ABSTRACT

What is the relationship between regional inequality and political discontent in Europe? This special issue addresses this question by studying the influence of the subnational context. Specifically, it examines the impact of unequal social conditions and economic growth on political discontent with national and international politics, as expressed in political behaviour, public opinion and policy preferences. This introduction outlines a research agenda that establishes the context of the special issue. It explains the key concepts of interest, summarises significant empirical trends, outlines explanatory models and discusses methodological challenges. In addition to establishing the research agenda that serves as the analytical framework, this introduction also presents the core findings of the special issue and discusses broader implications for future research and practice.

Introduction

Societal challenges related to deindustrialisation, (de)globalisation and technological and demographic change have had a major impact on regional economic trajectories in Europe (Bouvet & Dall’erba, Citation2010; Heidenreich & Wunder, Citation2008; Iammarino et al., Citation2019). While some regions have become better off due to these changes, economic and social conditions in other places have declined. Some regions have experienced economic stability over time whereas others have experienced significant change (Mayne & Katsanidou, Citation2023). In Europe, regional economic inequalities have widened since the 1980s (cf. Schraff and Pontusson (Citation2024)). The global financial and economic crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic have served to further expose these spatial inequalities in economic prosperity and welfare. Major gaps have opened between places that have ‘pulled ahead’ economically and those that have been ‘left behind’ (Broz et al., Citation2021; Martin et al., Citation2021). At the same time, academic interest in discontent with domestic and international institutions is on the rise (Dür et al., Citation2019; Hobolt, Citation2016; Walter, Citation2021), and it appears that this political discontent follows a pronounced political geography (Broz et al., Citation2021; Colantone and Stanig, Citation2018a; Nicoli et al., Citation2021; Lipps & Schraff, Citation2021a).

While there is an established literature examining European areas in economic decline and the mitigating cohesion and regeneration policies at the regional and local levels (Blom-Hansen, Citation2005; Charasz & Vogler, Citation2021; Dellmuth & Stoffel, Citation2012; Dellmuth, Citation2021) and literature on electoral outcomes and attitudes, including populism, Euroscepticism and the Brexit vote (Colantone and Stanig, Citation2018a; Daniele & Geys, Citation2014; Hobolt, Citation2016; Hobolt & Wratil, Citation2015; Hobolt & de Vries, Citation2016; Vasilopoulou, Citation2016; Ejrnæs & Jensen, Citation2019, Citation2022), we have limited knowledge about how precisely the subnational context influences political attitudes and behaviour in relation to institutions, electoral outcomes and political preferences (MacKinnon et al., Citation2021; McKay et al., Citation2021; Steiner & Harms, Citation2023).

Extant research has pointed to the importance of residential context and geographical inequality for our understanding of people’s attitudes and preferences (Lipps & Schraff, 2021a; MacKinnon et al., Citation2021; Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2018; Hochschild, Citation2016). Yet, findings differ. Whereas some studies point to the link between political discontent and living in places that have experienced long-term relative economic decline (e.g., Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2018), others suggest that once the economic development of a place is controlled for, support for anti-system parties is just as likely to be found in well-off places (e.g., Dijkstra et al., Citation2020), or that over time there is no linear trend in the relationship between subnational economic conditions and Euroscepticism (Mayne & Katsanidou, Citation2023; Schraff, Citation2019).

This introduction establishes the framework for our special issue, which outlines a research agenda on the relationship between regional inequality and political discontent in Europe. The research agenda addresses several important questions: how can we define and measure regional inequality and political discontent? What theoretical models connect regional inequality with political discontent? What methodological challenges arise in examining this linkage? The introduction also outlines how the individual contributions to the special issue approach these questions, the insights they provide, the lessons that can be drawn across them and their broader policy implications. This special issue presents much-needed comparative, longitudinal and EU-wide perspectives by advancing our understanding of the relationship between subnational context in Europe and political discontent in different ways.

Empirically, the special issue draws on and proposes a variety of new measures of the extent to which regions in Europe have been ‘left behind’. This allows the contributions of the special issue to map variations at the regional and/or local levels and link them to political opinions, preferences and voting results. Articles in the special issue adopt a demand-side view of political discontent, contributing to the existing supply-side literature that has examined how political elites and parties generate or politicise discontent through the articulation of place-based divisions (Jacobs & Munis, Citation2023; Haffert et al., Citation2024).

Theoretically, the contributions develop and test several models for how a specific geographical area shapes citizens’ attitudes on dimensions of political discontent, which adds to existing models by factoring in how the spatial context matters. In doing so, we push the frontiers of theorising when it comes to models of political discontent, systematically adding perspectives on the importance of subnational context.

Methodologically, the special issue applies a multi-method approach, including time-series cross-sectional models, cross-sectional models of original data and experimental designs. Several studies take a comparative longitudinal approach to highlight the analytic importance of moving below the national level and consider relative changes over time to understand political discontent in Europe. Others collect original cross-sectional survey data to measure novel concepts, such as bias perceptions or place-based resentment. Finally, this SI benefits from also looking at electoral geography, showing how regional inequalities can manifest in local political outcomes.

Defining and measuring regional inequality

The terms ‘left-behind places’ (MacKinnon et al., Citation2021), ‘places that do not matter’ (Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2018) and ‘geography of discontent’ (McCann, Citation2020) have been used by a growing community of scholars working in various social science disciplines. The concepts apply to regions where residents express a sense of marginalisation, which has been linked to support for populist parties, Brexit in the United Kingdom, the election of Donald Trump in the United States, opposition to European integration and the globalisation backlash (Ejrnæs & Jensen, Citation2019, Citation2022; Guilluy, Citation2019; Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2018; Vasilopoulou & Talving, Citation2020; Walter, Citation2021). However, these terms are not always clear as they are multi-dimensional in nature and used in various ways (MacKinnon et al., Citation2021). There are many types of places: some which have experienced decline, others which are catching up and some which have remained stable (Mayne & Katsanidou, Citation2023). At the same time, the qualities of a ‘left-behind’ place might differ depending on the country context, i.e., between northern, southern, western and eastern European countries.

When it comes to regional inequality, studies tend to primarily focus on economic factors, most often measured in relation to the regional gross domestic product (GDP) (Beramendi, Citation2012; Hendrickson et al., Citation2018; Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2018). From this perspective, ‘left-behind places’ in Europe are characterised by economic underperformance compared to the national average (Stiglitz et al., Citation2009). This is due to long-term developments of deindustrialisation, trade liberalisation and technological changes that have led to declining or stagnating real wages, further exacerbated by economic crises and austerity policies (Beckfield, Citation2019; Gray & Barford, Citation2018). Indeed, individuals in low-income and stagnant areas have lower political efficacy and less confidence in political institutions (Lipps & Schraff, 2021a). Moreover, concentrated economic shocks, such as declines in local manufacturing and import competition, have triggered political discontent (Colantone and Stanig, Citation2018a, Citation2018b; Nicoli et al., Citation2021).

Other studies have pointed to the need to broaden the scope beyond purely economic factors when identifying left-behind places. This body of work highlights the importance of examining population concentration in the so-called ‘brain-hub’ cities (Moretti, Citation2012). The underlying reason for this is often seen in urbanisation or metropolitisation, where resource-rich and skilled people move to the big cities, often to work in high-skill, high-wage, high-value-added sectors (Benson & Jordan, Citation2007; Leibert & Golinski, Citation2016; Wagner, Citation1890). This phenomenon tends to be measured by population density and the distribution of different types of occupations and education in different places. However, it is not only people who are increasingly concentrated in the big cities, but also critical resources and institutional infrastructure. Spillover effects of regional economic decline include impacts on investment, property values, local taxes and local services, including policing, school, healthcare and social care (Broz et al., Citation2021). Following that, initial studies demonstrate increased support for populist far-right parties in areas affected by public service deprivation or property value changes (Cremaschi et al., Citation2022; Adler & Ansell, Citation2020).

