ABSTRACT

Welfare chauvinism is often understood as the sentiment that the benefits and services of the welfare state should primarily be given to the native population and not immigrant minorities. Using linear regression on data from the 8th wave of the European Social Survey, this study explores how political attitudes and negative attitudes towards different immigrant groups affect welfare chauvinistic attitudes in six countries: the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Estonia, Lithuania and Slovenia. In contrast to other studies, we do not find a clear ‘East-West’ distinction between the amount of welfare chauvinistic attitudes found in the six countries compared to Western Europe. Additionally, we find that hostility towards immigrants of a different ethnicity is a strong predictor of welfare chauvinistic attitudes in five of the sampled countries, while in Lithuania, there is an opposite effect, where hostility towards ethnically similar immigrants seem to be a much stronger predictor. Furthermore, we find evidence that individuals with more right-leaning values and political orientation cannot be said to be more welfare chauvinistic. This may indicate a broad agreement in these societies on the exclusion or minimisation of immigrants’ rights to social benefits.

ABSTRAKT

Velferdssjåvinisme anses som en holdning knyttet til at tjenestene og rettighetene fra velferdsstaten hovedsakelig bør gis til majoritetsbefolkningen, og ikke til innvandrere. Denne studien bruker lineær regresjon ved hjelp av data fra den åttende European Social Survey runden for å utforske hvordan politiske holdninger og negative holdninger til ulike innvandrergrupper påvirker velferdssjåvinistiske holdninger i seks land: Tsjekkia, Ungarn, Polen, Estland, Litauen og Slovenia. I motsetning til andre studier, så finner vi ikke en klar «øst-vest» forskjell i mengden velferdssjåvinistiske holdninger i de seks landene sammenliknet med Vest-Europa. I tillegg finner vi at negative holdninger mot etnisk ulike innvandrere er en sterk prediktor av velferdssjåvinistisme i fem av de seks landene. I Litauen derimot er det en motsatt effekt, hvor negative holdninger til etnisk like innvandrere er en mye sterkere prediktor. Vi finner også at personer med mer høyre-orienterte verdier og orienteringer ikke nødvendigvis er mer velferdssjåvinistiske. Dette kan tyde på bred enighet i disse samfunnene om at innvandrere bør ekskluderes fra velferdsstaten eller at deres sosiale rettigheter bør minskes.

Introduction

A growing number of studies are exploring majority populations’ attitudes towards the inclusion of immigrants and ethnic minorities into the modern welfare state and the benefits and services this would entail. The sentiment that these benefits and services should primarily be for the native majority and not the immigrant populations is often referred to as welfare chauvinism (Careja & Harris, Citation2022). However, studies on welfare chauvinism are often primarily limited to the welfare states of Western Europe (Careja & Harris, Citation2022; Moise, Citation2020). In this study, we contribute to the field by exploring these attitudes in-depth within six countries in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE); The Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Estonia, Lithuania and Slovenia. By exploring a more limited set of countries allows for deeper insights into the sources underlying welfare chauvinism in each country and to compare these sources between countries in a region which has often received less attention than Western Europe.

Studies focusing on attitudes towards immigrants in Central and Eastern Europe have begun to increase gradually in recent years (See Bell et al., Citation2022; Bessudnov, Citation2016; Gorodzeisky, Citation2021; Lancaster, Citation2022; Leykin & Gorodzeisky, Citation2023). These studies often show that there are considerably higher levels of exclusionary attitudes towards immigrants in this region despite immigrant populations often being quite low (Bell et al., Citation2021, Citation2022; Bello, Citation2017; Gorodzeisky & Leykin, Citation2022).Footnote1 Additionally, these studies often find that theoretical concepts and frameworks developed in the ‘West’ do not necessarily easily translate to other contexts. Leykin and Gorodzeisky (Citation2023), for example, found that right-leaning conservative individuals were not necessarily more anti-immigrant than more centre or left-leaning individuals in a post-socialist context. Similarly, Bell et al. (Citation2022) found that radical right voters in CEE were not significantly more hostile towards immigrants than voters of more mainstream and green parties.

Building on these studies, we explore a specific dimension of the above-mentioned attitudes that are of clear significance for field of social work. Here, it is primarily of interest to further investigate the concept of welfare chauvinism in the different and unexplored context of post-communist Europe. The term welfare chauvinism was first coined to describe the structural changes and new cleavages of Western European party politics at the end of the twentieth century. In their study on the new changes of the Norwegian and Danish radical right parties, Andersen and Bjørklund (Citation1990) defined welfare chauvinism rather briefly as the belief that ‘the welfare services should be restricted to our own (p. 212)’. Kitschelt and McGann (Citation1995) expanded upon the concept by emphasising that the welfare state is presented as a system of social benefits and services that belong to the ethnically defined community that contributed to it.

Previous studies have shown that welfare chauvinism is mainly connected to the populist radical right parties and their voters (Careja & Harris, Citation2022). Voters of these parties often have negative attitudes towards immigrants (Arzheimer, Citation2018; Rydgren, Citation2008) which has also been found to be a predictor of welfare chauvinistic attitudes (Magni, Citation2021; Bell et al., Citation2023a). Others have also pointed towards welfare chauvinism and neoliberalism being closely linked, as they both share the idea of constraining solidarity and separate the deserving from the undeserving (Grdešić, Citation2019; Keskinen et al., Citation2016). It is also evident that individuals who are more sceptical towards the welfare state and benefits in general have also been found to be more welfare chauvinistic (Bell et al., Citation2023a, Citation2023b). However, the above-mentioned studies have mainly focused on welfare chauvinism in Western Europe, and it is unclear if this link can be found in CEE, where the hybrid nature of the post-communist welfare regimes have created a different political environment than other welfare regimes and where attitudes towards immigrants is clearly distinct from those found in Western Europe (Saxonberg & Sirovátka, Citation2018; Bell et al., Citation2021).

Against this backdrop, this study explores two interrelated research questions: (i) how do various political attitudes influence welfare chauvinistic attitudes in six CEE countries, and (ii) how negative sentiments towards different immigrant groups affect welfare chauvinistic attitudes in the selected countries. In addition we also explore other predictors of welfare chauvinism in the six countries.

Although other studies have investigated aspects of welfare chauvinism in the region (Cinpoeş & Norocel, Citation2020; Savage, Citation2023), we are, to the best of our knowledge, the first study that attempts to explain the welfare chauvinistic attitudes found in this region.Footnote2 Using the 8th round of the European Social Survey (ESS) from 2016–2017, we first provide a descriptive overview of welfare chauvinism in CEE, and thereafter explore the nuances of welfare chauvinism in the region. We show that there is not a clear ‘east-west’ divide on welfare chauvinism. In second part of our analysis, we use linear regression analysis to explore predictors of welfare chauvinism, and find that hostility towards immigrants of a different ethnicity/race are a strong predictor of welfare chauvinism in five of the six countries. Furthermore, we find evidence that individuals with more right-leaning attitudes and political orientation are not necessarily more welfare chauvinistic, indicating a broad agreement across the political spectrum in these societies on the exclusion or minimisation of immigrants’ rights to social benefits.

