ABSTRACT

Young people who have committed a sexual offence present unique and serious challenges to the criminal justice systems of Australia and New Zealand. To understand the current state of existing literature, we systematically collated and critically appraised studies using narrative synthesis, examining the recidivism outcomes of young people who have committed a sexual offence and received treatment. Eight studies were identified utilising a sample of 1528 young people. Recidivism was higher among participants who did not complete treatment, compared to those who completed treatment, but highest in those who commenced but subsequently “dropped out”. Our findings highlight a need for more Australian and New Zealand research addressing the recidivism rates post-treatment. More specifically, three future research directives are identified: the need for methodologically strong research, identification of recidivism outcomes for Indigenous young people, and the need for qualitative research to explore the profiles of young people who terminate treatment.

PRACTICE IMPACT STATEMENT

Our findings identified gaps in three key areas in current research within the Australian and New Zealand context: (1) a need for more methodologically strong evaluative research, (2) identification of recidivism outcomes for Indigenous young people, and (3) qualitative research to explore the profiles of young people who terminate treatment to compliment current research findings.

Introduction

Sexual offences by young people (aged 10–17 years) pose a serious challenge for criminal justice systems around the world, including in Australia and New Zealand. Such offences by young people also present significant harm and costs to victims and their families, the community, and the criminal justice system (Keogh, Citation2012). Before the 1980s, sexual offending by young people was considered to be an outcome of adolescents’ sexual experimentation and curiosity (Knopp, Citation1985; Oxnam & Vess, Citation2008). This resulted in research on young people who had committed a sexual offence being largely ignored (Kim et al., Citation2016). However, since the 1980s, particularly in North America, attention shifted to exploring the treatment needs of young people who had committed a sexual offence, their recidivism outcomes, and understanding the factors that prevent reoffending. Young people are often disadvantaged and vulnerable, yet they have been considered untreatable, at great risk of reoffending and a threat to public safety (Kim et al., Citation2016). Given the significant adverse impacts on victims, life-long negative outcomes for the offender, and the resultant community anger that sexual offences arouses, it is of vital importance that a young person who has committed a sexual offence receives appropriate treatment.

There is a dearth of research into the effectiveness of treatment programmes and associated recidivism outcomes for young people who have committed a sexual offence in Australia and New Zealand, resulting in Australian policymakers and practitioners utilising the available international research for guidance (Adams et al., Citation2020). Researchers in North America have conducted a number of systematic reviews and meta-analyses on the post-treatment effects for young people who have committed a sexual offence (see ) (Caldwell, Citation2016; Hanson et al., Citation2002; Kettrey & Lipsey, Citation2018; Kim et al., Citation2016; Reitzel & Carbonell, Citation2006; Walker et al., Citation2004; Winokur et al., Citation2006). At a group level, the results are encouraging and indicate that specialist treatment designed for young people can be effective in reducing sexual recidivism.

Table 1. Summary of previous systematic reviews and meta-analytical studies conducted between 2002 and 2018.

Hanson et al. (Citation2002) reported a positive, albeit small, effect for the treatment cohort in comparison to untreated offenders, putting cognitive–behavioural practices at the forefront of programmes internationally. A similar sentiment was communicated by Schmucker and Lösel (Citation2008) in their review of treatment programmes, although arguing surgical castration and hormonal medication demonstrated the most significant findings. Such an approach is less common in contemporary practices, in favour of therapeutic and psychosocial interventions, particularly when addressing sexually harmful behaviours by young people. Some meta-analytic reviews have focused specifically on young people, suggesting they are less likely to sexually reoffend when engaging in either cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) or multi-systemic therapy (MST) (Kettrey & Lipsey, Citation2018; Reitzel & Carbonell, Citation2006; Walker et al., Citation2004; Winokur et al., Citation2006).

A common factor amongst these reviews is the poor methodological designs utilised which questions the efficacy of treatment for people who have committed a sexual offence. There is a requirement for research to show that the treatment under investigation has an effect beyond what could be explained by confounding variables, such as cohort effects or other interventions (Henggeler et al., Citation1994). Lösel and Schmucker’s (Citation2005) review utilised a large cohort of studies (k = 69), although 67% of studies did not achieve the minimum standard to conclude “What Works” in offender treatment and over half reported author affiliation. The methodological approach to evaluating treatment programmes for people who have committed a sexual offence has become a contentious topic within the criminological literature. Some scholars have argued for employing high-quality randomised control trials designs, described as the “gold standard” (Quinsey et al., Citation1993; Rice & Harris, Citation2003; Schmucker & Lösel, Citation2015). However, the logistic, legal and ethical challenges associated with conducting high quality studies on sensitive criminal and social issues have been noted (Långström et al., Citation2013; Marshall & Marshall, Citation2007; Marshall & Marshall, Citation2008, Citation2010). It is considered unethical and a threat to the community not to provide an individual with treatment for problematic sexualised behaviours to advance knowledge on treatment efficacy.

However, recidivism information for young people who have attended treatment programmes from the United States and Canada are not readily transferable to the young offender cohorts in Australia and New Zealand because of their distinctive, culturally diverse populations and unique geographical and cultural features. Furthermore, the populations of offenders differ. For example, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia have over 200 cultural and linguistic groups dispersed across 7.7 million km2 of land (Smallbone & Rayment-McHugh, Citation2013). Young people who have committed a sexual offence in New Zealand have also been described as a heterogenous population, therefore the one-size-fits-all approach has proved to be ineffective (Lambie & Seymour, Citation2006). Furthermore, young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and Māori people (“Indigenous”) are vastly over-represented in Australia’s and New Zealand’s criminal justice systems across most offence types (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Citation2020, Citation2021; Ministry of Justice, Citation2021). The practices of colonisation caused the dispossession of land, forced removal of children from families, and the banning of cultural practices, resulted in inter-generational trauma, modern disadvantages and an over-representation in the criminal justice system (Cunneen, Citation2014; La Macchia, Citation2016).

