ABSTRACT

This paper is based within the framework of step-by-step approach to teaching legal translation. The underlying philosophy behind this approach is that when specific aspects of legal translations are tackled in isolation and trainees become aware of the pitfalls involved and the possible solutions, this helps them in further training as well as in their professional practice. Drawing on this assumption, this paper introduces a case study dealing with understanding and interpretation of English legal texts from the classroom perspective. The paper presents a number of problems that pose difficulties to trainees and proposes exercises to help them overcome such problems in a systematic way. Although this paper uses Czech as a target language, the exercises can be adapted to teach legal translation from English into other target languages. The issues have been selected based on the author’s experience with addressing recurring problems faced by legal translation trainees. Such issues include understanding complex sentences showing all-inclusiveness and syntactic discontinuities, legal cross-referencing expressions (e.g. subject to and without prejudice to) or conjunctions whose meaning may not be transparent (e.g. provided, however, that).

1. Introduction

There is a general consensus that legal translation requires ‘special skills, knowledge and experience on the part of the translator … ’ (Cao Citation2007, 3). While experience is something that cannot be taught, skills and knowledge can, and should, be addressed in a legal translation classroom. The greater the competences, experience, and knowledge of translators, the easier the decision-making process – which is at the heart of translation – will be (Way Citation2014, 141). There is also a broad consensus about the specificity of legal translation within translation studies and the need for specific, structured approaches to decision-making, competence development and training in this area (see Cao Citation2014; Prieto Ramos Citation2014).Footnote1

In terms of the teaching methodology applied in this study (i.e. the approach as defined by Jack and Rodgers Citation2014, 20–21), the exercises we will propose are anchored in constructivist approaches to translator training (see Kiraly Citation2010) emphasising the authenticity of the material usedFootnote2 and the collaboration of the learners. Where appropriate, the exercises are conceived as pair work or group work exercises, with the teacher only serving as a guide who facilitates learning. The approach thus fosters the collaborative knowledge building of learners and teachers. In many of the exercises, the role of the teacher is to provide scaffolding since, as Way (Citation2014, 139) notes, ‘scaffolding and classifying problems and processes enables students to progressively acquire the necessary skills to justify their decisions … by basing their decisions on a particular subcompetence skill … ’.

An issue that could be raised about the proposed approach is the lack of the big picture that is typical of holistic approaches to translator training as reflected e.g. in project-based or situated learning (cf. e.g. Biel Citation2011; Lisowska Citation2019). The underlying assumption behind our proposal is, however, that when the subcompetences or skills are identified as a challenge for a particular trainee or a group of trainees, and they are addressed and practiced in isolation, trainees will have a better chance to employ the actual skill than when addressing the issue as soon as it appears in a legal translation assignment (e.g. Klabal Citation2018 on the use of shall). In other words, the approach outlined in this paper is not contradictory to the holistic methods and principles of situated learning, but rather complementary to them, and aims to provide trainers with materials that may be used to address specific problem areas in the classroom.

One of the major challenges that legal translators and legal translation trainees face is understanding legal texts and piercing their seemingly impenetrable language in many cases. As Almlund (Citation2000, 83) puts it, ‘problems of text comprehension are obstacles to the unexperienced or semi-professional translator’. The problem is not, however, merely the legal jargon and terminology, since once terms are identified, their meaning can be established e.g. by comparative conceptual analysis. What causes more problems is the structure and the reasoning that must also be understood, as well as typical intertextual and interdiscursive devices, which, as Bhatia (Citation1998) argues, create specific problems in their construction, interpretation, and use. Any understanding is conditioned by legal knowledge that makes it possible to arrive at a legal interpretation of what was expressed in the source text (ST) (cf. Falzoi Citation2003, 103).

2. Interpretation of legal texts

Both in translation and in law, interpretation may be defined in several ways. In law, it may be defined as a process of giving meaning to a legal rule (cf. Tomášek Citation1991, 148) or an activity whose purpose is ‘to ascribe the meaning to, or inscribe the meaning in, the text’ (Phillips Citation2003, 90).

Given the importance of interpretation in law, it has been addressed by many authors. As noted by Chromá (Citation2014, 38), the interpretation rules are also system-bound, and may thus differ between legal systems. In the Czech context, for example, legal interpretation methods have been discussed in relation to legal translation by Tomášek (Citation2003) and Škrlantová (Citation2005). However, as mentioned by Djovčoš (Citation2008, 24), time constraints do not usually enable the translator to carry out such an in-depth analysis of a legal text as may be required for legal interpretation.

