ABSTRACT

New Zealanders have long-standing and multifaceted relationships with coasts, including recreation activities in, on and by the water. Leisure scholarship to date has paid little attention to outdoor recreation in New Zealand's fast-growing Asian migrant communities, whose involvement in coastal recreation is relatively low. This study explores Auckland's Chinese communities’ relationship with coastal blue spaces (i.e. the ocean/sea, beach and harbour) through their recreation activities, and the potential impacts on their experiences of cultural identity, belonging and wellbeing. Interviews were conducted with Chinese immigrants and community sport organisations’ representatives to understand the factors that enable and constrain Chinese immigrants’ outdoor blue space recreation practices. Applying Bourdieu's concepts, we identified that Chinese communities’ relationships to coastal blue spaces are impacted by their ‘blue space’ related habitus and cultural capital. Findings also suggest that when facing habitus-field mismatch, participants reject norms and expectations in the field, actively disrupting and challenging them.

Introduction

International research and decision-makers have identified that coastal blue spaces have a vital role in promoting human and more-than-human wellbeing (e.g. World Health Organization Citation2019; United Nations Citation2021; Ministry for the Environment and Stats NZ Citation2022). See also (Nutsford et al. Citation2016; White et al. Citation2020). Coastal blue spaces, which can include coastal ocean/sea, barrier islands, marshes, tidal flats, maritime forests, beaches, cliffs, ports and harbours (Cao and Wong Citation2007), are sites for diverse leisure and sports activities in, on and by the water (Olive and Wheaton Citation2021). International research identifies ‘blue spaces’ as ‘therapeutic’ spaces (e.g. Bell et al. Citation2015; Foley Citation2015; Foley et al. Citation2019), and that recreational activities including swimming, surfing, boating and beach walking can benefit physical, mental, social and emotional wellbeing across demographics including age (Pearson et al. Citation2017; Vitale et al. Citation2022), gender (Elliott et al. Citation2018; Ridgway Citation2022), ethnicity (Olive and Wheaton Citation2021; Wheaton et al. Citation2020) and international migrants (Eyles and Ergler Citation2020).

However, diverse subjects and bodies’ relationships with coastal blue spaces are complex, and specific to place and context (Olive and Wheaton Citation2021). Green and blue public recreation spaces can also be ‘spaces of social ordering and social exclusion’ (Neal et al. Citation2015, 466). Despite the therapeutic and social benefits, for some communities’ coastal blue spaces can be sites of danger, fear cultural contestation (Evers Citation2019; Olive and Wheaton Citation2021; Wheaton Citation2013; Wolch and Zhang Citation2004). Place-based and context-specific research approaches are increasingly being advocated to understand these attachments and engagements, and to reveal how various socio-cultural, demographic, historic, economic and political factors impact upon, and create inequities in access, disconnect and exclusion for individuals and communities (Bell et al. Citation2019; Olive and Wheaton Citation2021).

Our focus here is coastal blue spaces in Aotearoa New ZealandFootnote1, a country where people have strong historic relationships with coasts through work and recreation, economically and spiritually (de Lange Citation2006; Wheaton et al. Citation2020). As New Zealand government departments acknowledge, coastal blue places create strong bonds between people and the places they visit, shape people's local and cultural identity, relieve stress relief and promote wellbeing (Ministry for the Environment and Stats NZ Citation2022). To deepen understanding of attachments to coastal blue spaces through recreation, and of people's sense of belonging among New Zealand's increasingly diverse urban populations, particularly new migrants, our focus is the country's fast-growing Chinese community.

Aotearoa, migration, and demographic change

Since the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi between the British and the majority of Māori tribes, Aotearoa has had a history of white settler colonialism. In the 1970s government agencies committed to biculturalism between Māori and Pākehā (white New Zealanders) (Hayward Citation2023), although the extent of this commitment is contested. However, urbanization and changes in immigration policies over the past two decades, particularly substantial immigration from across Asia (Spoonley Citation2020), ‘have resulted de facto in a multicultural society’ (Ward and Liu Citation2011, 52) with increasing ethnic ‘superdiversity’ (Recreation Aotearoa Citation2018). In the 2018 Census, the ‘Asian’ population made up 15.1% of the total population and was the third largest ethnic group (Stats NZ Citation2019a); it is expected to increase to 26% of the total national population by 2043 (Stats NZ Citation2022). Ethnic Chinese is the largest Asian sub-group, of which 73.3% were born overseas (Stats NZ Citationn.d.). Auckland is home to many of these migrants.

Understanding Chinese immigrants’ relationships to and understanding of coastal blue spaces through their leisure activities is timely. Researchers internationally have called for leisure studies to actively engage with immigrants’ experiences of outdoor activities (Ho and Chang Citation2022, 2); and in New Zealand, Recreation Aotearoa (Citation2018) has called for actions to recognize and include the increasingly diverse population's varied needs and ways of accessing the outdoors. However, to date, research that explores Asian communities’ outdoor recreation in Aotearoa, especially in coastal blue spaces, is very limited. Our research contributes to this gap in the literature by exploring the factors that lead to Auckland Chinese communities’ connection to and disconnection from local public coastal blue spaces and the impacts on cultural identity, belonging and wellbeing.

In what follows, we discuss our Bourdieuan theoretical framework; provide a review of literature focused on New Zealand outdoor leisure engagement and ethnicity; and then introduce our interpretative and place-based research methods. Our discussion presents four research themes, followed by research implications and conclusions.

Conceptual framework: using Bourdieu's concepts to understand migrants’ leisure practices

Since the 2000s, the conceptual work of Pierre Bourdieu has attracted considerable interest among scholars of physical culture, physical education and the sociology of sport (e.g. Brown Citation2006; Laberge and Kay Citation2002; Thorpe Citation2010; Tomlinson Citation2004; Bandeira, Wheaton, and Amaral Citation2023). Here we draw on Bourdieu's concepts of capitals, habitus and field, to understand immigrants’ pre-existing dispositions and leisure preferences in their homeland and as their living context changed through migration to a different cultural field (Aotearoa). A brief explanation of Bourdieu's idea, and how they have been adopted follows.

In Bourdieu's theories, a field is a social arena, such as the field of sport and physical culture (Bourdieu Citation1978; Citation1999; Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992). Social actors occupy different positions in a field and are engaged in struggles to accumulate the resources that are valued within it (Kay and Laberge Citation2002). Capital refers to the resources in the field; Bourdieu identified how various forms of capital (i.e. economic, cultural and social) are required to participate in and access particular leisure and sports activities (Bourdieu Citation1986). For example, in the context of migrants, Smith and colleagues’ (Citation2019) systematic review illustrates that while sport is an important social context for the negotiation of cultural capital, ‘migrants’ cultural capital can be both an asset to, and a source of exclusion from, sport participation’ (851). We discuss the concept of cultural capital in more depth in the discussion of our findings.

Habitus is explained as ‘systems of durable, transposable dispositions’ in different fields (Bourdieu Citation1977, 72). Research has emphasized the significance of childhood experiences, education and parenting in the development of an individuals's sporting habitus and therefore in the reproduction of sporting practices (e.g. Haycock and Smith Citation2014; Kay Citation2009). People's daily practices are the result of the interaction of their habitus and capital in the given field (Bourdieu Citation1984). The interaction between capitals, habitus and field helps to explain social groups’ different preferences of participation and accessibility in leisure and sports activities, and how such leisure ‘choices’ are related to economic, cultural and social resources. For example, the Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) in London, with its renowned membership waiting list, can be understood as a classic form of reproduction of elitism. A network of ‘old boys’ operates in the fields of Lord's Cricket Ground and MCC, which contains and sustains an exclusive and privileged class-based habitus marked by economic, social and cultural capitals (Tomlinson Citation2004).