Indigenous young people also experience higher rates of structural disadvantage, discrimination and systemic vulnerabilities, such as familial instability, antisocial attitudes and incarceration, unsociable peers, poor school attendance and engagement, and low socioeconomic status (Adams et al., Citation2020; Kenny & Lennings, Citation2007; White, Citation2015). An offender’s social and cultural environment adds a unique dimension to identifying appropriate treatment. Successful interventions cannot be achieved without consideration of these many social disadvantages, thus why practitioners seek programmes more aligned to unique cultural differences. Commonly used treatment methods include Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) and multi-systemic therapy (MST). While there is limited research on CBT’s effectiveness for young people who have committed a sexual offence (Dopp et al., Citation2015), more than 2000 studies have demonstrated its positive effects for treating psychiatric disorders, psychological problems and medical problems with a psychiatric component (Beck Institute, Citation2021). However, many studies have reported positive effects when administering multi-systemic therapy to young people and adults who have committed a sexual offence (Borduin et al., Citation2009; Fanniff & Becker, Citation2006; Henggeler, Citation2012; Huey et al., Citation2000). Macgregor (Citation2008) argued that CBT has shown to be appropriate for non-Indigenous people but not with other culturally and socially diverse groups. Nevertheless, in the absence of consolidated evidence of culturally appropriate treatment, practitioners in Australia and New Zealand have had no choice but to employ non-Indigenous traditional treatment methods.

Few young people commit sexual offences, these crimes have continued to remain steady over the years in Australia and New Zealand (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Citation2022; Ministry of Justice, Citation2022) but the results can be devastating. Therefore, the investigation continues, despite much debate over the last three decades, as how to address problematic sexualised behaviours and prevent young people from reoffending (Harkins & Beech, Citation2007; Harrison et al., Citation2020; Rice & Harris, Citation2003). The present review, therefore, aims to consolidate the available literature providing post-treatment outcomes for young people who have committed a sexual offence in Australia and New Zealand and identify future directions for this body of knowledge.

The present study

Our aim for this systematic review was to consolidate and critically appraise existing research in Australia and New Zealand regarding young people who have attended psychological treatment for a sexual offence and their post-treatment recidivism outcomes. We used a descriptive analytic method to collate and capture demographic, treatment and recidivism data, and summarised and reported the findings using a narrative synthesis approach (Popay et al., Citation2006). This type of methodological approach has become a valued strategy for synthesising and understanding a diverse type of available literature (Farrington, Citation2003; Oremus et al., Citation2012; Uman, Citation2011). A secondary aim was to understand what factors prevent recidivism and identify opportunities for future research directions.

Methods

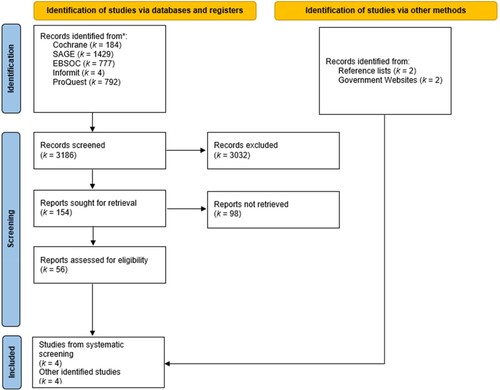

This systematic review was reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (Page et al., Citation2021) where appropriate.

Eligibility criteria

Studies required the following characteristics to be eligible to be included in this review:

Study of young people who had committed a sexual offence. Participants had to be either charged with, or convicted of, a sexual offence. There were no limitations on the type of sexual offence perpetrated, with inclusion of both contact (sexual penetration without consent, indecent assault) and non-contact offences (child exploitation material, voyeurism, exhibitionism).

Age of young people. Young people between the ages of 10 and 17 years, at the time of treatment, were eligible for inclusion. While it is acknowledged the (World Health Organization, Citation2022) and the United Nations (Citation2022) defines a young person up to the age of 24 years, the age range of 10–17 years reflects the legal terminology of a young person in Australia and New Zealand.

Psychological-based treatment. No restrictions were imposed on the type of psychological treatment offered. However, studies were excluded if they included a sub-sample of participants who received additional pharmaceutical or medical interventions.

Measure of recidivism as outcome. Recidivism had to be included as a dependent variable. Recidivism was defined as sexual and/or non-sexual re-offending and includes formal legal measures: probationary breach, parole breach, re-arrest, or re-conviction; and self-reported data regarding undetected criminal involvement.

Research Design. While it is foremost acknowledged that recidivism outcome studies should include a comparative group of equivalence, no studies were rejected due to methodological shortcomings. This is a result of the ethical and legal issues that arise when treatment is withheld from a sample of people who have committed a sexual offence for the benefit of research (Långström et al., Citation2013; Marshall & Marshall, Citation2007).

Country of origin. This study is designed to assess the recidivism outcomes of young people who have committed a sexual offence and received treatment in Australia and New Zealand. Therefore, studies were excluded if treatment was delivered outside the jurisdictional scope of Australia and New Zealand.

Publication type. Studies were sought from peer-reviewed journals and grey literature, which included government reports and theses. We aimed to provide a comprehensive review of the literature; therefore, restrictions were not imposed on publication dates.

Data sources and search strategy

The systematic search process was designed to capture published and unpublished (grey literature) recidivism outcome studies from a range of sources. To achieve this, we engaged with a librarian specialising in the development of search processes for systematic reviews. Three meetings were held with the librarian to (1) create search terms to effectively locate relevant literature (2) select appropriate databases to run the search (3) conduct pre-testing of the search terms and refine the process. The search strategy evolved using the PICO framework (population, intervention, comparison and outcome) (Methley et al., Citation2014). First, the search terms from the search strategy were employed into five peer-reviewed databases: Cochrane Library, ProQuest, Informit, EBSCO and SAGE. Search terms included terms such as “young”, “sex”, “offender”, “treatment”, “outcome”, “recidivism”.

These databases included numerous journals relating to fields of psychology, criminology and sociology. Second, reference lists from studies later included in the review were examined for additional studies. Third, unpublished literature was retrieved by hand searching government websites and Dissertations and Theses International. Finally, to ensure a comprehensive literature base, an informal search of Google Scholar was conducted using keywords from the literature search strategy.

