ABSTRACT

In this paper, a group of nine international scholars reflect on the collective responsibilities of stakeholders within inclusive educational settings. This reflection was prompted by the need to identify specific elements which would support intentional, collective responsibility to support authentic inclusion for all students. In order to engender this collectivist mindset, mirroring the metaphor of the nurturing village, the group conducted a qualitative study based on structured and semi-structured dialogue, written reflections and previously constructed research to inform a framework to support inclusivity more collectively. Results suggest that nurturing spaces, empathetic relationships, supportive networks and targeted teaching, all contribute to bona fide inclusion, especially if this responsibility is shared and cohesive. Data further revealed that inclusivity is a values-driven process which flourishes when all stakeholders subscribe to common values and tenets regarding socially just educational provision. The authors inculcate the village-mindset, a now popularly received notion, reinforcing the need for active and deliberate dialogue focusing on shared responsibilities and vision. In this paper, we intend to reiterate the need for educational systems which foster more collective, compassionate and nurturing inclusive practice in educational settings.

Context

Research has established the need for a village mindset when accommodating students with diverse profiles and additional learning needs within regular classrooms (Subban & Sharma, Citation2021; Subban et al., Citation2022). This collectivist mindset is a departure from previous thinking which relegated the responsibility of inclusion to just a few, rather than embracing the plethora of joint skills present within an educational system (Subban et al., Citation2022). In the context of this investigation, the ‘collectivist’ mindset is viewed as the active and intentional involvement of a range of stakeholders, to ensure that students with disabilities are appropriately and effectively accommodated within school classrooms. This form of inclusivity has already formed the basis of research within educational contexts (Katz, Citation2017; Sobsey, et al., Citation2017; Howley, et al., Citation2017), and these studies have formed a springboard from which the current investigation mounts. In this report, we consider the complex interplay between the contributions and responsibilities of individual members of school communities, essentially positioning the school as a village (Katz, Citation2017). We note that in order for this collectivist mindset to succeed, individual members should share a common frame of mind (Subban et al., Citation2022). Previous studies, as pointed out earlier, have acknowledged the need for a ‘village’ mindset, however the task of inclusion is intentional and structured, with all key players working alongside each other according to a systematic plan, formulated with distinct roles to facilitate and implement authentic inclusion (Specht, et al., Citation2016; Subban et al., Citation2022). Expanding on this view, this amalgamation of expertise and knowledge will essentially rest on shared values, a combined philosophy that advocates and sponsors inclusivity for all students. Exploring and identifying components that would foster this common way of thinking, is likely to engender greater cohesion within the village, and thereby offer a more equitable educational experience for the student with additional learning needs (Subban et al., Citation2022).

The village mindset

The expression, ‘it takes a village to raise a child’, acknowledges that the responsibility of raising children and young people does not rest with one individual (Mikucka & Rizzi, Citation2016). It implies that communities come together to reduce the strain on just one person, whether that be a parent, teacher, school leader, friend or sibling (Gould, Citation2011; Mikucka & Rizzi, Citation2016). This shared and joint responsibility is apparent especially in the care and nurture of students with disabilities and additional learning needs (Subban et al., Citation2022). In this context, the school is viewed as a social network, providing support and nurture, through an acceptance of this shared responsibility (Scorgie & Forlin, Citation2019). Cultivating this village mindset does involve intentional thinking and more deliberate action (Mikucka & Rizzi, Citation2016; Subban et al., Citation2022), especially since the needs of students with disabilities have often been entrusted to education support, personnel, and paraprofessional staff. Educators and school leaders, who accept this collective responsibility through an embracing of their role within the village, are likely to transform educational provision for all students (Carter & Abawi, Citation2018).

Bronfenbrenner’s (Citation1974) Ecological Systems Theory posits five ecological systems, all of which feature in a nested arrangement within a child’s environment. According to the systems theory, each has an impact but varies with regard to the level or degree of impact (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1974, Citation1977). Relationships and individual performers within each system exert an influence on the child’s life, suggesting that there are multiple roles performed by multiple individuals. The microsystem, the innermost circle around the child, is occupied by the student’s family, the school, and their peers. In the next circle, the exosystem is the child’s extended family, their religious organisations, and their neighbourhood. Bronfenbrenner’s theory goes on to reflect on other influences in the macrosystem and the chronosystem, and utilising sets of interplaying arrows illustrate how each of these systems interact in order to foster contented living. Amalgamating the village mindset into the ecological systems theory allowed us to rethink authentic inclusivity, in which those players in the child’s inner circle become mutually dependent. Alongside previous research in the inclusion space, the Ecological Systems Theory assisted with identifying a range of influential elements which shape inclusivity, within the context of these collective responsibilities. The EST allowed for a consideration of aspects within both the inner and outer environments that would contribute to overall wellbeing.

