ABSTRACT

European integration is at risk of becoming stuck in a ‘politics’ trap: Diverging national EU politicisation inhibits joint agreements which fuels public debates further. What can break this vicious circle? We argue that large and symmetrical exogenous shocks may reduce the divergence of national public EU debates to then study how the COVID-19 and Ukraine crises have altered mediatised EU portrayals across 753,435 articles from 228 major online news sites in the 27 EU member states during the 2018–2023 period. We find that the Covid and especially the Ukraine shock led to higher convergence in the public salience of the EU and the issue areas associated with this while partially also muting domestic party presence. However, we note that these effects appear short-lived. Large exogenous shocks thus do not lift the politicisation constraints on European integration permanently but offer at least windows of opportunity that may facilitate intergovernmental compromise.

Introduction

The process of European integration seems to slip more and more into a ‘politics trap’ (Laffan, Citation2021; Nicoli & Zeitlin, Citation2024). The EU is increasingly politicised in domestic public debates which has made individual governments much more cautious in agreeing to ambitious European compromises (Hooghe & Marks, Citation2009; Rauh, Citation2021). The resulting failures to agree on effective European policy spur more public debate about the EU which reduces the scope for intergovernmental compromises even further. The quickly succeeding crises with their overlapping cross-national conflict lines and insufficient policy outcomes that characterise the recent decades of European integration – not the least the clashes between creditor and debtor states during the Eurocrisis and then between frontline and destination states in the refugee crisis – illustrate this detrimental, potentially self-reinforcing dynamic rather vividly (Börzel & Risse, Citation2017; Zeitlin et al., Citation2019).

What can break this vicious circle? This article focusses on the role of large and symmetrical exogeneous shocks (Ferrara & Kriesi, Citation2022) to analyse whether the two latest additions to the EU’s decades of ‘polycrisis’ – the Covid-19 pandemic as well as the Russian invasion of Ukraine – have lifted the constraints that public politicisation creates for joint European decision-making.

We start from the view that public politicisation does not automatically have to constrain European integration. What rather matters is the degree to which the resulting public debates diverge across member states. Debate divergence – already a key concern in the earlier literature about a potential European public sphere (e.g., Koopmans & Erbe, Citation2004; Trenz, Citation2004; Weßler et al., Citation2008) – is what essentially drives the ‘politics trap’ logic: the space for joint European solutions that each individual government can also electorally defend at home only shrinks if and when public politicisation follows nationally ‘differentiated’ patterns that are ‘misaligned’ across the 27 domestic public spheres (De Wilde et al., Citation2016; Nicoli et al., Citation2023). Conversely, a cross-national convergence of public EU debates would rather be enabling for intergovernmental agreement.

We theorise that the Covid-19 pandemic and the Russian war on Ukraine share three important features that jointly render such a cross-national convergence of public EU debates likely. First, both shocks are largely exogenous to prior EU politicisation dynamics. They do not originate from within the Union, are not a direct consequence of prior EU policy failures, and do not squarely fall into the policy areas that have structured EU politicisation in recent decades. Second, both shocks present rather unprecedented and extraordinary threats for individual and collective security as well as dire economic consequences. Different theoretical perspectives suggest that such settings produce public debates that transcend ‘normal politics’ in the name of collective action and functional imperatives. Third, compared to prior EU crises both the pandemic and the war affect EU member states in a relatively more symmetrical manner. All EU members were exposed to both shocks at roughly the same points in time and all of them had to expect decidedly negative consequences that could be mitigated by joint solutions.

We thus expect debate convergence around these two shocks – meaning that the EU is equally strongly emphasised, is associated with similar issues and topics, and is less framed in terms of domestic party politics across the individual public spheres of the EU-27 states.

After expanding these arguments, we take a big data perspective to study the macro-level implications of our argument in mediatised public debates. Building on the GLOWIN data infrastructure (Parizek & Stauber, Citation2024), we analyse a sample of 753,453 articles from 228 leading online news media sources across all 27 EU member states between January 2018 and April 2023. We extract text-based indicators for the public salience of the EU, the issue areas the EU is associated with, and the presence of domestic political parties in EU-related reporting.

Our findings highlight that public debates strongly and consistently turned attention on the EU with the onset of the pandemic and especially the Russian invasion of Ukraine. We furthermore observe a stronger issue focus and convergence around the EU in public debates, and find a reduced parallel presence of domestic political parties at least in some countries. While we thus observe debate convergence around both shocks, the effects also appear short-lived and do not fully compensate for diverging patterns we find outside of pandemic- or war-related reporting.

In conclusion, the two extraordinary exogenous shocks we cover here do not readily provide permanent exits from the ‘politics trap’, but they have at least temporarily lifted the integration constraints that the divergence of domestic EU politicisation creates. Large and symmetrical exogenous shocks thus offer windows of opportunity that facilitate more functional intergovernmental compromises which may at least dampen the entrenched dynamics of EU policy failures and further diverging politicisation.

What exactly leads European integration into the politics trap?

To understand the paths into and out of the politics trap, we need to clarify how exactly public EU politicisation affects decisions for or against further European integration. The grand integration theories provide diverging pointers in this regard (cf. Rauh, Citation2021).

Neo-functionalists expected growing public attention to supranational politics over time, viewed this very optimistically: the persuasive power of strong functional pressures and common gains together with the pro-active engagement of national and supranational elites in public debates would contribute to ‘a shift in actor expectations and loyalty toward the new regional center’ (Schmitter, Citation1969, pp. 165–166). Public politicisation, in this view, is another if not the penultimate expression of the neo-functionalist spillover logic that propels integration forward.

Liberal intergovernmentalists, in contrast, saw European integration as an exclusively elite affair driven solely by governmental preferences and powerful domestic commercial interests (Moravcsik, Citation1998). These elites build institutions insulated from short-term political pressures while the EU would primarily only operate ‘in areas where most citizens remain “rationally ignorant”’ (Moravcsik, Citation2006, p. 613). Public politicisation, in this view, is rather irrelevant for integration.

The recently prominent postfunctionalist theory of European integration by Hooghe and Marks (Citation2009) put politicisation centre stage. In this argument, the competence transfers in the Maastricht Treaty shifted European integration from a functionally motivated, elite-driven process into the domain of domestic party politics. Citizens are assumed to have few priors on European integration and heuristically resort to their national identities instead. This creates a fertile mobilisation ground for ‘traditionalist, authoritarian, and nationalist’ (TAN) challenger parties that pro-actively cue voters against Europe. The fear of electorally losing out against such parties then lets national governments shy away from further integration. The resulting ‘constraining dissensus’ ultimately suggests a saturation point of European integration, turning public politicisation into a key factor explaining how far political cooperation in Europe can go.

These arguments highlight useful links between public politicisation and integration choices, especially by pointing to the relative importance of functional and electoral concerns on part of national governments. Yet, their uniform predictions warrant caution. All three arguments – from neo-functionalist optimism, through intergovernmentalist irrelevance, to postfunctionalist pessimism – hinge on rather static assumptions about the nature of public EU debates. The literature that aims to explain EU politicisation, in contrast, reveals a much more dynamic picture along the interplay of the demand for and the supply of public debate about the EU.

Regarding societal demand, already Lindberg and Scheingold (Citation1970, pp. 277–278) put a disclaimer on their famous diagnosis of a ‘permissive consensus’: ‘the level of [public] support or its relationship to the political process would be significantly altered’, if the European Community were ‘to broaden its scope or increase its institutional capacities markedly’. Politicisation, in this view, is a function of the transfer of political competences to institutions beyond the nation state: The more such institutions can or do take collectively binding decisions, the more societal actors will learn that their interests are affected and will air their respective demands in public debates (Zürn et al., Citation2012). Such demands, however, must not exclusively feature fundamental opposition against integration only. They may as much involve calls for more or for different European policy (Rauh & Zürn, Citation2014).

