?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

A well-studied hypothesis in the political economy literature is that economic globalisation leads to the convergence of economic policies because of increasing international constraints. However, little is known about how parties adapt their policy positions during economic crises. This paper investigates parties’ policy shifts in economically harsh times. It highlights the important distinction between long-term trends (e.g., economic integration) and relatively short-term economic fluctuations when studying party competition. During economic downturns parties have an incentive to intensify the debate on economic policies and emphasise their distinct policy positions. In other words, parties strategically position themselves on salient issues. The empirical analysis combines party manifesto data with macro-economic indicators and survey data from 28 European countries between 1980 and 2021. The findings show that party polarisation increases when the economy is in decline, and positions converge during economic recovery. Further analyses explore the mechanism and reveal an indirect effect: parties adjust their policy positions in reaction to changing voter priorities and grievances in times of economic distress. Overall, the article contributes to a larger literature on party competition and political responsiveness by showing that external shocks, such as economic crises, influence the diversity of political offers among established parties.

In the late 2000s, an economic crisis quickly spread from the United States to Europe, causing public debt to rise to unsustainable levels in many countries. With severe budget cuts, rising levels of unemployment and increasing economic insecurity, macro-economic and welfare policies were again the dominant topics of election campaigns in many European countries. At the same time, the choices available to political leaders in the economic domain seemed more restricted than ever. The years after the crisis have brought some economic recovery in many countries, however with the pandemic, and especially since the beginning of the war in Ukraine, worries about the state of national economies are increasing, and there are fears of a new recession. How do political parties react to such dramatic changes in economic prospects?

Predating the great recession that started in 2008, a large literature has studied party competition and economic policy in the context of growing external constraints. Many studies investigated the hypothesis that economic globalisation would lead to the convergence of national politics. There was evidence of policy convergence, but also of persisting differences between left and right parties, depending on national conditions and political institutions (e.g., Allan & Scruggs, Citation2004; Berger, Citation2000; Boix, Citation2000; Garrett, Citation1998). A second strand of (pre-crisis) research even argued that the economy – or for that matter, the ‘left-right’ ideological dimension – had lost its importance altogether, while cultural issues, such as immigration, had become the defining features of political conflict in advanced democracies (e.g., Hellwig, Citation2008a; Kriesi et al., Citation2008). More recent research, however, somewhat contradicts this view by showing that public salience of economic issues increases in times of economic distress (Singer, Citation2011, Citation2013; Traber et al., Citation2018), and that parties pay more attention to economic issues when the economy is in decline (Spoon & Williams, Citation2021; Williams et al., Citation2016). How can we reconcile these seemingly contradictory findings? And what are the implications in terms of policy positions when parties put more emphasis on economic issues?

This paper investigates parties’ policy shifts in economically harsh times. I argue that it is important to distinguish between long-term trends (i.e., economic integration) and relatively short-term economic fluctuations. During economic downturns – when economic insecurities become more widespread – parties have an incentive to intensify the debate on economic policies and emphasise their distinct policy positions. In other words, parties strategically position themselves on issues that are salient and take more extreme positions than in times when these issues are less important. They signal a distinct ‘brand’ to their voters; a party image that should clearly distinguish them from those of other parties. Testing this argument, the first part of the analysis shows that party positions polarise when the economy is in decline and de-polarise in prosperous times. In the second part, I investigate the proposed mechanism that party competition around an issue increases because of the issue's greater political salience, i.e., because voters care about this issue. The analysis is based on party-position data for 27 European countries between 1980 and 2021 (Comparative Manifesto Project), combined with economic indicators (OECD, ILO) and pooled Eurobarometer survey data (2002–2021).

The findings have important implications for theories of comparative political economy and party competition. First, reconciling two sometimes contradictory perspectives, they show that despite convergence of party positions on economic issues in the long run, party systems polarise during (short-term) economic downturns, and when economic issues become publicly salient. External economic shocks thus have important consequences for the parties’ policy offerings, and ultimately for the diversity of positions the voters can choose from. The results also contribute to the debate regarding the reasons behind the decline of mainstream parties in Europe. If parties are able to take more distinct policy positions in reaction to external economic shocks (and the voters’ reactions to those shocks), then the argument that mainstream party loss is predominantly a consequence of policy convergence, lack of policy offerings, or even cartelisation, is not entirely justified.

Revisiting the convergence hypothesis

Since the 1990s a large literature has addressed the claim that economic globalisation would lead to the convergence of economic policies and, consequently, of the parties’ ideological positions on economic issues. First, the political economy literature has focused on governments and economic policies, second, party competition research has been concerned with parties’ ideological positions and their strategic behaviour. In general, the expectation was that with the growing mobility of capital, governments would become more responsive to the interests of capital, in order not to lose national competitiveness and investment. Further, it was argued that the global spread of neoliberal doctrines would add ideological constraints on state intervention in the economy. Accordingly, with the dominance of neoliberal policymaking, it would not matter anymore whether right-wing or left-wing parties were in government (Berger, Citation2000).Footnote1 The rather pessimistic prediction was that economic interdependence would increasingly limit the political alternatives available to voters, with severe consequences for representative democracy (Blyth & Katz, Citation2005; Hellwig, Citation2008b; Katz & Mair, Citation2009; Mair, Citation2013). More recently, a similar argument was made with regard to financialisation of the economy (e.g., Witko, Citation2016).

Empirical research has so far provided mixed results for the convergence hypothesis. Quite contrary to the claims that globalisation would lead to an erosion of national politics, earlier studies – focusing on policy outputs or economic outcomes – found a continuing, albeit limited, importance of party ideology for the choice of economic and welfare policies (e.g., Allan & Scruggs, Citation2004; Boix, Citation2000; Garrett, Citation1998). More recent studies often follow an ‘interactive’ approach to partisan politics. They find that contextual aspects – such as the salience of the economic dimension and welfare state issues, or the consequences of globalisation for the national economy – condition the relationship between government partisanship and welfare policy (Engler, Citation2021; Hillen, Citation2023; Jakobsson & Kumlin, Citation2017; Schmitt & Zohlnhöfer, Citation2019; Steiner & Martin, Citation2012).

In contrast, research on economic party positions showed an overall de-polarising trend in a number of single-country studies focusing on the United Kingdom (Adams et al., Citation2012b; Evans & Tilley, Citation2017), the Netherlands (Adams et al., Citation2012a) and Denmark (Arndt, Citation2016).Footnote2 Existing evidence from comparative studies likewise points to either constant or declining levels of economic policy polarisation in European countries since the 1970s (Fenzl, Citation2018; Karreth et al., Citation2013; Nanou & Dorussen, Citation2013; Rehm & Reilly, Citation2010) – a development that is related to lower turnout and growing success of non-mainstream parties (Hübscher et al., Citation2023; Spoon & Klüver, Citation2019; Steiner & Martin, Citation2012; Tilley & Evans, Citation2017).

