ABSTRACT

This study delves into the transformative impact of a professional development model (PDM) across three affiliated private schools in Beirut, Lebanon, spanning three years, with a primary focus on nurturing teacher leadership. At the heart of this PDM, teachers assumed the role of trainers, guiding their colleagues during dedicated professional development days. Employing a grounded theory approach, the study conducted semi-structured interviews with 12 teacher trainers and engaged with three school principals. The research reveals five central categories. Two categories revolve around the evidence highlighting the progression of teacher leadership: (1) accessing and utilising research to enhance teaching and student learning, and (2) promoting professional learning for continuous improvement. Additionally, three categories elucidate the elements instrumental in facilitating the PDM's role in cultivating teacher leadership: reciprocal empowerment, conceptual awareness, and collaborative metacognition. This model redefines traditional top-down leadership structures, allowing teachers to actively mold their professional development journey, creating a more collaborative and intentional approach to teacher leadership.

Introduction

The existing body of research indicates that effecting alterations in teaching methods and student performance necessitates a type of professional growth that is collaborative, cohesive, rooted in subject matter, concentrated on teaching techniques, and extended in duration (Poekert Citation2016). The cultivation of educators to assume leadership roles represents an example of such a professional growth approach (Ghamrawi Citation2013a, Citation2013b; Poekert Citation2016). Nonetheless, the progression of teacher leadership as a mode of immersive professional advancement and school reform is progressively gaining traction, presenting potential for augmenting the calibre of teacher education (Admiraal et al. Citation2021; Al-Jammal and Ghamrawi Citation2013; Campbell et al. Citation2022).

Teacher leadership, a concept situated at the intersection of pedagogical expertise and influential leadership, holds a pivotal position within educational discourse (Ghamrawi Citation2010, Citation2011, Citation2023; Nguyen, Harris, and Ng Citation2020; Pan, Wiens, and Moyal Citation2023; Wenner and Campbell Citation2017). It represents a paradigm shift from the conventional perception of teaching as a solitary endeavour to one that acknowledges teachers as change agents operating within collaborative contexts (Campbell et al. Citation2022; Harris and Jones Citation2021). The importance of teacher leadership emanates from its potential to foster a culture of continuous improvement (Shen Citation2023), enabling educators to drive meaningful transformations in curriculum (Harris, Jones, and Crick Citation2020), instructional methods (Ghamrawi et al. Citation2023a), tech pioneers (Ghamrawi and Tamim Citation2023) and student engagement (Nguyen, Harris, and Ng Citation2020). Yet, as the concept gains traction, its precise dimensions and the avenues through which it can be effectively developed remain somewhat enigmatic (Nguyen, Harris, and Ng Citation2020). The pathways that lead to the cultivation of teacher leaders and the mechanisms that underpin their capacity to inspire positive change are areas that necessitate further exploration and elucidation (Bond Citation2022). With a scarcity of evidence-based explorations concerning professional development conducive to fostering teacher leadership, this study becomes instrumental in unveiling and addressing this crucial aspect.

Focusing on the evolution of teacher leadership skills within a transformational Professional Development Model (PDM) and the specific elements of the PDM that facilitate teachers’ utilisation of these skills, this study was guided by the following research questions:

What evidence exists regarding the development of teacher leadership skills among participants engaged in a transformative professional development model over a three-year period?

What are the elements of a transformative professional development model that contribute to the enactment and cultivation of teacher leadership skills among participants?

Theoretical background

Teacher leadership

Teacher leadership denotes educators’ capacity to assume leadership responsibilities beyond their traditional classroom roles, thus positively impacting student learning, instructional strategies, and school enhancement endeavours (Ghamrawi Citation2023; Ghamrawi et al. Citation2023a, Citation2023b; York-Barr and Duke Citation2004; Katzenmeyer and Moller Citation2009). It entails teachers proactively taking the lead, collaborating with peers, and actively contributing to decision-making processes that shape educational practices (Harris and Jones Citation2019).

The spectrum of teacher leadership encompasses diverse forms and activities, spanning from mentoring and coaching fellow teachers to designing and implementing professional development initiatives, participating in curriculum design and assessment procedures, advocating for educational policies, and engaging in research and innovation endeavours (Bond Citation2022; Chen Citation2020; Lumpkin Citation2016). Through the lens of teacher leadership, educators assume a pivotal role in shaping educational dynamics, fostering professional development, and ameliorating student outcomes (Ghamrawi Citation2013a). This empowers teachers to channel their expertise, knowledge, and experiences beyond the confines of their classrooms, creating a more far-reaching impact across schools, districts, and the broader educational landscape (Shen et al. Citation2020).

Certain studies have confined teacher leadership to formal roles often occupied by only a select few educators (Cooper Citation2023). However, a multitude of research suggests that teacher leadership transcends the classroom walls, enabling educators to influence the greater school community at multiple tiers (Warren Citation2021; Youngs and Evans Citation2021). This paper advances the notion that teacher leadership is a function rather than a fixed position, embracing the idea that it is not necessarily tied to official titles, positions, or hierarchical authority.

Teacher leadership and school improvement

As posited by Suleiman and Moore (Citation1997), a persistent misconception prevails in schools, asserting that teaching is exclusively reserved for teachers, while leadership is designated for administrators. Supporting this viewpoint, Crowther et al. (Citation2002) argue that centralising school leaders in the leadership process has yielded detrimental effects on educational outcomes. The contemporary emphasis on the importance of integrating teachers into leadership roles for school improvement is rooted in the works of Killion (Citation1996), Whitaker (Citation1995), and Lieberman and Miller (Citation1999). Killion (Citation1996) suggests that enduring school improvement initiatives may not materialise without teacher involvement in leadership; Whitaker (Citation1995) underscores the necessity of teacher leadership for the success of initiatives; and Lieberman and Miller (Citation1999) contend that school reform endeavours are destined to fail without active participation from teachers in leadership.

Shen et al. (Citation2020) enriched the discourse on teacher leadership by crafting a comprehensive framework that outlines various dimensions within this conceptual domain, drawing insights from a decade's worth of pertinent literature and reports. The seven fundamental dimensions include nurturing a shared vision, overseeing activities beyond the classroom, facilitating improvements in curriculum and instruction, fostering professional development, engaging in policy formulation, enhancing outreach and collaboration, and cultivating a collaborative culture within the school. One could posit that these findings, rooted in the literature, lend support to the idea that teacher leadership contributes to school improvement initiatives, either directly or indirectly.

Currently, teacher leadership is regarded as a pivotal instrument for school improvement, as it entails empowering educators to assume leadership roles within educational institutions, enabling them to harness their expertise. This approach is closely linked to school improvement and has a direct impact on enhancing students’ learning outcomes (Ghamrawi Citation2023; Ghamrawi and Abu-Tineh Citation2023; Harris and Jones Citation2019). Teacher leaders function as catalysts for positive transformation (Ghamrawi Citation2010, Citation2013b, Citation2023), taking the lead in improvement initiatives (Harris and Jones Citation2019), and fostering a culture of continuous learning (Youngs and Evans Citation2021).

The literature highlights a compelling argument that teacher leadership, characterised by principled action, holds unprecedented significance in shaping meaning for children, youth, and adults alike (Conway and Andrews Citation2023). The imperative to reinvigorate the organic essence of teacher leadership has become more pressing than ever, necessitating a renewed commitment to recognising and fostering the importance of advocating for and providing agency to teachers who extend their leadership beyond the confines of the classroom(Conway and Andrews Citation2023).

Highlighting uncertainties

The sphere of teacher leadership development is confronted with an array of uncertainties, as delineated by extant educational research. A fundamental challenge emerges from the manifold interpretations and roles ascribed to teacher leadership, resulting in a notable lack of consensus on a standardised definitional framework (Cosenza Citation2015). The intricacies surrounding the measurement of effectiveness and impact constitute a complex terrain, with persistent debates concerning appropriate metrics and the enduring influence of such programmes on student outcomes (Schott, van Roekel, and Tummers Citation2020).

