ABSTRACT

This article explores the (un)translatability of ṭarab—typically understood as feeling ecstasy in response to poetic and musical performances—in the recitation of Arabic poems and their translation in a US context. I compare Dunya Mikhail’s Arabic and English performances of selected poems from al-Ḥarbu taʿmalū bi-jidd [The War Works Hard, 2000; 2005] with an English performance by the translator, Elizabeth Winslow. Through this comparison, I theorize ṭarab as an affective force that transcends language in general and Arab(ic/ness) more specifically. Drawing on Jonathan Shannon’s affirmation of the multiplicities of ṭarab contexts, I argue that ṭarab is evoked in distinctly diverse iterations in the performances of the poet and the translator as well as in the poet’s different voicings of the poem, in written and oral forms. This theorization of ṭarab expands the term’s application beyond its limited association with Arabic poetry and music to a broader aesthetics of wajd and orature.

One of my most memorable classes during my coursework years was a session on Arabic poetics in a seminar on Comparative Arab/ic literature and criticism. The discussion started with a showing of a recorded poetry performance by Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish on YouTube. To be honest, I do not remember what video we watched, nor do I remember the exact poem we listened to. This session’s affective and intellectual potency emanated most clearly from the reaction I witnessed two non-Arabic-speaking classmates having to the performance. Beside the three graduate students with native Arabic proficiency taking that seminar, three other students were beginner-level learners of Arabic and two had no knowledge of Arabic whatsoever. Of the two classmates I am referring to above, one belonged to the former category and the other to the latter. While a fellow native Arabic speaker and I were tearing up, the student with no Arabic proficiency said they got goosebumps from the performance and the other noted: “the hairs on my arms are standing.”

Like others, I’ve always been moved when hearing Darwish recite his poetry. Yet, this particular instance made me realize that what moved me and others was not just his words and the powerful sentiments they evoke. Darwish’s voice has a particular effect, a simultaneously poetic and aural force of which the word ṭarab provides the most apt description. The meaning of his words may have contributed to the impact his voice had on me, but when linguistic comprehension is removed from this context, affective experience of ṭarab is still possible. To put this another way, understanding the meaning of the poem is not the only cause for moving the students in the classroom. I would also argue that Arabic language per se may not be the source of these affective responses. Could another poetic performance that shared similar sonic, vocal and rhythmic patterns have the same impact? I do not think so. But it was not the language that gave rise to that affective experience of ṭarab. It is the affective intensity with which the poet performed the poem, an intensity that was carried over to how the sounds reverberated and how the words acquired meaning—for those who could perceive that meaning. Ṭarab has often been defined as the affective impact of musical and poetic performances on their performers and their audiences. It is also described as an ecstatic or an emotional state that transports those affected by it to a realm beyond space and time. Its temporal fluidity arises from the way it employs the affective potential of the aural event to condense past, present, and future thoughts and emotions into the enclosed performance space. Engaging with ṭarab in more depth and detail below, this article expands the standard conceptualizations of ṭarab by unpacking what I perceive to be the paralingual experience of ṭarab. I examine the affective vocalizations and translations of ṭarab of one of the key participants in the ṭarab experience—the performer—and compare the performances of the same poem by the poet and the translator to an anglophone audience. This comparative study proposes that a performer’s voice becomes the transducer of ṭarab in the performance setting, whereby each performance occasion gives rise to the transduction of different affective ṭarab experiences.

Transduction is a key term in sound studies denoting the transformation of sound into energy and its movement from one place to another. Julian Henriques explains that sound is not just a medium but also a material thing that affects physical and social fields; “transduction describes a process of transcending the dualities of form/content, pattern/substance, body/mind, and matter/spirit. A transducer is a device for achieving escape velocity to leave the world of either/or and enter the world of either or both.”Footnote1 Similarly, Nina Sun Eidsheim argues for a broader application of transduction in an approach that moves beyond the metaphorical and stresses the diverse materialities involved in different acts of voicings and listening. She notes,

human entities constitute only one of the many materialities through which energy is transmitted and transduced. It is the full spectrum of transmission and transduction of sound vibration that is taken into account in explicit studies of the impact of vibration in positive (therapy) and negative (regulations regarding health hazards) terms.Footnote2

Drawing on these theories of the voice and transduction, I contend that ṭarab is a form of affective experience that manifests itself in multiple forms, only one of which is through vocal vibrations. Ṭarab could therefore—as has commonly been understood—be compounded through affective interaction in the performance space, which is what Ali J. Racy describes as an ecstatic feedback model between the performer and her audience.Footnote4 But I also examine ṭarab as an affective force that precedes semantic content and transcends its Arab(ic) cultural origins, by analyzing its transmission and transduction through voice, not language. I situate the affective experience of ṭarab in feelings and imaginations that are enlivened by impactful situations of poetic composition, performance, acts of listening, and other sensorial forms of witnessing. The intensification of the affective experience through affect contagion within performance spaces is what has generally been understood as ṭarab because it showcases the highest level of this kind of affectation. Silvan Tomkins defines this as “the principle of contagion,” referring to how most affects are “specific activators of themselves.”Footnote5 Teresa Brennan also claims affects are transmittable in a somewhat unidirectional way.Footnote6 Anthropological and ethnographic studies of ṭarab, however, show its affect contagion within the performance space to be more fluid and dynamic among performers and listeners than moving from the performer to the audience.

These complexities of ṭarab and its potential for affect contagion within and beyond the performance space warrant further exploration. Therefore, coming across a performance of Dunya Mikhail’s “al-Ḥarbu taʿmalu bi-jidd”Footnote7 and its translation as well as a performance of the same poem by the translator, Elizabeth Winslow, prompted me to take this up. Iraqi American poet Dunya Mikhail (b. 1965) has been invited several times to perform her work in US settings, some of which were made available online. Her works are the first by a contemporary Iraqi woman poet to be translated into English, and among them is al-Ḥarbu taʿmalu bi-jidd (The War Works Hard, 2000 ; 2005).Footnote8 And when Elizabeth Winslow's translation of this poetry collection was shortlisted for the Griffin Poetry Prize in 2009, Winslow was recorded performing the title poem in her own voice and the recording was uploaded to YouTube. The digital availability of both these texts exhorts an examination of the (un)translatability of the affective experiences of ṭarab to an anglophone audience. By analyzing different contexts of ṭarab in Mikhail’s act of poetic composition, performances, and Winslow’s performance of Mikhail’s translated poem, I argue that ṭarab is a paralingual cross-cultural affective force that arouses a person to act or react in response to their affective state. Ṭarab is also multiple and diverse, and each affective experience of ṭarab is distinct. In one of its forms, ṭarab precedes language and becomes the affective force giving the poem its vocal resonance in written or oral form. Accordingly, ṭarab may be solitary or participatory, which expands its standard theorization as a primarily social experience. Ultimately, I contend that bodies are animated by their affective experiences of ṭarab, prodding them to write poetry, perform it, (re)act in certain ways and—in the process—render the translatability of their ṭarab at least partially possible.

