ABSTRACT

This article proposes an educational intervention model from Educommunication, integrating communication, pedagogy, information technologies and human development principles. The methods used included, first, an exploratory and quantitative procedure to identify the theoretical foundations of Educommunication and critical attitudes. Then a qualitative procedure was carried out to analyse the reference texts. This resulted in an ad hoc objective corpus that allowed the integration of the main strands of Educommunication and provided epistemic support for the model. The development of the corpus also led to the identification of the field’s advances, thus creating theoretical constructs based on the question of how to promote critical attitudes through Educommunication. The model highlights the link between education and ICT development and aims to promote critical attitudes through seven dimensions: media literacy and communication, relationship with others, hypertext, curricular aspects, technology use, methodology and learning objectives.

1. Introduction

In a globalised world with an abundance of content on the internet, educational institutions at all levels, and especially teachers, are forced to radically change their pedagogical, curricular and didactic methods. The condition of free access to information of all kinds exposes everyone to data of high scientific quality, but also to false, exaggerated and biased information. This requires a critical attitude towards the confusing and inexhaustible sources of information to discriminate and generally process what is relevant in each context.

In this order of ideas, it is necessary to generate interventions that allow the development towards the complexity of thinking, which opens a space for articulating, restructuring and/or creating new proposals for approaching education. Based on this situation, the following question was posed as a research problem: How to promote a critical attitude in students through Educommunication? Responding to a contextual problem such as how to help teachers introduce technology into their pedagogical designs in a way that supports and fosters students’ critical thinking. Answering this question requires not only thinking about how to do it (pragmatic application), but also thinking about how to ensure strong theoretical support (epistemic background) for any strategy or technique that any educator might design.

Readers will find a proposal that supports the basic elements of a pedagogical model as a particular way of approaching curricular problems, the teacher–student relationship, the didactic approach, evaluation, among other elements.

Thus, this study intends to offer educators and, in general, people interested in the field of education, the possibility of a model educational intervention from the confluence of Educommunication and Technology that breaks the existing barriers between pedagogy, Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) and human development. More precisely, it presents a model of intervention from Educommunication to develop a critical attitude. Consequently, the article itself aims to consolidate tools and concepts that articulate some constructs based on theoretical and practical assumptions of education, communication and ICT.

It is worth noting that there is no model in the literature as such that is proposed with the objective of generating a critical attitude from Educommunication, with the convergence of the concepts and tools of this proposal. Several authors have made attempts to solve the integration of ICTs from perspectives such as Problem-Based Learning (PBL), games, collaborative learning in digital media, virtual reality, among others (Azar & Tan, Citation2020; Bedregal-Alpaca et al., Citation2020; Brooks et al., Citation2021). There are multiple efforts based on multiple elements of education or ICT, but none of the work integrates a model.

The definition of Educommunication included in the article implies the use of media and other elements that communication offers, such as the analysis of texts or audiovisual messages to recognise categories; these are subjected to debate and interpretation according to previously determined patterns. This is very useful because it promotes the critical attitude, which implies the reflection of findings from the reading that values the results, and emphasises interpretive strategies and, above all, rethinking the possibilities of change and transformation to move towards creative thinking (Alvarado, Citation2012).

On the other hand, there are several applications for the educational question from the field of education and from the incorporation of ICT (Alvarado, Citation2012; Ahuactzin Martínez & Meyer Rodríguez, Citation2017; Bermejo-Berros, Citation2021; Chen, Citation2018; Freire, Citation1967; Jenkins, Citation2018). A careful review of the literature reveals a wide range of works on educommunication, as well as many others on the development of critical thinking and attitudes. These works range from epistemological topics (De Oliveira Soares, Citation2009; Parra, Citation2000) to different applications in contexts of education for citizenship, childhood, adolescence, etc (J. I. Aguaded, Citation2014; Falco, Citation2017; Kaplún, Citation1992; Romero-Rodríguez et al., Citation2019).

In fact, there are several approaches of Educommunication in different fields of knowledge, but so far there are no proposals for the configuration of an independent educational model. For this reason, this proposal is completely new. In the same sense, Bermejo-Berros’s (Citation2021) remarks on the obstacles to achieving such a model, based on the lack of a conceptual structure, are pertinent. In this sense, he states that ‘if Educommunication intends to promote autonomy, creativity, dialogue and critical thinking, it must review and expand the concepts it uses’ (p. 112).

This explains, at least in part, why, to date (2022), there are no works that really relate Educommunication to the promotion of a critical attitude, and certainly none that has the objective of proposing an intervention model from Educommunication and ICT to promote it.

To provide the above-mentioned epistemic support, research was carried out on the basis of an ad hoc corpus. It is a methodology commonly used in linguistics that implies a collection of texts that are used with specific criteria and purposes (Ahuactzin Martínez & Meyer Rodríguez, Citation2017). It consists of identifying a set of documents that appear to be representative of a topic or knowledge domain. This allows researchers to construct a timeline of scholarly production, the impact of selected authors or the structure of a given field itself, among many other possibilities. In this case, the use of the ad hoc corpus led to an effective combination of contents of the two main currents that underlie Educommunication: the notion of media literacy related to the use of technologies and the one that promotes education and human development (Bermejo-Berros, Citation2021).

In addition, the researchers processed the collected data using VOSviewer and ATLAS.ti software. Thus, a delimitation of concepts and elements that make up the foundations or guidelines, as products of the review and evaluation of the selected texts according to the criteria of relevance to the object of study and timeliness or validity theories, which leads to the achievement of the purpose of the work.

The result was a model of educational intervention elaborated from a corpus for the application of Educommunication as a methodology in the educational task. Its characteristics were related through seven dimensions: media literacy and communication, relationship with others (teacher-partners), hypertext, curricular aspects, use of technologies, methodology and learning objectives conceived from a collective construction. Finally, as a limitation, the condition of being theoretical is mentioned. That is, a pilot test has not yet been carried out in practice that would allow measuring its impact.

The article contains the present introduction, a brief theoretical background extracted from The corpus ad hoc, a methodology that explains the design of the ad hoc corpus, which is little used outside the field of linguistics but is very useful for obtaining meaningful categories with the objective of making it replicable.

2. Theoretical background

2.1. Educommunication, audiovisual society, education through communication and media literacy

The immense development of information technologies became one of the processes that characterised the new social framework baptised the network society (Castells, Citation2001, p. 548). As a result, a new type of citizen is emerging with new habits and social values, new interests and different ways of feeling and even thinking.

The network society that Castells refers to is the social structure influenced by a series of networks, supported by digital communication and information technologies, which generate a new form of social bonding. It is an implicit agreement of relations between people that determines their relationship with production, consumption and communication. This framework constitutes the so-called audiovisual society, which includes the convergence of media, sources, languages and systems of meaning (C. Scolari, Citation2008). These convergences bring the possibility to develop new educational environments.

Educommunication, on the other hand, according to Barbas (Citation2019), is approached as a field of theoretical-practical studies that articulate these two disciplines of social and human sciences, stressing that the result of this convergence cannot be understood only as the mere addition of one knowledge to the other. Aparici and García Matilla (Citation2016), for their part, stated that among the purposes of Educommunication is the intention to offer people expressive skills for their normal communicative development. This would necessarily lead to creativity, which should be evident in people’s understanding of the processes of social production of communication in relation to the structures and flows of power. In other words, this should allow subjects to better evaluate the media, the techniques they use and the messages they propagate, with a healthier criticism.

