Abstract

The main aim of this study is to investigate how political strategies (issue ownership, issue trespassing, and issue extremeness) and communication styles (responsiveness and mobilization) affect political candidates’ ability to trigger other users’ engagement (in terms of likes and retweets) as well as traditional media attention (in terms of news articles and of the proportion of media-related followers). Theoretically, the study links these strategies and communication styles within the framework of a single research and to expand these concepts to the social media realm. To do so, we rely on Swiss political candidates’ tweets over the course of the 2019 national election campaign while also integrating newspaper articles about these candidates. Combining political strategies with different styles of communication within the framework of a single study enables us to better understand the dynamics of public and media attention within political communication. Findings demonstrate a certain dose of media interconnection and highlight the specificities of Twitter in terms of communicative behaviors from media-related accounts and how they compare to offline media coverage. Practically, the study highlights what are best communication practices for political actors, especially which strategies and communications styles are more likely to generate other users’ engagement and media attention.

Introduction

Communication about policy issues is taking place in a hybrid and digital media environment and social media platforms constitute pillars of this political communication (Lilleker, Tenscher, and Štětka Citation2015). Through these platforms, political actors can not only take the pulse of societal concerns (McGregor Citation2020), but can also conduct campaigns about policy issues and influence public opinion (Stier et al. Citation2018). The present study focuses on the extent to which different political candidates’ strategic tweeting and communication styles affect the online and offline visibility of Swiss political actors during an election campaign. The frequent submission of proposals to a popular vote makes Switzerland an interesting case to study political communication on social media, as political campaigning is almost permanent, notably due to the frequent direct democratic votes. To date, doubts persist about social media’s influence and effect on political debates (Klinger and Russmann Citation2017). The focus of this study is on the use of social media by political and media actors, which is in line with the fact that Swiss public debate (and the public opinion formation) remains strongly shaped by the political elite (Kriesi Citation2005). In this study, the social media platform on which we are basing our research is Twitter, which can be considered more of a network for professional users, particularly journalists and politicians (Kovic et al. Citation2017).

Political actors’ performance on social media has been conceptualized in various dimensions, such as those of user engagement and follower numbers (i.e., Spierings and Jacobs Citation2019). However, the role of social media in the equalization (i.e., reinforcement of power relationships) versus the normalization (i.e., leveling of power relationships) of power dynamics between major and minor political actors constitutes an ongoing debate (i.e., Bene Citation2023; Fischer and Gilardi Citation2023). The present study aims to contribute to this debate by investigating how different political strategies and communication styles adopted by political actors on Twitter enable them to trigger other users’ engagement during the 2019 federal election campaigns.

Although politicians’ involvement on social media does not convincingly allow them to gain more votes during elections (Bright et al. 2019), studies have shown that social media do enable politicians to gain access to traditional media coverage (i.e., Howard Citation2006; Nielsen Citation2012; Reveilhac and Morselli Citation2023). The fact that journalists report on politicians’ social media messages and activities (McGregor Citation2019) contributes to exposing citizens to political social media content (Fletcher and Nielsen Citation2018) in addition to traditional media, which used to be hegemonic in the treatment and filtering of (political) information. Drawing from the existence of an interconnexion between social media and traditional media (i.e., Karlsen and Enjolras Citation2016; Harder, Sevenans, and Van Citation2017), the present study aims to improve our understanding of which political strategies and communication styles are linked to increased (offline and online) media attention.

Concerning political strategies, previous studies have demonstrated that social media enable politicians not only to spread their party agenda, but also to defend their own views, thus detaching from the party line (Ennser-Jedenastik et al. Citation2022). In the first strategy, politicians selectively emphasize policy issues, thus accentuating their competence surrounding policy issues on which their party has built a reputation (Schröder and Stecker Citation2018). The second strategy suggests that politicians bypass the framework of the party agenda (Peeters, Van Aelst, and Praet Citation2021). They can do so by “trespassing” on issues that are not central to the party agenda or by adopting an “issue extremeness” behavior to distinguish themselves from the party’s general communication agenda. To date, there is little evidence of which strategy pays off in terms of attracting public and media attention and few studies have combined these strategies into a single research project (Eberl et al. Citation2020; Stier et al. Citation2018).

Styles of political communication have been shown to play a role in triggering public engagement on social media. For instance, one such element is a mobilizing style of communication, such as persuading other users to act or to participate in polls (Keller and Kleinen-von Königslöw Citation2018b). Furthermore, adopting a responsive behavior on social media (i.e., by replying to other users) can also lead to more effective communication by being perceived as being more responsive to public concerns (Ennser-Jedenastik et al. Citation2022). However, there is little evidence that adopting an interactive style is the most effective way to gain votes (Bright et al. 2019). Previous research provides insights into how these different communication styles could lead to more engagements from other online users (Heiss, Schmuck, and Matthes Citation2019), especially in the context of populist rhetoric (Ernst et al. Citation2019) and in the context of political campaigns (Keller and Kleinen-von Königslöw Citation2018a), but the effect of political styles has not (to the best of our knowledge) been investigated in relation to the (online and offline) media attention received by political actors.

Literature Review

Political Actors’ Online and Offline Visibility

Research about the emergence of communities around political candidates on social media (Bode and Dalrymple Citation2016) has especially focused on how specific behavioral measures – such as retweets (when tweets are reposted by other users) and likes (also called favorites until November 2015) – give an indication of the influence that politicians can achieve. These behaviors provide options for users to give feedback about the political messages they perceive as relevant. These reactions, in turn, enable politicians to evaluate the arguments that are better for communicating their position (Keller and Kleinen-von Königslöw Citation2018a). These reactions allow politicians’ messages to be noticed and spread throughout networks beyond their direct following and, thereby, to differentiate their communication from other public messages (Klinger and Svensson Citation2015). Although social media users do not generally reflect the characteristics of the wider public, they do form an ideal population with which politicians can communicate, notably because they tend to be very interested in politics, are likely to turn out at the polls, and are willing to contribute to campaigns (Bode and Dalrymple Citation2016). Therefore, the first research question is looking at how political actors can increase online public attention and reads as: which communication strategies and styles used by political actors are associated with increased levels of online engagement by other users?

Political actors’ messages on social media may not only be seen by other users (i.e., their followers or users interested in politics), but can also be seen by non-users through traditional media channels. Indeed, political candidates who are influential on social media can also generate attention and visibility on traditional media (Karlsen and Enjolras Citation2016). Social media is part of the “hybrid political communication system” (see Chadwick Citation2013) used by politicians, thus suggesting a certain degree of media interconnection where a single tweet might trigger traditional media attention (Harder, Sevenans, and Van Citation2017). For instance, social media offer an important channel for signaling politicians’ specialization to journalists, to their electorate, and to the wider public (Van Aelst, Sheafer, and Stanyer Citation2012), and this specialization tends to allow politicians to trigger the attention of traditional media (Van Camp Citation2017). Overall, there is a certain overlap of media interdependence where politicians’ visibility on social media can impact their offline visibility in traditional media, and vice versa (Kruikemeier, Gattermann, and Vliegenthart Citation2018). The number of followers is typically used to gauge the influence (or popularity) of political actors on social media (Cha et al. Citation2010; Keller and Kleinen-von Königslöw Citation2018a). However, this measure is criticized because it might not equate to influence as it depends on a minority of very active followers (Fischer and Gilardi Citation2023). Since few general voters follow and interact with politicians on Twitter (Keller Citation2020), it is important to understand what criteria have an impact on the decision of journalists (and other media accounts) to circulate and spread social media political information. In this respect, the share of media accounts following political actors is an important indicator of (online) media visibility which, in turn, may enable politicians to gain access to traditional media coverage and, thereby, influence the formation of public opinion. Therefore, the second research question is looking at how political actors can increase media attention and reads as: which communication strategies and styles used by political actors are associated with increased levels of media attention on social media and in traditional media?

