?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This research explores the impact of urbanization on familial spatial codes within informal settings and sheds light on their adaptation to contemporary processes. Through comparing residential patterns between traditionally clan-based neighbourhoods alongside urbanized mixed-familial ones in the Palestinian-Israeli town of Sakhnin, the study seeks to scrutinize the socio-economic and political influences on the conduct of traditional code-based systems. Employing GIS analysis, the study examines a two-decade development period of residential patterns in both types of neighbourhoods and uncovers distinct spatial configurations. However, comprehensive interviews with residents reveal that despite urbanization constraints, the familial code continues to guide bottom-up development.

Introduction

Until the middle of the last century, Palestinian towns were developed according to the traditional Islamic planning system, similar to other Middle Eastern Arab countries (Khamaisi Citation1994). However, unlike the urbanization process in Arab countries that is characterized by immigration to central cities, the establishment of the state of Israel disrupted Palestinian urbanization, leading to the destruction of major cities and the imposition of a new Israeli spatial system that restricted immigration from Palestinian towns (Yiftachel Citation1991; Pappe Citation1992; Fallah Citation1989). In addition, the introduction of a new land regime and national planning policies limited the spatial expansion of these towns (Khamaisi Citation2000; Nasser Citation2012). Until the year 2000, Israeli planning institutions disregarded local development within these towns, resulting in informal spaces during their five-decade urban expansion (Khamaisi Citation1994; Yiftachel Citation1999). As a result, the built environment in Palestinian towns in Israel continued to adhere to spatial codes based on self-construction on private lands (Alfasi Citation2014; Khamaisi Citation1999, Citation2003).

Palestinian towns have evolved through self-construction on familial inherited lands, adhering to spatial and cultural codes such as respecting the hierarchy of shared and public spaces, communal management of public resources, visual privacy of private spaces, and obtaining neighbours’ consent for additional construction (Akbar Citation1988; Ben Hamouche Citation2009; Hakim Citation2008, Citation2014, Citation2019; Khamaisi Citation1999). Despite rapid population growth, clans (hamula, in Arabic) have preserved multi-generational traditional construction methods, maintaining controlled semi-public spaces and close proximity between family residences, which are characteristic of residential areas across the Middle East (Abu-Lughod Citation1971; Ben Hamouche Citation2004; Elsheshtawi Citation2004). However, socio-economic and political changes in Israel have significantly influenced the adaptation of these codes and the spatial organization of Palestinian towns (Khamaisi Citation2005; Totry Fakhoury & Alfasi Citation2017). The intriguing aspect is that these changes occurred without a guiding hand, making their case particularly interesting for investigation.

Families without inherited land purchased agricultural plots from larger clans on vacant lands at the outskirts of clan neighbourhoods. These smaller families constructed familial complexes adjacent to each other, thereby creating new neighbourhoods generated by socio-spatial dynamics that were different from those of traditional clan neighbourhoods. There was a general expectation that these mixed neighbourhoods would exhibit a different spatial order from that governed by traditional clan control, reflecting a willingness to reside alongside neighbours from other families. This study employed GIS analysis and comprehensive interviews with residents to examine the dynamics of residential construction over a two-decade period in both clan and mixed neighbourhoods. This study investigated the adaptation of traditional construction codes in response to emerging economic and social dynamics in these neighbourhoods.

Through documenting and analysing the evolution of residential patterns in the town of Sakhnin, this study provides a deeper understanding of the evolution of the spatial pattern in informal urban spaces. It investigates how Middle Eastern traditional spatial codes respond to urbanization processes in informal conditions. Documenting these codes is crucial as modern plans pose threats of extension and replacement in these towns. Moreover, the adaptable and flexible norms of these traditional code-based principles offer valuable perspectives for addressing the shortcomings and challenges of both modern planning and code-based systems.

To delve into this spatial dynamic, the theoretical background will describe the evolution of urban code theories alongside the emergence of informal practices within modern planning theories. It aims to pinpoint a theoretical gap and outline the research approach of the current study, which endeavours to bridge these two theories. Following this, the historical overview of spatial development in Palestinian towns in Israel will elucidate the role of spatial codes in guiding self-construction practices in the absence of formal planning. The methodological section will offer an overview of the research case, focusing on Sakhnin, and detail the data employed in the study, including GIS mapping, analysis, and interviews conducted with residents. Subsequently, the findings will illustrate the evolution of traditional familial codes and their manifestation through spatial patterns in both types of neighbourhoods. Finally, the conclusion will summarize the findings and offer a comprehensive analysis of how these insights prompt inquiries into nuanced planning approaches that navigate the interplay between contemporary planning principles and coding methods within the context of informal urban dynamics.

Theoretical background

Informal code-based urbanism

Until the middle of the last century, cities around the world followed spatial codes that defined the relations between individuals and between individuals and the community. Each subsequent construction was governed by these building norms and principles, with consideration for its relationship with the existing built environment, the public realm, and conditions of use (Batty and Marshall Citation2012; Hakim Citation2001; Talen Citation2009). The bottom-up code-based traditional approach relied on a continuous exchange of information and a multi-layered decision-making process among the tenants. These codes were subjected to ongoing interpretation by various stakeholders, enabling spatial adaptation to social changes over time (Akbar Citation1988; Cozzolino Citation2020; Hakim Citation2019). Research indicates that despite the absence of top-down guidance, the piecemeal construction of these ancient built environments allowed the emergence of ordered spatial patterns (Batty Citation2005; Batty and Marshall Citation2012; Moroni Citation2010, Citation2015; Portugali Citation1999; Rauws Citation2015; De Roo, Hillier, and Van Wezemael Citation2012; Salingaros Citation2000).

