?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Research question

This study investigates the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 on the subjective well-being of elite athletes in Germany and their thoughts about ending their careers.

Research methods

Using survey data from athletes who are supported by the German Sports Aid Foundation (n = 1652), the study first calculates the negative income shock experienced by elite athletes during the COVID-19 pandemic and then estimates the effects on the athletes’ subjective well-being, in the form of life satisfaction. Additionally, the study estimates the potential influence of an income shock on career ending thoughts.

Results and Findings

Regression results reveal that athletes, who experienced a negative income shock in 2020 reported on average lower life satisfaction overall. Life satisfaction was lower, the larger the shock and the lower the income of the athlete. Furthermore, athletes, who had a negative income shock in 2020, were more likely to ponder ending their careers in 2020.

Implications

The paper stresses the need for better financial funding for athletes. It also adds to the literature on career endings of athletes by suggesting that financial hardship could be a determinant for athletes to end their careers. The potential subsequent increase in dropout rates not only represents inefficiency but also signifies a loss of talent.

Introduction

Over the last 20 years, a new viewpoint has emerged in the sport economics and sport management literature that has stressed the importance of athletes’ off-field well-being as being an important and previously overlooked factor for their on-field performance (Dunn, Citation2014). From a policymaker’s perspective, low athlete well-being can have severe negative consequences, such as potentially increased dropout rates (Wicker et al., Citation2020; Wright & Bonett, Citation2007).

Previous research has studied the determinants and factors that can influence athlete well-being, such as mental health and physical health (Dunn, Citation2014; Lundqvist, Citation2011). These aspects are also part of a related strand of literature that has looked into the factors that can determine the career ending of athletes (Knights et al., Citation2016; Park et al., Citation2013). With the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, new research opportunities in regards to athletes’ well-being and career ending emerged.

When in 2020 the COVID-19 pandemic hit the world, it caused most of public life to come to a halt, which led to severe consequences for sport sectors around the world. This study specifically focuses on Germany, a country where the pandemic also prompted sudden and dire actions. Professional sport events were cancelled or postponed and training facilities were forced to close at least temporarily. Many elite athletes in less commercialized sports in Germany rely on sponsorship money and income from competitive sport, which make up a substantial amount of athletes’ income (Breuer et al., Citation2018). Thus, these athletes were directly economically affected by the suspension of sport events and the closure of training facilities in the form of a negative income shock. Given these circumstances, it raises the question of whether this income shock not only decreased athletes’ well-being but also influenced them towards contemplating the ending of their careers.

To this end, this paper utilizes, adapts, and builds on the theoretical framework proposed by Ferrer-i-Carbonell (Citation2005) and Blanchflower and Oswald (Citation2004). It is based on the economic concepts of well-being and experienced utility (Kahneman et al., Citation1997). Each individual’s subjective well-being is influenced by a set of observed variables. The framework proposes that lower personal income will decrease the subjective well-being of athletes. In addition, the study builds on the existing framework by exploring the mechanism through which income shocks affect career ending thoughts. Therefore, a mediation analysis is conducted to explore the mechanism between the income shock, subjective well-being and career ending thoughts.

Hence, the purpose of this study is twofold. First, it analyzes the relationship between the income shock and subjective well-being by assessing the impact that the income shock has had on the athlete’s life satisfaction. Second, it tests whether the income shock caused German elite athletes to consider ending their careers in 2020 – a consideration that holds particular relevance if the athlete is at an atypical dropout age. Thereby, the paper adds to the growing body of research analyzing the various effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, it presents a novel extension to the literature regarding the career endings of athletes by introducing the role of financial hardship.

Theoretical framework and literature review

Research context

This study focuses on elite athletes in Germany participating in less commercialized sports such as track and field, rowing, and judo. These athletes are funded by the Stiftung Deutsche Sporthilfe (German Sports Aid Foundation (GSAF)), which is a public fund that provides financial and intangible support to elite athletes. These athletes typically earn a considerably lower income than athletes from more commercialized sports such as soccer and Formula 1 and thus require public funding. In addition, athletes from less commercialized sports often times largely rely on income from competitive sports and events, whereas athletes from more commercialized sports largely rely on contracts (Garner et al., Citation2016). Hence, athletes from more commercialized sports typically have a very different income structure than athletes from less commercialized sports. Elite athletes generally differ from the resident population (Breivik et al., Citation2009; Marsh et al., Citation1995; Wicker et al., Citation2020) as they typically exhibit greater intrinsic motivation for their work. Thus, results found in other samples cannot necessarily be transferred to samples of elite athletes.

