ABSTRACT

In this qualitative case study, positioning itself within the social constructionist approach, we aimed to investigate and interpret identity narration and organizational identity in strategic external and internal communication at the health technology startup company Naava Group Oy. By analyzing three different datasets (Twitter, blog posts, and interviews), we examined how organizational identity was emerged and which way it was strategic in storytelling and narratives. The results indicate that the startup's strategic social media identity storytelling seemed strategically crafted, as various voices were detected to narrate the same stories that repeated the same narrative content. The study also interestingly reveals that the four identities emerging from narrative storytelling were interpermeable and strongly connected to the narratives’ content. The social media narratives and identities varied slightly during the 8-year period that the datasets, in total, covered. However, the identities communicated on social media were more coherent than the internal identities expressed by employees. The findings suggest that, in strong startup identity creation, the cohesiveness of the identity storytelling, the voices that narrate the identity construction, and the content and temporal dimensions of the narrated stories are strategic key factors.

The strategicness of an organization's communication is defined by its relation to the organization's strategy (Juholin & Rydenfelt, Citation2020). This makes a startup company an intriguing yet challenging environment for strategic communication: when startups are defined particularly with their innovativeness and growth (e.g., Kollmann et al., Citation2016), organizations are characterized by a constant change and their desirable organizational structure is, primarily, flexible. Moreover, communication is hardly ever a prioritized function when establishing a company. Hence, it is unsurprising that startups have challenges, even in the basic orientation of strategic communication (Wiesenberg et al., Citation2020). Based on their literature review and explorative interviews of communication consults, Wiesenberg et al. (Citation2020) showed that branding, external image, stakeholder relations, allocation of financial resources, owner centricity, human resources, and internal communication also face or produce difficulties. The need for startups’ strategic communication research is obvious.

Zerfass et al. (Citation2018) suggested that to be considered strategic, communication must be significant for an organization's development, growth, identity, or survival and include purposeful engagement in conversations that are strategically significant for the company's goals. In startups, all these focuses are important and, moreover, development and growth are core dimensions of creating a startup company and its identity. To survive, startups need clear, distinctive identities that allow them to express their core business, values, and market positioning (Rode & Vallaster, Citation2005) and informs strategic decision-making processes (Evans, Citation2015). Moreover, organizational identity is needed for personnel to identify with. Yet, the strategic nature of identity construction is understudied. Therefore, this study aims to provide knowledge regarding startup companies’ strategic use of identity construction, which is enacted through identity-related narratives. That is, strategic communication forms the framework within which we interpretatively examine the construction of a startup's identity. Our focus is on external image building in social media and internal identity construction in personnel's identity narration, which are in a recurrent interplay (Smith, Citation2013). This study seeks to engage with the debate on dynamic organizational identity construction as multi-sited strategic communication.

Theoretical framework

Organizational identity and strategy

When human actions are examined, the concept of identity is inherent, yet problematic (Albert et al., Citation2000) and it is understood and defined in numerous contradictory ways. However, they all share an understanding of the self-referential meanings: it refers to an endeavor to define oneself or themselves (Corley & Gioia, Citation2004, p. 87). Accordingly, identity is a construction that attempts to answer the questions “who am I?” in organizations “who are we?” and “who do we want to become?” (He & Brown, Citation2013, p. 6). Diverse ontological and epistemological assumptions explain how the meanings derived from the answers to these questions become comprehensible and tangible. The present study is grounded on the social constructionist approach, which sees organizational identity as socially constructed and composed of meanings referring to the organization (He & Brown, Citation2013). Accordingly, in the current study, we define organizational identity as a construction that pursues to crystallize “who we are and what we are going to be” but is yet dynamic. Moreover, we see this construct as created, manifested, and negotiated through narratives in internal and external arenas (Langley et al., Citation2020). Hence, identity is not something an organization has, but something that is collaboratively and dynamically constructed (Brown, Citation2006; T. S. Johansen, Citation2014).

In the existing literature, the branch of research on the relationship between organizational identity and strategic communication is surprisingly thin. The review of previous studies has shown that strategic communication is described as a tool for creating identity (e.g., Collins, Citation2012), and research has often anchored on the social identity theory and cognitive categorizations (Broch et al., Citation2018). However, organizational identities are multiple, fluid, and dynamic as Huang-Horowitz and Evans (Citation2017) showed in their study on small firms. They examined how companies used their identity as a component of strategic communication with stakeholders when legitimizing the company and in their study, ended up using a term of complex dynamic organizational identity, which comprises multiple dimensions. They suggest that active building of a complex dynamic identity can be used to improve both external and internal strategic communication. In the current study, we analyze identity construction as external and internal storytelling.

Narratives and organizational identity construction

Winkler and Etter (Citation2018) argued that strategic processes emerge from communication and narratives. Thus, organizational narratives are inherent in organizational identity construction and strategy building (Vaara et al., Citation2016). Strategy focuses the narrative lens on the future by telling stories about the times to come, while identity is anchored in the stories that emerged from the past and are reaching for the future (He & Brown, Citation2013; Sillince & Simpson, Citation2010). Organizational narratives and identities are always told in historical, social, and cultural contexts (De Fina, Citation2021; T. S. Johansen, Citation2014). Furthermore, organizational identity can be constructed by relevant coexisting narratives; through multiple stories and storytellers, an organization can have a developing and changing identity (Brown, Citation2006). This identity can include various dimensions and be articulated within an organization or publicly. In this study, organizational identity is approached as storytelling between organizational insiders and outsiders (see Coupland & Brown, Citation2004).

The narrative approach is very prominent for startup research because narratives play a key role in organizational reality, especially in stability and change (Vaara et al., Citation2016). In this study, narratives are seen as potentially incomplete and fragmented storytelling (Boje, Citation2001) and tied to their contexts (T. Johansen, Citation2012). Narrated identities are seen as complex and partial stories constantly in progress and, therefore, evolving over time and embedded in contextual practices (Brown, Citation2006).

In strategic use, the narratives participate in defining, demonstrating, implementing, and reevaluating the company's strategy in public and internal arenas. This ongoing strategic communication invites stakeholders to participate in this strategy-related process while affecting them and their perceptions of the company (Zerfass & Sherzada, Citation2015). In this identity interaction process, employees are considered important internal stakeholders (Smith, Citation2013), and therefore, communication not only between leaders and external stakeholders but also leaders and employees inform identity construction and image making (e.g., Gioia et al., Citation2013; Huang-Horowitz & Evans, Citation2017). Then, a dynamic organizational identity that emphasizes different company characteristics can become strong enough to answer a strategic challenge to differentiate the company from other startups and for this dynamic identity to function as the basis for sustainable success. When this is done in various arenas, the company's strategic communication engages in conversations that explicitly indicate and shape the company's identity.

