ABSTRACT

Although the literature widely acknowledges the benefits of formative writing assessment in daily teaching, there is limited understanding of how frontline teachers implement it and the reasons behind their approach, particularly in EFL secondary school contexts where assessment has predominantly served selective purposes. Drawing on interviews, voice memos, document, and relevant artefacts, this study examined how a teacher implemented formative writing assessment and what influenced her decision-making process in a public secondary school in mainland China. The research findings shed light on how teachers working with beginner-level students can draw on formative writing assessment to develop students’ L2 writing skills and on factors that might influence the realisation of formative writing assessment. The study also offers pedagogical recommendations for teachers and teacher educators and suggestions for future research.

Introduction

Teaching second language (L2) writing is full of challenges, as teachers need to not only help students develop L2 writing skills but also enhance their overall English proficiency (Hyland and Hyland Citation2019). Considering those challenges, researchers have for decades encouraged teachers to incorporate formative writing assessment into their daily teaching (Gan and Leung Citation2020). Formative assessment is a pedagogical intervention where teachers, along with students themselves, can elicit, interpret, and use evidence about student achievement to enhance the learning process (Black and Wiliam Citation2009). In L2 writing contexts, formative assessment refers to low-stakes assessment designed to measure students’ progress and proficiency over time (Lee Citation2017). Compared to summative assessment, formative assessment provides teachers with autonomy to align the content, objectives, scoring, and means of delivery with their own teaching goals (Crusan, Plakans, and Gebril Citation2016). It has the potential for promoting students’ motivation in learning and augmenting teachers’ capacities to adapt their pedagogy in response to students’ advancement (Lee Citation2017).

However, despite the well-documented advantages in research, there is limited knowledge regarding frontline teachers’ beliefs about and practices of formative writing assessment, particularly in EFL secondary school settings where there is a strong emphasis on summative assessment and scoring (Wang, Lee, and Park Citation2020). EFL secondary school classrooms are unique in that students are typically still in the early stages of learning English and have few opportunities to practise L2 writing outside of school (Lee Citation2017). Under such circumstances, the role teachers play in shaping students’ learning experiences and learning outcomes becomes more crucial, as they are one of the few reliable sources for students to learn L2 writing skills and receive feedback on their written work.

Therefore, it is of great pedagogical and practical significance to explore how frontline teachers utilise the potential of formative assessment in promoting students’ L2 writing learning engagement and outcomes, as well as the rationales for their decisions. The findings can offer valuable insights for teachers in similar contexts, helping them design and implement formative writing assessment in their own classrooms. Additionally, these findings can provide empirical evidence for teacher educators and researchers in the field of L2 writing to develop more effective pedagogical strategies.

Teachers’ beliefs about and practices of formative writing assessment

Teachers’ beliefs refer to ‘what teachers think, know and believe’ (Borg Citation2015, 1). It has been reported that teachers’ beliefs and practices can mutually influence each other, with contextual factors serving as a mediator. From a review of the limited literature, two observations can be made.

First, teachers were found to approach formative writing assessment flexibly based on their own needs, which aligns with Bennett’s (Citation2011) observation that formative writing assessment is still a work-in-progress both conceptually and practically. For example, at the pre-writing stage, teachers could provide students with relevant instructional support targeting the writing task and guide them through possible issues that they might face during writing (Lee Citation2011). At the post-writing stage, teachers could expose students to feedback from various sources such as teachers, students themselves, and their peers (Lam Citation2015). Teachers could also encourage students to keep portfolios to evaluate their continuous development, with the aim of motivating students to be more actively engaged in their learning (Mak and Wong Citation2018).

Second, previous research has also found that the lack of L2 writing assessment literacy (Lee Citation2021) and contextual factors such as the exam-driven culture (Lam Citation2015) had a negative influence on teachers’ capacity to effectively implement and utilise formative writing assessment. For example, Wang, Lee, and Park (Citation2020) investigated the relationship between Chinese EFL university teachers’ beliefs and practices of formative writing assessment. The authors reported that there were discrepancies between teachers’ beliefs and practices, which could be explained by the influence of contextual factors such as the lack of assessment training, characteristics of students, and the requirements of public English tests. Similar findings can also be seen in the study conducted by Crusan, Plakans, and Gebril (Citation2016) in tertiary institutions in ESL and EFL contexts. The authors also reported that a lack of writing assessment literacy training and context-specific factors affected the participants’ beliefs and self-reported practices.