For the context of this manuscript, we zoom into the microsystem, exploring how the school, the parent, the peer group, the playground, support personnel, and siblings could work together to promote better provision and accommodation of the student with a disability and/or additional learning needs. Bronfenbrenner acknowledges that relationships in the microsystem are mutual (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1977), with the child influencing and being influenced by those around them. Additionally, the dynamics of the microsystem contribute to either a positive or negative context, and could alter the child’s development and their wellbeing (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1979). Nurturing relationships in this context, which are accepting and compassionate, hold great value and will positively impact on the child’s development (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1979). It follows, therefore, that this context, the microsystem or village should function jointly, and interrelatedly, to ensure that children who are raised in this space emerge stronger to then take on life independently. The school should adopt a more collectivist, shared mindset, incorporating intentionally the other role players in the microsystem (Subban et al., Citation2022). Accepting that inclusive education is everyone’s responsibility, through a valuing and support of individual needs is fundamental to the success of all students (Corcoran & Kaneva, Citation2021). Schools which operate as micro-communities, are likely to foster greater academic success among their students (Giangreco, Citation2013). Previous research suggests that in order for inclusion to be successful four key themes should be considered: perception of the student; acceptance; interactions/contacts; and friendships/relationships (Koster et al., Citation2009). These are all the responsibility within the classroom, school and wider community (Koster et al., Citation2009). The current study advances previous research which has examined factors for authentic inclusion within more collectivised settings, adding that shared responsibilities and intentional cooperative relationships between and among stakeholders are fundamental to authentic inclusion. What follows is a rationale reflecting on the need for a structured paradigm to shape and describe elements to facilitate more bona fide inclusionary practices within schools and educational settings. This research suggests that these collaborative and networking relationships may be present, but great organisation and more discrete functioning, engagement and intentionality foster genuine inclusivity.

Rationale for the study

Sparked by the need to examine ideas and thoughts reflecting the collective roles that could support inclusive education, this study was guided by three key assumptions. These fundamental thoughts were embedded within the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (Article 24, Comment 4), which references the need for communities, which reduce discriminatory attitudes and practice, by intentionally promoting the participation, engagement and involvement of all students, particularly students with disabilities (United Nations Organisation, Citation2016). First, the creation of a nurturing environment in a school setting is fundamental to inclusionary programmes. Second, a framework to support inclusive education and its success should be intentionally crafted, avoiding the incidental nature of networking that currently exists. Third, inclusive settings should be accepting of a range of supporting resources, both physical and human, to ensure that programmes function effectively to meet the needs of all students. Ultimately, the study explored elements that could form a framework to advance a more collective mindset, drawing on the efforts of multiple individuals within schools. In order to facilitate this, the study utilised an innovative methodology, drawing on the reflections of prominent researchers in the field with a cumulative 173 years of experience.

The rationale for this study is demonstrated first through the need to engender a nurturing space in which students with diverse learning profiles are appropriately accommodated. Building on this precept, the study acknowledged that schools are dynamic places where change is commonplace and expected (Candipan, Citation2020; Darling-Hammond & Cook-Harvey, Citation2018). Elements such as academic support, social and psychological factors that promote an inclusive mindset, and factors that prompt inclusive practice (Scorgie & Forlin, Citation2019), are all fundamental to the school that operates with the village mindset.

In exploring these fundamental aspects, the report draws together the interdependency of parents, teachers, paraprofessional staff, school leaders, and the wider community to support students with disabilities and/or additional learning needs. Collaborative practice of this nature is acknowledged to be a strength of inclusive schools (Hansen et al., Citation2020). Shared commitment to ensure effective inclusion has long been advocated by researchers, with clear evidence that holding communal responsibilities contributes to a better school experience for students with disabilities and/or additional learning needs (Lyons et al., Citation2016). This report therefore draws together three primary strands. Firstly, the creation of a safe and nurturing environment; secondly, crafting a relevant educational practice model which embraces the village mindset; and finally, offering a structured guideline to intentionally draw on the collaborative relationships within school settings. It must be noted that much of the current study was conducted within developed countries where there are ample resources and funding directed at inclusive learning and teaching initiatives.

Methodology

The study set out to examine elements which would foster authentic inclusion through shared responsibility for students who present with diversity markers and additional learning needs. It was led by the question of what was considered necessary to foster a more collectivised system of accommodating student needs within an educational context. Adopting a qualitative approach, the study drew on the reflections of a group of nine researchers and academics across the world, who were both researchers and practitioners within inclusive education.