Elite athletes, income shock and well-being

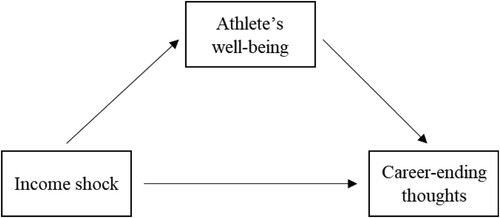

The underlying framework that is adopted in this paper for the analysis of the relationship between income shocks and well-being is an established framework in the (sport) economics literature (see, for example, Frey et al., Citation2013 and Orlowski & Wicker, Citation2019). It is based on Blanchflower and Oswald (Citation2004) and Ferrer-i-Carbonell (Citation2005) and models the relationship between a set of independent variables and subjective well-being. It relies on the idea of experienced utility, first postulated by Kahneman et al. (Citation1997). This idea proposes that an individual’s utility, or, in this case, subjective well-being, is influenced by real-time events or those that happened in the near past. Well-being is thus subject to multiple factors, one of which is the income shock. In the application of this study, well-being is in turn assumed to affect the athlete’s contentment with their career, specifically their thoughts about ending their career. This assumption relates to the general psychology concept known as the push–pull framework, which has been used in related studies analyzing the retirement decision of workers (Shultz et al., Citation1998) and has also been applied in the context of athletes (Fernandez et al., Citation2006). Low well-being is considered to be a push factor in that framework in the sense that it pushes the athlete away from the current situation and into retirement. Thus, factors that negatively impact an athlete’s well-being, such as anxiety (Fernandez et al., Citation2006) and deselection (Wilkinson, Citation2021) can indirectly lead athletes to end their careers. Hence, if the income shock negatively impacts athletes’ well-being, it might in turn impact their career ending thoughts. To this end, well-being acts as a potential mediator between the income shock and the career ending thoughts. Relevant to this study, the framework has not been applied in the context of elite athletes yet. The assumed relationship between the income shock, well-being and thoughts about career ending of elite athletes is depicted in .

Figure 1. Theoretical framework relating income shock to well-being and thoughts about career ending.

Income is typically assumed to be positively related to well-being, i.e. a greater income is associated with higher subjective well-being. There exists a set of independent variables that influence subjective well-being that has been discussed in the literature (see, for example, Argyle, Citation1999). In her analysis, Ferrer-i-Carbonell (Citation2005) used this framework to model the impact of the income of an individual’s reference group on the individual’s well-being. For the purposes of this paper, the athlete from one year ago, specifically their income, can be regarded as the reference group for the surveyed athlete. In other words, it is assumed that the athlete compares their income in 2020 to their income in 2019 and that the difference between the two figures (i.e. the income shock) impacts their well-being. The portrayed relationship is assumed for each athlete in the sample.

In the economic literature, an income shock is defined as a sizable and mostly unexpected drop in personal income (Margalit, Citation2019). This paper is concerned with negative income shocks, since the COVID-19 pandemic, as stated above, for the most part, posed unexpected financial hardship to elite German athletes and the general population. The analysis of a (negative) income shock differs from comparing high- and low-income earners as negative income shocks are usually unexpected (Banerjee et al., Citation2010; Margalit, Citation2019) and therefore can impact short-term life satisfaction (D’Ambrosio et al., Citation2020).

The concept of subjective well-being (SWB) describes individuals’ overall contentment with their lives (Diener, Citation2000). One aspect of SWB is the individual’s general contentment with life, which in the literature is called life satisfaction and is the focus of this study. Life satisfaction has been shown to be a good indicator of SWB (Bajaj & Pande, Citation2016). This procedure follows the literature, which has used life satisfaction to proxy subjective well-being before (Wicker & Frick, Citation2015).

In regards to the relationship between negative income shocks and well-being, the literature has generally found a negative impact of income shocks on well-being and is reviewed by Frey and Stutzer (Citation2002) and Clark et al. (Citation2008). Previous research from the sports-related literature in this context is scarce and has mostly focused on the impact of income on various outcome variables (e.g. Breuer et al., Citation2018; Wicker et al., Citation2018), rather than on the impact of income shocks. With the COVID-19 pandemic hitting the world unexpectedly in 2020, the resulting income shock qualifies as an unexpected, negative shock.

Concerning the well-being and life satisfaction of elite athletes, the existing literature is rather limited. Only a few studies are explicitly concerned with the life satisfaction of elite-level athletes (Malinauskas, Citation2010; Smith et al., Citation2011). Studies by Breuer and Wicker (Citation2010) and recently Breuer et al. (Citation2018) measured SWB with life satisfaction. They indicated an average life satisfaction among athletes of roughly 7.4 on a scale of 0 (totally unhappy) to 10 (totally happy), which is similar to the life satisfaction of the comparison group in the German population. Other studies looked at certain areas of an athlete’s life that are factors of overall well-being, such as physical health (Macdougall et al., Citation2016), mental health (Rice et al., Citation2016), goals (Adie et al., Citation2010) and career experiences (Gledhill & Harwood, Citation2015). In general, the main research focus has mostly been on psychological factors affecting SWB, such as motivation, coping and competition appraisals (Adie et al., Citation2010). However, the impact of an income shock caused by an external event on an athlete’s well-being remains a gap in the literature.

Recently, Wicker et al. (Citation2020) used survey data to study well-being in terms of life satisfaction of elite non-professional athletes more systemically. In their models, life satisfaction of athletes increased with income. An income shock, however, occurs due to an unexpected change in the general circumstances (e.g. a pandemic). Hence, the effect on well-being might be considerably different for athletes with high income as for athletes with low income. In addition, the analysis of income shocks differs from the analysis of high/low income, as the latter looks at inter-group differences, while income shocks consider intra-group differences. While previous research has mostly focused on psychological factors affecting athletes’ SWB, socioeconomic factors have for the most part been neglected.

Due to the results found in the literature discussed above, it is to be assumed that decreased income would lead to decreased well-being. Therefore, the first hypothesis reads as follows:

H1: A negative income shock is associated with lower athlete well-being.

H2: The larger the income shock is, the larger the decrease in subjective well-being.

