009). For example, preservatives, i.e. substances with antimicrobial properties used to prolong the shelf-life of finished cosmetic products, are not evaluated for their environmental properties (EPCEU Citation2009; EC Citation2018, Citation2023). This is despite their potential to negatively impact aquatic systems if emitted into the environment via the wastewater (Nowak-Lange et al. Citation2022; Vale et al. Citation2022). Cosmetic preservatives specifically, have been implicated in being able to affect the aquatic environment and contributing to the development of antimicrobial resistance (Romero et al. Citation2017). In the EU, the environmental hazards of cosmetic ingredients, including preservatives, should be considered through REACH (EPCEU Citation2009). To identify environmentally hazardous substances, REACH (EPCEU Citation2006) provides criteria for persistent, bioaccumulative and toxic (PBT) and very persistent, very bioaccumulative (vPvB) properties. Substances identified as PBT/vPvB may be selected for Substance Evaluation to clarify whether or not the risks connected to their use are adequately managed. If risk management measures are required, the substance may be identified as a Substance of Very High Concern (SVHC), included on the Candidate List for Authorization, and potentially also on the Authorization List or restricted (EPCEU Citation2006). However, a PBT/vPvB assessment is only performed for substances produced/imported in quantities of 10 tonnes or more per registrant and year (EPCEU Citation2006), which means that substances with potential PBT/vPvB properties in quantities under that limit may remain unidentified.

Classification under the CLP Regulation provides another option to identify environmentally hazardous substances as it sets criteria for substances hazardous to the aquatic environment i.e. Aquatic Acute and Aquatic Chronic (EPCEU 2008). REACH is closely interlinked with the CLP Regulation and risk management tools available under REACH often rely on classifications under the CLP. However, the regulatory obligations under REACH for substances classified as Aquatic Acute/Aquatic Chronic under the CLP Regulation are limited to requirements of additional information and inclusion of exposure assessment and risk characterization into the chemical safety assessment (EPCEU Citation2006). Recently, our new hazard classes were added to the CLP, three of which are environmental. The European Commission is planning to revise REACH to include new data requirements and regulatory obligations to facilitate classification of substances into the new hazard classes and ensure their proper regulation (EC Citation2020). At the time of writing, no timeline for the revision is available.

Since the Cosmetic Products Regulation does not consider the environmental impact of the ingredients or finished products, remitting the management of the environmental hazards to REACH has been identified as a regulatory inconsistency in the fitness check carried out by the European Commission (EC Citation2019). However, according to the fitness check report, the practical significance of this regulatory inconsistency was not possible to determine due to insufficient input from the stakeholders (EC Citation2019). The aim of this study was to investigate how environmental hazards associated with cosmetic preservatives are managed under REACH. To explore this, we investigated if any of the approved cosmetic preservatives were of environmental concern and if so, whether or not they were subjected to Substance Evaluation, SVHC identification, Authorization and Restriction.

Method

Selection of substances

Annex V to the Cosmetic Products Regulation lists all approved cosmetic preservatives and constitutes the scope of substances included in this analysis. An entry in Annex V may contain one or more unique substances. For this study, all substances with unique EC and CAS numbers are regarded as separate, approved cosmetic preservatives, further referred to as cosmetic preservatives.

Data sources and data collection

The European Chemicals Agency’s database was used as the data source (available from: https://echa.europa.eu/sv/information-on-chemicals). The search and data collection was performed using substance identifiers i.e., EC and CAS numbers. The following information was collected for all substances: REACH registration status and tonnage, classification for environmental (aquatic) hazards according to the CLP Regulation, the outcome of the PBT assessment, and the results of the biodegradation screening test in water under REACH. In addition, it was checked whether the cosmetic preservatives had been subjected to Substance Evaluation, identified as an SVHC, or a candidate for authorization or restriction under REACH. All information was organized in an Excel database. The data sources and the type of data collected are presented in . Data were accessed from May 2022 to September 2022.

Table 1. Data sources and type of data collected from the European Chemicals Agency’s database.

