ABSTRACT

A successful global transition to net-zero emissions requires complex transformational change involving stakeholders from across society. Traditionally, stakeholder engagement has been debated predominantly from a pragmatic, functionalist and instrumental perspective. Recent approaches in business communication, sustainability, energy and environmental management show that meaningful and ‘sustainable’ stakeholder engagement is helpful in maintaining an organisation’s social licence to operate. We problematise the notion of participation in deliberative processes and analyse whether the outcomes of an online Australian citizens’ panel are truly representative of all participants or whether specific cultural and demographic factors, particularly gender, influence participation, potentially shaping the outcome. The study shows how gender need to be considered and managed as part of a legitimate deliberation process. Applying Gastil’s input-process-outcome model as a framework, we examine the engagement achieved through deliberations conducted on Zoom. We focus on gender as a variable and the role of the facilitator in managing participation. The results suggest that participants’ contributions to discussions vary based on gender of both participants and facilitators. Based on findings, the challenges of achieving equality in participatory processes are identified. The facilitator’s role is re-defined as a curator of the stakeholder engagement processes, complementing existing theory on stakeholder participation and engagement.

Introduction

Moving towards net-zero greenhouse gas emissions requires a fundamental shift in how key sectors such as electricity generation, transport, manufacturing and mining operate. The United Nations Climate Change Conference of the Parties discussions in Glasgow and Egypt were followed by news streams increasingly reporting commitments by governments and corporations to net-zero and purposeful decarbonisation. However, to successfully achieve change we need actors, both individuals and organisations, to translate these declarations into action.

Given the magnitude and speed of the proposed transition required, tensions and trade-offs exist, and too often, the required decisions are made without seeking to understand the views and experiences of the communities most affected by those decisions and from a range of stakeholders within those communities. Such a lack of engagement has been shown to have far reaching and often negative consequences, often resulting in failed projects, protests and outrage at the local level (Edinger-Schons et al. Citation2020; Gallois et al. Citation2017; Gunningham, Kagan, and Thornton Citation2004; Scherer, Palazzo, and Matten Citation2014). Given the scale and speed of the change required it is vital that all members of society are appropriately engaged in the transition process.

In recognition of the need to engage all members of society there has been discussion about the role of gender, and more specifically women, in climate change and net-zero action. In their study of gender and climate change, Pearse (Citation2017, 1) found that ‘gender relations are an integral feature of social transformations associated with climate change’. Others have suggested that gender gaps in concern for climate change emerge in wealthier countries, where climate mitigation becomes a women’s issue (Bush and Clayton Citation2023). To encourage women to participate on the topic of climate change, an observation from Polletta and Bobby Chen (Citation2013) is useful, when it comes to deliberations in the public sphere: often women are truly equal participants in forums where feminine values and identity are accentuated.

In recent years, researchers, government and industry representatives have been advocating for cross-sectoral and participatory approaches when it comes to the implementation of energy technologies, innovations and policies (Batel and Devine-Wright Citation2015; MacArthur Citation2016). A key reason for such a call is that traditional decision-making tools mainly involve one way information provision and/or top-down steering of citizens towards different patterns of behaviour. Such processes have struggled to deal with the complex, contested and highly controversial nature of these problems. In direct contrast to such unilateral approaches, deliberative processes provide an avenue for more participatory, bi-directional engagement with communities on the topic of low carbon energy (Ashworth et al. Citation2010). This is based on the recognition of these processes being able to access a cross section of the community, representing a broad range of perspectives, rather than just those in the majority (Batel, Devine-Wright, and Tangeland Citation2013).

Inclusive processes, where rights and justice for plural groups are acknowledged, have won the support from public relations, business, corporate social responsibility and sustainability communication researchers, as well as those within the field of environmental management (Diehl et al. Citation2017; Rasche, Morsing, and Moon Citation2017; Weder Citation2021; Weder, Krainer, and Karmasin Citation2021). Recent studies and conceptual work in these areas have highlighted the potential breadth of the application of deliberative processes showing that stakeholder engagement is no longer (only) considered as a ‘tool’ in campaigns or social change processes (Dutta Citation2020). Instead, they suggest deliberative processes not only perform a communication role to create greater social impact and greater fairness in participation, but also help to provide organisations and institutions with insights around their ‘social licence to operate’ (SLO) and the legitimacy of their approaches (Hurst and Johnston Citation2021; Hurst and IhlenCitation 2018).

Deliberation has been defined as mutual communication that involves weighing and reflecting on preferences, values and interests regarding matters of common concern (Dryzek Citation2002; Mansbridge Citation2015). Deliberations are usually informed by the provision of independent expert information (De Vries et al. Citation2010) and focus on citizens’ interpretations of the information and issues. This is in contrast to top-down processes which tend to privilege experts’ and interest groups’ views (De Vries et al. Citation2010). As such, they are also well regarded for building legitimacy, fairness and trust amongst stakeholders (Dryzek Citation2002; Flynn, Ricci, and Bellaby Citation2013; Goodman and Mäkinen Citation2022; Mansbridge Citation2015; Moffat and Zhang Citation2014).

Given the requirement for effective communication and stakeholder integration to achieve an accelerated and just energy transition, along with the opportunity of deliberative processes to convey knowledge and introduce diversity in such conversations, it is vital to examine the extent to which current deliberative methods can achieve fair and equal representation and participation. To understand this, we examined the results from a citizens’ panel, used to assess the public’s response towards the role of future fuels in Australia’s low-carbon energy mix. The panel assessed was part of a series of panels conducted around Australia that covered the same topic and followed the same process but with groups at different locations. Conducted entirely online, the citizens’ panel was held between February and March 2021. We investigate whether the conversations that occurred in the online deliberative process followed were influenced by social norms around gender. Cislaghi and Heise (Citation2020) differentiate between ‘social norms’ and ‘gender norms’. They explain that

Gender norms are social norms defining acceptable and appropriate actions for women and men in a given group or society. They are embedded in formal and informal institutions, nested in the mind, and produced and reproduced through social interaction. They play a role in shaping women and men's (often unequal) access to resources and freedoms, thus affecting their voice, power and sense of self. (Cislaghi and Heise Citation2020, 415–416)

In the following sections, we present literature on deliberative processes and the importance of engagement for informing participants on the topic of transitioning to a low-carbon future as well as enhance acceptance or SLO for new technological solutions. The methodology and analysis of the citizens’ panels’ data which focus on the interactions within the smaller group discussions in panel breakout rooms is explained. After presenting and discussing the results of the analysis through a gender lens, we provide recommendations for promoting equality in participation in future online deliberative processes and the implications for organisations interested in ‘opening up’ their engagement practices. We also develop recommendations related to the role of the facilitator in stakeholder engagement processes, which can lead to further theoretical development and practical implementations.

Theoretical concepts

Stakeholder engagement by organisations

With environmental, social and governance (ESG) principles now a key consideration of stakeholders, corporations and other business organisations today are increasingly being held to account on elevated standards (Polman and Winston Citation2021). It has been shown that firms with superior corporate social responsibility performance face lower capital constraints with the impact on access to capital driven by social and environmental performance, suggesting that these issues are relevant for investors (Cheng, Ioannou, and Serafeim Citation2014). While many organisations see such stakeholder engagement on environmental and social issues as part of their day-to-day business and an investment in their operations, there are some that may undervalue such engagement. In a society where stakeholder expectations are evolving at pace, organisations that fail to engage meaningfully may be less likely to hold an SLO (Brueckner and Eabrasu Citation2018), particularly if they have failed to focus on ensuring a diverse and inclusive approach to the engagement. Similarly, secondary stakeholders – non-governmental organisations, civil society groups, activist groups, outsiders and social movements – increasingly influence corporate decision making and their attention to fairness in the process (de Bakker and Hond Citation2008).

