Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this randomized controlled trial (Trial registration ID: redacted) was to examine the feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy of the Step One program, an SMS-based alcohol intervention for same-sex attracted women (SSAW).

Methods

Ninety-seven SSAW who scored ≥8 on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) were randomly allocated to receive the Step One program (n = 47; mean age = 36.79) or a weekly message containing a link to a website with health information and support services for LGBT individuals (n = 50; mean age = 34.08). Participants completed questionnaires on alcohol use, wellbeing, and help-seeking at baseline (T1), intervention completion (T2; 4 wk after baseline) and 12 wk post-intervention (T3). In addition, participants in the intervention condition completed feasibility and accessibility measures at T2, and a subsample (n = 10) was interviewed about acceptability at T3.

Results

Across conditions, participants significantly reduced their alcohol intake and improved their wellbeing and help-seeking over time. However, there were no significant differences between the intervention and control condition. Furthermore, frequency of help-seeking was low; only four intervention group participants and three control group participants began accessing support between T1 and T3. Overall, our findings indicate the intervention would benefit from revision prior to implementation.

Conclusions

Our approach was consistent with best practice in the development of an ecologically valid intervention; however, this intervention, in its current form, lacks the complexity desired by its users to optimally facilitate alcohol reduction among SSAW. Keywords: Alcohol intervention; Intervention mapping framework; Randomized controlled trial (RCT); Same-sex attracted women; Short-message service (SMS).

Introduction

Same-sex attracted women (SSAW) are at greater risk of consuming alcohol at hazardous levels than heterosexual women (Hughes et al., Citation2015; Operario et al., Citation2015; Roxburgh et al., Citation2016), yet they are more reluctant than heterosexual women to seek help for alcohol-related problems from mainstream support services (McCabe et al., Citation2013; Pennay et al., Citation2013). Past research has identified several barriers SSAW experience to approaching mainstream services. These include fear of stigma, low satisfaction with previous care experiences, and difficulty finding services that meet their unique needs (Hughes, Citation2011; Koh et al., Citation2014; McNair et al., Citation2011; McNair & Bush, Citation2016). These barriers could be overcome by providing SSAW-sensitive services that are developed with the specific support needs of SSAW in mind (Talley, Citation2013). However, the limited number of SSAW-sensitive alcohol support services currently available are often face-to-face and urban-based and, therefore, less accessible to women living in outer urban and rural areas (Cronin et al., Citation2021).

A promising way to overcome the accessibility issue for SSAW is the use of mHealth interventions. However, at the time of writing, the authors were aware of only one mHealth intervention specifically targeting SSAW. This intervention aims to reduce alcohol consumption through a digital app focused on correcting normative information around drinking and coping behaviors among sexual minority women (Boyle et al., Citation2021). Still, to provide SSAW with a variety of delivery options, it is important to explore other delivery modes, and one particular mode that has shown promise in reducing alcohol use in non-SSAW populations is the use of SMS messages (Agyapong et al., Citation2012; Bock et al., Citation2016; Haug et al., Citation2013; Kazemi et al., Citation2017; Suffoletto et al., Citation2014). We therefore set out to develop an SMS-based alcohol intervention called the Step One program, which targets SSAW engaging in problematic drinking.

The Step One program was developed using an intervention mapping approach (Bartholomew et al., Citation1998; Bartholomew Eldredge et al. Citation2016). This is a systematic and scientifically accepted user-centered design approach that has been used for the development and implementation of a wide range of mHealth intervention programs. The first step in this approach entailed conducting a needs assessment using focus groups and literature reviews. This assessment identified three target outcomes for the intervention, namely reducing alcohol use, improving wellbeing, and facilitating help-seeking behaviors, with the latter two having been identified in the needs assessment as key conduits to reducing alcohol use. The needs assessment also identified three change determinants that will facilitate the target outcomes, namely increasing motivational and self-regulatory abilities and improving the role of social support. Messages were then developed by mapping a selection of relevant Behavior Change Techniques (BCTs) onto the change determinants for each of the target outcomes. A review of existing SMS-based interventions for alcohol use as well as preferences expressed during the focus groups were used to determine duration and intensity of the intervention. This resulted in a four-week program consisting of one to two daily SMS messages, with a total of 10 messages per week.