***

In an interview with Sobia Khan, Mikhail affirms that feelings give rise to her writing process. Mikhail explains,

[m]y mother … used to mention to our guests that I was busy writing “feelings” as an excuse for me being in my room and not with them … she called the poems “feelings” because in Arabic the two words are close: we call poetry shiʿr and feeling shiʿur [sic], and she made her own plural of “feelings” for “poems.”Footnote9

Kitāb al-Aghānī (The Book of Songs) by Abū al-Faraj al-Iṣfahānī (897–967) is the first in-depth exploration of ṭarab in context. Throughout the book, al-Iṣfahānī interweaves a thoroughly researched cultural anthropology of the historical and social performance practices of musicians, poets and their audiences in those eras. Al-Iṣfahānī’s anthropological presentation of ṭarab does not necessarily offer a clear definition of the term, but he extends a notion of ṭarab as a physically discernible emotional response to the music and poetry whether through the act of recitation or listening. His descriptions of the responses to music or poetry vary throughout the book’s 25 volumes. It would be difficult to enumerate them all, but they include: tapping one’s feet out of joy, wanting to jump out of one’s skin, unconsciously breaking into dance, aching the heart and bringing tears to one’s eyes, feeling relief that was discerned by everyone around, feeling like one’s about to fly, and ripping one’s clothes and jumping into a pool of wine, etc.Footnote10

Al-Iṣfahānī’s notion of ṭarab is explored in more depth as an entry in George Dimitri Sawa’s An Arabic Musical and Socio-Cultural Glossary of Kitāb al-Aghānī (2015). Sawa quotes Ibn Khurdādhibah’s identification of three types of ṭarab: one pleases and revitalizes the soul, prodding it to do good, another pains the spirit as a result of an expression of loss, and the last purifies the soul and soothes the senses because of the dexterity of composition.Footnote11 Ibn Khurdādhibah’s analysis of the concept echoes al-Iṣfahānī’s ethnographic observations in al-Aghānī. The affective impact of ṭarab is not reducible to the joyful connotations of English terms such as ecstasy and elation. This is perhaps why it is so difficult to translate. It is an emotional and affective response, whether externalized or not by the body, but the emotion(s) that ṭarab makes possible are themselves unlimited. In fact, Sawa notes that the most beautiful and comprehensive definition of ṭarab is provided by Ibn al-Ṭaḥḥān. An eleventh-century musicologist, Ibn al-Ṭaḥḥān is one of the earliest and most noteworthy theoreticians of Arab music. In his book, Ḥāwī al-funūn wa salwat al-maḥzūn (The Art Keeper and the Peace of Mourners), he defines ṭarab as “what provokes the person in the form of joy or sadness, which is not exclusively caused by singing or other forms of entertainment.”Footnote12 This definition reiterates some of the responses noted by al-Iṣfahānī, when Abū al-ʿAtāhiyah tells Hārūn Ibn Makhāriq:

يا بني، حدّثني؛ فإنّ ألفاظك تُطرب كما يُطرب غناؤك .

Dear boy, talk to me, for your speech brings forth as much ṭarab as your singing.Footnote13

Mikhail’s and her mother’s description of her shiʿr (poetry) as shuʿūr or feelings is therefore an extension of classical understandings of ṭarab, as theorized by Ibn Khurdādhibah and Ibn al-Ṭaḥḥān. The verb shaʿara itself could either mean to feel, to perceive or to notice, or to versify, which recalls Ibn al-Ṭaḥḥān’s assertion that the affective force of ṭarab could be the result of different forms of affective provocations such as “poetry, conversation, generosity of spirit, good behaviors, beautiful scenes … which may be equally fitting in moments of fear, remembrance of death, misfortune, expression of condolences, separation, affiliating with the virtuous , and meeting loved ones.”Footnote14 I posit that during poetic composition, both senses of the word coincide; the poet perceives, feels, and versifies, so her affective experiences and memories of pain, suffering and misfortune inhabit the sound of the poem in her mind through ṭarab as an affective force. In other words, ṭarab is an affective force that gives rise to the poem as sound on the paper and eventually in performance. It is an affect that precedes the poem’s composition and, by extension, its semantic content.

This claim does not undercut the social aspect of ṭarab’s affective experience that most contemporary theorists stress. It, rather, aims to expand it beyond interpersonal sociality by exploring its intrapersonal affective potential. Ali J. Racy is right to affirm that “ṭarab tends to occur in relatively distinct social venues, in specialized contexts that are separate from the flow of ordinary daily life.”Footnote15 Michael A. Figueroa also introduces post-tarab as a “distinctly postmigrant [SWANA] aesthetic” that is primarily participatory.Footnote16 On the other hand, Jonathan H. Shannon stresses a communal requirement for the evocation of ṭarab:

The internal state of the vocalist … seems to be an effect of his or her relationship with the audience and not the cause of it … This relationship at once reflects and produces the musical, social, and emotional states that allow artists and audiences to experience the feelings they gloss as “tarab” [sic].Footnote17

The animation of ṭarab in orature

As an affective force that precedes the poem, ṭarab is therefore not necessarily determined by the poet’s (Arabic) language or poetic and musical legacy. Ṭarab, a non-referential but material and telling (e)motional affect, resonates in her mind so hard that her poems are echoed on the poetic page. Mikhail’s “Ṣāniʿ aḥdhiya [A shoemaker]” illustrates the nuanced influence of sound and aurality in her poetry. At first glance, the poem’s intensive use of anaphora through the repetition of “al-aqdām al-latī … [feet that …]” may seem like the poem’s main source of orality. The aural qualities that give shape to the poem, however, are much more subtle than that. The poem starts with an identification of the main character, the shoemaker hard at work all his life, then switches to the customers he makes shoes for. These customers, however, are reduced to treading feet.

The synecdoche establishes a clear contrast between the shoemaker, an anonymous yet fully corporeal presence, and his faceless customers. The hand of the skilled shoemaker does not stand in for his body like his customers’ feet. His distinctiveness is reinforced by the audible echoes of his actions. The shoemaker “yaduqqu al-masāmīr/ yusawwī al-julūd [pounded nails and smoothed the leather.]” Beside the onomatopoeic effect of his daqq (pounding), his two main actions in the poem are intensified through the shadda ( ــّـ ). Shadda is an Arabic diacritic denoting gemination, which is a doubling of the consonant that intensifies its sound and increases its duration. This doubling is the result of the repetition of the same letter, without a following vowel in its first iteration (that is, has sukūn which is a diacritic symbol indicating a syllabic end), and followed by a short vowel in the second one. The gemination of the shoemaker’s actions is rendered particularly powerful because of the specific consonants they double, the first being the qāf and the second being the wāw. This power emanates from their characteristics as Arabic phonemes. When the qāf is sākina [i.e. has sukūn], its articulation requires more force that leads to an echoing or bouncing sound.Footnote24 The qāf’s gemination thus almost triples the intensity of the sound and its associated action, the shoemaker’s daqq. Additionally, the gemination of wāw, a glide consonant, elongates the duration of the action because of its phonetic similarity to the vowel /ū/. Consequently, the sonic intensification and elongation of the shoemaker’s actions resound his enduring labor and the hard life he has had. As an Arabic diacritic with specific phonetic effects, the shadda recalls the resonant word shidda (hardship) with which it shares a root. This implied consonance further amplifies the hardship the action semantically and phonetically evoke.

On the other hand, the faceless feet mostly perform actions of simpler phonetic structures. Most of these actions are of the first triliteral measure /faʿala/, such as “tarkul [kick] … taghūṣ [plunge] … tarkuḍ [run] … taqfiz [jump] … ” And when their actions are phonetically complicated such as “tughādir [flee] … tatahāwā [collapse] … tartajif [tremble],” they are of measures indicating reciprocal or reflexive simple actions, unlike the shoemaker’s action “yusawwī [smoothed]” which is a second measure causative intensive action, /faʿʿal/. And when an intensive causative is associated with one of the feet, it is negated, “lā tataḥarrak [do not move].” This semantic, syntactic, and ensuing phonetic divergence of the shoemaker from the rest of the feet situates him on a different plane for Mikhail. He is the one forgotten in this narrative of war. He creates the shoes for the feet that trample and those trampled upon, of which he is most likely the latter. In many ways, he brings commonality and unity to the warring factions in this war that works so darn hard. The shoemaker works just as hard if not more, but his customers take his work to the ground. His skills are wasted on these doomed feet, and yet he works “ṭawāl ʿumrihi [all his life]” so that those feet can walk through “life … [which becomes] a handful of nails/ in the hand of a shoemaker.” Unfortunately, though, these feet put on his shoes and walk to their deaths. Mikhail’s imagined life of this anonymous shoemaker saturates the poem’s sound. Clearly, beyond the ostentatious orality of the poem’s anaphoric repetitions, “ṣāniʿ ‘aḥdhiyya” illustrates that the form of the poem is the affective aural force brought forth from Mikhail’s affective experiences and memories. Poetic imagination moves her to composition, and it is this (e)motion that gives aural shape and form to her poetry on the page.

