ABSTRACT

While the 1990s saw the retreat of governments from economic governance to the benefit of the market and independent regulatory agencies, we now observe a comeback of governments’ interventions in the economy. This recent trend, which we call new interventionism, has so far hardly been addressed by public policy and regulatory governance scholars. This article identifies three major instruments serving new interventionism in previously liberalised sectors: re-nationalisation (vs. privatisation), regulatory expansion (vs. liberalisation) and regulatory governmentalisation (vs. delegation). Their relevance is confirmed by longitudinal analyses of electricity policies in three highly contrasted cases – the UK, Mexico and Morocco. This article also relates new interventionism to the re-politicisation of economic governance and discusses its implications. It contributes to the literature on the role of the state in the economy, on the politicisation of economic governance and on the transformation of the regulatory state.

Introduction

The end of the twentieth century was marked by the diffusion of neoliberal policies (Simmons, Dobbin, & Garrett, Citation2006), transforming governments’ engagement with the economy. Policies based on liberalisation, privatisation and market regulation have empowered private market players and technocratic actors such as independent regulatory agencies (IRAs) resulted in a considerable retreat of national executives. However, for the last 15 years, financial, sanitary and energy crises, policy learning, and transformed industrial, societal and political circumstances have raised question about the appropriateness of these neolibermal policy regimes (Wade, Citation2010). In parallel, policymakers’ have shown a rising appetite for governmental interventions in the economy (Gabor, Citation2021; Rodrik, Citation2008). Yet we still lack knowledge on the mechanisms, instruments and manifestations of what appears as a comeback of governmental interventionism in economic governance.

This article contributes to filling this gap by analysing the evolution of policy mixes in electricity policies since liberalisation reforms. Inspired by economists’ arguments about the comeback of industrial policy (Mazzucato & Rodrik, Citation2023), it highlights the adoption of increasingly interventionist policy instruments. It identifies three vehicles supporting this shift: re-nationalisation of electricity industrial actors, regulatory expansion applied to electricity industrial activities and governmentalisation of electricity regulation. Their increasing relevance is confirmed by three qualitative case studies in highly contrasted cases: the United Kingdom, Mexico and Morocco. Anchored into an incremental approach to policy change (Streeck and Thelen, Citation2005), the argument is embedded into a nuanced view of how this trend gradually – but surely – alters the overall degree of interventionism in electricity policy mixes.

These findings allow us to contribute to the literature on the evolving role of the state in the economy, to the debates on the politicisation of economic governance and to the nascent literature on the transformation of the regulatory state. This article presents, in turn, an overview of the literature on electricity governance, our new interventionist argument, our research methods, followed by the three case studies, the analysis of the data and a discussion on the implications in terms of regulatory repoliticisation. It concludes with the contributions to the literature.

The literature on electricity governance: which role for the executive?

Prior to liberalisation reforms, the electricity sector was governed by public monopolies, whereby sectoral decision-making power was very concentrated and close to the executive. Neoliberal electricity reforms have radically transformed this configuration. First, privatisation allowed the emergence of private industrial players in the sector that are now sharing the provision of electricity services with state owned enterprises (SOEs). Second, with liberalisation, a wide range of decisions over the conditions in which industrial players provide their services were delegated to the market, i.e., to industrial players themselves, instead of being regulated by the executive. Third, the re-regulation needed to sustain the development of electricity markets was entrusted to independent regulatory agencies (IRAs) that enjoy large decision-making autonomy from national executives. Worldwide, neoliberal policy reforms have empowered private actors and IRAs, resulting in massive power fragmentation and de-politicisation processes (Bolton, Citation2021; Victor & Heller, Citation2006) which have significantly reduced the influence of executives in sectoral governance.

The adoption of RE policies in the last 15 years – sometimes qualified as paradigm change in electricity policy (Kern, Smith, Shaw, Raven, & Verhes, Citation2014; Valenzuela & Rhys, Citation2022) comes with governance change. Yet the literature provides mixed accounts of the role of the executive in RE policies. On the one hand, RE policies come with new actors and stakeholders in the sector, such as renewable energy agencies, civil society, new private operators, and local energy communities, regional and local governments. Much of the scholarship thus emphasises the fragmented, polycentric and networked character of RE governance (Goldthau, Citation2014; Shih et al., Citation2016; Sovacool, Citation2011). On the other hand, a few authors have underlined that the paradigm change affecting electricity governance is accompanied by a comeback of the state in electricity governance (Goldthau, Citation2012; Reverdy & Breslau, Citation2019; Valenzuela & Rhys, Citation2022). Public subsidies, (re-)nationalisation of electricity companies, geopoliticisation of the energy sector: illustrations of a revival of states’ interventionism in electricity governance abound.

Polycentric governance versus state interventionism: both images seem to point in opposite directions regarding the role of executives in electricity governance. Our take on this question is that both images are not opposed, but different faces of the same coin. Executive reinforcement can take place in subtle ways and be embedded in a context of power dispersion, when it combines delegation with reinforced influence mechanisms over the agents (Wilks, Citation2005). When decision-making power partly shifts from private companies and IRAs to new actors that are closer to governments, the net outcome is more influence for the executive.

New interventionism and the re-politicisation of electricity governance

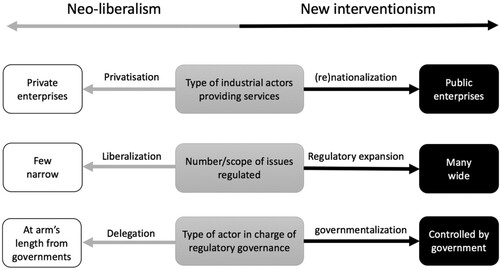

This article argues that the last generation of electricity policy reforms, generally aiming at promoting RE, features a comeback of governmental interventionism – after decades of worldwide reforms aiming at isolating electricity governance from the executives. We call this new interventionism.Footnote1 This new interventionism is underpinned by three instruments: re-nationalisation of industrial actors providing electricity services, regulatory expansion of electricity policy and governmentalisation of regulation. There are other mechanisms through which governments manifest their renewed interest for intervention, such as the increasing use of public subsidies. We focus on those three instruments because they are symmetrically opposed to the three major instruments of neoliberal reforms adopted in the 1980s and 1990s: privatisation, liberalisation and regulatory delegation. This choice allows us to place neo-liberalism and new interventionism at the opposite ends of a three-dimension continuum (see ) and facilitate the dialogue with the literature on liberalisation and regulatory reforms.

Empirically, policy mixes include both neoliberal and interventionist features. We assume that prior policy mixes – which can be more or less liberalised – are gradually expanded by the introduction of new RE policy instruments. This happens through a layering process which, without removing liberalisation policy instruments adopted earlier, can end up significantly transforming the general equilibrium of the policy mix over time (Streeck and Thelen Citation2005). Our point is that the direction adopted by policy reforms has changed, as if a pendulum oscillating between more and less interventionism has started to swing back after decades of reforms reducing interventionism. Re-nationalisation, regulatory expansion and regulatory governmentalisation are thus largely incremental processes. We argue that new policy instruments adopted in the electricity sector, even if not overwhelmingly interventionists, are increasingly interventionist, and that this process is incrementally altering the general degree of interventionism characterising electricity policy mixes.