The aim of the current study was to evaluate the feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy of the Step One program through a randomized controlled trial, with efficacy evaluations focusing on the three primary outcomes targeted by the intervention: reducing alcohol use, improving wellbeing, and improving help-seeking behavior. The trial was registered with the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (Trial ID: redacted). The study protocol has been published (Bush et al., Citation2019) and describes all study details in full.Footnote1

Method

Participant recruitment

Ethics approval was obtained from the relevant University Human Research Ethics Committee (reference number: 2017-077). Participants were recruited online between April 2017 and March 2018. The study was promoted through 1) advertisements at general practice clinics, 2) advertisements shared through Australian LGBT community and social networks, 3) participant lists from two previous studies (that targeted SSAW) with permission from the relevant Human Ethics Committee (reference number: 1647476.1); and 4) posters displayed in public common areas. The recruitment materials outlined, “Do you want to reduce your alcohol use and improve your wellbeing? If you are a same-sex attracted woman aged 18 or over, have a mobile phone, and access to the internet, you are invited to join this study. Go online and complete the survey using the link on the tab below. If you are eligible, you will start receiving SMS messages.” Eligibility criteria consisted of 1) identifying as a SSAW; 2) being aged 18 years or older; 3) being a problem drinker, which was defined as having an AUDIT (Babor et al., Citation2001) score ≥ 8; 4) living in Australia; 5) having access to the internet and owning a mobile phone with SMS capabilities; and 6) responding to the welcoming email and test SMS message.

Procedure and measures

Data were collected at three timepoints, with informed participant consent obtained at each. Baseline data, including eligibility data, was collected prior to randomization (T1). Eligible participants were then randomly allocated (1:1 ratio) to one of two conditions, the intervention (Step One program) or control, in a single-blinded parallel manner. A first follow-up survey was sent out upon completion of the 4-week intervention period (T2), and a second follow-up survey sent out 12 wk after completion of the intervention period (T3). Non-responders at T2 continued to be invited to the survey at T3, whereas participants who actively dropped out at T2 did not receive any further invitations to participate. Following completion of the online survey at T3, participants in the intervention condition were invited via email to participate in an interview to gain further insights into the acceptability of the intervention.

Trial conditions

Intervention

The intervention consisted of automated SMS messages delivered daily over a 4-week period. Participants received single messages on Sundays through Wednesdays, and two messages on Thursdays through Saturdays (40 messages in total; see table uploaded as supplemental file—this table forms a part of a separate paper by the same authors). On Sundays, participants were asked to report the number of standard drinks consumed in the past seven days. They received a standard drinks chart and a list of LGBT appropriate support services prior to initiation of the SMS messages.

Control

Consistent with other trials that have delivered SMS alcohol interventions, participants in the control group received one weekly SMS message that included a link to Touchbase, an Australian website with health information and support services for LGBT individuals (Abroms et al., Citation2012; Bock et al., Citation2016).

Surveys

The T1 baseline survey captured demographic information (see in Results) and measured the primary outcomes targeted by the intervention, namely amount (i.e., standard units consumed during past 30 days) and severity of alcohol use (AUDIT; Babor et al., Citation2001), wellbeing (PWI-A 5th edition; International Wellbeing Group, Citation2013) and help-seeking behaviors (use of a list of services). Eligibility was determined based on T1 responses.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of intervention and control group participants.

The T2 and T3 follow-up surveys again measured amount and severity of alcohol use, wellbeing, and current help-seeking. In addition, at T2, participants in the intervention group were asked a set of questions regarding feasibility and acceptability (see in Results). Finally, after completing the T3 survey, participants in the control group received the list of support services and were offered the opportunity to receive the intervention messages. To acknowledge their participation, individuals who had completed all three surveys went into a draw to win one of two $50 retail vouchers.

Table 2. Intervention Feasibility and Acceptability Questions from the Post-Intervention Survey (T2, n = 32).

Data analyses

Quantitative analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS© (Version 28). A full description of the analysis plan and hypotheses are described in the protocol paper (redacted). Sample size calculation was based on the only available Australian study of alcohol consumption in the SSAW population (Pennay et al., Citation2013), which provided estimates for the AUDIT score. A sample of 40 participants per group would have 84% power for detecting a post-intervention mean change of 4 points in the AUDIT score (SD = 6; two-tailed test, significance level 0.05) and 80% power to detect effect sizes larger than 0.63 for any of the other scores outcomes.

To examine feasibility, comparisons between conditions or between participants lost to follow-up versus retained were conducted using Chi-squared exact (2 groups) or Fisher’s exact (> 2 groups) test for categorical variables, and t-test (2 groups) or Kruskal-Wallis test (> 2 groups) for numerical variables. Qualitative analysis of acceptability data was done through a thematic analysis using Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006) guidelines.

Differences in efficacy for alcohol use, alcohol severity, and wellbeing based on group and time were assessed using linear mixed models including group (intervention vs. control), time (T1, T2, and T3), and group by time interaction as fixed effects, and participant as a random effect. Prior to conducting these analyses, data were inspected for extreme values and violations of normality. Given that the distribution of amount of alcohol use at T1, T2, and T3 was positively skewed, this variable was log-transformed prior to being entered into the analysis.

