ABSTRACT

Goat raising has increased in Lao People’s Democratic Republic due to meat demand from Vietnam. Goat production is low input using free grazing and minimal husbandry. Technical constraints are well known but socio-cultural contexts are poorly understood. This paper describes qualitative research on farmer’s motivations, experiences and learning pathways, to improve goat husbandry. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 30 smallholder goat farmers in Lao’s South-Central province of Savannakhet. The interviews revealed that farmers relied on their experiences and observations of goat raising in their communities to make their management decisions. Trial and error was a valued learning strategy. Farmers took guidance from the exchange of goat raising experiences with other goat farmers and preferred participatory learning that fostered discussion in familiar village settings. Lao smallholder goat farming systems are a product of compromise across a number of resources. Project interventions that required low investments of labour, land or capital were most readily implemented and adapted by farmers. This study questions the assumption that project interventions are inherently optimal and beneficial for smallholder farming systems. Recommendations propose how farmer’s experiences, constraints and preferences can be incorporated into development approaches to ensure management system changes reflect the desires of smallholder farmers.

Introduction

Goat numbers are increasing throughout developing countries, where approximately 90% of the global goat population is found (Utaaker et al., Citation2021). Goats are often raised by smallholder farmers, characterized by limited capital and land, reliance on family labour, and a mix of crops and small livestock numbers. Goats require fewer inputs than cattle and buffalo, and are reported to be more easily managed by smallholder farmers, particularly women (Burns et al., Citation2018; Windsor et al., Citation2018). Thus goats are often an entry point into ruminant ownership for the rural disadvantaged (Windsor et al., Citation2018).

Goats provide benefits to smallholder farmers such as manure to fertilize crops, a vital source of income and occasionally, as meat protein (Burns et al., Citation2018; Windsor et al., Citation2018). Goats can provide these benefits across a wide range of adverse environmental conditions, which makes them a sustainable and strategic choice of livestock species for many resource constrained, smallholder farmers (Torres-Hernández et al., Citation2022). Qualitative research has also identified social benefits and uses of livestock amongst smallholder farmers, which have often been overlooked in agricultural research and development (Hunter et al., Citation2022). For instance, goats are commonly involved in customs related to weddings and funerals, either as a form of dowry, or are kept and sold specifically to fund a variety of ceremonial costs (Adeleye et al., Citation2016; Oluka et al., Citation2005; Peacock, Citation2005). In addition, goats are often slaughtered as sacrificial offerings during religious rituals and celebrations (Jansen & van den Burg, Citation2004; Tefera, Citation2007; Zaibet et al., Citation2004). Goats are often treated as a cash substitute that can be quickly liquidized to meet sudden household expenses, such as the payment of medical bills, school fees, funeral and ceremonial costs, or the repayment of loans (Ørskov, Citation2011; Peacock, Citation2005). Hence, goat raising helps smallholders satisfy a range of socio-cultural obligations and are not purely economically purposed.

Recently, Lao People’s Democratic Republic (Laos) in South-East Asia has seen a rapid increase in goat numbers, with the goat population doubling (215,600–550,000 goats) between 2011 and 2019, due to increased demand for Lao mountain goat meat from Vietnam (Gray et al., Citation2019). A survey of 503 Vietnamese goat consumers revealed that 45% were willing to pay an average 15% price premium for Lao mountain goat over other goat breeds available in Vietnam (Morales et al., Citation2023).

Two-thirds of Laos’ total human population resides in rural villages, where the highest rates of poverty are concentrated (The World Bank, Citation2020). In rural villages, 90% of households are considered to be farming households; engaged in crop, livestock and/or aquaculture production (Millar et al., Citation2022; The World Bank, Citation2022). Recent research shows Lao rural households in the South-Central province of Savannakhet are benefitting from the expanding goat trade, with goat raising households receiving just under a third of household income (27.9%) and 40.6% of total farm income from goat sales (Millar et al., Citation2022).

Lao smallholder farmers have the opportunity to improve their goat husbandry practices to capitalize on the economic opportunity associated with this growing sector. However, little is known about household motivations, experiences or capacity to improve goat husbandry and production. Most research to date has focussed on goat production systems, disease prevalence and productivity indicators in Laos. Lao smallholders typically raise goats in ‘traditional’ production systems, characterized by low inputs and low to moderate productivity. Free range is the most common management system where goats freely browse on leaves and native grasses as well as other plants in forests, fallow land, road sides or rice paddy fields post-harvest (Phengsavanh, Citation2006; Windsor et al., Citation2018; Xaypha, Citation2005). Herds are typically small (3–10 goats) and are kept in goat houses overnight (Windsor et al., Citation2018).

Main constraints to increasing goat productivity in Laos are inadequate nutrition and feed availability, high prevalence of diseases (Orf disease, diarrhoea, bloat) and internal parasites, and poor management practices, often exacerbated by the low literacy and educational status of Lao farmers (Millar et al., Citation2022; Phengvichith & Preston, Citation2011; Windsor et al., Citation2017; Windsor et al., Citation2018). While these assessments correctly identify technical constraints, they overlook socio-cultural contexts that underpin farmer ability to overcome them.

Sociological research on goat production in Laos is lacking. Gray et al. (Citation2019) noted knowledge gaps regarding how Lao farmers acquire goats, negotiate goat ownership rights and allocate goat management activities between household members. There was limited understanding of the productive and non-productive purposes of goats, the relative importance goats have across gender and age cohorts, as well as the extent goats assist households to cope with economic shocks (Gray et al., Citation2019). These factors may affect Lao smallholder capacity to implement or adapt improved husbandry practices.

The capacity to address the aforementioned constraints to increase goat productivity and improve livelihoods throughout Laos has remained variable across government and Non-Government Organisation (NGO) initiated projects. There is little evidence demonstrating long-term use of improved management practices once development projects conclude (Gray et al., Citation2019; Millar & Photakoun, Citation2008). The general perception is that Lao goat production systems remain relatively static and traditional, despite the increased market opportunity (Gray et al., Citation2019). This phenomenon may be partially attributed to the underlying assumption that recommended practices are inherently beneficial for smallholder farmers, without adequate supporting evidence.

‘Top-down’ approaches, whereby villagers were recommended interventions without participation in decision making, have contributed to farmers reverting back to traditional practices past the project’s close (Asian Development Bank, Citation2015). Projects with a strong focus on technical assistance, but little regard for ‘social and participatory dimensions’ have favoured larger ruminants over goats, and primarily benefited wealthier families to the exclusion of disadvantaged households, women, and some ethnic groups (Asian Development Bank, Citation2015). Project impacts have suffered from a lack of extension strategies with specific reference to gender, ethnic and socio-economic factors of Lao farmers (Asian Development Bank, Citation2015). Other development projects have neglected to address important social factors determining uptake of recommended practices, including labour requirements and shortages, leadership structures and group solidarity, and clarity of objectives (Keonakhone et al., Citation2009). Too often, emphasis is placed on whether farmers accept or reject recommended practices, as opposed to how they learn and adapt interventions to suit their individual contexts (Glover et al., Citation2016; Karnowski et al., Citation2011).