Mikhail’s poetics enacts orature, an “oral system of aesthetics” that has its roots in all cultures of the world as explained by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o.Footnote25 Adélékè Adéẹ̀kọ́ elucidates the concept of orature further: it is “the creative and imaginative art of composition that relies on verbal art for communication and that culminates in performance.”Footnote26 Orature attempts to shed the colonial baggage of the notion of “oral literature” and undo the binary of written and oral:

The real binary was ‘orate’ and ‘literate’ and they were not oppositional absolutes; they were connected by the word; they had their adequacies and inadequacies as representations of thought and experience. Writing and orality were natural allies, not antagonists; so also orature and literature.Footnote27

her onion structure theory … begins with a nucleus, or inner core, at the center of its being. “The shape of this nucleus/core is round or circular. This is then surrounded by accumulating layers . . . layers upon layers of increasing solidity. The layers also become larger and larger, or wider and wider in their ‘circularness’ as we move outwards—away from the core nucleus. These embracing and connecting circles or rings maintain tight contact with each other, harmoniously making one whole.” Orature reflects a reality of connected circles from the inner being of the individual and social person to the outmost circle of “the sun, the moon, the stars, the sky and the rest of the elements.”Footnote28

Mũgo’s powerful metaphor of orature draws attention to the role of the senses as the translucent scales binding the individual to thicker and larger layers of the world. With the artist filling in for the nuclear individual in this metaphor, she connects to the world through her sensory experiences. The tight interlinkages produced in this process ensue from the sensory modes of knowing and experiencing the world. Orality is only one of those sensory modes that always works in fusion with other modes. The poet’s sensations give shape to her connection with the world through her poetry. Dunya Mikhail’s poetry becomes a performative act of interconnectedness and communication, even if some of the affective forces giving rise to it are obfuscated:

orature realizes its fullness in performance. There’s no metaphysics of absence in performance, only that of presence, except of course when the performance … is recorded in audio, written, and other visual forms. In such a case … the written makes possible the continued resurrection of absence into a presence.Footnote29

Therefore, despite the solitary nature of poetic composition, communication and performance remain essential to the affective force of ṭarab. As Nina Sun Eidsheim shows, the voice is an unfolding event not an object. It is much more complicated than mere sounds: “at the moment when you hear a sound, the forces that initiate it, shape it and propel it into existence have already carried out their work.”Footnote30 Sounds are therefore not necessarily the source of ṭarab but could very well be its result, when viewed as a more complex thick event. As an embodied vibrational practice, the voice, Eidsheim further affirms, “is not necessarily sound, not all sound is related to a causal event.”Footnote31 Informed by Eidsheim’s theorization of sound as an unfolding thick event, I am suggesting that the poet’s body becomes, as a result of the affective force of ṭarab, the material through which oral composition transforms into an aural event for its readers through both its poetic composition and solitary oral performance. Poetic composition requires the animation of the poet’s feelings and sensations (i.e. her affective experience of ṭarab) in the written performance of the poem, and the aurality of Mikhail’s poem is eventually animated by the act of reading as a sonic event that intimates mediated affective experiences, commingling with those of their readers.

Ṭarab as a form of wajd and the transduction of sound knowledge

Ali J. Racy’s ecstatic feedback model of ṭarab is more relevant when Dunya Mikhail’s poetry is performed in oral rather than written form. The animation of the poem as a sonic event becomes collaborative in the performance space. As the context changes from composition to performance and the occasion for performance itself changes from one event to another, the affective force of ṭarab that gives oral form to the poem’s performance changes. Yet, the change in the unfolding sonic event means that the whole performance space becomes the echo chamber through which affects circulate and animate the bodies inhabiting it, including the poet and the audience members. Many scholars have already analyzed audiences’ contributions to the continuous affective transmutations within the performance space.Footnote32 Building on these theories, I direct my attention here to the poet’s oral animation of her own poem as a sonic event, as it differs from that of the solidary reader.

Dunya Mikhail was invited to read her poetry in the regular lunch poem series organized by UC Berkeley and introduced by Professor Robert Hass, the founder of the series, on 1 February 2007.Footnote33 At the podium, Mikhail apologizes for her accented English before beginning her readings: “I hope you will not be really distracted by my heavy accent. As Robert said this is my third language I’m reading in, so please be patient with me.” She follows that with a reading in English of “A Second Life.” Her accent is particularly recognizable in the rhythm of her English recitation, which mimics Arabic language prosody.Footnote34 The fusion of familiar English words with unfamiliar rhythm may cause some discomfort for her audience, which is why she apologizes in advance. Interestingly enough, though, she uses this opportunity to push the audience to the limits of their recognizable soundscape, when she abruptly shifts to the Arabic opening of “al-ḥarbu taʿmalu bi-jidd [The War Works Hard]” before moving to a reading of its translation.Footnote35 When the poet ends “A Second Life” with “we need a second life to learn how to live without pain,” she immediately shoves the audience into the affective pain of incomprehension. In doing so, she triggers the anglophone audience’s discomfort while simultaneously urging them to imagine a second life whereby they do not have to experience that kind of pain. The life this urge generates is one where she is not an ostensibly racialized other whose difference causes discomfort. It is one where they neither know her language nor are at least accustomed to her aural difference. It is one where the audience is comfortable with the discomfort. But most of all, it is one where they learn to listen as well as tune in to what they need to listen for.

Mikhail’s use of Arabic, which is incomprehensible to most of her anglophone audience, thus promotes what Kapchan calls “literacies of listening” or sound knowledge. She defines this form of literacy as “the acquired ability to learn other cultures … through participating in their sound worlds.”Footnote36 Kapchan’s literacies of listening are not necessarily literacies in the standard sense of the word. This kind of literacy enables the audience to experience the “performative power of listening: 1) in its role as witness to the pain and praise of others, 2) as a political tactic, and 3) as a method of sound knowledge transmission that often involves lingering in the space of discomfort.”Footnote37 This discomfort paradoxically ensues from incomprehension. The theoretical amalgamation of affective listening and incomprehension was addressed by eleventh-century Muslim philosopher Abū Ḥāmid al-Ghazālī in Iḥyā’ ʿūlūm al-dīn (The Revival of Religious Sciences). Rather than using ṭarab, al-Ghazālī employed wajd in “Ādāb al-Samāʿ wal-Wajd (The Etiquettes of Listening and Ecstasy)” in the second volume of his book, “Rubʿ al-ʿĀdāt (The Book of Customs)” to describe “mā yūjad bil-samāʿ (what is found upon listening)” or the affective response to sounds.Footnote38 He further defines wajd itself as