Bourdieu's conceptual ideas are not without critique, particularly his focus on the reproduction of social class, without recognizing the importance of the ‘stratifying factors’ embedded within habitus including ‘gender, age, region, and (to a lesser extent) ethnicity’ (Weininger Citation2004, 153). Therefore, scholars have built on Bourdieu's concepts to explore the gendered and racialized aspects of (body) habitus and how they are reproduced in institutional spaces including sport (Brown Citation2006; Erickson, Johnson, and Kivel Citation2009; Puwar Citation2004; Thorpe Citation2009; Wacquant Citation1995) and education (O’Shea Citation2015; Yosso Citation2005). As Puwar (Citation2004) explains, no matter how a racialized body may possess the field-specialized capitals (such as sporting knowledge or skill), gender and ‘race’, remain significant markers that differentiate those bodies as outsiders, as ‘space invaders’ and mark their marginal positions in the field. For example, in Burdsey’s (Citation2004) research on football, habitus helped explore the degree to which British Asian individuals share or are ‘invited to’ participate in the ‘dominant cultural habitus’ (764), and the ways in which they are excluded in these sporting spaces. In the USA, Bourdieu's insights have helped gain an understanding of particular minority ethnic groups’ absence from green (Erickson, Johnson, and Kivel Citation2009) and blues spaces (Phoenix, Bell, and Hollenbeck Citation2021; Wheaton Citation2013). For example, some African Americans associated green nature-based spaces (e.g. forests) with fear, rooted in the history of slavery, segregation and racism (Finney Citation2014; Erickson, et. al. 2009; Harper Citation2009). Beaches in the USA were also racialized spaces that can operate as places of white retreat (e.g. Phoenix, Bell, and Hollenbeck Citation2021; Wheaton Citation2013). Following Puwar (Citation2004), Wheaton (Citation2013) describes African American surfers in California as ‘space invaders’ who have to navigate the racialized space of surfing, and challenge the existing norms that white bodies are the ‘natural’ occupants of this space. In Aotearoa too, ‘brown’ (Māori/Pacific) surfers’ bodies can be perceived as ‘out of place’ (Nemani and Thorpe Citation2016).

Building on these insights, our study considers Chinese migrants’ habitus, and cultural and physical capital in the ‘field’ of Aotearoa's blue space recreation (i.e. the physical spaces from the sea to shoreline, and the various activities that take place). As the sea and coastal activities are embedded in New Zealand's dominant culture and people's sense of identity (Wheaton et al. Citation2021), a wide range of blue space-related cultural resources, including the embodied, objectified and institutionalized forms (Bourdieu Citation1984) are key forms of capital in the New Zealand social field. We explore how blue space recreations in Aotearoa are guided by diverse influences from one's habitus, and the desires and struggles for capital accumulation, and consider the extent to which ethnic Chinese individuals share, or are capable and able to participate in the dominant cultural habitus, and the ways in which they are marginalized or excluded. In addition, we explore if adult immigrants’ habitus has changed, or not, in the field of Aotearoa's blue space. Bourdieu explored the conditions of change through the ‘hysteresis effect’. Hysteresis happens when there is a mismatch or disruption between habitus and field, when they are ‘out of sync’ (Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992, 130). Some studies have explored the notion of hysteresis to analyse agents adapting to changes imposed upon them, resulting in questioning and changing their habitus (e.g. Barrett Citation2018; Singh Citation2022). We suggest that Bourdieu's notion of hysteresis, and the potential for change of practices is useful to perceive immigrants’ relationship to blue spaces as a dynamic link between social structure and immigrants’ agency, and an ongoing process connecting the past, present and future experiences.

Nature-based outdoor leisure in Aotearoa: the dominance of white ethnicities

The islands of Aotearoa are relatively unpopulated with green and blue spaces being relatively accessible to most communities. Government organizations such as New Zealand Immigration and Tourism New Zealand, have long promoted the country as a ‘clean and green’ outdoor paradise of natural wonders for visitors and migrants alike (Foong Citation2021). People in Aotearoa have high levels of engagement in outdoor recreation and sport (Department of Conservation Citation2020; Sport New Zealand Citation2015), which are embedded in family, schools and community practices (Wheaton Citation2021). According to Sport New Zealand's (Citation2015)Footnote2 national data, coastal blue spaces, particularly the beach and sea, are popular nature-based recreational spaces; 35.9% of their survey participants used the beach, and 28.8% in or on the sea.

However, patterns of dis/engagement differ across socio-demographics, including ethnicity, gender and age (Wheaton Citation2021). Participation in outdoor recreation is overrepresented by white ethnicities and those with higher incomes and higher education (Espiner et al. Citation2021, 37) across all activities except fishing and hunting which are popular with Māori participants (Recreation Aotearoa Citation2018). In Aotearoa, as elsewhere, ‘nature’-based leisure is often romanticized in ways that obscure the privileges and barriers to access to these spaces (Wheaton Citation2021) including financial security for the often costly material objects needed, and ‘membership in a social stratum that normalizes outdoor recreation’ (Ho and Chang Citation2022, 573). As Ho and Chang (Citation2022) explain in the Canadian Settler Colonial context but is also pertinent for Aotearoa, dominant Western cultural narratives of the outdoors ‘stems from a specific cultural construction of “wilderness”, which is based on the “privileged experiences of white middle-class settlers” (570), and a cultural heritage that “construes natural spaces as already mastered by human “pioneers”’ (574). These discourses that mythologize (a Colonizing) history, and that privilege masculinity and whiteness need to be troubled (Beames, Mackie, and Atencio Citation2019; Laurendeau Citation2020; Wheaton Citation2021). The diverse and culturally-specific engagements related to outdoor activities need exposing, showing that the perspectives of the dominant group (Pākehā) is not the only valid experience.

Māori, the indigenous population of Aotearoa, have historically held strong connections to the natural world, and gained a sense of identity and belonging from their connection with the natural environment (Durie Citation1998; Phillips and Mita Citation2016; Watene Citation2016). Māori have a more holistic understanding of more-than-human environments than European worldviews, impacting attitudes to and practices in blue spaces as sites for recreation, food source, and spiritual connection with ‘nature’ and more-than-humans (Hoskins and Jones Citation2017; Wheaton et al. Citation2020). Recognizing these histories, and different ontologies and knowledge systems is essential for understanding the ways in which Māori continue to develop and express their relationships to the natural world, including through forms of recreation (Waiti and Awatere Citation2019; Waiti and Wheaton Citation2022; Wheaton et al. Citation2020). Surfing, fishing and seafood gathering are popular blue space practices among Māori communities, and waka ama, the sport of paddling traditional Polynesian outrigger canoes, has seen somewhat of a resurgence in popularity (Liu Citation2021; Waiti and Wheaton Citation2022; Wikaire and Newman Citation2013). Alongside this Māori recognize that along with the privileges the environment provides come the responsibility to care for it and maintain it for future generations (Kawharu Citation2000).

Asian migrants’ experiences of ‘nature-based’ outdoor recreation

Regarding Asian migrants specifically, international research shows that Asian immigrants in North America are often less engaged with the dominant outdoor recreation practices, and experience barriers to participation due to both economic constraints and experiences of discrimination (Ho and Chang 2022; Shores, Scott, and Floyd Citation2007). In Aotearoa, national survey data also shows lower participation rates in Asian ethnicities (than Pacific, Māori and European) across nationally popular blue space recreation activities including surfing/body boarding, sailing/yachting, canoeing/kayaking and fishing (Department of Conservation Citation2020; Sport New Zealand Citation2020). A Recreation Aotearoa’s (Citation2018) survey identified that the main obstacles for Asian immigrants to engage in outdoor recreation activities are cost, time, transport and companions (see also Department of Conservation Citation2020). However, in-depth qualitative and place-based research understanding Asian migrants’ experiences of outdoor recreation and public outdoor spaces in Aotearoa is limited.

A key exception is Lovelock et al.'s (Citation2011; Citation2012) research focused on Asian immigrants from China, Korea, Indonesia, Japan and India and their experiences of ‘nature’-based recreation. Lovelock et al. (Citation2011) show that a range of socio-economic and cultural barriers contribute to these immigrants’ under-representation across most of the dominant outdoor recreation activities in Aotearoa. The authors highlight that national parks were often perceived as ‘alien’ and ‘frightening’ places, where these immigrants did not feel comfortable. These findings reflect international research (noted above) showing that cultural narratives about ‘nature’ as places of freedom, fun and adventure were not shared by some ethnic groups (Ho and Chang 2022; Wheaton Citation2013; Citation2021; Laurendeau Citation2020; Erickson, Johnson, and Kivel Citation2009; Harper Citation2009). Regarding blue spaces specifically, Lovelock et al. (Citation2012) found that Asian immigrants ‘did not rate water amenities as an important feature of natural recreation settings’ (222). Moran and Wilcox (Citation2013) surveyed 570 Asian immigrants, mainly Chinese (45%) and Korean (35%), and found that 43% of them had never participated in any water-based activities prior to coming to New Zealand. Nearly one-third of the respondents self-reported that they could not swim, and nearly half of them (45%) avoided swimming in open water (Moran and Wilcox Citation2013).

