ABSTRACT

Language technology tools provide a promising way to teach, share, retain, and curate under-resourced language learning materials in community. The inclusion of language teachers working with communities increases the potential for designed tools to be adopted by those groups. However, there is little research concerning the adaptation of tools designed with one community to other languages. To identify the implications for such scalability, we ran workshops with the ‘Record and Write’ tool, developed as a versatile format for collection, curation, and use of under-resourced language learning materials in community. The process enabled teachers of languages with varying availability of teaching materials to reflect on some of the embedded complexities of adapting the tool to their context. This paper critically reflects on the design process of the tool and design lessons learned relating to language governance, the reflection of culture in database tools, conversational learning support, and differentiated needs for grammatical accuracy and annotation. Methodologically, the paper proposes a reflexive lens on co-design in cross-cultural contexts, identifying some of the latent assumptions embedded in technologies that emerge when tools are transposed to different language and learning contexts.

1. Introduction

The learning of languages through computer-assisted language learning applications has seen widespread uptake (Chapelle Citation2001). Communities in the Global North (Escobar Citation2018) have ready access to an array of non-digital and, increasingly, digital language learning resources, drawing on a long history of linguistic analysis and pedagogical research of languages, such as English, Spanish and German. However, for learners of many other-than Global North languages, there are few or no dedicated learning resources (Angelo Citation2021; Genee and Junker Citation2018; Smith, Giacon, and McLean Citation2018). This is particularly true for many endangered languages, whose continued use and transmission rely on the knowledge of few speakers (Genee and Junker Citation2018; Meighan Citation2021; Smith, Giacon, and McLean Citation2018; Zaman and Falak Citation2018). In Australia, colonisation has had a devastating effect on many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander language communities (Bow Citation2020; Smith, Giacon, and McLean Citation2018) with only 12 of over 250 languages reported as widely spoken (Office for the Arts Citation2020); there remains insufficient appreciation by non-Indigenous people of the overwhelming consequences of this loss of language, knowledge and culture (Christie Citation2004; Granger Citation2016; Lee-Hammond and Jackson-Barrett Citation2019; Smith, Giacon, and McLean Citation2018).

Digital learning resources provide ways of capturing and delivering language content, however many of the technologies that are utilised contain inherent cultural biases and poor usability, unable to support grammatical structure and cultural authenticity, or are unsuitable for the infrastructures that the community can access (Galla Citation2016; Irani et al. Citation2010; Vaarzon-Morel, Barwick, and Green Citation2021). Designers need to find ways to co-design with communities without conforming systems to their (designers’) own cultural proclivities (Gulwanyang Citation2023a; Meighan Citation2021; Soro et al. Citation2016, Citation2017). Conforming ways of thinking is particularly problematic in database design. Language databases capture, structure, and store knowledge of languages, to then be able to be retrievable for later use (e.g. in mobile language learning applications, dictionaries, textbooks, etc.) If the database itself does not reflect the teachers’, and by extension the community’s, cultural needs and wants, they can perpetuate Global North conceptions and agendas (Christie Citation2004; Verran and Christie Citation2014).

Our conceptual framework emphasises the interconnectedness of tools, culture, and learning in language revitalisation efforts. We begin from the premise that documenting and teaching one’s own language, culture and innovations is a useful thing to do, as a formative step towards revitalisation (Verran and Christie Citation2007; Verran et al. Citation2007). There is potential for digital tools to support language communities in ways that the communities themselves direct (Escobar Citation2018; Gulwanyang Citation2023b).

Language database projects predominantly focus on archiving and documenting language data and access permission controls (Christen Citation2012; Christie Citation2004; Genee and Junker Citation2018; Pine and Turin Citation2017). This project focuses on the pedagogical functions of language databases including considerations around the user interface and the features and functionalities it provides to organise and annotate the language data in ways that are useful for users’ purposes, rather than archival functions. Our overarching aim is to understand the issues that are currently present in implementing a language database system that can be utilised by language teachers, and how insights from multiple language teacher partners can inform about best practices in developing technological systems that continue to support community led and owned language gathering and language delivery.

This paper presents a study in an overarching co-design process which involved three workshops to determine how a language web application developed within an endangered language community might be scaled to support teachers of other languages. The workshops involved teachers of Indigenous and non-Indigenous languages revealed inherent biases that accompany some of the formative design decisions that can have unintended impacts on vulnerable language groups. The process also uncovered assumptions regarding how languages are organised, and the flexibility that is needed in applications to ensure that communities can use, frame, and organise their language in a way that is reflective of their own culture. Our work includes the development of partnerships with teachers from four different language groups: Two endangered (Mangarrayi and Ktunaxa), one being revitalised (Gathang), and one Global North language (German).

The open questions that we investigate in this paper are:

RQ1:

How can designers sustainably co-design databases that represent language information in formats that can be appropriated by teachers and are representative of the language community and culture?

RQ2:

What lessons can be drawn for the design of language technologies from attempts to co-design with language teachers?

2. Background

In this paper, we present the second phase of a language learning database ‘Record and Write’. An overview of how the language learning tool was initially developed is outlined below (see ).

Figure 1. Overview of the co-design process. This paper focuses on the second phase: how databases can be appropriated by teachers.

2.1. ‘Record and Write’ tool development: phase 1

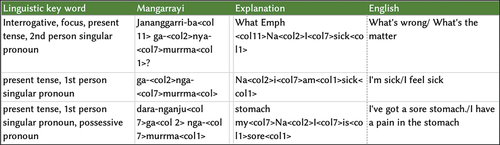

Warrma Mangarrayi ‘Listen to Mangarrayi’, is a language learning resource designed with the Jilkminggan community in the Northern Territory, university researchers and eLearn Australia, to support revitalisation of Mangarrayi, the traditional language of the community. Underlying Warrma Mangarrayi is a framework (database) developed in the course of earlier research with the Jilkminggan community (Richards et al. Citation2019) organising a bank of Mangarrayi phrases around topics, sub-topics and language functions (see , for initial design of the database using <col> to show grammatical detail). The approach is similar to a staged phrase-based approach previously used to support the revitalisation of Kaurna (an Indigenous language spoken by the Kaurna Meyunna people in South Australia (Sturt Citation2019)) in which learners are initially introduced to shorter, simpler expressions that are easier to pronounce and remember, moving gradually to more complex expressions (Amery Citation2001).

Figure 2. Image of the phase 1 database, prior to the development of the user interface ‘Record and Write’ web database tool (see ).

2.1.1. Improving the usability of the tool

Data entry for the Warrma Mangarrayi database was originally done by hand involving the written Mangarrayi phrase including marking up of individual suffixes to indicate grammatical function, word-for-word explanation, and English meaning (see ). Although the development process for Warrma Mangarrayi specifically targeted the Jilkminggan context, from the outset of the project it was hypothesised that other communities could use the underlying digital shell to develop a phrase-based learning resource for their own language. For communities to do this with greater independence, there needed to be a more user-friendly way of entering the data. Collaboration between researchers and developers in the team resulted in the development of a user interface (‘Record and Write’) to streamline the data input process. As part of the process, a series of design workshops were held with potential users across a range of Indigenous and non-Indigenous contexts to inform the design. Our paper presents and discusses the findings of this process (see Section 3.2 for aims).