Moreover, the impediments to successful programme implementation, encompassing factors such as resistance, resource limitations, and institutional constraints, further compound the prevailing challenges (Çoban, Özdemir, and Bellibaş Citation2023). Ensuring the sustained efficacy and impact of teacher leadership initiatives over an extended temporal trajectory gives rise to apprehensions regarding their enduring viability (Polatcan, Arslan, and Balci Citation2023). The role of contextual determinants, including school culture and leadership support, introduces a layer of complexity in discerning the operative dynamics of these initiatives across diverse settings (Poekert Citation2016).

Ongoing uncertainties include the identification of optimal professional development models (Fairman et al. Citation2023), the exploration of policy implications (Trinter and Hughes Citation2023), and the nuanced consideration of issues pertaining to inclusivity and diversity (Beck et al. Citation2023).

With a scarcity of evidence-based inquiries into professional development conducive to fostering teacher leadership, this study assumes a pivotal role in unveiling and addressing this crucial aspect. The investigation delves into a specific professional development model that serves as a fertile ground for nurturing and harnessing teacher leadership potential.

Teacher professional development

The landscape of teacher professional development (TPD) literature is characterised by a rich tapestry of perspectives. A recurring theme in this body of work highlights effective TPD through its ability to (a) ignite teacher motivation (Jackson, Mawson, and Bodnar Citation2022; Mockler Citation2022; Tran et al. Citation2022), (b) constructively enhance teachers’ knowledge (Bae, Hand, and Fulmer Citation2022; Gaumer Erickson et al. Citation2017), (c) foster teacher collaboration (Bates and Morgan Citation2018; Farrow, Schneider Kavanagh, and Samudra Citation2022), and (d) integrate practice (Althauser Citation2015; Mockler Citation2022). Aligning high-quality TPD with the principles of andragogy, it is asserted that basing TPD on this adult learning theory underpins its efficacy (Powell and Bodur Citation2019; Witcher and Sasso Citation2022). Significantly, the incorporation of andragogy into TPD encapsulates many of these aforementioned aspects.

Andragogy, or Knowles (Citation1973) theory of adult learning, posits that adult learners, including teachers, experience optimal learning when it's self-directed. Knowles argues that ‘as an individual matures, his need and capacity to be self-directed, to utilize his experience in learning, to identify his own readiness to learn, and to organize his learning around life problems, increases steadily’ (Knowles Citation1973, 43). For adult learners, including teachers, the first step involves grasping the rationale behind learning something before embarking on the learning journey (Knowles, Holton, and Swanson Citation2005, 64). Adult learners need clarity on how learning will unfold, the content to be covered, the purpose of learning, and assurance that they have the autonomy for self-direction (Hare Citation2012). Consequently, teachers, as adult learners, are intrinsically motivated to learn, leveraging heightened levels of autonomy. Therefore, professional development opportunities resonate more with teachers, given the latitude to decide how, what, where, when, and why they engage with new content.

On the contrary, the literature underscores effective TPD as a means of nurturing teachers’ knowledge rather than merely delivering information. In essence, the approach should be constructivist, building upon teachers’ existing knowledge while expanding and enriching it (Bae, Hand, and Fulmer Citation2022; Gaumer Erickson et al. Citation2017), without precipitating cognitive overload (McGill Citation2021). In alignment with the cognitive load theory, learning is optimised when the load on working memory is well-structured, allowing changes in long-term memory and subsequent retention (Thompson and McGill Citation2008). Teacher training should facilitate the acquisition of fresh knowledge while effectively bridging it with teachers’ prior understanding, without overwhelming them in terms of volume.

Moreover, effective TPD champions and nurtures teacher collaboration (Bates and Morgan Citation2018; Ghamrawi Citation2013a). This entails creating an environment where teachers can share ideas, collaboratively solve problems, collectively deliberate, and work in tandem. Professional learning communities (PLCs) exemplify the ideal setting for teacher collaboration (Gore and Rosser Citation2022). PLCs augment teachers’ professional competencies to enhance student learning, providing dedicated time for collaborative endeavours (Valckx, Vanderlinde, and Devos Citation2020). These communities share six common components: (1) collective values and vision; (2) shared responsibility; (3) collective decision-making; (4) mutual practice sharing; (5) supportive conditions; and (6) critical collaboration centred on peer feedback and reflection.

Numerous research-based concrete examples supporting the cultivation of teacher leadership within PLCs are highlighted in the literature. For instance, Moller (Citation2006) concludes that teacher leadership naturally emerges as an inevitable outcome of participation in PLCs. Similarly, Brodie (Citation2021) suggests that PLCs have the potential to facilitate the development of teacher leadership by nurturing teacher agency. However, the journey towards teacher leadership development is not without challenges in such environments. Oppi and Eisenschmidt (Citation2022) emphasise that the lack of support and interest from the school leadership team could significantly impede the sustainability of the PLC, thereby affecting the trajectory of teacher leadership development.

Nevertheless, the literature strongly advocates for the integration of practice as a crucial facet of effective TPD (Althauser Citation2015; Mockler Citation2022). Andragogy further supports the assimilation of experience, endorsing ‘experiential learning’ or learning by doing. This method involves sharing an experience, reflecting on it, abstracting insights, and then applying these lessons in novel contexts (Knowles, Holton, and Swanson Citation2005). Teachers require the opportunity to experiment with new ideas beyond the facilitators’ scope, applying constructed knowledge in new situations and contexts (Althauser Citation2015; Mockler Citation2022). Ideally, teachers should trial these new ideas within their own classrooms, collaboratively with peers (Ghamrawi Citation2022; Kyza et al. Citation2022).

Teacher leadership and professional development

Frick and Browne-Ferrigno (Citation2016) underscore that the journey towards developing teacher leaders demands a blend of formal and informal professional development, characterised by its continuity. This developmental trajectory requires educators to engage in job-embedded learning experiences, often within communities of practice. The concept of a community of practice, where individuals collaboratively nurture expertise concerning shared practices, emerges as a pivotal avenue for fostering emerging teacher leaders’ career progression and professional growth (Frick and Browne-Ferrigno Citation2016).

Moreover, research conducted by Huggins, Lesseig, and Rhodes (Citation2017) offers insight into the transformative potential of iterative communities of practice. Their study revealed that educators who were granted the opportunity to engage in communities of practice, involving both professional development contexts and school-based Professional Learning Communities (PLCs), demonstrated heightened receptiveness to assume leadership responsibilities linked to peer coaching. This underscores the reciprocal relationship between the engagement in communities of practice and the enactment of teacher leadership.

In this context, Osmond-Johnson (Citation2017) emphasises professional development models that embrace teacher-led initiatives. She describes the empowering impact of delegating the role of facilitators to teachers, thereby enhancing their potential to embrace teacher leadership. Teacher-driven agendas and initiatives, offer an optimal alternative to the conventional one-size-fits-all approach (Ghamrawi Citation2013a, Citation2022).

Context of the study

Three sister schools located in Beirut, Lebanon, introduced a transformative professional development model (PDM) with the explicit goal of fostering enduring and constructive transformations in teachers’ professional identities, thereby cultivating them as teacher leaders and consequently enhancing their impact on both student learning and the overall progress of the schools. In line with this objective, they established a series of events termed Professional Days (PDs), structured as teacher-led training sessions organised by school staff for their fellow teachers. This approach aimed to cultivate a culture of collaborative learning, encouraging the dissemination of knowledge and the nurturing of leadership skills among teachers.

A Professional Development (PD) day comprises a multitude of in-house teacher-led workshops. It is structured around proposals submitted by teachers, who show interest in delivering workshop for their fellows. Beforehand, teacher trainees register in the workshops aligned with their individual needs. They create their personal agenda comprised of workshops they choose for themselves based on a programme often sent to them a week before the event. This programme includes titles of workshops, name of presenters, alongside the synopsis for each one of them.