The first instrument of executives’ comeback is the (re-)nationalisation of electricity industrial players. Whereas the re-nationalisation of energy companies used to be more common among oil producing countries such as Venezuela, Bolivia, Kazakhstan or Russia (Goldthau, Citation2014, p. 203), we recently saw similar moves in Europe with the announcement of the complete re-nationalisation of the French power utility EDF, the upcoming re-nationalisation of the UK System Operator and an emerging debate about the creation of a UK state-owned generation company (Davies, Citation2022). In countries which still have non-liberalised systems, debates on institutional reforms now de-emphasise or dismiss the need for privatisation, including in Mexico, China, or South Africa. After the privatisation trend that shifted part of the provision of electricity services from the public to the private sector, re-nationalisation alters the respective room for public versus private companies to the benefit of the former. This allows executives to recover influence in sectoral governance via an increasing engagement as industrial actors, i.e., as direct providers of electricity services.

The second instrument of the comeback of executives is the expansion of regulation applicable to electricity industrial services. Regulatory expansion refers to the shrinking of the autonomy enjoyed by industrial actors when making decisions when they operate via the electricity wholesale market, such as the choice of the technology they want to produce from (whether solar, gas, etc.) or the location of the power plants. This autonomy tends to be narrowed down with RE policies that place constraints on power generators in terms of price, volume, location or impact. For example, while the wholesale electricity market places all energy producers on equal footing, independently from the technology they rely on, RE policy instruments like feed-in-tariff often apply to specific technologies only (e.g., for photovoltaic solar only). Auctions for RE also frequently regulate the location of the future power plants or come with specific requirements on the socio-economic, industrial or ecologic impact of RE development. Regulatory expansion thus implies a shift of decision-making power from the private to the public – in the sense of regulatory – sphere. The regulatory expansion argument also reflects what seems to be a wider trend affecting other sectors, in particular with several examples of the rising importance of consumer protection (Koop & Lodge, Citation2020).

The third instrument supporting executives’ comeback is the governmentalisation of regulation. Regulatory governmentalisation refers to the fact that regulatory power is increasingly getting back to governments – another manifestation of the pendulum swinging back from the previous trend towards regulatory delegation. There are several forms of regulatory governmentalisation, the most visible of which being governments’ increasing attempts to reduce IRAs’ independence or recover competences previously delegated to them (Ozel, Citation2012; Rangoni & Thatcher, Citation2023). This article points at another type of regulatory governmentalisation, one that is anchored in the policy layering approach whereby the adoption of new policy instruments affects the overall equilibrium of sectoral governance. The decision to adopt new RE policy instruments is accompanied with a decision over its governance, i.e., about who will be in charge of its implementation. Contrary to wholesale markets that have generally been entrusted to IRAs, regulatory competences related to new RE policy instruments can also be delegated to ministries or non-independent public agencies. In this article, regulatory governmentalisation refers to the trend through which policymakers increasingly choose actors that are closer to governments for implementing new policy instruments. The aggregate effect on the electricity sector as a whole is the reduction of IRAs’ influence on electricity governance in relative terms, leading a relative shift of regulatory influence from IRAs to other actors more closely connected to the executive.

What we present as a comeback of interventionism is very closely related to what we could also call the re-politicisation of electricity governance. Politicisation is subject to many definitions, one of them being the rise in issue salience, actor expansion and opinion polarisation (De Wilde, Citation2011; Kriesi, Citation2016). Recent works on the politicisation of regulation, showing how regulation is increasingly subject to public scrutiny and contestation, is closely aligned with this definition (Koop & Lodge, Citation2020; Onoda, Citation2023). Another type of politicisation consists in the definition of an issue within the scope of government remit, whereby issues debated in the public sphere or being handled in de-politicised arenas are integrated in the formal political agenda, giving way to governmental deliberation and policy or institutional developments (Hay, Citation2007). The latter politicisation type is closely aligned with the literature on depoliticisation that emphasises the displacement of decision-making responsibility away from governments to less visible arenas and to the market, via delegation to IRAs, privatisation and liberalisation (Buller & Flinders, Citation2005; Burnham, Citation2001) (see ). From that perspective, the phenomenon that we investigate can also be seen as a type of repoliticisation.

Research design

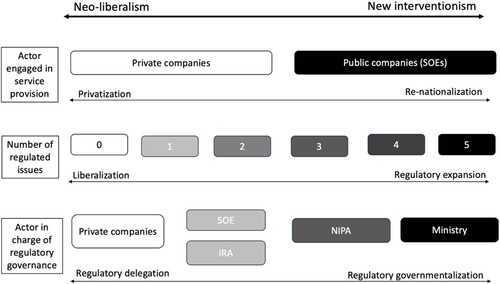

To evaluate whether there is a rise of interventionism over time we perform longitudinal analyses of electricity generation policies, by focusing on individual policy instruments as a unit of analysis. A single policy instrument can display different degrees of interventionism depending on how it is calibrated. For example, policymakers can decide to use auctions to regulate the socio-industrial impact of RE production (like in the UK) or not (like in Mexico). Hence, assessing the degree of interventionism of policy instruments requires going beyond distinguishing instrument types (e.g., regulatory vs redistributive) and requires including instruments’ calibration because much of the interventionism is designed at this level. We compare policy instruments over time across three dimensions: (1) the type of industrial actor mobilised by the implementation of the instrument (whether public or private) to assess (re-)nationalisation, (2) the number of issues that are regulated (whether few or many) to assess regulatory expansion and (3) the type of actor in charge of regulatory governance (whether disconnected from or controlled by the government) to assess regulatory governmentalisation (see for the conceptual framework and for the operationalisation of each of these dimensions). We assume that the policy layering process modifies the general balance of the policy mix incrementally (Streeck and Thelen Citation2005). So we consider that our claim will be validated if we find that policy instruments adopted recently tend to be more interventionist than policy instruments adopted at an earlier stage, in particular in the context of neoliberal reforms. In terms of timespan, we cover the period starting with the introduction of policy instruments coming with liberalisation reforms, which vary across cases, up to now. Since both liberalisation and RE policies have mainly focused on electricity generation, we limit our analysis to this segment of the sector, which also allows us to control for the subsector analysed.