In summary, this research demonstrates that diverse ethnic groups, including immigrants, have different perceptions of fun, free time, relaxation and recreation and capabilities to participate in nature-based outdoors (Lovelock et al. Citation2011; Citation2012; Moran and Wilcox Citation2013). Furthermore, immigrants’ different attitudes and capabilities were recognized to have negative impacts on these individuals and communities. First, disengagement from outdoor recreation contributes to Asian New Zealanders’ sense of feeling different from ‘Kiwis’ (Lovelock et al. Citation2011). As these authors (2011) argue, ‘[B]eing able to locate one's self in nature-based settings is central to migrant integration’ in New Zealand (513). Second, many Asian migrants lacked the skills and knowledge to engage safely in the outdoors (Lovelock et al. Citation2011; Moran and Wilcox Citation2013). In terms of risk and safety in coastal blue spaces, Asian ethnic groups (along with Pacific and Māori) are disproportionately over-represented in fatal and non-fatal drowning cases over years (Drowning Prevention Auckland Citation2021; New Zealand Surf Life Saving Citation2020). This situation has been attracting attention from water safety advocates and national media (e.g. Church Citation2023; Wheaton and Liu Citation2022). As the manager of a marine education centre in Auckland has advised, the opportunities for new migrants to navigate the outdoor environments with safety and sustainability are limited (Foong Citation2021). Given these pressing issues, and the paucity of research on migrants’ experiences of recreation and wellbeing in public blue spaces in Aotearoa, there is a pressing need to deepen our understanding of the varied needs and ways of accessing the outdoors by Aotearoa's increasingly diverse population (Recreation Aotearoa Citation2018).

Research methodology

This interpretative, place-based research was conducted in Auckland, Aotearoa's largest and most ethnically diverse city. In 2018, 11% of Aucklanders identified as Chinese (Stats NZ Citation2019b); 56% of which were born in China (96,540 out of 171,309) (Auckland Council Research and Evaluation Unit Citation2020). Often referred to as ‘the City of Sails’, Auckland is situated on an isthmus surrounded by a diverse coastline estimated 3200 km (Roberts et al. Citation2020). Blue spaces from promenades and wharves to ocean beaches, are geographically accessible public spaces for residents. According to the Department of Conservation report (Citation2020, 12), Aucklanders had ‘higher participation in water-based activities than all New Zealanders combined, which was unsurprising since beaches and rivers are easily accessible to them’. Swimming, surfing, paddling, boating, fishing, seafood gathering and beach walks are all prevalent informal sports and recreational activities.

To explore individual experiences of coastal blue spaces, and barriers to engagement, semi-structured interviews were conducted with 16 self-identified Chinese community members (10 females, 6 males) who lived within a 20-minute drive to the coast (see ). Individuals were recruited either via social media-based advertisements in both English and Mandarin, or snowball sampling, starting with the Authors’ direct contacts. The interviews were conducted face-to-face, or via Zoom in either English or Mandarin, then transcribed and translated into English by Author 2 (A2), who is a Chinese national and competent in these languages. We asked interview participants to prepare relevant photos of their coastal engagements and show them to researchers during the interview.Footnote3 As Cosgriff (Citation2023) outlines, photographs are a useful tool in exploring peoples’ relationships with local beaches.

Table 1. Participants from Chinese communities in Auckland.

Our participants were predominantly from mainland China (14 out of 16), and had lived in Aotearoa between 3 and 35 years. Fifteen were first-generation immigrants who migrated in their adulthood and arrived in the country aged 20 and above. Seven are now permanent residents or citizens. One was a 1.5-generation immigrant, who migrated with their parents at school age. Reflecting Chinese migration waves to Aotearoa from the mid-1990s (see Wang Citation2018), these individuals were largely well-educated. Eleven participants had completed undergraduate degrees either in Aotearoa or China, and seven participants held postgraduate degrees. However, as Friesen (Citation2019, 24) outlines, although recent migrants from China have tended to gain permanent residency in Aotearoa ‘on the basis of relatively high educational, skill or capital import qualifications’, many do not end up working in their areas of qualification, due to difficulties including language, lack of ‘Kiwi’ experience, and employer attitudes (Friesen Citation2019). Our interviewees' occupations included university students, university staff, government employees, medical professionals, early childhood teachers, builders, car washer, unemployed, and retired.

In addition to these interviews, we contacted key local organizations in the sport, play and active recreation sector that specialized in providing coastal activities, marine education and water safety training to Asian and Chinese communities. Both researchers interviewed 10 representatives of seven local organizations (). These included outdoor education (including marine education and water safety education), sport trusts and a Chinese-owned yacht charter company. Many of these individuals had long-term personal experiences working closely with the Asian community. They provided detailed knowledge about outdoor and water-related activities, and organizational and sectoral views of the Chinese community's coastal blue spaces activity engagements. Additionally, seven of them were Chinese first- and 1.5-generation immigrants from three different regions and countries; hence also insiders of the wider group of Chinese immigrants.

Table 2. Representatives (10) of local organisations (7) in the sport, play and active recreation sector.

In summary, our sample represented a broad range of Chinese migrants in Auckland, including those of different ages, length of stay and English language competence. Nonetheless, we are mindful that the ethnic category of ‘Chinese’ in Aotearoa is diverse, including those who have settled in the country for several generations, and new immigrants from across China and countries as diverse as Malaysia, Indonesia and Australia.

Our analysis was guided by the thematic analysis process outlined by Braun et al. (Citation2019) and driven by Bourdieu's theoretical concepts, and the wider literature on place-based wellbeing in blue space (Elliott et al. Citation2018; Olive and Wheaton Citation2021; Vitale et al. Citation2022). A deductive coding or theoretical ‘top-down’ approach was initially applied to the interview transcripts, focusing on the relationship between capitals, habitus, and field to interpret participants’ blue space experiences and practices. Then, the related codes were grouped into conceptual areas and the initial themes were formed based on the grouped codes. A2 conducted the initial coding; then A1 reviewed the themes. This process encouraged both authors to reflect upon and also explore alternative explanations of the findings. In our discussion below we discuss four key themes which illustrate Chinese immigrants’ blue space habitus, capitals and practices and their dis/connection to coastal blue spaces. First, we briefly describe the different blue space recreational engagements in this interview cohort.

Chinese immigrants’ blue space practices in Auckland

Participants in this research did visit local blue spaces including the harbour at the downtown waterfront, and also drove to beaches on the North Shore and West Coast. This reflects research conducted by the Department of Conservation (Citation2020, 12), which reports that Auckland's new migrants would travel to get to locations with walks and beaches. However, it is notable that the frequencies of these blue space visits were very diverse in our cohort ranging from ‘daily’ and ‘twice a week’, to ‘occasionally’ and ‘hardly ever’.

Reflecting Sport New Zealand’s (Citation2020) national data showing low Asian participation in informal water-based leisure, Chinese migrants in this research rarely mentioned participation in open-water swimming, surfing, paddling/kayaking or sailing. Rather, these migrants’ coastal blue space recreation mostly took place at the beach or shoreline, including walking/hiking, picnics, and dancing. Seafood harvesting and/or fishing was a popular recreational activity that all participants we interviewed had tried, with fishing on land popular among men. These findings reflect Moran and Wilcox (Citation2013) who found that even though Asian new immigrants are more active in water recreation in Aotearoa than in their home countries, they were still not high-frequency participants. We also found that activities on or in the water were only popular when offered as organized activities by leisure providers targeting Asian communities.

Previous survey research has identified that cost, time, transport and companionship are the main obstacles for Asian immigrants to engage in outdoor recreation (Recreation Aotearoa Citation2018). In informal conversations with older participants, who were also grandparents, several identified that they have ‘no time to go that far since they have to look after the grandchildren’. Yet most of our interviewees stated that accessing coastal blue spaces was not ‘difficult’ for them. Participants varied in terms of their economic resources or capital, and for some ‘cost’ was a barrier. However, many argued that ‘finance’ was not a major barrier. For example, AK, an organizational representative working with Chinese communities, observed that when working in a badminton association, Asian parents were prepared and able to spend a lot of money on their children's training. She outlined that ‘paying $60, $80 an hour for private coaching for their kids’ was typical and that ‘some of them can even afford it twice a week’. They also bought expensive racquets, which ‘can cost you $500’.

