ABSTRACT

Borders are sites of mass injury. This article questions the necro-consensus that has emerged within migration studies, and explores the political role that less-than-deadly violence plays at contemporary borders. By withholding from outright killing, and thus avoiding the optics of public scrutiny, EU states are deploying a carefully calibrated politics of injury designed to control racialised groups through debilitation. The injuries produced through this border regime—typified by illegal ‘pushbacks’ and deplorable camp conditions—exist beneath a threshold of liberal acceptability. In short, EU states routinely deny the right to asylum by imposing the ‘right to maim’ (Puar 2017). This article draws upon long-term research along the ‘Balkan Route’ in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia, including interviews with medics, activists, EU officials, and people on the move, as well as analysis of a large border violence database. We argue that mass injury has become a politically tolerated form of violence that perversely provides the EU with the illusory conceit of humanitarian “care”. In dialogue with postcolonial scholarship that has questioned the centrality of death within biopolitics, we assert the importance of interrogating not only the necropolitical logics of migration policy (i.e death), but also the politics of non-lethal violence: the strategic and attenuated delivery of injury, maiming, and incapacitation that shapes contemporary borders. Contributing to geographies of violence and critical border studies, we suggest that greater attention is needed towards less-than-deadly harms that underpin contemporary political geographies.

Introduction

‘They hit me on the backbone’ said one man, leaning over to reveal a series of red and purple bruises on his spine. Another refugee, a one-armed teenager who had been severely disfigured two years prior from a landmine explosion in Afghanistan, was rummaging through a pile of donated clothes for a replacement pair of trousers. His current pair, he explained, was clinging too tightly to his pre-existing leg-wound, which had been violently re-opened the night before by Croatian police during his forced-removal from the EU: ‘I tried to show them this…’ he said, carefully rolling up his trouser leg to reveal his injury: ‘…but they kept hitting.’ (Fieldnotes, Bosnia, July 2019.)

Outside an abandoned abattoir in northwest Bosnia, less than a mile from the external land-border of the European Union (EU), a group of men and women wait in line for a volunteer nurse to treat their wounds. In the border town of Velika Kladuša it was not unusual to meet people on the move (POM) wearing bandages. Some needed treatment for skin infections, which they had contracted in the overcrowded squats and camps nearby. Others described foot injuries, full body pain, and swollen ankles from doing ‘the Game’ – the sardonic nickname participants used to describe their perilous attempts to reach asylum inside the EU (Augustová, Carrapico, and Obradović-Wochnik Citation2021; Isakjee et al. Citation2020). For thousands of people taking the so-called ‘Balkan Route’ to Europe, ‘playing’ the Game involves travelling undetected across miles of sparsely populated, rugged terrain, through a largely bucolic borderland.

Entry into the ‘safe haven’ of the EU often involves the systematic and widespread deployment of injury and debilitation. Most of the people seeking treatment from the volunteer nurse had recently been physically assaulted by Croatian police during unlawful ‘pushbacks’ from EU territory (see Augustová, Carrapico, and Obradović-Wochnik Citation2023; Davies, Isakjee, and Obradovic-Wochnik Citation2023). In a pattern repeated throughout this ethnographic research – which took place in Bosnia and Serbia near the EU border – the injured pushback survivors had been denied due process to claim asylum while inside the EU, in violation of multiple international conventions designed to protect the fundamental rights of refugees. In this way, the border is not just a political division of space, but an ordeal of direct and slow violence, where the questionable safety of the EU is only accessible if one risks considerable exposure to injury.

The word ‘injury’ stems from the Latin term iniuria meaning the opposite [in-] of justice [iuris]. As such, to be injured not only signals exposure to damage, it also implies being wronged in a fundamental sense. The Anglo-French word injurie (14c), meaning a ‘wrongful action’ gives the contemporary term efficacy in highlighting harm or loss. Here, injury helps attend to the ontological injustice of contemporary borders as key sites of wrongdoing. In this article, we focus on the geographies of injury that help sustain the borders of liberal European states, and suggest greater attention is needed towards the less-than-deadly harms that underpin contemporary political geographies.

By centring the multiple acts of maiming used against the infrastructures, bodies, and environments that people inhabit along the border of the EU, and in dialogue with postcolonial scholarship that has sought to move beyond the dominant focus on death (Puar Citation2017; Sparke Citation2017), we explore the critical role that injury plays in the management of excluded populations. By focusing on the non-lethal harm that people are exposed to, we argue that injury forms a deliberate, calculated, and routine biopolitical action that attempts to securitise the EU’s external border. By deliberately not ‘letting [asylum seekers] die’ (Foucault Citation1978), injury becomes a politically tolerated form of violence that simultaneously provides the EU with the illusory conceit of humanitarian ‘care’: the mass production of injured bodies at the EU border – through the targeted maiming of pushbacks and the slow debilitation of deplorable living conditions – creates a political ecosystem into which EU-funded humanitarianism becomes an outwardly benevolent necessity.

Along the land borders of the EU, biopolitical control does not primarily manifest itself through the purposeful production of death, or the fatal threats of ‘necropower’ (Foucault Citation1978; Mbembe 2019). Instead, it is systematic debilitation that forms the central apparatus of control and coercion of racialised groups. Injuries, cuts, contusions, bruises, blisters and wounds are the dominant way that the biopolitics of the border are embodied and expressed. Away from the mass drownings across Europe’s maritime peripheries, we argue that the EU’s borderscape is enforced through what Jasbir Puar called ‘the right to maim’ (Citation2017), where racialised subjects are not expressly killed by sovereign powers – or even ‘let to die’ (Foucault Citation1978) – but are instead rendered ‘available for injury’ (Puar Citation2017, 128). As our empirical investigation shows, displaced people along the border, having been ‘preordained for injury and maiming’ (Puar Citation2017, 65), are not only incapacitated through exposure to physical assault – they are also made available to the injurious violence of a wider EU strategy that produces spaces of debilitation.

To make this argument, we draw upon ethnographic fieldwork with people who are attempting to navigate the so-called ‘Balkan Route’ into the EU through countries including Serbia and Bosnia, as well as in-depth interviews and participant observation with medicks, border violence monitors, local volunteers, and pushback survivors. This research took place across multiple periods of fieldwork in Serbia and Bosnia between 2017 and 2023. We also analyse government press releases, policy documents, and border violence reports, as well as elite interviews with state actors, NGO representatives, and supranational officials in Sarajevo, Belgrade, and Brussels.

Killing and Letting Die

Critical geographers and allied scholars regularly use the idea of biopolitics to analyse the contemporary governance of forced or irregular migration (see Amoore Citation2006; Conlon Citation2010; Sparke Citation2018; Tazzioli Citation2019). As Foucault made clear (Citation1976; Citation1978), biopolitics includes the deployment of power to safeguard, manage, and regulate the lives of populations considered ‘legitimate’ by sovereign authorities. As such, a repertoire of administrative, legal and managerial techniques can be used to exclude unwanted people, routinely reaching beyond the normative geographies of the nation-state itself.

In his historical analysis of biopolitics, Foucault described how pre-modern biopower was characterised by ‘the right to take life and let live’ (Foucault Citation1978, 136). In this proto form of biopolitics, first contemplated by a English philosopher Locke ([Citation1690] 1980, the state’s authority would ‘display itself in its murderous splendour’ (Foucault Citation1978, 144), through the spectacular violence of massacre or summary execution; or, conversely, the sovereign would exercise its power ‘by refraining from killing’ (ibid, emphasis added). In more modern times, according to Foucault (Citation1976, Citation1978), contemporary states shifted their modality of biopower from such palpable displays of ‘make die’ harm, to more subtle ‘make live and let die’ forms of control (Foucault Citation1976, emphasis added). Put simply, unwanted populations are allowed to perish by the ‘withholding of the means of life’ (Davies, Isakjee, and Dhesi Citation2017, 1281).

In the context of migration and border governance today, scholars have highlighted this callous politics of ‘letting die’ across a growing gamut of political geographies: from the state-sanctioned abandonment of asylum seekers to the possibility of drowning in the Mediterranean Sea (Cuttitta, Häberlein, and Pallister-Wilkins Citation2019; Danewid Citation2017; Kovras and Robins Citation2016) or the English Channel (Davies et al. Citation2021), to the closure of seaports available to rescued refugees (Cusumano Citation2019); and from the desertion of migrants to the lethality of the Sonoran Desert on the US–Mexico border (Doty Citation2011; De León Citation2015; Squire Citation2017), to the deadly denial of medical treatment to displaced people along the borders between India and Bangladesh (Shewly Citation2013). As such, death often remains the dominant active ingredient in contemporary biopolitical framings of forced migration: a lightning rod for academic discussion about the workings of biopower.