H3: The decreasing effect of the negative income shock on well-being is greater for low-income athletes than for high-income athletes.

Career endings of elite athletes

Generally speaking, an athlete’s contentment with their sporting career is one aspect of athlete well-being. There are a number of studies that look at reasons for career endings (e.g. Brown et al., Citation2019; Cosh et al., Citation2013). Very few studies look at voluntary factors that might lead an athlete to end their career, the exceptions are Torregrosa et al. (Citation2004) and Park et al. (Citation2012), which highlighted the gradual process towards retirement of an athlete still in his or her career.

Most studies concerned with the career endings of athletes investigate involuntary factors, mostly from a health and medical perspective. Involuntary factors force athletes to retire at a potentially inappropriate time and with little to no personal agency. For the most part, these studies consider injuries (Cosh et al., Citation2013), mental health (Fernandez et al., Citation2006) and exclusion or deselection from the team (Wilkinson, Citation2021). There are, however, no studies yet that investigate insufficient monetary income as an involuntary reason for career endings in the context of elite athletes. Since financial hardship can lead to great distress for many athletes, the consequential assumption would be that an income shock increases the likelihood of athletes to ponder ending their careers. Therefore, the fourth hypothesis is formulated as:

H4: A negative income shock is associated with an increased likelihood of the athlete to ponder ending their career.

As mentioned above, the topic of career endings is especially relevant when the athlete is at an atypical dropout age. Since income shocks have not been analysed in the context of career endings yet, there is no existing sport economics or sport management research to draw a hypothesis from. However, previous research has found very young athletes aged 14–17 to be most susceptible to early dropout (Corrales & Olaya-Cuartero, Citation2022). In addition, young athletes have been shown to have the least income among elite athletes (Wicker et al., Citation2012). Hence, it is to be expected that the income shock would impact the youngest athletes the most. Therefore, the fifth hypothesis reads as follows.

H5: The impact of the income shock on career ending thoughts is stronger for younger athletes.

Regarding the impact on career ending thoughts, the model is extended to test if life satisfaction acts as a mediator between the income shock and the career ending thoughts. The analysis follows the results from Moksnes et al. (Citation2016), who showed that life satisfaction can act as a mediator in regards to depressive symptoms. Generally speaking, the factors that can lead an athlete to retire have been analysed on a case by case basis in the existing literature, hence there is no existing theoretical framework yet.

As outlined above, poor mental health can be a determinant for athletes to end their career (Fernandez et al., Citation2006). If the negative income shock decreases life satisfaction, and life satisfaction, in turn, increases the likelihood for athletes to ponder a career end, then life satisfaction would act as an important mediator between the negative income shock and the career ending thoughts. Therefore, the sixth hypothesis reads:

H6: Life satisfaction negatively mediates the relationship between the income shock and career ending thoughts.

Method

Data collection

In order to analyse the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on elite athletes in Germany, an online survey among athletes who are fostered and funded by the GSAF was conducted in March and April of 2021. The final sample size amounts to n = 1652. Additional information (e.g. age, sex, etc.) provided by the GSAF was subsequently matched with survey responses by the athlete’s GSAF identification number which is known only by the athlete and by the GSAF. The survey and hence the resulting dataset are anonymous, because it is impossible to uniquely identify the individual athletes with the given information in the dataset.

Questionnaire and variables

The questionnaire was based on a study by Breuer et al. (Citation2018), which for comparison reasons based their questionnaire on the German Socio-Economic Panel (GSOEP), which is the largest longitudinal survey of private households in Germany. The data and questions from the GSOEP have been used by multiple researchers concerned with individual well-being, for example, Wicker and Orlowski (Citation2021), Frey and Gullo (Citation2021), and Thormann et al. (Citation2022). Previous research has shown that the single-item life satisfaction measures from the GSOEP give very similar results when compared to multiple-item so-called Satisfaction with Life Scales (Cheung & Lucas, Citation2014). The questionnaire by Breuer et al. (Citation2018) was then extended with questions concerning the COVID-19 pandemic and future prospects of the athlete.

In the next section of the questionnaire, the athletes were asked about their satisfaction with life on a scale of 0 (=totally unsatisfied) to 10 (=totally satisfied). The questionnaire also asked the athletes to state whether they ever pondered ending their career in 2020. If an athlete stated that they considered ending their career in 2020, the athlete was then asked to state how strong the thought was, on a scale of 0 (=very weak) to 10 (=very strong). These questions were also used by Breuer et al. (Citation2017).

The remainder of the questionnaire contained socio-demographic questions, sport-related questions, such as the closure of training facilities and competitions, as well as questions concerning job status.

The additional information provided by the GSAF contains the athletes’ discipline, age, gender, and squad membership. The Olympic/Paralympic squad is the highest squad in Germany. An overview of the variables is given in . Due to the fact that the sample is heavily skewed in regards to age, three age groups are created that each contain roughly one-third of the observations of the total sample.

Table 1. Overview of variables and summary statistics for elite athletes .

Analytical framework

In order to measure the impact of an income shock on the SWB of an athlete, an analytical framework based on Clark and Oswald (Citation2002) is utilized.

(1)

(1) The dependent variable

is a measure of subjective well-being, measured as life satisfaction.

represents the main variable of interest. In the baseline analysis, the income shock variable is a binary variable which is equal to 1 if the athlete experienced an income shock in 2020, i.e. if their income decreased in 2020 compared to 2019, and is equal to 0 otherwise. The

are control variables, such as demographics, and sport-specific variables. The model is estimated with ordinary least squares (OLS).