A final strand of literature introduces historical legacies as explanations for differential economic performance and political outcomes at the local level. Positive long-term effects of early local democratic institutions have provided an economic head start for certain regions (Doucette, Citation2024). Moreover, a legacy of historical political conflicts can generate local differences in the mobilisation potential for populist far-right parties (Haffert, Citation2022). Pointing to the role of historical factors underlines the strong potential of regional inequalities to be ‘sticky’, and suggests that a temporal variation in the geography of discontent also relies on supply-side factors of the political system that mobilise local discontent.

The above viewpoints emphasise objective features of the physical environment, such as poor growth, population density, housing markets, public services or historical institutions. There is also a line of research on left-behind places that focuses on the subjective feeling of marginalisation related to one’s living environment. People may reside in a large, wealthy metropolis, but in a stigmatised neighbourhood with social housing; or they may live in an affluent suburb but feel isolated from the rest of society as it develops in a direction which is antithetical to their values. This calls for ‘bringing social marginality back in’, as suggested by McKay et al. (Citation2021), placing the spotlight on people with perceived social status decline (Gidron & Hall, Citation2020).

Moreover, while strong economic decline and economic shocks may partially explain local backlash against European integration (Carreras et al., Citation2019; Colantone and Stanig Citation2018a; Nicoli et al., Citation2021), most regions in Europe have not experienced major economic decline (Heidenreich & Wunder, Citation2008; Mayne & Katsanidou, Citation2023). The decline of local areas is often related to stagnation rather than absolute losses in economic wealth, and yet the result is often still a feeling of being ‘left behind’ by the political establishment, which favours economically thriving areas (Huijsmans et al., Citation2021; Leibert & Golinski, Citation2016; Munis, Citation2020). This poses a puzzle regarding the type of local contextual changes that are politically consequential in an integrated but polycentric European Union (EU). Recent advances in the study of interpersonal redistributive preferences underline the importance of distinguishing between relative and absolute income changes (Weisstanner, Citation2022). It is still largely unclear whether absolute or relative changes in regional inequality are consequential for understanding political discontent in Europe. Further, the question of ‘relative to what?’ gives rise to a puzzle about the benchmarks citizens use to evaluate the role of their regional context within the European political system (Lipps & Schraff, 2021a; de Vries, Citation2018).

Defining and measuring political discontent

Political discontent can be defined in both minimal and maximal terms (Craig, Citation1980; Jennings et al., Citation2016). In this special issue, we apply a maximal definition by considering political discontent to be a multidimensional phenomenon related to the three key components or objects of the political realm: the polity (institutions), politics (actors and processes) and/or policy (system performance such as policies). These can relate to different levels of governance, such as global, continental, national, regional and/or local.

First, distrust in national and international political institutions refers to a lack of trust in the processes and structures of authority at different levels, such as national parliaments or the European Parliament. Distrust often stems from disappointment with the functioning of political institutions, which are perceived as untrustworthy due to incompetence or the pursuit of their own interests or the interests of elites (Bertsou, Citation2019). Widespread distrust in political institutions may undermine the quality of democratic representation or trust in democracy itself (Bertsou, Citation2019).

Second, anti-establishment attitudes and behaviours vis-à-vis actors and processes can be described as beliefs and behaviours that express doubt about the legitimacy of mainstream or established political parties and other actors in the realm of politics, including the bureaucracy or interest groups (Rooduijn et al., Citation2014). Citizens espousing such views tend to challenge existing societal norms and ideals and seek fundamental political change. Anti-establishment sentiments are often strongly associated with preferences for political challengers who seek to disrupt the dominance of mainstream parties, such as populist and Eurosceptic parties (Rooduijn et al., 2014).

Third, dissatisfaction with system performance and policy outputs relates to, for example, evaluations of the current state of affairs, including the economy, the way the government is doing its job and the way democracy works (Quaranta & Martini, Citation2016). Similar to distrust in institutions and anti-establishment sentiments, this is often based on the view that the status quo is not working for citizens and that fundamental changes are needed. However, in contrast to the other two components of political discontent, which capture political actors, processes and institutions, this dimension taps into evaluations of the performance, policy outputs, outcomes and impacts of the political system.

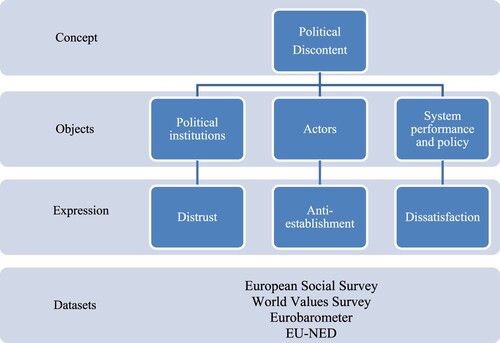

summarises our conceptualisation of political discontent over its three main objects and their expressions and presents a selection of data sources for the study of these phenomena. Comparative public opinion datasets like the World Values Survey (WVS), the European Social Survey (ESS) or the Eurobarometer Survey can be used to measure components of the distrust, anti-establishment and dissatisfaction dimensions of discontent at the subnational level. Behavioral expressions of anti-establishment voting can be tapped by the European NUTS-Level Election Database, which records voting results for national and European elections for all European countries on a comparative subnational level, e.g. the NUTS-level. The NUTS classification (Nomenclature des Unités territoriales statistiques) is often used to geographically categorise European regions into three different levels based on population thresholds.Footnote1 The NUTS 1 level includes major socio-economic regions, the NUTS 2 level comprises basic regions for the application of EU regional policies, and NUTS 3 covers small regions. maps political discontent related to political institutions, actors and performance, providing the basis for exploring the geographical variation in political discontent across European regions. The indicators related to political institutions are trust/distrust in the national parliament and the European Parliament. Indicators related to political actors include trust in political parties and populist vote share. Indicators of system performance are mapped using questions about satisfaction or dissatisfaction with how democracy is working. The chosen indicators represent some of the key dependent variables used in this special issue (see later in this introduction).

Figure 1. Political discontent: concept, objects, expressions and dataset examples.

Note: EU-NED refers to the European NUTS-Level Election Database.

Table 1. Overview of contributions.

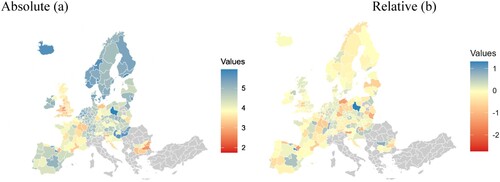

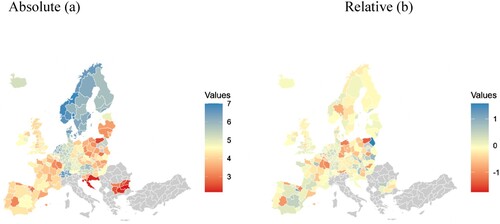

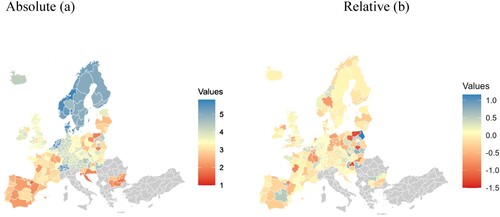

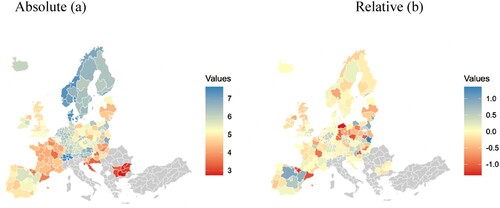

show variation on a range of indicators of political discontent across European regions, using data from the ESS (Citation2018).Footnote2 Levels of trust and satisfaction are measured on a 10-point scale, where 10 is the highest value and 0 is the lowest. In Germany and the United Kingdom, the ESS provides information only at the higher NUTS 1 level, while NUTS 2-level information is available for the rest of the countries included. The left panel on the figures shows absolute regional variation in political discontent, while the right panel shows relative regional variation compared to the national average. The dark red colour indicates lower scores than the average, and the blue colour indicates higher scores than the average. Red colours thus indicate hotspots of political discontent.