To examine differences in help-seeking based on group and time, we created a binary variable for each time point capturing whether or not help was sought through at least one source (no/yes). The effects of group, time, and their interaction on help-seeking (binary) was assessed using GEE (binary logistic: support accessed (no/yes)) with group (intervention vs. control), time (T1, T2, and T3), and their interaction as predictors, and participant as the subject variable. An unstructured covariance matrix was assumed.

Results

Participants

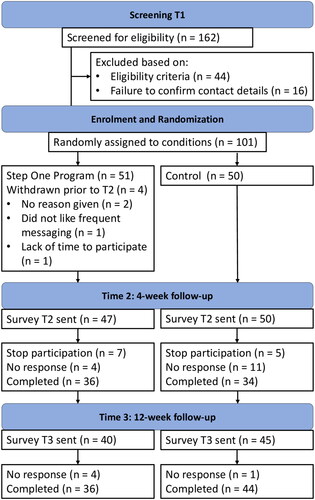

Between April 24, 2017, and March 22, 2018, the baseline survey (T1) was accessed by 299 individuals and completed by 162. contains a diagram summarizing the flow of these participants through the quantitative data collection phases. displays demographic characteristics of participants in each condition as well as comparisons between groups. There were no significant differences between conditions on any of the demographic characteristics (all p’s > 0.156).

With regard to the qualitative component of the study, out of the 36 intervention group participants who were invited to the interview component after completing the T3 survey, ten completed the interview and provided feedback on their experience with the intervention. The sexual orientations of these participants included lesbian (n = 8), and bisexual (n = 2); and the mean age was 40.4 years (SD = 12.9, range 18-60 years). Participants were predominantly from inner and outer urban locations in Melbourne, Australia, with two in rural locations. Based on the AUDIT scores, seven of the participants consumed alcohol at hazardous or harmful levels, and three consumed alcohol at moderate-severe levels.

Feasibility

Participant Drop-Out

Comparison of response rates at T2 or T3 as compared to T1 between conditions showed no significant difference in the change in response rates between conditions when comparing T2 to T1 (χ2(1) = 0.89, p = 0.374) and when comparing T3 to T1 (χ2(1) = 2.94, p = 0.118). However, the latter did approach significance, indicating that participants who accepted the invitation to partake in the intervention condition at T1 appeared somewhat less likely to respond to the survey at T3 (n = 36 out of 47) than participants who accepted the invite to partake in the control condition (n = 44 out of 51). When looking at characterstics of participants who actively dropped out at T2 (n = 12) versus remained in the study (n = 85) across conditions, those who dropped out did not differ in any of the demographic or study variables (all p > 0.242) except for alcohol use severity. Specifically, participants who remained in the study had a lower level of alcohol use severity (M = 17.71, SD = 6.32) than those who dropped out (M = 22.00, SD = 7.29), p = 0.033.

SMS message data

reports the feasibility and acceptability data measured at T2. Of the 32 participants who completed these items, 24 (75%) reported that they read the messages daily and only one participant reported rarely reading them. Twenty-four participants (51%) responded to the first Sunday message and reported their alcohol intake for the previous seven days, and 21 participants (45%) continued to respond to the remaining three Sunday messages.

Acceptability

As seen in , of the 32 participants who completed the acceptability items at T2, 81% indicated the timing of messages was appropriate. However, when asked about satisfaction with message frequency, only 47% reported moderate to high levels of satisfaction. When asked to indicate their preferred message frequency, 57% of participants indicated once or twice daily messages with the remainder preferring less than once a day. Overall, messages were rated as moderately to extremely helpful by 44% and moderately to extremely unhelpful by 28% of respondents. Although 38% of participants probably or certainly would not recommend an SMS-based intervention to other SSAW, 63% probably or certainly would. Finally, 91% reported that having tailored message content for SSAW was quite/very/extremely important to them.

Analysis of the qualitative interview data (n = 10) provided additional insights into the acceptability of the intervention. Five overarching themes were revealed: safety of the intervention, self-awareness of drinking behaviors, relevance and burden of the intervention, and agency. In line with quantitative results, each theme contained a mix of positive and negative evaluations. With regard to safety, some participants reported the intervention made them feel safe due to anonymity, but others reported feeling less safe because of the lack of direct counseling support. With regard to self-awareness of drinking behaviors, the intervention had a positive impact on some participants who started thinking about changing their behaviors. However, for others increased awareness highlighted their desire to drink or made them feel bad about their struggle with alcohol.

