Abstract

This study, which explored how commercial products and services are displayed by different influencer categories on Instagram, was motivated by the need for a more transparent picture of the commercial content consumed by followers. Drawing from an ethnographic content analysis of 3,278 Instagram posts, we found that social media influencers with a minor following had a higher number and a broader variety of commercial posts. Additionally, products and services were displayed through subtle patterns, often integrated into the influencers’ lifestyles and social activities. Although social media influencers with many followers had fewer commercial posts, their display of products and services was more direct and informative. The study closes a literature gap by providing a more refined understanding of social media influencers’ commercial content on Instagram. It offers managerial implications based on the societal impact of the commercial content that people consume.

People worldwide spend a substantial amount of time on Instagram, primarily in search of socialization, information, entertainment, and inspiration (Voorveld et al. Citation2018). Simultaneously, content that aims to sell, promote, and advertise products, businesses, or services (commercial content) is constantly and subtly interwoven in people’s feeds, frequently by popular social media influencers (Hogsnes, Grønli, and Hansen Citation2023). With the global influencer market value reaching 21.1 billion US dollars as of 2023 (Statista Citation2023), marketing scholars have directed their attention to how this subtle interweaving of commercial content affects people’s ability to critically evaluate the content they consume (Boerman and Müller Citation2022; Borchers and Enke Citation2022; Karagür et al. Citation2022).

Social media influencers can be defined as regular internet users who achieve large audiences on social media through the textual and visual narration of their personal lives and lifestyles (Abidin Citation2021, 5). Even though much of their role involves displaying commercial content, people engage with them based on personal interests (Audrezet, De Kerviler, and Guidry Moulard Citation2020; Gross and Von Wangenheim Citation2022) and tend to believe that influencers act individually rather than on behalf of marketers (Borchers and Enke Citation2022). As such, people are likely to confuse a commercially motivated message promoted by social media influencers with a personal recommendation (Boerman and Müller Citation2022). While influencers must follow rules and guidelines that require them to disclose a post’s intent (Abidin et al. Citation2020), studies have revealed that people do not always notice these disclosures (Hudders, De Jans, and De Veirman Citation2020). In other cases, the rules are overlooked (Abidin et al. Citation2020). Consequently, people are exposed to and influenced by massive commercial content that they may not be able to critically evaluate. Thus, there is a need for more knowledge about the content people consume.

Although advertising scholars highlight the vital role of social media influencers in advertising (e.g., Gross and Wangenheim Citation2022; Tafesse and Wood Citation2021), most research has been conducted from an audience perspective and is concerned with the appeal and efficacy of advertisements (Hudders, De Jans, and De Veirman Citation2020). According to reviews by Hudders, De Jans, and De Veirman (Citation2020) and Vrontis et al. (Citation2021), limited studies have focused on the commercial content of social media influencers’ posts, especially the practices among different influencer categories. In academia and in practice, it is common to categorize social media influencers on Instagram according to the number of followers they have (Campbell and Farrell Citation2020; Inzpire.me Citation2021; Klear Citation2021). Number of followers is an indication of how many people influencers can reach with their commercial content. Each category plays different roles in the influencer marketing field (Kay, Mulcahy, and Parkinson Citation2020), and their different influential capabilities are debated (Campbell and Farrell Citation2020; Domingues Aguiar and van Reijmersdal Citation2018). For example, the so-called micro-influencers (1,000–10,000 followers) are frequently understood to provide intimacy, almost like a distant friend, as they have fewer followers and brand collaborations (Campbell and Farrell Citation2020). In contrast, the so-called macro-influencers (500,000–1 million followers) are less intimate but play a more prominent role as information amplifiers because they reach a more extensive and more diverse base of followers (Abidin Citation2021). For the most part, studies have yet to investigate how different influencer categories display commercial content. A few exceptions exist (e.g., Alassani and Göretz Citation2019; Britt et al. Citation2020), and although these studies offer valuable insights, they focus on one type of sponsored post or on selected influencer categories. As such, this study contributes to the discussion by taking a broader approach, focusing on all forms of products and services and all influencer categories displaying commercial content. By taking this perspective, we can provide a broad and nuanced overview of the commercial content people consume.

This study addresses the following research question: How are commercial products and services displayed by different influencer categories on Instagram? To answer this question, we conducted an ethnographic content analysis of 3,278 Instagram posts from 33 social influencers. The data collection focused on females between the ages of 18 and 34 who are active on Instagram, as this is the dominant influencer group and Instagram is a leading platform in the industry (Statista Citation2023). Due to its dominance in influencer marketing, we selected the fashion and beauty domain as the specific context (Djafarova and Rushworth Citation2017). We focused our study on Scandinavia because most of the literature has examined other regions, such as North America and Southeast Asia (Abidin et al. Citation2020). We followed a categorization scheme developed by Abidin (Citation2021) specifically for the Scandinavian market that is based on the number of followers: micro-influencers (1,000–10,000 followers), influencers (10,000–500,000 followers), macro-influencers (500,000–1 million followers), and mega-influencers (1 million + followers). Abidin’s (Citation2021) categorization calculates the number of followers in each category against the population and size of the Scandinavian countries. According to Abidin (Citation2021), nano-influencers, with fewer than 1,000 followers, constitute a fifth category. However, this category is rarely considered for commercial purposes in the Scandinavian market (e.g., Inzpire.me Citation2021) and was not investigated in this study. We focus on Instagram “posts” in this study. Other formats such as “stories,” “reels,” and “channels” may be interesting to study, but posts offer the flexibility to share photos, video, carousels (multiple images or videos in one post), and longer-form captions (up to 2,200 characters) that appear permanently on the social media influencer’s profile and on followers’ feeds (Caldeira, Van Bauwel, and De Ridder Citation2021). Therefore, we considered posts to broadly represent content display and prioritized this format.