Political Strategies: Issue Ownership, Issue Trespassing and Issue Extremeness

The focus of this study is on how strategic tweeting and communication styles impact political actors’ online (i.e., other users’ engagement and the share of media followers) and offline (i.e., traditional media coverage) visibility. This study focuses on several political communication strategies.

Issue Ownership

The issue ownership theory in Petrocik (Citation1996) claims that parties can own certain policy issues. In other words, people believe that some issues are owned by given parties, thus suggesting that parties tend to be better able than others to handle specific issues. Therefore, researchers have provided explanations of how issue ownership develops over time and may result in more votes for parties (Walgrave, Lefevere, and Tresch Citation2012; Thesen, Green-Pedersen, and Mortensen Citation2017). Furthermore, the media coverage of policy issues in relation to specific parties also points to a certain degree of issue ownership (Tresch and Feddersen Citation2019; Gilardi et al. Citation2021). At the level of individual politicians, it can be expected that addressing issues on which their party has a strong stance also translates into a vote for them. In this view, politicians would be strongly incentivized to adopt the party line to augment their own chances of reelection (Carey Citation2009). These political strategies were initially studied offline with parliamentary data (i.e., roll-call data). However, social media discussions and Parliamentary debates have quite different conventional influences on political communication (Van Dalen et al. Citation2015). The issue ownership strategy has been investigated through multiple channels of communication. The extent to which issue ownership is a prevalent online strategy is essential to understand the role of social media in the contemporary public opinion formation (Praet et al. Citation2021). For instance, Sandberg (Citation2022) showed that issue ownership as measured in representative surveys correlates with issues parties are associated with on Twitter, although deviations might reflect changes in issue competition. Based on survey experiments in Germany and Switzerland, Giger et al. (Citation2021) further showed that citizens are more interested in politicians’ social messages conveying policy positions, instead of more personalized communication (such as messages about private life). Furthermore, Peeters, Van Aelst, and Praet (Citation2021) focused on the dynamics of political opinions and compared politicians’ agendas on Twitter, in the news, and in parliament. They concluded that politicians’ issue agendas are driven by their personal specialization. However the authors demonstrate that, on Twitter, issue specialization and issue ownership are not necessarily mutually exclusive, as the effect of issue ownership varies across policy issues. Moreover, Van Camp (Citation2017) showed that specialization has a positive effect on politicians’ chances of getting into traditional media, thus leading to more media visibility. Based on these recent findings, we expect that political actors’ reliance on issue ownership will have a positive influence on the amount of other users’ reactions (H1) and a positive impact on media attention (both in terms of media followers and traditional media coverage) (H2).

Issue Trespassing

Another strand of research focuses the issue agenda of individual politicians (Vos Citation2016; Peeters, Van Aelst, and Praet Citation2021). This represents an important endeavor given the steadily increasing personalization of politics in the offline (i.e., Rahat and Sheafer Citation2007) and online realms (i.e., Holtz-Bacha 2014; Graham, Jackson, and Broersma Citation2017). The general logic is that, to get (re-)elected, politicians also need to compete with politicians from their own party. For instance, Bräuninger, Brunner, and Däubler (Citation2012) demonstrates that multiparty systems tend to encourage politicians to adopt personal vote-seeking strategies because of the flexibility of party lists. This issue trespassing strategy suggests that politicians must go beyond the ideology and issue positions of other politicians within their own party. Politicians can thus focus on issues that are not necessarily owned by their party (Tresch Citation2009). Early work on political campaign dynamics showed that issue trespassing can also be perceived as a part of a normal campaign strategy by enabling politicians to appeal to a broader electorate (Downs Citation1957, 135; Damore Citation2004). Politicians may thus be incentivized to associate themselves with concerns which are salient for the public and already addressed by their political opponents (Aldrich and Griffin Citation2003, 247). Furthermore, this strategy is also referred to as “riding the wave” (Sides Citation2006), as currently relevant issues will appear in public debate, thereby leading to a dispersion of the political agenda, which is likely to be facilitated by social media serving as “a substitute channel for political communication, circumventing partisan, and institutional constraints” (Castanho Silva and Proksch Citation2022, 2). However, traditional news media should be more likely to invite politicians whose positions on policy issues are credible and who have high levels of expertise (Van Camp Citation2017). Based on these recent findings, we expect that political actors’ reliance on issue trespassing will have both a positive influence on the amount of other users’ reactions (H3) and a negative impact on media attention (H4).

Issue Extremeness

Politicians may also choose to differentiate themselves from their party by adopting more extreme positions on certain policy issues. This translates into a more extreme positioning on certain policy issues in comparison to that of the party from which the politicians are stemming (Rauh, Bes, and Schoonvelde Citation2020). Politicians could be tempted to express more extreme positions online as they perceive that there is an incentive (i.e., internal party disagreement) to use social media to personalize their message (Ceron Citation2017). Previous studies have investigated the effects of emotionality in terms of communication style or use of emoticons (Stieglitz and Dang-Xuan Citation2013). As extreme positions might become directly observable through social media (and lead to political rivalries and scandals), we expect that political extremeness will have a positive influence on the amount of other users’ reactions (H5) and a positive impact on media attention (H6).

Communication Styles: Mobilization and Responsiveness

In addition to the content of political messages, it is important to consider the style of communication. In this study, we focus on two communication styles:

Mobilization

The introduction of social media has changed the perspective on political mobilization (Karlsen Citation2013), especially in relation to individual candidates’ use of this technology to generate preference voting (Spierings and Jacobs Citation2014). Karlsen and Enjolras (Citation2016) found that creating involvement and mobilizing supporters is central to the party-centered communication dimension. For politicians, a mobilizing social media message can aim to reinforce citizens’ willingness to participate in an election (Vissers and Stolle Citation2014; Keller and Kleinen-von Königslöw Citation2018a), which is comparable to “traditional get-out-the-vote tactics” (Teresi and Michelson Citation2015). Furthermore, Yu et al. (Citation2021) demonstrated that distinct levels of social media involvement by politicians can lead to the over-representations of some topics and “calls for action.” However, the potential influence of the direct mobilization mechanism on social media might depend, at least partly, on the extent to which politicians are seen as being responsive to individual voters (Koc-Michalska et al. Citation2016). More generally, the mobilization potential of social media might also depend on whether calls can meet a large audience (i.e., not only the most active followers), and, thereby, echo the opinions that are salient in society (Baik, Nyein, and Modrek 2020; Reveilhac and Eisner Citation2022). Therefore, we expect that political mobilization will have a positive influence on the amount of other users’ reactions (H7) but have a negative impact on media attention (H8).