This paper describes qualitative research on farmer’s goat raising motivations, experiences and learning pathways, to improve goat husbandry. Research questions guiding the study were (1) what are farmer motivations and experiences with goat raising? and (2) how do they learn about goat raising and what are their preferred learning pathways? The study was conducted as part of the ‘Goat Production Systems and Marketing in Lao PDR and Vietnam’ (LS-2017/34) research for development project. The LS/2017/34 project was funded by the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) and led by the University of New England (UNE), Australia, and the National Agriculture and Forestry Research Institute (NAFRI), Laos. The LS/2017/34 project worked with 70 smallholder goat farming households, across 7 villages in Savannakhet province (10 households in each village), to trial goat husbandry improvements. The seven LS/2017/34 villages were located across three districts in Savannakhet province, which holds the largest proportion of Laos’ goat population (26%; MAF, Citation2014). The seven villages were randomly selected based on the criteria that (a) villages had many goats (minimum of 80 goats), (b) at least 10% of households within the village owned goats and (c) the village leader, committee and farmers were willing to participate in the four-year project. Households were selected based on the criteria that households (a) had at least five goats, (b) were interested in participating and (c) had labour and land to support adoption of selected husbandry interventions. For a more detailed rationale behind the LS/2017/34 projects’ selection of study site and beneficiaries, refer to (Phengvilaysouk et al., Citation2022).

Staff visited households every month and conducted hands on training in forage plot establishment to supplement goat nutrition, use of mineral blocks, veterinary treatments and elevated goat housing with slated flooring to improve hygiene. The project commenced in July 2019 and concluded in December 2023. More information on the project is available at https://www.aciar.gov.au/project/ls-2017-034. This study aimed to provide in-depth understanding of farmer experiences prior to and during the project, to inform and improve project approaches.

Methods

Study design and site

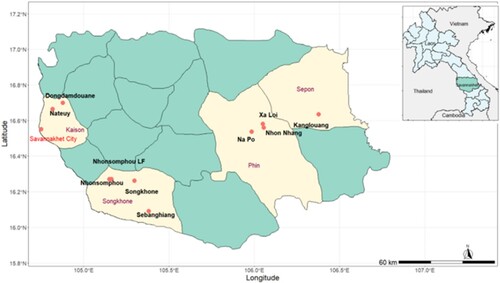

The study purposefully selected participant households from a subset of five of the seven LS-2017/34 project’s target villages in Savannakhet province (). The subset was selected to (1) eliminate repetition of village characteristics, (2) reduce the time and resource demands of travelling to all LS/2017/34 villages and (3) prioritize depth of insight into sociological factors within the household, as opposed to breadth of insights across as many villages as possible. The subset of villages was purposively selected to ensure maximum diversity across village characteristics and social contexts (). The data used to inform this purposeful selection was derived from a structured survey of all households at the commencement of the LS-2017/34 project (Olmo et al., Citation2022). This structured survey was conducted separate to this study by the LS/2017/34 project. For a detailed description on the structured survey design and implementation procedure, refer to Phengvilaysouk et al. (Citation2022).

Figure 1. Location of study villages. Note. Figure copied from Le et al. (Citation2024) with permission from author.

Table 1. Main characteristics of village subset selected for household sampling.

Household selection

Using a stratified sampling technique, participant households from the subset of five villages were divided into (1) project goat raising households and (2) mon-project goat raising households. The aim of this stratification was to explore important differences between the cohorts and the influence of the project on farmers. From each of the five villages, three households were purposively selected from each strata. As this study aimed to account for human behaviour across as many different social contexts as possible, project raising households were selected purposively for maximum diversity in their goat herd sizes, years of experience raising goats, proportion of household income from goats, reported reasons for raising goats, management and grazing strategies, reported constraints and share of goat management between household members. Other features included ethnicities, years lived in the village, number of household members, gender and age ratios, farm areas owned and rented, access to other farm and off-farm resources, rates of labour hire and sources of information and animal health services. This information was available from the same structured survey conducted by the LS-2017/34 project prior to this study (Olmo et al., Citation2022).

Baseline household data was not available to inform the purposeful selection of non-project goat raising households. For this reason, a simple random sampling method was used to select three non-project goat raising households across all five villages, provided they met the criterion of owning at least five goats, and had at least first year of experience of raising goats. Given that baseline household data was not available to sample purposefully, simple random sampling was assumed to be the most practical means for maximising diversity across non-project households. This study design culminated in 30 goat farming households across 5 villages within Savannakhet province (15 project goat raising households and 15 non-project goat raising households). A sample size of 30 households is typical of other previous studies that utilized semi-structured interviews as their main method of data collection, within Laos, which cite sample sizes of 32–45 households (Bardosh et al., Citation2014; Bonnin, Citation2015; Millar, Citation2021). It was also appropriate given the time and resource constraints, and the availability of project staff and translators to accompany researchers on village visits.

Ethical approval

This study was granted ethical approval by the University of New England Human Research Ethics Committee (UNE HREC) Chair on 21 June 2022. The ethics approval number is HE22-102. Participants provided consent by signing consent forms which were given to them prior to participating in any audio recorded interviews. Consent forms were provided in Lao language and were accompanied by a Lao language information sheet which outlined the details and purpose of the study. Participants consented to a 15-minute observation of their farm in which researchers could make notes and take photos of the farm. Participants consented to participation in an audio recorded interview lasting between 1 and 1.5 hours. Consent to quote and publish participant responses anonymously or using pseudonyms was also obtained. Participants had to be 18 years of age, or older, to be included in the study.

Data collection and analysis

Semi-structured interviews were used to collect data from 30 smallholder Lao goat farmers. Interviews were conducted face-to-face in Lao language, with the assistance of an interpreter who was fluent in both the Lao and English language. Interviews were conducted with a single member of the household who volunteered to be interviewed, in their house. The semi-structured interviews were comprised of 20 open ended questions (see Appendix 1) directly related to the aforementioned research questions. The interviews were audio recorded with the consent of all participants and translated and transcribed into English transcripts.

Data was analysed using a Grounded Theory methodology (GTM). GTM is an exploratory, inductive process, beginning with open ended questions and no prior hypotheses. Scientific rigour is maintained by the absence of hypotheses prior to data collection, as this by prevents the researcher from being biased in their construction of emergent theories in qualitative studies (El Hussein et al., Citation2014; van Veggel, Citation2021). Instead, findings are grounded in the dataset and emerge during subsequent analysis, as opposed to being formulated prior to data collection, before being confirmed or rejected following data collection (Kelle, Citation2007).

This study employed GTM in coding and analysing interview transcripts for emergent themes arising from farmer responses to semi-structured interview questions. The NVivo 12 software program, designed for qualitative analysis of unstructured text, was used to assist this process of coding and analysis. In qualitative research, ‘saturation’ is referred to as the point at which emergent themes are considered to have been fully developed (Saunders et al., Citation2018). Repeated identification of the same emergent themes during analysis signifies that ‘saturation’ has been reached and emergent themes are fully developed (Glaser & Strauss, Citation1999). Sampling as diversely as possible ensures that emergent themes do not require more data collection, as the saturation point will be based on the widest range of data available (Saunders et al., Citation2018). The sub-headings in the results section of this paper represent saturated themes.