3. Literature review

Although there have been well-resourced language databases developed, historically they have come under scrutiny for their lack of cultural situatedness (Christie Citation2004; Irani et al. Citation2010; Soro et al. Citation2015), lack of ownership by community and lack of recognition of the variable quality of digital infrastructure in some regions (Galla Citation2016; Simpson Citation2018). Decisions have primarily been made at either a government or platform level, raising questions regarding political agendas, data sovereignty and platform capitalism (Galla Citation2016; Simpson Citation2018). However, the inclusion of multiple perspectives in the development of language databases has proven problematic (or at least difficult), and researchers have looked for ways of addressing these issues to ensure communities ultimately have ownership and greater stewardship over their cultural assets. For this reason, a growing body of researchers have looked to co-design with Indigenous communities as a way of prioritising the needs and wants of the communities themselves before the implementation of technologies targeting their language and culture (Bird Citation2018; Harbord, Hung, and Falconer Citation2021; St John and Akama Citation2022; Tubby Citation2021). This review focuses on prior innovations in co-design methods and the lessons learnt in incorporating user viewpoints in the development of digitally assisted language learning technologies.

3.1. Co-designed methods and materials

Co-designing language databases with communities has been applied in several instances. One issue encountered is that members of design teams without a background in digital technology are not always aware of the possibilities and limitations of digital tools beyond everyday consumer applications such as Facebook or Twitter. This can lead to both power imbalances and unforeseen consequences and have ethical ramifications for decisions made (B. Matthews et al. Citation2023). To support the co-design process, researchers have employed a variety of methods to support communities in developing technologies for language learning, including repurposing non-digital materials and use of existing technologies.

3.1.1. Co-designing technical systems with situated non-digital materials

Non-digital materials have been used to gain insights into the needs and concerns of the community, as a means of counteracting perceived power imbalances related to differences in degrees of technical understanding among participants. Zaman and Falak (Citation2018) report on work done with a Penan community. Penan elders expressed concern over the younger generation not being engaged in learning Ooro, the sign language used by the community, as well as safeguarding the community’s autonomy to document and distribute their own material in a digital world (Escobar Citation2018). The generational divide between elders and younger learners is a common concern in communities that are witnessing the decline of language use (Christie Citation2004; Taylor et al. Citation2019). In the case of the Penan community, researchers worked with elders using forest walks and cards with common materials over periods of time, to understand the issues elders were trying to address in community. In using communication methods and materials the elders were familiar with, researchers gained a deeper understanding of the issues and supported the community to devise several solutions. Such critical work is time-, travel- and software development-intensive, a concern that has been raised by many researchers (Aluvilu et al. Citation2018; Simpson Citation2018; Smith, Giacon, and McLean Citation2018). While such approaches have had vital local impacts, there remains a need to find ways to design with communities that have the potential to scale to other language teaching and learning contexts.

3.1.2. Co-designing with existing technologies

The utilisation of existing technologies in co-design processes provides opportunities to engage communities in timely discussions regarding preservation, cross-generation engagement and educational implementation (Christie Citation2004). Researchers have broadly reported incorporating existing technologies in two ways: As free online tools that provide an economical solution for resource-limited communities, and as technological probesFootnote1 for investigating novel, possible solutions.

3.1.3. Free online tools

Researchers have considered the use of existing online tools to navigate increasing concern about the economic impact of government programmes to develop technologies for learning that were not always thoughtfully considered with respect to the local circumstances of endangered communities. Free-online tools provide technologies that are both familiar and easily adaptable to community needs, ensuring economic viability that requires little maintenance by community members. An example of the use of free online tools is the work conducted by a team of researchers with the Gamilaraay language centre. Smith et al. (Citation2018) discuss how using open-ended predeveloped tools such as PowToon, YouTube, Memrise, Facebook, and WordPress, can provide engaging content for learners and available, affordable means to support teachers with developing teaching materials. Despite the advantages discussed above, there are several caveats. One is that use of multimedia platforms can lead communities to feel they have a lack of ownership over materials. Communities have subsequently been encouraged to govern their ongoing presence on such platforms (Galla Citation2016; Smith, Giacon, and McLean Citation2018). Another concern raised is that existing online language learning platforms are not always culturally appropriate when adapted to a language, perpetuating an instructivist pedagogy (i.e. learner as the passive recipient), rather than a culturally situated constructivist pedagogy (learning in the environment) (Burston Citation2014; Smith, Giacon, and McLean Citation2018).

3.1.4. Technological probes

As discussed above, although free-online tools can be implemented as a timely and economical response, we have outlined several concerns, particularly with respect to the need for sustainable methods. For designers working with communities, using existing technologies as a way to understand socially bound problems (such as culturally situated language) is not usually considered best practice, as it directs participants thinking in pre-determined ways (Meighan Citation2021; Preece et al. Citation1994; Schuler and Namioka Citation1993; Soro et al. Citation2016). An alternative is to use existing technologies as a probe to start conversations and gather insights rather than as a direct response to a problem (W. W. Gaver et al. Citation2004; Iversen and Leong Citation2012; S. Matthews and Matthews Citation2021). Soro et al. (Citation2016), explore what it means to adapt technology from one culture as a probe for another culture, discussing how technology probes that are situated in communities can act as a mediator between researchers and participants to explore values and culture: land council members and rangers from Groote Eylandt approached researchers for help to develop an alternative method to engage the community in language and communication (see Soro et al. Citation2016, for further details of the Groote Eylandt context). The remote location of the community meant that any solution would need to be sustainable; therefore, the researchers engaged the community in co-designing workshops with ‘off the shelf’ technologies that could be locally situated and maintained. The workshops used a combination of technology and drawings and were developed as a way to understand the community’s requirements and values. The design process resulted in a digital noticeboard that has continued to be used and adapted by the community.

The three methods outlined above: non-digital situated materials, existing teaching technologies, and technology probes, provide us with examples of how to engage a broad range of users into a technology centred co-design process to ensure the balanced inclusion of multiple perspectives. In each of these cases, the methods and outcomes were situated in community. There is potential to adapt these methods to investigate the scalability of an existing database interface to other communities, prior to any potentially costly (culturally and economically) deployment to other communities, and consider what lessons can be drawn from that process.

In addition to learning from co-design methods that have been used successfully in community, it is equally important to understand how databases can pragmatically support the unique situatedness of communities’ on-the-ground needs.

3.2. Lessons from co-designing with communities

As the field has engaged with Indigenous communities, several lessons have been articulated to ensure that databases reflect not only a community’s needs and wants but the ‘ontic and epistemic’ (Verran and Christie Citation2014) uniqueness of their cultural knowledges (Verran and Christie Citation2014). This ensures non-community designers on co-design teams critically consider both their cultural (Escobar Citation2018; Galla Citation2016; Verran et al. Citation2007) and technocentric biases (Haraway Citation2016; Servaes and Hoyng Citation2017). Below we discuss three pertinent lessons derived from engaging with communities in the development of databases: develop ‘ontologically flat’ traditions (or systems); support shareable archives; build in levels of knowledge.

3.2.1. Ontological ‘flat’ structures

Verran and Christie (Citation2007) discuss how many database systems are designed to be representational of any one culture rather than meaningful to those who use them, leading them to remain unused and ill-defined. Different cultures have different social and political agendas that need to play out in the technologies they choose to use. Verran and Christie provide the example of Mängay Guyula, a Yolngu elder from Mirrngatja (NT Australia), whose use of technology reveals two modes of ‘standing in both worlds’ (Soro et al. Citation2017), firstly as a witness to his people and the land for future generations, and secondly to demonstrate his authority to outsiders. Mängay’s work with developing activities with technologies for his own purposes, inspired the TAMI project (Verran et al. Citation2007). The TAMI project was designed with Yolngu Aboriginal communities in Northern Australia. One of the most novel underpinnings of the TAMI project is that it successfully demonstrates an ‘ontologically flat’ technology system that allows for communities to ‘build up’ their own ways of representing and performing knowledge rather than being ‘pre-empted by Western assumptions’ (Verran et al. Citation2007, 133). An ‘ontological flat’ database is built to have no preconceived notions of hierarchy of information, rather it displays information such as video, audio, photos, and files in one window that allows the users to make, develop and present, their own metadata and knowledge systems. Although the TAMI project was not fully developed (Verran and Christie Citation2014), it provides an exemplar of the types of attributes designers should be considering when engaging with communities (Verran et al. Citation2007) in database design, such as: how can technology design enable communities to take control of their own knowledge production; what makes sense with respect to how to search for content; How can entered content be sorted into assemblages; and, what content can or should be viewed together for what purposes? These questions begin to explore what (else) databases could be in and for community.