The identity narration and storytelling that create, manifest, and negotiate meanings regarding the company in public arenas can be resource, competition, environment, risk, innovation, engagement, or operationally driven (Zerfass et al., Citation2018). These drivers, or goals motivating strategic choices, also affect the company's strategic decisions regarding the organizational identity they express on social media through narratives, or the identities assigned to them by other social media users. These decisions may become visible, for instance, in the way the company uses reciprocal communication on various platforms with established reach and followership, and social capital (such as trust and reputation) in the company's strategic communication (Zerfass et al., Citation2018).

On social media, companies engage in various discourses in online public communication spheres. In these interactions, various voices participate in constructing meanings that shape social and cultural realities, including companies’ identities. This combination of self-generated and other user-generated narratives is key for understanding the importance of strategic narrative identity construction because the social interactions developed around such content significantly affect how stakeholders see the company (Cooke & Buckley, Citation2008). This is particularly important for startup companies that are creating the foundation for their scaleup phase. Although startup companies tend to use social media actively (Almotairy et al., Citation2000), network oriented social media platforms are important for identity construction of entrepreneurs’ individual and their organization's identity (Horst et al., Citation2020), and they have become widely followed on social media platforms, research focusing on startups’ strategic online narratives is scarce (Wiesenberg et al., Citation2020). These narratives become articulated in social interactions, texts, and other media.

The aim of the study

The aim of this study was to understand the strategic use of narratives in identity construction on digital platforms and in internal communication. This aim is achieved via four empirically oriented research questions. RQ1 and RQ2 were formed on the premise that organizational narratives are crucial in an organization's identity construction and strategy building (e.g., Vaara et al., Citation2016): (RQ1) What kinds of narratives construct a startup's organizational identity? (RQ2) What kind of organizational identity emerges from the narratives? Furthermore, we see identity as a construction negotiated through an organization's internal and external practices (Langley et al., Citation2020); thus, we are also interested in the employee's viewpoints: (RQ3) What kind of organizational identity is constructed through employees’ narratives? Because identity is always in flux and evolving in time (Brown, Citation2006), we explore the dimensions of identity through strategic narratives reaching backward and onward in every now when each narrative is told from a temporal viewpoint: (RQ4) How does the startup's narrated organizational identity change over time?

Methods

Case

In this study, the startup company whose strategic communication is under scrutiny is the Naava Group Oy (later Naava, formerly known as NaturVention). The research was conducted in agreement with Naava, and no anonymity regarding the company was assumed or required. Naava is a health technology company founded in 2012. Its award-winning products comprise smart, living green walls. These design interior walls use technology that multiplies plants’ ability to clean air. Most of Naava's clients are commercial clients, but their products are also available for private clients. The company is innovative, uses capital from various sources for development, and has demonstrated significant scalable growth rates in turnover and workforce (Kollmann et al., Citation2016). To examine the strategic use of identity construction, this study focuses on narratives in Naava's Twitter communication and blog posts that discuss these themes and allow identity creation as well as on organizational narratives that are manifested in interviews with company personnel.

Data collection

The study data comprised two manually gathered datasets (1,765 tweets and 140 blog posts) and a set of semi-structured interviews (11).

Tweets

The tweet data were gathered on Twitter (http://twitter.com/Naava) from March 2016 to March 2020. Although Naava's Twitter account was created in 2013, no tweets earlier than March 22, 2016 could be accessed. Roughly 50% of the tweets in the dataset were original tweets, and the rest were retweets. About 20% of the tweets were in Finnish and the rest in English. Many of the retweets had links to Naava's blog posts or international news about Naava.

Blog posts

The blog data comprised posts on Naava's website (https://www.naava.io/fi/editorial, https://www.naava.io/science, and https://www.naava.io/news) from 2013 to 2020. Most of these blog posts were published in Finnish and in English, 27 only in Finnish and 13 only in English. Most of the blog posts were published in 2016 and 2017, for a total of 104 posts. Style wise, these blog posts were not just traditional blog posts; they also included press release-style news, copied news, and other kinds of texts about Naava from other websites, such as the Finnish Broadcasting Company Yle. Comments were not enabled on these blog posts.

The tweets and blog posts included various links to websites, images, and videos. All these dimensions affect storytelling and meaning-making with audiences (De Fina, Citation2021). However, it is beyond this study's scope to analyze all the links and other visual elements of these data. Thus, the focus of this study is on the text level. For example, links to other websites were analyzed as the text part of a tweet or a blog.

Interviews

Eleven semi-structured interviews were conducted in Finland in spring 2018, soon after the rapid expansion phase of the company had started. At the time, within less than five years, the number of personnel had more than tripled to approximately 40 employees. New offices were opened in Finland, Sweden, and the United States. Some interviewees had worked at Naava almost from the beginning; some were recent hires. Participation was voluntary; the interviewees gave their written consent, and the principles of ethical conduct were thoroughly followed. Since no data regarding special categories were not collected in the study, approval from the universities’ ethical councils was not asked, although, the research involved human subjects. In the interviews, questions related to work, internal communication, organizational commitment, and the internationalization of the company were asked. The duration of the interviews varied from 37 minutes to 1 hour 12 minutes; the entire interview data totaled 9 hours 20 minutes. Before the analysis, the recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim.

Analysis

Analysis of tweets and blog posts

This research drew from the understanding that companies tell stories to help organize and make sense of their existence, and their story accounts are functional and purposeful (Figgou & Pavlopoulos, Citation2015). Hence, the analysis was driven by the aim of identifying narrated identities, defined as complex and partial stories constantly in progress and, therefore, evolving over time and embedded in contextual practices (Brown, Citation2006). Thus, identities are constructed of narratives that is storytelling about a company's past and future. This storytelling is potentially incomplete and fragmented (Boje, Citation2001) and tied to context (T. Johansen, Citation2012). Each blog post and each tweet were treated as a narrative, a part or a turn in a larger storytelling that are “contributions to the narrative process through which identity emerges” (T. Johansen, Citation2012, p. 238). Although the tweets lacked a story-like structure, we treated them as micronarratives that contributed to Naava's overarching identity storytelling through several narratives.