SLO and three processes of stakeholder engagement:

The SLO term has been connected to various issues over the decades but has been predominantly used in critical sectors like the mining industry since the mid-1990s (Thomson and Boutilier Citation2011). More recently, it has gained traction across multiple sectors including banking, health and agriculture and often discussed from a communication perspective (Hurst and Johnston Citation2021; Voyer and van Leeuwen Citation2018; Weder Citation2021).

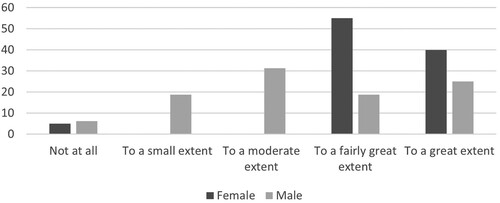

Moffat and Zhang (Citation2014), among others, describe an SLO as the ongoing acceptance or approval of an operation by local community stakeholders who are affected by it and who can affect its profitability (Moffat and Zhang Citation2014; Thomson and Boutilier Citation2011). While an SLO can be relatively informal, the costs of not holding an SLO can be large, ranging from economic losses to reputational damage. This can have far reaching consequences beyond immediate projects, reinforcing the need for fair and inclusive communicative processes to reduce the risks of project failure (Lesser Citation2021). Here, stakeholder management approaches are often perceived as limited because they focus on rather one-directional, transmissive education or information approaches (see ).

Figure 1. Stakeholder management, engagement and participation.

Source: Adapted from Weder (Citation2022), Weder and Erikson (Citation2023).

Going beyond rather simplistic transmission models, dialogue is often seen as ‘ideal’ stakeholder interaction (Pieczka Citation2018; Theunissen and Wan Noordin Citation2012), focusing on more balanced, horizontal instead of hierarchical communication processes, including deliberation – at least as an idea or concept (). However, dialogue and engagement are still predominantly discussed from a solution-oriented, instrumentalist and functional approach and therefore a rather utilitarian perspective (O’Riordan and Fairbrass Citation2014), following the idea of active involvement of only certain social actors in decision-making processes (Crane et al. Citation2008; Idowu et al. Citation2013).

Criticism is also articulated by other researchers for not addressing systemic power imbalances or for using dialogue as a ‘tool’ to gain publicity (Weder Citation2021). Practitioners are often challenged by conflicts of interests and pluralvocacy (to ensure all voices including marginalised groups are included), especially in a digitalised world. Therefore, we introduce a third model of deliberative processes with a strong participatory and equality character (based on work around agonism and strategic problematisation (Mouffe Citation2005; Citation2013; Weder Citation2021). We define stakeholder engagement as the exchange of ideas either in response to, or to facilitate change by including sense- and meaning-making processes. Such self-organised, design and participatory processes become even more attractive because they can be aimed at a wide range of stakeholder groups and voices to facilitate change in energy transition with community involvement, gender equality as well as enhance legitimacy and an SLO.

A successful deliberative process with high-quality deliberation is characterised by equal participation and respect for others (De Vries et al. Citation2010). Deliberation ‘involves weighing and reflecting on preferences, values, and interests regarding matters of common concern’ (Bächtiger et al. Citation2018, 1). Criticisms have been levelled against deliberative processes including that they may fail to produce an equal representation of cultural patterns, diversity and demographic backgrounds. For example, substantive representation for women is not always present in deliberative, participatory processes (Karpowitz and Mendelberg Citation2014), which can result in polarised opinions (Schkade, Sunstein, and Hastie Citation2010). It has also been suggested that such processes may manifest majority interests as the common will of the community, whilst marginalising minority groups (Myers Citation2017). Often women, who are not a minority group, feel marginalised in the public sphere, where institutional settings convey gendered norms (Polletta and Bobby Chen Citation2013). Each of these aspects is a challenge for a facilitator who is at the frontline of managing the process of dialogue. We argue that the process of deliberation is therefore critical to the outcomes reached.

Variables and frameworks that describe methodological components of a deliberative study

Overall, deliberative processes are rooted in political philosophy and abstract social theory (Gastil Citation2018) and have links to cognitive theory, where solutions to complex social problems are not ‘given’ (to participants) but co-learned subsequent to a technical expert sharing information relevant to the exercise (Tyler Citation2009). Deliberative engagement is recognised as an opportunity to tackle wicked problems, ‘work through’ tough issues, form more nuanced public judgments, and support more inclusive civic action and public policies (Carcasson Citation2016).

The ability of citizens to advance arguments and have them considered fairly is essential to the equality and epistemic quality of deliberative processes (Myers Citation2017). Participation is defined as a speaker’s ability to participate freely in debate (Steenbergen et al. Citation2003). It follows that equal participation is seen as a person’s ability to participate in comparison to others (De Vries et al. Citation2010). Furthermore, equal participation requires that no one person or advantaged group dominate the process, even if the participants are not otherwise equal in power or status (Thompson Citation2008). Quick and Feldman (Citation2011) also suggest that inclusion and participation are two different dimensions of public engagement and that organising management of the public participants to incorporate both enhances the quality of the decisions reached and the community’s long-term capacities.

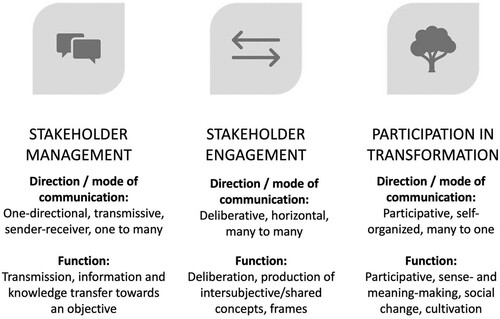

Most deliberative studies focus on deliberation at the scale of either small or large group discussion with the process being described by selecting variables from an ‘input-process-outcome model’ (Gastil Citation2018). An abstraction of Gastil’s model, presented in Figure 12 in Supplementary Materials, details three essential components to illustrate the methodology used in a deliberative study.

The three dimensions to the ‘input’ component include: (i) the larger context and purpose for which engagement is designed; (ii) the structural features of the engagement and (iii) the information resources (learning sessions) provided to the participants of the study. Next, the two dimensions to ‘process’ include: (i) how democratic participant relationships develop and evolve and (ii) how analytical rigour is assessed within deliberations. Lastly, there are two dimensions to outcomes: (i) direct, assessed in terms of decision satisfaction and decision quality and (ii) indirect in terms of participant transformation and/or policy/social outcomes.

Methods

Prior to commencement of any work, an ethics approval was sought and obtained through the university's research ethics and integrity process (Approval number: 2020/HE002473). In the following sections we explain the methods employed for the overall research. To explain the components of the deliberative process we use Gastil’s input-process-outcome model as a scaffold. is developed to describe the overarching components of the citizens’ panels, which we elaborate on further based on our analyses.

Figure 2. Inputs, processes and outcomes of the Australian citizens’ panels’ : A graphic abstraction where Gastil's (Citation2018) framework is used as a scaffold.

Input: content and purpose, features and provision of information

The Melbourne citizens’ panel was designed to assess public attitudes towards the role of future fuels in Australia’s low carbon fuel mix. Held in February to March 2021, the panels brought together members of the public from Greater Melbourne in Victoria. Other panels were conducted in South Australia and the Illawarra region, however these additional citizens’ panels are not the focus of this analysis. The Melbourne group was chosen for a focused examination because they were deemed to represent a group being highly reliant on fossil fuels.

Location profile – Melbourne: Melbourne, Australia is a stable, multicultural, liberal democratic society – where egalitarian values of merit-based reward, equal opportunity, freedom of expression and association and respect for others are espoused (Australian Government Citation2021). Although, widely shared, such values underpin most formal and informal institutions in Australian society, they are continually contested and re-shaped in political discourse (e.g. more recently the treatment of women in the Australian Parliament, fair treatment of refugees, self-determination for Indigenous Australians, religious freedoms resulting in discrimination of non-binary gendered people).