The acquisition of media competence and the critical attitude that Educommunication consequently seeks is related to the organisation of the educational activity and the socio-historical-cultural context in which it is developed (Bermejo-Berros, Citation2021, p. 112). This attributes relevance to the subject’s relationship with the other in the mediation of the pedagogical act, proposing another type of social bond. One way to approach this relationship of the subject with the other, according to Jenkins (Citation2018), is the society of collective intelligence and convergence because it is in the collective that our way of relating and communicating, accessing, consuming and producing information is transformed.

Linked to the culture of convergence is the concept of collective intelligence, which, according to Lévy (Citation2004), should be understood not as

the fusion of individual intelligence, in a kind of indistinct magma; collective intelligence is a process of growth, differentiation and mutual reactivation of singularities. It constitutes for the collective a new mode of identification [ultimately it is] the mutual valuation and impulse of the particularities of each one. (p. 103)

In the same sense, Jenkins defined knowledge and understanding that emerge from large groups of people as collective intelligence. Precisely, the issue of collective performance arises from the above. According to Jenkins (Citation2018), the answer lies in the convergence culture, assumed as the space where the old and the new come together and in which different contents and different media platforms are mixed. Technological transformations take place with their corresponding cultural and social consequences in this space. It is also where subjects search for information and connect the different contents spread across networks and media platforms.

Currently, management proposals based on collective intelligence (CI) have as essential factors interaction, interactive learning, distributed collaboration and the valorisation of knowledge in all its dimensions (Figueroa & Pérez, Citation2018). The consumer of information re-signifies it from his or her cognition and subjectivity and returns a construction that enters to conjugate with those of others. The result is an interaction of knowledge that structures a new social relationship mediated by technological support. This allows navigation between knowledge. According to Lévy, this ‘embodies the ideal of scientists, artists, entrepreneurs or network activists who want to improve collaboration between people, who explore and bring to life different types of collective and distributive intelligence’ (Lévy, Citation2004, p. 8).

In the same spirit, in an empirical study, Chen (Citation2018) concluded that:

the principle of fostering a sense of shared purpose mediated by new media and online communities is strongly associated with the efficacy of intelligence gathering, which is defined by how young people perceive their ability to collaborate with others and make contributions.

These forms of connection already exist in the network and have produced social, political and economic transformations. Even the identity of citizens interacting between the analogue and the digital has been resized. All of the above has given rise to new social practices typical of the net generation (Chen, Citation2018).

2.1.1. Educommunication, ICT, e-learning and hypertext

At this point, the way ICTs are integrated into the process is relevant. It is emphasised that they should not be understood only as a mediating element to be used casually. They are the platform on which Educommunication is based. This is so not only because they are used for the exchange of participants, the search for information or the creation of content, but also because they support the structure of the academic work. The basic idea is that Educommunication accepts the notion that audiovisual media are effective in education, but also under the condition of articulating a good pedagogical proposal to achieve these objectives (Sánchez Peña & Riaño, Citation2019.

In the formulations of C. Scolari (Citation2008), an important contribution to this adaptation can be found in the following assumptions:

Technological transformation (digitalisation)

Many-to-many configuration (reticularity)

Non-sequential textual structures (hypertextuality)

Convergence of media and languages (multimediality)

User participation (interactivity)

Virtuality

Modularity

According to C. Scolari (Citation2008), reticularity responds to ‘a network of users interacting with each other, mediated by shared documents and communication devices’ (p. 98). In a complementary way, interactivity refers to the user’s ability to transform the flow and form of presentation of content in new media: ‘by participating in the control of content, the use of interactive media ends up becoming part of that content’ (C. Scolari, Citation2008, p. 98). This naturally leads to a decentralisation of the teacher’s place, providing a horizontal network that makes the relationships between participants.

In terms of interactivity, Ito et al. (Citation2010) identified three levels or categories: hanging out, messing around and geeking out. These range from simple friendship interaction to more focused forms of interest-driven participation experiences around new media. The latter happens to be the highest category of interactivity because it refers to design and production and involves a high level of expertise.

On the other hand, multimediality or rhetorical convergence can be understood as something that goes beyond the sum of media on a single screen, since ‘languages begin to interact with each other and hybrid spaces emerge that can give rise to new forms of communication’ (C. Scolari, Citation2008, p. 104). According to Vixtha-Vázquez (Citation2017), multimodality offers two advantages: first, the diversity of media and languages allows students to learn in different ways that better suit their tastes and abilities. The attention to non-sequential textual structures forces us to think about what type and modalities of documents and inputs are needed to transmit knowledge from Educommunication.

The second advantage is that the access to the multidimensionality proposed by C. Scolari (Citation2008) on an object of study allows us to produce an epistemic approach, i.e. to generate knowledge and not only information. In this sense, when the cognising subject appropriates the knowledge, he/she can then transfer it to different situations. This is fundamental, especially in the social sciences, a field in which there is too much paper or magnetic literature, so to speak, but which presents many difficulties in its implementation or operationalisation in contextual problems.

According to C. Scolari (Citation2008), hypertext is another important input because of its characteristics. For Landow (Citation2009), it is a text composed of blocks of words electronically linked in multiple paths, chains or routes in open textuality. It is eternally unfinished and is described in terms of nodes, network, plot and path. Its beginning is undefined, allowing the reader to begin reading at different points. This is a peculiarity of hypertext: discontinuity. But hypertext also implies new ways of reading and a different way of constructing meaning. It contains a latent meaning and a manifest meaning. This assessment coincides with the approach of Rodríguez (Citation2015), in which he emphasised that even when confronted with the same group of words that constitute an identical text, reading it from a printed source or a screen will affect the execution of the processes that lead the subject to the creation of meanings. In this order of ideas, when the process changes, at least some of the product changes.

According to Rossi (Citation2001), the power of hypertext systems lies in the possibility of using them also as a vehicle for the storage and retrieval of information, allowing access to it from different perspectives, encouraging the exploration of new ideas, comparative studies and the analysis of data from different sources. In this regard, C. A. Scolari (Citation2012) stated that ‘if text used to be a solid entity with well-defined boundaries, it is now transformed into a flow that leads us to think of a liquid textuality’ (p. 21) that glides without beginning or end. This characteristic of hypertext makes it an excellent product for a critical stance since it allows for a multiplicity of interpretations.

It should be noted that modularity implies a task separate from the sequencing of content. Knowledge, from this perspective, is non-linear and not hierarchised in a specific order. This brings the possibility of diachrony and allows access to many. Finally, it should be noted that virtuality and digitality have revolutionised communication, allowing hypermediation to be understood as exchange, production and symbolic consumption in an environment characterised by many subjects, media and languages (C. Scolari, Citation2015).

This conjuncture makes room for the interdisciplinarity proposed by organisations such as the OECD and UNESCO to approach and identify contextual problems. The question of a critical attitude arises, because if people can analyse the content they access, they can reflect on it and synthesise it. Thus, it can be said that what is expected of the educational work that emerges from the field of Educommunication is the exercise of dialectical criticism, a method that seeks truth through dialogue, in which a concept is confronted with its opposite (thesis and antithesis), to then arrive at synthesis (Alvarado, Citation2012). It is about appropriating the resources of theories and media and enriching learning.

Consequently, a proposal focused on educommunication for the development of critical attitudes requires the development of certain cognitive processes that allow abstraction. As Parra (Citation2000) stated, it is necessary to identify, differentiate, assimilate, analyse and synthesise the values and particularities of reality objects beyond the apparent or manifest. The method is based on the idea that to achieve a critical capacity, it is necessary to begin by promoting cultural decoding and interpretation of the ideology of the messages so that they can be analysed. This leads to taking positions on these messages, but it is not necessary to persuade students to do so. It is more valuable to give them tools to take control and consequently modify the cognitive structure.