However, the transition to modern planning replaced the bottom-up dynamics with a system requiring the acquisition of building permits from a centralized authority based on long-term zoning plans. These plans aimed to generate specific outcomes embodying a pre-defined socio-spatial order (Moroni Citation2015; Yiftachel Citation2009). Critical approaches that view the complexity of urban dynamics claim that comprehensive long-term planning, which aspires to control future configurations, fails to adjust to ongoing social, political, economic, and climate transformations. This highlights the fundamental inherent drawback of modern planning tools that rely on gathering scientific information from multiple sources to generate a highly detailed comprehensive plan (Cozzolino Citation2020; Moroni Citation2015; Roo, Gert, and Van Wezwmeal Citation2012). Others argue that this new social ordering of modern planning uses planning as a tool to control and manage urban communities. Within the plan, planning laws define what is legal for specific groups and ideas, thus categorizing other actors and activities either as ‘informal’ or ‘illegal’ (Assche, Kristof, and Duineveld Citation2014; Chiodelli and Moroni Citation2014; Roy Citation2011; Yiftachel Citation2009). Consequently, informal spaces are an inherent by-product of formal modern planning.

Informal spaces typically emerge within marginalized communities and vulnerable social groups that do not conform to the formal social ordering imposed by the state. These places are often deprived of planning and spatial rights, thereby denying their legitimacy within the formal sphere (Chiodelli and Zfadia Citation2016; Roy Citation2005). Since informal spaces violate established legal plans, formal institutions perceive them as chaotic and subject them to ongoing demolition threats (Eizenberg Citation2019; Van Assche et al. Citation2014; Yiftachel Citation2009). The formal planning institutions disregard the development of these spaces and primarily focus on constraining their expansion (Roy Citation2011; Silva and Farrall Citation2016; Yiftachel Citation2009). As a result of the lack of public investments and the absence of adequate infrastructure and public amenities in these spaces, residents are forced to take on the responsibility of spatial development themselves in order to meet their fundamental needs. The absence of formal institutional management of the informal spaces strengthens bottom-up social ordering principles and spatial urban codes (Hakim Citation2014).

Ancient code-based traditional spatial systems have been documented in various regions worldwide (Hakim Citation2001; Talen Citation2009). However, there has been limited research on how these spaces adapt to contemporary urbanization processes. Typically, code-based systems experiencing uncontrolled urbanization dynamics today are considered informal. Studies examining informal spaces from a power structure analysis perspective often perceive them as impoverished spaces of necessity, overlooking the ordered spatial configurations resulting from such uncontrollable dynamics (Hakim Citation2019; Portugali Citation1999; Suhartini and Jones Citation2020). Conversely, studies investigating code-based bottom-up dynamics in contemporary conditions often neglect to examine the power dynamics, resulting in an idealized perception of these informal spaces (Eizenberg Citation2019; Roy Citation2011; Totry Citation2023). This research bridges this theoretical gap by aiming to shed more light on this type of spatial dynamics.

Historical context

Socio-spatial development of Palestinian towns in Israel

At the beginning of the last century under the British Mandate, the Palestinian society went through an exhilarated urbanization process shifting from a 70% rural agricultural society in the 1920s to almost half of the people living in central cities such as Akko, Haifa, and Jaffa (Schnell and Fares Citation1996; Yazbak Citation2004; Khmaisi Citation2005). However, the 1948 ‘Nakba’ (meaning ‘catastrophe’ in Arabic, and this term is used by the Palestinians to describe the war leading to the establishment of the state of Israel) destroyed main cities and dozens of villages, leading to the evacuation of most of their inhabitants to outside the newly established Israeli borders. This event turned the remaining Palestinians in Israel into a defeated ethnic minority in a Westernized Jewish nation-state (Falah Citation2003; Khamaisi Citation2003; Luz Citation2007; Pappe Citation1992). The remaining 156,000 Palestinians stayed in their original villages or found shelter in hosting ones (Yazbak Citation2004). During the first two decades of the state, until 1966, the military regime banned Palestinians from migrating to other localities (Bäuml Citation2007).

Since the establishment of the state, national planning policy has aimed towards building a new national sphere for the Jewish majority, thus restricting the spatial expansion of Palestinian towns in Israel. Under the Israeli land regime, most of the Palestinian land rights were not recognized.Footnote1 In addition, national infrastructures such as parks, highways, and stone quarries, and Jewish localities were often allocated near Palestinian villages limiting their natural expansion (Bäuml Citation2007; Falah Citation1989; Khamaisi Citation2004; Nasser Citation2012; Yiftachel Citation1999). Since 93% of the lands in Israel are state-owned, the prospects of allocating land for new non-Jewish settlements are extremely limited (Khamaisi Citation1999; Lewin-Epstein, Al-Haj, and Semyonov Citation1994; Yashiv and Kaisar Citation2013). As a result, about 90% of Palestinians in Israel today still live in their original towns (ICBS Citation2024).

The familial spatial code of the Middle Eastern Muslim built environment has continued to guide the development of Palestinian towns and villages. This code guides the bottom-up spatial development based on the prevailing familial land inheritance, self-construction for future generations, construction subject to the consent of neighbours, gender spatial segregation, communal control of the public sphere, and hierarchal transition between public and private spaces (Akbar Citation1988; Ben Hamouche Citation2004, Citation2009; Hakim Citation2010, Citation2014, Citation2019). The Israeli planning institutions disregarded local planning in these towns, which meant that almost all construction was considered informal. The state’s neglect towards investing and developing necessary public resources strengthened the reliance on local capital reflected through the preservation of private land ownership and maintaining the familial rule of residential dynamics (Al-Haj Citation1995; Khamaisi Citation2002; Yiftachel Citation1991, Citation2000). The lack of proper public investment accompanying the modernization and urbanization process in these towns and the preservation of traditional cultural and social norms has resulted in ‘besieged urbanisation’ (Meir-Brodnitz Citation1986) or ‘selectively disturbed urbanism’ (Khamaisi Citation2005), indicating that growth and expansion as per traditional structure and principles does not lead to adequate urbanization.