Comparativists rather stress the partisan supply of public EU debate (e.g., Hutter et al., Citation2016), assuming that the electorate is highly susceptible to elite cueing (e.g., Hobolt, Citation2007). In this view, EU politicisation does not grow linearly, but the risk that parties raise EU issues has increased over time. Challenger parties have strategic incentives to mobilise on European integration where mainstream parties leave this terrain uncharted (De Vries & Hobolt, Citation2020; Van der Eijk & Franklin, Citation2004). Enhanced EU policy-making furthermore incentivizes mainstream opposition parties to hold their governments accountable for decisions in Brussels (Hutter & Grande, Citation2014). But also such party-driven conflicts cannot solely be reduced to mere EU-opposition. Rather, parties make offers for different policies within the EU (e.g., Braun et al., Citation2016).

In our view, demand- and supply-side logics co-exist and condition each other: Domestic party elites both respond to and shape the views of their potential voters (e.g., Steenbergen et al., Citation2007) while there are multiple interdependencies between the different arenas of EU politicisation and the behaviour of the diverse actors within them (De Wilde, Citation2011). From such a dynamic perspective, however, uniformly positive, neutral, or negative effects of domestic politicisation on individual governments’ integration stances appear implausible.

Let us provide a few empirical snapshots supporting this claim and consider the demand side first. Public support for a country’s EU membership – the most ‘existential fact of European integration’ (Eichenberg & Dalton, Citation2007, p. 133) – indeed slumped after the Maastricht Treaty as indicated by the respective, biannually collected Eurobarometer item. Since then, however, its mean level fluctuates around rather stationary averages that stay mostly in the pro-integration range of the item’s scale (e.g., Rauh et al., Citation2020).Footnote1 But while there is no general trend in public EU support, the distributions behind these stationary averages have flattened somewhat since Maastricht which has further accelerated with the Eurocrisis (Down & Wilson, Citation2008; Rauh, Citation2016, chapter 2): Citizens have moved modestly in both directions on the EU support/opposition scale, suggesting a slightly more polarised public opinion. Notably, however, this speaks against uniform politicisation effects on European integration: Political elites do not necessarily gain from adapting their integration positions to some average swing in the public mood. They rather must often decide strategically which side to pick in their quest to maximise voter support.

Consistent with this, empirical supply-side analyses of EU politicisation show diversified patterns. In their analysis of mass-mediated partisan EU politicisation in national election campaigns since the 1970s, for example, Hutter and Grande (Citation2014) do not find a single upward trend but rather identify marked spikes across time and countries. Also when focussing on debates around major integration steps (Hutter et al., Citation2016) they find ‘punctuated politicisation’ (Grande & Kriesi, Citation2016, p. 280). In this research, the mobilisation by TAN-parties stressed by postfunctionalist is one, but not the only path to more intensifying EU debates (Grande & Kriesi, Citation2016, p. 293).

Supply-side analyses furthermore show that those elites that have driven European integration along functional considerations in the past also play a decisive role in cueing public debates: Executive actors from both the national and the supranational level account for a high share of mediatised statements on EU affairs, mostly outnumbering challenger and opposition parties (Grande & Hutter, Citation2016, pp. 69–70; Koopmans & Erbe, Citation2004). Cueing the public mood on European integration, in other words, is not exclusively reserved for Eurosceptic parties. Supranational actors have been shown to pro-actively supply communication on the added value of European decision-making when they face controversial public debates (De Bruycker, Citation2017; Hartlapp et al., Citation2014, chapter 9; Rauh, Citation2016). And the cues that national executives send to their publics vary along the specific interplay of public opinion and partisan competition that they face (Rauh et al., Citation2020).

This review suggests that public EU politicisation has no inbuilt direction. It is hardly irrelevant for individual national governments contemplating integration decisions, but neither it’s enabling, nor its constraining effects appear as set in stone. Assessing how politicisation affects specific integration choices rather requires time- and policy-specific perspectives (Börzel & Risse, Citation2017; Ferrara & Kriesi, Citation2022; Hooghe & Marks, Citation2019; Rauh, Citation2021; Saurugger, Citation2016).

What public politicisation does in the aggregate, however, is to raise the complexity of joint decision-making. The configurations of EU politicisation can vary wildly across both time and member states. ‘Discursive opportunities’ around specific European decisions or crises (De Wilde & Zürn, Citation2012) interact with domestic party politics and individual government’s functional and electoral concerns which often produces rather distinct national or sometimes even regional patterns of public EU debates (Hutter & Kriesi, Citation2019).

In effect, any potential European agreement must not only address the functional demands of the challenge at hand, but rather must be electorally defensible in separate or even disparate domestic public debates. What matters most for the effect of politicisation on choices for further integration, then, is the degree to which the resulting public debates are ‘misaligned’ across EU member states (Nicoli et al., Citation2023). It is not public debates per se that hamper European will formation, it is the fact that these debates happen in compartmentalised public spheres (e.g., Koopmans & Erbe, Citation2004; Trenz, Citation2004; Weßler et al., Citation2008) which produce ‘differentiated’ patterns of EU politicisation (De Wilde et al., Citation2016).

The more domestic public debates differ in the degree to which they associate the EU with a given functional challenge, the more they associate the EU with different policy issues, and the more they debate the EU primarily in the context of domestic party politics, the harder it will be for the collective of European governments to identify and to agree on a jointly acceptable bargain for further integration – if there is a non-empty agreement space at all. In other words, not the presence but the divergence of public debates on the EU is what leads European integration into the politics trap.

What is worse, European integration is then likely to slip further into this trap (Laffan, Citation2021): National leaders’ failure to find jointly defensible agreements on a specific functional challenge produce suboptimal policy outcomes on the EU level. This increases societal dissatisfaction with the EU (the demand side) which can be exploited for additional mobilisation of anti-European sentiments in partisan debates (the supply side). The resulting increases in domestic EU politicisation, in turn, reduce the scope for future intergovernmental compromise even further.

This detrimental, endogenous dynamic characterises the recent decades of ‘polycrisis’ in the EU (Nicoli & Zeitlin, Citation2024; Zeitlin et al., Citation2019). In particular, the hectic intergovernmental summitry around the Euro and then the migration crises illustrate how heated domestic debates and corresponding failures to reach effective European compromises interact to produce multiple, overlapping cross-national conflict lines that spill over from one crisis to the next (see also Börzel & Risse, Citation2017). Given specific national integration experiences, varying patterns of national affectedness by the specific crises, and distinct long-term trajectories of domestic partisan conflict, Hutter and Kriesi (Citation2019) even detect regional clusters that separate the domestic patterns of EU politicisation across North-Western, Southern, as well as Central- and Eastern EU member states. Along this line, the cross-national and cross-regional divergence of public EU debates has solidified, thereby pushing European integration further into the politics trap. Thus, we ask: What can break this vicious circle?

Why and which exogeneous shocks may offer an exit from the politics trap

Our theoretical approach to this question starts from the key insight of the preceding discussion: the way into the politics trap is paved by the divergence of domestic public debates about the EU. Inversely, we focus on debate convergence as the most promising route out of the politics trap. The more each domestic debate similarly links the EU explicitly to a given functional challenge, the more the different domestic debates focus on similar issues in this regard, and the less the EU is associated with idiosyncratic domestic party politics, the more easily can the group of national leaders identify a set of jointly defensible European agreements.