This group of collaborating academics involved in teacher and school education, were fundamental to this exploration of elements that could contribute to a more intentional, collective view of inclusive education. This convenient sample included experts in the field of inclusive education from Australia, Canada, Germany, Greece, Italy, and Switzerland. The group had been initially established as an advocacy and research consortium but discovered that shared insights due to productive conversations were beginning to productively impact on practice. Conversations about collective responsibilities regarding inclusive education and the roles of various stakeholders were ongoing, since the group met regularly over a period of 12 months. These meetings offered platforms to different members to share experiences with inclusionary practices and allow the group some time to reflect and contribute to the presentations. In order to draw the conversations together more systematically, so that it would offer support to the field, the team decided to ruminate over their own practices in spoken and written form. Spoken conversations were noted and recorded for reference purposes. Shared written thoughts were documented on an electronic platform collectively. Ultimately, these combined conversations were an envisioning of the collectivist model the team hoped to imitate and exemplify. The underlying focus to guide both thinking, speaking and writing was directed by two aspects: the striving for bona fide inclusionary practices and the focus on how different stakeholders could work together more collectively and intentionally to support these authentic inclusionary practices. The notes and recordings were shared among the team, under password-protected files, on an electronic platform.

Conversations were then supplemented by a formal written reflection on collective responsibilities and roles, which each of the collaborating members constructed, focusing on both specific and broader elements when considering how networks come together to support inclusive education. As a consequence, both spoken dialogue and written reflections formed the basis of this report. Three members of the group reviewed the reflections, drawing on an inductive, thematic approach, informed by protocols suggested by Braun and Clark (Citation2006).

The analytic procedure was directed by several aspects. Given the narrative approach of this study, the revised thematic analysis approach which treats narratives with greater sensitivity and care was the selected analytic approach. This approach is advocated for by renowned thematic analysts, Clark and Braun (Citation2017). Firstly, inductive thematic analysis was facilitated through a thorough reading of each of the reflections, coding and identification, to ensure academic rigour during analysis (Braun & Clarke Citation2006; Clark & Braun, Citation2017; Nowell et al., Citation2017). Secondly, we adopted an appreciative lens, aligning with strengths-based ideas, to tap into the potential of both individuals and organisations, used within the context of this study (Cooperrider, Citation2005). Thirdly, we understood that each reflection offered by the participating researchers was not just unique and engaging but offered a range of insight. (Clark & Braun Citation2017), and in reviewing the data, we wanted to catch these moments of intrigue and insight. Our focus in drawing on Clark and Braun’s (Citation2017) model was to ‘make the argument’ (p. 120), to offer a basis for us to construct and devise a coherent ‘model’ to resolve the gap. As part of this process, the team was keen to locate the research undertaken within existing research in inclusive education, as encouraged by Clark and Braun (Citation2017). This contextualisation of our thinking provided a sturdy platform to offer insights within the broader field of inclusive education, more modestly, being cognisant that much has already been done with regard to collective responsibility and amalgamated efforts within the inclusive educational setting. Following this process, a set of context-appropriate themes were identified by the team of three and verified by the larger group. Here too, the more intuitive and reflexive process of analysis (Clark & Braun, Citation2017) was central to the process. The raw data were fundamental to this identification, and each theme was supported by direct quotes from the reflections (Braun & Clark, Citation2006; Clark & Braun, Citation2017). Themes were reviewed by members of the group, ensuring that major emerging concepts were supported by the data. Themes were also assessed in relation to each other (Lincoln, Citation1985). In the final stage, themes were named according to the main premise. The Results section provides an overview of the main themes and their associated direct quotes. Again, we were directed by the selection of just the pithy and engaging responses of our team (Clark & Braun, Citation2017) which were more concise and revelatory to the broader process. Where appropriate, responses articulated through direct quotes were contextualised for illustrative purposes (Clark & Braun, Citation2017). Following the identification of themes, the group was keen to consider how to draw the elements together, more literally utilising a relevant metaphor. Discussion on this step is discussed in the Implications section.

Study participants

Convenient sampling was used to draw on the expertise of a group of academics involved in research on inclusive education (Subban et al., Citation2022). Each contributor is also a co-author. There were nine academics involved in the collaboration. Their individual details are outlined in . Some of the contributors migrated to more developed countries from the Global South and were therefore able to offer more holistic, and sometimes comparative insights into the discussions and reflections. All contributors to the reflections and dialogue have experience in both the school and higher education sector as both practitioners and researchers. Data was gathered in two formats—the first being the joint, collaborative conversations held over a period of 12 months, and comprising about 6–8 h of discussion. In addition, contributors compiled a reflection, on their interpretation of collective responsibilities within an inclusive educational context. These reflections were formulated independently and emailed to the first two authors, ensuring authentic thoughts and considerations. These personal narratives were then utilised as raw data to inform emerging themes, employing the analytic process outlined above.