The unit of analysis in the Twitter data was one tweet and in the blog data one blog post. To answer RQ1, tweets were analyzed as micronarratives and blog posts as stories and to answer RQ2 they were analyzed as a part of Naava's broader identity narrative. Since we did not focus on the plot structure, in the analysis we concentrated on the content of the stories in each tweet and blog post. We approached these contents inductively. Following Riessman (Citation2008) we focused on “[t]hematic analyses of the substance of narratives – ” (p. 1069), in other words, the content themes of narratives. This kind of analysis focuses more on what types of stories are told and what topics emerge from stories than viewing the data as one narrative where the characters, plot, and other narrative elements are analyzed. Thus, the goal of this analysis was to make substantial and meaningful interpretations and conclusions regarding the company's construction and maintenance of its strategic identity through the various kinds of narratives interpreted from the data.

The descriptive coding was done inductively by asking the data about what kind of company Naava is and what kind of company it wants to become. Utilizing the practical guidelines of reflexive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) the narratives (RQ1) and emerging identities (RQ2) were identified. Theme comparison was used in the temporal change examination to answer RQ4. During the first round of analysis, we examined each tweet and blog post, searching for recurring patterns and themes to form codes with broad scope, such as “narrative” and “activities”. The number of interpreted themes per blog post or tweet was not limited. We organized the codes into preliminary categories and subcodes, such as “technology,” “self-promotion,” and “nature”. In the next coding round, we reexamined the codes and categories and renamed, merged, and recategorized some until certain categories started to reemerge. The analysis resulted in four identity categories (one core identity and three supporting identities) and four main narrative categories (one main narrative and three supporting narratives comprising five narrative subcategories). These categories are presented in the results section.

Analysis of interview data

The interview data was approached as storytelling in the moment of a significant turn in the history of the company when expansive growth had recently begun. The analysis aimed to identify narratives that are presenting the company's past and the future expectations on which employees told through describing their work and employer. The analysis focused on the content of storytelling (Riessman, Citation2008), where employees made sense of their organization (Boje, Citation2001), identifying the actors helped to understand the possible strategic dimension of internal communication and identity construction. We read the data several times to obtain a holistic understanding of the data. Then the main storylines were identified, and the analysis continued by recognizing the significant actions and roles and twists in telling and the meanings that were given to them (see McAllum et al., Citation2019). We identified five narratives which we arranged at two identity categories, that is, two focuses of identification: the product and the company. The most apparent actors were “the founders” or “the CEO”, regarding interviewees’ own role, a narrative of personal development was identified. In the next section, the results are presented according to the research questions.

Results

Narratives in tweets and blog posts

The first research question sought to answer what kinds of narratives construct a startup's organizational identity. The company blog and Twitter account were the digital arenas on which Naava and other narrators constructed, revised, and reconstructed the company's narrated identity. The interpretative analysis of the data indicated that the narrative that dominated storytelling was the solution provider narrative. It was constantly repeated in tweets and blog posts. This narrative draws from Naava's main product and the clean air it produces: “Outdoor air is thick in Seoul. Luckily, Koreans can now breathe a little easier indoors, with Naava. #Seoul #SouthKorea #breathenaava #freshair #airquality #qualityair” (Naava @breathenaava, February 28, 2019).

Many external, yet coherent, voices participated in constructing the dominant organizational narrative. The interactive nature of Twitter emphasized the multimodality of storytelling, which was strategically collaborative, joint, emergent, and dynamic. In the blog posts, customer stories represented the multi-voiced dimension of storytelling. Of course, Naava controlled these storytellers by deciding which tweet to retweet. There were no negotiations of several different voices, it was Naava holding all the strings and directing the other voices to tell what the company wanted, creating an illusion of various narrators.

Three other narratives were also found in the analysis: clean indoor air, well-being, and intelligence and work efficiency. These narratives, also drawing from the functions of Naava's main product, supported and contributed to the solution provider narrative. They were cohesive and intertwined in multiple levels as several narrators participated in the storytelling: “Excited to announce our partnership with @teknion in North America! Soon even more office workers in the US and Canada can enjoy forest-grade air and nature next to their desks. #NeoCon2019” (Naava @breathenaava, June 11, 2019).

These informative and awareness-increasing narratives reasoned why the company was necessary, legitimized its products’ demand and supply, and allowed Naava to present itself to new customers and employees. The clean indoor air narrative proudly stated that “clean Finnish air” could now be breathed globally. The clean indoor air narrative was combined with the other two supporting narratives in a chain of reasoning: When Naava green walls produce clean indoor air in an office, workers are healthier, they can make more intelligent decisions, and their work efficiency is much higher than it would be without clean indoor air. Examples from blog post titles highlight the efficiency and how different narratives overlap in the blog posts: “Naava Office Improves Wellbeing and Productivity,” “Bad Indoor Air Makes You Dumber – A Finnish Company Fights the Problem with Plants,” and “Harvard University Study Confirms the Connection Between Indoor Air Quality and Decision Making.”

These supporting narratives that contributed to the solution provider narrative were strategically selected by the startup: for instance, stories were told by customers, representatives of other technology companies, international collaborators, printed media, and digital news. These supporting narratives facilitated sense-making of the direction in which Naava was heading: a company that could solve indoor air quality challenges on a global scale. When told by customers and collaborators, these narratives also contributed to the organizational reputation.

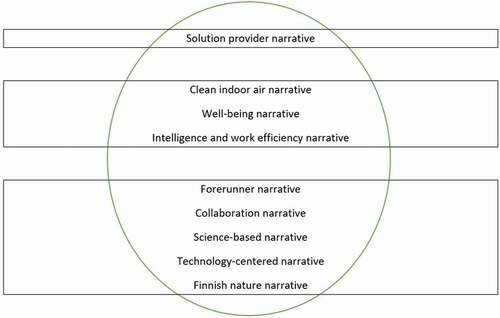

Based on the results, there were five subnarratives which, in turn, contributed to the supporting narratives. These subnarratives were the forerunner, collaboration, science-based, technology-centered, and Finnish nature narratives. These narratives were intertwined, like those that supported the dominant narratives. shows the narratives.

The results indicate that Naava used the forerunner narrative to present the competitive edge of Naava's innovative product and the company. The green walls are now a more mature product, tested and validated in practice. Yet their development is an ongoing process that Naava reported being committed to in their forerunner narrative. This narrative was quite extensive. Naava's smart green walls also made their collaborators forerunners:

Tallink Silja is one of the largest passenger and cargo shipping companies operating in the Baltic Sea. It is a natural partner for NaturVention, as both companies’ focus is to offer innovative premium class services to their customers. Marika Nöjd, Tallink Silja's Communications Director, states “It's great to be the world's first shipping company, which has active green walls in use. By utilizing Naava fresh walls, we can provide a best-air environment to enhance the experience of all our customers” (Blog post, “NaturVention Received a Growth Funding of Value 1,5 Million Euros and Begins to Export Best Indoor Air to Stockholm,” November 30, 2015).