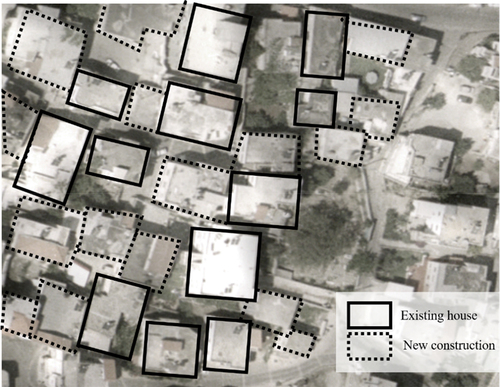

After the establishment of the state, the expansion of these towns took place on inherited private agricultural lands around the original village core (). These areas were divided into segments among Hamulahs’ (clans’) control over the land creating different neighbourhoods. The neighbourhoods were divided by main streets from the centre outwards to the agricultural lands. In each neighbourhood, extended families built house complexes on their privately owned land around a shared yard (Arraf Citation1985). These neighbourhoods consisted of two types of residential patterns: clan neighbourhoods developed on inherited agricultural lands of the larger clans and mixed-familial neighbourhoods consisting of smaller different families who exchanged and bought lands in the farther areas around clan lands and neighbourhoods.

Despite the changes in the employment of the Israeli – Palestinian population base from agriculture to industry and services, the importance of private land ownership in their towns was preserved. Private land was considered a social asset as it was the central means for the family to preserve resources for housing their future generations. Therefore, most of the lands in Palestinian towns in Israel today are privately owned by residents (Yiftachel Citation2000). These socio-economic changes and the rapid growth of the Palestinian population, which has increased by sixteen times since 1948 (ICBS Citation2024), reshaped the roles and performance of the clan. Despite the weakening of the clan’s involvement in people’s daily lives, their role in the political local authority remains preserved. Research shows that Palestinians in Israel still base their voting decisions on familial background. This means that despite the democratic elections, the mayors usually present larger clans. The mayors’ commitment to their clan and their inability to tackle other clans’ internal affairs meant that only one clan would control the municipal resources, creating an inherent conflict of interest among residents of the town (Al-Haj Citation1995; Falah Citation1989; El-Taji Citation2008; ICBS Citation2024).

Since the year 2000, the Israeli planning institutions began preparing local plans in Palestinian towns to bring order to what was seen as ‘spatial chaos’ created over the previous five decades (Bana and Swede Citation2012; Khamaisi Citation2002, Citation2004). The new neighbourhoods developed, according to these plans, on public lands on the outskirts of towns comprise either single-house units or multi-storey residential buildings. The plans for these neighbourhoods reflect Western-oriented norms of individuality and the importance of the nuclear family, unlike the familial complexes in the traditionally built environment (Khamaisi Citation2000, Citation2005; Nasser Citation2012). Despite the new Western urban fabric, residents still maintain spatial norms such as safeguarding the privacy of their homes (Bawardi Citation2021; Tory Fakhoury & Alfasi Citation2018). The planning of modern neighbourhoods created environments that ignore the traditional planning-without-a-plan qualities and embedded social norms, sometimes resulting in an inability to market these residential projects (Bana and Swede Citation2012).

This research focuses on clan-based and mixed families-based neighbourhoods that have emerged around the core in the city of Sakhnin. The study examines the informal and spontaneous adaptation of the familial spatial code in these neighbourhoods. The influence of this traditional code, which fits clan neighbourhoods, is anticipated to be weaker in mixed neighbourhoods that are ruled by the newly emerging code of ‘living among strangers’.

Methodology

This research aimed to analyse the adaptation of traditional familial codes based on self-construction to the urbanization process. To achieve this, the study focused on the built environment created during the two decades of urbanization between 1988 and 2009 in Palestinian towns before the intervention of top-down formal planning. It investigated the built fabric surrounding the core developed on agricultural lands, following a code-based planning system. The study compared the dynamics of residential construction and the emerging spatial patterns of old traditional clan-based neighbourhoods on inherited lands with the dynamics of new mixed-familial neighbourhoods constructed on lands without any pre-existing familial ownership.

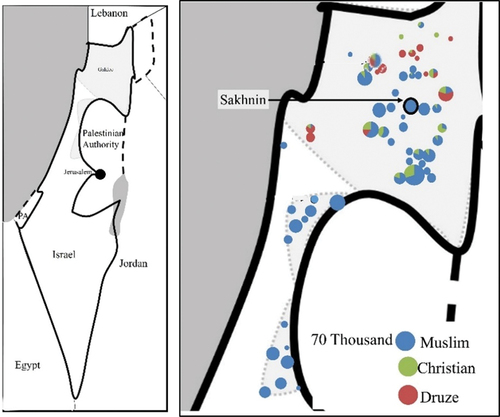

The study employed GIS mapping and analysis to examine the dynamics of residential constructions in both types of neighbourhoods, where construction was initiated by residents without top-down guiding laws. Additionally, interviews with residents were conducted to gain insight into the socio-economic factors influencing residents’ decision-making processes. The research was conducted in the town of Sakhnin, a Muslim town (including a 5% Christian minority) with 33,736 residents (in 2024) located in the centre of Northern Israel (see ), reflecting the typical spatial development of Palestinian towns in Israel.

Figure 2. Left- regional map of Israel. Right- distribution of Palestinian towns in northern and Central Israel (agricultural towns, excluding Bedouin towns which have different spatial aspects).

Case study

Like other Palestinian towns in Israel, Sakhnin was a small agricultural village before 1948 and expanded to a mid-sized town due to population growth (ICBS Citation2024). During the research period, it expanded substantially, growing from 16,000 residents in 1988 to 25,000 in 2009 (ICBS). During the establishment of the state in 1948, Sakhnin lost about 90% of its communal shared lands. Since then, Jewish settlements Esh’har, Yuvalim, Ya’ad, Atsmon-Segev, Misgav, and Rakefet were established to the north and west of Sakhnin at a distance of 2 km, and the national park Tel Yodfat was established to the south. These factors have limited the spatial expansion of the town increasing the demand for housing on privately owned lands within the town (see ).