Data analysis: identification of cosmetic preservatives of environmental concern and their risk management under REACH

The analysis proceeded in two steps. First, cosmetic preservatives hazardous to the environment were identified. For the purpose of this study, we refer to these substances as cosmetic preservatives of environmental concern. A preservative was considered to be of environmental concern if it fulfilled any of the following criteria:

Classified as Aquatic Acute or Aquatic Chronic of any category under the CLP Regulation by self-classification or harmonized classification

Determined to fulfill the criterion for P in the PBT assessment performed as part of the Chemical Safety Assessment for substances in quantities above 10 tonnes per year under REACH

Determined to be not biodegradable in screening tests for biodegradation in water submitted as part of the REACH dossier. Preservatives for which the results of the ready biodegradation test concluded “under test conditions no biodegradation observed” were regarded as potentially persistent

The criteria were chosen based on available information under the CLP and REACH. CLP identifies substances classified as Aquatic Acute and/or Aquatic Chronic as hazardous to the environment. REACH mandates PBT assessment for substances in quantities above 10 tonnes per year. However, persistence alone has important implications for the behavior of chemicals in the environment (Cousins et al. Citation2019). Therefore, substances meeting the persistence (P) criteria in Annex XIII of REACH were considered to be of environmental concern. In the absence of a full PBT assessment, a 'no biodegradation observed’ result in the ready biodegradation test, submitted in the REACH dossier, was considered as sufficient indication of persistence.

Next, for the identified cosmetic preservatives of environmental concern, we examined if they had been selected for Substance Evaluation, proposed for or identified as an SVHC, required authorization or were proposed for, or subject to, restriction. If so, we considered the justification for, and the regulatory outcome of the inclusion and/or assessment.

Results

Identifying cosmetic preservatives of environmental concern

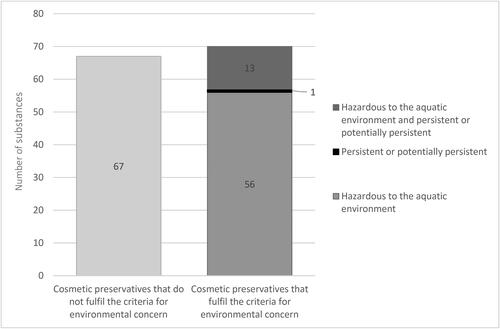

In total, Annex V of the Cosmetic Products Regulation lists 137 unique, approved, cosmetic preservatives. For a full list see Supplementary Table 5. More than half of the approved cosmetic preservatives, 70 of 137, were identified as being of environmental concern (). Of these, 13 fulfilled both the criteria for hazardous to the aquatic environment and persistency/potential persistency criteria, 56 only fulfilled the criterion for aquatic hazard, and one only fulfilled the criterion for persistency/potential persistency.

Figure 1. The number of cosmetic preservatives that are not considered to be of concern (n = 67) and those that fulfill at least one criterion as defined in this study to be considered of environmental concern (n = 70) of the total number of cosmetic preservatives (n = 137). Cosmetic preservatives of environmental concern are comprised of 56 substances that fulfill the criterion of hazardous to the aquatic environment, 1 substance that fulfilled the criterion for persistency or potential persistency, and 13 that fulfilled both of the criteria. More details are available from the Supplementary Table 4.

Registration status and tonnages under REACH

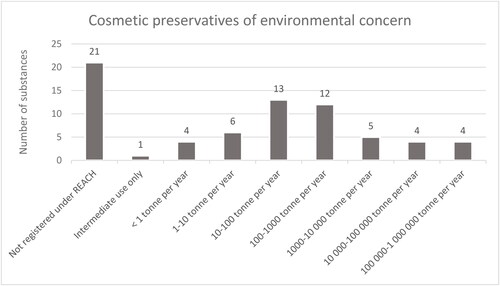

shows the registration status and tonnages of the cosmetic preservatives of environmental concern. Among the 70 cosmetic preservatives of environmental concern, 21 substances were not registered under REACH and thus had no regulatory obligations to provide data or perform an assessment. Since a REACH registration is required for all chemical substances produced or imported in annual quantities of one tonne and above per registrant (EPCEU Citation2006), it can be assumed that the annual quantities of these substances are below one tonne per registrant. Five of the 70 substances did not have any obligations under REACH. One was due to it being registered for intermediate use only and four due to ceased production. Further, six cosmetic preservatives of concern were registered at annual tonnages of less than 10 tonnes per year. For these substances, the PBT assessment was not required.

