Abstract

This paper examines the University of Sydney Library’s development and piloting of a methodology to survey its Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural collections, to enhance catalogue metadata and allow culturally sensitive material to be identified and protected. The research falls broadly within the interpretivist epistemology and draws methodologically on Participative Action Research. The pilot survey was conducted using a qualitative, collection-based approach, more specifically Direct Collection Analysis. A broad syntax was used to identify cultural content within the catalogue metadata, and items individually examined to determine the nature of their contents. The findings surface the benefits and shortcomings of the initial methodology. It is recommended future surveys be conducted using more specific terminology checklists and undertaken by a dedicated team that has received care and handling training for cultural materials and is led by an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander expert in cultural collections.

Introduction

Australian Universities are encouraged to provide environments that support staff and students to grow their knowledge of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories, cultures and practices, and to demonstrate culturally respectful approaches in their engagement and work with Indigenous stakeholders (Universities Australia, Citation2011, p. 6). This also extends university libraries. Several Australian academic libraries have begun working to improve the cultural safety of their collections, services, and spaces for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients. This includes developing a better understanding the nature of the cultural heritage materials they hold and improving the catalogue metadata to more accurately describe the contents of these collections. This paper examines the methodology developed by the University of Sydney Library to survey its Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural collections, the results of a pilot conducted using the methodology, and reflections on how to progress with the surveying of the collection.

The University of Sydney Library, located in New South Wales, Australia, is one of the largest and oldest academic libraries in the southern hemisphere. The Library’s operations are spread over 13 physical sites, and in 2022 it had 193 full-time equivalent staff. Its collection of nearly 5 million items includes 2.7 million digital titles and 1.9 million physical titles. It’s rare and special collections incorporate a wide range of resources including legacy theses that document some of the earliest Western accounts of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures. Some of these contain culturally sensitive material.

At the University of Sydney, the Office of the Deputy Vice Chancellor Indigenous Strategy and Services (DVCISS) leads the development of culturally competent policy and practice. Within DVCISS, the National Center for Cultural Competence provides opportunities for the University community and all Australians to develop and integrate intercultural competence through teaching, research and engagement programs that place “the University of Sydney at the forefront of addressing cultural competence in Australia” (National Center for Cultural Competence, n.d.).

Inspired by engagement with the program of cultural learning opportunities offered by the National Center for Cultural Competence, the University of Sydney Library recognized the need to develop cultural protocols to articulate its commitments to embed and promote culturally competent practice across its services, spaces and resources. Founded in sectoral best practice, informed by consultation with the University’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community, and led by a Wiradjuri expert in cultural collections The University of Sydney Library’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Cultural Protocols were a first for Australian academic libraries (University of Sydney Library & Sentance, Citation2021). The scope of the Protocols includes the protection of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural heritage and traditional knowledge, and providing a culturally safe environment for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients (2021). They recognize that The University of Sydney Library has a “responsibility to care for, preserve and share the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural knowledges within its collection in a manner that is secure, trusted and respectful” to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities (University of Sydney Library & Sentance, Citation2021, p. 6).

The University of Sydney Library is custodian to significant and unique cultural heritage collections by and about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Given this, the Protocols include an undertaking that the Library will survey its collections to identify materials containing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural heritage content (University of Sydney Library & Sentance, Citation2021, p. 14). The intent of the survey is for the Library to better understand the cultural heritage materials it holds, to provide the information needed to enhance catalogue metadata relating to those resources, and to allow potentially culturally sensitive material, such as secret, scared or offensive material to be identified (University of Sydney Library & Sentance, Citation2021). This, in-turn will improve the discoverability of the Library’s cultural heritage collections, inform culturally safe collection management decisions, and provide a basis for collection development.

Before embarking on a project to survey the wider collection for cultural heritage content, the Library set out to develop and pilot a methodology to survey its Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural collections during 2021–2022. This paper details how the methodology was developed, the results, a reflection on lessons learned, and opportunities to improve the initial methodology. Given that this project was progressed during the COVID-19 pandemic, and that the work needed to be done remotely, the sample selected for the pilot was the collection of legacy theses published prior to 1980, that had been digitized, and were known to contain cultural heritage materials that were potentially sensitive in nature.

The focus of the pilot survey and of this paper is the Australian academic library context and collections containing content by or about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples and their cultures. The term Indigenous, also used in this paper, is used to denote Indigenous or First Nations Peoples globally, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples.

Literature review

This literature review is situated within the broad concept of cultural competence and its growing importance in universities and their libraries, particularly within Australia. The review examines the complexities of cataloguing and managing Indigenous cultural heritage collections within the western library paradigm. Tensions between Indigenous and western ontologies, information classification systems, concepts of intellectual property and knowledge ownership point to the need for academic libraries to review their classification and description of Indigenous cultural collections, with the aim of improving the cultural appropriateness and discoverability of collection records. A first step to achieving this is for libraries to survey their collections to better understand what content by and about Indigenous cultures and histories is contained within their collections. A literature search is consequently undertaken to identify approaches to surveying Indigenous cultural collections in academic libraries.

Prioritizing cultural competence in Australian Universities and academic libraries

Over the past two decades, scholarship about equity and inclusion in universities has grown exponentially and institutions have demonstrated a strengthening commitment to creating environments that are welcoming and inclusive for all (Linder & Cooper, Citation2016, p. 379). It is well recognized that universities and their organizational units, including academic libraries and the professionals working in them, have a duty of care to the diverse students, staff and the wider communities they serve (Pecci et al., Citation2020, p. 59), and to prepare graduates to work effectively in culturally diverse workplaces (Puckett, Citation2020, p. 8). To succeed in fulfilling these responsibilities, universities must develop and embed culturally competent practice at the institutional, organizational and individual levels (Pecci et al., Citation2020, p. 59).