For relevance of message content, some participants were positive about the SSAW tailored content of the messages. However, others felt some messages were too general or irrelevant to them. Similarly, timing of the messages was judged as positive by some, but others indicated timing was not always relevant due to personal drinking patterns. In addition, although some participants provided positive feedback on the frequency of messages, several found the program too time consuming. Finally, feedback around the intervention’s effectiveness in providing users with motivation and agency for change was again mixed, with some indicating the intervention might be too confronting, resulting in reduced motivation to act rather than empowerment.

It was suggested that an app may be a more appropriate delivery method as it would provide recipients with more control over whether or when to read messages. In addition, an app would allow for individual tailoring of message topics and timing to improve relevance and acceptability.

Efficacy

reports the estimated marginal means for all outcome variables as well as the pairwise comparisons comparing the intervention to the control condition across timepoints. reports the number and percentage of participants engaging in help-seeking at each time point as well as the type of support they accessed.

Table 3. Estimated Marginal Means for Alcohol Use and Severity, Wellbeing, and Help-Seeking by Time and Condition.

Table 4. Help-Seeking by Accessing Treatment Services at Baseline, Post-Intervention and 12-Week Follow-Up, No. (%).

Alcohol use

For alcohol intake, there was an effect for time, p < 0.001, but no effect for condition, p = 0.262, an no interaction between group and time, p = .177. Pairwise comparisons for time revealed a significant drop in alcohol use over the past 30 days between T1 and T2 (ΔM = −0.16, SE = 0.05, p = 0.004), and between T1 and T3 (ΔM = −0.23, SE = 0.06, p < 0.001).

For alcohol use severity, there was a significant effect for time, p < 0.001, and a marginally significant interaction between group and time, p = 0.053, but no effect for group, p = .318. Pairwise comparisons for time revealed a decrease in severity between T1 and T2 (ΔM = −3.61, SE = 0.53, p < 0.001), and between T1 and T3 (ΔM = −3.98, SE = 0.69, p < 0.001). Upon examining the marginally significant interaction effect, this effect appeared to be due to differences in alcohol use severity between conditions being non-significant at T1 (p = 0.583) and T2 (p = 0.923), yet approaching significance at T3, with alcohol use severity being lower in the control condition than in the intervention condition (p = 0.059).

Wellbeing

For general wellbeing as measured by the PWIA, there was an effect for time, p = 0.017, but no effect for group, p = 0.988, and no interaction between group and time, p = .690. Pairwise comparisons for time revealed no significant improvement in wellbeing between T1 and T2 (ΔM = 0.18, SE = 0.13, p = 0.466), but a significant improvement in wellbeing from T1 to T3 (ΔM = 0.43, SE = 0.15, p = 0.020).

Help-Seeking

Upon examining the odds of someone seeking help by accessing at least one treatment option, there was an effect for time, p = 0.014, but no effect for group, p = 0.262 nor one for the interaction between time and group, p = .623. Pairwise comparisons for time revealed no change in perentage of people seeking help from T1 to T2 (ΔM = 6.08, SE = 5.70, p = 0.287), but a significant increase in percentage of participants engaging in help-seeking at T3 as compared to T1 (ΔM = 17.41, SE = 5.86, p = 0.003).

shows that, overall, there was a low frequency of alcohol support service uptake across timepoints. Only four intervention group participants and three control group participants began accessing new treatment between baseline and 12 wk post-intervention. The most commonly accessed forms of support were mental health professionals, including psychologists, psychiatrists or counselors, and general practitioners (GPs). Although no participants had used eHealth services at baseline, this changed at T2 and T3 with some participants accessing telephone helplines, an online counseling service, and mobile applications. No participants reported using prescribed medications to support alcohol reduction or attending a hospital emergency department.

Discussion

This three-wave study evaluated the feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy of the Step One program, which aimed to reduce alcohol use, increase wellbeing and increase help-seeking behaviors. Overall, the intervention was positively received by a majority of participants, but with a substantial minority rating the intervention and its components less favorable. Also, although the evaluation of efficacy revealed significant improvements on all three primary objectives of the intervention (i.e., reducing alcohol use and improving wellbeing and help-seeking behaviors) over time, there where no significant differences between the intervention and active control condition. The discussion below highlights several areas for potential improvement of the intervention prior to implementation.

Feasibility

Recruitment was lengthy, taking 11 months to recruit a total of 97 participants. This could be due to minority populations typically being hard to reach (Moradi et al., Citation2009; Sadler et al., Citation2010), compounded by the sensitive nature of this research project. Furthermore, recruitment coincided with the Australian Marriage Law Postal Survey which commenced on September 13, 2017. In the two months preceding the postal survey, the LGBT community experienced increased negative public scrutiny through homophobic violence, offensive graffiti and vandalism (Koziol, Citation2017). Indeed, few potential participants completed the baseline survey during this time.