Panel participants were recruited via a third party with the expectation that they would commit to attending 2 × 2.5-hour evening sessions each week for three weeks, held over a four-week period due to a public holiday on one Monday. Forty-two participants were targeted for recruitment, profiled to statistically represent the demographics of the Australian public. Participants who attended all sessions were paid for their participation.

Greater Melbourne Participant Profiles: Participant demographics are provided in . Although the recruitment targeted participants who would represent the population demographics of Australia, the participants from Greater Melbourne had higher levels of education compared to the rest of the population based on 2016 Census data for that area. Overall, 71 per cent of participants selected the option of a ‘Bachelor Degree level and above’ to indicate the highest level of education they had attained. In Greater Melbourne, percentage of the population to have attained ‘Bachelor Degree and above’ is much lower at 27.5 per cent (Australian Bureau of Satistics Citation2016).

Table 1. Participant demographics for citizens’ panel.

Prior to the commencement of the panels the research team worked with an Industry Steering Committee (ISC) and an Independent Advisory Panel (IAP) to ensure the design of the process aligned with both industry interests and academic obligations of research rigour. The research team’s role included project planning, panel design and implementation, documentation and dissemination of results. The ISC and IAP independently made suggestions around the most appropriate topics for information to be presented, the experts who might deliver the information, questions to be investigated and what briefing materials should be sent to participants in advance of the citizens’ panels. The research team also developed pre- and post-surveys (see Ashworth et al. Citation2021a, Citation2021b for a full set of questions) to gather feedback from participants on the process and track changes in their knowledge and attitudes. Details of the learning topic areas and key questions examined by the participants within each session are provided in .

Table 2. Weekly topics and key questions addressed within the citizens panels.

Process: democratic participant relationships and analytical rigour

Due to COVID-19, all panels were moved to an online format using Zoom. A learning session was held every Monday, where expert presenters provided information to participants, with some opportunity for reflection in small breakout rooms and question time in plenary. On a separate, subsequent night of the week, the participants came together to deliberate on key questions. This involved a mix of plenary and small group deliberations (max six persons) using the breakout room facility on Zoom. Each breakout room had a trained facilitator who was tasked with assisting the deliberations and taking notes in a Google Doc – specifically developed to track the themes arising within the small groups. The lead facilitator was kept consistent across all citizens’ panel sessions across all weeks. The breakout room facilitator/participant combination was kept the same for each activity in a single week but varied across weeks. Activities ran for approximately 20 min each (see for key questions asked in activities).

Table 3. Questions covered in each week with reflection on complexity.

Reports summarising the outcomes, analysis of the information contained in the breakout room Google Docs, and answers to any outstanding participant questions were produced after each week’s session and sent to the participants via email in advance of the next learning session. Following the conclusion of the panel process an interim report was produced for the ISC, IAP and participants.

Outcomes: direct and indirect

In terms of direct outcomes, a set of normative principles were derived from the panel discussions to answer the question: What do you believe will be the principles that will be important in guiding Australia’s path to a low carbon energy future? Towards the end of the process, participants voted on whether each of the principles they developed collectively represented their individual view fully, partially or not at all. The outcome of the voting by participants on the level of alignment between the views of the individual and the principles established through the collective process (Ashworth et al. Citation2021a, 28) provides evidence for Gastil's first direct outcome dimension relating to the level of satisfaction and quality.

The indirect outcome dimension included within Gastil’s model was also examined in the research as the principles developed through the engagement process provide a rich evidence base upon which Australia’s future fuels’ policy may be shaped. As such, the principles have been tabled amongst policy makers from both federal and state governments and key industry organisations via a series of online workshops (Kambo et al. Citation2022). This delivers on the promise to participants to ensure their views are shared with the highest levels of government and industry stakeholders. Another indirect outcome – participant transformation – is evidenced via the self-reported survey data. Survey results have been documented to share findings more broadly showing how the deliberation shaped participants’ views and feelings about the process. Participants’ survey responses (in aggregated form) conveyed their support towards future fuels, indicating that organisations implementing future fuels will have an SLO (Ashworth et al. Citation2021a, 38-55).

Analysis

Data recorded

The Greater Melbourne panel generated over 13 hours of video recordings, equating to 2,867 interactions and more than 80,000 words once transcribed. The summary of items that were generated is presented in . To answer our research question on representation and equality in participation and facilitation, this article presents a quantitative analysis of the qualitative data items collected during the citizens’ panels.

Table 4. Data items and details for Greater Melbourne citizens’ panel.

Variables of interest

To address the question of representation and equal participation we query the qualitative data through criteria that underpin ‘quality’ in deliberations (De Vries et al. Citation2010; Steenbergen et al. Citation2003; Thompson Citation2008). De Vries et al. (Citation2010) and Thompson (Citation2008) identified that equal participation may be assessed by examining the data for the following factors: instances of engagement (individual participant speaking in breakout rooms); the duration of speaking time and the word count of each engagement by demographic. The analysis in this article solely focusses on gender.

In addition to examining the frequency, duration and word count of engagement by gender we also thematically examined the content of the interactions to explore quality in relation to the contribution of ideas and the extent to which the topics discussed were carried through into the outcomes of the deliberative process. The breakout room transcripts were examined for order of speech among participants and whether the ideas generated by an individual (male or female) were continued within the discussion and captured adequately in the weekly and interim reports back to the panel participants. We also include how this might vary, if at all, based on the gender of the small group facilitator.

As the breakout rooms were conducted on Zoom, the recordings were imported into the transcription software otter.ai allowing a transcript with speaker identification (number only) and time stamping to be generated. The automatically generated transcripts were reviewed for errors and inaccuracies and manually corrected. Two processes were then followed to analyse the data.

Part one: frequency, duration and word count of interactions in breakout room discussions

The transcripts, containing a code for each participant and timestamped for each, were imported into Excel with separate tabs for each week (1-3), activity (1-3/4) and facilitator (1-7). The duration for each interaction was calculated as the time difference between the timestamp for an interaction and that of the following interaction. The number of words in each interaction was counted using the relevant Excel formula function. However, timestamps for some interactions were missing. To impute the duration for these interactions, the average time taken per word was calculated for the whole breakout session and then multiplied by the word count for the interaction. The gender of each participant and facilitator was identified from the video recording and matched with each interaction. We acknowledge that identifying gender from video and voice does not capture non-binary gender identities or may incorrectly allocate gender, however our demographic survey responses show that no participants identified as non-binary. Using Excel, it was possible to evaluate each of the breakout room discussions in terms of the speaking time and the number of words spoken by each participant by gender.

Equal participation was further evaluated through an examination of patterns in the interactions in each breakout session. The number of interactions per participant (male or female) was identified and counted along with whether participants had repeated interactions. The interaction level data was then collated back to the session level to identify total interactions by male and female participants and combined with the gender of the facilitator to analyse interactions in relation to the gender composition of the room (i.e. male/female ratios) and the gender of the facilitator. However, variations in the length of session times, numbers of participants and the gender ratio in the breakout rooms posed challenges in calculating the average duration of interactions by gender. To address this, a weighted variable ‘participant per minute’ was calculated by dividing the total time of participant interactions in a session, divided by the total number of participant interactions, excluding the facilitator, in the session and it was used to normalise across the sessions to show interactions across the whole of the deliberative process. Therefore, all speaking time durations, word and frequency counts of interactions are reported as per participant per minute.