Figure 2. REACH registration status and total annual tonnage data for the 70 cosmetic preservatives identified as cosmetic preservatives of environmental concern according to the criteria set in this study.

The remaining 38 substances were produced/imported at 10 tonnes or more per year and were subject to PBT assessment. The PBT assessment was not available for eight of the 38 substances, in four cases due to substances being inorganic and thus being exempted from the requirement. In the four remaining cases, the reason for not submitting a PBT assessment was not clear to us.

Substance evaluation under REACH

Among the 49 cosmetic preservatives of environmental concern registered under REACH, six were subjects to Substance Evaluation and are further described below and in . Among those six, three were prioritized for substance evaluation based on environmental concerns as well as human health concerns and one substance was prioritized based on environmental concerns only.

Table 2. Approved cosmetic preservatives subjected to Substance Evaluation under REACH, the initial grounds for concern, and the outcome of the process.

Sodium metabisulphite (EC# 231-673-0, CAS# 7681-57-4) was evaluated in 2014 for the concerns of being CMR, exposure to the environment, exposure of sensitive populations, high aggregated tonnage and wide dispersive use. The Substance Evaluation report concluded that, based on the available hazard data, the substance was not of concern to the environment, and that no further investigation was necessary. The evaluation was concluded with the recommendation for harmonized classification under the CLP Regulations as STOT SE (Specific target organ toxicity, single exposure) category 3 for respiratory tract irritation based on acute toxicity data (Hungarian National Institute of Chemical Safety Citation2015).

The evaluation for Methylparaben (EC# 202-785-7, CAS# 99-76-3) started in 2014 with the initial ground for concern including being CMR, potential endocrine disruptor, being used in consumer products, exposure of sensitive populations, high aggregated tonnage and wide dispersive use. The evaluating Member State Competent Authority has requested further information before a conclusion could be made ([ECHA] European Chemicals Agency 2016c). No conclusion has yet been made.

1-(4-Chlorophenyl)-3-(3,4-dichlorophenyl) urea, also called Triclocarban (EC# 202-924-1, CAS# 101-20-2), was subjected to Substance Evaluation in 2019. The justification included suspected reprotoxic and endocrine disrupting properties and wide dispersive use. In addition to the above, the Substance Evaluation report ([ANSES] French Agency for Food Environmental and Occupational Health and Safety Citation2020) lists microbial resistance and non-approved use as a biocide as additional concerns that required investigation. The report concluded the need for updating the harmonized classification under the CLP with Reprotoxic, based on effects on fertility and developmental effects via lactation. Since there are currently no active registrants, all further follow-up actions have been halted (ANSES Citation2020).

5-Chloro-2-(2,4-dichlorophenoxy) phenol, also called triclosan (EC# 222-182-2, CAS# 3380-34-5) was evaluated in 2012 based on concerns of being a potential endocrine disruptor, suspected PBT/vPvB and high aggregated tonnage. The evaluation resulted in a request for more information (ECHA Citation2014) which was later partially annulled by the Board of Appeal of the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA Citation2016a). No conclusion has yet been made.

1-(4-Chlorophenoxy)-1-(imidazol-1-yl)-3,3-dimethylbutan-2-one, also known as climbazole (EC# 253-775-4, CAS# 38083-17-9) was evaluated in 2014 based on concerns of being CMR, being used in consumer products and wide dispersive use. The evaluation resulted in a request for additional information (ECHA Citation2016b) which was partially annulled by the Board of Appeal of the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA Citation2018) with some information requirements still pending (ECHA Citation2019).