However, while the existing literature offers valuable insights into the factors that may influence teachers’ beliefs and practices, there is still limited understanding of how teachers actually design and implement formative writing assessment, as well as how they interpret their practices in real-world situations, with perhaps only one notable exception. Lee (Citation2011) conducted a single case study investigating how a L1 English speaker teacher approached formative writing assessment in Grade 7 in Hong Kong. The participant’s implementation of formative writing assessment included promoting multiple drafting, giving selective and unfocused error feedback, spending more time on pre-writing, using feedback forms containing pre-established assessment criteria, incorporating self- and peer-evaluation, and withholding grades. Although Lee’s study did not explore the participant’s beliefs, it provided some details about how formative writing assessment can be realised in a secondary school setting in an exam-driven culture.

Considering the distinctiveness of teachers’ beliefs and the personalised and context-dependent approaches to formative writing assessment, it is necessary to carry out more targeted investigations to understand not only teachers’ intentions, but also their interpretation and the reasons for their practices.

Bearing this in mind, this study set out to shed light on the intricacies of a teacher’s beliefs about and practices of formative writing assessment in situ. While a single case study is not sufficient to draw general conclusions, it offers valuable insights that readers can use to assess the relevance of the study in their own context.

Formative writing assessment is here viewed as a two-stage approach encompassing assessment design in the pre-writing phase and feedback provision in the post-writing phase. The guided questions are as follows:

What are the beliefs and practices of an EFL teacher regarding formative writing assessment in a public secondary school in mainland China?

What factors influence the teacher’s decision-making process regarding formative writing assessment?

The study

This single case study was conducted in mainland China. Nelly (a pseudonym) volunteered to participate in this research. She completed a two-year master’s ELT programme in the United States and then started teaching English in a key public secondary school in mainland China. Key high schools are known for accepting high-achieving students and having access to ample resources.

During the data collection period, Nelly taught two Grade 7 classes, each with approximately 55 students. Her students’ proficiency in English was significantly higher than the average level for their grade, although they were still at the beginner level. Additionally, Nelly mentioned that the school does not have any particular guidelines or requirements for teaching methods, giving teachers the freedom to explore and experiment with new approaches to teaching. These factors laid the groundwork for Nelly to implement formative writing assessment in her classroom. Besides teaching, Nelly also served as the director for Grade 7. The teaching and administrative responsibilities contributed to her hectic schedule.

In mainland China, students must take the High School Entrance Exam (HSEE) after finishing Grades 7–9 to attend senior high school (Grades 10–12). The HSEE results determine the level of senior high school a student can attend. Taking this into consideration, Nelly designed the formative writing assessment project with the objective of preparing students for a common writing topic in the HSEE.

Data were collected from multiple sources: interviews, voice memos, artefacts such as the writing assignment and writing response samples, and relevant documents such as syllabus and teaching plans. This served the purpose of data triangulation; it also aimed to collect rich and detailed information to contextualise the study. All the data were collected online via Microsoft Teams (for interviews) and OneDrive Business (for other data), in accordance with the guidance of the author’s institution.

Three rounds of semi-structured interviews were undertaken, which were conducted in Chinese and audio-recorded with Nelly’s permission. In the first interview (50 min), Nelly shared her design plan, including the overarching writing topic, how many writing tasks she would like to include, and her teaching objectives. The second interview (170 min) generated information about Nelly’s educational experiences, classroom practices, and professional contexts. Then, the third interview (60 min) was conducted similarly to the second one, aiming at discussing any new topics found from other data sources and capture any changes or developments in Nelly’s beliefs and practices.

Nelly was also encouraged to record at least one voice memo in which she could share anything that she thought was relevant to this research. This aimed to allow Nelly to share more information that might otherwise be overlooked during the time lapse between the interviews. In practice, Nelly sent two voice memos (2 minutes each) where she recorded her comments on her students’ learning attitudes, information about her work schedule, and reflections on her teaching.

The interviews and voice memos were transcribed and translated by the author and sent to Nelly for checking. Then, the transcripts were analysed via reflective thematic analysis, including ‘familiarisation; coding; generating initial themes; reviewing and developing themes; refining, defining and naming themes; and writing up’ (Braun and Clarke Citation2021, 39). This method was adopted as it values the interpretations of researchers and allows researchers to develop themes under the guidance of a central theory, which in this case was language teacher cognition framework (Borg Citation2015). At the same time, this method allows the coding process to be open to new themes.