Universities Australia has published a national best practice framework to encourage supportive environments for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander staff and students, and it provides a theoretical and evidential basis for cultural diversity in the higher education setting (2011). The framework recommends a cultural competence approach given its holistic nature (Universities Australia, Citation2011, p. 6). It builds upon earlier cultural competence models (Alizadeh & Chavan, Citation2016; Holt & Seki, Citation2012; Johnson et al., Citation2006; Leung et al., Citation2014; Pecci et al., Citation2020; Shen, Citation2015) and the consensus drawn from these that cultural competence incorporates the cultural knowledge, skills and attributes that allow individuals to think and act in culturally appropriate ways, and to perform effectively in intercultural settings (Frawley et al., Citation2020; Johnson et al., Citation2006; Leung et al., Citation2014; Martin & Mirraboopa, Citation2003).

In the Australian higher education context, culturally competent environments exist where university staff and students develop knowledge and understanding of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories and cultures, and demonstrate culturally respectful approaches in their engagement and work with Indigenous stakeholders (Universities Australia, Citation2011, p. 6). From an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspective, cultural competence is informed by knowing culture, customs, history and beliefs; being authentically self-reflective and aware of one’s own cultural lens, and remaining open to examining one’s values and bias; and doing, or acting and behaving in culturally appropriate ways (Commonwealth of Australia [CoA], Citation2015; Frawley et al., Citation2020, p. 4; Martin & Mirraboopa, Citation2003, pp. 209–210). It is evident that many Australian universities have indeed adopted a cultural competence approach to embedding best practice and raising awareness among students and staff working, studying and researching in intercultural settings (Deakin University, n.d.; James Cook University, n.d.; McKay, Citation2018; University of Newcastle, Citation2020; University of Queensland, n.d.-a; University of Sydney, n.d.).

Australian academic libraries have recently begun to articulate their commitment to embedding culturally competent practice through the publication of cultural protocols (University of Sydney Library & Sentance, Citation2021; University of Technology, Citation2022), or policies and guidelines (University of Adelaide, Citation2023; University of Queensland, n.d.-b). These protocols and statements draw on principles from the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Library and Information Resources Network Protocols for Libraries, Archives and Information Services [ATSILIRN] (2012), and the Indigenous cultural intellectual property publications of Terri Janke (Citation2022).

Complexities of managing Indigenous cultural heritage collections within Western academic library paradigms

Differing ontological paradigms

Indigenous Knowledge refers to the complex socio-cultural and political systems that were the cornerstones of Indigenous cultures prior to European arrival (Simpson, Citation2004). Where Indigenous perspectives present a holistic worldview in which humans are contextualized within their natural and spiritual surroundings and ownership of information is collective, western knowledge stands in epistemological contrast and information is viewed as proprietary and taxonomic (Miniter & Vo-Tran, Citation2021). These two systems differ in their approaches to information classification and the delineation of knowledge. As such, the hierarchical, compartmentalized nature of western library classification systems is not compatible with and marginalizes Indigenous knowledge frameworks (Masterson et al., Citation2019; Olson, Citation1998). For academic librarians working to preserve Indigenous cultural heritage, cultural competence involves critically challenging professional values that may represent western colonialised views, advocating for the security and safety of the cultural collections their libraries house, and that traditional cultural norms are prioritized in the way collections are managed, accessed and used (Roy, Citation2015, p. 199).

Preservation of cultural heritage materials both physically and digitally in library collections provides long-term availability, and the possibility of greater access by Indigenous communities to information that is culturally and historically important to them (Roy, Citation2015, p. 198). While memory institutions including libraries play an invaluable role in the preservation of the world’s rich cultural heritage, Indigenous communities continue to voice concern that western intellectual property (IP) law treats traditional cultural expression as being in the public domain, and that this does not take adequate account of the interests, obligations and rights of the communities to whom that information has been entrusted under customary law (World Intellectual Property Organisation [WIPO], 2005). Article 31 of the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples recognizes their right to “maintain, control, protect and develop their cultural heritage, traditional knowledge and traditional cultural expressions…and develop their intellectual property over such cultural heritage, traditional knowledge, and traditional cultural expressions” (United Nations, Citation2007). Tensions exist between these moral rights and the prescriptions of IP law. IP law does not the protect traditional owners’ communal rights to their cultural heritage, and it instead assigns rights to those who collect and document information about Indigenous people, gather their artifacts and record their cultural heritage material (Kearney & Janke, Citation2018, p. 97; WIPO, Citation2005). This is at odds with concepts of Indigenous cultural intellectual property (ICIP) rights that are based in customary law. The publication of and access to traditional knowledges becomes especially problematic where information that would customarily be considered secret or sacred should be protected and preserved for certain segments of society (Kearney & Janke, Citation2018, p. 97; Vézina, Citation2016, p. 97; WIPO, Citation2005). Consultation between concerned Indigenous communities and academic libraries has led to instances of access limitation or censorship of culturally sensitive materials. Reasons for taking these steps are complex and various, including content governed by customary obligations concerning the sacredness and secretness of certain cultural knowledge, the cultural misappropriation of knowledge in ways not intended or approved by its owners, and harmful or hateful literature about cultural groups (Lee, Citation2008, p. 155; Vézina, Citation2016, p. 15).

The impacts of Western approaches to classification and description

The historical Indigenous cultural heritage content held by Australian libraries often contains accounts collected by third parties such as colonizers, government officials, missionaries and anthropologists about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, with very few materials being written by Indigenous authors (Nakata, Citation2007, p. 7; Nakata et al., Citation2006, p. 10). Although this content that documents colonial history can often be traumatic from the perspective of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, these materials can contain important information about community and family, and offer opportunities to reconnect with language and cultural practice (Thorpe & Galassi, Citation2018, p. 182; WIPO, Citation2005). Access to materials that document colonial history is also of vital assistance to First Nations peoples seeking information to redress matters such as Native Title claims and the Stolen Generations (Australian Library and Information Association [ALIA], Citation2019, p. 6; Thorpe & Galassi, Citation2014, p. 82). For many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, documented materials held in Australian library collections is a “tenuous thread that connects present generations with traditional heritage” (Nakata & Langton, Citation2006, p. 4).