3.2.2. Shareable archives

There are a small number of ‘ontologically flat’ databases that have been designed with a single Indigenous community and distributed to other Indigenous communities (Vaarzon-Morel, Barwick, and Green Citation2021). Communities have adopted databases for a variety of reasons, such as lack of support or facility to produce their own, or that language and culture is not being preserved through the younger generations (Christie Citation2004), or a fear that outsiders will hold their stories and language assets for political purposes (Verran and Christie Citation2014). One of the problematic aspects with communities co-opting databases, even ‘ontologically flat’ databases, is how communities deal with a lack of digital infrastructure (Wi-Fi or mobile). Database locations tend to exist on a primary site when access to knowledge is required in other parts of the community. For example, at ceremonies, or in particular seasons, communities have to find alternative ways of sharing and distributing knowledge (Vaarzon-Morel, Barwick, and Green Citation2021). As Vaarzon-Morel et al (Citation2021) discuss, this problem is compounded when culturally sensitive information ends up being stored on unprotected USB sticks. The USB stick has its advantages in that it ensures information is locatable with certain community members; however, there are serious risks of loss or theft. Database designers need better ways of considering how database knowledge might be used and shared on community governed shareable devices, that do not always require Wi-Fi or mobile connection.

3.2.3. Knowledge systems

Another aspect to communities co-opting archival database shells and protocols, is not only how information is shared (see above) but who can see what information when. In effective ‘Indigenous knowledge transmission’ (https://www.unesco.org/en/links/transmission Citation2018), it is important that it is situated and contextual, time, space, and place are carefully considered (Tubby Citation2021). Database designers have a responsibility to safeguard and preserve the forms of Indigenous knowledge production, through thoughtful consideration of how Indigenous groups weave knowledge together, based on their axiology, epistemology, and ontology (Martin and Mirraboopa Citation2003). This is particularly important given the often-intricate knowledge systems with contextualised restrictions on the sharing of knowledge. In the context of this current study, it is imperative to understand how knowledge systems are viewed within the community and implications for their use in teaching and learning, given there are a number of considerations when building language systems, such as organising large quantities of words and phrases, preserving and displaying the underlying syntax and morphology of words to convey meaning and pronunciation (Littell et al. Citation2018). In light of this, it is essential to consider how a ‘flat’ database that is initially designed for and with a particular language community might be scalable to other languages contexts and use cases.

In the following sections, we detail the steps undertaken in a study of the scalability of an input tool for an evolving open-ended community adaptable database system, discussing the lessons learnt from undergoing this process.

4. Research approach

This paper presents case studies from the second phase (i.e. the shell database ‘Record and Write’. See Section 2) of an ongoing project that explores educational technologies for the teaching of languages (see ). A ‘design-oriented research’ process was undertaken (Fallman Citation2003), conducting a series of workshops to ensure the inclusion of perspectives from educators working with limited resources. The initial tool was iteratively developed into an ‘ontologically flat’ and ‘open-ended’ database (i.e. no assigned language) with a user interface component. The existing interface was used as the stimulus to promote discussions in the workshops (see Section 4.5). Each iteration of the design process included a workshop (see Section 4.5), analysis of what was discussed in the workshop (see Section 4.6.1), research team discussion of findings, and finally a set of insights into tool design (see ).

Figure 3. Phase 2: process overview of the workshops for the user interface ‘Record and Write’ web database tool.

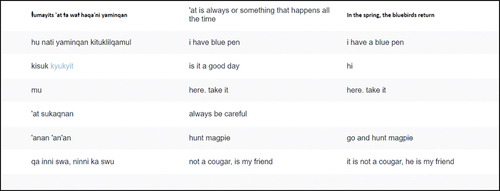

The design of the workshop scaffolded activities to be both relevant to the participant yet support the design of a database tool. The participatory discussion with teachers concerning how a language database should be put together can be challenging due to the technical nature of such systems (Christie Citation2004). Considering this, it was decided to focus on workshop activities that prompted use of the user interface ‘Record and Write’ web database tool, that would also be open-ended enough for the participant to lead the discussion. An example of these types of open-ended activities are shown in . For instance, in activity 5, participants were asked to add a pivotal glossing function (for an explanation of glossing refer to Section 4.1.1 below) that addressed an underlying grammatical foundation. This led to discussions about the different morphology of languages and the opportunities made available for teaching (see , Activity 5, see Section 4.5 below). This example illustrates how open-ended exercises can result in the discussion of complex issues that lead to a deeper understanding of the problem space (Buchanan Citation1992; Garrison Citation1995), and as a result a more robust database that has the potential to better align with individual community needs.

In this section, we present 1) the user interface of the database – ‘Record and Write’ as it was developed from the workshops, 2) the composition of the research team, 3) the selected participants and their background, and 4) an overview of the design activities used and how they were implemented.

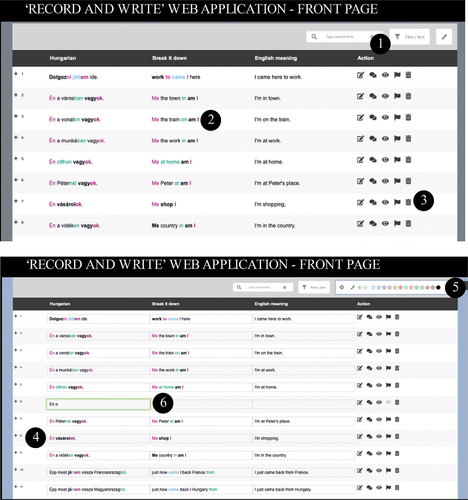

4.1. ‘Record and Write’ web application – main page

The ‘Record and Write’ Web Application is intended to serve as a database for the documentation and preservation of language, but also serve as a tool to support language learning. Below we describe the functions and features users encounter in a general workflow for the tool.

The design of the tool closely corresponded with the notion of ‘ontologically flat’ language databases. The tool strived to not have pre-defined hierarchical or linguistic structures, instead enabling community members to decide how to organise, tag, annotate and deliver their own content. For example, keywords are user-defined and all tools (including glossing (see section 4.1.1)) are optional. The tool also provides the benefit of being open-ended, enabling users to input content as they wish, rather than conforming to pre-existing categories or structures (as an example see ). Minimally, in Warrma Mangarrayi the information required in the database to support learning of Mangarrayi is an audio file, Mangarrayi transcription, and translation in English.

As an ethical consideration, the Record and Write web application is controlled by the community or individual through entering a passcode that is initially established prior to the setup of the database. Once the passcode is entered, the home page is displayed showing the glossing palate (see ), the phrases (see ) and icons of the actions that can be taken (see ), a quick search function (see ) is also included for phrases with attached keywords. When phrases are added (see ) the screen turns blue, and the glossing palate is activated.

Figure 4. Start page for the ‘Record and Write’ web application. Top: home screen 1– filter and search functions, 2 – phrase database, 3 – action icons. Bottom: edit functions activated when a phrase is added, 4 – adding a phrase, 5 – glossing palate, 6 – input boxes.