As we discuss further below, migrants’ homeland habitus had a strong influence on their preferred leisure choices. Most of the first-generation immigrants, particularly older people, said that they preferred land-based and indoor leisure activities that were popular in China such as line dancing, Tai Chi, table tennis, badminton, chorus, and Chinese festival celebrations. It is also notable that four older Chinese community members declined to be interviewed because they said they don't go to the beach; they prefer indoor activities near home. As Recreation Aotearoa’s (Citation2018) research also suggests, Asian migrants value the social activities that allow them to spend time with family, socialising and establishing connections. As we unpack further in the following sections, diverse, intersecting influences contributed to their preference for shore-based activities including concerns about safety in the water, fear of getting tanned and a lack of finance, skills and knowledge.

Homeland habitus: concerns about water safety and getting tanned

Following Bourdieu (Citation1984), childhood experiences and family influences and values are foundational to acquiring the habitus for sport and leisure practices such as visiting the beach (see also Wheaton Citation2013). As one of the 1.5-generation migrants explained:

Being a kid in New Zealand is barefoot, mud, dirt, the whole lot. That is New Zealand culture. If you grew up in New Zealand, and it's almost like a right. You know it's like, ‘how was your weekend?’ ‘Oh, I went down to [place], and I went out on this boat’ … I grew up on boats, kayaking, sailing. Friends kind of genuinely say ‘you’re more Kiwi than I am.’ But that was just my upbringing.

Concerns about water safety were expressed by all first-generation migrants, across age groups and gender. Most interviewees had lived in inland urban areas and didn't participate in coastal activities while growing up. Therefore, as an organizational representative reported, middle-aged and senior people who came to New Zealand, ‘they’re not familiar with the environment … New Zealand is around it all or by water’. In addition to this lack of exposure, many came to New Zealand with a belief that it was dangerous to swim in ‘natural’ places. In China, many had experienced, and conformed to written and unwritten ‘rules’ around such water bodies being dangerous and off limits. For example:

Since childhood, I have been told the reservoir and river are dangerous for swimming, and don't go down there. (Zhi, 3 years in NZ)

Every summer there’re children who drowned in my hometown, because many of them didn't listen to their parents and went swimming in the reservoir. (Mandarin 4 years in NZ)

Another common coastal blue space activity among European New Zealanders is sunbathing at the beach (Eames Citation2018; Johnston Citation2005). Johnson suggests that since the early 1900s, sunbathing ‘became a national Pakeha pastime and even became recognized as a marker of good citizenship’ (Johnston Citation2005, 112). Nevertheless, sunbathing was not popular among this Chinese group, and the fear of getting tanned identified by research participants, including the organizational representatives, as prevalent particularly for Chinese women, and the ‘older generation’:

The fear of getting tanned, you know the damage to the skin, stuff like that. You sometimes sort of see Asians are like the only fully clothed people on a beach and under umbrellas. (Mel, organisational representative)

My daughter and I do not feel like going to the beach. She said you’ll get very dark complexion and later your skin peels. (Annie, 21 years in NZ).

Figure 1. Chinese and Asian people at the beach in warmer months (photos provided by participants and taken by the researcher).

Figure 2. Chinese and Asian people at the beach in warmer months (photos provided by participants and taken by the researcher).

Figure 3. Chinese and Asian people at the beach in warmer months (photos provided by participants and taken by the researcher).

Fully clothed Chinese immigrants embody a habitus that does not match the informal and taken-for-granted ‘rules’ of the New Zealand beach, and marks them as different. Chinese immigrants, especially women, valued bodily dispositions that align with traditional Chinese cultural norms; they value fair skin or a light complexion which enhances one's social and sexual advantages and privileges (Dixson et al. Citation2007; Xie and Zhang Citation2013). While in recent years, having a tan has become more popular in Asian cultures seen as a sign of a healthy lifestyle (Chong Citation2013), these Chinese immigrants practised bodily expression of a gendered and ethnic habitus valued by traditional Chinese culture. The tan – or avoidance of getting tanned – captures the importance of certain embodied features as forms of physical and cultural capital (Shilling Citation1991), and how these dispositions become a barrier that prevents many Chinese immigrants from participating in common practices (i.e. sunbathing, playing in swimwear/togs) that the dominant culture (Pakeha and Māori) takes for granted.

Chinese migrants’ struggles for blue space capitals

Habitus is also an evolving concept that changes along with the accumulation of capital resources including economic, social and cultural within a field, or physical and social space (Liu and Li Citation2020). Cultural capital is seen to play a key role in the social ‘distinction’ of leisure practices (Bourdieu Citation1984) yet is perceived as being more difficult to access (Liu and Li Citation2020, 2). Bourdieu (Citation1984) outlines three forms of cultural capital: the embodied, objectified and institutionalized forms; we consider each one's role in constituting what we term blue space capital in the New Zealand field. We highlight that objectified cultural capital can be directly obtained by converting economic capital into material possessions like sporting equipment such as boats or kayaks. Institutionalized forms of capital such as educational qualifications or water safety training can provide blue space knowledge and skills. However, as we discuss below, the embodied cultural capital including meanings, values, functions, specialized skills (particularly what Shilling [Citation1991] terms physical capital), knowledge and experiences, needs a relatively long time and considerable effort to learn, appreciate and understand (Bhugra, Watson, and Ventriglio Citation2021).

‘People I know don’t have boats in the “City of sails”’

Doing ocean activity is a particular local culture. That's why Auckland is called the ‘City of Sails’. (Denny, 28 years in NZ)

Participants in our research acknowledged that boating and sailing were popular blue space activities in Auckland; however, they recognized that these were recreations limited to the wealthy:

The people I know don't have boats in the ‘City of Sails’. For me, boating is an activity for relatively rich people. I genuinely don't think it's affordable to all. (James, 8 years in NZ)

However, despite this, some Chinese did engage in sailing and boating, and also bought boats, which as revealed in our interviews, involved attempts to accumulate the economic, and cultural resources valued within the dominant field.

‘Boating and fishing as a way to show off your wealth’

Liu and Li show that a group of ‘new rich’ has emerged in China over the past decades, which ‘creates tremendous possibilities for individuals to tailor their leisure activities and lifestyles’ (Citation2020, 1). Denny observed, yachts were ‘for younger-generation Chinese who have money and time’. While these ‘superrich’ Chinese were not widely represented in our sample, some participants appeared to have an interest in exchanging economic capital for objectified forms of cultural capital via purchasing boats. Acknowledging the conspicuous consumption of boats as a signifier of wealth and status (c.f. Bourdieu Citation1984), Mai, an organizational representative pointed out that richer Chinese new immigrants buy boats for two interests; either for wealth accumulation – they ‘treat it like a property investment opportunity’, or ‘to show one's social status and wealth to friends’. Similarly, Sun (4 years in NZ) explained:

I know this local family. Three brothers and their father bought a boat. They definitely spent more time and energy on this boat than their families. Every year the ship went to the pier to repair and repaint, and they pay all kinds of fees for that. […] I have read several articles written by Chinese, saying that there are only two happy days when owning a boat. One day is when you buy it, and the other day is when you sell it.

Lacking blue space cultural capital: developing a ‘feel for the game’

However, buying a yacht is different from engaging in boating. The economic capital may easily convert into the material (the boat) and symbolic forms of cultural capital (status), but not the more physical and embodied forms of cultural capital such as knowledge, skills, and the desire to learn to sail. Sun pointed out what she saw as key differences between ‘local’ New Zealanders and Chinese boat owners:

People here … drag a small boat behind their cars, or put in their yards and garages. On holidays, they take the boats out. We don't know how to handle boats. Locals started boating since little and they like doing it. Locals may not be very rich, but they know how to put the boats on the trailer or on top of the car since little.

we Chinese occasionally participate […] it's like buying the experience. We paid for the experienced captain to take us out and we can show off this trip by taking photos on the boat. “Yeah, whole day fishing at the sea, very happy”, [laughs].

More widely, many participants recognized that participation in blue space recreations including boating, kayaking, surfing and SUP paddling involved acquiring cultural capital that was not part of their past life experiences or habitus:

Sailing was not part of Chinese immigrants’ experience and so parent won't send their kids to sailing schools. I guess people tend to do what they already know. (Penny, 20 + years in NZ).

I have no idea how to surf and don't know where to surf. I can't imagine myself doing it at all. It involved so much knowledge … I don't even know how to get started. Perhaps due to the environment in which I grew up, I had exposure to it since little.

