Abstract

Objectives

This study concerns culturally Deaf signers in the UK who use hearing aids and (i) explores motivations for hearing aid use (ii) identifies barriers and facilitators to accessing NHS hearing aid services, (iii) examines cultural competency of hearing aid clinics and (iv) identifies factors influencing effective adult hearing aid service provision.

Design

Online survey in British Sign Language and English that was informed by Deaf service users.

Study sample

75 Deaf adult BSL users who wear hearing aids and use NHS hearing aid clinics.

Results

No specific reason emerged as outstandingly important for hearing aid use; however, assisting with lipreading (57%) and listening to music (52%) were rated as very/extremely important. Access issues reported were contacting clinics, poor communication with staff and lack of Deaf awareness. To be an effective and culturally competent hearing aid clinic for Deaf signers, a good understanding of Deaf culture and language was most rated as important (87%).

Conclusion

The study is the first that explores hearing aid use and experiences of accessing hearing aid clinics from Deaf signers’ perspectives. Enhancements to clinical practice are required to consider culturally Deaf people’s motivations for hearing aid use and make services more BSL-friendly.

1. Introduction

Each year approximately 350,000 (The British Irish Hearing Instrument Manufacturers Association Citation2019) hearing aids are prescribed and fitted to adults new to hearing aid wearing by the UK's National Health Service (NHS). The NHS is free at the point of delivery and includes the provision (and maintenance) of hearing aids. Typical users who access NHS hearing aid services are adults who use spoken language and older people with age-related hearing loss (NHS England, Citation2016). However, culturally Deaf adults whose first or preferred language is a signed language such as British Sign Language (BSL) have access to these services, and some are regular hearing aid users. There are approximately 87,000 Deaf BSL users in the UK (British Deaf Association (BDA) Citation2018). The number using hearing aids or cochlear implants is unknown (Dammeyer, Lehane, and Marschark Citation2017) but there is some evidence that this number may be increasing (Harris and Paludneviciene Citation2011; Hulme, Young, and Munro Citation2021; Mitchiner Citation2015). There is little research in the UK or internationally on Deaf signers as users of hearing aid services in terms of their motivations for hearing aid use or the cultural competency of the audiology services who seek to meet their needs and preferences. There is also a dearth of professional guidance for audiology professionals on working with and providing services to adults who are sign language users. This population with BSL users are often excluded from guidance and training on culturally competent service provision (see for example) (Mental Health Reform Citation2021) through lack of recognition of them as constituting a cultural-linguistic group in the same way, as for example, Spanish speakers in the US would be (Ullarui Citation2022). Cultural competence in this sense is defined as a set of values, attitudes and practices within a system, organisation, or individuals to provide effective quality care to patients who are diverse in culture and language. For example, staff’s understanding of Deaf language and culture, and evidence of person-centred communication.

There is extensive research on culturally Deaf people’s access to health. The overall conclusion is that this population experience poorer physical and mental health outcomes because of lack of communication with health professionals in their preferred (signed) language, and lack of accessible patient information in a signed language. Both underdiagnosis and misdiagnosis may result (Emond et al. Citation2015; Kuenburg, Fellinger, and Fellinger Citation2016; Young et al. Citation2017). Additionally, inadequate access to health literacy leads to poor self-care (Pollard and Barnett Citation2009; Hommes et al. Citation2018; Brown Citation2018). There is little mention of hearing aid services within generic health research on culturally Deaf people.

Butler and Martin (Butler and Martin Citation1987) surveyed 32 Deaf participants who are American Sign Language (ASL) users about audiology services. The topics covered were communication methods, practices in audiology, deafness, hearing and audiologists’ relationships with the Deaf community. The study established that the Deaf community was aware of audiology services and rated effective communication with professionals highly, although there is little data on American Sign Language (ASL) users’ reasons for hearing aid use. Moreover, the results are based on a study that is 34 years old and it is unknown if the findings are still relevant and generalisable to other countries. Cue et al. (Cue et al. Citation2019) analysed 15 deaf adults’ (with Deaf or hearing parents) narratives on what it means to be D/deaf. Only two of the 15 participants provided their narrative in ASL with the rest in written English. Hearing technology was one of the six main themes identified. Participants mentioned the role of hearing aids in soothing a person to sleep, providing comfort and communicating with friends and family. Whether the statements were from participants who were sign language users is not clearly identified.

There is a growing body of literature that recognises the importance of culturally responsive services. There are references to audiology services with specific communities such as the Inuit (Billard Citation2014), Aboriginal and Torres Strait (Children’s Health Queensland Hospital and Health Services Citation2017; Children’s Health Queensland Hospital and Health Services Citation2017b), Spanish Hispanics (Reel et al. Citation2015) and Korean American older adults (Choi et al. Citation2019). Examples of what makes these services culturally responsive include employing health link workers from specific communities and working in partnership with communities to develop linguistic and culturally appropriate assessments and resources. However, within these studies, there is no evidence from Deaf sign language users. Conversely, Cottrell et al. (Cottrell et al. Citation2021) recently surveyed audiologists’ cultural competency by assessing their exposure, knowledge and attitudes when working with patients who are culturally Deaf ASL users. Based on 111 respondents, they reported that audiologists’ competence is limited because of the lack of exposure to Deaf ASL signers. Their survey is based on the perspectives of audiologists, not Deaf signers. However, they did acknowledge that future research is required from Deaf signers’ perspectives on audiologist’s cultural competence.