To evaluate our argument on the comeback of executives in electricity governance, we selected three strikingly different countries: the UK, Mexico and Morocco, allowing for a strong external validity check. The three countries have important incentives to explore new RE sources, in particular wind and solar energy, given their high reliance on fossil fuel with limited potential for hydropower expansion. They display very different political regimes (accomplished democracy, illiberalism and autocracy) which are a relevant difference regarding their likelihood to employ interventionism. Yet we chose them mainly because they are very different regarding their pre-existing electricity policy regime, i.e., the extent to which they have engaged with privatisation and liberalisation reforms. Approaching the engagement with liberalisation reforms as continuums, we selected countries located on both ends of the continuums (Morocco and the UK) and one located somewhere in between (Mexico) (see ). This allows to assess the plausibility that the re-politicisation happens across political and policy regimes, rather than just within in particular segments of the continuums.

Table 1. Engagement of the three countries with privatisation and liberalisation reforms.

Liberalisation is relevant for the case selection in two respects. First, from a historical institutionalist approach we consider that the degree of prior liberalisation of the electricity sector reduces the likelihood of interventionism (path dependency). The UK is a least likely case and Morocco a most likely case for interventionism. As the second country to liberalise (only after Chile) UK deployment of liberalisation set it apart internationally, while Mexico adopted a wholesale market in 2014 only. Second, strongly liberalised countries like the UK have an important room for developing interventionism with RE policies, by contrast to countries that have largely maintained traditional interventionist structures. In the latter, liberalisation processes are still ongoing and overlap with the adoption of RE policies. This shall rather lead to less interventionism, unless an interventionist trend compensates the de-politicisation effects of liberalisation, leading to stability in the degree of interventionism. In other words, hardly liberalised countries like Morocco are both most likely cases for showing interventionism, and least likely cases for the development of further interventionism.

The operationalisation of re-nationalisation is based on the analysis of the type of industrial actor (private or public) supplying electricity (see ). This happens for example with partial or full re-nationalisation of a private power company that has previously been privatised or the creation of a new public company. If the incumbent company has been unbundled, re-nationalisation may apply, for example, to power generating companies (as in France), but also on other industrial actors, such as the system operator (as in the UK). Re-nationalisation is found if recent policy instruments rely, for their implementation, on both private actors and SOEs or SOEs only, by contrast to older instruments that would rely on private actors only.

To operationalise regulatory expansion, we count the number of issues being regulated (vs. left to the market) for each policy instrument (see ). Based on a systematic review of the literature specialised on RE auctions design (Hochberg & Poudineh, Citation2018; IRENA, Citation2019; Szabó, Bartek-Lesi, Dézsi, Diallo, & Mezősi, Citation2020; USAID, Citation2019) we pre-identified a list of six key issues that can either be liberalised, i.e., left to the discretion of industrial players, or regulated: technology (e.g., solar, on-shore wind, etc.), volume of electricity produced, price at which the electricity is sold, physical location of the new generation plants, identity of the off-taker that will buy the electricity, and local integration (social and industrial local development). We then empirically evaluate the extent of regulatory expansion by comparing the number of regulated issues in recent versus older policy instruments. Regulatory expansion is characterised when recent policy instruments regulate a higher number of issues than previous instruments.

The operationalisation of regulatory governmentalisation combines two criteria: (1) who are the leading actors engaged in making regulatory decisions and (2) how close to the executive they are, i.e. to what extent are they controlled by the government. We classified key actors of the electricity sector depending on the degree to which they are controlled by the executive (see ). Among industrial actors, public industries, that is state owned enterprises (SOE), are obviously closest to the executive than private industrial players. Among administrative actors we have: ministries (close to the executive), IRAs (far) and non-independent public agencies (NIPAs) that are detached from ministries though without enjoying independent decision-making competences (somewhere in between) – this is the case of most renewable energy agencies. Although SOEs are often seen as controlled by governments, we classify them as relatively autonomous (similar to IRAs) because in the electricity sector SOEs tend to be very powerful actors, difficult to effectively control by government, in spite of the latter’s important formal influence mechanisms, thanks to their competence, capability, and knowledge that governments lack (Victor & Heller, Citation2006). Regulatory governmentalisation is characterised when more recent policy instruments are implemented predominantly by actors closer to the governments than those in charge of implementing instruments adopted earlier.

The data was collected via a combination of document analysis (such as legislation, newspapers, market rules) and semi-structured interviews with national experts, policymakers (from national ministries, IRAs or public agencies) and policy stakeholders (electricity producers – both public and private, investors, international organisations, foreign aid offices, producers associations, independent experts).Footnote2 We did a total of 61 interviews between 2018 and 2022 (19 in the UK, 22 in Mexico and 20 in Morocco). As some interviewees are in sensitive political contexts, we took anonymity requirements very seriously, so we avoided relating content to specific interviewees that could be identified via a reference to their institution. The precise combination of data sources varied across countries as we adapted to the accessibility of data. For example, interviews are the source of nearly all the data presented in the Moroccan case due to the scarcity of official written sources.

United Kingdom

Between the 1950s and the 1980s, the UK government relied on a state-owned enterprise (SOE), the Central Electricity Generating Board, and a technical authority, the Electricity Council, to run the industry (non-independent agency). Margaret Thatcher launched reforms for industry restructuring (unbundling), privatisation and the introduction of competition via the creation of a wholesale electricity market (liberalisation). An IRA, first under the name of the Office of Electricity Regulation (Offer) and then the Office of Gas and Electricity Markets (Ofgem), took over responsibility for a light touch approach on the regulation of the industry, focused on the promotion of competition (Bolton, Citation2021). In 1992, having grown increasingly reliant and trustful on the IRA to regulate the sector, the government considerably reduced the importance of the Energy ministry, closed it and replaced it with a mere administrative unit within the Department of Trade and Industry (Newbery, Citation2005).

A full decade passed under fully liberalised industry before the first layer of renewable energy policy was introduced, consisting in a combination of quotas and Feed-in-tariff (FiT). Renewable energy quotas or ‘obligations’ were introduced in 2002 along with a target to achieve 10 per cent of renewable energy electricity by 2010 under the 2000 Utilities Act. Quotas were initially conceived in a way that kept regulatory interventions minimal, that is regulating RE volume only and leaving industrial actors’ autonomy for choosing technology and finding clients. Quota levels were regulated via negotiations between the IRA and companies. After the publication of the Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change in 2006, the government increased the realm of regulatory interventions into the quota system by setting obligations for specific technologies in 2010 and regulating prices (Gross & Heptonstall, Citation2010). In 2002 as well, the government adopted a Feed-in-Tariff (FiT) system for smaller scale projects, which implies stronger regulatory constraints regarding technology choices and price. Throughout this first phase of RE policies, the realm of issues subject to regulation, initially limited to RE volume, expanded to include prices and technology. By 2016, the quotas system was finally closed and the FiT capped after auctions proved to be a more effective mechanism to expand renewable energy.