Figure 5. Satisfaction with democracy: Absolute (a) Relative (b).

Note: The right panel on Figures 2–5 shows absolute regional variation in political attitudes, while the left panel shows relative variation compared to the national average. The indicators of political discontent are based on data from European Social Survey (ESS) Round 9 (2018).

In and we focus on trust in political institutions at both the national and EU levels. We observe lower regional variation across Europe in terms of trust in the European Parliament compared to trust in national parliaments. Regions in both eastern and southern Europe (Spain and Portugal) have much higher trust in the European Parliament compared to their national parliaments (a and a). Looking at the relative measures of trust in the European Parliament, we find the same pattern as for relative trust in national parliaments (b and b). Regions in eastern Germany and north-eastern France exhibit low trust in the European Parliament, while some of the capital regions, such as London, Brussels and Paris, have higher trust in the European Parliament compared to the national average.

The map of absolute levels of trust in national parliaments (a) shows that regions in Spain have significantly lower levels of trust than the rest of western Europe. Again, we find the highest levels of trust in national parliaments in regions in the Nordic countries, the Netherlands and Switzerland. If we look at relative levels of trust in national parliaments, we find that regions in eastern Germany, north-eastern France and northern Poland exhibit the lowest levels of trust compared to the national average (b).

Established national political parties are, of course, key political actors. Levels of trust in national parties give an indication of the level of anti-establishment sentiments. In general, regions in eastern Europe have lower levels of trust in national parties (a), with regions in Bulgaria and Croatia showing the lowest levels. Among western European countries, regions in France have the lowest levels of trust in national parties. The relative level of trust in national parties is again low in regions in eastern Germany, such as Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, as well as in some of the Basque and Catalonian regions of Spain (b).

In a and b we focus on the performance of the political system. Regions in northern Europe, Switzerland and Austria exhibit the highest levels of satisfaction with democracy (a). Eastern European regions have the lowest levels of satisfaction, particularly those in Bulgaria, Croatia, Latvia and Lithuania. We also observe relatively low levels of satisfaction with democracy in France, Spain and Portugal. When it comes to relative differences in satisfaction with democracy, i.e., compared with the national average, we see that regions in eastern Germany have considerably lower satisfaction compared to other regions in Germany (b). We also observe lower levels of satisfaction with democracy compared to the national average in the former industrial and rural regions of northern and eastern France. In Scandinavia, we find much lower levels of within-country regional variation.

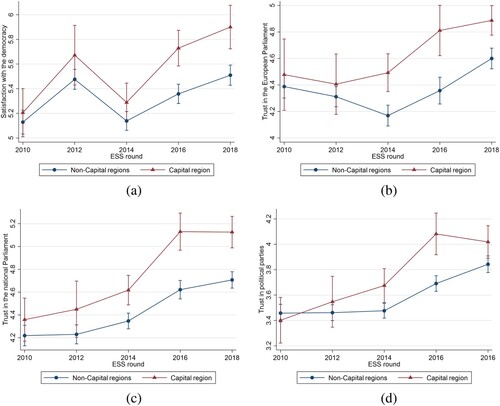

Based on the ESS waves 2010–2018, (Panels a-d) plots temporal trends in political discontent, differentiating between the estimated level of discontent in the capital region versus other regions in the country. It points to increasing geographical polarisation in political discontent, as the gap between the capital regions and everywhere else widens over time across most indicators of political discontent. This pattern is confirmed when looking at recent temporal trends in anti-establishment voting in European regions (e.g., during the 2022 Swedish election the Sweden Democrats increased their vote shares across the country, but not in the capital region of Stockholm).

Figure 6. Polarisation in political attitudes (Capital regions vs non-capital regions): Satisfaction with democracy (Capital region vs other regions) (a) Trust in European Parliament (Capital region vs other regions) (b)Trust in national parliament (Capital regions vs other regions) (c) Trust in political parties (Capital region vs other regions) (d).

Note: The indicators of political discontent are based on data from European Social Survey Rounds 5-9 (2010, 2012, 2014, 2016, 2018) in Austria, Belgium, Switzerland, Czech Republic, Germany, Denmark, Estonia, Spain, Finland, France, UK, Ireland, Lithuania, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Sweden and Slovenia. In Denmark and Austria, data was not available for all five rounds of the European Social Survey (ESS). The figures are controlled for country level variation.

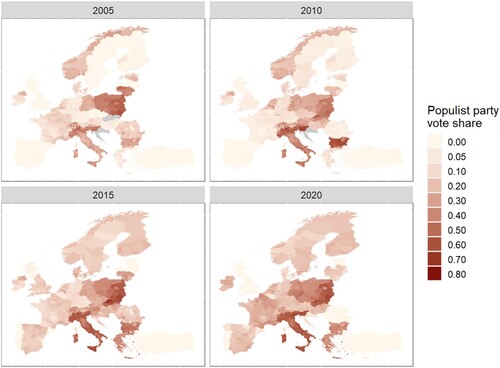

presents vote shares for populist parties across European regions in the period 2005–2015, indicating that populist voting increased substantially in many parts of Europe, such as Scandinavia, southern Europe, and some western European states. Comparing the regional rise of populist voting with the public opinion figures also suggests an association with different attitude-based expressions of discontent, with populist voting being more pronounced in north-eastern France, eastern Germany and eastern Poland and less pronounced in many of the capital regions.

Figure 7. Populist vote shares in national parliamentary elections across European regions, 2005–2020.

Note: NUTS 2/3-level vote shares of populist parties in national parliamentary elections taken from EU-NED (Schraff et al. 2022). Coding of parties is based on the PopuList (Rooduijn et al. 2019) .

These figures depict significant geographical disparities in political discontent within and among European states when it comes to distrust in institutions, anti-establishment sentiment and dissatisfaction with political outcomes. There has also been an increase in regional polarisation between capitals and the rest of the country, along with rising support for populist parties. The objective of this special issue is to clarify how regional inequality contributes to our understanding of the regional variation in political discontent. In the following section, we theoretically outline some of the primary factors driving political discontent at the regional level.

Theorising the relationship between regional inequality and discontent: three models

The relationship between geographic inequality and political discontent may be broadly categorised into three models: economic, identity and benchmarking.

Economic drivers of discontent

The starting point of this approach is that economic development trajectories tend to be territorially unequal across Europe (and the world). Economic globalisation and the transition to the knowledge economy have accelerated regional and local economic divergence. As economies grow, people and production tend to concentrate in larger, high-productivity cities, which have a comparative advantage due to agglomeration, density and low transport costs. Consequently, poorer regions tend to be stuck in income traps (Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2018; Martin et al., Citation2021). Growing inequality between knowledge-intensive, innovation-based regional economies and stagnating regions – often former industrial hubs – tends to be associated with economic, social and political instability (MacKinnon et al., Citation2021).

Citizens react to the economic situation of their communities in multiple ways, including politically (Bisgaard et al., Citation2016; Margalit, Citation2011). People take socio-tropic economic cues from their residential surroundings and use them for their evaluations of political institutions and actors and their performance. Living in non-economically dynamic areas entails experiencing economic grievances, lack of opportunities and a feeling of limited prospects. These lived experiences often translate into support for anti-system ideas and actors, lack of trust in the system and opposition to international cooperation (Dijkstra et al., Citation2020; MacKinnon et al., Citation2021). Lack of effective compensation of the regional losers of globalisation is a core driver of discontent (Schraff Citation2019). For example, the Brexit vote was systematically concentrated in regions more exposed to Chinese and central-eastern European imports due to regional sectoral specialisation, leading to a political backlash against declining manufacturing (Colantone and Stanig Citation2018a; Nicoli et al., Citation2021). Regional inequality of income and wealth can also be seen in terms of regional housing market dynamics. Support for Brexit in the United Kingdom and for Marine Le Pen in France was systematically lower in areas that have benefited from house price inflation (Adler & Ansell, Citation2020).

