ABSTRACT

Committed volunteers are the driving force of successful community-based conservation initiatives. However, many groups struggle with recruitment and retention of volunteers. This research adds to the limited knowledge on what motivates community-based conservation volunteers to become committed to a conservation initiative, by carrying out a case study on community-based conservation volunteers in the Manawatū region of New Zealand. Twenty-one semi-structured interviews with key members of community-conservation groups were carried out along with a survey distributed to all local community-based conservation groups. This research showed that the key long-term motivation factors are ‘to care for the environment’, ‘to help the local community’, ‘to be outside, or amongst nature’ and to have ‘a connection to nature’. There was minimal change between long-term and initial motivation factors, with only three motivation factors increasing in importance; ‘to socialise with others’, ‘for stress relief or escape’ and ‘to help the local community', and one decreasing in importance; ‘to learn new skills and knowledge’. In order to enhance commitment of volunteers there is a need to take motivation factors into account within project design and management, allow time for socialisation, and provide ongoing training, education and recognition.

Introduction

Community-based conservation (CBC) involves the participation of the community in a range of natural resource management practices that aim to have a positive impact on the environment (Berkes Citation2004; Ruiz-Mallen et al. Citation2015). CBC encompasses participation in a wide range of conservation initiatives from small, local, self-managed initiatives such as tree planting and pest control to co-management of protected areas and national parks (Dudley et al. Citation2009; Ruiz-Mallén et al. Citation2014; Ruiz-Mallen et al. Citation2015). To achieve successful CBC it is essential to have satisfied, committed volunteers; therefore, it is important to understand volunteer motivations, how they evolve and change over time and how to promote volunteer commitment.

People are motivated to volunteer for CBC for a variety of reasons. Understanding what motivates individuals to volunteer can help support community-based conservation groups (CBCGs), NGOs and government agencies in their efforts to maintain volunteer numbers and achieve conservation goals. Early research into volunteer motivations by Clary et al. (Citation1998) identified six key motivation factors that influence people’s decision to volunteer: ‘values’, the opportunity for individuals to express their ‘altruistic and humanitarian concerns for others’; ‘understanding’, the opportunity to learn new things, use knowledge, or practice skills; ‘social’, the opportunity to connect with others; ‘career’, the possibility for career-related benefits; ‘protective’, in order to reduce guilt over being more fortunate than others; and ‘enhancement’ the chance for personal growth and development. Research by Ryan et al. (Citation2001) and Bruyere and Rappe (Citation2007) identified that in addition to these motivations, environmental volunteers are specifically motivated by ‘a desire to help the environment’. Another important factor which motivates some environmental volunteers is ‘a connection to nature’. Previous studies have shown that individuals with past experiences in nature or an attachment to a green space are not only more likely to volunteer but are more likely to become committed volunteers (Gooch Citation2003; Laverie and McDonald Citation2007; Pagès et al. Citation2018; Schild Citation2018). New Zealand research, including the Survey of New Zealanders (Ipsos Citation2016) and The Public Perceptions of New Zealand’s Environment Survey (Hughey et al. Citation2016) also suggests that the key factors motivating environmental volunteers in New Zealand are ‘to protect and enhance the environment’ and ‘to look after my local area’.

This research addresses four key questions: (1) What motivates CBC volunteers to be committed to a group or project? (2) Do CBC volunteer motivations change over time? (3) Does a personal connection to nature or an attachment to a place enhance commitment? and (4) What can be done to maintain and promote commitment in CBC volunteering? These questions are explored through a case study on CBC volunteers in the Manawatū region of New Zealand. Twenty-one semi-structured interviews with key members of CBCGs were carried out and a questionnaire distributed to all the CBCGs in the Manawatū to gain insight into the experiences and perspectives of both group leaders and participants. This research contributes to the limited literature on the value and importance of committed long term volunteers for the success of conservation goals. In particular, this research seeks to fill a gap in the literature by interviewing and surveying local volunteers in the Manawatū region of New Zealand, a region with a significant need for conservation initiatives and the restoration of natural habitats.

The importance of volunteers in community-based conservation

The number of volunteers participating in CBC is increasing worldwide (Ryan et al. Citation2001; Dudley et al. Citation2009; Bramston et al. Citation2011; Shirk et al. Citation2012; Ruiz-Mallén et al. Citation2014; Ruiz-Mallen et al. Citation2015; Frensley et al. Citation2017; Larson et al. Citation2020). Committed CBC volunteers are essential for many environmental organisations, and pivotal to addressing a number of ecological issues (Bramston et al. Citation2011; Hvenegaard and Perkins Citation2019). The success of environmental initiatives to protect and restore natural environments is becoming increasingly dependent on CBC volunteers, and many would not exist without them (Bramston et al. Citation2011; Hvenegaard and Perkins Citation2019).

For example, a major current environmental initiative in New Zealand is Predator Free 2050. It is based on an ambitious goal set by the New Zealand government in 2016 to make New Zealand free from introduced predators by 2050, in order to protect native wildlife. The success and momentum of CBCGs in island eradications and mainland predator control inspired Predator Free 2050 and achieving this goal will require unprecedented collaboration between iwi, landowners, government, NGOs and local community groups. Volunteers are of upmost importance if this goal is to become a reality, and therefore the ability to attract and retain committed volunteers is key to its success (Department of Conservation Citation2020, Citation2021), and to achieving future conservation goals. However, ‘the conservation sector has been grossly under resourced for decades by successive government and regional agencies’ (Bowen Citation2024), and there has been a decrease in environmental volunteers from 2013 - 2018 (Stats Citation2018).

In this context, some question whether it is appropriate for the Predator Free 2050 programme to be so heavily reliant on volunteers. Some argue that the programme is extremely expensive and unlikely to be successful because it does not adequately take into account other key drivers of biodiversity loss and species extinction such as habitat fragmentation and habitat loss . While others highlight that its success is completely dependent on the active participation of the public, which will be a challenge especially for people with limited time and opportunity to participate in conservation initiatives (SMC Citation2020).

The Department of Conservation (DOC) is aware of this challenge and the importance of public and Māori input and leadership (Department of Conservation Citation2020). DOC acknowledges the importance of community involvement, and that the success of Predator Free 2050 is dependent on contributions from a diverse range of New Zealanders, and a strong social movement. DOC has set up a trust with the intention of connecting all the people involved and engaging people in their vision of a Predator Free New Zealand. DOC is also supporting CBCGs to carry out predator control in ways that work for them, inspiring volunteers to build on the social movement, and encouraging Māori and local communities to take leadership roles (Department of Conservation Citation2020, Citation2021). The Public Perceptions of New Zealand Environment Survey in 2019 reported an increase in predator control in people’s backyards, volunteer work involving predator control and support for increased predator control (Hughey et al. Citation2019). This suggests that Predator Free 2050 is having some success on engaging the wider public in predator control. While there is a range of opinions on the success of Predator Free 2050, it widely agreed that getting the public onboard and actively participating is key to its success.