Teachers frequently participate in workshops organised by colleagues from different departments, allowing them to engage with individuals they might not typically interact with. Three PDs were conducted during each academic year. These sessions take place on regular school days, and parents are informed in advance not to send their children to school on those days, as the teachers will be engaged in professional development activities. This dedicated time provides an opportunity for teachers to share ideas in a relaxed and unhurried manner.

Teachers who are interested in leading workshops for their fellow colleagues submit proposals to the school's professional development officer. These proposals then undergo a rigorous double-blind review process by the PD organising committee. The committee is composed of school principals and a selected group of subject leaders from all three schools. These subject leaders are chosen due to their extensive experience in leading workshops. Evaluations are carried out using predefined criteria that are communicated to all school members prior to each PD session. After the review of proposals, teachers are provided with feedback to further refine their workshop ideas. Throughout the preparation phase, starting from the creation of proposals to the execution of workshops during the PD sessions, situational assistance is available to any teacher from the PD organising committee.

At the conclusion of each academic year, schools extended invitations to teacher trainers to engage in a self-assessment process, prompting them to reflect upon their progression as teacher leaders. This self-assessment toolFootnote1 drew its inspiration and framework from the collaborative efforts of the Centre for Great Teachers and the American Institute for Research. The tool has been structured into four distinct domains: collaboration and communication, professional learning and growth, instructional leadership, and school and community advocacy. Within each of these domains, teachers have the opportunity to delve into both fundamental and advanced competencies, aligning their exploration with their existing level of experience within leadership roles.

Across the three years, teachers created portfolios with the aim of documenting evidence of their teacher leadership enactment and cultivation, encapsulating their journey in evidence-based teacher leadership practices. These portfolios served as comprehensive records demonstrating the tangible impact of the PDM on their leadership and, consequently, on the school. The portfolios also provided insights into the growth and evolution of their leadership competencies, highlighting their commitment to continuous improvement in educational leadership.

Methodology

Research design

The research design of this study was founded upon the grounded theory methodology, selected as the most fitting theoretical framework to comprehensively investigate the influence of a transformative professional development model (PDM) implemented across three sister schools in Beirut, Lebanon, spanning a three-year timeframe, with a specific focus on its efficacy in cultivating teacher leadership. The study cohort comprised 12 teachers who actively participated in all nine Professional Days (PDs) held over the course of the three-year period, alongside three school principals. Given the relatively nascent concept of teacher leadership and the absence of a universally accepted conceptualisation (Nguyen, Harris, and Ng Citation2020), the grounded theory approach was adopted to probe into the context and gain an in-depth understanding of how teachers enact teacher leadership within such a context. This methodology involves the collection and comparative analysis of diverse data sources, with the objective of identifying conflicting instances that challenge and ultimately reinforce the evolving theory (Birks and Mills Citation2015).

Positionality statement

As researchers exploring teacher leadership within the framework of a PDM, we recognise our unique positions and perspectives shaping this study. Our team brings diverse academic backgrounds, encompassing expertise in education, leadership, and qualitative research methodologies. While we aimed for objectivity, we acknowledge the potential impact of individual experiences on the research process. A researcher had a personal connection with the organisation that owned the schools participating in the study, introducing a potential source of bias. Nonetheless, our collaborative team and commitment to robust research practices, including member checking, were designed to counteract such influences. We approached the study with transparency, openness, and a dedication to authentically representing the participants’ voices. It's important to note that the term ‘transformative PDM’ was not coined by the researchers but was adopted from the organisation that owns the participating schools to describe the model under investigation.

Participants & data collection

One of the researchers had a personal connection with the organisation that owned the three affiliated private schools, sparking her interest in collecting data related to the Professional Development Model (PDM). The schools enthusiastically welcomed this initiative and provided unwavering support, granting unrestricted access to various forms of data. Consequently, this study stemmed from an invitation to gather data throughout the implementation of a school-developed initiative.

It should be noted that Lebanon is considered one of the most privatised countries in terms of schooling. More than 50% of its student population are enrolled in private schools which often take the shape of K-12 schools.Footnote2 The Ministry of Education and Higher Education (MEHE) oversees all educational institutions in the public sector through a regional education system. Lebanon's education system is centralised, but the regulation is not direct; instead, it is managed through regional education bureaus. Public schools within the governorates are supervised by these regional education bureaus, which act as intermediaries between the schools and the education directorates at the ministry's headquarters (Ghamrawi Citation2010).

In contrast, private schools operate independently with minimal oversight from the MEHE. These institutions are not reliant on government funding, whether at the national or local level. Furthermore, the principals of private schools have autonomy in making decisions regarding teacher recruitment, curriculum, fundraising, professional development, enrolment, and other aspects (Ghamrawi Citation2011).

This study was communicated to teachers through their respective school communication channels. Consent forms were distributed, containing comprehensive information about the study's objectives and the intended use of the collected data. All teacher trainers involved in the Professional Days (PDs) expressed enthusiasm to take part in the study. The selection of participants was predicated on teachers’ roles as trainers in all nine PDs conducted throughout the three-year period. Consequently, the sample comprised 12 teachers along with the school principals from the three institutions. The characteristics of the sample are presented in .

Table 1. Characteristics of the Sample.

Structure of professional days

A professional development (PD) serves as a collaborative platform where classroom instructors share carefully planned instructional strategies, techniques, and methodologies with their peers. The structure of a PD entails an extensive educational day featuring numerous in-house workshops, typically 20 workshops per day organised into two sets of 10 workshops each, occurring concurrently during different time slots. These workshops, facilitated by teacher trainers, are complemented by a keynote speech delivered by a local university professional, the school principal, or a subject leader. Teacher trainees attend the keynote speech, and make personal selections of workshops allowing flexibility for personalised selection based on individual needs. The school hosts three PDs annually, aligning with the three terms in its academic year. On these days, parents are notified not to send their children to school, creating a dedicated and stress-free time for collaborative knowledge sharing among teachers. Following each professional day, a world café session is conducted, where teachers from each department gather to discuss how to apply the acquired knowledge and skills. This discussion results in the creation of a term plan outlining professional activities to be undertaken by the department, such as testing new teaching strategies, implementing assessment procedures, and sharing expertise gained during the PD. The subject leader oversees the fulfilment of the departmental professional term plan.

The semi-structured interviews

Semi-structured interviews spanning 35 min, on the average, were conducted with teacher trainers at the end of the third year of implementing the PDM. Parallel to this semi-structured interviews were conducted with the school principals of the three schools involved in the study. For ethical considerations, participants are identified using a letters and a number. The letter T designates a teacher trainer, while the letter P designates a principal. Moreover, a number next to the letter indicates the number is what identifies this participant for researchers. For example, T2 indicates a teacher trainers whose given number is 2, while P3 represents a school principal, given the number 3.

Interviews were designed to centre on the solicitation of teachers’ and principals’ perceptions and evidence concerning their assertions of demonstrating teacher leadership skills. In order to substantiate their claims, teachers were encouraged to present their portfolios during these interviews. These portfolios comprised artifacts that served as tangible evidence supporting the claims made by the teachers. For each question outlined in the interview schedule (refer to ) that prompted participants to suggest instances or examples of their engagement in teacher leadership activities, they were specifically instructed to provide evidence from these portfolios. This approach ensured that responses were not merely anecdotal but were substantiated with concrete examples and documented proof within the presented portfolios.

Table 2. Semi-structured Interview – Teachers’ Version.

The researchers developed their interview schedule in alignment with the self-assessment tool utilised by the school, which they adapted from the tool developed from Centre for Great Teachers and the American Institute for Research, as stated earlier in this study. Teachers’ interview schedules is presented in . A modified version of this schedule was used to gather input from school principals; however, the questions were related to their teachers rather than to themselves.

During the interviews, teachers actively showcased evidence supporting their claims by presenting self-generated portfolios. These portfolios served as comprehensive repositories of their professional accomplishments, highlighting their practical applications of teacher leadership skills. Within these portfolios, teachers presented a rich tapestry of documentation, including lesson plans, student outcomes, collaborative projects, and reflective narratives. This multifaceted approach allowed teachers to vividly illustrate how they had put their leadership abilities into action within the educational context.