4.1.1. The glossing palate tool

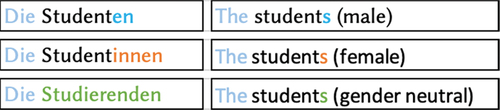

Interlineal glossing is a process used by linguists to provide detailed information about different elements of linguistic structure. The gloss is placed directly beneath the word or part of the word concerned. The terminology is often not transparent without linguistic training. For Warrma Mangarrayi, a more transparent terminology was developed along with use of colours to highlight grammatical relationships to help learners track these (Richards et al. Citation2019). There are a limited number of salient colour distinctions (around 12–13) that would allow learners to distinguish between different coded categories. This provides a limitation within the tool, as users must decide which key grammatical functions and forms, they wish to highlight for learners. These decisions differ from one language to another, and even for learning different aspects in one language. Choices will also be determined by learner preferences in different contexts. For some learners, this feature may not be considered helpful, in which case they do not have to enter any data. As an example (see ), one of the organisational differences between German and English is how German articles have different forms depending on their grammatical gender die (feminine), der (masculine) or das (neuter), whereas in English articles are non-gendered and have one form ‘the’. Understanding why the form changes is important for learners and colour could be used to show that these all correspond to ‘the’ in English. Unlike linguistic glossing that aims to be comprehensive, the glossing in Warrma Mangarrayi is more limited aiming to support comprehension and pattern recognition rather than detailed linguistic understanding.

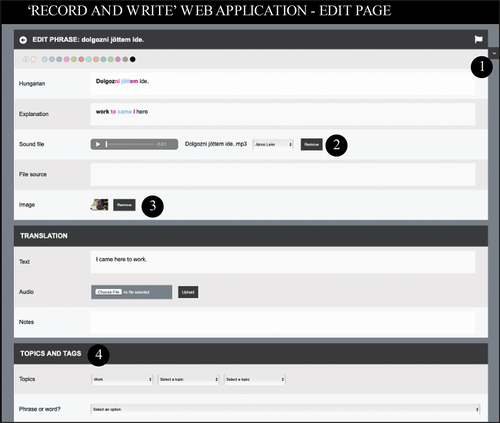

4.2. ‘Record and Write’ web application – edit page

The first action icon (![]() , see ) opens an edit screen (see ) where audio files, images, keywords, notes, and the glossing palate can be accessed.

, see ) opens an edit screen (see ) where audio files, images, keywords, notes, and the glossing palate can be accessed.

Figure 6. ‘Record and Write’ application in edit mode. Image shows major functions including 1 – arrow opens glossing palate, 2 – sound file, 3 – image files, 4 – topics and tags.

The second action icon ![]() enters a conversation screen (still under development), and the third action icon

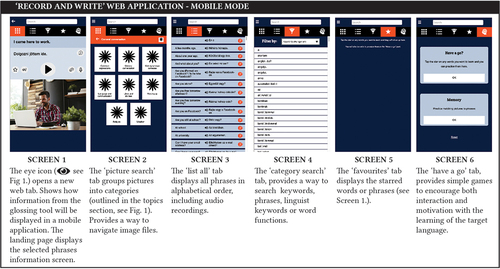

enters a conversation screen (still under development), and the third action icon ![]() shows the information converted into a mobile language learning application (see ).

shows the information converted into a mobile language learning application (see ).

Figure 7. ‘Record and Write’ web application - mobile mode. The eye icon in the main screens opens a web version of how a typical mobile application might appear. Hungarian was used as a demonstration language.

The web view of the mobile application was added after the first workshop (see ) to show how the data would be portrayed to students. Key screens show the user how images and sound files would appear (see ).

Table 1. Workshop participants overview.

4.3. Research team composition

The research team comprised a non-Indigenous language teacher and application developer who were part of the development team for Warrma Mangarrayi, a design researcher, a human-centred AI researcher, and language teachers: an instructional designer/researcher of second language learning materials (German); and teachers of the Indigenous languages used to evaluate the tool (Ktunaxa and Gathang).

4.4. Ethics process

Phase 1 was completed prior to the current study; it received institutional ethics approval for the Warrma Mangarrayi resource with Jilkminggan community members (Richards et al. Citation2019).

For Phase 2, reported in this paper, institutional ethics approval was obtained to conduct evaluation sessions of ‘Record and Write’ with language teacher participants who are also active collaborators on a range of other research projects.

4.5. Workshop participants

The team sought to include diverse language teacher perspectives to gather insights into the potential for this open-ended web-based application originally developed for Mangarrayi to scale to other language learning contexts. The study included language teachers of Ktunaxa and Gathang located in their respective communities (positioned approximately in North Western America and South Eastern Australia) and one instructional designer/researcher/teacher from Germany, also located in Australia. Each participant had previously worked with at least one person of the team prior to the workshop. Due to the remoteness of some of the participants, the workshops were conducted through a video conferencing application using the sandbox version of the user interface of the ‘Record and Write’ tool as a technology probe.

4.5.1. Workshop 1: German

The first workshop conducted was with a linguist/researcher with experience in developing pedagogically tailored instructional materials for second language learning, and in developing technologies with Indigenous language communities. Because they are not fluent in an Indigenous language, German (their native language) was used in the workshop activities. This took advantage of their first-hand knowledge of their native language (its grammar and idiosyncrasies) and provided a Global North perspective, as well as their experience with Indigenous language communities and learning technologies.

4.5.2. Workshop 2: Ktunaxa

The second workshop was conducted with a Ktunaxa teacher, who is fluent in English. They are among a few who can speak their specific dialect of Ktunaxa and are learning and teaching the language in a non-classroom context. The Endangered Languages project lists Ktunaxa as being ‘critically endangered’. It currently has 31 fluent speakers (“Did You Know Ktunaxa Is Critically Endangered?” Citation2021), covering a region of 70,000 km square region (“Ktunaxa Home | Explore | FirstVoices” Citation2021), with only a limited number of elders living in the community. Several endeavours have been initiated across the Ktunaxa language community to revitalise the language. Formal language classes have been established at ʔaq̓amnik’ School in B.C., Canada (“ʔaq̓amnik’ School | Aq’am” Citation2022), and at Salish-Kootenai-College in MT, USA (“Winter 2021 Class List – Salish Kootenai College” Citation2022). The Kootenai Culture Committee in Elmo, MT, has developed several language resources, such as dictionaries and textbooks, and employs Ksanka Language Apprentices within a programme during which apprentices are expected to focus on learning the Ktunaxa language. Since the beginning of social restrictions in North America in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, informal online classes have been facilitated on Zoom within the community, extended into formal offerings in 2023 (“Ktunaxa Language Course for Educators – CBEEN Online” Citation2022). A digital, bilingual dictionary and phrase collection is available, the ‘Ktunaxa Language app’ (“Ktunaxa Language | Aq’am” Citation2022), and a new application which aims to support young and independent learners with accessible content and playful practice mechanisms in the form of a language learning adventure game is being developed by the Ktunaxa Interactive Language Learning Collective (Torres Citation2022).

4.5.3. Workshop 3: Gathang

The third workshop was conducted with a Birrbay and Dhanggati researcher and teacher of Gathang, a language belonging to Birrbay, Guringay and Warringay people. Gathang is a language spoken in the mid-coast of what is known as New South Wales, Australia. It was known as a “sleeping language”, meaning it had no remaining fluent speakers, and few audio recordings were available. The language is being revitalised through a substantial and successful programme of work by the Muurrbay Aboriginal Cultural and Language Cooperative, Djuyalgu Wakulda Gathang language governance group, and Djarii language governance group (Radley, Ryan, and Dowse Citation2021). This work includes a 1000 word and suffix dictionary (Lissarrague Citation2010) and a formal tertiary education course. This participant was able to learn the language as part of the Gathang revitalisation process. They are now part of a current effort to ensure Gathang’s continued use, preservation, and development.