Welfare Chauvinism and its predictors

Welfare chauvinism was introduced as an academic concept to explain the success of the populist radical right parties in the 1990s, which emphasised a stronger need for redistribution, however mainly to the majority populations and not the immigrant minorities (Andersen & Bjørklund, Citation1990; Kitschelt & McGann, Citation1995). Since the 1990s, welfare chauvinist policies have also become the cornerstone of the populist radical right parties’ socio-economic policy agenda both in election campaigns and in power (Careja & Harris, Citation2022). The political success of this position also led to more mainstream parties to adopt certain welfare chauvinistic policies (Abou-Chadi & Krause, Citation2020; Leruth & Taylor-Gooby, Citation2021; Schumacher & Van Kersbergen, Citation2016). These polices also affect social workers as well as other providers of social benefits and public services (Valenta & Berg, Citation2010; Bell et al., Citation2023b). Indeed, they may result in significant changes in the funding of social services and integration programmes directed to specific migrant groups. Such restrictions contribute to curtailing the ability of social workers to provide relevant social programmes and integration assistance to certain categories of migrants (Valenta & Berg, Citation2010; Valenta & Strabac, Citation2011; Field et al., Citation2021). They may even partly or completely exclude various immigrant groups from being able gain to social benefits or services (Valenta & Berg, Citation2010; Valenta & Strabac, Citation2011; Baldi & Goodman, Citation2015; Eugster, Citation2018). Welfare chauvinist policies tend to be first adopted as a supplement or in combination with restrictive immigration and refugee policies aimed towards deterring irregular migrants, asylum seekers, temporary labour migrants and overstayers (Valenta & Strabac, Citation2011, Valenta & Thorshaug, Citation2013; Minderhoud, Citation1999; Robinson, Citation2014).

Welfare chauvinist sentiment has been found to follow a traditional left/right voting pattern: voters for the radical left and green parties hold the least welfare chauvinist attitudes, and the radical right voters display the highest levels of welfare chauvinism (Eger & Valdez, Citation2015; Goerres et al., Citation2018; Jylhä et al., Citation2019). A central reason as to why radical right voters are more welfare chauvinist is that the predictors of both welfare chauvinism and radical right voting often overlap. Anti-immigrant attitudes, for example, have been found to be important drivers of both voting for radical right parties (Arzheimer, Citation2018; Rydgren, Citation2008) and welfare chauvinistic attitudes (Bell et al., Citation2023b; Magni, Citation2021).

Concerning socioeconomic factors, radical right-wing parties have been successful among men, the working class, and individuals with relatively low education (Jylhä et al., Citation2019). Again, these are factors are strongly connected to welfare chauvinistic attitudes (Bell et al., Citation2023a; Careja & Harris, Citation2022; Ford, Citation2016; Hjorth, Citation2016; Heizmann et al., Citation2018; Kros & Coenders, Citation2019). This is often linked to viewing immigrants as a threat to the majority group’s economic and cultural power in society (Blumer, Citation1958; Stephan et al., Citation2016; Tajfel & Turner, Citation1986). Individuals who occupy a lower level of socio-economic status would be more likely to perceive immigrants as an economic threat, as immigrants often occupy the same socio-economic status (Greve, Citation2020). Competition over welfare benefits, affordable housing, and other services are therefore perceived as a zero-sum game in which one group wins at the expense of the other (Heizmann et al., Citation2018). These threat perceptions can then lead to welfare chauvinistic attitudes that seek to limit immigrants’ opportunity to receive these benefits. Whether someone espouses these values could also predict their voting for political parties who have welfare chauvinistic social policies.

Still, as two recent review studies have highlighted, most research conducted on welfare chauvinism, both in terms of policy and attitudes, are conducted in Western European countries (Careja & Harris, Citation2022; Rinaldi & Bekker, Citation2020). We therefore know little of the phenomenon in other contexts, such as for example Eastern European EU countries. Scholarship on migration and political attitudes in this region has often shown quite different findings compared to the main theoretical frameworks developed in the West (See Bell et al., Citation2022; Gorodzeisky & Leykin, Citation2020, Citation2022; Leykin & Gorodzeisky, Citation2023; Wojcik et al., Citation2021). These differences may be explained by the different post-war political and migration developments from Western Europe, as communist rule severely limited migration in the communist region (De Haas et al., Citation2022; Mazurkiewicz, Citation2019). Likewise, the legacy of 50 years of communism has influenced not only the welfare states themselves but also the population’s expectations of them (Fenger, Citation2007; Saxonberg & Sirovátka, Citation2018).

Welfare chauvinism and central and Eastern Europe

The Central and Eastern European welfare states are often characterised as hybrid welfare regimes, as they are a mix of the Bismarckian pre-communist era, communist-era policies and tendencies towards neoliberal residualist reforms (Saxonberg & Sirovátka, Citation2018). Fenger (Citation2007) also showed how there is a clear distinction between previous communist countries in Europe and the famous typology provided by Esping-Andersen (Citation1990). The communist legacy of full employment with relatively high wages, heavily subsidised food and rent as well as free or cheap healthcare, education and cultural services (Deacon, Citation2000; Fenger, Citation2007) has also shaped these populations’ expectation towards what the welfare state should provide (Saxonberg & Sirovátka, Citation2018). Support for generous welfare policies is therefore high in these countries, even among supporters of the mainstream right and radical right parties (Savage, Citation2023; Saxonberg & Sirovátka, Citation2018). This has led scholars to question the validity and transferability of the traditional left/right political spectrum in the post-communist space (Gorodzeisky et al., Citation2015; Leykin & Gorodzeisky, Citation2023; Wojcik et al., Citation2021).Footnote3

Against this backdrop, this study explores multiple factors that contribute to variations in the attitudes of CEE populations towards the inclusion of immigrants in local welfare systems with particular emphasis on political attitudes and attitudes towards different categories of immigrants. Regarding people’s political attitudes, we closely follow Leykin and Gorodzeisky’s (Citation2023) recent study on right-wing sentiment and anti-immigrant attitudes in Central and Eastern Europe. They found that political orientation in the post-socialist space has little to no relevance in explaining anti-immigrant attitudes. Of the 20 countries surveyed in their study, right-leaning orientation was connected to anti-immigrant attitudes in only four countries (Croatia, Hungary, Poland, and Slovenia), and among these, the effect sizes were considerably smaller than the ones found in Western Europe. Additionally, in five of the countries, right-leaning individuals expressed more positive attitudes towards immigrants than left-leaning ones. The authors argue that because of the communist legacy in these countries, the political left can be associated with not only social and cultural liberalism in the Western sense but also authoritarian communism of the past (Leykin & Gorodzeisky, Citation2023; Whitefield, Citation2002). Thus, other political values that are often associated with more right-wing-leaning individuals also do not necessarily hold in this context (Aspelund et al., Citation2013; Leykin & Gorodzeisky, Citation2023).