Broadly speaking, this first body of research argues that policy convergence is caused by external constraints: globalisation and financialisation of the economy. A second perspective adds an additional element by focusing on the linkages between voters and parties. While it may be the case that external constraints restrict the available policy options, parties still have to be responsive to their voters in order to win elections (e.g., Kitschelt, Citation2000a, Citation2000b). Since parties cannot offer distinct choices to their voters anymore, they shift their attention to other topics, which allows them to take clearly distinguishable policy positions. Thus, parties are expected to respond to contextual and structural changes by ‘realigning’ on a second, more salient, issue dimension (Kitschelt, Citation1994; Kriesi et al., Citation2008). In fact, many studies have put forward the argument that economic issues – or more generally, the ‘left-right’ ideological dimension – have lost their importance for party choice, while the salience of cultural issues, such as immigration, has increased in many advanced industrial societies since the last decades of the twentieth century (Kitschelt, Citation1994; Hellwig, Citation2008a, Citation2008b, Citation2014; Kriesi et al., Citation2008; Bornschier, Citation2010; De Vries, Citation2018; Hooghe & Marks, Citation2018; Norris & Inglehart, Citation2019; Ford & Jennings, Citation2020; Dassonneville et al., Citation2024).Footnote3 A number of long-term analyses support this argument by showing a declining role of economic issues in party agendas (e.g., Arndt, Citation2016; Green-Pedersen, Citation2019; Ward et al., Citation2015).

In sum, contrary to research focusing on external policy constraints, the second strand of literature provides a broader view of political competition by specifically taking into account the importance of party-voter linkages. However, this view somewhat neglects economic issue competition and does not make clear predictions about parties’ positions with regard to the economy. It simply states that economic issues are not central to political campaigns anymore.Footnote4

Long-term vs. short-term economic changes

Besides the long-term changes in the economic environment due to globalisation, the financial and economic crisis quite possibly represents a turning point: what are the consequences for party competition if the economy suddenly becomes the most important issue for voters, in other words, if there are sudden changes in the economic context that possibly lead to grievances among the public (Kriesi et al., Citation2020)?

Following the salience or ‘issue competition’ theory of elections, parties’ strategic decision on which issues to focus in their campaign is as crucial for their success as their specific policy positions. A large body of research has shown that in addition to their traditional issue profile – the issues they ‘own’ – parties also highlight issues that are publicly salient at the time of a specific election campaign (Ansolabehere & Iyengar, Citation1994; Budge & Farlie, Citation1983; Carmines & Stimson, Citation1986; Green-Pedersen, Citation2007; Green-Pedersen & Mortensen, Citation2015; Kristensen et al., Citation2023; Petrocik, Citation1996; Schattschneider, Citation1960; Wagner & Meyer, Citation2014). However, while the issue competition perspective has brought important insights into party competition beyond the spatial model, it has only recently started to empirically investigate the relationship between the economic context and party agendas. Analysing parties’ emphases on economic issues, Williams et al. (Citation2016) show that parties indeed respond to changes in the economic context by paying more attention to the economy when conditions are poor. Similarly, Traber et al. (Citation2020) find that prime ministers have addressed economic issues more extensively in their speeches during the economic crisis in Europe (see as well Borghetto & Russo, Citation2018). These results support the more general issue competition argument that parties need to respond to the salient issues of a given time (Ansolabehere & Iyengar, Citation1994; Green-Pedersen & Mortensen, Citation2010; Wagner & Meyer, Citation2014), or, in other words, to the issues voters care about (Klüver & Sagarzazu, Citation2016; Klüver & Spoon, Citation2016; Spoon & Williams, Citation2021).

It appears that parties respond to short-term fluctuations in the economic context by increasingly addressing economic issues when the economy is in bad shape, and decreasing issue emphasis in prosperous times. However, existing research has so far provided little information about the policy content of these economic messages. Do all parties express the same policy position? In other words, do they converge on a common policy position and just repeat the message more often? Or do parties reinforce their earlier ideological positions, and drift apart? According to the convergence hypothesis, which focuses on policy constraints caused by economic globalisation, we would expect the first scenario: due to their decreasing leeway in choosing macroeconomic policies, parties will increase the economic message (i.e., emphasise economic issues) but without changing the policy content. However, such a perspective neglects the party-voter linkages: parties have to be responsive to their voters in order to gain votes. In economically harsh times, voters care more about economic issues economic grievances are more widespread, and even those who are not directly affected are likely to fear future consequences. In addition, economic issues are more frequently discussed in the news and public debate, which increases public awareness and knowledge about the current economic conditions. Thus, voters are likely to have more distinct preferences about economic and welfare issues than in more prosperous times, and to select candidates and parties according to their respective policy positions (Krosnick & Kinder, Citation1990; Miller & Krosnick, Citation2000).

Given the change in voters’ demands, parties have an incentive to present a distinct alternative to other parties in their campaigns, causing party polarisation on the economic policy dimension during a recession. This argument is in line with a more general proposition in the party competition and responsiveness literature that parties pay more attention to public opinion and have a strategic incentive to express more extreme policy positions when public salience of an issue increases (Adams et al., Citation2005; Soroka, Citation2006; Soroka & Christopher, Citation2010). Salient issues structure the political process: people care about these issues, and their preferences regarding the salient policy domain are likely to influence party support and voting behaviour (Franklin & Wlezien, Citation1997; Miller & Krosnick, Citation2000). Parties will anticipate the voters’ increased awareness by focusing their attention on these issues, and by taking clear positions, which reinforces competition in this domain.

Indeed, research about the consequences of the economic crisis has provided evidence for party polarisation on the left-right policy dimension in Southern Europe (Conti et al., Citation2018), and for position-shifts of government parties (Calca & Gross, Citation2019) and Social Democratic parties (Bremer, Citation2018). In addition, the economic crisis has brought back distinct left and rightpartisan approaches to social spending (Savage, Citation2019). It is, however, important to note that this perspective with a focus on short-term economic decline does not contradict a long-term development of policy convergence, but rather presents a refinement of the existing argument. Combining the constraint- and the saliency-argument, we can distinguish between two types of economic change: the long-term trends of economic globalisation, and short-term changes in the national economic situation. Both have different effects: while the former puts more restrictions on the parties’ choice of economic policies, the latter increases the importance of economic issues among the voters and leads to increasing demand for specific policy solutions. So, parallel to the long-term trend of policy convergence, which leads to an overall more narrow policy space in the economic domain, we can expect short-term polarisation of parties’ offerings in their election campaigns in times when voters particularly care about the economic situation.

Economic downturns will lead to heightened attention to economic issues among the public, either because economic issues are more present in the news or because the voters are directly affected by the consequences of negative economic change. We can assume that if people are worried about the economy they also expect some sort of political reaction. However, not all citizens will expect the same: some might be worried about their investments and stocks, others might be worried about an insecure job situation, or fear a loss of income. An increase in salience thus not necessarily lead to changing political preferences, but existing preferences become more important for the political process.Footnote5 Parties react to these demands by positioning themselves more clearly on the economic dimension, with the result that party positions become more polarised.

