ABSTRACT

External effects significantly affect Arctic tourism. This not only relates to climate change proposing a long-term threat but also other events, like the COVID pandemic. Small regional business active in Arctic tourism is forced to adapt to this reality and cannot escape from the consequences. The study aims to evaluate the situation from the perspective of the small- and medium-sized companies, representing the backbone of Arctic tourism. It focuses not only on the challenges that the pandemic has created but also those that lay ahead because of an inevitable climate change. The semi-structured interviews conducted in northern Norway provide new perspectives for businesses based on changes in traveler behavior and the subsequent adjustment in the touristic offering, as presented in the research. With the emerging trends of more individualized offers and social bonding during travel, the future of Arctic tourism no longer has to rely on adventure activities. A holistic appreciation of nature and culture by tourists provides the opportunity for a more resilient and less climate-dependent touristic product.

Introduction

Arctic tourism receives a continuous increase in attention. It is becoming more popular based on two basic reasons: first, the accessibility of regions above the Arctic Circle is increasing, and second, tourists aim for more individualized experiences and exceptional places to travel (Bystrowska & Dawson, Citation2017; Saarinen & Varnajot, Citation2019). Whereby accessibility is driven by an improvement in infrastructure and an increase in northern and Arctic cruises (Bystrowska & Dawson, Citation2017), the desire for a more remarkable travel is linked to the increasing desire for nature-based activity and the quietness of remote places like the Arctic region (Fjellestad, Citation2016; Varnajot, Citation2020).

This combination is also a driving force for governments and industry to focus more on possibilities in Arctic tourism as a development tool and to create destination attractiveness. By no surprise in particular, Finland, Norway and Sweden put a greater emphasis on branding touristic activities in the Arctic accordingly (Lucarelli & Heldt Cassel, Citation2020). The tourists’ drive for exceptionalism is met by the Arctic locations in particular by a combination of unique features offered by nature, like the northern lights and activities that require an unspoiled nature, temperature extremes and snow security, like dog sledding or ice fishing.

Aside from nature-based activities, cultural experiences have become increasingly important for the touristic value chain. Driving forces for the increased cultural interest are an increased interest in sustainability aspects, as well as an increasing awareness in the culture of the local population. This is particularly true for the First Nations in Canada and the Sami in northern Scandinavia (de la Barre & Brouder, Citation2013). A constant requirement for change in Arctic tourism activities (Lemelin et al., Citation2012) fostered this development.

Acknowledging the increasing importance of Arctic tourism for the destinations value chain, it is obvious that macro developments like climate change or a crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic and its aftermath have a significant impact on the tourist and business prospectus in the region (Jóhannesson et al., Citation2022). Though an increase in the average temperature might foster accessibility and increase potential visits (Lau et al., Citation2023), it has a harming effect on the sought-after products given the impact on the natural environment and resources (Palma et al., Citation2019). From a purely business-related perspective, one of the primary beneficiaries, cruise companies, may be able to adjust routings and change ports of calls and therefore avoid or mitigate the negative consequences (Bystrowska & Dawson, Citation2017). However, most of the landside experiences are offered by small and medium-sized (SME) local businesses. Those businesses are bound to place and integrated into the local community (Saarinen & Varnajot, Citation2019). Hence, they cannot mitigate the effects or change their operations in the same way.

As SME businesses are the backbone of Arctic tourism in Europe, it is surprising that research on their particular role aside from their stakeholder positioning and integration into a broader context so far appears limited (Tervo-Kankare et al., Citation2018). Some of this may be explained by the close interchange and connection between SME business in the Arctic and their respective communities (Fay & Karlsdóttir, Citation2011; Kaján, Citation2013; Sisneros-Kidd et al., Citation2019). Tervo-Kankare et al. (Citation2018) represent an exception to this assessment as they provide a local business-specific assessment with a focus on financial performance. The following contributes to an SME-specific perspective by putting local businesses in Artic tourism at the center of attention. It focuses on businesses in the Troms og Finnmark region and aims for a comprehensive view. The analysis addresses how SME businesses adapt to new realities of changing customer preferences and sustainability challenges. As this location is the most frequently visited Arctic tourism region in Europe and one of the most popular globally (Chen et al., Citation2021), the research focus is on the general business prospectus and the individual perspectives of businesses at this location. Without specifically addressing climate change, the focus laid on a rather general view on developments, perspective and challenges. However, it also presents a supplier perspective. Focusing on practical implications, it provides ideas and concepts to address the challenges that SME businesses are facing globally in Arctic tourism. This research took place in 2022 and the specific impacts of the COVID pandemic have also been addressed to ensure a separation of the results in COVID-induced and other effects. The pandemic itself also proved to be beneficial for the assessment because it allowed the ability to focus on both mitigation activities resulting from the pandemic and adaption activities on a broader level (Chen et al., Citation2022). These specific foci helped clarify how Arctic tourism developed from a local business perspective and which opportunities and challenges lay ahead.