Identity drivers

Beyond utilitarianism, localised economic stress and bleak prospects for improving living standards are also associated with defensive perceptions of local identity, rural consciousness or place-based resentment (e.g., Cramer, Citation2016; Hochschild, Citation2016; Munis, Citation2020). Social identity theory suggests that individuals make sense of the world with reference to in-groups and out-groups (Billig & Tajfel, Citation1973; Tajfel, Citation1974; Tajfel & Turner, Citation1979). According to Munis (Citation2020, p. 1057), place-based resentment may be defined as ‘hostility toward place-based outgroups perceived as enjoying undeserved benefits beyond those enjoyed by one’s place-based ingroup’. When this identity becomes politicised, it entails a severe sense of injustice and neglect. Central political elites are perceived to be distant, disregarding the relative deprivation of rural areas and failing to take action to address it (Cramer, 2012; Hochschild, Citation2016; Mattinson, Citation2020). Local context dynamics, such as the decline of local socio-cultural hubs, tend to increase a sense of social isolation, lack of connectedness in the community, status decline and local identity loss, which are all associated with far-right party support (Bolet, Citation2021).

Material insecurity and relative deprivation can produce additional responses related to identity, such as disappointment and anger against the establishment and a feeling that the political system does not consider the needs of one’s region (McQuarrie, Citation2017). Regional resentment is not necessarily a rural-only phenomenon, but can also be a ‘peripheral region’ one, i.e., possible in any region that is ‘located further from the political, cultural and economic centre’ (De Lange et al., Citation2023: 404). For example, nationalist, anti-immigration and Eurosceptic attitudes are more likely to be expressed among those individuals who live in less-urbanised municipalities. On the other hand, people’s optimism towards a shared future often translates into ‘the formation of shared values, and citizens’ willingness to cooperate and compromise’ (Lipps & Schraff, 2021a: 897). It is also important to note that there is substantive diversity even among the ‘places that don’t matter’, i.e., discontent can be linked to different types of grievances depending on type of area (McKay et al., Citation2021; Harteveld et al., Citation2022).

Benchmarking

Benchmarking theory has gained popularity in explaining political discontent in Europe in general (Ejrnæs & Jensen, Citation2019; Talving & Vasilopoulou, Citation2021; de Vries, Citation2018) and at the regional level in particular (Lipps & Schraff, 2021a; Hegewald, Citation2024). This may be due, in part, to the fact that the theory integrates material and identity-based explanations related to the occurrence and intensity of political discontent. The fundamental mechanism of this theory lies in the comparison of one's own political unit (in this case a region) to other political units, including regional, national or European, often in terms of the economy, but also in terms of other metrics such as institutional quality (Ejrnæs & Jensen, Citation2019).

This may lead to the development of three different mechanisms. First, it is plausible that individuals tend to express political discontent when they compare the economic trajectory of their region to other regions (including the capital) or to its own past and its potential future direction (see Schraff and Pontusson (Citation2024); Vasilopoulou and Talving (Citation2024); Ejrnæs and Jensen (Citation2024)). Second, it is possible to envisage a process in which successful regions will be looked to as models for implementing effective policies that contribute to economic growth. Finally, people benchmark political regime alternatives against each other, such as comparing their state’s political system with the EU’s regime, extending more support for the alternative they find more appealing (de Vries, Citation2018; Ejrnæs & Jensen, Citation2019). This process is also informed by subnational conditions, as, for example, residing in a left-behind place reduces people’s support for the national regime, which in turn can alter the benchmarking process against the EU’s regime (Lipps & Schraff, Citation2021a).

Modelling the relationship between regional inequality and discontent: methodological challenges

Most articles in this special issue integrate longitudinal comparative survey datasets with regional data at the subnational level. Using longitudinal comparative surveys has two major advantages: it allows us to examine how social, economic and institutional conditions at the regional level influence political behaviour and attitudes; and it permits us to investigate how temporal change within a region influences political discontent.

Several articles employ distinct multilevel regression specifications, which are able to handle hierarchical data. In this special issue, up to four levels are addressed: individuals (1) nested in regions and waves (2), nested in regions (3), nested in countries (4). Such models provide an analysis of data at several levels within the same model and allow the joint inclusion of individual and contextual factors at the regional and national levels. Multilevel modelling permits the analysis of heterogeneity, which entails that the influence of a lower-level variable (e.g., education or class) is moderated by a higher-level contextual variable (e.g., regional or country development) (Steenbergen & Jones, Citation2002).

With the growing availability of large-scale international surveys, multilevel analyses have become increasingly prominent in the field of comparative social science. Most studies that use international survey data, however, use countries as the primary higher-level contextual entity and focus on the cross-sectional relationship. These studies face a range of methodological challenges. We focus on four key challenges that are of relevance to our special issue.

First, the number of cases in a research design with countries as the higher-level units is relatively small. The ability to introduce statistical controls for different country levels is relatively limited. Empirical findings are then likely to be sensitive to the countries and variables included in the analysis (Fairbrother, Citation2014; Giesselmann & Schmidt-Catran, Citation2019). We circumvent this small-N problem at the contextual level by making the regional level the principal contextual element. By integrating comparative survey and regional data, it is possible to compare regions not just between European countries, but also within countries. This, for example, provides an opportunity to examine political discontent in a region that lags behind the national context in terms of income and employment. Therefore, this special issue makes an empirical contribution by analysing how regional inequality within and between countries impacts political discontent.

The second challenge concerns the disparate understanding of longitudinal and cross-sectional relationships, often described as within (longitudinal) or between (cross-sectional) effects. It is frequently assumed when working with comparative longitudinal data that the longitudinal and cross-sectional effects are the same. However, this is often incorrect (Fairbrother, Citation2014). The complexities emerging from considering within and between effects are related to a general question about the relative advantages of fixed versus random effects models (Bell & Jones, Citation2015). The fixed effect model focusing on within effects has the advantage of controlling for all temporally stable unit characteristics. As such, it is restricted to estimating how changes in regional context over time within a region influence changes in political behaviour and attitudes. The problem with this specification is that all time-invariant variables are eliminated, so we lose a large amount of important information (Bell & Jones, Citation2015). Random effects models, in contrast, allow for the investigation of within and between effects, but this comes with a potentially lower degree of statistical control at the contextual level. Methodologically, this special issue points to the importance of separating the cross-sectional (between-region effect) and longitudinal effects (within-region effect), demonstrating the distinct nature of structural and dynamic explanations of political discontent (see Ejrnæs & Jensen, Citation2024).

Self-selection is a third challenge associated with studies of the subnational context. The central question is whether the regional context shapes certain attitudes and behaviours, or whether people with similar values and lifestyles self-select into regions with those who share their values and lifestyle (Martin & Webster, Citation2020; Maxwell, Citation2020). This is an important debate on the central mechanisms producing the political geography we observe. Compositional changes are often salient drivers of political backlashes, e.g., due to immigration flows (Maxwell, Citation2020). Contextual changes, however, have also been shown to produce political backlash, such as local trade shocks (Colantone and Stanig Citation2018a; 2018b; Nicoli et al,. 2022). This special issue puts a stronger emphasis on contextual changes, tracing them with an unprecedented spatiotemporal scope across Europe. This comes with the important caveat that some reported contextual effects might be affected by selection effects, and disentangling this provides an important avenue for future research. Individual-level panel and (quasi-)experimental designs would be more applicable for tackling selection effects, but this often comes at the cost of external validity as these research designs are usually restricted to single-country studies. Most contributions in this special issue prioritise external validity for the purpose of broadening our understanding of the manifold associations between regional inequality and political discontent. However, some contributions in this special issue also provide causal identification strategies for contextual effects (see Celli and Ferrante Citation2024).