The following analyses test these arguments in two steps: the first part looks at the parallel processes of long-term convergence and short-term fluctuations related to changes in the national economic situation, and the second part investigates the mechanism.

Data and measures

The analysis is based on data from all 27 European Union countries between 1980 and 2021: Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, as well as the United Kingdom. The dataset combines measures for individual parties’ economic positions from party manifestos, macro-economic indicators from different sources, and public opinion data collected in the Eurobarometer surveys. It includes 239 elections over a 42-year time span (see Table 1 in the appendix for an overview).

Dependent variable

To measure party polarisation, I calculate each party's distance to the average economic position in a given election year. The measure of economic party positions is based on coded party programmes (Volkens et al., Citation2021). In the CMP, manifestos are first split into so-called ‘quasi-sentences’, and each sentence is coded into a specific issue category. To measure the parties’ economic issue positions, I use all available categories related to topics that consider the degree of state involvement in the economy (including positions regarding the welfare state; see for the list of CMP categories).Footnote6 The party i's issue position at election t is computed as the share of sentences in the party manifesto that express support for demand-side-oriented policies (strong role of the state in the economy), minus the share of sentences expressing support for market-oriented policies (weak role of the state):

(1)

(1) where N is the total number of sentences (allocated codes) in that party manifesto.Footnote7

Table 1. Measurement of state-market ideological dimension.

The dependent variable is the distance between an individual party and the weighted party system average ():

(2)

(2)

(3)

(3) where n is the number of parties present in this election. The average is weighted by seat share wit; thus, a party with no seats in parliament is excluded from the calculation of the system average position.Footnote8

One characteristic of this party-level measure of polarisation is its sensitivity to the number and type of parties at a specific election. First, if the number of parties in a party system is very low, then distances might vary more strongly from one election to another. Therefore, I include a control variable for the effective number of parties (based on a formula suggested by Laakso and Taagepera (Citation1979)), to take into account that distances might change because of a different number of competing parties.

Second, a more substantial objection to this type of measure (but also to aggregate polarisation measures) is that the distance between a party and the party system average might increase not because a party shifted its own position, but because of the presence of an extreme party. Entrance of more extreme or ‘challenger’ parties is more likely in times of economic crisis (Hernández and Kriesi, Citation2016; Hobolt & Tilley, Citation2016). To prevent that the measure for party-level polarisation is influenced by the entrance of extreme parties – instead of the respective parties’ position shifts – I take several steps: First, the party system average is weighted by seat share. Extreme parties are less likely to have a large seat share and their influence on the measure of average position is thus lower. Second, I include a variable for party age in the regression models, measured by the number of election campaigns a party was present since 1945.Footnote9 Finally, the analyses are based on a restricted sample, including only parties with at least one seat in parliament and that were present in at least two consecutive election campaigns.Footnote10

Independent variables: economic context and public opinion

Change in the economic conditions is measured by annual GDP growth (OECD, 2023, and World Bank 2023Footnote11 and yearly change in the unemployment rate (ILO, 2022).Footnote12 The measure for the unemployment rate is based on a definition by the ILO, and calculates ‘the number of unemployed persons as a percentage of the total number of persons in the labour force’.Footnote13 In the analyses, the measures are included with a time lag, referring to the economic situation in the year before the elections took place. Because elections take place at different times of the year, both measures for the economic situation are calculated as a weighted mean of the 12 months previous to the election date.Footnote14

The public opinion measures are based on a pooled dataset of 39 Eurobarometer surveys between 2002 and 2021 (European Commission, 2022).Footnote15 I use two measures for the salience of the economy: one for sociotropic salience, and one for egocentric salience.Footnote16 Eurobarometer surveys are fielded several times a year. Since 2002, respondents have been asked twice each year (usually in spring and autumn) to give their opinion about the ‘most important issues facing the country’ at the time. The survey provides 15 answer categories, and asks the respondents to choose up to two.Footnote17 The measure for sociotropic salience of the economy is computed as the share of respondents who thought the economic situation was the most important issue at a specific election. The measure for egocentric salience is a combination of two questions in the surveys: ‘What are your expectations for the year to come (the next twelve months): will [country] be better, worse or the same, when it comes to the financial situation of your household?’ and ‘ … when it comes to your personal job situation?’. Egocentric salience is measured by the share of respondents who expected their financial situation as well as their job situation to be worse in the coming year. Both salience measures again are a weighted mean of twelve months preceding the election date.

The data has a multi-level structure: parties are nested in elections and countries. Therefore I use a multi-level specification in the regression models, which includes random intercepts for country-elections (Clark & Linzer, Citation2015).

Results: economic context and party polarisation

The empirical analysis proceeds in two parts: In the first part, I examine the relationship between changes in the economic context and party polarisation. The second part investigates the mechanism of why economic downturns should lead to party polarisation.

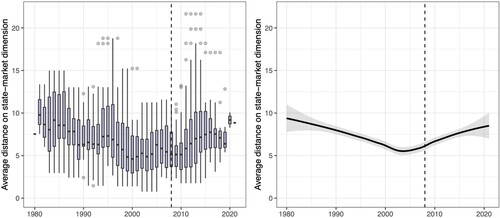

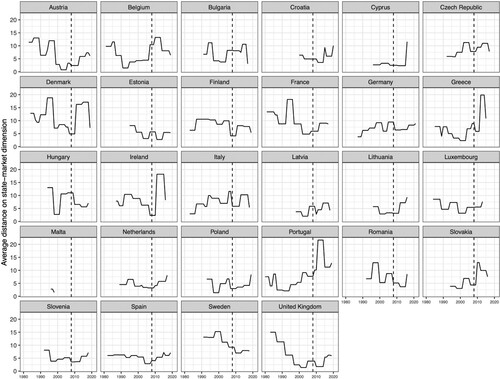

shows the distribution of the parties’ average distance to the system mean per country/election yearFootnote18 since the 1980s (boxplots and loess curve). The figure includes parties with at least one seat in parliament.Footnote19 On average, the distance in parties’ economic positions converged during the 1980s and 1990s, reaching a low around 2000. Up to this point, gives clear evidence for the convergence hypothesis. However, in the early twentieth-century party polarisation increased again, and especially so after the beginning of the financial and economic crisis (indicated by the dashed vertical line). The last two data points in (left panel) show the average distance in the years 2020 and 2021. Polarisation seems higher compared to the pre-pandemic years; however, we should be cautious to draw general conclusions from this data because it is based on only two elections (Croatia in 2020 and Germany in 2021).