Farmers were free to discuss whichever goat raising motivations, experiences and preferred learning pathways that occurred to them at the time of interview. The researcher occasionally ‘probed’ farmers to elaborate on answers they had previously given (see Appendix 1). To avoid bias, interviewers refrained from directing farmers’ answers towards particular features of goat raising that were not raised by the farmers themselves. The results section of this paper reports the number of farmers that discussed particular motivations, experiences and preferred learning pathways. Due to the non-binary nature of interview questions and farmer responses, readers should not interpret the number of farmers that did not discuss a particular aspect of goat raising as having opposing views to the cohort of farmers that did discuss the relevant aspect of goat raising.

Results

Household demographics

There were 16 males, 9 of which were registered in the LS-2017/34 project (project farmers) and 7 non-project farmers (). There were 14 females, 6 of which were in the project and 8 were non-project farmers (). The average age of farmers interviewed was 45 years, ranging from 18 to 70 years, with project farmers slightly older than non-project farmers (). The study included farmers from four ethnic backgrounds: Lao Loum (13 farmers), Mong Khong (10 farmers), Phu Tai (5 farmers) and Brou (2 farmers).

Table 2. Gender, ethnicity and ages of farmers interviewed for project and non-project cohorts.

Farmer households had an average of four members with households ranging from two to eight household members (). Project farmers had slightly more household members and children than non-project farmers (). Households owned an average of 14 goats with herd sizes ranging from 5 to 37 goats (). On average, project households owned more goats than non-project households with average herd sizes of 8 goats and 11 goats, respectively (). Project households also had more experience raising goats than non-project households (). The average number of years that farmers had raised goats for was 7 years ().

Table 3. Household demographics of interviewed farmers.

Establishing a goat enterprise

Farmers initiated goat raising by observing others and encouragement from friends

The majority of farmers (70%) were influenced to try raising goats from observing other farmers within the community who successfully raised goats. There was no difference in this influence across project and non-project farming cohorts. Their motivations were to emulate their neighbours and/or to gain the benefits they saw their neighbours deriving from goat raising. Farmers observed other goat raisers experiencing improvements in their livelihoods as a result of raising goats. For example, some farmers observed other goat raisers being able to buy more food, new clothing, and materials to construct houses after they had begun to raise goats. In the quote below, one farmer described how other goat farmers had used their goat income to re-invest and improve upon their current farming system:

Some households were able to sell 10–20 goats and used that generated income to buy buffaloes. Some of them were able to build a new house and a plough for their paddy fields. That’s why I wanted to raise goats … 49-year-old male project farmer, Xaloi village

Eight farmers (27%) were influenced to raise goats by direct encouragement of family and friends who advocated the benefits of raising goats. Six of these farmers were project farmers. The ease with which goat raisers managed their goats in low-input, free-range management systems, was a key motivator for farmers to try raising goats themselves. This observation, with the added benefit of goats reproducing quickly, led some farmers to believe that goats would be better to raise than larger livestock species, such as cattle and buffalo.

Most farmers did not have to buy their goats

For a variety of reasons, 63% of farmers did not pay money to acquire their first goats. For instance, gifting goats was common amongst family and friends. Goats had been received as gifts by eight farmers. Six of these farmers were non-project farmers. In addition, six farmers (3 project, 3 non-project) reported previously gifting their goats to other family members or friends in the past. Five other farmers did not have to pay for their first goats as they received them free-of-charge as part of a previous development project in Xaloi and Napo villages. Three of these previous project beneficiaries were now registered to the current LS-2017/34 project. Of these five previous beneficiaries, four lived in Xaloi village and one lived in Napo village. Whilst these farmers were not required to pay for their goats, they were expected to give half of their goats’ offspring to other farmers within the community, as part of a revolving goat fund scheme. Similarly, one farmer arranged to repay his parents for the goats they had given him by returning half of his goats’ offspring in the next generation.

When farmers did pay for their first goats, they financed their acquisitions via several pathways. Family members were relied upon to provide five farmers (3 project, 2 non-project) with enough money to afford their goats. For three of these farmers, it was their children who provided them with the required funds, which they sent back from working abroad.

The sale of vegetables or smaller livestock, such as chickens or ducks, raised funds to buy goats for eight farmers (4 project, 4 non-project). Two farmers bought their goats with money they had saved from paid work. One farmer received his first goat as a result of his neighbour being unable to repay a loan to him as explained here:

Around that time, the neighbour’s child was hospitalised, so he borrowed 70,000 kip from me to cover his child’s medical expenses. After that, he had no money to return me, so I asked him whether he could possibly give me a goat in return. Then he agreed and gave me one doe in return. 54-year-old male project farmer, Napo village

Early challenges and knowledge gaps

Goat disease is an early and persistent challenge for farmers

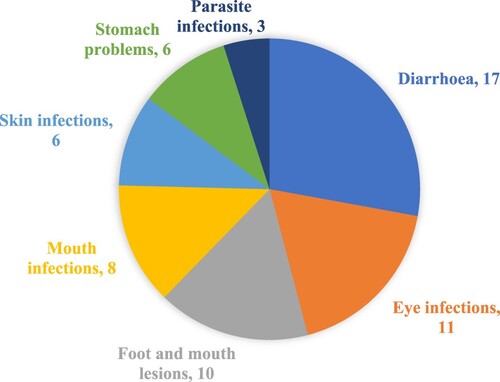

Goat disease was the main challenge that goat raisers faced when establishing their enterprises. This was true for both project and non-project farmers. Disease was a key concern for 80% of interviewed farmers, particularly when beginning to raise goats. For these farmers, symptoms of goat disease persisted amongst their herds over time. However, the frequency and severity of disease often declined over time, as farmers became accustomed to goat management and disease treatment strategies. Goats tended to have multiple morbidities which were linked to age and season. presents the frequency of disease symptoms, reported by farmers. Some farmers recalled being unsure of how to diagnose or treat their goats’ diseases in their early establishment period, resulting in reduced productivity and/or death of their goats. Farmers often reported that managing goat disease was the hardest part of raising goats, as exemplified by one farmer who experienced more disease symptoms as she began to establish and expand her goat herd:

In the beginning, we did not have any problems, until we had about 10 goats. Then they had problems, they had diarrhea, sore eyes and some of them became blind … they got sick very quickly, they always had diarrhea and sore eyes. 23-year-old female non-project farmer, Xaloi village

Project farmers reported that their goats experienced eye infections more frequently than non-project farmers. Seven project farmers’ goats had experienced eye infections as opposed to only four non-project farmers’ goats. Project farmers reported more instances of stomach problems with their goats. Only one 57-year-old female non-project farmer from Sebanghiang village reported that her goats had experienced stomach problems. Similarly, only one 55-year-old male non-project farmer from Nhomsomphou village reported that his goats had experienced skin infections. There were no notable differences across project and non-project farming cohorts regarding other disease symptoms.