The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association’s (ASHA) position statement relating to sign language users (ASHA Citation2019) recommends that ASL be accepted as a language in its own right. ASHA also has guidelines linked to generic cultural competence and a series of checklists that address personal reflection, service delivery, and policies and procedures. Despite the position statement, there is no evidence of sign language filtering into their best practice guidelines as yet. Furthermore, an extensive search shows no other audiology organisations guidelines refer to the use of sign language within the profession.

A conspicuous absence in the literature is evidence generated from the perspective of Deaf sign language users themselves about their motivations for and experiences of hearing aid use and their perspective on hearing aid service provision. The aim of this study was to explore Deaf BSL users’ experiences of NHS adult hearing aid services. Results are reported from a survey carried out in BSL and English with 75 culturally Deaf adults who use BSL as their first, or preferred language, and who regularly use hearing aids and access NHS hearing aid services. The first author is herself a culturally Deaf person and a hearing aid user. The primary research questions were from the perspective of Deaf signers:

How do Deaf signers characterise the purpose and use of their hearing aids?

To what extent are hearing aid services accessible?

Is there evidence of cultural competence in service provision? If so, of what kind?

What enables effective service provision?

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

The target population were culturally Deaf BSL users, 18 years or over, who were patients of NHS audiology services in England and who were current hearing aid users. Recruitment was mainly through snowballing via online social media (Twitter and Facebook), personal networks and Deaf organisations’ website. Given that the lead researcher is a culturally Deaf BSL user and hearing aid user, her own extensive Deaf community networks facilitated recruitment.

2.2. Procedure

Data were collected online by means of a researcher-designed survey. Its content was informed by a preliminary qualitative interview study of eight Deaf BSL users who were hearing aid users (‘expert informants’) the findings of which have been published (Hulme, Young & Munro, Citation2021) and the Consumer Quality Index (CQI), which is a patient experience survey (Delnoij, Rademakers, and Groenewegen Citation2010) adapted for audiology services (Hendriks, Dahlhaus-Booij, and Plass Citation2017). The researcher (first author) combined data from the two sources to develop a survey that used a descriptive 42 questions format that could increase to 50 depending on responses to specific questions. The eight expert informants from the qualitative interviews (Hulme, Young, and Munro Citation2021) were involved in reviewing the survey questions to check for any potential ambiguity in the BSL version and they also piloted the survey to check clarity of understanding of the questions. Refer to Appendix 1 (Supplementary Material) for survey questions. It is important to note that the survey questions use a mixture of pronouns as they are written in a way for ease of BSL translation (Rogers et al. Citation2016). The survey consisted of six sections:

About you and your hearing aids, e.g. duration of use of aids; demographic characteristics, hearing aid use.

Your hearing aid clinic, e.g. geographic region, services provided and waiting room experience

Arranging appointments, e.g. methods of contact provided by clinic, interpreter booking and communicating with reception staff.

Attending appointments, e.g. service desk/drop-in system and how the Deaf person communicate in appointments,

Conduct and expertise of staff, e.g. staff understanding of Deaf culture, language and Deaf community and staff communication abilities

Patient satisfaction, e.g. rate clinics Deaf awareness levels, Friends and Family test and suggestions on what would make a clinic Deaf-friendly.

Since the survey was aimed at Deaf sign language users, all questions were made available in BSL and participants had the choice of completing the survey in BSL, English or, both. REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture), a secure web-based application for survey data capture, was the choice of software as it provides a multilingual hook permitting the presentation of a survey in languages other than English (Mattingly, Buckner, and Pena Citation2019). However, a novel modification of this web-based application was created by Young et al. (Young et al. Citation2021) that permits the possibility of switching between different languages on a question-by-question basis, rather than the presentation of a questionnaire in two separate languages.

Before accessing the survey, participants were screened for eligibility, watch/read the Participant Information Sheet (PIS) and directed to the consent page. The survey took approximately 30–60 minutes to complete. Prior to the start of the survey, participants had the option of registering their email address for a code that allowed them to return and complete the survey at a later stage. Most closed questions required a response to select a single answer from a list of response options and where possible, textual responses could also be provided. Ideally, participants should have been allowed to respond in BSL; however, this was not possible with the platform because their responses would have had to be encrypted at the point of upload, not at the point of receipt, to conform with the University’s data processing regulations. The number of open questions was small and had to be answered in English which is a potential barrier for BSL users. The forced response option in the survey was switched off to allow participants to skip questions if they did not want to answer them.

The study received ethical approval from a University Research Ethics Committee. Responses were collected between December 2019 and June 2020. The survey was paused during March and April 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

2.3. Data analysis

SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) Version 25 and MS Excel supported the analysis. The majority of the outputs were univariate analyses using binary, nominal and ordinal data to generate descriptive and frequency statistics. Furthermore, statistical analyses were not carried out because the small sample sizes. Thematic analysis was used to analyse the open-ended responses.

3. Results

3.1. The sample

shows that most of the 75 participants were White British, female, under 50 years of age, severely or profoundly Deaf, diagnosed under the age of 3 years and received hearing aids in early childhood. All participants identified with the Deaf community and were strong BSL users. Full information is available in .

Table 1. Demographics characteristics of the N = 75 survey respondents in raw number (n) and percentage of overall respondents (%).

3.2. Deaf signers’ reasons for using hearing aids

The first objective was to explore Deaf signers’ relationships with their hearing aids.

3.2.1. Frequency of hearing aid use

Forty-three (57%) were bilateral hearing aid users, and 42.7% unilateral. Most report wearing their hearing aids daily (85.3%). 58 of these daily hearing aid wearers said they did so at least 75% with the other 6 reporting less than 50% of the time and nobody selected the ‘I prefer not to say’ option.