الوجد مكاشفات من الحق … إنه عبارة عن حالة يثمرها السماع وهو وارد حق جديد عقيب السماع يجده المستمع من نفسه . وتلك الحالة لا تخلو عن قسمين : فإنها إما أن ترجع إلى مكاشفات ومشاهدات هي من قبيل العلوم والتنبيهات، وإما أن ترجع إلى تغيرات وأحوال ليست من العلوم بل هي كالشوق والخوف والحزن والقلق والسرور والأسف والندم والبسط والقبض، وهذه الأحوال يهيجها السماع ويقويها.Footnote39

revelations of truth … a state brought about by listening or a new truth succeeding the act listening that is discovered by the listener herself. This state is the result of one of two causes: it either proceeds from observations and discoveries of a scientific nature, or it arises from non-scientific changes and states such as longing, fear, sorrow, anxiety, happiness, grief, magnanimity, frugality, etc. and these states are exacerbated and intensified by acts of listening.Footnote40

Yet, this knowledge or the truths of the second kind in particular do not necessarily stem from comprehension. In fact, al-Ghazālī’s description of the affective responses to listening relies entirely on incomprehension:

إنه محرك للقلب ومهيج لما هو الغالب عليه … فمن الأصوات ما يفرح، ومنها ما يحزن، ومنها ما ينوم، ومنها ما يضحك ويطرب، ومنها ما يستخرج من الأعضاء حركات على وزنها باليد والرجل والرأس . ولا ينبغي أن يظن أنّ ذلك لفهم معاني الشعر، بل في الأوتار حتى قيل من لم يحركه الربيع وأزهاره والعود وأوتاره فهو فاسد المزاج ليس له علاج . وكيف يكون ذلك لفهم المعنى وتأثيره مشاهد في الصبي في مهده؟ فإنه يسكنه الصوت الطيب عن بكائه وتنصرف نفسه عما يبكيه إلى الإصغاء إليه . والجمل مع بلادة طبعه يتأثر بالحداء تأثرًا يستخف معه الأحمال الثقيلة. ويستقصر لقوّة نشاطه في سماعه المسافات الطويلة، وينبعث فيه من النشاط ما يسكره ويولهه، فتراها إذا طالت عليها البوادي واعتراها الإعياء والكلال تحت المحامل والأحمال إذا سمعت منادي الحداء تمد أعناقها وتصغي إلى الحادي ناصية آذانها وتسرع في سيرها حتى تتزعزع عليها أحمالها ومحاملها، وربما تتلف أنفسها من شدّة السير وثقل الحمل وهي لا تشعر به لنشاطها. Footnote41

Listening moves the heart and arouses what has already overtaken it. Some sounds make you rejoice, some make you grieve, some make you sleep, some make you laugh or feel jubilant, and others elicit movements to the rhythm from your hands, feet, and head. And this should not be presumed to be the result of understanding the meaning of a poem, but that of the instruments themselves. It is even said that those are not moved by spring and its flowers, or the oud and its strings are of an uncurable foul mood. For how could this be the impact of understanding when this works on a baby in her cradle? A beautiful voice calms her down and draws away her attention from what brought about her tears. Similarly, despite its sluggish nature, camels are moved by the cameleer’s song in a way that renders heavy loads light. Upon hearing the cameleer’s song, a camel gets so intoxicated and distracted that a long journey begins to seem short. So, even when camels are worn out and exhausted from heavy loads and long trips, the minute they hear their cameleer’s song, the camels extend their necks, perk up their ears to listen to the cameleer, and hasten their pace so much that their loads begin to shake on their backs and, in their abrupt animation, may actually harm themselves from the briskness of their pace and the heavy weight of their loads.

The incomprehensibility of the Arabic reading, especially when preceding the reading of the English translation, engenders a non-referential listening. For instance, when she performs “ṣāniʿu aḥdhiyya [shoemaker],” the audience is bombarded with a series of those difficult emphatic Arabic consonants like the ṣād and the qāf as well as inscrutable and seemingly homonymous fricatives such as the ḥā’, khā’, and ʿayn when she begins: “ṣāniʿū ‘aḥdhiyyatin māhir// ṭawāl ʿumrihi/ yaduqqu al-masāmīr/ yusawwī al-julūd li-mukhtalaf al-aqdām/ aqdāmun tughādir/aqdāmun tarkuḍ … ”Footnote42 The oral performance of the phonetic contrast between the shoemaker’s soundworld and the faceless feet is laid bare in front of them but remains semantically inaccessible. What they hear is the affective force that gives shape to the poet’s articulations and their sonic resonances. The distinctive sonic hardship and the duration of the labor invoked into the shoemaker are also coupled with the endless repetition of the long vowel /ā/ evoking the ah-ing anguish she articulates all throughout the poem, as she mourns the reality of the shoemaker’s work and his customers’ inevitable fate.

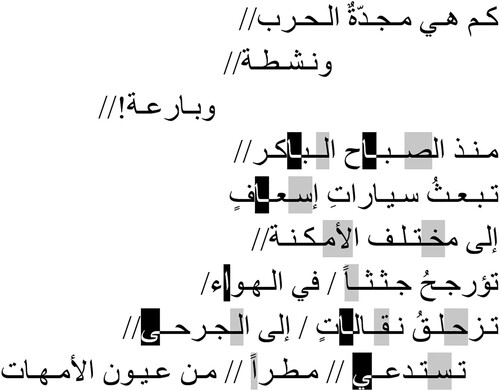

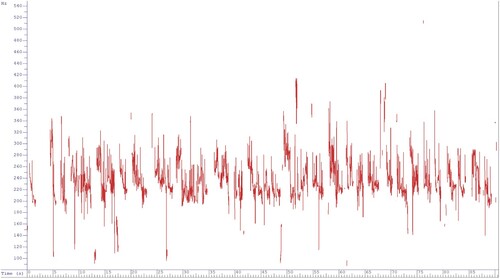

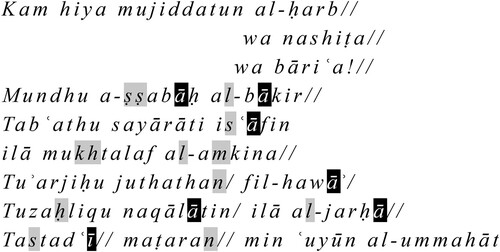

This anguish is reflected in the rest of her ِ Arabic performances through her sonic deceleration of time. By simultaneously playing on the natural features of some Arabic sounds and rhythmically pacing her reading of the poems, Mikhail prolongs the affective experience of sounds. When she reads the opening of “al-ḥarbu taʿmalu bi-jidd,” she relies on inherently long Arabic vowels and consonants and complements them with other sonically artificial elongations. This is evident in my analysis of the performed Arabic poem in and , where Iuse black highlights to indicate an elongated long vowel and grey highlights to indicate an elongated consonant. Furthermore, I employ (/) to signal a short pause and a (//) to signal a long pause in this specific performance occasion. In this opening verse, Mikhail makes use of frequent pauses, and many of the long vowels such as /ā/ and /ī/ are lengthened to double their time. Moreover, when some of the consonants have sukūn ( ـْ ), their vocalization lasts longer; the phonetic continuants (such as the /s/, the /ḥ/ and the /m/) are easily elongated, and a sukūn on a plosive provides Mikhail with an opportunity to pause.

Figure 2. Mikhail, “al-ḥarbu taʿmalu bijidd,” transliteration of lines 1-9 with visualized oral analysis.