Responsiveness

Graham et al. (Citation2013) classify a social media post in terms of whether it is simply a broadcasted message (i.e., reporting on activities or giving a viewpoint) or whether it involves some sort of interaction (i.e., a reply to another user). Empirical research has consistently offered the critique that politicians engage with Twitter in a style that is more about broadcasting and less about making use of its interactive features (Jungherr Citation2016). However, the level of politicians’ interactions on social media differs significantly across parties (Jacobs and Spierings Citation2019), and Bright et al. (2019) have challenged the hypothesis that adopting an interactive style is the most effective method of social media campaigning, especially in relation to offline political success (in terms of winning votes). Nevertheless, there is also some level of reciprocity between politicians’ responsiveness and public attention. For instance, Ennser-Jedenastik et al. (Citation2022) demonstrated that political elites make use of social media as a channel to learn about voters’ concerns to enhance issue responsiveness. Tromble (Citation2018) further showed that citizen demand can, to some extent, determine the level of politicians’ reciprocal engagement. Therefore, we expect that political responsiveness will have a positive influence on the amount of other users’ reactions (H9) and a positive impact on media attention (H10).

Specificity of the Swiss Case

We conducted our research in the framework of the Swiss 2019 election campaign. Switzerland is a latecomer to the modernization of political campaigns. During the last election of 2015, only a few political candidates relied on social media. However, in the last election of 2019, candidates took part in more active digital campaigning than previously seen (Bernhard Citation2020). Swiss politicians put social media to a more personal use, such as that of seeking political information and for entertainment purposes (Hoffmann and Suphan Citation2017). Selb and Lutz (Citation2015) demonstrated that candidates’ campaigning behavior during the 2015 election was strongly related to intraparty competition. Indeed, in an open ballot proportional system such as Switzerland’s, being elected does not so much depend on beating candidates from other parties but on winning against politicians from the same electoral list. The 2019 election campaign was marked by an unusual attention to environmental and gender issues, which prompted parties and politicians to redefine their positions (Gilardi et al. Citation2021), and thus perhaps leading to an increased effectiveness in their individualized campaigning strategies.

Data and Method

Tweets Emitted by Political Candidates, Public Opinion Surveys, and News Media Articles

We analyzed 626 political candidates from the eight main parties represented in the Swiss Parliament. The period of analysis covers the eight months before the federal election, running from January 2019 until October 21st, 2019. All tweets emitted by candidates in this period were collected. In conducting our analyses, we selected only original tweets (including replies). We did not consider retweets which were not related to how a politician would communicate about a policy issue or a campaign aspect and which were almost identical to the language of the original poster (Jensen Citation2017).

We also relied on public opinion survey data to measure public perceptions of policy issue ownership. We used the Swiss Election Study Selects,Footnote1 which was conducted in three waves from May to December 2019 and which studied the evolution of opinion and vote intention (or choice) during the distinct phases of the election cycle. We chose to rely only on the first wave of the panel’s study to obtain pre-electoral public perceptions on issue ownership.

To assess the level of media coverage received by each politician, we also relied on a database of news media articles collected during the election campaign. The articles were coded for mentions of candidates by the Selects team.

Statistical Analyses and Dependent Variables

The dependent variables of our study are the number of instances of other users’ engagement (in terms of retweets and likes), the proportion of media followers, and the amount of media coverage (in terms of news articles) triggered by politicians. These measures are thus aggregated for politicians. Just note that, although the number of followers does not reflect direct user reactions to specific content, we account for the number of media followers as this is an essential factor to show the interconnection between the contemporary political and media agendas.

In the first analytical step, we investigated how the dependent variables correlate with one another to assess the degree of media interrelation. In a second analytical step, we conducted different regression models to assess the impact of our independent and control variables on our dependent variables. Given the skewed distribution of our dependent variables (with the variance being significantly different from the mean and over-representation of zeros), we relied on negative binomial regression models for the dependent variables using the function glm.nb from the R package MASS.

Independent Variables: Political Communication Strategies

Issue Ownership

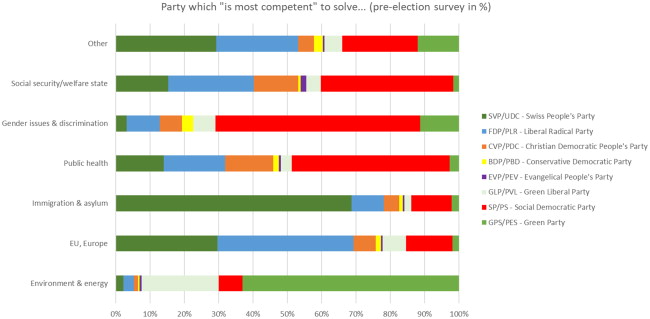

Issue ownership was operationalized by using an item in a survey where citizens were asked which party they thought was the most competent to handle the policy issue that they perceived as being the “most important concern” during the preelection period as measured in the Selects 2019 Panel Survey.Footnote2 In contrast to the “most competent” item, the perceived party’s “care” about an item/topic was asked for on only a sample of policy issues (European integration, economy, environment, and migration). Including only these four policy issues would have masked other policy issues that were salient during the election campaign, most notably gender and public health related issues. We thus focused on a measure of perceived competence of issue ownership, as opposed to on associative issue ownership (Walgrave, Lefevere, and Tresch Citation2012). Based on these results, we calculated the percentage of tweets that each politician dedicated to the issues for which their party was perceived as being the most competent. Appendix A shows the percentage of respondents that linked party competence with the policy issue they perceived as being the most important (only the six main policy issues are displayed for illustration purposes). Appendix C describes the complete coding.

Issue Trespassing

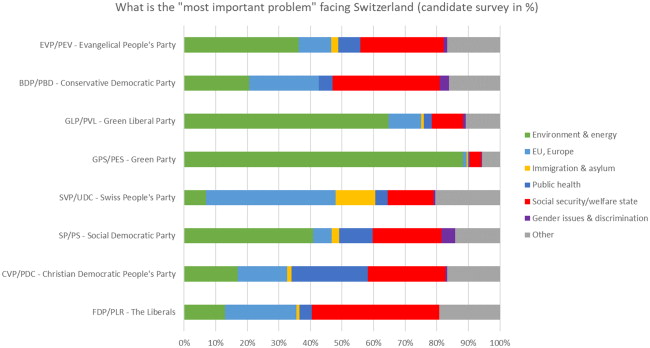

Issue trespassing is operationalized as the proportion of tweets emitted by each politician which concerned issues not primarily at the core of the party agenda. Doing so enabled us to model to what extent issue trespassing was used by each politician. We considered the responses given to the Selects 2019 Candidate Survey by the participating Swiss political candidates of the 2019 elections.Footnote3 Politicians were perceived as trespassing on issues if less than 3% of the political candidates participating in the survey and having the same political affiliation mentioned that particular issue as being one of the most important concerns for the party. Therefore, we were also able to account for the fact that some issues, such as the environment, were salient for every party, and thus could be considered as “riding-the-wave” issues during the election. Appendix B illustrates only the six main policy issues that were perceived as being the “most important problem” across the partisan affiliations of the politicians. Appendix C describes the complete coding.

Issue Extremeness

Issue extremeness is operationalized with a cosine similarity measure as implemented in the stringdist package from the R programming language (van der Loo et al. Citation2021). To model extremeness, we subtracted the cosine distance to 1 (1-cosine) to have a measure of difference instead of similarity. This measure was done for every policy issue discussed by a politician in comparison to how the same issue was discussed by politicians of the same party. Higher differences indicated an increased level of extremeness on the issue.Footnote4 Before conducting the cosine analysis, we maximized similarity between the tweets by lemmatizing the text (with the udpipe package from Wijffels, Straka, and Straková Citation2019) and by keeping only specific features (namely, nouns, verbs, adverbs, and adjective) in the text. This enabled us to have a more precise measure of dissimilarity. We differentiated issue extremeness between “owned” and “unowned” policy issues.