Table 1. Contributor profiles.

Results

The objective of this study was to identify some of the elements which are fundamental to schools adopting a more collective mindset when implementing inclusive education. Protocols relating to theme identification were followed (Braun & Clark, Citation2006; Clark & Braun, Citation2017; Lincoln, Citation1985), yielding a set of themes relating to roles, responsibilities and positions of various stakeholders within educational contexts, regarding inclusivity. The following four aspects received unanimous confirmation from the participants, each backed by direct quotations.

Nurturing a community

A common emerging idea throughout participant responses was the need to establish a sense of community, akin to the mentality within a village. Participants were unanimous that a ‘village mindset’ (AR) that involves ‘working together’ (SW) creates an appropriate basis for the collective responsibility with including all students. SW reiterated that ‘working together was critical’, and that ‘building the cooperative work and relationships within the classrooms and across the school were vital’. CSL concurred, adding that ‘the whole school community, must proactively work’ towards this collective mindset, in order to appropriately cater for ‘the needs and interests of all learners’, within an inclusive educational context. It was noted that the ‘contributions of all grownups and class-mates’ (HK) were crucial to developing this kinship within the learning context, that is driven most importantly by a ‘trust in the developmental power of individuals’ (HK). Furthermore, the collective mindset was fostered through ‘collegiality’ (TL) on the part of staff who acknowledged that ‘they were not alone, and also that other classroom teachers throughout the school were embarking on the same journey’ (TL). There was further awareness of the need for ‘small teams’ (US), which ‘supported each other’, especially when a school community ‘includes vulnerable and at-risk learners’ (US). This collective collaboration will allow communities to ‘take advantage of each other’s’ skill set’ (US). Moreover, the general positivity of the ‘village-like school’ (BB) was saluted, through word choices like ‘pure excitement vibrating throughout my classroom’ (BB). It was evident that recognising ‘ourselves collectively, not individually’ (PS) was critical to the positioning of each individual within the ‘village’. In commenting on the adoption of this collective thinking, EA noted that ‘inclusive education … should seek to restructure to provide for a wide range of needs’, so that schools ‘become effective in accommodating students’ (EA).

Empathetic relationships

All participants agreed that empathetic and compassionate relationships, and the maintenance of these connections were fundamental to creating collective responsibility within schools, in order to include all students. It was acknowledged that ‘collaboration was key’ (PS), and that ‘affirming strengths and celebrating the achievements’ (PS) was crucial to establishing strong and supportive relationships, in order to encourage students along within the ‘village’ (PS). BB highlighted a specific relationship in which support was offered as part of this affirmation, which involved ‘working diligently’ (BB) and ‘for a period of time’ to ensure that students ‘experienced success’. Here, it was evident that relationships within the ‘village’ are not incidental but intentional, requiring care and consistent effort. US added that relationships extended to parents, who were also part of the ‘village’, and that the sustenance of these required ‘effective’ engagement, in order to ‘genuinely connect with families’ for the greater good of the student and the community in which they thrived. EA agreed that ‘involving parents in the process to ensure that students received effective support both at school and at home’ increased the chances of success with including all students. It was also evident that the intentional maintenance of relationships resulted in ‘positive changes in my students’ (TL), who were ‘responsive and engaged’ (TL) in the classroom, extending to ‘happy and comfortable’ (TL) within wider settings. HK added that relationships within the ‘society in miniature’, should be ‘engaged’, involve ‘collaborating teachers’, ‘committed parents’, and ‘open-minded students’. It is evident that in order for relationships to succeed, there has to be some collective responsibility, with each contributor to the relationship recognising their role. Moreover, relationships in the village should ‘empower’ (CSL), and ‘voices must be heard’ (CSL), as ‘equal partners’ (CSL) within the school operating as a village. SW strengthened this view that ‘working together was critical’ and that ‘building the cooperative work and relationships … across the school were vital’. AR intimated that a ‘community of peers’ and a ‘safe space’ were also central to the ‘village’, drawing on another vital aspect of empathetic relationships, the idea of safety. Villages are positioned as safe spaces, where every member, through empathetic and nurturing relationships, feels accepted and protected.