Some farmers struggled to supervise their goats in free-range systems

Early in the establishment process, goats were difficult to supervise in free-range systems for four farmers (2 project, 2 non-project). Farmers were not able to supervise their goats all day long, due to other commitments and livelihood activities. Coupled with the long distances that goats roamed when in free-range grazing conditions, this meant that goats often became lost or involved in accidents and did not return to the goat house. Two farmers addressed this issue by tethering their goats when letting them out to graze, as described in the quote below:

‘When I first raised them, they were difficult to manage, they liked to go into other villagers’ areas. So, I had to hire others to raise them for me (on separate land).’ 50-year-old female non-project farmer, Nhomsomphou village.

Farmers had knowledge gaps around breeding management

Knowledge gaps around goat breeding management were exhibited by twelve farmers. Multiple farmers reported that their bucks mated with their own mothers, and close female relatives in an uncontrolled manner. Bucks were free to randomly mate with other farmers’ goats in the same village enabled by a lack of castration or confining of goats. In some instances, farmers believed that inbreeding was the most effective way of preserving good genetics within their herd, as exemplified in this quote:

If the kids are healthy, I will mate the kids with their mom. The does then reproduce some beautiful kids as well. When the kids are 5–6 months old, I can sell them. If I mate my doe with other farmer’s goat, the doe does not reproduce good kids as I wish. 54-year-old male project farmer, Napo village

Farmers relied on these methods to increase their herd numbers. Farmers did not tend to purchase more goats once the farmer had acquired their first few goats. Only four of the farmers who expressed breeding management knowledge gaps were non-project farmers, whilst the remaining eight were project farmers. Only one non-project farmer from Nhomsomphou village reported having learnt about the risks of inbreeding in a brief exchange with project staff on a village visit:

‘I often have to change to a new breeder … They (project staff) just said that if we keep the breeder for a long time, the goats will give birth to unhealthy baby goats.’ 55-year-old, male non-project farmer, Nhomsomphou.

Another non-project farmer had arranged to borrow a buck from his friend for mating, however, this practice was discontinued after his own goats gave birth to a buck of his own. The same farmer was sceptical of cross-breeding his goats because he believed it would be too costly.

Learning to raise goats

Farmers learned how to raise goats via three main strategies (1) independently, (2) socially and (3) from the project. Importantly, most farmers employed multiple strategies throughout the learning process, as opposed to learning via one strategy exclusively. Farmers often informed and enhanced their learning via one strategy in combination with lessons they had taken using other strategies.

Independent learning

Farmers were sometimes reluctant to seek management advice

A reluctance to seek advice about goat management from other community members or project staff was exhibited by 70% of farmers. There was no notable difference in levels of reluctance between project and non-project cohorts. This behaviour was most prominent when farmers had only just begun to raise goats. Levels of farmer reluctance to seek advice were variable over time and was often dependent on farmers’ proximity and frequency of interaction with other goat raisers and project staff. Some farmers did not feel the need to ask for advice or were not willing to initiate contact with other farmers. Six of these farmers (3 project, 3 non-project) went as far as to copy the management strategies they observed other goat raisers adopting within their community, without initiating any direct contact with them, as expressed in the quote below:

‘I did not learn from anyone. I saw that villagers raised goats by free range, so I let the goats out to eat outside too.’ 65-year-old female non-project farmer, Sebanghiang village

Trial and error was a popular learning strategy

In place of advice from other goat raisers, both project and non-project farmers commonly adopted a trial and error approach to learning about optimal goat raising strategies. Fifteen farmers (9 project, 6 non-project) experimented with different management strategies, assessed the outcome, and then decided whether to continue, modify or abandon them, based on their level of success. One farmer provided an example of trial and error with her goat feeding strategies:

I think I will make the goat food tray higher with steel, so they can eat well. If I put it on the ground they will step on it and won’t eat. I saw it when I hung grasses on the trees. The goats would eat a lot, but when I put it on the ground they step on the feed and don’t eat much. 60-year-old female project farmer, Nhomsomphou

Innovative practices, which included the development of new management strategies, such as alternative ways to administer supplements, formulate and administer feeds, and re-appropriate housing facilities normally reserved for other livestock species, was exhibited by five farmers. Only one of these farmers was a non-project farmer and had developed a strategy to administer salt to her goats through a bowl punctured with holes. This technique reduced spillage and waste. Another farmer was particularly innovative in his approach to goat raising, developing alternative treatment strategies and cost-effective feed formulations of his own:

For goat feed, I prepare it by myself … I just wanted to experiment by myself because the feeds that the staff suggested were quite costly … I sometimes mix rice brans with cassava … two bowls of rice brans, molasses and water … Yes, it was much cheaper. 63-year-old male project farmer, Nhomsomphou village

Importantly, this trial and error approach continued as project farmers started implementing project interventions and was often incorporated alongside other learning strategies.

Social learning

Farmers learnt through informal discussions in familiar village settings

Whilst the majority of farmers exhibited a reluctance to seek advice at some stage throughout their history of raising goats, their reluctance was often transitory. At other times, farmers reached out to members of their community to learn about goat management. Farmers were able to conduct informal discussions in familiar village settings, whereby farmers could exchange their own knowledge and experiences of raising goats:

We exchanged information when we met each other in either a village’s meeting or occasionally met. Before the implementation of the project, we discussed the general situation of the goats. Sometimes, we exchanged some advice on how to treat goats, for example, the kind of medicine to use with goats, kinds of leaves to boil for a treatment. 54-year-old male project farmer, Sebanghiang

Farmers learnt from other farmers in their community

Farmers’ social networks assisted the learning around goat management of 14 farmers (47%). Farmers typically learnt from a combination of different members within their community. Interestingly, of the farmers that had learnt via this strategy, 10 (71%) were non-project farmers. Thirteen of these farmers had exchanged knowledge about goat management with other goat farmers within their community. Seven of these farmers reported seeking advice from village veterinarians or veterinary shop workers, as described in the quote below:

He was a vet of the village. He came to inject cows and buffaloes. When I asked him to treat my goats for the first time I paid him for it. Then I memorized what kind of medicine he used and how he injected the goats. Later, when my goats got sick again, I just went to the pharmacy to buy medicine and injected the goats by myself. 57-year-old female non-project farmer, Sebanghiang village

Senior authority figures within the community provided advice on goat management to four farmers. One farmer had even learnt from goat traders and explained that it had been passed down through social networks over past generations. Social learning resulted in the spread of both project-interventions and traditional or locally innovated management practices. There were also instances of knowledge exchange between non-project farmers and project registered farmers as indicated here:

I used to discuss how to treat diarrhea. I used to tell the non-project farmers about what I learned from the project. For example, I told them how to treat goats when they got sick. More than that, I also got medicines from the project and applied to the goats by myself. Sometimes, my neighbours asked me as a favour to treat their goats. 32-year-old male project farmer, Xaloi village

Of the 14 farmers who learnt via their social networks, 10 reported having discussed goat disease, including effective diagnosis, appropriate use of medicines and injection technique. Seven respondents also reported having learnt about how to manage their goat house, including how to build and clean it. In rare instances, misinformation was spread via social networks. For example, one 35-year-old male project farmer from Kanglouang village was suspicious of commercial drugs, and discouraged non-project farmers from using them.