We expand upon the study by Leykin and Gorodzeisky (Citation2023) by exploring welfare chauvinism in the post-communist context. This phenomenon has two aspects that are generally associated with right-wing attitudes in Western Europe: hostility towards immigrants, and a more restrictive welfare state. Our study provides an in-depth investigation into these two aspects. We first explore the redistribution aspect, as previous studies have highlighted that individuals who are more sceptical of welfare benefits and want a more restrictive welfare state also do not want immigrants to have access to these welfare services (Bell et al., Citation2023a, Citation2023b). This follows the more neoliberal aspect of welfare chauvinism; Keskinen et al. (Citation2016), for example, argue that neoliberalism is combined with the culturing othering of immigrants. Koning (Citation2022) further shows that around 60 percent of those who oppose granting immigrants the benefits of the welfare state in Western Europe do so for more neoliberal reasons rather than socialist ones. How this plays out in a post-communist context is more unclear, as Savage (Citation2023) has highlighted that radical right-wing voters in Central and Eastern Europe hold both welfare chauvinistic attitudes and pro-distribution ones.

Not surprising, opposition towards immigrants has been found to be a strong predictor of restricting immigrants’ rights in the welfare state (Bell et al., Citation2023b; Gorodzeisky, Citation2013; Hjorth, Citation2016; Magni, Citation2021). It is however interesting to explore this aspect in the post-communist space, as the migration history in the region is quite different from that of Western Europe (De Haas et al., Citation2022; Mazurkiewicz, Citation2019) and the prevalence of exclusionary attitudes towards immigrants is considerably higher than in Western Europe (Bell et al., Citation2021; Bello, Citation2017).

In the Central and Eastern European context, we also need to discuss who the immigrants and ethnic minorities are in different countries within the region, as this factor may influence perceptions of whether they deserve social benefits and inclusion in the welfare system. It is worth highlighting that at the time the data was collected for this analysis (2016–2017) immigrant populations in most CEE countries were considerably smaller than in Western European (Gorodzeisky & Leykin, Citation2022).Footnote4 In certain CEE countries, a significant portion of the immigrant population consists of co-ethnics or immigrants from neighbouring countries. In contrast, in other countries in the region, the migrant population is more complex and might even include immigrants and ethnic minorities from countries with a history of conflict and strained relations with the receiving countries examined in this study (Bessudnov, Citation2016).

Methods

This study uses data from the eighth wave of the European Social Survey (ESS) collected in 2016-2017.Footnote5 The original dataset contains 23 European countries; however, as we are interested in welfare chauvinism found in CEE, we are left with 6 countries and a total sample size of 8926 respondents across the Czech Republic (1957), Estonia (1664), Hungary (1285), Lithuania (1616), Poland (1367) and Slovenia (1037).Footnote6 Individuals who were born in another country have been excluded from the analysis, and post-stratification weights are applied throughout the analysis.

The dependent variable for the study is based on the question ‘Thinking of people coming to live in [country] from other countries, when do you think they should obtain the same rights to social benefits and services as citizens already living here?’ The respondents had five different answers to choose from: (1) Immediately on arrival; (2) After living in [country] for a year, whether or not they have worked; (3) Only after they have worked and paid taxes for at least a year; (4) Once they have become a [country] citizen; and (5) They should never get the same rights.Footnote7 Considering the ordinal nature of the variable we would normally have conducted an ordinal logistical regression. However, as the assumption of parallel lines is violated we apply linear regression for the analysis.Footnote8 We therefore treat the variable as a continuous variable, measuring respondents wanting to make it continuously more difficult for immigrants to receive the benefits of the welfare state.

Among the independent variables, we have included several control variables, which have been found to influence attitudes towards immigrants and welfare chauvinism (Careja & Harris, Citation2022; Dražanová, Citation2022). These variables include the following: gender (female = 1); age (in years); education (in years); urban (1 = farm or home in countryside, 5 = a big city); satisfaction with income (4 = living comfortably with current income); and unemployed (1 = unemployed, actively looking for job). Additionally, we have included individuals’ satisfaction with the state of the economy and health services, as individuals’ perception of more macroeconomic aspects have been found to influence welfare chauvinism (Bell et al., Citation2023a).

There are various ways to which we would measure welfare attitudes among the respondents. Eger and Breznau (Citation2017) separate between two distinct welfare attitudes that can be measured across countries using the ESS. The first is a scale that measures welfare state support. The scale includes variables measuring respondents’ attitudes regarding the responsibility of the government to provide healthcare, childcare, sick leave, employment programmes, and a standard of living for the old and unemployed (Eger & Breznau, Citation2017, p. 446). Ideally, we would have included such a scale; however, it only has a satisfactory Cronbach’s alpha score for the Czech Republic (0.732).Footnote9 We therefore use the second option, attitudes towards redistribution, which is captured by the variable measuring whether the respondents disagree strongly (1) or agree strongly (5) that the government should reduce differences in income levels. We expect individuals who wish the government to reduce income differences to be less welfare chauvinistic.

Additionally, we follow Leykin and Gorodzeisky (Citation2023) and include a variable measuring where the respondent identifies on the left-right spectrum (0 = left, 10 = right). Still, there are some difficulties with the use of the variable, as many individuals in the sample answered that they ‘do not know’ to the question of where they are on the political spectrum. In the most extreme case of Lithuania, around 25 percent of the sample answered that way. As we want to keep these individuals for our analysis, we have decided to give those who answer ‘do not know’ the value of 5 on the left-right spectrum, as one may categorise these individuals as neither left nor right. However, as a robustness check, we have tested the same models with the original variable and find no difference in its effect across all countries.Footnote10

Additionally, we wish to explore the relationship between anti-immigrant attitudes and welfare chauvinism, as previous studies have highlighted how individuals often distinguish between ‘deserving’ and ‘undeserving’ immigrants (Keskinen et al., Citation2016). We therefore include two measures of anti-immigrant attitude: attitudes towards individuals of the same race/ethnicity and attitudes towards individuals of a different race/ethnicity. Both are based on a question asking if they would let many (1) or no (4) immigrants of a different/same race/ethnicity to come and live in their country. Based on previous research we expect anti-immigrant attitudes towards individuals of a different race/ethnicity to be a stronger predictor of welfare chauvinism across all countries (See Bell et al., Citation2023b; Ford, Citation2016; Hjorth, Citation2016).Footnote11