Supportive interaction

Another key feature highlighted by the participants was the need to support all members within the inclusive community, which drew on the ‘village’ mentality. AR referenced the ‘authenticity’ of support which offered students sufficient challenge to develop, without being ‘too accommodating’, in order ‘to make learning happen’. Supportive communality is therefore not just about buffering the student, but about creating the right atmosphere for learning and progress. SW added to this by comparing the concerted effort to a music ‘band’, and noting that ‘being part of the band, was what made the sound perfect’, implying that differing roles brought distinctiveness to the whole. In this context, each would require a different level of support. EA strengthened this view by reflecting on his personal experience, supporting an inclusive learning community, observing that teachers in this context, should be sustained to ‘develop a high degree of teaching self-efficacy’, through regular interaction with other members of the community. It was evident that support therefore was required by all members of the village. CSL added that in crafting the support system, ‘professional competencies’, and resources should be prioritised and be ‘optimally coordinated’ to serve all members of the learning and teaching community. HK recalled his personal support of a young student who developed ‘confidence and self-assurance’ by being encouraged within the ‘village’ by his ‘teachers, parents and his … classmates’. The village mindset therefore permeates all interaction and compels a rethinking both individual and collective input. Support expands to ‘attitude’ (TL), ‘honest relationships’ (US), and ‘respect, self-control and growth’ (BB). Finally, support in the village is affirming, ‘adopting a strengths-based mindset’ (PS) in order to promote student advancement.

Targeted teaching

Teaching within the inclusive school is critical to effective inclusion, and often acts as a platform to determine other successes within the inclusive school. EA noted that, in his experience, ‘positive attitudes towards inclusion … strengthened … teaching skills’, implying that adopting the village mindset could transform educational provision. Teaching in this context involved the setting of ‘positive expectations’ (PS) and ‘effective goal setting’ in order to achieve ‘authentic inclusion’ (PS). Teaching embraces more than the academic outcomes in the village, since it is concerned with the more holistic development of learners, with BB acknowledging that teaching is about ‘support’, patiently ‘helping the student understand’ and assisting all students to feel ‘accepted’ and ‘experience success’. Within the inclusive school utilising the village lens, teachers interact ‘collaboratively’ (US), often working ‘in teams’ (US), to collectively cater for ‘vulnerable and at-risk learners’ (US). US added that this form of collaboration, especially among teachers, allows single members to ‘take advantage of each other’s skill set’, and collectively ‘find solutions to the problems that learners face’. TL corroborated, alluding to a personal experience when he observed that teachers who operated more communally found that ‘they were not alone’ and that ‘other classroom teachers were … on the same journey’. This collectivism acts as a support mechanism when including all learners. Reflections from HK implied that it was not just collaborative teaching, but compassionate teaching that led to ‘truly remarkable shifts and gains on the side of students’. Aligned with this, CSL noted that teaching is most effective within an inclusive context when there is evident ‘cooperation’ between ‘different professionals … one of the most crucial aspects’ to serve ‘the needs of all learners’. She extended this by indicating that teaching remains effective when teachers ‘are further developed’, so that they understand that inclusion is a ‘collective endeavour’. Reflections also embedded views that embraced the notion that teaching is cooperative that ‘it took all of the staff’ (SW) and that ‘building cooperative work relationships’ (SW) among teachers was elemental to the success of any inclusive initiative. Adding to this, AR noted that ‘experiential learning’ is the root of authentic inclusion, since ‘creative methods’ maintained ‘teaching continuity’. All in all, it was evident that teaching in the ‘village’ had to be linked to skills, relevant knowledge, and enduring learning. Teachers are called to work in concert, rather than in isolation.

Discussion

This study set out to examine some of the elements associated with the collective responsibilities of varying stakeholders within inclusive school settings, emanating from the view that inclusive schools should adopt a ‘village’ mindset. The work conducted as part of this examination of the ‘village mindset’ within the context of inclusive education builds on work conducted previously which referenced the need for collaboration (Ainscow, Citation2020), equity (Ainscow, Citation2020) and collective responsibility (Katz, Citation2017). The themes that emerged from the findings include nurturing a community; empathetic relationships; supportive interactions; and teaching. For these themes to successfully work, all members of the ‘village’ (including school leaders, teachers, parents, para-professional staff, the community, and curriculum) should be accountable for their involvement. Aligning with Bronfenbrenner’s (Citation1974) Ecological Systems Theory, the results in this report not only focus on the mindset of the interactions at play within the school in order for inclusion to be successful but are also the links between the members of the ‘village’ in the way in which they work together (Ainscow, Citation2020). For example, within the mesosystem (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1974) ‘supportive and compassionate interaction’ is not only an independent function between one of the members of the microsystem (e.g. parents) and the child but can also be a function between members of the microsystem (e.g. between parents and teachers). These themes can be bi-directional, meaning that the student can be influenced by the themes outlined in the results, as well as being capable of changing beliefs and actions of other people too.