A final methodological challenge emerges from the quality of comparative survey data at the subnational level. Most comparative social survey programmes are aimed at providing a valid and reliable picture of public opinion across the involved countries. Subnational public opinion estimates are usually plagued by low samples sizes (increasing random measurement error) and limited representativeness (e.g., risk of systematic measurement errors).Footnote3 The multi-level modelling approach applied in several contributions of this special issue partly addresses these concerns due to partial pooling of estimates across regions and the addition of socio-demographic control variables at the individual level (see the evaluation study by Lipps & Schraff, Citation2021b). Another way to avoid this issue with comparative surveys is to analyse aggregate behavioural data, such as election results, at the regional level, looking at expressions of political discontent across areas. Recent contributions provide readily available data for subnational election results across Europe (Schraff et al., 2022). This, however, cannot replace the value added by comparative survey data for understanding opinion formation and the multi-dimensionality of political discontent. Rather, we think that a joint consideration of individual opinion-based measures and regionally aggregate expressions of political discontent promises to point us to certain general explanatory patterns, which is why this special issue presents contributions covering both types of data.

The contributions of this special issue

The contributions to this special issue consider the three objects of political discontent, including political institutions, political actors and processes, and/or system performance and policy. They also study discontent through economic, identity and benchmarking theoretical frameworks. provides an overview of the articles, some of which occupy several cells as they deal with more than one dimension of political discontent or potential drivers.

Several of the articles in our special issue look at economic drivers of political discontent with political institutions. Vasilopoulou and Talving (Citation2024) challenge the linear prediction of the relationship between regional inequality and trust in the European Union (EU). They argue for a nuanced understanding by exploring three facets of regional inequality: the status of regional wealth, its growth and how this growth interacts with different wealth levels. Their analysis of Eurobarometer survey data from 2015 to 2019 reveals a non-linear association, where both poor and rich regions exhibit higher EU trust levels than middle-income regions. Furthermore, they find that growth in regional wealth significantly boosts EU trust, especially in poor and middle-income regions, suggesting a complex dynamic in public Euroscepticism influenced by regional economic factors.

Dellmuth (Citation2024) draws on economic theory to develop and test two competing hypotheses about the effects of regional economic development on political trust. While the first hypothesis predicts that residents of high-income regions trust political institutions more irrespective of the national context, the second expresses the counterargument that political trust is higher in regions that are economically advantaged within a country, as people use their country as a reference point. Analysing data from the European Values Study and World Values Survey, the article compares the effects of regional economic development on political trust in a sample of EU regions to a sample of global regions outside the EU. The findings from the sample of EU regions suggest that residents in high-income regions tend to trust government more, which corroborates the first hypothesis, but residents in the same regions trust the EU less. Moreover, in the global sample of regions outside the EU, people in poorer regions tend to trust political institutions more, be they national or supranational. These diverging findings in the EU and the global sample depend at least partially on the level of democracy in a country. When examining only democracies in the global sample, the results underline that regional income tends to strengthen political trust.

Ejrnæs and Jensen (Citation2024) investigate how the decline in manufacturing employment affects political discontent in European regions, employing data from the European Social Survey and the European Commission. The study finds that regions experiencing a reduction in manufacturing jobs show increased political discontent, particularly in the form of dissatisfaction with government, which can lead to diminished trust in political institutions and actors. The article also shows that discontent is more pronounced among native-born individuals, the lower social classes and rural residents. More generally, the article underscores the impact on status and identity due to changes in manufacturing jobs as a likely driver of a geography of discontent by controlling for economic factors such as unemployment and GDP.

Some articles in our special issue look specifically at economic drivers of political discontent with political actors and processes by studying either government support or support for antiestablishment parties. Celli and Ferrante's (Citation2024) study examines the electoral response in Italian local labour markets most impacted by the Great Recession, utilising a causal matching estimation strategy. Their analysis reveals a significant decrease in votes for incumbent Berlusconi’s party in areas hard-hit by the crisis, particularly in local labour markets with lower institutional quality and in central and island regions of Italy. Contrary to expectations, they find no effect of the local economic shock on voting for anti-European parties, indicating that the most affected local labour markets primarily used their vote to penalise the incumbent party, perceived as responsible for the economic downturn.

Schraff and Pontusson's (Citation2024) study examines both economic and benchmarking drivers of discontent. Their study analyses dynamic associations between economic geography and right-wing populist voting in Europe, covering a large subnational dataset from 1990 to 2018. In core EU countries, right-wing populist party support increases in regions lagging behind the wealthiest region in the same country, while in peripheral EU states, discontent grows in areas falling behind the EU core. Their findings suggest that right-wing populist party voters in peripheral countries benchmark their situation to economic developments in the EU core, in contrast to those in core countries, who focus on trends in domestic regional disparities.

Im (Citation2024) studies the economic but also political drivers of discontent with policy/output in terms of green transition, a process that increases the risk of job losses within regions that are more dependent on fossil energy. The study examines the impact of industrial decarbonisation on perceptions of political and economic unfairness in regions dependent on carbon-intensive industries. Analysing data from 60 Western European regions, Im (Citation2024) finds that perceptions of unfairness increase only in areas that experience both higher CO2 emissions and higher employment declines in these sectors compared to other regions of their country, pointing to an interesting interaction between local context conditions and changing economic fortunes.

Reinl, Beetsma and Nicoli (Citation2024) also study economic drivers of discontent with European policy, analysing subnational heterogeneity in an EU-wide conjoint experiment measuring support for joint European medical procurement during the COVID-19 pandemic. Their analysis provides strong support for collective rationalism, as regional need (e.g., hard-hit by pandemic) and local wealth emerge as dominant explanations for regional differences in supporting a common EU approach to the pandemic. This underlines the relevance of distributive rationales not just across EU states, but also across subnational areas within an EU that is regularly confronted with collective crisis events.

Turning to papers which tend to focus more on identity drivers of discontent, this special issue presents three studies that deal with orientations towards national and EU institutions. Rodon and Kent’s (Citation2024) study investigates how spatial segregation of immigrants influences attitudes towards EU integration across a range of western European regions. In line with the prominent contact hypothesis, it finds that a higher share of migrant populations from eastern Europe correlates positively with EU support, but this effect turns negative as areas become more segregated. Working-class individuals in particular become more Eurosceptic in the context of high migration and segregation, suggesting that labour market competition only shapes Euroscepticism in local contexts that inhibit contact between natives and migrants. This suggests that both the regional concentration and distribution of immigrants are key to understanding EU attitudes.

Katsanidou and Mayne (Citation2024) focus on the interaction between economic and identity drivers of discontent related to both political institutions as well as actors and processes as potential mechanisms behind the expression of discontent. The article addresses an underexplored question derived from the scholarship on left-behind regions concerning how regional economic disparities moderate the established linkage between an individual's socio-economic standing and their propensity to endorse the European Union. They find no substantial link between subnational economic conditions and the relationship between education level and EU support. Cross-sectional analysis shows a positive correlation between regional GDP per capita and EU support regardless of education level, particularly after the Great Recession. Longitudinally, EU support correlates with decreasing regional unemployment but not with rising regional GDP per capita.

The paper by McKay, Jennings, and Stoker (Citation2024) deals with identity drivers of discontent in relation to political actors and processes as well as system performance and policy. McKay et al. investigate perceptions of geographic bias in government resource distribution across five European democracies (Britain, Croatia, France, Germany, Spain) using original survey and contextual data. Their findings indicate widespread belief in government bias towards wealthy areas and capitals, with rural areas also perceived by many as neglected. These perceptions are linked to individuals’ locations, distrust in government, populist attitudes, and left-wing leanings, but not directly to support for populist parties. The study highlights opportunities for mainstream left/liberal parties – not just populists – to capitalise on perceived biases, and provides important evidence for mechanisms explaining the structural divides in discontent between the more central/urban regions and peripheral areas.

Whereas many papers in this special issue refer to benchmarking drivers of discontent, two papers deal with it head on. Schraff and Pontusson (Citation2024) show that the structure of territorial inequalities influences the benchmarks used by people in regions falling behind. Hegewald (Citation2024) examines how place-based resentment relates to trust in local and national institutions, using original comparative survey data from nine EU countries. He finds that individuals with high levels of place-based resentment trust local institutions considerably more than national institutions. He concludes that a crisis of trust due to increasing regional inequality is largely restricted to national-level institutions, while systemic political support at the local level still seems intact, even in the face of strong place-based resentment.