Our main findings demonstrate that micro-influencers and influencers had a higher number and a broader variety of commercial posts. Additionally, products and services were displayed through subtle patterns, often integrated into the influencers’ lifestyles and social activities. Macro- and mega-influencers had fewer commercial posts, but their display of products and services was more direct and informative. The study provides two main contributions to influencer marketing literature. First, the study reveals how the increased establishment and commercialization of influencer marketing contribute to a new generation of micro-influencers. Second, we contribute insights into the subtle nature of micro-influencers’ and influencers’ commercial displays as opposed to macro- and mega-influencers’ more direct and informative displays of commercial content. These findings close a literature gap by providing a broad and nuanced understanding of the commercial content displayed (Hudders, De Jans, and De Veirman Citation2020; Vrontis et al. Citation2021). Our study also emphasizes how the increased commercialization of the influencer industry has contributed to the complex challenges created when people’s social lives are seamlessly connected to commercial activities. Although the study does not investigate commercial transparency per se, the findings are valuable for consumer authorities and for conversations taking place in the literature (Borchers and Enke Citation2022; Hogsnes, Grønli, and Hansen Citation2023; Karagür et al. Citation2022) concerned with the societal implications of the consumption of commercial content.

Background

Instagram has evolved into an established marketing platform. Marketing on Instagram includes several activities, including the development of business profiles for organic interactions with customers, the strategic placement of ads (Instagram Citation2023), and influencer marketing (Martínez-López et al. Citation2020). Instagram has become increasingly valuable for marketers because they can interact directly with customers, create engaging and inspirational content, and target specific customers in their social space (Casaló, Flavián, and Ibáñez-Sánchez Citation2020). It is also common for marketers to collaborate with social media influencers, often referred to as “influencer marketing” (Hudders, De Jans, and De Veirman Citation2020), where they display products, brands, organizations, or ideas on their social media profiles (De Veirman, Cauberghe, and Hudders Citation2017). Marketers typically pay social media influencers to convey commercial messages on their behalf, invite them to exclusive events, or send them free products in the hope that they will showcase them on their social media influencers profiles (De Veirman, Cauberghe, and Hudders Citation2017). Social media influencers can also be brand ambassadors, and those with many followers develop their own brands (Rundin and Colliander Citation2021). Typically, the number of followers on Instagram defines an influencer’s position in the marketing field (Abidin Citation2021; Campbell and Farrell Citation2020). Because our study investigated the commercial content displayed by different social media influencer categories, our theoretical background covers three areas: influencer categories, commercial content, and display of commercial content.

Influencer Categories

It is not viable to conceptualize all social media influencers as the same (Kay, Mulcahy, and Parkinson Citation2020). As illustrated in , they can be divided into five main categories (Abidin Citation2021).

Table 1. Social media influencer classifications in Denmark and Sweden (Abidin Citation2021, 6).

When investigating social media influencers in Scandinavia, Abidin (Citation2021) emphasized the importance of accounting for specific categories scaled to the population. In countries such as Denmark (population 5.8 million), Norway (population 5.3 million), and Sweden (population 10.2 million), a mega-influencer has more than 1 million followers, whereas those with fewer than 1,000 followers are considered nano-influencers. Number of followers in each category estimates how many people influencers reach on Instagram versus the country’s population. Different approaches exist, such as categories based on language groups or social media platforms. One might also categorize social media influencers by the number of “likes” (Kay, Mulcahy, and Parkinson Citation2020) or their genre (Abidin Citation2021). In this study, we utilize Abidin’s (Citation2021) categorization because it was developed specifically for Scandinavian countries and fits Instagram and the fashion and beauty industry. Nano-influencers are rarely involved in commercial collaborations in the Scandinavian market (e.g., Inzpire.me Citation2021) and are therefore not included in this study. From now on, we refer to all categories in general as “social media influencers.”

Studies have investigated the role of each influencer category in the influencer marketing field (Campbell and Farrell Citation2020; Park et al. Citation2021). Mega- and macro-influencers are often associated with broadcast media, where they act as information amplifiers because they reach large audiences (Abidin Citation2021). Macro- and mega-influencers also tend to promote their own brands or those they co-designed (Rundin and Colliander Citation2021), emphasizing their status in marketing. However, other studies have found that the established position of macro- and mega-influencers contributes to decreased influential power. For example, because macro- and mega-influencers are involved in a broader range of commercial collaborations, they use more professional photographs and tag more brands than micro-influencers (Alassani and Göretz Citation2019). This increased commercialization may decrease the perception of intimacy. Influencers are often viewed as opinion leaders (Abidin Citation2021) and play an essential role in the information flow (Casaló, Flavián, and Ibáñez-Sánchez Citation2020). Information from mass media flows through a mediation process in which influential people process the information and transmit it to the public (Lin, Bruning, and Swarna Citation2018). Micro- and nano-influencers are thought to be persuasive converters (Abidin Citation2021). Because micro-influencers have small followings, some researchers have found that they are less likely to “sell out” than other categories (Campbell and Farrell Citation2020). They represent a more significant niche and appear to be more similar to those who follow them, so they tend to convey a greater sense of trust and authenticity (Campbell and Farrell Citation2020; Park et al. Citation2021). To expand on these conversations, our study explores the commercial content displayed by these different influencer categories.

Commercial Content

We define “content” as the resources available in a network (Kane, Alavi, and Borgatti, 2014) and “commercial” as intended for commercial purposes such as monetizing, selling, promoting, and advertising a product, business, or service (Merriam Webster Citation2024). Being a social media influencer involves displaying commercial content on social media (Gross and Von Wangenheim Citation2022). Influencers’ marketing value, however, is based on nonsponsored posts about their everyday lives (Gross and Von Wangenheim Citation2022). In contrast to commercial content, nonsponsored posts are unrelated to brands and do not include any display of brands or products. They often contain personal stories, entertainment, inspirational images, and life captures (Zarei et al. Citation2020). As such, social media influencers’ Instagram profiles link nonsponsored posts and those containing commercial content.

Commercial content consists of sponsored posts, nonsponsored commercial posts, and hidden sponsored commercial posts. Sponsored posts integrate brands and brand messages that are compensated by a sponsor (Zarei et al. Citation2020). Such posts are incentivized and influenced by companies, which have some control over the advertising message (Zarei et al. Citation2020). Sponsored posts tend to have captions with clear advertising messages. Captions are textual information added to a post that often aligns with the visual image or video (Caldeira, Van Bauwel, and De Ridder Citation2021). Marketers use captions as an advertising tool; they contain advertising messages and provide helpful information about brands and products, such as where to buy a product, where to get the best offers, or the social influencer’s experience with a product (Gross and Von Wangenheim Citation2022, 291).