4.6. Workshop activities

The activities were developed to stimulate participants’ ideas about language tools for teaching, and to facilitate a deeper level of discourse around computer aided language learning (CALL) and data gathering tools. Through the use of a functioning prototype – the ‘Record and Write’ tool, we developed several activities (see ) that prompted our participants to discuss grammar, meaning making, culture, the role of tools to support teaching activities, resource collection and generation (Schuler and Namioka Citation1993). This was deployed as an iteration on work done by Soro et al. (Citation2016) on manned cross-cultural dialogical probes (see section 3.1.2 and 6). The activities were open-ended, although focused on the ‘Record and Write’ web application as a way of provoking teachers’ insights.

Table 2. Workshop overview.

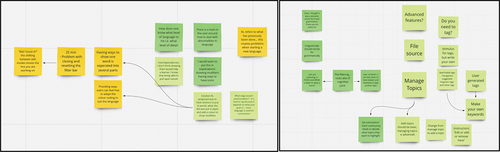

After each session, those conducting the workshop would present the findings in fortnightly meetings, where discussions would lead to organising emerging themes (see ) on a shared board.

Figure 8. Example screen shots of an analysis session using Miro board. Left: Shows ‘sticky notes’ being constructed from video data; yellow denotes pragmatic issues, green denotes issues teaching language, dark green denotes higher level questions and issues. Right: Shows themes starting to be developed through clustering of the green post-it notes.

4.6.1. Video analysis

Following each workshop, an analysis of the video was undertaken (Jordan and Henderson Citation1995). Firstly, the first author produced transcripts, logged and time stamped relevant sequences within the 5 h of workshop video to introduce in collaborative analysis sessions. Secondly, the relevant video sequences were then analysed at 2 h fortnightly meetings: Each logged section of the video was reviewed and discussed in plenum with respect to the research project questions (see Section 1). Observations, low-level codes and themes were tabled in these sessions and clustered on a shared Miro board (Miro Citation2022). The Miro board is shown in , where each activity (see ) is time-stamped and represented in frames; digital ‘sticky notes’ were generated in a collaborative activity, and initially colour-coded into three broad content areas:

Video sequences in which pragmatic interface issues emerged that teachers experienced i.e. difficulty in logging in or failing to understand what certain icons represent.

Video sequences showing issues relating to the teaching of languages.

Video sequences evidencing issues relating to how databases and interfaces push on ways to teach language in cultural settings.

Thirdly, the yellow sticky notes were either removed as they delt with technical issues with the database such as ‘Problem with closing and resetting the filter bar’ or changed into green sticky notes if the issue needs further thought or impacted on teaching issues. The green ‘sticky notes’ containing contextual quotes and possible implications were then sorted into larger emerging themes. An example of a theme group emerging is ‘Governance and transparency’ shown in (right). Finally, themes were discussed in a final 2-h meeting through a recorded online workshop, looking at some of the more problematic issues. Miro was used as a way to collectively share and discuss viewpoints of the previous workshop sessions.

5. Findings from workshops

In this section, we present three cases from our participant workshop data. The three cases selected demonstrate issues our language teachers called attention to with the ‘Record and Write’ tool in teaching a language in different cultures. Case 1 emphasises the work teachers do to communicate how a language is put together for students, and how the ‘Record and Write’ tool can both obfuscate and facilitate the process. Case 2 emphasises the work that under-resourced teachers need to perform to adjust tools which have been predominantly developed in resource-rich language domains. Case 3 emphasises the importance of recording how language is adapted and used, and the changes that occur with living languages. The cases highlight how Global North perspectives are infused into the design of tools and can introduce barriers to design activities when working across language-culture boundaries. Each case begins with a brief prologue to orient the reader to the significance of the excerpt and the resultant issues (to be discussed in Section 6).

5.1. Case 1 (workshops 1,2 & 3): open-ended prototypes create varieties of ‘fit’ and ‘misfit’ to various language learning contexts

Case 1 exemplifies how the design of an ‘ontologically flat’ and open-ended interface can support multiple ways of documenting and teaching languages, however this comes with trade-offs for the teacher. In our workshops, it emerged that there is initially a high cognitive load on a language teacher when first confronted by the open-endedness of the tool, irrespective of their cultural or language background. Teachers, when seeking to add phrases, progressively iterated through strategies of ‘fitting’ their language into the database. They skilfully considered the possibilities afforded by the tool and predicted how their students would learn language concepts. This was the case across the three workshops, whether or not the target language was undergoing revitalisation. Each language teacher had to work to ensure that the target language made sense, using different visual cues supplied in the interface (colour coding, dashes, dots, etc., see ). Teachers used the visual cues in a way that they determined could be understood and internalised by the learner rather than relying on lengthy explanations. An example of this is when in Workshop 3, a Gathang language teacher (MH-W3) works through a strategy to display and explain how ‘the whole’ language works together, relaying decisions on pedagogy.

Figure 9. Screen shot of Workshop 3 with MH-W3. MH-W3 has added glossing to the Gathang words and is working on how to convey grammar to a learner.

Figure 10. Screen shot of the ‘Record and Write’ tool as MH-W3 talks through possibilities for how different teaching methods might be conveyed through the existing database tool.

Figure 11. Screenshot from Workshop 2 with LS-W2. LS-W2 moves beyond the set activity to put their own phrases into the database.

As MH-W3 starts working on a literal translation of Ngatha birrbayga barrayga (I am on Biripi Country) into English (see ) ‘Because we have a lot of pronouns, so it makes sense, and because we have some free word order that happens, it makes sense to colour code the pronoun stuff’. MH-W3, in aiding the literal translation, puts biripi-on (see ) ‘or we would just put loc there, yeah and sometimes when people are learning a language to start with, we might use these’ (see ). MH-W3 changes the birrbayga to birrbay-ga ‘but I’m opposed to using them, I think people should learn the language whole and they should rely on interlinear glossing to see the breakdown in language in the early stages, so they understand how the whole language, you know, is working’ (Workshop 3 - Gathang).

In the above example, we see a greater emphasis on the importance of the grammatical structure, intended to bring awareness to the whole language. MH-W3 conveys this need as having a positive impact on how students learn formally, even early on: ‘…they should rely on interlinear glossing to see the breakdown in language in the early stages, so they understand how the whole language, you know, is working’. Different teaching priorities and trade-offs emerged in the other workshops. For example, KT-W1 actively spends considerable time in working with the tool, unpacking how they would show the learner how the grammar of the language is working. In Workshop 1, towards the end of the activity, KT-W1 comes to the realisation that there is a fine line between providing enough information about grammar without introducing too much complexity. This balance is required to support students to successfully pull phrases apart and put them back together in senseful and appropriate ways. In contrast, LS-W2 (workshop 2) was centred primarily on the learner being able to engage in conversations in the target language, and how an education tool might facilitate that process with the support of the teacher. For example, LS-W2 describes the need for tools to support students being able to show their methods of learning. He talks through a scenario: ‘OK she (student 1) can see my notes and see what (student 2) wrote and take [it to use]. If taking what (student 1) notes if it would help her and ignore it if it doesn’t help her. And also, it could be where, ahh, there’s a question on it like student notes. Umm OK. Can I, ah like [Ktunaxa phrase] “goodnight”. Ah, a good question that a student might ask “Is this actually for the same as the English version? When you’re going to bed?” and I would say “No, this is just for the time of day – it’s good night, it’s just a greeting”. Umm, and it’s not necessarily you’re going to bed, so that would be just a question I can answer that on, on there or have a section for questions. Uhm, instead of student notes, have a section just for questions that can go and alert the teacher when they log on or through a notification saying, “your student has a question”.’