Project learning

Farmers were positive about their interactions with the project

The majority of project farmers expressed positive sentiments about their interactions with the project, and often attributed improvements in their goat management to learning from project staff. There were no negative sentiments expressed by farmers regarding their involvement with the project. Four non-project farmers also reported having learnt about goat management from project staff. This occurred in passing whilst project staff were conducting village visits. Both project and non-project farmers expressed a preference for learning in village settings, with project staff demonstrating treatment protocols and giving management advice as expressed in the quote below. It provided farmers with practical examples that they could subsequently practice themselves:

When the project staff came to our village, most of the villagers joined the meeting and talked about the good aspects of raising goats … In this meeting we talked about (forage) cultivation and livestock. Sometimes, the 10 targeted households attended the meeting and discussed how to raise goats, injection, treatment, forage plotting and how to keep goat pens clean. 49-year-old male project farmer, Xaloi village

In total, 12 farmers recounted learning about preventative measures for disease from project staff, as well as how to administer medicine and anthelmintics and determine the correct dosage. Eight of these farmers were project registered farmers, whilst four were non-project farmers. Disease treatment was the most popular topic which non-project farmers reported having learnt about from project staff. Farmers reported seeing improvements in their goats’ health and productivity over time, following the projects’ intervention. Some project staff had also advised farmers on traditional treatments, most likely as a way to cut costs or treat animals in the circumstances that farmers did not have medicine. One farmer described the improvements in her goat management she had experienced since interacting with the project:

The project taught about diseases like foot and mouth infections or flatulence and how to treat the goats. Then the project came to teach how to take care of the goats such as what or when I should feed them to avoid flatulence. Since the project came I know how to manage my goats, like feeding them with bran or treating with medicines. I have to plant grass, put in a mineral box and build a taller goat house … 60-year-old female project farmer, Nhomsomphou village

Goat house management was the second most mentioned topic, with nine farmers (7 project farmers, 2 non-project farmers) attributing their learning from project staff. Five farmers, all of which were project registered, reported learning about forage management from project staff. Five farmers also reported learning about goat nutrition, two of which were non-project farmers.

Formal training courses were not popular

Formal project training courses were not mentioned as the primary mode by which farmers received advice from project staff. The two farmers that mentioned the training courses conducted by the project, explained that the main goat raisers of the household often opted to send other members of the household to attend the training course, when they lacked time or were occupied with other activities. In the past, these two farmers had attended the training courses but reported that they were often unable to recall or relay the information they were given, as recounted by the following farmer quote:

At first it was me who came to interact with the staff because I registered but when I had to go to the rice field to look after my goats and cattle, I didn’t have time to interact with them, so my husband went instead … he didn’t remember much because the staff asked many questions and taught a lot. When he told me, I couldn’t understand … we didn’t get any information sheets. They only taught by words. 54-year-old female project farmer, Napo village

Some farmers depended on the project for resources

A reliance on the project to sustain or expand their goat enterprises via the provision of resources was indicated by 11 farmers. Two of these farmers were not even registered with the project. Three project farmers even suggested that their initial motive for registering with the project was to receive resources and materials. Five farmers were hoping the project would provide them with materials to upgrade their goat houses. Four project farmers indicated that they relied on the project to provide them with medicines in order to treat their goats. Another three project farmers relied on the project to provide them with seeds for forages. A 35-year-old project farmer from Kanglouang village even enquired as to whether the project could provide him with a new breeding buck. Another 60-year-old female project farmer asked if the project could provide her with machinery to cut her grasses. Some farmers appeared to be delaying action on implementing project interventions until they had been provided with the necessary materials, as opposed to sourcing them for themselves as highlighted in this quote:

I have not adopted the pen strategy because they (project staff) said that they would support, so I have been waiting for them … I have heard that the project would provide roofing, so I would like to request for that as well. If I get it I will build a new pen. 35-year-old female project farmer, Napo village.

Barriers to improving practices

Half of all interviewed farmers reported a number of barriers that prevented them from being able to fully implement project interventions. The primary reasons farmers gave for not being able to use some of the practices were: insufficient capital, land and available labour. A lack of available labour prevented eight farmers (5 project, 3 non-project) from being able to manage the planting and maintenance of forage plots. Five farmers (4 project, 1 non-project) explained that insufficient capital prevented them from investing in upgrading their goat houses, as well as buying fencing materials to protect their forage plots. Four farmers (2 project, 2 non-project) felt they could not plant forage plots or increase their goat herd sizes simply because they did not have enough land. Farmers often faced a combination of these challenges. For instance, a 42-year-old female project farmer from Sebanghiang village, who managed goats on her own, was limited in her ability to adopt a cut-and-carry feeding system by labour constraints. She was also unable to establish a forage plot due to a lack of available land. Another farmer, who was managing goats primarily to buy medicines for his sick wife, who was immobile and unable to assist in the management of the goats, was constrained by insufficient labour and funds, as exemplified in this quote:

I want to follow their (project staff) advice, but I somehow have financial difficulties. I have land, but I don’t have enough money … I could not follow the instruction of pen building because I don’t have many goats. The area for forage plotting is also not consistent with the instructions … I planted the forage in my land, however, the forage was no longer growing during the dry season because no one watered them … I have a plan to plant forages during the rainy season, but I don’t have money to build fences … I want to, but the problem is I don’t have money … 54-year-old male project farmer, Napo village

Discussion

Relative to raising other livestock species, raising goats is a relatively new venture for most Lao farmers. Farmers most commonly made the decision to raise goats based on observations of other goat raisers and their goats within the community. The high productivity of goats in addition to their ease of management in low-input, free-range systems motivated farmers to raise goats. Farmers employed low-cost management systems based on free-grazing, uncontrolled mating and traditional disease treatments. In the absence of technical assistance, farmers learnt about goat raising experientially using trial and error. Farmers also valued the exchange of their goat raising experiences with other goat farmers, to inform their management strategies. The LS-2017/34 project has benefited project farmers and some non-project farmers. The project assisted farmers in improving goat husbandry with positive benefits for goat health and household income. Learning with the project occurred in a village context which satisfied farmers’ preferences to learn in familiar settings. These factors contributed to farmers’ positive review of the project and its impacts.

However, farmers were still constrained by capital, labour and land limitations. Wherever possible, farmers avoided spending money on goat purchases or management. Most farmers relied on uncontrolled mating of their goats in free-range systems, to increase their herd numbers. Insufficient capital restricted some farmers from improving facilities that required materials and infrastructure, such as goat housing. This was also observed by Sabapara et al. (Citation2014) in South Gujarat, India, where 83% of farmers (n = 250) identified high construction costs as the major barrier to improving their goat houses. Similarly, in Uttar Pradesh, 33% of respondents (n = 131) reported a lack of money as inhibitory to constructing goat sheds (Mohan et al., Citation2016). A lack of capital also resulted in two farmers from the study not attempting to grow forages because they could not finance the fencing needed to prevent grazing during establishment, even if they had adequate labour.