Another potential explanation for the lengthy recruitment period may have been a general lack of motivation to reduce alcohol use amongst many SSAW due to the relatively high normativity of problematic levels of drinking in this population as compared to heterosexual females (e.g., Boyle et al., Citation2020; Gruskin et al., Citation2007; Parks, Citation1999). Overcoming such an engagement barrier would require motivational intervention strategies as an initial step prior to offering an intensive intervention program such as Step One. Still, our data showed that only 63% of participants who completed the baseline survey were eligible to receive the Step One program, and ineligbility occurred predominantly based on the prerequisite of having an Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) score ≥ 8. This indicates the requirement to have scored eight or above on the AUDIT may have in fact been too high to meet demands. Indeed, a lower audit score (6+) would still indicate a need for alcohol reduction. Although this particular intervention was developed to target high risk SSAW it is important for future research to ensure there are mHealth interventions available that target those with lower risk who nevertheless need and want an intervention.

Attrition at T2 and T3 was within normal range. However, the response rate to the Sunday messages was low. In conjunction with the qualitative interviews, this may indicate that participants did not want to interact with the intervention, stopped reading these messages, or that feelings of shame prevented them from reporting drinking behaviors. Therefore, it may not be feasible to expect recipients to interact with messages.

Acceptability

Both the quantitative and qualitative acceptability data indicated that the majority of participants evaluated the intervention positively, both in terms of its content and in terms of its delivery format and intensity. However, this was only a small majority, and a substantial minority provided less favorable feedback. Some of the conflicting feedback appeared to reflect the variability in participants’ needs. For example, participants who reported frustration with receiving messages on weekdays due to irrelevance had a lower AUDIT score, reflecting a less severe level of alcohol use as compared to participants who indicated high levels of satisfaction with message timing and frequency. This indicates that providing participants with an ability to indicate preferred message frequency and timing might yield better results than the current one-for-all intervention. In addition, the lack of direct counseling support leaving some participants feeling unsafe and the mixed effects of increased awareness of alcohol use highlight more general ways in which the intervention could be improved. This includes an evaluation of whether an app-based delivery, as suggested by participants, might be more appropriate than SMS-based delivery, and considering linking the mHealth intervention to tailored counseling services.

Efficacy

Evaluation of efficacy showed that, on average, participants significantly reduced their alcohol use and improved their wellbeing and help-seeking over time. However, there were no differences in reduction of alcohol use or improvement of wellbeing and help-seeking between those who received the Step One program and those in the control condition. The only difference between conditions over time that approached significance was found for alcohol use severity, and this appeared to be driven by the finding that those in the control condition reported lower levels of alcohol use severity at T3 than those who received the Step One program.

The finding that enrolling in the study had a positive impact on alcohol use regardless of condition is consistent with other alcohol trial evidence which has found that individuals enrolled in trials tend to display improvements regardless of the treatment group they have been allocated (Khadjesari et al., Citation2014). It is also consistent with other SMS trials focused on reducing alcohol use in which both arms have demonstrated reductions in use (Crombie et al., Citation2018; Mason et al., Citation2013; Merrill et al., Citation2018; Muench et al., Citation2017). However, there are some studies amongst different populations that have found significantly greater reductions in alcohol use among participants who received an SMS alcohol intervention compared with participants who received treatment as usual or no intervention (Haug et al., Citation2017; Suffoletto et al., Citation2014). These interventions differed from the Step One program in several ways. For one, they lasted 12 wk instead of four weeks. Furthermore, they included different content. For example, Haug et al. (Citation2017) developed a combined web and text-based intervention focused on reducing problem drinking in youth. In addition to messages targeting motivation and self-regulatory processes, this intervention included online feedback and messages on social norms. It also individually tailored the messages sent out. It must be noted, however, that the study only found significant differences for chances of risky single-occasion drinking occurring, not for average quantity of alcohol consumed. Still, another SMS-based intervention targeting young adults engaging in hazardous drinking (Suffoletto et al., Citation2014) sent participants queries about their alcohol use, with participants either receiving twice weekly feedback on their use, reporting use but not receiving such feedback, or not engaging in any text-messages at all. Participants who received feedback on their use showed a lower average number of drinks consumed per week, and reduced chances of binge drinking compared to the group who reported use but did not receive feedback. It thus appears that receiving personalized feedback on alcohol use was a common factor amongst these effective SMS-based interventions. Such personalized normative feedback on alcohol use was also a key element in the mHealth intervention targeting alcohol use amongst SSAW through an app (Boyle et al., Citation2021), with results showing that this feedback resulted in reduced drinking at a 2-month follow up. However, this study also found that reductions in drinking only remained significant at a 4-month follow up when the personalized normative feedback on alcohol use was combined with feedback on coping. This highlights that personalized feedback on alcohol use could be a key component to include in interventions targeting reduction of alcohol use, and that combining this with elements focused on improving coping and wellbeing might make the intervention particularly effective.