Study selection

The final search results were exported into EndNote. A total of 3191 studies were identified and subject to a three-phase screening process (). As part of the first screening phase, duplicates were deleted and titles were screened for relevance, which resulted in a sub-sample of 159 studies. Of these 159, 98 studies failed the second abstract screening phase as they did not meet the pre-determined inclusion criteria. The final screening phase of full-text screening resulted in the rejection of 53 studies. It was common for studies to be excluded from the present review as they did not specifically address a sexual offence, but rather general offending behaviours that included samples of people who had a sexual offence. In other cases, studies were excluded as they were outside the jurisdictional limits of this review.

Eight studies providing recidivism outcomes met the inclusion requirements for this review. The studies collated data published between 1990 and 2012. Five studies were from Australia [ID#: 1, 2, 3, 4, 6] and three New Zealand [5, 7, 8]; however, one New Zealand study [7] reported on the findings of three community-based programmes delivered in three locations. As noted, systematic reviews restricting data to exclusively published studies can yield significant results and higher effects sizes more often than those including unpublished studies, which has been termed the “file drawer effect” (Rosenthal, Citation1979). This systematic review accessed data from studies published in peer-reviewed journals [1, 2, 3, 4, 8] as well as reports [5, 6] and a PhD thesis [7].

Data extraction and data items

A full-text review of each study was conducted by the first author. Using a data extraction form developed specifically for the present study, data were extracted on a broad range of variables from each study (see Supplementary Material for the coding sheet). All data extracted were entered into the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS). These study variables (N = 272) were coded for descriptive purposes and independently reviewed by the second author (NG). Any discrepancies were then adjudicated by the third author (SR). A broad range of variables have been coded, and categorised into four key themes: (i) general study characteristics, (ii) offender and victim characteristics, (iii) treatment characteristics and (iv) post-treatment recidivism information. Descriptive statistics were used to provide a summary of the studies.

Quality assessment

The Maryland Scientific Methods Scale (SMS) was used to assess the methodological quality of studies included in the review. The SMS is a 5-point scale where each individual study included in the review is ranked based on the strength of its overall internal validity. According to Sherman et al. (Citation1998), the rating of SMS is interpreted as follows:

Level 1: No control or comparison group. Only treatment group data is reported. Comparisons are made between pre-treatment and post-treatment variables, or a correlation between the treatment programme and a measure of crime at one point in time.

Level 2: Non-equivalent comparison group. Differences on relevant variables effecting recidivism arise from comparative groups consisting of treatment dropouts or young people who refuse to engage in treatment.

Level 3: Incidental assignment but equivalent control group. No serious doubts that assignment resulted in equivalent groups, or sound statistical control of potential differences.

Level 4: Matching or statistical control procedures. Equivalence between the treatment and control group is attained by matching theoretically relevant variables effecting recidivism or propensity score techniques.

Level 5: Random assignment of treated and untreated participants. Non-selective groups are formed by full randomisation of young people into either the treatment or control group.

Overall, the methodological quality of studies reviewed was poor. One of the included studies [6] attained a Level 3, the minimum level for determining “what works”. Four studies [1, 3, 4, 5] achieved a SMS Level 2 as they unsuccessfully accounted for differences between the treatment and comparison groups. The remaining three studies [2, 7, 8] attained a SMS Level 1 as they reported no comparable group, only measuring the treatment results before and after a follow-up period.

Results

provides a summary of study, participant and treatment characteristics, the details of which are reported in the following sections.

Table 2. Summary of study, participant and treatment characteristics.

Study characteristics

The systematic screening process and identification of grey literature resulted in the identification of eight studies from Australia [1, 2, 3, 6, 8] and New Zealand [4, 5, 7]. Of these eight studies, a total of nine treatment programmes were delivered to 10 different sample groups across seven locations. Due to the lag between treatment and outcomes that is required in follow-up studies, the time of treatment implementation was often considerably earlier. Data from the studies were collected over a 22-year period from 1990 to 2012, with publication dates ranging from 1998 to 2022.

Participant characteristics

The sample size of young people (participating in both Treatment and Comparison Groups) in the eight studies included in this review was 1528. As noted in , seven studies [1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8] reported the number of young people who received treatment for a sexual offence, representing 41.87% (n = 582) of the combined sample in this review study. The remaining participants (57.64%, n = 792) [1, 4, 5, 6] formed the comparison group.Footnote1 The comparison group comprised treatment “dropouts” (11.85%, n = 181) [4, 7] and treatment “refusers” (39.46%, n = 603) [1, 4, 7]. Indigenous young people comprised a quarter of the total sample (25.59%; n = 391), where they identified as either Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander (10.67%, n = 163) [1, 2, 8] or Māori or Pacific Islander (14.92%, n = 228) [4, 5].

Males comprised the majority of the sample in this review (98.30%; n = 1502). Information on participant age could not be extracted with sufficient certitude due to the varying reporting styles of individual studies. Nonetheless, the mean age of participants 15.26 years (SD = .75) [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]. Visual interpretation of data suggested participants age generally ranged between 12 and 16 years. Age was defined as either age at time of referral or commencing treatment [2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8] or index offence [1, 6]. Only two studies reported on the use of a risk assessment tool [5, 8], however, young people were reported to be either medium or high-risk of reoffending in studies [4, 5, 7, 8]. Four studies did not report on the risk of the young people [1, 2, 3, 6].

Of those studies reporting the information [3, 4, 5, 6, 7], young people victimised both males and females. It was most common for young people to victimise other young people or children [3, 5, 6, 7], with only one study reporting the victimisation of young people and adults [4]. Four studies [5, 6, 7, 8] reported the relationship between the young person and victim to be intra-familial, or known, but not related. Of these four studies, three also included young people who victimised strangers [5, 6, 7]. Young people were receiving treatment for contact and non-contact offences [1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8], with only one study reporting exclusively on contact offenders [5]. Penetrative sexual assault was the most common serious offence in all studies.

Treatment characteristics

All eight studies included in this review provided information on the type of primary intervention used to reduce or cease the risk of future problematic sexualised behaviours for young people. While there may be various interpretations of the therapeutic intervention used within studies, we have reported the names of the specific intervention as mentioned by the authors in each study included in this review. The most common therapeutic intervention was multi-systemic therapy [2, 3, 6] (see for an overview of frequency). One study reported the use of cognitive–behavioural therapy [5], one used adventure therapy and counselling [7] and a final study stated participants attended a “psychological service” [1]. Three studies [2, 5, 7] reported culturally sensitive components of the programme that were introduced for those participants identifying with an Indigenous cultural heritage. However, one study stated some non-Māori participants engaged in cultural sessions [5].