The collaborator narrative was particularly present in the blog posts because customer stories were the most often used blog genre. The other two genres are information and news. This narrative was also visible in Naava's retweets, as they repeated stories in which their customers told how beneficial or even life-changing the Naava smart green wall had been. In the blog posts, the collaborator narrative emphasized the continuity of the collaboration with Naava after the product (the green wall) has been purchased. Therefore, this narrative was also tied to the company, not just to the product: “Additionally, Naava's regular maintenance service is incredibly appreciated at ÅWL. With Naava Service, the people at ÅWL get to enjoy its benefits without having to worry about taking care of the smart green wall themselves” (Blog post, “Why Naava? ÅWL Arkitekter Uncovers the Benefits,” January 19, 2018).

The forerunner subnarrative was closely tied to science-based and technology-centered subnarratives, as they were used to explain the latest health technology that Naava green walls use. In the science-based narrative, the use of innovative knowledge from the most recent scientific discoveries was explained, and in the technology-centered narrative, science-based knowledge was combined with the newest technological solutions, such as the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in the green walls. This combination was then included in stories that Naava and outsiders told about the company and its pioneering position in health technology. The Finnish nature subnarrative permeated all other narratives and was linked to the main solution provider narrative that drew from Finnish nature and its clean air when solving indoor air issues: “As a nod to #StPatricksDay, here's something #green from #Finland. Besides the forest covering 75% of the country, they're bringing greenery and fresh air indoors with healthy @breathenaava walls. We visit a few places to see what that's about: http://ow.ly/T3DU30o2MUx #evergreen” (Naava retweeted @thisisFINLAND, March 17, 2019).

After the analysis of the narratives was conducted, the results were compared with the two narratives told on the company website. The first one, the “Our Story” section of their website, revolved around clean (indoor) air. Following how the company was described in the story, it can be interpreted that Naava wanted to tell stories about an innovative, nature-, future-, and technology-oriented company that promotes positive change, commits to health promotion, supports sustainable development, dares to dream big, and trusts in its potential. The company sought legitimacy for its vision and mission by citing or referring to global organizations, often seen as authorities, such as the World Health Organization (WHO). It seems that the company's “Our Story” narrative was coordinated with the narratives Naava told on social media: Naava wanted to provide solutions to problems that affect air quality.

The second comparative narrative presented on Naava's website was the story of one of the founders, Aki Soudunsaari. This story was clearly significant to Naava, as it was told on the company website and repeatedly in blog posts and referred to in tweets. When the story was also used as comparison material for the analysis results, the solution provider narrative started to seem to be even more strategically used. In this story, Naava's narrative began with the subjective experiences of Soudunsaari, who grew up in a small town in Northern Finland, known for its beautiful and clean nature. He worked as a physical education and health science teacher and started suffering from dry and sore eyes, loss of voice, and cognitive problems, such as tiredness and short-term memory loss when teaching. In the outside air, none of these symptoms surfaced. Soudunsaari learned that his symptoms were caused by chemical hypersensitivity due to exposure to many different chemicals during his life. He produced the idea of bringing fresh outdoor air inside. Soudunsaari met another founder, Niko Järvinen, who was studying biology and information technology and had experience in cleaning industrial waste from water with microbes. Together, they created Naava, a smart green wall that purifies air using living plants combined with innovative technologies. Their vision evolved from solving Aki's problem (not being able to work indoors) to enabling fresh air solutions for people worldwide by connecting humanity with nature (Naava, Citation2020).

Identities constructed in tweets and blog posts

The second research question examined what kind of organizational identity Naava's strategic narratives conveyed on Twitter and in their blog posts. The results indicate that, in the narratives, the organizational identity was socially constructed. The dimensions of it were built on the foundation created by Naava's main product, green walls, and despite the many voices telling these stories, the narratives talked about the same dimensions of the startup's organizational identity.

As the dominant narrative results already suggested, Naava's organizational identity revolved primarily around the identity dimension of a solution provider. This identity was strikingly coherent, particularly on Twitter. Stories contributing to this identity were told by Naava but also, for instance, by Finnish and international experts in various fields, customers, collaboration partners, climate change activists, investors, Naava employers, and organizations that promote Finland and Finnish design. In the blog posts, customers especially shared their experiences widely and frequently.

The solution provider identity was constructed with implicit and explicit expressions of challenges that needed to be conquered. A typical way to present the solution provider's identity was to first build an argument that demonstrated a problem and then provide the solution via Naava's main product:

Combining aero- and hydroponics we achieve 100 times more efficient air cleaning compared to normal house plants. Impure indoor air is sucked through the plants root system where all the chemicals are broken down by the microbes living in the roots (Blog post, “Who Wants to Breathe in Xylene, Toluene or Ammonia?” November 22, 2013).

However, as this example indicates, the solution provider's identity was usually intertwined with another identity dimension. In total, three other substantial identity dimensions were discovered in the organizational identity: (re)connector with nature, promoter of well-being and health, and innovative interior designer. The supporting contributing identity dimensions were slightly more fragmented than the solution provider identity dimension. The fragmentation was discovered, for instance, in the lack of clarity regarding the assumed audiences of the strategic communication because some of the tweets and blog posts were highly informative, yet the information was not connected to the company or its product. presents the four identity dimensions.

The first of the identity dimensions that the solution provider dimension penetrated was the (re)connector with nature. The results showed that the incidence of this dimension was stronger in blog posts than in tweets, in which it was expressed as often as other identities. In the blog posts, the (re)connector with nature dimension was stated frequently and overtly. In both datasets, this organizational identity dimension was constructed through storytelling that relied on a psychological and long-term orientation toward nature. The broader inclusion of nature that Naava as the (re)connector with nature promised with its green walls was often linked to invoking a sense of belonging to or being part of nature in the company's tweets. This was driven from various perspectives:

We heard offices in Sweden were running out of fresh #air, so, we imported some from Finland. The brand new #Naava breathing room opened yesterday in the center of Stockholm. Feel free to stop by to experience #nature in the middle of the city! (Naava @breathenaava, April 20, 2018).

In this example, the connection is approached from an experiential perspective. The nature-related experiences were told in the stories contributing to the organizational identity in tweets and blog posts, mostly referring to internal connections to nature, such as emotions or worldviews. Therefore, these stories often operated on the individual-experience level, yet occasionally also referred to society-level experiences. Moreover, in the blog posts, this identity dimension was backed up by research:

A vast amount of scientific literature has shown that nature has a fundamental positive influence on our minds and bodies, and scientists from different fields have taken the task to figure out the mechanisms behind these phenomena (Blog post, “Biophilia – The Love of Life and All Living Systems,” September 11, 2017).