2.1.2. Educommunication, pedagogical alternative and curriculum

With the growth of e-learning, there is talk of a paradigm shift (Bozkurt & Hilbelink, Citation2019) to the extent that virtual tools facilitate methodologies such as learning through animation, interactive media or live international conferences from attractive and globally recognised academic scenarios. However, according to Narváez (Citation2021), ‘most works do not ask whether schooling or pedagogy can improve media communication or vice versa, reducing the relationship between education and communication to the unilateral action of the media’ (p. 31).

Consequently, this paradigmatic shift has not yet affected pedagogy with the rigour necessary to respond to these new spaces. This makes the transformation of the pedagogical model imperative, as stated by Dole et al. (Citation2016). They affirmed that new pedagogies ‘will require changes in teacher-student relationships, in teaching and learning strategies, and in how learning is assessed, as the skills needed in the 21st century may not be amenable to paper-and-pencil tests’ (p. 1). In the same vein, Bower et al. (Citation2015) stated that the traditional classroom is no longer the ideal place for education. We live in an era where a collaborative learning culture is merging with an increasingly hybrid technological environment.

Educommunication based on media education proposals has already permeated some curricula and pedagogical proposals. For example, the one that has been implemented in Spain since the Thessaloniki meeting (UNESCO, European Commission) in March 2003, in which it was urged to consider a:

General curriculum to develop the teaching capacity of secondary school teachers at two levels: a first level to address basic content and pedagogical methods related to media education, and an advanced level to incorporate media education and the pedagogical process associated with media education within disciplines such as language, science, social, art, etc.

However, there is no experience of extrapolating Educommunication as a pedagogical model and as a curricular model.

Nevertheless, if it wants to be generalised as a model, it must expand the concepts, analyses, tools and methods used (Bermejo-Berros, Citation2021). The above implies carrying out a complex exercise that allows elements such as the pedagogical model, the curricular model, the teacher–student relationship, the evaluation and the sources of information to be linked under a specific training concept that promotes different dynamics. The access to media and communication strategies influences the cognitive processes; the construction mediated by the concept of collective intelligence promotes creativity and places the participants in a dynamic of the next development zone.

2.1.3. Educommunication and critical attitude

As previously mentioned, according to Alvarado (Citation2012), Educommunication considers reflective practices as analytical exercises. It also assumes the implication of classifications of content, referring to categories that, in turn, are related to previously determined patterns that result from the debate and clarifications in a certain group of people. This author also stated that the critical attitude implies the ability to think deeply, which is manifested in obvious results that come from a variety of ways of interpreting messages, leading to what is understood as creativity.

Consistent with this assessment, a critical attitude refers to certain forms of thinking that include metacognition as a mechanism that leads to ‘thinking about what is thought. Therefore, it is a self-reflective process that develops how to learn to think and do it autonomously, without adhering to limited or predetermined approaches’ (Alvarado, Citation2012, p. 105).

According to Causado et al. (Citation2015), in most cases the concept is not even perceived as difficult; teachers and researchers consider the development of critical thinking as a natural result of the teaching they develop in their programmes. However, if some coordinates are defined regarding what a critical attitude is, that is, if certain desirable characteristics are established, it can be concluded that not every pedagogical model promotes this type of thinking. Taking Parra’s (Citation2000) proposal as an example, the results should be:

–Understanding. Transfer of knowledge from one horizon to another.

–Locating. Processing and using information.

–Analysis. Synthesising and relating; looking for causes and anticipating consequences.

–Think in totality. Capturing the indeterminacy between phenomena to express, communicate, relate and collaborate with others.

–Criticise. Appropriating history and culture to imagine and invent.

–Feeling. Facing and solving problems; evaluating situations and making decisions.

Once these coordinates have been described, it can be affirmed that the expected educational work that emerges from the field of Educommunication is the exercise of a dialectical critique, a method that seeks the truth through dialogue, in which a concept is confronted with its opposite (thesis and antithesis), to then arrive at the synthesis (Alvarado, Citation2012, p. 103). It is about appropriating the resources of theories and media and enriching learning.

3. Methodology

This is a mixed type of research – quantitative/qualitative – using the ad hoc corpus as a methodology. The design corresponds to cross-sectional research and includes data analysis using VOSviewer and ATLAS.ti V8. The sample for the analysis included literature from 10 databases from the last 10 years and books by a representative author The research group worked with the methodology of creating an ad hoc corpus. It is a term coined by Aston and Kübler (Citation2010) that is also called by different names, such as virtual corpus (Ahmad et al., Citation1994), corpus specials (Sánchez-Gijón, Citation2009) and customised corpus (Austermühl, Citation2012). According to Pastor (Citation2002), when compiling this type of corpus, the goal is not only to solve a specific problem, but also to ‘collect all available documentation on a topic in a short time’ (p. 195). Thus, the researcher resorted to this methodology in order to collect and analyse as much information as possible in the shortest possible time, based on documents obtained from the internet, following specific design criteria in order to obtain the most appropriate degree of representativeness achievable.

The ad hoc corpus promotes empiricism and the treatment of real data rather than intuition and aims to collect as many specific documents on a topic as possible in a short period of time. Although this corpus is relatively unbalanced and limited in scope, it is a practical tool because its content is homogeneous (Pastor, Citation2001). The documents used for its elaboration in the current study were selected according to subject matter and relevance, from specialised databases, accessible and available on the Web, the sine qua non of an ad hoc corpus. In this way, the methodology made it possible to select the most relevant theoretical foundations, either because of their roots, which in this case refers to the number of times they are cited or appear in the various databases and search engines, or because of the recognition of so-called classic texts and authors, that is, authors widely recognised in the medium for their impact on the discipline or subject. The texts indexed in high-impact journals were also selected, which allowed us, on the one hand, to recognise the evolution of the topics studied until reaching the spearhead. This spearhead showed the knowledge gap that opened the question and, therefore, the purpose of this study.

The conceptual structuring of a model, as we understand it, consists in representing each of the dimensions that are part of the discipline or field by relating them to each other through their meaning, or as López Mateo and Olmo Cazevieille (Citation2015, p. 2) said, ‘it shows the arrangement of the field of knowledge of a given discipline’. The ad hoc corpus makes it possible to reduce and articulate these dimensions, which is why it was chosen as the method for this study.

The search was also extended to documents such as scientific articles, books and book chapters in English and Spanish, with the inclusion criteria being a bibliography written in the last 10 years. The next step in the protocol of the corpus creation is the storage of information for further coding. For this purpose, a mixed methodology was used for the subsequent analysis. On the one hand, a quantitative one led to the construction of the bibliometric maps, selecting the most significant categories of strength or occurrence. For this purpose, the researchers used the VOSviewer software.

This is a bibliometric network visualisation tool developed at the Center for Science and Technology Studies (CWTS). On the other hand, ATLAS.ti V8 was used to consolidate the categories and group the topics. This laid the groundwork for the content structure of the thesis.

With this, the most relevant trends, authors and topics in the fields have been identified and the location of the gaps to answer several questions, among which the question of this article, i.e. how to promote a critical attitude in students through Educommunication. It also answers the question of a way to address the gap between ICT and education and the assumptions that can conceptually expand Educommunication to contribute to educational change, through the articulation of a model built with the categories provided by the ad hoc corpus.