Treatment was predominately delivered in the community [1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8], with only one programme reporting on young people who received a therapeutic intervention within a residential facility [5]. Entry pathways into treatment for those studies reporting the information [4, 6, 7] were largely reported as voluntary even when people had referred through an official process from courts or police; others were self-referred. Two programmes [5, 8] accepted young people on both a referred and mandated basis, but young people needed to meet certain requirements. Furthermore, it was common for treatment to be delivered in an individualised format with additional group therapy [3, 4, 5, 6, 7]. Only two programmes reported the use of individual treatment [2, 8] as the exclusive method of therapeutic intervention. Five programmes [2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8] reported that the treatment included the young person’s family.

Data on treatment length were presented in numerous formats (days, months, or years) and this information was converted from the original format into days. The mean length of treatment for all participants across studies providing the information [2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8] was 500.54 days (SD = 136). One study did not report treatment length [1] and another study stated participants generally spent between 12 and 18 months in the programme [5].

Post-treatment recidivism

Included studies also provided post-treatment information on recidivism reported to the criminal justice system during a prescribed follow-up period. All studies reported on sexual offending occurring during the post-treatment recidivism period. Six studies included additional information on violent reoffending [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7,] and four on non-sexual or non-violent reoffending [2, 3, 6, 7] occurring during the prescribed period. There were different definitions used to interpret recidivism information including arrest, charge and conviction. This information was also retrieved from varying official sources. Police were the most common source of information. Three studies used police records as the exclusive source of recidivism information [2, 3, 4], followed by a government agency [5, 8], police and government agency [6, 7], and police and courts [1]. None of the included studies provided self-reported information on recidivism. All studies nominated a follow-up period post-treatment. There were large variances in the duration of follow-up time within the individual studies, ranging from 5 to 3960 days. The overall mean follow-up period for all studies was 3.73 years (SD = .98) ranging from 2 to 4.58 years.

All studies also provided information on sexual reoffending following treatment. Sexual recidivistic behaviours were heterogeneous and included, but were not limited to, offences such as rape, attempted rape, sexual assault, voyeurism and indecent exposure. As summarised in , the percentage of sexual recidivism was lower for those young people who completed treatment compared with the comparison groups. One study [1] reported a marginally higher percentage of sexual recidivism in the treatment group. However, the comparison group included young people who were convicted of a sexual offence prior to the establishment of the treatment service. Therefore, young people may have received treatment elsewhere.

Table 3. Summary of descriptive data on post-treatment recidivism rates.

Four studies provided information on violent or serious reoffending that young people had committed [2, 3, 4, 7]. Violent or serious reoffending encompasses a range of behaviours, including actual or threatened violence against a person with an element of intent, such as assault, robbery, abduction, extortion and break-and-enter of a dwelling with violence or threats, and going armed to cause fear. In comparison to sexual recidivism between the treatment and comparison groups, larger differences were observed for violent and serious recidivism. Indicating the treatment cohort were less likely to recidivate in a violent or serious manner.

Other general reoffending include theft, fraud, dangerous driving, property damage, illicit drug offences, public order offences and break and enter. One Australian study excluded traffic and vehicle regulatory offences as an action against the Traffic Act rather than the Criminal Code [2]. Another Australian study provided traffic offence information [1], however, this information was excluded from the review. The three evaluations conducted in New Zealand [7] included traffic breaches in the non-sexual and non-violent category. Information on this type of offending was limited to five studies [1, 2, 3, 6, 7]. Although general recidivism was higher than sexual and violent recidivism, there were lower rates of general recidivism observed amongst those young people who received treatment. It is important to note here, one study [1] included sexual and other types of offences within an analysis separate to sexual offending.

Treatment programme dropouts and refusers

It is important to understand the reasoning behind why some young people in the comparison group did not engage in the therapeutic process as this may contribute, or provide context, around their reoffending behaviours. Therefore, we decided to explore the profiles of young people in the comparison group by extracting data from each study, which resulted in the development of two groups: treatment “dropouts” and treatment “refusers”.

Young people were categorised as dropouts when studies stated that this cohort initially engaged in the therapeutic process but failed to successfully complete treatment because of disengagement. The term “refuser” encompassed young people who were assessed for the treatment programme but did not engage. Reasons for this included: actual refusals, although included young people who were referred to a different programme and young people who had no contact with the service. Unfortunately, this information was limited and did not discuss whether the young people engaged with respective programmes to which a case for referral was made. Due to limited information on recidivistic behaviours, we focused on sexual offending and collapsed data on violent and other offences into one category termed “non-sexual” reoffending.

provides an overview of recidivism information for those young people who dropped out or refused to engage with the respective treatment programmes in comparison to those young people who were successful in their treatment engagement. It is evident from these findings that young people are more likely to reoffend if they do not complete treatment. If young people did not complete treatment, they were more likely to sexually reoffend when compared to the treatment cohort. Young people were more likely to sexually reoffend if they dropped out of treatment as opposed to refusing treatment. Consistent findings were reported regarding general recidivism.

Table 4. Summary of descriptive data on recidivism rates for treatment completers, dropouts and refusers.

Recidivism by Indigenous young people

Five studies provided information on the number of Indigenous young people in their respective study sample [1, 2, 3, 5, 7]. However, only three studies differentiated recidivism data between Indigenous young people and non-Indigenous young people [1, 2, 3]. Of these, one study [1] provided the overall rate of sexual recidivism (treatment and comparison group) for Indigenous young people and non-Indigenous young people. Here, Indigenous young people were more likely to sexually reoffend than non-Indigenous young people. Of the two remaining studies, one reported higher rates of sexual recidivism by Indigenous young people [3], while the other [2] was equally effective for Indigenous and non-Indigenous young people in reducing sexual recidivism. Treatment for these two studies [2, 3] was less effective for Indigenous young people in preventing violent and general offending (see ). These data are limited to the small sample sizes of Indigenous young people within studies presenting the recidivism information separate from non-Indigenous young people.

Table 5. Summary of descriptive data on recidivism by indigenous young people and non-Indigenous young people.