The initial coding labels were created regarding the participant’s schooling experiences, professional learning, classroom practices, and contextual factors. New labels were created or amalgamated to capture emerging themes. For example, the code label ‘professional learning experiences’ was further categorised as ‘academic learning’ and ‘lived experiences’. As coding progressed, a new label ‘practicum observation’ was added.

The formative writing assessment project Nelly designed lasted one semester. It was divided into two sections, with the objective of providing students with useful vocabulary, sentence structures, and phrases before assessing their ability to write an essay independently. The first section was intended to be completed before the midterm, while the second section was planned for completion before the final exam. The overarching writing topic was to introduce a traditional Chinese festival in English. In the following, I discuss her beliefs and practices phase by phase.

Pre-writing phase: ample writing chances with decreasing amounts of scaffolding

In the pre-writing phase, Nelly believed that it was important to give students ample opportunities to practise writing while also provide them with appropriate scaffolding. Regarding the former, Nelly explained that ‘If I don’t ask them to write something in English, they barely have opportunities to do this. They have few chances to use English or be exposed to English in their daily life’. Regarding the latter, Nelly noticed that her students were able to express some of their ideas in English, while they often felt intimidated to do so. As a response, she decided to provide appropriate amounts of scaffolding to help them overcome the fear of writing in English. However, Nelly also mentioned that the scaffolding she provided should be gradually reduced as the learning progressed, to encourage her students to write independently.

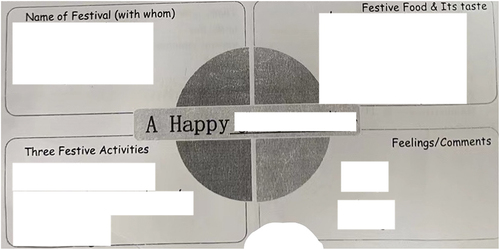

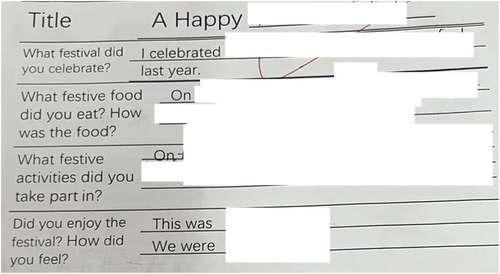

Nelly translated her belief to practice by giving guidance in a step-by-step manner with less guidance as the assignments progressed. In detail, in Preliminary Writing Tasks 1 and 2 (), students were supposed to fill in one or two blanks to complete a sentence. The difference between the two tasks was that the sentences in Task 2 were longer and, consequently, more demanding. The scaffolding included illustrations, corresponding vocabulary, Chinese translations, and sample sentences.

With reference to Task 3 (), Nelly reduced the amount of scaffolding by providing a framework with four keywords for students to brainstorm. Based on the brainstorming results, students were supposed to finish Task 4 (), where they were expected to express their ideas in full sentences with content prompts and occasional language support. For the final writing task in this formative writing assessment (), Nelly assigned a new writing prompt that also focused on introducing a festival. At this time, however, she only provided content prompts without any language support.

Table 1. Final writing task.

Post-writing phase: prioritising teachers’ written corrective feedback while experimenting with student-initiated feedback

In the post-writing phase, Nelly incorporated two feedback approaches: teachers’ written corrective feedback (WCF) and student-initiated feedback. When reflecting on her decision, Nelly highlighted the pedagogical value and effectiveness of giving WCF. Considering that her students were still at the beginning level and were not able to identify and self-edit errors by themselves, Nelly mentioned that she gave WCF on all errors she could identify. This echoes findings from previous research, where the participating teachers were reported to be devoted to providing WCF and thought of it as a premise for improving students’ L2 writing skills (Cheng, Zhang, and Yan Citation2021).

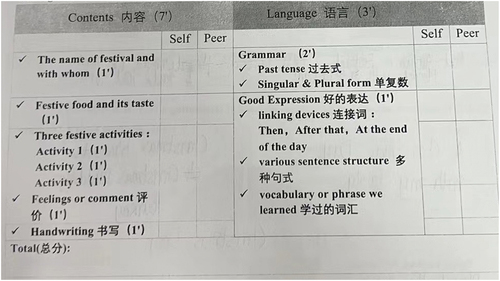

In addition, Nelly actively involved her students in the feedback process. She utilised two kinds of student-initiated feedback, namely self-assessment and peer feedback. As an attempt to prepare students with basic skills to assess their own and others’ writing, Nelly adapted the rubric used in the HSEE to a student-friendly and task-specific version (). This rubric was also designed to make writing requirements explicit, which could help students know ‘what teachers are looking for in their writing’.