However, the degree to which a marketer can control sponsored posts depends on the marketing activity. Social media influencers often receive monetary rewards through complimentary products or invitations to exclusive “Instagrammable” events, in the hope that the products will be displayed (De Veirman, Cauberghe, and Hudders Citation2017). In some cases, it is common for marketers to refrain from declaring a commercial collaboration in their captions, even if they are paying to convey a specific message. This is called a hidden sponsored post (Zarei et al. Citation2020). In this case, a post may include captions with product recommendations, brand tags, or emojis, for example, but it omits captions declaring the use of monetary incentives to post the content (Abidin et al. Citation2020). In addition to sponsored and hidden sponsored posts, social media influencers often post about products and brands for which they receive no monetary rewards (Jorge, Marôpo, and Nunes Citation2018), such as by recommending a product, tagging clothing brands they wear, or tagging restaurants they visit. We refer to this as a nonsponsored commercial post. Because our study is motivated by the need to gain insight into the commercial content followers consume, we study all forms of posts in which products and services are displayed under the umbrella of “commercial content.”

Display of Commercial Content

Specific visual displays are used in photos and videos when social media influencers post commercial content. In most cases, they appear at the center of the image, displaying products or services being worn or used (Abidin Citation2016), such as in a selfie, whole-figure, or half-figure photo conceptualized as a “portrait” (Bainotti, Caliandro, and Gandini Citation2021). They also tend to display material assemblages, such as shoes or bags characterized as “material objects” at the center of a post. These portraits or material objects are photographed and combined to create “instaworthy” posts (Vanninen, Mero, and Kantamaa Citation2023) that align with specific Instagram visual aesthetics (Bainotti, Caliandro, and Gandini Citation2021). Displaying specific “settings” such as landscapes, celebrations, and general surroundings is common (Bainotti, Caliandro, and Gandini Citation2021). Personal captions are often attached to the visuals, often related to the influencer’s preference and identity. Hidarto (Citation2021) found that captions include a vast amount of language intended to establish familiarity with the audience. In other scenarios, the captions include limited information, letting the photo or video “speak for itself” when the visual surroundings are essential (Vanninen, Mero, and Kantamaa Citation2023). In this case, commercial elements appear through brand tags or hashtags.

In their textual and visual displays, social media influencers are concerned with creating personal intimacy or forming an intimate bond with their followers (Jorge, Marôpo, and Nunes Citation2018; Caldeira, Van Bauwel, and De Ridder Citation2021). For example, Caldeira, Van Bauwel, and De Ridder (Citation2021) identified several visual displays of social media influencer portraits, often accompanied by captions that included brand tags or hashtags or captions that exalted the influencer’s enjoyment of the brand. The motive behind such subtle commercial displays is to provide a source of inspiration and enjoyment (Djafarova and Bowes Citation2021). The commercial elements in this case are less direct and more subtle in nature (Campbell and Grimm Citation2019). Gross and Von Wangenheim (Citation2022) refer to this type of commercial display as transformational advertising, emphasizing information about the experience of using the brand or product instead of promoting the product solely from an objective perspective.

Product information and more descriptive messages are also common in influencers’ displays of products and services. Hidarto (Citation2021) found that social media influencers tend to include written captions with descriptive information about a product’s quality and “promises.” Jorge, Marôpo, and Nunes (Citation2018) found that influencers often carefully explain why they genuinely like a product. In this case, although the negotiated authenticity and commercialism are more direct, persuading followers to purchase the product is based on their own experiences (Hidarto Citation2021). Compared to more subtle tones, such displays contain a clear commercial message. These practices can be understood as informational advertising, based on providing rational information directly linked to the advertised brands and products.

Although research on social media influencers’ commercial content display is expanding, there is a need for a broader and more refined understanding of how they display that commercial content (Hudders, De Jans, and De Veirman Citation2020; Vrontis et al. Citation2021).

Methods

We conducted an ethnographic content analysis (Altheide Citation1987; Bainotti, Caliandro, and Gandini Citation2021; Rose Citation2014) to investigate how different influencer categories on Instagram display commercial content. This method gave us direct access to the commercial content posted by social media influencers. It involved manual coding, which has demonstrated good validity because it allows researchers to consider text and image context and social embeddedness (Altheide Citation1987). The ethnographic content analysis involved three steps: (1) social media influencer selection, (2) coding, and (3) data analysis.

Social Media Influencer Selection

First, we identified females aged 18 to 34 as the dominant group in the influencer industry (Statista Citation2021) in Norway, Sweden, and Denmark. Although a broader age range could have enriched the analysis, the results would not have been representative of the dominant commercial display in the industry. We focused on Scandinavia because other researchers have mainly considered the influencer market in the United States and Southeast Asia (Abidin et al. Citation2020). Given the rapid growth of influencer marketing worldwide, it is crucial to expand the geographic coverage of this research (Vrontis et al. Citation2021). Second, we selected the fashion and beauty industry because this is the most prominent market in the influencer marketing industry (Statista Citation2021). Third, we studied the micro-influencer, influencer, macro-influencer, and mega-influencer categories identified by Abidin (Citation2021) and selected candidates based on their number of Instagram followers, aligned with the population and size of Scandinavian countries. We did not assess nano-influencers, who rarely participate in the Scandinavian market (Inzpire.me Citation2021). To identify candidates based on our criteria, we applied Klear (Citation2021), an artificial intelligence (AI) tool used by marketers when searching for influencers because it allows demographic analysis and campaign management. We were able to apply filters such as “female,” “18–34,” “fashion,” “beauty,” “Sweden,” “Norway,” and “Denmark” to ensure a selection that fit our criteria. To confirm that the candidates met our criteria, we applied a second tool called Inzpire.me (Citation2021), as there is no consensus on what defines a top influencer. Inzpire.me provides insights on influencers’ Instagram profiles, such as demographics and engagement. Inzpire.me and Klear are leading platforms in the Scandinavian market’s approach to influencer searches. We applied both to ensure that we found appropriate candidates.