The study compared ten clan neighbourhoods with six mixed neighbourhoods (see ). It excluded other neighbourhoods in Sakhnin, such as the core neighbourhood (the original village constructed before 1948), the industrial zone, and the Al-Yasmin neighbourhood, which were planned and constructed by the state. These neighbourhoods were excluded from the research due to their different spatial configurations.

The residential pattern in Palestinian towns in Israel is typified by familial complexes of several housing units of extended families surrounding a shared yard on each familial plot. These complexes are planned and constructed by the eldest male in the family. Therefore, the researchers conducted fifteen in-depth hour-long interviews in Arabic with the oldest male of each family in 2018. Each interviewee represented a housing complex consisting of 3–12 units, resulting in the overall construction of over 100 housing units. The residents provided a comprehensive explanation regarding their decision-making process for the location of each building on the plot. This included considerations such as the proximity to neighbouring houses, the preservation of open spaces within the plot, the location of the entrance, land rights exchanges, and informal agreements among the tenants regarding property borders. Additionally, they discussed obtaining blueprint approval for the building and the various economic and social considerations affecting the construction process.

The GIS analysis examined additional construction in seven time periods using aerial photographs from the governmental GIS archive, ‘Survey of Israel’. The time periods were: T0–1988; T1–1992; T2–1995; T3–1999; T4–2003; T5–2006; and T6–2009. During each period, additional buildings were identified and marked, establishing the foundation for measuring the total built-up area in both neighbourhood types. The numeric analysis employed two indices: the Nearest Neighbour Index and the New-Old Index.

The Nearest Neighbour Index (Boots and Getis Citation1988) was employed to analyse the spatial distribution of buildings and determine whether the residential arrangement follows a clustered or dispersed pattern. It divided the average distances between buildings in each neighbourhood during each period by the ‘expected value’, which is the division of the average distance between buildings calculated based on the number of buildings in the neighbourhood by the area. The following index: , where

is the average (the distances between the centroid of the building and the closest building in metres),

is the neighbourhood area, and

is the number of buildings there, was calculated with the spatial analysis extension of ArcGIS 10.1. When the ‘observed value’ is similar to the ‘expected value’, their division will approach 1, indicating a random spatial distribution pattern (random when

). However, when the buildings are closer to each other than the expected average distances, the division between them will be smaller than 1, indicating a clustered spatial distribution (clustered when

). Consequently, when the buildings are further from one another than the expected average distances, the division between them will be greater than 1, indicating a dispersed spatial distribution (dispersed when

) ().

Figure 5. Scheme of types of buildings’ spatial distribution (observed value/expected value) (a) clustered, patterns, (b) random,

, (c) dispersed,

.

The second indicator, the New-Old Index (NOI), examines how compact the new construction is in each neighbourhood in every period. , calculates the division between the distance between new buildings and the nearest existing building in each neighbourhood by the average distance between buildings in the town.

represents the average of new construction to nearest buildings, and

represents the average between buildings in the town. When a new construction in a neighbourhood is closer than the average distance between buildings in the town (the index will be smaller than 1), it indicates a more compact pattern of construction. In contrast, when new construction in a neighbourhood is farther than the town average (with an index larger than 1), it indicates a more dispersed pattern of construction.

Findings

To understand how the traditional familial code has adapted to the informal urbanization process, the findings will initially describe the dynamics of the code in Palestinian towns in Israel. Subsequently, the distinct spatial properties of both clan and mixed neighbourhoods will be presented. Later, the analysis will demonstrate the evolution of the code through the different spatial patterns in both types of neighbourhoods. The impact of the socio-economic factors on the construction process in both types of neighbourhoods will then be explained.

The traditional familial code

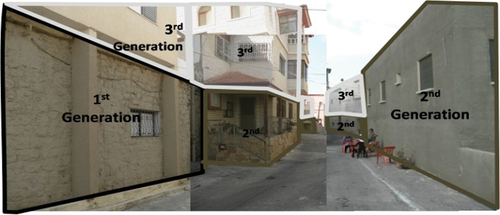

Interviews with residents from the older generation and patterns shown in areal maps exhibited the traditional familial code of the family’s responsibility of ensuring housing for their sons on familial private lands following agreements among the tenants in Palestinian towns. Spatial patterns in the original village in the core existed before the establishment of the state consisting of several house units in familial complexes built back-to-back surrounding a shared yard (Khamaisi Citation1994). These complexes hosted first, second, and third generations (see ). This type of spatial arrangement reflected the village’s communal structure during the Ottoman Empire and the British Mandate; it was also helpful for protection needs (Arraf Citation1985). The socio-spatial distribution of neighbourhoods in the original village followed the territorial division between clans. Analysing the landownership map of the built-up area in the core of Sakhnin revealed that it includes the clans’ privately owned plots. The interviews revealed that large clans in Sakhnin hosted smaller families in their neighbourhoods and offered them protection. Residents also clarified that they constructed their own houses after receiving their neighbours’ consent and ensuring that the additional construction would not block the sun and the view of existing buildings, such that it would not allow visual accessibility to private spaces nor hinder any future construction on their lands. Interviewees noted that unresolved conflicts among clan members were brought to the Mukhtar, the eldest member of each clan (the position of the town’s Mukhtar would rotate among the major clans).

The massive land confiscation during the establishment of the state reinforced preservation of private lands as family members needed to ensure preservation of resources for future generations (Khamaisi Citation1994, Citation2000). The GIS pattern analysis showed that the traditional socio-spatial norms that existed in the original village continue to affect spatial development in Sakhnin until today. However, in an interview, the municipal planner raised challenges subject to the familial code in recent years. He explained that the Ministry of Housing began planning new residential projects in Sakhnin to match population growth and the continued shortage of private land ownership. These projects will be constructed on state lands and adhere to Israeli planning laws. The new urban project allows the residents to purchase a housing unit in a multi-storey residential building, unlike the traditional pattern of familial complexes with shared yards. Reflecting on the residents’ hesitation to participate in such projects and their resistance to living among unfamiliar strangers, the municipal planner stated the following:

We face a great housing distress in Sakhnin, especially for about 40% of the residents who do not own any vacant land and cannot ensure housing for their sons. Nevertheless, almost none of the town’s residents registered for this new project. They are afraid to invest and buy a house in such a project, as it is very different from the traditional way of living in the town.