However, the inclusion of these two variables is not necessarily unproblematic. Two potential problems therefore need to be addressed; the first is the issue of multicollinearity, which could occur because the two anti-immigrant variables may correlate highly with each other. This would make it difficult to determine the individual effect of the two variables. However, we conducted a VIF-test on the final models, which indicated that this was not an issue.Footnote12 Another concern could be that welfare chauvinism is simply just another measure of an anti-immigrant attitude. However, investigating the relationship between exclusion from the country and exclusion from the social system, Gorodzeisky and Semyonov (Citation2009) argue that they are two similar but distinct forms of exclusion. Attitudes towards exclusion from the welfare system were found to be dependent on exclusion from the country, and not vice versa (Gorodzeisky & Semyonov, Citation2009).

Results

The empirical part of this study is divided into two interrelated sections. We commence our analysis with an overview of relevant general trends to provide context and add nuance to existing perceptions of welfare chauvinism in Central and Eastern Europe. Following that, we provide a more detailed regression analysis of the factors that influence welfare chauvinism with particular emphasis on political attitudes and attitudes towards different immigrant groups.

Facets and variations of welfare chauvinist attitudes in Central and Eastern Europe

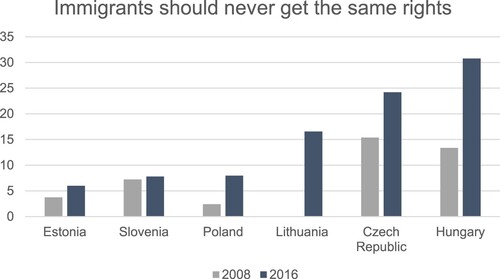

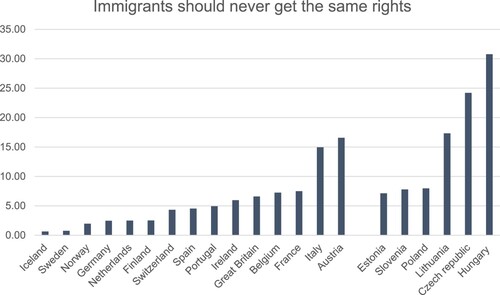

Previous studies have highlighted how there is often a considerable difference between Western and Eastern Europe in terms of their attitudes towards immigrants (Bello, Citation2017; Bell et al., Citation2021). therefore investigates if there is a clear West–East divide when it comes to the most extreme values on our measure of welfare chauvinism – that immigrants should never get the same rights as the majority population.

Figure 1. Percentage of individuals across countries stating that immigrants should never get the same rights.

illustrates that the levels of welfare chauvinism are more intricate than what is portrayed through a simple West–East division, as other studies have shown (Bell et al., Citation2023a). Indeed, such a broad distinction as ‘West’ and ‘East’ masks variations within the Eastern European countries. To be sure, the most extreme attitudes in Europe can be found in two Eastern European countries, Hungary and the Czech Republic, where up towards 30 percent of the respondents in Hungary has stated that immigrants should never get the same benefits/services as the majority population.

While the more extreme forms of welfare chauvinism are common in Hungary and the Czech Republic, the attitudes found in other countries resemble those in Western Europe. In fact, welfare chauvinistic sentiments in Lithuania can be likened to the attitudes found in Italy and Austria (see ). Additionally, the percentage of individuals stating that immigrants should never receive welfare state benefits in Estonia, Slovenia, and Poland is relatively low and comparable to those found in more inclusive Western European countries with a long history of migration, such as France, Belgium, and Great Britain. Therefore, while CEE countries on average are certainly among the most restrictive in Europe, a clear divide between Western and Central Eastern Europe is not necessarily as distinct as previous studies on more general types of anti-immigrant attitudes have suggested (Bello, Citation2017; Bell et al., Citation2021).

Additionally, CEE countries vary in terms of how welfare chauvinism has evolved over time. shows that the most extreme form of welfare chauvinism in 2008 and 2016 and allows us to view the supposed changes since 2008.Footnote13 What is clear is that these attitudes were relatively stable in Estonia and Slovenia, while there has been a considerable increase in Hungary, the Czech Republic, and to some extent Poland. Immigration became a politicised issue for the first time in Hungary and Poland in 2015–2016 during the refugee crisis (Hutter & Kriesi, Citation2022). Likewise, Savage (Citation2023) highlights how political actors began to emphasise welfare chauvinism towards immigrants during and after the refugee crisis.

Factors influencing welfare chauvinism in Central and Eastern Europe

shows the regression analysis in all six countries. The first aspect to highlight is that many of the variables previously identified as important for explaining welfare chauvinism (Careja & Harris, Citation2022) do not have an effect across most countries in our study. In fact, factors such as gender, age and being unemployed do not have an effect across all six countries, while individuals’ satisfaction with their own income and that of the national economy only have an effect in the Czech Republic. Another puzzling aspect is the effect of the urban/rural variable, which shows that it has no effect in four countries and an opposite effect between Estonia and Hungary. In Estonia, it has the expected effect of more rural individuals being more welfare chauvinistic, while in Hungary, it shows that more urban individuals are in fact more welfare chauvinistic. This urban/rural divide over attitudes in Hungary is compatible with earlier studies, as Bell et al. (Citation2022) have also previously found that individuals living in more urban areas in Hungary were surprisingly more likely to exhibit a racist attitude than more rural individuals.

Table 1. Linear regression of welfare chauvinism in the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Lithuania, Poland and Slovenia.

Our results, however, differ somewhat from Leykin and Gorodzeisky’s (Citation2023) study on right-wing political orientation and anti-immigrant attitudes.Footnote14 In their study, the authors showed that more right-leaning individuals in Hungary, Poland and Slovenia were more hostile towards immigrants, while right-leaning individuals in the Czech Republic, Estonia and Lithuania were in fact more positive towards immigrants. Our results show however that right-leaning individuals in the Czech Republic, Lithuania and Hungary are in fact also more welfare chauvinistic, with Hungary having somewhat of a stronger effect than the former two. In contrast, we find no effects in Estonia, Poland and Slovenia. Furthermore, concerning the measure of the attitudes towards redistribution, there are interesting, contra-intuitive effects – particularly in Hungary and Lithuania, where we can see that individuals who hold a more left-wing type of attitude regarding redistribution are in fact more welfare chauvinistic. We also see that the coefficient in Hungary is much stronger than in Lithuania indicating that such political inclination is likely a more important aspect for explaining welfare chauvinism in Hungary than Lithuania.