That is not to say that converging public debates would make intergovernmental negotiations superfluous by readily resolving any policy conflict in European integration. But debates that converge on the EU as a relevant actor and focus on a limited set of similar issues would lift the political complexity and soften the solidified conflict lines that have hampered agreement on further European integration in the recent past. Along this line, debate convergence would interrupt the detrimental, self-reinforcing dynamic that pushed common decision-making further and further into the politics trap over the last decade.

Yet, the preceding discussion also highlights that debate convergence is hard to achieve. Two particular obstacles stand out. On the one hand, EU politicisation follows punctuated, event-driven, and nationally idiosyncratic patterns. By implication, then, debate convergence requires common crystallisation points, that is events that are politically salient across all member states at the same point in time. On the other hand, the divergence of domestic EU debates is endogenous to prior cross-national conflict lines and EU policy failures. By implication, then, debate convergence is more likely in response to external impulses from outside the EU in geographical and especially in functional terms.

These arguments lead to our core expectation: Common exogenous shocks offer an exit from the politics trap through producing a convergence of domestic public debates about the EU. However, in the context of public EU politicisation we cannot just reiterate the simplistic argument that European integration is forged through crisis. While we see value in the neo-functionalist argument that collectively faced challenges can align public debates about the EU, our preceding discussion also requires us to specify how an exogenous shock affects the interplay of demand and supply-side logics of domestic EU politicisation. In this regard, we consider two additional features of exogeneous shocks relevant.

First, particularly large shocks – in the sense of their negative societal consequences – should be more conducive for debate convergence. Theories of securitisation (Buzan et al., Citation1998) and emergency politics (Kreuder-Sonnen & White, Citation2022) stress that regularised and well-worn patterns of ‘normal politics’ become interrupted especially in the face of existential threat perceptions. On the demand side, highly salient threats are typically accompanied by rally-around-the-flag effects, a stronger sense of community, a narrower issue focus, and rising levels of executive trust in public opinion (e.g., Bol et al., Citation2021; Nicoli et al., Citation2024; Steiner et al., Citation2023). On the supply side, executive power holders thus have an advantage in cueing and focussing the public debate while challenger parties trying to mobilise wedge issues should find much less resonance in such contexts. At the aggregate level, this should produce more focussed debates with less visibility of partisan conflict.

Second, expanding on Ferrara and Kriesi (Citation2022, esp. pp. 1358–1361), the symmetry of cross-national shock exposure should matter for debate convergence. On the demand side, citizens will focus less on distributive zero-sum conflicts in the EU if all member states and their societies stand to lose from an exogenous shock. The experience of shared losses (or the threat thereof) increases ‘expectations of community’ and support for cross-national solidarity among the citizenry (Cicchi et al., Citation2020; Genschel & Jachtenfuchs, Citation2021; Kyriazi et al., Citation2023; Nicoli et al., Citation2024). On the supply side, this inhibits challenger parties from successfully mobilising ‘exclusive national identities’ (Ferrara & Kriesi, Citation2022, p. 1360) while executive actors are electorally less constrained in committing to joint EU decision-making. At the aggregate level, we would then expect that the EU becomes more salient across national debates which explicitly flag it as a relevant actor relating it to the functional shock at hand. Relatedly, we expect that the EU is associated with similar issues while there should be weaker associations of the EU with domestic political parties across national debates.

Taken together, these interrelated mechanisms lead to our key expectation: large, symmetrical, exogenous shocks should produce more aligned public EU debates. The empirically observable implications of this argument are (a) a rising public salience of the EU explicitly related to the specific shock, (b) a stronger and converging focus of issues the EU is associated with, and (c) a weaker association of the EU with domestic political parties within and especially across the different domestic public debates.

Importantly, this argument implies that the two latest additions to the EU’s ‘polycrisis’ – the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of the Ukraine – do not push European integration further into the politics trap. Both crises differ from the recent prior ones exactly in the three features that our theoretical argument highlights as being conducive for debate convergence.

First, the pandemic and the Russian war can be much more clearly characterised as exogenous to prior European integration: The virus and Putin’s decision to initiate a war were not a function of European integration itself. While the Euro- and the migration crisis also had external triggers, their evolution was much more deeply intertwined with pre-existing EU structures and policies. That the global financial crisis turned into a crisis of the Euro, for example, stemmed not the least from the inconsistencies of a common currency without appropriate common fiscal competences. And that mounting political instability in the Global South turned into a decidedly European migration crisis was not the least triggered through the inconsistencies of internally open borders without an appropriate common asylum policy.

Second, both the pandemic and the Russian war differ from other recent European integration crises in terms of the shock size on member states’ societies. Covid-19 caused not only unprecedented strain on healthcare systems and a significant loss of life, but also triggered rather immediate economic downturns and major disruptions in the daily life of all EU citizens. Similarly, the return of war to the European continent made security threats very tangible to European citizens not only in terms of the geographical proximity of violent fighting, but also in terms of further economic downturns, strains on food supply chains, and quickly surging energy prices for everybody. To be clear, the Euro- and migration crises were also rather severe in their economic and humanitarian impacts. But compared to the pandemic and the war, they were less directly and less immediately tangible for each and very EU citizen, they were less multi-faceted in their consequences, and their most tangible consequences were locally much more concentrated.

Third and relatedly, the fallouts of the pandemic and the Russian war are relatively more symmetrically distributed across EU member states (Bojar & Kriesi, Citation2023; Ferrara & Kriesi, Citation2022). Their specific impacts vary as well, for example with a view to different healthcare systems in the case of Covid-19 or along varying levels of energy dependency and geographical proximity in the case of the war in Ukraine. But their consequences were clearly and strongly negative across all EU member states and centred much less on unequal burden sharing. In contrast, the fallouts of the Euro- and migration crises varied much more drastically across member states, pitting creditor against debtor or frontline against destination states, leading to distributive conflicts in terms of budget re-allocations or migration quotas rather than to joint burden sharing.

Of course, exogeneity, shock size, and symmetry are not strictly binary variables – one could still argue that countries with weaker health systems or those geographically closer to Russia experience either of the two shocks differently. And given the punctuated nature of politicisation dynamics one should also be cautious regarding long-term predictions.

Yet and still, in the light of the theoretical arguments above and compare to other recent EU crises, the Covid-19 and the Ukraine crises provide almost ideal conditions for the classical neo-functionalist expectation that overarching functional concerns can spill over into and re-align domestic public debates about the EU. From a theoretical point of view but also from a political worry about the EU’s capacity to act on the resulting societal challenges under conditions of public politicisation, thus, the question whether these two shocks lead to more convergence of public EU debates – thereby interrupting the entrenched ‘politics trap’ dynamics – appears highly relevant.

Data: the EU in mediatised debates across the EU-27 in the 2018–2023 period

To tackle this question, our empirical approach focuses on mediatised debates in line with much of EU politicisation research (e.g., De Wilde, Citation2019; Hutter et al., Citation2016; Rauh, Citation2016, chapter 2; Statham & Trenz, Citation2012). Media are not the only societal arena of EU politicisation, but for three reasons they are an important if not the most important one.

First, public resonance is a defining element of any conceptualisation of politicisation, and a necessary condition in most. In modern ‘audience democracies’ (Manin, Citation1997) governed by ‘mediated politics’ (Bennett & Entman, Citation2000), it is first and foremost public media that provide such resonance.

Second, controversiality is another defining element of politicisation. In this regard, public media are the arena in which both the demand- and the supply-side logics of politicisation meet. News value theory tells us that journalists cover issues they consider of interest to their consumers while they are also biased towards reporting on executive powerholders and on those who air controversial positions (Galtung & Ruge, Citation1965; Harcup & O’Neill, Citation2001). Media are thus likely to reflect issues of contemporary public salience, as well as executive and adversarial communication strategies – they should accordingly pick up EU politicisation when it occurs on either the demand or the supply side.