The vast majority had worn hearing aids continually since childhood although ten (13%) reported they stopped wearing hearing aids for an extended period of time (median 6 years) before deciding to recommence. Taking a break from hearing aid use coincided with school leaving, and a perceived lack of benefit from their use whether in terms of speech audibility or utility if they were using sign language. Reasons given for return to hearing aid use included being aware that the technology had improved or for a secondary audiological reason such as remediation of tinnitus and balance issues. Environmental and contextual issues were also relevant such as to assist in communication with hearing children and to make study or work easier to manage.

3.2.2. Deaf signers’ motivations for hearing aid use

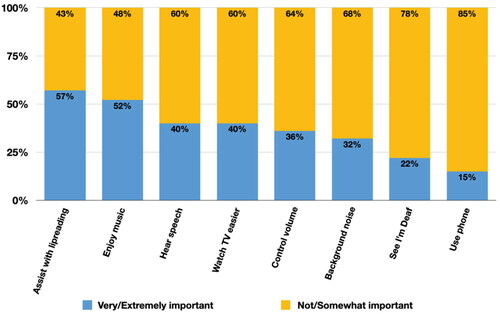

Participants were asked about why they used their hearing aids and asked to weight potential motivations by degree of importance on a Likert scale of 1 (not important) − 4 (extremely important). For analysis purposes, these categories were combined into a binary classification of (i) not/somewhat important and (ii) very/extremely important rating (). The top motivations rated as very/extremely important for using hearing aids were to ‘assist with lipreading’ (57%) and ‘to enjoy music’ (52%). Hearing speech, background noise, watching TV and managing loudness/volume were all rated as very/extremely important by only 40% or fewer of the sample with being able to use the telephone rated as very/extremely important by only 15% of the participants. Also, the ‘I prefer not to say’ option was not selected by any of the participants. The frequency of motivations for hearing aid use appears to be similar across all the age groups.

3.2.3. Understanding hearing aids

Audiograms are the charts used to summarise pure-tone hearing tests and of the 55% who discussed their results with their audiologists, only half said they understood them. However, only around one third of audiologists (35%) were said to have discussed participants’ audiograms with them but nearly all of the participants (98%) report they wished their audiologist had done so. None of the participants selected the ‘I prefer not to say’ option.

Hearing aid settings are based on audiometric data, and aids come with many programmes permitting greater emphasis or boosting of sound and speech intelligibility by context and according to desired functions. Nearly three-fifths of participants (59%) reported their audiologist had never discussed with them what they might want from their hearing aids. Over half (55%) said they were unaware of the hearing aids many programmes and features and would like to know more about these with 25% acknowledging that they were aware of some functions and would like to learn more about the various possibilities. Furthermore, the ‘I prefer not to say’ option was not selected.

79% said that their audiologist does provide space to ask questions in general appointments, but this was not necessarily helpful given that 29% reported they could not understand their audiologist and vice versa. However, having an interpreter present enabled 15% of participants to ask questions but for another 15% the opportunity to ask questions was not offered by their audiologist and the ‘I prefer not to say’ option was not selected by any of the participants.

3.3. Accessibility of hearing aid clinics

The second objective was to explore Deaf signers’ barriers and facilitators to accessing hearing aid clinics in terms of contacting clinics to arrange appointments and when waiting for their appointments.

3.3.1. The first contact

For many Deaf people, it is preferable to make the first contact with a hearing aid clinic through sign language. Only 4% participants say they were able to contact their clinic via VRS (Video Relay Service) using their first language, BSL. Email access was a possibility provided by clinics for only half of the participants (47%). Additionally, text-based services were not a common provision for contact, with only 16% reporting their clinic allows texting and 20% reporting that their audiology clinic rings them via NGT/Relay UK (where a Deaf person can make or receive calls on their minicom/tablet). Hearing aid clinics’ most usual form of contact is the telephone (71%) followed by a letter (61%). None of the participants selected the ‘I prefer not to say’ option.

3.3.2. The waiting room experience

Deaf people are visual beings, preferring optimal lines of sight in any given context. In a hearing aid clinic, this would be sitting near and facing the reception, and this was the case for three-fifths of the sample (72%). Others were only comfortable sitting elsewhere if someone else was with them or they felt confident that they would be fetched by clinical staff, rather than it being assumed they would hear their name if it were called. Only one participant reported any experience of the availability of BSL resources in a hearing aid clinic. 99% reported that there were no information videos in BSL; very few (8%) clinics had BSL posters and 95% reported no visual alerting devices (e.g. displaying the name of patient). Also, the “I prefer not to say” option was not selected by any of the participants.

3.3.3. Communicating in BSL

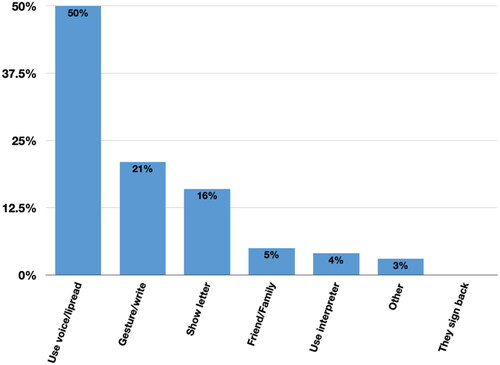

No participant reported reception staff using sign language to communicate. Instead, as highlighted in , the onus appears to be on the Deaf signer to communicate where they use their voice and lipread (50%) and gesture or write (21%). Some (16%) prefer not to attempt to communicate at all, preferring instead to show the appointment letter to the receptionist. Furthermore, only 9% report that they use someone else to communicate for them, for example, an interpreter (4%) or use their friends/family (5%). Moreover, no participants selected the “I prefer not to say” option.