Socio-spatial aspects of the clan and mixed neighbourhoods

The largest clans in Sakhnin owned the agricultural plots around the original village. Consequently, the residential areas that emerged beyond the core after the establishment of the state were clan neighbourhoods. Residents explained that they had constructed their homes adjacent to the existing built environment as they had to rely on its infrastructure when developing the new areas. The first generation that constructed houses in these clan neighbourhoods allocated the remaining space on the plot as yards, ensuring its preservation for future generations. The yard served both communal gatherings and agricultural purposes, featuring various cultivated trees and plants, including pomegranates, lemons, figs, mint, and others intended for the residents’ consumption. Subsequently, the second generation would construct several additional buildings corresponding to the number of sons around a shared yard. Owing to technological advancements enabling vertical construction, sons of the third generation would add floors on top of each of the second generation’s houses according to the number of new families (). This familial complex maintained the hierarchal transition from the familial yards to the shared road used by other families in the clan and onwards, to the main street used by the town’s residents. During this period, the decision-making process remained adaptable, with the extended family members exchanging plots among themselves to allow the construction of roads or shared infrastructure.

The residents explained that the improved economic situation in Israel during the 1980s, reflected in the early period of the GIS analysis, enabled smaller families, who had previously resided in the core, to purchase agricultural land plots from larger clans located at the outskirts of clan neighbourhoods. This facilitated the construction of their houses, thereby establishing the mixed neighbourhoods. shows that mixed neighbourhoods started to emerge almost one generation after the creation of clan neighbourhoods. The data indicate that at the start of the study in 1988, clan neighbourhoods comprised 1,562 buildings, five times more buildings than the number in mixed neighbourhoods, which totalled only 300. Moreover, the research highlights that over the course of two decades, by the end of the study period in 2009, there was a 70% increase in the number of buildings in clan neighbourhoods compared to a 360% increase in mixed neighbourhoods. In other words, clan neighbourhoods were denser than mixed neighbourhoods at the beginning of the study. With 0.12 of the area covered with buildings in clan neighbourhoods, they were four times denser than mixed neighbourhoods with a 0.03 density. However, this trend shifted at the end of the study, with 0.2 density in clan neighbourhoods compared to a 0.11 density in mixed neighbourhoods. This means that by the end of the study, density in mixed neighbourhoods was double that of clan neighbourhoods.

Table 1. Construction coverage in both types of neighbourhoods at the beginning and end of the study period.

While plot sizes were similar in both types of neighbourhoods, mixed neighbourhoods consisted of unrelated families. Consequently, the residents in mixed neighbourhoods needed to collaborate to include essential infrastructure elements such as roads and electric poles. The interviews suggested that, unlike the lands inherited from the family’s estate in clan neighbourhoods, each land exchange in the mixed neighbourhoods involved an economic cost. Despite the familial diversity and different dynamics of conduct in mixed neighbourhoods, research showed that the familial code remained the guiding factor for creating spatial residential patterns, as detailed in the following section.

Spatial patterns in both neighbourhoods

The findings demonstrated that the bottom-up informal self-construction in both neighbourhoods resulted in distinct spatial patterns. Generally, the index in demonstrates a gradual reduction over the years, confirming that both types of neighbourhoods are becoming denser as expected due to population growth.

Table 2. The average distance between buildings in each neighbourhood in Sakhnin, delineating the observed average distance, the expected average distance (considering random dispersal), and the actual pattern, based on the NNI (calculated as per the observed divided by the expected value).

Clan neighbourhoods exhibited a dispersed type of development (with values greater than 1), whereas mixed neighbourhoods display a clustered pattern (with

values less than 1). The

value in clan neighbourhoods increased throughout the study, rising from 1.12 at the start of the study period to 1.45 at the end. This does not imply that buildings are being constructed at a greater distance from existing buildings, as the observed distance changed slightly from 20.65 metres in 1988 to 18.49 metres in 2009 (). However, this indicates that the massive growth in the number of buildings overall in the town was expected to affect clan neighbourhoods more than what actually occurred in reality. As is displayed in the expected value decreased from 18.4 metres in 1988 to 12.74 in 2009.

Unlike clan neighbourhoods, the NNI value in mixed neighbourhoods increased from 0.78 in 1988, indicating a definite clustering pattern, to 0.99 in 2009, suggesting an almost random distribution. This can be attributed to the rising population density and the construction of the entire neighbourhood, which blurs the impact of the familial clusters within the mixed neighbourhood (see ). The filling up of the neighbourhood was also reflected in the interviews:

In the past, this neighbourhood was relatively spacious. Families built their homes on their plots far from buildings in neighbouring plots, for privacy considerations. With time, we were forced to construct closer to each other because there were no empty areas for construction left in our plot. However, we constructed the houses facing the inner yard within the plot with almost no windows facing the neighbours.

Open spaces and economic gaps

The numerical analysis indicates that new construction in clan neighbourhoods gradually became closer to neighbouring buildings over time, whereas in mixed neighbourhoods, new construction remained at almost the same distance throughout the research period. In clan neighbourhoods, the index decreased from 1.48 in 1988 to 1.16 in 2009. While in mixed neighbourhoods, the value remained almost stable, varying from 0.94 to 0.97, manifesting the same development pattern throughout the entire study period (). The change in distances between buildings in clan neighbourhoods is attributed to the reduction of available land over time. A second-generation interviewee from a clan neighbourhood explained how landownership and familial relations had influenced the residential construction choices made by his family:

Before the first house was built in this plot, this area was empty, and some of it was cultivated as agricultural areas. Initially, my father built his house close to the road for easier access, but far from the built area around the core for privacy. Later, my four brothers and I built our houses near our father’s.