Tomášek (Citation1991, 147) makes a distinction between two major types of interpretation: grammatical (semantic) and logical. He claims (Citation1991, 149) that whereas the former is useful for the interpretation of concepts (and is therefore more closely related to comparative conceptual analysis), the latter is to be used for the interpretation of legal rules, and by extension, legal texts. It is precisely logical interpretation that will be addressed in some of the exercises presented here. For her part, Chromá (Citation2008, Citation2009, Citation2014) makes a distinction between semantic and legal interpretation. She defines semantic interpretation (Citation2009, 30) as assigning the meanings to words ‘which [are] considered to be the most “usual” or a meaning regardless of context’, while legal interpretation involves considering the context when looking for adequate meaning.

2.1. Interpretation and legal translation competence

The definition of legal competence by Šarčević (Citation1997, 113) makes an explicit reference to ‘full understanding of legal reasoning and the ability to solve legal problems, to analyse legal texts, and to foresee how a text will be interpreted and applied by courts’. Of the legal translation competence models, the model developed by Piecychna (Citation2013) – which is hermeneutical in nature – includes the ability to interpret and analyse a text as part of the psychological, thematic, and textual sub-competences, but, rather surprisingly, not as part of the linguistic sub-competence. On the contrary, Soriano Barabino (Citation2016, 148) includes ‘the ability to understand texts written in legalese’ as part of communicative or textual competence. It can be argued that it is not only texts written in legalese that pose a challenge, since any legal text – however plainly drafted it may be – can pose a challenge for understanding. The use of legalese is rather an added challenge.

How much interpretation must be carried out by a legal translator is, however, often disputed. Martínez Carrasco (Citation2019, 275) notes that the requirement postulated by Piecychna (i.e. to be able to interpret the text as a lawyer) is in contradiction to the opinions of Šarčević (Citation1997, 91), or Cao (Citation2014, 109), who claim that a legal translator should be able to grasp legal meaning as intended by the original drafters but refrain from interpreting the text in the legal sense.Footnote3 On the other hand, Joseph (Citation1995, 33–34) argues that translators should interpret the legal text rather than ‘merely translate [it]’ and proposes that translators should make stylistic, semantic, and intellectual interventions in the text to the extent that is necessary. These views are only seemingly in conflict since the term interpretation may be understood in a number of ways. Chromá (Citation2009, Citation2014) stresses the importance of interpretation in legal translation, which has a twofold role. First, there is the interpretation of the legal text by the legal translator, and second, there is the interpretation of the target text by its recipients. According to Chromá (Citation2009, 29), there are objective and subjective factors that condition the interpretation by the translator and its result. The objective factors comprise the quality of the drafting and clarity of the ST and its topic and textual genre, while the translator’s competence, with all its sub-competences, represents the subjective factor. What is required of translators in this respect are both semantic and legal interpretation skills, which – as Chromá (Citation2009, 29) believes – are part of the subjective factors, or grounded understanding. This term was introduced by Stolze (Citation2011), who argues that it may prevent some issues of misinterpretation in translational reading (Citation2011, 114).

The question is how deep the reading of a legal text by a legal translator must be, and what legal interpretation skills, and thus training, legal translators need. For example, Puig (Citation2017, 888) argues that the reading of a translator must be deeper than usual reading. According to Northcott and Brown (Citation2006, 374) translators should ‘learn to think like lawyers in order to understand legal texts’, which is a call for training in legal reasoning. Chromá (Citation2008, 301) argues that the most important part of legal translation is to understand the text fully because only such full understanding makes it possible to transfer the information into the target language (TL) precisely and comprehensibly. Similarly, Prieto Ramos (Citation2011, 13) argues that legal translators need to ‘acquire sufficient legal knowledge in order to situate the documents in their legal and procedural context, as well as to grasp the effects of the original and the target text’. Chromá’s focus stays mainly with the interpretation of terms and lexical items, which may be challenging as a result of their polysemy, conceptual incongruity, etc. Terminological issues have been extensively dealt with in legal translation studies, including from the training perspective (e.g. Janigová Citation2023; Klabal Citation2022; Soriano Barabino Citation2016). This paper focuses on the interpretation (and understanding) of other components of legal texts, which has not received as much attention so far.