Many Indigenous people are unaware of the wealth of Indigenous cultural heritage materials held by libraries, and libraries are also not familiar with the breadth and depth of this content within their collections (Nakata & Langton, Citation2006, p. 4). Barriers to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people accessing materials held by libraries about their history and culture include the dispersion of materials about community across collecting institutions both within Australia and internationally (Thorpe & Galassi, Citation2014, p. 83), and the misalignment between standards of practice in western libraries in the way collections and managed and catalogued, and the interests and concerns of Indigenous peoples relating to cultural heritage materials held by libraries (Nakata & Langton, Citation2006, p. 3).

As recent scholarship reveals, challenges concerning the classification and description of Indigenous collections using western library standards are multi-faceted (Duarte & Belarde-Lewis, Citation2015; Howard & Knowlton, Citation2018; Lee, Citation2008; Nyitray & Reijerkerk, Citation2021). In their review of nine case studies documenting the development of alternative classification systems for Indigenous Knowledge collections, Miniter and Vo-Tran note three primary motivations for change: stigmatization, offensive and incorrect description of Indigenous Knowledge concepts; incorrect or incoherent classification affecting discoverability; and devaluing of Indigenous knowledge through the exclusion of relevant epistemologies from classification systems (2021). Rules governing the cataloguing of material and assigning call numbers are rigidly tied to western scholarly disciplines, and content is siloed by knowledge organization systems such as the widely used Library of Congress Classification (Howard & Knowlton, Citation2018, p. 74). It is difficult for non-Indigenous cataloguers to accurately assign call numbers when working with Indigenous cultural content with which they are unfamiliar, potentially resulting in the inaccurate cataloguing; furthermore, the segregation of content by subject can be incompatible with Indigenous ontologies that represent a more holistic worldview (Lee, Citation2008, p. 157). For example, the restrictive classification provided by the Dewey Decimal System does not reflect Aboriginal approaches to health and healing that integrate physical, emotional, spiritual and social aspects, and relationship to the land (Linton & Ducas, Citation2017); nor does it recognize the mathematical concepts of the Yolŋu people of East Arnhem Land (Christie, Citation2007). Historical subject headings such as those derived from the Library of Congress also ‘other’ historically marginalized people through terminology that is limited, inconsistent, dated and presents a white, male Eurocentric viewpoint (Howard & Knowlton, Citation2018, p. 77; Lee, Citation2008, p. 157; Nyitray & Reijerkerk, Citation2021, p. 29). The use of value-laden or sanitizing terms to describe subjects related to Indigenous peoples and their oppression impedes their discoverability (ATSILIRN, Citation2012; Reijerkerk & Nyitray, Citation2023, p. 29). An example of a subject heading that can obscure challenging information is ‘Aboriginal Australians, Treatment of’ which, as Moorcroft points out, also covers information about genocide (1992).

Access to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural heritage collections can be substantially improved by better identifying items through the use of geographic, language and cultural identifiers such as the words that cultural groups use to describe their culture and themselves (ATSILIRN, Citation2012). The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) Pathways thesauri provide culturally appropriate subject headings to more accurately describe Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and issues (2015). In particular, Indigenous languages are intrinsic to Indigenous Knowledge, and their correct classification is paramount to the culturally appropriate management of collections and their discoverability (Masterton et al., 2019). Since 2018 the AIATSIS Australian Indigenous Language Codes (AustLang) have been included in the Library of Congress’s MARC Language Codes list (NSLA, n.d.). National Indigenous thesauri relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and issues can be used to inform the culturally appropriate description of new materials as well as to remediate old records and improve the description of materials with unsuitable subject headings (ATSILIRN, Citation2012; NSLA, n.d.).

Australian academic libraries can leverage these recognized standards and resources to enrich their catalogue metadata and to use this enhanced classification and description to develop an improved understanding of the scope and nature of Indigenous cultural heritage collections within their care. This, in-turn will allow them to respond to cultural heritage collections in culturally appropriate ways, and to better manage content that is culturally sensitive, sacred, or secret according to traditional laws of the community from which is originates.

Approaches to assessing and surveying Indigenous collections

The tensions arising at the intersection of Indigenous and western epistemologies are well documented, as are related problems that result when western library collection management and cataloguing processes are overlayed on Indigenous Knowledge. Given this, it cannot be assumed that the metadata contained within academic library catalogues accurately describes cultural collections from and Indigenous perspective. While guidance on the ethical management of Indigenous collections is provided in documents such as the ATSILIRN Protocols (2012) and Protocols for native American Archival Materials (Circle, Citation2007), they presume a deep understanding by libraries of their collections (Reyes-Escudero & Cox, Citation2017, p. 131). The formation of this understanding requires Indigenous perspectives within the collection to be surfaced, and to be made discoverable within the catalogue metadata. For this to be achieved libraries must comprehensively examine the records of historically catalogued holdings for Indigenous cultural heritage content, with a view to improving catalogue metadata. A collection survey presents a valuable starting point for libraries wishing to form a holistic view of existing Indigenous collections.

Understanding the collection through analysis can be broadly approached in one of four ways—collection-based, use and user-based, qualitative or quantitative (Johnson et al., Citation2005). A qualitative, collections-based survey provides the means to uncover content within the collection, and assess balance and coverage across the collection, as it involves checking catalogues, lists, direct checking of the collection on the shelf, and collection mapping (Johnson et al., Citation2005).

The literature presents a range of methodologies for assessing or surveying collections with a focus on distinct and varied subject areas including computer and information science collections (Wang & Huang, Citation2019), Indian rare books and manuscripts in digital collections (Bhat, Citation2017), music library surveys (Gottlieb, Citation1994), assessing diversity and inclusion in collections (Jorgenson & Burress, Citation2020), LGBTQ collections (Graziano, Citation2016; Proctor, Citation2020), and identifying government publications in collections (Zelmer, Citation2020). While these describe approaches to surveying collections for specific content, they do not provide any process for systematically surveying collections for Indigenous content. An extensive literature search revealed only two recent articles that describe how assessments and surveys of Indigenous cultural heritage collections were approached Canada and the USA.