Nine micro-influencers and influencers were selected, with three representing each Scandinavian country. Eight macro-influencers and seven mega-influencers were selected (three Swedish and three Danish per category). Due to the lack of representation in these categories, we could analyze only two macro-influencers and one mega-influencer from Norway. In total, we had 33 candidates for analysis.

Coding

We developed codes to guide the ethnographic content analysis (Altheide Citation1987) on both denotative and connotative levels (Bainotti, Caliandro, and Gandini Citation2021). The denotative analysis focused on the objective representation of the content at first glance, such as whether the post contained a picture or a video, whether the post contained a portrait or a material object, and whether the caption included emojis or hashtags. The connotative analysis determined whether there was an association different from the literal meaning. At this level, the subjective meaning behind the posts was essential (Bainotti, Caliandro, and Gandini Citation2021). We developed six steps to guide our coding on these two levels.

Codes on the denotative level involved five steps. The first step identified the number of commercial posts (sponsored, nonsponsored, and hidden sponsored) posted by the different influencer categories. The second step identified commercial captions to increase our knowledge of whether the post contained a clear commercial message. A caption was recognized as commercial if it contained brand tags, visible brand labels, or commerce-related information. The third step identified the format of each commercial post, distinguishing among single photos, single videos, and carousels (a combination of both).

The fourth and fifth steps developed visual and textual codes of the commercial posts identified in the first step to identify how each influencer category displayed commercial products and services. Our goal was to identify what each photo, video, and carousel represented both visually and textually, that is, the textual elements in the captions attached to the post. We familiarized ourselves with the 33 candidates’ postings by reviewing the features of their posts to gain a preliminary understanding of the content (Altheide Citation1987). We recognized many portraits of themselves as selfies or full-figure or half-figure photos. We also recognized many images of objects and social gatherings. One coauthor made brief notes about standard features, and we discussed our observations with one another to ensure their validity. This led to the development of three visual codes: portrait, material object, and setting. Regarding the textual codes, we found six main patterns: emojis, hashtags, brand tags, product descriptions, texts describing personal opinions about the products, and texts describing the influencer’s mood. Given the exploratory nature of ethnographic coding (Altheide Citation1987), other descriptive and analytical codes were expected and allowed to emerge (Bainotti, Caliandro, and Gandini Citation2021).

The sixth step involved gathering information on a connotative level. At this stage, we described the subjective meaning behind each post in one or two lines, using Excel (Bainotti, Caliandro, and Gandini Citation2021). Specifically, the goal was to grasp the commercial context, such as what the post represented beyond the objective meanings identified in the first five steps. For example, on a denotative level, we identified a portrait in carousel format with commerce-related information in the caption, whereas the connotative level allowed us to consider the surroundings of the post and whether it promoted the influencer’s own brand or a brand the influencer co-designed or represented as an ambassador. We also identified whether the influencers tagged brands or friends in the posts and the emotional state of each post, such as whether it had a positive or negative tone (Bainotti, Caliandro, and Gandini Citation2021). Including both levels gave us a broad and nuanced view of how each influencer category displays commercial content.

provides an overview of the six steps we followed on a denotative and a connotative level.

Table 2. Codes developed for the ethnographic content analysis.

Once the steps were planned and the codes were developed, we started coding the posts of the 33 selected social influencers. To get a representative number, we selected their 100 latest Instagram posts. The coding process took three months, coding one post at a time in Excel as it was viewed. One of the social media influencers in the study had only 78 posts, so we ended up with a data set of 3,278 coded posts for data analysis.

Data Analysis

The data were first sorted into four separate Excel sheets with data from each influencer category (micro, influencer, macro, mega). Then the data were analyzed on a denotative level (steps 1–5) using a pivot diagram (Bainotti, Caliandro, and Gandini Citation2021) to count the following: (1) number of commercial posts, (2) number of commercial captions, (3) format (photo, video, or carousel), (4) visual codes used (portrait, material object, setting), and (5) textual codes used (hashtags, brand tags, emojis, descriptions, personal taste, mood). Once all the data were counted, we calculated the percentage distributions.

On a connotative level, the one to two lines of description for each post underwent a rigorous qualitative process involving an open, axial, and selective coding strategy (Strauss and Corbin Citation1998) to capture patterns in the commercial context for each influencer category. After the data were gathered, we performed axial coding, drawing connections between the data using a color-coded approach. We examined all four Excel sheets (micro, influencer, macro, mega) and assigned similar colors to data with a certain link. For example, many of the posts showed influencers posing in a carousel format, in wearables with brand tags, accompanied by short captions. All these posts were coded with a similar color. Once all the data were color-coded, we analyzed the data assigned similar colors and created one central category for each pattern that connected the codes (Strauss and Corbin Citation1998). In this way, we could identify patterns of how each influencer category displayed commercial content.

Two of the authors discussed and evaluated the denotative and connotative levels of analysis to ensure the validity by performing an “ethnographic ethic” (Altheide and Johnson Citation1994, 587). The ethnographic ethic included five elements the authors considered during data collection and analysis: (1) the substance of the analysis, such as the relationship between the observed commercial content and its considerable cultural, historical, and organizational contexts; (2) the relationship between the author conducting the analysis and the commercial content analyzed; (3) the point of view when rendering an interpretation of the ethnographic data; (4) the role of the reader in the final product; and (5) the authorial style used to render the description or interpretation.

Results

This section presents our findings regarding how each influencer category on Instagram displays commercial products and services.