A most striking result is that, out of the 75 participants, most do not request interpreters for either drop-in clinics or battery exchanges at the service desks (89%) or review/test appointments with an audiologist (72%). Only 13% always book an interpreter for their review/test appointments. 40% of the participants, said if they wanted to use interpreters, they would not be able to anyway as their clinic does not provide them. Additionally, nearly one third (31%) said they do not know if their clinic provides interpreters. Five participants said that their audiologist could sign directly with them. Four of them had basic signing skills and one was at intermediate level. Furthermore, none of the participants selected the “I prefer not to say” option in this section.

3.4. Cultural competency in hearing aid clinics

The third objective was to examine the cultural competence of hearing aid clinics in meeting the needs of Deaf signers.

3.4.1. Audiologists understanding of deaf community (language, culture and awareness)

Participants in the survey were asked whether their audiologist understood Deaf culture, Deaf awareness, Deaf community, and sign language. Only 3% reported that their audiologist had a “good” understanding, followed by 25% who said “somewhat”. However, the majority, 68%, reported that their audiologist did not understand their culture and language well and none of the participants opted for the “I prefer not to say”.

Participants’ (n = 44) further explanations for their responses were organised into three main themes: (a) understanding the deaf signing community (n = 23), (b) one size fits all approach (n = 15), and (c) cultural adaptation (n = 6).

3.4.1.1. Understanding the deaf signing community

Participants explained that whilst their audiologist understood their deafness from a medical perspective, they did not know or show understanding of BSL as a language and culture. Participants explained that they did not feel valued, respected, or appreciated as a person with a culture. Also, there was little acknowledgement that their lived experience as a hearing aid wearer might be different than that of deaf people who were not signers or part of the Deaf community. Few audiologists were observed to make good eye contact and use clear speech. If they would ensure that interpreters were booked, then participants who commented said they felt more respected and acknowledged.

3.4.1.2. One size fits all approach

Participants emphasised that they felt they had to fit into usual practices, rather than those practices being adapted to their needs. For example, the common habit of just calling out people’s names in a waiting room assuming that they can hear. Participants felt they were treated in the same way as, for example, older patients with hearing loss, with little attempt to understand the meaning or experience of hearing aids from their point of view. The extra time required to communicate effectively was frustrating for some staff in some participants’ experiences.

3.4.1.3. Cultural adaptation

The lack of visual displays, no access through text and email, little use of text relay services, and the invisibility of BSL in waiting areas all created an immediate impression of no cultural adaptation. Where some audiologists were preferred because they displayed some deaf awareness and cultural adaptation, the problem was these were not prioritised in the booking system.

3.5. Enablers of effective service provision

The fourth objective was to identify factors that enable effective service provision. For example, what facilitates high patient satisfaction and what would make a hearing aid clinic effective for BSL signers.

3.5.1. Patient satisfaction

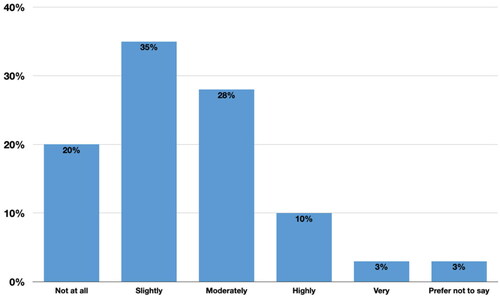

Satisfaction levels (see ) were rated by degree of satisfaction from 1 not at all satisfied to 5 very satisfied. Eighty-three percent were either not at all satisfied, or only slightly or moderately satisfied (see ) and 3% said they preferred not to say. Only 9 were highly or very highly satisfied.

Reasons for selecting moderately satisfied were that staff are very friendly; they display a good attitude, have patience with communication, and provide interpreters. However, for those who selected that they were highly/very highly satisfied (13%), reasons were that their needs were fully met, and staff portray patient-centred care and patient- centred communication by asking them what programmes they would personally like in their hearing aids. Staff being professional, friendly, helpful, and speaking clearly are also factors for high satisfaction experiences.

3.5.2. BSL accommodations

Accommodation is used here to mean providing adjustments suited to sign language users to remove barriers to access and communication. Participants were asked to pick three areas from a list of 6 accommodations that they would ideally like to have at their hearing aid clinic: (The British Irish Hearing Instrument Manufacturers Association, Citation2019) to be able to contact via email, text messaging, VRS; (NHS England, Citation2016) to have hearing aid information in BSL; (British Deaf Association (BDA) Citation2018) for audiologists and staff to have good understanding of Deaf awareness, culture and the Deaf community; (Dammeyer, Lehane, and Marschark Citation2017) for all staff to be able to sign; (Harris and Paludneviciene Citation2011) for the waiting room to be Deaf friendly (visual board, appropriate seating) and (Hulme, Young, and Munro Citation2021) other.

The overwhelming priority choice (87%) for participants is that they would like their audiologist to have a good understanding of their culture, language and community. Participants rated this a higher priority than having staff who can sign (53%). Next, having a Deaf friendly waiting room where patients can relax and not worry about being recalled was a top-three choice for 55% of the participants equal with having visual and textual contact with clinics such as VRS, email and text. Nearly one quarter (25%) said that they would like their clinic to provide information in BSL and none opted for the “I prefer not to say” option.

4. Discussion

The present study is the first that identifies and explores hearing aid use and experiences of accessing hearing aid clinics amongst Deaf adults who use sign language and wear hearing aids. The study aims were to elicit experiences of Deaf signers who use hearing aids to explore their relationships with hearing aids, investigate their barriers and facilitators to accessing hearing aid clinics, and examine how their clinics meet their needs as well as to identify exemplars of what makes an effective hearing aid clinic for Deaf signers.