The Necro-Consensus in Migration Scholarship

Much critical scholarship on biopolitics, originating with Foucault, pivots on depicting biopower as a toggle between the primary extremities of death and life. As Mbembe (2019, 66) described in his book Necropolitics: ‘the ultimate expression of sovereignty largely resides in the power and capacity to dictate who is able to live and who must die’. Critical geographers have been similarly ‘wedded to the poles of living and dying’ (Puar Citation2017, 137). Drawing on substantive empirical work, a growing chorus of migration scholars frequently emphasise the ‘fatal interruptions’ (Lo Presti Citation2019, 1348) of migrant mobilities, where refugees are either described in Agambian terms as ‘bare lives’ (Agamben Citation1998; Darling Citation2009; Doty Citation2011; Schindel Citation2022); or positioned, following Mbembe (2019), as inhabiting neo-colonial ‘death worlds’ (see Davies and Isakjee Citation2019; Mayblin et al. Citation2020; Round & Kuznetsova Citation2017). Fatality, in other words, has become central to how we think about border governmentality: a necropolitical norm through which migration is managed.

We see this in descriptions of ‘thanopolitical borders’ (Vaughan-Williams Citation2015, 45), as well as the prolific uptake of the prefix ‘necro’ within critical migration literature: from rescasting migrants as ‘necro-figures’ (Last Citation2020, 30); to describing the ‘necrogeography of the borderscape’ (Stümer Citation2018, 20); and from portraying people who live near border zones as ‘necrocitizens’ (Díaz-Barriga and Dorsey Citation2020, 14); to discussing the ‘necropolitical logic’ of migration governance (Danewid Citation2017, 1679); the ‘necroharms’ of the border (Iliadou Citation2019); or the ‘necropolitical experiences of refugees in Europe’ (Davies, Isakjee, and Dhesi Citation2017). We read about it, too, in alarming media reports, such as the Association Press documenting 56,800 dead or missing migrants worldwide between 2014 and 2018 (Fregonese et al. Citation2020). Building on this, academics have quite explicably described the construction of a ‘border death regime’ (Cuttitta, Häberlein, and Pallister-Wilkins Citation2019, 46), where death itself is positioned as a keystone upon which all else falls. As other scholars have argued, sovereign authorities are ‘governing migration through death’ (Squire Citation2017, 515 emphasis added; also see Doty Citation2011), and use ‘thanatopolitics as a mode of border management’ (Iliadou Citation2019, 181; see; De León Citation2015). Allied to this charnel focus on forced migration is a rich assemblage of insightful scholarship that places the dead body as its main protagonist, exploring the politics of burial (Balkan Citation2015; Squire Citation2017), body identification (Kovras and Robins Citation2016), post-mortem repatriations (Perl Citation2017) grief (Danewid Citation2017), mourning (Alonso and Nienass Citation2016), memorialisation (Horsti and Neumann Citation2019), haunting (Papailias Citation2019), ‘disappearability’ (Laakkonen Citation2022), death governance (Stepputat Citation2020), death activism (Stierl Citation2016), ‘CommemorAction’ (Alarm Phone Citation2021), fatality metrics (Last et al. Citation2017), ‘corpse politics’ (Stümer Citation2018), ‘death by nature’ (Schindel Citation2022, also see Doty Citation2011; De León Citation2015), and even the ‘death of asylum’ itself (Mountz Citation2020), as key ways – among others – to understand and resist the macabre realities of forced migration. Within migration scholarship, a necro-consensus has emerged.

This article shifts focus and puts analytical pressure on the dominance of death within migration studies. This is not to dispute the grim magnitude of border fatalities, nor the valuable contribution of the abovementioned scholarship – but to advance other ways of thinking about the lived realities of forced migration, and the perniciously liberal violence that contemporary states increasingly use (see Isakjee et al. Citation2020). By moving beyond ‘body count’ and mortality as the arbiters of suffering, we argue that self-proclaimed liberal states no longer aim to use death as the primary nomos of biopower in their violent production of borders. In making this argument we build upon postcolonial scholarship (Fanon Citation1963; Puar Citation2017) to suggest more emphasis should be placed on less-than-deadly aspects of bordering, and the political work of injury in particular. Bordering through injury might appear as minor relief given the EU’s aforementioned propensity to border through death. Yet we contend in this paper that killing and letting-die have played an outsized role within border studies. As Puar (Citation2017, 131) articulated, ‘the injured do not count in the “dry statistics of tragedy”’, and so too have they tended to be missing in the way we research borders.

Within geographical literature, the injured have often inhabited an epistemic blind spot (cf. Jones Citation2022; Ralph Citation2012): injury is frequently overlooked both in our discussions of politics more broadly, but also in the way we unpack and conceptualise the workings of biopower at the border. As with colonial occupation, political terrorism, and armed conflict, injuries at the border are an order of magnitude more frequent than deaths, yet their strategic role in the production of borders is largely left unsaid. While death remains the ultimate proxy for measuring political harm, focusing only on death – conceptually, analytically, and empirically – risks eliding other forms of control through which sovereign power more commonly operates: an omission that liberal states especially are all too willing to exploit. If the only thing that ‘counts’ politically is death, then the mass production of injury can operate under the radar.

In tempering the preoccupation with death and stepping away from a ‘necrotic gaze on migration’ (Presti 2019, 1348), we do not downplay its significance. Injury and death are not oppositional or dichotomous; they lie on a continuum of violence and oppression. As geographers have noted, killing and letting-die are foundational political concepts (Tyner Citation2019), not least in conceptualising racism as ‘group-differentiated vulnerability to premature death’ (Gilmore Citation2007, emphasis added). In this paper however, we foreground other less-than-deadly, but no less important aspects of biopolitical control that conspire to incapacitate, coerce, and make the lives of unwanted populations strategically ‘wretched’ (Fanon Citation1963). Furthermore, focusing on injury as opposed to death creates more space to emphasise the lively resistance that people on the move regularly exemplify, which can all too easily become flattened when our intellectual endpoint is that of a corpse.

Our focus on debilitation also resonates with recent environmental justice scholarship that has foregrounded the significance of ‘accumulated injuries’ (Mah and Wang Citation2019, 1961), as well as attunement to forms of violence that are temporally ‘slow’ (Nixon Citation2011) or inescapably enduring (Jones Citation2022). Likewise, our focus on injury dovetails with Wells’ (Citation2019) discussion on the politics of suffering, where he rejects Agamben’s figure of homo sacer ‘as the man available to be killed’, and introduces an alternative figure of homo dolorosus, or ‘the man available to be made to suffer’ (Wells Citation2019, 417). These concepts highlight the spectrum of intermediate experiences that exist between the abstract pillars of biopolitical belonging and necropolitical abandonment (Aradau and Tazzioli Citation2019; Sparke Citation2018), occupying a ‘grey area’ of border governmentality (Tazzioli Citation2021). This paper adds further empirical and theoretical weight to these debates, by centring the political work of injury and the violence of not letting-die.

Contra Foucault’s claim that the ‘sovereign power’s effect on life is exercised only when the sovereign can kill’ (Citation1976, 240), along the landlocked borders of the EU something quite different is at work. By taking seriously the idea of the ‘right to maim’ (Puar Citation2017), we can see how injury and not ‘letting die’ becomes a much more powerful political resource than state-sanctioned killing or letting die. By withholding death, liberal states avoid scrutiny and uphold a pretence of ‘care’ or even ‘rescue’, all the while inflicting grievous harms that do not ‘count’ within the politics of liberal respectability. Before we discuss our empirical research, however, it is important to further unpack the contribution of Jasbir Puar (Citation2017) to understandings of Foucault’s original biopolitical mapping.