Grammatical structure was only discussed in the workshop as part of performing activities with the prototype; the primary value conveyed was providing understanding of the language and culture through language use.

Case 1 exemplifies two findings. Firstly, to ensure teaching interfaces support the teacher in not only being able to add phrases but to choose visual cues they require to convey grammatical understanding e.g. as per the example, we see MH-W3 discussing the merits of attaching ‘loc’, ‘-‘ and on other occasions, choosing colours. Secondly, there is a trade-off here: ‘ontologically flat’ and ‘open-ended’ designs can provide an open texture of possibilities for capturing (and subsequently teaching) language. But this openness introduces a significant burden on the teacher when populating the language bank, as they now must decide how much linguistic detail should be encoded as they enter parts of speech, and the consequences of those decisions for how components of the language can (or cannot) be taught using the tool. Language applications used in teaching contexts need to manage the level of instruction to suit the progression of the learner, and the degree to which revitalisation of the language has been realised. The simplicity and open-endedness of the tool ‘pushed back’ on the language teachers, challenging them via the tool’s structural vagueness to work to ‘fit’ their contexts of learning to the various possibilities afforded by the tool.

5.2. Case 2 (workshops 2 & 3): cultural translation inherent in databases

Case 2, drawn from workshops 2 and 3, and identifies how teachers at times have had to adapt to Global North expectations of their language/culture. An example is taken from Workshop 2 conducted with a Ktunaxa teacher, highlighting how both accidental and pervasive cultural barriers get built into designs of database tools. Firstly, it shows the extent to which the context of the sentence is relied on to communicate cultural knowledge and significance, and secondly it highlights problems that arise in ‘forcing’ a translation into a dominant language such as English.

In Workshop 2, LS-W2 starts to explain how they are constantly asked by English students the word for a greeting such as ‘hi’ or ‘good morning’. “But we don’t have a word that actually says ‘hi’… right?”. To give a lexical answer that English language users expect, LS-W2 would need to misrepresent how their own culture handles situations in which people might greet each other. We see in the below excerpt how LS-W2 explains their adaption and starts to put in their own, remarking, ‘So that’s more of the, I guess, example that would fit all the criteria up there, cause yeah, the English meaning you’d say that as like “hi” type thing, but it is you’re saying “it is a good day!” Kisuk kyukyit! But we don’t have a word that actually says “hi”, right?’. MT-W2 responds, ‘Can I, sorry … just cause I’m really curious, so you have “is it a good day?” what happens if it is a bad day?’ LS-W2 then clarifies, “Um well this is actually a question, Kisuk kyukyit and you don’t answer with Kisuk kyukyit you answer with su’kni, ‘It is good!’ But if I say Kisuk kyukyit, but you really want to tell me it’s a terrible day, you would say sahani. It’s the way you answer it ‘cause it actually is saying is it a good day, but it’s the English version of ‘hi’, pretty much. Because there is no word just for hello in Kootenai”. LS-W2 further explained, ‘Since, since we’ve been colonised and learned English, a lot of people want to know “good morning” and “good afternoon” and “good evening” and “goodnight”, and we do have those … ’ (see ) (Workshop 2 - Ktunaxa).

In our workshops, a concern was quickly raised as to the alignment with English, as participants were engaged in an exercise in which they had to write a phrase in their language and then translate that phrase into English. Translation using English (or another major Western language) is often used as a pragmatic strategy to provide learners with the meaning of target language words and phrases in both digital and non-digital learning resources, also used in language dictionaries and applications (such as Memrise). The example discussed here highlights short comings of this strategy, and the unintended cultural distortion that can accompany the strategy to teach through a (however rough) correspondence to a Western language as a ‘base’.

5.3. Case 3 (workshops 2 & 3) - designing for community governance

The following case raised contrasting issues related to the governance of revitalised languages: to ensure that decisions around the management and use of language data are transparent for existing learners, and to ensure they are documented and verified for future use (“What is Data Governance?” Citation2020). We explore these two findings using examples from the workshops below.

Firstly, from the perspective of a teacher of a critically endangered language (Workshop 2), student engagement with and use of the language is of the highest importance to ensure the target language’s maintenance. An hour into workshop 2, LS-W2 raised the need for tools, when there is not a formalised source (such as when languages are being revitalised from community members) to enable students to ask questions when they encounter alternative spellings, pronunciations, definitions etc. By asking questions as they arise, teachers are then able to explain possible differences or seek further clarification. As an example, in the following description, MT is clarifying what LS-W2 has alluded to about having a ‘notes’ section in the tool. At this point MT queries the benefits of having a notes section in the tool, and what outcomes that would offer to a learning process.

LS-W2 offers further clarification to MT-W2’s conveyed understanding of a ‘notes’ section, LS-W2 explains it thus: ‘If KL-W2 was to ask me “how come? how come, uh?” this guy says it’s orange and not apple, and then I could say, oh that’s because … that’s the north and northern way, not our way’. KL-W2 agrees with LS-W2, saying ‘it’s almost like … you can use this tool (referring to the database) to have a discussion, right? If you add notes and questions then you can see like oh, wait, no I had that very different, like why? Why were you thinking this way … right? And then you can even have the whole history of that discussion in there … ’ LS-W2 adds, “Also on another good thing about the, uh, the questions part, is ‘cause like with Kootenai, one letter can change a lot of different… you can change the meaning of the sentence with one letter … ” (LS-W2).

A second perspective emerged from Workshop 3 and sits in contrast to the previous example. MH in Workshop 3 highlights the shift from the maintenance of an endangered language to an under-resourced but governed language.

‘… I guess, I get concerned with Gathang because we’re in early stages of revitalisation and people’s pronunciation sometimes isn’t great, I would prefer that verified entries would be front facing and publicly available, rather than non-verified one. So then it would be reliant on someone to be able to verify those recordings for that language being used … there needs to be some permissions or controls around you know what, what becomes public facing and what doesn’t’. Later on in the workshop MH brings up the need for governance around where certain phrases have come from. ‘… where you’ve got some notes around if there’s been any language engineering, if any decisions made by governance groups to go with one source over another’ (MH-W3).

MH-W3 and LS-W2 both raised the importance of needing to be able to use the tool within facilitated discussions with their students. Teachers expressed a need to manage how students understand the impacts of changes to maintain a current (and evolving) learning environment. For example, in LS-W2, it was explained, ‘If you add notes and questions then you can see like oh, wait, no I had that very different, like why? Why were you thinking this way … right?’ Also, MH-W3 brings up the need to explain to students why one source has been approved over another: ‘so it’s telling us why we use that word rather than another word, so if [learners] got other source material reference material like a dictionary which has three or four different words in up for the same thing’. The Gathang footprint is made up of three communities – Birrbay, Guringay and Warrimay – and there are some linguistic differences in the Gathang spoken by the different communities. A notes section would allow for explanation of these distinctions. A tool that can reflect a growing language, supports both learning objectives and documentation decisions made by the community. It does this by enabling the learner to query and discuss with their teacher as they engage with their community. A database that displays a changing and evolving language situated in community can also then provide a cohesive, personalised, remote, learning environment. Again, we see how this semi-functional tool operated as a discursive provocation for language teachers to elicit (a) cultural details that are highly relevant to the design of the database tool, and (b) design assumptions about how teachers and communities would use, and want to use, such a tool.

5.3.1. Summary

These three case studies provide a window into our data, highlighting different objectives brought forward by the participants for using an open-ended database tool for teaching. We will now discuss these issues under thematic headings: reflection of culture; grammatical accuracy; governance and transparency of language; and learner conversation support. We then discuss the central issues to emerge in consideration of the aims of project: how and what type of information should be included in a database so that it is representative of the community and the lessons that can be drawn for the design of language technologies.