Understanding volunteer motivations is critical for effective volunteer recruitment, retention, and commitment (Geoghegan et al. Citation2016; Larson et al. Citation2020). Environmental organisations often have issues with high volunteer turnover and unreliability, leading to a waste of limited resources in recruiting and training new volunteers (Bushway et al. Citation2011; Asah and Blahna Citation2013; Higgins and Shackleton Citation2015; Ding and Schuett Citation2020; Larson et al. Citation2020). Previous studies have found that CBC and environmental volunteers have a range of different motivations which have been shown to be derived from a person’s values, the desire for increased understanding and knowledge, social connections, career advancement, self-esteem and personal development (Ryan et al. Citation2001; Asah and Blahna Citation2013; Newton et al. Citation2014; Frensley et al. Citation2017; Hvenegaard and Perkins Citation2019; Larson et al. Citation2020). ‘Helping the environment’ is often found to be the top motivation factor in environmental volunteering (Ryan et al. Citation2001; Bruyere and Rappe Citation2007; Akin et al. Citation2013; Alender Citation2016; Pagès et al. Citation2018; Gratzer and Brodschneider Citation2021; Thomas et al. Citation2021; Heimann and Medvecky Citation2022). The literature outlines a series of reasons for this motivation factor including a concern for the environment, a desire to help address specific environmental issues and wanting to restore or improve a local greenspace (Bruyere and Rappe Citation2007; Akin et al. Citation2013; Alender Citation2016; Dunkley Citation2019; Thomas et al. Citation2021). ‘Helping the local community’ is another key motivation factor that is driven by two aspects; people that want to protect and enhance local areas that they use and to help others in the local community by enhancing a local area (Bruyere and Rappe Citation2007; Ohmer et al. Citation2009; Asah and Blahna Citation2013; Alender Citation2016; Turnbull et al. Citation2020). Having a connection to nature can also motivate people to volunteer for environmental causes and has been found to contribute to a volunteer’s desire to help the environment, leading to increased participation and longevity in environmental volunteering (Guiney and Oberhauser Citation2009; Pagès et al. Citation2018; Hvenegaard and Perkins Citation2019; Ganzevoort and van den Born Citation2020). When volunteers’ motivations match the benefits they receive from volunteering they are more likely to be satisfied and participate long-term. Offering volunteers the opportunity to participate in a variety of tasks that match with common motivations, along with substantial acknowledgement of volunteer contributions is thought to increase volunteer retention and commitment (Clary et al. Citation1998; Ryan et al. Citation2001; Bonney et al. Citation2009; O'Brien et al. Citation2010; Newton et al. Citation2014; Frensley et al. Citation2017).

Motivations of environmental and CBC volunteers vary between participants and often evolve and change over time (Ryan et al. Citation2001; Bonney et al. Citation2009; Frensley et al. Citation2017; Larson et al. Citation2020). ‘Helping the environment’ and ‘social factors’ are often identified as key initial motivations (Pagès et al. Citation2018; Schild Citation2018).Whereas, ‘personal experiences’, and ‘being part of a community’, along with being part of a ‘well organised project’ are identified as key motivations for long-term committed volunteers (Asah and Blahna Citation2013; Frensley et al. Citation2017; Pagès et al. Citation2018; Schild Citation2018). A change in motivations over time can often relate to a change from a passive role to a more active role or leadership position (Bramston et al. Citation2011; Frensley et al. Citation2017). Therefore, it is important to provide participants with a variety of tasks which take level of commitment into account and provide participants opportunities to try new things, develop skills and become more involved in project management (Bonney et al. Citation2009; Asah and Blahna Citation2013; Geoghegan et al. Citation2016; Frensley et al. Citation2017; Larson et al. Citation2020).

Research suggests that volunteer satisfaction and commitment are associated with the ability of an organisation or project leader to be able to fulfil their volunteers’ motivations, and provide relevant tasks that increase volunteer engagement (Ryan et al. Citation2001; Domroese and Johnson Citation2017; Frensley et al. Citation2017; Takase et al. Citation2019; Ding and Schuett Citation2020; Larson et al. Citation2020). Past studies have highlighted a range of other factors that may have a positive impact on volunteer satisfaction, consequently improving volunteer commitment. Some of the key factors mentioned are effective project management (Hvenegaard and Perkins Citation2019; Ding and Schuett Citation2020; Gulliver et al. Citation2022), ongoing education and training (Frensley et al. Citation2017; Hvenegaard and Perkins Citation2019; Gulliver et al. Citation2022), opportunities for social activities (Laverie and McDonald Citation2007; Pagès et al. Citation2018; Schild Citation2018; Hvenegaard and Perkins Citation2019; Ding and Schuett Citation2020), providing volunteers with positive feedback (Hvenegaard and Perkins Citation2019; Gulliver et al. Citation2022), showing volunteers how their work has helped the environment (Ryan et al. Citation2001), and an attachment to an organisation or place (Laverie and McDonald Citation2007; Pagès et al. Citation2018; Schild Citation2018).

Methods

This paper examines the longevity and commitment of CBC volunteers in the Manawatū region of New Zealand. A mixed-methods approach was used including a desktop study of local CBCGs, semi-structured interviews with key CBCG representatives and a structured online questionnaire of CBC volunteers.

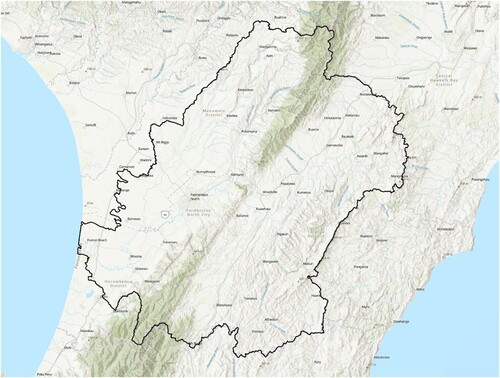

The Manawatū region is situated in the lower half of the North Island of New Zealand (as illustrated in ), with the main population centre of Palmerston North. The region encompasses the Manawatū river catchment, and includes a series of mountain ranges notably the Tararua and Ruahine ranges, along with the tree studded Manawatū plains that run between the ranges and the sea. The region is known for its strong agricultural sector and contains areas of ecological significance, including the internationally recognised RAMSAR estuary site at Foxton Beach (National Wetland Trust of New Zealand Citation2023).