Turning to individual countries, shows that party convergence until the mid-2000s is particularly strong in Austria, Denmark, France, Hungary Sweden and the UK, but almost nonexistent in other countries. By contrast, we find a polarising trend in the majority of countries since the early 2000s, which is more pronounced since the beginning of the financial crisis in 2008. There is a sharp increase in the average party distances in two countries strongly hit by the crisis: Ireland and Portugal. In Greece and Italy, parties had already become more polarised in the mid-2000s. In Spain, due to the dominant two-party system, the distances remain fairly constant with only a small change after 2008. This descriptive evidence is in line with the convergence hypothesis but also indicates a possible turning point after the beginning of the financial crisis. More data is needed to evaluate whether we will see similar trends as a consequence of the Covid-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine.

presents the results of a number of multilevel models with random intercepts for election-years. The dependent variable in Models 1–3 is the parties’ distance to the average economic party position at a given election. In addition to the control variables described above, the models include a variable for the parties’ seat share, and the parties’ distance to the mean at the previous election. We can interpret the coefficients as the effect on position distance at election t, independently of the previous distance.

Table 2. Regression results: economic context and party polarisation 1980–2021.

The results show that both economic indicators – change in unemployment and GDP growth – influence party polarisation: The parties’ distance increases with lower GDP growth, and with larger positive changes in unemployment levels. To give an example: if GDP growth is 2.5% in one election year and −2.5% in another (−5 percentage points) the results predict an average 1.25 unit increase in party distance (Model 1). This might seem like a small change, but it adds up with a prolonged economic downturn over several years. Conversely, party systems converge again when the economy recovers. Similarly, for a difference in unemployment change from −2 percentage points at one election to +2 percentage points at another election, Model 2 predicts a change in average distance from the party mean of about 2 units. GDP growth and change in unemployment are of course closely related (Pearson's R: −0.55). If we include both indicators in the same model, the coefficients are substantially smaller, and unemployment loses statistical significance.

The results that are shown in the last two columns of point to an interesting contrast to these main findings. In column 4, the dependent variable is overall left-right positions without economic issues.Footnote20 Accordingly, average position and lagged distance are measured in reference to the non-economic left-right scale. It appears that polarisation of non-economic issues also increases when economic conditions are worsening (albeit only significant at 10% level). This is in line with research on right-wing populism (e.g., Engler & Weisstanner, Citation2021; Stoetzer et al., Citation2023), and merits further investigation in future studies. Finally, the last column in includes as a dependent variable the distance to the average welfare position.Footnote21 There seems to be no polarising effect of economic context on welfare state positions, a finding that supports recent research on austerity politics (e.g., Bremer, Citation2023; Hübscher et al., Citation2023).

Arguably, a measure that is based on a share of sentences within manifestos in relation to all issues picks up the salience of the topic. In other words, polarisation increase might be an artefact of the data – because parties talk longer about an issue the positions are measured as more pronounced. This effect is difficult to separate from the theoretical argument that the salience of a topic has an effect on polarisation; in other words, that parties shift their positions on topical issues. While the two cannot be distinguished entirely, Appendix B shows the results of two robustness tests. First, I calculated a different version of the dependent variable, using the total share of economic issues (pro-state and pro-market) as a baseline (Appendix B, Table 6). The results are robust for separate effects of unemployment and GDP growth (Model 1 and Model 2). Second, I include the salience of issues – measured as the total number of economic issues (non-economic left-right and welfare respectively) as a control variable (see Appendix B, Table 8). The results for economic polarisation are almost identical, however, the negativ effect of GDP growth on non-economic left-right polarisation disappears.

In sum, these findings support the hypothesis that parties take more polarised economic positions in times of economic hardship, and converge as the economy recovers. I explore the mechanisms of why parties polarise in the next step.

The role of public opinion

During economic downturns, the economy is more frequently discussed in the news, and some voters are directly affected or fear negative consequences for their personal lives in the near future. One possibility to observe the salience of an issue among the public is by looking at the issues voters consider to be most important (sociotropic salience). In addition, the citizens’ perception of their own economic situation is likely to become more pessimistic. In other words, the egocentric salience of the issue might increase as well.

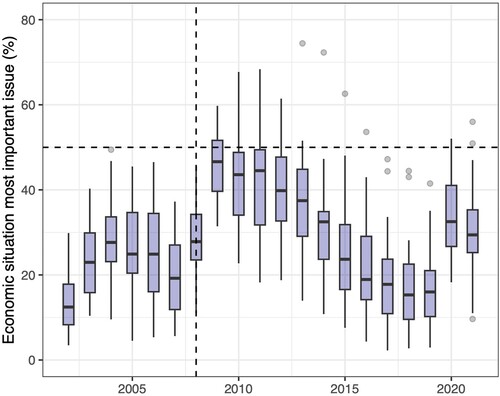

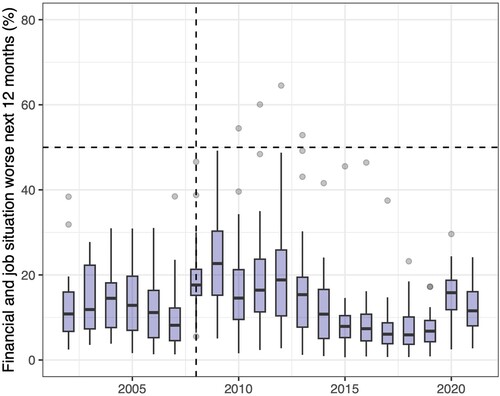

and show the changes in the sociotropic and egocentric salience of the economy since the early 2000s. depicts the average share of respondents in the 27 European countries who thought the economy was the most important issue at the time. The average expectations regarding the citizen's personal economic situation are shown in . Again, the figures include a dashed line in 2008. Sociotropic salience of economic issues increased dramatically after the beginning of the financial crisis. In the first half year of 2009 on average 49 per cent of citizens in European countries considered the state of the economy the most important issue currently facing their country. In comparison, only 17 per cent had mentioned the economy as being most important in late 2007. The salience of the economy remains high throughout the European debt crisis and drops below 30 per cent in mid-2014. Separate graphs for countries (see in the appendix) reveal important differences between economic contexts. After a first peak in 2009, the sociotropic salience of economic issues decreased quickly in Belgium, Germany, Luxemburg and Sweden, but remained highest in Greece, Spain, Portugal and Italy – the Southern European countries that experienced the most severe debt crises – as well as in many Eastern European countries. The beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic marks another sharp – in some countries dramatic – increase in the sociotropic salience of the economy.

Egocentric economic salience follows a similar trend. combines two questions about the personal economic outlook (job situation and financial situation of household) – and plots the share of citizens who were worried about the deterioration of both in the coming year. Obviously, the shares are lower compared to the general salience of the economy, but they show a strong rise after the beginning of the financial crisis, higher shares during the European debt crisis in many countries, and again a spike in 2020. Economic grievances are particularly widespread in Greece, Portugal, Cyprus and Hungary (see Figure 3 in the appendix).