I felt happy to paddle on calm water, especially [if] someone guides me, I would have more confidence. If going into the deep area, I had to be with a coach or a group of people. I dared not to go to the deep water alone. (Janet, 17 years in NZ)

As the representatives from sport and leisure organizations also argued, contrary to dominant stereotypes of Asian communities being uninterested in blue space recreation, demand for organized activities they provided in the Auckland Asian community was high. Mel explained, when we put on activities like ‘have a go’ days for sailing, or SUP, ‘it always got oversubscribed. It shows that the interests are there’. Rui Xue agreed ‘there is definitely a great demand from the community to learn how to be safe in and around water’. These findings reiterate wider research on the cultures of informal sport, showing that the barriers to participation are complex (Gilchrist and Wheaton Citation2017), and that often structured programmes are needed to provide initial experiences for some groups (Foong Citation2021; Moran and Wilcox Citation2013).

Participants also observed that without this knowledge and cultural capital, some Chinese were very unprepared when conducting blue space activities, so could behave in ways that were unsafe. Hus, an organizational representative, said ‘there’re stories of people wearing jeans in the water and weighing them down’. Mai stated that ‘Chinese are so daring. They’re really brave. They wanna give it a try’. He explained how they might engage in ‘fun’ competitions at the beach to ‘see how deep I can go’, which could be risky. No surfing referred to this boldness as deriving from the habitus of the homeland. She explained that ‘the ancient Chinese respected nature and the traditional teachings talked about the human-and-nature relationship’. However, she said in contemporary times, attitudes have changed. She pointed to a Chinese government political slogan advising ‘man can conquer nature’. These attitudes, particularly amongst Chinese men, are perhaps reflected in the high drowning rates of male Asian New Zealanders (Water Safety NZ Citation2021). High-profile media reports of boat accidents characterized the Chinese male casualties as unprepared, lacking knowledge and skill (Tan, Oct 21; Citation2022). Mandarin commented how such incidents show how daring and ignorant about the sea contemporary Chinese people could be: ‘they have no respect for the sea and no reverence for nature’. Such stories, both in the media, and shared in communities, appeared to further perpetuate some Chinese immigrants’ self-identification as ‘lacking in blue space capital, reproducing their dis/connect.

In the next section, we examine these immigrants’ shifting relationship to coastal blue spaces in more depth.

Immigrants’ shifting relationship to coastal blue spaces

Bourdieu (Citation1977, 126) argued that habitus ‘is durable but not eternal’. We suggest that Chinese immigrants’ relationship to blue spaces is also an ongoing changing process initially triggered by the ‘mismatch’ between the habitus formed in China's field, and the field of Aotearoa. However, as different capitals are accumulated in the new field, the habitus becomes restructured.

Seafood harvesting and/or fishing was a ‘new’ recreational activity that all participants we interviewed had tried. Denny said with great excitement, ‘finding seafood at the beach, we love doing this. This is a good activity. Yes, yes, we do this a lot […] and even my 80-year-old parents-in-law love to go’. Zhi explained, there was an abundance of natural resources (fish and seafood) along the coast:

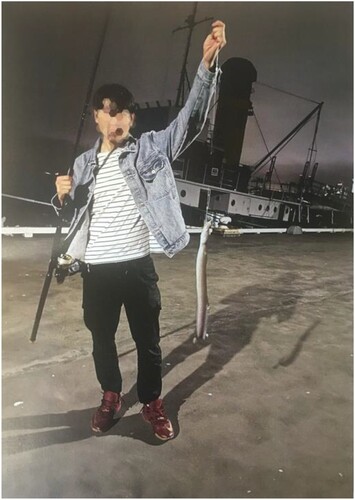

I had never fished before I came to New Zealand, but I have always wanted to do it. … So I asked a friend to teach me how to tie the hook, how to cast, and so on. Last year, I bought a fishing rod and went fishing with him. (See )

While beyond the scope of our discussion here, it is important to note that seafood gathering could, and often did lead to local conflict, particularly with Māori communities for whom kaimoana (seafood) gathering is a prevalent cultural practice, aligned with Mātauranga Māori (Māori worldview) such as being kaitiaki (guardians) of nature. As the manager of a marine education centre explained, there were widespread stereotypes about Asian communities as ‘locusts’ who ‘came to raid our seabeds’, implying that Asian migrants’ lacked blue space capital about ‘rules’ for sustainability.

Individuals’ negotiation between habitus and field was dynamic and ongoing, which led to them engaging in both old and new practices. As Korver explained, now his family are new immigrants, but perhaps 10 years later they will have different attitudes to and practices of blue space activities. Mary, a dance group leader explained, that she organized picnics at the local beach for her dance group. ‘After eating, we put on customs, turned on the music and danced to the music at the beach … sometimes local people came to join us’. She explained, that if she had just organized an outing to the beach, ‘some group members wouldn't join’, but if she said ‘we go picnic and dance at the beach’ she got many more people joining. Mary found a way to enjoy different styles of leisure activities by accommodating familiar practices (dancing) to a new field (the beach). In this way, habitus can be restructured in a new context, but the pre-existing dispositions are durable. Similarly, comparing his prior sporting experiences with his new interest in fishing, Zhi said ‘land-based sports, especially basketball and bodybuilding, are the two things I want to invest time to do, and I will do these for a long time, but ocean-based sports, I will do it occasionally, or just experience once’. The preference for land-based leisure is the ‘specific inertia’ (Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992, 130) of Zhi and other participants’ homeland habitus. Mandarin reflected that while water sports were still not that appealing to her, ‘New Zealand has changed some of our perceptions and attitudes towards water sports’. Therefore, change also happened at the conceptual level, influenced, in Manadrin's case by personal experiences and also the media:

Social media only show us beaches and beautiful women, or beaches and young men with 6 packs … . We realised that ‘oh, everyone can do water sport’, especially seeing [person]. Oh gosh, a 60-year-old beer-bellied grandpa-like academic go surfing. He doesn't have a chiselled body or tanned skin. You saw him and you won't think he's a beach boy, and you thought he was just someone who sits in the office all day long. He loves surfing. For me, this's just like ‘you can surf if you want to’, just like you go play table tennis and badminton if you like to do it. [Mandarin]

The length of time younger and mid-aged migrants have resided in Aotearoa is clearly related to the degree of adaptation to this new cultural field, and the degree to which immigrants’ habitus has changed. For example, the two 1.5-generation immigrants (Centre Manager & Carlos) in our sample, had expressed their familiarity with the coast and water activities. As they grew up in Aotearoa they experienced quite ‘typical’ outdoor experiences, such as ‘going to the beach, doing what you grew up doing as a child in New Zealand. I grew up on boats, kayaking, sailing’ (Centre Manager). Carlos had also experienced visiting the beach with his family, although this had not included in-water activities:

I grew up in [place in NZ], and we are actually very close to the beach. So we would go there at least once every two to three months […] especially in the summertime, with my siblings, and sometimes with other people too, with family members mum and dad and things. We wouldn't swim on the water, but we’ll definitely go around and play in the sand, walk along by the shore itself, run by the waves … we’ll just do a lot of exploration and things.

Parents as drivers of change: supporting children's blue space habitus

Even though participants/parents’ habitus may not align with the norms and values in the field of coastal blue space and hence see it as a field ‘not for them’, they recognized that it could be important for their children. Therefore, despite many conforming to the stereotype of ‘over-protective Asian’ parents (AK), expressing being concerned about drowning in the water or getting a suntan, they also supported their children to shape their blue space habitus and follow certain values within the host country. As Hong Lu (organizational representative) argued, ‘Most Asian parents want their children to learn to swim. Some Asian parents even have one-to-one private lessons for their children’. However, parents’ desire to develop their children's blue space habitus in this way often included a range of often conflicting factors including assimilating in a new culture; the impacts of being non-white immigrant status, including discrimination; and parents’ attitudes towards the purpose and value of education and leisure. For example, Hong Lu suggested parents’ motivation for their kids to learn to swim was not just to be safe; but ‘because they want their children to be competitive everywhere. … I don't know why, but they do have high expectations of their children’. Similarly, Rui Xue said ‘middle-aged and older people’ have ‘high expectations for their kids’, especially in the school environment. Chinese parents’ particular ‘dispositions’ to parenting and education derived from their homeland cultures (i.e. being competitive, with high expectations), was widely evident in our discussions; educational outcomes were highly valued, and children expected to succeed in the New Zealand school system (also see Ho and Wang Citation2016). A representative of the Chinese Conservation Trust explained, ‘Many immigrants have come to NZ to improve their lives via hard work in business’ so giving up their time to focus on activities like sport, and leisure without financial reward ‘doesn't make sense to many immigrants’ (quoted in Recreation Aotearoa Citation2018, para 5). These participants’ immigrant status impacted their attitudes about the values of education and leisure. They guided their children on a path to having a ‘successful life’, (i.e. financial security) via acquiring institutionalized forms of cultural capital which would enhance their chance of working in a high-status profession field where they could accumulate economic capital (see also Lee and Zhou Citation2015).