Steartrimonium chloride (EC# 203-929-1, CAS# 112-03-8) was elected for the Substance Evaluation in 2018 based on concerns of being PBT/vPvB, exposure to the environment and wide dispersive use (Istituto Superiore di Sanità Citation2018) but later withdrawn (Istituto Superiore di Sanità Citation2019). The withdrawal was a result of a conclusion by the European Chemicals Agency that several quaternary ammonium compounds, including steartrimonium chloride, were not PBT (Istituto Superiore di Sanità Citation2019) ().

Substances of very high concern and the Candidate List for Authorization

Two of the cosmetic preservatives have been identified as SVHCs and included in the Candidate List for Authorization. Both substances were identified as SVHCs on the basis of human health concerns following REACH article 57(f) ().

Table 3. Cosmetic preservatives of environmental concern identified as substances of very high concern (SVHCs) under REACH, their environmental classification under the CLP Regulation, as well as justification for inclusion in the Candidate List for Authorization.

Gularaldehyde, also known as glutaral (EC# 203-856-5, CAS# 111-30-8) was included on the Candidate List for Authorization in 2021 due to its respiratory-sensitizing properties (ECHA Citation2021a). It was proposed to be included in the Authorization List (ECHA Citation2023a) and currently awaits a decision.

Butyl 4-hydroxybenzoate (EC# 202-318-7, CAS# 94-26-8) was included on the Candidate List for Authorization in 2020 due to its endocrine-disrupting properties (ECHA Citation2020). As of August 2023, the substance has not been recommended for inclusion in the Authorization List.

Restriction under REACH

One approved cosmetic preservative has been restricted under REACH, although it does not have an active registration. The decision on the restriction of phenylmercury acetate (EC#200-532-5, CAS# 62-38-4) was made in 2012 and entered into force in October 2017 (EC Citation2012). The restriction was a consequence of the Community Strategy Concerning Mercury which communicated the need to reduce the levels of mercury in the environment and lower human exposure due to the risks that it poses to human health and the environment (EC Citation2012). The restriction covered the production, placing on the market, and use of phenylmercury as a substance or in mixtures and articles where the concentration of mercury is equal to or greater than 0.01% by weight (EC Citation2012). Regulation (EU) 2017/852 on mercury prohibits several uses of mercury, including the use in cosmetic products other than as a preservative following the conditions laid down by Annex V to the Cosmetic Products Regulation (EPCEU 2017).

According to Annex V to the Cosmetic Products Regulation, the use of phenylmercury acetate and two other mercury-containing preservatives, thiomersal (CAS# 54-64-8, EC# 200-210-4) and phenylmercury benzoate (CAS# 94-43-9, EC# 202-331-8), is allowed in eye products with a maximum concentration of 0.007% for mercury in the final product (EPCEU Citation2009). This means that these substances may continue to be used in cosmetic products since the maximum allowed concentration in the finished product is below the threshold of the restriction under REACH, and due to the exemption from Regulation (EU) 2017/852 on mercury.

Discussion

Environmental risks of cosmetic products or their ingredients are neither assessed or managed under the Cosmetic Products Regulation. Instead, these risks should be considered through REACH. This study aimed to investigate how REACH manages the environmental hazards of the cosmetic preservatives approved under the Cosmetic Products Regulation. The results showed that more than half of the approved cosmetic preservatives were of environmental concern i.e., classified as toxic to the aquatic environment according to the CLP Regulation and/or persistent or potentially persistent according to REACH. This indicates that environmentally hazardous substances may be present in cosmetic products and justifies the need for environmental risk assessment and management to protect the environment.

Substances evaluated under the Substance Evaluation, identified as SVHCs, as well as substances restricted under REACH were also found among the identified cosmetic preservatives of environmental concern. Moreover, one-third of all cosmetic preservatives of environmental concern were not registered under REACH. Based on our results, no clear conclusion could be drawn on the effectiveness of REACH in managing the environmental concerns of cosmetic preservatives. However, our study highlighted several issues regarding the interlinkage between the CLP Regulation, REACH, and the Cosmetic Products Regulation, which may affect the management of cosmetic preservatives of environmental concern.