Third and finally, politicians themselves learn about societal debates and public opinion primarily from the media (Van Aelst & Walgrave, Citation2016). If executives must ‘look over their shoulders when negotiating European issues’ (Hooghe & Marks, Citation2009), the domestic media will largely determine what they see. Thus, also from the perspective of the theorised politicisation effects on European integration, mediatised debates are highly relevant.

To gather encompassing information on such mediatised debates about the EU, our analyses focus on online news websites. As representative surveys on news consumption show (Newman et al., Citation2023, see also Appendix 8.1), citizens across most EU member states draw their political news primarily and dominantly from online sources rather than from TV or print media.

Specifically, we resort to the large-scale data infrastructure offered by the ‘Global Flows of Political Information’ project (GLOWIN; Parizek, Citation2023; Parizek & Stauber, Citation2024).Footnote2 The GLOWIN data collection initially builds on the lists of URLs crawled for the Global Database of Events, Language, and Tone (GDELT; Leetaru & Schrodt, Citation2013),Footnote3 the largest and most long-standing automated event coding engine that ingests around half a million of articles from 60,000 websites around the world per day. GLOWIN first draws a random 10 per cent sample from this list, selects all sources that rank among the top-500 most visited websites in each country of the world, accesses the publicly available full-text content of articles from each original source website, and automatically translates 20 per cent of the resulting data into English via Google Translate. In sum, this results in a quasi-random sample of around 3000 English full-text articles from around the world per day.

For our purposes, we filtered this data further including only domestic political news websites from the EU-27 states that are consistently available throughout our investigation period. A detailed walkthrough and benchmarks for this extensive sampling and data cleaning procedure is provided in Appendix A.1. Ultimately, we cover 228 dedicated political online news sources that are among the most visited websites in all 27 EU member states (between two and 26 sources per country, roughly proportional to population size). GLOWIN provides us with quasi-random, English full-text sample of 753,435 articles that these major news sources have published between 1 January 2018, and 30 April 2023. This covers both exogenous shocks of interest and is probably the most encompassing source of systematic information about recent mediatised public debates in Europe that one can currently access. So how does the EU figure therein and how did the two exogeneous shocks alter the observed patterns?

EU salience in mediatised public debates 2018–2023

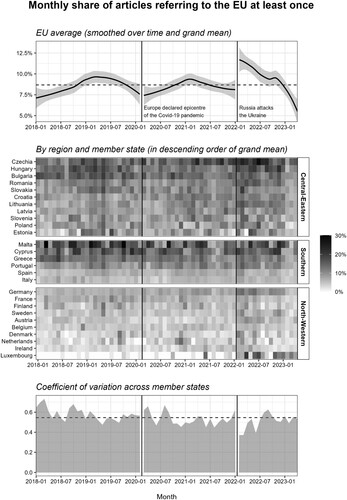

A first macro-level implication of our argument is that the pandemic and Ukraine shocks are explicitly associated with the EU and increase its salience in public debates. Operationally we understand salience as the relative degree to which the EU figures in mediatised debates of its member states. Starting from an established dictionary of EU references (Rauh & De Wilde, Citation2018) we measure this along unequivocal, literal references to EU politics: we count how many articles in our sample refer literally to the European Union itself (including its treaties and pillars), to its key institutions (Council, Parliament, Commission, ECB, and ECJ) and their presidents (by name), as well as to decidedly European programmes, policies, and decisions (full detail in Appendix A.2). In total, the EU appears in 65,997 of the 735,435 articles in our sample by that measure. That is, around 8.8 per cent of articles from the most read political online news websites in the member states refer to the EU. However, there is notable variation over countries and time summarised in .

The upper panel shows the average public EU salience across all member states. For this grand mean we initially see a local maximum around the EP elections in spring 2019 that reverts to its investigation period mean (dashed line) during the summer. More importantly, the aggregate public EU salience did not increase with the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic during early 2020. After the WHO declared Europe an epicentre of the pandemic in March 2020, we rather observe substandard levels of EU media presence but also see that this reverts to the long-term mean by the end of 2020.

Very much in contrast, the descriptive pattern suggests a strong structural break in public EU salience around the Russian invasion of the Ukraine in February 2022: by our measure it jumps in a statistically significant and substantially important manner by around 2.5 percentage points – by far exceeding the local maximum around the EP elections in 2019. This high level of public EU salience is sustained until late summer 2022 when it reverts to the long-term mean, followed by a drop at the end of our investigation period in spring 2023.

To what extent are these aggregate patterns in public EU salience consistent across the member states? The middle panel of plots EU salience across our media samples of individual countries. Following the argument that prior crises have solidified politicisation patterns also on a regional level (Hutter & Kriesi, Citation2019, see above), we group countries into three broad regions to spot whether geographical fault lines in public EU politicisation are reproduced or broken by the two shocks under analysis.

We see rather idiosyncratic dynamics within countries over time, but also hints to some more persistent cross-sectional patterns. On the regional level (indicated by respective rows in the middle panel of ), EU salience is on average highest in the Central-Eastern EU member states where especially Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Bulgaria peak out. The South-European countries show the second-highest levels of EU salience in mediatised debates on average, but with notable variation across countries within the region. The EU is comparatively salient in Malta, Cyprus, Greece, and Portugal, but much less present in our samples from Spain and Italy. The latter two countries are closer to the relatively low levels of public EU salience in the north-western EU members, among which Germany and France are somewhat positive outliers.

The region- and country-level data in the middle panel of thus do not suggest a clear joint trajectory of public EU salience around or after the declaration of Europe as an epicentre of the Covid-19 pandemic. But we indeed can spot cross-country convergence at the onset of the Russian war on the Ukraine as the tiles of virtually all EU member states become darker during and after February 2022.

The lower panel of aggregates this variability over countries into a coefficient of variation. That is, we divide the standard deviation across EU member states by the grand EU average for each month so that higher (lower) values indicate divergence (convergence). This perspective does not show consistent long-term trends, but it confirms that especially the Ukraine shock was at least temporarily associated with less variability in the generally high public EU salience across all member states in spring and early summer 2022.

This aggregate, average perspective on potential shock effects on public EU salience has limits with regard to the question of whether the constraints of the ‘politics trap’ are lifted. In particular, our arguments above require us to study whether the EU is explicitly associated with these shocks, thereby portraying as the appropriate level at which decisions are or should be taken.

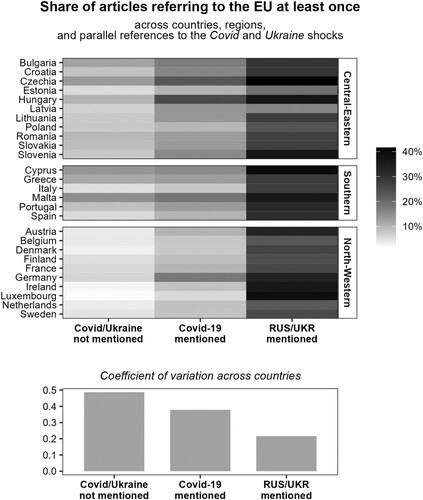

We therefore shift the level of analysis to individual online news articles and use two additional dictionaries to code whether an article refers to the pandemic (by literally mentioning Covid along its different signifiers) or to the Russia/Ukraine conflict (by mentioning both countries, or their leaders and capitals; both dictionaries and temporal distributions of respective articles detailed in Appendix A.2). accordingly plots the EU-salience by country and the coefficient of variation across countries, conditional on whether online news articles mention Covid-19 or the Russia/Ukraine conflict as well (marked on the x-axis).