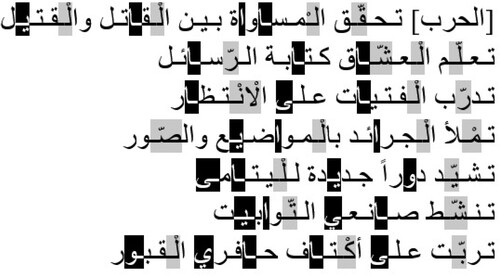

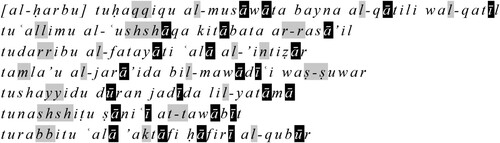

Besides being a diacritic, the word sukūn in Arabic means silence, stillness, calmness, and peace. Mikhail’s prolongation of sounds via sukūn allows the poem to pay tribute to those lost in the war, and to offset the permanence of war, all of which emphasize the temporality of her affective experience of ṭarab in performance. Time is suspended in the performance space as a synchrony of past, present, and future. The (e)motions animating her experience of ṭarab are not temporally bound; rather, they co-exist, commingle and even animate one another in its perpetual presentism and endurance, even when they refer to past or future events. For instance, Mikhail juxtaposes the elongation of euphonic sounds such as the sibilant /s/, the /n/ at the end of tanwīn and the /l/ in the definite article with words such as isʿāf (ambulance), juthathan (corpses) and al-jarḥā (the wounded). Time and duration are therefore essential to Mikhail’s own experience of affect while reading her poetry. Through the expansion of the temporal experience of each poem, Mikhail employs time as an occasion for stillness, for mourning, for feeling ( and ).

Figure 4. Figure 1: Mikhail, “al-ḥarbu taʿmalu bi-jidd,” transliteration of lines 32-38 with visualized oral analysis.

As such, the poem is permeated with images and metaphors that employ words with long vowels, sukūn or shadda. This produces semantically inarticulated affects (such as: ʿawīl, bukā’, hudū’), which inhabit the sounds of Mikhail’s oral performances.Footnote44 Hence, the musicality of her poems and their potentiality for affective ṭarab paradoxically hinges on this temporal suspension of sounds and silence through lingering sonic protractions, which are also instances of the non-referential voice.

The poet’s performance of her own poetry in Arabic encapsulates a reanimation of some of her affective experiences during poetic composition that evoke a different performance experience of ṭarab for herself, while temporarily denying the Anglophone audience semantic gratification through linguistic understanding. The potential evocation of ṭarab or wajd brought about by the acts of listening within the performance space is therefore paralingual, while also carrying new revelations of truth that could only be discovered by the listeners themselves, as illustrated by al-Ghazālī. The incomprehensibility of Mikhail’s oral performance of the Arabic poems recalls the discomfort created by a sonic encounter with a racialized Other. As Jennifer Stoever explains of the sonic color line, “sounds unable to be pinned down to a written, standardized vocabulary created discomfort, which whites resolved by representing nonverbal sound as the instinctual, emotive province or racialized Others.”Footnote45 An Iraqi-American immigrant, Mikhail’s body exists in the liminal space between belonging and unbelonging with reference to both countries as the US invasion of Iraq continues on in 2007 at the time of this performance. Her voice allows for the simultaneity of listening literacies and verbal incomprehension to echo across the liminal space of (un)belonging that her body opens up in this US academic context. Consequently, even though the oral poetry performance is unbound to any semantic referentiality, the senseless voice itself acquires an affective meaning, the kind of affective truth possibly revealed to the audience when listening in a state of wajd.

Eventually, Mikhail’s oral performance promises sonic translation which is “the trust in the ultimate translatability of aural … codes.”Footnote46 With reference to Austin’s theory of speech acts, Kapchan explains that the promise of sonic translation is the performative action in this encounter with the non-referential voice. Nonetheless, it does not ensure the audience’s development of sound knowledge. Kapchan suggests that the promise of sonic translation and the ensuing acquisition of sound knowledge are facilitated by the transduction of the affective force of ṭarab in its unreferential voicing and the discomfort this creates. The poet’s affective experiences of ṭarab invoked during performance are transduced to the audience through her voice, thereby interacting with their material bodies and prodding their own affective experiences of ṭarab through non-referential sound knowledge. Consequently, participatory and collaborative ṭarab is a form of affect contagion being transduced among the audience and performer through the performer’s voice and audience responses, generating sonic waves that prompt inter-affective knowledge.Footnote47 Caught in a soundscape whereby sense-less sounds are foregrounded, Mikhail’s anglophone audience are obliged to linger in the performance’s sonic space of discomfort, which allows sonic knowledge of the Mikhail’s ṭarab that eventually gets attached to her performance of the English translation, and throughout the whole process, decolonizes the performance space.

The (un)translatability of ṭarab in the performance space

In a US-university setting, Dunya Mikhail is also expected to perform her poetry in its English translation. Her performance of the translation raises compelling questions about the aural translatability of ṭarab to the English performance. Taking note of al-Jāḥiz’s premise that ṭarab undermines the translatability of Arabic poetry because of the inherent musicality of the Arabic language,Footnote48 can a listener not familiar with Arabic experience ṭarab during an English performance of translated Arabic poetry? Can “foreign” musicality, typically difficult to transmit in written translation, be conveyed in the performance of translation? Can Arabic poetry’s potentiality for ṭarab carry over to the oral performance of its translation? Basically, is ṭarab really exclusive to Arab(ic) performance, poetry and music?

Mikhail’s exile to the US induced her to reconfigure her poetic process. Mikhail has repeatedly stressed that even though she continues to write in Arabic and her style has not changed, she now composes her poetry with translation in mind. She picks phrases that would resonate well in English or translates her poetry after writing it in Arabic to make sure it works in both languages; “[her] writing goes from right to left then from left to right,”Footnote49 giving “[her] poetry … two lives, like any exile.”Footnote50 She thereby makes the Arabic poem amenable to the influence of the English language and subverts the so-called untranslatability of Arabic poetry. This process complicates what Walter Benjamin and Lawrence Venuti prescribe with regards to the role of the translator: maintaining faithfulness to the original text’s linguistic or cultural codes in order to limit the possible domesticating effect of the translation.Footnote51 Conversely, Mikhail semantically and syntactically domesticates her own text, even before its translation is possible. This does not result in a less affective animation of her composed poetry. Rather, it illustrates that the poet’s affective experiences have remodulated her experience of ṭarab. She is affected by the embodied shift to a context where she has to greatly rely on her third language, English, as a mode of communication in her everyday experiences and her writings. This ultimately generates poetic language of different feelings, thoughts, and sensations, and by extension, different affective experiences of ṭarab. Mikhail’s process of poetic composition does not entail the loss of ṭarab in oral performance. In fact, because Mikhail typically reads the Arabic poem alongside the translation, her poetry and its performance problematize the dichotomy of domestication and foreignization in translation.Footnote52 The oral performance upends the transparent naturalness of the familiar; ensuring the translatability of the meaning does not preclude the defamiliarizing effect of the sound.Footnote53 By juxtaposing the familiar word with the unfamiliar sound, Mikhail undermines the binding of ṭarab to Arabic poetry and its performance. In other words, ṭarab is not an exclusive effect of Arabic poetry on an Arabophone audience but can occur in sonic events where poetry is recited in its (in)comprehensible original language as well as its translation. Accordingly, ṭarab is an affective force that gives rise to poetic composition and/or performance and, in performance, makes the affective contagion of the different experiences of ṭarab within the performance space possible among performer and listeners.

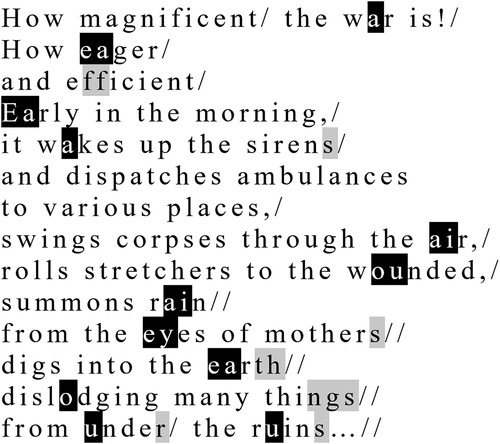

The non-referential affective experience of ṭarab resonating in Mikhail’s Arabic performances ultimately affects the performance of the translated poems, too. The protracted suspensions of sounds and silence in the performance of the Arabic poems bleed into Mikhail’s performance of the English translations ().