However, research has also shown that some ‘migrants live in a social and cultural world that consists of far more than economic calculations’ (Kelly and Lusis Citation2006, 844). Some younger Chinese immigrant parents (in their 30s and 40s) who participated in this research also showed more complex attitudes towards academic learning and achievement. For example, Sun and Korver, Ya and Fu, and Carlos recognized the hardship for immigrant families to settle down and the importance of children's education, but they also aspired to support their children to enjoy ‘kiwi’ outdoor lifestyle and leisure, including blue space practices.

When supporting their children’s blue space practices, some parents also began to reshape their own habitus and strengthen their relationship with the local coastal blue spaces, even though it may be temporary.

Although I don't make a lot of money, I am more willing to try some new things. For example, last Christmas, I paid for my son, my nephew, and another kid to learn sailing to have a basic understanding of sailing. I want my son to experience local culture and mainstream culture. (Denny)

Due to the cultural differences between the East and the West, frankly speaking, taking my kids to a sailing school and spending a whole day there was boring. That's why I learnt to kitesurf, cos I thought he was out on the boat, and I could surf out to watch him, so I won't feel the day is too long and boring, and I feel like participating together. (Korver, 4 years in NZ)

Final discussion

In summary, our research revealed a range of factors that lead to these Chinese immigrants’ disconnection from and connection to coastal blue spaces. The factors limiting their blue space practices lie in a range of interrelated historical, cultural, ideological and economic factors, with potential impacts on their experiences of cultural identity, belonging and wellbeing.

We have argued that Bourdieu's concepts of habitus and capitals are productive for understanding the embodied experiences of inclusion and exclusion felt and experienced in local blue space amongst non-dominant groups such as Chinese immigrants. We have shown that these first-generation Chinese adult immigrants do not have the prevalent and taken-for-granted outdoor experiences that are typical of many Pākehā and Māori families in Aotearoa such as visits to beaches, swimming, playing, sunbathing, fishing, boating and kayaking. The ‘taken-for-granted’ nature of such outdoor experiences is, in Bourdieu's terms (Citation1990; Citation1998), the ‘feel for the game’, a metaphor he used to articulate how the body binds together his constructs of habitus, capital and field (see Bourdieu Citation1984; Citation1990; Citation1993). For Chinese immigrants, participating in recreation in New Zealand's coastal blue spaces is a ‘new game’ with ‘new rules’. We identified that these mainland Chinese immigrants’ early life urban-based experiences, social restrictions, and traditional values formed their homeland habitus which included concerns about safety in the water. Additionally, the forms of capital they valued differ from those in Aotearoa's dominant cultural field. For example, bodily dispositions such as Chinese cultural values of light complexion impact these migrants’ willingness to develop blue-space cultural capital. However, Asian migration to Aotearoa includes diverse individuals from the Asian continent. Most participants in this study were from mainland Chinese, so did not represent the broader spectrum of the ‘Chinese’ ethnic category in Aotearoa, including the experiences and perspectives of those from Taiwan, Hong Kong, and other regions and countries.

Our findings show that a crucial type of capital to understand and enable one to ‘play the game’ is cultural capital. Lacking important forms of cultural capital in the Aotearoa field produced interrelated influences on Chinese immigrants, making them unable to afford, uninterested in, or unprepared for coastal blue space activities. However, of the three forms of cultural capital required for blue space recreation, which we term blue space capital, the embodied cultural capital was the hardest to accumulate (see also Bhugra, Watson, and Ventriglio Citation2021). However, migrants are not a homogenous group and the valuing of different types of capital is also impacted by their ethnic minority and migrant status, length of time in Aotearoa, economic status, gender and age. These intersecting factors also influence Chinese immigrants’ decisions about the importance of accumulating different types of capital. For example, many articulated that blue space-related cultural capital is less important than capital associated with educational credentials.

As Bourdieusian theory emphasizes, capital, habitus and field are interlocking (Yang Citation2014). Exploring these migrants’ homeland habitus and lack of blue space capitals helped us contextualize and understand the constraints to outdoor recreation that prior studies have identified, and the contexts in which leisure ‘choices’ are made. However, as we identified when there is a hysteresis, or mismatch between an individual's habitus and the social and cultural field, there is a potential for individuals to modify their behaviour (e.g. parents’ new practices), beliefs and attitudes to fit in with the prevailing norms and expectations of the field (Burawoy and Holdt Citation2018). This may lead to new opportunities, new ways of thinking, and better adaptation to the field. Yet, facing the mismatch between their habitus and the field of blue spaces, these participants also chose to reject, or challenge the norms and expectations of the new field (e.g. valuing Chinese cultural values of light complexion).

Implications for policy and practice

While understandings of how to improve wellbeing of immigrants, and enhance community cohesion often focus on economic factors such as employment and lifestyle assimilation (e.g. language), habitus and capital are useful conceptual tools to better address Chinese immigrants’ disengagement or exclusion at local blue spaces. Our findings suggest that recognition is needed of the different ways in which ‘natural’ places are understood by communities, particularly the ongoing ways in which coastal blue spaces can be seen as sites of danger and fear (see also Evers Citation2019; Olive and Wheaton Citation2021; Wheaton, Citation2014). Research participants clearly articulated a desire to engage in blue space activities, but that they felt unconfident to try water sports without the support of ‘experts’, especially Chinese women. Inadequate water skills not only increase the risk of drowning, but may also make people more risk averse (Moran and Wilcox Citation2013). Organized water education and activity programmes such as those provided by the organizations we spoke with, have played a key role in providing sustainable and safe blue space engagements for these Chinese communities, and in helping them acquire blue space capital. However, as has also been shown in the provision of water safety for indigenous communities in Aotearoa and beyond (e.g. Giles, Castleden, and Baker Citation2010; Phillips Citation2020; Rich and Giles Citation2014), these activities need to be culturally relevant, and community specific. This research sheds light on the need for more geographically widespread and available water safety and outdoor recreation engagement programmes. There is also a clear need for further research that includes more diverse individuals from the Asian continent, and from the Indian sub-continent. Following the tragic drowning of two Indian migrants earlier this year (2023), community representatives – again – called for the urgent need for more accessible water safety education for all migrants (Church Citation2023).

Conclusions

International research on blue and green public recreation spaces recognizes that while these spaces can provide important therapeutic and social benefits, they can also be sites of fear, cultural contestation and social exclusion (Neal et al. Citation2015; Olive and Wheaton Citation2021), particularly for minority ethnic communities (Burdsey Citation2016; Phoenix, Bell, and Hollenbeck Citation2021; Wheaton Citation2013; Wheaton et al. Citation2020). Leisure scholarship to date has paid little attention to outdoor recreation in Aotearoa's fast-growing Asian migrant communities. Our research has contributed to this gap providing a better understanding of the factors that enable and constrain Chinese immigrants’ outdoor blue space recreation practices. In doing so our research also contributes to the growing literature on the changing geographies of cultural differences in Aotearoa, particularly due to the complex impacts of global and local migrations, and shifts in minority ethnic and majority communities (Spoonley Citation2015). As Lovelock et al. (Citation2011) also show, ‘nature-based’ outdoor recreation is central to understanding people's sense of attachment and belonging to places, people, and communities in Aotearoa, with important implications for the understanding of ‘us’ in times of rapidly changing demography. While our study focused on just one new-migrant community, our findings have importance for how we can develop understandings of Aotearoa's blue and green spaces that better recognize the diversity of social/cultural views and relationships to nature, and the ontologies and worldviews of all our communities, particularly Māori and Pacifika. There is a clear need for scholarship on the outdoors to continue to problematize existing narratives that presume a single, usually white male European experience of outdoor spaces, rather than recognising the ‘multiple’ and often ‘contested histories written into the diverse cultural experiences with the outdoors’, particularly in Settler Colonial contexts (Ho and Wang Citation2016, 7).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Aotearoa is the indigenous Māori name for New Zealand. We use this in the article to recognise te reo Māori as an official language, and the significance of understanding names and the ways they reflects our history, and place in the world. The Chinese terms for New Zealand is "新西兰" (Xīn Xī Lán) or "紐西蘭" (Niŭ Xī Lán).

2 This Active NZ survey was conducted 2013/4 focused on adults (16 years and over) engaging in sport and recreation. https://sportnz.org.nz/resources/active-new-zealand-survey-2013-14/

3 All photographs used in this article are with participants’ permission.

4 We note however that some fully clothed Asian women may also be following religious practices.

References

- Auckland Council Research and Evaluation Unit. 2020. Asian People in Auckland: 2018 Census Result. https://knowledgeauckland.org.nz/media/1443/asian-people-2018-census-info-sheet.pdf.