Desktop study

A preliminary online investigation was carried out to identify all current CBCGs in the Manawatū region. The Environment Network Manawatū (ENM)Footnote1, Forest and BirdFootnote2 and the Department of Conservation websites were used to find all local CBCGs. Each of these websites had lists of CBCGs which were individually investigated to find all the CBCGs that were based in the Manawatū and have conservation based objectives. Twenty-one CBCGs were identified and Appendix 1 provides a brief summary of each CBCG. These CBCGs carry out a range of tasks including weeding, predator control, native plantings, growing native plants, habitat restoration, education, advocacy, and litter collection.

Semi-structured interviews

Semi-structured interviews were used to gain a thorough understanding of the local CBCGs and their volunteers. Initial interviews were also used to get a sense of key issues in order to develop the questionnaire. Each of the CBCGs found in the desktop study and ENM, Forest and Bird and DOC were contacted multiple times and invited to participate in a semi-structured interview; of these, 19 CBCG representatives from 12 CBCGs participated, along with a representative from ENM and DOC. A total of 21 interviews were conducted between November 2020 and April 2023, including multiple representatives from some CBCGs.

The interviews were approximately 45 min and consisted of a series of open-ended questions; 9 questions for CBCG volunteers, with an additional 3 questions for CBCG leaders and other representatives (as outlined in Appendix 2). The questions related to their CBCG and volunteers, along with questions about volunteer motivations, recruitment and the retention of volunteers. Interviews were recorded, transcribed and analysed for key themes.

Questionnaire

An online questionnaire was also carried out consisting of 43 short answer and multi-choice questions, which covered volunteering details, demographics of volunteers, motivations for volunteering, commitment and satisfaction, barriers to volunteering, environmental monitoring and attitudes towards pro-environmental behaviours. There was also an open ended question at the end for participants to share any other thoughts or experiences.

Targeted and snowball approaches to sampling were used to recruit volunteers to complete the questionnaire (Sarantakos Citation2013; Denscombe Citation2014). Volunteers participating in CBC within the Manawatū region were reached via an email sent from ENM to all its active members; an advertisement was also placed in their October newsletter in 2021 and the 21 CBCGs that were identified in the desktop study were also sent the same email to their listed contact email on the same day. Initial recruitment emails were sent on October 29th 2021; reminder emails were sent on January 28th 2022 and the questionnaire was closed on February 24th 2022. Recipients of the email received a link to the questionnaire with an invitation to send it on to all their volunteers. The questionnaire invitation included a short summary of the study, a link to the online questionnaire, and an option to have a paper version delivered to them if required. The online questionnaire was created and administered using QualtricsTM (qualtrics.com); and the paper version was available via email request or collection from ENM’s office in Palmerston North.

The questionnaire had 101 respondents, representing 17 of the 21 CBCGs identified in the desktop study, additionally there were responses from ENM, DOC and 4 small CBCGs that were not identified in the desktop study.

Results

The need for committed volunteers

Many interviewees argued that there was a need for more volunteers, particularly more committed volunteers. Several CBCG leaders explained that their group had enough volunteers on paper but needed more volunteers that participate regularly and are able to complete tasks with little or no instruction:

There’s always a need for more volunteers, committed volunteers. (CBCG leader)

There’s a need for people who are going to put the time in and can help quite a bit with the momentum rather than just hands to plant plants. (CBCG key representative)

There’s also a need for volunteers because it’s about splitting up the jobs, so there’s actually less pressure on people and you can do more of something. But you have to find the right people. (CBCG board member)

It’s very easy to get plenty of people out to plant plants, it’s extremely hard to get the same number of people out to free them up for the next four years amongst the blackberry and tall grass. (CBGC key representative)

There are not enough people wanting to lead. (CBCG leader)

Succession is a big issue with volunteer groups for sure. The energy of one or two people is critical. (CBCG trustee)

Demographics of CBC volunteers

Volunteers who responded to the survey tended to be older, highly educated and either retired or in less than full time employment. There were slightly more females than males with 53% female, 46% male, and 1% identifying as non-binary. There was also a wide age range among the volunteers, with a high proportion of older individuals; 14% of respondents were aged under 29, 7% aged between 30-39, 9% aged between 40-49, 16% aged between 50-59, 24% from 60–69 years and 30% aged 70 and over. The volunteers also tended to have a high level of education with 14% completing secondary school and 85% of volunteers having some form of tertiary education, including 16% having a PhD. The largest group of respondents were retired (47%), followed by those in paid employment for less than 30 h per week (21%) and those in paid employment for 30 h or more per week (18.6%). There was also a small proportion of students (9%) and those who were unemployed (4%).

Frequency and commitment of volunteers

Survey respondents had volunteered in CBC activities from a few months to over 40 years, with the highest proportion of respondents having volunteered between 1 and 5 years (41.9%), and the smallest proportion for 16–20 years (5.4%). There was also a range of volunteering frequency with the highest proportion of respondents volunteering more than once a week (34.6%), followed by monthly (20.5%), weekly (18.0%), fortnightly (10.2%) and a few times a year (9.0%), with a small proportion stating they were unsure (7.7%).

Only 18.6% of respondents stated that the types of activities offered by their CBCG influence how frequently they volunteer. Activities identified by these respondents included to be more hands on with animals, having new experiences, being able to educate younger volunteers and caring for wildlife.

A high proportion (61%) of respondents stated that volunteering was enjoyable (4) or very enjoyable (5), with no respondents stating it as not enjoyable (1), when enjoyment was ranked from 1 not enjoyable to 5 very enjoyable.

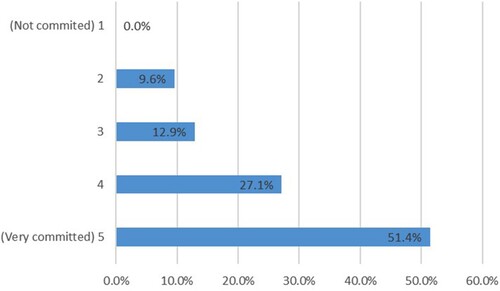

Just over half of the respondents stated that they were very committed to their CBCG, and no respondents stated that they were not committed (as illustrated in ).

Figure 2. The proportion of volunteers’ commitment level when ranked from 1 (not committed) to 5 (very committed) (N = 70).

There is a clear relationship between perceived enjoyment and commitment, with respondents that reported a high level of enjoyment also tending to report a high level of commitment (as illustrated in ).

Table 1. The relationship between perceived commitment and perceived enjoyment of respondents (N = 70).

Long-term motivation factors

Initial motivations are the factors that originally encouraged people to start volunteering, whereas long-term motivations are factors that contributed to volunteers' continued volunteering and increased frequency in volunteering. shows how volunteers ranked the importance of long-term motivation factors, which are then compared to initial motivations in .