In this case, the effect of nature is based on the appearance of a green wall, bringing plants into inside environments. The role of nature was also emphasized in the blog posts and tweets, with explanations that the basic air purification mechanism Naava relies on is natural, or as they often verbalized it, “millions of years of nature's development”:

Biofiltration is a pollution control technique where a bioreactor containing living material is used to capture and biologically degrade pollutants, commonly used in processing wastewater or factories’ air purification.

During biofiltration, the polluted matter (dirty water, or in Naava's case, poor indoor air) is filtered through organic materials and microorganisms. The good microbes living in plants’ roots break the pollutants down into nutrients for the plants.

In Naava's biofiltration system, the air circulates through the plants, plants’ roots, and our growth medium, forming a natural air purification process (Blog post, “Naava and Biofiltration – Natural Indoor Air for Everyone,” February 27, 2018).

In Naava's organizational identity, (re)connection with nature was also approached from the perspectives of cognitive connection (knowledge and attitudes) and emotional attachment or affective responses. These perspectives were told in persuasive stories that reminded stakeholders of their ancient connectedness to nature in the framework of the most innovative, science-based, smart technology: “We're in an exciting research project with Finnish universities and companies! In the future, especially in urbanized areas, we may get our daily nature exposure from the air and consumer products – to prevent allergies and other immune-mediated diseases!” (Naava @breathenaava, December 20, 2018).

Sometimes, the (re)connector with the nature identity dimension seemed to rely on fostering environmental knowledge or on feelings of attachment to nature. Despite the stories’ emphasis that created the framework for this dimension, (re)connection with nature was usually tied closely to the solution provider dimension: (Re)connection was framed as a solution to a problem caused by urbanization. This type of storytelling contributing to the identity mix often included proven health benefits connected to the “dose of nature” that a person needs before the benefits can be reaped.

The second identity dimension penetrated by the solution provider dimension was the promoter of well-being and health. In the blog posts, this dimension was grounded in science and customer stories, and it often overlapped with the (re)connector with the nature identity dimension. In the tweets, this promoter of well-being and health dimension was seen most often in Naava's retweets: A customer originally tweeted about their indoor problem and how Naava's smart green walls fixed the issue. In the process, the health and well-being of the customer's employees and even clients had improved tremendously. In Naava's tweets, this connection was not as explicit

The #OpenOffice #trend has breaded a new need for sharing spaces among different work practices. At @EsriFinland, lush Naavas divide the space for different functions and uplift the spirits near the working desks. Which kind of space makes you accomplish the most? #office (Naava @breathenaava, March 7, 2018).

In the data analysis, the emphasis on outsider-generated content was stronger in the stories that contributed to the promoter of well-being and health identity dimension than in stories that contributed to Naava's organizational identity. In the blog posts, customer experiences with Naava green walls were told at the individual and community levels: the individual-level focus was on how Naava had solved a health issue, and the community-level focus was on how Naava had improved the overall well-being of a work community. Furthermore, the green walls were described as promoting the well-being of Naava's customers:

In addition to traditional services, the pharmacy offers its customers a range of other health care supporting services. A wellbeing corner is one of them. There the customers can explore health and wellbeing literature and enjoy a refreshing smoothie surrounded by the fresh and natural air that Naava provides (Blog post, “Naava as a Part of a Wellbeing Concept,” May 18, 2016).

The stories related to the health promoter identity dimension showed customer empowerment, as with the help of Naava green walls, and customers actively expressed control over decisions regarding their health and well-being. Naava's green walls were attached to office and workplace environments alongside gyms and other recreational surroundings. Naava seemed to care about their stakeholders’ overall well-being. In the blog posts, the promoter of well-being and health identity always surfaced when the story of founding the company was repeated. In these cases, this identity was highlighted through the subjective experiences of one of the founders. The strategies for promoting this identity dimension varied and were often complex and interrelated: Naava appealed to individual behavior and beliefs, work culture, practices and policies, and even broader socioeconomic factors, such as culture and media.

The third identity dimension penetrated by the solution provider identity was the innovative interior designer identity dimension. The company described their green walls as smart, beautiful design furniture that significantly affects the atmosphere everywhere, as people enjoy themselves more when fresh and clean air is provided. In many blog posts, Naava's customers described how their own customers enjoyed the visuals of the green walls. Naava regularly identified with more established office furniture manufacturers: “Naava's North America partnership with one of the world's largest furniture manufacturers @teknion has been noted by @tekniikkatalous” (Naava @breathenaava, June 17, 2019).

Naava also actively tweeted and retweeted that their green wall interior design solutions were available at various fairs and exhibitions worldwide. Naava told their own stories in their tweets and blog posts, and retweeted stories told by others about how Naava partnered actively with different office furniture manufacturers. However, in the blog posts, these partnerships were not emphasized at all: Blog posts told stories of satisfied customers who enjoyed the fresh and calming looks of Naava's green walls. This ongoing identity storytelling included organizational insider and outsider narrators, and the identity dimensions narrated by outsiders supported the organization's self-understanding: “You can now find Naava products from @Archello, the platform to discover #architecture and #design products” (Naava @breathenaava, October 29, 2018).

Overall, despite the multi-voiced nature of Naava's identity storytelling, outsiders’ tweets added little to the identity negotiation. The interior designer's identity dimension was also combined with other identity dimensions and sewed together with business values. For instance, in the blog post “How Can Space Increase Profit? Evidence-Based Design Supports Wellbeing and Productivity,” Naava summed up how design could also affect well-being and profits. The innovativeness as a part of this identity was found when Naava told in the blog posts how the company's green walls are more than just ordinary house plants or green walls. Naava emphasized the technological part of their product: “That's why plants are a universal, year-round solution for bringing natural air indoors. The natural air purification efficiency of plants can be enhanced, as we have done with our Naava smart green walls” (Blog post, Biophilic Design Enhances Wellbeing,” November 17, 2017).

Employees’ narratives and identities

The third research question focused on the organizational identity constructed and confirmed through employees’ narratives. Two identities were identified: “naava” the product, or “Naava” the company. Naava as a company was comprised the expansion narrative and the vigilance narrative. The expansion narrative appeared in the stories about the company's drive and growth goals, its speed and international dimension. It provided a story through which employees made sense of the growth and identified themselves with the growing organization, thereby strengthened the organizational identity. In this narrative the role of the CEO was central, even though many interviewees described the expansion as a shared strive. The role of the team was of vital importance in the vigilance narrative, through which the employees made sense of the growth. They illustrated a picture of flexible, agile personnel that is eager to work for the success of the company. The vigilant narrative comprised commitment-inducing stories about low hierarchical structure, the freedom of doing, and a very casual and relaxed communication culture alongside a value of “everyone does everything.”