Labour constraints prevented some farmers from cultivating forages and employing cut and carry feeding systems. Concentrate supplementation is an alternative feed source to cultivated forages, but has high costs and may be prohibitive to farmers who are also experiencing capital constraints. Sabapara et al. (Citation2014) found that 87% of goat farmers in South Gujarat, India, found the high price of feed concentrates as a major constraint to improving goat feeds. Gill et al. (Citation2022) found that high costs of concentrates feeds ranked as the most common constraint amongst 120 goat farmers in Rajasthan, followed by a lack of grazing area, which ranked third. The results of this study showed that farmers will alter recommended feed rations to reduce costs, and the consequences of this should be considered, especially if the intended benefits may be nullified.

Insufficient land to grow forages without impinging on rice cultivation was another constraint mentioned by some households. This finding has been demonstrated in Uttar Pradesh, India, with Mohan et al. (Citation2016) identifying that 60% of farmers reported a lack of grazing land as a primary constraint to adopting improved goat management practices. Zereu and Lijalem (Citation2016) also found that land shortage was the most common constraint to adopting improved forage cultivation in Southern Ethiopia (n = 225).

Improved husbandry practices that require low amounts of labour, capital and land to implement, whilst still increasing goat productivity, therefore may be preferable. For instance, mineral blocks were widely used by farmers in the project. Some farmers believed the mineral blocks even reduced labour by enticing goats to return to the goat pen after grazing in the afternoon. Interest in goat disease treatment was also unanimous amongst farmers. Medicines were provided to farmers by project staff at subsidised prices or free of charge. Disease treatment protocols required less labour, capital and land to implement.

We found that smallholders modified practices to decrease labour requirements and costs using trial and error, and innovation. For example, farmers unable to fund the construction of new goat houses, repurposed sheds and pens previously used to house other livestock, such as chickens or pigs. One farmer sought to reduce the costs of recommended feeds by developing his own ration, mixing rice bran, molasses and water. Some farmers established forage plots, but instead of implementing cut-and-carry feeding systems, let their goats graze on them freely, without restricted timing or fencing. This strategy probably reduced the productivity of the forage plot; however, it also reduced the amount of capital and labour requirements. Thus farmers could simultaneously raise their goats alongside other enterprises such as rice planting and harvesting.

Other farmers opted to treat their goats’ disease with traditional, indigenous treatments, also known as ‘ethnoveterinary treatments’ (Koli et al., Citation2023), such as lime juice for the treatment of foot and mouth lesions, when commercial medicine was not available. The use of medicinal plants as low-cost veterinary treatments of livestock disease is widespread in low socio-economic regions of the world where access to veterinary services is limited (Bakare et al., Citation2020; Koli et al., Citation2023; Xiong & Long, Citation2020). Some plants utilised by farmers have been shown to have anti-microbial and anti-inflammatory properties (Koli et al., Citation2023), as was reiterated by farmers in the current study. Treatment of livestock disease with effective ethnoveterinary treatments could potentially reduce the use of antibiotics, thereby reducing the cost for farmers and the risk of antimicrobial resistance emerging (Xiong & Long, Citation2020). Hence, development projects should investigate the efficacy of ethnoveterinary treatments in Laos.

Similar adaptation of recommended practices amongst smallholders has been reported elsewhere. Grünbühel and Williams (Citation2016) found that Eastern Indonesian farmers (n = 296) were limited in their capacity to adopt forage cultivation and cut-and-carry feeding systems due to time, land and labour constraints. As a result, farmers tended to use elements of intervention packages selectively, prioritising activities that increased their cattle’s productivity, whilst minimising risk associated with their rice enterprises (Grünbühel & Williams, Citation2016). Williams et al. (Citation2022) found that farmers in Indonesia (n = 928) had made modifications to recommended practices as a result of the project withdrawing supervision and support. Therefore, exposing smallholders to a range of options gives rise to ideas that can be adapted to socio-cultural contexts and commitments (Williams et al., Citation2022). Development projects should encourage farmers to innovate, adapt, and experiment through trial and error, and self-select particular elements of project interventions where appropriate (Williams et al., Citation2022). This is needed to foster farmer independence; a crucial consideration for project exit strategies.

Our research revealed farmer learning styles that should influence how project learning activities are delivered. Farmers typically valued what they observed over what they were told. This was true for farmer learning in independent, social and project facilitated contexts. Most farmers were influenced to raise goats based on observations of other goat raisers deriving benefits from managing goats in low-input, free-range systems within their community. In addition, most farmers expressed reluctance to seek advice about goat management, sometimes preferring to copy what they observed other goat raisers doing, as opposed to asking them directly. The popularity of trial and error amongst farmers, as an independent learning strategy, demonstrates the preferences to base management decisions on outcomes they can observe, or test for themselves.

Farmers also preferred learning on-the-job from project staff during routine village visits. The informal nature and familiar settings were features that enhanced farmer ability to learn effectively. This enabled farmers to express curiosity around aspects of goat management in casual discussions. Practical training in how farmers could apply disease treatments themselves to goats, increased their participation in learning activities, and could be practiced independently when project staff were not present. In contrast, formal training courses received negative appraisal from farmers as being complex and overly technical. Information could not be retained so fact-sheets and posters should supplement formal courses. Farmer disinterest in non-participatory technical training has been previously reported in Laos. The Asian Development Bank’s Northern Region Sustainable Livelihoods through Livestock Development Project (2007–2014), which targeted five provinces in northern Laos, found that approaches that were considered ‘top-down’, whereby villagers were advised on interventions without decision making or participation, were thought to contribute to farmers reverting back to traditional practices past the project’s close (Asian Development Bank, Citation2015).

Farmer-to-farmer knowledge sharing was another preferred learning method, mentioned by respondents. Development projects can encourage farmer-to-farmer learning as a participatory, demand-driven strategy to increase the reach of extension activities (Boyd & Spencer, Citation2022). Given that farmer-to-farmer learning is driven by farmers within the same local socio-economic and cultural context, the knowledge shared between them is typically more sensitive to farmers’ resource constraints related to implementing recommended practices (Boyd & Spencer, Citation2022). Facilitating farmer-to-farmer knowledge sharing may be cost effective to development projects, as farmers given the task of facilitating learning activities are often motivated by non-monetary incentives, such as skill acquisition (Boyd & Spencer, Citation2022).