Micro-Influencers

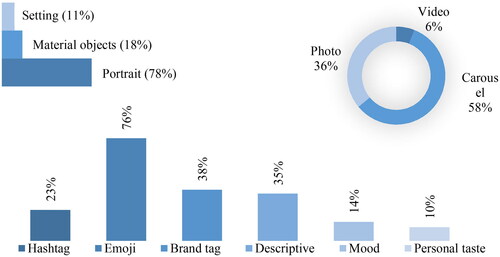

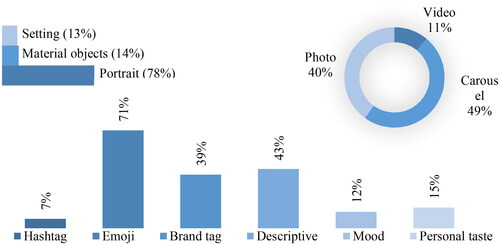

We began our analysis of micro-influencers by identifying the percentage of commercial posts. Of 900 posts analyzed, 501 contained commercial elements. Thus, micro-influencers had one of the highest percentages of commercial posts, with 56%. Of the 501 posts, 215 contained commercial captions (43%), making micro-influencers the category with the lowest percentage of commercial captions. In the next step we identified the format, visual codes, and textual codes used in micro-influencers’ commercial posts (). The patterns were not mutually exclusive.

On a connotative level, we identified four main patterns: portraits displaying wearables (n = 351), daily life captures (n = 72), close-ups of material objects (n = 49), and portraits applying material objects (n = 29). The two dominant patterns are explained in greater detail.

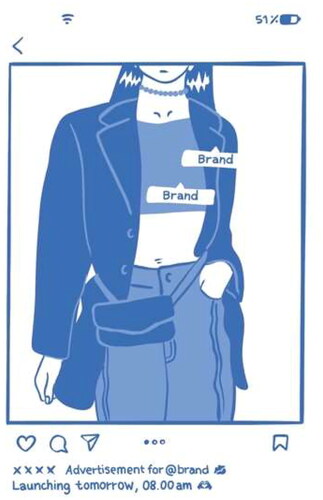

First, many posts included portraits displaying one or multiple wearables (). The surroundings in these posts were usually a big city, the seashore, or at home, intended to display wearables as inspirational daily life captures. Commercial elements usually appeared only in brand tags attached to the micro-influencers clothing. The images were generally accompanied by short captions with single emojis and brand tags; they rarely featured commercially descriptive elements. An interesting finding was that micro-influencers tended to tag a broader variety of brands, and they also tended to tag public relations agencies in their posts. Second, we identified that micro-influencers posted carousels displaying daily life captures. These posts often included photos and videos representing a day or a week in the influencers’ lives, and commerce often appeared as tags in what the micro-influencers were wearing. Such posts rarely included long descriptive text related to commercial collaborations with brands.

Influencers

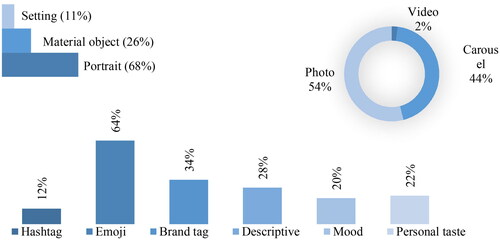

Out of 900 posts analyzed, 552 contained commercial elements (61%). Influencers were thus the category with the highest percentage of commercial postings. Of the 552 posts, 243 contained commercial captions (44%). We then calculated the percentage of visual formats, visual codes, and textual codes displayed in their commercial posts (). The patterns were not mutually exclusive.

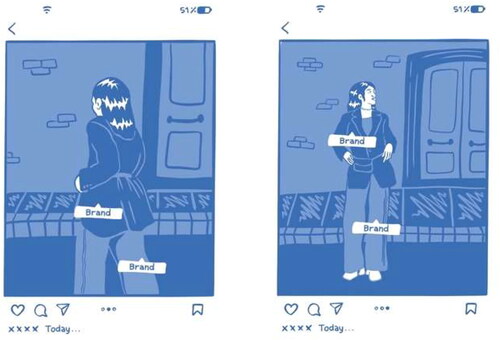

On a connotative level, we identified five main patterns: portraits displaying wearables (n = 309), close-ups of material objects (n = 121), social events and gatherings (n = 62), daily life captures (n = 41), and portraits applying material objects (n = 19). The two dominant patterns are exlained in greater detail.

First, like the micro-influencers, inflencers displayed many commercial posts showing wearables from multiple angles to highlight their taste and clothing preferences. In contrast to micro-influencers, however, influencers included more textual elements describing their taste. Second, the large number of single photos displaying material objects distinguished influencers from the other three categories ().

In these posts, the commercial product was generally centered in the photo, with visible brand labels, but the post’s context was not necessarily commercial or sales oriented. The captions of such posts rarely described a commercial collaboration, and brands were not necessarily tagged. However, a common feature of these posts was that most of the products promoted were from luxury brands, such as Chanel and Dior. Most of the captions included a single emoji or a short sentence describing the influencer’s taste, such as “My favorite.” In this pattern, there seemed to be a connection between the product displayed and the influencer’s preferences; rather than promoting brands to others, these posts used an object to promote the influencer’s profile.

Macro-Influencers

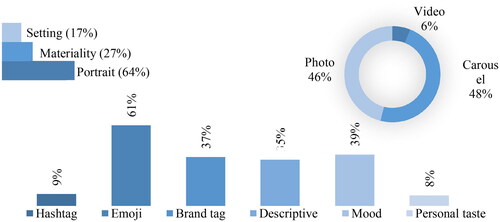

As in the other two categories, we began by identifying the percentage of commercial posts. Out of 800 posts analyzed, 371 contained commercial elements (46%). Surprisingly, macro-influencers were the category with the lowest percentage of commercial posts. Of the 371 commercial posts, 174 contained commercial captions (47%). We then calculated the visual formats, visual codes, and textual codes used in their commercial posts (). The patterns were not mutually exclusive.

On a connotative level, we identified five main patterns: portraits displaying wearables (n = 224), social activities (n = 65), close-ups of material objects (n = 23), portraits applying material objects (n = 32), and sponsored posts with clear advertising messages about their own brands (n = 27).

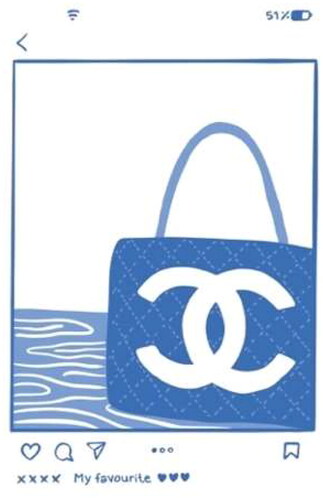

Like the other influencer categories, macro-influencers had an overwhelming number of posts showing themselves posing in wearables from multiple angles in either a single photo or a carousel format ().