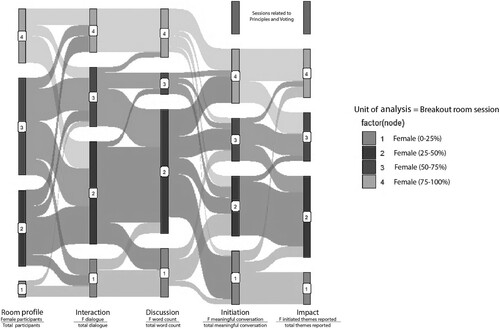

Finally, the interactions across the whole citizens’ panel process were captured and summarised in a Sankey diagram. A Sankey diagram is a data visualisation tool that shows the strength of relationships and direction of flows between variables (Bakenne, Nuttall, and Kazantzis Citation2016). In this case, the diagram illustrates the flow from the initiation of an idea or interaction in the breakout rooms through to the reported outcomes of the citizens’ panel process. The diagram was generated using ‘ggsankey’ package in R software based on a paired means test for speaking time duration, frequency and word count for male and female participants. We were also interested to see if the gender of the facilitator influenced the equality in participant interactions and so a means test was also done for the duration, frequency and word count by facilitator. STATA16 was then used to graph the patterns of interactions in terms of duration and frequency for deliberations for each week and breakout session, by gender.

Part two: thematic content

The transcripts were also analysed to assess whether ideas raised were accurately and fully thematised and reported in the Google Docs produced by the facilitators during the breakout room sessions and the interim report produced from the research. An excel spreadsheet was set up with tabs for each activity. The transcripts were examined in parallel with the video recordings to increase accuracy between the different mediums used. When participants contributed an idea, the participant identifier and the theme of the statement was recorded. Each theme was then evaluated for its relevance to the discussion topic. Where deemed not relevant to the discussion (e.g. banter between participants and simple statements of agreement), it was coded as such in a separate column of the spreadsheet. Where the theme from the participant interaction was deemed relevant to the discussion topic it was recorded as relevant and further examined to determine whether it was included in the interim report produced from the citizens’ panels. If the theme was included in the interim report, it was assigned to the report theme/category. Once this analysis was completed the results were further examined to identify the gender of the participant speaking first in each breakout room, and the gender of the participant who first raised the points which were incorporated into the formal reporting. This process allowed the research team to track the generation of ideas, whether they gained enough traction in the discussion to be documented by the facilitator in the Google Docs (and whether finally reported in the interim report), whether they were interpreted accurately, and whether these patterns changed over time during the three weeks of deliberations.

Survey analysis

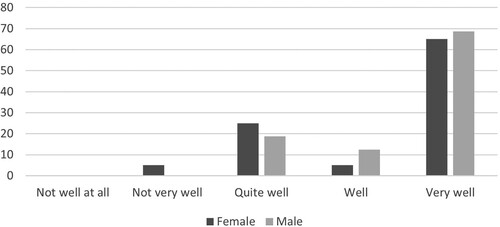

A survey was distributed to the participants providing them with an opportunity to provide feedback reporting on their experience of the deliberative process after the deliberations concluded. Within the post survey, two questions are relevant, where participants were asked to rate their experience along five-point Likert scales:

How did you enjoy your overall experience with this research project? (Responses from ‘not well at all’ to ‘very well)

and

After listening to the presentations and talking to other members of your community, to what extent did you find you changed or broadened your views about low-carbon energy transitions and the possible pathways as a result of this week's workshops? (Responses ranged from ‘not at all’ to ‘to great extent’)

In the next section, we analyse the participants’ overall experience, testing for differences based on gender in participants’ response to the deliberative process.

Results

To examine the research question, to what extent current deliberative methods can achieve fair and equal representation and participation, we have analysed the results in terms of Gastil’s input-process-outcome model. Within the methods section the input component of Gastil’s model has been presented. This results section will now present an in-depth examination on the process component of Gastil’s model to understand the deliberation the equality of representation and the outcome of the deliberation in the alignment of the individual views with the collectively constructed principles and survey results.

Evaluating the components of the deliberation we have broken the analysis into sections covering process and outcomes and the links between the two as follows:

Process - Gender of those speaking during the deliberation

Process - Trends over weeks and topic sessions

Process - Facilitators’ effect on participation

Process - Facilitators’ effect on representation

Link between process and outcome

Outcomes based on participants’ evaluation and

Outcomes based on Principles devised by participants

Process – gender of those speaking during the deliberation

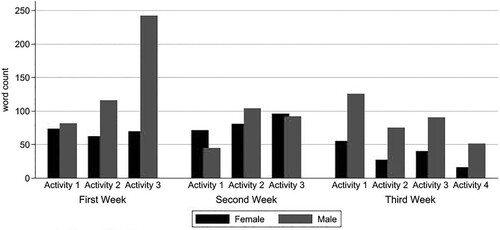

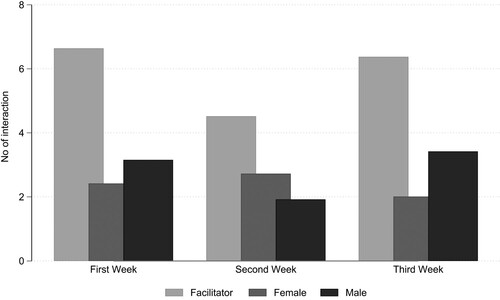

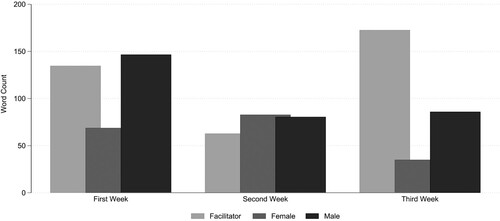

A key part of evaluating the process is understanding the characteristics of the engagement in the deliberation process by gender. Normalised values for interactions by week over the 3 weeks are provided in the three charts ( and contained in this section and Figure 13 in Supplementary Materials). They include the frequency, duration and word count for each interaction. The columns represent the number of interactions and whether a male/female participant or the facilitator was speaking. Note each of these factors are normalised by participant time to account for differences in breakout room duration and number of participants.

Figure 3. The number of interactions (time spoken) each week divided into columns representing the interactions by the facilitator, male and female participants.

Figure 4. The word count for each interaction by week and by facilitator, male and female participants.

Reviewing these trends, we identify the equality of participation in terms of ‘who is speaking’, changes across the three weeks. It shows that the second week is the most equal in terms of the duration of participant speech (Figure 13 in Supplementary Materials) and the number of words spoken during each interaction (). This was also the week the facilitators spoke for the least amount of time, potentially pointing to a smoother discussion between participants. The third week, which required deliberation of the potential decarbonisation pathways, can be identified as both receiving the greatest level of intervention by the facilitators and the greatest differential between participation of male and female participants. A probable reason for the difference is that the participants had more queries relating to the task and so facilitators needed to explain, clarify and reiterate expectations in greater detail. For example:

Facilitator: ‘I was gonna say that's an excellent point. But I think what the question is, that's a really good point that you've made. Thank you for sharing that. But I think the questions we are asking is what would stay the same under this particular pathway?’

Other possible reasons are explored further in the section below.

Process – trend over weeks and context of the discussion topics

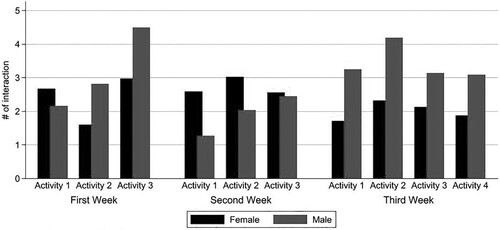

We also looked for trends over time during the deliberations. Hypothesising that levels of engagement and participation may vary with different topics and levels of complexity, participants were asked to perform specific activities. In , we present the questions covered in each week’s activities along with a description of the type of intellectual consideration and discussion required to complete the set activity. and and Figure 14 (in Supplementary Materials) present the results of the analyses.

Figure 5. Number of interactions (times participants spoke) by male and female participants in each activity by week.