Across countries (upper panel), we see darker tiles for articles reporting on either of the two shocks of interest than for random articles not mentioning the pandemic or the Russia/Ukraine conflict. Across all member states, thus, EU salience increases within Covid- or Ukraine- related reporting. The EU, in other words, is clearly associated with these two shocks in the public mediatised debates across the EU-27 countries.

These effects are largely similar in size across member states but are much more pronounced for the Russian war on the Ukraine than for the pandemic (confirmed further by country-specific linear probability models in Appendix A.3). The coefficient of variation across countries in lower panel of furthermore shows that the variability in the likelihood that the EU figures in media reporting across countries is much lower when it comes to the pandemic and especially to the Russia/Ukraine conflict. Taking the evidence in this figure together, we can say that particularly the Russian aggression against the Ukraine presented a moment of high and converging public salience of the EU in mediatised public debates on the national level.

In sum, we thus conclude that both exogeneous shocks were associated with the EU in public debates. But only the Russian war shifted the overall public salience of the EU markedly in the aggregate and lead to more converging patterns across the member states with regard to the amount of public reporting on the EU in the first couple of months after the attempted invasion.

Issue focus around EU appearances in mediatised public debates

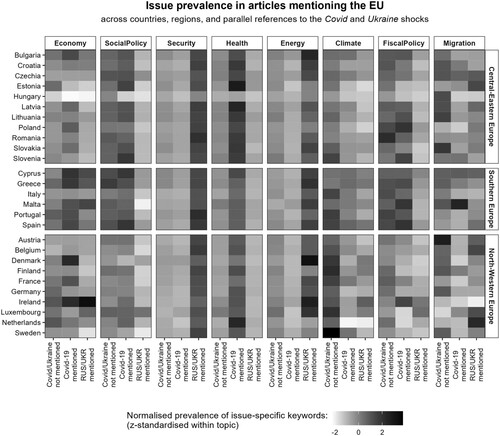

A second implication of our argument on the effects of exogenous shocks on public EU debates is issue convergence. Two theoretical considerations drive our selection of issues for testing this expectation. First, our argument above suggests that the EU becomes much more explicitly associated with the immediate functional challenges that each of the shocks creates. Accordingly, we initially look for ‘health’ and ‘security’ concerns in EU-related media debates. Second, our argument implies that the two shocks crowd out issues that have been divisive within and across national EU debates in the recent past. Given that the politics trap argument has been developed in the context of the Euro- and migration crises, we accordingly consider issues related to ‘economy’, ‘fiscal policy’, ‘social policy’, and ‘migration’. We furthermore add ‘energy’ and ‘climate’ issues as two additional sources of recent intergovernmental conflict in the EU.

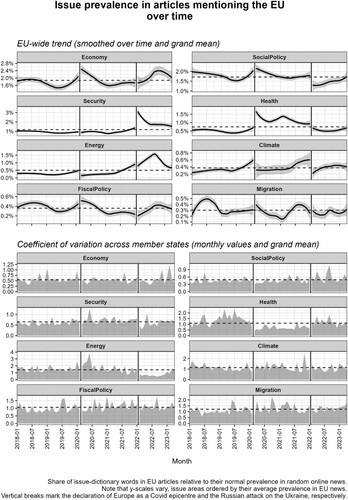

Of course, these issue areas can and probably do mix in the practice of public EU debates. Thus, we do not treat them as mutually exclusive and accordingly design a continuous, text-based measure. Specifically, we started from short seed term list highly characteristic for each issue area, expand each of these lists with the 100 semantically most similar terms from a very large pre-trained word vector model (Pennington et al., Citation2014), to then measure their prevalence in all 65,997 news articles mentioning the EU in our sample relative to the ‘normal’ frequency of these terms in a large random sample of more than 121.000 news articles (detail in Appendix A.5). In short, we measure how strongly the EU is associated with key terms of each issue area relative to the normal prevalence of these issue areas in European online news. summarises the resulting patterns.

The investigation period means (dashed lines in the upper panel) initially show that the EU is primarily associated with ‘economy’ (exemplary keywords are ‘markets’, ‘trade’, or ‘growth’) or ‘social policy’ issues (e.g., ‘education’, ‘inequality’, ‘welfare’). Compared to random news items, words from these issue areas are 1.9 and 1.7 percentage points more likely in EU-related articles. With an average overweight of 1.2 and .7 percentage points, the issue areas ‘security’ (e.g., ‘defence’, ‘military’, ‘peace’) and ‘health’ (‘healthcare’, ‘medical’, ‘hospital’) follow suit. With slightly smaller, yet still positive overweights we see ‘energy’ (exemplified by terms such as ‘oil’, ‘coal’, ‘renewable’; .5 percentage points overweight), ‘climate’ (‘environment’, ‘carbon’, ‘emissions’; .37), ‘fiscal policy’ (‘spending’, ‘deficit’, ‘tax’; .36), and migration (‘immigration’, ‘asylum’, ‘refugees’; .3) further down the line. Benchmarked against a large sample or random news articles, we can thus descriptively conclude that all issue areas we cover here are explicitly associated with the EU in domestic online news during the 2018–2023 period.

For our theoretical interest, however, especially variation over time (monthly EU-wide averages in the upper panel) and variability across EU member states (coefficient of variation in the lower panel of ) matter. We initially see the strongest structural breaks for health and especially security issues around the onset of the pandemic and the Russian invasion of the Ukraine, respectively (plots 3 and 4 in the upper panel). The prevalence of these two issue areas almost tripled around the respective shock. Especially for health issues, this was also associated with a markedly lower coefficient of variation over a rather long period from March 2020 to December 2021 (plot 4, lower panel). The Russia/Ukraine shock also appears to have lowered variability in associations of the EU with security issues across member states, but only did so for the first few months after the invasion (plot 3, lower panel). After the summer 2022, the association of EU reporting with security issues reverts towards its long-term mean and variability across member states returns to prior levels.

Beyond these directly affected issue areas, we also see notable change in the prevalence of tangentially related topics. Energy issues have apparently started to become more strongly associated with the EU already in late 2021, parallel to the built up of forces at the Russian and Belarusian border to the Ukraine (plot 5, upper panel). After the actual Russian invasion, the variability of energy issues in domestic portrayals of the EU also drops notably, suggesting a convergence of public EU debates on this topic as well (plot 5, lower panel).

We also observe some of the theorised crowding out effects. For example, the Russian invasion moved social policy issues somewhat into the background in EU-related media coverage (plot 2, upper panel). And strikingly, local positive trends in the public association of climate issues with the EU were interrupted by both the pandemic and the war shock (plot 6). However, the coefficients of variation for both issue areas suggest that these average effects did not hit all domestic public sphere alike, suggesting a sustained potential for divergence here (plots 2 and 6, lower panel). Finally, the key wedge issues in the recent EU crises – fiscal policy and migration – exhibit short-term fluctuation around their investigation period means in level and variability which, however, does not coincide clearly with the two exogenous shocks we study here (plot 7 and 8, in upper and lower panels, respectively).

We thus do see meaningful changes over time but also note that even those issue areas that appear to have most strongly reacted to either of the two shocks tend to revert to their long-term means. To put this further into perspective, again shifts our level of analysis and studies issue prevalence in EU articles across countries and regions (y-axis) conditional on whether the pandemic or the Russia/Ukraine conflict are mentioned as well (x-axis).

Figure 4. Prevalence of topic markers in EU articles across countries and parallel references to the two exogenous shocks.