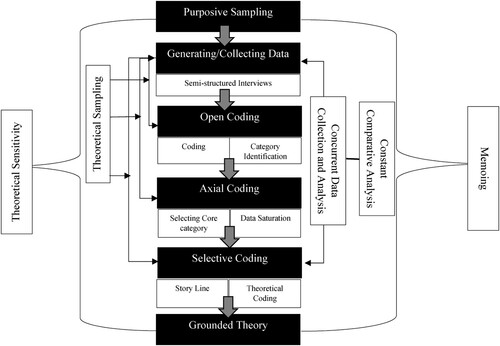

Data analysis

Data analysis followed the framework suggested by Chun Tie, Birks, and Francis (Citation2019) presented in . This figure provides a succinct overview of the intricate interplay between methods and processes that constitute the foundation for theory generation. It's evident from this framework that the progression is not linear but rather iterative and recursive, emphasising the dynamic nature of the process. The grounded theory research methodology necessitates the systematic application of distinct methods and processes. Methods can be understood as ‘systematic modes, procedures, or tools used for collection and analysis of data’ (Mackenzie & Knipe, p.196). Beginning with purposive sampling, the subsequent stages encompassed concurrent data collection and analysis. This phase involved coding activities in tandem with constant comparative analysis, theoretical sampling, and the practice of memoing. The process of theoretical sampling persisted until the point of theoretical saturation was achieved, ensuring the exhaustive exploration of emerging theoretical perspectives.

Figure 1. Research Design Framework (adapted from Chun Tie, Birks, and Francis Citation2019).

During the open coding phase, the transcript data underwent rigorous examination through iterative rounds of analysis. Each transcript was systematically scrutinised to identify recurring patterns and themes, with meticulous comparisons and contrasts made to discern similarities and differences. This meticulous process facilitated the assignment of conceptual labels to distinct segments of the data, aiding in the initial categorisation process. For example, recurring themes such as ‘teacher collaboration’ or ‘student engagement strategies’ were identified and labelled accordingly.

Transitioning to the axial coding phase, there was a deliberate focus on refining the properties associated with the initially developed categories. This phase involved the delineation of interconnected subcategories within each broader category. For instance, within the category of ‘teacher collaboration,’ subcategories such as ‘peer mentoring’ or ‘professional learning communities’ were delineated based on their unique properties and characteristics. Any emergent categories identified during this phase were seamlessly integrated into the existing framework, aligning with the principles outlined by Birks and Mills (Citation2015) for comprehensive data analysis.

n the subsequent selective coding phase, all categories were organised around a central ‘core category,’ following the framework introduced by Corbin and Strauss (Citation1990). This core category served as the focal point, encapsulating the essence of the phenomenon under study. Categories with weaker attributes or limited explanatory potency underwent meticulous evaluation. For example, subcategories lacking empirical support or failing to significantly contribute to the overarching theory were carefully reviewed and, if necessary, removed to maintain the requisite ‘conceptual density’ (Corbin and Strauss Citation1990) crucial for theoretical coherence.

Throughout the constant comparative analysis, five core categories emerged for the study. Two of these core categories were aligned with the first research question, focusing on accessing and leveraging research to enhance instruction and student learning, as well as promoting ongoing professional development. Meanwhile, three core categories were identified in relation to the second research question, encompassing themes of reciprocal empowerment, conceptual awareness, and collaborative metacognition. These core categories formed the cornerstone of the developed theoretical framework, providing a comprehensive description and explanation of the studied phenomenon.

Validity and trustworthiness

To ensure the credibility of findings, the researchers implemented a member checking process. This step was essential in fostering trust and transparency within the research process. Participants were afforded the opportunity to review the interpretations and conclusions drawn by the research team, comparing them with their intended meanings. This iterative feedback loop served as a crucial validation mechanism, reinforcing the authenticity of findings. Both in the initial stages and in the final analysis, the researchers engaged in peer discussions and feedback sessions. This collaborative approach allowed them to refine interpretations and strengthen the overall robustness of the study.

Moreover, the researchers ensured the robustness of the collected data by employing a dual validation process. First, teachers substantiated their responses with tangible evidence from their individual portfolios, providing a firsthand account of their experiences and practices. This not only enhanced the authenticity of the teachers’ perspectives but also showcased the tangible impact of teacher leadership within the PDM. Additionally, data validation extended to the input from school principals, whose insights were crucial in corroborating and triangulating the information gathered from teachers. This multifaceted approach to data validation reinforced the validity and trustworthiness of the study's findings, contributing to a comprehensive understanding of teacher leadership enactment within the transformative PDM.

Finally, the researchers in the study maintained the integrity and credibility of their findings through rigorous adherence to key principles. They carefully designed the methodology, transparently disclosed any conflicts of interest, and utilised reliable measures. Ensuring objectivity and transparency in data collection and analysis was integral, with thorough reporting of findings, including limitations. Furthermore, the research team, operating both independently and cooperatively, engaged in several iterations of transcript analysis to guarantee insightful interpretations. This collaborative endeavour led to mutual agreement between researchers regarding the interpretation of data, thereby bolstering the study's credibility.

Limitations of the study

The study is subject to methodological constraints, primarily stemming from the limited data set utilised. Despite careful selection, the sample size remains relatively small, potentially affecting the generalizability of the findings to broader populations. Moreover, the reliance on semi-structured interviews as the primary data collection method represents another significant limitation. These methodological constraints underscore the importance of future research endeavours aimed at addressing these limitations and enhancing the robustness of the findings.

While acknowledging these limitations, we contend that this case study offers valuable theoretical contributions to the literature, drawing upon the insights of Yazan (Citation2015) and Yin (Citation2014), who suggest that even a single case study can challenge widely held views. Specifically, within the context of our study, we believe it enriches the broader discourse on the transformative potential of participatory decision-making (PDM). The study presents a unique model for teacher leadership development, leaving readers, practitioners, and researchers to discern their own insights and takeaways from its findings.

Ethical considerations

Ethical considerations for this study include addressing a potential conflict of interest arising from one researcher's personal connection to the organisation that owns the three affiliated private schools. This connection may raise concerns about impartiality and objectivity. However, it is important to note that the research was conducted collaboratively by a group of researchers, ensuring a collective and unbiased approach. Measures were implemented to prevent any undue influence or bias associated with the researcher's personal connection.

Furthermore, the research study was initiated through an invitation, establishing a mutually beneficial arrangement. In this win-win situation, the researchers conducted the study for the organisation owning the three schools involved, and, in turn, the organisation gained data-driven feedback on its Professional Development Model (PDM) from prominent university professors. This arrangement aimed to contribute valuable academic insights while providing the organisation with constructive feedback on its PDM. The schools enthusiastically welcomed the study, indicating a transparent and collaborative approach to data collection.

Communication and consent procedures were meticulously designed, with comprehensive information about the study's objectives and the intended use of collected data provided to teachers. Consent forms were distributed through official channels, ensuring transparency and informed participation. These ethical safeguards were implemented to uphold the integrity of the research and protect the rights and well-being of the participants.

Findings

Evidence for teacher leadership enactment

The evidence provided by the teachers involved in the study covered seven areas where they demonstrated their enactment of teacher leadership, and these areas were meticulously captured and illustrated within their portfolios. These portfolios not only served as a repository of their accomplishments but also as a means to narrate their journey and progress in each of these crucial domains of teacher leadership. These seven areas are included under two broad categories: (1) accessing and using research to improve instruction and student learning; and (2) promoting professional learning for continuous improvement.

Accessing and using research to improve instruction and student learning

Teachers involved in this study provided evidences on accessing and using research to improve instruction and student learning. Evidences included: (1) integration of research into lesson planning; (2) customisation of instructional approaches; (3) collaboration and knowledge sharing; and (4) making data-driven decisions.