The contributions to this special issue highlight the diverse relationship between economic, identity and benchmarking drivers of political discontent across various dimensions. They also demonstrate the different data and methods that can be used to examine this connection. Rodon and Kent's (Citation2024) investigation of spatial segregation and EU attitudes utilises spatial data from the D4I project and the European Social Survey. The integration of spatial and demographic data offers a detailed understanding of how the geographic distribution of migrant groups influences perceptions of the European Union (EU). The inclusion of the European Values Study and World Values Survey in Dellmuth's (Citation2024) research, along with extensive socioeconomic data from different regions worldwide highlights the benefit of merging large-scale survey data with economic indicators. This approach enables a comprehensive comparative analysis of political trust in various global political and economic contexts. The research conducted by Jennings, McKay and Stoker (Citation2024) utilises original survey data to gain first-hand insights into individuals’ perceptions of resource and attention distribution by governments in various regions. This data is valuable as it captures subjective perceptions, complementing objective measures used in other studies. Hegewald (Citation2024) utilises original comparative survey data across Europe to shed new light on the political consequences of place-based resentment, a measure that has so far been mainly collected in the US context. Eurobarometer survey data, as demonstrated by Vasilopoulou and Talving (Citation2024), is highly significant in comprehending public opinion trends in Europe. Their study shows how individual-level data can be used to analyse EU trust in different European regions. Furthermore, the utilisation of Eurobarometer and regional economic indicators, such as GDP per capita and unemployment rates, in studies like Katsanidou and Mayne's (Citation2024) emphasises the significance of economic data in situating individual attitudes within wider regional economic circumstances. Celli and Ferrante (Citation2024), as well as Schraff and Pontusson (Citation2024), shed light on the electoral expressions of political discontent, forwarding very different research designs on how to study the link between regional inequality and electoral discontent.

Just like the data sources, the methods used in this issue are diverse. They all contribute to our understanding of regional inequality and political discontent. Several papers use multilevel modelling to study this relationship. Multilevel modelling is commonly used because it can analyse data across multiple levels and time, effectively integrating individual attitudes with regional, national and temporal contexts. These studies utilise multilevel models to uncover intricate patterns of political behaviour influenced by personal experiences and broader socioeconomic conditions and time. Spatial analysis is crucial in Rodon and Kent's (Citation2024) research for understanding the segregation of migrants and its impact on EU attitudes. This choice of methodology highlights the significance of incorporating geographic factors in regional studies. Dellmuth's (Citation2024) work on comparative regional analysis presents an alternative approach. This method offers a wider perspective by comparing regions within and outside the EU, thereby revealing variations in the determinants of political trust across different regional political and economic backgrounds. The models developed by Vasilopoulou and Talving (Citation2024) highlight the importance of techniques that can capture the sometimes non-linear relationships found in regional studies. Their approach is crucial for uncovering patterns that could be hidden by linear models.

The utilisation of econometric analysis with counterfactual frameworks in studies such as the one conducted by Celli and Ferrante (Citation2024) showcases a strategy for establishing causality. This method is effective in understanding the causal relationships between economic events, such as economic downturns, and subsequent political behaviours. The study by Reinl, Beetsma and Nicoli (Citation2024) introduces conjoint experiments as a new approach in this research domain. The application of conjoint analysis demonstrates the efficacy of experimental methods in understanding intricate policy preferences, and how they vary over subnational contexts. This study examines the impact of technocratic solidarity and regional disparities on public opinion by presenting respondents with different policy options and measuring their preferences. This method is useful for understanding public attitudes towards EU-wide policies and identifying factors that influence support for these initiatives.

Discussion: lessons learned and avenues for future research

Taken together, this special issue advances the debate in a number of ways which also lend themselves to future research. First, absolute changes in local wealth seem to affect political discontent, but in a non-linear way (see Vasilopoulou and Talving, Citation2024). Relative declines in local wealth also seem to matter, but the benchmarks applied seem to vary across contexts (see Schraff and Pontusson, Citation2024). Therefore, we recommend that future research considers both linear and curvilinear relationships and how they differ. In addition, scholars should pay more attention to differences of measurement, e.g., absolute versus relative changes of inequality, as well as the type of benchmark they use in their theories and analyses, e.g., comparing inequality in a given region to its own trajectory, the richest region in the country or the broader world region to which it belongs.

Second, our special issue points to the different relationship patterns between inequality and discontent across regions both within Europe and across the world. For example, the relationship between economic inequality and discontent in Europe is different in other regions of the world (see Dellmuth, Citation2024). Regional heterogeneity in discontent appears to follow a surprisingly clear utilitarian logic that does not necessarily translate in regional contexts outside of the EU. This points to the deep economic integration of EU member states, which seems to have affected subnational political processes. However, there is also significant variation within Europe. For example, the effect of a change in manufacturing jobs is stronger in western European regions compared to eastern or peripheral regions, which suggests that transformative processes around the strongly regulated, high-wage and high-security manufacturing jobs characteristic of core and western European countries are central for our understanding of the geography of discontent. On the other hand, dynamics in manufacturing sectors play a smaller role in other countries, suggesting that different approaches to discontent (e.g., benchmarking or identity) might be more relevant in other non-western EU states (Schraff and Pontusson, Citation2024). Future research should examine the explanatory validity of the economic, identity and benchmarking theoretical frameworks in different regions of the world. It would also be important to investigate the ways in which the association between inequality and discontent differs within and between countries when taking into consideration different welfare states and models of capitalism. In this endeavour, we particularly recommend research designs that seek to uncover the casual relationships in different settings.

Third, regional inequalities are shaped by long-term economic trends, as many contributions to this special issue discuss, influencing disparities over time (see Ejrnæs and Jensen, Citation2024; Im, Citation2024; Katsanidou and Mayne, Citation2024; Schraff and Pontusson, Citation2024; Vasilopoulou and Talving, Citation2024). However, studies such as those by Celli and Ferrante et al. (Citation2024) and Reinl et al. (Citation2024) in this issue highlight the significant role of short-term macroeconomic and societal shocks in rapidly altering regional economic landscapes, which can exacerbate or mitigate existing inequalities. Whether focusing on long-term or short-term changes, most contributions in this issue support theories that emphasise psychological factors based on relative inequalities, group or identity-based heuristics and perceptions of place-based conflicts (see Hegewald, Citation2024; Rodon and Kent, Citation2024; and McKay et al., Citation2024 in this issue).

Finally, regional inequality can diminish support for national leaders and institutions, while local institutions seem more resilient in the face of grievances stemming from such inequality (see Hegewald, Citation2024). This raises important questions for future research: can local institutions help restore trust and interest in national politics and institutions? What strategies can policymakers use to mitigate political discontent linked to spatial inequality, and at what governmental level should these strategies be implemented – EU, national, regional or local? In response to these challenges, various European countries have implemented policies aimed at changing the social makeup of marginalised areas and decentralising public institutions. These include establishing local healthcare and police services and relocating educational programmes to reduce the distance to public services, thereby addressing the consequences of prolonged centralisation. In the United States and United Kingdom, concepts like ‘no place left behind’ and ‘levelling up’ reflect efforts to rejuvenate declining areas and enhance the wellbeing of their inhabitants (Hendrickson et al., Citation2018; Tomaney & Pike, Citation2021; Lloyd, Citation2021). Nonetheless, it is crucial to further investigate the effectiveness of these policies in reducing political discontent in neglected regions. Future research should focus on how well these interventions dampen political disillusionment and under what circumstances they can bolster democratic resilience.

Acknowledgements

This special issue originated from two workshops at Copenhagen Business School (CBS), Denmark, focusing on the link between inequality and Euroscepticism and regional inequality and political discontent in Europe, the first financed by the Inequality Platform and the second by the Carlsberg Foundation (grant CF22-0332). We are grateful for essential support from the funding bodies, workshop participants, CBS and its Department of International Economics, Government and Business. Dominik Schraff’s contribution was supported by an Ambizione grant from the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant number 186002). Special thanks to Jeremy Richardson and Berthold Rittberger, the Journal of European Public Policy's editors, for the support and guidance which made this special issue feasible.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Anders Ejrnæs

Anders Ejrnæs is a Professor with Special Responsibilities at the Department of Social Sciences and Business, Roskilde University, Denmark.