The baseline analysis considers any decrease in income in 2020 as compared to 2019 as an income shock. In order to assess whether the impact of the income shock on life satisfaction increases with the size of the shock, further binary variables based on the size of the income shock (0%–10%, 11%–30%, 31%–50%, >50%), in regards to the athlete’s income in 2019 are constructed. Furthermore, it is examined whether the magnitude of the shock’s impact varies with income. Therefore, subsamples are constructed based on the athletes’ income. Then, Equation (1) is estimated for each of the subsamples (<10,000€, 10,000€−25,000€, >25,000€).

In order to identify if especially young athletes consider a career end, (2) is also estimated for the three age subsamples. In case the athlete’s thoughts about ending their career is the dependent variable, the models are estimated with logistic regression. When the magnitude of the thought is the dependent variable, the models are estimated with OLS.

The second set of models tests whether the income shock has had an impact on the athlete’s thoughts in regards to ending their career. To this end, the empirical approach aims to analyse the potentially mediating role of life satisfaction in regards to the relationship between the income shock and an athlete’s thoughts about ending their career. Following the approach by Baron and Kenny (Citation1986), the analysis is done in three steps with three separate models.

(2)

(2)

(3)

(3) In the first step, Equation (1) presented earlier is estimated, where subjective well-being is regressed on the income shock. In the second step, Equation (2) is estimated. The career ending variable is regressed on the income shock without subjective well-being. Finally, in the third step, in the estimation of model (3), the career ending variable is regressed on the income shock, including subjective well-being as an independent variable. Afterwards, a Sobel test (Sobel, Citation1982) is conducted in order to compare the different coefficients. The approach has been used in somewhat related contexts by Lambert et al. (Citation2009) and more recently by Satici et al. (Citation2016). Both papers studied psychological relationships by examining the mediating role of life satisfaction.

Models (2) and (3) are estimated with two different career ending variables. The first dependent variable reflects whether the athlete thought about ending their career and is thus equal to 1 if the athlete pondered ending their career in 2020 and is equal to 0 otherwise. The second dependent variable is the magnitude of the thought, a metric variable measured on a 0–10 scale. Models (2) and (3) are also estimated with the income shock category variables described above.

Results

Descriptive statistics

presents the summary statistics in the form of the mean values. The average life satisfaction of athletes is 6.95 and thus about half a point lower than the average of 7.4 from the 2018 cohort reported in Breuer et al. (Citation2018). More than one-third of athletes (35.94%) reported that they considered ending their career at some point in 2020, with an average magnitude score of 5.84.

Almost one-third of athletes (32.79%) experienced a negative income shock in 2020. Thereby 7.15% reported a negative income shock of less than 10% in relation to their income in 2019, while 11.82% had a negative income shock between 10% and 30%, 6.24% had a negative income shock between 30% and 50% and 6.61% experienced a negative income shock of more than 50%.

Athletes were also asked whether their yearly income in the respective income categories in 2020 had changed in comparison to their income in the year 2019 and if so, by how much. On average, the income of elite athletes in Germany decreased by about 2879€ (14.45%) in 2020 in comparison to 2019.

Regression results of negative income shock on life satisfaction

presents the regression results. In all models, most of the control variables have the expected signs, which can be taken as an indicator of the validity of the results. In addition, all models presented in this paper were tested for multicollinearity of the income shock variable(s). No signs of potential multicollinearity were found in any of the models. Model (1) includes the whole sample and the basic definition of a negative income shock, namely a decrease in income in 2020 relative to 2019 and therefore represents the first step of the mediation analysis. Athletes, who experienced a negative income shock in 2020 had, on average, a 0.54 lower life satisfaction than athletes who did not experience a negative income shock. This effect is significant on any standard significance level. Therefore, H1 can be confirmed. In model (2), the negative income shock was split up into different sizes of the income shock, that is 0%–10%, 11%–30%, 31%–50% and more than 50%. Generally speaking, the size of the coefficient increases with the size of the negative income shock. A negative income shock of more than 50% significantly decreases the life satisfaction of the athlete by 0.84 points. Hence, H2 can be confirmed as well.

Table 2. Regression results of the first step of the mediation analysis, income shock categories model, and models differentiated by income.

In subsamples based on yearly income in 2020 are constructed. The biggest size of the coefficient of the negative income shock on life satisfaction was experienced by athletes who earned less than 10,000€ in 2020 and this coefficient is highly significant. On average, athletes in this group who suffered a negative income shock had a significant decrease in life satisfaction of 0.63 points. For athletes who earned between 10,000€ and 25,000€ in 2020, the size of the coefficient falls to 0.52, and is significant at the 5% level. For athletes who earned more than 25,000€ in 2020, the coefficient is the smallest at 0.37 and is only barely significant. Therefore, H3 is supported in the sense that the size and significance of the coefficients increases, the lower the income of the athlete is.