In fact, one prominent finding from our analysis of teachers’ portfolios is the consistent and deliberate integration of research findings into the development of lesson plans and instructional strategies. Teachers demonstrated a strong commitment to staying informed about the latest research in education, regularly incorporating evidence-based practices into their teaching. T3 stated that, ‘ I found that incorporating research into lesson planning isn't an extra step; it's the key to making teaching more effective’. This was echoed by T1 who said. ‘While I used to fear the word ‘research’, I became a fan of this word having known the value of research-based findings and their impact on student learning’.

Moreover, teachers exhibited a high degree of adaptability when it came to implementing research findings in their classrooms. They did not simply replicate strategies from research studies, but rather, they customised these approaches to meet the unique needs and learning styles of their students. T12 suggested, ‘I think of myself as a research-inspired teacher. It's not about blindly following research; it's about creatively adapting it to my classroom’.

In addition, teachers involved in the study revealed a significant emphasis on collaboration and knowledge sharing. Teachers frequently shared research findings and strategies with their colleagues through professional development sessions, workshops, and informal discussions. This collaborative spirit extended beyond individual classrooms, as teachers actively contributed to a culture of continuous learning within their schools. T7 stated, ‘We don't keep our successes and research findings to ourselves. We're like a community of educators always striving to improve, and that means sharing what we discover’. This cooperative mindset was also highlighted through T2 remark, ‘Our commitment to collaboration is not just a professional duty; it is the heartbeat of our school culture, where every teacher plays a part in the collective journey toward educational excellence.’

Likewise, findings also highlight the use of research data to inform decision-making related to curriculum development and assessment practices. Teachers routinely collected and analyzed data on student performance, comparing it to research-based benchmarks. This data-driven approach allowed teachers to make informed adjustments to their teaching methods and assessment strategies, resulting in measurable improvements in student outcomes. T4 stated, ‘It is incredibly satisfying to see that when we use data to inform our decisions, it leads to tangible improvements in student outcomes’. Likewise, T3 stated, ‘By aligning our curriculum and assessments with data, we empower ourselves to make precise, targeted decisions that ultimately enhance the learning journey for every student’.

Parallel to this, P2 corroborated findings by stating, ‘In our school, there's a real sense of camaraderie. We are eager to share what's working because we genuinely want to see every teacher and student succeed’. In the same vein, P1 suggested, ‘Our school culture is built on the idea that we're constantly learning from one another. Sharing research findings is like planting seeds of knowledge that grow into better teaching practices’. Similarly, P3 stated, ‘Our teachers are committed to using data like a compass in learning and teaching. It guides them in the right direction, helping them make informed decisions that benefit our students’.

Promoting professional learning for continuous improvement

Teachers involved in this study provided evidence regarding their commitment to continuous professional development. Evidences included: (1) utilising a spectrum of professional development approaches; (2) development of collaborative learning communities; and (3) becoming reflective practitioners.

First of all, teachers revealed a rich tapestry of professional development approaches they adopted in order to respond to the individual needs of their colleagues. These approaches ranged from traditional workshops and conferences to online courses, peer mentoring, and action research projects. The diversity of options allowed educators to tailor their learning experiences to their individual needs and preferences. T1 stated, ‘professional development isn't one-size-fits-all. We have a menu of options we and our colleagues choose from, that makes learning experiences truly personalized’. Likewise, T4 said, ‘From traditional workshops to online courses, peer mentoring, and engaging in action research, we curate a menu of options. This diverse approach ensures that each teacher can choose the path that resonates with their unique needs, making our learning experiences truly personalized and impactful’.

Furthermore, teachers actively participated in collaborative learning communities, recognising the value of engaging in professional development activities within a supportive network of colleagues. These communities were initiated through the PDM and continued as teachers collaborated in creating innovative teaching practices. T9 stated, ‘We co-created interdisciplinary units that combined history, science, and literature into immersive learning experiences. It challenged us to think outside the traditional subject boundaries’. Similarly, T5 said, ‘We actively engage in co-creating interdisciplinary units, breaking free from traditional subject boundaries’.

Furthermore, teachers participating in the study emphasised the role of reflective practice in their professional growth. They engaged in written self-assessment, received feedback from peers, and continually examined their teaching practices using forms and rubrics. This reflective approach allowed them to refine their skills and adapt to the evolving needs of their students. T5 stated that ‘the use of rubrics in our reflective practice has been a game-changer. It provides a structured framework for assessing our teaching and setting clear improvement goals’. Likewise, T12 stated, ‘I learned that if I am to grow, I should reflect on every single activity or decision I make in my classroom’.

Findings were also corroborated by school principals who made similar points. P1 suggested, ‘Our professional development is like a buffet; we get to sample a bit of everything. It keeps us engaged and eager to grow’. Likewise, P2 explained, ‘Through our collaborative efforts, we developed a ‘community service week’ where students were deeply involved in community outreach projects. It not only enriched their learning experiences but also instilled a sense of civic responsibility’. Finally, P3 stated, ‘It's amazing how small adjustments, identified through reflection, can lead to significant improvements in student engagement and learning outcomes’.

Teacher leadership: empowering elements of the transformative PDM

In the exploration of the second research question, findings suggest three categories that encapsulate the essence of transformative professional development in the context of teacher leadership: reciprocal empowerment, conceptual awareness, and collaborative metacognition.

Reciprocal empowerment

Reciprocal empowerment emerged as a central theme while exploring the elements of the transformative professional development model (PDM). It was viewed to play a pivotal role in fostering a culture of collaboration and growth within researched schools. Suggested benefits included an impact on teacher wellbeing; and an increased sense of collaboration and shared responsibility incurring significant improvements in the educational experience for all involved.

In fact, teachers suggested that when teachers feel empowered and valued their sense of professional fulfilment and job satisfaction soars. This, in turn, reduces burnout and stress levels among them, promoting their mental and emotional wellbeing. Furthermore, in an environment where reciprocal empowerment is nurtured, teachers are more likely to collaborate, share best practices, and support one another, creating a positive and supportive school culture. T4 stated, ‘feeling empowered as a teacher goes beyond just the classroom; it's about being part of a community that values your input and trusts your expertise.’ Another teacher emphasised the significance of reciprocal empowerment, stating, ‘In our school, it's not just about top-down leadership. We're all in this together, and our voices matter’ (T8). This sentiment resonated with school principals who also recognised that when teachers are empowered, they become not just individual instructors but active contributors to a collective pursuit of excellence: ‘An empowered teacher doesn't just teach subjects; they teach the art of resilience, adaptability, and critical thinking’ (P2).

This collaborative spirit not only benefits teachers but also ripples into the student body, where a positive and supportive atmosphere enhances the learning experience.T6 shared, ‘When we're empowered, it's not a competition; it's a collaboration’. Moreover, teachers who feel empowered are more likely to take initiative and engage in professional development willingly. T2 noted, ‘When you're empowered, you seek out opportunities to learn and grow because you know your growth benefits not only you but your students as well.’ This proactive approach to professional development not only keeps teachers motivated but also ensures that they stay current with the latest pedagogical techniques and educational research. This was also corroborated by P1 who stated, ‘Empowerment is our greatest tool; it is what transforms classrooms into arenas of possibility and students into lifelong learners’.

Conceptual awareness

In this study, both teachers and school principals shared a common understanding that teacher leadership was a skill that could be targeted and cultivated, a goal that the explored Professional Development Meetings (PDM) aimed to achieve. This heightened conceptual awareness formed the bedrock upon which teacher leadership enactment thrived. School leaders recognised the pivotal role that teacher leadership played in fostering a dynamic learning environment, and teachers, in turn, were acutely aware of their potential to lead and effect positive change within their educational communities. This shared awareness was thought to secure clarity of purpose, focused development and alignment with goals.