Mobilization

We conducted keyword filtering to identify the mobilization language (see also Kligler-Vilenchik and Literat Citation2018 for use of a keyword analytical strategy). The relevance of the keywords that we used was determined by a cosine similarity analysis to the words “demonstration” and “mobilization” in our corpus of tweets and by a close-reading of the closest word candidates selected by the similarity analysis. For each candidate, we assessed the percentage of tweets related to the mobilization of citizens that matched at least one of the keywords. The final list of keywords is shown in Appendix D.

Responsiveness

Responsiveness is based on politicians’ replying patterns on Twitter. In general, politicians in our sample rarely used the reply function on Twitter. However, being responsive to public concerns implies engagement in discussions outside of the party boundaries. Therefore, the responsiveness score captures only replies from politicians made to other users, to politicians from another party, and to a media account.

Control Variables

Activity on Twitter

The account creation date (which is indicative of the longevity of a social media account) and activity are likely to predict the number of reactions politicians receive (Keller and Kleinen-von Königslöw Citation2018a). Therefore, we specified the number of days that had passed since the Twitter account creation date for each politician. Furthermore, the activity rate describes the number of tweets per day during the campaigning period.

Political Characteristics

We controlled for the partisan leaning of each politician by including their political affiliation. We also included a variable indicating whether the politician was an incumbent or a new candidate. In addition, we specified for which parliamentary chamber a candidate was competing, namely for the Council of States or for the National Council.

Sociodemographics

We also assumed that offline and online visibility could be predicted by a set of personal characteristics. We focused on gender because it has been shown to remain a key factor in the prediction of political attention. Furthermore, the gender factor had a particular effect on the Swiss electoral system in 2019, which saw a surge in women’s representation (Bernhard Citation2020), a trend that could be explained by women’s mobilization during June 2019.

Dictionary Approach to Identify Policy Issues in Tweets

To classify each tweet into policy issue categories, we automatically coded all of our recorded data using a custom policy issue dictionary. Our dictionary was inspired by the open-ended answers to the “most important concern” item from the Selects electoral studies. The full methodology is explained in Appendix E.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

displays the descriptive statistics of the variables included in the analyses. It shows that politicians triggered on average 1,042 reactions (retweets and likes) from other users, with a median situated at 84. Politicians generated on average 171 news articles, with a median situated at 14 news articles. Some politicians (20, 32%) did not trigger any news articles. Furthermore, politicians’ followership was on average composed of 8% of media-related accounts (44, 6% of politicians had no media-related followers). With respect to the independent variables, politicians were, on average, using social media less often to address issues that were owned by their party than to trespass on issues (27% issue ownership versus 40% issue trespassing). Issue extremeness was generally high on “owned” and “unowned” issues, but the minimum value indicates that extremeness was lower for “owned” issues than for “unowned” issues. Politicians’ style of communication consisted of an average of 31% of replies and of 10% of mobilization-related tweets. Regarding the control variables, we noted that a politician’s party affiliation was slightly biased toward the left, with left-oriented parties using Twitter more than politicians from right-leaning parties. This bias is especially visible when compared with the “true” party representation in the last column of . Furthermore, there were more new candidates than incumbents in our samples, and most candidates ran for the National council. We also had more male than female candidates.

Correlation of the Attention and Coverage Measures

We calculated the correlations between the dependent variables. We obtained results demonstrating that candidates who had higher levels of online attention in terms of social media attention also had higher levels of news media coverage (0.30 Pearson correlation with a p-value < 0.001). This finding is in line with that of previous studies highlighting the role of journalists in contributing to the increase in the spread of politicians’ messages, especially by referring to these messages in traditional media (McGregor Citation2019). Furthermore, the proportion of followers that were media-related is negatively related to social media attention (−0.08 with p-value < 0.01).

Multivariate Regressions: Main Findings

To analyze the predictors of our dependent variables, we ran negative binomial regressions for predicting other users’ engagement (Model 1), the proportion of media followers (Model 2), and amount of traditional media coverage (Model 3). For each model, we added the dependent variables as explanatory factors in view of modeling the media interrelation underlined by the literature. Results for the regressions are shown in .

Results demonstrate that issue ownership is positively and significatively related to the dependent variable in relation to the amount of social media attention garnered (H1 accepted). However, issue ownership is not significantly associated with media attention, neither in terms of the proportion of media followers nor in terms of the number of traditional media articles generated (H2 rejected). This finding echoes the literature conceiving politicians’ social media use as a substitute rather than as an amplifier of the official party agenda (Castanho Silva and Proksch 2021). This can also be explained by the fact that Twitter conversations are event driven. In this sense, a candidate sticking to the party agenda without discussing the current state-of-affairs might be perceived as being less responsive to public concerns and, thereby, less likely to receive the media’s attention.

Issue trespassing is significantly and positively related to the amount of social media attention garnered (H3 accepted). However, while it is negatively related to media coverage (H4 accepted), it is also positively related to the proportion of media followers (H4 rejected). This finding could be explained by the fact that different media logics apply online and offline to decide what content is “newsworthy.” For instance, a higher proportion of media followership could be linked to the propensity of a politician to differentiate from the party agenda, a trend that would be in line with the personalization of politics (Grazia et al. Citation2023). However, to make it to the news, politicians need to not trespass the party agenda.

Issue extremeness is positively related to other users’ attention, but only when it is expressed on unowned policy issues (H5 partly accepted). However, the issue of extremeness has no significant relationship with media attention (H6 rejected), neither online nor offline, thus providing little evidence that the media promotes information about intra-party heterogeneity. This finding is understandable in the Swiss case where there is a long tradition of consensual politics (Vatter Citation2016). In that sense, a lower level of personalization reflects a more consensual style of politics, which is also more appreciated by the media culture.

Turning to communication styles, results show that a higher proportion of mobilization tweets is statistically and positively related to other users’ attention (H7 accepted). However, while it is positively associated with the proportion of media followers, it is not related to the amount of traditional media coverage (H8 partially accepted). Concerning responsiveness, results also show that an increased proportion of replies to other users is not significatively related to the amount of other users’ attention (H9 rejected) and is negatively associated with media attention (H10 rejected). Although responding to citizens on these platforms could lead to improved politician images (Tromble Citation2018), citizens are rarely used to receiving direct responses and, therefore, are not likely to sanction politicians for adopting a unidirectional (top-down) communication style. The descriptive statistics in also suggest that politicians do not frequently engage in responding to other users, which could be explained by time constraints and by fear of losing control (Kalsnes Citation2016). Furthermore, the fact that responsiveness was even negatively associated with a higher proportion of media followers could suggest that media followers are mostly interested in political actors that speak explicitly about the policy positions instead of adopting a more indirect (or even defensive) posture.

While the Swiss case has merits for the study of political communication, the obtained results suggest that its political system could explain most of the rejected hypotheses (see for a summary of the hypotheses). Indeed, the long tradition of consensual style politics, where all major parties are represented in government and where direct democracy provides incentives to find consensual policy decisions.