Examining the figures, it appears that overall, males tend to talk more and for longer than their female counterparts. While there does not appear to be a recurring trend between subsequent weekly activities and participation, the week 2 deliberations seem to be more evenly spread between genders when compared with weeks 1 and 3. The third activity in the first week shows clear male domination which was also observed in week 3 activities.

When considering the types of questions presented to the participants, several stand out during the first two weeks related to the individuals’ lived experience. The question types and corresponding perceived complexity and difficulty may potentially go some way to explaining the difference in participation levels. The research team observed that due to the complexity of the concepts, participants struggled with the process in the third week. Time constraints imposed for the deliberation were particularly challenging within the online format.

Research has shown that developing a mental picture of a future different from an individual's lived experience can be cognitively challenging (Wade and Piccinini Citation2020). During the third week the participants were provided with details of the characteristics of two separate potential energy futures for Australia. One incorporating future fuels (i.e. hydrogen) and the other all electric (where gas is no longer used for energy). It was extremely challenging for participants to understand the complexity of these potential futures and the implications for daily living; it was equally challenging to consider whether the potential futures aligned well with the principles developed by the participants as a collective. This appeared to challenge the breakout room facilitators to ensure fairness in the deliberation as participants struggled to develop and communicate their ideals for potential energy futures. Notably, it is in this week that we see the greatest discrepancy between genders.

Communicating complex information effectively, such as is necessary when considering potential energy futures, to diverse participants requires further examination considering the criticality of community in a successful climate transition. This can be considered a future area of research in the space of deliberative democracies and social licence. The complexity of a topic should not be used as an excuse to discourage engagement. In fact, complexity (of a topic) should be treated as a challenge that can be supported through facilitated dialogue in order to introduce progressive change.

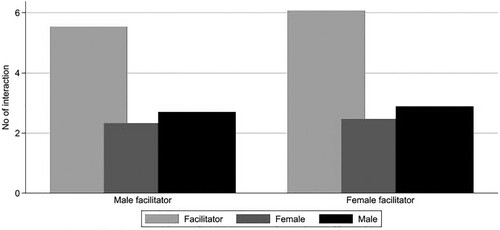

Process – facilitators’ effect on participation

The research team was interested in understanding any potential impact of the facilitators’ gender on process outcomes in terms of equality in participation and representation. To understand the facilitators’ effect, analyses of the number of interactions (), time spoken (Figure 15 in Supplementary Materials), word count (Figure 16 in Supplementary Materials) and facilitators’ gender were undertaken. There were only small differences in the gender representation within the breakout rooms between the male and female facilitators. However, we observe that the female facilitators spoke more often during the discussion process and for longer periods of time. Given the sample size of seven facilitators (four females and three males) is small, these differences may be due to other factors outside the scope of our analyses, but the facilitator trends are further explored in the next section examining who is setting the agenda.

Process – facilitator effect on representation

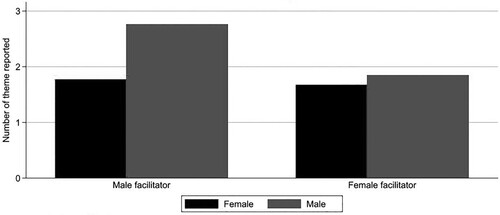

The results above have considered the interactions in the breakout rooms with some reference to the content (see Sections ‘Method’ and ‘Input’) of what was being discussed. When considering the representativeness of the citizens’ panels, the outcomes of the deliberative process ought to be shaped by views of all participants equally. To test whether all genders were equally represented, Figure 17 (in Supplementary Materials) and explore how participants lead the discussion. Figure 17 (in Supplementary Materials) examines who initiated meaningful conversations and whether any gender biased patterns exist. presents the number of themes reported. It was observed that participants in the breakout rooms initiated 239 meaningful conversations, of which females started 53 per cent (134 out of 239) of the conversations.

To understand these figures in context we have normalised them by the number of female participants. Due to the larger number of females present in the discussions, based on the higher dropout rates of male participants over the course of the deliberations, we observe that although the female participants are contributing more of the overall conversations, each female started only 0.92 meaningful conversations compared to 1.04 for males.

Figure 17 (in Supplementary Materials) shows that in sessions facilitated by males, the male participants tended to dominate the start of conversations whereas in sessions facilitated by females, both male and female participants are almost equal in their participation. Specifically, in sessions facilitated by males, each female participant is likely to start only one conversation whereas for male participants it is almost 1.31. In sessions facilitated by females, each male and female are likely to start 0.9 meaningful conversations. This suggests that the female facilitators may have been able to promote equal participation from the start.

Examining the results in , we observe the frequency of themes emerging from male and female participants which were included in the summary report. For sessions facilitated by males, of the themes that were included in the summary report, 1.8 of the themes emerged from female participants compared to 2.7 of themes raised by male participants. For sessions facilitated by females, of the themes reported in the summary, 1.6 and 1.8 (emerged from female and male participants, respectively). This provides interesting considerations around the gender of facilitators and their effect on participants’ interaction and the subsequent analysis. It also suggests that there may be a role for training facilitators to help them to avoid any biases and ensure the opportunity for more equal participation.

Linking process to outcomes – summary of results in Sankey diagram

presents a Sankey diagram that illustrates how the various exchanges flowed amongst participants during the deliberation sessions. Each breakout room session where deliberation occurred is considered as the unit of analysis. The x-axis depicts five variables – ‘room profile’, ‘interaction’, ‘discussion’, ‘initiation’ and ‘impact’. To measure the ‘room profile’, the proportion of females in each room was calculated. To measure ‘interactions’, the proportion of dialogues spoken by females was calculated against the total number of dialogues spoken by all participants. To measure ‘discussion’, the proportion of female word counts was measured against the total session word counts. To measure ‘initiation’ the proportion of first female-led thematic content was measured against all thematised content. This measure was introduced since the first two measures (interaction and discussion) took into account a vast array of ‘noise’ – that is naturally generated by small talk, social niceties, off-topic conversation and so on. Lastly, to measure ‘impact’, the proportion of female-led themes included was measured against the total number of themes reported.

In , the y-axis classifies the sessions into four types, each denoted by the numerals ‘1’, ‘2’, ‘3’ and ‘4’. As shown in the legend, ‘1’ signifies the proportion of sessions with up to 25 per cent females; ‘2’ signifies the proportion of sessions with 25–50 per cent females; ‘3’ signifies sessions with 50–75 per cent females and ‘4’ signifies sessions with 75–100 per cent females. During the panel sessions participants were not pre-assigned to individual breakout rooms as there was no way of predicting who would show up for the actual session. It was deemed prudent to assign participants to breakout rooms on a first come, first served basis based on Zoom’s operational logic. Hence, there was some variation in the ratio of females to males in each breakout room, exacerbated by the drop in male participants over the course of the weeks.

From the Sankey diagram, the following results are evident:

Room profile: Although the operational logic of participant assignment may not have been ideal, the proportion of sessions with equivalent number of males and females (‘2’, and ‘3’) were the largest. The sessions where there were mostly men in a session (‘1’) was of the smallest proportion, with more sessions containing mostly female participants (‘4’).

Interactions: The highest proportion of dialogues was spoken in sessions of type ‘2’ (where there were 25-50 per cent females), while the sessions of type ‘1’ and type ‘4’ generated the lowest frequency of dialogues.

Discussions: The highest proportion of word counts were measured in sessions of type ‘2’ and the least proportion of word counts were measured in sessions of type ‘3’. An equivalent proportion of word counts was measured in sessions of type ‘1’ and ‘4’.

Initiation: In sessions of type ‘2’, the proportion of female-led meaningful conversations was evenly balanced notwithstanding room-profile. The grey bar in initiation and impact indicates the number of voting sessions in the third week where no new theme was discussed.