4.1. Motivations for hearing aid use

Measures of hearing aid benefit typically centre around audibility and speech intelligibility (Hulme, Young, and Munro Citation2021; Ferguson et al. Citation2017). Why sign language users wear hearing aids is, therefore, an interesting question given their preference for a visual language (BSL). No specific reason emerged as outstandingly important for participants with only “assisting with lipreading” and “enjoying music” being rated as very/extremely important by just over half of participants. Assisting with lipreading, is still, of course, a form of communication benefit but it is a receptive form of communication benefit, not a productive one. No participant said they were using hearing aids to help them speak better. The importance of enjoying music for around half of the participants might seem unexpected for those from a predominantly visual culture (Friedner Citation2016). While they may not be able to experience music the same way as hearing people, they still benefit from music but perceive it differently, for example, hearing the rhythm and bass (Holmes Citation2017). Common motivations for hearing aid use in the typical population of hearing aid users, were not highly rated by this population of BSL users in this study. The lack of importance given to other commonly prioritised motivations is perhaps not surprising such as being able to use the telephone better, watch television more easily, or to enable others to recognise that a person is Deaf when their deafness is invisible. These three features all emphasise hearing and sound as normative and fit with a phonocentric (Derrida Citation1976) orientation to the world. From a Deaf cultural perspective sound and speech are not just of lesser importance but rather not a fundamental orientation for being in the world (Philosophy Documentation Center 2008).

This perspective might help audiologists to better orientate their interactions with Deaf patients away from “enforcing normalcy” (Davis Citation1995) to one in which they seek to meet Deaf patients’ priorities for listening and hearing in alignment with their cultural values alongside their primary (signed) language. However, as other results from this survey demonstrate, there are barriers to such alignment, not least of which is the lack of meaningful engagement between audiologists and patients. This is obviously not just about the lack of the means of communication through failure to provide interpreters and accessible communication with clinics. It is also about failure to meaningfully engage with patients. The high percentage of participants who report that they have never had a conversation with audiologists about the potential features, functions, and programmes of their hearing aids and how these might assist their motivations for wearing hearing aids is very evident from this study.

4.2. Accessing and using hearing aid clinics

The Accessible Information Standard (NHS England Citation2016) is a legal standard for all NHS and social care organisations to adhere to when meeting the information and communication needs of their patients and service users. For BSL users in this study, the vast majority experienced a failure to meet this standard. Such experience is not unique to audiology services in England. A recent report by SignHealth (SignHealth Citation2022) shows how much health/social care providers rely mainly on phone systems for contact and strongly recommended email/text and VRS provisions should be available. Patients’ low expectations of and poor experience of interpreter provision in this study also contravenes the provisions of the Equality Act Citation2010 (The Equality Act, Citation2010), the Public Sector Equality Duty 2011 (Public Sector Equality Duty, Citation2011) and is at odds with the NHS’s own commitment within the NHS constitution 2012 to “providing high quality, equitable, effective healthcare services that are responsive to all patients’ needs.” (NHS England/Primary Care Commissioning Citation2018). It is the responsibility of health providers to ensure interpreting is in place for clinical consultation. The fact that so few participants (31%) knew if it were possible to have an interpreter is, of itself, testimony to the failure to ensure this legal provision, let alone how few used an interpreter for clinical consultation with their audiologist (13%). The non-use of interpreters for quick interactions such as picking up batteries, hearing aid repairs is perhaps understandable given the instant nature of the interaction and the lack of feasibility of booking interpreters at short notice. Yet in other countries short interactions through a remote interpreter in public services is feasible precisely because such systems have been set up to enable this need to be met (Kushalnagar, Paludneviciene, and Kushalnagar Citation2019). However, this instant access is not to be seen as a replacement for face-to-face interpreting but as a complementary addition (Kushalnagar, Paludneviciene, and Kushalnagar Citation2019).

Such seemingly practical issues of linguistic access are of far greater importance because patient access and engagement are essential for optimal health outcomes and inadequate provision from the first point of contact could affect the person’s health outcome, quality of care and patient satisfaction (Emond et al. Citation2015; Jama et al. Citation2020). Accessible engagement encompasses accessible information (in BSL), interpreted interactions with clinicians, self-management of health conditions facilitated through culturally and linguistically adjusted programmes, as well as ensuring adequate linguistic provision to support patient choice (of treatment for example). Health inequalities in these respects have been found in numerous sign language populations (Hulme, Young, and Munro Citation2021; Kuenburg, Fellinger, and Fellinger Citation2016; Pollard and Barnett Citation2009; Brown Citation2018; Steinberg et al. Citation2006; Cross et al. Citation1989). This is, however, the first instance that we are aware of when such barriers and effects have been noted in respect to audiology clinics from the perspectives of Deaf signers.

4.3. Cultural competency

Cultural competency (Balint Citation1969) and patient-centred care (P-CC) (Ladd Citation2003) are both main components when providing healthcare services. However, most of the participants in this study did not have a positive experience of cultural competency or P-CC. This manifested in different ways, ranging from lack of linguistic accommodations to experiencing a lack of respect. Patients did not blame audiologists for not having BSL competency nor did they complain that there were no Deaf clinicians. However, they did raise fundamental concerns that as culturally and linguistically distinct patients, they were being fitted into usual ways of working. In this sense, it is important to acknowledge that the lack of understanding of Deaf awareness, language and culture (that 68% of the participants report about their audiologist in this study) is distinct from deaf awareness in general. Deaf awareness commonly refers to how deaf people communicate, terminology use, understanding the need to speak slowly and clearly and knowing how to book BSL interpreters. However, this level of awareness is not sufficient to understand the cultural-linguistic needs of the signing Deaf community. These findings are consistent with those of Cottrell et al., (Cottrell et al. Citation2021) who identified that audiologists who work with ASL patients require training on how to use interpreters and learn ASL.