Our study revealed that farmers preferred to learn in familiar village settings where they could participate in informal discussions, exchanging their own knowledge and experiences of raising goats. The LS-2017/34 project has implemented farmer cross-visits to facilitate this process. Farmer cross visits involve taking farmers to another village to observe how other farmers are successfully adopting or modifying project interventions to improve their goat’s productivity (Millar & Photakoun, Citation2006). Cross-visits satisfy many of the social learning preferences that were expressed by farmers in this study; they foster discussion and exchange of knowledge and experiences between farmers in informal, familiar village settings (Millar et al., Citation2005). Farmers can observe innovations and adaptations made by other farmers that are likely to be more suitable to their contexts (Millar & Photakoun, Citation2006). To be successful, cross-visits must be organized and run by experienced facilitators and well-trained staff (Millar & Connell, Citation2010). Prior to the cross-visit, clear learning objectives should be established and adhered to, followed by discussion and reflection amongst farmers, which should be mediated by facilitators.

In conclusion, we question the concept of recommended practices for smallholder farmers based on the assumption that smallholder farming systems are sub-optimal. Recommended interventions are assumed to increase the productivity of the target enterprise and benefit farmers. This attitude, whilst well-intentioned, ignores the fine balancing smallholder farmers undertake when devising their management systems. In this research, farmers demonstrated that their goat management systems are a product of their socio-economic and socio-cultural contexts. Farmers developed their goat management systems based on constraints and made compromises to manage multiple enterprises and socio-cultural commitments. Many recommended practices simply ask farmers to devote more resources to the target enterprise. These interventions may leave farmers vulnerable once project support has been withdrawn and often dismisses the valuable and insightful adaptations farmers make when implementing new management strategies. Development projects should therefore question the assumption that recommended practices are inherently optimal, and facilitate farmer learning and goat husbandry improvements according to household aims and constraints.

IJAS Appendix 1 resubmission SS interview.docx

Download MS Word (24.2 KB)Acknowledgments

We thank Moss Vorlachit, Phothong Chanthavilay, Saiya Vongsalath, Vannida Dejvongsa and Vilaysack Thongkhamhan for their translation and transcription services. We thank the National Agriculture and Forestry Research Institute (NAFRI) team for providing information on village demographics, providing transport to target villages, facilitating village interviews and assisting with translation. This work was supported by the University of New England (UNE) and Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR)

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability

The data that supports the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, E. L. The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adeleye, O., Alli-Balogun, J., Afiemo, O., & Bako, S. (2016). Effects of goat production on the livelihood of women in Igabi, Chikun and Kajuru local government areas, Kaduna State, Nigeria. Asian Journal of Agricultural Extension, Economics & Sociology, 11, 1–8.

- Asian Development Bank. (2015). Northern region sustainable livelihoods through livestock development project: Project Completion Report. Metro Manila, Philippines. Retrieved May 06, 2022, from https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/project-documents//35297-013-pcr.pdf.

- Bakare, A. G., Shah, S., Bautista-Jimenez, V., Bhat, J. A., Dayal, S. R., & Madzimure, J. (2020). Potential of ethno-veterinary medicine in animal health care practices in the South Pacific Island countries: A review. Tropical Animal Health and Production, 52(5), 2193–2203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-019-02192-7

- Bardosh, K., Inthavong, P., Xayaheuang, S., & Okello, A. L. (2014). Controlling parasites, understanding practices: The biosocial complexity of a one health intervention for neglected zoonotic helminths in northern Lao PDR. Social Science & Medicine, 120, 215–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.09.030

- Bonnin, C. (2015). Local exchanges and marketplace trade of water Buffalo in upland Vietnam (Lao Cai province). Vietnam Social Sciences, 169, 82–92.

- Boyd, D., & Spencer, R. (2022). Sustainable farmer-to-farmer extension – the experiences of private service providers in Zambia. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 20(4), 438–448. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2021.1939592

- Burns, R. J., Douangngeun, B., Theppangna, W., Khounsy, S., Mukaka, M., Selleck, P. W., Hansson, E., Wegner, M. D., Windsor, P. A., & Blacksell, S. D. (2018). Serosurveillance of coxiellosis (Q-fever) and brucellosis in goats in selected provinces of Lao people’s democratic republic. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 12(4), e0006411. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0006411

- El Hussein, M., Hirst, S., & Salyers, V. (2014). Using grounded theory as a method of inquiry: Advantages and disadvantages. The Qualitative Report, 19, 1–15.

- Gill, S., Sharma, N., Kumar, D., & Kumar, D. (2022). Identify the constraints faced by goat keepers in the Pratapgarh district of Rajasthan. The Pharma Innovation Journal, 2, 1105–1107.

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1999). Discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. (Routledge.

- Glover, D., Sumberg, J., & Andersson, J. A. (2016). The adoption problem; or why we still understand so little about technological change in African agriculture. Outlook on Agriculture, 45(1), 3–6. https://doi.org/10.5367/oa.2016.0235

- Gray, D., Walkden-Brown, S., Phengsavanh, P., Patrick, I., Hergenhan, R., Hoang, N., Phengvilaysouk, A., Carnegie, M., Millar, J., & Hữu Văn, N. (2019). Assessing goat production and marketing systems in Laos and market linkages into Vietnam. Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research. Retrieved March 06, 2022, from https://www.aciar.gov.au/publication/technical-publications/assessing-goat-production-and-marketing-systems-lao-pdr-and-market-linkages-vietnam.

- Grünbühel, C. M., & Williams, L. J. (2016). Risks, resources and reason: Understanding smallholder decisions around farming system interventions in Eastern Indonesia. Journal of Agriculture and Rural Development in the Tropics and Subtropics, 117, 295–308.

- Hunter, C. L., Millar, J., & Lml Toribio, J.-A. (2022). More than meat: The role of pigs in Timorese culture and the household economy. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 20(2), 184–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2021.1923285

- Jansen, C., & van den Burg, K. (2004). Goat keeping in the tropics. Wageningen.

- Karnowski, V., von Pape, T., & Wirth, W. (2011). Overcoming the binary logic of adoption. On the integration of diffusion of innovations theory and the concept of appropriation. In A. Vishnawath & G. Barnett (Eds.), The diffusion of innovations. A communication science perspective (pp. 57–75). Peter Lang.

- Kelle, U. (2007). The development of categories: Different approaches in grounded theory. In A. Bryant & K. Charmaz (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of grounded theory (pp. 191–213). Sage Publications Ltd.

- Keonakhone, T., Chiathong, V., Badenoch, N., Phonnachit, P., & Chanthavong, N. (2009). Livestock Groups: Lessons from Phonethong, Phonexay district, Luang Prabang province. National Agriculture and Forestry Research Institute. Retrieved November 11, 2022, from http://lad.nafri.org.la/show_record.php?mfn=2660.

- Koli, S., Dewangan, G., & Sahoo, D. (2023). Management of goat diseases using ethnoveterinary practices. Indian Journal of Livestock and Veterinary Research, 3, 126–135.

- Le, S. V., de las Heras-Saldana, S., Alexandri, P., Olmo, L., Walkden-Brown, S. W., & van der Werf, J. H. J. (2024). Genetic diversity, population structure and origin of the native goats in Central Laos. Journal of Animal Breeding and Genetics. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbg.12862

- MAF. (2014). Lao Census of Agriculture 2010/11 Analysis of Selected Themes. Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, Vientiane, Lao PDR. Retrieved December 14, 2022, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340332818_LAO_CENSUS_OF_AGRICULTURE_201011_ANALYSIS_OF_SELECTED_THEMES.