Indeed, participants indicated that their conscious efforts to instil teacher leadership skills placed them in a better position to achieve this goal. This was attributed to the clarity of purpose, which was not left to chance encounters. As T10 eloquently put it, ‘Our awareness of purpose drives our actions, ensuring that teacher leadership is not just a vague aspiration but a deliberate and impactful practice’. In alignment with this perspective, P3 suggested that ‘When both teachers and school leaders are consciously aware of the importance of nurturing teacher leadership skills, it becomes a shared mission’.

Moreover, participants emphasized the significance of focused development as a direct result of their heightened awareness regarding teacher leadership. They acknowledged that this awareness allowed them to channel their efforts and resources more effectively into the cultivation of teacher leadership skills. As T3 stated, ‘Our keen awareness drives our actions with precision, ensuring that teacher leadership becomes not just an abstract notion but a deliberate and impactful practice.’ In alignment with this perspective, P1 emphasised, ‘When both teachers and school leaders are consciously aware of the importance of nurturing teacher leadership, we collectively invest in the success of our students’.

Furthermore, participants emphasised that their increased awareness of teacher leadership led them to recognise the importance of aligning their efforts with school goals. This awareness not only allowed them to synchronise their initiatives with the school's overarching objectives but also increased the likelihood of effectively enacting teacher leadership. In the words of T11, ‘Our heightened awareness that we were seeking to become teacher leaders ensured that the initiative was seamlessly integrated into school goals rather than an isolated endeavor’. P2 echoed this perspective, stating, ‘When both teachers and school leaders consciously align their efforts with the cultivation of teacher leadership skills, it becomes a shared mission that propels us collectively toward the growth of our educators and the success of our students’.

Collaborative metacognition

Collaborative metacognition encompasses the shared, reflective, and deliberative thinking that occurs when educators collaboratively analyze and evaluate their teaching practices, explore innovative approaches, and collectively set goals for professional growth. Participants in this study assured that this shared reflective thinking on various practices was key ingredient for the success of the PDM in developing teacher leadership. It supported shared reflection and inquiry, co-construction of knowledge, and collective goal setting.

Teachers actively engaged in discussions where they collectively examined their teaching practices, dissected challenges, and celebrated successes. T5 stated, ‘These discussions were like a microscope for our teaching practices. We looked closely, identified areas for improvement, and celebrated the moments when our students truly thrived’. Parallel to this, P1 assured that ‘The power of our school's collaborative discussions is in their transformative nature. They fuel our teachers’ professional growth and contribute to a thriving learning community’.

In these collaborative settings, teachers were not passive recipients of information; instead, they actively co-created knowledge by sharing their experiences, insights, and expertise. This process of co-construction allowed for the development of innovative teaching strategies and the incorporation of diverse perspectives into pedagogical decision-making. T9 stated, ‘We bring our unique perspectives and experiences to the table, and together, we forge innovative approaches that benefit all our students’. Likewise, P3 suggested that ‘our educators pool their wisdom to design an enriched learning experience for our students, fostering a culture of educational innovation and excellence’.

Additionally, teachers engaged in collaborative metacognition demonstrated a shared commitment to setting and achieving collective goals. These goals often centred on improving student outcomes, enhancing instructional practices, or addressing specific challenges within their educational communities. T12 stated, ‘We define what success means, and together, we navigate towards it. It's a collective effort that ensures no student is left behind and that our teaching is as effective as it can be’. Similarly, P2 stated, ‘collective goal setting unites our teachers in a common purpose, fostering a sense of unity and shared responsibility that empowers us to achieve positive outcomes for our students’.

Discussion

This study has explored the transformative potential of a professional development model (PDM) implemented across three sister private schools in Beirut, Lebanon, spanning a three-year timeframe. The central aim was to assess the effectiveness of this PDM in nurturing and cultivating teacher leadership skills. Guided by two key research questions, this research has unveiled multiple dimensions of teacher leadership enactment.

The integration of research findings into lesson planning and instructional strategies, as observed in this study, aligns with roles attributed to teacher leaders in the literature, such as Ghamrawi (Citation2013a, Citation2013b; Citation2023a, Citation2023b), and Harris and Jones (Citation2019). These roles underscore the dynamic and evolving nature of teacher leadership in contemporary educational contexts, bridging the gap between research and practice, thus benefiting both educators and students. Moreover, the adaptability exhibited by teachers in customising research-based approaches to cater to the diverse needs of their students reflects similar findings in the literature, emphasising the importance of tailoring instruction to address unique student needs, as noted by Fairman et al. (Citation2023) and Polka et al. (Citation2016).

The study findings further highlight the significance of collaboration and knowledge sharing among teachers, resonating with the concept of professional learning communities (PLCs). These communities provide a platform for collaborative learning and the exchange of best practices, as recognised by DuFour, DuFour, and Eaker (Citation2004). The active engagement in knowledge sharing reflects teachers’ commitment to continuous learning, echoing the notion that teacher leadership extends beyond individual classrooms, contributing to a culture of collective improvement, as emphasised by Harris and Jones (Citation2019). Similarly, the utilisation of research data to inform decision-making in curriculum development and assessment practices aligns with the broader movement toward data-driven decision-making in education. This approach underscores the transformative potential of data-informed practices in improving educational outcomes, consistent with the literature and advocated by Darling-Hammond (Citation2017).

Regarding professional development, the study findings align with the literature, emphasising the importance of personalised and diversified approaches to teacher learning, as highlighted by Ghamrawi, Ghamrawi, and Shal (Citation2019). However, what sets this study apart is its attribution of these practices specifically to teacher leaders. Teacher leaders in this study embraced a spectrum of professional development options, aligning with the idea that tailored learning experiences cater to individual needs and preferences, fostering a sense of ownership and motivation. Furthermore, the development of collaborative learning communities among teachers echoes the research on the power of collaborative learning and communities of practice, recognised by Ghamrawi (Citation2022) and Patton and Parker (Citation2017). These communities provide a space for educators to engage in shared inquiry, exchange ideas, and co-create innovative teaching practices, contributing to their professional growth.

Reflective practice, a central aspect of professional development highlighted in this study, aligns with the literature on the importance of teacher reflection, as articulated by Schon (Citation1983). Schön's concept of ‘reflection-in-action’ emphasises the ongoing, adaptive nature of reflection. Still, in this study, it was attributed to teachers enacting teacher leadership, consistent with the roles described by Ghamrawi (Citation2013b) and the commitment to self-assessment, feedback, and continuous examination of their teaching practices, as recommended by Farrell (Citation2015).

In examining the transformative professional development model (PDM), this study has highlighted three key categories: reciprocal empowerment, conceptual awareness, and collaborative metacognition. Reciprocal empowerment, a central theme in these findings, aligns with the literature on distributed leadership, recognising that leadership is not confined to formal roles but can emerge from various stakeholders within an educational community. The teachers’ sense of empowerment and shared responsibility resonate with the idea that teacher leadership contributes to a more decentralised and collaborative leadership model, as discussed by Harris (Citation2009) and Harris and Spillane (Citation2008).

Within this study, it was observed that this process was not merely a one-way exchange of power and authority. Still, rather, it involved a multifaceted interplay where teachers not only received empowerment through professional development but also actively contributed to its evolution. This reciprocal empowerment was marked by a continuous feedback loop, where teachers’ insights, experiences, and expertise influenced the very professional development model designed to empower them. This collaborative and interactive aspect of reciprocal empowerment goes beyond the traditional view of leadership as a top-down structure. Instead, it exemplifies a more democratic and inclusive approach, where all stakeholders actively shape the educational landscape, consistent with the dynamic nature of leadership within the PDM.

Furthermore, conceptual awareness, as emphasised in this study, aligns with the literature on the intentional development of teacher leadership skills, as discussed by Harris (Citation2011). Teachers’ awareness of their potential as teacher leaders reflects the notion that teacher leadership can be cultivated and targeted through mutual and deliberate efforts. This awareness provides clarity of purpose, focused development, and alignment with school goals, thus giving teacher leadership a purposeful and impactful practice.