Multivariate Regression: Additional Findings

We also investigated the interrelations between politicians’ online and offline attention. The variables linked to media interrelation demonstrate that a higher media coverage is negatively, but not significatively, associated with social media attention (Model 1) and with a higher proportion of media followers (Model 2). Furthermore, a higher level of social media attention is positively, albeit barely significatively, related to media coverage (Model 3). However, a higher proportion of media followers is strongly and positively associated with increased media coverage (Model 3).

In Model 1, the control variables indicate that politicians from rightist and centrist parties received on average fewer other users’ attention than politicians from the Green Party. Furthermore, new candidates were less likely to trigger online attention than political incumbents. Politicians who possessed a Twitter account for a long time who were highly active on Twitter during the campaign were also likely to trigger social media attention. In addition, women candidates were more likely than men to generate social media attention.

In Model 2, politicians who had a high proportion of media-related accounts were competing for the Council of the States (rather than the National Council). Furthermore, politicians who had a higher proportion of media followers were generally incumbent rather than new candidates. In addition, politicians from the Green Liberals were comparatively less followed by media accounts compared to politicians from the Green Party.

Concerning the media coverage in Model 3, politicians competing for the Council of States were more covered by the news media compared to candidates for the National Council. Political incumbents also received more media attention (both in terms of media followers and media coverage). Finally, the increased level of posting activity on Twitter triggered more media attention.

Concluding Remarks

This section includes a discussion of the study’s implications for theory and practice, of the study’s limitations, and offers an agenda for future research.

The main theoretical contribution of this study is to demonstrate how well-known political strategies (issue ownership, issue trespassing and issue extremeness) and communication styles (responsiveness and mobilization) impact politicians’ online attention (social media attention and offline media coverage). This study raises the question of how well-established political strategies and communication styles can be linked to online and offline public and media attention. Results demonstrate that political actors can trigger most public and media attention by emphasizing topics that are owned by their party (issue ownership) instead of by adopting more individualist and extreme views. That said, it can be expected that these results are heavily influenced by the Swiss political system which has a long traditional of consensual policy making. However, results also highlight differences in the online and offline media logics, where issue trespassing generated increased media followership but did not translate into increased media coverage. This could also be explained by the organization of the traditional press, which is looking to showcase expert views on policy issues. Methodologically, this study shows the benefits of having several data sources (namely, survey, media, and social media data) in measuring the effects of well-established political concepts. Our study confirms the value of social media for modeling prominent concepts used in traditional surveys, such as issue ownership and trespassing. However, social media research itself benefits from the integration of survey measures and of media trends to improve our interpretation of interactions on social media.

Practically, this study contributes to the highlighting of what could be best communication practices for political actors, as it shows which tweeting strategies and communications styles are more likely to generate other users’ engagement and media attention. Results show that the success of the chosen strategies and styles strongly depends on the Twitter audiences. For instance, while issue trespassing was successful in triggering online attention (other users’ reactions and media followership), it did not translate into increased online media coverage. A similar finding applies to tweets containing mobilization features. From a public opinion perspective, this study also contributes to enhancing our knowledge of how the dissemination of politicians’ messages exposes other users to political issues, and how it exposes non-users to political issues through the traditional media. In addition to how it relates to particular tweeting strategies and communications styles. It, thereby, reflects on previous studies that have highlighted the impact of politicians’ (and parties’) successful communication strategies on social media (i.e., Casero-Ripollés, Feenstra, and Tormey Citation2016), notably by demonstrating that mere exposure to politicians’ tweets can generate more positive attitudes toward political actors (Lee and Shin Citation2014). Therefore, while political success has mainly been conceived of in terms of triggered reactions (Keller and Kleinen-von Königslöw Citation2018b) and offline vote shares (Bright et al. 2019), this study argues that (online and offline) media attention is an additional component of political success. It therefore contributes to the discussion about media interconnection. Indeed, results suggest that candidates who benefit from a higher proportion of media followers and from increased social media attention tend to benefit from more traditional media coverage as well.

This study entails several limitations. First, to answer our research interests, we relied on the social media accounts of political candidates from major parties who possessed Twitter accounts during the 2019 Swiss federal election campaign. However, it can be expected that the politicians who are using Twitter possess distinct characteristics than candidates who are only passively tweeting or candidates who are not at all on Twitter. Second, we linked social media data to news media data to assess politicians’ media coverage. However, other media types could have been included such as TV and radio, which also contribute to the formation of public opinion. Third, the operationalization of responsiveness could have been more nuanced by distinguishing the audiences to which replies were addressed (i.e., other users, political actors with the same or another political affiliation, media accounts, etc). A more fine-grained coding of responsiveness could better distinguish between the concept of political responsiveness (usually directed to citizens) and other forms of interactivity. This could be done via manual annotation of the user profiles or by training a model that could classify different user categories.

Future studies should endorse a more cross-national perspective to uncover cultural differences. For instance, direct democracy votes, which enable frequent political discussions between politicians and the public, make Switzerland an interesting case study for assessing the interactivity patterns of candidates on social media. However, future studies could benefit from a comparison between several political systems (i.e., proportional, majoritarian, etc.) and media landscapes (i.e., centralized, fragmentized, etc.) to assess the generalizability of the obtained findings. Future studies could also include other social media platforms. For instance, Kalsnes, Larsson, and Enli (Citation2017) found that Facebook allows for more connections between citizens and politicians without news media as mediators. Indeed, Facebook enables “ordinary” people to engage in political interaction with politicians and to receive replies from politicians, whereas Twitter is mostly used by a small group of the population for this political exchange. However, Twitter tends to be the preferred channel for politicians to have a dialogue with citizens (Enli and Skogerbø Citation2013). Future studies could also think about including additional explanatory factors of successful online and offline attention. We can think about including an indication of whether candidates were involved in political scandals. This might be particularly interesting given the diffusion potential of social media (virality). However, this might also suggest the need for a bigger sample of politicians than the one used for this study. Finally, future studies could also include non-textual data in the analyses. Indeed, an effective communication strategy also encompasses the use of multimedia content (such as images or videos). Considering non-textual content is especially important with the spread of social media, as it can serve personalization purposes for political communication (Farkas and Bene Citation2021) and positively predict users’ engagement with social media messages in the case of election campaigns (Kite et al. Citation2016; Lam, Cheung, and Lo Citation2021).

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Maud Reveilhac

Dr. Maud Reveilhac has a background in political science, social psychology, and survey research. The integration and complementarity of various data sources for the study of public opinion, as well as the transferability and adaptability of computational (social) research methods, are at the center of her research. She is currently Post-doc at the Department of Communication and Media Research at Zurich University. She is also involved in research to enhance the reproducibility and replicability of research methods and processes..

Notes

1 For more information see the Selects panel survey (waves 1–3) 2019 dataset distributed by FORS: https://doi.org/10.23662/FORS-DS-1184-1

2 The survey data are available here: https://doi.org/10.48573/f2dg-9v33

3 The survey data are available here: https://doi.org/10.23662/FORS-DS-1186-2

4 Another possible operationalization follows the approach by Rauh, Bes, and Schoonvelde (Citation2020). However, given the shortness of tweets, we proffered to avoid a method that relies on text windows.

5 Since 1977, surveys have been conducted on behalf of the Federal Council after each federal popular vote to understand the reasons for a yes or no response by voters. Until June 2016, these post-vote surveys were known as VOX. In 2016, the mandate took place under the name of VOTO, under a new responsibility that lasted until September 2020. For more information see: https://www.voto.swiss

6 Often tweets consist of short messages that cannot be coded even through manual coding. Therefore, non-codings generally include non-substantial documents. This constitutes a possible advantage compared to machine learning methods which would have classified the tweets nevertheless.