In the same opening verse of the translated poem, Mikhail makes recurrent pauses that interrupt the textual poetic lines, lengthens English vowels and creates phonetically unusual English geminates. In the English reading, Mikhail preserves as much of the rhythm of the Arabic through the elongation of many English vowels and consonants. Additionally, whether consciously or unconsciously, Mikhail’s performance of the English translations borrows the shadda ( ــّ ) from Arabic and makes geminates of “efficient” in this poem and “emigrants ” and “immigrants” when reading “Kuntu musriʿatan (I was in a hurry)” in another performance event.Footnote54 Therefore, her elongation of sounds and the ensuing evocation of ṭarab seep into her oral performance of the English translations. Furthermore, when reading the poem “America,” Mikhail orally performs a certain kind of stuttering.Footnote55 What might otherwise sound like “Please d … d … don’t ask me, America” becomes “Please do not … do not … do not ask me, America” in Mikhail’s performance of the poem. This aural suggestion of hesitation carries over from what in an Arabic reading of the poem would have been “lā … lā … lā tas’alīnī rajā’an, amrīkā.” The stammering in Arabic would be verbalized through the repetition of the tool of negation (lā), not by the repetition of the initial sound /l/. Mikhail’s verbalization of her affective experience of ṭarab while performing the translated poem destabilizes the conventions of standard English isochrony through this reverse colonization of English language prosody.Footnote56

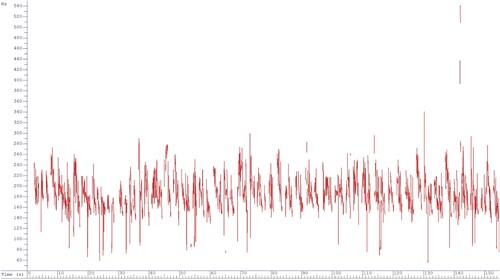

The latching of Arabic language prosody to Mikhail’s performance of the translated poems is more pronounced when her performance of “The War Works Hard” is compared to the translator’s reading of the translated poem in the Griffin Poetry Prize Ceremony. When analyzing the visualization of the oral performances of the poet and the translator, it is evident that the musicality of the poet’s performance, galvanizing the experience of ṭarab, is different from that of the translator’s (see and ).Footnote57 Mikhail’s performance illustrates a more regular rhythm and her fluctuation in pitch is much smoother and steadier, while Winslow’s reading displays sharper and more uneven oral variations in vocalizing the same poetic lines. Moreover, Mikhail’s pitch contour elucidates well-structured, evenly timed pauses throughout the performance. Yet, Winslow’s pitch graph demonstrates more sporadic pauses of uneven lengths.

This visible regularity in Mikhail’s pitch contour evinces the regulated musicality associated with Mikhail’s poetic experience of ṭarab in spite of the absence of meter (wazn) in the original Arabic poem. Mikhail’s poetic composition and performance, which rely on both English and Arabic, is predicated on the poet’s affective experience of ṭarab taking form in sonic waves that are transduced to the audience. Mikhail’s pitch contour illustrates that there is barely any difference in the oral performance of the poem in Arabic and in English. The first 25 seconds of the graph, which show Mikhail reading the opening verse of the Arabic poem, appear almost identical to other 25-second segments within Mikhail’s performance of the translated poem.

The poet’s experience of ṭarab as she reads the Arabic poem percolates into the reading of the English translation. On the other hand, the translator’s affective experience of the ṭarab is mediated by her own affective and oral interpretation of the poem. The poem is created through ṭarab as affective poetic inspiration when the poet shaʿarat in both senses of the word, she (1) felt and perceived as well as (2) versified. Mikhail’s performance later ensues from a different contextual ṭarab as an affective impetus. Her performance animates her affective experiences differently, creating a different experience of ṭarab that is transduced in only the first sense of the word shʿarat (feeling). On the other hand, when Winslow reads the same poem, her performance is affected by the first sense of the word, shaʿarat, but with reference to her own feelings. In other words, Winslow’s affective transduction of ṭarab is informed by her own (e)motional and embodied experience of interpreting and translating the poem. Translating is an act of reading, which in turn is a form of participating in the performance of the poem in its written form that animates the poem’s affects through the reader’s own mediated affects. This process of animation made possible through the translator’s reading leads to a participatory commingling of the affective ṭarab of both, the poet while composing and the translator while silently reading it. Unlike other readers, though, Winslow’s act of translating the poem is a linguistic rendering of the animation of affects made possible through her act of reading.Footnote58 So, even though she is not “Arab,” and she performs in English, Winslow’s performance still permeates the performance space with a type of ṭarab.

If ṭarab is not exclusive to sonic events since both Ibn al-Ṭaḥḥān and al-Ghazālī refer to visual scenes as possible evocations of ṭarab, why wouldn’t Winslow’s performance similarly arouse some ṭarab? Additionally, language—or Arabic more specifically—is sidelined in al-Ghazālī’s illustration of how wajd transcends comprehension when he exemplifies acts of listening by referring to a baby’s response to beautiful voices and a camel’s embodied reactions to the cameleer’s song. In the context of Winslow’s performance, this shows that the affective force of ṭarab being transduced within the performance space is quite different from that of the poet as a racialized other, and the discomfort her defamiliarizing voice elicits. To a certain extent, the translator’s interpretation aurally and affectively domesticates the poem’s potential for invoking the poet’s particular experience of ṭarab, because of its transmutation of the affective and sonic resonances of the poems. The semantic translation of the Arabic poem does not preclude its potential for ṭarab provided that sonic translation is also possible through the affective and affected voice of the poet, i.e. the transducer of affect.

Ṭarab and the aesthetics of orature and wajd

I have argued that ṭarab does not dwell in the Arabic diction; it dwells in affective intensities acting on bodies in solitary or social occasions. The affective forces creating the various experiences of ṭarab outlined in this article, including the poet’s ṭarab during poetic composition, her ṭarab during her performances, the translator’s ṭarab or the audience’s ṭarab, are by no means contingent on the poet’s language of composition or performance. Ṭarab is a porous category of affect that transcends language, promotes sound knowledge, and develops literacies of listening. Even though Dunya Mikhail writes and performs prose poetry, whose musicality has been questioned, her performances are highly evocative, which hearkens us back to al-Iṣfahānī’s reference to Abū al-ʿAtāhiyah’s praise of Hārūn Ibn Makhāriq’s speech. And speech may indeed evoke strong emotions. It is easy to imagine instances where we were moved by speeches or talks, political, academic, performative, etc. What all of emotive oral forms share is a potentiality for affect, and to a large extent a potentiality for ṭarab. And since ṭarab is not exclusive to any type of positive or negative affects, it may even point to the affective power of any emotive oral performance or delivery. Ṭarab is therefore an affective manifestation of orature as a system of aesthetics in this philosophy of interlinkage. It may very well be one shape of the porous and translucent scale binding one to the world around her in this onion-like structure of being.

Moreover, as another word for wajd, ṭarab also acquires the philosophical connotations of al-Ghazālī’s term for it. Wujūd, a nominal derivative of wajd, means existence or being, which points out that a philosophy of wajd—and by extension ṭarab—resonates with orature’s philosophy of multisensory modes of interconnectedness with the world. The coincidence of the two meanings of affective knowledge or truth and existence in al-Ghazālī’s wajd elucidates another aspect of collectivity attachable to the concept of ṭarab. It does not just refer to the community of singers and listeners and the self-presentation facilitated through this community. Ṭarab as a state of wajd refers to a far-reaching world collectivity in multi-sensory affective resonances that traverse occasions of linguistic (in)comprehension and eventually lead the participants in this world ṭarab culture to new truths.