Regression results of negative income shock on career ending

The second set of models concerns the relationship between the negative income shock, life satisfaction and the athlete’s thoughts about ending their career. To this end, part of the analysis tests the potentially mediating role of life satisfaction. shows the regression results of the second step of the mediation analysis ((6) and (8)), namely the regression of the career ending variable on the income shock, and the income shock categories models ((7) and (9)) for both the career ending thought and its magnitude. When considering the binary negative income shock variable in model (6), the coefficient is marginally significant. Older athletes were more likely to have pondered ending their careers, which is an unsurprising result. Also having kids, an A-level degree as well as the limited training opportunities and competitions due to the COVID-19 policy regulations made it more likely for the athlete to have pondered ending their career.

Table 3. Regression results of the second step of the mediation analysis and income shock categories models.

When splitting up the negative income shock into the different sizes of the shock in model (7), the coefficient of the negative income shock is statistically significant for those athletes who experienced a negative income shock of more than 50%. These athletes were significantly more likely to think about ending their careers than the athletes who did not suffer a negative income shock. All of the control variables that were significant in (6) are also significant in (7), which stresses the robustness of the results.

In the next question, those athletes, who in the previous question had answered that in 2020 they had pondered ending their career, were asked how pronounced the thought was. Estimations (8) and (9) of depict the results. Note, that the sample size is considerably smaller, as it only includes the athletes who had indicated to have had thoughts on ending their careers. The coefficient of the baseline negative income shock in model (8) is marginally insignificant, which can potentially be attributed to the decreased sample size. When splitting up the negative income shock into the different sizes in model (9), again the coefficient is significant for the athletes who suffered a negative income shock of more than 50%. For those athletes, the thought of ending their career was about 0.87 points higher than for the athletes who did not suffer a negative income shock but had stated that they pondered ending their career. Thus, H4 is only partially confirmed, as an income shock of at least 50% is needed to cause the athlete to ponder ending their career. An income shock of more than 10% but less than 50% decreases athlete well-being, but is insufficient to create career ending thoughts.

In , the sample is split into three age groups described earlier. The notable insight gained from comes from estimation (11). It shows a large significant and positive effect of the largest income shock category on the likelihood of a career ending thought among the youngest athletes, i.e. below the age of 20. These young athletes, who incurred an income shock of at least 50% in 2020 were about 192% more likely to have pondered ending their career than young athletes who did not incur such an income shock. Therefore, H5 can be confirmed.

Table 4. Regression results of the career end analyses for the sample split by age.

represents the third step of the mediation analysis from Baron and Kenny (Citation1986) for both the career ending thought and its magnitude. The difference compared to models (6–9) of is that in (16–19), life satisfaction is included as an independent variable. In all four estimations, life satisfaction is significant, whereas the respective income shock variables are not. The Sobel-test (Sobel, Citation1982) is significantly different from zero (p-value <0.01) for both career ending thoughts as well as their magnitude, which confirms the indirect effect of the income shock on the career ending variables via the mediator life satisfaction (the respective indirect path coefficients with t-values in brackets are β = 0.145 (4.159) for the career ending thoughts and β = 0.105 (2.916) for the thought’s magnitude). Therefore, H6 can be confirmed.

Table 5. Regression results of the third step of the mediation analysis.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic occurred rapidly and unexpectedly and had a severe economic impact on the public as well as on personal life. Since many elite German athletes rely on income generated from sport, the COVID-19 pandemic led to a sudden and unexpected reduction of income for these athletes. As such, the unexpected negative income shock experienced by many elite athletes decreased their income and thereby had a strong negative impact on the life satisfaction of athletes. This result is in line with the literature (Cai & Park, Citation2016; Clark et al., Citation2008).

The decrease in well-being should be of concern because as Wright and Bonett (Citation2007) found, lower life satisfaction can not only lead to lower sporting success, but also to increased dropout rates. This study adds new evidence to this strain of literature, as athletes, who suffered an income shock of more than 50% in 2020 were more likely to ponder ending their careers than athletes who did not experience an income shock. Regression results show that the magnitude of this thought was significant for those athletes who experienced an income shock of at least 50%. Strong sudden financial hardship thus appears to be a potential reason for athletes to end their career, or at least consider ending it. This finding presents a novel extension to the existing literature, which had covered career endings of athletes and the reasons thereof mostly in the context of involuntary and voluntary factors (e.g. Cosh et al., Citation2013; Park et al., Citation2012; Torregrosa et al., Citation2004).

The significant results of the mediation analysis show that the increased likelihood to ponder a career end is almost exclusively mediated by the decrease in well-being caused by the income shock. This finding underlines the importance of studying the determinants of and changes in subjective well-being as was done in . It also stresses the importance of well-being in the context of elite athletes, as increases in subjective well-being appear to not only lead to greater sporting success, but also to reduce premature career endings of athletes, especially at very young ages.

The sport management literature has neglected financial hardship as a potential reason for career endings of elite athletes so far, even though it is a widely discussed topic in labour economics in general (see, for example, Alam & Asim, Citation2019; Arokiasamy, Citation2013). Also, low SWB as a potential reason for career endings has not been discussed in the sport management literature. This is surprising because labour economics research suggests a causal relationship between low life or job satisfaction and turnover likelihood as well as job performance (Azeez et al., Citation2016; Judge et al., Citation2017). The finding that financial hardship increases the thoughts about career ending among top-level athletes should raise concern, especially because these athletes still have a perspective in their respective sports. It is in particular concerning for the youngest athletes, as these athletes would not have considered ending their careers if it were not for the negative income shock. A career end for athletes under the age of 20 would represent inefficiency and foregone talent (Corrales & Olaya-Cuartero, Citation2022).