Literature review

Existing literature about Arctic tourism is manifold from a geographical and a content-related perspective. What sticks out is a predominating discussion of Arctic tourism in the context of sustainability (Chen et al., Citation2014; Hall & Saarinen, Citation2010; James et al., Citation2020; Maher, Citation2012). Even research that specifically addresses local businesses and the SME sector, in particular, focuses on the issues of sustainability and more precisely climate change (Demiroglu et al., Citation2020; Kaján & Saarinen, Citation2013; Rauken & Kelman, Citation2012; Tervo-Kankare et al., Citation2018). Few papers addressed non-sustainability-related aspects, such as service quality, managerial aspects (Chen & Chen, Citation2016) or financial aspects (Tervo-Kankare et al., Citation2018). Related to this research, the connection of local businesses to other touristic activities like cruise tourism has been discussed as well (James et al., Citation2020). So, it is fair to state that business aspects of Arctic tourism slowly get more attention alongside sustainability issues (Chen et al., Citation2021; Tervo-Kankare et al., Citation2018).

Having a better conceptual understanding of Arctic tourism might assist in providing a local business-focused perspective (Hintsala et al., Citation2016). Whereby it is important to mention that even such a holistic perspective might make a clear separation of activities of communities as a whole and businesses as part of the communities more difficult (Fay & Karlsdóttir, Citation2011; Kaján, Citation2013; Sisneros-Kidd et al., Citation2019). Considering the growing importance and the connected research on business adaption (Chen et al., Citation2022), there has been a turn toward business-focused research, especially as businesses are a vital part of the economy of Arctic tourism (Remer & Liu, Citation2022).

This aspect of being a vital part of the tourism economy shed some light on a difficult to solve conflict regarding climate change. Hall and Saarinen (Citation2010) discussed the contradictory scenario between touristic growth because of attractiveness and accessibility with the environmental downside. This is a meta-topic among multiple research clusters focused on Arctic tourism (Stewart et al., Citation2005). But the research has not yet focused on who partakes in Arctic tourism, apart from initial tourist typology discussions (Wang et al., Citation2018).

Connected to this, research also focuses on travel behavior within Arctic tourism. One aspect evaluated is the quality perception of such behavior and its impact on visiting intention (Prebensen et al., Citation2012; Wang et al., Citation2018). As perceptions are media induced, media itself is shaping the travel behavior of tourists (Aldao & Mihalic, Citation2020) and results in selected activities, such as experiencing the weather or chasing the northern lights. The Arctic is famous for nature and snow-related activities that provide exceptional experiences (Saarinen & Varnajot, Citation2019). It may easily attribute some of those to the context of adventure tourism (Gyimóthy & Mykletung, Citation2004). Those outdoor-related activities, regardless if adventurous or not, are traditionally subject to a great level of seasonality (Hall & Saarinen, Citation2010; Stewart et al., Citation2005).

Seasonality is one of the most important framing effects on Arctic tourism, not only considering the tourist flows but also the accessibility and product development (Rantala et al., Citation2019). Such a ‘regular’ seasonal framework is coming under pressure by climate change and extreme weather-related events. Those changes in climate and the increase in extreme weather pose significant challenges to Arctic tourism destinations, regions, and providers (Kaján, Citation2014; Yu et al., Citation2009). Of course, not all changes and challenges are weather related. The COVID pandemic and the aftermath not only shaped and affected tourism as a whole, but Arctic tourism in particular (Jóhannesson et al., Citation2022). Most noticeable, the change in destinations and source markets (Remer & Liu, Citation2022) provides a recognizable challenge but also an opportunity for Arctic tourism business. This relates not only to packaged cruise travel, which most likely enjoys the largest share in transported visitors (Ren et al., Citation2021), but also business ‘on the ground’. In this respect, the pandemic may be seen as a prelude for adaptation strategies (Chen et al., Citation2022), which are important considering both the large dependency on tourism (Sisneros-Kidd et al., Citation2019) and the preparation for a ‘post-Arctic’-tourism in the Arctic (Varnajot & Saarinen, Citation2021).

Apart from the Arctic tourism focus, there is a significant amount of tourism literature focusing on adaptation and resilience of SMEs (Dahles & Susilowati, Citation2015; Núñez-Ríos et al., Citation2022; Williams et al., Citation2020). The COVID pandemic itself provides a significant amount of context for the themes of resilience and adaptation (Brown et al., Citation2022; Fuchs, Citation2022; Rastegar et al., Citation2023; Sharma et al., Citation2021). Based on the existing literature, aspects of adaptation and mitigation provide an important context to evaluate the positioning of SMEs within the Arctic tourism context. Based on this, the proposed research focuses on the question of how SME local businesses consider their development with respect to the required adaptation necessary because of climate change and changing customer preferences. To address upcoming crises, crisis mitigation activities derived from the pandemic expand this.

Methodology

Considering the lack of focus on local SME firms as tourism providers, this paper follows an explorative qualitative approach to grasp inside on the topic and to address the research question. From a conceptual perspective, the analysis is following the differentiation of adaptation and mitigation proposed by Chen et al. (Citation2022). In this respect, adaptation is understood as rather long-term activities versus short-term mitigation. To provide a wider context, the research is also considering commercially relevant aspects irrespective of crisis mitigation or adaptation.