Discussion

The present review systematically synthesised and critically appraised the existing research in Australia and New Zealand regarding young people who have attended treatment for sexual offending and their post-treatment recidivism outcomes. It is important to capture and reflect on the available evidence to provide a foundation for future research directives. Furthermore, it is imperative to understand what is known in Australia and New Zealand given the significant harms sexual offences have on the victim, their families and the community. Consistent with international literature, our review suggested that young people are less likely to reoffend after completing treatment (Hanson et al., Citation2002; Kettrey & Lipsey, Citation2018; Lösel & Schmucker, Citation2005; Reitzel & Carbonell, Citation2006; Walker et al., Citation2004; Winokur et al., Citation2006). These findings provide a sound outcome particularly given Australia’s geographical vastness and the difficulties this may impose on a young person’s ability to receive or attend treatment.

Interestingly, our review found young people who dropped out of treatment were more likely to reoffend in a sexual and non-sexual manner when compared to those who completed treatment. This finding remained consistent even when comparing the sexual recidivism rates of treatment dropouts to those who did not engage in the therapeutic process. However, we are unable to rule out whether “refusers” engaged in treatment elsewhere. In a meta-analytic review of treatment programmes for sexual offenders, Hanson et al. (Citation2002) noted pre-existing characteristics associated with recidivism as a potential factor for treatment termination. Impulsivity and anti-sociality have also been observed as predictors of poor therapeutic engagement (Smallbone et al., Citation2009). Whilst the high recidivism rates of treatment dropouts are an important finding within the Australian and New Zealand context, our investigation into this was restricted to the dearth of information provided.

Recidivism rates of Indigenous participants was also limited within the studies of this review. The Australian and New Zealand criminal justice system is over-represented by Indigenous young people (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Citation2020; Ministry of Justice, Citation2020). However, academic contributions to understanding the post-treatment recidivism rates of Indigenous young people in this review was limited. Providing the recidivism rates for Indigenous and non-Indigenous young people facilitates the effects of treatment for both cohorts. Notwithstanding this, the review has achieved the desired outcome of consolidating the available research and providing future research directions.

Identified gaps and directions for future research

A major benefit of conducting a systematic review is that it helps to identify gaps in the available literature and providing opportunities for future research direction in the area under investigation. Our review achieves this by identifying three key areas where gaps in current research exist within the Australian and New Zealand context followed by providing recommendations for future research as follows:

A need for more methodologically strong evaluative research.

Comparisons between Indigenous and non-Indigenous young people.

Qualitative research to compliment research findings and treatment directives.

In this review, we found that comparison groups comprised young people who either dropped out or did not engage in the therapeutic process. There are difficulties in suggesting commonalities between these two offender profiles given the heightened risk of dropouts reoffending. This is primarily due to pre-existing characteristics associated with recidivism and factors influencing the terminating of therapeutic engagement (Hanson et al., Citation2002). Dropouts may also produce an inflationary effect on recidivism rates relative to a sample of untreated young people who would have completed treatment if offered the opportunity (Seager et al., Citation2004). Furthermore, young people who did not engage in treatment were used as a comparison to treatment completers. While this may seem a more adequate comparison group, the motivation for a lack of engagement must come to the forefront. That is, the potential differences between a young person with positive intentions to address the offending behaviour who is placed on a treatment waitlist, compared to another who may agree to treatment to superficially please the authorities but never attend. There are clear challenges researchers face to create an appropriate comparison group.

Second, there is an obvious need for Australian and New Zealand literature to include more information on the post-treatment reoffending of young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and Māori people. Many studies within this review commented on the number of Indigenous young people included in the total sample, but information was limited to just that. Albeit a small sample within this review, it is imperative that future research addresses important information regarding Indigenous young people. This should not be limited to comparisons between the recidivism information of Indigenous young people and non-Indigenous young people. Future research must also address whether treatment programmes address the cultural needs of the cohort to sufficiently change the young person’s trajectory. More precisely, the specific cultural components that are successful in addressing the sexual offending behaviour require identification.

Any absence of cultural consideration in treatment can be a major barrier to the treatment process (Tamatea et al., Citation2011). However, a participant’s engagement with the process can be greatly improved when consideration is given to cultural factors. Grey et al. (Citation2023) recently communicated this, stating treatment for Māori youth with harmful sexual behaviours must be holistic and comprehensive, with an emphasis on family. A body of research recommends that treatment programmes need to be culturally appropriate and informed from the perspective derived from the Māori world and beliefs (Ape-Esera & Lambie, Citation2019; Grey et al., Citation2023; Lim et al., Citation2012; Ministry of Justice, Citation2017). The benefits of culturally relevant programmes include reducing recidivism, retaining participants, increasing positive attitudes and satisfaction associated with treatment, and maintaining Indigenous involvement in therapy after their legal mandate expired (Ellerby & MacPherson, Citation2002; Gutierrez et al., Citation2018; Tamatea et al., Citation2011; Trevethan et al., Citation2004). Considering the disadvantages Indigenous People face regarding over-representation in most aspects of the criminal justice system and the geographical remoteness of their communities in Australia and New Zealand, future research must include the treatment outcomes specific to Indigenous young people who have committed sexual offences. Such research must include consultations with cultural Elders throughout all stages of the research process (from conceptualisation to finished product), and overseen by a cultural advisory group.

Finally, young people who dropped out or did not engage with treatment were more likely to sexually and violently reoffend. These findings are consistent with the wider international literature investigating the post-treatment recidivism rates of people who have committed a sexual offence (Hanson et al., Citation2002; Lösel & Schmucker, Citation2005; Worling & Curwen, Citation2000). Unsuccessful completion of treatment for young people with sexual offences is a significant problem facing treatment providers, accompanied with negative financial and safety implications (Edwards & Beech, Citation2004). However, quantitative causal explanations can only provide so much information and are not enough to identify components and processes that are important to understand the factors that ensure young people are engaged with treatment until successful completion. Rather, more nuanced qualitative research is needed to explore and mitigate the factors preventing young people who have committed a sexual offence from engaging in treatment by adjusting or developing new strategic approaches. This is imperative given the associated negative impact sexual offences have on other young people, the victims, the families involved and the wider community.