As is the case with most surveys, a few caveats need to be mentioned. First, even though the sample size of n = 1652 can be regarded as sufficient when building subsamples based on income, the data runs into limitations due to smaller sample sizes. However, a comparison between the respondents in the sample and the population of elite athletes revealed that the sample represents the population of athletes reasonably well. Thus, there appears to be little concern for non-response bias.

Second, the survey makes use of single-item scales, such as the questions regarding life satisfaction and pondering a career end. The results have been used by multiple researchers from many different fields in the past (see, for example, Hajek & König, Citation2020; Schröder et al., Citation2020). Hence, even though the use of multi-item scales would increase statistical evidence and validity, the employed questionnaire has a strong empirical and historical foothold.

And third, the survey asks for athletes’ income rather than their financial resources. This might bias athletes’ responses if significant financial resources (e.g. free accommodation at their parents’ house) are not accounted for in their responses.

Conclusion

This paper builds on the theoretical framework from Ferrer-i-Carbonell (Citation2005) and Blanchflower and Oswald (Citation2004) and adapts it to the context of income shocks. The framework is then applied in the context of elite athletes. The analysis partially confirms the framework, as a sufficiently large income shock is needed in order to decrease well-being. In addition, this paper utilizes the framework by showing how the framework’s result (i.e. a decrease in well-being caused by a negative income shock) impacts an athlete’s thoughts about ending their career.

Regression results of the negative income shock on life satisfaction revealed a negative relationship. Athletes, who experienced a negative income shock in 2020 reported lower life satisfaction than athletes who did not experience an income shock in 2020. This effect increases with the size of the shock and is most pronounced for athletes at the lower end of the income scale. Additionally, the negative income shock led athletes to consider ending their career. The findings of this study have numerous practical implications. If countries want the prospect of pursuing a sporting career to not be endangered by financial hardship, measures need to be undertaken in order to ensure that athletes do not solely depend on income from competitive sport or sponsorship.

Even though income from public funds (GSAF and National Sports Fund) increased from 2019 to 2020, this study demonstrated that it was not enough to compensate for the income losses from competitive sport and sponsors/advertising contracts. In order to ensure a stable income for elite athletes in times of a crisis in the future, one potential policy implication would be the establishment of a national sport aid fund, which could be accessed in times of a crisis.

Due to the mediation effect, the study also shows that increasing life satisfaction also significantly reduces the intention of athletes to end their career prematurely. According to the results, the intentions to end a career can thus also be managed through health programmes or better training facilities, which increase the athletes’ satisfaction. In this way, an increase in life satisfaction can substitute for a higher direct financial support of the athletes. Besides the fact that low mental health is not to be desired in general, it has also been shown to reduce athlete performance (Gardner & Moore, Citation2006; Schinke et al., Citation2018) These implications are relevant for systems outside of Germany as well, as they can be applied to all non-commercialized sport systems. In these sports, the top athletes rely to a large part on money directly generated from competitive sport.

The findings also have theoretical implications, as they articulate the mediating role of well-being in linking income shock and career ending thoughts. Factors, such as an income shock, do not directly impact career ending thoughts, but instead well-being serves as a mediator in linking these factors and career ending thoughts. This implies that other factors that negatively impact well-being, could have an effect on career ending thoughts through this path as well. Additionally, instead of static income, dynamic income shocks need to be considered in analyses regarding career endings.

Future research could provide new insights by comparing the economic impacts of elite athletes to those of the comparable general population. Additionally, investigating whether the income shock experienced by elite athletes turns out to be a transitory or a long-term shock and thereby studying if athletes’ income recovers back to pre-pandemic levels present potential opportunities for future research.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (139.1 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adie, J. W., Duda, J. L., & Ntoumanis, N. (2010). Achievement goals, competition appraisals, and the well- and ill-being of elite youth soccer players over two competitive seasons. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 32(4), 555–579. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.32.4.555

- Alam, A., & Asim, M. (2019). Relationship between job satisfaction and turnover intention. International Journal of Human Resource Studies, 9(2), 163–194. https://doi.org/10.5296/ijhrs.v9i2.14618

- Argyle, M. (1999). Causes and correlates of happiness. In D. Kahneman, E. Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology. Russell Sage Foundation. Chapter 18.

- Arokiasamy, A. R. A. (2013). A qualitative study on causes and effects of employee turnover in the private sector in Malaysia. Middle-East Journal of Scientific Research, 16(11), 1532–1541.

- Azeez, R. O., Jayeoba, F., & Adeoye, A. O. (2016). Job satisfaction, turnover intention and organizational commitment. Journal of Management Research, 8(2), 102–114.

- Bajaj, B., & Pande, N. (2016). Mediating role of resilience in the impact of mindfulness on life satisfaction and affect as indices of subjective well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 93, 63–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.09.005

- Banerjee, A., Duflo, E., Postel-Vinay, G., & Watts, T. (2010). Long-run health impacts of income shocks: Wine and phylloxera in nineteenth-century France. Review of Economics and Statistics, 92(4), 714–728. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00024

- Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

- Bayer, C., & Juessen, F. (2015). Happiness and the persistence of income shocks. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 7(4), 160–187. https://doi.org/10.1257/mac.20120163

- Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (2004). Well-being over time in Britain and the USA. Journal of Public Economics, 88(7-8), 1359–1386. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-2727(02)00168-8

- Breivik, G., Hanstad, D. V., & Loland, S. (2009). Attitudes towards use of performance-enhancing substances and body modification techniques. A comparison between elite athletes and the general population. Sport in Society, 12(6), 737–754. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430430902944183

- Breuer, C., Hallmann, K., & Ilgner, M. (2017). Akzeptanz des Spitzensports in Deutschland – Zum Wandel der Wahrnehmung durch Bevölkerung und Athleten. Sportverlag Strauß.