The data has been collected via semi-structured interviews and analyzed via a qualitative content analysis, executed by both authors. By conducting the interviews in a semi-structured way, the interviewees are not restricted in their direction of responses. This allows the possibility to follow their individual experiences. Providing a structure, however, also avoids losing the focus of the research question (Brinkmann, Citation2020). A qualitative approach is particularly useful as it is not intending to confirm an existing theory or considerations, but to open a new field. It also allows insights into the variety of ideas and concepts on how to tackle challenges in the local Arctic business environment. Research has to consider differences based on the individual supplier business and customer groups. In particular, the research follows the structure of a thematic qualitative content analysis as proposed by Kuckartz (Citation2018). This approach is deemed useful, as it combines deductive elements found in the literature and acknowledges new findings emerging from the data. However, the latter is considered more important, given the novelty of the research.

Sampling

To address the research questions, a purposive sampling of SME businesses with a focus on activity-related offerings has been applied. SME businesses are deemed appropriate as they are most closely linked to the research question and being subject to climate change because of the dependency on nature and weather conditions they cannot escape. All businesses had to have their operations in the ‘Troms og Finnmark’ region. This region was selected because of its popularity among Arctic tourists (Chen et al., Citation2021).

Data collection

During the summer period of 2022, a total of 14 semi-structured interviews were conducted. Except for the tour operation cooperation, all companies taking part in the interviews had less than 50 employees. The interviews have been conducted with representatives of the senior management or the owner of the business (compare ). All interviews lasted between 15 and 30 min and covered questions regarding target groups, seasonality of business, COVID effects and perceptions of nature-based tourism. With those 14 interviews, the study achieved a thematic saturation (Saunders et al., Citation2018) after the 13th interview. Given the 14th interview was already conducted and transcribed, it has been included in the analysis. With 14 interviews, the size corresponds to proposed saturation standards (Francis et al., Citation2010) and is deemed appropriate and the findings provide novel, practical and useful information (O’Reilly & Parker, Citation2013).

Table 1. Sample of the semi-structured interviews.

The interviews were set up transparently by explaining the purpose and context of the study to the interviewees. To ensure the highest possible convenience for the participants, the interviews took place either personally, via phone or videoconferences. Hence, the focus is on the content of the interview and omits non-verbal communication for all interviews to ensure comparability (Silverman, Citation2017). Considering the context in a post-pandemic world, the interview acknowledged and addressed the COVID pandemic as an important topic to ensure an accurate interpretation of the interviews (Vogler, Citation2023).

Data analysis

The interviews were transcribed verbatim according to a defined set of rules (Rädiker & Kuckartz, Citation2019). Following the transcription, the content was analyzed according to a thematic analysis to extract thematic and sub-thematic topics. Coding and categorization were executed a priori (deductive coding) as well as inductive data-driven (Kuckartz, Citation2018) as illustrated in . For the deductive coding, categories and codes have been identified based on the reviewed literature, in particular Chen et al. (Citation2022). In addition to those, themes emerging from the data complement the deductive findings.

Table 2. Example of the coding process of the study.

The coding has been executed in a consensual way by both authors without considering the category in the first step. Codes have been grouped into categories and compared and checked for similarities iteratively. Based on the iterative process, codes and categories have been re-grouped and combined into main categories until the authors reached a final consensus. The research and the interpretation are following a constructivism research paradigm, acknowledging the constructed reality of the business owners and representatives. In addition, the individual coding and categorization followed a defined set of interpretation rules to ensure a high level of trustworthiness (Vogler, Citation2023).

Findings

The interviews revealed a variety of very specific findings and business challenges and perspectives. They are either typical for local business or focus on aspects that may represent significant challenges or perspectives. In summary, the findings and the respective categories are structured according to adaptation and mitigation activities and their corresponding outlooks.

COVID impact and aftermath

Given the timing of the interviews, the impact of the pandemic is still obvious, from both target group and procedural perspectives. Service providers had to adjust their offering geared towards domestic tourism as well as address local customers and, in particular, group businesses from nearby cities. With these mitigation activities, businesses tried to protect their market position and tried to remain in the market during and beyond the pandemic. The integration into the community proved to assist in the quest for business survival. As the last interviewee put it:

I had to adjust my tours to try to be more attractive for the local markets, and I had to try out new groups of customers. Last winter, I had quite a lot of kindergartens and private family and families from the city. Also, of course, some national tourists from the south, because people in the south of Norway, they couldn’t go to the out or to Spain as usual. They had to do travelling around and do other things. They were also exploring Norway. (Int. 14)

I think that what you’re seeing is that the booking date is much closer to the actual arrival date. People might plan long ahead, but they don’t buy long ahead compared to previously. (Int. 1)

People were not fully booked all the time. Some went bankrupt due to the pandemic, some of them had to close, some of them had to be bought up by others.