The dimensions obtained from the corpus allow the approach of the pragmatics of the field of Educommunication and its contribution to the production of critical thinking. According to Narváez (Citation2021), pragmatics refers to:

the nature of relations between subjects in the field. Since all interaction is pragmatic, it is about knowing what is to be done in each field. Whether it is to produce new knowledge (grammar), to decide (politics), or to maintain a protocol or functional orientation. (technique)

In this case, the aim is to obtain a model that allows responding to the know-how in the field of Educommunication to promote critical thinking in educators and, in general, in those interested in the subject.

3.1. Obtaining the model from the corpus

First, it should be emphasised that the model emerged because of research conducted between August 2018 and June 2021. The baseline documentary review was initiated with the descriptor Educommunication (Spanish and English) as the first search criterion. The researchers performed the information analysis with a total of 10 databases. Three of them yielded no results. The other seven yielded 295 articles; as described in , these databases were chosen because of the quality and reliability of the journals indexed in them.

Table 1. Databases for data collection.

Initially, this exercise led to the identification of the lines of work in Educommunication and their interconnections, based on the information contained in international databases. This made it possible to define the path of a scientific field and to delimit the traceability of the thematic groups that make up the field of Educommunication. Then, the search criteria used were the terms critical attitude, educommunication, education and information technologies in different combinations (in Spanish and English), through the Boolean operators ‘xor’, ‘and’ and ‘or’.

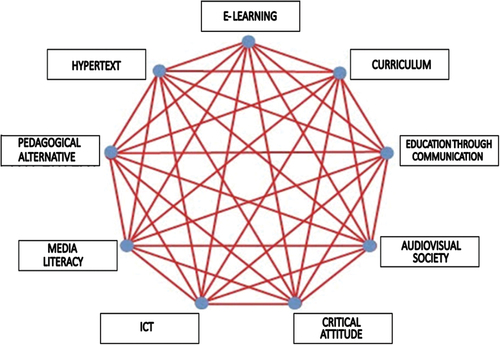

The researchers selected the documents according to subject matter, relevance and level of expertise, following the research objectives and the research problem posed. Once the research topics of the scientific papers published until 2021 were visualised, the authors analysed the co-occurrences between keywords or terms used in the abstracts through two-dimensional bibliometric maps. The methodology for constructing the bibliometric maps was divided into four stages: 1) data collection, 2) selection of units of analysis, 3) calculation of the frequency of co-occurrences, and 4) positioning and visualisation of the corresponding units of analysis in two-dimensional maps. The VOSviewer software was used for the quantitative data processing, as it allowed the selection of the relevant categories for the construction of the model.

The creation of the maps involved word analysis with clustering and visualisation techniques. To configure a representative sample of thematic clusters, only keywords with frequency ≥ 3, i.e. appearing at least three times in the retrieved scientific output, were selected. The researchers did not place any emphasis on the clusters obtained, nor on the co-occurrences of authors, but only on the thematic timelines to locate the article topic of interest. Therefore, only the analysis and the graphs corresponding to this information are presented in the results.

3.1.1. Quantitative and qualitative analysis

The second step was a qualitative content analysis. The qualitative analysis was carried out in order to examine the characteristics of the selected documents, which made it possible to establish that they corresponded to the issues to be addressed and to clarify the dimensions to be selected, which were then quantified in order to prioritise them according to their roots and, consequently, to establish the categories of the model.

This took up the objective proposed by Piñuel (Citation2002): to collect and process relevant data in the same conditions in which texts or communicative products are produced. In order to achieve the other objective, which was ‘to achieve the emergence of that latent meaning that comes from the social and cognitive practices that instrumentally resort to communication to facilitate the interaction that underlies concrete communicative acts and underlies the material surface of the text’ (p. 4), Piñuel included the following steps: selection of the topic, selection of the categories, selection of the units of analysis and selection of the counting or measuring method (p. 7), which in the case of this work was carried out with ATLAS.ti V8 software.

Ninety-seven documents were processed using ATLAS.ti V8. The procedure involved coding the different documents to identify the outstanding elements according to the Educommunication search criteria. This made it possible to identify trends, the depth of the topics, how they were treated and the gaps in the conceptual structure decisions.

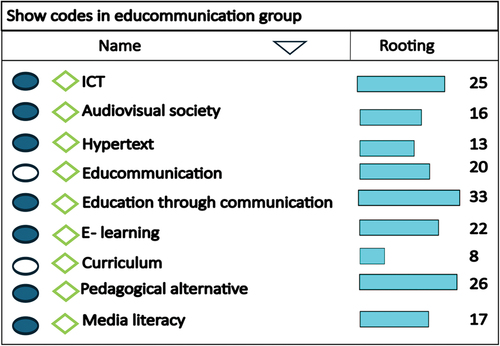

Once the structural elements for the theme had been selected, eight of the ten items or subcategories resulting from the analysis were included (), based on the criterion of less rootedness – the number of times a content is associated with a code or category – within the research products.

Table 2. Keywords and rooting.

One of the maps obtained in VOSviewer is shown below. The results show the clusters with the most frequently used variables/categories in the reviewed articles from 2012 to 2021 (both included). shows the clusters around each of the topics defined in the initial search (see ). Colours distinguish these clusters. For example, media literacy is related to methodology, content, medium, Spain, proposal, subject, and communication; these are the most common themes in this area of knowledge.

Figure 1. Vosviewer map co-occurrence of topics based on the descriptor Educommunication in Web of Science database.

Source: Authors using VOSviewer.

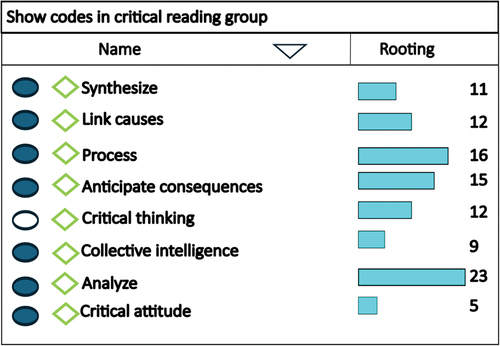

In the third stage, using ATLAS.ti V8 software for analysis, the researchers structured specific categories about the forms of application of educommunication in the analysed period. Forty-seven selected documents were processed according to the criterion of the areas of action of educommunication (See ). The results deepened curricular management, didactics and hypertext, among other essential topics. To present the results, the networks provided by the ATLAS.ti V8 software were plotted. This made it possible to connect the concepts related to the object of study in two main categories: Educommunication and Critical Reading.

By obtaining these elements, the bases of a pedagogical model are clearly identified, i.e. an articulation of nodes or nuclei such as pedagogy, curriculum, didactic strategies, but including elements that had not been knotted before such as reticularity, modularity, use of hypertext, among others, is obtained as a product. Also, according to the results shown in , some literature leads to the proposal of promoting a critical attitude articulated with the assumptions of Educommunication (root 5).

4. Results

The list of results contains two sections. The first one shows the elements that constitute the model and are the result of the application of the methodology (ad hoc corpus). These elements allowed the delimitation of the categories or variables of the work and are established, presented and defined based on the most relevant bibliography found in the period under review. The second section presents the elements of the heuristic proposal. This proposal is the contribution of the corpus to the realisation of the intervention model, which, together with the methodology used, is the main contribution of this article.