The interviewee recalled the spacious area between his father’s and uncle’s houses: ‘There were not even borders between the houses, only trees marking more or less where our uncle’s plot would start and ours would end.’ However, as the younger generation grew up and sought to establish their own families, the land was once again divided: ‘When I built these houses for my sons, I couldn’t position them any farther because the plot got smaller. We preferred to leave a larger space in the family yard for our family gatherings.’

In mixed neighbourhoods, the entire estate is initially divided into familial plots. Each family deals with its limited space, and any additional constructions are equidistant from existing buildings. An interviewee with a second generation from a mixed neighbourhood explained the construction considerations during earlier stages of this spatial development: ‘I come from a small family. I grew up in our house in the core, located in the clan’s area’ (his family did not belong to the larger clan but lived in the area of the clan’s territory). He then moved to a house his father had bought for him in the mixed neighbourhood. ‘Back then, it was agricultural land. the original clan had a substantial amount of land, so they didn’t need it. My father acquired this plot in exchange for two cows’. The interviewee and his two younger brothers constructed their houses in the outer corners of the plot, leaving a large yard between them dedicated to constructing homes for future generations (see ).

Concluding discussion

The analysis of the spontaneous adaptation of residential patterns in clan and mixed neighbourhoods in Sakhnin revealed that the local spatial code remains the guiding principle of self-construction practices, owing to the absence of formal planning. Furthermore, it highlights the influence of socio-economic and political factors on the evolution of the code in both types of neighbourhoods. Additionally, it exemplifies the implementation of code-based traditional planning in informal urbanism and offers insightful observations on the engagement of the Israeli planning system in the traditional built environment.

The findings of the study demonstrate that urbanization processes, accompanied by population growth and economic changes, prompt modifications to the spatial code. In an informal urban setting where official authorities fail to provide adequate housing opportunities to meet population demands, there is an increased reliance on private land ownership as a means for families to construct their own homes. However, contrary to previous years when land ownership held social and cultural significance, passed down to male offspring to maintain family assets, the study reveals how economic pressures have produced a new urban dynamic within the land market. This dynamic has influenced spatial arrangements among families. The purchase of private lands by small families from large clans challenged the socio-spatial hierarchy of clan territorial dominance for the first time. Consequently, it has led to the emergence of mixed neighbourhoods comprising diverse families with distinct spatial dynamics, contrasting with the formerly prevalent clan-based spatial division.

Despite the impact of economic pressure on the land market, the study findings indicate the resilience of the cultural familial code of self-construction. This resilience is evident in the preservation of privacy within familial spaces, the respect accorded to existing buildings and their future building rights, and the ongoing negotiations among tenants. These factors reinforce the prevailing phenomenon of ‘besieged’ and ‘disturbed’ urbanism of Palestinian towns in Israel, as defined by scholars (Khamaisi Citation2005; Meir-Brodnitz Citation1986). The research provides an example of this distinctive form of urbanization, wherein the anticipated decline in the influence of family relations corresponds with reality. Despite expectations that urbanization would compel the Palestinian society to adopt a new, Western lifestyle characterized by urban anonymity and individualism, the construction of houses in these towns continues to be governed by family land resources and family size. This ultimately demonstrates the enduring power of cultural spatial codes even amidst urbanized pressures.

The analysis revealed the different roles of familial organization in each case. Clan neighbourhoods that are populated by a single clan exhibit a significant allocation of land, where buildings are initially dispersed with wider open spaces between them on inherited lands. The decrease in the distance between new constructions in these neighbourhoods throughout the second and third generations can be ascribed to the rise in population demand. Simultaneously, mixed neighbourhoods tend to self-organize in compact familial clusters within their small plot of land. The familial order is thus exposed: residents tend to establish dispersed spatial arrangements when living among close relatives (first and second-degree cousins). Conversely, when living among strangers, they tend to cluster together and build familial complexes facing the inner yard. Analysis of this pattern revealed that both types of neighbourhoods develop according to the same spatial rule: residential proximity and familial relations. This rule dictates that on the plot scale, houses are built in close proximity to each other, but on the neighbourhood scale, families are expected to keep a safe distance from one another.

The study demonstrated the impact of economic and cultural factors on the spatial code, through the different residential patterns in both types of neighbourhoods. The urbanization process has a mutual effect on both types of neighbourhoods displayed through the gradual reduction in the distance between buildings over time. Nevertheless, the different socio-economic properties of these two types of neighbourhoods are reflected in contrasting spatial patterns as clan neighbourhoods spread out while mixed family neighbourhoods cluster together. Consequently, distances between neighbours and open spaces shrink with time. However, the limited residential spaces in mixed neighbourhoods as opposed to the more flexible construction dynamics in clan neighbourhoods sharpen the socio-economic gaps in Palestinian towns between large clans and smaller families.

The study showed that informal settings force residents to construct their own residential needs and infrastructure. However, these spaces tend to cater more to necessity rather than providing acceptable conditions that are larger than the individuals’ capabilities. In addition, the self-organizing mechanism exacerbates economic disparities in these towns, creating a division between large families who possess lands and others who lack such resources, leaving them unable to address their residential needs. This emphasizes the necessity for implementing top-down equitable intervention in this traditional planning system to create a comprehensive vital living environment. Moreover, the traditional code-based construction manner in these towns displays the adaptive and flexible nature of such a dynamic planning system. The ability of residents to construct their homes based on their own needs and resources allows the gradual adaptation of the built environment to economic and cultural changes over time. In contrast, the top-down planning system in Israel, which aimed to provide a fit-for-all end product for newly planned neighbourhoods that disregarded the local cultural spatial norms, resulted in a lack of cooperation from the residents. Therefore, this suggests a need for merging the bottom-up flexible dynamics among residents with the need for a top-down public investment to create an open-ended adaptable urban system customized for preserving the local spatial knowledge passed on through generations while offering equitable opportunities for groups with limited resources.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. Public lands under the British Mandate were transferred to the National Israeli Land Council. In addition, the Israeli land regime did not recognize traditional ownership, which was not officially registered during the Ottoman Empire, resulting in confiscation of about 60% of the traditionally owned private Arab lands in Israel. Moreover, according to the Absentee Property law in 1950, the Waqf, the social institution holding public assets was considered absent. As a result, public Arab lands used for religious institutions were also confiscated.