Parties are likely to take this public demand into account when drafting their electoral campaigns. In a time when the economy dominates the news, it is very risky for political elites to ignore economic policy. They have to take a clear stance, and discuss their solutions and policy recommendations, addressing strategies that would get the economy back on track and mitigate the negative consequences for citizens. In other words, parties react to economic downturns because the public sends a strong signal that something needs to be done. The postulated effect thus presumably is indirect: Parties react because they observe (or anticipate) voters’ reaction to changing economic conditions.

To test this argument, I estimate the same models as before but introduce the salience measures in a second step. Unfortunately, public opinion data is not available for years before 2002 – still, it is possible to examine a time span of 20 years at the beginning of the twenty-first century. The models shown in include the same control variables as in the previous analyses: a party's distance to the party mean at election t-1, its seat share in the national parliament, party age, and the effective number of parties.

Table 3. Regression results: public opinion and party polarisation 2002–2021.

To analyse the postulated mechanisms, I introduce the two salience measures in a step-wise procedure. Models 1 and 4 replicate the results from the longer time series. Since GDP growth and unemployment are even more highly correlated in recent years, they are included separately. Models 2 and 5 introduce the sociotropic salience, and Models 3 and 6 the individual grievances. The results in reveal that the coefficient of both, GDP growth and unemployment change is substantially reduced and not significant when the salience of the economy is taken into account. Thus, the findings point to an indirect effect of the economic context on party polarisation. Apparently, parties adjust their positions as a response to economic change because they observe changes in public perceptions. So, ultimately what drives their strategies is an increasing demand for specific solutions in times of economic distress. When issue salience increases, party competition on the respective issue dimension intensifies. Parties take distinct positions regarding these issues, thereby increasing the political choice in the party system. After recovery, the public's interest decreases again and the parties’ economic policy positions become less distinct.

An important caveat to these conclusions is the possibility of reciprocal effects between sociotropic salience and the parties’ campaign. In other words, voters could pay more attention to the economy and think the economy is an important issue because parties start focusing on the economy in their public communication even before the actual election campaign. We cannot rule out this reciprocal effect with the data at hand because party positions are only measured at the time of the election. However, it is arguably much less likely that citizens’ worries about their personal economic situation should be influenced more by party discourse than the actual economic situation.

Conclusion

What are the consequences of a changing economy for party competition? A well-studied proposition in the political economy literature is that economic globalisation leads to the convergence of economic policies, since the room of manoeuvre of national policy-makers becomes increasingly constrained (Berger, Citation2000). Along these lines, a large body of research has examined the changing structure of the political space, concluding that the economic left-right ideological dimension has become less important, and a second – ‘cultural’ – line of conflict increasingly dominates political competition in postindustrial societies (Hellwig, Citation2008a; Kitschelt, Citation1994; Kriesi et al., Citation2008).

Against this background, recent studies find that public salience of economic issues has increased dramatically since the beginning of the financial and economic crisis in 2008 (e.g., Singer, Citation2013; Traber et al., Citation2018). At the same time, research on party attention has shown that parties react to short-term fluctuations in the economy by putting more emphasis on economic issues during downturns and talking less about the economy during prosperous times (Williams et al., Citation2016). How parties adapt their policy positions has, however, received surprisingly little attention.

This study contributes to a growing literature on party competition during and after the economic crisis in Europe (e.g., Bremer, Citation2018; Calca & Gross, Citation2019; Nicolò Conti, Swen Hutter and Kyriaki Nanou, 2018; Savage, Citation2019) but includes a longer time frame. This allows us to reconcile two different and sometimes contradictory perspectives in existing research. Specifically, distinguishing between long-term and short-term economic changes, I argue that over the long run, external constraints lead to the convergence of parties’ economic policy positions. Short-term recessions or economic shocks, however, increase the salience of economic issues among the public and therefore the pressure on parties to react and adapt their policy positions on the salient policy dimension. The findings of the first analysis show that polarisation of party positions increases when the economy is in decline. Testing the mechanism, the second analysis combines economic context data with public opinion data and provides evidence for an indirect effect: Parties react to changes in the economic context because economic issues are of high public salience (sociotropic salience), and voters are worried about their financial situation (egocentric salience). Unfortunately, the party manifesto data only allows us to measure position shifts between two election points, and we cannot rule out reciprocal effects between party campaigns and public opinion in the inter-election period. While it is less likely that individual grievances are affected by party politics, problem perception might be. We have included different measures of economic salience as well as lagged variables to address this issue in this study. Future studies could look into other party documents, such as press releases, to trace position shifts more closely.

In sum, by investigating the role of context effects, as well as public opinion on economic policy positions, the findings of this study speak to a broad literature on party competition, political representation and public policy. They indicate that European parties, including mainstream parties, are indeed responsive to changes in the economic context. Even if the range of economic policies might have become narrower in comparison to the 1980s – as the convergence hypothesis suggests – parties still adjust their policy positions in reaction to changing voter priorities, thereby increasing political choice along the salient policy dimension.

External shocks, such as economic crises, influence the diversity of political offers. Much has been written about the surge of new parties after the crisis, and the alleged inflexibility of established parties to react to voters’ demands. The findings of this study go against the idea that mainstream politics is all the same, and that only challenger parties are willing (or able) to swiftly react to contextual changes. Against this view, the findings show that the economic crisis has led to a revitalisation of economic policy competition among established parties as well. Finally, this research is in line with recent studies that emphasise the persistent role of economic policy in political competition (e.g., Dancygier & Margalit, Citation2020), despite the recent focus on cultural and immigration-related topics in research and public discourse.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (191.8 KB)Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of this paper were presented at APSA general conference 2017, at the workshop ‘Unchallenged democracy? The political legacy of the economic crisis in Europe’, University of York, 2018, and at various research workshops (University of Zurich, 2017, University of Konstanz, 2018, University of Basel, 2020, University of Geneva, 2021). I thank the participants of these conferences and workshops for their comments. I am particularly grateful to Tarik Abou-Chadi, Macarena Ares, Simon Bornschier, Christian Breunig, Céline Colombo, Marina Costa Lobo, Fabio Ellger, Julian Garritzmann, Theresa Gessler, Nathalie Giger, Lukas Haffert, Silja Häusermann, Ignacio Jurado, Herbert Kitschelt, Alexander Kuo, Thomas Kurer, Rosa Navarrete, Andrew Pickering, Thomas Plümper, Philip Rathgeb, Ari Ray, Thomas Sattler, Judith Spirig, Christopher Wlezien and the three anonymous reviewers for very helpful comments and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Denise Traber

Denise Traber is an assistant professor of political science at the University of Basel. Her research focuses on public opinion, political behaviour and party competition in the context of societal and economic changes.

Notes

1 The changing balance of power between capital and labour was expected to more severely affect social democracy, and consequently the literature discussed the convergence of party policies mostly in the context of an alleged decline of social democratic parties (Kitschelt, Citation1994; Huber & Stephens, Citation2001).