6. Discussion

Our workshops, consisting of probe materials, activities, and open-ended discussion around database design, provided a way to gain insights into the needs of a diverse cohort of language teachers who are either involved in a language revitalisation process or who are part of a Global North language. Our approach used not fully functional technology probes, based on an iteration on Soro et al’s ‘cross-cultural dialogical manned probe’ (Soro et al. Citation2016). The analysis phase provided key opportunities for the team to reflect upon the assumptions and biases that were inherent in the initial design of the database tool relative to the complexitites of teaching languages at various stages of . This led to reflection by the team on what even a modest co-design intervention could reveal when moving from one language domain to another. These reflections are discussed below.

6.1. Transparency of co-design agendas

In language teaching contexts, different domain experts bring different understandings and agendas of co-design. This is especially the case in co-design contexts that involve Indigenous and non-indigenous design partners, where the value, outcome, and process of co-design has implications not only for the individual team members but the partners that they represent. In recognition of the different agendas of co-design, as a working team it became important that the co-design process was transparent including the underlying ontology that informed the design of the original tool, and further design outcomes. This included how different definitions are used, and how the tool might be appropriated for different learning needs. Our mission, as the tool develops, is to maintain the transparency of the process and that perspectives are captured, even as the tool is used, which we see supporting further co-design of learning activities.

6.2. Between probes and provotypes: a reflexive lens to identify embedded design assumptions in cross-cultural design

The ‘cross-cultural dialogical manned probe’, itself a development of cultural probes (B. Gaver, Dunne, and Pacenti Citation1999; W. W. Gaver et al. Citation2004), was designed by Soro et al. (Citation2016) to engage participants and researchers in situated conversations using ‘off the shelf’ technologies in digital design solutions. In Soro’s case, this method ultimately resulted in a situated digital noticeboard (Soro et al. Citation2017). There are several advantages of using a ‘cross-cultural dialogical manned probe’ over a cultural probe. Firstly, it invites cross-cultural conversations over a period of time, resulting in an exchange of information (mutual learning) rather than primary data collection. Secondly, Soro et al.’s (Citation2016) use of the probe with the target language provided opportunities for both participants and researchers to understand potential problems and assess the technology’s ability to be repurposed or adapted for that language. Both of these distinctions are critical for cross-cultural design, as they identify potential problems when technology is interpreted by technology developers and researchers who do not necessarily share the culture of the intended users; however, Soro et al. (Citation2016, Citation2017) analysis of their fully-functioning technology probes did not reveal potential biases inherent in the technologies. Although our initial study did not set out to reveal tensions or assumptions in our seemingly ‘ontologically flat’ database, through the process of collaboratively working with a semi-functioning database, the teachers were able to reveal and question the assumptions embedded in the technology and discuss how they impact on the teaching of their language.

The semi-functional database tool in our workshop activities provided an opportunity to identify certain assumptions about culture, language, and use, that were embedded even in supposedly ‘ontologically flat’ structures. This was not simply a consequence of having a tool that was still malleable and in development, nor of the nature of the curated activities we constructed around its potential use in the workshop; but importantly it was a consequence of the reflexive lens we employed to draw out these relevant elements of how the technology’s design intersects (or sometimes collides) with teachers’ needs. We feel this lens provides a way for the co-design community to analyse cross-cultural encounters. While we hoped a workshop would reveal new user requirements, such as language databases needing further annotation to attach important features of language that cannot be captured through linguistic glossing, this reflexive lens goes beyond just identifying new requirements, or eliciting cultural aspects from participants in the way a probe does but identifies embedded assumptions in the structures of the tool that provotypes are typically designed to explore (even though our prototype was not intentionally designed or deployed as a provotype).

The lens operates as a means of treating the cross-cultural dialogue as a reflexive process (Schon Citation1983). For example, each requirement identified is not to be seen as simply a new feature request but viewed instead as evidence of an embedded cultural assumption about a language community’s needs. Each scenario of use that is not yet adequately catered for by the design of the application is not treated as a new use case, but rather as evidence of a prior design assumption about a community’s priorities. In this way, the lens provides a means of analysing collaborative workshops not just for how they elicit information or cultural knowledge, improve a prototype, or establish functional requirements, but for how they diagnose latent assumptions that get inscribed into tools (Akrich Citation1992). In this sense, we have analysed our workshop data as if it was designed as a reflexive provocation; as if we were not just trying to understand others but trying to diagnose our own blind spots that initially prevented our technology design from anticipating the diverse community contexts and needs in the first place (Pangrazio Citation2017).

Our reflexive lens detailed in this paper, therefore, sits in a space somewhere between, and also distinct from, both provotypes and probe design methods. As a provocation, our process supported critical reflection on the relationship between databases, language, culture, and country. A relevant distinction is how this process resulted in language teachers being critical of the inherent biases of designers, underlining that the team did not have the cultural standing to ask the ‘carefully crafted questions’ (Dunne and Raby Citation2001) or expose critical ‘tensions’ (Boer and Donovan Citation2012) as provotypes are designed to do. Yet analysing our prototype as if it was a provocation did expose relevant tensions and embedded assumptions. And as a cross-cultural dialogical probe, our semi-functional database in activity promoted discussion regarding the work of language teachers using technologies. Yet because it was a prototype still in development and not yet fully functional, our co-designers would not have participated in the same ways, and our process would not have been able to uncover the same inherent biases embedded in the structures of the technology. This is distinct from Soro et al.’s work, where the identification of such assumptions was not an object of analysis articulated in their method.

6.3. Towards an ‘ontologically flexible’ database

The ‘ontologically flat’ database structure, prior to the intervention, was hypothesised to support other language communities in its ability to not pre-define, categorise, or limit the entry of text, images, or audio files (Verran and Christie Citation2007). Our co-design process showed that ‘opening-up’ the database to allow language teachers’ freedom to present their language as they would want, encouraged control over how to consider and prioritise knowledge. However, in each case, the language teacher had to work to adhere and accept the parameters of the existing database. We take this as evidence that an ontologically flat database can never be fully realised as being truly ‘ontologically flat’, especially when considering that databases are derived from an etic (culturally external) perspective, situated in Western philosophies of Aristotelian logic.Footnote2 Hierarchy and categorisations that form the basis of all databases contain inbuilt biases and assumptions which are never fully realised until their use in other languages and language contexts. An example that came out of this project is in the first iteration of the database design. English was used to annotate functions and as a target language for translation. In the original design, the database was established to organise language material using the languages spoken by the participants. When the database was generalised to new languages in our study, this bias of establishing an equivalence to a dominant language was not questioned. In this aspect, the co-design process was crucial to revealing priorities of each language teacher and how they wanted their language to be represented. The success of this process depended on maintaining the malleability of the database structure. There is a growing understanding and a deeper appreciation of how databases constrain the notion and knowledge of ‘language’ especially in our design team. This is especially the case in that databases have the potential to remove learning from being socially situated on country. And yet they remain useful, even vital, for sharing recorded language and for language practice. It remains imperative that databases are considered from the situated perspectives of learners, teachers and communities. Our co-design process offers a shift from ‘ontologically flat’ databases that do not provide the necessary embedded tools towards more ‘ontologically flexible’ databases which allow users to implement ad hoc hierarchies as needed, and respond to the supports required by language learning communities.

6.4. Four central issues for ‘ontological flexible’ database design

The insights provided by the workshops and represented in the three cases we have presented, highlight differences in the agendas that language teachers’ bring to the design of language education. The design workshops revealed how teachers’ agendas were linked to the resources they have access to, the extent to which their language is materially under-resourced, the teachers’ proficiency in the language they were teaching, and the likely difficulties they anticipated and articulated for language learners. The workshops also underscored the interdependency of language and culture within the revitalisation process, even in ways that influence pragmatic issues such as recording, classification, annotation, and logic of the presentation and organisation of languages for the purposes of teaching future students.