The above-presented results highlight several important findings. The first being what several other studies have highlighted: the classical division of anti-immigrant attitudes between left wing and right wing is often of limited applicability in the post-communist space (Gorodzeisky et al., Citation2015; Leykin & Gorodzeisky, Citation2023; Wojcik et al., Citation2021). Indeed, in large multilevel models that examine both Western European countries and post-communist Eastern ones, a variable measuring the respondents’ placement on the left/right spectrum should be conducted with separate models for Western and post-communist Europe, as it does not seem to be the same phenomenon in the two parts.

Second, our results show that hostility towards granting immigrants the benefits of the welfare state is not primarily because of neoliberal values, as Koning proposed, since such values were a main driving force of welfare chauvinism in Western Europe (Koning, Citation2022). Lastly, our findings are in line with Leykin & Gorodzeisky’s (Citation2023) argument that individuals with radical right stances in CEE countries may effectively combine exclusionist attitudes towards immigrants with economically left-wing values. To put it simply, they endorse generous redistribution, welfare services and benefits; however, these are exclusively reserved for the native ethnic majority population in the country. Idiosyncrasies of the Hungarian case are also recognised in other studies. For example, Lugosi (Citation2018) highlights that Hungary stands out among the Central and Eastern European countries, as cultural issues, rather than economic ones, have been a defining feature in Hungarian politics since the democratic transition.Footnote15 It is also indicated that immigration became highly politicised both during and after the refugee crisis of 2015–2016 (Hutter & Kriesi, Citation2022).

As expected, anti-immigrant attitudes are important drivers for welfare chauvinism in all six countries. However, there are important nuances between the countries. The first among these is how in Hungary the Czech Republic and Slovenia, hostility towards immigrants of a different race/ethnicity is a considerably stronger predictor of welfare chauvinism than the same attitudes towards more ethnically similar immigrants. This same tendency can also be found in Estonia and Poland. However, the differences in effect sizes are nowhere near comparable to those found in Hungary and the Czech Republic. Although this finding is not necessarily surprising, as more culturally different immigrants are often seen as less deserving of welfare benefits and services than more culturally similar ones (Bell et al., Citation2023b; Ford, Citation2016), the considerable difference in the strength of the coefficient between the Czech Republic, Slovenia and Hungary with the rest of the sample is quite surprising – especially considering that the largest immigrant groups at the time of data collection in these countries consisted of European migrants, while immigrants form the Middle East and Africa are near non-existent in these countries (United Nations, Citation2020).

In Slovenia, our findings reveal different results, as only animosity towards ethnically and racially different immigrants seems to impact welfare chauvinistic attitudes. It is important to acknowledge that Slovenia’s immigrant population is primarily composed of individuals from neighbouring countries, with whom Slovenia shares strong historical and cultural bonds. These groups have been residing in the country for decades (Ramet & Valenta, Citation2016). In contrast, scepticism towards ethnically and racially distinct migrants has grown more pronounced in recent times. It seems that this shift occurred in 2015, when the nation experienced a notable influx and transit of refugees and asylum seekers from non-European countries. These irregular migrations triggered a xenophobic discourse, leading the government to emphasise securitisation, resulting in heightened public apprehension and unease (Župarić-Iljić & Valenta, Citation2019).

Lithuania presents a distinct case as well. Compared to other countries in the study, hostility towards more ethnically and racially similar immigrants is a considerably stronger predictor of welfare chauvinism in Lithuania than hostility towards more ethnically different ones. The coefficient also stands out when compared to the other countries as it is considerably stronger than in the other countries. It should be noted that the three largest immigrant groups in Lithuania are from Russia, Belarus and Ukraine (United Nations, Citation2020). Considering Lithuania’s complicated and even antagonistic relationship with the Soviet Union and Russia, this may be related to the Russian minority living in the country.Footnote16

Lastly, we would like to comment on the explanatory power of the statistical models, represented by the levels of R2 for the six models. Previous research in the region has often showed that the explanatory power of the statistical models is often much lower than that in Western Europe (Bell et al., Citation2022; Vala & Pereira, Citation2018). We have observed a similar trend in our study. However, the explanatory power of our statistical models for Hungary and Lithuania is considerable – well over 20 percent. This indicates that the variables in the two models effectively elucidate the factors influencing welfare chauvinistic attitudes within these two countries. We should however note that the inclusion of variables measuring attitudes towards immigrants likely substantially increases the explanatory power of the models. As for the other countries in the study, the explanatory power of the statistical models is considerably lower, resembling the models found in other studies conducted in the region. Consequently, there remains a considerable amount of unexplained variance in these countries, necessitating further research.

Conclusion

This study contends that the most exclusionary form of welfare chauvinism reaches its peak in specific Central and Eastern European countries. However, a clear East–West distinction in these attitudes, as emphasised by previous studies, is not evident (Bell et al., Citation2021, Citation2023a; Bello, Citation2017). Instead, there are similar levels of the most exclusionary forms of welfare chauvinism between Poland, Estonia and Slovenia and countries with a long history of migration, such as Great Britain, France and Belgium. Lithuania, meanwhile, has comparable levels to Italy and Austria. Additionally, we show how hostility towards more ethnically different immigrants are a strong predictor across all six countries, although in Lithuania, hostility towards more ethnically similar immigrants has a much stronger effect.

We have proposed that some of our results may be related to the refugee crisis of 2015-2016. Indeed, intolerance towards immigrants of a different ethnicity had the weakest effect in countries such as Lithuania, Estonia, and Poland, which were the furthest away from the main migration routes during the refugee crisis. In contrast, welfare chauvinism is most strongly connected to ethnically different immigrants in countries that experienced a large influx of ethnically different immigrants, such as Hungary and Slovenia, or those that perceived a risk of this influx, such as the Czech Republic (Bartoszewicz & Eibl, Citation2022). These findings align with previous studies showing that the refugee crisis had a significant impact on attitudes and political debates in several Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries (Župarić-Iljić & Valenta, Citation2019; Bartoszewicz & Eibl, Citation2022; Hutter & Kriesi, Citation2022). However, it seems that the refugee crisis can only be partly linked to anti-immigrant sentiments in the most intolerant countries in CEE. This study reveals that the most exclusionary form of welfare chauvinism can be found in Hungary and the Czech Republic, and it’s important to note that there were already high levels of racist attitudes in both the Czech Republic and Hungary even before the refugee crisis (Bell et al., Citation2022).