An investment in qualitative exploration would involve researchers actively engaging with participants or those who provide treatment to young people. Hearing firsthand about the specific components that were most beneficial could considerably benefit the creation of more effective treatment methods. In addition to this, the experiences of treatment providers regarding unsuccessful completions will certainly benefit knowledge of factors and barriers contributing to a lack of treatment engagement and future directives to engage young people from varying backgrounds. Ensuring young people are given timely and evidence-based opportunities to address their problematic sexual behaviours is paramount, especially given successful treatment completion helps to prevent recidivism. The goal of developing treatment programmes to suit all offenders may be unrealistic. However, there is room to accommodate innovative ideas on assisting young people to address the structural and personal issues implicated in their offending.

Limitations

The findings of the present review should be interpreted with caution due to inconsistent and missing data from available literature in Australia and New Zealand regarding the post-treatment recidivism for young people who have committed a sexual offence. This limited information affected the authors ability to conduct a meta-analysis to evaluate the effectiveness of each treatment programme used in the included studies. Eight studies adhered to the pre-determined inclusion criteria set out at the beginning of this project. However, only four studies included a comparison group limiting the ability to effectively calculate odds ratios with meaningful interpretation. We anticipate that completion of additional studies (treatment evaluations) in the future would allow for a meta-analysis to provide a statistical investigation into the post-treatment recidivism rates of young people who have attended treatment.

Furthermore, it is important to acknowledge the role of various factors impeding the accuracy of official data in recidivism studies. Currents studies rely on police and court official data and the absence of self-reported information has been noted. Official data is limited by factors including the victim’s willingness to report the offence and an adult to act on the victim’s behalf. Also, the child protection agencies or police must investigate the complaint. Police and prosecutors must press charges accurately reflecting the sexual offence and update data on conviction. Further, the use of court convictions relies on charges “not” being dropped or altered to a non-sexual charge through plea bargaining and on the outcome of any adjudication process (Worling & Langstrom, Citation2006). Finally, once accurate data is collected it needs to be made available, when appropriate, to experienced researchers for independent analysis.

Self-reported information offers a unique exploration of reoffending rates by including offending that has not come to the attention of the criminal justice system. This source of information is also a less time-consuming approach to official records (Pham et al., Citation2021). Consequently, based on the present review of official recidivism information, our findings confirm only the minimum number of offences committed by young people post-treatment. However, using both official and self-reported measures would offer complementary ways of measuring recidivism, as each approach provides a unique advantage.

Conclusion

This systematic review provides a critical appraisal and narrative synthesis that also includes a numerical analysis of available evidence in Australia and New Zealand regarding the post-treatment recidivism rates of young people who have committed a sexual offence. In this review, we consolidated the literature suggesting that young people who receive treatment for a sexual offence are less likely to recidivate than those who commence treatment then cease, or for those who fail to engage in the first place. However, this review was limited by inconsistent data collections with different categories and measurements that made comparisons challenging. Our findings also identified three main gaps and provided recommendation for future research directions related to using a scientifically rigorous methodological approach, exploring Indigenous and non-Indigenous young people who offend as two distinct cohorts, and exploring the issue of treatment dropouts and non-engagement with treatment. Overall, this review provides a novel insight into the recidivism outcomes for young people who have committed a sexual offence in Australia and New Zealand.

Supplemental Table

Download MS Word (36.2 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Professor Navjot Bhullar from Psychology at Edith Cowan University for her constructive feedback on the manuscript drafts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Does not equate to the total sample number as Curnow et al. (Citation1998) do not delineate between participants in the treatment and comparison groups.

References

- (* indicates a study included in the present systematic review)

- Adams, D., McKillop, N., Smallbone, S., & McGrath, A. (2020). Developmental and sexual offense onset characteristics of Australian Indigenous and non-Indigenous male youth who sexually offend. Sexual Abuse, 32(8), 958–985. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063219871575

- *Allan, A., Allan, M. M., Marshall, P., & Kraszlan, K. (2003). Recidivism among male juvenile sexual offenders in Western Australia. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 10(2), 359–378. https://doi.org/10.1375/pplt.2003.10.2.359

- *Allard, T., Rayment-McHugh, S., Adams, D., Smallbone, S., & McKillop, N. (2016). Responding to youth sexual offending: A field-based practice model that “closes the gap” on sexual recidivism among Indigenous and non-Indigenous males. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 22(1), 82–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552600.2014.1003107

- Ape-Esera, L., & Lambie, I. (2019). A journey of identity: A rangatahi treatment programme for Māori adolescents who engage in sexually harmful behaviour. New Zealand Journal of Psychology (Online), 48, 41–51.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2022). Recorded crime - offenders. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2020). Contact with the criminal justice system. https://www.indigenoushpf.gov.au/measures.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2021). Youth detention population in Australia 2021. https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/.

- Beck Institute. (2021). Introduction to CBT. https://beckinstitute.org/about/intro-to-cbt/.

- Borduin, C. M., Schaeffer, C. M., & Heiblum, N. (2009). A randomized clinical trial of multisystemic therapy with juvenile sexual offenders: Effects on youth social ecology and criminal activity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(1), 26–37https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013035.

- Caldwell, M. F. (2016). Quantifying the decline in juvenile sexual recidivism rates. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 22(4), 414–426https://doi.org/10.1037/law0000094.

- Cunneen, C. (2014). Colonial processes, Indigenous peoples, and criminal justice systems. In M. Tonry & S. Bucerius (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of ethnicity, crime, and immigration (pp. 386–407). Oxford University Press.

- *Curnow, R., Streker, P., & Williams, E. (1998). Juvenile justice evaluation report: Male adolescent program for positive sexuality. Victorian Government, Department of Human Services.

- Dopp, A. R., Borduin, C. M., & Brown, C. E. (2015). Evidence-based treatments for juvenile sexual offenders: Review and recommendations. Journal of Aggression, Conflict and Peace Research, 7(4), 223–236https://doi.org/10.1108/JACPR-01-2015-0155.

- Edwards, R., & Beech, A. (2004). Treatment programmes for adolescents who commit sexual offences: Dropout and recidivism. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 10(1), 101–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552600410001670946

- Ellerby, L. A., & MacPherson, P. (2002). Exploring the profiles of Aboriginal sexual offenders: Contrasting Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal sexual offenders to determine unique client characteristics and potential implications for sex offender assessment and treatment strategies. Research Branch, Correctional Service Canada. https://www.csc-scc.gc.ca/research/092/r122_e.pdf.