Impact: The maximum portion of themes reported in the interim reports arose from sessions of type ‘2’. The grey bar in initiation and impact indicates the number of voting sessions in the third week where no new theme was reported.

These results contained in the Sankey diagram help to answer the question whether the female contribution was lost in the deliberations. Despite the highest number of sessions being comprised of more females, males contributed more than half of the interactions in the majority of sessions. This suggests that despite being in the minority in the breakout rooms, male participants gradually dominated the process as evidenced by the increasing number of sessions with most contributions from males. However, overactive participation does not imply a high level of influence on the reporting, providing facilitators actively engaged in gatekeeping tasks, whilst the sessions were live.

The distribution of flow from one node to another shows a female dominated room contributes to female dominated interactions and discussion, leading to a female-dominated outcome. However, the difference in contribution is not so stark for initiation and impact. Despite being in a minority in terms of the room profile (input), male participants may still dominate the process (interaction, discussion and initiation) and influence the outcome (theme reported to summary). Further examination of the Sankey diagram suggests there is evidence of the facilitators within the breakout rooms actively intervening, through facilitation, to achieve their goal of equal participation and impact. This is made visually clear through the similar size of tabs for the breakout room sessions in the interaction and impact columns. The results from Figure 17, and also suggest that the facilitators’ effectiveness differs based on their genders, despite each facilitator being granted the same level of training.

Outcome – participants’ evaluation of the process through a self-reported survey

To query whether participants’ themselves picked up on any bias during the deliberations and whether perceived bias impinged upon their experience of the deliberative process, two questions from the post-survey were analysed for a difference in response based on gender. shows that when participants were asked how they enjoyed their overall experience, a majority of participants (both male and female) conveyed that they enjoyed the experience ‘very well’ – in support of their satisfaction with the overall deliberations. However, a small percentage of females selected the option of ‘not very well’, justifying the need for deeper analyses presented upto this point.

shows that after the end of week 3, more females than males reported that they changed or broadened their views ‘to a fairly great extent’ (55 per cent females vs 19 per cent male) and ‘to a great extent’ (40 per cent females vs 25 per cent males). This result suggests that in week 3, although it was noted previously that male voices predominated, majority female participants (55 + 40 = 95 per cent) reported a change or broadening of views on low-carbon transition and possible pathways! It is a telling result that 95% women (vs 44 per cent male) indicated a change in views (to a great and to a fairly great extent) indicating the powerful effect deliberation and dialogue can have on outlook, even though the subject matter is complex with many technicalities involved.

Outcome – principles devised by participants

Through the deliberation participants from Greater Melbourne successfully formulated eight principles to guide the path to a low-carbon energy future for Australia (Ashworth et al. Citation2021a, 28). Three principles with highest agreement with the statement that the principle ‘represents my view well’ are shown below. Remaining Principles, with percentage of participants agreeing are shown in .

Table 5. Remaining principles developed by the Greater Melbourne panel.

Principle 1 (100 per cent agreement represents views well): Every person has the right to safe, reliable and affordable energy supplies that are supported by fair tariffs and rebates. Therefore, all Australians should have reliable, guaranteed energy when they need it and at a price they can afford.

Principle 2 (85 per cent agreement represents views well): The implementation of new low-carbon energy technologies should be based on scientific research, education and supported by government and industry funding.

Principle 3 (85 per cent agreement represents views well): The new energy technologies should be safe to produce, consume and dispose of in comparison to the current technology.

Principles 1-3 received alignment scores of 85 per cent. Five of the eight principles received voting scores between 65-76per cent (). To understand why Principles 4-8 () have less agreement than others, it is necessary to examine the process component of Gastil’s model more deeply. Examining the recordings and transcripts we gain a deeper understanding of who is speaking, the trends over weeks and discussion topics, facilitator effects on participation and gendered facilitator effects on representation. Further elucidating Gastil’s ‘process’ component the sections below explore the interactions of the participants in their discussion as they develop the principles. We then evaluate the implications for Australia’s energy future.

Discussion and implications – how to handle the ‘process’ in deliberative processes

Organisations are being increasingly scrutinised and compared based on their ESG performance by regulators, suppliers, investors and clientele alike. The outcomes of which can directly influence their SLO and perceptions of legitimacy and fairness around engagement. Performance and reporting measures of ESG often include measures of the quality of engagement and relationships with a range of different stakeholders. In terms of engagement, providing opportunities for two-way dialogue is generally recognised as being of higher value than providing unidirectional information about organisational practices or decisions only. Hence why deliberative processes, such as citizens’ panels, can be an effective way of engaging with stakeholders and thereby further demonstrating an organisation’s commitment to ESG principles, particularly where organisations are prepared to listen, accept and act on the views of their stakeholders. For example, Principles 1-3 narrated in the results section (see also Ashworth et al. (Citation2021a, 28) , offer an indication of what appeals to participants as a collective when they deliberate upon a low-carbon energy future for Australia – reliable energy, collaboration, safety, equitable and affordable energy services. Lee and Romano (Citation2013, 750) remarked that ‘reframing of organisations as co-equals with movement actors may be an organisational strategy itself’. However, for the outcomes of such deliberative processes to be deemed credible enough for an organisation to commit to action, it is important to ensure that the deliberative processes enable equality in both representation and participation.

We identified the facilitator as being challenged to co-create the deliberative process in a way that equal participation is encouraged, through and through. Practice can remove itself from ideals, despite the best of intentions. Our analyses of the Greater Melbourne citizens’ panel process indicate that despite detailed attention to gender representativeness in the planning and recruitment stages, equality in both representation and participation is a challenging goal. The results suggest how gender norms persist within online Australian society and can creep into deliberations but can be managed well if facilitators are trained in recognising how those gender norms operate. Such training and subsequent facilitator action can ensure that gender norms despite being present, do not impinge upon outcomes in any negative way. Challenges related to the issue of gender inequality emerged in some breakout room deliberations, based on the observations during our secondary review, that some male participants possessed the more dominant voices within the breakout rooms. Additional challenges arose in how facilitators interpreted and captured individual participants’ ideas to form the collective view. Dialogue appears to have been differently managed by male and female facilitators. Fujimoto, Azmat, and Subramaniam (Citation2019) explain that inclusion operates at multiple levels (individual, relational, collective and structural). Further they explain that inclusion is a multidimensional (role of givers, beneficiaries and other stakeholders) concept, which involves personal empowerment (despite gender differences), relationship building, resource exchange and structural governance facilitated by those who include (e.g. the organisation) and those who are included (e.g. minority members). Thus, even in Australia, where equal opportunity is a core value, gendered communication and gender norms play out in deliberative processes. If managed well, gender norms may not compromise inclusion nor influence outcomes negatively. Our results assert that organisers of future deliberative processes need to consider that when facilitators are recruited, they are also trained to be mindful of gender norms and how they operate in online settings. Male and female facilitators may require training in how to feminise an online setting if gender norms are seen to exclude women (and vice versa, depending on what case is evident). Offering extra support to facilitators to manage gender norms as they play out, while the process is live, will serve to enhance outcomes, minimising bias and check for representation in both the process and in the outcomes. In short facilitation training, quality of facilitation and engagement must be carefully monitored at all times. Where possible extra resources must be deployed to offer iterative feedback to facilitators while the process is still running.

Notwithstanding the effects of gendered communication, a critical performance measure in ESG evaluation is how an organisation positions itself in terms of its response to climate change and moving to net-zero emissions. Engagement around future-focused organisational behaviour and change (such as the energy transition) requires pre-emptive, rather than reactive, or ‘after the decision has been made’ stakeholder engagement. This type of stakeholder engagement, especially where the adoption or endorsement of new technologies is required, means engaging stakeholders in a co-learning exercise. This allows both stakeholders and the organisation to gain a better understanding of the change that is required. They can then seek to co-design pathways that are both mutually beneficial and more acceptable, ultimately leading to greater perceptions of fairness in the process and genuine interest by the organisation in what their consumers think. In the academic literature such engagement and activities can help to enhance an organisation’s SLO.