In 2008, with the Climate Change Act, the government created a dedicated ministry integrating for the first time both energy and the decarbonisation agenda, the Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC). The closest direct antecedent, the Department of Energy, had closed in 1992 (Valenzuela & Rhys, Citation2022). DECC conducted a major re-design of the electricity sector through the 2013 Energy Act that created the renewable energy Contract for Difference (CfD) system, the UK variant of the renewable auction. The CfD is an instrument providing RE generators with compensations covering the difference between the agreed RE price and the market price. Hence, although the CfD was conceived to integrate seamlessly into the existing electricity wholesale market, it constitutes a major shift from the market because it implies a regulation of the problem of economic liability, as well as the choice of technology (through technology pots) and the volume of RE to be contracted.

An example of the implications of regulatory expansion is provided by a decision of the Conservative government to exclude onshore wind projects in England (cf. BEIS, Citation2021; Welisch & Poudineh, Citation2019), thereby responding to the party electorate’s discontent with onshore wind farms. Regulatory expansion allowed the government to guide the development of RE based on a variety of criteria, some non-economic, in response to emerging public and business opinion in a way that the market could not, as confirmed by an interviewee working for one of the largest generation companies. The IRA has maintained all of its competences over the wholesale market, but new agencies enter the scene to manage the expanding issues under regulation. For instance, the Crown States, the authority over the continent shelf, has become central to the development of the auction system because of the importance of offshore wind energy.

To manage the contract liability within this new RE policy instrument, the 2013 Energy Act created a new type of institution, the Low Carbon Contract Company (LCCC), a state-owned enterprise under the direct control of the Department that serves as the off-taker of all contracts and manages the system of payment from the auctions (DECC, Citation2014; Kern, Kuzemko, & Mitchell, Citation2014). The implementation of the auction itself is done by the Energy System Operator, originally integral part of the private operator, the National Grid, only to be partially unbundled in 2019, and meant to be nationalised in the coming years (BEIS and Ofgem, Citation2021). A nationalised system operator will represent an expansion of public agency roles to address challenges to energy security, economic competitiveness, and industrial manufacturing development. It is meant to match the shift to more state interventionism with the creation of new institutional competences and resources (MacLean, Citation2016, p. 21) that would be independent from both the government and sectoral commercial interests (BEIS and Ofgem, Citation2021, p. 21) ().

Table 2. Evolution of interventionism in electricity policy by policy instruments (UK).

Mexico

Since the nationalisation of the electricity industry in 1960, the Mexican electricity system developed based on a state-owned enterprise, the Comisión Federal de Electricidad (CFE), working as a monopoly in the generation and supply of energy. The monopoly was progressively eroded, through waves of reforms, starting in 1992, that partially privatised and liberalised the sector. Private production developed under different forms at the margins of the SOE. Power purchase agreements allowed private producers to sell energy to CFE serving there as a single-buyer. Besides, large consumers were allowed to produce energy for self-supply or sign supply contract with new private producers. To enable the growth of self-supply and for bilateral contracts, and to attend to the partial liberalisation of the gas market, the government created a regulatory agency in 1993, the Energy Regulatory Commission. Initially controlled by the government, the regulator gained progressive autonomy and could be considered an IRA already by 2004. The IRA supervised the relation between the SOE and private companies, but still had a limited remit of work. Decisions over investment projects and tariffs for final consumers remained in the hands of the SOE, with the approval of the Ministries of Energy and Finance.

In contrast to the UK, where renewable policy followed liberalisation, in Mexico renewable energy policy was entangled with liberalisation. In fact, the literature portrays renewable energy policies as a tool to further open the room for private sector operations and investment (Ruiz-Mendoza & Sheinbaum-Pardo, Citation2010). First, in 2010, the IRA devised a subsidy scheme consisting in heavy discounts on regulated tariffs for wheeling energy, that was accessible for companies formed by large consumers and renewable energy generation under a self-supply regime. This greatly favoured large scale consumers and private renewable energy producers at the expenses of the SOE who was cross-subsidising the scheme. While the SOE still held certain level of control through approval of interconnection, this new instrument significantly increased the IRA’s influence on sectoral governance (Valenzuela, Citation2023). Not long after, a liberalisation reform ensued.

The main liberalisation reform was legislated between 2013 and 2014, creating a wholesale market opened for unrestricted competition, but without the privatisation of the SOE. Under this hybrid model, the government utilised traditional regulatory tools to curve potential abuse of market power of the incumbent, including partial unbundling of the SOE business and mandating the most competitive power plants of the company to sign long-term contracts. It also unbundled the System Operator, CENACE, from the SOE and turned it into a public agency with technical autonomy under the authority of the Department of Energy (Hernández, Citation2018). The government ministerial offices stopped participating in power generation project approval, but the Ministry of Finance maintain the authority to set subsidised tariffs for final consumers. The IRA gained further independence from the government and the prospect of more competences. Former government officials confirmed the ministry’s preference to keep tight control over the implementation of the reform due to lack of trust over capabilities. Thus the new market rules were issued by the Ministry, and only then passed to the competence of the regulator in 2017, 4 years after the legal reforms (SENER, Citation2017).

As part of the reform, the government introduced a clean energy certificate quota system in 2015, regulating the volume to foster the expansion of renewable generation. The Ministry reviews the level of quotas for the next years, with the regulator in charge of issuing and supervising market participants’ compliance. To secure this new renewable energy supply, the government did not allow the SOE to develop its own projects, and instead established a system of long-term renewable energy auctions. Simultaneously, Mexico turned to auctions for promoting RE. Three auctions rounds were completed until a new administration in December 2018 decided to halt the process to undergo a new revision to electricity market legal framework. Whereas in the first two auctions, the demand pool was exclusively composed of the state-owned CFE, it then expanded to other market participants (large energy consumers and energy suppliers) but due to a lack of interest of the latter, the auctions had in practice remained essentially for the SOE. The IRA was going to hold the pen on auctions design starting from the fourth auction which was never completed due to the government choice to suspend them.

During the three completed auctions, SENER held full regulatory authority. Auction implementation is delegated to the System Operator, which amongst many specific functions produces a national map for adjusting economic offers based on present and modelled grid constraints to introduce price signals for the location of projects, instead of regulators’ intervention on location decisions. As expressed by business and government officials, for private developers, the crucial aspect was the length of contracts and the nature of the contract and offtaker. The government decided to not regulate technology, despite the preference of solar developers for technology specific auctions.

The suspension of auctions in December 2018 shows how influential ministerial authority is even in a recently liberalised markets. The current government (2018–2024) has respected all signed auction contracts, but has taken steps to eliminate the wheeling subsidy (Valenzuela, Citation2023). And in a move to regain control of the industry, in April 2023, the government purchased 77 per cent of all generation assets from the largest private energy company in Mexico, Iberdrola (Jopson et al., Citation2023). This nationalisation was a way, for the Mexican government, to bypass regulatory and judicial disputes with Iberdrola who, it was argued, had taken advantage of regulatory loopholes to push its interests to the detriment of CFE. Given that Iberdrola controlled over 50 per cent of Mexican generation capacity, this operation lead to a massive change in the ownership structure of the Mexican electricity sector, giving a forceful illustration of re-nationalisations as an instrument of executives’ comeback in electricity governance ().