Lastly, collaborative metacognition emerged as a potent force in the development of teacher leadership within the examined PDM. Through shared reflection and inquiry, co-construction of knowledge, and collective goal setting, educators actively engaged in practices that not only refined their teaching methods but also fostered a culture of continuous improvement. This collaborative approach exemplified the collective nature of teacher leadership, where teachers jointly pursued excellence for all students, in line with DeLuca et al. (Citation2015), who conducted a scoping review on collaborative inquiry as a professional learning structure for educators.

Conclusion

Our study has demonstrated that the explored PDM is not just a conventional professional development model; rather, it represents a transformative force with the capacity to reshape the educational landscape. It serves as a catalyst for teacher leadership, propelling educators beyond their traditional roles within the classroom. The transformative essence of the PDM lies in its ability to empower teachers, nurture their leadership potential, and inspire a collective commitment to excellence in education. Its key ingredients – reciprocal empowerment, conceptual awareness, and collaborative metacognition – are the pillars that support its transformative journey.

This model challenges conventional top-down leadership structures, enabling teachers to actively engage in shaping their professional development journey. In this dynamic process, empowerment is not a one-way flow of authority but a multifaceted interplay where teachers both receive and contribute to the growth and evolution of the PDM. However, this should occur with full awareness. Awareness reflects the intentional development of teacher leadership skills, aligning with the notion that teacher leadership can be cultivated and targeted through mutual and deliberate efforts. It ensures that teacher leaders are not merely acting instinctively but with intentionality, working in harmony with the overarching objectives of their educational institutions. Collaborative metacognition, fostering a culture of continuous improvement and collective responsibility among teachers, serves as a driving force behind teachers’ active engagement in practices that cultivate their teacher leadership skills.

Embracing a transformative PDM by schools most probably lead schools toward a more empowered and involved teaching community. This model promotes a departure from traditional hierarchies, creating an atmosphere in which teachers actively participate in shaping the educational vision and goals. It supports the establishment of a culture of ongoing improvement, fostering collective responsibility among teachers to enhance educational outcomes. By adopting the principles arrived at through this study, schools might be in a position where they can expect advantages such as a more dynamic, collaborative, and forward-thinking teaching community, ultimately contributing to the overall school improvements.

Informed consent

All participants in this study were informed of the purpose of the study and how data will be used. They were assured that their identities would remain anonymous across the study.

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding provided by the Qatar National Library.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Norma Ghamrawi

Professor Norma Ghamrawi is a full professor of educational leadership & management at the College of Education in Qatar University. She has an international experience with educational development across the MENA region.

Tarek Shal

Dr Tarek Shal is an Assistant Professor of Educational Technology at the Social & Economic Survey Institute (SESRI) at Qatar University. He has an international experience with educational development across the MENA region.

Najah A.R. Ghamrawi

Professor Najah Ghamrawi is a full professor of educational psychology at the Faculty of Education of the Lebanese University. She has experience in training and capacity building in Lebanon and some Arab States.

Notes

References

- Admiraal, W., W. Schenke, L. De Jong, Y. Emmelot, and H. Sligte. 2021. “Schools as Professional Learning Communities: What Can Schools do to Support Professional Development of Their Teachers?” Professional Development in Education 47 (4): 684–698. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2019.1665573

- Al-Jammal, K., and N. Ghamrawi. 2013. “Teacher Professional Development in Lebanese Schools.” Basic Research Journal of Education Research and Review 2 (7): 104–128.

- Althauser, K. 2015. “Job-embedded Professional Development: Its Impact on Teacher Self-Efficacy and Student Performance.” Teacher Development 19 (2): 210–225. doi: 10.1080/13664530.2015.1011346

- Bae, Y., B. M. Hand, and G. W. Fulmer. 2022. “A Generative Professional Development Program for the Development of Science Teacher Epistemic Orientations and Teaching Practices.” Instructional Science 50 (1): 143–167. doi: 10.1007/s11251-021-09569-y

- Bates, C. C., and D. N. Morgan. 2018. “Seven Elements of Effective Professional Development.” The Reading Teacher 71 (5): 623–626. doi: 10.1002/trtr.1674

- Beck, J. S., K. Hinton, B. M. Butler, and P. D. Wiens. 2023. “Open to all: Administrators’ and Teachers’ Perceptions of Issues of Equity and Diversity in Teacher Leadership.” Urban Education 00420859231202998.

- Birks, M., and J. Mills. 2015. Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide. London: Sage.

- Bond, N., ed. 2022. The Power of Teacher Leaders: Their Roles, Influence, and Impact. 2nd ed. NewYork: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781003123972.

- Brodie, K. 2021. “Teacher Agency in Professional Learning Communities.” Professional Development in Education 47 (4): 560–573. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2019.1689523

- Campbell, T., J. A. Wenner, L. Brandon, and M. Waszkelewicz. 2022. “A Community of Practice Model as a Theoretical Perspective for Teacher Leadership.” International Journal of Leadership in Education 25 (2): 173–196. doi: 10.1080/13603124.2019.1643500

- Chen, J. 2020. “Understanding Teacher Leaders’ Behaviours: Development and Validation of the Teacher Leadership Inventory.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 1741143220945704.

- Chun Tie, Y., M. Birks, and K. Francis. 2019. “Grounded Theory Research: A Design Framework for Novice Researchers.” SAGE Open Medicine 7: 205031211882292. doi: 10.1177/2050312118822927

- Çoban, Ö, N. Özdemir, and MŞ Bellibaş. 2023. “Trust in principals, leaders’ focus on instruction, teacher collaboration, and teacher self-efficacy: Testing a multilevel mediation model.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 51 (1): 95–115. doi: 10.1177/1741143220968170

- Conway, J. M., and D. Andrews. 2023. “Moving Teacher Leaders to the Front Line of School Improvement: Lessons Learned by One Australian Research and Development Team.” In Teacher Leadership in International Contexts, 301–319. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Cooper, M. 2023. “Teachers Grappling with a Teacher-Leader Identity: Complexities and Tensions in Early Childhood Education.” International Journal of Leadership in Education 26 (1): 54–74. doi: 10.1080/13603124.2020.1744733

- Corbin, J. M., and A. Strauss. 1990. “Grounded Theory Research: Procedures, Canons, and Evaluative Criteria.” Qualitative Sociology 13 (1): 3–21. doi:10.1007/BF00988593.

- Cosenza, M. N. 2015. “Defining Teacher Leadership: Affirming the Teacher Leader Model Standards.” Issues in Teacher Education 24 (2): 79–99.

- Crowther, F., S. S. Kaagan, M. Ferguson, and L. Hann. 2002. Developing Teacher Leaders: How Teacher Leadership Enhances School Success. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

- Darling-Hammond, L. 2017. “Teacher Education Around the World: What Can we Learn from International Practice?” European Journal of Teacher Education 40 (3): 291–309. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2017.1315399

- DeLuca, C., J. Shulha, U. Luhanga, L. M. Shulha, T. M. Christou, and D. A. Klinger. 2015. “Collaborative Inquiry as a Professional Learning Structure for Educators: A Scoping Review.” Professional Development in Education 41 (4): 640–670. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2014.933120

- DuFour, R., R. DuFour, and R. Eaker. 2004. “PLC?” Educational Leadership 61 (8): 6–11.

- Fairman, J. C., D. J. Smith, P. C. Pullen, and S. J. Lebel. 2023. “The Challenge of Keeping Teacher Professional Development Relevant.” Professional Development in Education 49 (2): 197–209. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2020.1827010

- Farrell, S. C. 2015. “The Practices of Encouraging TESOL Teachers to Engage in Reflective Practices: An Appraisal of Recent Research Contributions.” Language Teaching Research 20 (2): 223–247. doi:10.1177/1362168815617335.