The initial theme that emerged from the results was the importance of establishing nurturing communities within the inclusive school, as a collective endeavour. The importance of the collective whole school community was highlighted where working together proactively was key in order for inclusion to be successful. Corcoran and Kaneva (Citation2021) highlighted that for inclusion to be successful, it is everyone’s responsibility to nurture and support students through their learning journey. Furthermore, research acknowledges that that collaborative work in schools is an important aspect of inclusion (Mulholland & O’Connor, Citation2016). In this regard, Shogren et al. (Citation2015) highlighted that ‘inclusion is a “non-negotiable” commitment at the school. Schools emphasized the importance of everyone being on the same page about inclusion, including school staff and families’ (p. 180). Building on this view, this study added that inclusion rests heavily on shared values within the inclusive school, since villages often have great commonality in seeing all individuals succeed and progress. Additionally, nurturing is advanced to accommodate belonging and acceptance, both of which are fundamental values to progress inclusion.

Another key theme that emerged from the results was the establishment of empathetic relationships among participants within the inclusive setting. Developing relationships based on understanding each member of the school (e.g. parents, students, teachers) and working together were critical if the school was to be truly inclusive, allowing students to experience success and celebrate their achievements throughout their development. This supports findings from Carter and Abawi (Citation2018) and Shogren et al. (Citation2015) in that by creating a culture of inclusion, interacting and cooperating as one community is vital. Developing relationships among the members of the ‘village’ were intentional, requiring care and effort rendering the school a safe space (Shogren et al., Citation2015). In encouraging empathetic relationships across inclusive school settings, this study extends the results of previous research by suggesting that these relationships should not just emanate from shared values, but through purposeful development. More opportunities should be created within school settings to promote dialogue, to increase understanding and to work in partnership to advance the educational outcomes of all students, but particularly those with disability. At the moment, most meetings are legally mandated; however, in stepping out of the meeting mode to shared engagement, the responsibility for students with disabilities will rest not just with parents and paraprofessional staff, but with all stakeholders.

The results also found that supportive and compassionate interaction was significant to support student development and to facilitate the meeting of learning outcomes. Students who received appropriate support through a collective initiative often flourished, since they were each uniquely challenged and prompted to succeed. Regular interaction with other community members was also key, supporting the findings of Ainscow (Citation2020), and Carter and Abawi (Citation2018). A strengths-based approach was also found to be an important aspect in order to promote achievement. Research supports the view that academic support, as well as compassionate social and psychological factors, are critical if an inclusive mindset is to be considered, creating a ‘village’ mindset (Marquet, Citation2012; Scorgie & Forlin, Citation2019). Similarly, establishing a productive culture and climate is essential to any inclusive setting (Lewallen et al., Citation2015; Michael et al., Citation2015). In considering supportive interaction, this study reflects on more purposeful networking, allowing students with disabilities to find their spaces in the broader school community. In one example, alluded to earlier, a student with a disability was allowed centre-stage, during a music concert, allowing for his unique talent to shine through, rather than a reductive focus on disability. In these shared interactions, this study advocates for a strengths-based approach (Dweck, Citation2012), which foregrounds unique talents and skills. This acknowledges that all members of the village are ‘differently able’ and would contribute to the village in unique and innovative ways.

Finally, relevant and targeted teaching plays an important role in facilitating collaboration among members of the ‘village’, promoting appropriate development in students. Holding a positive attitude and setting high expectations regarding inclusive practice was found to influence the teaching practices within the schools and classrooms. The success of inclusive teaching goes beyond academic practices and considers other aspects within the school community too, such as social inclusion (Scorgie & Forlin, Citation2019). Embracing each member’s strengths and skills to collaboratively and compassionately work together when teaching inclusively was a relevant find for inclusion to work (Hansen et al., Citation2020; Lyons et al., Citation2016). In this context, joint planning, reflective practice and knowledge sharing appear to be fundamental to accelerating authentic inclusion (Lyons et al., Citation2016). Furthermore, judicious teaching methods, suitable approaches and strategies suited to student needs created greater opportunities for success among students with additional learning needs (Hansen et al., Citation2020). Extending the thinking and findings of these investigations, the current research notes that teaching is not confined to the classroom within the village and that inclusive settings utilise all contexts as spaces of development and growth. Teaching implies assessment and evaluation, and within the school setting, students with disability are likely to not just require meaningful modification to their work programmes but the methods selected should be inclusive of their needs. These methods cannot be devised without the input of other stakeholders, including students. This work acknowledges the motto of ‘nothing for us, without us’, first coined in 1993 by South African Disability Advocates, Michael Masutha and William Rowland. This contextualises the need for ‘relevant and targeted’ teaching which draws on multiple voices to advance equitable educational provision.