Now when there are less companies, the first thing that are fully booked, I would say is dog sledding, because it’s a very demanding activity to do for companies, so it’s not easy just say, ‘Well, we start dog sledding now’, it’s a lot of work. It takes years to build up. Maybe in a couple of years we will have more companies again, but with Northern Lights tours, [chuckles] it takes two months to make a company. (Int. 6)

Regarding the catch-up travel requirement, the imposed governmental requirement to stay at home especially led to an immediate desire for travel and, pending the severance of restrictions, the desire to become active outside, which has been described as an increasing need for travel:

I think the needs are the same, but I think the need for travel has increased during the pandemic. The need for getting out of your own country out of your own home has increased with the pandemic. When you’re incarcerated in your own home, when you don’t get to choose whether you can go outdoors or not, when the door finally opens, you’ll leave the house and you will stay outdoors for as long as you want, as long as you can. (Int. 12)

Just to say, the main change that have happened, is that we have lost a lot of people with good knowledge and that affect our activities when it comes to hiking, when it comes to guide on a glacier, when it comes to do Northern Light hunting. This is people who have been building up their knowledge for years and years and when they disappear and we still have the same demands from the guests coming in, there is a lack of knowledge that we can’t fill up. […]when I hired one person, I had 10 people who was teaching this one person to do the job. Now I have to hire 10 people and I have one person who’s going to teach the 10 people. Of course, for sure it’s going to be things that is going to be missed out. That’s difficult when we’re restarting the tourist industry again after two years with Corona. (Int. 11)

International target groups and impact on Arctic tourism business

One aspect frequently mentioned is a correlation between business type, partners with which businesses cooperate, and the impact on their customers. Service providers that work with intermediates not only face the intermediates’ challenges but also have to adjust their business according to their needs.

When a provider works together with cruise companies, it generally produces an older client group, influencing the services and activities that can be marketed to them. Likewise, if a provider cooperates with either an incoming agency or a tour operator abroad, the geography of the guests and visitors will adjust accordingly. In sum, this aspect of the business is probably one that is going to undergo a significant change as tourists aim for more individualized experiences. This development will increase the complexity of service provision and, hence, represents an additional knowledge challenge.

Based on the interviews, this represents a potential adaptation to new realities, as it indicates a rather general demand shift. Also, it is a revenue increasing possibility as people are willing to pay more for individualized and exclusive experiences. The following two interviews provide a solid insight for this:

Dealing with groups that we have done for many, many years, it’s more difficult that we need to go down in numbers and making smaller groups, smaller arrangements, and more individual-based program for smaller groups than we did five years ago. (Int. 11)

Now we can focus more on the smaller groups, the intimate experiences and the intimate experience also creates a lot more revenue. It also creates a lot more publicity for us. When I have a group of four guests, which I spend two, three hours with, they have a memorable time. They feel seen, they feel heard, and they get to ask the questions they have. (Int. 12)

Nature-based tourism and culture is a growing sector

From a desired activity perspective, the main travel reasons for Arctic tourism remain the northern lights, dog sledding and other activities considered typical for the Arctic environment. In a post-Arctic tourism world, this inherits a requirement for further adaptation. Nuances of travel reasons are about to change. Activity was the typical focal point in the past. This has now converted to the experience of nature as a whole and the interaction with the related local culture.

… and the main product in the Fjord expedition is to share the history of Senja, this culture, heritage. Speak about the local nature phenomena, history and culture roaming. (Int. 2)

Nature-based is definitely the trend. I think it was further strengthened by Corona, because we all suffered of being locked in cement buildings in cities and so on. I think people are really longing for nature and isolation like not being in the mass tourism. I think the mass tourism is pretty much dead, I hope so. (Int. 9)

They want to have more connectivity. We’ve been discussing that recently that we have snowmobile tours, but people want to do more stops, maybe have a bonfire, sit at a fire and talk. These walks that we do the snowshoes, so they can walk up to have a viewpoint, and they can light the fire and maybe make some food. We see people do a lot of walks. They want to be out, experiencing the snow, the Northern lights. I think absolutely they’re really, really amazed by all the snow and the beauty of the nature when they come up North. […] I think we see that people want more of a personal meeting, so we have to focus more on not driving so far but stopping and making a bonfire, for example, and doing more of a surprise, a more human contact. (Int. 13)

Concerns and upcoming challenges

As a result of the COVID pandemic, all businesses appear strongly concerned about external shocks that may and will impact tourism and, in particular, tourist behavior. As a result, business owners have a strong focus on mitigation aspects of their businesses. From a geopolitical point of view, the Ukraine war represents a strong area of concern, not just because of the war itself, but also because of the tensions between Russia and Western Europe and the impact on Russian tourists.

Independent of geopolitics, environmental effects and, in particular, climate change will alter the way Arctic tourism providers are going to deal with the future. The requirement for adaptation is already visible in the change of seasonality. Today the high season is still the winter months, but summer travel is catching up and companies have to adjust to those new realities:

No, it´s always been more people in the winter, but we see that there are more more people coming in the summer as well. (Int. 8)

Yes, up to now the winter products have been the core business, will probably stay like this, but the company is trying to become a 12-month company. We’re beginning to also produce summer products. (Int. 9)

Now we are in a shoulder season and we are trying to develop some new products for spring and fall. It is difficult, because the reindeer are now quite relaxed, normally, they would’ve migrated now to the summer location. The whole setting is quite different. (Int.12)

Discussion

Arctic tourism businesses have a solid tradition in transforming according to changes in demand structures (Lemelin et al., Citation2012). The findings for the impact of external effects, let it be COVID or the impact of climate change, correspond with several earlier findings. The impact of the pandemic on Arctic tourism (Falk et al., Citation2022; Gyimóthy et al., Citation2022; Marques et al., Citation2022) and the expressed desire for catch-up or revenge travel (Kim et al., Citation2022; Vogler, Citation2022; Wang & Xia, Citation2021) are pretty universal. Hence, they are not necessarily specific to Arctic tourism. Relating it to the conceptualization of Chen et al. (Citation2022), those external effects represent reasons for mitigation activities. In light of the corresponding changes, the integration into the community (Kaján, Citation2013) appears to especially lead to a greater resilience for the businesses (cf. Sisneros-Kidd et al., Citation2019).