Table 3. Evolution of interventionism in electricity policy by policy instruments (Mexico).

Morocco

Before Morocco started to open its electricity sector, all the electricity was produced by the Office National de l’eau et l’electricité (ONEE), the Moroccan public monopolistic company, also responsible for the transportation and part of the distribution of the electricity sector – the distribution being shared with other public and private companies. Privatisation has mainly been pursued via auctions combined with the single buyer model. As a result, most private generators sell the electricity produced to the incumbent. The implementation of this privatisation mechanisms is mainly in the hands of the ONEE, in charge of running the auctions, and the ministry.

Morocco has, since the late 2000s, set very ambitious renewable energy objectives that it has so far successfully complied with. Morocco’s RE policy relies mainly on RE auctions. The Moroccan Agency for Sustainable Energy (MASEN), set up in 2010, is the cornerstone of the RE auction regime. It is in charge of preparing, designing, implementing and following up on all auctions for the development of renewable energy in the country. Initially created for handling solar auctions only, its mandate was enlarged in 2016 to manage auctions for all RE sources, depriving ONEE from the related competences on non-solar RE auctions. Several important issues of the auction regime are defined ex ante by the electricity development plan. This regards in particular the definition of the demand (volume and budget cap, planification of auctions, choice of technology, size of the projects). The electricity developmental plan, elaborated by ONEE, is discussed and coordinated within an intergovernmental platform chaired by the prime minister and composed of a wide representation of Moroccan ministers, before being validated by ONEE and MASEN. All these issues are thus subject to a wide coordination including not only MASEN, the ONEE and the ministry of energy transition, but also many other ministries. The choices over most remaining issues involve a combination of MASEN with the ONEE and sometimes the ministry of energy transition. The Moroccan auction regime has been very successful in attracting foreign investment (Usman & Amegroud, Citation2019, pp. 42–46). The King’s personal commitment to it, in particular via governmental backup of RE purchase, his close influence on it and his political longevity combine to make the best possible guarantee of policy stability in the eyes of investors (Mathieu, Citation2023). This case illustrates how strong interventionism can foster investors’ trust in a policy regime.

Next to auctions, the RE policy regime includes another two instruments: authorisations and self-production. Whereas the auctions’ regime has been working very well, the authorisation and self-production regimes have so far been very partially implemented. The authorisation regime is a first step towards liberalisation – although without the creation of a wholesale market. Private investors can request the authorisation to sell renewable electricity directly to consumers, they would then pay a fee to the network owners for using the transportation or distribution networks. The ministry is the contact point, deciding on the granting of the authorisation. To be granted, the authorisation also requires the green light of ONEE who evaluates the technical feasibility of the connection to the network. Whereas this process has been applied – not without problems – for the high and very high voltage, it has so far not been applied to the opening of the medium and low voltage. For the high and very high voltage, in the absence of an IRAs to oversee this process – the IRA was set up in 2020 only – there was a lack of transparency on the incumbent’s decisions. While some investors got positive outcomes, many authorisations were rejected and voices among the industry argued that the incumbent’s many denials to grant network access were due to commercial more than technical reasons. For the medium and low voltages, although the law makes it possible to grant network access and foster decentralised production, obstacles manifested at the implementation stage, as several regulatory implementing decisions – for example regarding the grid code, tariffication of transportation – were simply not adopted.

As for the self-consumption regime, its application is also hampered by the lack of a complete regulatory framework. The main obstacle being the impossibility to re-inject excess production on the network. The current Moroccan energy minister is very committed to accelerate the energy transition and is actively working on pushing reforms ahead to make liberalisation under the authorisation regime a reality at all levels of the grid. The recent set up of the Autorité nationale de regulation de l’électricity (ANRE), the Moroccan electricity IRA, is also expected to speed up the application of the authorisation regime by facilitating the adoption of several key regulatory implementing measures ().

Table 4. Evolution of interventionism in electricity policy by policy instruments (Morocco).

Analysis

We find that all three instruments of regulation, re-nationalisation and governmentalisation are relevant in all three cases, although sometimes in different forms. Regarding regulatory expansion, we highlight UK's addition of location, off-taker and local integration regulation in auctions, in addition to volume and technology already in other renewable policies (FiT and quotas). In Morocco, auctions enabled the country to add a local integration regulation to an already highly regulated system. And in Mexico, the highlight is the attempt to keep regulation limited in line with liberalisation aspiration. Re-nationalisation is observed very differently, with UK creation of purpose specific national company (but not the old-style asset nationalisation), and in Mexico and Morocco it represented a conservation of state-owned operators. In the latter cases, governmentalisation is the most interesting feature, although less visible given the pre-eminence of SOEs. While in Morocco governmentalisation occurred through the creation and empowerment of a non-independent agency, it took place mainly through the empowerment of ministries in Mexico and UK.

We also see that policy instruments tend to show more interventionism over time (). While very clear in the UK case, the transition is less evident for Mexico and Morocco given pre-existing governance arrangement around state-owned monopolies but nevertheless present interesting evidence of repoliticisation.

Table 5. Degrees of interventionism by policy instrument, over time, in the UK, Mexico and Morocco (darker cells correspond to more interventionism).

The trend towards more interventionism is very clear in the UK. Having a completely liberalised policy regime as a starting point, the UK is positioned at the opposite end of the interventionism continuum on all three dimensions in the first phase. Any move could only be in the direction of more interventionism. Interestingly, the rise of interventionism does not come through with the first generation of RE policy instruments (2 and 3), but with the second generation of policy instruments (4). This shows that its RE policies do not automatically come with more interventionism, which depend more on the type of RE policy instruments and their calibration. At any rate, the observed evolution across RE policy instruments is consistent with our claim about the rise of interventionism over time. It is particularly interesting to observe such a neat shift towards increased governmental control of economic governance in a country that was at the forefront of the liberalisation reforms, being, for this reason, a least likely case for the development of interventionism. This provides a strong external validity to this result.

In Mexico, the trend is less obvious than in the UK, but still clearly identifiable. The starting point is the single buyer policy regime which is very interventionist already. The first generation of RE policy instruments (2 and 3) followed a liberal approach, hence diminished interventionism. A major difference here between the UK and Mexico is the respective timing of liberalisation and RE policy reforms. While they followed each other sequentially in the UK (first liberalisation, then RE policies), they took place simultaneously in Mexico, where liberalisation was initially seen as a way to promote RE – and vice versa. Hence, in this period, the new interventionist trend is not identified. However, the last generation of RE policy instruments (4 and 5) feature the comeback of interventionism to a degree that is similar to pre-RE and pre-liberalisation reforms while situated in a more liberal context. This evolution is similar to that observed in the UK, where the degree of interventionism of RE policy instruments increases over timebut it is less visible in Mexico because it happens in a shorter period of time and is partially intertwined with liberalisation reforms.