4.1. Elements of the corpus

Educommunication starts from the intersection between communication and education. However, there are trends in it, such as media literacy (which includes all studies on the development of media skills or competencies) and works that study the effects of educational processes on subjective development, including the development of autonomy, creativity and critical attitudes, among others (Bermejo-Berros, Citation2021). However, the current state of work does not integrate these trends. Whoever wants to integrate these poles must ‘combine the static diagnosis of media literacy with dynamic models that lead to learning and improvement of these structures informative contexts’ (p. 112). Thus, the exposition of the corpus elements is built on this integrative intention.

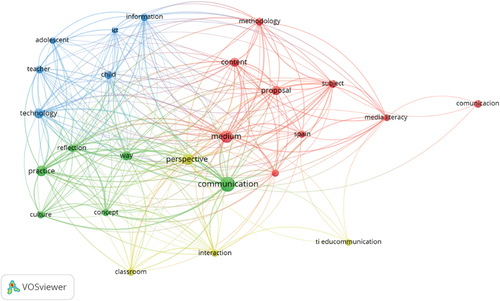

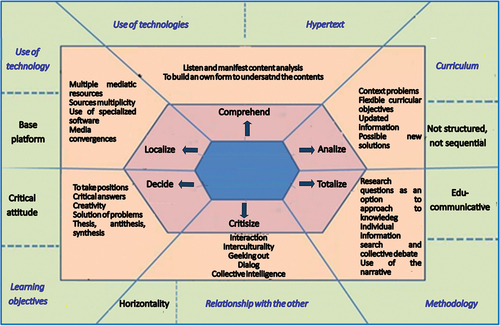

The elements to be integrated as a result of the application of the ad hoc corpus are the basis of a pedagogical model, which in itself is constituted around a particular relationship between the teacher, the knowledge, the students and the didactic resources to be used. In this sense, the Educommunication proposal implies the particularity of being based on communication elements such as technologies and media, but also, other elements such as hypertext, media literacy, e-learning, among other elements, that articulate to the characteristics of critical thinking, provide a set of concrete tools for its application by teachers at different levels of training, as shown in .

It is important to emphasise that, as the figure shows, the relationships between the elements are more complex and varied. The description given is not meant to be exhaustive, and it is certainly not meant to be reductive. It only shows the need to consider these elements in as comprehensive a way as possible. For example, thinking about a pedagogical model implies thinking about the interactions between teachers and students and about how to approach the content, that is, what the teaching methodology will be, what its objectives will be and how the subject to whom it is taught will be conceived (De Zubiría, Citation2010). It is based on this proposal that the elements were selected for the heuristic proposal. As a result of the ad hoc corpus, the categories shown in will be considered for the construction of the pedagogical model proposal.

The model proposal

As a contribution to the construction of the model, this article describes strategies that lead to the development of critical thinking regarding the use of Educommunication, which also implies going beyond the mere use of technologies. In summary, an outline of the elements that make up the proposal based on the ad hoc corpus is proposed, as shown in .

Figure 5. Educational intervention model for the development of critical attitude from Educommunication.

Source: Authors.

It is important to emphasise that shows the sequence of interrelated elements in the manner of a structure, i.e. for one to function, it depends on the others. To the extent that the processes dealt with by each of the stages are sequential, namely the localisation phase, which is the first stage of the process, it is absolutely necessary to be able to move on to the comprehension process, supported by media literacy and hypertext. To achieve this step and based on a curriculum with the characteristic of not being closed and sequential, it requires the application of Educommunication as a tool for debate, communication and collective construction. It aims at a horizontal relationship among the participants (colleagues and teachers) in order to finally reach the objectives of decision-making from a critical and well-founded position.

The superimposition of these elements makes it possible to reach the different edges of critical thinking (understanding, locating, analysing, criticising, deciding and totalising, as mentioned above). In turn, it supports the final achievement of learning based on cognitive and subjective development in general, but with the consideration of the context as one’s own and that of others.

Combining the foundations of the pedagogical model, the foundations of Educommunication and the characteristics of critical thinking, the authors’ work consisted of distinguishing the relationships between each of them in order to organise the categories.

The analysis of ATLAS.ti made it possible to find an initial direction for these links, but beyond that, the qualitative analysis of the authors’ proposals made it possible to reveal the relationships between some categories and others, for example, in the case of localisation and its close relationship with the use of the different platforms and media that communication offers, and in the case of comprehension the relevance of the use of hypertext and media literacy as tools that promote this process owing to their intrinsic characteristics, namely the need to reveal latent meanings housed in media texts.

In the case of the analysis, a problem-based, open-ended, non-sequential curricular model follows a problem-based approach. The use of narratives and various didactic strategies based on Educommunication as a methodology to achieve a totalisation of knowledge, among others, will be discussed in more detail below.

4.1.1. Use of technologies for localisation

From the ad hoc corpus we can see the importance of multiplying resources, multiple supports and specialised software, that is, the incorporation of ICT in all its rigour into educational processes. If we make the intersection with the characteristics of critical thinking, in this case specifically localisation, we can see that these resources, when used in a convergent way, promote the localisation of information, influencing the encounter with different perspectives of approaching a topic, a question or a research problem. The subject is driven to locate different sources, which implies evaluating them to determine their reliability and proximity to reality. Sequentially, locating and accessing information means accessing sources, discriminating which of them are not only reliable but also useful, and then discriminating the information they contain according to the same criteria. Cognitively, it involves reading, listening, watching etc. Learners can be trained by developing their autonomy and decision-making skills, putting them in control of their learning process, both through interdisciplinary activities and using digital resources, where they can develop communication skills.

Media literacy and hypertext, towards comprehension

The encounter through the ad hoc corpus of hypertext as a linguistic element makes it possible to articulate a tool that promotes comprehension by analysing the difference between the manifest and latent content of texts consulted in different media, examining the treatment of information. This involves a process of decoding, deconstruction and reconstruction, which in principle becomes a way of filtering information. It also promotes a deep analysis that leads to the construction of criteria for criticising and synthesising content and constructing one’s own ways of understanding. From this experience of deconstructing media content with prior judgement, students can develop the ability to read, interpret and evaluate new information. In addition, they become capable of dimensioning the impact that making their content can generate, with responsibility and bounded by interactions with others as a zone of proximal development.

Hypertext requires the user to take a break from sequential structures. Hypertext systems allow the construction and use of information structures that are free and associative. References or annotations can be made separately from the document, either through hyperlinks, notes or comments, among many other options. This breaks the sequentiality and opens the subject to other questions and topics, alienating the linear reading. This creates another hierarchical organisation and gives the added value of a new structure to what is being read, fostering the participants’ ability to symbolise and abstract.

The new structure is nodal and has certain kernels of ideas that are central to the process and are linked to others with images, text, hyperlinks etc. As a result, multiple open windows are generated that resize the content. This creates new kernels, jumping between nodes and windows through keywords, promoting content production and representational creativity. It also raises valid alternatives and inferences in non-sequential blocks, facilitating the formulation of solutions to contextual problems. At the same time, it increases the capacity for analysis by interpreting the different hypertext elements.

On the other hand, hypertexts are an excellent element for promoting collective work. They allow different authors to interact by exchanging ideas, arguments and goals, and by creating new nodes, among other experiences. What would be required in the application of the model is that those who do the curricular planning structure the contents with hypertexts and present them to the students so that they can carry out the different interpretation exercises.