References

- Aldrich, J. H., and J. D. Griffin. 2003. “The Presidency and the Campaign: Creating Voter Priorities in the 2000 Election.” In The Presidency and the Political System, edited by Michael Nelson, 7th ed. Washington, DC: Congressional Quarterly.

- Baik, Jason M., Thet H. Nyein, and Sepideh Modrek. 2022. “Social Media Activism and Convergence in Tweet Topics after the Initial #MeToo Movement for Two Distinct Groups of Twitter Users.” Journal of Interpersonal Violence 37 (15–16): NP13603–NP13622.https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605211001481

- Bene, M. 2023. “Who Reaps the Benefits? A Crosscountry Investigation of the Absolute and Relative Normalization and Equalization Theses in the 2019 European Parliament Elections.” New Media & Society 25 (7): 1708–1727. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211019688

- Bernhard, L. 2020. “The 2019 Swiss Federal Elections: The Rise of the Green Tide.” West European Politics 43 (6): 1339–1349. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2019.1710687

- Bode, L., and K. E. Dalrymple. 2016. “Politics in 140 Characters or Less: Campaign Communication, Network Interaction, and Political Participation on Twitter.” Journal of Political Marketing 15 (4): 311–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377857.2014.959686

- Bräuninger, T., M. Brunner, and T. Däubler. 2012. “Personal Voteseeking in Flexible List Systems: how Electoral Incentives Shape Belgian MPs’ Bill Initiation Behaviour.” European Journal of Political Research 51 (5): 607–645. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2011.02047.x

- Bright, J., S. Hale, B. Ganesh, A. Bulovsky, H. Margetts, and P. Howard. 2020. “Does Campaigning on Social Media Make a Difference? Evidence from Candidate Use of Twitter during the 2015 and 2017 U.K. Elections.” Communication Research 47 (7): 988–1009. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650219872394

- Carey, J. M. 2009. Legislative Voting and Accountability. New York: Cambridge University Press

- Casero-Ripollés, A., R. A. Feenstra, and S. Tormey. 2016. “Old and New Media Logics in an Electoral Campaign: The Case of Podemos and the Two-Way Street Mediatization of Politics.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 21 (3): 378–397. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161216645340

- Castanho Silva, B., and S. Proksch. 2022. “Politicians Unleashed? Political Communication on Twitter and in Parliament in Western Europe.” Political Science Research and Methods 10 (4): 776–792. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2021.36

- Ceron, A. 2017. “Intra-Party Politics in 140 Characters.” Party Politics 23 (1): 7–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068816654325

- Cha, M., H. Haddadi, F. Benevenuto, and K. P. Gummad. 2010. “Measuring User Influence on Twitter: The Million Follower Fallacy.” Proceedings of the 4th International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media. Washington, DC, 23–26. http://www.icwsm.org/2010/papers.shtml. https://doi.org/10.1609/icwsm.v4i1.14033

- Chadwick, A. 2013. The Hybrid Media System. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Damore, D. F. 2004. “The Dynamics of Issue Ownership in Presidential Campaigns.” Political Research Quarterly 57 (3): 391–397. https://doi.org/10.1177/106591290405700304

- Diez-Gracia, A., P. Sánchez-García, and J. Martín-Román. 2023. Polarisation and emotional discourse in the political agenda on Twitter: disintermediation and engagement in electoral campaigns. Icono 14 21 (1). https://doi.org/10.7195/ri14.v21i1.1922

- Downs, A. 1957. An Economic Theory of Democracy. New York: Harper.

- Eberl, J.-M., P. Tolochko, P. Jost, T. Heidenreich, and H. G. Boomgaarden. 2020. “What’s in a Post? How Sentiment and Issue Salience Affect Users’ Emotional Reactions on Facebook.” Journal of Information Technology & Politics 17 (1): 48–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2019.1710318

- Enli, G. S., and E. Skogerbø. 2013. “Personalized Campaigns in Party-Centred Politics: Twitter and Facebook as Arenas for Political Communication.” Information, Communication & Society 16 (5): 757–774. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2013.782330

- Ennser-Jedenastik, L., C. Gahn, A. Bodlos, and M. Haselmayer. 2022. “Does Social Media Enhance Party Responsiveness? How User Engagement Shapes Parties’ Issue Attention on Facebook.” Party Politics 28 (3): 468–481. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068820985334

- Ernst, N., F. Esser, S. Blassnig, and S. Engesser. 2019. “Favorable Opportunity Structures for Populist Communication: Comparing Different Types of Politicians and Issues in Social Media, Television and the Press.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 24 (2): 165–188. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161218819430

- Farkas, X., and M. Bene. 2021. “Images, Politicians, and Social Media: Patterns and Effects of Politicians’ Image-Based Political Communication Strategies on Social Media.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 26 (1): 119–142. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161220959553

- Fischer, M., and F. Gilardi. 2023. Level playing field or politics as usual? Equalization–normalization in directdemocratic online campaigns. Media and Communication 11 (1): 43–55. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v11i1.6004

- Fletcher, R., and R. K. Nielsen. 2018. “Are People Incidentally Exposed to News on Social Media? A Comparative Analysis.” New Media & Society 20 (7): 2450–2468. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817724170

- Giger, N., S. Bailer, A. Sutter, and T. Turner-Zwinkels. 2021. “Policy or Person? What Voters Want from Their Representatives on Twitter.” Electoral Studies 74:102401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2021.102401

- Gilardi, F., T. Gessler, M. Kubli, and S. Müller. 2021. Issue ownership and agenda setting in the 2019 Swiss national elections. Swiss Political Science Review 28 (2): 190–208. https://doi.org/10.1111/spsr.12496

- Graham, T., M. Broersma, K. Hazelhoff, and G. Van‘t Haar. 2013. “Between Broadcasting Political Messages and Interacting with Voters.” Information, Communication & Society 16 (5): 692–716. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2013.785581

- Graham, T., D. Jackson, and M. Broersma. 2017. “Exposing Themselves? The Personalization of Tweeting Behavior during the 2012 Dutch General Election Campaign.” 67th Annual Conference of the International Communication Association, 25–29 May 2017, San Diego, CA, USA.

- Harder, R., J. Sevenans, and A. P. Van. 2017. “Intermedia Agenda Setting in the Social Media Age: How Traditional Players Dominate the News Agenda in Election Times.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 22 (3): 275–293. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161217704969

- Heiss, R., D. Schmuck, and J. Matthes. 2019. “What Drives Interaction in Political Actors’ Facebook Posts? Profile and Content Predictors of User Engagement and Political Actors’ Reactions.” Information, Communication & Society 22 (10): 1497–1513. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2018.1445273

- Hoffmann, C. P., and A. Suphan. 2017. “Stuck with ‘Electronic Brochures’? How Boundary Management Strategies Shape Politicians’ Social Media Use.” Information, Communication & Society 20 (4): 551–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2016.1200646

- Holtz‐Bacha, C. 2014. “Political Advertising in International Comparison.” In The Handbook of International Advertising Research, edited by H. Cheng, 554–574. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Howard, P. N. 2006. New Media Campaigns and the Managed Citizen. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Jacobs, K., and N. Spierings. 2019. “A Populist Paradise? Examining Populists’ Twitter Adoption and Use.” Information, Communication & Society 22 (12): 1681–1696. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2018.1449883