Morocco is the case where the trend towards increasing interventionism is less clear, due to the very limited engagement of the country with liberalisation reforms in the first place, yet there is still an expansion of interventions. The two RE instruments were adopted in 2010: the authorisation mechanism (instrument 2, inspired from liberalisation reforms, with a medium level of interventionism) and auctions (instrument 3, similar to Mexico’s and the UK’s second generation of RE policy instruments, with a high level of interventionism). The authorisation regime has been only very partially implemented, while the auctions regime has thrived. The difference highlights decreasing emphasis on the liberal instrument and a corresponding rising importance of the more interventionist instrument. This evolution is similar to what we observe in the UK and Mexico, where RE policies have also become more interventionist over time.Footnote3 Moreover, a key difference between the non-RE auction regime (instrument 1) and the RE auction regime (instrument 3) is the creation of MASEN as a non-independent agency centralising competences over auction design and implementation – previously exercised by the Moroccan SOE. The creation of MASEN, initiated and closely followed by the King, follows precedents where the King’s role in the creation of new technocratic actors is a way for the monarch to recover power from the government under the guise of ‘depoliticisation’ (Hibou and Tozi, Citation2002). So we face a shift of regulatory competence from the incumbent, i.e., a historic and large actor, to the benefit of a new and smaller actor, closely connected to the head of state.

Similar to the creation of MASEN, in Mexico, a critical actor in auctions is the System Operator, which was unbundled from the SOE and placed under the direct authority of the Ministry. In the UK, the system operator was also separated from the private grid company National Grid and is expected to be nationalised in the near future. In all three cases, we observe the shift of regulatory power from the incumbent to a smaller actor more closely connected to the executive. This suggests that organisational fragmentation, in particular via the creation of new actors, can co-exist with, and even foster, increased control of executives over sectoral governance if the new actors are closer to governments than incumbents of the regulatory regime such as SOEs or IRAs. More generally, this also shows that organisational fragmentation can thus serve both de-politicisation – e.g., with the creation of IRAs – or re-politicisation, depending on the profile of the new actors created, and how they fit in the organisational landscape – in particular their relationship with the executive.

We observe that all three countries’ display a high degree of interventionism in their more recently adopted policy instruments. Since the three countries have different starting points, the evolution of interventionism over time is very different. We have a clear rise in the UK, a drop followed by a rise in Mexico, and a relatively constant level in Morocco. First, sequence matters. In countries that are late adopters of liberalisation, both liberalisation and RE policy reforms overlap instead of following each other as in the UK. And when they overlap we observe the juxtaposition of mechanisms pulling in different directions. There is both a decline of traditional interventionism (via privatisation, but also with the creation of wholesale markets and IRAs in Mexico) and the development of renewed forms of interventionism (via renationalisation, regulatory expansion and the empowerment of new agents closely controlled by governments). This trend is clearer in Mexico. In Morocco, as liberalisation reforms were limited to the partial privatisation of electricity generation, there was hardly any drop of traditional interventionism preceding and new interventionism refers mainly to the transfer of competences from the SOE to the RE agency. Despite these different trajectories – which appear largely explained by both the timing and extent of liberalisation reforms – all three cases show the relevance of renewed forms of interventionism in sectoral governance.

Re-politicisation: regulatory instability or responsiveness

Repoliticisation of electricity governance has implications for regulatory stability and responsiveness to the public, two aspects that can be difficult to balance. Repoliticisation increases the visibility of the related policy issues, raising issue salience among the public and enhances accountability and democratic legitimacy mechanisms that were diluted with depoliticisation reforms when governments insulated themselves from the responsibility for policy or market outcomes. Repoliticisation could increase governments’ incentive to respond to society’s demand, as well as their capacity to be more responsive, by giving them more leeway to react to emerging demands and to process emerging and complex conflicts that lie beyond the capacity of markets and IRAs. But as a consequence, repoliticisation could also reduce the stability and predictability of regulation, which may undermine policy credibility, one of the problems that de-politicisation and delegation to IRAs pretended to avoid. An example of this was provided by the newly elected government of Alberta in Canada that cancelled the RE auctions that had been run and adopted by their political opponents when these were in office (Stephenson, Citation2019). Within our cases, Mexico provides another example of how new interventionism can create regulatory instability. After a political alternance in December 2018, the new government, not so favourable to existing RE policies and closer to supporting the SOE, cancelled the fourth auction round planned by the previous government – although not affecting signed contracts.

While new interventionism might foster regulatory instability, it does not necessarily create a more instable environment for investments. This contrasts with the literature emphasising IRAs’ contribution to a stable investment climate (Levy & Spiller, Citation1994; Majone, Citation1996 – but see Onoda, Citation2023 pointing at IRAs’ independence as a source of regulatory instability). In fact, new interventionist instruments are also meant as a way to palliate other types of instability, rooted in market, social or industrial uncertainties. Private investors and international financial institutions have found expansion of some forms of state interventionism favourable when these ‘de-risk’ private investment (Gabor, Citation2021). Where SOEs existed, as in Mexico, the SOE can be a means to de-risk private investment through long-term contracts (Valenzuela, Citation2023). In the UK, the new state-owned enterprise LCCC serves as a de-risking instrument to respond to private RE developers who wanted the long-term revenue certainty of government-backed contracts, in contrast to signing contracts with private market players with uncertain future under market conditions. MASEN has been described as an example of de-risking investment instrument (IEA-IFC, Citation2023, p. 86), and the King’s personal commitment to and close supervision of the RE auctions’ regime, namely via governmental backup of RE purchase contracts, was perceived by investors as the best possible policy credibility signal and was very successful in attracting international investment (Mathieu, Citation2023). As renewable energy technologies become more cost competitive, state intervention is best directed at de-risking to reduce financial cost, rather than providing subsidies to offset any additional costs that would make the projects competitive.

New interventionism may also be seen as a response to risks related to industrial or social uncertainty. Interventionism expands public authorities’ capacity to respond to emerging societal demands and industrial needs, which may reduce the impact from disputes over project sitting or delays to interconnection, which are important source of uncertainties for investors. While Koop and Lodge (Citation2020) see regulators becoming more responsive to societal demands, we see the whole state becoming more involved. The relationship between interventionism and policy stability is not as straightforward as suggested by the literature. We should also acknowledge that policy stability can both be undermined by de-politicised governance (Onoda, Citation2023) and fostered by interventionism. The Mexican choice to stop auctions and the generalised outcry of the industry are a crucial evidence of private actors’ expectation for state intervention to de-risk and scale up their investments. The wholesale market and bilateral contracts have been open to private investors, and yet the deployment of solar and wind in Mexico deaccelerated immediately. Crucially, the traditional instruments of liberal markets are not enough, which incentivises the state to intervene and gain control over the speed of renewable energy project deployment.