Curriculum and methodology for analysing and summarising

On the other hand, when analysing Educommunication, one of the significant advantages of using Educommunication is that it teaches about contextual problems rather than concepts; this stimulates meaningful learning and the approach to its multidimensionality and complexity to the extent that multiple sources and content are approached. These are often constructed and updated from different epistemic and theoretical positions. In addition, the answers found in the context allow for a more effective appropriation of knowledge. The ways of approaching the objects of knowledge allow for curiosity as a planner of content, built around a curricular objective, but flexible. Using different sources, media and content, an interdisciplinary vision can be obtained to approach knowledge as a complex and integrating way to broaden the horizons of science and learning through the analysis and subsequent totalisation of content.

Online searches allow unlimited access to current, cutting-edge information to develop the ability to propose new solutions to emerging problems in the time and space of each participant. This gives students and teachers access to diverse information for learning and processing. The construction of networked knowledge, a product of dialogue, provides spaces to foster collective intelligence. This implies the use of tools that bring out the dimension of the critical subject, insofar as it requires the taking of subjective positions from argued perspectives. This promotes the acquisition of new mental schemata with skills for solving problems in an argued, effective way and with more complex capacities.

Pedagogically, the question is proposed as the spearhead of knowledge to replace the known and pre-established disciplinary boxes called subjects. The model promotes modularity and non-sequentiality, but above all it broadens the horizons of knowledge and its impact on the subject and culture. The search for individual information in digital media and then the focus on sharing (collaborative work) promotes the construction of a valid scientific background, confronted by a student, the media and others (teachers and peers). The latter allows the verification of sources and the discussion of the interpretations and arguments of each group member, generating new questions and approaches. This leads to decision-making and the selection of the best solutions to the questions or problems posed.

The use of alternatives of different didactic tools, including narratives, cinema or gamification as an essential element of learning, allows us to manage the impact on the different ways of thinking and learning of the students and a greater possibility of commitment and ability to connect with intrinsic motivation.

In the same sense, the evaluation focuses on the process and not on the product, since it evaluates the students’ dialogues, interactions and elaborations. This is done through multimedia and interaction with documents, videos, audio and other communication resources. This makes it possible to focus on the development of critical thinking skills instead of content assimilation. This is an acknowledgement that content has meaning only when it is placed in context. Context, in turn, comes from cultural history and is constantly changing. Consequently, valuing the process of analysis, deconstruction, construction and reconstruction implies focusing on the human development achieved through media use, which ultimately leads to criticality.

Relationship with the others and horizontality

Another dimension that appears to be prevalent in the corpus is the relationship with others (peers and teachers), where Educommunication offers the possibility of fostering processes such as collective knowledge construction or collective intelligence, and of promoting fluency and subjective interaction and integration. In essence, this means a more holistic approach to participants’ subjectivity. This favours networked learning and interculturality, as the media emphasise the otherness of the subjects, providing an ideal platform for the education of values and the promotion of coexistence.

This form of interaction encourages forms of participation that stimulate social action and promote integral education. This is because it implies the flow around academic and personal themes. This promotes the consolidation of social ties and the generation of ‘geeking out’, that is, the building of social ties around the construction of specialised knowledge. The experience of participation, driven by the interests of the new media, turns out to be the highest category of interactivity, because it refers to design and production and implies a high level of specialised knowledge.

The teacher goes from being the centre of knowledge to being another constructor as a promoter and mediator of the process, but not as its director. The direction of the work is the responsibility of all the participants and comes from the results of the media research. It generates a more horizontal relationship among them since knowledge does not belong to anyone. The most important thing is the analysis that everyone can make of the information, including the validity and reliability of the sources and the information. In addition, it is essential to analyse the differences and arguments that are presented during the synchronous meetings, once they have been processed by each participant. These meetings are fundamental for the construction of the social bond, the consensus, and the construction of collective knowledge.

From this perspective, the proposal of forms of interaction with the other emerges, including the possibility of interculturality, ‘geeking out’ (Ito et al., Citation2010) and a form of horizontal dialogue.

Learning objectives and critical attitude

The proposed learning objectives are focused on human development and not on the acquisition of knowledge; the curriculum, as already reviewed, is focused on the development of a series of strategies, such as questions, the search for information in different media, among other aspects, which allow on the one hand the contextualisation and on the other hand the application of knowledge constructed from a critical stance owing to the fact that the person can interact, dialogue and consequently make specialised knowledge more complex.

5. Conclusions and discussion

This article shares Bermejo-Berros’s (Citation2021) conceptualisation of Educommunication expressed as follows:

Educommunication studies can be situated at a bipolar dimension determined by the degree of intersection between Education and Communication. At one extreme are the works that focus on ‘media literacy’, namely, the development of media skills or competencies. On the other, we find studies concerned with disentangling the contribution of the media education process to personal development (autonomy, creativity, critical attitude, empowerment, social participation, values, ideology, and thinking).

Bermejo’s definition addresses two points of interest in this article, since on it converge the issue of media literacy and the development of thinking. However, this article aims to include other elements available in digital media beyond this thesis. Examples of these are media content and hypertext, but there are many others that this author does not consider. This article considers them necessary when considering a radical change in the pedagogical proposal. The latter becomes urgent, as stated by Pérez-Rodríguez et al. (Citation2019): ‘Education is in a period of redefinition and transformation, in line with an era characterized by significant technological development and profound social changes’ (p. 113).

On the other hand, and according to Pérez-Rodríguez et al. (Citation2019), the reason for this urgency has to do with the fact that ‘the media use of an entire generation highlights the gap between formal education and the everyday digital life of young people’ (p. 214). However, one of the major obstacles to the development of this type of model is the media literacy of teachers and students, even those born in the digital age and now entering university. In this regard, Sixto García and Melo (Citation2020) found that:

The Z is a generation that registers high rates of social media consumption. However, their digital competence is not as outstanding as one might expect due to the training deficiency they have acquired in previous educational levels caused, among other reasons, by the primary and secondary teachers’ low digital competence.

For all of the above, it is desirable to carry out projects that tend to consolidate an educational model that responds to technological developments and population characteristics, in order to achieve what García-Ceballos et al. (Citation2021) proposed: ‘Improving educommunication in Web 2.0 is the key to achieving certain sustainable development goals focused on educational quality’ (p. 1). These improvements are an opportunity to carry out research processes along the same path, allowing the development of an educational model from this perspective.

Finally, according to Fisher (Citation2001), it is possible to teach the tools of the critical attitude directly, in the form of skills that are transferable to different fields of intellectual action, without being linked to a disciplinary field or to a specific subject. Consequently, the strongest statement of the present work is that this transfer is not only possible, but strongly promoted by the staging of all the components described above, under an epistemic framework given by a model of educational intervention.

Taking all this into account, the present article is developed on the basis of two convictions: the first refers to the fact that the inclusion of the elements considered will allow students to perform an act of metacognition or reflection that will lead them to reconstruct their processes and, consequently, to systematise that knowledge that will help them to respond more effectively to the problems posed by the context. The second conviction leads to the presentation of the concrete pedagogical intervention model that articulates the elements involved and provides a solid epistemic support for its application.

The present study provided a model of educational intervention, elaborated from a corpus for the application of Educommunication as a methodology in the educational task. Its characteristics were related through seven dimensions: media literacy and communication, relationship with others (teacher-partners), hypertext, curricular aspects, use of technologies, methodology and learning objectives conceived from a collective construction. Each constitutive element was analysed to achieve this objective, which was selected through a previous exploration of scientific articles that included the Educommunication theme.