This perspective initially reaffirms the strong focussing effect in EU-related reporting on health and security issues related to Covid-19 and the Russian aggression in the third and fourth columns of the figure, respectively. With minor exceptions – notably public portrayals of the EU in Hungary – both shocks are strongly associated with a focus on these issue areas across almost all member states. The same appears to hold for the energy issue when the EU is mentioned in the context of the Russia/Ukraine conflict (fifth column), even though we observe somewhat more variation across member here – where the EU was especially associated with energy issues in Bulgaria, Croatia, and Czechia as well as Denmark, Ireland, and Luxembourg when it comes to reporting about the Russia/Ukraine conflict.

And some of the crowding-out effects become visible in this article-level analysis as well, most notably with the across member states consistently reduced prevalence of social policy topics in EU-related articles that also mention the Russian aggression (second column in ). Interestingly, and initially in contradiction to the aggregate trend seen above, also fiscal policy issues, that were most prevalent in southern and central-eastern member states before, seem to move to the background when the Russia/Ukraine shock is mentioned in relation to the EU (column 7). This, in our view, highlights the issue specificity of EU-related public debates: While the prevalence of fiscal policy issues does not change in the aggregate as seen above, it has less direct relevance when it comes to directly debating the Ukraine shock in relation to the EU.

In sum the descriptive results in this section suggest that large, exogenous and symmetrical shocks can indeed lead to issue convergence and a stronger focus of public EU debates across member states. Such effects, however, appear temporarily confined and do not fully crowd out other diverging and potentially divisive emphasis of specific issues in individual member states or regions.

Associations of the EU with domestic parties in mediatised public debates

A third and final implication of our argument is that the two exogenous shocks should reduce the association of public EU debates and domestic partisan competition. While we cannot reliably extract detailed partisan EU stances from our text data, we can capture the degree to which domestic political parties figure in EU-related reporting at all.

To this end we constructed an extensive dictionary of party names across the EU-27 states by drawing on the name histories in the Comparative Manifesto Project (Lehmann et al., Citation2023), the 64 party datasets linked by the Party Facts database (Döring & Regel, Citation2019), and all names that Wikipedia holds in the English or the respective national languages for any party in any of EU-27 states. The dictionary contains 4221 party names mapping to 595 unique domestic parties (Appendix A.4). We then count the number of different, country-specific parties in our 65,997 articles that mention the EU as well. We repeat this for a random sample of more than 121,000 articles to get country-specific means of party mentions which we then subtract from those observed in EU articles. This way, we capture how strongly the EU is associated with domestic political parties relative to the normal party presence in the respective public sphere.

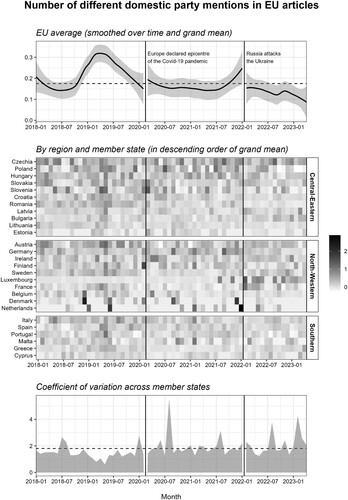

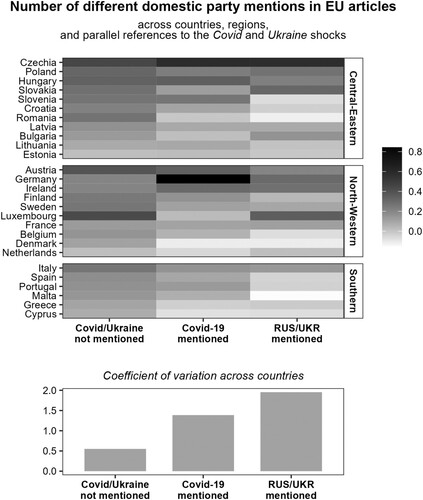

By that measure we first note that co-occurrences of the EU and explicitly mentioned domestic parties are a rare phenomenon: in 80 per cent of EU articles in our sample no name or abbreviation of a specific domestic party is detected. But the average normalised value of mentioned parties in EU articles (.16) is slightly positive, suggesting that party mentions are somewhat more likely in EU-related articles than in random news articles. The value suggests that around every 6th EU article would mention one party more than the average news item. What matters for our interest, however, is variation over time and in relation to the two exogenous shocks. As above, summarises our data as an EU-wide mean (upper panel), on the country and region-level (middle panel), and the respective coefficient of variation across countries (lower panel).

The aggregate time trend across all EU member states in the upper panel initially shows that co-occurrences of the EU and domestic political parties unsurprisingly peaked during the EP elections in spring 2019. This relatively strong association of the EU with domestic parties waned afterwards, returning to its investigation period mean in late summer 2019. The onset of the pandemic in Europe in the beginning of 2020 did not alter this substantially. Only by the end of 2021, the EU becomes more associated with domestic political parties again on average. Yet, this upward trend is clearly broken by the Russian aggression in the Ukraine: In February 2022, the presence of domestic parties in EU-related articles drops notably moving towards a slightly declining trend until the end of our investigation period in April 2023.

However, the patterns for individual countries in the middle panel and their aggregation into the cross-country coefficient of variation in the lower panel of show a high amount of variability around these grand means. Apart from the local peaks around the 2019 EP elections in all countries, we do not see clear common trends or joint temporal effects around both exogeneous shocks. Rather the dominant pattern are individual outliers in specific countries and months.

To better see potential effects of the two exogeneous shocks, we again zoom to the article level and study co-occurrences of the EU and domestic parties conditional on whether Covid-19 or the Russia/Ukraine conflict are mentioned as well. summarises the respective country-means in the upper panel and their cross-country coefficient of variation in the lower panel.

In line with our overarching argument, the pandemic seems to have reduced the presence of domestic parties in EU-related reporting – but only in some countries such as Romania, Bulgaria, Slovakia, Denmark, or Cyprus, for example (middle column of the figure). In others we only see moderate change while the Czech Republic and Germany exhibit above-average domestic party presence in EU-related reporting when Covid-19 is mentioned as well. A similar pattern, but with a different set of countries is found with regard to the Russia/Ukraine shock (right-hand column in the figure). When this conflict is mentioned in EU-related reporting, the presence of domestic parties is significantly reduced in around half of the EU-27 countries. For the other half, however, the likelihood that a domestic party is mentioned stays rather stable when compared to news items not mentioning the two shocks of interest. Moreover, the coefficient of variation in the lower panel of the figure shows that the differences across countries in association of the EU with domestic parties have become more pronounced when Covid-19 or the Russia/Ukraine conflict are mentioned.

In sum, the two exogeneous shocks appear to have had partially strong, but no cross-sectionally consistent effects with regard to weakening the association of the EU with domestic political parties in public debates. In a number of countries, the EU indeed became significantly less associated with domestic party politics in response to the Covid-19 and especially the Ukraine shock. In others, however, the picture is less clear and we observe varying patterns by country and shock. Whether the EU is a matter of domestic party politics, in other words, still hinges to some extent on idiosyncratic national and shock-specific logics that warrant further country-level research.

Conclusions

Over the recent decades of ‘polycrisis’, European integration seems to have slipped more and more into the ‘politics trap’ along a mutually reinforcing dynamic of diverging patterns of domestic EU politicisation and corresponding failures to find common ground for intergovernmental agreement (Laffan, Citation2021; Nicoli & Zeitlin, Citation2024; Zeitlin et al., Citation2019). In this article, we argue that the Covid-19 pandemic and the Russian war on Ukraine may have interrupted this vicious circle: contrasting prior EU-crises, they present large, symmetrical, exogenous shocks that should align the demand and supply sides of domestic EU politicisation in ways that produce more cross-national debate convergence, thereby making room for intergovernmental agreements that are electorally defensible across all individual national public spheres.