Mads Dagnis Jensen

Mads Dagnis Jensen is an Associate Professor at the Department of International Economics, Government and Business at Copenhagen Business School, Denmark.

Dominik Schraff

Dominik Schraff is an Associate Professor of political science at Aalborg University, Denmark.

Sofia Vasilopoulou

Sofia Vasilopoulou is Professor of European Politics at the Department of Europeanand International Studies, King’s College London.

Notes

2 Note that comparative survey datasets are often not representatively sampled at the regional level and/or lack sufficient sample sizes to provide valid and reliable estimates of subnational public opinion (see Lipps & Schraff, Citation2021b for strategies to remedy that using Eurobarometer). The European Social Survey provides relatively large samples and a more robust sampling strategy on the regional level. Nevertheless, the ESS descriptives presented in this introduction are still likely to be noisy estimates, especially for less populated regions.

3 The Standard Eurobarometer surveys, for example, are sampled on subnational demographics, but only with respect to gender and age.

References

- Adler, D., & Ansell, B. (2020). Housing and populism. West European Politics, 43(2), 344–365. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2019.1615322

- Beckfield, J. (2019). Unequal Europe: Regional integration and the rise of European inequality. Oxford University Press.

- Bell, A., & Jones, K. (2015). Explaining fixed effects: Random effects modeling of time-series cross-sectional and panel data. Political Science Research and Methods, 3(1), 133–153. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2014.7

- Benson, D., & Jordan, A. (2007). Understanding task allocation in the European Union: Exploring the value of federal theory. Journal of European Public Policy, 15(1), 78–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760701702215

- Beramendi, P. (2012). The political geography of inequality: Regions and redistribution. Cambridge University Press.

- Bertsou, E. (2019). Rethinking political distrust. European Political Science Review, 11(2), 213–230.

- Billig, M., & Tajfel, H. (1973). Social categorization and similarity in intergroup behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology, 3(1), 27–52.

- Bisgaard, M., Sønderskov, K. M., & Dinesen, P. T. (2016). Reconsidering the neighborhood effect: Does exposure to residential unemployment influence voters’ perceptions of the national economy? The Journal of Politics, 78(3), 719–732. https://doi.org/10.1086/685088

- Blom-Hansen, J. (2005). Principals, agents, and the implementation of EU cohesion policy. Journal of European Public Policy, 12(4), 624–648. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760500160136

- Bolet, D. (2021). Drinking alone: Local socio-cultural degradation and radical right support-the case of British pub closures. Comparative Political Studies, 54(9), 1653–1692.

- Bouvet, F., & Dall’erba, S. (2010). European regional structural funds: How large is the influence of politics on the allocation process? JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 48(3), 501–528. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2010.02062.x

- Broz, J. L., Frieden, J., & Weymouth, S. (2021). Populism in place: The economic geography of the globalization backlash. International Organization, 75(2), 464–494. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818320000314

- Carreras, M., Carreras, Y. I., & Bowler, S. (2019). Long-term economic distress, cultural backlash, and support for Brexit. Comparative Political Studies, 52(9), 1396–1424. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414019830714

- Celli, V., & Ferrante, C. (2024). The Italian payback effect: The causal impact of the great recession on political discontent. Journal of European Public Policy, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2024.2325642

- Charasz, P., & Vogler, J. P. (2021). Does EU funding improve local state capacity? Evidence from Polish municipalities European Union Politics, 22(3), 446–471. https://doi.org/10.1177/14651165211005847

- Colantone, I., & Stanig, P. (2018a). The trade origins of economic nationalism: Import competition and voting behavior in Western Europe. American Journal of Political Science, 62(4), 936–953.

- Colantone, I., & Stanig, P. (2018b). Global competition and Brexit. American Political Science Review, 112(2), 201–218. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055417000685

- Craig, S. C. (1980). The mobilization of political discontent. Political Behavior, 2(2), 189–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00989890

- Cramer, K. J. (2016). The politics of resentment: Rural consciousness in Wisconsin and the rise of Scott Walker. University of Chicago Press.

- Cremaschi, S., Rettl, P., Cappelluti, M., De Vries, C. E. (2022). Geographies of discontent: How public service deprivation increased far-right support in Italy.

- Daniele, G., & Geys, B. (2014). Public support for European fiscal integration in times of crisis. Journal of European Public Policy, 22(5), 650–670. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2014.988639

- De Lange, S., Van Der Brug, W., & Harteveld, E. (2023). Regional resentment in the Netherlands: A rural or peripheral phenomenon?. Regional Studies, 57(3), 403–415.

- Dellmuth, L. (2021). Is Europe good for you? EU spending and well-being. Bristol University Press.

- Dellmuth, L. (2024). Regional inequalities and political trust in a global context. Journal of European Public Policy, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2269207

- Dellmuth, L. M., & Stoffel, M. F. (2012). Distributive politics and intergovernmental transfers: The local allocation of European Union Structural Funds. European Union Politics, 13(3), 413–433. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116512440511

- de Vries, C. E. (2018). Euroscepticism and the future of European integration. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198793380.001.0001

- Dijkstra, L., Poelman, H., & Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2020). The geography of EU discontent. Regional Studies, 54(6), 737–753. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1654603

- Doucette, J. (2024). Parliamentary constraints and long-term development: Evidence from the duchy of württemberg. American Journal of Political Science, 68(1), 24–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12700

- Dür, A., Eckhardt, J., & Poletti, A. (2019). Global value chains, the anti-globalization backlash, and EU trade policy: A research agenda. Journal of European Public Policy, 27(6), 944–956. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1619802

- Ejrnæs, A., & Jensen, M. D. (2019). Divided but united: Explaining nested public support for European integration. West European Politics, 42(7), 1390–1419. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2019.1577632

- Ejrnæs, A., & Jensen, M. D. (2022). Go your own way: The pathways to exiting the European Union. Government and Opposition, 57(2), 253–275. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2020.37

- Ejrnæs, A., & Jensen, M. D. (2024). Regional manufacturing composition and political (dis)content in Europe. Journal of European Public Policy, 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2293213

- ESS Round 9: European Social Survey Round 9 Data. (2018). Data file edition 3.1. Sikt - Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research, Norway – Data Archive and distributor of ESS data for ESS ERIC. https://doi.org/10.21338/NSDESS9-2018.

- Fairbrother, M. (2014). Two multilevel modeling techniques for analyzing comparative longitudinal survey datasets. Political Science Research and Methods, 2(1), 119–140.

- Gidron, N., & Hall, P. A. (2020). Populism as a problem of social integration. Comparative Political Studies, 53(7), 1027–1059. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414019879947

- Giesselmann, M., & Schmidt-Catran, A. W. (2019). Getting the within estimator of cross-level interactions in multilevel models with pooled cross-sections: Why country dummies (sometimes) do not do the job. Sociological Methodology, 49(1), 190–219.

- Gray, M., & Barford, A. (2018). The depths of the cuts: The uneven geography of local government austerity. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 11(3), 541–563. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsy019

- Guilluy, C. (2019). Twilight of the elites: Prosperity, the periphery, and the future of France. Yale University Press.

- Haffert, L. (2022). The long-term effects of oppression: Prussia, political catholicism, and the alternative für deutschland. American Political Science Review, 116(2), 595–614. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421001040

- Haffert, L., Palmtag, T., & Schraff, D. (2024). When group appeals backfire: explaining the asymmetric effects of place-based appeals. British Journal of Political Science, forthcoming.

- Harteveld, E., Van Der Brug, W., De Lange, S., & Van Der Meer, T. (2022). Multiple roots of the populist radical right: Support for the Dutch PVV in cities and the countryside. European Journal of Political Research, 61(2), 440–461.