In addition to lacking a personalized feedback component, it is possible that the lack of difference between conditions in the current study was at least partially due to the control condition not being a pure control, with participants still receiving a weekly link to a website containing SSAW sensitive health and support information. Still, if sending participants a link to a website results in similar effects on alcohol use to the intervention, then this highlights a need to further explore the intervention and examine why it was not more effective in this space. Acceptability data indicates that it may be that the intense daily message program would be more effective for some, whereas more basic information provision such as the link provided in the control condition might be more suitable for others.

The mixed evaluations of the intervention, including a substantial proportion of participants stating they would probably or definitely not recommend the intervention to others, may tie into another potential explanation for the lack of difference between conditions. Specifically, our use of directive messages (e.g., “Write down the goals you want to achieve over the next 4 wk”) rather than autonomy-supportive messages (e.g., “What goals would you like to achieve over the next 4 week?”) for some of our SMS-based communications may have led to psychological reactance (Brehm, Citation1966) for some participants, resulting in rejection of the message or even engagement in behavior counteracting the purpose of the intervention (Dillard & Shen, Citation2005; Miller et al., Citation2007). Indeed, some participants stated the intervention increased rather than decreased their desire to drink. Still, findings on the impact of directive messages related to alcohol reduction on reactance are non-conclusive (e.g., Altendorf et al., Citation2019), and further research is required to explore how modification of message framing and intensity, as well as allowing for personalization in this domain may improve acceptability and effectiveness of the Step One program.

Limitations

A number of limitations to the current study need to be considered. First, it is possible that a more fine-grained measure of alcohol use (capturing frequency and quantity as well as risky single-occasion drinking) may have been more sensitive in detecting change in drinking behaviors. Secondly, the AUDIT and help-seeking questions used three different timeframes (T1: ‘past 12 months’ for AUDIT and ‘current use’ for help-seeking; T2: past four weeks; T3: past 12 wk). These timeframes were altered to avoid overlap, which is a known issue (de Visser et al., Citation2016). Still, future research could keep the timeframe consistent (e.g., past four weeks) across all measurement points. Additional limitations include the relatively small quantitative and qualitative samples, and a fairly short follow up period of 12 wk after completion of the Step One program. Finally, the difficulties experienced around recruitment highlight a need to reevaluate the recruitment strategies applied in the current study and examine ways to increase willingness to engage in the intervention amongst the target population.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the findings from this study provide useful insights around improvement of the Step One program as well as for the design of mhealth interventions targeting alcohol use, wellbeing, and help-seeking amongst SSAW more generally. For one, future research could transform the program into a more personalisable intervention where timing, frequency and focus of messages is flexible, and personalized feedback can be more easily included. This would move us even closer to a personalized support system that appreciates the variability in individuals’ support needs and preferences.

Supplemental File.docx

Download MS Word (17.1 KB)Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Thorne Harbour Health, Queerspace, Switchboard (Vic), Gay and Lesbian Health Victoria, PFlag Australia, LOTL, Out in Perth, Sydney Gay and Lesbian Business Association, Matrix Guild, AIDS Action Council, ShineSA, Sexual Health and Family Planning ACT, Touchbase, Gippsland Women’s health, Pink Sofa, ACON, Turning Point, Womens Health Victoria, QLife, Australian Womens Health Network, Australian Lesbian Medical Association, for helping with recruitment of participants into the study. Importantly we would like to thank the individuals who participated in this study and for their valuable feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The current paper reports on the feasibility, acceptability and efficacy based on primary outcomes and, as such, only the relevant measures are included below.

References

- Abroms, L. C., Ahuja, M., Kodl, Y., Thaweethai, L., Sims, J., Winickoff, J. P., & Windsor, R. A. (2012). Text2Quit: Results from a pilot test of a personalized, interactive mobile health smoking cessation program. Journal of Health Communication, 17(Suppl 1), 44–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2011.649159

- Agyapong, V. I. O., Ahern, S., McLoughlin, D. M., & Farren, C. K. (2012). Supportive text messaging for depression and comorbid alcohol use disorder: Single-blind randomised trial. Journal Of Affective Disorders, 141(2-3), 168–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2012.02.040

- Altendorf, M. B., van Weert, J. C. M., Hoving, C., & Smit, E. S. (2019). Should or could? Testing the use of autonomy-supportive language and the provision of choice in online computer-tailored alcohol reduction communication. Digital Health, 5, 2055207619832767. https://doi.org/10.1177/2055207619832767

- Babor, T. F., Higgins-Biddle, J. C., Saunders, J. B., Monteiro., & Maristela, G. World Health Organization. (2001). AUDIT: the alcohol use disorders identification test: guidelines for use in primary health care, 2nd ed. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/67205

- Bartholomew Eldredge, L. K., Markham, C. M., Ruiter, R. A. C., Fernández, M. E., Kok, G., & Parcel, G. S. (2016). Planning health promotion programs: An Intervention Mapping approach (4th ed.). Jossey-Bass Inc.