The Politics of Not Letting Die

Despite offering useful interventions at the intersection of disability studies, queer theory, and critical race studies, Puar’s work on the ‘right to maim’ (Citation2017) has remained relatively overlooked within human geography and migration studies (cf. Aradau and Tazzioli Citation2019; Jones Citation2022; Minca et al. Citation2022; Pallister-Wilkins Citation2022; Tazzioli Citation2021). Puar (Citation2017) analysed Israeli tactics of debilitation used against Palestinians, uncovering the strategies that enable the Israeli state to enact severe brutalities against occupied people and environments, whilst simultaneously claiming to care for human lives through humanitarian and biopolitical protection. The techniques she documents include ‘shoot to cripple’ (ibid, 129) practices, such as creating permanent injuries by firing live rounds into arms, knees, and femurs; firing ‘dumdum’ bullets that expand upon impact and are difficult to extract; or using high-velocity fragmenting bullets that lead to ‘high rates of crippling injuries’ (ibid, 131). Crucially, such tactics are deliberately non-lethal, and remain absent from well reported death-tolls. As such, the use of injury in this way is a brutal manifestation of the tension between the need of contemporary states to appear liberal, ‘while simultaneously practising illiberal forms of colonialism and imperialism’ (Wells Citation2019, 418; also see; Isakjee et al. Citation2020). As Jones (Citation2022, 6) articulated, ‘maiming trades in a perverse currency of restraint’, and by adopting techniques that are less-than-deadly, the Israeli government is able to perform a biopolitical tightrope trick: maximising the coercive capacity of state-sanctioned suffering, while minimising accusations from humanitarian groups that the state is not adhering to Enlightenment norms of biopolitical behaviour. As this article will show, this securitisation-humanitarian dialectic is not only the preserve of Israeli colonial occupation, but is also central to the violent production of EU borders.

For many liberal states: ‘the illegalized body is both a security threat and a life to be secured’ (Sanyal Citation2019, 441). Liberal societies such as the EU and its member states, for example, awkwardly juggle divergent demands of control and care (Pallister-Wilkins Citation2022), whereby the deadlier biopolitical technologies outlined by Foucault (Citation1976), including those of letting die, have been replaced with other less-than-deadly forms of coercive violence. The systematic brutalities that we discuss here reveal a ‘careful kind of wounding’ (Jones Citation2022, 10) – calculated, patterned, and organised – which are not so much reliant upon a ‘state of exception’ (Agamben Citation2005) but instead, depend upon a ‘state of acceptance’ (Sandset Citation2021), where debilitation and injury have become a politically sanctioned, reasonable, or even ‘acceptable’ when used against racialised groups. This attenuation of violence – producing injury without death – helps sovereign authorities forgo humanitarian oversight, while absolving themselves of responsibility for the non-lethal harms they produce.

Along the snow-covered mountains and dense forests of the EU’s border, injury has replaced death as the liberal state’s weapon par excellence. A non-lethal biopolitical experiment is being enacted against the bones and flesh of racialised groups who are attempting to navigate the perilous gauntlet of EU ‘protection’. Having established the theoretical foundation of this paper, the following empirical sections will discuss our research in the Balkans, focusing on two key interlinked sites that produce debilitation: the Pushback and the Camp. In doing so, we use the ‘right to maim’ to bear upon the political centrality of injury at the border.

Geographies of Injury: The Pushback

In our research, the most direct example of the ‘right to maim’ being practised as a form of biopolitical control takes place during violent pushbacks from EU territory. During these collective expulsions, which are routinely conducted by Croatian, Hungarian, Romanian, Greek, Polish, and Bulgarian authorities – among others – asylum seekers are illegally forced back across the EU border to external countries, without having their asylum claims processed. Not only do these summary returns violate domestic, EU, and international laws pertaining to the rights to asylum and freedom from torture (Kovačević Citation2021), they are also characterised by severe beatings and the systemic delivery of injury.

Blunt force contusions from fists, boots, and batons are very common among pushback survivors, as are wounds from dog bites, localised burns from electric tasers, and eye irritations from tear gas. During violent removals from EU territory, pushback survivors routinely face the psychological trauma of degrading detention conditions, arbitrary deprivation of liberty and torture, as reported by a wide range of notable organisations including the Council of Europe (Citation2019), Human Rights Watch (Citation2022), and the United Nation’s Human Rights Council (OHCHR Citation2021). This is further corroborated by police whistleblower reports, and burgeoning research by activists and scholars (see BVMN 2022; Augustová, Carrapico, and Obradović-Wochnik Citation2023; Bergesio and Bialasiewicz Citation2023; Davies, Isakjee, and Obradovic-Wochnik Citation2023; Isakjee et al. Citation2020). Despite the cruelty of these extrajudicial expulsions, and their discord with the liberal pretensions of the EU (Isakjee et al. Citation2020), their frequency and geographic spread has rendered pushbacks ‘a default mode of border management, rather than … an aberration or exceptional practice’ (Karamandidou and Kasparek Citation2022, 17). In short, pushbacks can be viewed as a ‘sustained practice of maiming’ (Puar Citation2017, 144).

Every day during fieldwork in the summer of 2018 and 2019, we met people returning to northwest Bosnia from Croatia with visible injuries from physical attacks. It was not uncommon, as Augustová (Citation2023, 3) described, to see ‘broken limbs, open wounds, burns from electrical devices, and foot-long bruises from police baton strikes’. In conversations with pushback survivors, they typically reported being punched, kicked, and beaten with iron rods or electric charges. Others described being forced at gunpoint to wade through rivers as they were expelled from EU territory, or showed their injuries sustained from being thrown down ditches and ravines during their violent pushback. As one interviewee described, who had recently been removed from the EU: ‘The Croatian police beat us with sticks very badly. Spraying your eyes and electric shocks … there are broken bones, legs, arms’.

This ‘sanctioned maiming’ (Puar Citation2017, 141) – which is widespread across multiple EU border zones – often creates significant bodily harm, including fractured and broken bones. At other times, the forms of harm are much more subtle, with injuries caused by the confiscation of shoes and clothing during pushbacks, with survivors forced to walk long distances back to camps in Serbia or Bosnia partially clothed or barefoot, in an all too literal manifestation of ‘bare life’ (Agamben Citation1998). As a result of these confiscations, foot injuries are also common (), with infected blisters, cuts on the soles of feet, and in extreme cases even gangrene.

Figure 1. A man with a foot injury incurred during a pushback from the EU. He was beaten by Croatian police and his shoelaces were confiscated. (Photo: Thom Davies).

While many aspects of pushback injuries appear mundane, others are extraordinary and sadistic. In one interview, a pushback survivor described how police in Croatia had poured toxic powder into his shoes while he was detained, giving him chemical burns. In another interview, a volunteer doctor who treats pushback survivors described how the police would ‘get people to jump around like frogs while they beat them’. In other interviews, Bosnian residents who live near the EU border reported hearing screams at night from the Croatian side of the fence, and men running semi-naked through their backyards, having been stripped of their clothing before expulsion. Working alongside activists in Bosnia and Serbia who provide showers and clean clothes for people on the move, we would often be shown fresh wounds, cuts, and bruises inflicted by police inside the EU; physical traces of a sustained geography of injury that starkly recalls the ‘right’ to maim. Taken together, these harmful practices have the intention of ‘creating injury and maintaining … populations as perpetually debilitated’ (Puar Citation2017, x).

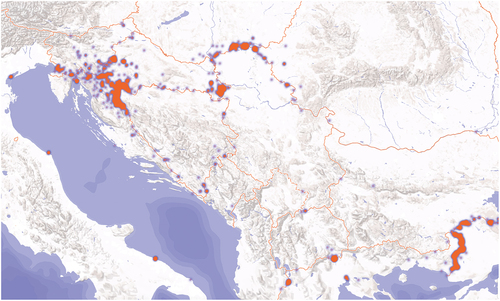

The mass production of injury has political utility, and it is important to foreground the massive scale of political maiming (see ). According to NGO reports, over 346,000 pushbacks took place in 2023 at European external borders, making ‘an average of 947 per day’ (11.11.11, 2024, 12). In this region, we estimate that tens-of-thousands of people are violently pushed back every year from within the EU. Although most countries who operate pushbacks deny it entirely, Hungary has admitted to forcibly expelling more than 71,000 people into Serbia in the 5 years following 2016 (UNHCR Citation2021). Meanwhile, the OHCHR (Citation2021) reported 22,500 pushbacks occurring between May 2019 and November 2020 from Croatia to Bosnia alone. This equates to an estimated monthly average of 1700 recorded pushbacks from Croatia, peaking in October 2020 ‘with 1934 registered pushbacks as well as cases of extreme violence’ (Danish Refugee Council Citation2021). Building on the weight of available evidence, a UN investigation cited pushbacks as a ‘routine element of border governance’ (OHCHR Citation2021, 18), and the huge numbers involved indicate that the ‘right to maim’ is firmly entrenched within European border policy. For self-declared ‘liberal’ democracies such as those in the EU, ‘eventful killing is undesirable’ (Puar Citation2017, 166), yet in stark contrast, eventful maiming has become a perfectly acceptable practice. What is notable about these mass injuries is that they barely feature in the calculus of humanitarian scrutiny.