Implications

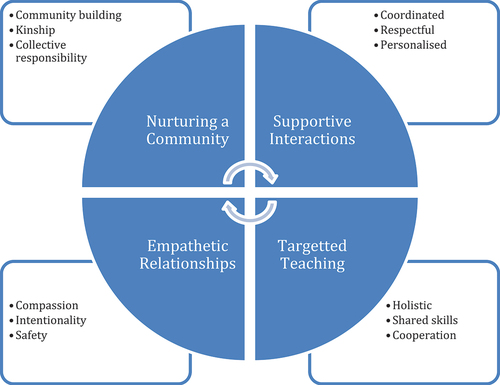

In reflecting on the discussions and individual contributions by the team, it was evident that all were sensitive to a practice-oriented framework which would support this collective awareness of needs within inclusive schools. The team was keen to consider an appreciative, nurturing framework that would articulate their thoughts, and which could ideally illustrate the care and support which should be a fundamental aspect of inclusive settings which adopted collective responsibility for students with disability. Subsequently, the varying thematic elements embraced nurturing communities, empathetic relationships, supportive interaction and targeted teaching, all of which were conceptually framed by Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory. As a consequence, we zoomed into the inner circle (the microsystem), according to this framework, and understood this to be the ‘village’ where the different elements perceived as necessary for inclusive education were positioned. In this inner circle, all members accept collective responsibility and are willing to participate in collective action. The village mindset for inclusivity prompt all elements to function collectively, holding up a common inclusive philosophy. As Carter and Abawi (Citation2018) found, one of the key aspects to a successful inclusive school is for the entire school staff to embrace an inclusive philosophical view. captures this visually, and it is anticipated that it will likely to facilitate a more collective view of inclusion.

Conclusion

This study was led by the need to explore and identify some of the elements which are fundamental to schools adopting a more collective mindset when implementing inclusive education. The study extended other research in the field, by reflecting on this collective collaborative mindset and examining a more intentional structured approach by all stakeholders who share collective responsibilities for inclusive education. Adopting a qualitative and appreciative lens, the investigations drew on the reflections of a group of academic scholars who shared their insights over several months on the ingredients involved with adopting a collectivised and combined mindset within inclusive learning contexts. Thematic analysis of their reflections facilitated by Clark and Braun’s (Citation2017) process yielded four key ideas, which were then crafted into an easy-to-remember acronym, NEST.

The initial aspect related to the need for a nurturing learning community. With the school being viewed as a microcosm in which students were positioned to thrive, nurturing became fundamental, with each contributor not just adding on their strengths to the inclusive context, but by building on and amplifying the strengths of others around them. Secondly, empathetic relations were viewed as crucial to the success of shared, collective responsibilities to create inclusive learning contexts. Here, it was acknowledged that relationship building was not incidental but intentional, with a greater need to empower and offer voices and platforms to those who are often marginalised. It was acknowledged that schools were communal spaces, were safety was paramount—in this context, nurturing relationships were fundamental to the success of the community (village). Thirdly, the data revealed the need for supportive interaction. In this context, interaction was viewed through a strengths-based lens, with the acknowledgement that some members of the village requiring more support and care than others. This supportive interaction was again organised and concerted, to ensure both collective and personalised support was in place to optimise growth, development and care. Finally, the reflections from participants yielded the view that targeted teaching was axiomatic to the inclusive learning context, with teaching being view much more broadly. Teaching was occurring in every teaching and learning moment across the educational setting and was reiterated as a shared responsibility aming educators, paraprofessional staff, school leaders, other school staff (canteen, bus coordinators, etc.), parents and peers. Teaching moments were those which fostered success, were marked by compassion and patience, and developed as a combined, mutually favoured exercise. Again, participants referenced the intentionality of this endeavour, with cooperation between and among all stakeholders being central to the success of inclusive education.

Ultimately, inclusive education is both highly affirming and socially just. In this regard, all who are involved in its implementation are morally and justly bound to work within the best context to facilitate success for students with diverse learning profiles.

Suggestions for further study

It is hoped that studies within inclusive education would focus on student outcomes, student progress and student wellbeing, when examined within the school operating as a village. The NEST framework positioned above will require greater empirical support, especially when implemented within settings where there are fewer resources. These settings will include more culturally specific settings, such as those in the Global South, where collectivised thinking is already embedded into educational interaction.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ainscow, M. (2020). Promoting inclusion and equity in education: Lessons from international experiences. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 6(1), 7–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/20020317.2020.1729587

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1974). Developmental research, public policy, and the ecology of childhood. Child Development, 45(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.2307/1127743

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 32(7), 513. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development : Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press

- Candipan, J. (2020). Choosing schools in changing places: Examining school enrollment in gentrifying neighborhoods. Sociology of Education, 93(3), 215–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040720910128

- Carter, S., & Abawi, L. (2018). Leadership, inclusion, and quality education for all. Australasian Journal of Special & Inclusive Education, 42(1), 49–64. https://doi.org/10.1017/jsi.2018.5

- Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2017). Thematic analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(3), 297–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1262613

- Cooperrider, D. (2005). Appreciative inquiry : A positive revolution in change (1st ed.). Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Incorporated

- Corcoran, S. L., & Kaneva, D. (2021). Developing inclusive communities: Understanding the experiences of education of learners of English as an additional language in England and street-connected children in Kenya. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 27(11), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2021.1886348

- Darling-Hammond, L., & Cook-Harvey, C. (2018). Educating the Whole Child: Improving school climate to support Student success. Learning Policy Institute.