References

- Abu-Lughod, J. 1971. “North African Cities Blend the Past to Face the Future.” African Reports 16 (6): 12–15.

- Akbar, J. 1988. Crisis in the Built Environment: The Case of the Muslim City. Leiden: Brill.

- Alfasi, N. 2014. “Doomed to Informality: Familial versus Modern Planning in Arab Towns in Israel.” Planning Theory & Practice 15 (2): 170–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2014.903291.

- Al-Haj, M. 1995. “Kinship and Modernization in Developing Societies: The Emergence of Instrumentalized Kinship.” Journal of Comparative Family Studies 25:311–328. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/kinship-modernization-developing-societies/docview/232574359/se-2

- Arraf, S. 1985. The Arab Palestinian Village. Jerussalem: Institute for Palestine studies. in Arabic.

- Assche, V., R. B. Kristof, and M. Duineveld. 2014. “Formal/Informal Dialectics and the Self-Transformation of Spatial Planning Systems: An Exploration.” Administration & Society 46 (6): 654–683. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399712469194.

- Bana, E., and H. Swede. 2012. Outline Planning for Arab Localities in Israel, Part A. Jerusalem: Bimkom and ACAP. http://eng.bimkom.org/_Uploads/31outlineplan.pdf.

- Batty, M. 2005. Cities and Complexity: Understanding Cities with Cellular Automata, Agent Based Models, and Fractals. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Batty, M., and S. Marshall. 2012. “The Origins of Complexity Theory in Cities and Planning.” In Complexity Theories of Cities Have Come of Age: An Overview with Implications to Urban Planning and Design, edited by J. Portugali, H. Meyer, E. Stolk, and E. Tan, 21–55. Heidelberg & Berlin: Springer.

- Bäuml, Y. 2007. A Blue and White Shadow. The Israeli Establishment’s Policy and Actions Among Its Arab Citizens: The Formative Years. in Hebrew. Haifa: Pardes 1958–1968

- Bawardi, H. “Housing and Location Choice Among Young Palestinians in Israel: Preferences of Residency.” MA diss. The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. 2021.

- Ben Hamouche, M. 2004. “The Changing Morphology of the Gulf Cities in the Age of Globalisation: The Case of Bahrain.” Habitat International 28 (4): 521–540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2003.10.006.

- Ben Hamouche, M. 2009. “Can Chaos Theory Explain Complexity in Urban Fabric? Applications in Traditional Muslim Settlements.” Nexus Network Journal 11 (2): 217–242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00004-008-0088-8.

- Boots, B., and A. Getis. 1988. Point Pattern Analysis. California: SAGE.

- Chiodelli, F., and S. Moroni. 2014. “The Complex Nexus Between Informality and the Law: Reconsidering Unauthorised Settlements in Light of the Concept of Nomotropism.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 51:161–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.11.004.

- Chiodelli, F., and E. Tzfadia. 2016. “The Multi Faceted Relation Between Formal Institutions and the Production of Informal Urban Spaces: An Editorial Introduction.” Geography Research Forum 36:1–14. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/The-Multifaceted-Relation-between-Formal-and-the-of-Chiodelli-Tzfadia/0564c093f1f3ebae7f1ffa9f50089a1856c4c53a?utm_source=direct_link

- Cozzolino, S. 2020. “The (Anti) Adaptive Neighbourhoods. Embracing Complexity and Distribution of Design Control in the Ordinary Built Environment.” Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science 47 (2): 203–219. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399808319857451.

- De Roo, G., J. Hillier, and J. Van Wezemael, eds. 2012. Complexity and Planning: Systems, Assemblages and Simulations. London and New York: Routledge.

- Eizenberg, E. 2019. “Patterns of Self-Organization in the Context of Urban Planning: Reconsidering Venues of participation”.” Planning Theory 18 (1): 40–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095218764225.

- Elsheshtawi, Y. 2004. Planning Middle Eastern Cities: An Urban Kaleidoscope in a Globalizing World. London and New York: Routledge.

- El-Taji, M. “Arab Local Authorities in Israel: Hamulas, Nationalism and Dilemmas of Social Change.” PhD diss., University of Washington. 2008.

- Falah, G. 1989. “Israeli ‘Judaization’ Policy in Galilee and Its Impact on Local Arab Urbanization.” Political Geography Quarterly 8 (3): 229–253.. https://doi.org/10.1016/0260-9827(89)90040-2.

- Falah, G. 2003. “Dynamics and Patterns of the Shrinking of Arab Lands in Palestine.” Political Geography 22 (2): 179–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0962-6298(02)00088-4.

- Hakim, B. 2001. “Julian of Ascalon’s Treatise of Construction and Design Rules from Sixth- Century Palestine.” Journal of the Society of Architecture Historians 60 (1): 4–25. https://doi.org/10.2307/991676.

- Hakim, B. 2008. “Mediterranean Urban and Building Codes: Origins, Content, Impact, and Lessons.” Urban Design International 13 (1): 21–40. https://doi.org/10.1057/udi.2008.4.

- Hakim, B. 2010. Arabic- Islamic Cities: Building and Planning Principles. New York: Routledge.

- Hakim, B. 2014. Mediterranean Urbanism: Historic Urban/Building Rules and Processes. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Hakim, B. 2019. Urban Rules and Process: Historic Lessons for Practice. Emergent City Press.

- ICBS (Israel Central Bureau of Statistics). 2024. Statistical Yearbook. Jerusalem: Central Bureau of Statistics Publications.

- Khamaisi, R. 1994. “Centrifugal Factors and Their Effect on the Structure of Arab Localities.” In The Arab Localities in Israel; Geographical Process, edited by D. Grossman and A. Meir, 114–127. Jerusalem: Magnes. in Hebrew.