- Fanniff, A. M., & Becker, J. V. (2006). Specialized assessment and treatment of adolescent sex offenders. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 11(3), 265–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2005.08.003

- Farrington, D. P. (2003). Methodological quality standards for evaluation research. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 587(1), 49–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716202250789

- *Fortune, C.-A. G. (2007). Not just ‘old men in raincoats’: Effectiveness of specialised community treatment programmes for sexually abusive children and youth in New Zealand.

- Grey, R., Lambie, I., & Ioane, J. (2023). Aotearoa New Zealand adolescents with harmful sexual behaviours: The importance of a holistic approach when working with Rangatahi Māori. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552600.2023.2165732

- Gutierrez, L., Chadwick, N., & Wanamaker, K. A. (2018). Culturally relevant programming versus the status quo: A meta-analytic review of the effectiveness of treatment of indigenous offenders. Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice, 60(3), 321–353. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjccj.2017-0020.r2

- Hanson, R. K., Gordon, A., Harris, A. J., Marques, J. K., Murphy, W., Quinsey, V. L., & Seto, M. C. (2002). First report of the collaborative outcome data project on the effectiveness of psychological treatment for sex offenders. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 14(2), 169–194. https://doi.org/10.1177/107906320201400207

- Harkins, L., & Beech, A. (2007). Measurement of the effectiveness of sex offender treatment. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 12(1), 36–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2006.03.002

- Harrison, J. L., O’Toole, S. K., Ammen, S., Ahlmeyer, S., Harrell, S. N., & Hernandez, J. L. (2020). Sexual offender treatment effectiveness within cognitive-behavioral programs: A meta-analytic investigation of general, sexual, and violent recidivism. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 27(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2018.1485526

- Henggeler, S. W. (2012). Multisystemic therapy: Clinical foundations and research outcomes. Psychosocial Intervention, 21(2), 181–193. https://doi.org/10.5093/in2012a12

- Henggeler, S. W., Smith, B. H., & Sahloenwald, S. K. (1994). Key theoretical and methodological issues in conducting treatment research in the juvenile justice system. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 23(2), 143–150. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp2302_4

- HueyJrS. J., Henggeler, S. W., Brondino, M. J., & Pickrel, S. G. (2000). Mechanisms of change in multisystemic therapy: Reducing delinquent behavior through therapist adherence and improved family and peer functioning. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(3), 451–467https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.68.3.451.

- Kenny, D. T., & Lennings, C. J. (2007). Cultural group differences in social disadvantage, offence characteristics, and experience of childhood trauma and psychopathology in incarcerated juvenile offenders in NSW, Australia: Implications for service delivery. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 14(2), 294–305. https://doi.org/10.1375/pplt.14.2.294

- Keogh, T. (2012). The internal world of the juvenile sex offende: Through a glass darkly then face to face. Karnac Books. http://site.ebrary.com/id/10521488

- Kettrey, H. H., & Lipsey, M. W. (2018). The effects of specialized treatment on the recidivism of juvenile sex offenders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 14(3), 361–387. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-018-9329-3

- Kim, B., Benekos, P., & Merlo, A. (2016). Sex offender recidivism revisited: Review of recent meta-analyses on the effects of sex offender treatment. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 17(1), 105–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838014566719

- *Kingi, V. M., & Robertson, J. P. (2007). Evaluation of the Te Poutama Ārahi Rangatahi residential treatment programme for adolescent males. Child, Youth and Family Wellington.

- Knopp, F. H. (1985). Recent developments in the treatment of adolescent sex offenders. Adolescent sex Offenders: Issues in Research and Treatment, 1–27.

- *Laing, L., Tolliday, D., Kelk, N., & Law, B. (2014). Recidivism following community based treatment for non-adjudicated young people with sexually abusive behaviors. Sexual Abuse in Australia and New Zealand, 6, 38–47.

- La Macchia, M. (2016). An introduction to over-representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the criminal justice system. https://doi.org/10.4225/50/5804152606bb0

- *Lambie, I., Hickling, L., Seymour, F., Simmonds, L., Robson, M., & Houlahan, C. (2000). Using wilderness therapy in treating adolescent sexual offenders. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 5(2), 99–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552600008413302

- Lambie, I., & Seymour, F. (2006). One size does not fit all: Future directions for the treatment of sexually abusive youth in New Zealand. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 12(2), 175–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552600600823647

- Långström, N., Enebrink, P., Laurén, E.-M., Lindblom, J., Werkö, S., & Hanson, R. K. (2013). Preventing sexual abusers of children from reoffending: Systematic review of medical and psychological interventions. Bmj, 347, 1–11https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f4630.

- Lim, S., Lambie, I., & Cooper, E. (2012). New Zealand youth that sexually offend: Improving outcomes for Māori rangatahi and their whānau. Sexual Abuse, 24(5), 459–478. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063212438923

- Lösel, F., & Schmucker, M. (2005). The effectiveness of treatment for sexual offenders: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 1(1), 117–146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-004-6466-7

- Macgregor, S. (2008). Sex offender treatment programs: Effectiveness of prison and community based programs in Australia and New Zealand. Indigenous Justice Clearinghouse. https://www.childabuseroyalcommission.gov.au/sites/default/files/EXH.015.022.0007.pdf

- Marshall, W. L. (1993). The treatment of sex offenders: What does the outcome data tell us? A reply to Quinsey, Harris, Rice, and Lalumière. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 8(4), 524–530. https://doi.org/10.1177/088626093008004007

- Marshall, W. L., & Marshall, L. E. (2007). The utility of the random controlled trial for evaluating sexual offender treatment: The gold standard or an inappropriate strategy? Sexual Abuse, 19(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/107906320701900207

- Marshall, W. L., & Marshall, L. E. (2008). Good clinical practice and the evaluation of treatment: A response to Seto et al. Sexual Abuse, 20(3), 256–260. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063208323839

- Marshall, W. L., & Marshall, L. E. (2010). Can treatment be effective with sexual offenders or does it do harm? A response to Hanson (2010) and Rice (2010). Sexual Offender Treatment, 5, 1–8. http://www.sexual-offender-treatment.org/index.php?id=87&type=123

- Marshall, W. L., & Pithers, W. D. (1994). A reconsideration of treatment outcome with sex offenders. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 21(1), 10–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854894021001003

- Methley, A. M., Campbell, S., Chew-Graham, C., Mcnally, R., & Cheraghi-Sohi, S. (2014). PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: A comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Services Research, 14(1), 579.