Table 2. Mean motivation factors for long-term volunteering, ranked from 1 (not important) to 5 (very important).

Table 3. Comparison of motivation factors that encourage participation in community-based conservation initially and in the long-term.

The four long-term motivations that were identified as the most important by respondents were ‘to care for the environment’ (m = 4.59), ‘to help the local community’ (m = 4.19), ‘as a connection to nature’ (m = 3.96) and ‘to be outside, or amongst nature’ (m = 3.96), which all connect to the broad themes of environment and community. Interviewees reinforced the finding that volunteer motivation is often underpinned by a desire to make a meaningful contribution:

For me it’s about feeling purposeful. I don’t want to fill in time I want to do something that matters. (CBCG key representative)

It’s absolutely critical that people go away saying good I achieved something. I think [volunteers] find satisfaction in learning and feeling that they have really done something worthwhile. (CBCG leader)

When initial motivation factors are compared to long-term motivation factors (see ), the top four motivation factors remain the same and there are a few differences between long-term and initial motivation factors in general. ‘To learn new skills, or knowledge’ is the only motivational factor that decreased from initial to long-term motivations. There are also a few factors that increased substantially including ‘to help the local community’, ‘to socialize with others’ and ‘for stress relief or escape’.

There were also positive relationships between perceived commitment level and specific motivation factors including; ‘as a connection to nature’, ‘to be outside amongst nature’ and ‘to care for the environment’ as illustrated in . The higher the importance of these motivational factors, the higher the level of commitment.

Table 4. The relationship between commitment level and three long term motivation factors (N = 70).

Volunteer connection

A connection to nature or a place was often identified by interviewees as a reason why volunteers were interested in CBC volunteering:

It’s helping the community get a connection back with the waterway … it’s about [volunteers] having a better connection with the waterway, and seeing them as a living thing that does have fish and value rather than somewhere to just dump your rubbish. (CBC programme coordinator)

It’s the tangible stuff that tugs on the strings a bit I think. (CBCG leader)

You appreciate a place for what it is and it’s not good to see it being wrecked … we have a connection to Foxton beach. (CBCG trustee)

Locally a lot of people spent quite a bit of time up in the Ruahines and TararuasFootnote3, it’s a big push for a lot of people they really want to protect those, because they feel connected. Connection is a big one … connection to the place, special species, taongaFootnote4species, quite often people want to get involved with stuff like that. To do with the bush, the birds. (DOC representative)

There are people who like to be connected, who like being out and about with a small group or just getting a sense of belonging. (CBCG leader)

Retaining committed volunteers

CBCG leaders that were interviewed shared several strategies they used to encourage volunteers to continue to participate. In particular, they explained that it was important to offer volunteers a range of different tasks to reflect different peoples’ interests and abilities:

I try to give people choices so that if they’re uncomfortable about doing something, there’s another thing that they could do. (CBCG leader)

We are constantly looking at what volunteers can be doing because obviously the skill base and that sort of thing is amazing with volunteers. You have people that have more skills than any of us (employees) at doing everything you can imagine. (CBCG employee).

Table 5. Percentage of volunteer perceived connection to CBCG, place where they volunteer, and nature in general while volunteering.

We find ENM just crucial, and if you are connected to them you will be fine. We are just tiny leaves fluttering in the breeze if it wasn’t for the network. They bring us all together. (CBCG trustee)

It’s not just a couple of people being busy bodies in a corner, there’s actually a whole linkage. There’s people interacting with the council. It’s linked so although I’m only doing a little bit, I know I’m part of a bigger picture. (CBCG key representative)

It’s great because you feel part of something bigger. (CBCG leader)

Discussion

Key characteristics of community-based conversation volunteers

CBC volunteers in the Manawatū are typically older, retired and have a higher level of education than the general population. These trends have also been found in other studies about CBC and environmental volunteering, such as research by Chase and Levine (Citation2018) and Heimann and Medvecky (Citation2022). Interviews with key CBCG representatives revealed that most CBCGs have a core group of approximately 6 volunteers, who are very committed and turn up to regular working bees, events and meetings. They also have another cohort of volunteers who are less regular and turn up more spontaneously, often consisting of 20–50 individuals. Our results found that 34.6% of respondents were volunteering more than once a week and 18.0% were volunteering once a week, with 51.4% of volunteers perceiving themselves to be ‘very committed’ suggesting that a large proportion of respondents were from the core groups of CBC volunteers.Footnote5

Another interesting finding was that out of the volunteers that perceived themselves as ‘very committed’ over 60% were over 60 years old, and only 8.4% were under 29 years old. These findings align with a study by Madsen et al (Citation2021) in which older volunteers were more likely to commit to volunteering than younger volunteers. Retired people are a great source of committed volunteers, typically due to having spare time and wanting to be involved in something with purpose (Pillemer et al. Citation2017). CBC volunteering is also beneficial to older people as it can have a positive impact on physical and mental health (Pillemer et al. Citation2017; Ding and Schuett Citation2020; Chen et al. Citation2022). However, CBCGs reliance on older volunteers also gives rise to several challenges. For example, older volunteers are more prone to health and mobility issues that can limit volunteering opportunities, or mean that they need to transition to less physical roles. Studies have shown that poor mobility and poor health, as a result of getting older were stated by volunteers as barriers to environmental volunteering (Pope Citation2005; Hvenegaard and Perkins Citation2019). There is also evidence that increased turnover rates and burnout of volunteers is more common among older volunteers (Hvenegaard and Perkins Citation2019). Given the disproportionate number of older volunteers, it is important that CBCGs are flexible around volunteer commitment levels and volunteering hours, and offer a range of tasks that vary in physical ability (Bramston et al. Citation2011; Frensley et al. Citation2017; Pagès et al. Citation2018; Schild Citation2018; Larson et al. Citation2020).

Factors motivating community-based conservation volunteers

Some motivational factors appear more important for CBC volunteers in the Manawatū, particularly ‘helping the environment’, ‘helping the local community’, ‘to be outside, amongst nature’ and ‘as a connection to nature’. Other factors such as ‘to get exercise’ and ‘to advance my career’ were less important. Our study also found some differences between initial and long term motivation factors of respondents, with long term volunteers identifying ‘to socialise with others’, ‘for stress relief or escape’ and ‘to help the local community’ as more important in the long term than initially.

With a constant need for more volunteers, understanding volunteer motivations is an important aspect of volunteer recruitment and retention. Several leaders of local CBCGs within the Manawatū emphasised that there is a need for more volunteers, particularly committed volunteers. It was clear in interviews that although there is always a need for volunteers CBCG leaders wanted to appeal to a smaller number of people who would become regular long term volunteers, rather than having lots of people that would show up once or twice. There was also an emphasis on a need for volunteers that would do a range of tasks that are less desirable such as weeding and ongoing maintenance, not just plantings or hands-on work with native wildlife, which is more typical of committed volunteers.