The presence of a substance on the list of approved cosmetic preservatives is not indicative of the actual use of that substance. One in three preservatives of environmental concern was not registered under REACH, possibly due to the ceased or low production or import. However, keeping substances that are no longer produced or used on the list of approved cosmetic preservatives, is not desirable as this allows for import of products containing these substances into the EU. As an example, triclosan, an approved cosmetic preservative, is widely known for its negative effects on the environment and its ability to contribute to the development of antimicrobial resistance (Carey and McNamara Citation2014; Lu et al. Citation2018; Li et al. Citation2019). Currently, triclosan is no longer produced or imported into the EU, which might have halted the ongoing regulatory efforts, such as its assessment for PBT and endocrine disruptive properties (ECHA Citation2023b). Yet, since the substance remains on the list of approved preservatives, cosmetic products containing triclosan are still allowed to be imported into the EU and placed on the market. The approval of cosmetic preservatives is not legally required to be reevaluated at any regular time interval, and the approval of cosmetic preservatives is not time-limited (EPCEU Citation2009). This may enable substances like triclosan to remain an approved preservative in cosmetic products despite it being identified as having unacceptable properties under other assessment processes.

The REACH and CLP Regulations are central pillars of the chemicals legislation in the EU. However, for environmentally hazardous substances, the interlinkage between the two regulations is incomplete. Since the CLP Regulation itself does not place any regulatory obligations on the classified substances, any risk management measures will depend on other regulations, such as REACH. Under the CLP Regulation, substances that fulfill the criteria for classification as Aquatic Acute/Aquatic Chronic are considered to be environmentally hazardous. Meanwhile, classification as toxic to the aquatic environment under the CLP Regulation on its own is not enough to trigger Substance Evaluation, identification as SVHC, Authorization or Restriction under REACH. The regulatory obligations and risk management measures related to the environment under REACH are triggered only by fulfilling the criteria for PBT/vPvB.

According to the PBT criteria under REACH, the criterion for toxicity (T) may be fulfilled if a substance is hazardous to human health or the environment. For human health hazards, the criterion for toxicity refers to the CLP classification. Thus, the criterion for toxicity (T) is fulfilled if a substance is classified as carcinogenic, mutagenic, reprotoxic or toxic to specific target organ after repeated exposure (STOT RE) under the CLP Regulation. For the environmental hazard, however, the criterion does not refer to the CLP classification. Instead, the criterion is set as long-term no-observed effect concentration (NOEC) or effect concentration (EC10) of less than 0.01 mg/L. The reason for such a difference may lie in the way the criteria for aquatic toxicity under the CLP regulation is set. Under the CLP, the criteria incorporate the degradation properties of the substance. For example, a rapidly degradable substance with NOEC/EC10 of less than 0.01 mg/L may be classified as Aquatic Chronic category 1. However, a non-degradable substance with NOEC/EC10 of 0.1 mg/L may also be classified as Aquatic Chronic category 1. This means that for environmentally hazardous substances, the CLP classification may not automatically be considered as meeting the criterion for T in a PBT assessment.

Consequently, the above may lead to environmental risks connected to substances classified as hazardous to the aquatic environment under the CLP which might be overlooked under REACH. This might especially be the case for substances below 10 tonnes per year, for which PBT assessment is not required. Furthermore, the fact that the environmental classification under the CLP is inadequate for meeting the toxicity criterion (T) in PBT assessment under REACH, puts additional burden on the producers/importers of chemicals to perform two separate assessments.