Nelly emphasised that student-initiated feedback was still ‘in the experimental stage’ because many of her students lacked the English proficiency necessary to implement them. In practice, her WCF played a dominant role in helping students correct errors. However, Nelly commented that ‘Writing assessment literacy is an important ability. I believe that although my students may not find it useful for now, they will benefit from it in the long run’.

Factors influencing Nelly’s beliefs and practices

Three important influencing factors will be discussed in turn.

Nelly’s prior learning experiences regarding L1 and L2 writing were found to contribute to her belief in providing students with ample writing chances. In particular, Nelly credited her proficiency in L1 writing to the ample opportunities she had to practise writing in L1. However, in contrast, she rarely had the opportunity to practise L2 writing, which she regarded as ‘a pity’. Critically reflecting on her learning experiences of L1 and L2 writing, Nelly decided to encourage her students to write as much as possible. The findings corroborate the influence of teachers’ L1 and L2 writing and literacy-learning experiences on their pedagogical decisions, concurring with Yigitoglu and Belcher’s (Citation2014) study.

Another factor was Nelly’s experiences in her teacher education programme. Specifically, she was influenced by two interrelated sources: the teaching philosophies she developed during the coursework and the opportunities for teaching practice that were integrated into the programme.

Nelly referred to two key teaching philosophies that guided her practices. First, she mentioned that ‘“Student-centred teaching” is the overarching guidance of my teaching right now’. Nelly further explained that one way to apply this teaching philosophy was to ‘always remember to let students use English’, which explained her firm belief in providing ample writing opportunities for students. Second, Nelly noted that she was also guided by her belief in providing ‘contingent and individualised scaffolding’ to meet her students’ needs. She attributed this philosophy to her studies in ELT assessment methods, where she gained fundamental knowledge and skills in assessment design.

Nelly also referred to the influence of her classroom observations in local schools and her one-semester internship experience in a local elementary school in the United States. She emphasised that these experiences allowed her to ‘learn from experienced local teachers in a real-world teaching context’. As an illustration, Nelly referred to her design of a student-friendly assessment rubric: ‘The rubric was something I learnt in classroom observations and my teaching practicum’.

Within the limited literature that concerns teachers who teach across different pedagogical contexts, the disconnect between theory and practice has been reported (see, for example, Hennebry-Leung et al. Citation2019). Although such a disconnect was also found in this study, it is worth noting that Nelly successfully drew on her learning (both from coursework and integrated teaching practices) to design and implement a formative writing assessment project in her teaching context. This finding points to the benefits of providing student teachers with hands-on practicum opportunities in teacher education; it also highlights the potential for these practicum chances to bridge the gap that may exist between theory and practice.

However, it is important to mention that Nelly’s beliefs about and practices of formative writing assessment were mainly influenced by her teaching philosophies regarding general ELT and the observations she made through relevant practices in local schools, rather than through coursework. As Nelly explicitly mentioned, the courses she took, including those designed for assessment, ‘didn’t cover L2 writing … were more about vocabulary, reading, and speaking’. While the participant was able to apply alternative sources of knowledge to her professional work and partially mitigate the negative impact, the finding highlights the necessity of providing L2 writing pedagogy training in teacher education programmes.

Two types of factors were found to strongly influenced Nelly’s beliefs and practices. One was related to individual student variables, such as their English language proficiency levels, learning attitudes, and learning needs. Those factors influenced every aspect of Nelly’s approach to formative writing assessment. In Nelly’s own words, ‘Students are always at the top of my priority list. I adapt my teaching methods to meet their needs and support them’.

The other one related to the teaching context, including the HSEE and heavy workload. In particular, Nelly followed the guidance of the HSEE when designing this formative writing assessment project. This was reflected in her choice of writing topic and the use of the official rubric when assessing students’ final writing products. Also, Nelly mentioned that due to her busy schedule, ‘Trying out just one formative writing assessment project was the best I could do for now’.

Although the influence of those factors was also reported in previous research (e.g. Cheng, Zhang, and Yan Citation2021; Lee Citation2011), it deserves notice that instead of viewing these factors as constraints, Nelly flexibly adjusted her teaching methods to address those challenges. Despite her hectic schedule, she managed to prepare students for an exam-required writing task through one formative writing assessment project. While no empirical evidence was available to assess the effectiveness of Nelly’s approach on the development of her students’ L2 writing skills, her practice demonstrated the feasibility of applying formative writing assessment within an exam-focused culture.