However, in contrast to micro-influencers, macro-influencers often attached longer and more descriptive captions related to commercial collaborations. In some cases, the products displayed were also more visible in their posts. In contrast to the other categories, macro-influencers’ photos were more “professionally” constructed, and there was often a clear advertising message. Interestingly, some posts by macro-influencers included a clear advertising message about their own brands.

Mega-Influencers

Of 678 posts analyzed, 325 contained commercial elements (48%), and 166 of these 325 posts contained commercial captions (51%). Mega-influencers thus had the highest percentage of commercial captions. shows the distribution of formats, visual codes, and textual codes used by mega-influencers. The patterns were not mutually exclusive.

Mega-influencers posted portraits displaying wearables (n = 135), social activities (n = 72), close-ups of single material objects (n = 51), advertisements with a clear sponsored message about their own brands (n = 44), and portraits applying material objects (n = 20).

Mega-influencers’ extensive use of descriptions in their posts was an exciting finding that contrasted with the practice of influencers, who often attached personal opinions such as “My favorite” or “Love this bag.” We also discovered that mega-influencers had fewer variations in brand collaboration, and many posts displayed their own brands. Such posts had a clear sponsorship message and usually included portraits followed by a close-up of the product. Like the patterns identified among macro-influencers, mega-influencers’ portraits displayed wearables in a more “professional” manner ().

Discussion

Having presented our findings on how each influencer category displays products and services, in this section we take an integrated perspective and discuss how our findings measure up against established literature in the field. Specifically, we present two main contributions to influencer marketing literature, followed by a discussion of the implications and limitations of our study and topics for future research.

First, our study demonstrated that micro-influencers and influencers display a higher number and a broader variety of commercial posts. Studies have argued that micro-influencers are less commercially active or that they facilitate greater intimacy compared with other categories (Campbell and Farrell Citation2020; Djafarova and Rushworth Citation2017; Kay, Mulcahy, and Parkinson Citation2020; Park et al. Citation2021). For example, Kay, Mulcahy, and Parkinson (Citation2020) argued that micro-influencers appear to be more like their followers, so they tend to be more persuasive. Campbell and Farrell (Citation2020) found that micro-influencers’ recommendations seem more genuine than those made by macro-influencers, who may be viewed as more likely to “sell out.” In our study, however, we found that micro-influencers had one of the highest percentages of commercial posts (56%). They also promoted a broader variety of brands and tagged public relations agencies in their posts. One explanation for our findings could be that the growth of influencer marketing has contributed to a new generation of micro-influencers who have become better established and more commercialized.

Second, this study contributes insights into the main differences in the commercial content displays of the various influencer categories. We found that micro-influencers and influencers were more likely to subtly integrate products and services into their displayed lifestyles than the other two categories. Micro-influencers’ commercial posts resembled daily life captures. The captions were often short and contained limited information about brands or products. As such, we argue that social media influencers with fewer followers are more concerned about displaying products and services in “regular” settings, based on an appealing lifestyle (Abidin Citation2016). The motive behind such subtle commercial displays could be the desire to be a source of inspiration and enjoyment (Djafarova and Bowes Citation2021). These findings also align with transformational advertising, emphasizing the experience of using the featured products (Gross and Von Wangenheim Citation2022).

Macro- and mega-influencers are more direct in their commercial displays, often attaching long descriptive captions with detailed product information, as found in a study by Rundin and Colliander (Citation2021). We argue that macro- and mega-influencers act as informative sources for commercial messages to a greater extent than the other two categories. In this case, they are informers who share their knowledge with others and provide informational, educational, and supportive commercial content about products and services. This type of display can be understood as informational advertising, motivated by the goal of providing rational information directly linked to the advertised brands and products. These findings have implications for influencer marketing literature, as they contribute to the ongoing conversations regarding each influencer category’s role in the marketing field (Campbell and Farrell Citation2020; Kay, Mulcahy, and Parkinson Citation2020).

Managerial Implications

Our study suggests that it is essential for consumer authorities to pay attention to micro-influencers, as also found by Kay, Mulcahy, and Parkinson (Citation2020). Micro-influencers and influencers were among the categories with the most commercial postings and the fewest commercial captions. They also posted products and services more subtly than macro- and mega-influencers. Although we could not separate hidden commercial posts from nonsponsored commercial posts, the results indicate a lack of commercial disclosure among social media influencers who are likely in the early stages of their careers and may not have the necessary information to obey the rules and regulations. Overall, however, our results suggest that social media influencers are highly commercially active, regardless of category. Due to the increased commercialization of the influencer industry, it is important to recognize that using Instagram involves engaging with commercial content.

Limitations and Future Research

Our study has some limitations that need to be acknowledged. First, its focus was the Scandinavian market, where the populations of Norway and Denmark are just a little over 5 million citizens each. As such, fewer social media influencers are operating there, which may result in more established commercial positions among influencers with smaller follower bases. Future studies should focus on the commercial practices of micro-influencers in other countries. Second, we focused on Instagram posts but not Instagram stories, reels, or channels. Because these other formats are popular among social media influencers, investigating them in future studies could capture a more complete picture of how influencers integrate commerce into their content displays. Third, we focused on Instagram because it is a dominant platform, but many influencers operate on multiple platforms. Comparing the commercial content displayed on other social media platforms versus that on Instagram would be a relevant goal of future studies.

Conclusion

This study investigated how different influencer categories on Instagram display commercial products and services. We provided two main contributions to the influencer marketing literature. First, we found that micro-influencers and influencers had a higher number and a broader variety of commercial posts than macro- and mega-influencers. Second, we identified differences in each influencer category’s method of displaying products and services: micro-influencers and influencers often integrate their products and services into their displayed lifestyles, while macro- and mega-influencers are more direct and informative. Our study thus contributes to the conversations about influencer categories (Campbell and Farrell Citation2020; Djafarova and Rushworth Citation2017; Kay, Mulcahy, and Parkinson Citation2020; Park et al. Citation2021), emphasizing the differences in how they display commercial content. The study also provided managerial implications by emphasizing that people’s social lives involve engaging with commercial activities. Our findings contribute to discussions in the literature about the societal implications of the commercial content people consume (Borchers and Enke Citation2022; Hogsnes, Grønli, and Hansen Citation2023; Karagür et al. Citation2022).