Additionally, REACH has several known issues that may slow down the regulation of hazardous chemicals. For example, the limited requirements for environmental data for substances in tonnages below 100 tonnes per year have been previously described (Ruden and Hansson 2010). In 2021, the European Chemicals Agency published a report on the operation of the REACH and CLP Regulations (ECHA Citation2021b). The report described several issues concerning the operation and effectiveness of the REACH risk management measures. For example, the request for more information under the Substance Evaluation can only be made if the potential risk of the substance can be demonstrated based on information available in the submitted dossier. This means that it might be difficult to justify the request for more data for substances with lower annual tonnages, for which limited data is required under REACH. Further, it has to be clear that the concerns are severe enough to justify the need for clarification and more information. Finally, there has to be a realistic possibility that the request for information and the clarification of the concerns will lead to improved risk management. The combination of limited hazard information for substances in lower quantities and the difficulties of justifying the request for more, result in low effectiveness of the Substance Evaluation process (ECHA Citation2021b). The report also pointed out the slowness in the identification of SVHCs, authorization and restriction processes, and the low number of substances subject to risk management measures (ECHA Citation2021b).

Recently, as part of the Chemical Strategy for Sustainability, new hazard classes have been added to the CLP Regulation, three of which concern the environment (EC 2022). The new hazard classes provide criteria for substances with PBT/vPvB, persistent, mobile and toxic (PMT), very persistent and very mobile (vPvM), and endocrine disruptive properties for the environment (ED ENV). This measure, together with the foreseen revision of REACH, may improve the interlinkage between the CLP and REACH and allow for a more harmonized approach toward environmentally hazardous substances. However, to ensure the safety of the cosmetic ingredients to the environment, further measures might be necessary.

First, the current prohibition of the use of CMR substances under the Cosmetic Products Regulation should be expanded to include the new hazard classes for PBT/vPvB, PMT/vPvM and endocrine disruptors in the environment. This measure would allow the use of all available hazard data, including already existing animal data, despite the ban on the use of animal data under the Cosmetic Products Regulation. This would be in line with the ambition of the Chemical Strategy for Sustainability to transform the CLP Regulation into the central piece of the EU chemicals legislation.

Further, we suggest removing cosmetic products as an exemption from the CLP Regulation’s obligation to classify mixtures. This would mean that environmentally hazardous cosmetic products would be labeled with hazard pictograms, similar to many other types of mixtures. In turn, this would allow the consumers to make more informed choices and promote substitution toward less hazardous cosmetic ingredients.

Next, a time-limit on the approval of the cosmetic preservatives, as well as colorants and UV-filters should be introduced. This would ensure that the approval decisions, and the data they are based on, are updated at a regular interval, and would help to avoid the continued approval of substances hazardous to human health or the environment.

Finally, the focus of this study has been the cosmetic preservatives. Cosmetic preservatives are one of the three groups of cosmetic ingredients that are subjected to an evaluation by the SCCS. Together with UV-filters and colorants, preservatives are assessed for their human health hazards to be approved. The remaining cosmetic ingredients are only evaluated for safety to human health in a finished product: an evaluation that is performed by the producer of the cosmetic products and that remains undisclosed. For example, perfluorinated substances (PFAS) are often found in cosmetic products (Pütz et al. Citation2022). These substances are not primarily used as preservatives, colorants or UV-filters; therefore, under the Cosmetic Products Regulation, no safety assessment is necessary. Which PFAS are used and at what concentrations is not reported. In fact, despite the obligation for market surveillance by the Member States, there is currently no database of substances used in cosmetic products. The Cosmetic Products Regulation already requires full list of ingredients on cosmetic products but does not require this information to be submitted to any database. The lack of knowledge about which substances are present in cosmetic products may lead to ineffective surveillance but may also have implications for environmental monitoring where a targeted approach is often used. Therefore, we suggest establishing a common database with information on the cosmetic products and the contained ingredients available on the EU-market.

The topic of the study can be considered an illustrative example of a wider problem in chemicals legislation in the EU and, most likely, across the world. Similar issues have been noted in the European Commission’s Fitness Check of chemicals legislation regarding other types of chemicals and involving other pieces of legislation. By identifying the root causes, consequences, and potential solutions to regulatory inconsistencies within the EU, this research may serve as a template for countries and regions facing analogous challenges.

Conclusions and recommendations

This study has shown that environmentally hazardous substances are among the cosmetic preservatives approved under the Cosmetic Product Regulation. There are several indications that environmental aspects of cosmetic ingredients are not effectively managed under REACH and that there are areas which call for improvement in the interface between the CLP, REACH and the Cosmetics Products Regulation.