Our survey results also illustrated that volunteers’ enjoyment and commitment were linked, with higher enjoyment leading to higher commitment. This is in line with a few studies that found that volunteers who have their motivations fulfilled are more likely to feel satisfied, leading to a higher probability of continued participation and commitment (Domroese and Johnson Citation2017; Takase et al. Citation2019; Ding and Schuett Citation2020). Therefore, in order to increase the satisfaction and commitment of volunteers it would be worthwhile to design projects that provide a variety of activities which align with key motivational factors, and incorporate a range of motivation factors throughout the project (New Citation2010; Simakole et al. Citation2019). For example, the ‘to socialise’ motivational factor could be easily added into a project design by giving people the option to work in small groups and allowing time for socialising after a working bee or event. The ‘to help the environment’ motivational factor could be incorporated by setting clear environmental goals, providing environmental education opportunities for volunteers and highlighting and celebrating progress at the end of a working bee or event. Another way to increase volunteer satisfaction is to provide volunteers with positive feedback and recognition (Hvenegaard and Perkins Citation2019; Gulliver et al. Citation2022), so they feel as though the work they have done is worthwhile and valuable. ‘Doing something worthwhile’ was an important aspect of volunteering among CBCG volunteers in the Manawatū. When it comes to CBC it is beneficial to focus on concepts the community can identify with personally (New Citation2010), and for people to not only see their progress but understand the importance behind what they are doing, so they can feel satisfied and purposeful. In turn this leads to an increase in environmental awareness and a desire to continue to contribute to conservation outcomes.

Some authors argue that there is a difference in motivational factors between initial and long-term volunteers, and that projects should offer a range of opportunities for different commitment levels (Hvenegaard and Perkins Citation2019; McAteer et al. Citation2021). Studies show that people are often motivated to start volunteering because of a desire to help the environment and a need to socialise with others (Pagès et al. Citation2018; Schild Citation2018). Whereas, long-term volunteers are often found to be motivated by feeling like a part of a community, personal experiences, attachment to a group or place, to be part of a well-run project and also to socialise with others (Asah and Blahna Citation2013; Frensley et al. Citation2017; Pagès et al. Citation2018; Schild Citation2018). Some of the CBCG representatives interviewed were successful in offering a range of tasks, that encouraged the use of different skills and abilities, within their group of volunteers. Offering a range of tasks for volunteers is important to encourage continued participation, whether it is to offer a range of tasks that appeal to different skills, abilities or motivation factors, or to allow committed volunteers to take on a more leadership-based role. However, within our group of CBCGs a prevalent issue was succession of leaders. There tended to be a few key volunteers who keep the momentum going but a lack of people to replace or come alongside them. In order for CBCGs to be successful long-term and avoid the burn-out of key volunteers it is important the committed volunteers are encouraged to take leadership or management roles. Other studies have found that it is important that volunteers are given the opportunity for ongoing education and training, and are recognised for their efforts in order to build confidence which can lead to a desire to take on a leadership or management role (Frensley et al. Citation2017; Hvenegaard and Perkins Citation2019; Gulliver et al. Citation2022). Few CBCGs in the Manawatū offer educational opportunities, with little mention of education or training of volunteers in interviews and on the questionnaire.

Our survey found some differences between initial and long-term motivations of CBC volunteers, but the relative importance of motivation factors between initial and long-term did not really change. However, the results indicate that volunteers increasingly value socialisation, stress relief/escape and the idea of helping the local community, and value the ability to learn new skills and knowledge less. The opportunity for socialisation between volunteers has been found to be a key aspect in successful volunteer-based projects (Laverie and McDonald Citation2007; Pagès et al. Citation2018; Schild Citation2018; Hvenegaard and Perkins Citation2019; Ding and Schuett Citation2020). However, ‘to socialise with others’ wasn’t identified as very important as an initial motivation factor in our study, so it therefore makes sense that as volunteers get to know each other the social aspect of volunteering becomes more important, as opposed to ‘to help the environment’ which was already ranked relatively high and so unlikely to increase substantially. An increase in the desire ‘to help the local community’ is also expected as volunteering in a local area has been found to promote relationships between locals, help develop self-efficacy (Ohmer et al. Citation2009), and contribute to an attachment to place. This makes it more likely that volunteers would continue to restore or enhance a local area. There is a wealth of literature on the health benefits of volunteering, particularly CBC and environmental volunteering. Consequently, volunteers may have found that after volunteering for some time that they are benefiting from the mental health benefits, including stress relief. The decrease in importance of learning new skills and knowledge could be due to the fact that there is minimal training and education available for CBC volunteers in the Manawatū region, and therefore they may just be doing the same tasks each time they volunteer. However, it may be that once volunteers reach a certain level of skill and experience there isn’t much more to learn within a given group, and hence the importance of this aspect diminishes over time, relative to other aspects.

Attracting and retaining committed volunteers

As mentioned above, Predator Free 2050 is a national programme that is dependent on the collaborative effort of iwi, CBCGs, councils, NGOs and government stakeholders, with a considerable reliance on volunteers across the country. To be successful it requires committed volunteers on the ground regularly laying, checking and maintaining traps, alongside the collection of significant amounts of data (Department of Conservation Citation2020, Citation2021). Motivational factors play an important role in having committed volunteers, therefore a better understanding of what drives volunteers is likely to lead to improved success rates and environmental outcomes. However, the volunteer workforce in the conservation area is limited and there is a definite need for more committed volunteers already, without the additional pressure of Predator Free 2050. This raises the question of whether or not Predator Free 2050 is a realistic goal especially with the strong reliance on volunteers and the community, instead of being fully funded by the government. In order for New Zealand to be able to achieve such an ambitious conservation goal, the government needs to dramatically increase support and funding to CBCGs that are implementing the practical measures needed to achieve Predator Free 2050s objectives. However, the recent change in government suggests this is unlikely to happen (Environmental Defence Society, Citation2024) and the success of Predator Free 2050 will remain highly dependent on committed volunteers.

There have been limited studies on volunteer motivations in New Zealand, and none that have investigated the Manawatū region. The Manawatū is a region that has experienced significant loss in biodiversity and clearing of original habitats. Therefore, this region is in dire need of habitat rehabilitation and support of its limited remnant habitats. This study gives us a clearer understanding of what drives local CBCGs to help protect and enhance local areas, address local conservation issues, and be involved in national conservation efforts. The results from this study also add to other studies both in New Zealand and overseas to allow us to see general trends in what motivates CBC volunteers, and how to build a volunteer force that is committed to achieving both local, national and international conservation goals.