Conclusion

By focusing on a teacher’s approach to formative writing assessment in an EFL secondary school, this study provides information regarding how formative writing assessment can be realised in an exam-driven culture and what factors might influence teachers’ beliefs and practices. The findings also demonstrate the feasibility of applying formative writing assessment in EFL secondary school settings with students at the beginning level of English. Based on the research findings, teachers in similar contexts can begin to reflect critically on the impact of their own literacy learning experiences and actively participate in the implementation of formative writing assessment in future instruction.

However, this study indicates that L2 writing pedagogy and assessment skills might be an under-addressed topic in certain teacher education programmes. In response, teacher educators might consider exposing students to relevant pedagogical strategies, theories, and frameworks available in the existing L2 writing research (e.g. Lee Citation2021). This could be a good starting point for promoting student teachers’ agency and capabilities in implementing innovative teaching methods in their future teaching.

This study did not investigate how formative writing assessment affects students’ writing performance. It remains unknown if or how much this approach to assessment helps students develop their L2 writing skills. It would be helpful to include this information in future research to better understand the effectiveness of formative writing assessment. This line of research will provide teachers with more information to consider when integrating this innovative assessment method into their teaching, while also helping teacher educators better prepare teachers with the necessary assessment competencies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

For the purpose of open access, the author has applied a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Xiaohan Liu

Xiaohan Liu is currently a PhD candidate in Education at the University of Exeter, UK. Her research interests include language teacher cognition, L2 writing, TESOL/TEFOL, language teacher education, and teacher professional development.

References

- Bennett, R. E. 2011. “Formative Assessment: A Critical Review.” Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice 18 (1): 5–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2010.513678.

- Black, P., and D. Wiliam. 2009. “Developing the Theory of Formative Assessment.” Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability 21 (1): 5–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-008-9068-5.

- Borg, S. 2015. Teacher Cognition and Language Education: Research and Practice. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2021. “Can I Use TA? Should I Use TA? Should I Not Use TA? Comparing Reflexive Thematic Analysis and Other Pattern-Based Qualitative Analytic Approaches.” Counselling and Psychotherapy Research 21 (1): 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12360.

- Cheng, X., L. J. Zhang, and Q. Yan. 2021. “Exploring Teacher Written Feedback in EFL Writing Classrooms: Beliefs and Practices in Interaction.” Language Teaching Research 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688211057665.

- Crusan, D., L. Plakans, and A. Gebril. 2016. “Writing Assessment Literacy: Surveying Second Language Teachers’ Knowledge, Beliefs, and Practices.” Assessing Writing 28:43–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2016.03.001.

- Gan, Z., and C. Leung. 2020. “Illustrating Formative Assessment in Task-Based Language Teaching.” ELT Journal 74 (1): 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1093/ELT/CCZ048.

- Hennebry-Leung, M., A. Gayton, X. A. Hu, and X. Chen. 2019. “Transitioning from Master’s Studies to the Classroom: From Theory to Practice.” TESOL Quarterly 53 (3): 685–711. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.505.

- Hyland, K., and F. Hyland. 2019. “Contexts and Issues in Feedback on L2 Writing.” In Feedback in Second Language Writing: Contexts and Issues, edited by K. Hyland and F. Hyland, 1–22. 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108635547.003.

- Lam, R. 2015. “Language Assessment Training in Hong Kong: Implications for Language Assessment Literacy.” Language Testing 32 (2): 169–197. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532214554321.

- Lee, I. 2011. “Formative Assessment in EFL Writing: An Exploratory Case Study.” Changing English: Studies in Culture and Education 18 (1): 99–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/1358684X.2011.543516.

- Lee, I. 2017. Classroom Writing Assessment and Feedback in L2 School Contexts. Singapore: Springer.

- Lee, I. 2021. “The Development of Feedback Literacy for Writing Teachers.” TESOL Quarterly 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.3012.

- Mak, P., and K. M. Wong. 2018. “Self-Regulation Through Portfolio Assessment in Writing Classrooms.” ELT Journal 72 (1): 49–61. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccx012.

- Wang, L., I. Lee, and M. Park. 2020. “Chinese University EFL Teachers’ Beliefs and Practices of Classroom Writing Assessment.” Studies in Educational Evaluation 66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2020.100890.

- Yigitoglu, N., and D. Belcher. 2014. “Exploring L2 Writing Teacher Cognition from an Experiential Perspective: The Role Learning to Write May Play in Professional Beliefs and Practices.” System 47:116–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2014.09.021.