It was first schematised with VOSviewer and then with ATLAS.ti V8. In this sense, a significant limitation is that it has not yet been possible to carry out fieldwork that would allow the proposal to be put into practice to obtain quantitative data. In part, this difficulty is due to the public health conditions that the world was experiencing at the time of the research. Paradoxically, this situation is in addition to the connectivity problems, which are also widespread but predate the pandemic. However, this limitation also represents an opportunity to project these findings into future research that will allow us to obtain quantitative data to measure the impact of their application.

In any case, the exploration using ATLAS.ti V8 software made it possible to determine the rootedness of each topic. This made it easier to identify the gaps in the knowledge of the subject under study, as well as the weight of the different categories. These exercises allow the researchers to affirm that there is no reflection on a corpus that supports the work of Educommunication; previous academic production emphasises applied research. The closest to a corpus refers to Freire, who associated the work of Educommunication with dialogic pedagogy. However, according to Druetta (Citation2018), ‘the proposals originating in the work of Freire (Citation1996), with dialogue and communication as the axes of a transformative education, go in the opposite direction to the processes centered on technology’ (p. 161). This separates them from the aims of the present research.

The results of the ATLAS.ti V8 analysis also showed how deeply rooted the relationship is between Educommunication and topics such as ICT and its development. However, although media literacy is a relevant topic when higher education, teaching, and critical theory studies and the development of critical attitudes are added, the number of records is low. Only four articles were recorded, all of them in Web of Science and two of them also in Scopus. This shows that it is an open field for new contributions.

According to Behar (Citation2011), paradigmatic change is a term usually associated with ICT and e-learning, and it is coincidentally assumed to be an essential factor in introducing significant changes in the field of education. However, this assertion is accompanied by another statement: ‘The world has new axes in the concepts of time and space’ (p. 17), and they come along with technological advances. Unfortunately, paradigm shifts do not occur simply by incorporating new technologies into old-fashioned environments. These environments include models of thought, education, communication and human development.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Cirit Mateus De Oro

Cirit Mateus De Oro is a psychologist who completed postgraduate studies in clinical psychology at the Universidad de Leon and the Universidad Metropolitana, Colombia. She is a full professor at the Universidad Metropolitana in Barranquilla, Minciencias and a scholar at the Universidad del Norte, Colombia. She holds a PhD in Communication from the Universidad del Norte. Her professional interests focus on Educommunication and Gamification. She is the author and co-author of several journal articles and book chapters.

Daladier Jabba

Daladier Jabba has a PhD in Computer Science and Engineering, an MSc in Computer Engineering from the University of South Florida-Tampa and an MSc in Computer Science from UNAB, Colombia. Professor Jabba is a Full Professor of the Department of Systems Engineering at Universidad del Norte and a Research Group on Computer Networks and Software Engineering – GReCIS member. He has more than 60 papers published in different journals and 15 publications between books and book chapters. Professor Jabba works on projects with University–Industry interaction. His expertise is researching routing protocols for the Internet of Things (IoT). In recent years, he has been working on developing ICT platforms as support in the social and educational fields.

Ana María Erazo-Coronado

Ana María Erazo-Coronado is a dentist who has carried out postgraduate studies in endodontics at the Universidad Stadual of Campinas, Brazil. She is Full Professor at the Universidad Metropolitana in Barranquilla, Colombia. She earned her PhD in Communication from the Universidad del Norte. Her professional interest focuses on interpersonal health communication and risk and crisis communication. She is the author and co-author of several journal articles and book chapters.

Ignacio Aguaded

Ignacio Aguaded is a Full Professor of Education and Communication at the Universidad de Huelva. He has been Editor-in-Chief of Comunicar, a Media Education Research Journal, and President of Grupo Comunicar, a long-standing Media Literacy collective in Spain. He is also head of the Agora investigation team that forms part of the Andalusia Investigation Plan (HUM-648), Director of the International Master of Communication and Education (UNIA, UHU) and coordinator of the UHU Interuniversity Doctoral Program in Communication (US, UMA, UCA, UHU).

Rodrigo Campis Carrillo

Rodrigo Campis Carrillo is a psychologist who completed postgraduate studies in education at the Universidad del Atlántico, Colombia. He is a Full Professor at the Universidad Metropolitana de Barranquilla, Minciencias and a scholar of the Universidad del Norte, Colombia. He holds a PhD in Communication from the Universidad del Norte. His professional interests focus on Educommunication and Gamification. He is the author and co-author of several journal articles and book chapters.

References

- Aguaded, I. (2004). Hacia un currículum de edu-comunicación. Comunicar, Revista Científica de Comunicación y Educación, 22(43), 7–8. https://doi.org/10.3916/C43-2014-a1

- Aguaded, J. I. (2014). La investigación como estrategia de formación de los educomunicadores: Máster y Doctorado. Comunicar Revista Científica de Comunicación y Educación, 22(43), 07–08. https://doi.org/10.3916/C43-2014-a1

- Ahmad, K., Holmes-Higgin, P., & Abidi, S. S. R. (1994). A description of texts in a corpus: ‘virtual’ and ’real’ corpora. In EURALEX’94 (Proc. of the 6th EURALEX International Congress on Lexicography), Amsterdam The Netherlands (pp. 390–402).

- Ahuactzin Martínez, C. E., & Meyer Rodríguez, J. A. (2017). Publicidad electoral televisiva y persuasión en Puebla 2010. Una aproximación desde el Análisis Crítico del Discurso. Comunicación y sociedad, 29, 41–68. https://doi.org/10.32870/cys.v0i29.6281

- Alvarado, M. (2012). Lectura crítica de medios: una propuesta metodológica [Critical Reading of Media: A Methodological Proposal]. Comunicar, 20(39), 101–108. https://doi.org/10.3916/C39-2012-02-10

- Aparici, R., & García Matilla, A. (2016). ¿Qué ha ocurrido con la educación en comunicación en los últimos 35 años? Pensar el futuro. Espacios en blanco: Serie indagaciones, 26(1), 35–57.

- Aston, G., & Kübler, N. (2010). Using corpora in translation. In The Routledge handbook of corpus linguistics (pp. 501–515). Routledge.

- Austermühl, F. (2012). Using concept mapping and the web as corpus to develop terminological competence among translators and interpreters. Translation Spaces, 1(1), 54–80. https://doi.org/10.1075/ts.1.09aus

- Azar, A. S., & Tan, N. H. I. (2020). The application of ICT techs (mobile-assisted language learning, gamification, and virtual reality) in teaching English for secondary school students in Malaysia during COVID-19 pandemic. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 8(11C), 55–63. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2020.082307

- Barbas, Á. (2019). Educommunication for social change. In Book Citizen Media and Practice. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351247375-5

- Bedregal-Alpaca, N., Sharhorodska, O., Tupacyupanqui-Jaen, D., & Corneko-Aparicio, V. (2020). Problem based learning with information and communications technology support: An experience in the teaching-learning of matrix algebra. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science & Applications, 11(3). https://doi.org/10.14569/IJACSA.2020.0110315

- Behar, P. (2011). Constructing pedagogical models for e-learning. International Journal of Advanced Corporate Learning (iJAC), 4(3), 16–22. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijac.v4i3.1713

- Bermejo-Berros, J. (2021). The critical dialogical method in Educommunication to develop narrative thinking. Comunicar, 29(67), 111–121. https://doi.org/10.3916/C67-2021-09

- Bower, M., Dalgarno, B., Kennedy, G., Lee, M., & Kenney, J. (2015). Design and implementation factors in blended synchronous learning environments: Outcomes from a cross-case analysis. Computers & Education, 86, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.03.006

- Bozkurt, A., & Hilbelink, A. (2019). Paradigm shifts in global higher education and e-learning: An ecological perspective. eLearn, 2019(5). https://doi.org/10.1145/3329488.3329487

- Brooks, E., Dau, S., & Selander, S. (Eds.). (2021). Digital learning and collaborative practices: Lessons from inclusive and empowering participation with emerging technologies. Routledge.