In 2015 the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) published a call to action for cultural institutions to gather information about the legacy of Indian Residential Schools for all Canadians (2015). In response, University of Manitoba’s Neil John Maclean Health Sciences Library undertook an assessment of their Aboriginal Health Collection to identify the extent to which required subject areas were covered in the collection, how well it could support faculty seeking to improve the curriculum, and to identify gaps and inform future collection development priorities (Linton & Ducas, Citation2017). Rather than using a subject thesaurus to undertake the assessment, the Library’s preliminary review of subject areas was based on the TRC’s ninety-four calls to action, followed by a more detailed assessment framed around a checklist formed from the TRC’s seven health-related themes (Linton & Ducas, Citation2017, p. 269). In line with an Indigenous-informed, holistic world-view, the survey included materials relating to social and other determinants of health (Linton & Ducas, Citation2017, p. 269). This example provides useful guidance for how to incorporate non-subject thesaurus criteria into a collection assessment. Although the context is Canadian and the criteria specifically formed around the TRC’S calls to action, the approach is helpful in illustrating the use of a list checking qualitative analysis.

Reyes-Escudero and Cox (Citation2017) describe a survey of manuscripts in the University of Arizona Libraries Special Collections. The project focusses on the seventeen Indigenous peoples of Arizona, with ethnicity being used as the primary means of searching and collating counts of materials, accompanying notes and project proposals into a spreadsheet for each group, with the over-arching aim of producing collection guides (Reyes-Escudero & Cox, Citation2017, p. 132). As addressed in the literature review, the Library of Congress subject headings are prescritive and contain depricated and problematic historical terms; however, Reyes-Escudero and Cox note that their use is still critcal to supplement ethnicity search terms when indentifying content (2017, p. 132). While early efforts involved the review and documenting of individual manusricpts with a focus on culturally sensitive materials, this was soon recognized as untenable (Reyes-Escudero & Cox, Citation2017, p. 133) as the surveyors lacked the cultural expertise to identify secret and sacred content without the assitsance of Indigenous knowledge holders (2017, p. 134). Recognizing that the survey would be an ongoing, recursive process, decription was subsequently confined to the folder level, highlighting notable content, the volume of items, preservation challenges and the voices of tribal communities (Reyes-Escudero & Cox, Citation2017, p. 133). This article provides useful insights into the concurrent application of subject headings and lists in the analysis process, as well as flagging the need for a manageble project scope. It also highlights that for any cultural collections survey to result in meaninful outputs from a First Nations perspective, it is essential for Indigenous knowledge holders to be engaged in the process.

As discussed earlier in this review, the literature clearly points to the importance and adoption of cultural competence within the Australian University sector. This includes Australian academic libraries and the way in which they manage Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural heritage collections. The challenges for academic libraries managing Indigneous cultural heritage collections are complex, and are confounded by the a colonial past and a fundamental incompatibility between western methods of collection classification and description, and Indigenous epistemologies. Standards, resources and approaches exist for academic libraries to begin to address these issues, and these are beginning to be adopted by the sector. A starting point for any library to comprehensively implement these improvements is a survey of their Indigenous collections. The literature on techniques for assesing collections ranges from broad guidence, to approaches developed for specific subject areas. While the literature seach revealed only two articles in relation to survey techniques for Indigenous collections, none could be identified specifically for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander materials.

Given this literature gap, the University of Sydney Library identified a need to develop a methodology to survey its Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural heritage collections. This article proceeds to describe the methodology developed and the result of the pilot study to which it was applied.

Methodology

The research undertaken to establish and pilot a methodology to survey the University of Sydney Library’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural heritage collections falls broadly within the interpretivist epistemology, and it draws methodologically on Participative Action Research (PAR). The focus of the research is to better understand the content of the collection, and to establish more comprehensive, inclusive, accurate catalogue metadata. While the findings may be transferrable to others working in a similar context, they are not intended to be generalizable, and reliability should be assessed based on criteria such as credibility and authority, that are used to evaluate interpretivist, qualitative research (Bryman & Bell, Citation2015).

This research is characterized as PAR for several reasons. The primary aim of PAR is to use the research process to drive positive social change by examining the underlying causes of a problem, and addressing context-specific concerns for a community or organization by delivering changes to improve the situation (Baum et al., Citation2006; Schubotz, Citation2020). Traditionally PAR has involved working with disadvantaged or oppressed communities and their knowledge systems to inform the research process and develop a deeper understanding of problem being researched with the intention of delivering practical, local change (Greenwood & Levin, Citation2007; Ladkin, Citation2004). As a research practice it collaborative, inclusive and user-led, undertaken with, as opposed to on people, and its aims are emancipatory and transformational, seeking to improve the world from the perspective of all participants (Schubotz, Citation2020). In PAR, knowledge production is co-generative, resulting from an interaction between the researcher’s knowledge and local peoples’ knowledge, leading to dialogue that shifts perspectives for all involved (Greenwood & Levin, Citation2007). The concept of shifting societal power relations is crucial in PAR, and its inclusive nature extends the range of who participates in knowledge production and who determines what knowledge is useful (Baum et al., Citation2006; Gaventa & Cornwall, Citation2008). These characteristics align with University of Sydney Library’s cultural collections survey project which recognizes the need for research to be undertaken in collaboration with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander stakeholders to better understand the holdings, and has the dual aims of improving culturally safe collection management practices and enhancing the searchability of the collection for that community.

In PAR the research question is frequently derived from policy, practice or a real world problem that needs to be addressed (Lawson et al., Citation2015). The PAR process has been described as an “orientation to enquiry” (Reason & Bradbury, Citation2008, p. 2) rather than a methodology as the process is not predetermined but iterative, with methodological approaches emerging as participants’ understanding of issues develops. PAR is non-linear and recursive, with initial research questions leading to further questions through a “braided process of exploration, reflection and action” (McIntyre, Citation2007, p. 5). This is evident in the below described pilot survey process in which learning emerged following the trial of and reflection on initial approaches, with further steps being identified to progress the work in ways that would provide more meaningful results.