- Ministry of Justice. (2017). Adolescent sex offender treatment: Evidence brief. https://www.justice.govt.nz/assets/Adolescent-Sex-Offender-Treatment.pdf.

- Ministry of Justice. (2020). Youth Justice Indicators Summary Report December 2020. https://www.justice.govt.nz/assets/Documents/Publications/Youth-Justice-Indicators-Summary-Report-December-2020-FINAL.pdf

- Ministry of Justice. (2021). Youth Justice Indicators Summary Report December 2021 https://www.justice.govt.nz/assets

- Ministry of Justice. (2022). Research and data. https://www.justice.govt.nz/justice-sector-policy/research-data/justice-statistics/data-tables/#offence

- *Molnar, T., McKillop, N., Allard, T., Rynne, J., & Adams, D. (2021). Patterns of rearrest for Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander and non-Indigenous youth who have sexually harmed. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 27(2), 167–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552600.2020.1850894

- Oremus, M., Oremus, C., Hall, G. B., McKinnon, M. C., & ECT, & Team, C. S. R. (2012). Inter-rater and test–retest reliability of quality assessments by novice student raters using the Jadad and Newcastle–Ottawa Scales. BMJ Open, 2(4), e001368. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001368

- Oxnam, P., & Vess, J. (2008). A typology of adolescent sexual offenders: Millon adolescent clinical inventory profiles, developmental factors, and offence characteristics. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 19(2), 228–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789940701694452

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., & Brennan, S. E. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. International Journal of Surgery, 88, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijus.2021.105906

- Pham, A. T., Nunes, K. L., Maimone, S., & Hermann, C. A. (2021). How accurately can researchers measure criminal history, sexual deviance, and risk of sexual recidivism from self-report information alone? Journal of Sexual Aggression, 27(1), 106–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552600.2020.1741709

- Popay, J., Roberts, H., Sowden, A., Petticrew, M., Arai, L., Rodgers, M., Britten, N., Roen, K., & Duffy, S. (2006). Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A product from the ESRC methods programme Version, 1(1). https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document

- Quinsey, V. L., Harris, G. T., Rice, M. E., & Lalumière, M. L. (1993). Assessing treatment efficacy in outcome studies of sex offenders. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 8(4), 512–523. https://doi.org/10.1177/088626093008004006

- Reitzel, L. R., & Carbonell, J. L. (2006). The effectiveness of sexual offender treatment for juveniles as measured by recidivism: A meta-analysis. Sexual Abuse, 18(4), 401–421. https://doi.org/10.1177/107906320601800407

- Rice, M. E., & Harris, G. T. (2003). The size and sign of treatment effects in sex offender therapy. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 989(1), 428–440. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07323.x

- Rosenthal, R. (1979). The file drawer problem and tolerance for null results. Psychological Bulletin, 86(3), 638. https://pages.ucsd.edu/~cmckenzie/Rosenthal1979PsychBulletin.pdf

- Schmucker, M., & Lösel, F. (2008). Does sexual offender treatment work? A systematic review of outcome evaluations. Psicothema, 20, 10–19. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/727/72720103.pdf

- Schmucker, M., & Lösel, F. (2015). The effects of sexual offender treatment on recidivism: An international meta-analysis of sound quality evaluations. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 11(4), 597–630. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-015-9241-z

- Seager, J. A., Jellicoe, D., & Dhaliwal, G. K. (2004). Refusers, dropouts, and completers: Measuring Sex offender treatment efficacy [article]. International Journal of Offender Therapy & Comparative Criminology, 48(5), 600–612. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X04263885

- Sherman, L. W., Gottfredson, D. C., MacKenzie, D. L., Eck, J., Reuter, P., & Bushway, S. D. (1998). Preventing crime: What works, what doesn’t, what’s promising.

- Smallbone, S., Crissman, B., & Rayment-McHugh, S. (2009). Improving therapeutic engagement with adolescent sexual offenders. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 27(6), 862–877. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.905

- Smallbone, S., & Rayment-McHugh, S. (2013). Preventing youth sexual violence and abuse: Problems and solutions in the Australian context. Australian Psychologist, 48(1), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-9544.2012.00071.x

- Tamatea, A. J., Webb, M., & Boer, D. P. (2011). The role of culture in sexual offender rehabilitation: A New Zealand perspective. 313–329. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119990420.ch16.

- Trevethan, S. D., Moore, J.-P., & Naqitarvik, L. (2004). The Tupiq program for Inuit sexual offenders: A preliminary investigation. Research Branch.

- Uman, L. S. (2011). Systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 20, 57–59.

- United Nations. (2022). Who are the youth? https://www.un.org/en/global-issues/youth.

- Walker, D. F., McGovern, S. K., Poey, E. L., & Otis, K. E. (2004). Treatment effectiveness for male adolescent sexual offenders: A meta-analysis and review. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 13(3-4), 281–293. https://doi.org/10.1300/J070v13n03_14

- White, R. (2015). Indigenous young people and hyperincarceration in Australia. Youth Justice, 15(3), 256–270. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473225414562293

- Winokur, M., Rozen, D., Batchelder, K., & Valentine, D.. (2006). Juvenile sexual offender treatment: A systematic review of evidence-based research [unpublished report]. Fort Collins, CO: Social Work Research Center, Colorado State University.

- World Health Organization. (2022). Adolescent and young adult health. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescents-health-risks-and-solutions.

- Worling, J. R., & Curwen, T. (2000). Adolescent sexual offender recidivism: Success of specialized treatment and implications for risk prediction. Child Abuse & Neglect, 24(7), 965–982. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(00)00147-2

- Worling, J. R., & Langstrom, N. (2006). Risk of sexual recidivism in adolescents who offend sexually. In H.E. Barbaree & W.L. Marshall (Eds.), The juvenile sex offender (pp. 219–247). The Guildford Press.