- Farrow, J., S. Schneider Kavanagh, and P. Samudra. 2022. “Exploring Relationships Between Professional Development and Teachers’ Enactments of Project-Based Learning.” Education Sciences 12 (4): 282. doi: 10.3390/educsci12040282

- Frick, W. C., and T. Browne-Ferrigno. 2016. “Formation of Teachers as Leaders: Response to the Articles in this Special Issue.” Journal of Research on Leadership Education 11 (2): 222–229. doi: 10.1177/1942775116658822

- Gaumer Erickson, A. S., P. M. Noonan, J. Brussow, and K. Supon Carter. 2017. “Measuring the Quality of Professional Development Training.” Professional Development in Education 43 (4): 685–688. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2016.1179665

- Ghamrawi, N. 2010. “No Teacher Left Behind: Subject Leadership that Promotes Teacher Leadership.” Educational Management Administration and Leadership 38 (3): 304–320. doi: 10.1177/1741143209359713

- Ghamrawi, N. 2011. “Trust Me: Your School Can be Better-A Message from Teachers to Principals.” Educational Management Administration and Leadership 39 (3): 333–348. doi: 10.1177/1741143210393997

- Ghamrawi, N. 2013a. “Teachers Helping Teachers: A Professional Development Model that Promotes Teacher Leadership.” International Education Studies 6 (4): 171–182. doi: 10.5539/ies.v6n4p171

- Ghamrawi, N. 2013b. “It Is Not Only the Principal! Teacher Leadership Architecture in Schools.” International Education Studies 6 (2): 148–159. doi: 10.5539/ies.v6n2p148

- Ghamrawi, N. 2022. “Teachers’ Virtual Communities of Practice: A Strong Response in Times of Crisis or Just Another Fad.” Education and Information Technologies 27 (5): 5889–5915. doi: 10.1007/s10639-021-10857-w

- Ghamrawi, N. 2023. “Toward Agenda 2030 in Education: Policies and Practices for Effective School Leadership.” Educational Research for Policy and Practice 1–23.

- Ghamrawi, N., and A. Abu-Tineh. 2023. “A Flat Profession? Developing an Evidence-Based Career Ladder by Teachers for Teachers–A Case Study.” Heliyon 9 (4). doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e15037

- Ghamrawi, N., N. Ghamrawi, and T. Shal. 2019. “Differentiated Education Supervision Approaches in Schools Through the Lens of Teachers.” International Journal for Innovation Education and Research 7 (11): 1341–1357. doi: 10.31686/ijier.vol7.iss11.2011

- Ghamrawi, N., T. Shal, and N. A. Ghamrawi. 2023a. “The Rise and Fall of Teacher Leadership: A Post-Pandemic Phenomenological Study.” Leadership and Policy in Schools 1–16. doi: 10.1080/15700763.2023.2197045

- Ghamrawi, N., T. Shal, and N. A. Ghamrawi. 2023b. “Exploring the Impact of AI on Teacher Leadership: Regressing or Expanding.” Education and Information Technologies 1–19.

- Ghamrawi, N., and M. Tamim. 2023. “A Typology for Digital Leadership in Higher Education: The Case of a Large-Scale Mobile Technology Initiative (Using Tablets).” Education and Information Technologies 28 (6): 7089–7110. doi: 10.1007/s10639-022-11483-w

- Gore, J., and B. Rosser. 2022. “Beyond Content-Focused Professional Development: Powerful Professional Learning Through Genuine Learning Communities Across Grades and Subjects.” Professional Development in Education 48 (2): 218–232. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2020.1725904

- Hare, C. 2012. “Applying Adult Education Principles to Security Awareness Programs.” In Information Security Management Handbook, edited by M. K. Nozaki, and H. F. Tipton, 6th ed., 207–212. NewYork: CRC Press; Taylor & Francis Group.

- Harris, A. 2009. “Distributed leadership: What we know.” Distributed leadership: Different perspectives, 11-21.

- Harris, A. 2011. “Distributed Leadership: Implications for the Role of the Principal.” Journal of Management Development 31 (1): 7–17. doi: 10.1108/02621711211190961

- Harris, A., and M. Jones. 2019. “Teacher Leadership and Educational Change.” School Leadership & Management 39 (2): 123–126. doi: 10.1080/13632434.2019.1574964

- Harris, A., and M. Jones. 2021. “Exploring the Leadership Knowledge Base: Evidence, Implications, and Challenges for Educational Leadership in Wales.” School Leadership & Management 41 (1-2): 41–53. doi: 10.1080/13632434.2020.1789856

- Harris, A., M. Jones, and T. Crick. 2020. “Curriculum Leadership: A Critical Contributor to School and System Improvement.” School Leadership & Management 40 (1): 1–4. doi: 10.1080/13632434.2020.1704470

- Harris, A., and J. Spillane. 2008. “Distributed Leadership Through the Looking Glass.” Management in Education 22 (1): 31–34. doi: 10.1177/0892020607085623

- Huggins, K. S., K. Lesseig, and H. Rhodes. 2017. “Rethinking Teacher Leader Development: A Study of Early Career Mathematics Teachers.” International Journal of Teacher Leadership 8 (2): 28–48.

- Jackson, A., C. Mawson, and C. A. Bodnar. 2022. “Faculty Motivation for Pursuit of Entrepreneurial Mindset Professional Development.” Entrepreneurship Education and Pedagogy 5 (3): 320–346. doi: 10.1177/2515127420988516

- Katzenmeyer, M., and G. Moller. 2009. Awakening the Sleeping Giant: Helping Teachers Develop as Leaders. 2nd ed. CA: Corwin Press.

- Killion, J. P. 1996. “Moving Beyond the School: Teacher Leaders in the District Office.” In Every Teacher as a Leader: Realizing the Potential of Teacher Leadership, edited by G. Moller, and M. Katzenmeyer, 63–84. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Knowles, M. 1973. The Adult Learner: A Neglected Species. Houston, TX: Gulf Publishing Company.

- Knowles, M. S., E. F. Holton, and R. A. Swanson. 2005. The Adult Learner: The Definitive Classic in Adult Education and Human Resource Development. 6th ed. London: Taylor & Francis Group.

- Kyza, E. A., A. Agesilaou, Y. Georgiou, and A. Hadjichambis. 2022. “Teacher–Researcher co-Design Teams: Teachers as Intellectual Partners in Design.” In Teacher Learning in Changing Contexts, 175–195. London: Routledge.

- Lieberman, A., and L. Miller. 1999. Teachers: Transforming Their World and Their Work. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Lumpkin, A. 2016. “Key Characteristics of Teacher Leaders in Schools.” Administrative Issues Journal: Connecting Education, Practice, and Research 4 (2): 14.

- McGill, R. M. 2021. Mark. Plan. Teach. 2.0. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Mockler, N. 2022. “Teacher Professional Learning Under Audit: Reconfiguring Practice in an age of Standards.” Professional Development in Education 48 (1): 166–180. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2020.1720779

- Moller, G. 2006. “Teacher Leadership Emerges Within Professional Learning Communities.” Journal of School Leadership 16 (5): 520–533. doi: 10.1177/105268460601600505

- Nguyen, D., A. Harris, and D. Ng. 2020. “A Review of the Empirical Research on Teacher Leadership (2003–2017).” Journal of Educational Administration 58 (1): 60–80. doi: 10.1108/JEA-02-2018-0023

- Oppi, P., and E. Eisenschmidt. 2022. “Developing a Professional Learning Community Through Teacher Leadership: A Case in one Estonian School.” Teaching and Teacher Education: Leadership and Professional Development 1: 100011.

- Osmond-Johnson, P. 2017. “Leading Professional Learning to Develop Professional Capital: The Saskatchewan Professional Development Unit's Facilitator Community.” International Journal of Teacher Leadership 8 (1): 26–42.

- Pan, H. L. W., P. D. Wiens, and A. Moyal. 2023. “A Bibliometric Analysis of the Teacher Leadership Scholarship.” Teaching and Teacher Education 121: 103936. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2022.103936

- Patton, K., and M. Parker. 2017. “Teacher Education Communities of Practice: More Than a Culture of Collaboration.” Teaching and Teacher Education 67: 351–360. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2017.06.013