Successful volunteer-based projects have been found to account for volunteer motivations and socialisation; they tend to be focused, long-term and provide volunteers with training, support and recognition (Bruyere and Rappe Citation2007; Van Den et al. Citation2009; Newton et al. Citation2014; Gulliver et al. Citation2022). These factors are often mentioned in the literature and are thought to positively impact volunteer satisfaction, and therefore commitment (Newton et al. Citation2014; Frensley et al. Citation2017; Hvenegaard and Perkins Citation2019; Ding and Schuett Citation2020; Gulliver et al. Citation2022). The interviews with CBC volunteers revealed that most of the CBCGs have a social aspect to them and allow time for volunteers to get to know each other; there was an awareness of key factors that motivate people, but more could be done to incorporate motivations in project designs. The success and focus of long-term projects tended to be very dependent on a few key individuals, but overall, there was a recognition of the worth of volunteers. The key concept that is regularly mentioned in the literature to improve volunteer commitment, but is limited in Manawatū CBCGs, is ongoing training and education, which may contribute to the difficulties with the succession of leaders within the groups. Many of the CBCGs in the Manawatū are small and have minimal funding therefore in order to achieve effective training and education would require a government organisation, such as DOC, or a larger umbrella group to step up to fund and run targeted training courses.

The importance of volunteer connection

Many CBC volunteers have a desire to see and be in nature, along with a concern for the environment (Gooch Citation2003; Krasny et al. Citation2014). There is a significant body of literature on connecting people with the environment, and the impact this connection has on environmental values and actions, including its impact on CBC volunteering (Laverie and McDonald Citation2007; Nisbet et al. Citation2009; Pagès et al. Citation2018; Schild Citation2018). Schild (Citation2018) found that volunteers experienced an improved connection to nature and to the place where they were volunteering; this is consistent with the findings of Gooch (Citation2003) and Ryan (Citation2005). Furthermore, a study by Pagès et al. (Citation2018) found that attachments to place and wildlife are often closely linked to the motivation factors of environmental volunteers. This aligns with our study in which volunteers who perceived themselves to be highly connected to place tended to find the following motivation factors of high importance: ‘to care for the environment’, ‘to be outside, or amongst nature’ and ‘to help the local community’. Several studies argue that an attachment to place, and connection to nature can also act as independent motivation factors (Gooch Citation2003; Schild Citation2018).

Several interviewees of CBCG’s in the Manawatū identified forms of connection as key motivation factors and therefore the connection to a place is a great way of recruiting volunteers and getting them involved in local conservation efforts. CBC volunteers’ connection to a place often drove their desire to participate, as they wanted to protect or restore a place that is close to their heart, in their local community. Building a connection between the community and local green spaces, or targeting people who already have a connection to these spaces, could be an effective way of attracting committed volunteers. Another way to promote a connection which was mentioned by Forgie et al. (Citation2001) is to promote the uniqueness of New Zealand’s biodiversity so people develop a deep commitment to the environment. In the interviews with leaders of CBCGs it was mentioned that some of the most committed volunteers tend to be the ones that live nearby the volunteering sites and use them regularly for recreation or relaxation. So encouraging people to use green spaces in a respectful way could promote a connection to conservation sites, and thereby increase the number of people who care for the site and in turn increase people willing to volunteer in order to protect or restore the site.

Interviewees often mentioned the concept of connecting with other CBCGs or working together to achieve conservation outcomes. This was especially important to the smaller groups, as it made them feel like they were a part of something bigger and worthwhile. The Environment Network Manawatū (ENM) was often mentioned as a vital mechanism to bring groups together. Most of the interviewees representing CBCGs that are associated with the ENM expressed that they felt well supported and connected by the network. However, some believed there was still a need for further cooperation between CBCGs. From discussions with CBCG leaders it is clear that for the most part ENM does an exemplary job of supporting CBCGs and bringing them together on large over-arching projects, in a way that allows the CBCGs to decide what they want to come together to achieve. However, not all CBCGs are going to be interested in every combined project, and the specific goals of individual CBCGs may not align with the current combined project but future projects may be more aligned to a different selection of CBCGs.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study contributes to our understanding of long-term motivations of individuals involved in CBC and environmental volunteering. This study investigated CBC volunteers in Manawatū, New Zealand, a region that is in need of significant habitat restoration and protection, by interviewing and surveying the people who are actively making a difference. In-person interviews often at conservation sites allowed for a deep understanding of why they were volunteering and what support was needed for them to continue to make an impact. Volunteers play a key role in environmental projects, and therefore it is important to be able to not only recruit but retain volunteers, particularly committed volunteers. If environmental projects are to have positive long-term effects on the environment, a continuous effort is crucial. Thus, it is important that volunteer motivations are taken into account initially and throughout projects, so that volunteers are satisfied and engaged. Ideally there should also be a range of tasks for volunteers that cater for different motivational factors, including tasks that lead into leadership roles. Volunteers also need to have time to socialise with others, feel appreciated and have access to targeted, ongoing education and training.

‘To help the environment’ was identified as the top motivation factor by CBC volunteers in the Manawatū. So, it would be beneficial to actively incorporate this motivation factor into local CBC projects. This can be achieved by having clear, transparent environmental goals, providing opportunities for volunteers to engage in relevant environmental education, acknowledging and celebrating progress toward achieving goals and clearly communicating the next steps to move forward. Building a connection to nature and/or an attachment to place through volunteer experiences can also be an effective way to attract and retain committed volunteers. Local residents and users of local green spaces may already have a connection to the place and therefore make a great target pool for volunteers. Helping individuals build a connection by highlighting the uniqueness and beauty of local areas and emphasising the important role of CBC in protecting them can also help attract and retain committed volunteers.

With the government increasingly relying on volunteers to help achieve biodiversity goals and drive national conservation initiatives, such as Predator Free 2050, it is critical that there is more research around motivation factors that promote committed CBC volunteers. This study takes a local, on-the-ground approach to gain an understanding of local CBCGs and what drives their volunteers. Similar studies in other regions would help verify our findings and identify the key motivation factors that drive CBC throughout New Zealand. Further research is also needed to continue to examine the role motivation factors play in the commitment of CBC volunteers, and how to increase not only volunteers but committed volunteers. It is essential that CBCGs are effective and able to contribute to local, and/or national conservation goals. As such, further investigation into community-based environmental monitoring and the motivation factors that encourage volunteers to be involved in data collection would help to find ways to increase community-based environmental monitoring and allow CBCGs to track the progress and effectiveness of local conservation projects.

Acknowledgements

We are extremely grateful to Environment Network Manawatu for helping to distribute our questionnaire, and to all the individuals who participated in our study.