- Bandeira, M. M., B. Wheaton, and S. C. Amaral. 2023. “The Development of Pioneer National Policy on Adventure Recreation in Brazil and Aotearoa/New Zealand’s First Review.” Leisure Studies 42 (3): 352–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2022.2125555.

- Barrett, T. 2018. “Bourdieu, Hysteresis, and Shame: Spinal Cord Injury and the Gendered Habitus.” Men and Masculinities 21 (1): 35–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/1097184X16652658

- Beames, S., C. Mackie, and M. Atencio. 2019. Adventure and Society. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bell, S. L., J. Hollenbeck, R. Lovell, M. White, and M. H. Depledge. 2019. “The Shadows of Risk and Inequality Within Salutogenic Coastal Waters.” In Hydrophilia Unbounded: Blue Space, Health and Place, edited by R. Foley, R. Kearns, T. Kistemann, and B. W. Wheeler, 153–166. London: Routledge.

- Bell, S. L., C. Phoenix, R. Lovell, and B. W. Wheeler. 2015. “Seeking Everyday Wellbeing: The Coast as A Therapeutic Landscape.” Social Science & Medicine 142: 56–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.08.011

- Bhugra, D., C. Watson, and A. Ventriglio. 2021. “Migration, Cultural Capital and Acculturation.” International Review of Psychiatry 33 (1-2): 126–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540261.2020.1733786

- Bourdieu, P. 1977. Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. 1978. “Sport and Social Class.” Social Science Information 17 (6): 819–840. https://doi.org/10.1177/053901847801700603

- Bourdieu, P. 1984. Distinction: A Social Critique of The Judgment of Taste. Cambridge: Routledge.

- Bourdieu, P. 1986. “The Forms of Capital.” In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, edited by John G. Richardson, 241–253. New York, NY: Greenwood Press.

- Bourdieu, P. 1990. The Logic of Practice. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. 1993. The Field of Cultural Production. Cambridge: Polity.

- Bourdieu, P. 1998. Practical Reason: on the Theory of Action. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Bourdieu, P. 1999. “The State, Economics and Sport.” In France and the 1998 World Cup: The National Impact of A World Sporting Event, edited by H. Dauncey, and G. Hare, 15–21. London: Frank Cass.

- Bourdieu, P., and L. Wacquant. 1992. An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Braun, V., V. Clarke, N. Hayfield, and G. Terry. 2019. “Thematic Analysis.” In Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences, edited by P. Liamputtong, 843–860. Singapore: Springer.

- Brown, D. 2006. “Pierre Bourdieu’s ‘Masculine Domination’ Thesis and The Gendered Body In Sport and Physical Culture.” Sociology of Sport Journal 23 (2): 162–188. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.23.2.162

- Bruce, T., and B. Wheaton. 2009. “Rethinking Global Sports Migration and Forms of Transnational, Cosmopolitan and Diasporic Belonging: A Case Study of International Yachtsman Sir Peter Blake.” Social Identities 15 (5): 585–608. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504630903205258

- Burawoy, M., and K. Holdt. 2018. Conversations with Bourdieu: The Johannesburg Moment. Johannesburg: Wits University Press.

- Burdsey, D. 2004. “‘One of the Lads’? Dual Ethnicity and Assimilated Ethnicities in the Careers of British Asian Professional Footballers.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 27 (5): 757–779. https://doi.org/10.1080/0141987042000246336

- Burdsey, D. 2016. Race, Place and the Seaside: Postcards from the Edge. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Cao, W., and M. H. Wong. 2007. “Current Status of Coastal Zone Issues and Management In China: A Review.” Environment International 33 (7): 985–992. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2007.04.009

- Chinese in Other Countries. 2022. “Huang Weixiong, the Cantonese (part 2) [Video].” YouTube. August 2. https://www.youtube.com/watch?app = desktop&v = EVKiup6Llis&feature = share.

- Chong, G. P. L. 2013. “Chinese Bodies That Matter: The Search for Masculinity and Femininity.” The International Journal of the History of Sport 30 (3): 242–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2012.754428

- Church, L. 2023. “Renewed Calls for Better Water Safety Education for Migrants.” 1News. January 23. https://www.1news.co.nz/2023/01/23/renewed-calls-for-better-water-safety-education-for-migrants/.

- Cosgriff, M. 2023. “Tuning in: Using Photo-Talk Approaches to Explore Young People’s Everyday Relations with Local Beaches.” Sport, Education and Society 28 (6): 629–640. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2023.2170345.

- Cosgrove, A., and T. Bruce. 2005. “‘The Way New Zealanders Would Like To See Themselves’: Reading White Masculinity Via Media Coverage Of The Death Of Sir Peter Blake.” Sociology of Sport Journal 22 (3): 336–355. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.22.3.336

- de Lange, W. 2006. “Coastal Erosion - People, Houses, and Managing Erosion”, Te Ara - The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/coastal-erosion/page-3.

- Department of Conservation. 2020. New Zealanders in the Outdoors: Domestic Customer Segmentation Research. https://www.doc.govt.nz/globalassets/documents/about-doc/role/visitor-research/new-zealanders-in-the-outdoors.pdf.

- Dixson, B. J., A. F. Dixson, B. Li, and M. J. Anderson. 2007. “Studies of Human Physique and Sexual Attractiveness: Sexual Preferences of Men and Women in China.” American Journal of Human Biology 19 (1): 88–95. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.20584

- Drowning Prevention Auckland. 2021. Preventable Drowning by Ethnicity 2016-2020. https://www.dpanz.org.nz/research/statistics/.

- Durie, M. H. 1998. Te Mana, Te Kāwanatanga: The Politics of Self Determination. Auckland: Oxford University Press.

- Eames, C. 2018. “Education and learning: Developing action competence: living sustainably with the sea.” In Living with the Sea, 70–83. Routledge.

- Elliott, L. R., M. P. White, J. Grellier, S. E. Rees, R. D. Waters, and L. E. Fleming. 2018. “Recreational Visits to Marine and Coastal Environments In England: Where, What, Who, Why, and When?” Marine Policy 97: 305–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2018.03.013

- Erickson, B., C. W. Johnson, and B. D. Kivel. 2009. “Rocky Mountain National Park: History and Culture as Factors in African-American Park Visitation.” Journal of Leisure Research 41 (4): 529–545. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2009.11950189

- Espiner, N., E. J. Stewart, S. Espiner, and G. Degarege. 2021. Exploring the Impacts of the Covid-19 National Lockdown on Outdoor Recreationists’ Activity and Perceptions of Tourism. https://researcharchive.lincoln.ac.nz/handle/10182/13786.

- Evers, C. W. 2019. “Polluted Leisure.” Leisure Sciences 41 (5): 423–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2019.1627963

- Eyles, O. S. S., and C. R. Ergler. 2020. “Former Refugees’ Therapeutic Landscapes In Dunedin, New Zealand.” Sites: A Journal of Social Anthropology and Cultural Studies 17 (1): 40–65.

- Finney, C. 2014. Black Faces, White Spaces: Reimagining The Relationship of African Americans To The Great Outdoors. Chapel Hill: UNC Press.

- Foley, R. 2015. “Swimming in Ireland: Immersions in Therapeutic Blue Space.” Health & Place 35: 218–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.09.015

- Foley, R., R. Kearns, T. Kistemann, and B. Wheeler. 2019. Blue Space, Health and Wellbeing: Hydrophilia Unbounded. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Foong, Y. K. 2021. “Case Study Four: Whakahonoa Ki Te Whenua: Connecting New New Zealanders To Te Reo Māori and the Outdoors.” In Tūtira Mai: Making Change In Aotearoa New Zealand, edited by D. Belgrave, and G. Dodson, 270–272. Auckland: Massey University Press.

- Friesen, W. 2019. “Quantifying and Qualifying Inequality Among Migrants.” In Intersections of Inequality, Migration and Diversification, edited by R. Simon-Kumar, F. L. Collins, and W. Friesen, 17–42. Cham: Springer.