- Bartholomew, L. K., Parcel, G. S., & Kok, G. (1998). Intervention mapping: A process for developing theory and evidence-based health education programs. Health Education & Behavior: The Official Publication of the Society for Public Health Education, 25(5), 545–563. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019819802500502

- Bock, B. C., Barnett, N. P., Thind, H., Rosen, R., Walaska, K., Traficante, R., Foster, R., Deutsch, C., Fava, J. L., & Scott-Sheldon, L. A. J. (2016). A text message intervention for alcohol risk reduction among community college students: TMAP. Addictive Behaviors, 63, 107–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.07.012

- Boyle, S. C., LaBrie, J. W., & Omoto, A. M. (2020). Normative substance use antecedents among sexual minorities: A scoping review and synthesis. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 7(2), 117–131. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000373

- Boyle, S. C., LaBrie, J. W., Trager, B. M., & Costine, L. D. (2021). A gamified personalized normative feedback app to reduce drinking among sexual minority women: A randomized controlled trial and feasibility study (Preprint). Journal of Medical Internet Research, 24(5), e34853. https://doi.org/10.2196/34853

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brehm, J. W. (1966). A theory of psychological reactance. Academic Press.

- Bush, R., Brown, R., McNair, R., Orellana, L., Lubman, D. I., & Staiger, P. K. (2019). Effectiveness of a culturally tailored SMS alcohol intervention for same-sex attracted women: protocol for an RCT. BMC Women’s Health, 19(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-019-0729-y

- Crombie, I. K., Irvine, L., Williams, B., Sniehotta, F. F., Petrie, D., Jones, C., Norrie, J., Evans, J. M. M., Emslie, C., Rice, P. M., Slane, P. W., Humphris, G., Ricketts, I. W., Melson, A. J., Donnan, P. T., Hapca, S. M., McKenzie, A., & Achison, M. (2018). Texting to Reduce Alcohol Misuse (TRAM): main findings from a randomized controlled trial of a text message intervention to reduce binge drinking among disadvantaged men. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 113(9), 1609–1618. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14229

- Cronin, T. J., Pepping, C. A., Halford, W. K., & Lyons, A. (2021). Mental health help-seeking and barriers to service access among lesbian, gay, and bisexual Australians. Australian Psychologist, 56(1), 46–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/00050067.2021.1890981

- de Visser, R. O., Robinson, E., & Bond, R. (2016). Voluntary temporary abstinence from alcohol during “Dry January” and subsequent alcohol use. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 35(3), 281–289. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000297

- Dillard, J. P., & Shen, L. (2005). On the nature of reactance and its role in persuasive health communication. Communication Monographs, 72(2), 144–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637750500111815

- Gruskin, E., Byrne, K., Kools, S., & Altschuler, A. (2007). Consequences of frequenting the lesbian bar. Women & Health, 44(2), 103–120. https://doi.org/10.1300/J013v44n02_06

- Haug, S., Paz Castro, R., Kowatsch, T., Filler, A., Dey, M., & Schaub, M. P. (2017). Efficacy of a web- and text messaging-based intervention to reduce problem drinking in adolescents: Results of a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85(2), 147–159. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000138

- Haug, S., Schaub, M. P., Venzin, V., Meyer, C., John, U., & Gmel, G. (2013). A pre-post study on the appropriateness and effectiveness of a web- and text messaging-based intervention to reduce problem drinking in emerging adults. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 15(9), e196–e196. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.2755

- Hughes, T. (2011). Alcohol use and alcohol-related problems among sexual minority women. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 29(4), 403–435. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347324.2011.608336

- Hughes, T. L., Wilsnack, S. C., & Kristjanson, A. F. (2015). Substance use and related problems among U.S. women who identify as mostly heterosexual. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 803. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2143-1

- International Wellbeing Group. (2013). Personal Wellbeing Index: 5th Edition. Melbourne: Australian Centre on Quality of Life, Deakin University http://www.acqol.com.au/instruments#measures

- Kazemi, D. M., Borsari, B., Levine, M. J., Li, S., Lamberson, K. A., & Matta, L. A. (2017). A systematic review of the mHealth interventions to prevent alcohol and substance abuse. Journal of Health Communication, 22(5), 413–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2017.1303556