The results of our research are therefore highly relevant to organisations pursuing net-zero emissions and ESG targets in that it provides a nuanced understanding of the less obvious challenges associated with fostering quality in deliberations. Enhancing the quality of deliberations is particularly crucial in avoiding energy transition pathways that create uneven burdens of costs, safety, and social and environmental impacts. For example, with the introduction of hydrogen or renewable energy into existing systems, understanding how to conduct equitable deliberations is relevant to organisations involved in implementing new energy technologies as well as those stakeholders affected by the projects. This was evidenced by the interest in the results of the panels by industry and government organisations involved in the research centre which funded the research. There has also been direct evidence of some organisations utilising citizens’ panels to engage consumers in their policy resets. The results also offer insights to academics with an interest in deliberative processes and stakeholder engagement.

Based on our analyses in relation to participation and representation, we present four key propositions for consideration when using citizens’ panels as a form of stakeholder engagement and for consideration when working with Gastil’s model of deliberation.

Proposition one: equality in participation and representation is challenged by norms and cultural patterns (i.e. gender-related) meaning that purposeful process planning and mindful facilitation are required.

The case study is from Australia, a country with high levels of education, where everyday people aspire to the ideals of equality and having a ‘fair-go’. Higher education levels could be understood to correspond with increased confidence in knowledge and an expectation is that the ability to participate in deliberation would increase as a result. Results of this research, however, indicated that gender differences are present in deliberations (Sankey diagram, ). However, these differences did not negatively impact participants overall enjoyment of the process (). When asked, majority male and female participants responded that they enjoyed the overall experience, ‘quite well’ or ‘very well’ ().

When gender differences arise, some authors propose that gender homogenous groups are required to maximise individual participation by women (Karpowitz, Mendelberg, and Shaker Citation2012). However, based on our results, mixed gender groups were successful despite some differences creeping through where certain male voices dominated. However, even though some voices dominated the discussion, other participants switched to listening, absorbing and processesing what was being said. In future research with Australian samples, however, facilitators must remain mindful that male and female participants are equally involved. Where possible, facilitator training must include modules on how to balance participation and how to intervene if dominant voices are seen to negatively influence other participants’ experience.

More significant was the gender of the facilitator. In ensuring equal representation of women, female facilitators tended to capture the ideas initated by men and women more equally than male facilitators. Male facilitators were more likely to capture the views initiated by men. This suggests consideration should be given to balancing gender of participants in mixed groups. Where gender balance is not possible, a female facilitator is recommended if fairness in outputs is being sought. In the case of mixed gender groups with a male facilitator, male facilitators must make a conscious and assiduous effort to make note of and encourage female participants’ input.

In certain societies, it may also be prudent to achieve representation by designing deliberative processes that contain small groups based not on a statistically representative sample, as is generally the case, but on homogenous groups of stakeholders, such as women, youth, language groups, etcetera to ensure their voice is accurately captured in the collective voice of the formal outcomes (as in Gastil’s model in and Figure 12). Other diversity-related considerations such as age and ethinicity may also be relevant but are outside the scope of this article.

Proposition two: holding panels online rather than face to face has the potential to increase access for some participants, however, participation and representation is not assured.

There are several trade-offs that emerged due to moving the citizens’ panels online. Digital participation does allow greater opportunities for some (Trittin-Ulbrich et al. Citation2021), such as those who can potentially not travel or dedicate whole days to attend face-to-face panels, or those who just find it easier not to leave the house for operational purposes. However, for those who do not have a stable internet connection full participation can be significantly limited. Sometimes, participants were forced to turn their videos off to allow for a more stable connection in our study. Further, although some individuals are confident in the use of online discussion forums, for others it can challenge interpersonal communication as evidenced by Braun et al. (Citation2020, 683) who suggest that

Even if an ‘inclusive’ approach is adopted, actual participation remains a matter of negotiation between researchers and research process participants, and an online setting might change the terms.

The impacts of COVID-19 and related issues of vaccination status further complicated participation in face-to-face processes which may make online deliberation more attractive. During the active period of COVID-19 management while most governments had strict rules in place for managing in person interactions, a divide emerged across society between those who were vaccinated and those who were not. In these instances, online engagement could effectively ‘open up’ opportunities to participate. In doing so it allows more opportunity to include a wider cross section of society, including those potentially more marginalised. Nevertheless, in the business context, digitalisation may enable internal and external stakeholders, including employees, activists, and consumers, to monitor and become more actively involved in corporate concerns (Trittin-Ulbrich et al. Citation2021).

Proposition three: equal gender representation through attendance in deliberative processes does not ensure equal representation in participation. Other factors such as facilitator management should be considered to promote equality.

Guidelines for successful representation in deliberative processes discuss sampling strategies for representation and state that representation can be successfully achieved by either recruiting participants to align with relevant demographic statistics, and/or to recruit participants that would represent diverse perspective (OECD Citation2020). In this study, we undertook to do both by sampling according to key demographics and with likely different experiences of energy transition based on the location of their habitat. However, despite fitting the OECD (Citation2020) criteria for ‘successful representation’ in terms of participation, group dynamics and social influences have operated within the deliberation process that have resulted in inequalities in terms of representation in voice and impact on the outcomes. We have shown that representation in attendance in deliberative processes does not ensure representation in participation or voice. A basic assumption is challenged – having equal (or statistically aligned) numbers of male and female participants does not necessarily translate to equally representative views. Our results show that it is possible to have a statistically representative sample but still have inequality in terms of representation in outcomes.

Proposition four: differences in dialogue and inclusion may be exacerbated by the content of the deliberation. Communication strategies for complex information need to be carefully developed to meet participant knowledge assimilation styles.

The gender differences found in this study may have been exacerbated by the highly technical nature of the engagement topic: Australia’s current and future energy systems and the role of future fuels. Studies in gendered communication have found that men will initiate and favour conversations that contain facts, data and aim to solve problems, whereas women tend to use more emotive language and personalise or socialise the problems being discussed (Kelan Citation2007). This was evidenced during week two where women tended to be more active when reflecting on their own lived experiences while men were more likely to initiate and dominate conversations when deliberating on the technologies. In addition, the strict time limits for breakout room deliberations may have contributed to women having less impact on the outcomes, if they were using wordier, personal experiences such as the one below, to make their point:

Because it starts from there. My building’s only 22 years old. You know. So I mean, if you start from the building and work up, but as I say, you know, I'm in an apartment, and I asked the question, why haven't we got solar panels? Yeah, you know, and a new building. And when we're in 2020, 2021 and it shouldn't, should have been done. You know what I mean? … People can't use common sense. And that's that's the sad part.

Limitation of study and scope for future research

Conducting deliberations via the online platform presented some challenges and frustrations as well as potentially limiting the scope of the final analysis in several ways. These challenges included the interactive methods of data-gathering and deliberation as well as collaborative research management meetings (Braun et al. Citation2020). We recognise that although holding a panel online may facilitate the inclusion of some individuals who would not usually be able to participate, it prohibited individuals without reliable internet access or without the knowledge of computers or confidence to navigate the online process.