“Perhaps I see it [being a Navaen] as engaging to and understanding this company. And that even though it is growing, it is still a very start-up. [- -] Although people find their way here from different branches, they come however from the same kind of categories. And it is that, then they have a willingness to help, and you will rip the time to help the other or do something that does not belong to your own duties.” (I3)

The vigilance narrative emphasized the startup nature of Naava identity when the expansion narrative simultaneously carried the meanings of a growing scaled-up company. Concurrently appearing these narratives challenged but also completed each other: the expansion was done perhaps at the cost of vigilance, but the vigilance enabled the company's expansion.

When aligned with Naava identity, the personal growth narrative illustrated the role of an employee, who is getting and taking responsibility. The dynamic Naava enables learning in a challenging interdisciplinary work environment that requires many kinds of competences.

“I feel that I am developing all the time. I get more charges, I learn. Few days are similar. I have varied tasks that I like, and I feel that I can influence my tasks, this role. Naava is a quite small company, so you can participate in many events.” (I7)

The naava product identity comprised the challenging product and the magnificent product narratives. The challenging product narrative draw a story of many challenges which were caused by a “slow product” that “are difficult workmates,” since it is hard to forecast plants growth. The newness of this kind of product, which is also a very uncommon startup product, explained employees’ willingness to engage with the product's development. Winning the challenges is something that was done together, it provided an important role for everyone. The other narrative of the naava identity was the magnificent product narrative. It told a story of future well-being, focusing on nature orientation and green values. The founders had an important position as generators, but employees had their role in an important task of building the future through a product that even “changes the world.”

“It is the product you want to sell, a product that should be in every place. I believe in our mission. I am the kind of person who does not want to sell any shit. [- -] It is [the product] a little bit different, some are very excited about it, it is, when you say to a 50-year-old engineer then they are like “aha, what is this … ”. It is about believing in this. A little bit more special. That creates a sense of community too. (I5)

The magnificent product narrative created a strong anchor for organizational identification grounded on the remarkable naava product. The personal development narrative completed the story by providing a thread of personal growth through persistent problem solving, when combined with the naava identity.

In the interviews two-faceted organizational identity was constructed. When naava identity aligned with the beginning and the history and more universal values the company contributes, Naava aligned with company's future and business values. The naava symbolizes a creative product, when Naava means creativity of actions.

Temporal change in organizational identity

The last research question investigated the startup's narrated organizational identity change over time. The analysis of the data indicated that there were no major changes in the emerging organizational identity throughout the time that the datasets covered, although it is possible that the internal expansion narrative emerged over time. Naava consistently used certain narratives to make sense of who they are as a growth company and combined the narrative of one of their founders with the explicit solution provider narrative. The same story was used throughout the data. Two other small stories were used from the beginning: The first claimed that we breathe more than 15 kg of air every day, out of which 14 kg are indoor air, and the second stated that, although we can choose not to drink dirty water or eat spoiled food, we cannot choose not to breathe the air that surrounds us. Throughout the study period, the data consistently presented the company as highly interactive and innovative while caring for sustainable development and customer well-being. Naava seemed to use its past as a means of moving forward, aligning future organizational identity with the socially conveyed organizational identity of the past.

The slight shift in the emphasis expressed in the long-term identity implies that Naava's organizational identity is adaptive yet cohesive. Although the company still promotes green values and ecological solutions, Naava currently emphasizes creating innovative, AI-related solutions. Furthermore, in more recent blog posts, Naava tended to be more sales-oriented. In the older blog posts, the company provided only some information, for instance, about microbes, and did not mention the company or its product at all. Despite this, throughout the data, the ongoing construction of the company's narrated organizational identity relied on stories about shared and mutually constructed experiences alongside situational challenges that have been overcome, often collaboratively with partners, using innovative technology. This intersubjective identity creation indicates that Naava has created a very stable startup ecosystem around itself, comprising Naava, other startups, established companies, alongside economic and innovation actors. They all seem to believe in Naava's intelligent green walls and reinforce the company's core identity as a solution provider.

Conclusions

The aim of this study was to understand the strategic use of narratives in startup identity creation. The results contribute to the knowledge on the relationship between organizational identity and strategic communication, and to the, so far scarce, research focusing on startups’ strategic online narratives.

The results of our study suggested that the strategic identity narration on Twitter and the blog posts expressed overt coherence of the external image. The storytelling strategy seemed to be to increase awareness about the company and its products, and the collaborative storytelling looks like a strategic choice, as collaboration with customers and offering them the best possible service is engrained in Naava's company values. As values can been seen as a constitutive of an organizational identity (Huang-Horowitz & Evans, Citation2017), the organizational self-storying with multiple voices is strategically rationalized, it is cohesive and forms the framework within which the need for the product, naava, was reasoned. Thus, in external digital storytelling, Naava has a business idea and a product that the company passionately believes in. This results in a unisonous identity.

Mai and Schoeller (Citation2009) have suggested that informative narratives which synergize informational and emotional contents, increase an organization's memorability, thus, according to them emotionality is a strategic storytelling choice. In Naava's external communication, the content of storytelling was informative, but for instance, narratives of solution provider, well-being, and forerunner did have a strong emotional aspect. This may be a conscious solution but may also emerge from the eagerness to promote the company values. It would be interesting to study, how this resonates to other startups: as they are early in the process of getting a foothold on their target market, rememberable organizational identity can be seen as the key to understanding the concepts and values that the company wants to promote with its products and services.

In internal storytelling two parallel identities were constructed: The product-based identity naava was composed of heroic stories of winning the challenges, which seems to manifest a cultural discourse of persistent and hard-working actors. The company-based identity Naava emphasized the business stories of the talented and flexible strategics, aligning more closely with the current picture of vigilant startup companies. These internal narratives did overlap with external image building especially through the well-being and tied-to-nature narratives concerning the product. Furthermore, the external narrative of forerunner overlapped with the internal narratives of expansion and vigilance. However, even though in internal conversation the concurrently appearing division of company and product identities was discovered in the employees’ narratives, external identity storytelling was highly cohesive. The core organizational identity was wrapped around the product so seamlessly that it was challenging to separate the product identity from the company identity.

The difference between internal and external communication becomes understandable, as the external communication aims to sell, whereas the company forms an everyday working environment for employees. In the front of a vast expansion, internal storytelling reflected uncertainty in understanding what Naava as a company is or wants to be. This notion may reflect more general identity construction challenges of startup companies as inconsistencies in identity storytelling may be assumed to induce turbulence but also dynamic negotiations regarding organizational identity. Thus, a unanimous storytelling may be due to a strategy that resonates with the company's development from a product idea to an actual startup and seems to signify the strong belief and trust that the company still has, years after being founded, in their main product. These strategic choices can be seen to ensure the company's growth and development, and the discourses in which the narratives participate increase the validation of the interpreted identities. Furthermore, the product was occasionally put on a pedestal so much in the blogs and tweets that the line between the company and the product was indistinct.