Within these philosophies, regardless of an individual’s language, wajd or orature govern one’s affective relationships with the world. And the diversity of languages is a form of interconnecting with and expanding knowledge of the world as Abdelfattah Kilito shows:

Dissemination in space, diversity of tongues and colors: these are good things … The confusion of tongues is no curse … The expression, “the diversity of your languages” … means not only the diversity of spoken tongues, but also … the diversity of articulated sounds and pronunciation of words. Voice, like the color of the skin, varies from one individual to the next … There was no end to chaos until diversity came into creation, when variety was introduced into the cosmos-as well as into physiology and language. Plurality and heterogeneity are the conditions of knowledge. Knowledge of names and mutual recognition flow from the distinctions that exist between men, whether at the level of their voice or the color of their skin.Footnote59

Ultimately, as it creates this (non)referential potential for affect contagion, ṭarab promises sonic translation across diverse languages and puts pressure on the binary of translatability and untranslatability, as well as that of foreignization and domestication. Comprehension is no longer a necessary condition for the acquisition of sound knowledge or literacies of listening, which is realizable through the act of participating in a performance of orature that has been recorded in writing, sound, image, etc. And yet ṭarab remains translatable. Ṭarab itself is an act of translating one affective form to another through the materiality of a person’s voice. In certain ways, affective (un)translatability therefore nuances our understanding of translation as a process. Seeping from texts are the linguistic, cultural, and political environments that give rise to specific affective and embodied experiences. Acts of translation that account for affective specificities and literacies create possibilities for overcoming some of the challenges of (in)comprehension because of their mediation between recorded experiences and the participation in their affective performances.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Henriques, “Sonic Dominance and Reggae Sound System,” 469.

2 Eidsheim, Sensing Sound, 167.

3 Ibid., 170.

4 See Racy, “Creativity and Ambience,” 7–28.

5 Tomkins, Affect, Imagery, Consciousness I, 163. Tomkins suggests that the experience of a particular affect in oneself or others activates that affective experience in the subject, “the experience of disgust is disgusting, the experience of joy is joyful, the experience of excitement is exciting … the smile of the face of another is a specific activator of the smile of the one who sees it” (163–4).

6 See Brennan, The Transmission of Affect.

7 Mikhail, Al-ḥarbu taʿmalu bi-jid, 25–7.

8 Some of her other poetry collections include: Nazīf al-baḥr (The Bleeding of the Sea, 1986), Mazāmīr al-ghiyāb (Psalms of Absence, 1993), Yawmiyāt mawgah khārij al-baḥr (Diary of a Wave Outside the Sea,1999), and al-Layālī al-ʿIrāqiyya (Iraqi Nights, 2013).

9 Khan, “My Poetry Has Two Lives,” 13.

10 See al-Isfahani, Book of Songs [Volumes I–V].

11 Sawa, An Arabic Musical and Socio-Cultural Glossary, 282.

12 Qtd in Sawa 282 (my translation).

13 al-Isfahani, Book of Songs IV, 62.

14 Qtd in Sawa, An Arabic Musical and Socio-Cultural Glossary, 282 (my translation).

15 Racy, Making Music in the Arab World, 8. (author’s emphasis).

16 Figueroa, “Post-Tarab,” 244–50.

17 Shannon, “Emotion, Performance, and Temporality in Arab Music,” 79 (emphasis in original).

18 Ibid., 84.

19 Racy, Making Music in the Arab World, 69–71.

20 Ibid., 13, 173.

21 Shannon, “Emotion, Performance, and Temporality in Arab Music, 75.

22 Mikhail, “Ṣāniʿ ‘aḥdhiyya,” lines 1–8.

23 Mikhail, “Shoemaker,” trans. Elizabeth Winslow, lines 1–9.

24 In trainings of Qur’anic readings of al-qāf al-sākina, this phonetic effect is called qalqalah, suggesting some kind of bouncing rattle.

25 Thiong’o, Globalectics, 73, 83.

26 Adeeko, “Theory and Practice in African Orature,” 222. Since its initial introduction by the Ugandan linguist, Pio Zirimu, the concept of orature has been developed by Adélékè Adéẹ̀kọ, Pitika Ntuli, J. P. Clark-Bekederemo, Mĩcere Mũgo, and others, and yet remains a somewhat slippery term.

27 Thiong’o, Globalectics, 72.

28 Ibid., 75.

29 Ibid., 81.

30 Eidsheim, Sensing Sound, 179.

31 Ibid., 176–7.

32 For more on the audience’s role in sonic transmutations within performance spaces, see Eisenlohr’s Sounding Islam, Steintrager and Chow’s Sound Objects, Kapchan’s Theorizing Sound Writing and Racy’s Making Music in the Arab World.

33 See Lunch Poems: Dunya Mikhail.

34 My use of “prosody” here refers to the natural rhythms, intonations and stresses in a language, not metrical versification. I use prosody rather than rhythm because it is more expansive of the features of languages aurally detectable in speech.

35 Lunch Poems: Dunya Mikhail, 3:00–5:35.

36 Kapchan, “Learning to Listen,” 65; Kapchan, “The Splash of Icarus,” 2.

37 Kapchan, “Listening Acts,” 277 (emphasis in original).

38 al-Ghazālī, Iḥyā’ ʿUlūm al-Dīn (The Revival of Religious Sciences), 765.

39 Ibid., 766.

40 All quotes from al-Ghazālī are my translation.

41 al-Ghazālī, Iḥyā’ ʿUlūm al-Dīn (The Revival of Religious Sciences), 746.

42 Lunch Poems: Dunya Mikhail, 14:18–15:57.

43 Mikhail, “The War Works Hard,” lines 38–48.

44 In other performances of Arabic poems, such as that of “Ṣāniʿu ’aḥdhiya (The Shoemaker),” Mikhail adopts a similar oral performance. Mikhail pauses, stops and slows down time through her oral delivery.

45 Mikhail, “The War Works Hard,” lines 24.

46 Kapchan, “The Promise of Sonic Translation,” 467.

47 My understanding of affect contagion builds on Kapchan’s theory of sonic translation. In other words, I do not claim that affective contagion is an automatic reaction to ṭarab, leaping from the poet to her audience. Sarah Ahmed complicates Adam Smith’s model of affective contagion by emphasizing that sharing affect is contingent on “conditional judgment … To get along, in another words, is to share a direction.”

48 Kilito, Thou Shalt Not Speak My Language, 28–9.

49 Linh Che, “New Directions Interview with Dunya Mikhail.”

50 Khan, “My Poetry Has Two Lives,” 11.

51 See Benjamin’s “The Translator’s Task” and Venutti’s The Translator’s Invisibility.

52 On some occasions, not all the poems are read in both languages due to time constraints, but they are most often read in both Arabic and English.

53 For more on naturalness, fluency, transparency and accuracy associated with domestication in translation, see Venuti, The Translator’s Invisibility, 1–20.

54 The performance took place during the National Arab Orchestra event, “On the Shoulders of Giants: Arabic Women in Music,” which was held in the Detroit Music Hall Center for the Performing Arts on February 10, 2018.

55 Lunch Poems: Dunya Mikhail, 6:50–14:05.

56 In her poem “Colonization in Reverse,” Louise Bennett portrays migration as a willful resistance to the colonial history of subjugation on the colonies or the economic subordination of the colonial subjects on the homeland, namely, England. Written in creole, Bennett Coverley’s poem also undermines the imperialization of the English language and the resulting racialization of sounds, dialects, and accents.