Ethics Statement

The study was conducted with anonymous data and complies with the ethical regulations of the Norwegian knowledge sector’s service provider (Sikt Citation2024).

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mathilde Hogsnes

Mathilde Hogsnes (MSc, Kristiania University College) is a PhD candidate in Applied Information Technology, Kristiania University College, Oslo, Norway.

Tor-Morten Grønli

Tor-Morten Grønli (PhD, Brunel University) is a professor in Applied Computer Science at the Department of Economics, Innovation and Technology, Kristiania University College, Oslo, Norway.

Kjeld Hansen

Kjeld Hansen (MSc, IT University of Copenhagen) is a assistant professor in Information Technology at the Department of Economics, Innovation and Technology, Kristiania University College, Oslo, Norway.

References

- Abidin, Crystal. 2016. “Visibility Labour: Engaging with Influencers’ Fashion Brands and #OOTD Advertorial Campaigns on Instagram.” Media International Australia 161 (1): 86–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X16665177.

- Abidin, Crystal. 2021. “From “Networked Publics” to “Refracted Publics”: A Companion Framework for Researching “Below the Radar” Studies.” Social Media + Society 7 (1): 205630512098445. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120984458.

- Abidin, Crystal, Kjeld Hansen, Mathilde Hogsnes, Gemma Newlands, Mette Lykke Nielsen, Louise Yung Nielsen, and Tanja Sihvonen. 2020. “A Review of Formal and Informal Regulations in the Nordic Influencer Industry.” Nordic Journal of Media Studies 2 (1): 71–83. https://doi.org/10.2478/njms-2020-0007.

- Alassani, Rachidatou, and Julia Göretz. 2019. “Product Placements by Micro and Macro Influencers on Instagram.” In Social Computing and Social Media. Communication and Social Communities, 11th International Conference, SCSM 2019, Held as Part of the 21st HCI International Conference, HCII 2019, Orlando, FL, USA, Vol. 11579, 251–267. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-21905-5_20.

- Altheide, David L. 1987. “Reflections: Ethnographic Content Analysis.” Qualitative Sociology 10 (1): 65–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00988269.

- Altheide, David L., and John Johnson. 1994. “Criteria for Assessing Interpretive Validity in Qualitative Research.” In Handbook of Qualitative Research, edited by N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln, 485–499. London, England: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Audrezet, Alice, Gwarlann De Kerviler, and Julie Guidry Moulard. 2020. “Authenticity under Threat: When Social Media Influencers Need to Go beyond Self-Presentation.” Journal of Business Research 117: 557–569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.07.008.

- Bainotti, Lucia, Alessandro Caliandro, and Alessandro Gandini. 2021. “From Archive Cultures to Ephemeral Content, and Back: Studying Instagram Stories with Digital Methods.” New Media & Society 23 (12): 3656–3676. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820960071.

- Boerman, Sophie C., and Céline M. Müller. 2022. “Understanding Which Cues People Use to Identify Influencer Marketing on Instagram: An Eye Tracking Study and Experiment.” International Journal of Advertising 41 (1): 6–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2021.1986256.

- Borchers, Nils S., and Nadja Enke. 2022. “I’ve Never Seen a Client Say: ‘Tell the Influencer Not to Label This as Sponsored’: An Exploration into Influencer Industry Ethics.” Public Relations Review 48 (5): 102235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2022.102235.

- Britt, Rebecca K., Jameson L. Hayes, Brian C. Britt, and Haseon Park. 2020. “Too Big to Sell? A Computational Analysis of Network and Content Characteristics among Mega and Micro Beauty and Fashion Social Media Influencers.” Journal of Interactive Advertising 20 (2): 111–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2020.1763873.

- Caldeira, Sofia P., Sofie Van Bauwel, and Sander De Ridder. 2021. “Photographable Femininities in Women’s Magazines and on Instagram.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 25 (1): 79–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/13675494211003197.

- Campbell, Colin, and Justine Rapp Farrell. 2020. “More than Meets the Eye: The Functional Components Underlying Influencer Marketing.” Business Horizons 63 (4): 469–479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2020.03.003.

- Campbell, Colin, and Pamela Grimm. 2019. “The Challenges Native Advertising Poses: Exploring Potential Federal Trade Commission Responses and Identifying Research Needs.” Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 38 (1): 110–123.

- Casaló, Luis V., Carlos Flavián, and Sergio Ibáñez-Sánchez. 2020. “Influencers on Instagram: Antecedents and Consequences of Opinion Leadership.” Journal of Business Research 117: 510–519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.07.005.

- Domingues Aguiar, Tatiana, and Eva A. van Reijmersdal. 2018. Influencer Marketing. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: SWOCC.

- De Veirman, Marijke, Veroline Cauberghe, and Liselot Hudders. 2017. “Marketing through Instagram Influencers: The Impact of Number of Followers and Product Divergence on Brand Attitude.” International Journal of Advertising 36 (5): 798–828. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2017.1348035.

- Djafarova, Elmira, and Tamar Bowes. 2021. “‘Instagram Made Me Buy It’: Generation Z Impulse Purchases in Fashion Industry.” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 59 (mars): 102345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102345.

- Djafarova, Elmira, and Chloe Rushworth. 2017. “Exploring the Credibility of Online Celebrities’ Instagram Profiles in Influencing the Purchase Decisions of Young Female Users.” Computers in Human Behavior 68 (mars): 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.009.

- Gross, Jana, and Florian Von Wangenheim. 2022. “Influencer Marketing on Instagram: Empirical Research on Social Media Engagement with Sponsored Posts.” Journal of Interactive Advertising 22 (3): 289–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2022.2123724.