To develop and pilot its approach to surveying Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural collections the Library selected its Thesis Collection for two key reasons. Firstly, it is a proprietary collection of the University of Sydney bringing with this a greater sense of ownership and responsibility. Secondly, several items containing Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property had been discovered during digitization projects, which prompted the need for a more in-depth assessment. It was initially envisioned that the survey would focus on the entirety of the Thesis Collection. This was scaled down to surveying digital and digitized theses due to limited access to the collection during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Sydney eScholarship Repository is The University of Sydney’s institutional repository, providing global access to research outputs created by staff and students. Since 2012, all theses are submitted electronically via the repository. The repository also provides preservation and access to the University’s digital theses collection. Earlier theses are being progressively digitized and made available in the Repository.

The survey was conducted using a Qualitative, Collection-Based approach, more specifically Direct Collection Analysis (Johnson et al., Citation2005), focusing on the identifying items that fall into the categories detailed in the University of Sydney Library’s Cultural protocols (University of Sydney Library & Sentance, Citation2021). As mentioned in Reyes-Escudero and Cox (Citation2017), undertaking appraisals for culturally senstive content is difficult without the assistance of traditional knowledge holders. In addition, due to the lack of proper descriptive metadata, it was uncertain who to approach for advice. It was therefore decided that the survey should focus on identifying the communities that items relate to, along with flagging possible problematic items with the intention of seeking further information from the appropriate knowledge holders as needed. The intent of the survey was understand the extent of the cultural heritage content items contained, to identify opportunities for metadata to be enriched and improved to aid discoverability, and to flag offensive content or place cultural sensitivity restrictions in items’ catalogue records.

The survey was conducted by two full-time staff members with deep knowledge of the collection, as well as one student librarian. Only one staff member identified as Aboriginal whilst the other staff member and student librarian were non-Indigenous. Although it had originally been planned that a wider group of stakeholders would participate in the pilot survey process, including consultation with Aboriginal and Torres Strait knowledge holders, this was not feasible at the time given limitations in place during the COVID-19 Pandemic.

Before the survey was undertaken, the team met to review examples of content and develop a procedure to be used where they encountered items that should not be accessed for cultural sensitivity reasons. An initial list of items in the Digital Theses collection was created by conducting a search in the Repository Catalogue. The Library had conducted an earlier project in the general lending collection to identify records relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander topics and improve records using culturally appropriate subject headings, namely the AIATSIS Language codes and Subject Terms (Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies [AIATSIS], Citation2015). Based on experience drawn from this project and advice from the Library’s Metadata Team a search of the repository was conducted using the following syntax:

(All Fields: “Aborigin*”) OR (All Fields: "Indigenous") OR (All Fields: Torres Strait Islander")

Filter by type: Thesis, Masters Thesis, Honours

Items created before 1980 were selected for review as it was agreed that these items were more likely to contain outdated or offensive terminology, or that they may not have been published with the formal authorization of the relevant community. This decision was also based on advice from the Wingara Mura Resources Librarian who oversees the University’s Indigenous Reference Collection, other colleagues specializing in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Collections management, and existing guidance on assessing items for inclusion in school curriculums (Queensland Studies Authority, Citation2007). Items created after 1980 were also included in the overall survey to better understand the extent of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander items in the collection. However, they were not closely examined as it is planned that they will be covered in a future, more comprehensive survey of library’s Theses Collection.

Surveying items began with a general scan of the record metadata to confirm if the thesis contained Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander content. If the item was confirmed to contain information about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, a scan of the contents page was done to identify items containing content mentioned in the Cultural Protocols—for example, culturally sensitive information such as information on rites and ceremonies, images of people who have passed away, offensive, and outdated terminology. If the item was found to contain such content the staff noted down where this was in the spreadsheet, along with example quotes from the item or page references to the content in question. The survey team also collected information on:

Items that contain Indigenous or Cultural Intellectual Property

Whether there were cultural restrictions recorded on the item

If the item contains information that is offensive, outdated or presents a racially biased perspective

Whether there are known, related items in the collection (or at other institutions)

The name of the community identified within the content and topics covered (e.g. Dharug, Gadigal, Wiradjuri) and;

Whether there was any existing community decision or advice regarding management and care of the item.

This information was recorded in a spreadsheet under the following column headings, and was then reviewed by the leader of the survey team:

Refer to Steering Group; collection name/library location; hyperlink, creator; title; year; publisher; subjects/keywords; description/abstract; does the item contain Indigenous cultural intellectual property; cultural restrictions; offensive/traumatic content; significance; related items; community/coverage; community relationship; conservation notes; further information; notes.

For items where there was an explicit statement regarding culturally sensitive content, this was noted in the spreadsheet and brought to the attention of the Metadata Team and the Digital Collections Team to update the metadata, add a cultural care notice, or restrict access to the item.

Findings

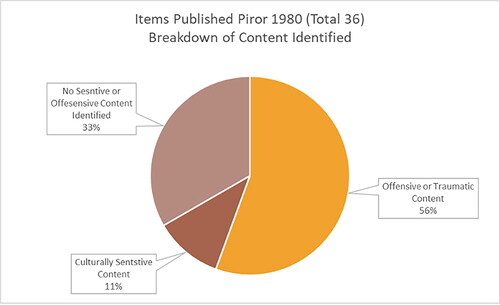

The survey identified a total of 1901 digitized or born digital theses covering Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander content, among which 36 created prior to 1980 were closely examined as part of the pilot survey.

These 36 items were reviewed and detailed using the spreadsheet described in the methodology section. An extract of the spreadsheet data is included in to illustrate some of the key information that was captured for each item.

Out of the 36 items reviewed in detail, 20 (56%) were found to contain some form of offensive or traumatic content. The most common occurrence was the use of outdated terminology to describe Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples or cultural practices, or offensive commentary by the author. For these items, a cultural care notice or metadata was added to the item to advise users before accessing the item. The cultural care notices provide standardized wording to communicate that the item contains images or voices of people who have died, offensive terminology or wording, and to acknowledge Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property. These notices, developed in consultation with the University of Sydney Office of the Deputy Vice Chancellor Indigenous Strategy and Services, are included as an additional digital page near the beginning of the item. This embedded notice travels with the item if it is downloaded and shared, or a user does not have access to the online record.