Our large-scale analysis of the aggregate debate-level implications of this argument in online news across all EU-27 states during the 2018–2023 period produces descriptive evidence consistent with this view. We find that the EU is strongly and similarly associated with each of the two shocks in all mediatised domestic debates. We also find that an increasing focus on the issues the EU is associated with within and across domestic debates around these shocks. And we find that fewer domestic parties appear in EU-related debates at least in some countries around these shocks. On all three indicators, our data furthermore do not show the perpetuation of specific national or regional patterns of EU politicisation that have solidified during prior crises. Overall, then, the two exogenous shocks we study here resulted in a situation in which national governments faced rather similarly structured domestic debates at home which should reduce the political complexities of finding jointly defensible European agreements.

However, our findings also suggest that these effects should not be overstated. In this regard, we must initially note that the expectation of a weaker association between the EU and domestic political parties has not borne out for all EU countries. Rather, we see idiosyncratic country- and shock-specific variation in the association of the EU with domestic political parties that calls for more detailed analysis.

More importantly, we must note that the observed effects appear rather short-lived. All three indicators revert rather quickly to their long-term means. On the one hand, this is not overly surprising: already prior research highlights the punctuated nature of EU politicisation (Hutter et al., Citation2016) and of public agenda dynamics more generally (Baumgartner & Jones, Citation1991). On the other hand, the observed mean reversions warrant restraint regarding inferences about the long-term consequences of the Covid and Ukraine shocks on EU politicisation. Future research could study, for example, how the debate shifts we uncover here affect the demand side in more general EU attitudes in public opinion (cf. De Vries & Hoffmann, Citation2022).

One further limitation of our work must be made transparent in this regard. While we argue that debate convergence on the EU and on specific issues facilitates intergovernmental agreement, they still may involve significant policy conflict as to how the EU should respond to the shock. Future research could build on the GLOWIN data and exploit recent advances in grammatical and semantic parsing to extract the specific stances and demands put forward in domestic EU debates (cf. Ash et al., Citation2024). Such research may also study the interaction between EU-level action and aggregate debate-level indicators with approaches akin to event study designs in financial econometrics (cf. Rauh & Schneider, Citation2013).

Yet and still, the arguments and findings we present here suggest that exits from the ‘politics trap’ of European integration are possible. Large, symmetrical, exogeneous shocks lift the constraints that the divergence of domestic EU politicisation creates, at least temporarily. As such they offer windows of opportunity that facilitate more functionally minded intergovernmental compromises again – thus dampening the entrenched dynamics of intergovernmental failures and further divergence of public EU debates.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (4.7 MB)Acknowledgements

We are very grateful for the feedback on earlier versions provided especially by Francesco Nicoli, Jonathan Zeitlin, Christian Freudlsperger, Martha Migliorati, as well as three anonymous JEPP reviewers who provided challenging yet highly constructive comments. We furthermore thank Robert Stelzle for help with extracting party names from WikiData and the Manifesto dataset.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Additional empirical information is available in the online appendices accompanying this article and in the replication scripts archived at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/SFFP0N

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Christian Rauh

Christian Rauh is a Senior Researcher in the Global Governance Department at the WZB Berlin Social Science Center and a professor for the ‘Politics of Multilevel Governance’ in the Faculty of Economics and Social Sciences at the University of Potsdam (www.christian-rauh.eu).

Michal Parizek

Michal Parizek is an Assistant Professor and the Deputy Head of the Department of International Relations at the Institute of Political Studies at Charles University, Prague (www.michalparizek.eu).

Notes

1 For more recent periods, also see https://eupinions.eu/en/trends (last accessed: 21 June 2023).

2 https://glowin.cuni.cz/ (last accessed: 22 July 2023).

3 https://www.gdeltproject.org/ (last accessed: 15 March 2023).

References

- Ash, E., Gauthier, G., & Widmer, P. (2024). Relatio: Text semantics capture political and economic narratives. Political Analysis, 32(1), 115–132. https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2023.8

- Baumgartner, F. R., & Jones, B. D. (1991). Agenda dynamics and policy subsystems. The Journal of Politics, 53(4), 1044–1074. https://doi.org/10.2307/2131866

- Bennett, W. L., & Entman, R. M. (Eds.). (2000). Mediated politics: Communication in the future of democracy (Illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Bojar, A., & Kriesi, H. (2023). Policymaking in the EU under crisis conditions: COVID and refugee crises compared. Comparative European Politics, 21(4), 427–447. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-023-00349-1

- Bol, D., Giani, M., Blais, A., & Loewen, P. J. (2021). The effect of COVID-19 lockdowns on political support: Some good news for democracy? European Journal of Political Research, 60(2), 497–505. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12401

- Börzel, T., & Risse, T. (2017). From the euro to the Schengen crises: European integration theories, politicization, and identity politics. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(1), 83–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1310281

- Braun, D., Hutter, S., & Kerscher, A. (2016). What type of Europe? The salience of polity and policy issues in European Parliament elections. European Union Politics, 17(4), 570–592. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116516660387

- Buzan, B., Wæver, O., & De Wilde, J. (1998). Security: A new framework for analysis. Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Cicchi, L., Genschel, P., Hemerijck, A., & Nasr, M. (2020). EU solidarity in times of COVID-19. European University Institute. https://doi.org/10.2870/074932.

- De Bruycker, I. (2017). Politicization and the public interest: When do the elites in Brussels address public interests in EU policy debates? European Union Politics, 18(4), 603–619. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116517715525

- De Vries, C. E., & Hobolt, S. B. (2020). Political entrepreneurs: The rise of challenger parties in Europe. Princeton University Press.

- De Vries, C. E., & Hoffmann, I. (2022). Under pressure – the war in Ukraine and European public opinion. Retrieved January 2024, from https://eupinions.eu/de/text/under-pressure

- De Wilde, P. (2011). No polity for old politics? A framework for analyzing the politicization of European integration. Journal of European Integration, 33(5), 559–575. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2010.546849

- De Wilde, P. (2019). Media logic and grand theories of European integration. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(8), 1193–1212. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1622590

- De Wilde, P., Leupold, A., & Schmidtke, H. (2016). Introduction: The differentiated politicisation of European governance. West European Politics, 39(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2015.1081505

- De Wilde, P., & Zürn, M. (2012). Can the politicization of European integration be reversed? JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 50(S1), 137–153. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2011.02232.x

- Döring, H., & Regel, S. (2019). Party facts: A database of political parties worldwide. Party Politics, 25(2), 97–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068818820671

- Down, I., & Wilson, C. (2008). From permissive consensus to constraining dissensus: A polarizing union? Acta Politica, 43(1), 26–49. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500206

- Eichenberg, R. C., & Dalton, R. J. (2007). Post-Maastricht blues: The transformation of citizen support for European integration, 1973–2004. Acta Politica, 42(2–3), 128–152. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500182

- Ferrara, F. M., & Kriesi, H. (2022). Crisis pressures and European integration. Journal of European Public Policy, 29(9), 1351–1373. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1966079

- Galtung, J., & Ruge, M. (1965). The structure of foreign news. Journal of Peace Research, 2(1), 64–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/002234336500200104

- Genschel, P., & Jachtenfuchs, M. (2021). Postfunctionalism reversed: Solidarity and rebordering during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of European Public Policy, 28(3), 350–369. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1881588

- Grande, E., & Hutter, S. (2016). The politicisation of Europe in public debates on major integration steps. In S. Hutter & E. Grande (Eds.), Politicising Europe: Integration and mass politics (pp. 63–89). Cambridge University Press.