2 Bornschier (Citation2015), however, documents a polarising trend for Switzerland. Likewise, more recent studies show that British elite polarization has increased again since the financial crisis (Cohen & Cohen, Citation2021; Caldwell, Citation2023).

3 While this research has taken a comparative view and mostly focused on Europe, more recent analyses of the 2016 US-elections make a similar argument (e.g., Donovan & Bowler, Citation2018; Mutz, Citation2018).

4 But see Häusermann and Kriesi (Citation2015) for a more recent analysis of the interaction of economic and cultural issues in the voter's choice of parties; and Savage (Citation2019) for a recent study of social spending after the Great Recession.

5 See Mutz (Citation2018) for a similar argument regarding immigration and trade preferences.

6 See the CMP codebook for a more detailed description of the substantive issue codes: https://manifesto-project.wzb.eu/down/data/2021a/codebooks/codebook MPDataset MPDS2021a.pdf.

7 As a robustness test I will also use a measure with the total number of sentences concerning economic issues as the baseline (see results section).

8 The results change only marginally when the party mean is weighted by vote share.

9 Note that the party might be older; the CMP data set starts in 1945.

10 To identify the individual parties, I rely on the CMP party ID. I have recoded a few party IDs from parties that had several different IDs because of a change in party name. See appendix, . The results are almost identical when using the original CMP IDs.

11 OECD.stat, National Accounts; Gross Domestic Product (annual); expenditure approach; https://stats.oecd.org/ (data retrieved 12 June 2023.)

12 ILO Labour Force Statistics (LFS); Employment by sex and age (annual); Unemployment by sex and age (annual). The indicator used is “youth, adults 15+” and if not available “youth, adults 15–64”; https://ilostat.ilo.org/data/(data retrieved 12 June 2023).

13 The labour force is defined as “the sum of the number of persons employed and the number of persons unemployed”. https://ilostat.ilo.org/resources/concepts-and-definitions/description-labour-force-statistics/.

14 There are several reasons for including GDP growth and unemployment as measures of economic context. First, these are arguably the indicators that are most often reported in the news, they are easy to understand for most people and so it is most likely that the public reacts to changes in GDP and unemployment. They are easily the most important sources of economic grievances – besides inflation. Second, by using the two indicators I follow a long tradition in different literatures on economic voting (e.g., Powell & Whitten, Citation1993; Lewis-Beck & Stegmaier, Citation2000), economic context and party competition (e.g., Singer, Citation2011; Williams et al., Citation2016; Traber et al., Citation2018) and economic grievances during the financial crisis in Europe (e.g., Kurer et al., Citation2019; Kriesi et al., Citation2020). Third, these indicators are available on a yearly basis for a large number of countries and a long time period. In addition, we could include inflation, which is also often used in the literature. Unfortunately, information on consumer prices is only available for a much smaller country sample and shorter time period. Regarding the country selection (countries in the European Union), inflation also arguably played a smaller role in the economy – due to the Maastricht criteria, consumer prices were quite stable for a long period in the early twenty-first century, such that economic experts wondered about the “death of inflation” (e.g., Economist 2013: https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2013/04/13/the-death-of-inflation. Table 10 in Appendix C shows results of regression models including consumer prices as an independent variable (same measure, lagged weighted average). The results show that inflation did not have an influence on party polarization in the period under study.

15 Data retrieved via GESIS data catalogue; https://www.gesis.org (latest data retrieval August 2022).

16 I thank the anonymous reviewer for suggesting these two labels.

17 The answer categories vary only slightly during the time period: In 2011 “government debt” was introduced instead of “defense”, and the two categories “energy” and “environment” were combined into one.

18 Years between elections are included in the graph by using the values from the previous election.

19 The picture is almost identical when we include parties with no seat in parliament. See in the Appendix.

20 Items in the CMP RILE index, excluding economic issues, but adding multiculturalism positive/negative.

21 Categories per504 and per505 in the CMP dataset.

References

- Adams, J., De Vries, C. E., & Leiter, D. (2012a). Subconstituency reactions to elite depolarization in The Netherlands: An analysis of the Dutch public’s policy beliefs and partisan loyalties, 1986–98. British Journal of Political Science, 42(1), 81–105. doi:10.1017/S0007123411000214

- Adams, J., Green, J., & Milazzo, C. (2012b). Has the British public depolarized along With political elites? An American perspective on British public opinion. Comparative Political Studies, 45(4), 507–530. doi:10.1177/0010414011421764

- Adams, James, Samuel Merrill III and Bernhard Grofman. 2005. A unified theory of party competition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Allan, J. P., & Scruggs, L. (2004). Political partisanship and welfare state reform in advanced industrial societies. American Journal of Political Science, 48(3), 496–512. doi:10.1111/j.0092-5853.2004.00083.x

- Ansolabehere, S., & Iyengar, S. (1994). Riding the wave and claiming ownership over issues: The joint effects of advertising and news coverage in campaigns. Public Opinion Quarterly, 58(3), 335–357. doi:10.1086/269431

- Arndt, C. (2016). Issue evolution and partisan polarization in a European multiparty system: Elite and mass repositioning in Denmark 1968–2011. European Union Politics, 17(4), 660–682. doi:10.1177/1465116516658359

- Berger, S. (2000). Globalization and politics. Annual Review of Political Science, 3(1), 43–62. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.3.1.43

- Blyth, M., & Katz, R. (2005). From catch-all politics to cartelisation: The political economy of the cartel party. West European Politics, 28(1), 33–60. doi:10.1080/0140238042000297080

- Boix, C. (2000). Partisan governments, the international economy, and macroeconomic policies in advanced nations, 1960–93. World Politics, 53(1), 38–73. doi:10.1017/S0043887100009370

- Borghetto, E., & Russo, F. (2018). From agenda setters to agenda takers? The determinants of party issue attention in times of crisis. Party Politics, 24(1), 65–77. doi:10.1177/1354068817740757

- Bornschier, S. (2010). The New cultural divide and the Two-dimensional political space in Western Europe. West European Politics, 33(3), 419–444. doi:10.1080/01402381003654387

- Bornschier, S. (2015). The New cultural conflict, polarization, and representation in the Swiss party system, 1975–2011. Swiss Political Science Review, 21(4), 680–701. doi:10.1111/spsr.12180

- Bremer, B. (2018). The missing left? Economic crisis and the programmatic response of social democratic parties in Europe. Party Politics, 24(1), 23–38. doi:10.1177/1354068817740745

- Bremer, B. (2023). Austerity from the left: Social democratic parties in the shadow of the great recession. Oxford University Press.

- Budge, I., & Farlie, D. (1983). Explaining and predicting elections: Issue effects and party strategies in twenty-three democracies. Taylor & Francis.

- Calca, P., & Gross, M. (2019). To adapt or to disregard? Parties’ reactions to external shocks. West European Politics, 42(3), 545–572.