57 The visual analysis of the oral performances was conducted using pitch tracking through an open-source speech analysis software called WASP. The software was developed by Professor Mark Huckvale, from the University College of London.

58 This is similar to what happens when a singer animates a poem for a musical performance. As Racy notes in Making Music in the Arab World, “the singer’s own textually induced ecstasy is projected onto the audience … [and] his emotional delivery gains emotional efficacy through the inspirational input of the responsive listeners.” While Winslow is not a singer but as a performer of Mikhail’s poem, she invokes her own experience ṭarab rather than the poet’s experiences, simply because she cannot.

59 Kilito, Tongue of Adam, 23–4.

Bibliography

- Lunch Poems: Dunya Mikhail. YouTube Video, 2007. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v = NBPAOMENpn4&list = PLPx1jt-VO_TGeJZdrzLjvifZs4FyMI-r-&index = 5.

- Poet Dunya Mikhail and Translator Elizabeth Winslow Read from The War Works Hard. Accessed December 20, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v = T2yg4-dLTnY&list = PLPx1jt-VO_TGeJZdrzLjvifZs4FyMI-r-&index = 3.

- Adéẹ̀kọ́, Adélékè. “Theory and Practice in African Orature.” Research in African Literatures 30, no. 2 (1999): 222–227.

- Ahmed, Sara. “Happy Objects.” In The Affect Theory Reader, edited by Melissa Gregg and Gregory J. Seigworth, 29–51. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010.

- al-Ghazālī, Abū Ḥāmid. Iḥyā’ ʿUlūm al-Dīn (The Revival of Religious Sciences). Beirut: Dār Ibn Ḥazm, 2005.

- al-Iṣfahānī, Abū al-Faraj Alī Ibn al-Ḥusayn. Kitāb Al-Aghānī. 3rd ed. Beirut: Dār Ṣādir, 2002.

- Benjamin, Walter. “The Translator’s Task." Translated by Steven Rendall. TTR: Traduction, Terminologie, Rédaction 10, no. 2 (1997): 151–165.

- Bennett, Louise. Jamaica Labrish: Jamaica Dialect Poems. Jamaica: Sangsters, 1966.

- Brennan, Teresa. The Transmission of Affect. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2014.

- Eidsheim, Nina Sun. Sensing Sound: Singing and Listening as Vibrational Practice. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015.

- Eisenlohr, Patrick. Sounding Islam: Voice, Media, and Sonic Atmospheres in an Indian Ocean World. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2018.

- Figueroa, Michael A. “Post-Tarab: Music and Affective Politics in the US Swana Diaspora.” Ethnomusicology 66, no. 2 (Summer 2022): 236–263. doi:10.5406/21567417.66.2.04.

- Henriques, Julian. “Sonic Dominance and Reggae Sound System Sessions.” In The Auditory Culture Reader, edited by Michael Bull and Les Back, 451–480. Oxford: Berg, 2003.

- Huckvale, Mark. “SFS/WASP” V. 160. The University College of London, 2019. https://www.phon.ucl.ac.uk/resource/sfs/wasp/.

- Ibn al-Ṭaḥḥān. Ḥāwī al-Funūn wa Salwat al-Maḥzūn (The Art Keeper and the Peace of Mourners). Baghdad: dā’irat al-funūn al-mūsīqiyya, 1971.

- Kapchan, Deborah. “Learning to Listen: The Sound of Sufism in France.” The World of Music, Music for Being 51, no. 2 (2009): 65–89.

- Kapchan, Deborah. “Listening Acts: Witnessing the Pain (and Praise) of Others.” In Theorizing Sound Writing, edited by Deborah Kapchan, 277–293. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2017.

- Kapchan, Deborah, ed. “The Splash of Icarus: Theorizing Sound Writing/Writing Sound.” In Theorizing Sound Writing, 1–22. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2017.

- Kapchan, Deborah. Theorizing Sound Writing. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 2017. https://muse.jhu.edu/book/49846.

- Kapchan, Deborah. “The Promise of Sonic Translation: Performing the Festive Sacred in Morocco.” American Anthropologist 110, no. 4 (December 2008): 467–483.

- Khan, Sobia. “‘My Poetry Has Two Lives, Like Any Exile’: A Conversation with Dunya Mikhail.” World Literature Today 89, no. 5 (2015): 10–13. doi:10.7588/worllitetoda.89.5.0010.

- Kilito, Abdelfattah. Thou Shalt Not Speak My Language. Translated by Waïl S. Hassan. Middle East Literature in Translation. New York: Syracuse University Press, 2008.

- Kilito, Abdelfattah. The Tongue of Adam. Translated by Robyn Creswell. New York: New Directions, 2016.

- Marks, Lawrence E. The Unity of the Senses: Interactions among the Modalities. New York: Academic Press, 1978.

- Mikhail, Dunya. “New Directions Interview with Dunya Mikhail. Interview by Cathy Linh Che.” Blog, April 7, 2010. Cantos: A New Directions Blog. https://ndpublishing.wordpress.com/2010/04/07/new-directions-interview-with-dunya-mikhail/.

- Mikhail, Dunya. “Q-and-A with Award-Winning Iraqi Poet Dunya Mikhail. Interview by Meg Fowler.” The Eagle, March 3, 2010. https://www.theeagleonline.com/article/2010/3/q-and-a-with-award-winning-iraqi-poet-dunya-mikhail.

- Mikhail, Dunya. Nazīf Al-Baḥr (The Bleeding of the Sea). Baghdad: Manshūrāt ‘Āmāl al-Zahāwī, 1986.

- Mikhail, Dunya. Mazāmīr Al-Ghiyāb (Psalms of Absence). Baghdad: Dār al-‘adīb al-baghdādiyya, 1993.

- Mikhail, Dunya. Yawmiyāt Mawgah Khārij Al-Baḥr (Diary of a Wave Outside the Sea). Cairo: Dār ʿIshtār, 1999.

- Mikhail, Dunya. Al-ḥarbu taʿmalu bi-jid. Baghdad: al-madā, 2000.

- Mikhail, Dunya. The War Works Hard. Translated by Elizabeth Winslow. New York: New Directions, 2005.

- Mikhail, Dunya. Al-Layālī al-ʿirāqiyya (Iraqi Nights). Baghdad: Dār mīzūbūtāmiyā, 2013.

- Racy, Ali Jihad. “Creativity and Ambience: An Ecstatic Feedback Model from Arab Music.” The World of Music 33, no. 3 (1991): 7–28.

- Racy, Ali Jihad. Making Music in the Arab World: The Culture and Artistry of Tarab. Cambridge Middle East Studies. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Sawa, George Dimitri. An Arabic Musical and Socio-Cultural Glossary of Kitāb al-Aghānī. Islamic History and Civilization 110. Boston, MA: Brill, 2015.

- Shannon, Jonathan H. “Emotion, Performance, and Temporality in Arab Music: Reflections on Tarab.” Cultural Anthropology 18, no. 1 (February 2003): 72–98. doi:10.1525/can.2003.18.1.72.

- Steintrager, James A., and Rey Chow, eds. Sound Objects. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019.

- Stoever-Ackerman, Jennifer. “The Word and the Sound: The Sonic Color-Line in Frederick Douglass’s 1845 Narrative.” SoundEffects—An Interdisciplinary Journal of Sound and Sound Experience 1, no. 1 (2011): 19–36. doi:10.7146/se.v1i1.4169.

- Thiong’o, Ngũgĩ wa. Globalectics: Theory and the Politics of Knowing. New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2012.

- Tomkins, Silvan S. Affect, Imagery, Consciousness. Vol. I. 4 vols. New York: Springer, 2008.

- Venuti, Lawrence. The Translator’s Invisibility: A History of Translation. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge, 2008.