Four items were identified as potentially containing secret, sacred, or restricted content. One item had a notice in the record to indicate its inclusion of restricted content. None of the four items identified were publicly available at the time of the survey, either having had restricted access applied or being stored on the Library’s file store prior to the survey. These items were flagged so that the Library could seek advice from the relevant communities or experts, to ascertain whether access to the content should indeed be restricted, and how to appropriately care for the items moving forward. Access to these items continues to be restricted while further research is carried out ().

As theses had not been included in the earlier project to add AIATSIS Language codes to the general lending collection, the survey team also noted that all items in the Thesis Collection could benefit from the inclusion of AustLang codes to identify relevant Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander language groups (AIATSIS, Citation2008). Where an item explicitly stated that it contained information from a particular Aboriginal Country or People, the AustLang code could be included to enhance discoverability. A note was made for those items where the survey team could identify content relating to a particular Country or People. This information was then passed on to the Library’s Metadata Team so that they could add the relevant AustLang code to the catalogue and on the repository record.

Items relating to Papua New Guinea were also discovered during the survey. Whilst these were out of scope for the pilot, it was agreed that it would be beneficial to highlight these items so future work could be undertaken to enhance their discoverability by communities or researchers. It was also recognized that false positives were surfaced during the initial search due to the use of the term “Indigenous” (such as a plant being indigenous to a particular area). This showed methodological shortcomings resulting from the use of broad search terms, and was flagged as an area for improvement in future surveys.

During the pilot debrief, feedback from staff who participated in the survey showed that some categories in the list were too broad or open to interpretation. For instance, identifying the use of outdated or offensive terminology can be subjective. A key learning from this was that more training was required on what terminology should be considered offensive or outdated. Checklists or other tools that explicitly state terms, phrases or content would also assist with future survey work.

Another key concern was the appropriateness of non-Indigenous staff reviewing items for Indigenous cultural and intellectual content, even after training or briefing. Although the intention of the survey was primarily to flag items for review, at times the staff did not feel confident undertaking this kind of work. Since the survey was undertaken, most University of Sydney Library staff working with the collection have attended a workshop, facilitated by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Librarians, about how to identify, and work with items that may contain culturally sensitive material. It is also recognized that cultural collections survey projects should ideally be done in consultation with traditional knowledge holders or subject matter experts.

Like other collection surveys of this nature, it is acknowledged that this work is highly resource intensive. It was originally envisioned that it would take three weeks to complete the pilot survey however, when factoring in the review of flagged items it took over a month. Another factor that extended the project was the capacity of staff who were involved in the project, who were fulfilling other duties in addition to the survey.

For future surveys, it is recommended that the project manager allow additional time for the initial survey work and allocate at least one full time staff member to the project to focus on the review of content. Equally important is the need to include traditional knowledge holders on the team, especially where curatorial decisions need to be made regarding cultural content. Where is it not practical to do so during the survey, this could alternately be planned as a next step after identifying community relationships. Future surveys of the Library’s cultural collections are planned to be done with guidance from the Library’s newly formed Cultural Collections Reference Group. This group was formed as a recommendation from the Library’s Cultural Protocols and includes library, University and Indigenous stakeholders.

Discussion

In today’s globalized world, libraries are expected to cater to a diverse audience with varying cultural backgrounds. In academic libraries this is further complicated by the need to include and preserve historical and varied perspectives, including primary source materials. To meet this challenge, libraries will by their nature have a need to include in their collections culturally sensitive materials. Cultural sensitivity is about recognizing and respecting the cultural differences and diversity of library users. This means selecting materials that reflect a range of cultures, traditions, and perspectives, and actively managing materials that could be considered culturally insensitive or offensive.

Libraries can use a variety of tools and resources to assist in this process, such as the pilot survey conducted by The University of Sydney Library. Ideally the surveying process should involve a systematic review of the library’s collection to identify any potentially offensive materials or gaps in representation. Initially undertaking this work as a series of smaller projects allows learnings and resource scoping for larger surveys and associated collection remediation activities. Critically, undertaking the work in a considered, consultative way also means the project can be a space for learning and embedding an understanding of cultural protocols in the organizational culture. At the University of Sydney Library there was a greater sense of responsibility for theses given the collection is published by our institution. Focusing the pilot survey on theses also provided insight into what information or guidance should be provided to authors/students for future these development and submission.

It is important to note that surveying culturally sensitive materials is an ongoing process. Libraries must regularly review their collections to ensure that they remain relevant and inclusive of all cultures and perspectives. Moreover, it is not enough to simply add more diverse materials to the collection. Libraries must also promote and make these materials accessible to users, for example through digitization programs, to ensure that they are being utilized. Increasing digital format holdings leading to greater discoverability equally creates even more responsibility for libraries to understand our collections and support their use with appropriate and respectful context. Along with proactive approaches such as the collection survey, consideration should be given to enabling better mechanisms for responsive approaches, such as creating more online feedback or “right of reply” pathways for individuals and communities.

Another aspect to consider when surveying culturally sensitive materials is the potential for censorship. Libraries must balance the need to provide access to a wide range of materials with the need to avoid causing offense or harm to any group. This requires a thoughtful approach that accounts for the library’s values and mission, as well as the needs and preferences of the community it serves. By doing so, libraries can ensure that they are providing equitable access to information and promoting cultural understanding and empathy.

The process of surveying culturally sensitive materials should include a critical examination of the language used in library collections. This means analyzing not only the terminology used but also the underlying assumptions and biases inherent in the language.

In conclusion, a pilot collection survey is a valuable and effective method for libraries to start to understand and respond to culturally sensitive material in their collections. Libraries must engage in ongoing and active consultation with diverse communities to ensure that their collections are respectful and inclusive of all cultures and perspectives. This requires a critical examination of the language used in library collections and a willingness to adapt practices as language and cultural norms evolve.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Library Information and Resource Network Inc. (ATSILIRN). (2012). ATSILIRN Protocols for libraries, archives and information services. https://atsilirn.aiatsis.gov.au/protocols.php

- Alizadeh, S., & Chavan, M. (2016). Cultural competence dimensions and outcomes: A systematic review of the literature. Health & Social Care in the Community, 24(6), e117–e130. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12293

- Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS). (2008). AustLang. https://collection.aiatsis.gov.au/austlang/about

- Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS). (2015). Pathways thesauri. https://aiatsis.gov.au/publication/35114

- Australian Library and Information Association (ALIA). (2019). Improving library services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. https://read.alia.org.au/improving-library-services-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-peoples

- Baum, F., MacDougall, C., & Smith, D. (2006). Participatory action research. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 60(10), 854–857. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2004.028662

- Bhat, M. (2017). Development of digital libraries in India: A survey of digital collection of National Digital Library of India. International Research: Journal of Library and Information Science, 72(2), 219–230.