It is difficult to differentiate between ‘normal’ business transformation, crisis mitigation and long-term adaptation to major changes like climate change. Similar to other nature- and snow-dependent tourism regions, e.g. alpine regions, Arctic tourism has to adopt to a new reality (Demiroglu et al., Citation2020; Kaján & Saarinen, Citation2013). This affects not only the seasonality and the offering. It also affects business operations. In this respect, business owners are aware of the effect and do not try to neglect it (cf. Hamilton et al., Citation2012). Down-times that are typically used for repairing and re-setting (Dawson et al., Citation2011; Martin Martin & Guaita Martinez, Citation2020) are now required to be filled with revenue-generating activity, as the winter dependency alone does not allow for sufficient income. As a consequence, businesses have to adapt not only their business operations but also organizational structures.

This, combined with an overall risk of staff and knowledge shortage as an organizational challenge, could be seen in the pandemic’s aftermath in tourism industries worldwide (Liu-Lastres et al., Citation2023). Whereby in sun and beach tourism destinations the unavailability in man and woman power represents a long-term risk (Butler, Citation2022), the knowledge power loss appears to be more severe in the Arctic tourism context.

Focusing on positive aspects, it stands out that Arctic tourism seems, at least in a regional context, to profit from the trend towards individualization (Stamboulis & Skayannis, Citation2003). Individualization at least in the Norwegian Arctic seems to be coupled with a higher willingness to pay and results in a double win: service providers try to reach independency from cruise and larger tour operator business and having the possibility to keep a larger share of the tourist money. The desire for a more individualized travel experience is opening the pockets of tourists. In this respect, normal transformation processes go hand-in-hand with adaptation requirements.

Limitations

The research is based on a rather small geographical area in the European Arctic and it may be difficult to draw a general conclusion or recommendation out of it. This is particularly relevant, as the sample for the case study is limited to 14 participants. Though the research reached saturation, it cannot be ruled out that other business activities have a different perception of mitigation and adaptation needs. Also, the offering structure may not completely represent the business activities in this region or Arctic tourism in general. Especially, the frequent references to Sami culture and the desire of domestic tourists to learn about it may be limited to this area. Hence, it is of interest if the same or similar phenomena exist in, e.g. Greenland or the North American Arctic environment, with different cultural traditions but shared challenges. For further research, it is desirable, apart from using different geographical contexts, to evaluate whether the mentioned changes are persistent or local businesses revert back to their traditional business structures. This research should open up the possibility of further research in assessing if the expressed business perspectives and challenges exist to this extend or if they are predominantly shaped by the image and impression of the preceding COVID crisis.

Although this exploration shows a certain level of trustworthiness for the expressed observation, more research in this matter remains necessary. Also, the perspective of the local communities and domestic tourists needs further assessment. Both are addressed in this research as consumption beneficiaries that require academia to make their voice heard as well. Finally, the current and increasing impact of climate change on business and community adaptation, especially in Arctic context, should be further elaborated. This research already shows a possible solution frame in changing seasonality and business offering. Hence, a rather holistic perspective is desirable.

Conclusion and implications

In summary, the external macro effects, either being from health issues, climate change, economic circumstances or geopolitics, do not leave Arctic tourism activities unaffected. Various mitigation changes that local businesses have to undertake and address are resulting from those. But, some of those changes and their driving forces result in new business opportunities and highlight practical implications: for example, the stronger desire for group activities and a more relaxed-nature tourism approach may result in new business strategies. In addition, cultural activities, with bonfires and intimate experiences, may provide alternatives to cope with the challenges. Despite winter nature phenomena and activities being still priority number one for an Arctic tourism visit (Gyimóthy & Mykletung, Citation2004; Rantala et al., Citation2019), it is no longer focused on an extraordinary adventure experience alone. Theoretically, the new desired activities allow Arctic tourism businesses to disconnect from snow-intense extreme weather conditions and make their businesses sustainable even in times of climate change.

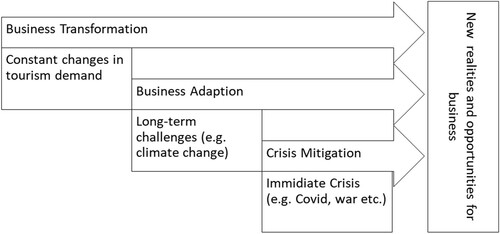

This activity focus also illustrates a rather generic finding. Despite some of the changes in business and demand being the results of an external shock that require mitigation approaches, they are not isolated. A constant change in business and tourist requirements is the norm. Plus, the overarching global challenges like global warming lead to a constant need to adapt. Based on this combination, three change stream dimensions can be identified () and it is to be concluded that successful tourism businesses in the Arctic need to consider all three of them.