- Jensen, M. J. 2017. “Social Media and Political Campaigning: Changing Terms of Engagement?” The International Journal of Press/Politics 22 (1): 23–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161216673196

- Jungherr, A. 2016. “Twitter Use in Election Campaigns: A Systematic Literature Review.” Journal of Information Technology & Politics 13 (1): 72–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2015.1132401

- Kalsnes, B. 2016. “The Social Media Paradox Explained: Comparing Political Parties Facebook Strategy versus Practice.” Social Media + Society 2 (2): 205630511664461. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305116644616

- Karlsen, R. 2013. “Obama’s Online Success and European Party Organizations: Adoption and Adaptation of US Online Practices in the Norwegian Labor Party.” Journal of Information Technology & Politics 10 (2): 158–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2012.749822

- Karlsen, R., and B. Enjolras. 2016. “Styles of Social Media Campaigning and Influence in a Hybrid Political Communication System: Linking Candidate Survey Data with Twitter Data.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 21 (3): 338–357. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161216645335

- Keller, T. R. 2020. “To Whom Do Politicians Talk and Listen? Mapping Swiss Politicians’ Public Sphere on Twitter.” Computational Communication Research 2 (2): 175–202. https://computationalcommunication.org/ccr/article/view/38. https://doi.org/10.5117/CCR2020.2.003.KELL

- Keller, T. R., and K. Kleinen-von Königslöw. 2018a. “Followers, Spread the Message! Predicting the Success of Swiss Politicians on Facebook and Twitter.” Social Media + Society 4 (1): 205630511876573. https://doi.org/10.1177/205630511876573

- Keller, T. R., and K. Kleinen-von Königslöw. 2018b. “Pseudo-Discursive, Mobilizing, Emotional, and Entertaining: identifying Four Successful Communication Styles of Political Actors on Social Media during the 2015 Swiss National Elections.” Journal of Information Technology & Politics 15 (4): 358–377. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2018.1510355

- Kite, J., B. C. Foley, A. C. Grunseit, and B. Freeman. 2016. “Please like Me: Facebook and Public Health Communication.” PloS One 11 (9): e0162765.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0162765

- Kalsnes, B., A. O. Larsson, and G. Enli. 2017. “The Social Media Logic of Political Interaction: Exploring Citizens’ and Politicians’ Relationship on Facebook and Twitter.” First Monday 22 (2): 6348. https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v22i2.6348

- Klinger, U., and J. Svensson. 2015. “The Emergence of Network Media Logic in Political Communication: A Theoretical Approach.” New Media & Society 17 (8): 1241–1257. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814522952

- Kligler-Vilenchik, N., and I. Literat. 2018. “Distributed Creativity as Political Expression: Youth Responses to the 2016 US Presidential Election in Online Affinity Networks.” Journal of Communication 68 (1): 75–97. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqx005

- Klinger, U., and U. Russmann. 2017. “Beer is More Efficient than Social Media”—Political Parties and Strategic Communication in Austrian and Swiss National Elections.” Journal of Information Technology & Politics 14 (4): 299–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2017.1369919

- Koc-Michalska, K., D. Lilleker, A. Smith, and D. Weissmann. 2016. “The Normalization of Online Campaigning in the Web 2.0 Era.” European Journal of Communication 31 (3): 331–350. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323116647236

- Kovic, M., A. Rauchfleisch, J. Metag, C. Caspar, and J. Szenogrady. 2017. “Brute Force Effects of Mass Media Presence and Social Media Activity on Electoral Outcome.” Journal of Information Technology & Politics 14 (4): 348–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2017.1374228

- Kriesi, H. 2005. Direct-Democratic Choice. The Swiss Experience. Lanham, MD: Lexington.

- Kruikemeier, S., K. Gattermann, and R. Vliegenthart. 2018. “Understanding the Dynamics of Politicians’ Visibility in Traditional and Social Media.” The Information Society 34 (4): 215–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2018.1463334

- Lam, S. Y. B., M. F. M. Cheung, and W. H. Lo. 2021. “What Matters Most in the Responses to Political Campaign Posts on Social Media: The Candidate, Message Frame, or Message Format?” Computers in Human Behavior 121:106800. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106800

- Lee, E.-J., and S. Y. Shin. 2014. “When the Medium is the Message: How Transportability Moderates the Effects of Politicians’ Twitter Communication.” Communication Research 41 (8): 1088–1110. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650212466407

- Lilleker, D. G., J. Tenscher, and V. Štětka. 2015. “Towards Hypermedia Campaigning? Perceptions of New Media’s Importance for Campaigning by Party Strategists in Comparative Perspective.” Information, Communication & Society 18 (7): 747–765. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2014.993679

- McGregor, S. C. 2019. “Social Media as Public Opinion: How Journalists Use Social Media to Represent Public Opinion.” Journalism 20 (8): 1070–1086. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884919845458

- McGregor, S. C. 2020. “Taking the Temperature of the Room: How Political Campaigns Use Social Media to Understand and Represent Public Opinion.” Public Opinion Quarterly 84 (S1): 236–256. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfaa012

- Nielsen, R. K. 2012. Ground Wars: Personalized Communication in Political Campaigns. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Peeters, J., P. Van Aelst, and S. Praet. 2021. “Party Ownership or Individual Specialization? A Comparison of Politicians’ Individual Issue Attention across Three Different Agendas.” Party Politics 27 (4): 692–703. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068819881639

- Petrocik, J. R. 1996. “Issue Ownership in Presidential Elections, with a 1980 Case Study.” American Journal of Political Science 40 (3): 825–850. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111797

- Praet, S., P. Van Aelst, W. Daelemans, S. Walgrave, T. Kreutz, J. Peeters, and D. Martens. 2021. “Comparing Automated Content Analysis Methods to Distinguish Issue Communication by Political Parties on Twitter.” Computational Communication Research 3 (2): 1–27. https://computationalcommunication.org/ccr/article/view/45. https://doi.org/10.5117/CCR2021.2.004.PRAE

- Rahat, G., and T. Sheafer. 2007. “The Personalization(s) of Politics: Israel, 1949-2003.” Political Communication 24 (1): 65–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584600601128739

- Rauh, C., B. J. Bes, and M. Schoonvelde. 2020. “Undermining, Defusing or Defending European Integration? Assessing Public Communication of European Executives in Times of eu Politicisation.” European Journal of Political Research 59 (2): 397–423. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12350

- Reveilhac, M., and L. Eisner. 2022. “Political Polarisation on Gender Equality: The Case of the Swiss Women’s Strike on Twitter.” Statistics, Politics and Policy 13 (3): 255–278. https://doi.org/10.1515/spp-2022-0003

- Reveilhac, M., and D. Morselli. 2023. “The Impact of Social Media Use for Elected Parliamentarians: Evidence from Politicians’ Use of Twitter during the Last Two Swiss Legislatures.” Swiss Political Science Review 29 (1): 96–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/spsr.12543

- Sandberg, L. 2022. “Socially Mediated Issue Ownership.” Communications 47 (2): 241–261. https://doi.org/10.1515/commun-2020-0020

- Schröder, Valentin, and Christian Stecker. 2018. “The Temporal Dimension of Issue Competition.” Party Politics 24 (6): 708–718. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068817693474

- Selb, P., and G. Lutz. 2015. “Lone Fighters: Intraparty Competition, Interparty Competition, and Candidates’ Vote Seeking Efforts in Open-Ballot PR Elections.” Electoral Studies 39:329–337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2014.04.009

- Sevenans, J., Q. Albaugh, and T. Shahaf. 2014. “The Automated Coding of Policy Agendas: A Dictionary Based Approach (v. 2.0.).” CAP Conference 2014, Konstanz, 12–14.