Author contributions

The primary author is Charlotte Sextus who collected and analysed the data, and wrote the manuscript. Karen Hytten and Paul Perry are co-authors who supervised the research and contributed to writing and revising the manuscript.

Ethical statement

This research was undertaken in accordance with Massey University's Code of Ethical Conduct for Research, Teaching and Evalutations Involving Human Participants.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The Environment Network Manawatū is a network of member groups that supports and encourages environmental initiatives in the Manawatū, in areas ranging from sustainable living to wildlife conservation.

2 Forest and Bird is the leading conservation NGO in New Zealand.

3 Two mountain ranges which form the Eastern boundary of the Manawatū region.

4 Taonga is a is a Māori word that refers to a treasured possession, or highly prized object.

5 Although our questionnaire was distributed to as many CBCG volunteers in the Manawatū as possible, due to the voluntary nature of participation it is likely that more committed volunteers were more likely to complete the questionnaire.

References

- Akin H, Shaw B, Stepenuck KF, Goers E. (2013). Factors associated with ongoing commitment to a volunteer stream-monitoring program. Journal of Extension. 51(3):25. doi:10.34068/joe.51.03.25.

- Alender B. 2016. Understanding volunteer motivations to participate in citizen science projects: a deeper look at water quality monitoring. Journal of Science Communication. 15(3):A04. doi:10.22323/2.15030204.

- Asah ST, Blahna D. 2013. Practical implications of understanding the influence of motivations on commitment to voluntary urban conservation stewardship. Conservation Biology. 27(4):866–875. doi:10.1111/cobi.12058.

- Berkes F. 2004. Rethinking community-based conservation. Conservation Biology. 18(3):621–630. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2004.00077.x.

- Bonney R, Cooper CB, Dickinson JL, Kelling S, Phillips T, Rosenberg KV, Shirk J. 2009. Citizen science: a developing tool for expanding science knowledge and scientific literacy. BioScience. 59(11):977–984. doi:10.1525/bio.2009.59.11.9.

- Bowen D. 2024. Sector burnout in conservation volunteering? [accessed March 2024].https://www.volunteeringnz.org.nz/views/conservation-volunteering-sector-burnout/.

- Bramston P, Pretty G, Zammit C. (2011). Assessing environmental stewardship motivation. Environment and Behavior. 43(6), 776–788.

- Bruyere B, Rappe S. 2007. Identifying the motivations of environmental volunteers. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management. 50(4):503–516. doi:10.1080/09640560701402034.

- Bushway L, Dickinson J, Stedman R, Wagenet L, Weinstein D. 2011. Benefits, motivations, and barriers related to environmental volunteerism for older adults: developing a research agenda. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 72(3):189–206. doi:10.2190/AG.72.3.b.

- Chase SK, Levine A. 2018. Citizen science: exploring the potential of natural resource monitoring programs to influence environmental attitudes and behaviors. Conservation Letters. 11(2):e12382. doi:10.1111/conl.12382.

- Chen PW, Chen LK, Huang HK, & Loh CH. (2022). Productive aging by environmental volunteerism: a systematic review. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 98:104563 doi:10.1016/j.archger.2021.104563.

- Clary EG, Ridge RD, Stukas AA, Snyder M, Copeland J, Haugen J, Miene P. 1998. Understanding and assessing the motivations of volunteers: a functional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 74(6):1516–1530. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.74.6.1516.

- Denscombe M. 2014. The good research guide: for small-scale research projects. 5th ed. Maidenhead, England: Open University Press.

- Department of Conservation. 2020. He Māhere Rautaki Whakakore Konihi, Predator Free 2050, 5-year action plan: 2020 - 2025. Department of Conservation.

- Department of Conservation. 2021. Predator free 2050 5-year progress report. Wellington, New Zealand: Department of Conservation Te Papa Atawhai.

- Ding C, Schuett MA. 2020. Predicting the commitment of volunteers’ environmental stewardship: does generativity play a role? Sustainability. 12(17):6802. doi:10.3390/su12176802.

- Domroese MC, Johnson EA. 2017. Why watch bees? Motivations of citizen science volunteers in the great pollinator project. Biological Conservation. 208:40–47. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2016.08.020.

- Dudley N, Higgins-Zogib L, Mansourian S. 2009. The links between protected areas, faiths, and sacred natural sites. Conservation Biology. 23(3):568–577. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2009.01201.x.

- Dunkley RA. 2019. Monitoring ecological change in UK woodlands and rivers: an exploration of the relational geographies of citizen science. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. 44(1):16–31. doi:10.1111/tran.12258.

- Environmental Defence Society. 2024. The government’s war on nature goes nuclear. [accessed March 2024]. https://eds.org.nz/resources/documents/media-releases/2024/fast-track-bill/?from=featured.

- Forgie V, Horsley P, Johnston J. 2001. Facilitating community-based conservation initiatives. Wellington, NZ: Department of Conservation.

- Frensley T, Crall A, Stern M, Jordan R, Gray S, Prysby MD, Newman G, Hmelo-Silver C, Mellor D, Huang J. 2017. Bridging the benefits of online and community supported citizen science: a case study on motivation and retention with conservation-oriented volunteers. Citizen Science: Theory and Practice. 2(1):4–14. doi:10.5334/cstp.84.

- Ganzevoort W, van den Born RJG. 2020. Understanding citizens’ action for nature: the profile, motivations and experiences of Dutch nature volunteers. Journal for Nature Conservation. 55:125824. doi:10.1016/j.jnc.2020.125824.

- Geoghegan H, Dyke A, Pateman R, West S, Everett G. 2016. Understanding motivations for citizen science. Final report on behalf of UKEOF. University of Reading, Stockholm Environment Institute (University of York) and University of the West of England.

- Gooch M. 2003. A sense of place: eological identity as a driver for catchment volunteering.

- Gratzer K, Brodschneider R. 2021. How and why beekeepers participate in the INSIGNIA citizen science honey bee environmental monitoring project. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 28(28):37995–38006 doi:10.1007/s11356-021-13379-7.

- Guiney MS, Oberhauser KS. 2009. Conservation volunteers’ connection to nature. Ecopsychology. 1(4):187–197. doi:10.1089/eco.2009.0030.

- Gulliver RE, Fielding KS, Louis WR. 2022. An investigation of factors influencing environmental volunteering leadership and participation behaviors. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. 52(2):397–420. doi:10.1111/conl.12382.

- Heimann A, Medvecky F. (2022). Attitudes and motivations of New Zealand conservation volunteers. New Zealand Journal of Ecology. 46(1):1–13. doi:10.20417/nzjecol.46.18.

- Higgins O, Shackleton CM. 2015. The benefits from and barriers to participation in civic environmental organisations in South Africa. Biodiversity and Conservation. 24(8):2031–2046. doi:10.1007/s10531-015-0924-6.