- Caldwell, D. T. (2023). Polarisation and Cultural Realignment in Britain, 2014–2019 [Durham theses]. Durham University. http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/14979/.

- Carmines, E. G., & Stimson, J. A. (1986). “On the structure and sequence of issue evolution.” American political science review 80(3):901–920. Cambridge University Press.

- Clark, T. S., & Linzer, D. A. (2015). Should I Use fixed or random effects? Political Science Research and Methods, 3(2), 399–408. doi:10.1017/psrm.2014.32

- Cohen, G., & Cohen, S. (2021). Depolarization, repolarization and redistributive ideological change in Britain, 1983–2016. British Journal of Political Science, 51(3), 1181–1202. doi:10.1017/S0007123419000486

- Conti, N., Hutter, S., & Nanou, K. (2018). Party competition and political representation in crisis. Party Politics, 24(1), 3–9. doi:10.1177/1354068817740758

- Dancygier, R., & Margalit, Y. (2020). The evolution of the immigration debate: Evidence from a New dataset of party positions over the last half-century. Comparative Political Studies, 53(5), 734–774. doi:10.1177/0010414019858936

- Dassonneville, R., Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2024). Transformation of the political space: A citizens’ perspective. European Journal of Political Research, 63(1), 45–65. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12590

- De Vries, C. E. (2018). The cosmopolitan-parochial divide: Changing patterns of party and electoral competition in The Netherlands and beyond. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(11), 1541–1565. doi:10.1080/13501763.2017.1339730

- Donovan, T., & Bowler, S. (2018). Donald trump’s challenge to the study of elections, public opinion and parties. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 28(2), 125–134. doi:10.1080/17457289.2018.1443713

- Engler, F. (2021). Political parties, globalization and labour strength: Assessing differences across welfare state programs. European Journal of Political Research, 60(3), 670–693. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12413

- Engler, S., & Weisstanner, D. (2021). The threat of social decline: Income inequality and radical right support. Journal of European Public Policy, 28(2), 153–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1733636

- Evans, G., & Tilley, J. (2017). The new politics of class in Britain: The political exclusion of the British working class. Oxford University Press.

- Fenzl, M. (2018). Income inequality and party (de)polarisation. West European Politics, 41(6), 1262–1281. doi:10.1080/01402382.2018.1436321

- Ford, R., & Jennings, W. (2020). The changing cleavage politics of Western Europe. Annual Review of Political Science, 23(1), 295–314. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-052217-104957

- Franklin, M. N., & Wlezien, C. (1997). The responsive public: Issue salience, policy change, and preferences for European unification. Journal of Theoretical Politics, 9(3), 347–363. doi:10.1177/0951692897009003005

- Garrett, G. (1998). Global markets and national politics: Collision course or virtuous circle? International Organization, 52(4), 787–824. doi:10.1162/002081898550752

- Green-Pedersen, C. (2007). The growing importance of issue competition: The changing nature of party competition in Western Europe. Political Studies, 55(3), 607–628. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.2007.00686.x

- Green-Pedersen, C. (2019). The reshaping of west European party politics: Agenda-setting and party competition in comparative perspective. Comparative politics first edition ed. Oxford University Press.

- Green-Pedersen, C., & Mortensen, P. B. (2010). Who sets the agenda and who responds to it in the danish parliament? A new model of issue competition and agenda-setting. European Journal of Political Research, 49(2), 257–281. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.2009.01897.x

- Green-Pedersen, C., & Mortensen, P. B. (2015). Avoidance and engagement: Issue competition in multiparty systems. Political Studies, 63(4), 747–764. doi:10.1111/1467-9248.12121

- Häusermann, S., & Kriesi, H. (2015). What Do voters want? Dimensions and configurations in individual-level preferences and party choice. In P. Beramendi, S. Hausermann, H. Kitschelt, & H. Kriesi (Eds.), The politics of advanced capitalism (pp. 202–230). Cambridge.

- Hellwig, T. (2008a). Explaining the salience of left–right ideology in postindustrial democracies: The role of structural economic change. European Journal of Political Research, 47(6), 687–709. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.2008.00778.x

- Hellwig, T. (2008b). Globalization, policy constraints, and vote choice. The Journal of Politics, 70(4), 1128–1141. doi:10.1017/S0022381608081103

- Hellwig, T. (2014). Balancing demands: The world economy and the composition of policy preferences. The Journal of Politics, 76(1), 1–14. Publisher: The University of Chicago Press. doi:10.1017/S002238161300128X

- Hernández, E., & Kriesi, H. (2016). The electoral consequences of the financial and economic crisis in Europe. European Journal of Political Research, 55(2), 203–224. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12122

- Hillen, S. (2023). Economy or culture? How the relative salience of policy dimensions shapes partisan effects on welfare state generosity. Socio-Economic Review, 21(2), 985–1005. doi:10.1093/ser/mwac005

- Hobolt, S. B., & Tilley, J. (2016). Fleeing the centre: The rise of challenger parties in the aftermath of the euro crisis. West European Politics, 39(5), 971–991. doi:10.1080/01402382.2016.1181871

- Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2018). Cleavage theory meets Europe’s crises: Lipset, rokkan, and the transnational cleavage. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(1), 109–135. doi:10.1080/13501763.2017.1310279

- Huber, E., & Stephens, J. D. (2001). Development and crisis of the welfare state: Parties and policies in global markets. 2nd ed edition ed. University of Chicago Press.

- Hübscher, E., Sattler, T., & Wagner, M. (2023). Does austerity cause polarization? British Journal of Political Science, 53(4), 1170–1188. doi:10.1017/S0007123422000734

- Jakobsson, N., & Kumlin, S. (2017). Election campaign agendas, government partisanship, and the welfare state. European Political Science Review, 9(2), 183–208. doi:10.1017/S175577391500034X

- Karreth, J., Polk, J. T., & Allen, C. S. (2013). Catchall or catch and release? The electoral consequences of social democratic parties’ march to the middle in Western Europe. Comparative Political Studies, 46(7), 791–822. doi:10.1177/0010414012463885

- Katz, R. S., & Mair, P. (2009). The cartel party thesis: A restatement. Perspectives on Politics, 7(4), 753–766. doi:10.1017/S1537592709991782

- Kitschelt, H. (1994). The transformation of European social democracy. Cambridge studies in comparative politics. Cambridge University Press.

- Kitschelt, H. (2000a). Citizens, politicians, and party cartellization: Political representation and state failure in post–industrial democracies. European Journal of Political Research, 37(2), 149–179.