This group of experienced hearing aid users felt that their audiologist only understood them from a medical perspective (Ladd Citation2003) and there was too much focus on technical aspects (Meyer et al. Citation2017; Watermeyer, Kanji, and Sarvan Citation2017). Patient-centred care is about interacting with a patient and encompassing their whole being. Within audiology, many findings suggest audiologists need to improve their patient interaction (Watermeyer, Kanji, and Sarvan Citation2017; Parmar et al. Citation2021) and it is no different for Deaf signers in this current research. However, it adds a layer of complexity because of the language barriers and lack of understanding of Deaf signers’ culture. Examples of lack of P-CC is not treating them any differently from their usual patients (elderly patients with age-related loss or hearing people in general) and poor assessment experiences as participants experienced insufficient questioning about their intended use of hearing aids.

4.4. Exemplars of how to make a hearing aid clinic effective for deaf signers

Specific training on the cultural-linguistic needs of Deaf signers need to include topics about family communication, the education they receive (Marschark and Knoors Citation2015), the inequalities they face (Fellinger, Holzinger, and Pollard Citation2012; Rogers et al. Citation2013; Young, Napier, and Oram Citation2019), understanding BSL as a language (Sutton-Spence and Woll Citation1999), learning specific audiology signs (Panning, Lee, and Misurelli Citation2021) and most importantly why and how they use their hearing aids as Deaf signers (Hulme, Young, and Munro Citation2021). By receiving this type of training, audiologists would know how to adjust themselves and their services to meet the needs of Deaf signers and ask culturally appropriate questions. Furthermore, this would contribute towards higher patient satisfaction from Deaf signers. Such examples of effective practice reported by participants are contacting via text messaging or email, being asked about their lived experiences and hearing aid use and being respected as Deaf signers by professionals speaking clearly, being helpful and professional at all times.

4.4.1. Limitations

The survey used the snowball sampling method, and it is not possible to report an exact response rate. Also, there are no official records on how many Deaf signers wear hearing aids in England, and it is difficult to estimate the response rate on the population size. The number of participants in this study generated sufficient data to provide meaningful results; however, increasing these numbers would strengthen claims made through enabling more complex statistical analysis. Another limitation is the self-reporting nature of the data. The survey probably recruited people who are more likely to have something to say about hearing aid clinics compared to someone who may not have any issues.

The online survey was made available in both English and BSL. However, participants could not respond to open questions in BSL (they could in written English) because of the online platform’s design limitations. Finally, the demographics reported are unequal in gender, age and ethnicity (mainly female in the 40–50 age group and White British which could be potentially viewed as “inclusion bias”) and no data were collected on educational attainment, social status or employment. The younger and older (60+) age groups did not engage much with the survey and one of the possibilities could be that social media advertising was limited to Facebook and Twitter. Other sources of social media that the younger generations use could have been sought.

5. Conclusion

The study’s strength is that it is the first to survey the experiences of Deaf British sign language users who use hearing aids and access adult hearing aid services from a culturally Deaf perspective led by a Deaf researcher. The results highlight an opportunity for all providers to enhance their clinical practice by assessing their communication provision, waiting room experience, communicating with Deaf signers, training needs to understand culture and language that will encompass understanding why and how Deaf signers use their hearing aids. Furthermore, making changes could result in significant improvement in patient satisfaction.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (333.8 KB)Acknowledgment

The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- ASHA. 2019. “ASHA Asserts ASL is a Distinct Language.” Accessed 1 March 2022. 10.1044/leader.AN5.24072019.64.

- Balint, E. 1969. “The possibilities of patient-centred medicine.” The Journal of the Royal College General Practice V17 (82):269–276. PMCID: PMC2236836

- Barnett, S., M. McKee, S. Smith, and T. Pearson. 2011. “Deaf Sign Language Users, Health Inequities, and Public Health: Opportunity for Social Justice.” Preventing Chronic Disease 8 (2):A45.

- Bauman, H.-D, Philosophy Documentation Center. 2008. “Listening to Phonocentrism with Deaf Eyes: Derrida’s Mute Philosophy of (Sign) Language.” Essays in Philosophy 9 (1):41–54. doi:10.5840/eip20089118

- Billard, I. 2014. “The Hearing and Otitis Program: A Model of Community Based ear and Hearing Care Services for Inuit of Nunavik.” Canadian Journal of Speech-Language Pathology & Audiology 38 (2):206–217.

- British Deaf Association (BDA). 2018. “Facts and Figures Within the UK: British Deaf Association.” Accessed 1 March 2022. http://www.bda.org.uk/bsl-statistics.

- Brown, A. 2018. “Improving Health Literacy in Deaf American Sign Language Users.” Internet Journal of Advanced Nursing Practice 17 (1):1–1. doi:10.5580/IJANP.52880

- Butler, C, and F. Martin. 1987. “A Survey of the Deaf Community Concerning Their Opinions, Needs and Knowledge of Audiology and Audiology Services.” American Annals of the Deaf 132 (3):221–226. doi:10.1353/aad.2012.0746

- Children’s Health Queensland Hospital and Health Services. 2017. “Milpa Binna: Families Learning and Sharing Their Hearing Loss Journey.” Accessed 1 March 2022. http://www.childrens.health.qld.gov.au/chq/our-services/community-health-services/healthy-hearing-program/mipla-binna/.