- Castells, M. (2001). Internet y la Sociedad Red. Contrastes Revista cultural, 2006(43), 111–113. https://bit.ly/3lSqwsZ

- Causado, R., Santos, B., & Calderón, I. (2015). Desarrollo del pensamiento crítico en el área de Ciencias naturales en una escuela de secundaria. Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias, 4(2), 17–42. https://doi.org/10.15446/rev.fac.cienc.v4n2.51437

- Chen, S. (2018). Literacy and connected learning within a participatory culture: Linkages to collective intelligence efficacy and civic engagement. Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 27(3), 167–175. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-018-0375-

- De Oliveira Soares, I. (2009). Caminos de la educomunicación: Utopías, confrontaciones, reconocimientos. Nómadas, 30, 194–207.

- De Zubiría, J. (2010). Los Modelos Pedagógicos. Hacia una pedagogía dialogante. Editorial Magisterio.

- Dole, S., Bloom, L., & Kowalske, K. (2016). Transforming pedagogy: Changing perspectives from teacher-centered to learner-centered. Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.7771/1541-5015.1538

- Druetta, D. C. (2018). Comunicación, interacción y diálogo. Contribuciones desde América Latina a la Educomunicación [Bilingual edition: Spanish–English]. Perspectivas de la Comunicación, 11(2), 137–175. Educomunicadores: Máster y Doctorado. Comunicar, (43), 7-8. https://doi.org/10.3916/C43-2014-a1

- Falco, M. (2017). Reconsiderando las prácticas educativas: TICs en el proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje / RETHINKING EDUCATIONAL PRACTICES: ICTs IN THE TEACHING-LEARNING PROCESS. Tendencias Pedagógicas, 29(2017), 59–76. https://doi.org/10.15366/tp2017.29.002

- Figueroa, J. L. P., & Pérez, C. V. (2018). Collective intelligence: A new model of business management in the Big-Data Ecosystem. European Journal of Economics and Business Studies, 4(1), 201–212. https://doi.org/10.26417/ejes.v10i1.p208-219

- Fisher, A. (2001). Critical thinking: An introduction. Cambridge University Press.

- Freire, P. (1967). Educacao como practica do libertade. Paz e Terra.

- Freire, P. (1996). Siglo XXI (Ed.), Política y educación.

- García-Ceballos, S., Rivero, P., Molina-Puche, S., & Navarro-Neri, I. (2021). Educommunication and archaeological heritage in Italy and Spain: An analysis of institutions’ use of Twitter, Sustainability, and citizen participation. Sustainability, 13(4), 1602. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041602

- Ito, M., Baumer, S., Horst, H., Bittanti, M., Boyd, D., Cody, R., Herr-Stephenson, B., Lange, P., Mahendran, D., Martinez, K., Pascoe, C., Perkel, D., & Robinson, L. S. C. T. L. (2010). Living and learning with new media. MIT Press.

- Jenkins, H. (2018). Fandom, negotiation, and participatory culture. A companion to media fandom and fan studies. Wiley.

- Kaplún, M. (1992). A la educación por la comunicación: la práctica de la comunicación educativa. CIESPAL.

- Landow, G. (2009). Hipertexto 3.0. Teoría crítica y nuevos medios en la era de la globalización. Paidós Ibérica.

- Lévy, P. (2004). Inteligencia colectiva. Por una antropología del ciberespacio. Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Qualitative Research in Education, 110. https://bit.ly/37T5vtf

- López Mateo, C., & Olmo Cazevieille, F. (2015). Recopilación de textos para la elaboración de un corpus especializado en el ámbito de la bioquímica: aspectos teóricos y metodológicos. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 198, 300–308. http://dx.doi.org/10.20420/rlfe.2018.234

- Narváez, A. (2021). Educommunication and media literacy: Technology or culture? Training or Education? Pedagogía y Saberes, 55. https://doi.org/10.17227/pys.num55-12245

- Parra, G. (2000). Bases epistemológicas de la educomunicación (Definiciones y perspectiva de su desarrollo). Ediciones Abya Yala.

- Pastor, G. C. (2001). Compilación de un corpus ad hoc para la enseñanza de la traducción inversa especializada. Revista de traductología, 5, 155–184. https://doi.org/10.24310/TRANS.2001.v0i5.2916

- Pastor, G. C. (2002). Traducir con corpus: De la teoría a la práctica. Texto, terminología y traducción, 5. https://doi.org/10.24310/TRANS.2001.v0i5.2916

- Pérez-Rodríguez, A., Sánchez-López, I., & Fandos-Igado, M. (2019). Com-educational platforms: Creativity and community for learning. Journal of New Approaches in Educational Research, 8(2), 214–226. https://doi.org/10.7821/naer.2019.7.437

- Piñuel, J. (2002). Epistemología, metodología y técnicas del análisis de contenido. Epistemología, metodología y técnicas del análisis de contenido. Sociolinguistic Studies, 3(1), 1–42. https://doi.org/10.1558/sols.v3i1.1

- Rodríguez, M. (2015). Del códice al hipertexto: los cambios en la lectura y la transmisión de conocimiento. Argentina Investiga. https://bit.ly/36rH7fT

- Romero-Rodríguez, L. M., Contreras-Pulido, P., & Y Pérez-Rodríguez, M. A. (2019). Media competencies of university professors and students. Comparison of levels in Spain, Portugal, Brazil and Venezuela/Las competencias mediáticas de profesores y estudiantes universitarios. Comparación de niveles en España, Portugal, Brasil y Venezuela. Cultura y Educación, 31(2), 326–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/11356405.2019.1597564

- Rossi, G. H. (2001). Hipertextos en educación. In Informática Educativa: Proyecto SIIE (pp. 235–245).

- Sánchez-Gijón, P. (2009). Developing documentation skills to build do-it-yourself corpora in the specialised translation course. Corpus use and translating. Corpus use for learning to translate and learning corpus use to translate (pp. 109–127). Benjamins Translation Library. https://doi.org/10.1075/btl.82.08san

- Sánchez Peña, C. F., & Riaño, J. G. (2019). Estrategia de Educomunicación como metodología de innovación educativa en el programa de Comunicación Social de la Universidad Cooperativa de Colombia. Editorial UCC.

- Scolari, C. (2008). Hipermediaciones: Elementos para una teoría de la comunicación interactiva. Editorial Gedisa.

- Scolari, C. (2015). Ecología de los medios. Entornos, evoluciones e interpretaciones. In A. Beeby, P. Rodríguez-Inés, & P. Sánchez-Gijón (Eds.), Gedisa.

- Scolari, C. A. (2012). Comunicación digital. Recuerdos del futuro. El profesional de la información, 21(4), 337–340. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2012.jul.01

- Sixto García, J., & Melo, A. D. (2020). Self-destructive content in university teaching: New challenge in the digital competence of educators. Communication & Society, 33(3), 187–199. https://doi.org/10.15581/003.33.3.187-199

- Vixtha-Vázquez, F. (2017). Interactividad y Multimedialidad: elementos que la Hipermediación aporta a la Comunicación Educativa. Razón y Palabra, 21(3_98), 206–220. https://bit.ly/2PccmG5t