Patterns of Injury

One mechanism through which this customary violence is being scrutinised is through the work of autonomous border violence monitoring collectives such as No Name Kitchen (NNK) and the Border Violence Monitoring Network (BVMN). Since January 2017, this coalition of Balkan-based organisations have recorded testimony from over 1,700 individual cases of group expulsion, comprising between 1 and 250 people in each pushback, who were expelled en masse from EU countries including Croatia (63%), Slovenia (14%), Hungary (7%), Greece (5%), and Italy (1.6%) (BVMN 2023). This recorded sample, which represents just a fraction of the total number, affected at least 25,000 individuals. Almost half (47%) of documented group expulsions involved minors, suggesting that the EU border is not only a site of injury but also a space of mass child abuse. The activism of these groups has led to strategic litigation and advocacy (for instance, CMS Citation2023). Their growing database of pushback reports – more than 1400 of which we analyse here (see ) – also helps to illustrate the pivotal role that injury plays within the pushback regime.

Table 1. Key characteristics of reported pushbacks: data sourced from 1414 reports by border violence monitoring network, between January 2017 and February 2022.

By analysing BVMN’s pushback data, alongside interviews with medical experts in north Serbia and northwest Bosnia, and through our own observations while conducting border violence reports with pushback survivors, we noted similarities in the patterns of behaviour exhibited by the perpetrators of pushbacks. In 77% of cases direct physical assault occurred. From a forensic perspective, the intentionality of this harm can be witnessed in the injuries themselves, which often include ‘pattern bruising’. One interviewee, who worked as a paramedic in the US before providing medical aid to hundreds of pushback survivors at the EU border, remarked:

The bruises themselves happen in a set pattern on their skin. There is an order to it. They reflect the object that they are beaten with, and it is continually the same. They themselves are patterned, they appear in a pattern, and over a pattern of time.

The repetitive nature of this violence, occurring ‘over a pattern of time’, on similar parts of the body, in similar ways, reflects the calculated nature of this targeted maiming: ‘The other places where you would see that is in abuse cases’, he continued. This starkly recalls connections that feminist geographers have made between domestic abuse and political terror, with both aiming ‘to exert political control through fear’ (Pain Citation2014, 531). As the paramedic reflected further: ‘There is a very real case to be made that what is happening is the systematic abuse of the people on the move’. The coordinated and ‘systematic’ nature of this abuse was also noted by a volunteer doctor who had spent several months treating pushback survivors:

We definitely noticed a phasical [sic] pattern of what the police were doing week by week, and it was definitely some kind of systematic decision making, there must have been some organisation about what they were going to do, because one week they would take everybody’s left shoe; there was a week where they were forcing everyone to go into running water, like a river, forcing people to go in to the water. And there were weeks where they were targeting people’s knees. (Interview with medic, July 2022)

Such targeted debilitation, which has ‘an order to it’, indicates how pushbacks are not the result of individual bad actors, but are the product of a politically orchestrated form of biopolitics that physically manifests the ‘right to maim’ (Puar Citation2017). Indeed, whistleblower statements from Croatian police further indicates that this violence is carefully organised, including an anonymous letter that described official orders to ‘return everybody, without paperwork, without track, to take their money, to smash their cell phones … and return the refugees to Bosnia by force’ (ECCHR Citation2020, 2). As the doctor explained, the perpetrators of pushbacks often target parts of the body that are ‘important for walking’, emphasising the immobilising intent of this crippling violence, where maiming creates ‘an entire population with mobility disabilities’ (Puar Citation2017, 136).

The shared characteristics of pushbacks also extends beyond the direct violence of kicks, punches, and baton strikes (see ). For example, most pushbacks (63%) involve the theft of belongings, including money and electrical devices, as well as the routine destruction of possessions (36%). The equipment most frequently targeted for destruction by the police include items needed to move across borders during ‘the Game’ (Augustová, Carrapico, and Obradović-Wochnik Citation2021), such as GPS, battery packs, bags, food, shoes, and phones (). In a perverse echo of the maiming of human bodies, this mobility-infrastructure is often not fully destroyed, but incapacitated just enough as to become useless: screens are smashed; straps on rucksacks are cut; and those that are allowed to retain their shoes, have their shoelaces confiscated, further curtailing mobility. As with other aspects of the right to maim, the injury of everyday equipment creates ‘infrastructural impediments to deliberately inhibit and prohibit movement’ (Puar Citation2017, 157).

Figure 3. Phones are often smashed and incapacitated by police during pushbacks (Photo: Thom Davies).

Many transit groups who are expelled into Serbia or Bosnia were originally detained deep inside the EU. More than one in five (21%) of the reported pushbacks are so-called ‘chain pushbacks’ (Bergesio and Bialasiewicz Citation2023; Davies, Isakjee, and Obradovic-Wochnik Citation2023), from countries including Italy (1.6%), Slovenia (14%), and in several cases even Austria. Not only does this demonstrate a willingness to coordinate pushbacks across multiple EU jurisdictions – and thereby denying the right to asylum by inflicting the right to maim – the long transnational journeys of ‘disciplined mobility’ (Moran Citation2016, 86) also create fresh opportunities to cause injury. Detainees are exposed to hours of debilitating conditions while trapped inside prisoner transport vehicles, with 26% of reported pushbacks involving reckless driving which often leads to injury and vomiting; and a further 17% of reported pushbacks involving exposure to extreme temperatures in overcrowded police vans, as well as the psychological trauma caused by a ‘severe lack of oxygen’ (Augustová, Carrapico, and Obradović-Wochnik Citation2021, 8). As one Afghan father described during an interview, a day after he and his young family had been violently expelled from the EU after attempting to claim asylum in Croatia:

The van was very hot, very hot. And they drove badly, banging us from side to side … Two adults and a baby vomited inside the van … They put on hot air in the van. It gave us breathing problems. (July 2022)

The debilitation of detainees through forced mobility and the restriction of air is a common feature of pushbacks, and closely mirrors ‘the capacity to asphyxiate’ (Puar Citation2017, 135), where choke points and choke holds incapacitate racialised groups (Tazzioli Citation2021). Descriptions of ‘breathing problems’ and the suffocating conditions in overcrowded police vans also echoes the ‘I can’t breathe’ campaign within the BLM movement, emphasising how pushbacks, police brutality, and borders are underpinned by a politics of white supremacy and a spectre of ‘global apartheid’ (Lindberg Citation2024, 15). Unlike the extreme ‘asphyxiatory control’ (Puar Citation2017, 135) that led to the racial murder of George Flloyd in 2020, however, all of the pushbacks discussed here – including the aforementioned tactic of being forced to undress (25%); being forced to wade or swim through freezing water (7%); and even dog attacks (6%) – are carefully choreographed to maim only (see ). In other words, they are designed to ‘keep the death toll numbers relatively low in comparison to injuries, while still thoroughly debilitating the population’ (Puar Citation2017, 144).

All of these maiming practices have immediate bodily effects, but they also operate in the future tense: designed not only to incapacitate would-be asylum seekers in the here and now, but also to discourage future border transgressions. Just as with the ‘shoot to cripple’ policy described by Puar (Citation2017, 129), where the Israeli military ‘attempt to pre-emptively debilitate the resistant capacities of another intifada’, the actions of EU authorities strive to impair future mobility. From the physical injuries of ‘targeting people’s knees’ (medick interview), to the psychological trauma of firing live ammunition during forced expulsions (10%: see ); the types of violence used are carefully ‘calibrated to have long-lasting effects’ (Jones Citation2022, 2). As Stojić Mitrović and Vilenica (Citation2019) argued, forced migration into Europe is often circulatory in nature, with multiple, repeated, and continual attempts often made by people seeking the relative safety of the EU. For example, some of the participants interviewed in this study described trying to reach the EU over 30 times. As such, the widespread use of maiming aims to cut-off the circulation of people attempting to reach the EU’s liberal ‘protection’: not by killing or letting them die, but by creating an endemic and attritional biopolitics of incapacity.

The Geopolitics of Injury

To understand why pushbacks occur at such a magnitude, we must zoom out from the scale of the human body and address geopolitics. To take Croatia as an example, its willingness to inflict mass injury can be attributed to its goal of becoming a member of the Schengen Area. As EU Commission staff and Frontex representatives confirmed during interviews, not only were they well acquainted with Croatian border violence, they also suggested it was a necessary step to earn Schengen status. In other words, showing a readiness to injure in defence of the EU’s external borders – and thus become a ‘watchdog of Europe’ (Bergesio and Bialasiewicz Citation2023, 12) – was a vital prerequisite for admission into the world’s largest visa-free area.