Naava's external identity seems to be driven by competition, environment, innovation, and engagement, whereas the anchors of internal identification seem to be operationally and competition-driven (Zerfass et al., Citation2018). This fragmentation of the organizational identity may reflect the strategic self-storytelling choices that the company has made. The stories told to outsiders and insiders may differ, and Naava's example indicates that the themes of external narratives also tend to reflect to internal identities. However, Naava's internal identity narration could have benefit from a more refined management of the communication strategy. The narratives suggest that there is an attempt to create coherence, but as may be the case with many startup companies, if the more strategic narratives are the goal, they must be first recognized. This recognition offers an opportunity to select the narratives that the company wants to strengthen, even though the stakeholder adoption of them is not necessarily controllable by the company. To avoid internal confusion, it is a vital importance to explicitly make sense of the coexistence of different facets of identity.

Strategic stakeholder communication goals tend to reach beyond the informative stage, as Cornelissen (Citation2011) have stated. Our results imply that the strategic identity narration of a startup company creates involvement and commitment: narratives that were interpreted as commitment-inducing were found in Naava's internally told identity narratives, as the employees verbally expressed that they identified either with naava the product or Naava the company, or occasionally, with both. This suggests that when startups create a clear strategic plan regarding their external stakeholder communication and identity narration, they should not neglect the creation and implementation of a plan for their internal identity storytelling. As Cornelissen et al.’s (Citation2007) have notioned, setting clear goals for strategic internal and external identity narration can increase the commitment of all stakeholders because organizational identity penetrates all aspects of stakeholder relations. Ates et al. (Citation2018) state that when the cohesiveness of organizational identity storytelling is clearly explicated, it may become easier for employees to commit to the implementation of the vision of the organization, which has been noticed to be beneficial for growth.

Based on the temporal perspective, Naava's narrative actions seem to happen in an ongoing present (Bergson, Citation2007), but the storytelling draws from the experiences of one of its founders which took place before the company was founded. It is intriguing that the company's future is continually told from the past, even when the story is partially attached to new themes. Strategically, this reinterpretation process confirms identity and maintains cohesion between past, present, and future identities. Thus, even in quickly scaling up startups their identity can be simultaneously enduring and changing. Even when the organizational identity is in a constant state of becoming, some narratives can be long-lasting if they are systematically retold and constantly evaluated (Brown, Citation2006). According to Zerfass et al. (Citation2018), strategies often result in a pattern of tactical engagements. Thus, telling the story of one of the founders becomes the core of the product identity, which, in turn, with cohesive social media narration, also strategically becomes the core of the company identity.

Even though the company may benefit from the long-lasting narratives, the communication strategy of a dynamic company seems conservative, when the clear emphasis on future orientation leans heavily on the past. Huang-Horowitz and Evans (Citation2017) showed the contradictory nature in the identities of small companies in emerging fields: they can be adaptable yet focused and cutting edge yet traditional. Their suggestion of the complexity of organizational identity and its strategic narration supports our findings as it is possible that identity paradoxes are more common among startups than it might appear. However, using this strategy of drawing from the past requires high awareness, as the future organizational identity of a startup may be overwhelmed by the exceptional story of the past, even when the narratives talk about new growth targets and markets.

Although De Fina and Perrino (Citation2017) suggested that new digital contexts, in this case blog and Twitter, can induce new narrative genres, the present study highlights that using new platforms does not always result in a wider variety of genres that are used or mean more opportunities for interpretation. Naava's identity narration occurred on social media, but unlike T. Johansen's (Citation2012) finding, a cohesive external identity narration strategy seemed to narrow the stakeholders’ scope of interpretation regarding the narrated organizational identity. The unification of the external identity can, according to Schneider and Zerfass (Citation2018), be seen as a purposeful, strategic choice, as the social media coordinator moderates the multiple voices that tell the same stories. However, Schneider and Zerfass also stated that the main challenge for organizational communication is to integrate the plurality of voices into the perceptible values of communication and to align them with the organization's strategic goals. In the case of Naava, despite the possible strategic restrictions regarding which voices are allowed to participate in Naava's digital identity storytelling, the cohesion of the voices seems to make their identity creation strategy more believable. For startups, this kind of strategy can induce a situation that offers a competitive edge from the perspective of identity creation. There are several voices telling the startup's story, but they tell it in harmony, so it does not induce controversial, quarreling polyphony. Therefore, this cohesive identity-creation strategy can be called selective harmonic storytelling.

Despite findings that contribute to understanding startup identity construction through narratives, this study has several limitations. First, although Naava has had a Twitter account since 2013, tweets from before March 2016 were inaccessible. This may be related to the name change of the account from NatureVention to Naava. This lack of Twitter data meant that the examination of the temporal identity change relied heavily on Naava's blog posts. Second, most of the blog posts were published in 2016 and 2017. Third, the interview data covered approximately 25% of the personnel, and the interviews were conducted only at the Finnish locations. Interviews at international locations could have provided more variation in the narratives. However, the finding regarding twofold product–company identification was strongly narrated in the data and may be plausible from the viewpoint of startup ideology.

The findings of this study call for further research on the relationship between narrated identity, memories, and storytelling. Specifically, further exploration of identity construction that stems from employees’ shared narrative memory systems and addresses questions concerning identity issues across time and space is needed. It would also be interesting to conceptualize the strategic external and internal narration of identity in more detail with larger, multicompany data and to gain a more comprehensive understanding of its identity-related meaning-making processes.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have influenced the work reported in this paper.

References

- Albert, S., Ashforth, B., & Dutton, J. (2000). Introduction to a special topic forum. Organizational identity and identification: Charting new waters and building new bridges. Academy of Management Review, 25(1), 13–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2000.2791600

- Almotairy, B., Abdullah, M., & Abbasi, R. (2020). The impact of social media adoption on entrepreneurial ecosystems. In J. Tromp, L. Dac-Nhuong, & L. Van Chung (Eds.), Emerging extended reality technologies for Industry 4.0: Early experiences with conception, design, implementation, evaluation, and deployment (pp. 63–79). Scrivener.

- Ates, N., Tarakci, M., Porck, J., Van Knippenberg, D., & Groenen, P. (2018). The dark side of visionary leadership in strategy implementation: Strategic alignment, strategic consensus, and commitment. Journal of Management, 46(5), 637–665. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206318811567

- Bergson, H. (2007). The creative mind. Dover.