Furthermore, online processes may inhibit some participants from fully participating in the discussion particularly based on their gender, as females often prefer time to interact and share their personal experiences, a challenge when time can be strictly limited when using breakout rooms and online engagement. This has been reflected in questions remaining over equality considerations of online interviews and discussions versus face-to-face activities and requires future research (Otto Citation2021). Keeping in mind these limitations, practitioners are asked to consider their own deliberative proceses in stakeholder engagement to ensure that all participants’ experience and inclusion is carefully planned and managed, being mindful of how gender norms (amongst other social norms) play out in their societies. Paying attention to such aspects in advance, that is while planning and designing the research process, may produce more evenly balanced outcomes at the end as we explain below:

Deliberations, inequalities and the role of the facilitator in feminising the setting to encourage women’s participation

In western cultures, it has been acknowledged that females, while considered more sociable than men, are less likely to proactively voice their opinions in formal settings, particularly if it has a political overlay (Karpowitz and Mendelberg Citation2014; Martinez-Palacios and Ahedo Citation2020). Although one may argue that gender inequality has been a long-term structural issue across multiple societies, the extent to which this occurs can also differ by country and culture (Levy and Sakaiya Citation2020). There have been several studies that have attempted to identify if differences exist between gender participation in both face-to-face and online engagement activities. These have included examining the time spent speaking and comparing the proportion of time spoken between male and female participants (Karpowitz and Mendelberg Citation2014), levels of influence over the topics discussed by each gender, with others examining the frequency and length of messages written by females compared to males (Polletta and Bobby Chen Citation2013). While the findings of many of these formal studies have been inconclusive – with various reasons provided for the differences in findings – they point to the key role a facilitator, mediator or even ‘curator’ of deliberative processes can play. It has been known that when the institutional setting is feminised – where emotional expression and empathetic listening are emphasised over technical analysis and adversarial argumentation – women’s participation is encouraged (Polletta and Bobby Chen Citation2013). Through our analysis, we have identified how gendered facilitation plays out in structuring everyday conversations in an Australian case. In future cases of Australian online deliberations, processes need to be designed in a way that the online settings convey feminine values to encourage more women to participate, specially so in cases where male voices are seen to dominate. Facilitators’ training and experience in emotional expression and empathetic listening may be key in enhancing level and balanced outcomes in such cases as participants themselves may not perceive or report any experience of bias.

Naturally occurring conversations that take place in structured discussions, leverage group etiquette and dynamics (Krueger and Casey Citation2015). By examining what happens in deliberative processes through the lens of gender norms, significant improvements in citizens’ panels methodologies for stakeholder engagement are indicated, within an Australian context. This applies to design and execution of the citizens’ panels as well as for assessment of their outcomes. For Australian organisations who are interested in using citizens’ panels’ as a methodology for stakeholder engagement, above-listed findings offer ways of improving fairness and equality in participation and representation.

Conclusions

With the urgent need for decarbonisation, governments and organisations around the world are having to transform the way they produce and use energy. For those in the energy sector, the transition implies a need to engage with a range of stakeholders – from local project community hosts through to a range of end user consumers. When engagement processes are designed to ensure fairness in participation and representation, it will lend greater legitimacy to the engagement process and also support a project’s SLO. Finding effective ways to ensure efficiency and rigour in the process whilst fairly including affected stakeholders and providing enough time for stakeholder views to be heard can be a challenging task. Deliberative processes allow room for all the above to occur. Therefore, there is merit in relying on citizens’ panels to engage around the difficult topic of energy transition and other complex matters to co-design decarbonisation pathways that are mutually beneficial and more acceptable to all stakeholders involved.

In this research, the citizens’ panel process was used to investigate what participants considered would be the role of future fuels in Australia’s low-carbon energy mix. Impacted by COVID-19, the panels took place online with attention focused on ensuring a representative sample of participants. Facilitators were used to keep the deliberations on track, and a good mix of small and large group interactions included to allow for the diversity of participant views to be heard across the engagement.

While holding panels online resulted in some benefits, it also presented several challenges. Not least of which was the influence of gender in interactions and whether this ‘opened up’ or shut down the range of participants’ views. It appears from our analysis, that despite striving to allow fairness in the process of deliberation, gender norms persisted. While not overly skewed, in many of the sessions it appears that males tended to talk first, more often and were more confident in discussing the topics surrounding future fuels. Our results suggest that the presence of female facilitators can be effective at reducing gender bias in smaller groups. This has important implications when using deliberative processes to engage with stakeholders in a fair process as well as ensure all participants are given a ‘fair go’ in expressing their views. The information gleaned through such a dialogic process demonstrates that citizens’ panels provide an effective methodology for both sharing information and tracking responses, both individually and as a collective.

Declaration of interest statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Future Fuels Cooperative Research Centre under the Research Program 2 Social Acceptance, Public Safety and Security of Supply project RP2.1-07 Deliberative engagement processes on the role of future fuels in the future low-carbon energy mix in Australia. Ethics approval was sought and obtained prior to commencement of work (Approval number: 2020/HE002473).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ashworth, P., A. Littleboy, P. Graham, and S. Niemeyer. 2010. “Turning the Heat On: Public Engagement in Australia's Energy Future.” In Renewable Energy and the Public: From NIMBY to Participation, edited by P. Devine-Wright, 131–147. Earthscan.

- Ashworth, Peta, Svetla Petrova, Kathy Witt, Belinda Wade, Bishal Bharadwaj, Elliot Clarke, Katie Meissner, and Amrita Kambo. 2021a. Citizens’ Panels on the Role of Future Fuels in a Low-Carbon Future Energy Mix in Australia. https://www.futurefuelscrc.com/wp-content/uploads/FFCRC-2.1-07-Citizens-panels_Interim-report_final-web-1.pdf.

- Ashworth, Peta, Svetla Petrova, Kathy Witt, Belinda Wade, Bishal Bharadwaj, Elliot Clarke, Katie Meissner, and Amrita Kambo. 2021b. Technical Appendices: Citizens’ Panels on the Role of Future Fuels in a Low-Carbon Future Energy Mix in Australia. https://www.futurefuelscrc.com/wp-content/uploads/FFCRC-RP2.1-07-Citizens-panels_Technical-appendices-web.pdf.

- Australian Bureau of Satistics. 2016. “Greater Melbourne: 2016 Census All Persons QuickStats.” https://www.abs.gov.au/census/find-census-data/quickstats/2016/2GMEL.

- Australian Government. 2021. “Australian Values.” https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/about-us/our-portfolios/social-cohesion/australian-values.

- Hurst B., and Ihlen Ø. 2018. “Corporate Social Responsibility and Engagement.” In The Handbook of Communication Engagement. Online edition, edited by K. A. Johnston and M. Taylor, 133–147. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119167600.ch10.

- Bächtiger, André, John S. Dryzek, Jane Mansbridge, and Mark E. Warren. 2018. “Deliberative Democracy: An Introduction.” In The Oxford Handbook of Deliberative Democracy, edited by André Bächtiger, John S. Dryzek, Jane Mansbridge, and Mark E. Warren, 1–32. Oxford University Press.

- Bakenne, Adetokunboh, William Nuttall, and Nikolaos Kazantzis. 2016. “Sankey-Diagram-based Insights into the Hydrogen Economy of Today.” International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 41 (19): 7744–7753. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2015.12.216.

- Batel, Susana, and Patrick Devine-Wright. 2015. “Towards a Better Understanding of People’s Responses to Renewable Energy Technologies: Insights from Social Representations Theory.” Public Understanding of Science 24 (3): 311–325. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662513514165.

- Batel, Susana, Patrick Devine-Wright, and Torvald Tangeland. 2013. “Social Acceptance of Low Carbon Energy and Associated Infrastructures: A Critical Discussion.” Energy Policy 58: 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2013.03.018.

- Braun, Robert, Vincent Blok, Anne Loeber, and Ulrike Wunderle. 2020. “COVID-19 and the Onlineification of Research: Kick-Starting a Dialogue on Responsible Online Research and Innovation (RoRI).” Journal of Responsible Innovation 7 (3): 680–688. https://doi.org/10.1080/23299460.2020.1789387.

- Brueckner, Martin, and Marian Eabrasu. 2018. “Pinning Down the Social License to Operate (SLO): The Problem of Normative Complexity.” Resources Policy 59: 217–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2018.07.004.