Despite mounting evidence of human rights violations, EU leaders lavished praise on Croatia for its valiant borderwork while directly funding this geopolitics of injury to the tune of €163.13 million to Croatia since 2015 (European Commission Citation2021). The EU paid for hardware, training, and infrastructure designed to aid the debilitation of people on the move. The European Commissioner for ‘Promoting our European Way of Life’ described Croatia’s Shengen accession as ‘a milestone in Croatia’s European path’ (Schinas Citation2022). Thinking with Puar (Citation2017): the rehabilitation of Croatia – as a full member of the European political family – was predicated on the debilitation of people on the move. In this way, border violence can be understood as an organised attempt to extract political capital from the mass maiming of racialised groups.

The geopolitical dimension of pushback violence can also be evidenced in its fluctuations over time: while the violence we witnessed in 2018 and 2019 was overt and spectacular (broken limbs; bandaged faces; destroyed phones), the visibility of pushback violence had become more subtle and covert during fieldwork in 2022 and 2023. By this point, Croatia had its agreement signed for Schengen approval, which came into force in January 2023. As one pushback survivor described, ‘they do not beat on the bone because the bone cracks. They beat on thighs and legs’. Similarly, a medick observed in the months prior to ratification:

Right now, the pattern that I am seeing is that they are targeting backs and thighs, and places where the bruising won’t be obviously visible, unless the POM lifts up a leg to show someone, or takes off a shirt.

While conducting pushback reports, it was also less common at this time to see smashed phone screens (see ) as the police had adopted less visible methods of maiming: ‘They switched to jamming screwdrivers in the charging points of cell phones … ’ explained one activist ‘ … to try to disable phones a little more covertly’. This attenuation of violence reveals an effort to orchestrate a careful kind of violence (Jones Citation2022), which strikes a delicately calibrated balance between brutality and deniability: a thermostat of harm that can be cranked up or dialled down depending on the political need or humanitarian oversight – thus ensuring that the ‘strategic cruelty’ (Sajjad Citation2022, 1) of border violence remains safely within the bounds of liberal acceptability.

Humanitarian Cosplay and the ‘Right to Rescue’

When humanitarian scrutiny does threaten the violent enforcement of borders, liberal states often conduct forms of ‘epistemic borderwork’ (Davies, Isakjee, and Obradovic-Wochnik Citation2023), or ‘practices designed to deny, conceal, or undermine knowledge about the violence of borders’ (ibid, 7). For example, along with the right to maim, liberal states exercise what we call ‘the right to rescue’ or humanitarian cosplay. This names the practice of refuting accusations of border brutality by inventing a fiction that the perpetrators of violence are actually rescuing, protecting, or saving the lives of people on the move. For example, in response to a newspaper article that accused Croatian police of ‘spray-painting the heads of asylum seekers with crosses’ (Guardian Citation2020), the Croatian Ministry of Internal Affairs [Ministarstvo Unutrasnjih Poslova] (MUP) released a statement rebuking the Guardian for failing to mention ‘the many lives of migrants which have been saved by the Croatian Police’ (MUP Citation2020). Likewise, in response to video footage of an illegal pushback taking place published by Human Rights Watch, MUP released a similar statement of dismissal that highlighted: ‘several cases of the Croatian border police rescuing migrants who were in life-threatening situations at the state border’ (MUP Citation2020). Further compounding this institutional gaslighting, the press release was accompanied by a photograph of a Croatian policeman pouring a bottle of water into the open mouth of a detained man, who was sitting on the forest floor, accompanied by two Croatian paramedics ().

Figure 4. “Rescue” photograph attached to a press release responding to Human Rights Watch. Identities hidden (MUP Citation2020).

Such denial of harm through the invocation of ‘rescue’ is simply border violence in humanitarian drag, where the very actors responsible for delivering injury, effectively cosplay as rescue workers, and further the fiction that EU states are benevolent actors. In this way, pushbacks are turned from spaces of injury into opportunities for humanitarian virtue signalling. They provide perpetrators of violence with the possibility of rehabilitating their liberal facades by performing humanitarian dress-up that relies upon ‘not letting migrants die’ (Pallister-Wilkins Citation2022, 183). Injury, maiming, and debilitation – as opposed to death – give EU states ample room to bolster their humanitarian credentials, whilst simultaneously administering a careful kind of cruelty that evades the optics of public scrutiny. This fiction of rescue also points to the central aim of the right to maim: the ability to brutalise racialised groups whilst also appearing to be respectable, liberal, and humane.

To further maintain this enlightened imaginary, and to foster the liberal acceptability for widespread violence at EU borders, death needs to be withheld. We see this occurring in its starkest form during ‘hospital pushbacks’ (medick interview, northern Serbia). In this gruesome example of the right to maim, hospitalised refugees and migrants who have been seriously injured from road accidents or police beatings inside the EU, are taken directly by the police from their hospital beds – where they may have undergone major surgery – and are dumped straight back over the border into Serbia. As medical witnesses reported to us during interviews, seriously maimed individuals who had been gravely injured inside Hungary have been found in isolated areas on the Serbian side of the fence, limbs still broken, bandages still fresh, having received invasive medical interventions while in the EU. Hungarian police routinely destroy medical records and survivors have little recollection of what treatment they may or may not have received. During hospital pushbacks, medical care is provided only insofar as to ensure people are alive enough to be illegally deported. These efforts to withhold death while administering border violence demonstrate how a logic of ‘will not let die violence’ (Puar Citation2017) has become a cornerstone of border management in liberal democracies.

While it would be easy to stay with the immediacy of direct violence, this would overlook the wider politics of debilitation that we argue is central to the enforcement of contemporary borders. The direct violence described above should be situated within a broader geography of injury that underpins the EU border, and the lived experiences of people on the move. As Rexhepi (Citation2022, 5) described, there is a ‘carceral capitalist conglomerate of policing, pushbacks, or confining refugees along the Balkan route’, and central to this are the camps that exist beyond the borders of the EU into which injured people are enclosed, housed, and further debilitated. The spatiality of ‘migrant camps’ together with their inhabitation by state-funded aid organisations, can provide cover for a broader politics of injury, rather than being envisaged as spaces of ‘care’ or even relief. In the final empirical section, we attend to the role of camps within the politics of debilitation.

Geographies of Debilitation: The Camp

When transit groups are expelled from the EU, they often return to places to shelter. ‘Shelter’ is varied, including official camps administered by international organisations, reception centres run by local authorities, makeshift settlements, and different forms of informal housing such as squats and ‘jungles’, which are sometimes supported by activist groups (see Bird et al. Citation2021; Davies, Isakjee, and Dhesi Citation2019). Across the ‘Balkan Route’ official camps to which pushback survivors return, are often the only means of accessing medical treatment. Camps offer varying degrees of medical aid and actual protection. Some, such as the Vučjak camp near the Croatian border, had no running water, sanitation, or electricity; camps on the Greek islands are routinely overcrowded with inadequate medical facilities whilst others, such as the camps in northern Serbia, provide rudimentary medical facilities. Taken together, the assemblage of camps that are scattered beyond the edges of the EU metropole form a geography of ‘pre-emptive debilitation’ (Puar Citation2017). Such camps incubate incapacity, erode resilience, and create conditions of injury by limiting the means of life (see Davies, Isakjee, and Dhesi Citation2017).

The camps found along the Balkan Route at the EU’s margins, whether formal or informal, are ‘part of the biopolitical scripting of populations available for injury’ (Puar Citation2017, 64). Camps themselves are not linked to pushbacks directly; in fact, to an outside observer, they have all the appearances of humanitarian care, or even hope and resistance. Yet these camps – which are often directly funded by the EU – produce ‘a future-injured, available-for-injury body, for whom long-term bodily health and integrity is already statistically unlikely’ (Puar Citation2017, 72). By withholding basic humanitarian supplies, camps produce people on the move who are ‘pre-disabled’ by the debilitating living conditions of the camp (Puar Citation2017, 86). As one volunteer doctor who treats people on the move in Bosnia observed:

A lot of things you see here are diseases of poor living conditions … You know, the scabies, the soft tissue wound infections, if you live in an environment where it is really difficult to keep clean.

Encampments and pushbacks are dialectically linked through the fact that poor living conditions make it difficult for injuries to heal. Importantly, they also cause injuries in their own right, exacerbated by – as another medick explained: ‘the infections that follow as a consequence of the insanitary conditions in which they live’. While the violence described within pushbacks are fast-acting, the debilitation of the camp is characterised by attrition, and slower forms of harm that are enduring in nature (Jones Citation2022). For example, a medick who had treated 455 people on the move in the previous month, explained how the health issues he regularly encounters connect to inadequate living conditions:

Clearly the number of mosquito bites; the GIs [gastrointestinal illnesses] related to the food that they are given and the lack of clean ways to cook it.