Conclusion

By showing how governments are getting back in electricity governance, this article contributes to documenting the comeback of economic interventionism through specific policy approaches, rather than major reforms. It contributes to its understanding it by identifying three key instruments of the new interventionism: re-nationalisation, regulatory expansion and regulatory governmentalisation. More generally, by bridging political economy and public policy approaches, it opens a venue for exploring the manifestations of the new interventionism in economic governance through the evolution of policy instruments, their calibration and implementation. Future work will be needed to provide more nuanced accounts of the extent, speed, and concrete manifestations of renationalisation, regulatory expansion and regulatory governmentalisation processes. Whereas this first exploration has been made on the electricity sector, similar studies can be extended to other sectors or public policies. Future studies can also look for other instruments underpinning the comeback of governments in economic governance. If this article can raise scholars’ interest in the comeback of interventionism in economic governance, this article will have achieved its major objective.

The article also contributes to the literature on (re)politicisation. Whereas most recent works on politicisation focus on the publicisation of issues (De Wilde, Citation2011; Kriesi, Citation2016), our work draws the attention to the importance of another – and less investigated – type of politicisation, the governmentalisation of public issues (Hay, Citation2007). The governmentalisation of public issues has also been barely addressed compared to the opposite phenomenon, de-politicisation that has received more attention (Buller & Flinders, Citation2005; Burnham, Citation2001). This calls for expanding investigations on the different forms of politicisation as well as their interaction. Future works could for example study the causal relationships between different types of politicisation, that is how and when issue salience and conflict trigger issues’ governmentalisation and how governmentalisation feeds back into issue salience and conflict.

The consequences of new interventionism and re-politicisation of economic governance constitute another promising line of investigation. For example, studies can evaluate the impact of new interventionism on the content of regulation, whether it enhances RE promotion policies or not, or the extent to which non-economic criteria influence regulatory decisions and the conditions affecting the balance between economic and non-economic criteria. This article has provided some examples of how new interventionism can affect the investment environment and the responsiveness of regulation, for example in response to rising politicisation (see also Koop & Lodge, Citation2020; Onoda, Citation2023). Future studies can investigate whether and under which conditions new interventionism allows creating an overall more stable environment to encourage RE investment, by removing important market, industrial and societal risks, or on the contrary whether political arbitrariness undermines the investment climate. Our findings also echo an emerging literature in development economics points at the growing role of state in de-risking investment from the private sector (Gabor, Citation2021). These findings provide an institutional explanation of how those de-risking tools, like renewable energy auction, are implemented trough the growing interventionism of the state, opening new debates about state interventions to serve private investors and new possibilities of regulatory capture that arise.

Finally, the article also contributes to the nascent literature on the transformation of the regulatory state. It confirms the trends already identified: the politicisation of regulation (Koop & Lodge, Citation2020; Onoda, Citation2023) and governments’ increasing interest in influencing regulation (Ozel, Citation2012; Rangoni & Thatcher, Citation2023). It also departs from these works in so far as it is not focused on IRAs but rather studies the repoliticisation and governmentalisation of regulation from a policy analysis angle. By studying the policy regime as a whole, it unveils evolutions that are invisible when looking at IRAs only. This approach is particularly relevant to point at the marginalisation of IRAs, via the empowerment of other actors closer to governments like SOEs, NIPAs or ministerial departments in the context of new policy instruments, suggesting a relative decline of IRAs in sectoral governance. This wider perspective – beyond the focus on IRAs – reveals that governments have several means to increase their influence on sectoral regulation to the detriment of regulatory agencies. Future works in this direction, for example adopting a holistic approach on regulatory governance (e.g., Jordana & Sancho, Citation2004; Mathieu et al., Citation2017) might further explore whether IRAs’ centrality in sectoral governance is evolving and why.

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to the reviewers and colleagues providing feedback in workshops, including in the Swiss Political Science Association and the regulatory governance community more broadly for their thoughtful comments, which have significantly contributed to enhancing the quality and strength of our arguments. Emmanuelle Mathieu would like to also thank colleagues from the University of Lausanne.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Emmanuelle Mathieu

Emmanuelle Mathieu is a senior lecturer at the Institute of Political Studies, University of Lausanne and a senior research fellow at IBEI.

Jose Maria Valenzuela

Jose Maria Valenzuela is a senior research fellow at the Institute for Science, Innovation and Society (InSIS), University of Oxford.

Notes

1 The point we make in this article is factual (more than causal). We highlight what we call a new interventionist trend without making any formal causal claim.

2 Interviewees gave informed consent to their participation, in written form wherever possible, and verbally when they expressed a clear preference for that option, as approved prospectively by the Institutional Commission for Ethical Review of Projects (CIREP) of the University Pompeu Fabra (CIREP nr. 0101) and by the Blavatnik School of Government Departmental Research Ethics Committee (SSD/CUREC1A/BSG_C1A-19-08/Amendment 02).

3 Reforms currently under considerations in Morocco may facilitate the implementation of the authorisation regime. So, this interpretation should be revisited in a few years based on updated data.

References

- BEIS. (2021). Contracts for difference scheme for renewable electricity generation allocation round 4: Allocation framework.

- BEIS and Ofgem. (2021). Future of the system operator-Impact assessment. December 21. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1066721/future-system-operator-consultation-impact-assessment.pdf.

- Bolton, R. (2021). Making energy markets. The origins of electricity liberalisation in Europe. EBook. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Buller, J., & Flinders, M. (2005). The domestic origins of depoliticisation in the area of British economic policy. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 7(4), 526–543. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-856x.2005.00205.x

- Burnham, P. (2001). New labour and the politics of depoliticisation. The British Journal of Politics & International Relations, 3(2), 127–149. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-856X.00054

- Davies, R. (2022). National grid to be partly nationalised to help reach net zero targets. The Guardian. 6 April. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2022/apr/06/national-grid-to-be-partially-nationalised-to-help-reach-net-zero-targets.

- DECC. (2014). Implementing electricity market reform (EMR). https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/324176/Implementing_Electricity_Market_Reform.pdf.

- De Wilde, P. (2011). No polity for old politics? A framework for analyzing the politicization of European integration. Journal of European Integration, 33(5), 559–575. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2010.546849

- Gabor, D. (2021). The Wall Street consensus. Development and Change, 52(3), 429–459. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12645

- Goldthau, A. (2012). From the state to the market and back. Policy implications of changing energy paradigms. Global Policy, 3(2), 198–210. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1758-5899.2011.00145.x

- Goldthau, A. (2014). Rethinking the governance of energy infrastructure: Scale, decentralization and polycentrism. Energy Research & Social Science, 1, 134–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2014.02.009

- Gross, R., & Heptonstall, P. (2010). Time to stop experimenting with UK renewable energy policy ICEPT Working Paper. ICEPT Working Paper.

- Hay, C. (2007). Why we hate politics. Polity.

- Hernández, C. E. (2018). Reforma Energética: Electricidad. FCE.

- Hibou, B., & Tozy, M. (2002). De la friture sur la ligne des réformes. Critique Internationale, 14, 91–118.