- Gilchrist, P., and B. Wheaton. 2017. “The Social Benefits of Informal and Lifestyle Sports: A Research Agenda.” International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics 9 (1): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2017.1293132

- Giles, A. R., H. Castleden, and A. C. Baker. 2010. “‘We Listen to Our Elders. You Live Longer That Way’: Examining Aquatic Risk Communication and Water Safety Practices in Canada’s North.” Health & Place 16 (1): 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.05.007

- Glass, M. R., and D. J. Hayward. 2001. “Innovation and Interdependencies in the New Zealand Custom Boat-Building Industry.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 25 (3): 571–592. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.00330

- Guo, W., X. R. Chen, and H. C. Liu. 2022. “Decision-making Under Uncertainty: How Easterners and Westerners Think Differently.” Behavioral Sciences 12 (4): 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12040092

- Harper, A. B. 2009. “‘When Black Men Go into the Forest They Don’t Come Back Out’: Employing Critical Race and Whiteness Studies in Understanding Ecological Identity Development for Environmental Education Outreach.” https://theavarnagroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Why-dont-black-people-go-camping.pdf.

- Haycock, D., and A. Smith. 2014. “A Family Affair? Exploring The Influence of Childhood Sport Socialisation on Young Adults’ Leisure-Sport Careers In North-West England.” Leisure Studies 33 (3): 285–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2012.715181

- Hayward, J. 2023. ‘Biculturalism’, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/biculturalism/print.

- Ho, Y. C. J, and Chang D. 2022. “To whom does this place belong? Whiteness and diversity in outdoor recreation and education.” Annals of Leisure Research 25 (5): 569–582. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2020.1859389

- Ho, A.-H., and Y. Wang. 2016. “A Chinese Model Of Education In New Zealand.” In Chinese Education Models in A Global Age, edited by C. P. Chou, and J. Spangler, 193–206. Singapore: Springer.

- Hoskins, T. K., and A. Jones. 2017. “Non-human others and Kaupapa Māori research.” In Critical Conversations in Kaupapa Māori, edited by T. K. Hoskins, and A. Jones, 48–59. Wellington, New Zealand: Huia.

- Johnston, L. 2005. “Transformative Tans? Gendered and Raced Bodies on Beaches.” New Zealand Geographer 61 (2): 110–116. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-7939.2005.00022.x

- Kawharu, M. 2000. “Kaitiakitanga: A Maori Anthropological Perspective of the Maori Socio-Environmental Ethic of Resource Management.” The Journal of the Polynesian Society 109 (4): 349–370.

- Kay, T. E. 2009. Fathering Through Sport and Leisure. London: Routledge.

- Kay, J., and S. Laberge. 2002. “Mapping the Field of “AR”: Adventure Racing and Bourdieu’s Concept of Field.” Sociology of Sport Journal 19 (1): 25–46. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.19.1.25

- Kelly, P., and T. Lusis. 2006. “Migration and the Transnational Habitus: Evidence from Canada and the Philippines.” Environment and Planning A 38 (5): 831–847. https://doi.org/10.1068/a37214

- Laberge, S., and J. Kay. 2002. “Pierre Bourdieu’s Sociocultural Theory and Sport Practice.” In Theory, Sport and Society, edited by J. Maguire, and K. Young, 239–266. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science/JAI Press.

- Laurendeau, J. 2020. ““The Stories That Will Make a Difference Aren’t the Easy Ones”: Outdoor Recreation, the Wilderness Ideal, and Complicating Settler Mobility.” Sociology of Sport Journal 37 (2): 85–95. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.2019-0128

- Lee, J., and M. Zhou. 2015. The Asian American Achievement Paradox. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Liu, L. 2021. “Paddling Through Bluespaces: Understanding Waka Ama as a Post-Sport Through Indigenous Māori Perspectives.” Journal of Sport & Social Issues 45 (2): 138–160. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723520928596

- Liu, T., and M. Li. 2020. “Leisure & Travel as Class Signifier: Distinction Practices of China’s New Rich.” Tourism Management Perspectives 33: 100627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2019.100627

- Lovelock, K., B. Lovelock, C. Jellum, and A. Thompson. 2011. “In Search of Belonging: Immigrant Experiences of Outdoor Nature-Based Settings In New Zealand.” Leisure Studies 30 (4): 513–529. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2011.623241

- Lovelock, B., K. Lovelock, C. Jellum, and A. Thompson. 2012. “Immigrants’ Experiences of Nature-Based Recreation in New Zealand.” Annals of Leisure Research 15 (3): 204–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2012.716618

- Ministry for the Environment and Stats NZ. 2022. Environment Aotearoa 2022: New Zealand’s Environmental Reporting Series. https://environment.govt.nz/publications/environment-aotearoa-2022/waita-ocean-and-marine-conditions/.

- Moran, K., and S. Wilcox. 2013. “Water Safety Practices and Perceptions of ‘New’ New Zealanders.” International Journal of Aquatic Research and Education 7 (2): 136–146. https://doi.org/10.25035/ijare.07.02.05

- Neal, S., K. Bennett, H. Jones, A. Cochrane, and G. Mohan. 2015. “Multiculture and Public Parks: Researching Super-Diversity and Attachment in Public Green Space.” Population, Space and Place 21 (5): 463–475. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.1910

- Nemani, M. J., and H. Thorpe. 2016. “The Experiences of ‘Brown’ Female Bodyboarders: Negotiating Multiple Axes of Marginality.” In Women in Action Sport Cultures: Identity, Politics and Experience, edited by H. Thorpe, and R. Olive, 213–233. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- New Zealand Surf Life Saving. 2020. National Beach & Coastal Safety Report. https://www.dpanz.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/slsnz-beach-coastal-safety-report-2020_single-pages-for-digital-use_low-res-1.pdf.

- Nutsford, D., A. L. Pearson, S. Kingham, and F. Reitsma. 2016. “Residential Exposure To Visible Blue Space (But Not Green Space) Associated With Lower Psychological Distress in A Capital City.” Health & Place 39: 70–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.03.002

- Olive, R., and B. Wheaton. 2021. “Understanding Blue Spaces: Sport, Bodies, Wellbeing, and the Sea.” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 45 (1): 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723520950549

- O’Shea, S. 2015. “Avoiding the Manufacture of ‘Sameness’: First-In-Family Students, Cultural Capital and the Higher Education Environment.” Higher Education 72 (1): 59–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9938-y

- Pearson, A. L., R. Bottomley, T. Chambers, L. Thornton, J. Stanley, M. Smith, and L. Signal. 2017. “Measuring Blue Space Visibility and ‘Blue Recreation’ in the Everyday Lives of Children in A Capital City.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 14 (6): 563. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14060563

- Phillips, C. 2020. “Wai Puna: An Indigenous Model of Māori Water Safety and Health in Aotearoa, New Zealand.” International Journal of Aquatic Research and Education 12 (3), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.25035/ijare.12.03.07

- Phillips, C., and N. Mita. 2016. “Māori and the Natural World.” Out and About 32 (Autumn): 12–18.

- Phoenix, C., S. L. Bell, and J. Hollenbeck. 2021. “Segregation and the Sea: Toward A Critical Understanding of Race and Coastal Blue Space In Greater Miami.” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 45 (2): 115–137. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723520950536

- Puwar, N. 2004. Space Invaders: Race, Gender and Bodies Out of Place. Oxford: Berg.

- Recreation Aotearoa. 2018. Outdoor Recreation in a Superdiverse New Zealand. https://issuu.com/newzealandrecreationassociation/docs/nzra_insights_report_1_diversity_in.

- Rich, K. A., and A. R. Giles. 2014. “Examining Whiteness and Eurocanadian Discourses in the Canadian Red Cross’ Swim Program.” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 38 (5): 465–485. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723514533199

- Ridgway, A. 2022. “‘To Call My Own’: Migrant Women, Nature-Based Leisure and Emotional Release After Divorce in Hong Kong.” Leisure Studies, https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2022.2148717.

- Roberts, R., N. Carpenter, and P. Klinac. 2020. Predicting Auckland’s exposure to coastal instability and erosion : Technical Report 2020/021. https://www.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/environment/what-we-do-to-help-environment/Documents/predicting-auckland-exposure-coastal-instability-erosion.pdf

- Shilling, C. 1991. “Educating the Body: Physical Capital and the Production of Social Inequalities.” Sociology 25 (4): 653–672. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038591025004006

- Shores, K., D. Scott, and M. Floyd. 2007. “Constraints To Outdoor Recreation: A Multiple Hierarchy Stratification Perspective.” Leisure Sciences 29 (3): 227–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400701257948

- Singh, A. 2022. “Kickboxing with Bourdieu: Heterodoxy, Hysteresis and the Disruption of ‘Race Thinking’.” Ethnography, https://doi.org/10.1177/14661381211072431.