The Vučjak camp that existed between June and December 2019 on the Bosnia-Croatia border is illustrative of the relationship between camps and pushbacks. During our fieldwork in 2019, we made several trips to Vučjak, a camp comprising tents placed directly on the polluted site of a former rubbish dump. The camp was close to the Croatian border but isolated on a mountainside, a long walk from any facilities. It was a collection of tents, with no other shelter, despite being formally run by the local authority. For some time, there was also no running water or working toilets. The bathroom and shower facilities comprised temporary cabin structures, and some washing facilities were partly out in the open. Food was driven to the site and distributed by the Red Cross. There was no medick on site, though some first-aid was provided by the Red Cross and a visiting volunteer. Perhaps most alarmingly, it was adjacent to several fields of uncleared landmines from war in the 1990s (Minca and Collins Citation2021). Indeed, a central focal point of the camp – and one of its only ‘facilities’ – was a large landmine map, with the word: ‘WARNING!’ (). The map played a key role in ensuring the ‘right to maim’ did not extend to actual death, which would raise unwanted humanitarian scrutiny. As one resident of the Vučjak camp explained sardonically, pointing to the forest surrounding the camp: ‘There is no toilet, so we have to go in the minefield’.

Figure 5. A young man in the Vučjak camp examines a map of the surrounding minefields (Photo: Thom Davies).

It makes little sense to examine camps in this borderzone without discussing them in relation to the pushback regime, such is the circulatory nature of the Balkan Route (Stojić Mitrović and Vilenica Citation2019). Both can be understood as border technologies that deliver debilitation in different but connected ways. From this camp, for example, people would leave for ‘the Game’ and attempt to cross the mountainous EU border while avoiding police detection and navigating the minefields. If they were intercepted inside Croatia and pushed back, they would return to the camp, often barefoot, their clothes, possessions, phones, and food having been destroyed or confiscated. They would often return to the camp with serious injuries, unable to obtain basic medical help such as bandages or pain relief, and with limited prospect of a fast recovery. The site was dusty, unhygienic, and even toxic, with no place to rest or recuperate. The tents were overcrowded, and the temperatures were unbearable in the extremes of both summer and winter. As one resident explained succinctly: ‘This is not a place for living’.

Injury from camps and injury from pushbacks are interconnected and can be read as two parts of a larger politics of debilitation that characterises the EU border. The direct injuries received during pushbacks became aggravated by the camp’s deplorable conditions, through ‘the attrition of the life support machine that might allow populations to heal from this harm’ (Puar Citation2017, 143). The walk to the nearest health facilities was difficult from the Vučjak camp, especially for those with injuries (.). Meanwhile, local authorities policed the camp, with officers guarding the gate around the clock. They controlled which humanitarian aid groups could obtain access to the camp and restricted access to medical volunteers and other forms of solidarity. At regular intervals throughout the day, police cars would arrive on site and detained people would pile out. At other times, large groups of men and boys would be frog-marched by police to the camp, having been apprehended in the local municipality of Bihać, which had instigated de facto ‘Jim Crow’ policies that racially segregated migrants from congregating in the public spaces inside the city.

Figure 6. The isolated Vučjak camp in the foothills of the Dinaric mountains, on the border of the EU. (Photo: Thom Davies).

As we have witnessed elsewhere across Europe, refugee camps are places where racialised groups are ‘not actively killed, but are instead kept injured, dehumanised and excluded’ (Davies and Isakjee Citation2019, 214). The ‘injured lifeworlds’ (Jones Citation2022, 3) of inhabitants become evermore debilitated in the space of the camp through denial of aid and state inaction. Places such as Vučjak are sites where scabies spreads, hunger persists, and hope can fade. They are spaces, too, where a biopolitical fantasy plays out that imagines ‘resistance can be located, stripped, and emptied’ (Puar Citation2017). Yet the courage and the resolve of people on the move proves this is often not the case. Puar described Gaza as ‘not a death camp but a debilitation camp’ (Puar Citation2017, 153), and so too are EU-funded border encampments spaces of incapacitation. Camps can be understood as geographies of debilitation: places where the right to maim takes spatial form, and the mass production of injury is disguised behind a thin veneer of humanitarian ‘care’.

Poor camp conditions cause psychological injuries, too, including the ‘somatization of trauma’ (Puar Citation2017, 152). One volunteer medick we interviewed in Bosnia told us that much of what they see whilst treating people on the move is ‘self-harm, somatization, the sort of dissociative episodes. And part of that is because the camp setting is really awful for mental health’. Keeping camps deplorable, in other words, helps debilitate physical and mental health. Although our focus here is on formal camps run by local and national authorities, in less formal accommodation such as squats, we also encountered people with lingering physical injuries, as well as significant levels of self-harm and drug misuse that was exacerbated by the immobilisation, the uncertainty, and the boredom of being trapped at the border.

The right to maim is not confined to the human body. In Palestine, for example, the ‘maiming of infrastructure’ is a key Israeli tactic of debilitation, with the aim to ‘decay the able-bodied into debilitation through the control of calories, water, electricity, health care supplies, and fuel’ (Puar Citation2017, 144). In a similar way, along the ‘Balkan route’, access to basic infrastructure and resources such as livable accommodation is often deliberately withheld by state authorities, forcing people to find shelter in squats in abandoned buildings, or makeshift ‘jungle’ camps (Davies, Isakjee, and Dhesi Citation2019), or to inhabit one of several semi-carceral formal camps administered under EU oversight. Just as the ‘infrastructures of liveability’ (Tazzioli Citation2021, 5) are routinely dismantled and disrupted at other borderzones, including Calais and Ventimiglia, so too is this a common feature along in the Balkans, where squats and makeshift camps are regularly raided, to further incapacitate people on the move.

The sanctioned maiming described in the pushback section above and the debilitating conditions described here work in dynamic unison. Both are carefully calibrated to incapacitate unwanted groups, to immobilise – and if possible – encourage self-deportation. During interviews for this project, we witnessed this take place when representatives of the International Organization for Migration (IOM) – who operate several EU-funded camps in the Balkans – explained with glee how they had recently encouraged a family to return to India. Far from producing conditions of outright death that might attract humanitarian scrutiny and condemnation, the deplorable conditions of camps produce a form of ‘attenuated life … ’, in which ‘…neither living or dying is the aim’ (Puar Citation2017, 139). Instead, these spaces contribute to a wider politics of debilitation that helps reinforce the EU border.

Conclusion

This paper has explored the strategic ways that injury and debilitation are used to maintain and reinforce borders, while avoiding humanitarian scrutiny. Although borders are violent technologies, and the fear of death may be leveraged by governing agencies to control people-on-the-move, death itself is rarely the desired outcome. Following Puar (Citation2017), we can portray borders as spaces of debilitation designed to erode the resistive capacity of people on the move. It is the contention of this paper; therefore, that non-lethal violence should be situated much more centrally within understandings of biopolitics. Alongside the deadlier effects of contemporary governance, where control can manifest through the production of premature death, there is also political utility in not killing. Such attenuated forms of harm – where death is avoided whilst ‘tolerable’ brutalities are normalised – allows state violence to persist beneath a threshold of liberal acceptability.

By foregrounding the political geographies of injury, we can see that the target of this biopolitical action is not ‘life itself’ – as befits conventional conceptualisations of biopower or necropolitics – but rather ‘resistance itself’ (Puar Citation2017, 135). No one is purposefully being killed by the violence we document in this paper. Instead, the right to maim is deployed rather than the right to kill, to test ‘how much resistance can be stripped without actually exterminating the population’ (Puar Citation2017, 136). By drawing attention to the multiple acts of maiming that EU authorities inflict upon POM, we argue that the mass production of injury at the border – instead of death – allows liberal states to reproduce a fiction of ‘care’ that simultaneously masks its racialised logics of security and violence. Along the borders of the EU such ‘will not let die violence’ (Puar Citation2017) has become a normalised activity. Debilitation without death is the aim of such biopolitical action.

When the EU border regime produces death on land, it is much more difficult for it to be concealed, or for its evidence to be dissipated across the waves of the Agean and Mediterranean Seas. In fact, death can lead to rare examples of accountability, as was the case with the death of six-year-old Madina Hussiny at the Croatian border in 2017. Madina was travelling into Croatia with her Afghan family to seek asylum in the EU. Instead of being allowed to access asylum procedures, upon apprehension by border police, the family was pushed back along the train tracks into Serbia. In the darkness of night, as the family walked back into Serbia, Madina was hit by a train and killed (The Guardian Citation2020). The Croatian state was found guilty of a number of violations including violations of right to life, but also a violation of Article 4 (Protocol 4) of the European Convention of Human Rights that prohibits collective expulsion, and a violation of Article 34 on the right to individual petition (Amnesty International Citation2021). These rights are routinely transgressed by EU authorities, but the fatal outcome in this case prompted a set of circumstances that led to a court judgement and some limited form of accountability and compensation. Her death, in other words, created political pressure and humanitarian scrutiny.