- Breuer, C., & Wicker, P. (2010). Sportökonomische Analyse der Lebenssituation von Spitzensportlern in Deutschland. Hausdruckerei des Statistischen Bundesamtes.

- Breuer, C., Wicker, P., Dallmeyer, S., & Ilgner, M. (2018). Die Lebenssituation von Spitzensportlern und-sportlerinnern in Deutschland. Bundesinstitut für Sportwissenschaft.

- Brown, C. J., Webb, T. L., Robinson, M. A., & Cotgreave, R. (2019). Athletes’ retirement from elite sport: A qualitative study of parents and partners’ experiences. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 40, 51–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.09.005

- Cai, S., & Park, A. (2016). Permanent income and subjective well-being. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 130, 298–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2016.07.016

- Cheung, F., & Lucas, R. E. (2014). Assessing the validity of single-item life satisfaction measures: Results from three large samples. Quality of Life Research, 23(10), 2809–2818. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-014-0726-4

- Clark, A. E., Frijters, P., & Shields, M. A. (2008). Relative income, happiness, and utility: An explanation for the Easterlin paradox and other puzzles. Journal of Economic Literature, 46(1), 95–144. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.46.1.95

- Clark, A. E., & Oswald, A. J. (2002). A simple statistical method for measuring how life events affect happiness. International Journal of Epidemiology, 31(6), 1139–1144. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/31.6.1139

- Collins, J. M., & Gjertson, L. (2013). Emergency savings for low-income consumers. Focus, 30(1), 12–17.

- Corrales, D. M., & Olaya-Cuartero, J. (2022). Analysis of school-age dropout in endurance sports: A systematic review. Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 22(2), 311–320.

- Cosh, S., Crabb, S., & LeCouteur, A. (2013). Elite athletes and retirement: Identity, choice, and agency. Australian Journal of Psychology, 65(2), 89–97. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-9536.2012.00060.x

- D’Ambrosio, C., Jäntti, M., & Lepinteur, A. (2020). Money and happiness: Income, wealth and subjective well-being. Social Indicators Research, 148(1), 47–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-019-02186-w

- Diener, E. (2000). Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. American Psychologist, 55(1), 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.34

- Dunn, M. (2014). Understanding athlete wellbeing: The views of national sporting and player associations. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 18(1), e132–e133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2014.11.118

- Fernandez, A., Stephan, Y., & Fouquereau, E. (2006). Assessing reasons for sports career termination: Development of the Athletes’ Retirement Decision Inventory (ARDI). Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 7(4), 407–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2005.11.001

- Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A. (2005). Income and well-being: An empirical analysis of the comparison income effect. Journal of Public Economics, 89(5-6), 997–1019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2004.06.003

- Frey, B. S., & Gullo, A. (2021). Does sports make people happier, or do happy people more sports? Journal of Sports Economics, 22(4), 432–458. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527002520985667

- Frey, B. S., Schaffner, M., Schmidt, S. L., & Torgler, B. (2013). Do employees care about their relative income position? Behavioral evidence focusing on performance in professional team sport. Social Science Quarterly, 94(4), 912–932. https://doi.org/10.1111/ssqu.12024

- Frey, B. S., & Stutzer, A. (2002). What can economists learn from happiness research? Journal of Economic Literature, 40(2), 402–435. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.40.2.402

- Gardner, F. L., & Moore, Z. E. (2006). Clinical sport psychology. Human Kinetics.

- Garner, J., Humphrey, P. R., & Simkins, B. (2016). The business of sport and the sport of business: A review of the compensation literature in finance and sports. International Review of Financial Analysis, 47, 197–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2016.06.003

- Gledhill, A., & Harwood, C. (2015). A holistic perspective on career development in UK female soccer players: A negative case analysis. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 21, 65–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.04.003

- Grinstein-Weiss, M., & Bufe, S. (2019). Financial shocks and financial well-being: Which factors help build financial resiliency in lower-income households? Social Policy Institute, Washington University in St. Louis.

- Hajek, A., & König, H. H. (2020). Prevalence and correlates of individuals screening positive for depression and anxiety on the phq-4 in the German general population: Findings from the nationally representative German socio-economic panel (GSOEP). International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(21), 7865. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17217865

- Judge, T. A., Weiss, H. M., Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D., & Hulin, C. L. (2017). Job attitudes, job satisfaction, and job affect: A century of continuity and of change. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(3), 356–374. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000181

- Kahneman, D., & Deaton, A. (2010). High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(38), 16489–16493. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1011492107

- Kahneman, D., Wakker, P. P., & Sarin, R. (1997). Back to Bentham? Explorations of experienced utility. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(2), 375–406. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355397555235

- Knights, S., Sherry, E., & Ruddock-Hudson, M. (2016). Investigating elite end-of-athletic-career transition: A systematic review. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 28(3), 291–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2015.1128992