- Boje, D. M. (2001). Narrative methods for organizational and communication research. Sage.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Broch, C., Lurati, F., Zamparini, A., & Mariconda, S. (2018). The role of social capital for organizational identification: Implications for strategic communication. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 12(1), 46–66. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2017.1392310

- Brown, A. D. (2006). A narrative approach to collective identities. Journal of Management Studies, 43(4), 731–753. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2006.00609.x

- Collins, H. (2012). Organizational identity via recruitment and

- Collins, H. (2012). Organizational identity via recruitment and communication: Lessons from the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor project. Global Business and Organizational Excellence 31(5), 36–43. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/joe.21440

- Cooke, M., & Buckley, N. (2008). Web 2.0, social networks, and the future of market research. International Journal of Market Research, 50(2), 267–292. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/147078530805000208

- Corley, K., & Gioia, D. (2004). Identity ambiguity and change in the wake of a corporate spin-off. Administrative Science Quarterly, 49(2), 173–208. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/4131471

- Cornelissen, J. (2011). Corporate communication: A guide to theory and practice (3rd ed.). Sage.

- Cornelissen, J., Haslam, A., & Balmer, J. (2007). Social identity, organizational identity, and corporate identity: Towards an integrated understanding of processes, patternings and products. British Journal of Management, 18(s1), 1–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2007.00522.x

- Coupland, C., & Brown, A. (2004). Constructing organizational identities on the web: A case study of Royal Dutch/Shell. Journal of Management Studies, 41(8), 1325–1347. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2004.00477.x

- De Fina, A. (2021). Doing narrative analysis from a narratives-as-practices perspective. Narrative Inquiry, 31(1), 49–71. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1075/ni.20067.def

- De Fina, A., & Perrino, S. (2017). Storytelling in the digital age: New challenges. Narrative Inquiry, 27(2), 209–216. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1075/ni.27.2.01def

- Evans, S. (2015). Defining distinctiveness: The connections between organizational identity, competition, and strategy in public radio organizations. International Journal of Business Communication, 52(1), 42–67. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2329488414560280

- Figgou, L., & Pavlopoulos, V. (2015). Social psychology: Research methods. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 22, 544–552. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.24028-2

- Gioia, D. A., Patvardhan, S. D., Hamilton, A. L., & Corley, K. G. (2013). Organizational identity formation and change. Academy of Management Annals, 7(1), 123–192. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2013.762225

- He, H., & Brown, A. (2013). Organizational identity and organizational identification: A review of the literature and suggestions for future. Group and Organization Management, 38(1), 3–35. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601112473815

- Horst, S. O., Järventie-Thesleff, R., & Perez-Latrec, F. (2020). Entrepreneurial identity development through digital media. Journal of Media Business Studies, 17(2), 87–112. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/16522354.2019.1689767

- Huang-Horowitz, C. N., & Evans, S. K. (2017). Communicating organizational identity as part of the legitimation process: A case study of small firms in an emerging field. International Journal of Business Communication, 57(3), 327–351. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2329488417696726

- Johansen, T. (2012). The narrated organization: Implications of a narrative corporate identity vocabulary for strategic self-storying. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 6(3), 232–245. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2012.664222

- Johansen, T. S. (2014). Researching collective identity through stories and antestories. Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal, 9(4), 332–350. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/QROM-08-2012-1092

- Juholin, E., & Rydenfelt, H. (2020). Strateginen viestintä ja organisaation tavoitteet [Strategic communication and the goals of an organization]. Media Ja Viestintä, 43(1), 79–99. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.23983/mv.91081

- Kollmann, T., Stoeckmann, C., Hensellek, S., & Kensbock, J. (2016). European start-up monitor 2016. German Startups Association. https://europeanstartupmonitor.com/fileadmin/esm_2016/report/ESM_2016.pdf

- Langley, A., Ravasi, D., & Tripsas, M. (2020). Exploring the strategy-identity nexus. Strategic Organization, 18(1), 5–19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1476127019900022

- Mai, L.-W., & Schoeller, G. (2009). Emotions, attitudes, and memorability associated with TV commercials. Journal of Targeting, Measurement and Analysis for Marketing, 17(1), 55–63. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/jt.2009.1

- McAllum, K., Fox, S., Simpson, M., & Unson, C. (2019). A comparative tale of two methods: How thematic and narrative analyses author the data story differently. Communication Research and Practice, 5(4), 358–375. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/22041451.2019.1677068

- Naava. (2020). Naava website. https://www.naava.io/

- Riessman, C. (2008). Narrative methods for the human sciences. Sage.

- Rode, V., & Vallaster, C. (2005). Corporate branding for start-ups: The crucial role of entrepreneurs. Corporate Reputation Review, 8(2), 121–135. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.crr.1540244

- Schneider, L., & Zerfass, A. (2018). Polyphony in corporate and organizational communications: Exploring the roots and characteristics of a new paradigm. Communication Management Review, 3(2), 6–29. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.22522/cmr20180232

- Sillince, J. A. A., & Simpson, B. (2010). The strategy and identity relationship: Towards a processual understanding. In Joel A.C., B. and Lampel, J. (Eds.)The Globalization of Strategy Research (Advances in Strategic Management, Vol. 27), Emerald Group Publishing Limited, Bingley,pp. 111-143. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/S0742-3322(2010)0000027008.

- Smith, J. M. (2013). Philanthropic identity at work: Employer influences on the charitable giving attitudes and behaviors of employees. International Journal of Business Communication, 50(2), 128–151. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0021943612474989

- Vaara, E., Sonenshein, S., & Boje, D. (2016). Narratives as sources of stability and change in organizations: Approaches and directions for future research. The Academy of Management Annals, 10(1), 495–560. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2016.1120963

- Wiesenberg, M., Godulla, A., Tengler, K., Noelle, I.-M., Kloss, J., Klein, N., & Eeckhout, D. (2020). Key challenges in strategic start-up communication: A systematic literature review and an explorative study. Journal of Communication Management, 24(1), 49–64. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JCOM-10-2019-0129

- Winkler, P., & Etter, M. (2018). Strategic communication and emergence: A dual narrative framework. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 12(4), 382–398. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2018.1452241

- Zerfass, A., & Sherzada, M. (2015). Corporate communications from the CEO's perspective: How top executives conceptualize and value strategic communication. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 20(3), 291–309. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/CCIJ-04-2014-0020

- Zerfass, A., Vercic, D., Nothhaft, H., & Werder, K. P. (2018). Strategic communication: Defining the field and its contribution to research and practice. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 12(4), 487–505. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2018.1493485