- Bryman, A., & Bell, E. (2015). Business research methods (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Christie, M. (2007). Maths as an Aboriginal community practice. Charles Darwin University. https://www.cdu.edu.au/centres/macp/index.html

- Circle, F. A. (2007). Protocols for Native American archival materials (PNAAM). http://www2.nau.edu/libnap-p/PrintProtocols.pdf

- Commonwealth of Australia (CoA). (2015). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural capability: A framework for Commonwealth agencies. Australian Public Service Commission. https://www.apsc.gov.au/sites/default/files/2022-11/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-cultural-capability-framework.pdf

- Deakin University. (n.d). Cultural diversity and inclusion plan 2018–2020. https://www.deakin.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/1902357/cultural_diversity_inclusion_plan-2018-2020.pdf

- Duarte, M., & Belarde-Lewis, M. (2015). Imagining: Creating spaces for Indigenous ontologies. Cataloging & Classification Quarterly, 53(5–6), 677–702. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639374.2015.1018396

- Frawley, J., Russell, G., & Sherwood, J. (2020). Cultural competence and the higher education sector: A journey in the academy. In J. Frawley, G. Russell, & J. Sherwood (Eds.), Cultural competence and the higher education sector: Australian perspectives, policies and practice (pp. 3–11). Springer.

- Gaventa, J., & Cornwall, A. (2008). Power and knowledge. In P. Reason & H. Bradbury (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of action research (pp. 172–189). SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Gottlieb, J. (1994). Collection assessment in music libraries. Music Library Association.

- Graziano, V. (2016). LGBTQ collection assessment: Library ownership of resources cited by master’s students. College & Research Libraries, 77(1), 114–127. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.77.1.114

- Greenwood, D. J., & Levin, M. (2007). Introduction to action research. SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Holt, K., & Seki, K. (2012). Global leadership: A developmental shift for everyone. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 5(2), 196–215. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1754-9434.2012.01431.x

- Howard, S., & Knowlton, S. (2018). Browsing through bias: The Library of Congress classification and subject seadings for African American studies and LGBTQIA studies. Library Trends, 67(1), 74–88. https://doi.org/10.1353/lib.2018.0026

- James Cook University. (n.d). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander research ethics. https://www.jcu.edu.au/jcu-connect/ethics-and-integrity/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-research-ethics

- Janke, T. (2022). True tracks: Respecting Indigenous knowledge and culture. NewSouth Publishing.

- Johnson, J. P., Lenartowicz, T., & Apud, S. (2006). Cross-cultural competence in international business: Toward a definition and a model. Journal of International Business Studies, 37(4), 525–543. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400205

- Johnson, P., Hille, J., & Reed, J. A. (2005). Fundamentals of collection development and management. ALA Publications.

- Jorgenson, S., & Burress, R. (2020). Analyzing the diversity of a highschool library collection. Knowledge Quest, 48(5), 48–53.

- Kearney, J., Janke, T. (2018). Rights to culture: Indigenous cultural and intellectual property (ICIP), copyright and protocols. Terri Janke and Company Lawyers and Publishers. https://www.terrijanke.com.au/post/2018/01/29/rights-to-culture-indigenous-cultural-and-intellectual-property-icip-copyright-and-protoc

- Ladkin, D. (2004). Action Research. In C. Seale, G. Gobo, J. F. Gubrium, & D. Silverman (Eds.), Qualitative research practice. SAGE Publications.

- Lawson, H. A., Caringi, J., Pyles, L., Jurkowski, J., & Bozlak, C. (2015). Participatory action research. Oxford University Press, Incorporated.

- Lee, D. (2008). Indigenous knowledges and the university library. Canadian Journal of Native Education, 31(1), 149–161.

- Leung, K., Ang, S., & Tan, M. L. (2014). Intercultural competence. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 489–519. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091229

- Linder, C., & Cooper, D. (2016). From cultural competence to critical consciousness: Creating inclusive campus environments. In M. J. Cuyjet, M. F. Howard-Hamilton, D. L. Cooper, & C. Linder (Eds.), Multiculturalism on campus: Theory, models, and practices for understanding diversity and creating inclusion. Stylus Publishing, LLC.

- Linton, J., & Ducas, A. (2017). A new tool for collection assessment: One library’s response to the calls to action issued by Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Collection Management, 42(3-4), 256–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/01462679.2017.1344596

- Martin, K., & Mirraboopa, B. (2003). Ways of knowing, being and doing: A theoretical framework and methods for indigenous and indigenist re-search. Journal of Australian Studies, 27(76), 203–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/14443050309387838

- Masterson, M., Stableford, C., & Tait, A. (2019). Re-imagining classification systems in remote libraries. Journal of the Australian Library and Information Association, 68(3), 278–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/24750158.2019.1653611

- McIntyre, A. (2007). Participatory action research. SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483385679

- McKay, B. (2018). Intercultural competence a hallmark of Monash education. Monash University. https://www.monash.edu/arts/monash-intercultural-lab/news-and-events/articles/intercultural-competence-a-hallmark-of-monash-education

- Miniter, A., & Vo-Tran, H. (2021). Modular information management: Using AUSTLANG to enhance the classification of Australian Indigenous knowledge resources. Journal of the Australian Library and Information Association, 70(4), 352–374. https://doi.org/10.1080/24750158.2021.1958447

- Moorcroft, H. (1992). Ethnocentrism in subject headings. The Australian Library Journal, 41(1), 40–45.