- Millar, J. (2021). Social and cultural implications of scaling out livestock production in the Lao PDR.

- Millar, J., Colvin, A. F., Phengvilaysouk, A., Phengsavanh, P., Olmo, L., & Walkden-Brown, S. (2022). Smallholder goat raising in Lao PDR: Is there potential to improve management and productivity? The Lao Journal of Agriculture and Forestry, 46, 20–34.

- Millar, J., & Connell, J. (2010). Strategies for scaling out impacts from agricultural systems change: The case of forages and livestock production in Laos. Agriculture and Human Values, 27(2), 213–225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-009-9194-9

- Millar, J., & Photakoun, V. (2006, 3–6 March). Pathways to improving livelihoods in the uplands of Laos: Researching and improving extension practice. APEN international conference, Beechworth, Victoria.

- Millar, J., & Photakoun, V. (2008). Livestock development and poverty alleviation: Revolution or evolution for upland livelihoods in Lao PDR? International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 6(1), 89–102. https://doi.org/10.3763/ijas.2007.0335

- Millar, J., Photakoun, V., & Connell, J. (2005, 26 June–2 July). Accelerating the impacts of participatory research and extension: Lesson from Laos. Meeting of the international grassland congress (IGC), Dublin, Ireland.

- Mohan, B., Sagar, R., & Singh, K. (2016). Factors related to promotion of scientific goat farming. Indian Research Journal of Extension Education, 9, 47–50.

- Morales, L. E., Hoang, N., Van, H. N., Ba, X. N., Nga, T. B., Cuc, T. K. N., Nguyen, D. V., Phengvilaysouk, A., Olmo, L., & Walkden-Brown, S. (2023, 7–10 February). Mountain goat value chain in Laos and Vietnam: Constraints and development opportunities. Australian agricultural & resource economics society (AARES) 67th annual conference, Christchurch, New Zealand.

- Olmo, L., Phengvilaysouk, A., Colvin, A. F., Phengsavanh, P., Millar, J., & Walkden-Brown, S. (2022, 5–7 July). Improving Lao goat production when resources are limited. Australian association of animal sciences conference, Cairns, Australia.

- Oluka, J., Owoyesigire, B., Esenu, B., & Sssewannyana, E. (2005). Small stock and women in livestock production in the teso farming system region of Uganda. Small Stock in Development, 151, 151–160.

- Ørskov, E. R. (2011). Goat production on a global basis. Small Ruminant Research, 98(1-3), 9–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smallrumres.2011.03.009

- Peacock, C. (2005, 31 October–4 November). Goats: Unlocking their potential for Africa’s farmers. Proceedings of the seventh conference of ministers responsible for animal resources, Kigali, Rwanda.

- Phengsavanh, P. (2006, 24–25 October). Goat production in Lao PDR. Potential, limitations and approaches of forage development, goats: Undervalued assets in Asia. Proceedings of the APHCA-ILRI regional workshop on goat production systems and markets, Luang Prabang, Lao PDR.

- Phengvichith, V., & Preston, T. (2011). Effect of feeding processed cassava foliage on growth performance and nematode parasite infestation of local goats in Laos. Livestock Research for Rural Development, 23, 1–8.

- Phengvilaysouk, A., Colvin, A., Olmo, L., Phengsavanh, P., Millar, J., & Walkden-Brown, S. (2022). Smallholder goat herd production characteristics and constraints in Lao PDR. The Lao Journal of Agriculture and Forestry, 46, 3–19.

- Sabapara, G., Sorthiya, L., & Kharadi, V. (2014). Constraints in goat husbandry practices by goat owners in Navsari district of Gujarat. International Journal of Agricultural Sciences & Veterinary Medicine, 2, 31–36.

- Saunders, B., Sim, J., Kingstone, T., Baker, S., Waterfield, J., Bartlam, B., Burroughs, H., & Jinks, C. (2018). Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality & Quantity, 52(4), 1893–1907. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8

- Tefera, T. M. (2007). Improving women farmers’ welfare through a goat credit project and its implications for promoting food security and rural livelihoods. Journal of Rural and Community Development, 2, 123–129.

- The World Bank. (2020). ‘Rural population (% of total population) - Lao PDR.’ Retrieved June 07, 2022, from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.RUR.TOTL.ZS?locations=LA.

- The World Bank. (2022). Lao Rural Livelihoods in Times of Crisis. Retrieved June 07, 2022, from https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/0540059f3dbe2a7bac78b780c428eba4-0070062022/related/LaoPDRCommunitySurveyReportMay-Nov22Final.pdf.

- Torres-Hernández, G., Maldonado-Jáquez, J. A., Granados-Rivera, L. D., Wurzinger, M., & Cruz-Tamayo, A. A. (2022). Creole goats in Latin America and the Caribbean: A priceless resource to ensure the well-being of rural communities. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 20(4), 368–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2021.1933361

- Utaaker, K. S., Chaudhary, S., Kifleyohannes, T., & Robertson, L. J. (2021). Global goat! Is the expanding goat population an important reservoir of cryptosporidium? Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 8, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2021.648500

- van Veggel, N. (2021). Using Grounded Theory to Investigate Evidence Use by Course Leaders in Small-Specialist UK HEIs.

- Williams, L. J., van Wensveen, M., Grünbühel, C. M., & Puspadi, K. (2022). Adoption as adaptation: Household decision making and changing rural livelihoods in Lombok, Indonesia. Journal of Rural Studies, 89, 328–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.12.006

- Windsor, P. A., Nampanya, S., Putthana, V., Keonam, K., Johnson, K., Bush, R. D., & Khounsy, S. (2018). The endoparasitism challenge in developing countries as goat raising develops from smallholder to commercial production systems: A study from Laos. Veterinary Parasitology, 251, 95–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2017.12.025

- Windsor, P. A., Nampanya, S., Tagger, A., Keonam, K., Gerasimova, M., Putthana, V., Bush, R. D., & Khounsy, S. (2017). Is orf infection a risk to expanding goat production in developing countries? A study from Lao PDR. Small Ruminant Research, 154, 123–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smallrumres.2017.08.003

- Xaypha, S. (2005). Goat production in small holder farming systems in low lands Lao PDR and an evaluation of different forages for growing goats. MS thesis. Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences.

- Xiong, Y., & Long, C. (2020). An ethnoveterinary study on medicinal plants used by the Buyi people in Southwest Guizhou, China. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 16(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-020-00396-y

- Zaibet, L., Dharmapala, P. S., Boughanmi, H., Mahgoub, O., & Al-Marshudi, A. (2004). Social changes, economic performance and development: The case of goat production in Oman. Small Ruminant Research, 54(1–2), 131–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smallrumres.2003.11.002

- Zereu, G., & Lijalem, T. (2016). Status of improved forage production, utilization and constraints for adoption in Wolaita Zone, Southern Ethiopia. Livestock Research for Rural Development, 28, 1–10.