- Khadjesari, Z., Freemantle, N., Linke, S., Hunter, R., & Murray, E. (2014). Health on the web: Randomised controlled trial of online screening and brief alcohol intervention delivered in a workplace setting. PloS One, 9(11), e112553. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0112553

- Koh, C. S., Kang, M., & Usherwood, T. (2014). “I demand to be treated as the person I am”: experiences of accessing primary health care for Australian adults who identify as gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender or queer. Sexual Health, 11(3), 258–264. https://doi.org/10.1071/sh14007

- Koziol, M. (2017). “Vote no to fags”: Outbreak of homophobic violence, vandalism in same-sex marriage campaign. Sydney Morning Herald.

- Mason, M., Benotsch, E. G., Way, T., Kim, H., & Snipes, D. (2013). Text messaging to increase readiness to change alcohol use in college students. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 35(1), 47–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-013-0329-9

- McCabe, S. E., West, B. T., Hughes, T. L., & Boyd, C. J. (2013). Sexual orientation and substance abuse treatment utilization in the United States: Results from a national survey. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 44(1), 4–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2012.01.007

- McNair, R. P., & Bush, R. (2016). Mental health help seeking patterns and associations among Australian same sex attracted women, trans and gender diverse people: A survey-based study. BMC Psychiatry, 16(1), 209. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-016-0916-4

- McNair, R., Szalacha, L. A., & Hughes, T. L. (2011). Health status, health service use, and satisfaction according to sexual identity of young Australian women. Women’s Health Issues: Official Publication of the Jacobs Institute of Women’s Health, 21(1), 40–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2010.08.002

- Merrill, J. E., Boyle, H. K., Barnett, N. P., & Carey, K. B. (2018). Delivering normative feedback to heavy drinking college students via text messaging: A pilot feasibility study. Addictive Behaviors, 83, 175–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.10.003

- Miller, C. H., Lane, L. T., Deatrick, L. M., Young, A. M., & Potts, K. A. (2007). Psychological reactance and promotional health messages: The effects of controlling language, lexical concreteness, and the restoration of freedom. Human Communication Research, 33(2), 219–240. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2007.00297.x

- Moradi, B., Mohr, J. J., Worthington, R. L., & Fassinger, R. E. (2009). Counseling psychology research on sexual (orientation) minority issues: Conceptual and methodological challenges and opportunities. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56(1), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014572

- Muench, F., van Stolk-Cooke, K., Kuerbis, A., Stadler, G., Baumel, A., Shao, S., McKay, J. R., & Morgenstern, J. (2017). A randomized controlled pilot trial of different mobile messaging interventions for problem drinking compared to weekly drink tracking. PloS One, 12(2), e0167900. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0167900

- Operario, D., Gamarel, K. E., Grin, B. M., Lee, J. H., Kahler, C. W., Marshall, B. D., van den Berg, J. J., Zaller, & N. D., L. (2015). Sexual minority health disparities in adult men and women in the United States: National health and nutrition examination survey, 2001–2010. American Journal of Public Health, 105(10), e27–e34. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302762

- Parks, C. A. (1999). Lesbian social drinking: The role of alcohol in growing up and living as lesbian. Contemporary Drug Problems, 26(1), 75–129. https://doi.org/10.1177/009145099902600105

- Pennay, A., McNair, R., Lubman, D. I., Brown, R. F., Valpied, J., Leonard, L., Hegarty, K., & Hughes, T. (2013). The ALICE study: Alcohol and lesbian/bisexual women: Insights into culture and emotions. Drug and Alcohol Review, 32, 57–58. https:// https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12077

- Roxburgh, A., Lea, T., de Wit, J., & Degenhardt, L. (2016). Sexual identity and prevalence of alcohol and other drug use among Australians in the general population. The International Journal on Drug Policy, 28, 76–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.11.005

- Sadler, G. R., Lee, H.-C., Lim, R. S.-H., & Fullerton, J. (2010). Research Article: Recruitment of hard-to-reach population subgroups via adaptations of the snowball sampling strategy. Nursing & Health Sciences, 12(3), 369–374. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-2018.2010.00541.x

- Suffoletto, B., Kristan, J., Callaway, C., Kim, K. H., Chung, T., Monti, P. M., & Clark, D. B. (2014). A text message alcohol intervention for young adult emergency department patients: A randomized clinical trial. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 64(6), 664–672.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.06.010

- Talley, A. E. (2013). Recommendations for improving substance abuse treatment interventions for sexual minority substance abusers. Drug and Alcohol Review, 32(5), 539–540. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12052