- Nakata, M. (2007). The cultural interface. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 36(S1), 7–14. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1326011100004646

- Nakata, M., Byrne, A., Nakata, V., & Gardiner, G. (2006). Indigenous knowledge, the library and information service sector, and protocols. In M. Nakata & M. Langton (Eds.), Australian Indigenous knowledge and libraries (pp. 7–20). UTS ePress. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048623.2005.10721244

- Nakata, M., & Langton, M. (Eds.). (2006). Australian Indigenous knowledge and libraries. UTS ePress.

- National and State Libraries Australia (NSLA). (n.d). Cultutally safe libraries program: ATSILIRN protocol 5: Description and classification. https://www.nsla.org.au/resources/cslp-collections/protocol5

- National Centre for Cultural Competence. (n.d). About us. University of Sydney. https://www.sydney.edu.au/nccc/about-us.html

- Nyitray, K., & Reijerkerk, D. (2021). Searching for Paumanok: A study of Library of Congress authorities and classifications for Indigenous Long Island, New York. Cataloging & Classification Quarterly, 59(5), 409–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639374.2021.1929627

- Olson, H. (1998). Mapping beyond Dewey’s boundaries: Constructing classificatory space for marginalized knowledge domains. Library Trends, 47(2), 233–254.

- Pecci, A., Frawley, J., & Nguyen, T. (2020). On the critical, morally driven, self-reflective agents of change and transformation: A literature review on culturally competent leadership in higher education. In J. Frawley, G. Russell, & J. Sherwood (Eds.), Cultural Competence and the higher education sector: Australian perspectives, policies and practice (pp. 59–81). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-5362-2_5

- Proctor, J. (2020). Representation in the collection: Assessing coverage of LGBTQ content in an academic library collection. Collection Management, 45(3), 223–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/01462679.2019.1708835

- Puckett, T. (2020). The importance of developing cultural competence. In N. S. Lind & P. T. (Eds.), Cultural competence in higher education. Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S2055-364120200000028004

- Queensland Studies Authority. (2007). Selecting and evaluating resources. Queensland Studies Authority. https://www.qcaa.qld.edu.au/downloads/approach2/indigenous_g008_0712.pdf

- Reason, P., & Bradbury, H. (2008). Introduction. In P. Reason & H. Bradbury (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of action research (pp. 1–10). SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Reijerkerk, D., & Nyitray, K. (2023). (Re)moving Indigenous knowledge boundaries: A review of library and archival collection literature since the enactment of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA). Collection Management, 48(1), 22–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/01462679.2022.2033144

- Reyes-Escudero, V., & Cox, J. W. (2017). Survey, understanding, and ethical stewardship of Indigenous collections: A case study. Collection Management, 42(3-4), 130–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/01462679.2017.1336503

- Roy, L. (2015). Indigneous cultural heritage preservation: A review essay with ideas for the future. International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions, 41(3), 192–203. https://doi.org/10.1177/0340035215597236

- Schubotz, D. (2020). Participatory action research (P. Atkinson, S. Delamont, A. Cernat, J. W. Sakshaug, & R. A. Williams, Eds.). SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Shen, Z. (2015). Cultural competence models and cultural competence assessment instruments in nursing: A literature review. Journal of Transcultural Nursing: Official Journal of the Transcultural Nursing Society, 26(3), 308–321. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659614524790

- Simpson, L. (2004). Anticolonial strategies for the recovery and maintenance of Indigenous knowledge. The American Indian Quarterly, 28(3), 373–384. https://doi.org/10.1353/aiq.2004.0107

- Thorpe, K., & Galassi, M. (2014). Rediscovering Indigenous languages: The role and impact of libraries and archives in cultural revitalisation. Australian Academic & Research Libraries, 45(2), 81–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048623.2014.910858

- Thorpe, K., & Galassi, M. (2018). Diversity, inclusion & respect: Embedding Indigenous priorities in public library services. Public Library Quarterly, 37(2), 180–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/01616846.2018.1460568

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to action. https://ehprnh2mwo3.exactdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf

- United Nations. (2007). United Nations declaration on the rights of Indigenous peoples. https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N06/512/07/PDF/N0651207.pdf?OpenElement

- Universities Australia. (2011). National best practice framework for Indigenous cultural competency in Australian universities. Universities Australia.

- University of Adelaide. (2023). Collection cultural rights management. https://libguides.adelaide.edu.au/c.php?g=924195&p=6733106

- University of Newcastle. (2020). Cultural capability framework: 2020–2025. https://www.newcastle.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/710874/2020-1112-Cultural-Capability-Framework_v14-final-online.pdf

- University of Queensland. (n.d.-a). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural learning plan 2021–2022. https://www.uq.edu.au/about/files/10600/Aboriginal%20and%20Torres%20Strait%20Islander%20Cultural%20Learning%20Plan.pdf

- University of Queensland. (n.d.-b). Culturally sensitive collections. https://web.library.uq.edu.au/collections/culturally-sensitive-collections

- University of Sydney. (n.d). National Centre for Cultural Competence. https://www.sydney.edu.au/nccc/

- University of Sydney Library, & Sentance. (2021). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural protocols. University of Sydney. https://hdl.handle.net/2123/24602

- University of Technology. (2022). ATSIDA. https://www.lib.uts.edu.au/resources/atsida

- Vézina, B. (2016). Cultural institutions and the documentation of Indigenous cultural heritage: Intellectual property issues. In C. Callison, L. Roy, & G. LeChaminant (Eds.), Indigenous notions of ownership and libraries, archives and museums. Walter de Gruyter GmbH.

- Wang, X., & Huang, J. (2019). Department-specific collection assessment. Collection and Curation, 39(1), 22–30. https://doi.org/10.1108/CC-02-2019-0005

- World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO). (2005). Archives and museums: Balancing protection and preservation of cultural heritage. Retrieved 2005 from https://www.wipo.int/wipo_magazine/en/2005/05/article_0010.html

- Zelmer, L. (2020). Using OCLC WorldCat to survey government publications in a library’s collection. DttP: Documents to the People, 48(1), 10–12. https://doi.org/10.5860/dttp.v48i1.7335