- Kitschelt, H. (2000b). Linkages between citizens and politicians in democratic polities. Comparative Political Studies, 33(6-7), 845–879. doi:10.1177/001041400003300607

- Klüver, H., & Sagarzazu, I. (2016). Setting the agenda or responding to voters? Political parties, voters and issue attention. West European Politics, 39(2), 380–398. doi:10.1080/01402382.2015.1101295

- Klüver, H., & Spoon, J.-J. (2016). Who responds? Voters, parties and issue attention. British Journal of Political Science, 46(3), 633–654. doi:10.1017/S0007123414000313

- Kriesi, H., Grande, E., Lachat, R., Dolezal, M., Bornschier, S., & Frey, T. (2008). West European politics in the age of globalization. Cambridge University Press.

- Kriesi, H., Wang, C., Kurer, T., & Häusermann, S. (2020). Economic grievances, political grievances, and protest. In H. Kriesi, J. Lorenzini, B. Wüest, & S. Hausermann (Eds.), Contention in times of crisis (1st ed., pp. 149–183). Cambridge University Press.

- Kristensen, T. A., Green-Pedersen, C., Mortensen, P. B., & Seeberg, H. B. (2023). Avoiding or engaging problems? Issue ownership, problem indicators, and party issue competition. Journal of European Public Policy, 30(12), 2854–2885. doi:10.1080/13501763.2022.2135754

- Krosnick, J. A., & Kinder, D. R. (1990). Altering the foundations of support for the president through priming. American Political Science Review, 84(02), 497–512. doi:10.2307/1963531

- Kurer, T., Häusermann, S., Wüest, B., & Enggist, M. (2019). Economic grievances and political protest. European Journal of Political Research, 58(3), 866–892. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12318

- Laakso, M., & Taagepera, R. (1979). “Effective” number of parties: A measure with application to west Europe. Comparative Political Studies, 12(1), 3–27. doi:10.1177/001041407901200101

- Lewis-Beck, M. S., & Stegmaier, M. (2000). Economic determinants of electoral outcomes. Annual Review of Political Science, 3(1), 183–219. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.3.1.183

- Mair, P. (2013). Smaghi versus the parties: Representative government and institutional constraints. In politics in the Age of austerity, ed. Armin schäfer and wolfgang streeck (pp. 143–168). Cambridge.

- Miller, J. M., & Krosnick, J. A. (2000). News media impact on the ingredients of presidential evaluations: Politically knowledgeable citizens Are guided by a trusted source. American Journal of Political Science, 44(2), 301–315. doi:10.2307/2669312

- Mutz, D. C. (2018). Status threat, not economic hardship, explains the 2016 presidential vote. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(19), E4330–E4339. doi:10.1073/pnas.1718155115

- Nanou, K., & Dorussen, H. (2013). European integration and electoral democracy: How the European union constrains party competition in the member states. European Journal of Political Research, 52(1), 71–93. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.2012.02063.x

- Norris, P., & Inglehart, R. (2019). Cultural backlash: Trump, brexit, and authoritarian populism. 1 ed. Cambridge University Press.

- Petrocik, J. R. (1996). Issue ownership in presidential elections, with a 1980 case study. American Journal of Political Science, 40(3), 825–850. doi:10.2307/2111797

- Powell, G. Bingham and Guy D. Whitten. (1993). A cross-national analysis of economic voting: Taking account of the political context. American Journal of Political Science, 37(2), 391–414. doi:10.2307/2111378

- Rehm, P., & Reilly, T. (2010). United we stand: Constituency homogeneity and comparative party polarization. Electoral Studies, 29(1), 40–53. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2009.05.005

- Savage, L. (2019). The politics of social spending after the great recession: The return of partisan policy making. Governance, 32(1), 123–141. doi:10.1111/gove.12354

- Schattschneider, E. E. (1960). The semisovereign people. Rinehart and Winston.

- Schmitt, C., & Zohlnhöfer, R. (2019). Partisan differences and the interventionist state in advanced democracies. Socio-Economic Review, 17(4), 969–992. doi:10.1093/ser/mwx055

- Singer, M. M. (2011). Who says “it’s the economy”? cross-national and cross-individual variation in the salience of economic performance. Comparative Political Studies, 44(3), 284–312. doi:10.1177/0010414010384371

- Singer, M. M. (2013). The global economic crisis and domestic political agendas. Electoral Studies, 32(3), 404–410. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2013.05.018

- Soroka, S. N. (2006). Good news and Bad news: Asymmetric responses to economic information. The Journal of Politics, 68(2), 372–385. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2508.2006.00413.x

- Soroka, S. N., & Christopher, W. (2010). Degrees of democracy. Cambridge University Press.

- Spoon, J.-J., & Klüver, H. (2019). Party convergence and vote switching: Explaining mainstream party decline across Europe. European Journal of Political Research, 58(4), 1021–1042. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12331

- Spoon, J.-J., & Williams, C. J. (2021). ‘It’s the economy, stupid’: When new politics parties take on old politics issues. West European Politics, 44(4), 802–824. doi:10.1080/01402382.2020.1776032

- Steiner, N. D., & Martin, C. W. (2012). Economic integration, party polarisation and electoral turnout. West European Politics, 35(2), 238–265. doi:10.1080/01402382.2011.648005

- Stoetzer, L. F., Giesecke, J., & Klüver, H. (2023). How does income inequality affect the support for populist parties? Journal of European Public Policy, 30(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1981981

- Tilley, J., & Evans, G. (2017). The New politics of class after the 2017 general election. The Political Quarterly, 88(4), 710–715. doi:10.1111/1467-923X.12434

- Traber, D., Giger, N., & Häusermann, S. (2018). How economic crises affect political representation: Declining party-voter congruence in times of constrained government. West European Politics, 41(5), 1100–1124. doi:10.1080/01402382.2017.1378984

- Traber, D., Schoonvelde, M., & Schumacher, G. (2020). Errors have been made, others will be blamed: Issue engagement and blame shifting in prime minister speeches during the economic crisis in Europe. European Journal of Political Research, 59(1), 45–67. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12340

- Volkens, A., Burst, T., Krause, W., Lehmann, P., Matthieß Theres, R., Sven, W., Bernhard, Z., & Lisa, Z. (2021). The manifesto data collection. Manifesto project (MRG/CMP/MARPOR). version 2021a. Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WZB). https://doi.org/10.25522/manifesto.mpds.2021a

- Wagner, M., & Meyer, T. M. (2014). Which issues do parties emphasise? Salience strategies and party organisation in multiparty systems. West European Politics, 37(5), 1019–1045. doi:10.1080/01402382.2014.911483

- Ward, D., Kim, J. H., Graham, M., & Tavits, M. (2015). How economic integration affects party issue emphases. Comparative Political Studies, 48(10), 1227–1259. doi:10.1177/0010414015576745

- Williams, L. K., Seki, K., & Whitten, G. D. (2016). You’ve Got some explaining To Do The influence of economic conditions and spatial competition on party strategy. Political Science Research and Methods, 4(01), 47–63. doi:10.1017/psrm.2015.13

- Witko, C. (2016). The politics of financialization in the United States, 1949–2005. British Journal of Political Science, 46(2), 349–370. doi:10.1017/S0007123414000325