- Hegewald, S. (2024). Locality as a safe haven: Place-based resentment and political trust in local and national institutions. Journal of European Public Policy, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2291132

- Heidenreich, M., & Wunder, C. (2008). Patterns of regional inequality in the enlarged Europe. European Sociological Review, 24(1), 19–36. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcm031

- Hendrickson, C., Muro, M., & Galston, W. A. (2018). Countering the geography of discontent: Strategies for places left behind. Brookings.

- Hobolt, S. B. (2016). The Brexit vote: A divided nation, a divided continent. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(9), 1259–1277. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1225785

- Hobolt, S. B., & de Vries, C. (2016). Public support for European integration. Annual Review of Political Science, 19, 413–432.

- Hobolt, S. B., & Wratil, C. (2015). Public opinion and the crisis: The dynamics of support for the euro. Journal of European Public Policy, 22(2), 238–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2014.994022

- Hochschild, A. R. (2016). Strangers in their own land: Anger and mourning on the American right. The New Press.

- Huijsmans, T., Harteveld, E., van der Brug, W., & Lancee, B. (2021). Are cities ever more cosmopolitan? Studying trends in urban-rural divergence of cultural attitudes. Political Geography, 86, 102353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2021.102353

- Iammarino, S., Rodriguez-Pose, A., & Storper, M. (2019). Regional inequality in Europe: Evidence, theory and policy implications. Journal of Economic Geography, 19(2), 273–298. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lby021

- Im, Z. J. (2024). Paying the piper for the green transition? Perceptions of unfairness from regional employment declines in carbon-polluting industrial sectors. Journal of European Public Policy, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2288689

- Jacobs, N., & Munis, B. K. (2023). Place-based resentment in contemporary US elections: The individual sources of America’s urban-rural divide. Political Research Quarterly, 76(3), 1102–1118.

- Jennings, W., Stoker, G., & Twyman, J. (2016). The dimensions and impact of political discontent in Britain. Parliamentary Affairs, 69(4), 876–900. https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsv067

- Katsanidou, A., & Mayne, Q. (2024). Is there a geography of Euroscepticism among the winners and losers of globalization? Journal of European Public Policy, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2024.2317361

- Leibert, T., & Golinski, S. (2016). Peripheralisation: The missing link in dealing with demographic change? Comparative Population Studies, 41(3-4), 255–284. https://doi.org/10.12765/CPoS-2017-02.

- Lipps, J., & Schraff, D. (2021a). Regional inequality and institutional trust in Europe. European Journal of Political Research, 60(4), 892–913. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12430

- Lipps, J., & Schraff, D. (2021b). Estimating subnational preferences across the European Union. Political Science Research and Methods, 9(1), 197–205. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2019.38

- Lloyd, T. (2021). No place left behind: The commission on prosperity and community placemaking. Create Streets Foundation.

- MacKinnon, D., Kempton, L., O’Brien, P., Ormerod, E., Pike, A., & Tomaney, J. (2021). Reframing urban and regional ‘development’ for ‘left behind’ places. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 15, 39–56. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsab034

- Margalit, Y. (2011). Costly jobs: Trade-related layoffs, government compensation, and voting in U.S. Elections. American Political Science Review, 105(1), 166–188. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000305541000050X

- Martin, R., Gardiner, B., Pike, A., Sunley, P., & Tyler, P. (2021). Levelling up left behind places: The scale and nature of the economic and policy challenge. Routledge.

- Martin, G. J., & Webster, S. W. (2020). Does residential sorting explain geographic polarization? Political Science Research and Methods, 8(2), 215–231. http://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2018.44

- Mattinson, D. (2020). Beyond the Red Wall: Why Labour lost, how the Conservatives won and what will happen next? Biteback Publishing.

- Maxwell, R. (2020). Geographic divides and cosmopolitanism: Evidence from Switzerland. Comparative Political Studies, 53(13), 2061–2090.

- Mayne, Q., & Katsanidou, A. (2023). Subnational economic conditions and the changing geography of mass Euroscepticism: A longitudinal analysis. European Journal of Political Research, 62(3), 742–760. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12528

- McCann, P. (2020). Perceptions of regional inequality and the geography of discontent: Insights from the UK. Regional Studies, 54(2), 256–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1619928

- McKay, L., Jennings, W., & Stoker, G. (2021). Political trust in the ‘places that don’t matter.’. Frontiers in Political Science, 3, 31. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2021.642236

- McKay, L., Jennings, W., & Stoker, G. (2024). Understanding the geography of discontent: Perceptions of government’s biases against left-behind places. Journal of European Public Policy, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2277381

- Mcquarrie, M. (2017). The revolt of the Rust Belt: place and politics in the age of anger. The British Journal of Sociology, 68, S120–S152.

- Moretti, E. (2012). The new geography of jobs. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Munis, B. K. (2020). Us over here versus them over there … literally: Measuring place resentment in American politics. Political Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09660-9

- Nicoli, F., Walters, D. G., & Reinl, A. K. (2021). Not so far east? The impact of Central-Eastern European imports on the Brexit referendum. Journal of European Public Policy, 29(9), 1454–1473.

- Quaranta, M., & Martini, S. (2016). Does the economy really matter for satisfaction with democracy? Longitudinal and crosscountry evidence from the European Union. Electoral Studies, 42, 164–174.

- Reinl, A.-K., Beetsma, R., & Nicoli, F. (2024). Divided by borders, united in healthcare? Regional heterogeneities and technocratic solidarity during the Covid-19 pandemic. Journal of European Public Policy. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2024.231531

- Rodon, T., & Kent, J. (2024). Geographies of EU dissatisfaction: Does spatial segregation between natives and migrants erode the EU project? Journal of European Public Policy, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.2271504

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2018). The revenge of the places that don’t matter (and what to do about it). Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 11(1), 189–209. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsx024

- Rooduijn, M., De Lange, S. L., & Van Der Brug, W. (2014). A populist Zeitgeist? Programmatic contagion by populist parties in Western Europe. Party Politics, 20(4), 563–575.

- Schraff, D. (2019). Regional redistribution and Eurosceptic voting. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(1), 83–105.

- Schraff, D., & Pontusson, J. (2024). Falling behind whom? Economic geographies of right-wing populism in Europe. Journal of European Public Policy, https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.22786471

- Steenbergen, M. R., & Jones, B. S. (2002). Modeling multilevel data structures. American Journal of Political Science, 218–237.

- Steiner, N. D., & Harms, P. (2023). Trade shocks and the nationalist backlash in political attitudes: Panel data evidence from Great Britain. Journal of European Public Policy, 30(2), 271–290.

- Stiglitz, J. E., Sen, A. K., & Fitoussi, J. P. (2009). Report by the commission on the measurement of economic performance and social progress.

- Tajfel, H. (1974). Social identity and intergroup behaviour. Social Science Information, 13(2), 65–93.

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In M. A. Hogg & D. Abrams (Eds.), Intergroup relations: Essential readings (pp. 94–109). Psychology Press.

- Talving, L., & Vasilopoulou, S. (2021). Linking two levels of governance: Citizens’ trust in domestic and European institutions over time. Electoral Studies, 70, 102289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2021.102289

- Tomaney, J., & Pike, A. (2021). Levelling up: a progress report. Political Insight, 12(2), 22–25.

- Vasilopoulou, S. (2016). UK euroscepticism and the Brexit referendum. The Political Quarterly, 87(2), 219–227. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12258

- Vasilopoulou, S., & Talving, L. (2020). Poor versus rich countries: A gap in public attitudes towards fiscal solidarity in the EU. West European Politics, 43(4), 919–943. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2019.1641781

- Vasilopoulou, S., & Talving, L. (2024). Euroscepticism as a syndrome of stagnation? Regional inequality and trust in the EU. Journal of European Public Policy, https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2023.226489

- Wagner, A. (1890). Finanzwissenschaft. C.F. Winter.

- Walter, S. (2021). The backlash against globalization. Annual Review of Political Science, 24(1), 421–442. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-041719-102405