- Hughey KF, Kerr GN, Cullen R. 2016. Public perceptions of New Zealand’s environment: 2016. Christchurch: EOS Ecology.

- Hughey KF, Kerr GN, Cullen R. 2019. Public perceptions of New Zealand’s environment: 2019. Christchurch: EOS Ecology.

- Hvenegaard GT, Perkins R. 2019. Motivations, commitment, and turnover of bluebird trail managers. Human Dimensions of Wildlife. 24(3):250–266. doi:10.1080/10871209.2019.1598521.

- Ipsos. 2016. Full report: survey of New Zealanders. report prepared for the department of conservation. Auckland: Ipsos.

- Krasny ME, Crestol SR, Tidball KG, Stedman RC. 2014. New York city's oyster gardeners: memories and meanings as motivations for volunteer environmental stewardship. Landscape and Urban Planning. 132:16–25. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2014.08.003.

- Larson LR, Cooper CB, Futch S, Singh D, Shipley NJ, Dale K, LeBaron GS. Takekawa JY. 2020. The diverse motivations of citizen scientists: does conservation emphasis grow as volunteer participation progresses? Biological Conservation. 242:108428. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108428.

- Laverie DA, McDonald RE. 2007. Volunteer dedication: understanding the role of identity importance on participation frequency. Journal of Macromarketing. 27(3):274–288. doi:10.1177/0276146707302837.

- Madsen SF, Ekelund F, Strange N, Schou JS. 2021. Motivations of volunteers in Danish grazing organizations. Sustainability. 13(15):8163.

- McAteer B, Flannery W, Murtagh B. 2021. Linking the motivations and outcomes of volunteers to understand participation in marine community science. Marine Policy. 124:104375.

- National Wetland Trust of New Zealand. Manawatu Estuary. https://www.wetlandtrust.org.nz/get-involved/ramsar-wetlands/manawatu-estuary/.

- New TR. 2010. Butterfly conservation in Australia: the importance of community participation. Journal of Insect Conservation. 14(3):305–311. doi:10.1007/s10841-009-9252-z.

- Newton C, Becker K, Bell S. 2014. Learning and development opportunities as a tool for the retention of volunteers: a motivational perspective. Human Resource Management Journal. 24(4):514–530. doi:10.1111/1748-8583.12040.

- Nisbet EK, Zelenski JM, Murphy SA. 2009. The nature relatedness scale. Environment and Behavior. 41(5):715–740. doi:10.1177/0013916508318748.

- O'Brien L, Townsend M, Ebden M. 2010. ‘Doing something positive’: volunteers’ experiences of the well-being benefits derived from practical conservation activities in nature. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations. 21(4):525–545. doi:10.1007/s11266-010-9149-1.

- Ohmer ML, Meadowcroft P, Freed K, Lewis E. 2009. Community gardening and community development: individual, social and community benefits of a community conservation program. Journal of Community Practice. 17(4):377–399. doi:10.1080/10705420903299961.

- Pagès M, Fischer A, van der Wal R. 2018. The dynamics of volunteer motivations for engaging in the management of invasive plants: insights from a mixed-methods study on Scottish seabird islands. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management. 61(5-6):904–923. doi:10.1080/09640568.2017.1329139.

- Pillemer K, Wells NM, Meador RH, Schultz L, Henderson CR, Jr., Cope MT, Meeks S. 2017. Engaging older adults in environmental volunteerism: the retirees in service to the environment program. Gerontologist. 57(2):367–375.

- Pope J. 2005. Volunteering in Victoria over 2004. Australian Journal on Volunteering. 10(2):29.

- Ruiz-Mallén I, Newing H, Porter-Bolland L, Pritchard DJ, García-Frapolli E, Méndez-López ME, Reyes-García V. 2014. Cognisance, participation and protected areas in the Yucatan Peninsula. Environmental Conservation. 41(3):265–275. doi:10.1017/S0376892913000507.

- Ruiz-Mallen I, Schunko C, Corbera E, Roes M, Reyes-Garcia, V. (2015). Meanings, drivers, and motivations for community-based conservation in Latin America. Ecology and Society. 20(3):33. doi:10.5751/ES-07733-200333.

- Ryan RL. 2005. Exploring the effects of environmental experience on attachment to urban natural areas. Environment and Behavior. 37(1):3–42. doi:10.1177/0013916504264147.

- Ryan Kaplan R, Grese RE. 2001. Predicting volunteer commitment in environmental stewardship programmes. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management. 44(5):629–648. doi:10.1080/09640560120079948.

- Sarantakos S. 2013. Social research. 4th ed. Basingstoke, England: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Schild R. 2018. Fostering environmental citizenship: the motivations and outcomes of civic recreation. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management. 61(5-6):924–949. doi:10.1080/09640568.2017.1350144.

- Shirk JL, Ballard HL, Wilderman CC, Phillips T, Wiggins A, Jordan R, McCallie E, Minarchek M, Lewenstein BV, Krasny ME, Bonney R. 2012. Public participation in scientific research: a framework for deliberate design. Ecology and Society. 17(2):04705–170229. doi:10.5751/ES-04705-170229.

- Simakole BM, Farrelly TA, Holland J. 2019. Provisions for community participation in heritage management: case of the Zambezi source national monument, Zambia. International Journal of Heritage Studies. 25(3):225–238. doi:10.1080/13527258.2018.1481135.

- SMC (Science Media Centre). 2020. Predator free 2050 strategy–expert reaction. https://www.sciencemediacentre.co.nz/2020/03/09/predator-free-2050-strategy-expert-reaction/.

- Stats NZ. 2018. Non-profit institutions satellite account. https://www.stats.govt.nz/reports/non-profit-institutions-satellite-account-2018.

- Takase Y, Hadi AA, Furuya K. 2019. The relationship between volunteer motivations and variation in frequency of participation in conservation activities. Environmental Management. 63(1):32–45. doi:10.1007/s00267-018-1106-6.

- Thomas JL, Cullen M, O'Leary D, Wilson C, Fitzsimons JA. 2021. Characteristics and preferences of volunteers in a large national bird conservation program in Australia. Ecological Management & Restoration. 22(1):100–105. doi:10.1111/emr.12442.

- Turnbull JW, Johnston EL, Kajlich L, Clark GF. 2020. Quantifying local coastal stewardship reveals motivations, models and engagement strategies. Biological Conservation. 249:108714. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108714.

- Van Den Berg HA, Dann SL, Dirkx JM. (2009). Motivations of adults for non-formal conservation education and volunteerism: implications for programming. Applied Environmental Education & Communication. 8(1), 6–17. doi:10.1080/15330150902847328.