- Grande, E., & Kriesi, H. (2016). Conclusions: The postfunctionalists were (almost) right. In S. Hutter, E. Grande, & H. Kriesi (Eds.), Politicising Europe: Integration and mass politics (pp. 279–300). Cambridge University Press.

- Harcup, T., & O’Neill, D. (2001). What is news? Galtung and Ruge revisited. Journalism Studies, 2(2), 261–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616700118449

- Hartlapp, M., Metz, J., & Rauh, C. (2014). Which policy for Europe?: Power and conflict inside the European Commission. Oxford University Press.

- Hobolt, S. B. (2007). Taking cues on Europe? Voter competence and party endorsements in referendums on European integration. European Journal of Political Research, 46(2), 151–182. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2006.00688.x

- Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2009). A postfunctionalist theory of European integration: From permissive consensus to constraining dissensus. British Journal of Political Science, 39(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123408000409

- Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2019). Grand theories of European integration in the twenty-first century. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(8), 1113–1133. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1569711

- Hutter, S., & Grande, E. (2014). Politicizing Europe in the national electoral arena: A comparative analysis of five West European countries, 1970–2010. Journal of Common Market Studies, 52(5), 1002–1018. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12133

- Hutter, S., Grande, E., & Kriesi, H. (2016). Politicising Europe: Integration and mass politics. Cambridge University Press.

- Hutter, S., & Kriesi, H. (2019). Politicizing Europe in times of crisis. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(7), 996–1017. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1619801

- Koopmans, R., & Erbe, J. (2004). Towards a European public sphere? Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research, 17(2), 97–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/1351161042000238643

- Kreuder-Sonnen, C., & White, J. (2022). Europe and the transnational politics of emergency. Journal of European Public Policy, 29(6), 953–965. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1916059

- Kyriazi, A., Pellegata, A., & Ronchi, S. (2023). Closer in hard times? The drivers of European solidarity in ‘normal’ and ‘crisis’ times. Comparative European Politics, 21(4), 535–553. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-023-00332-w

- Laffan, B. (2021). Europe’s Union in the 21st century: From decision trap to politics trap. Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies Research Paper (RSC 2021/67). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3914033

- Leetaru, K., & Schrodt, P. (2013). GDELT: Global data on events, location and tone, 1979–2012.

- Lehmann, P., Franzmann, S., Burst, T., Regel, S., Riethmüller, F., Volkens, A., Weßels, B., & Zehnter, L. (2023). Manifesto project dataset. https://doi.org/10.25522/MANIFESTO.MPDS.2023A

- Lindberg, L., & Scheingold, S. (1970). Europe's would-be polity: Patterns of change on the European Community. Prentice-Hall.

- Manin, B. (1997). The principles of representative government. Cambridge University Press.

- Moravcsik, A. (1998). The choice for Europe: Social purpose and state power from Messina to Maastricht. Cornell University Press.

- Moravcsik, A. (2006). What can we learn from the collapse of the European constitutional project? Politische Vierteljahresschrift, 47(2), 219–241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11615-006-0037-7

- Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Robertson, C. T., Eddy, K., & Kleis Nielsen, R. (2023). Reuters Institute digital news report 2023. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, University of Oxford. Retrieved March 2023, from https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2023-06/Digital_News_Report_2023.pdf

- Nicoli, F., van der Duin, D., Beetsma, R., Bremer, B., Burgoon, B., Kuhn, T., Meijers, M. J., & de Ruijter, A. (2024). Closer during crises? European identity during the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Journal of European Public Policy, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2024.2319346

- Nicoli, F., Van der Duin, D., & Vaznonytė, A. (2023). The politicization trap and how to escape it: Intergovernmentalism, politicization and competences mismatch in perspective. In A.-M. Houde, T. Laloux, M. Le Corre Juratic, H. Mercenier, D. Pennetreau, & A. Versailles (Eds.), The politicization of the European Union: From processes to consequences (pp. 237–255). Editions de l’Université de Bruxelles. Retrieved January 2023, from https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/59861

- Nicoli, F., & Zeitlin, J. (2024). Introduction: Escaping the politics trap? EU integration pathways beyond the polycrisis. Journal of European Public Policy.

- Parizek, M. (2023). Worldwide media visibility of NATO, the European Union, and the United Nations in connection to the Russia-Ukraine war. Czech Journal of International Relations, 58(1), 15–44.

- Parizek, M., & Stauber, J. (2024). The global media visibility of states dataset V1. OSF. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/2X9R3

- Pennington, J., Socher, R., & Manning, C. D. (2014). GloVe: Global vectors for word representation. In Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP) (pp. 1532–1543). http://www.aclweb.org/anthology/D14-1162

- Rauh, C. (2016). A responsive technocracy? EU politicisation and the consumer policies of the European Commission. ECPR Press.

- Rauh, C. (2021). Between neo-functionalist optimism and post-functionalist pessimism: Integrating politicisation into integration theory. In N. Brack & S. Gürkan (Eds.), Theorising the crises of the European Union (pp. 119–137). Routledge.

- Rauh, C., Bes, B. J., & Schoonvelde, M. (2020). Undermining, defusing, or defending European integration? Assessing public communication of European executives in times of EU politicization. European Journal of Political Research, 59(2), 397–423. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12350

- Rauh, C., & De Wilde, P. (2018). The opposition deficit in EU accountability: Evidence from over 20 years of plenary debate in four member states. European Journal of Political Research, 57(1), 194–216. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12222

- Rauh, C., & Schneider, G. (2013). There is no such thing as a free open sky: Financial markets and the struggle over European competences in international air transport. Journal of Common Market Studies, 51(6), 1124–1140. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12057

- Rauh, C., & Zürn, M. (2014). Zur Politisierung der EU in der Krise. In M. Heidenreich (Ed.), Krise der europäischen Vergesellschaftung? (pp. 121–145). Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden.

- Saurugger, S. (2016). Politicisation and integration through law: Whither integration theory? West European Politics, 39(5), 933–952. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2016.1184415

- Schmitter, P. (1969). Three neo-functional hypotheses about international integration. International Organization, 23(01), 161–166. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818300025601

- Statham, P., & Trenz, H.-J. (2012). The politicization of Europe: Contesting the constitution in the mass media. Routledge.

- Steenbergen, M. R., Edwards, E. E., & de Vries, C. E. (2007). Who’s cueing whom?: Mass-elite linkages and the future of European integration. European Union Politics, 8(1), 13–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116507073284

- Steiner, N. D., Berlinschi, R., Farvaque, E., Fidrmuc, J., Harms, P., Mihailov, A., Neugart, M., & Stanek, P. (2023). Rallying around the EU flag: Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and attitudes toward European integration. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 61(2), 283–301. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13449

- Trenz, H.-J. (2004). Media coverage on European governance: Exploring the European public sphere in national quality newspapers. European Journal of Communication, 19(3), 291–319. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323104045257

- Van Aelst, P., & Walgrave, S. (2016). Information and arena: The dual function of the news media for political elites. Journal of Communication, 66(3), 496–518. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12229

- Van der Eijk, C., & Franklin, M. N. (2004). Potential for contestation on European matters at national elections in Europe. In M. R. Steenbergen & G. Marks (Eds.), European integration and political conflict (pp. 165–192). Cambridge University Press.

- Weßler, H., Peters, B., Brüggemann, M., Kleinen-von Königslow, K., & Sifft, S. (2008). Transnationalization of public spheres. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Zeitlin, J., Nicoli, F., & Laffan, B. (2019). Introduction: The European Union beyond the polycrisis? Integration and politicization in an age of shifting cleavages. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(7), 963–976. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1619803

- Zürn, M., Binder, M., & Ehrhardt, M. (2012). International authority and its politicization. International Theory, 4(1), 69–106. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1752971912000012