Some of those changes come hand in hand. Downsizing of group sizes and activity intensity might especially help businesses to cope with staff shortages, as fewer people are required to accommodate larger groups. And those people do not always have to fulfill the high standards necessary for facilitating adventurous activities. In short, even a small team consisting of owners and their families might be able to cater to the needs and provide a more personal and individual service at the same time (Lerner & Haber, Citation2001). This is especially true for combining nature and culture activities.

As the customers’ willingness to pay for those services and Arctic tourism products will be higher, the downsizing might also not be too harmful on the revenue side (Di Domenico & Miller, Citation2012; Lerner & Haber, Citation2001). Such an individualized, more personal offering gears touristic products towards the customer group of rather settled senior people that have both time and money to spend. But obviously all tourism businesses also need to consider new and upcoming customer groups. It will be important to evaluate whether the trend towards domestic tourism persists, as those tourists represent a revenue challenge as their accommodation preferences will cause a lower desire for paid activities and services. In this respect, the mentioning of foreign students already living in the country may provide a solid basis for new customers as they can get acquainted to the destination at an early stage and become marketing ambassadors in their home countries (Cho et al., Citation2021; López et al., Citation2016). Given the age of students, this also may represent a solid base for providers of traditional adventure types of activities or result in long-lasting customer loyalty. Focusing on customers already living in the country represents a chance not only to mitigate crises that result in a lack of tourists from abroad. Having a constant customer base from the local or domestic communities works not only as a mitigation but also adaptation and transformation strategy at the same time. Additionally, it may help build up a certain level of crisis resilience for both businesses and communities as it reduces the dependency from international tourism streams (Sisneros-Kidd et al., Citation2019).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aldao, C., & Mihalic, T. A. (2020). New frontiers in travel motivation and social media: The case of longyearbyen, the high Arctic. Sustainability, 12(15), Article 5905. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12155905

- Brinkmann, S. (2020). Unstructured and semistructured interviewing. In P. Leavy (Ed.), Oxford handbooks series. The Oxford handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., pp. 424–456). Oxford University Press.

- Brown, K., Jie, F., Le, T., Sharafizad, J., Sharafizad, F., & Parida, S. (2022). Factors impacting SME business resilience post-COVID-19. Sustainability, 14(22), Article 14850. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142214850

- Butler, R. (2022). COVID-19 and its potential impact on stages of tourist destination development. Current Issues in Tourism, 25(10), 1682–1695. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1990223

- Bystrowska, M., & Dawson, J. (2017). Making places: The role of Arctic cruise operators in ‘creating’ tourism destinations. Polar Geography, 40(3), 208–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/1088937X.2017.1328465

- Chen, J. S., & Chen, Y-L. (2016). Tourism stakeholders’ perceptions of service gaps in Arctic destinations: Lessons from Norway’s Finnmark region. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 16, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jort.2016.04.006

- Chen, J. S., Johnson, C., Wang, W., & Chen, Y-L. (2014). Stakeholders’ perspective of sustainability in an Arctic region: A qualitative study. Tourism Analysis, 19(1), 85–96. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354214X13927625340271

- Chen, J. S., Wang, W., Jensen, O., Kim, H., & Liu, W-Y. (2021). Perceived impacts of tourism in the Arctic. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 19(4), 494–508. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766825.2020.1735403

- Chen, J. S., Wang, W., Kim, H., & Liu, W-Y. (2022). Climate resilience model on Arctic tourism: Perspectives from tourism professionals. Tourism Recreation Research, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2022.2122341

- Cho, H., Tan, K. M., & Chiu, W. (2021). Will I be back? Evoking nostalgia through college students’ memorable exchange programme experiences. Tourism Review, 76(2), 392–410. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-06-2019-0270

- Dahles, H., & Susilowati, T. P. (2015). Business resilience in times of growth and crisis. Annals of Tourism Research, 51, 34–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2015.01.002

- Dawson, D., Fountain, J., & Cohen, D. A. (2011). Seasonality and the lifestyle “conundrum”: An analysis of lifestyle entrepreneurship in wine tourism regions. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 16(5), 551–572. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2011.597580

- de la Barre, S., & Brouder, P. (2013). Consuming stories: Placing food in the Arctic tourism experience. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 8(2-3), 213–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2013.767811

- Demiroglu, O. C., Lundmark, L., Saarinen, J., & Müller, D. K. (2020). The last resort? Ski tourism and climate change in Arctic Sweden. Journal of Tourism Futures, 6(1), 91–101. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-05-2019-0046

- Di Domenico, M., & Miller, G. (2012). Farming and tourism enterprise: Experiential authenticity in the diversification of independent small-scale family farming. Tourism Management, 33(2), 285–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2011.03.007

- Falk, M. T., Hagsten, E., & Lin, X. (2022). Domestic tourism demand in the North and the South of Europe in the COVID-19 summer of 2020. The Annals of Regional Science, 69(2), 537–553. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-022-01147-5

- Fay, G., & Karlsdóttir, A. (2011). Social indicators for Arctic tourism: Observing trends and assessing data. Polar Geography, 34(1-2), 63–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/1088937X.2011.585779

- Fjellestad, M. T. (2016). Picturing the Arctic. Polar Geography, 39(4), 228–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/1088937X.2016.1186127