- Giuffredi-Kähr, Andrea, Alisa Petrova, and Lucia Malär. 2022. “Sponsorship Disclosure of Influencers—A Curse or a Blessing?” Journal of Interactive Marketing 57 (1): 18–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/10949968221075686.

- Hidarto, Anderson. 2021. “The Persuasive Language of Online Advertisements Featuring Social Media Influencers on Instagram: A Multimodal Analysis.” Indonesian JELT: Indonesian Journal of English Language Teaching 16 (1): 15–36. https://doi.org/10.25170/ijelt.v16i1.2550.

- Hogsnes, Mathilde, Tor-Morten Grønli, and Kjeld Hansen. 2023. “Unconsciously Influential. Understanding Sociotechnical Influence on Social Media.” Scandinavian Journal of Information Systems 35 (2): 1.

- Hudders, Liselot, Steffi De Jans, and Marijke De Veirman. 2020. “The Commercialization of Social Media Stars: A Literature Review and Conceptual Framework on the Strategic Use of Social Media Influencers.” International Journal of Advertising 40 (3): 327–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2020.1836925.

- Instagram. 2023. “Instagram Business.” https://business.instagram.com

- Inzpire.me 2021. “The Platform to Scale Influencer Marketing.” https://inzpire.me/.

- Jorge, Ana, Lidia Marôpo, and Thays Nunes. 2018. “‘I Am Not Being Sponsored to Say This’: A Teen Youtuber and Her Audience Negotiate Branded Content.” Observatorio (OBS*) 12:76–96. https://doi.org/10.15847/obsOBS0001382.

- Karagür, Zeynep, Jan-Michael Becker, Kristina Klein, and Alexander Edeling. 2022. “How, Why, and When Disclosure Type Matters for Influencer Marketing.” International Journal of Research in Marketing 39 (2): 313–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2021.09.006.

- Kay, Samantha, Rory Mulcahy, and Joy Parkinson. 2020. “When Less Is More: The Impact of Macro and Micro Social Media Influencers’ Disclosure.” Journal of Marketing Management 36 (3-4): 248–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2020.1718740.

- Klear. 2021. “Find Creators Your Audience Trust.” https://klear.com/.

- Kowalczyk, Christine M., and Kathrynn R. Pounders. 2016. “Transforming Celebrities through Social Media: The Role of Authenticity and Emotional Attachment.” Journal of Product & Brand Management 25 (4): 345–356. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-09-2015-0969.

- Lin, Hsin-Chen, Patrick F. Bruning, and Hepsi Swarna. 2018. “Using Online Opinion Leaders to Promote the Hedonic and Utilitarian Value of Products and Services.” Business Horizons 61 (3): 431–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2018.01.010.

- Lou, Chen, and Shupei Yuan. 2019. “Influencer Marketing: How Message Value and Credibility Affect Consumer Trust of Branded Content on Social Media.” Journal of Interactive Advertising 19 (1): 58–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2018.1533501.

- Martínez-López, Francisco J., Rafael Anaya-Sánchez, Marisel Fernández Giordano, and David Lopez-Lopez. 2020. “Behind Influencer Marketing: Key Marketing Decisions and Their Effects on Followers’ Responses.” Journal of Marketing Management 36 (7-8): 579–607. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2020.1738525.

- Merriam Webster Dictionary. 2024. “commercial.” https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/commercial.

- Park, Jiwoon, Ji Min Lee, Vikki Yiqi Xiong, Felix Septianto, and Yuri Seo. 2021. “David and Goliath: When and Why Micro-Influencers Are More Persuasive Than Mega-Influencers.” Journal of Advertising 50 (5): 584–602. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2021.1980470.

- Rose, Gillian. 2014. “On the Relation between ‘Visual Research Methods’ and Contemporary Visual Culture.” The Sociological Review 62 (1): 24–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-954X.12109.

- Rundin, Ksenia, and Jonas Colliander. 2021. “Multifaceted Influencers: Toward a New Typology for Influencer Roles in Advertising.” Journal of Advertising 50 (5): 548–564. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2021.1980471.

- Statista. 2021. “Share of Online Shoppers Who Have Made a Purchase via SM the Past Six Months in Selected Countries Worldwide in 2020, by Age Group.” https://www.statista.com/statistics/1192455/share-of-people-who-purchased-goods-on-social- media-by-age-group

- Statista. 2023. “Influencer Marketing Worldwide—Statistics & Facts.” https://www.statista.com/topics/2496/influence-marketing/#topicOverview

- Strauss, Anselm, and Juliet Corbin. 1998. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Sikt. 2024. “The Norwegian Knowledge Sector’s Service Provider.” Conducting research anonymously. Accessed June 1, 2021. https://sikt.no/tjenester/personverntjenester-forskning/personvernhandbok-forskning/gjennomfore-et-prosjekt-uten-behandle-personopplysninger

- Tafesse, Wondwesen, and Bronwyn P. Wood. 2021. “Followers’ Engagement with Instagram Influencers: The Role of Influencers’ Content and Engagement Strategy.” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 58:102303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102303.

- Vanninen, Heini, Joel Mero, and Eveliina Kantamaa. 2023. “Social Media Influencers as Mediators of Commercial Messages.” Journal of Internet Commerce 22 (sup1): S4–S27. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332861.2022.2096399.

- Voorveld, Hilde A. M., Guda Van Noort, Daniël G. Muntinga, and Fred Bronner. 2018. “Engagement with Social Media and Social Media Advertising: The Differentiating Role of Platform Type.” Journal of Advertising 47 (1): 38–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2017.1405754.

- Vrontis, Demetris, Anna Makrides, Michael Christofi, and Alkis Thrassou. 2021. “Social Media Influencer Marketing: A Systematic Review, Integrative Framework and Future Research Agenda.” International Journal of Consumer Studies 45 (4): 617–644. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12647.

- Zarei, Koosha, Damilola Ibosiola, Reza Farahbakhsh, Zafar Gilani, Kiran Garimella, Noel Crespi, and Gareth Tyson. 2020. “Characterising and Detecting Sponsored Influencer Posts on Instagram.” In 2020 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining (ASONAM), 327–331. The Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1109/ASONAM49781.2020.9381309.