- Lambert, N. M., Fincham, F. D., Stillman, T. F., & Dean, L. R. (2009). More gratitude, less materialism: The mediating role of life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(1), 32–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760802216311

- Lundqvist, C. (2011). Well-being in competitive sports—The feel-good factor? A review of conceptual considerations of well-being. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 4(2), 109–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2011.584067

- Macdougall, H., O’Halloran, P., Sherry, E., & Shields, N. (2016). Needs and strengths of Australian para-athletes: Identifying their subjective psychological, social, and physical health and well-being. The Sport Psychologist, 30(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.2015-0006

- Malinauskas, R. (2010). The associations among social support, stress, and life satisfaction as perceived by injured college athletes. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 38(6), 741–752. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2010.38.6.741

- Margalit, Y. (2019). Political responses to economic shocks. Annual Review of Political Science, 22(1), 277–295. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-050517-110713

- Marsh, H. W., Perry, C., Horsely, C., & Roche, L. (1995). Multidimensional self-concepts of elite athletes: How do they differ from the general population? Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 17(1), 70–83. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.17.1.70

- Moksnes, U. K., Løhre, A., Lillefjell, M., Byrne, D. G., & Haugan, G. (2016). The association between school stress, life satisfaction and depressive symptoms in adolescents: Life satisfaction as a potential mediator. Social Indicators Research, 125(1), 339–357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0842-0

- Orlowski, J., & Wicker, P. (2019). Monetary valuation of non-market goods and services: A review of conceptual approaches and empirical applications in sports. European Sport Management Quarterly, 19(4), 456–480. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2018.1535609

- Park, S., Lavallee, D., & Tod, D. (2013). Athletes’ career transition out of sport: A systematic review. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 6(1), 22–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2012.687053

- Park, S., Tod, D., & Lavallee, D. (2012). Exploring the retirement from sport decision-making process based on the transtheoretical model. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 13(4), 444–453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2012.02.003

- Rice, S. M., Purcell, R., De Silva, S., Mawren, D., McGorry, P. D., & Parker, A. G. (2016). The mental health of elite athletes: A narrative systematic review. Sports Medicine, 46(9), 1333–1353. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-016-0492-2

- Satici, S. A., Uysal, R., Yilmaz, M. F., & Deniz, M. E. (2016). Social safeness and psychological vulnerability in Turkish youth: The mediating role of life satisfaction. Current Psychology, 35(1), 22–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-015-9359-1

- Schinke, R. J., Stambulova, N. B., Si, G., & Moore, Z. (2018). International society of sport psychology position stand: Athletes’ mental health, performance, and development. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 16(6), 622–639. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2017.1295557

- Schröder, C., Bartels, C., Grabka, M. M., König, J., Kroh, M., & Siegers, R. (2020). A novel sampling strategy for surveying high net-worth individuals—A pretest application using the socio-economic panel. Review of Income and Wealth, 66(4), 825–849. https://doi.org/10.1111/roiw.12452

- Shultz, K. S., Morton, K. R., & Weckerle, J. R. (1998). The influence of push and pull factors on voluntary and involuntary early retirees’ retirement decision and adjustment. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 53(1), 45–57. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1997.1610

- Smith, A. L., Ntoumanis, N., Duda, J. L., & Vansteenkiste, M. (2011). Goal striving, coping, and well-being: A prospective investigation of the self-concordance model in sport. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 33(1), 124–145. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.33.1.124

- Sobel, M. E. (1982). Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociological Methodology, 13, 290–312. https://doi.org/10.2307/270723

- Thormann, T. F., Gehrmann, S., & Wicker, P. (2022). The wellbeing valuation approach: The monetary value of sport participation and volunteering for different life satisfaction measures and estimators. Journal of Sports Economics, 23(8), 1096–1115. https://doi.org/10.1177/15270025221085716

- Torregrosa, M., Boixados, M., Valiente, L., & Cruz, J. (2004). Elite athletes’ image of retirement: The way to relocation in sport. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 5(1), 35–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1469-0292(02)00052-3

- Wicker, P., Breuer, C., & von Hanau, T. (2012). Is it profitable to represent the country? Evidence on the sport-related income of funded top-level athletes in Germany. Managing Leisure, 17(2-3), 221–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/13606719.2012.674396

- Wicker, P., Dallmeyer, S., & Breuer, C. (2020). Elite athlete well-being: The role of socioeconomic factors and comparisons with the resident population. Journal of Sport Management, 34(4), 341–353. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2019-0365

- Wicker, P., & Frick, B. (2015). The relationship between intensity and duration of physical activity and subjective well-being. The European Journal of Public Health, 25(5), 868–872. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckv131

- Wicker, P., & Orlowski, J. (2021). Coping with adversity: Physical activity as a moderator in adaption to bereavement. Journal of Public Health, 43(2), e196-e203. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdaa059

- Wicker, P., Orlowski, J., & Breuer, C. (2018). Coach migration in German high performance sport. European Sport Management Quarterly, 18(1), 93–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2017.1354902

- Wilkinson, R. J. (2021). A literature review exploring the mental health issues in academy football players following career termination due to deselection or injury and how counselling could support future players. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 21(4), 859–868. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12417

- Wright, T. A., & Bonett, D. G. (2007). Job satisfaction and psychological well-being as nonadditive predictors of workplace turnover. Journal of Management, 33(2), 141–160.