We have also shown that welfare chauvinist attitudes can be found across the political spectrum. Yet, we again may find differences between the countries in our sample. While there is a relationship between more right-leaning individuals and welfare chauvinism in the Czech Republic, Hungary and Lithuania, we do not find this association in Estonia, Poland and Slovenia. Additionally, in both Hungary and Lithuania, individuals who believe that the government should reduce income differences, a belief which is often attributed towards more left-leaning individuals, are in fact more welfare chauvinistic. In fact, the belief that the government should reduce income differences only has the expected effect in one out of the six countries sampled. This result may indicate that these attitudes are not primarily connected to the more radical right voters, as has been the case in Western Europe (Careja & Harris, Citation2022). It seems rather that political parties across the political spectrum can use welfare chauvinistic rhetoric and policy to attract a broad segment of voters.

On more general note, our findings contribute to nuanced discussions on variations in Central and Eastern European attitudes towards immigrants’ entitlement to social benefits. Importantly, these findings also have relevance for social work in the region. The strong prevalence of welfare chauvinism in several countries in the CEE, and the fact that such attitudes may be found across the political spectrum, could lead to volatile changes in support for inclusion of specific deserving migrant groups. Our finding might even serve as a reminder of the underlying fragility of the welcoming attitudes in the region towards refugees from Ukraine. The war in Ukraine has resulted in the largest refugee crisis in Europe since WWII, with the Central and Eastern Europe countries being the primary recipients of Ukrainian refugees.Footnote17 These countries have granted Ukrainians a wide range of social rights and access to local labour markets. This study warns us that it is not out of the possibility that welcoming sentiments could decline, thereby also affecting the social rights of Ukrainian refugees in the region at large.Footnote18

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

David Andreas Bell

David Andreas Bell is associate professor at the Department of Social Work, Norwegian University of Science and Technology. His research interests are welfare chauvinism, social policy and ethnic prejudice.

Marko Valenta

Marko Valenta is professor at the Department of Social Work, Norwegian University of Science and Technology. His research interests are reception, integration and return of labour-migrants, asylum-seekers and refugees.

Notes

1 Though this has changed significantly following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine which has led to several of the CEE countries to receive the brunt of refugees from Ukraine. However, as the data that we use for this analysis is collected in 2016–2017 the immigrant populations were considerably lower at the time.

2 A similar study was conducted by Grdešić (Citation2020); however, we would argue that this study’s dependent variables, which asks whether ‘immigrants are a burden for the national social protection system’ and whether ‘immigrants make a valuable contribution to the national economy of our country’, as measures of economic threat rather than a welfare chauvinistic sentiment. These variables do not tap into the exclusion/restriction of immigrants from the social system, which is central to welfare chauvinism.

3 For example, Gorodzeisky et al. (Citation2015) found that in Russia, half the sample did not provide an answer to the question: ‘How would you place your views on the left–right political orientation scale’. Additionally, among those who did provide an answer, more than half placed themselves in the middle category of the scale.

4 Though this has changed significantly following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine which has led to several of the CEE countries to receive the brunt of refugees from Ukraine.

5 We use the eight wave of the ESS specifically because it has a the most up to date module covering welfare attitudes and therefore has a measure of welfare chauvinism.

6 Ideally, we would have included even more countries, such as Romania, Bulgaria, and Croatia; however, ESS only provides data for the abovementioned 6 countries. Russia could technically be a part of our analysis; however, as we are mainly interested in the attitudes found in EU countries, we decided to exclude Russia from our analysis.

7 See appendix A1 for distribution of the dependent variable.

8 By applying linear regression, we also don’t have to contend with the inherent limitations related to logistical regression and the difficulty of comparing odds ratios across models (Mood, Citation2010).

9 This highlights arguments challenging the universalism of concepts developed in the ‘West’ (Gorodzeisky & Leykin, Citation2022; Leykin & Gorodzeisky, Citation2023).

10 See appendix A2 for these models.

11 Although most of the countries in the sample have quite small immigrant populations from outside of Europe at the time of data collection, it seems that such distinctions may still be of relevance, considering how other studies have highlighted how there does not need to be a large ethnically different immigrant community for there to be strong hostility towards those groups (Bell et al., Citation2021). Włoch (Citation2009) for example argued that ‘Phantom Islamophobia’ was a prevalent phenomenon in Poland.

12 The highest VIF value was found in Lithuania with 2.00; the lowest was found in Hungary (1.49).

13 Lithuania was not sampled in 2008. We could therefore not compare the results from 2016 with 2008.

14 It should be emphasized that the differences in results compared to Leykin and Gorodzeisky (Citation2023) may stem from differences in methodological choices as we include both controls and anti-immigrant attitudes in our study. Also, this may highlight how general negative attitudes towards immigrants and welfare chauvinism are two separate phenomena as Gorodzeisky and Semyonov (Citation2009) proposed.

15 An additional point here is that the even further radical right party at the time, Jobbik, had more of a socialist social policy position (Lugosi, Citation2018).

16 However, what complicates this argument is that Estonia, a country with an even larger share of Russian minorities, does not have the same results. For more on this discussion, see Auers (Citation2018).

17 The large influx of Ukrainian refugees is significant with Poland being the largest receiver in nominal numbers, while the Czech Republic is the largest per capita receiver of Ukrainian refugees in the world. Countries in the CEE have been more supportive to Ukrainian refugees than to migrants and refugees from countries outside Europe (Dražanová & Geddes, Citation2023; Moise et al., Citation2023; Zogata-Kusz et al., Citation2023). Ukrainians have hitherto been perceived as deserving migrants, but they are exerting tremendous pressure on welfare services in the countries with widespread welfare chauvinist attitudes.

18 Recent surveys have already shown diminishing support towards Ukrainian refugees (CBOS, Citation2023).

References

- Abou-Chadi, T., & Krause, W. (2020). The causal effect of radical right success on mainstream parties’ policy positions: A regression discontinuity approach. British Journal of Political Science, 50(3), 829–847. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123418000029

- Andersen, J. G., & Bjørklund, T. (1990). Structural changes and new cleavages: The progress parties in Denmark and Norway. Acta Sociologica, 33(3), 195–217. https://doi.org/10.1177/000169939003300303

- Arzheimer, K. (2018). Explaining electoral support for the radical right (J. Rydgren, Ed.; Vol. 1). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190274559.013.8

- Aspelund, A., Lindeman, M., & Verkasalo, M. (2013). Political conservatism and left-right orientation in 28 Eastern and Western European countries: Conservatism and left-right. Political Psychology, 34(3), 409–417. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12000

- Auers, D. (2018). Populism and political party institutionalisation in the three Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Fudan Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences, 11(3), 341–355. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40647-018-0231-1

- Baldi, G., & Goodman, S. W. (2015). Migrants into members: Social rights, civic requirements, and citizenship in Western Europe. West European Politics, 38(6), 1152–1173. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2015.1041237

- Bartoszewicz, M. G., & Eibl, O. (2022). A rather wild imagination: Who is and who is not a migrant in the Czech media and society? Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 9(1), 230. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01240-2

- Bell, D. A., Strabac, Z., & Valenta, M. (2022). The importance of skin colour in central Eastern Europe. A comparative analysis of racist attitudes in Hungary, Poland and the Czech Republic. Central and Eastern European Migration Review, 11(1), 5–22.

- Bell, D. A., Valenta, M., & Strabac, Z. (2021). A comparative analysis of changes in anti-immigrant and anti-Muslim attitudes in Europe. Comparative Migration Studies, 9, 1–24.

- Bell, D. A., Valenta, M., & Strabac, Z. (2023a). Perceptions and realities: Explaining welfare chauvinism in Europe. Journal of European Social Policy, 33(3), 301–316.

- Bell, D. A., Valenta, M., & Strabac, Z. (2023b). Nordic welfare chauvinism: A comparative study of welfare chauvinism in Sweden, Norway and Finland. International Social Work, 66(6), 1786–1802.

- Bello, V. (2017). International migration and international security: Why prejudice is a global security threat. Routledge.

- Bessudnov, A. (2016). Ethnic hierarchy and public attitudes towards immigrants in Russia. European Sociological Review, 32(5), 567–580. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcw002

- Blumer, H. (1958). Race prejudice as a sense of group position. The Pacific Sociological Review, 1(1), 3–7. https://doi.org/10.2307/1388607

- Careja, R., & Harris, E. (2022). Thirty years of welfare chauvinism research: Findings and challenges. Journal of European Social Policy, 32(2), 212–224. https://doi.org/10.1177/09589287211068796

- CBOS. (2023). How should Poland support refugees from Ukraine. Retrieved August 23, 2023, from https://www.cbos.pl/EN/publications/news/2022/25/newsletter.php

- Cinpoeş, R., & Norocel, O. C. (2020). Nostalgic nationalism, welfare chauvinism, and migration anxieties in Central and Eastern Europe. In O. C. Norocel, A. Hellström, & M. B. Jørgensen (Eds.), Nostalgia and hope: Intersections between politics of culture, welfare, and migration in Europe (pp. 51–65). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-41694-2_4

- Deacon, B. (2000). Eastern European welfare states: The impact of the politics of globalization. Journal of European Social Policy, 10(2), 146–161. https://doi.org/10.1177/a012487

- De Haas, H., Castles, S., & Miller, M. J. (2022). The age of migration: International population movements in the modern world (6th ed., reprinted by Bloomsbury Academic). Bloomsbury Academic.

- Dražanová, L. (2022). Sometimes it is the little things: A meta-analysis of individual and contextual determinants of attitudes toward immigration (2009–2019). International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 87, 85–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2022.01.008

- Dražanová, L., & Geddes, A. (2023). Attitudes towards Ukrainian refugees and governmental responses in 8 European countries. In S. Carrera & M. Ineli-Ciger (Eds.), Eu responses to the large-scale refugee displacement from Ukraine: An analysis on the temporary protection directive and Its implications for the future EU asylum policy. European University Institute (EUI).

- Eger, M. A., & Breznau, N. (2017). Immigration and the welfare state: A cross-regional analysis of European welfare attitudes. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 58(5), 440–463. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020715217690796

- Eger, M. A., & Valdez, S. (2015). Neo-nationalism in Western Europe. European Sociological Review, 31(1), 115–130. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcu087

- Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Polity Press.

- Eugster, B. (2018). Immigrants and poverty, and conditionality of immigrants’ social rights. Journal of European Social Policy, 28(5), 452–470. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928717753580

- Fenger, H. J. M. (2007). Welfare regimes in Central and Eastern Europe: Incorporating post-communist countries in a welfare regime typology. Contemporary Issues and Ideas in Social Sciences, 3(2), 1–30.

- Field, R. S., Chung, D., & Fleay, C. (2021). Working with restrictions: A scoping review of social work and human service practice with people seeking asylum in the Global North. The British Journal of Social Work, 51(1), 57–76. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcaa006

- Ford, R. (2016). Who should we help? An experimental test of discrimination in the British welfare state. Political Studies, 64(3), 630–650. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.12194

- Goerres, A., Spies, D. C., & Kumlin, S. (2018). The electoral supporter base of the alternative for Germany. Swiss Political Science Review, 24(3), 246–269. https://doi.org/10.1111/spsr.12306

- Gorodzeisky, A. (2013). Does the type of rights matter? Comparison of attitudes toward the allocation of political versus social rights to labour migrants in Israel. European Sociological Review, 29(3), 630–641. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcs013

- Gorodzeisky, A. (2021). Public opinion toward asylum seekers in post-communist Europe: A comparative perspective. Problems of Post-Communism, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/10758216.2021.1987267

- Gorodzeisky, A., Glikman, A., & Maskileyson, D. (2015). The nature of anti-immigrant sentiment in post-socialist Russia. Post-Soviet Affairs, 31(2), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/1060586X.2014.918452

- Gorodzeisky, A., & Leykin, I. (2020). When borders migrate: Reconstructing the category of ‘international migrant’. Sociology, 54(1), 142–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038519860403

- Gorodzeisky, A., & Leykin, I. (2022). On the West–East methodological bias in measuring international migration. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 48(13), 3160–3183. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2021.1873116

- Gorodzeisky, A., & Semyonov, M. (2009). Terms of exclusion: Public views towards admission and allocation of rights to immigrants in European countries. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 32(3), 401–423. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870802245851

- Gorodzeisky, A., & Semyonov, M. (2009). Terms of exclusion: Public views towards admission and allocation of rights to immigrants in European countries. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 32(3), 401–423.

- Grdešić, M. (2019). Neoliberalism and welfare chauvinism in Germany. German Politics and Society, 37(2), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.3167/gps.2019.370201

- Grdešić, M. (2020). The Strange case of welfare chauvinism in Eastern Europe. Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 53(3), 107–122. https://doi.org/10.1525/cpcs.2020.53.3.107

- Greve, B. (2020). Myths, narratives and welfare states: The impact of stories on welfare state development. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Heizmann, B., Jedinger, A., & Perry, A. (2018). Welfare chauvinism, economic insecurity and the asylum seeker “crisis”. Societies, 8(3), 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc8030083

- Hjorth, F. (2016). Who benefits? Welfare chauvinism and national stereotypes. European Union Politics, 17(1), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116515607371

- Hutter, S., & Kriesi, H. (2022). Politicising immigration in times of crisis. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 48(2), 341–365. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1853902

- Jylhä, K. M., Rydgren, J., & Strimling, P. (2019). Radical right-wing voters from right and left: Comparing Sweden Democrat voters who previously voted for the Conservative Party or the Social Democratic Party. Scandinavian Political Studies, 42(3-4), 220–244. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9477.12147

- Keskinen, S., Norocel, O. C., & Jørgensen, M. B. (2016). The politics and policies of welfare chauvinism under the economic crisis. Critical Social Policy, 36(3), 321–329. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261018315624168

- Kitschelt, H., & McGann, A. J. (1995). The radical right in Western Europe: A comparative analysis. The University Press of Michigan.