- Francis, J. J., Johnston, M., Robertson, C., Glidewell, L., Entwistle, V., Eccles, M. P., & Grimshaw, J. M. (2010). What is an adequate sample size? Operationalising data saturation for theory-based interview studies. Psychology & Health, 25(10), 1229–1245. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870440903194015

- Fuchs, K. (2022). Small tourism businesses adapting to the new normal. Tourism: An International Interdisciplinary Journal, 70(2), 258–269. https://doi.org/10.37741/t.70.2.7

- Gyimóthy, S., Braun, E., & Zenker, S. (2022). Travel-at-home: Paradoxical effects of a pandemic threat on domestic tourism. Tourism Management, 93, Article 104613. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2022.104613

- Gyimóthy, S., & Mykletung, R. J. (2004). Play in adventure tourism: The case of Arctic trekking. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(4), 855–878. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2004.03.005

- Hall, C. M., & Saarinen, J. (2010). Polar tourism: Definitions and dimensions. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 10(4), 448–467. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2010.521686

- Hamilton, L. C., Cutler, M. J., & Schaefer, A. (2012). Public knowledge and concern about polar-region warming. Polar Geography, 35(2), 155–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/1088937X.2012.684155

- Hintsala, H., Niemelä, S., & Tervonen, P. (2016). Arctic potential – Could more structured view improve the understanding of Arctic business opportunities? Polar Science, 10(3), 450–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polar.2016.07.001

- James, L., Olsen, L. S., & Karlsdóttir, A. (2020). Sustainability and cruise tourism in the Arctic: Stakeholder perspectives from Ísafjörður, Iceland and Qaqortoq. Greenland. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(9), 1425–1441. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1745213

- Jóhannesson, GÞ, Welling, J., Müller, D. K., Lundmark, L., Nilsson, R. O., de La Barre, S., Granås, B., Kvidal-Røvik, T., Rantala, O., Tervo-Kankare, K., & Maher, P. T. (2022). Arctic tourism in times of change: Uncertain futures - from overtourism to re-starting tourism. TemaNord: 2022, 516. Nordic Council of Ministers.

- Kaján, E. (2013). An integrated methodological framework: Engaging local communities in Arctic tourism development and community-based adaptation. Current Issues in Tourism, 16(3), 286–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2012.685704

- Kaján, E. (2014). Arctic tourism and sustainable adaptation: Community perspectives to vulnerability and climate change. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 14(1), 60–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2014.886097

- Kaján, E., & Saarinen, J. (2013). Tourism, climate change and adaptation: A review. Current Issues in Tourism, 16(2), 167–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2013.774323

- Kim, E. E. K., Seo, K., & Choi, Y. (2022). Compensatory travel post COVID-19: Cognitive and emotional effects of risk perception. Journal of Travel Research, 61(8), 1895–1909. https://doi.org/10.1177/00472875211048930

- Kuckartz, U. (2018). Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. Methoden, Praxis, Computerunterstützung (4 [überarbeitete] Auflage). Grundlagentexte Methoden. Beltz Juventa.

- Lau, Y., Kanrak, M., Ng, A. K., & Ling, X. (2023). Arctic region: Analysis of cruise products, network structure, and popular routes. Polar Geography, 46(2-3), 157–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/1088937X.2023.2182381

- Lemelin, R. H., Johnston, M. E., Dawson, J., Stewart, E. S., & Mattina, C. (2012). From hunting and fishing to cultural tourism and ecotourism: Examining the transitioning tourism industry in Nunavik. The Polar Journal, 2(1), 39–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/2154896X.2012.679559

- Lerner, M., & Haber, S. (2001). Performance factors of small tourism ventures. Journal of Business Venturing, 16(1), 77–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(99)00038-5

- Liu-Lastres, B., Wen, H., & Huang, W-J. (2023). A reflection on the Great Resignation in the hospitality and tourism industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 35(1), 235–249. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-05-2022-0551

- López, X. P., Fernández, M. F., & Incera, A. C. (2016). The economic impact of international students in a regional economy from a tourism perspective. Tourism Economics, 22(1), 125–140. https://doi.org/10.5367/te.2014.0414

- Lucarelli, A., & Heldt Cassel, S. (2020). The dialogical relationship between spatial planning and place branding: Conceptualizing regionalization discourses in Sweden. European Planning Studies, 28(7), 1375–1392. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1701293

- Maher, P. T. (2012). Expedition cruise visits to protected areas in the Canadian Arctic: Issues of sustainability and change for an emerging market. Tourism: An International Interdisciplinary Journal, 60(1), 55–70. https://hrcak.srce.hr/80773.