- Khamaisi, R. 1999. The Provision of Public Land for Development in Arab Communities. Jerusalem: Floersheimer Institute for Policy Studies. in Hebrew.

- Khamaisi, R. 2000. “Something Went Wrong on the Way to the City.” Pnim- Journal of Culture, Society and Education 13:78–83. in Hebrew. https://haifa-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/f/71u575/Alma_IHP7127551850002792.

- Khamaisi, R. 2002. In Preparation for Expanding the Jurisdiction of Arab Communities in Israel. Jerusalem: Floersheimer Institute for Policy Studies. in Hebrew.

- Khamaisi, R. 2003. “The Mechanisms for Controlling the Land and Judaizing the Space.” In Bishem Habitahon, edited by M.-A. Haj and U. B. Eliezer, 421–448. Haifa: Haifa University.

- Khamaisi, R. 2004. Barriers to the Planning of Arab Localities in Israel. Jerusalem: Floersheimer Institute for Policy Studies. in Hebrew.

- Khamaisi, R. 2005. “Urbanization and Urbanism of Arab Settlements in Israel.” Horizons in Geography (Ofakim Be’geographia) 64–65:293–310. in Hebrew. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23716052.

- Lewin-Epstein, N., M. Al-Haj, and M. Semyonov. 1994. The Arabs in Israel in the Labor Market. Jerusalem: The Floersheimer Institute for Policy Studies. in Hebrew.

- Luz, N. 2007. On Land and Planning Majority-Minority Narrative in Israel: The Misgav-Sakhnin Conflict As Parable. Jerusalem: The Floersheimer Institute for Policy Studies. in Hebrew.

- Fakhoury T. Maisa, and N. Alfasi. 2017. “From Abstract Principles to Specific Urban Order: Applying Complexity Theory for Analyzing Arab-Palestinian Towns in Israel.” Cities 62:28–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2016.12.001.

- Fakhoury T. Maisa, and N. Alfasi. 2018. “When Contradicting Public Space Regimes Collide: The Case of Palestinian Israeli Towns.” The Geographical Journal 184 (4): 429–442. https://doi.org/10.1111/geoj.12265.

- Meir-Brodnitz, M. 1986. “The Suburbanization of Arab Settlements in Israel.” Horizons in Geography (Ofakim Be’geographia) 17-18:105–123. in Hebrew. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23697714.

- Moroni, S. 2010. “Rethinking the Theory and Practice of Land-Use Regulation: Towards Nomocracy.” Planning Theory 9 (2): 137–155. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095209357868.

- Moroni, S. 2015. “Complexity and the Inherent Limits of Explanation and Prediction: Urban Codes for Self-Organizing Cities.” Planning Theory 14 (3): 248–267. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095214521104.

- Nasser, K. 2012. Severe Housing Distress and Destruction of Arab Homes: Obstacles and Recommendations for Change. Haifa: Dirasat. in Hebrew.

- Pappe, I. 1992. The Making of the Arab-Israeli Conflict, 1947–1951. London and New York: I.B. Tauris.

- Portugali, J. 1999. Self Organization and the City. Berlin: Springer.

- Rauws, W. “Why Planning Needs Complexity: Towards an Adaptive Approach for Guiding Urban and Peri-Urban Transformations.” PhD diss., University of Groningen, 2015.

- Roy, A. 2005. “Urban Informality: Toward an Epistemology of Planning.” Journal of the American Planning Association 71 (2): 147–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944360508976689.

- Roy, A. 2011. “Slumdog Cities: Rethinking Subaltern Urbanism.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 35 (2): 223–238. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2011.01051.x.

- Salingaros, N. 2000. “Complexity and Urban Coherence.” Journal of Urban Design 5 (3): 291–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/713683969.

- Schnell, I., and A. Fares. 1996. Towards High-Density Housing in Arab Localities in Israel. Jerusalem: The Floersheimer Institute for Policy Studies. in Hebrew.

- Silva, P., and H. Farrall. 2016. “Lessons from Informal Settlements: A ‘Peripheral’ Problem with Self-Organising Solutions.” Town Planning Revie 87 (3): 297–319. https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.2016.21.

- Suhartini, N., and P. Jones. 2020. “Better Understanding Self-Organizing Cities: A Typology of Order and Rules in Informal Settlements.” Journal of Regional & City Planning 31 (3): 237–263. https://doi.org/10.5614/jpwk.2020.31.3.2.

- Talen, E. 2009. “Design by the Rules.” Journal of the American Planning Association 75 (2): 144–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944360802686662.

- Totry, M. 2023. “Power Dynamics and Self-Organizing Urbanism- a Comment.” Planning Theory 22 (4): 458–461. https://doi.org/10.1177/14730952231196332.

- Yashiv, E., and N. Kaisar. 2013. “Arab Women in the Israeli Labor Market: Characteristics and Policy Proposals.” Israeli Economic Review 10 (2): 1–41.

- Yazbak, M. 2004. “The Arabs in Haifa: From Majority to Minority, Processes of Change (1870-1948).” In The Israeli Palestinians: An Arab Minority in the Jewish State, edited by A. Bligh, 123–148. London: Frank Cass Publishers.

- Yiftachel, O. 1991. “State Policies, Land Control, and an Ethnic Minority: The Arabs in the Galillee Region, Isarel.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 9 (3): 329–362. https://doi.org/10.1068/d090329.

- Yiftachel, O. 1999. “Ethnocracy: The Politics of Judaizing Israel/Palestine.” PRAXIS International 6 (3): 364–390. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8675.00151.

- Yiftachel, O. 2000. Land, Planning and Equity: The Division of Space Between Jews and Arabs in Israel. Tel Aviv: Adva Center.

- Yiftachel, O. 2009. “Theoretical Notes on “Gray Cities”: The Coming of Urban Apartheid?” Planning Theory 8 (1): 88–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095208099300.