We suggest a) extending the prohibitions of CMR substances under the Cosmetic Products Regulation to include the new environmental hazard classes under the CLP Regulation: PBT/vPvB, PMT/vPvM and endocrine disruptors in the environment b) removing cosmetic products from the list of exempted regulations for the classification of mixtures under the CLP Regulation c) introducing a time limit for approval of UV-filters, colorants and preservatives under the Cosmetic Products Regulation, and d) creating a common database for all substances used in cosmetic products.

In our opinion, these measures would be in line with the Chemicals Strategy for Sustainability and would strengthen the protection of the environment from hazardous cosmetic ingredients.

Author contributions

DK, MÅ and CR designed the study. DK collected and analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the discussions and to the manuscript. All authors have red and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the organizations.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (98.5 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The data that supports the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- [ANSES] French Agency for Food Environmental and Occupational Health and Safety. 2020. Substance evaluation conclusion as required by REACH article 48 and evaluation report for triclocarban EC No 202-924-1 CAS No 101-20-2.

- [EC] European Commission. 2012. Commission Regulation (EU) No 848/2012 of 19 September 2012 amending Annex XVII to Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council on the Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) as regards phenylmercury compounds. OJ L 253, 2092012; p. 5–7.

- [EC] European Commission. 2018. Checklists for applicants submitting dossiers on cosmetic ingredients to be evaluated by the SCCS.

- [EC] European Commission. 2019. Fitness check of the most relevant chemicals legislation (excluding REACH), as well as related aspects of legislation applied to downstream industries.

- [EC] European Commission. 2020. Chemicals strategy for sustainability towards a toxic-free environment.

- [EC] European Commission. 2022. Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2023/707 of 19 December 2022 amending Regulation (EC) No 1272/2008 as regards hazard classes and criteria for the classification, labelling and packaging of substances and mixtures. OJ L 93, 3132023; p. 7–39.

- [EC] European Commission. 2023. SCCS Notes of guidance for the testing of cosmetic ingredients and their safety evaluation - 12th revision.

- [ECHA] European Chemicals Agency. 2014. Decision on substanceevaluation pursuant to article 46(1) of regulation (EC) 1907/2006 For Triclosan, CAS No 3380-34-5 fEC No 222-182-2).

- [ECHA] European Chemicals Agency. 2016a. Decision of the Board of Appeal of the European Chemicals Agency Case A-018-2014.

- [ECHA] European Chemicals Agency. 2016b. Decision on Substance Evaluation Pursuant to Article 46(1) of Regulation (EC) 1907/2006 for Climbazole, CAS No 38083-17-9 (EC No 253-775-4).

- [ECHA] European Chemicals Agency. 2016c. Decision on Substance Evaluation pursuant to Article 46(1) of Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006 for methyl 4-hydroxybenzate CAS no 99-76-3 (EC No 202-785-7).

- [ECHA] European Chemicals Agency. 2018. Decision of the Board of Appeal of the European Chemicals Agency Case A-009-2016.

- [ECHA] European Chemicals Agency. 2019. Decision on Substance EvluationPursuant to Article 46(1) of Regulation 1907/2006 for Climbazole CAS No 38083-17-9 (EC No 253-775-4).

- [ECHA] European Chemicals Agency. 2020. Inclusion of substances of very high concern in the Candidate List for eventual inclusion in Annex XIV Doc: d (2020)4578-DC.

- [ECHA] European Chemicals Agency. 2021a. Inclusion of substances of very high concern in the Candidate List for eventual inclusion in Annex XIV Doc: d (2021)4569-DC.

- [ECHA] European Chemicals Agency. 2021b. Report on the Operation of REACH and CLP 2021.

- [ECHA] European Chemicals Agency. 2023a. Background document for glutaral. Document developed in the context of ECHA’s eleventh recommendation for the inclusion of substances in Annex XIV.