To be clear, other border deaths in the Balkans and elsewhere have not been the catalyst for accountability, but killing holds the possibility of political pressure in a way that mass injury never can. Indeed, the delivery of non-fatal injuries sustained through pushbacks and their after-effects have in contrast become a routine part of the European border machine: injuries are a feature, not a bug. As we have shown, the right to maim regularly rides roughshod over the liberal remnants of the right to asylum. By disallowing safe alternative routes to asylum, the EU predisposes would-be refugees to the injuries of the pushback and the debilitations of the camp. Taken together, this geography of injury demonstrates how withholding death and producing injury has become a foundation of contemporary bordering. Jumping straight to death as the arbiter of political power risks occluding arguably more pernicious ways that liberal states are attempting to subjugate populations, where ‘maiming becomes the primary vector through which biopolitical control is deployed’ (Puar Citation2017, 135).

We suggest here that the ‘right to maim’ is a useful lens for understanding how injury operates as a political tool. If we pan the camera back from the debilitation of borders, we can see the politics of injury and not ‘letting die’ elsewhere. It appears within the violence of austerity, where the poor are incapacitated but not always killed; it thrives in the toxic geographies of industrial zones, where the slow impacts of pollution are contested and ignored; and it prospers wherever direct killing becomes the only measure of social injustice. While it is vital to remain attentive to the worst excesses of political violence – including death – we must not lose sight of the less-than-deadly harms that are so often the centrepiece of biopolitical action: actions that frequently avoid the optics of public and scholarly scrutiny. Afterall, indifference towards injury and debilitation is precisely what violent states rely upon to sustain their humanitarian pretensions.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to No Name Kitchen for their close collaboration and we thank our anonymous informants for sharing their time, expertise, and testimonies. We thank the participants of the ‘Safe Haven’ workshops at the University of Bern for helping to strengthen the article. Earlier versions of this paper were workshopped at the University of Newcastle’s ‘Power, Space, Politics’ seminar series, as well as at the Department of Geography, University of Sheffield. We particularly thank Leandro Navarro Cabana, Annika Lindberg, Craig Jones, Karolína Benghellab, Deirdre Conlon, Carolin Fischer, Manuel Insberg, Sabine Strasse, and BVMN. We are grateful to the Antipode Foundation for supporting us with a Scholar-Activist Project Award. This paper was made possible through a Research Grant from the School of Geography, University of Nottingham and an ESRC grant [ES/W006170/1]. Finally, we extend gratitude to the Geopolitics editorial team and the anonymous reviewers for their generous guidance and engagement. This paper is written in solidarity with people on the move and with everyone struggling against border violence.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agamben, G.1998. Homo sacer: Sovereign power and bare life. Stanford university Press.

- Alarm Phone. 2021. CommemorAction: Solidarity with the families of the 91 people who disappeared at sea!. Alarm Phone Website. https://alarmphone.org/en/2021/02/09/commemoraction-91-people/?post_type_release_type=post.

- Alonso, A. D., and B. Nienass. 2016. Deaths, visibility, and responsibility: The politics of mourning at the US-Mexico border. Social Research an International Quarterly 83 (2):421–51. doi:10.1353/sor.2016.0036.

- Amnesty International. 2021. Croatia: European Court of Human Rights rules that authorities violated rights of child killed by train after pushback. Accessed November 18, 2021. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2021/11/croatia-european-court-of-human-rights-rules-that-authorities-violated-rights-of-child-killed-by-train-after-pushback/.

- Amoore, L. 2006. Biometric borders: Governing mobilities in the war on terror. Political Geography 25 (3):336–51.

- Aradau, C., and M. Tazzioli. 2019. Biopolitics multiple: Migration, extraction, subtraction. Millennium Journal of International Studies 48 (2):1–23. doi:10.1177/0305829819889139.

- Augustová, K. 2023. The case of migration at the Bosnian-Croatian border. In Migration and torture in today’s world, ed. F. Perocco, 139–60. US: Edizioni Ca’ Foscari.

- Augustová, K., H. Carrapico, and J. Obradović-Wochnik. 2021. Becoming a smuggler: Migration and violence at EU external borders. Geopolitics 28 (2):1–22. doi:10.1080/14650045.2021.1961223.

- Augustová, K., H. Carrapico, and J. Obradović-Wochnik. 2023. Push and back: The ripple effect of EU border externalisation from Croatia to Iran. Environment & Planning C Politics & Space 41 (5):847–65. doi:10.1177/23996544231163731.

- Balkan, O. 2015. Burial and belonging. Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism 15 (1):20–34. doi:10.1111/sena.12119.

- Bergesio, N., and L. Bialasiewicz. 2023. The entangled geographies of responsibility: Contested policy narratives of migration governance along the Balkan route. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 41 (1):33–55. doi:10.1177/02637758221137345.

- Bird, G., J. Obradovic‐Wochnik, A. R. Beattie, and P. Rozbicka. 2021. The ‘badlands’ of the ‘balkan route’: Policy and spatial effects on urban refugee housing. Global Policy 12:28–40.

- Centar za Mirovne Studije (CMS). 2023. ‘Refugees file a lawsuit to the constitutional court of Croatia: More than two years without effective investigation into a brutal pushback case which included sexual assault’. https://www.cms.hr/en/azil-i-integracijske-politike/izbjeglice-zrtve-pushbacka-podnijele-tuzbu-ustavnom-sudu-hrvatske-vise-od-dvije-godine-bez-ucinkovite-istrage.

- Conlon, D. 2010. Ties that bind: Governmentality, the state, and asylum in contemporary Ireland. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 28 (1):95–111.

- Council of Europe. 2019. Council resolution 2299: Pushback policies and practice in council of Europe member states. Accessed June 28, 2019. http://semantic-pace.net/tools/pdf.aspx?doc=aHR0cDovL2Fzc2VtYmx5LmNvZS5pbnQvbncveG1sL1hSZWYvWDJILURXLWV4dHIuYXNwP2ZpbGVpZD0yODA3NCZsYW5nPUVO&xsl=aHR0cDovL3NlbWFudGljcGFjZS5uZXQvWHNsdC9QZGYvWFJlZi1XRC1BVC1YTUwyUERGLnhzbA==&xsltparams=ZmlsZWlkPTI4MDc0.

- Cusumano, E. 2019. Straightjacketing migrant rescuers? The code of conduct on maritime NGOs. Mediterranean Politics 24 (1):106–14. doi:10.1080/13629395.2017.1381400.

- Cuttitta, P., J. Häberlein, and P. Pallister-Wilkins. 2019. Various actors: The border death regime. In Border deaths, ed. P. Cuttitta and T. Last, 35. US: Amsterdam University Press.

- Danewid, I. 2017. White innocence in the black mediterranean: Hospitality and the erasure of history. Third World Quarterly 38 (7):1674–89. doi:10.1080/01436597.2017.1331123.

- Danish Refugee Council. 2021. The Danish refugee council’s submission to the special rapporteur’s report on pushback practices and their impact on the human rights of migrants. https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Issues/Migration/pushback/DRCSubmission-final.pdf.

- Darling, J. 2009. Becoming bare life: Asylum, hospitality, and the politics of encampment. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 27 (4):649–65.

- Davies, T., and A. Isakjee. 2019. Ruins of empire: Refugees, race and the postcolonial geographies of European migrant camps. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 102:214–17. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.09.031.

- Davies, T., A. Isakjee, and S. Dhesi. 2017. Violent inaction: The necropolitical experience of refugees in Europe. Antipode 49 (5):1263–84. doi:10.1111/anti.12325.

- Davies, T., A. Isakjee, and S. Dhesi. 2019. Informal migrant camps. In Handbook on critical geographies of migration, ed. K. Mitchell, R. Jones, and J. Fluri, 220–31. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Davies, T., A. Isakjee, L. Mayblin, and J. Turner. 2021. Channel crossings: Offshoring asylum and the afterlife of empire in the Dover Strait. Ethnic and Racial Studies 44 (13):2307–27.

- Davies, T., A. Isakjee, and J. Obradovic-Wochnik. 2023. Epistemic borderwork: Violent pushbacks, refugees, and the politics of knowledge at the EU border. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 113 (1):169–88. doi:10.1080/24694452.2022.2077167.