- Children’s Health Queensland Hospital and Health Services. 2017b. “Deadly Ears: Helping Little People to Hear, Learn, Talk and Play.” Accessed 1 March 2022. https://www.childrens.health.qld.gov.au/chq/our-services/community-health-services/deadly-ears/.

- Choi, J., K. Shim, N. Shin, C. Nieman, S. Mamo, H. Han, and F. Lin. 2019. “Cultural Adaptation of a Community-Based Hearing Health Intervention for Korean American Older Adults with Hearing Loss.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology 34 (3):223–243. doi:10.1007/s10823-019-09376-6

- Cottrell, C., L. Medwetsky, P. Boudreault, and B. Easterling. 2021. “Assessing Audiologists’’ Exposure, Knowledge and Attitudes when Working with Individuals Within the Deaf Culture.” Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 32 (7):426–432. doi:10.1055/s-0041-1729221

- Cross, T., B. Bazron, K. Dennis, and M. Isaacs. 1989. Towards a Culturally Competent System of Care Vol.1. Washington DC: Georgetown University Child Development Centre.

- Cue, R., K. Pudans-Smith, A. Wolsey, J. Wright, and D. Clark. 2019. “The Odyssey of Deaf Epistemology: A Search for Meaning-Making.” American Annals of the Deaf 164 (3):395–422.

- Dammeyer, J., C. Lehane, and M. Marschark. 2017. “Use of Technological Aids and Interpretation Services Among Children and Adults with Hearing Loss.” International Journal of Audiology 56 (10):740–748. doi:10.1080/14992027.2017.1325970

- Davis, L. 1995. Enforcing Normalcy: Disability, Deafness, and the Body. London, New York: Verso.

- Delnoij, D., J. Rademakers, and P. Groenewegen. 2010. “The Dutch Consumer Quality Index: An Example of Stakeholder Involvement in Indicator Development.” BMC Health Services Research 10:88. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-10-88

- Derrida, J. 1976. Of Grammatology. Baltimore, MA: The John Hopkins University Press.

- Emond, A., M. Ridd, H. Sutherland, L. Allsop, A. Alexander, and J. Kyle. 2015. “Access to Primary Care Affects the Health of Deaf People.” British Journal of General Practice 65 (631):95–96. doi:10.3399/bjgp15X683629

- Fellinger, J., D. Holzinger, and R. Pollard. 2012. “Mental health of deaf people.” Lancet (London, England) 379 (9820):1037–1044. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61143-4

- Ferguson, M., P. Kitterick, L. Chong, M. Edmondson-Jones, F. Barker, and D. Hoare, Cochrane ENT Group. 2017. “Hearing Aids for Mild to Moderate Hearing Loss in Adults.” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2017 (9). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012023.pub2

- Friedner, M. 2016. “Understanding and Not-Understanding: What Do Epistemologies and Ontologies Do in Deaf Worlds?” Sign Language Studies, 16 (2):184–203. doi:10.1353/sls.2016.0001

- Harris, L, and R. Paludneviciene. 2011. “Impact of Cochlear Implant on the Deaf Community.” In Cochlear Implants: Evolving Perspectives, edited by R. Paludneviciene and I. Leigh, 3–15. Washington DC: Gallaudet University Press.

- Hendriks, M., J. Dahlhaus-Booij, and A. M. Plass. 2017. “Clients’ Perspective on Quality of Audiology Care: Development of the Consumer Quality Index (CQI) ‘Audiology Care’ for Measuring Client Experiences.” International Journal of Audiology 56 (1):8–15. doi:10.1080/14992027.2016.1214757

- Holmes, J. 2017. “Expert Listening Beyond the Limits of Hearing: Music and Deafness.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 70 (1):171–220. doi:10.1525/jams.2017.70.1.171

- Hommes, R. E., A. I. Borash, K. Hartwig, and D. DeGracia. 2018. “American Sign Language Interpreters Perceptions of Barriers to Healthcare Communication in Deaf and Hard of Hearing Patients.” Journal of Community Health 43 (5):956–961. doi:10.1007/s10900-018-0511-3

- Hulme, C., A. Young, and K. Munro. 2021. “Exploring the Lived Experiences of British Sign Language (BSL) Users who Access NHS Adult Hearing Aid Clinics: An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis.” International Journal of Audiology 61 (9):744–751. doi:10.1080/14992027.2021.1963857

- Jama, G., S. Shahidi, J. Danino, and J. Murphy. 2020. “Assistive Communication Devices for Patients with Hearing Loss: A Cross-Sectional Survey of Availability and Staff Awareness in Outpatient Clinics in England.” Disability and Rehabilitation-Assistive Technology 15 (6):625–628. doi:10.1080/17483107.2019.1604823

- Joint Commissioning Panel for Mental Health. 2017. “Guidance for Commissioners of Primary Care Mental Health Services for Deaf People (Psychological Therapies).” The Royal College of Psychiatrists. Accessed 1 March 2022. https://www.jcpmh.info/resource/guidance-commissioners-primary-care-mental-health-services-deaf-people/.

- Kuenburg, A., P. Fellinger, and J. Fellinger. 2016. “Health Care Access Among Deaf People.” Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 21 (1):1–10.

- Kushalnagar, P., R. Paludneviciene, and R. Kushalnagar. 2019. “Video Remote Interpreting Technology in Health Care: Cross-Sectional Study of Deaf Patients’ Experiences.” JMIR Rehabilitation and Assistive Technologies 6 (1):e13233. doi:10.2196/13233

- Ladd, P. 2003. Understanding Deaf Culture: In Search of Deafhood. Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters.