- Marques, C. P., Guedes, A., & Bento, R. (2022). Rural tourism recovery between two COVID-19 waves: The case of Portugal. Current Issues in Tourism, 25(6), 857–863. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1910216

- Martin Martin, J. M., & Guaita Martinez, J. M. (2020). Entrepreneurs’ attitudes toward seasonality in the tourism sector. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 26(3), 432–448. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-06-2019-0393

- Núñez-Ríos, J. E., Sánchez-García, J. Y., Soto-Pérez, M., Olivares-Benitez, E., & Rojas, O. G. (2022). Components to foster organizational resilience in tourism SMEs. Business Process Management Journal, 28(1), 208–235. https://doi.org/10.1108/BPMJ-12-2020-0580

- O’Reilly, M., & Parker, N. (2013). Unsatisfactory saturation’: A critical exploration of the notion of saturated sample sizes in qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 13(2), 190–197. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794112446106

- Palma, D., Varnajot, A., Dalen, K., Basaran, I. K., Brunette, C., Bystrowska, M., Korablina, A. D., Nowicki, R. C., & Ronge, T. A. (2019). Cruising the marginal ice zone: Climate change and Arctic tourism. Polar Geography, 42(4), 215–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/1088937X.2019.1648585

- Prebensen, N. K., Woo, E., Chen, J. S., & Uysal, M. (2012). Experience quality in the different phases of a tourist vacation: A case of northern Norway. Tourism Analysis, 17(5), 617–627. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354212X13485873913921

- Rädiker, S., & Kuckartz, U. (2019). Analyse qualitativer Daten mit MAXQDA. Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-22095-2

- Rantala, O., Jóhannesson, GÞ, & Müller, D. K. (2019). Arctic Tourism in Times of Change: Seasonality. TemaNord. Nordic Council of Ministers. https://doi.org/10.6027/TN2019-528

- Rastegar, R., Seyfi, S., & Shahi, T. (2023). Tourism SMEs’ resilience strategies amidst the COVID-19 crisis: The story of survival. Tourism Recreation Research, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2023.2233073

- Rauken, T., & Kelman, I. (2012). The indirect influence of weather and climate change on tourism businesses in northern Norway. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 12(3), 197–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2012.724924

- Remer, M., & Liu, J. (2022). International tourism in the Arctic under COVID-19: A telecoupling analysis of Iceland. Sustainability, 14(22), Article 15237. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142215237

- Ren, C., James, L., Pashkevich, A., & Hoarau-Heemstra, H. (2021). Cruise trouble. A practice-based approach to studying Arctic cruise tourism. Tourism Management Perspectives, 40, Article 100901. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2021.100901

- Saarinen, J., & Varnajot, A. (2019). The Arctic in tourism: Complementing and contesting perspectives on tourism in the Arctic. Polar Geography, 42(2), 109–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/1088937X.2019.1578287

- Saunders, B., Sim, J., Kingstone, T., Baker, S., Waterfield, J., Bartlam, B., Burroughs, H., & Jinks, C. (2018). Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality & Quantity, 52(4), 1893–1907. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8

- Sharma, G. D., Thomas, A., & Paul, J. (2021). Reviving tourism industry post-COVID-19: A resilience-based framework. Tourism Management Perspectives, 37, Article 100786. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2020.100786

- Silverman, D. (2017). How was it for you? The Interview Society and the irresistible rise of the (poorly analyzed) interview. Qualitative Research, 17(2), 144–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794116668231

- Sisneros-Kidd, A. M., Monz, C., Hausner, V., Schmidt, J., & Clark, D. (2019). Nature-based tourism, resource dependence, and resilience of Arctic communities: Framing complex issues in a changing environment. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(8), 1259–1276. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1612905

- Stamboulis, Y., & Skayannis, P. (2003). Innovation strategies and technology for experience-based tourism. Tourism Management, 24(1), 35–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(02)00047-X

- Stewart, E., Draper, D., & Johnston, M. E. (2005). A review of tourism research in the polar regions. Arctic, 58(4), 383–394. https://dlc.dlib.indiana.edu/dlc/bitstream/handle/10535/3160/Arctic58-4-383.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Tervo-Kankare, K., Kaján, E., & Saarinen, J. (2018). Costs and benefits of environmental change: Tourism industry’s responses in Arctic Finland. Tourism Geographies, 20(2), 202–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2017.1375973

- Varnajot, A. (2020). Digital Rovaniemi: Contemporary and future Arctic tourist experiences. Journal of Tourism Futures, 6(1), 6–23. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-01-2019-0009

- Varnajot, A., & Saarinen, J. (2021). After glaciers?’ Towards post-Arctic tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 91, Article 103205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103205

- Vogler, R. (2022). Revenge and catch-up travel or degrowth? Debating tourism post COVID-19. Annals of Tourism Research, 93, Article 103272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103272

- Vogler, R. (2023). Rules of interpretation – qualitative research in tourism by incorporating legal science canons. Current Issues in Tourism, 26(8), 1214–1223. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2022.2122783

- Wang, J., & Xia, L. (2021). Revenge travel: Nostalgia and desire for leisure travel post COVID-19. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 38(9), 935–955. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2021.2006858

- Wang, W., Chen, J. S., & Prebensen, N. K. (2018). Market analysis of value-minded tourists: Nature-based tourism in the Arctic. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 8, 82–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2016.12.004

- Williams, C., You, J. J., & Joshua, K. (2020). Small-business resilience in a remote tourist destination: Exploring close relationship capabilities on the island of St Helena. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(7), 937–955. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1712409

- Yu, G., Schwartz, Z., & Walsh, J. E. (2009). Effects of climate change on the seasonality of weather for tourism in Alaska. Arctic, 62(4), 371–504. https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic175