?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Pandemics refract sociopolitical tensions within societies and highlight how national belonging hinges on informal performances as much as legal status. While return migration has become a common practice and institutionalized strategy of state development, little scholarly work has probed how domestic populations view returnees and their claims to national membership. Using a large-scale, pre-registered online survey experiment deploying a give-or-take Dictator Game, this paper leverages the dynamics of COVID-19 to explore how Chinese nationals envision and treat returnees. First, our results illustrate that the Chinese population imagines returnees as a group of elites with substantial social and financial capital, even though returnees are a socio-economically diverse population. Next, by applying information priming, we demonstrate that Chinese nationals discriminated against overseas returnees during the pandemic and that this behavior was not primarily driven by fears of viral contagion. Finally, using mediation analysis, we show that participants’ differential behavior towards returnees can largely be explained by participants’ perceptions of returnees’ class status and adherence to key markers of national membership. Ultimately, this paper broadens our understanding of the informal dynamics of national membership and intergroup relations.

Introduction

As COVID-19 gripped the world and paused global flows of goods, services, and people, some Chinese citizens abroad began the arduous journey home. They faced not only prejudice overseas, but also China’s grueling controls as they returned (Liu and Peng Citation2023). China’s ‘Five One’ policy allowed foreign carriers to operate only one weekly flight into China from March 2020 through the summer of 2022. Consequently, flights were scant and economy tickets were selling for over USD5000 each way.Footnote1 Once returnees arrived in China, many of them faced a mandatory, self-funded 14-day hotel quarantine with repeated PCR testing prior to being able to rejoin society.Footnote2

Yet, following these travails, returnees were not always welcomed by their fellow citizens. Many found themselves targets of commentary characterizing them not only as vectors of disease but as outsiders at best, traitors at worst. Microblogging and messaging apps like Weibo and WeChat were abuzz with nationalist criticisms such as,

‘Now many news reports tell people how dangerous it is abroad, how safe it is at home, so many people want to come seek refuge … . ; … many news reports tell … , how domestically nourished students studying abroad express such traitorous speech, how some wealthy people at home worship foreign things and fawn on foreign powers; in order to perpetuate the excellent qualities of the Chinese nation, [and] eliminate the scum of the Chinese nation […], the next step is whether we should […] eliminate the traitors and foreigners, especially the sanctimonious ‘banana people.’’Footnote3

What is most striking about Chinese citizens’Footnote5 nationalist denunciations is that they are directed at full legal members of the nation. The politics of national belonging always involve both formal and informal components; yet because the targets of Chinese nationalistic ire are also Chinese citizens and co-ethnics, we cannot rely strictly on theoretical frameworks that examine how immigration or majority/minority ethnic tensions inform a domestic population’s understanding of who belongs (Flores and Azar Citation2023; Hainmuller and Hiscox Citation2010; Legewie Citation2013; Wimmer Citation2017). The roots and scope of the Chinese domestic population’s discriminatory attitudes toward returnees thus constitute a puzzle to be explained.

In this paper, we leverage an original behavioral experiment to investigate whether Chinese citizens who remained in China during the pandemic discriminate against returnees. We interrogate how Chinese citizens imagine and treat returnees through a give-or-take Dictator Game (DG). Participants in our DG allocate tokens that they can exchange for real-world money when they conclude the experiment instead of answering attitudinal questions with no stakes (we elaborate on this in the ‘Data and methods’ section). Therefore, the amount participants allocate to themselves versus a returnee or non-returnee reveals not just prejudicial affect, but discriminatory actions. Such behavioral games offer several advantages. First, in contrast to attitudinal measures, behavioral games reduce social desirability bias. Second, they uncover prosocial behavior in the experiment that, crucially, correlates with real-world actions.Footnote6

We make the following contributions in this study. Using a real-stakes decision-making setting, we document discrimination against Chinese returnees compared to non-returnees. Furthermore, building on the growing literature emphasizing how participants’ perceptions of their paired partners in behavioral games impact outcomes, we use mediation analysis to probe why this discrimination happens. In so doing, we advance sociological understandings of how class resentment and contested contours of national belonging shape discrimination against returnees during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In what follows, we first discuss two mechanisms that could give rise to unequal treatment of returnees compared to non-returnees: national belonging and class resentment. We then situate our study in the Chinese context. We briefly outline our hypotheses, present our data and methods, and discuss our findings. We close by discussing limitations and then conclude.

National belonging and class resentment

Citizenship serves as a key marker of formal inclusion (Brubaker Citation1992). It is always multi-valent in nature, however, capturing not only legal claims of inclusion, but also ‘the quality of the relationship between individual members and the larger community to which they belong’ (Goldman and Perry Citation2002, 2). We are interested in this more informal form of national membership administered by ‘ordinary people in the course of everyday life, using tacit understandings of who belongs and who does not, of us and them’ (Brubaker Citation2010, 65).

National belonging is also more than legal status; it is performatively enacted through quotidian interactions, hinging on recognition from fellow citizens as much as the state (Bonikowski Citation2016; Su Citation2022). Adhering to quarantine guidelines and supporting government safety protocols during a pandemic, for example, may be understood as performing one’s citizenship duties and proving one’s nationalist credentials, rather than just a means of mitigating viral risk (Binah-Pollak and Yuan Citation2022; Jia and Luo Citation2023). This may be particularly true in countries that prioritize collectivism as a key component of citizenship, rule through campaign-style governance, and thus expect individuals to ‘prioritize the national over the personal’ during times of struggle (Guo Citation2021; Rithmire and Han Citation2020).

Recognition of national membership can be precarious and contingent, fluctuating with context and audience (Ho Citation2016). Subjective indicators of national belonging are easily questioned, while events sparking bursts of nationalist sentiment – like the COVID-19 pandemic – can shuffle who social actors perceive as full members of the nation (Elias et al. Citation2021; Wang and Tao Citation2021). Consequently, for individuals who cross borders, recognized membership is ‘a precarious, arduous, and revocable political achievement’ that may have to be repeatedly re-affirmed (Kim Citation2016, 10; Brubaker et al. Citation2006).

Although returnees often possess national membership through both formal citizenship and cultural heritage, this claim is not always recognized by domestic audiences (Ho Citation2019; Liu Citation2021). Their experiences consequently reveal how populations draw boundaries around national belonging. Few studies, however, have systematically examined how non-migrants view their returnee peers. Seol and Skrentny (Citation2009) and Zhang (Citation2019), for example, have explored how returnees’ sense of identity and belonging are informed by tensions with co-ethnic non-migrants. Singer and Quek (Citation2022) examine Chinese public opinion regarding internal migrants and foreign immigrants of different skill levels, but do not address returnees, who fill an intermediary space between the foreign and internal migration dichotomy (Ren and Liu Citation2019). Moreover, research that does examine the Chinese public’s perceptions of returnees does not concern itself with issues of national belonging (Tai and Truex Citation2015). We interrogate perceptions of returnees, offering a lever with which to unpack the contours of national belonging, both for returnees themselves and the society to which they return. For the purpose of this study, we define returnees as Chinese citizens returning to mainland China during the pandemic after an unspecified period abroad.

How non-migrant compatriots treat returnees may also depend on perceptions of class. On average, individuals who cross borders are selective in terms of wealth, education, and health compared to those who do not (Feliciano Citation2020). For highly skilled migrants in particular, returning is often a conscious choice motivated by personal ambition, a sense of strategic opportunity, and ample resources offered to them in their native countries (Paul Citation2021). Non-migrants may thus resent returnees for material rather than ideological reasons.

China’s socioeconomic changes over the past forty years have created conditions in which returnees may be viewed – and resented – based on perceptions of class. Since the initiation of the market reforms, China has undergone a historically unparalleled transformation characterized by both rising GDP per capita and economic inequality (Kanbur, Wang, and Zhang Citation2021; Yang, Novokmet, and Milanovic Citation2021). Although Chinese society seems to tolerate merit-based disparities (Wu Citation2009), discourse regarding ‘wealth hatred’ has increased in recent years, particularly as individuals with inherited wealth have come of age (Zang Citation2008). The tastes of the wealthy in China have been shown to align with the Western-oriented global elite rather than their domestic counterparts (Li Citation2021), leading them to ‘opt out’ of the Chinese marketplace (Hanser and Li Citation2015). In particular, the upper- and upper-middle classes have taken to leveraging their economic resources to send their children abroad for educational pursuits as a means of strategically avoiding China’s high-stress, memorization-based system (Tu Citation2021). Even as Chinese students studying abroad have become more economically diverse (Ma Citation2020), most come from relatively wealthy families (Lo, Li, and Tan Citation2023). This, in turn, has led to narratives in China characterizing those who study abroad as spoiled, incapable of excelling in China, less prepared for the local job market, and thus unworthy of the status and economic advantages they receive.

Importantly, class-based resentment is not entirely independent from notions of national belonging (Bonikowski Citation2017). Variants of nationalism and populism interweaving ethnonationalist beliefs with anti-elite sentiment are on the rise globally, including in China (Bonikowski and Zhang Citation2023; Brubaker Citation2020; Zhang Citation2020). In a study on Korean international students, for instance, Park (Citation2020) uses the conjoint phrase, ‘class and nationalist resentment,’ emphasizing that what is resented is not only class privilege, but also the Global North’s hegemony over Korea in terms of skill and knowledge. COVID-19 seems to have tightened this link (Bieber Citation2022). Throughout the pandemic, for instance, Chinese netizens’ critiques of returning students often combined anger about economic privilege and mobility with accusations of traitorous behavior and betrayal of the nation (Binah-Pollak and Yuan Citation2022).

We therefore consider how nationalism and class resentment may inform attitudes toward returnees. The immigration literature suggests that wealthy, highly skilled immigrants are more likely to be welcomed in most countries compared to working class populations with lower levels of skills and education (Hainmueller, Hopkins, and Yamamoto Citation2014). However, we have reason to assume that the same class dynamics observed regarding immigrants do not apply to Chinese returnees. The Chinese case therefore enables us to probe how non-migrants understand the place of presumed upper-class, co-ethnic returnees. This question is of particular significance in light of rising populist sentiment in China and across the globe, which entangles anti-elite attitudes with notions of national belonging (Brubaker Citation2020; Miao Citation2020). Furthermore, in contrast to immigrants, returnees are legally and culturally members of the nation. We thus focus on how this membership is contested and emphasize the potential role of class resentment, rather than processes of migration and acculturation. Ultimately, unpacking how non-returnees imagine and why they treat returnees in particular ways represents an essential component of understanding the construction of national identity and class-based fault-lines.

Return migration in the Chinese context

China during the COVID-19 pandemic offers analytical leverage for understanding how domestic populations perceive and treat returning migrants for four reasons. First, return migration to China is large in scale and highly institutionalized. While the Chinese state has long adopted an extraterritorial, ethno-nationalist imaginary of national belonging that construes all who are ethnically Chinese as members of the nation with patriotic obligations (Ho Citation2019), in recent years the Chinese government has re-envisioned its diaspora as a developmental resource and attempted to turn brain drain into brain circulation (Saxenian Citation2005). Since the market reforms, the Chinese government has constructed an immense institutional infrastructure to engage, entice, and manage its diasporic population, repeatedly extolling returnees’ contributions to China’s society, economy, and technological advancement (Liu Citation2022; Miao et al. Citation2022; Ren and Liu Citation2019). Programs such as the Thousand Talents Plan (Liu and van Dongen Citation2016; Zhang Citation2019) place returnees on a career track with privileges distinct from those enjoyed by their domestic peers (Miao et al. Citation2022). This strategy has both spurred a rapid increase in highly skilled return migration integral to China’s development (Zhou and Coplin Citation2022) and fueled entrepreneurship among returnees (Wang Citation2016). From 1978 to 2018, over 3.6 million students and scholars have returned to China from abroad,Footnote7 while more recent years have seen over a million returnees annually.Footnote8 Given the pervasive discourse around returnees, non-returnee members of the Chinese public are likely to have well-developed opinions about returnees, their contributions, and their claims of national membership – even without significant interactions with returnees.

Second, China’s demographics and citizenship laws enable us to examine how domestic populations perceive the contours of national belonging with fewer concerns about confounders like race and nativity. Returnees may be assumed to be co-ethnics of their domestic peers because of the racial and ethnic composition of the Chinese society. Moreover, the Chinese government does not recognize dual citizenship and increasingly enforces this law among returnees (Liu Citation2021), while naturalization is empirically close to impossible. Consequently, non-migrants likely imagine returnees as co-ethnics, especially when returnees are identified to be legal members of the nation.

Chinese returnees’ national belonging remains contested, however. While state media narratives imbue returnees’ actions with a patriotic sheen, recent research suggests that returnees rarely espouse nationalist ideas themselves (Zhang Citation2019). Even as returnees are claimed as co-ethnics with obligations to strengthen the nation, they are also perennially tainted by the hybridity of their identities and ascribed with alterity (Ho Citation2019). Their Chinese-ness, political allegiance, and long-term commitment to China are frequently called into question through both their own quotidian interactions and the broader media discourse.

Third, the dynamics of return migration in contemporary China enable us to examine how returnees’ perceived class shapes their reception at home. The full population of China’s returnees is socio-economically diverse, consisting not only of returning students and highly skilled, wealthy workers, but also of manual laborers sent abroad in state-directed projects like the Belt and Road Initiative (Lee Citation2017). The press surrounding returnees’ contributions to China’s development, however, has solidified the Chinese public’s imaginary of returnees as privileged (Teo Citation2011). Survey experiments as far back as 2012, for instance, demonstrate that while Chinese citizens appreciate returnees’ contributions to the economy and the academy, they resent the sizeable economic benefits conferred on them (Tai and Truex Citation2015).

Fourth, aspects of the Chinese government’s COVID-19 response potentially crystalized longstanding tensions around returnees, making the pandemic an ideal time to probe the domestic population’s perception of returnees. As much as they are biological events, pandemics are also sociopolitical dramas that heighten existing social strains and render longstanding biases expressible (Rosenberg Citation1989). After failing during the initial Wuhan outbreak of 2020, the Chinese government transformed its control over – and narrative of – the pandemic (Zhang Citation2022). Building on a long history of ‘patriotic health campaigns’ (Perry Citation2021; Rogaski Citation2004), the government began stoking nationalism and characterizing the virus – and anyone bringing it into China’s borders – as a foreign invader against whom all citizens must maintain constant vigilance (Zhang Citation2021). Highlighting China’s comparatively effective containment of the virus, the state enacted strict mitigation measures and turned them into ritualistic generators of ‘national allegiance, resilience, and glory’ (Liu Citation2020, 486). Support for the government’s pandemic policies and willingness to adopt preventative measures thus came to positively correlate with nationalist convictions in China well into the late stage of the pandemic (Jia and Luo Citation2023), while those flouting these policies were characterized as national traitors.

Similarly, the Chinese government’s ‘Five-One’ Policy and quarantine regulations caused the financial cost and logistical hurdles of returning to skyrocket. Thus, while Chinese returnees are socioeconomically diverse, those returning during COVID tended to be well off (Liu and Peng Citation2023). This economic reality, in turn, reinforced domestic imaginaries of returnees as wealthy, privileged, and potentially selfish. Ultimately, while nationalism and xenophobia were on the rise in China prior to the onset of COVID-19 (Chen-Weiss Citation2019), pandemic-specific dynamics reified lingering biases against returnees, interwove them with notions of national belonging, and rendered these biases socially acceptable to articulate (Binah-Pollak and Yuan Citation2022; Yu Citation2021).

Hypotheses

To investigate whether Chinese citizens who remained in China during the pandemic discriminate against returning Chinese, we collected data from a behavioral experiment during the fall of 2021. We test five hypotheses (two confirmatory, three exploratory) regarding how returnees were treated and the potential drivers of this behavior. Given recent interview-based research on the ‘double exclusion’ that Chinese international students experienced in both their host and sending countries (Hu, Xu, and Tu Citation2022), we hypothesize, following the pre-registration, thatFootnote9:

H1: Overseas Chinese returnees are treated worse compared to non-returnees.

To test whether participants’ fear of contagion motivated their discriminatory behavior, we present randomly selected participants with information regarding the low probability of a returnee carrying the SARS-CoV-2 virus and the high cost of returning to China. We expect a reduction in differential treatment towards returnees if imperfect information about the public health risks returnees pose contributes to discriminatory behavior. Based on the pre-registration, we hypothesize:

H2: Overseas Chinese returnees are treated worse when no additional information is available about the overseas return process and quarantine procedures.

H3: Overseas Chinese returnees are treated worse when they are perceived as having not engaged in key performances of national membership.

H4: Overseas Chinese returnees are treated worse when they are perceived to be from an upper class background.

H5: Participants who self-identify as less cosmopolitan will treat overseas Chinese returnees worse.

Data and methods

The give-or-take Dictator Game

Investigations of intergroup relations have increasingly relied on incentivized behavioral games to measure group preference and unequal treatment (Abascal, Makovi, and Xu Citation2023; Baldassarri and Abascal Citation2017). Following this line of work, we implemented a give-or-take Dictator Game (DG) in our survey experiment to investigate whether – and why – everyday Chinese people treat returnees differently compared to non-returnees (Bardsley Citation2008). In the DG, participants are paired with a partner and are told that both parties receive an equal amount of resources to be exchanged for real-world money at the end of the survey. In this case, each participant receives 10 tokens equivalent to RMB 5, or USD 0.8.

All participants are led to believe that they were assigned to the role of the allocator or dictator, the only actor who makes decisions in the game, and their partner, or the recipient, is also a study participant. The dictator may give some of their resources to the recipient, do nothing, or take some of the resources from their partner. Such behavioral measures mitigate social desirability bias that attitudinal questions suffer from (we discuss this issue further in the Supporting Information (SI)). The structure of the game provides allocators with no incentives to contribute and an incentive to take all their partners’ resources. Consequently, dictators’ contributions are often interpreted as an indicator of prosociality (Baldassarri and Grossman Citation2013) and have been shown to strongly positively correlate with real-world prosocial behavior (Benz and Meier Citation2008; Franzen and Pointner Citation2013), demonstrating the measure’s external validity.

A growing body of research reveals that the attributes participants ascribe to their interaction partners affect game outcomes (Gereke, Schaub, and Baldassarri Citation2021; Glaeser et al. Citation2000). We thus collect participants’ perceptions of their partners’ characteristics to investigate potential mechanisms driving differential treatment using mediation analysis (Imai, Keele, and Tingley Citation2010; Makovi and Winship Citation2021), which we treat as exploratory.

Experimental design and implementation

In line with study protocols approved by the NYU Abu Dhabi Institutional Review Board (#HRPP-2021-112), participants in our study were randomly paired with a fictional partner. Half the participants were told that they were paired with someone who returned during the pandemic and was residing in China with Chinese legal citizenship, while the other half were told that their partner was a Chinese legal citizen who lived in China during the pandemic. Then, participants were asked to make decisions in the DG using a slider with values ranging from -10 (donating all tokens) to 10 (taking away all tokens).

We used information priming to investigate whether increased awareness of China’s strict quarantine measures would affect participants’ treatment of their partners. Half of the participants were randomly assigned to receive information about the viral mitigation protocols for those entering China before they made decisions in the DG. Consequently, our experiment follows a two-by-two design: half of the participants received the information prime (primed group) and the other half did not (non-primed group); within these groups, half were paired with an overseas Chinese returnee, and the other half with a non-returnee. We used mandatory comprehension checks to ensure participants read and understood both the overseas return experience information and the rules of the give-or-take DG.

We created the survey instrument on Credamo, a Chinese online survey platform. We recruited 2,697 individuals from their Data Market to participate in the study, which took place November 11–15, 2021. Only one response from any given IP address was permitted to ensure that participants were exposed to one experimental condition. To enhance our data quality, we employed approval rating and survey experience filters (additional details about data collection are in the SI). Eligible participants included those who (1) were over 18 years old; (2) reported their current location as ‘in China;’ (3) reported their location from January 2020 to November 2021 as ‘in China;’ and (4) reported being Chinese legal citizens. These criteria ensured the participants were Chinese citizens and had remained in China throughout the pandemic. We also inquired about whether participants were returnees themselves before the pandemic: only 5.8% reported that they have spent a year or more overseas.

Key measures

The DG decision is our dependent variable, which we operationalize as a continuous measure. After participants made their decision in the DG, we asked them about the characteristics they ascribed to their partner. These included their partner’s (1) perceived educational attainment (high school; bachelor’s; master’s or above); (2) financial status in China (top 1%, top 10%, top 30%, about average, bottom 30%, bottom 10%, bottom 1%); (3) level of support for China’s return flight policy during the pandemic (five-level Likert scale of agreement); and (4) likelihood of donation to China’s pandemic efforts (five-level Likert scale of agreement). These measures are our key mediators.

We also inquired about participants’ cosmopolitan identity by measuring their self-reported closeness to the ‘world’ (five-level Likert scale ranging from ‘very far’ to ‘very close’), modeled after a question in the World Values Survey.Footnote11 Participants who chose not to respond to this question were dropped from analyses that rely on self-reported cosmopolitan identity (0.3% of the sample). Cosmopolitan identity is our key moderator.

We measured a series of participant-level characteristics, both to minimize the impact of potentially failed randomization and to account for the fact that beliefs about participants’ partners are not randomly assigned. Controls include gender identification (male, not male), educational attainment (elementary school or less, … doctorate/doctorate in progress), age (18–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, 65 and above), monthly family income (1000RMB or less, … 100,000RMB or above), Chinese Communist Party (CCP) membership (never a member, currently a member, not a member now but once was), household registration (Hukou) type (agricultural, urban (non-agricultural), other), and residency in one of China’s four first-tier cities: Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen. We also controlled for whether participants had joined in a mass testing event within one month of taking the survey to account for varied pandemic experiences. Those participants answering ‘I prefer not to say’ to any of the control variable questions were dropped from analyses relying on these questions.

Analytical strategy

To assess the effect of being paired with an overseas returnee versus a non-returnee (H1), we examine differences in participants’ average contributions in the full sample, the primed group, and the non-primed group.

(1)

(1) where DG is the outcome in the DG; Partner, the main independent variable, is 1 if the participant was randomly paired with a returnee, and 0 otherwise; β1 is the estimate of interest, revealing the difference in contribution to returnees versus non-returnees.

In order to test whether a lack of knowledge about China’s strict quarantine procedures drove participants’ treatment of returnees and examine H2, we conduct two analyses. First, we compare β1 in Equation 1 of the primed group and the non-primed group. If these two estimates can be distinguished statistically, imperfect knowledge about the return process and fears of contagion risk may partially account for the unequal treatment of returnees. Otherwise, we may conclude there is no evidence supporting imperfect knowledge as a main driver behind the observed discrimination. Second, we examine the difference in average contribution between participants who were paired with a returnee across the primed and non-primed groups.

(2)

(2) where DG is the outcome of the DG; Priming is 1 if the participant received the information prime and 0 otherwise; β1 is the estimate of the average treatment effect of the information prime.

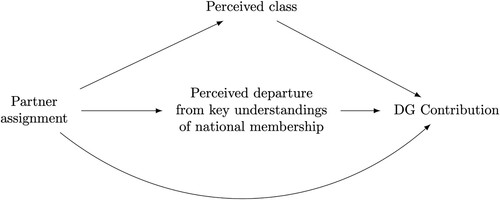

To disentangle the mechanisms that may be driving participants’ observed discriminatory behavior towards returnees, we carry out multiple mediation analyses based on in the full sample. Our mediator model considers the effect of being paired with an overseas returnee on the mediators of interest: perceived departure from key understanding of national membership (see H3) and perceived class (see H4). The outcome model focuses on the effect of the mediators on the DG decision while controlling for partner assignment. Since we randomly assign partners, the treatment-outcome and the treatment-mediator relationships are unlikely to be confounded by participant characteristics, and we include all controls in the mediator and outcome models. For estimation, we adopt the approach detailed in Jérolon et al. (Citation2021).Footnote12

Figure 1. DAG representing the effect of being paired with an overseas returnee on DG contribution mediated by the participants’ perceptions of the paired partner.

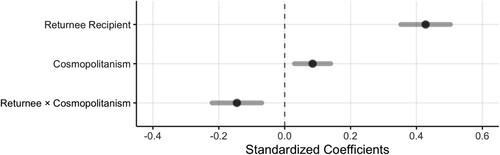

We then investigate the moderating effect of cosmopolitan identity on participants’ unequal treatment (see H5) of returnees with the following model:

(3)

(3) where β3 is the estimate of interest showing changes in the relationship between being paired with a returnee and the DG outcome as moderated by participants’ cosmopolitan identity, and Xn is a vector of participant-level controls.

Results

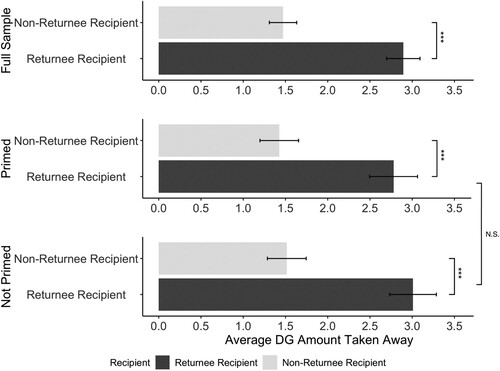

We first examine whether overseas Chinese citizens who returned to China during the pandemic were treated worse than non-returnees (H1). presents the average amount taken away from partners, broken down by the partner’s returnee status in the full sample, the primed group, and the non-primed group, respectively. Overall, returnees receive 1.42 fewer tokens than non-returnees, and the difference is statistically significant (p < 0.001, two-sided). These findings support our hypothesis that participants are less generous to overseas Chinese who returned amid the pandemic than to non-returnees. Ancillary analysis shows that the findings are stable after adjusting for a series of participant-level controls (Table S2).

Figure 2. Average amount taken away in the give-or-take DG by the recipient’s international return experience during the pandemic.

Note: The results correspond to SI Table S2. Error bars denote 95% confidence intervals. *** indicates statistically significant differences in contribution (p < 0.001), while N.S. signals non-significance. Positive averages indicate the participants took away the specified amount from the paired players.

Next, we discuss the effect of information priming on DG contribution (H2). Although the effect of being paired with a returnee in the primed group is smaller than that of the non-primed group by 0.14 tokens, the difference is not statistically significant (z = 0.546). This suggests that unfamiliarity with what return migration entailed (i.e., ‘statistical discrimination’) might not have been the primary mechanism driving unequal treatment in this context. It also suggests that participants’ discriminatory behavior was unlikely to have been motivated by their fear of contagion. Within the group paired with returnees, the average treatment effect of the information prime on DG contributions is not statistically significant either (p = 0.252, two-sided, Table S3). These findings bolster our interpretation that simply highlighting information about the strict COVID-19 protocols to which returnees must adhere does not decrease differential treatment. Taken together, we find no support for H2.

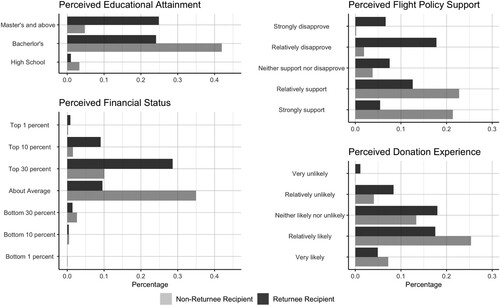

To understand the observed discrimination against those who returned, we consider participants’ perceptions of their partners’ support for national policies (H3) and class status (H4). We start by describing participants’ perceptions of their partners in . Participants perceived returnee partners, compared to non-returnee partners, as less likely to have donated to China’s pandemic efforts and having lower levels of support for China’s flight restriction policies. Participants also perceive returnees to be economically privileged and well-educated. These observations suggest that participants, on average, perceive Chinese returnees to have had particular migration experiences and high socio-economic status (see also Table S4 and Figure S4). Based on these descriptives, returnees may be treated unequally because of participants’ perception that returnees’ adherence to key performances of national membership differs from those of non-returnees, as well as class resentment.

Figure 3. Distributions of perceived characteristics of recipients by their international return experience during the pandemic.

Note: Four relevant items collected in the survey measured participants’ perceptions of their partners and were treated as mediators of differential treatment: educational attainment (left panel, top), financial status (left panel, bottom), levels of support towards China’s flight restriction policy (right panel, top), and likelihood of having donated to China’s anti-COVID effort (right panel, bottom). The participants’ perceptions of non-returnees and returnees are different (p < 0.01, Table S4), which makes the mediation analyses possible.

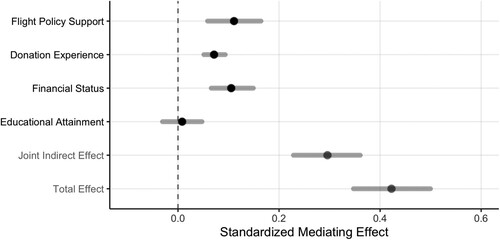

We next carry out joint mediation analysis with four perceived partner characteristics: likelihood of donation to China’s pandemic mitigation efforts, support for China’s flight restriction policies, financial status, and educational attainment. For this analysis we use the full sample comprising both primed and non-primed groups. We acknowledge that our mediators may be confounded by other measured and unmeasured variables, resulting in biased estimates if we rely on individual mediation pathways.Footnote13

presents the results of the joint mediation analysis that addresses H3 and H4 in the full sample, and similar results are observed across the primed and non-primed groups (see Figure S6). We first examine how perceptions of returnees’ adherence to markers of Chinese national membership affect DG contribution. We observe a 0.11 standard deviation change in contribution (p < 0.001, two-sided) for every one standard deviation change in participants’ perception of their partner’s flight policy support, accounting for about 26% of the total effect. The mediating effect of the perceived likelihood of donation is 0.07 (p < 0.001, two-sided) and accounts for 17% of the total effect. This provides support for H3, that perceived performances of national membership mediate how partners, therefore returnees, have been treated.

Figure 4. Standardized mediating effects on DG contribution.

Note: Full sample and coefficients are standardized. Whiskers denote 95% confidence intervals constructed with 1000 simulations based on a quasi-Bayesian Monte Carlo approximation. Participant-level controls include gender, age, educational attainment, monthly family income, residence in a first-tier city, CCP membership, Hukou type, and participation in a mass PCR test in the past month.

We next turn to proxies of class as mediators. Participants’ assumptions regarding their returnee partner’s economic status mediate the effect of being paired with a returnee partner on DG contributions. The standardized mediating effect of perceived financial status is 0.11 (p < 0.001) and accounts for 25% of the total effect. The perception of the partner’s educational attainment, by contrast, does not show a statistically significant mediating effect. The standardized effects and proportions mediated are substantively similar in the primed and non-primed groups (see Figure S6). This finding provides evidence for H4, that class resentment based on income, but not educational attainment, mediates unequal treatment. This finding is not surprising for two reasons. First, our sample is more educated than the Chinese population. According to the 2020 census 15% of the Chinese population holds a university degree,Footnote14 while 72% of our sample does. Thus, it is likely that our participants perceive their returnee partners as peers and potential competitors on the job market who do not deserve the extra benefits they are believed to receive. Second, Chinese society tends to tolerate merit-based inequalities, and education has been perceived as a signal of individual effort and a meritocratic channel of social mobility (Wu Citation2009). In contrast, the wealthy – and especially those who inherited their wealth – are seen as having gleaned their advantage in an undeserved and potentially unscrupulous manner, and thus have been the subject of much resentment in recent years (Zang Citation2008).Footnote15

The joint indirect effect accounts for 71% of the total effect, which suggests that participants’ perception of their paired partners is a crucial factor driving the observed unequal treatment. Specifically, how participants imagine their partner’s adherence to performances of national membership and class status are major impetuses behind participants’ discrimination against returnees, with the former mediating a higher share of the effect (44%) than the latter (27%).Footnote16

If the national membership of Chinese returnees is indeed under scrutiny, we expect participants who identify as less cosmopolitan to treat returnees worse (H5). We indeed observe a statistically significant interaction effect after accounting for participant-level controls. Every one standard deviation increase in cosmopolitanism is associated with a 0.15 standard deviation decrease in the expected amount taken away from the paired partner (p < 0.01), see . Similar results are obtained with a categorical operationalization of cosmopolitan identity (Figure S3 and Table S5). Taken together, these findings support H5.

Figure 5. Standardized interaction effect of cosmopolitan identity and returnee recipient assignment on DG contribution.

Note: Full sample and coefficients are standardized. Whiskers and shadows denote 95% confidence intervals. Participant-level controls include gender, age, educational attainment, family income, residence in a first-tier city, CCP membership, household registration type, and participation in a mass PCR test in the past month.

Conclusion and discussion

Migratory patterns and geopolitical tensions induced by COVID-19 provide the context for this large-scale, pre-registered online survey experiment in China investigating how returnees are perceived and treated by their domestic peers. In an era in which return migration is an increasingly common practice and often an institutionalized state development strategy, how domestic populations imagine, recognize, and treat the membership claims of returnees constitutes a topic essential to our understanding of national identity and migration. To date, however, it has been largely overlooked in the existing literature (for an exception, note Park Citation2020), particularly in work taking a quantitative approach.

In review, this paper first illustrates that the Chinese domestic population imagines returnees as a group of elites with substantial social and financial capital, even though returnees are actually a socio-economically diverse population (Ma Citation2020). Second, we systematically show that Chinese overseas returnees are subjected to discrimination by their domestic peers. In so doing, we complement prior qualitative work focused on how returning migrants negotiate their own sense of national belonging (Binah-Pollak and Yuan Citation2022; Paul Citation2021; Zhang Citation2019) and highlight tensions between formal and informal membership in the nation-state (Brubaker Citation2010). Third, we demonstrate two possible mechanisms behind unequal treatment: boundary-making against – or othering of – returnees, who are both citizens and co-ethnics, on the basis of their perceived adherence to key markers of national membership and perceived class status.

While COVID-19 and the migration patterns it sparked shaped the context of our experiment, our results indicate that fear of contagion is not driving the discriminatory behavior. Making participants aware of the arduous quarantine protocols, and thus the low risk of returnees spreading COVID-19, did not curb participants’ discrimination against their returnee partners. These findings suggest that participants’ discriminatory treatment stems from attitudes extending beyond public health concerns. Rather, COVID-19 has likely acted as a lens refracting existing social tensions and political shifts in Chinese society as suggested above. In this sense, unequal treatment in this setting is probably similar to unequal treatment of Chinese-born individuals in the US, where political elites were able to leverage fear of contagion to legitimize discriminatory behavior and sustain its existence (Abascal, Makovi, and Xu Citation2023).

To further decipher the root of unequal treatment, we turned to the characteristics participants attributed to returnees. Applying mediation analysis, we established that participants’ perceptions of their partners’ key performances of national belonging (donating to help China’s fight against COVID-19 and supporting China’s COVID-19 mitigation policies) and class largely explained their discriminatory behavior. These findings suggest that unequal treatment of returnees during the pandemic may be a reflection of underlying contested national membership and class resentment, even though it was often expressed in language stressing fears of viral contagion.

More research is required to fully disentangle the factors shaping Chinese domestic actors’ discriminatory attitudes and behaviors towards returnees. Yet, regardless of the mechanism driving these views, our results indicate that even though returnees are formal members of the Chinese nation, their informal claims to national membership are contested. This result improves our understanding of how boundaries around national identity are constructed in contemporary Chinese society, and how migration alters notions of national belonging more generally. A limitation of this conclusion is that ultimately what meaning respondents attach to donation behavior and supporting COVID flight policies remains an assertion, though it rests on previous work and the public discourse surrounding these policies.

Our study has several additional limitations that should be considered in tandem with our findings. First, we did not obtain data regarding how non-migrants treated returnees prior to the pandemic. Previous surveys, for instance, suggest that the Chinese public might have already associated certain characteristics with returnees that would have lowered their give-or-take DG contributions prior to COVID-19 (Tai and Truex Citation2015). Consequently, we cannot speak to how the pandemic may have augmented (or possibly diminished) pre-existing biases. Similarly, the duration of returnees’ sojourn abroad likely shapes how they are perceived by their home-country peers. We did not probe how the length of time abroad or ‘type’ of journey (e.g., work, study, etc.) shape how the Chinese public perceives returnees. Future work should investigate these issues. In addition, more research is needed to fully unpack the relationship between class and national belonging which were operationalized separately but, based on prior work, are likely intertwined. Finally, our experimental design did not investigate returnees’ own sense of national membership. While prior research has suggested returnees often experience a sense of ‘double exclusion’ and alienation following their return (Hu, Xu, and Tu Citation2022), future scholarship should systematically examine whether returnees’ experiences with discrimination trigger a liminal sense of belonging.

In conclusion, this paper makes two primary contributions. First, we built on the growing literature emphasizing the importance of participants’ perceptions of their paired partners in behavioral games by introducing a new joint mediation analysis strategy. Second, we advanced sociological understandings of contested national belonging and class resentment by examining Chinese citizens’ perceptions of returning migrants during the COVID-19 pandemic. Growing interest in the multi-dimensionality of national membership and the increasing institutionalization of return migration globally has rendered public attitudes about returnees a critical angle to explore. Our paper therefore calls for research to uncover the mechanisms underlying both pro-social behavior towards migrants specifically, and boundary construction tied to national belonging and class dynamics more generally. The social, political, and contextual forces surrounding return migration in mainland China make the country a noteworthy case study with which to broaden our understanding of how migration history shapes in-group/out-group formation and the informal dynamics of national membership claims.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (2.6 MB)Acknowledgments

We thank Eli Wilson for feedback on a previous draft.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data and code necessary to reproduce the analyses reported are available on the Open Science Framework at: https://osf.io/csd49/.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 https://www.wsj.com/articles/flying-to-china-in-economy-class-will-cost-you-5-000-11666003410, accessed 3/21/2024.

2 https://www.scmp.com/news/china/politics/article/3155699/chinas-quarantine-how-long-what-does-it-cost-and-what-food, accessed 3/21/2024.

4 https://www.scmp.com/comment/opinion/article/3178036/resentment-china-against-those-studying-abroad-during-covid-19, accessed 3/21/2024.

5 Although returnees and non-migrants are all full legal members of the nation, we refer to Chinese individuals who did not migrate abroad as “Chinese citizens” and those who migrated internationally and returned during the pandemic as “returnees.”

6 We thank Reviewer 2 for pushing us to stress this point.

7 http://opinion.people.com.cn/n1/2019/0929/c1003-31378679.html, accessed 3/21/2024.

8 https://www.caixinglobal.com/2023-11-09/in-depth-why-foreign-degrees-have-lost-their-luster-for-chinese-graduates-102126670.html, accessed 3/21/2024.

10 https://edition.cnn.com/2021/11/14/china/china-border-closure-inward-turn-dst-intl-hnk/index.html, accessed 3/21/2024.

11 See Q259 of the World Values Survey 2017–2021, Wave 7.

12 We assume the mediators may be correlated via a non-causal path, and that the correlation remains the same in all conditions. However, the implicit assumption that the correlation between the counterfactual mediators is the same regardless of the treatment might be violated. Although our approach may be less biased than the common practice of conducting mediation analysis separately for the mediators, we only interpret our findings as associational evidence.

13 We report an empirical indication of this potential bias: the sum of the proportions mediated in the four individual mediation pathways exceeded 100% (VanderWeele and Vansteelandt Citation2014), i.e., the joint indirect effect is not equal to the sum.

15 https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-57380367, accessed 3/26/2024.

16 Individual mediation analyses conducted in parallel showed substantively similar findings, in which ascribed economic status, policy support, and donation history remain the three statistically significant mediators with substantially large effects. COVID-19-specific objective experiences, by contrast, produced modest effects in magnitude and show inconsistent statistical significance across conditions. Figure S8 contains additional information.

References

- Abascal, Maria, Kinga Makovi, and Yao Xu. 2023. “Politics, Not Vulnerability: Republicans Discriminated Against Chinese-Born Americans Throughout the COVID-19 Pandemic.” The Journal of Race, Ethnicity, and Politics 8 (1): 83–104. https://doi.org/10.1017/rep.2022.28.

- Baldassarri, Delia, and Maria Abascal. 2017. “Field Experiments Across the Social Sciences.” Annual Review of Sociology 43 (1): 41–73. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112445.

- Baldassarri, Delia, and Guy Grossman. 2013. “The Effect of Group Attachment and Social Position on Prosocial Behavior: Evidence from Lab-in-the-Field Experiments.” PLoS One 8: e58750. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0058750.

- Bardsley, Nicholas. 2008. “Dictator Game Giving: Altruism or Artefact?” Experimental Economics 11 (2): 122–133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-007-9172-2.

- Benz, Matthias, and Stephan Meier. 2008. “Do People Behave in Experiments as in the Field? —Evidence from Donations.” Experimental Economics 11 (3): 268–281. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-007-9192-y.

- Bieber, Florian. 2022. “Global Nationalism in Times of the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Nationalities Papers 50 (1): 13–25. https://doi.org/10.1017/nps.2020.35.

- Binah-Pollak, Avital, and Shiran Yuan. 2022. “Negotiating Identity by Transnational Chinese Students During COVID-19.” China Information 36 (2): 180–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/0920203X211065013.

- Bonikowski, Bart. 2016. “Nationalism in Settled Times.” Annual Review of Sociology 42 (1): 427–449. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-081715-074412.

- Bonikowski, Bart. 2017. “Ethno-nationalist Populism and the Mobilization of Collective Resentment.” The British Journal of Sociology 68: S181–S213. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12325.

- Bonikowski, Bart, and Yueran Zhang. 2023. “Populism as Dog-Whistle Politics: Anti-Elite Discourse and Sentiments Toward out-Groups.” Social Forces 102 (1): 180–201. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/soac147.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1977. Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Brubaker, Rogers. 1992. Citizenship and Nationhood in France and Germany. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Brubaker, Rogers. 2010. “Migration, Membership, and the Modern Nation-State: Internal and External Dimensions of the Politics of Belonging.” The Journal of Interdisciplinary History 41 (1): 61–78. https://doi.org/10.1162/jinh.2010.41.1.61.

- Brubaker, Rogers. 2020. “Populism and Nationalism.” Nations and Nationalism 26 (1): 44–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/nana.12522.

- Brubaker, Rogers, Margit Feischmidt, Jon Fox, and Liana Grancea. 2006. “Nationalist Politics and Everyday Ethnicity in a Transylvanian Town.” In Nationalist Politics and Everyday Ethnicity in a Transylvanian Town. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Chen-Weiss, Jessica. 2019. “How Hawkish is the Chinese Public? Another Look at “Rising Nationalism” and Chinese Foreign Policy.” Journal of Contemporary China 28 (119): 679–695. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2019.1580427.

- Du, Zaichao, Yuting Sun, Guochang Zhao, and David Zweig. 2021. “Do Overseas Returnees Excel in the Chinese Labour Market?” The China Quarterly 247: 875–897. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741021000023.

- Elias, Amanuel, Jehonathan Ben, Fethi Mansouri, and Yin Paradies. 2021. “Racism and Nationalism During and Beyond the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 44 (5): 783–793. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2020.1851382.

- Feliciano, Cynthia. 2020. “Immigrant Selectivity Effects on Health, Labor Market, and Educational Outcomes.” Annual Review of Sociology 46 (1): 315–334. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-121919-054639.

- Flores, René D., and Ariel Azar. 2023. “Who Are the “Immigrants”?: How Whites’ Diverse Perceptions of Immigrants Shape Their Attitudes.” Social Forces 101 (4): 2117–2146. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/soac113.

- Franzen, Axel, and Sonja Pointner. 2013. “The External Validity of Giving in the Dictator Game” Experimental Economics 16 (2): 155–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-012-9337-5.

- Gereke, Johanna, Max Schaub, and Delia Baldassarri. 2022. “Immigration, Integration and Cooperation: Experimental Evidence from a Public Goods Game in Italy.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48 (15): 3761–3788. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2021.1949269.

- Glaeser, Edward L, David I. Laibson, Jose A. Scheinkman, and Christine L. Soutter. 2000. “Measuring Trust” Quarterly Journal of Economics 115 (3): 811–846. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355300554926.

- Goldman, Merle, and Elizabeth J. Perry. 2002. Changing Meanings of Citizenship in Modern China (Vol. 13). Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Guo, Zhonghua. 2021. “Introduction: Navigating Chinese Citizenship.” In The Routledge Handbook of Chinese Citizenship, 1–14. London: Routledge.

- Hainmueller, Jens, Daniel J. Hopkins, and Teppei Yamamoto. 2014. “Causal Inference in Conjoint Analysis: Understanding Multidimensional Choices via Stated Preference Experiments.” Political Analysis 22 (1): 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpt024.

- Hainmuller, Jens, and Michael J. Hiscox. 2010. “Attitudes Toward Highly Skilled and Low- Skilled Immigration: Evidence from a Survey Experiment.” American Political Science Review 104 (1): 61–84. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055409990372.

- Hanser, Amy, and Jialin Camille Li. 2015. “Opting Out? Gated Consumption, Infant Formula and China’s Affluent Urban Consumers.” The China Journal 74: 110–128. https://doi.org/10.1086/681662.

- Ho, Elaine Lynn-Ee. 2016. “Incongruent Migration Categorisations and Competing Citizenship Claims‘: Return’and Hypermigration in Transnational Migration Circuits.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42 (14): 2379–2394. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2016.1205802.

- Ho, Elaine Lynn-ee. 2019. Citizens in Motion: Emigration, Immigration, and Re-Migration Across China’s Borders. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Hu, Yang, Cora Lingling Xu, and Mengwei Tu. 2022. “Family-mediated Migration Infrastructure: Chinese International Students and Parents Navigating (Im)Mobilities During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Chinese Sociological Review 54 (1): 62–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/21620555.2020.1838271.

- Imai, Kosuke, Luke Keele, and Dustin Tingley. 2010. “A General Approach to Causal Mediation Analysis.” Psychological Methods 15: 309–334. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020761.

- Jérolon, Allan, Laura Baglietto, Etienne Birmelé, Flora Alarcon, and Vittorio Perduca. 2021. “Causal Mediation Analysis in Presence of Multiple Mediators Uncausally Related.” The International Journal of Biostatistics 17 (2): 191–221. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijb-2019-0088.

- Jia, Hepeng, and Xi Luo. 2023. “I Wear a Mask for My Country: Conspiracy Theories, Nationalism, and Intention to Adopt Covid-19 Prevention Behaviors at the Later Stage of Pandemic Control in China.” Health Communication 38 (3): 543–551. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2021.1958982.

- Kanbur, Ravi, Yue Wang, and Xiaobo Zhang. 2021. “The Great Chinese Inequality Turnaround.” Journal of Comparative Economics 49 (2): 467–482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2020.10.001.

- Kim, Jaeeun. 2016. Contested Embrace: Transborder Membership Politics in Twentieth-Century Korea. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Kraut, Alan M. 1994. Silent Travelers: Germs, Genes, and the ‘Immigrant Menace’. New York: Basic Books.

- Lee, Ching Kwan. 2017. The Specter of Global China: Politics, Labor, and Foreign Investment in Africa. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Legewie, Joscha. 2013. “Terrorist Events and Attitudes Toward Immigrants: A Natural Experiment.” American Journal of Sociology 118 (5): 1199–1245. https://doi.org/10.1086/669605.

- Li, Gordon C. 2021. “From Parvenu to “Highbrow” Tastes: The Rise of Cultural Capital in China’s Intergenerational Elites.” The British Journal of Sociology 72 (3): 514–530. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12862.

- Liu, Jiacheng. 2020. “From Social Drama to Political Performance: China’s Multi-Front com- bat with the Covid-19 Epidemic.” Critical Asian Studies 54: 473–493. https://doi.org/10.1080/14672715.2020.1803094.

- Liu, Jiaqi M. 2021. “Citizenship on the Move: The Deprivation and Restoration of Emigrants’ Hukou in China.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (3): 557–574. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1788381.

- Liu, Jiaqi M. 2022. “When Diaspora Politics Meet Global Ambitions: Diaspora Institutions Amid China’s Geopolitical Transformations.” International Migration Review 56 (4): 1255–1279. https://doi.org/10.1177/01979183211072824.

- Liu, Jiaqi M., and Rui Jie Peng. 2023. “Mobility Repertoires: How Chinese Overseas Students Overcame Pandemic-Induced Immobility.” International Migration Review 0: 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/01979183231170835.

- Liu, Hong, and Els van Dongen. 2016. “China’s Diaspora Policies as a new Mode of Transnational Governance.” Journal of Contemporary China 25 (102): 805–821. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2016.1184894.

- Lo, Lucia, Wei Li, and Yining Tan. 2023. “Students on the Move? Intellectual Migration and International Student Mobility.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 49 (18): 4621–4640. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2023.2270331.

- Ma, Yingyi. 2020. Ambitious and Anxious: How Chinese College Students Succeed and Struggle in American Higher Education. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Ma, Haijing, and Claude Miller. 2021. “Trapped in a Double Bind: Chinese Overseas Student Anxiety During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Health Communication 36 (13): 1598–1605. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2020.1775439.

- Makovi, Kinga, and Christopher Winship. 2021. “Advances in Mediation Analysis.” In Research Handbook on Analytical Sociology. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Markel, Howard. 1999. Quarantine: East European Jewish Immigrants and the New York City Epidemics of 1892. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Miao, Ying. 2020. “Can China be Populist? Grassroot Populist Narratives in the Chinese Cyberspace.” Contemporary Politics 26 (3): 268–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569775.2020.1727398.

- Miao, Lu, Jinlian Zheng, Jason Allan Jean, and Yixi Lu. 2022. “China’s International Talent Policy (ITP): The Changes and Driving Forces, 1978-2020.” Journal of Contemporary China 31 (136): 644–661. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2021.1985843.

- Park, Sung-Choon. 2020. Korean International Students and the Making of Racialized Transnational Elites. London: Lexington Books.

- Paul, Anju Mary. 2021. Asian Scientists on the Move: Changing Science in a Changing Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Perry, Elizabeth. 2021. “Epilogue: China’s (R)evolutionary Governance and the COVID-19 Crisis.” In Evolutionary Governance in China: State-Society Relations Under Authoritarianism, edited by Szu-Chien Hsu, Kelle S. Tsai, and Chun-Chun Chang. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Ren, Na, and Hong Liu. 2019. “Domesticating‘Transnational Cultural Capital’: The Chinese State and Diasporic Technopreneur Returnees.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (13): 2308–2327. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1534583.

- Rithmire, Meg, and Courtney Han. 2020. “China’s Management of COVID-19 (A): People’s War or Chernobyl Moment.”.

- Rogaski, Ruth. 2004. Hygenic Modernity: Meanings of Health and Disease in Treaty Port China. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Rosenberg, Charles E. 1989. “What is an Epidemic? AIDS in Historical Perspective.” Daedalus 118: 1–17. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20025233.

- Saxenian, AnnaLee. 2005. “From Brain Drain to Brain Circulation: Transnational Communities and Regional Upgrading in India and China.” Studies in Comparative International Development 40 (2): 35–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02686293.

- Seol, Dong-Hoon, and John D Skrentny. 2009. “Ethnic Return Migration and Hierarchical Nationhood: Korean Chinese Foreign Workers in South Korea.” Ethnicities 9 (2): 147–174. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468796808099901.

- Singer, David A., and Kai Quek. 2022. “Public Attitudes Toward Internal and Foreign Migration: Evidence from China.” Public Opinion Quarterly 86 (1): 82–106. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfab065.

- Su, Phi Hong. 2022. The Border Within: Vietnamese Migrants Transforming Ethnic Nationalism in Berlin. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Tai, Qiuqing, and Rory Truex. 2015. “Public Opinion Towards Return Migration: A Survey Experiment of Chinese Netizens.” The China Quarterly 223: 770–786. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741015000879.

- Teo, Sin Yih. 2011. “‘The Moon Back Home is Brighter’?: Return Migration and the Cultural Politics of Belonging.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 37 (5): 805–820. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2011.559720.

- Tu, Siqi. 2021. “Destination Diploma: How Chinese Upper-Middle-Class Families “Outsource” Secondary Education to The United States.” Ph.D. thesis, The City University of New York.

- VanderWeele, Tyler, and Stijn Vansteelandt. 2014. “Mediation Analysis with Multiple Mediators.” Epidemiologic Methods 2: 95–115.

- Wang, Leslie K. 2016. “The Benefits of in-Betweenness: Return Migration of Second- Genera- Tion Chinese American Professionals to China.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42 (12): 1941–1958. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2016.1139447.

- Wang, Zhenyu, and Yuzhou Tao. 2021. “Many Nationalisms, one Disaster: Categories, Attitudes and Evolution of Chinese Nationalism on Social Media During the COVID-19 pan- Demic.” Journal of Chinese Political Science 26 (3): 525–548. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-021-09728-5.

- Wimmer, Andreas. 2017. “Power and Pride National Identity and Ethnopolitical Inequality Around the World.” World Politics 69 (4): 605–639. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0043887117000120.

- Wu, Xiaogang. 2009. “Income Inequality and Distributive Justice: A Comparative Analysis of Mainland China and Hong Kong.” The China Quarterly 200: 1033–1052. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741009990610.

- Yang, Li, Filip Novokmet, and Branko Milanovic. 2021. “From Workers to Capitalists in Less Than two Generations: A Study of Chinese Urban top Group Transformation Between 1988 and 2013.” The British Journal of Sociology 72 (3): 478–513. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12850.

- Yu, Jing. 2021. “Caught in the Middle? Chinese International Students’ Self-Formation Amid Politics and Pandemic.” International Journal of Chinese Education 10: 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/22125868211058911.

- Zang, Xiaowei. 2008. “Market Transition, Wealth, an Status Claims.” In The New Rich in China, edited by David S.G. Goodman. London: Routledge.

- Zhang, Yingchan. 2019. “Making the Transnational Move: Deliberation, Negotiation, and Disjunctures among Overseas Chinese Returnees in China.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (3): 455–471. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1459182.

- Zhang, Chenchen. 2020. “Right-wing Populism with Chinese Characteristics? Identity, Otherness and Global Imaginaries in Debating World Politics Online.” European Journal of International Relations 26 (1): 88–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066119850253.

- Zhang, Li. 2021. The Origins of COVID-19: China and Global Capitalism. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Zhang, Chenchen. 2022. “Contested Disaster Nationalism in the Digital age: Emotional Registers and Geopolitical Imaginaries in COVID-19 Narratives on Chinese Social Media.” Review of International Studies 48: 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210522000018.

- Zhou, Yu, and Abigail E. Coplin. 2022. “Innovation in a Science-Based Sector: The Institutional Evolution Behind China’s Emerging Biopharmaceutical Innovation Boom.” The China Review 22: 39–76. https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/849118.