- Hochberg, M., & Poudineh, R. (2018). Renewable auction design in theory and practice: Lessons from the experience of Brazil and Mexico. Oxford Institute for Energy Studies.

- IEA and IFC. (2023). Scaling up private finance for clean energy in emerging and developing economies. https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/a48fd497-d479-4d21-8d76-10619ce0a982/ScalingupPrivateFinanceforCleanEnergyinEmergingandDevelopingEconomies.pdf.

- IRENA. (2019). Renewable energy auctions: status and trends beyond price. https://www.irena.org/publications/2019/Dec/Renewable-energy-auctions-Status-and-trends-beyond-price.

- Jopson, B., Stott, M., & Murray, C. (2023). Mexico hails ‘New nationalisation’ as Iberdrola sells $6bn of power assets and pivots to US. Financial Times (5 April).

- Jordana, J., & Sancho, D. (2004). Regulatory designs, institutional constellations and the study of the regulatory state. In J. Jordana, & D. Levi-Faur (Eds.), The politics of regulation. Institutions and regulatory reforms for the age of governance (pp. 296–320). Edward Elgar.

- Kern, F., Smith, A., Shaw, C., Raven, B., & Verhes, B. (2014). From laggard to leader: Explaining offshore wind developments in the UK. Energy Policy, 69, 635–646. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2014.02.031

- Kern, F., Kuzemko, C., & Mitchell, C. (2014). Measuring and explaining policy paradigm change: The case of UK energy policy. Policy & Politics, 42(4), 513–530. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557312X655765

- Koop, C., & Lodge, M. (2020). British economic regulators in an age of politicisation: From the responsible to the responsive regulatory state? Journal of European Public Policy, 27(11), 1612–1635. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1817127

- Kriesi, H. (2016). The politicization of European integration. Journal of Common Market Studies, 54(S1), 32–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12406

- Levy, B., & Spiller, P. (1994). Institutional foundations of regulatory commitment: A comparative analysis of telecommunications regulation. Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 10, 201–246.

- MacLean, K. (2016). Energy governance and regulation frameworks – Time for a change ?

- Majone, G. (1996). Temporal consistency and policy credibility. Why democracies need non-majoritarian institutions. EUI RSC Working Papers 57.

- Mathieu, E. (2023). Policy coherence versus regulatory governance. Electricity reforms in Algeria and Morocco. Regulation & Governance, 17, 694–708.

- Mathieu, E., Verhoest, K., & Matthys, J. (2017). Measuring multi-level regulatory governance. Organizational proliferation, coordination and concentration of influence. Regulation & Governance, 11(3), 252–268. https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12127

- Mazzucato, M., & Rodrik, D. (2023). Industrial Policy with Conditionalities: A Taxonomy and Sample Cases. IIPP. WP 2023/07.

- Newbery, D. (2005). Electricity liberalisation in Britain: The quest for a satisfactory wholesale market design. The Energy Journal, 26(1), 43–70. https://doi.org/10.5547/ISSN0195-6574-EJ-Vol26-NoSI-3

- Onoda, T. (2023). ‘Depoliticised’ regulators as a source of politicisation: Rationing drugs in England and France. Journal of European Public Policy. DOI: 10.1080/13501763.2023.2176909

- Ozel, I. (2012). The politics of de-delegation: Regulatory (in)dependence in Turkey. Regulation & Governance, 6(1), 119–129. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-5991.2012.01129.x

- Rangoni, B., & Thatcher, M. (2023). National de-delegation in multi-level settings: Independent regulatory agencies in Europe. Governance, 36(1), 81–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12722

- Reverdy, T., & Breslau, D. (2019). Making an exception: Market design and the politics of re-regulation in the French electricity sector. Economy and Society, 48(2), 197–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147.2019.1576434

- Rodrik, D. (2008). One economics, many recipes: Globalization, institutions, and economic growth. Princeton University Press.

- Ruiz-Mendoza, B. J., & Sheinbaum-Pardo, C. (2010). Mexican renewable electricity law. Renewable Energy, 35(3), 674–678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2009.08.014

- SENER. (2017). La SENER entregó a la CRE el paquete de primeras Reglas del Mercado Eléctrico. Press Release. Secretaría de Energía-México. https://www.gob.mx/cre/prensa/la-sener-entrego-a-la-cre-el-paquete-de-primeras-reglas-del-mercado-electrico-141628.

- Shih, C.-H., Latham, W., & Sarzynski, A. (2016). A collaborative framework for U.S. state-level energy efficiency and renewable energy governance. The Electricity Journal, 29(9), 21–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tej.2016.10.013

- Simmons, B. A., Dobbin, F., & Garrett, G. (2006). Introduction: the international diffusion of liberalism. International Organization, 60(4), 781–810.

- Sovacool, B. K. (2011). An international comparison of four polycentric approaches to climate and energy governance. Energy Policy, 39(6), 3832–3844. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2011.04.014

- Stephenson, A. (2019). UCP has killed off Renewable Energy Plan, but wind companies see a bright future. Calgary Herard. 3 July. https://calgaryherald.com/business/energy/renewable-energy-plan-officially-dead-but-ab-wind-companies-still-see-a-bright-future.

- Streeck, W., & Thelen, K. (2005). Beyond continuity: Institutional change in advanced political economies. Oxford University Press.

- Szabó, L., Bartek-Lesi, M., Dézsi, B., Diallo, A., & Mezősi, A. (2020). Auctions for the support of renewable energy: Lessons learnt from international experiences – Synthesis report of the AURES II case studies (Issue 817619). http://aures2project.eu/wpcontent/uploads/2021/06/AURES_II_D2_3_case_study_synthesis_report.pdf.

- USAID. (2019). Designing renewable energy auctions: A policymaker’s guide. https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1865/USAID-SURE_Designing-Renewable-Energy-Auctions-Policymakers-Guide.pdf.

- Usman, Z., & Amegroud, T. (2019). Lessons from power sector reforms: The case of Morocco. World Bank. http://hdl.handle.net/10986/32221 (July 29, 2021).

- Valenzuela, J. M. (2023). State ownership in liberal economic governance? De-risking private investment in the electricity sector in Mexico. World Development Perspectives, 31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wdp.2023.100527

- Valenzuela, J. M., & Rhys, J. (2022). In plain sight : The rise of state coordination and fall of liberalized markets in the United Kingdom power sector. Energy Research & Social Science, 94(November). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2022.102882

- Victor, D. G., & Heller, T. C. (2006). The political economy of power sector reform. Cambridge University Press.

- Wade, R. (2010). After the crisis: Industrial policy and the developmental state in low-income countries. Global Policy, 1(2), 150–161. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1758-5899.2010.00036.x

- Welisch, M., & Poudineh, R. (2019). Auctions for allocation of offshore wind contracts for difference in the UK. EL 33. OIES Paper.

- Wilks, S. (2005). Agency escape: Decentralization or dominance of the European commission in the modernization of competition policy? Governance, 18(3), 431–452. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0491.2005.00283.x