- Sides, J. 2006. “The Origins of Campaign Agendas.” British Journal of Political Science 36 (3): 407–436. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123406000226

- Spierings, N., and K. Jacobs. 2014. “Getting Personal? The Impact of Social Media on Preferential Voting.” Political Behavior 36 (1): 215–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-013-9228-2

- Spierings, N., and K. Jacobs. 2019. “Political Parties and Social Media Campaigning: A Qualitative Comparative Analysis of Parties’ Professional Facebook and Twitter Use in the 2010 and 2012 Dutch Elections.” Acta Politica 54 (1): 145–173. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-018-0079-z

- Stieglitz, S., and L. Dang-Xuan. 2013. Emotions and information diffusion in social media—sentiment of microblogs and sharing behavior. Journal of management information systems 29 (4): 217–248. https://doi.org/10.2753/MIS0742-1222290408

- Stier, S., A. Bleier, H. Lietz, and M. Strohmaier. 2018. “Election Campaigning on Social Media: Politicians, Audiences, and the Mediation of Political Communication on Facebook and Twitter.” Political Communication 35 (1): 50–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2017.1334728

- Teresi, H., and M. R. Michelson. 2015. “Wired to Mobilize: The Effect of Social Networking Messages on Voter Turnout.” The Social Science Journal 52 (2): 195–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soscij.2014.09.004

- Thesen, G., C. Green-Pedersen, and P. B. Mortensen. 2017. “Priming, Issue Ownership, and Party Support: The Electoral Gains of an Issue-Friendly Media Agenda.” Political Communication 34 (2): 282–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2016.1233920

- Tresch, A., and A. Feddersen. 2019. “The (In)Stability of Voters’ Perceptions of Competence and Associative Issue Ownership: The Role of Media Campaign Coverage.” Political Communication 36 (3): 394–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2018.1542416

- Tresch, A. 2009. Politicians in the media: Determinants of legislators’ presence and prominence in Swiss newspapers. International Journal of Press/Politics 14 (1): 67–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/194016120832326

- Tromble, R. 2018. “Thanks for (Actually) Responding! How Citizen Demand Shapes Politicians’ Interactive Practices on Twitter.” New Media & Society 20 (2): 676–697. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816669158

- Van Aelst, P., T. Sheafer, and J. Stanyer. 2012. “The Personalization of Mediated Political Communication: A Review of Concepts, Operationalizations and Key Findings.” Journalism 13 (2): 203–220. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884911427802

- Van Camp, K. 2017. “The Influence of Issue Ownership Perceptions on Behavior of Journalists.” PhD thesis, University of Antwerp.

- Van Dalen, A., Z. Fazekas, R. Klemmensen, and K. M. Hansen. 2015. “Policy Considerations on Facebook: Agendas, Coherence, and Communication Patterns in the 2011 Danish Parliamentary Elections.” Journal of Information Technology & Politics 12 (3): 303–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2015.1061398

- van der Loo, M., J. van der Laan, R. C. Team, N. Logan, and C. Muir. 2021. Package ‘stringdist’. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/stringdist/stringdist.pdf

- Vatter, A. 2016. Switzerland on the Road from a Consociational to a Centrifugal Democracy?. Swiss Political Science Review 22 (1): 59–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/spsr.12203

- Vissers, S., and D. Stolle. 2014. “Spill-over Effects between Facebook and on/Offline Political Participation? Evidence from a Two-Wave Panel Study.” Journal of Information Technology & Politics 11 (3): 259–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2014.888383

- Vos, D. 2016. “How Ordinary MPs Can Make It into the News: A Factorial Survey Experiment with Political Journalists to Explain the Newsworthiness of MPs.” Mass Communication and Society 19 (6): 738–757. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2016.1185128

- Walgrave, S., J. Lefevere, and A. Tresch. 2012. “The Associative Dimension of Issue Ownership.” Public Opinion Quarterly 76 (4): 771–782. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfs023

- Wijffels, J., M. Straka, and J. Straková. 2019. Package ‘udpipe’. R package. https://cran.microsoft.com/snapshot/2019-10-09/web/packages/udpipe/udpipe.pdf

- Yu, C., D. B. Margolin, J. R. Fownes, D. L. Eiseman, A. M. Chatrchyan, and S. B. Allred. 2021. “Tweeting about Climate: Which Politicians Speak up and What Do They Speak up about?” Social Media + Society 7 (3): 205630512110338. https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051211033815

Appendix A:

Distribution of the perceived most competent party to solve the main policy issues of the 2019 Swiss election campaign

Appendix B:

Distribution of political candidates’ perceptions about the most important problems of the 2019 Swiss election campaign

Appendix C:

Coding scheme for issue ownership and trespassing at the tweet level

Appendix D:

List of keywords to identify mobilization related tweets

Appendix E:

Accuracy of the custom policy issue dictionary

To construct our custom policy issue dictionary, we identified the keywords mentioned in the open-ended responses. Then, we complemented this initial list with other key terms referring to the direct open-ended responses stating pros and cons of the arguments related to each of the objects submitted to direct democracy votes in Switzerland during the same year. These open-ended answers are available in the VOTO studies conducted after each direct democracy vote in SwitzerlandFootnote5. The terms were manually translated into German and French. Sevenans, Albaugh, and Shahaf (Citation2014) showed that dictionaries can produce reliable, valid, and comparable measures of policy and media agendas.

To label each text with an issue topic, the number of words from the dictionary was counted in each text. A text was labeled with the issue for which it had the highest count of words. This method is like what coders do to manually classify each open-ended response into defined policy issue categories. It is important to note that a given tweet may refer to several policy issues. When this happens, we attribute the topic that was most salient in the tweet by counting the number of words referencing each topic. If we obtained an equal number of words for each topic, we randomly choose between the topics of the tweet. We did not include all the survey policy categories decided by the survey team as some contained very few instances (i.e., national cohesion) and others were not specific enough to indicate policy issues (i.e., “law and order”, and “political system”) to be included. This left us with 13 policy issue categories.

Sometimes, there was no issue present (i.e., a tweet about a personal topic or a tweet referring to a campaign activity) or the issue was not clear because there was not enough text or none of the words in the dictionary appeared in the text. This processing of the data resulted in 80% of the tweets being marked as explicitly referring to the 13 policy issue categoriesFootnote6. The excluded tweets were on average less retweeted than the labeled tweets, but the difference is not statistically significant (the t-test shows a p-value > 0.05). However, the excluded tweets were on average significantly more liked than the labeled tweets (the t-test shows a p-value < 0.05).

The accuracy of the custom policy issue dictionary was evaluated on the tweets emitted by the major Swiss parties during the 2019 election period. Each tweet was manually labeled for each policy issue it mentions. For instance, if a tweet mentioned environmental and gender equality concerns, it was labeled as “1” for each category (namely, “Environment and energy” and “Gender issues and discrimination”) and “0” for the remaining categories. Then, the dictionary was applied and the scores for sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy were calculated. The results are displayed in the following table:

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of the variables.

Table 2. Regression models for the dependent variables with independent variables scaled between 0 and 1.

Table 3. Summary of the research hypotheses and results.