- De León, J. 2015. The land of open graves. Oakland, California: University of California Press.

- Díaz-Barriga, M., and M. E. Dorsey. 2020. Fencing in democracy. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press.

- Doty, R. L. 2011. Bare life: Border-crossing deaths and spaces of moral alibi. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 29 (4):599–612.

- ECCHR. 2020. Push-backs in Croatia: Complaint before the UN human rights committee. https://www.ecchr.eu/fileadmin/Fallbeschreibungen/Case_report_Croatia_UN_HRC_Dec2020.pdf.

- European Commission. 2021, Managing migration: EU financial support to Croatia. Accessed February 28, 2023. https://home-affairs.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2021-01/202101_managing-migration-eu-financial-support-to-croatia_en.pdf.

- Fanon, F. 1963. A dying colonialism. US: Grove Press.

- Foucault, M. 1976. “Society must be defended”: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1975-1976. US: Picador.

- Foucault, M. 1978. The history of sexuality, volume 1: An introduction. US: Pantheon Books.

- Fregonese, S., B. Isleyen, J. Rokem, and S. Nanado. 2020. Reading Reece jones’s violent borders: Refugees and the right to move. Political Geography 79:2–9. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2019.102129.

- Gilmore, R. W. 2007. Golden gulag: Prisons, surplus, crisis, and opposition in globalizing California. Vol. 21. Oakland: University of California Press.

- Guardian. 2020. Croatian police accused of spray-painting heads of asylum seekers. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2020/may/12/croatian-police-accused-of-shaving-and-spray-painting-heads-of-asylum-seekers.

- Horsti, K., and K. Neumann. 2019. Memorializing mass deaths at the border: Two cases from Canberra (Australia) and Lampedusa (Italy). Ethnic and Racial Studies 42 (2):141–58. doi:10.1080/01419870.2017.1394477.

- Human Rights Watch. 2022.Violence and pushbacks at Poland-Belarus border. https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/06/07/violence-and-pushbacks-poland-belarus-border.

- Iliadou, E. 2019. Border harms and everyday violence. The lived experiences of border crossers in Lesvos Island, Greece. PhD thesis, The Open University.

- Isakjee, A., T. Davies, J. Obradović‐Wochnik, and K. Augustová. 2020. Liberal violence and the racial borders of the European Union. Antipode 52 (6):1751–73. doi:10.1111/anti.12670.

- Jones, C. 2022. Gaza and the great march of return: Enduring violence and spaces of wounding. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 48 (2):1–14. doi:10.1111/tran.12567.

- Karamandidou, L., and B. Kasparek. 2022. From exception to extra-legal normality: Pushbacks and racist state violence against people crossing the Greek–Turkish land border. State Crime Journal 11 (1):12. doi:10.13169/statecrime.11.1.0012.

- Kovačević, N. 2021. Documenting human rights violations on the Serbian-Croatian border: Guidelines for reporting, Advocacy, and Strategic Litigation. US: Rosa Luxemburg.

- Kovras, I., and S. Robins. 2016. Death as the border: Managing missing migrants and unidentified bodies at the EU’s Mediterranean frontier. Political Geography 55:40–49. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2016.05.003.

- Laakkonen, V. 2022. Deaths, disappearances, borders: Migrant disappearability as a technology of deterrence. Political Geography 99:102767.

- Last, T. 2020. Introduction: A state-of-the-art exposition on border deaths. InBorder deaths. Causes, dynamics and consequences of migration-related mortality, ed. Cuttitta, P.and Last, T.]. Border deaths. Causes, dynamics and consequences of migration-related mortality, 21–33. Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam Press.

- Last, T., G. Mirto, O. Ulusoy, I. Urquijo, J. Harte, N. Bami, M. Pérez Pérez, F. Macias Delgado, A. Tapella, A. Michalaki, et al. 2017. Deaths at the borders database: Evidence of deceased migrants’ bodies found along the southern external borders of the European Union. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43 (5):693–712. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2016.1276825.

- Lindberg, A. 2024. Researching border violence in an Indefensible Europe. Geopolitics 1–20.

- Locke, J. [1690] 1980. Second treatise of government. US: Hackett Publishing Co. Inc.

- Lo Presti, L. 2019. Terraqueous necropolitics: Unfolding the low-operational, forensic, and evocative mapping of Mediterranean Sea crossings in the age of lethal borders. Acme 18 (6):1347–67.

- Mah, A., and X. Wang. 2019. Accumulated injuries of environmental injustice: Living and working with petrochemical pollution in Nanjing, China. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 109 (6):1–17. doi:10.1080/24694452.2019.1574551.

- Mayblin, L., M. Wake, and M. Kazemi. 2020. Necropolitics and the slow violence of the everyday: Asylum seeker welfare in the postcolonial present. Sociology 54 (1):107–23.

- Minca, C., and J. Collins. 2021. The game: Or,‘the making of migration’along the Balkan Route. Political Geography 91:102490. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2021.102490.

- Minca, C., A. Rijke, P. Pallister-Wilkins, M. Tazzioli, D. Vigneswaran, H. van Houtum, and A. van Uden. 2022. Rethinking the biopolitical: Borders, refugees, mobilities. Environment & Planning C Politics & Space 40 (1):3–30. doi:10.1177/2399654420981389.

- Moran, D.2016. Carceral geography: Spaces and practices of incarceration. Routledge.

- Mountz, A. 2020. The death of asylum. US: University of Minnesota Press.

- MUP. 2020. Reaction of the Croatian Ministry of the Interior to the article of the British news portal The Guardian. Press release. https://mup.gov.hr/news/response-of-the-ministry-of-the-interior-to-the-article-published-on-the-online-edition-of-the-british-daily-newspaper-the-guardian/286199.

- Nixon, R. 2011. Slow violence and the environmentalism of the Poor. Harvard University Press.

- OHCHR. 2021. Report on means to address the human rights impact of pushbacks of migrants on land and at sea. United Nations. https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G21/106/33/PDF/G2110633.pdf?OpenElement.

- Pain, R. 2014. Everyday terrorism: Connecting domestic violence and global terrorism. Progress in Human Geography 38 (4):531–50.

- Pallister-Wilkins, P. 2022. Humanitarian Borders. US: Verso Books.

- Papailias, P. 2019. (Un) seeing dead refugee bodies: Mourning memes, spectropolitics, and the haunting of Europe. Media, Culture & Society 41 (8):1048–68. doi:10.1177/0163443718756178.

- Perl, G. 2017. Uncertain belongings: Absent mourning, burial, and post-mortem repatriations at the external border of the EU in Spain. In Final Journeys, 101–16. Routledge.

- Puar, J. K. 2017. The right to maim: Debility, capacity, disability. US: Duke University Press.

- Ralph, L. 2012. What wounds enable: The politics of disability and violence in Chicago. Disability Studies Quarterly 32 (3). doi:10.18061/dsq.v32i3.3270.

- Rexhepi, P. 2022. White Enclosures. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press.

- Round, J., and I. Kuznetsova-Morenko. 2017. Necropolitics and the migrant as a political subject of disgust: The precarious everyday of Russia’s labour migrants. Politics of Precarity 198–223.

- Sajjad, T. 2022. Strategic cruelty: Legitimizing violence in the European Union’s border Regime. Global Studies Quarterly 2 (2):ksac008. doi:10.1093/isagsq/ksac008.

- Sandset, T. 2021. The necropolitics of COVID-19: Race, class and slow death in an ongoing pandemic. Global Public Health 16 (8–9):1411–23. doi:10.1080/17441692.2021.1906927.

- Sanyal, D. 2019. Humanitarian detention and figures of persistence at the border. Critical Times 2 (3):435–65. doi:10.1215/26410478-7862552.

- Schinas, M. 2022. Croatia to join schengen area & eurozone on Sunday, January 1, Schengen Visa News: https://www.schengenvisainfo.com/news/croatia-to-join-schengen-area-eurozone-on-sunday-january-1/

- Schindel, E. 2022. Death by ‘nature’: The European border regime and the spatial production of slow violence. Environment & Planning C Politics & Space 40 (2):428–46.

- Shewly, H. J. 2013. Abandoned spaces and bare life in the enclaves of the India–Bangladesh border. Political Geography 32:23–31. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2012.10.007.

- Sparke, M. 2017. Austerity and the embodiment of neoliberalism as ill-health: Towards a theory of biological sub-citizenship. Social Science & Medicine 187:287–95. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.12.027.

- Sparke, M. B. 2018. Welcome, its suppression, and the in-between spaces of refugee sub-citizenship–commentary to Gill. Fennia-International Journal of Geography 196 (2):215–19. doi:10.11143/fennia.70999.