- Dweck, C. S. (2012). Mindset : How you can fulfill your potential. Robinson.

- Giangreco, M. F. (2013). Teacher assistant supports in inclusive schools: Research, practices and alternatives. Australasian Journal of Special Education, 37(2), 93–106. https://doi.org/10.1017/jse.2013.1

- Gould, J. A. (2011). Does it really take a village to raise a child (or just a parent?): An examination of the relationship between the members of the residence of a middle-school student and the student’s satisfaction with school. Education, 132(1), 28–37

- Hansen, J. H., Carrington, S., Jensen, C. R., Molbæk, M., & Secher Schmidt, M. C. (2020, January). The collaborative practice of inclusion and exclusion. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 6(1), 47–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/20020317.2020.1730112

- Howley, C., Howley, A., & Telfer, D. (2017). National provisions for certification and professional preparation in Low-Incidence sensory disabilities: A 50-state study. American Annals of the Deaf, 162(3), 277–294. https://doi.org/10.1353/aad.2017.0026

- Katz, J. (2017). Toward a vision of inclusive learning communities: IT takes a village. In Working With families for inclusive education (Vol. 10, pp. 183–201). Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1479-363620170000010018

- Koster, M., Nakken, H., Pijl, S. J., & van Houten, E. (2009). Being part of the peer group: A literature study focusing on the social dimension of inclusion in education. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 13(2), 117–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110701284680

- Lewallen, T. C., Hunt, H., Potts-Datema, W., Zaza, S., & Giles, W. (2015). The whole school, whole community, whole child model: A new approach for improving educational attainment and healthy development for students. The Journal of School Health, 85(11), 729–739. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12310

- Lincoln, Y. S. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage Publications

- Lyons, W. E., Thompson, S. A., & Timmons, V. (2016). ‘We are inclusive. We are a team. Let’s just do it’: Commitment, collective efficacy, and agency in four inclusive schools. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 20(8), 889–907. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2015.1122841

- Marquet, L. D. (2012). Turn the ship around! How to create leadership at every level (1st ed.). Greenleaf Book Group Press

- Michael, S. L., Merlo, C. L., Basch, C. E., Wentzel, K. R., & Wechsler, H. (2015). Critical connections: Health and academics. The Journal of School Health, 85(11), 740–758. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12309

- Mikucka, M., & Rizzi, E. (2016). Does it take a village to raise a child? The buffering effect of relationships with relatives for parental life satisfaction. Demographic Research, 34, 943–994. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2016.34.34

- Mulholland, M., & O’Connor, U. (2016). Collaborative classroom practice for inclusion: Perspectives of classroom teachers and learning support/resource teachers. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 20(10), 1070–1083. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2016.1145266

- Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., & Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847

- Scorgie, K., & Forlin, C. (2019). Promoting social inclusion: Co-creating environments that foster equity and belonging. (Series Editor Chris Forlin, ed. Vol. 13). Emerald

- Shogren, K., McCart, A., Lyon, K., & Sailor, W. (2015). All means all: Building knowledge for inclusive schoolwide transformation. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 40(3), 173–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/1540796915586191

- Sobsey, D. (2017). Rethinking individual education plans: Searching for a Better Way. In working with families for inclusive education (Vol. 10, pp. 203–207). Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1479-363620170000010020

- Specht, J., McGhie-Richmond, D., Loreman, T., Mirenda, P., Bennett, S., Gallagher, T., Young, G., Metsala, J., Aylward, L., Katz, J., Lyons, W., Thompson, S., & Cloutier, S. (2016). Teaching in inclusive classrooms: Efficacy and beliefs of Canadian preservice teachers. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 20(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2015.1059501

- Subban, P., Bradford, B., Sharma, U., Loreman, T., Avramidis, E., Kullmann, H., Sahli Lozano, C., Romano, A., & Woodcock, S. (2022). Does it really take a village to raise a child? Reflections on the need for collective responsibility in inclusive education. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 38(2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2022.2059632

- Subban, P., & Sharma, U. (2021). Supporting inclusive education benefits us all. The Sydney morning herald. https://www.smh.com.au/education/supporting-inclusive-education-benefits-us-all-20210219-p57439.html

- United Nations Organisation. (2016). Youth with disabilities. Accessed online from: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/youth-with-disabilities.html