- Koning, E. A. (2022). Welfare chauvinist or neoliberal opposition to immigrant welfare? The importance of measurement in the study of welfare chauvinism. In M. M. L. Crepaz (Ed.), Handbook on migration and welfare (pp. 156–174). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Kros, M., & Coenders, M. (2019). Explaining differences in welfare chauvinism between and within individuals over time: The role of subjective and objective economic risk, economic egalitarianism, and ethnic threat. European Sociological Review, 35(6), 860–873. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcz034

- Lancaster, C. M. (2022). Immigration and the sociocultural divide in central and Eastern Europe: Stasis or evolution? European Journal of Political Research, 61(2), 544–565. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12474

- Leruth, B., & Taylor-Gooby, P. (2021). The United Kingdom before and after Brexit. In B. Greve (Ed.), Handbook on austerity, populism and the welfare state (pp. 170–185). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Leykin, I., & Gorodzeisky, A. (2023). Is anti-immigrant sentiment owned by the political right? Sociology, 58. https://doi.org/10.1177/00380385231161206

- Lugosi, N. V. (2018). Radical right framing of social policy in Hungary: Between nationalism and populism. Journal of International and Comparative Social Policy, 34(3), 210–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/21699763.2018.1483256

- Magni, G. (2021). Economic inequality, immigrants and selective solidarity: From perceived lack of opportunity to in-group favoritism. British Journal of Political Science, 51(4), 1357–1380. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123420000046

- Mazurkiewicz, A. (Ed.). (2019). East central European migrations during the cold War: A handbook. De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110610635

- Minderhoud, P. E. (1999). Asylum seekers and access to social security: Recent developments in The Netherlands, United Kingdom, Germany and Belgium. In A. Bloch & C. Levy (Eds.), Refugees, citizenship and social policy in Europe (pp. 132–148). Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230371248_7

- Moise, A. D. (2020). Researching the welfare impact of populist radical right parties comment on “A scoping review of populist radical right parties’ influence on welfare policy and its implications for population health in Europe”. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 1. https://doi.org/10.34172/ijhpm.2020.125

- Moise, A. D., Dennison, J., & Kriesi, H. (2023). European attitudes to refugees after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. West European Politics, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2023.2229688

- Mood, C. (2010). Logistic regression: Why we cannot do what we think we can do, and what we can do about it. European sociological review, 26(1), 67–82.

- Ramet, S., & Valenta, P. (2016). Ethnic Minorities and Politics in Post-Socialist Southeastern Europe. Cambridge University Press.

- Rinaldi, C., & Bekker, M. P. M. (2020). A scoping review of populist radical right parties’ influence on welfare policy and its implications for population health in Europe. International Journal of Health Policy and Management, 1. https://doi.org/10.34172/ijhpm.2020.48

- Robinson, K. (2014). Voices from the front line: Social work with refugees and asylum seekers in Australia and the UK. British Journal of Social Work, 44(6), 1602–1620. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bct040

- Rydgren, J. (2008). Immigration sceptics, xenophobes or racists? Radical right-wing voting in six West European countries. European Journal of Political Research, 47(6), 737–765. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2008.00784.x

- Savage, L. (2023). Preferences for redistribution, welfare chauvinism, and radical right party support in Central and Eastern Europe. East European Politics and Societies: And Cultures, 37(2), 584–607. https://doi.org/10.1177/08883254221079797

- Saxonberg, S., & Sirovátka, T. (2018). Central and Eastern Europe. In B. Greve (Ed.), Routledge handbook of the welfare state (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Schumacher, G., & Van Kersbergen, K. (2016). Do mainstream parties adapt to the welfare chauvinism of populist parties? Party Politics, 22(3), 300–312. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068814549345

- Stephan, W. G., Ybarra, O., & Morrison, K. R. (2016). Intergroup threat theory. In T. D. Nelson (Ed.), Handbook of prejudice, stereotyping, and discrimination: Vol. 2 (pp. 255–278). Psychology Press.

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behaviour. In J. T. Jost & J. Sidanius (Eds.), Political psychology: Key readings (pp. 33–37). Psychology Press.

- United Nations. (2020). International Migrant Stock. Downloaded from https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/content/international-migrant-stock.

- Vala, J., & Pereira, C. R. (2018). Racisms and normative pressures: A new outbreak of biological racism? In M. C. Lobo, F. C. da Silva, & J. P. Zúquete (Eds.), Changing societies: Legacies and challenges. Citizenship in crisis. (Vol. 2, pp. 217–248). ICS.

- Valenta, M., & Berg, B. (2010). User involvement and empowerment among asylum seekers in Norwegian reception centres. European Journal of Social Work, 13(4), 483–501. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13691451003603406

- Valenta, M., & Strabac, Z. (2011). State-assisted integration, but not for all: Norwegian welfare services and labour migration from the new EU member states. International Social Work, 54(5), 663–680. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0020872810392811

- Valenta, M., & Thorshaug, K. (2013). Restrictions on Right to Work for Asylum Seekers: The Case of the Scandinavian Countries, Great Britain and the Netherlands. International Journal on Minority and Group Rights, 20(3), 459–482.

- Whitefield, S. (2002). Political cleavages and post-communist Politics. Annual Review of Political Science, 5(1), 181–200. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.5.112601.144242

- Włoch, R. (2009). Islam in Poland: between ethnicity and universal umma. International Journal of Sociology, 39(3), 58–67.

- Wojcik, A. D., Cislak, A., & Schmidt, P. (2021). ‘The left is right’: Left and right political orientation across Eastern and Western Europe. The Social Science Journal, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/03623319.2021.1986320

- Zogata-Kusz, A., Öbrink Hobzová, M., & Cekiera, R. (2023). Deserving of assistance: The social construction of Ukrainian refugees. Ethnopolitics, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449057.2023.2286779

- Župarić-Iljić, D. & Valenta, M. (2019). “Refugee Crisis” in the Southeastern European Countries: The rise and fall of the Balkan Corridor. In C. Menjívar, M. Ruiz & I. Ness (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of migration crises, Oxford handbooks (pp. 366–388). https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190856908.013.29