- [ECHA] European Chemicals Agency. 2023b. Triclosan. [updated 06/09/2023; accessed 19 June 2023]. https://echa.europa.eu/brief-profile/-/briefprofile/100.020.167.

- [EPCEU] European Parliament, Council of the European Union. 2006. Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 December 2006 concerning the Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH), establishing a European Chemicals Agency, amending Directive 1999/45/EC and repealing Council Regulation (EEC) No 793/93 and Commission Regulation (EC) No 1488/94 as well as Council Directive 76/769/EEC and Commission Directives 91/155/EEC, 93/67/EEC, 93/105/EC and 2000/21/EC. OJ L 396, 30122006; p. 1–849.

- [EPCEU] European Parliament, Council of the European Union. 2008. Regulation (EC) No 1272/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2008 on classification, labelling and packaging of substances and mixtures, amending and repealing Directives 67/548/EEC and 1999/45/EC, and amending Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006. OJ L 353, 31122008; p. 1–1355.

- [EPCEU] European Parliament, Council of the European Union. 2009. Regulation (EC) No 1223/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 November 2009 on cosmetic products. OJ L 342, 22122009, p. 59–209.

- [EPCEU] European Parliament, Council of the European Union. 2017. Regulation (EU) 2017/852 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 May 2017 on mercury, and repealing Regulation (EC) No 1102/2008. OJ L 137, 2452017, p. 1–21.

- Carey DE, McNamara PJ. 2014. The impact of triclosan on the spread of antibiotic resistance in the environment. Front Microbiol. 5:780. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00780.

- Cousins IT, Ng CA, Wang Z, Scheringer M. 2019. Why is high persistence alone a major cause of concern? Environ Sci Process Impacts. 21(5):781–792. doi: 10.1039/c8em00515j.

- Hungarian National Institute of Chemical Safety. 2015. Substance evaluation report - disodium disulphite EC 231-673-0, CAS 7681-57-4.

- Istituto Superiore di Sanità. 2018. Justification Document for the Selection of a CoRAP Substance for Trimethyloctadecylammonium chloride.

- Istituto Superiore di Sanità. 2019. Justification for removing a substance from CoRAP prior to evaluation for Trimethyloctadecylammonium chloride.

- Li M, He Y, Sun J, Li J, Bai J, Zhang C. 2019. Chronic exposure to an environmentally relevant triclosan concentration induces persistent triclosan resistance but reversible antibiotic tolerance in Escherichia coli. Environ Sci Technol. 53(6):3277–3286. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b06763.

- Lu J, Jin M, Nguyen SH, Mao L, Li J, Coin LJM, Yuan Z, Guo J. 2018. Non-antibiotic antimicrobial triclosan induces multiple antibiotic resistance through genetic mutation. Environ Int. 118:257–265. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2018.06.004.

- Nowak-Lange M, Niedziałkowska K, Lisowska K. 2022. Cosmetic preservatives: hazardous micropollutants in need of greater attention? Int J Mol Sci. 23(22):14495. doi: 10.3390/ijms232214495.

- Pütz KW, Namazkar S, Plassmann M, Benskin JP. 2022. Are cosmetics a significant source of PFAS in Europe? Product inventories, chemical characterization and emission estimates. Environ Sci Process Impacts. 24(10):1697–1707. doi: 10.1039/d2em00123c.

- Romero JL, Grande Burgos MJ, Pérez-Pulido R, Gálvez A, Lucas R. 2017. Resistance to antibiotics, biocides, preservatives and metals in bacteria isolated from seafoods: co-selection of strains resistant or tolerant to different classes of compounds [original research]. Front Microbiol. 8:1650. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01650.

- Rudén C, Hansson SO. 2010. Registration, Evaluation, and Authorization of Chemicals (REACH) is but the first step-how far will it take us? Six further steps to improve the European chemicals legislation. Environ Health Perspect. 118(1):6–10. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901157.

- Vale F, Sousa CA, Sousa H, Santos L, Simões M. 2022. Parabens as emerging contaminants: environmental persistence, current practices and treatment processes. J Cleaner Prod. 347:131244. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.131244.