Our workshops uncovered four central issues to ensure databases are ‘ontologically flexible’ that were the result of the participants’ engagement in the activities: reflection of culture; grammatical accuracy; governance of language and transparency of its use; and learner conversation support. We discuss these four themes below, drawing out design implications for language tools.

6.4.1. Reflection of culture: culture is not adequately provided for in the design of tools

Language tools used in teaching contexts need to support cultural, in addition to linguistic, information. Instances that arose as ‘cultural information’ through our study included typical contexts in which the phrase might be used, any restrictions with respect to who has authority to speak the phrase or at what times, and labelling notes for when languages are translated into a dominant language that cannot accurately convey intent of the phrase. Although researchers have pointed to the dangers of employing ‘outsiders’ to construct language dictionaries (Galla Citation2018; Zaman and Falak Citation2018) such as misrepresenting nuances of culture, we encountered an extended concern regarding the construction of teaching databases that are designed to align with a dominant language such as English, even when the teacher is fluent in the target language. Language applications and dictionaries often use a common language such as English (Galla Citation2016; Pine and Turin Citation2017; Taylor et al. Citation2018; Verran et al. Citation2007), however this alignment has implications for endangered languages and database design. In two accounts, we see how English language alignment entails the potential of eroding cultural information that has clear consequences for language learning and use. Firstly, as LS-W2 explains (Section 5.2), second language learners lose the nuances of how the language is situated in that region and lose sight of the cultural rules that govern the various ways that greetings are socially organised. Amery (Citation2001) raises a similar dilemma when discussing the revitalisation process of Kaurna, where often Anglicised pronunciations of Indigenous words would be used over traditional pronunciations, leading to community members limiting the use of English until Indigenous words became fluent in use. Secondly, applications that are based on ‘dictionary’ type tools may lack the ability to convey specific important cultural insights which can result in uninformed usage. This adds to the complexity of the task for cultures to manage their own ways forward through revitalisation, with consequences for eroding connections between language and culture (Amery Citation2001). (Similar concerns about cultural dilution accompany the complexity around Indigenous dance rituals being performed out of season and context for the entertainment of tourists (Tilley Citation1997)). Within the research on technology tools for endangered languages, it is clear that although technology tools are designed to capture and support language use, cultural and contextual information accompanying the use of phrases is rarely, if ever, incorporated into the design of the tools (Christie Citation2004). This remains an open question for the design of ‘ontologically flat’ databases. If these tools are to be situated in the endangered language communities, how does/might the inclusion of accompanying cultural and contextual information impact the community’s governance of its language?

6.4.2. Grammatical accuracy: the need for grammatical detail is related to stages of revitalisation and learning needs

Language learning databases will need to provide for ways to layer grammatical detail for learners, depending on teacher preferences and revitalisation stages. In the workshops, teachers expressed needs for different levels of grammatical detail depicted in the phrases. This surfaced in two ways: When languages are at the beginning of the revitalisation process, the focus is on usage (Meighan Citation2021; Nic Fhlannchadha and Hickey Citation2018), and when languages are more established there is a stronger focus on grammatical structure; Secondly, layers should be used to support student understanding of the ‘whole’ language and to further a developing understanding of the target language’s culture. Supporting dialogue between learner and teacher encourages a reinforcing feedback loop, where eventually a critical mass of people who can speak the language can spur on the revitalisation process (Amery Citation2001).

6.4.3. Governance and transparency: endangered languages require accommodation for governance architectures

Governance protocols in language learning databases should aim to provide communities means of ensuring the legitimacy of a developing tool and its language catalogue. Within the workshops, governance emerged as an important if somewhat neglected consideration in different respects. Although much has been written about the need for local community governance (Verran et al. Citation2007), little has been discussed in the ways that this can be practically realised in educational and technological tools (Galla Citation2016). Methods of governance canvassed in our workshops included 1) documenting records/choices on the selection of phrases, if multiple versions existed, 2) providing means of ensuring recordings are verified from legitimate sources for longevity purposes, 3) ensuring learners are learning from authentic (validated) community sources, rather than, e.g. relying on ‘dictionary’ pronunciations. It was clear that the requirements for an education tool to enable and support the decisions of a community should originate from the community. Research on revitalisation processes outlines how each community needs to consider for themselves how they can determine how their language is taught, documented and dispersed (Amery Citation2001; Warner, Luna, and Butler Citation2007). Our study provides important directions for how governance can be incorporated into technological tools.

6.4.4. Learner conversation support: tools need to be designed with support for student–teacher interactions in mind

Language learning databases that are targeted to languages amid revitalisation require ways to represent changes to students. In our workshops, the revitalisation of a language was conveyed as a complex process: different dialects, pronunciations, and words/phrases may be distributed among different speakers. As the community makes governance decisions on word choice, it becomes necessary that tools reflect those decisions. Teachers advocated the need for tools to help support and manage how students understand the impacts of changes to maintain a current (and evolving) learning environment. From the literature, little is discussed around the interactions between teachers and students in revitalisation communities through tools, however meaningful interactions have long been established as ways to ensure understanding and uptake of the target language (Riestenberg Citation2020). A tool that can reflect a growing revitalised language will support both learning objectives and documentation decisions made by the community, by enabling the learner to query and discuss with their teacher as they engage with their community. A database that displays a changing and evolving language situated in community will also enable more cohesive, personalised, and remote learning environments.

6.5. Summary of design lessons from workshops

In , we present a summary of the main findings from the workshops and how these lessons might be incorporated into language learning databases.

Table 3. Design insights and lessons for language learning technology.

6.6. Limitations and future work

This project investigated possibilities for a database tool developed within one endangered language community, to scale to other language learning contexts. Towards this end, our initial investigation has been strategically broad, running workshops with language teachers of three different (and differently resourced and governed) languages. While this breadth has enabled us to quickly document diverse challenges that the interface for a language learning database will encounter in different teaching contexts, this may have come at the expense of depth – i.e. sustained use in a particular language learning context with a dedicated community. In concurrent work (for future publication), members of the research team are continuing to work with the Gathang language community to further develop the database and interface.

7. Conclusion

In conclusion, there are pragmatic lessons in adapting an ‘ontologically flat’ database shell which was designed in one community to other language communities. Digital tools can only aim to reinforce culturally situated learning and provide opportunities that give the learner autonomy. Therefore, it is critically important for designers to understand that digital tools should aim to strengthen and enhance real life cultural experience rather than be substitutes for culturally situated language learning on country (i.e. the bodily sensorial experiences of being immersed in an environment and culture).

In this paper, we have conducted a study that sits in a co-design process for a database tool that engaged teachers of diverse languages to determine if a ‘ontologically flat’ database shell, designed in one community, could appreciably scale to other language communities. In doing so, our process identified a set of challenges for the design of language learning databases for the purposes of teaching and learning. These challenges have implicated specific design lessons aimed at serving language teachers including those who are working within languages being revitalised, with the understanding that different languages can have very different (and contrasting) requirements for language database systems (). Among these lessons, some have been novel (e.g. documentation of the choice of phrases, support of teacher – student interactions, conversation support) whilst others reinforce existing priorities for language teachers (cultural annotations of, e.g. when phrases should or should not be used, community control of resources). This has underscored differences between the cultural situatedness of designers/developers in contrast to the communities involved in design processes, the linguistic and cultural assumptions embedded in the classification and compartmentalisation of language mandated by default structures of database technologies, and the practical needs of communities. Our study has been a step towards more open and inclusive design processes for creating scalable language technologies.