- Marschark, M, and H. Knoors. 2015. “Educating Deaf Learners in the 21st Century: What We Know and What We Need to Know.” In Educating Deaf Learners: Creating a Global Evidence Base, edited by H. Knoors and M. Marschark, 617–647. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Mattingly, W., K. Buckner, and S. Pena. 2019. “Towards Multi-Lingual Pneumonia Research Data Collection Using the Community-Acquired Pneumonia International Cohort Study Database.” Journal of Respiratory Infections 3 (1):1–4. doi:10.18297/jri/vol3/iss1/2

- Mental Health Reform. 2021. Cultural Competency Toolkit. Dublin: Mental Health Reform.

- Meyer, C., C. Barr, A. Khan, and L. Hickson. 2017. “Audiologist-Patient Communication Profiles in Hearing Rehabilitation Appointments.” Patient Education and Counseling 100 (8):1490–1498. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2017.03.022

- Mitchiner, J. C. 2015. “Deaf Parents of Cochlear-Implanted Children: Beliefs on Bimodal Bilingualism.” Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 20 (1):51–66. doi:10.1093/deafed/enu028

- NHS England. 2016. Commissioning Services for People with Hearing Loss: A Framework for Clinical Commissioning Groups. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/HLCF.pdf. (Accessed: 01/03/2022)

- NHS England. 2016. The Accessible Information Standard (DCB1605). Leeds: NHS England.

- NHS England/Primary Care Commissioning. 2018. Guidance for Commissioners: Interpreting and Translation Services in Primary Care. Leeds: NHS England.

- Panning, P., R. Lee, and S. Misurelli. 2021. “Breaking Down Communication Barriers: Assessing the Need for Audiologists to Have Access to Clinically Relevant Sign Language.” Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 32 (4):261–267. Aprdoi:10.1055/s-0041-1722988

- Parmar, B., K. Mehta, D. Vickers, and J. Bizley. 2021. “Experienced Hearing Aid Users’ Perspectives of Assessment and Communication Within Audiology: A Qualitative Study Using Digital Methods.” International Journal of Audiology. 61:11, 956-964, DOI: 10.1080/14992027.2021.1998839

- Pollard, R. Q., Jr., and S. Barnett. 2009. “Health-Related Vocabulary Knowledge Among Deaf Adults.” Rehabilitation Psychology 54 (2):182–185. doi:10.1037/a0015771

- Public Sector Equality Duty, 2011[Online]. Accessed 1 March 2022. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/15/section/149.

- Reel, L., C. Hicks, N. Ortiz, and A. Rodriguez. 2015. “New Resources for Audiologists Working with Hispanic Patients: Spanish Translations and Cultural Training.” American Journal of Audiology 24 (1):11–22. doi:10.1044/2014_AJA-14-0027

- Rogers, K. D., A. Young, K. Lovell, M. Campbell, P. R. Scott, and S. Kendal. 2013. “The British Sign Language Versions of the Patient Health Questionnaire, The Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-Item Scale, and the Work and Social Adjustment Scale.” Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 18 (1):110–122. doi:10.1093/deafed/ens040

- Rogers, K., M. Pilling, L. Davies, R. Belk, C. Nassimi-Green, and A. Young. 2016. “Translation, Validity and Reliability of the British Sign Language (BSL) Version of the EQ-5D-5L.” Quality of Life Research 25 (7):1825–1834. doi:10.1007/s11136-016-1235-4

- SignHealth. 2022. “Review of the NHS Accessible Information Standard” [online]. Accessed 1 March 2022. https://signhealth.org.uk/resources/research/review-of-the-nhs-accessible-information-standard/?utm_campaign=AIS.

- Steinberg, A., S. Barnett, E. Meador, A. Wiggins, and P. Zazove. 2006. “Health Care System Accessibility. Experiences and Perceptions of Deaf people.” Journal of General Internal Medicine 21 (3):260–266. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00340.x

- Sutton-Spence, R, and B. Woll. 1999. The linguistics of British sign language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- The British Irish Hearing Instrument Manufacturers Association. 2019. “BIHIMA Quarter 3 Market Statistics 2021.” Accessed 1 March 2022. https://www.bihima.com/download/bihima-q3-2021-market-data/.

- The Equality Act, 2010 [online]. Accessed 1 March 2022 https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/15/contents.

- Ullarui, A. 2022. Audiology in Diverse Communities: A Tool to Help Clinicians Working with Spanish-Speaking Patients and Families. San Diego: Plural Publishing.

- Watermeyer, J., A. Kanji, and S. Sarvan. 2017. “The First Step to Early Intervention following Diagnosis: Communication in Pediatric Hearing Aid Orientation Sessions.” American Journal of Audiology 26 (4):576–582. doi:10.1044/2017_AJA-17-0027

- Young, A., F. Espinoza, C. Dodds, K. Rogers, and R. Giacoppo. 2021. “Adapting an Online Survey Platform to Permit Translanguing.” Field Methods 33 (4):388–404. doi:10.1177/1525822X21993966

- Young, A., J. Napier, and R. Oram. 2019. “The Translated Deaf Self, Ontological (In)security and Deaf Culture.” The Translator 25 (4):349–368. doi:10.1080/13556509.2020.1734165

- Young, A., K. Rogers, L. Davies, M. Pilling, K. Lovell, S. Pilling, R. Belk, G. Shields, C. Dodds, M. Campbell, et al. 2017. “Evaluating the Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness of British Sign Language Improving Access to Psychological Therapies: An Exploratory Study.” Health Services and Delivery Research 5 (24):1–196. doi:10.3310/hsdr05240