2.2. Interpretation as part of the legal translation process

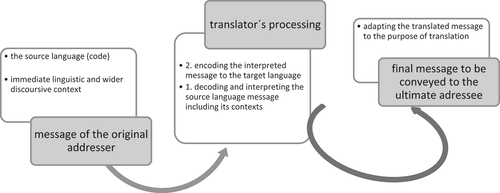

Interpretation is included in most models of the legal translation process. Chromá (Citation2014, 29) identifies five stages of the process, as shown in . The distinction between decoding and interpretation as two separate stages clearly indicates that the understanding of a legal text by a legal translator must go deeper. The difference between understanding and interpretation has been addressed by a number of authors. Šarčević (Citation1997, 92) sees understanding as an automatic cognitive operation, while interpretation starts only once the reader needs to think about the meaning of a text caused by ambiguity or other interpretative problems. Ortega Arjonilla (Citation1996) identifies three stages of the legal translation process: (1) semasiological, (2) interpretation, and (3) onomasiological. As the diagram below shows, legal translation involves interpretation and a legal translator may only translate into the TL as much as they are able to interpret in the source text, or, as Stolze (Citation2011, 74) puts it, ‘translators will never translate other than what they have understood beforehand, what is now cognitively present in their mind’. In a way, interlingual legal translation involves an intralingual translation in Jakobson’s terms (cf. Chromá Citation2011, 32), which is the first but also the key stage of the process.

Figure 1. The legal translation process (Chromá Citation2011, 34).

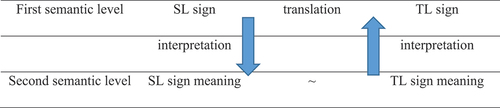

Yet another model of interpretation applicable to legal translation was introduced by Tomášek (Citation1991, 148–149) and it is depicted in . In his model of the legal translation process, the translator should use legal metalanguage to compare the meaning of the legal rules in the source and target languages and legal systems. In other words, Tomášek argues (Citation1991, 148) that proper legal translation should involve both an intersemiotic translation (i.e. translation from one sign system into another, i.e. from Czech into English and vice versa) and an intrasemiotic translation (i.e. ‘translation’ within legal language from the first semantic level to the second semantic level), which corresponds to the process of interpretation.Footnote4

Figure 2. The translation process (Tomášek Citation1991, 149).

3. Exercises to develop understanding and interpretation

This paper presents a series of exercises aimed at making trainees familiar with some of the issues that legal translators face when it comes to understanding and interpreting legal texts drafted in English.Footnote5 Chromá (Citation2008, 309) argues that when interpreting a legal text, the translator will try to identify the most likely meaning which can be transferred into the TL. In line with Djovčoš (Citation2008, 25), it is believed that if legal translators become familiar with at least the most frequent interpretative issues in legal translation, such steps could later be performed unconsciously.

An added difficulty that translators working with English face is the abundance of source texts drafted in English by non-native speakers, which is a result of the role of English as the lingua franca of legal communication. This has numerous implications, e.g. the use of terminology that is not native in English – which is traditionally a language of common law – as discussed by e.g. Kocbek (Citation2005), and the use of non-native structures, as well as frequent interference with the native language of the drafter. Therefore, the exercises in this paper involve not only authentic English texts drafted by native speakers, but also texts drafted by Czech lawyers/translators in English, as well as by speakers of German, Dutch, etc.

Many of the exercises in this paper will involve reformulation, or simplification, which has been promoted by a number of authors (e.g. Sparer Citation1988) as a guarantee of understanding since only what has been understood can be reformulated (cf. Falzoi Citation2003, 106).Footnote6 In essence, the approach corresponds to intralingual translation as discussed above.

shows an overview of the exercises proposed in this paper together with the objective of each exercise and its recommended classroom use. Pair work or group work is suggested for exercises when the trainees themselves can be expected to arrive at relevant conclusions with the teacher only serving as a facilitator, whereas individual exercises are proposed for more challenging tasks where the trainees are encouraged to engage in self-reflection, but the follow-up discussion is more effective in-class under the teacher’s supervision.Footnote7

Table 1. Overview of exercises proposed.

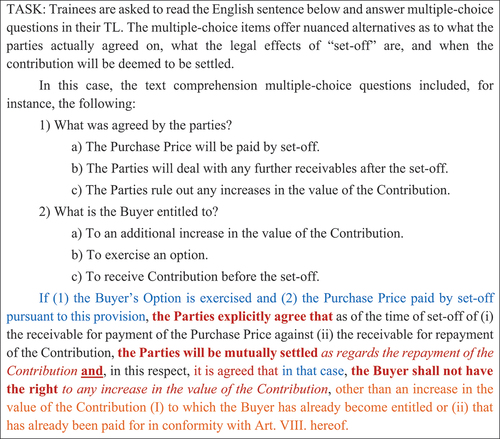

3.1. Exercise 1: understanding a legal text

This exercise aims to test the trainees’ understanding, or, more precisely, holistic pre-understanding. Stolze (Citation2011, 82) argues that it is only once a text is understood holistically that it is possible to go back to the text level to find certain words or sentences which had induced the understanding. The understanding must be content-oriented (cf. Stolze Citation2011, 105), with the semantic and stylistic aspects being more important than syntax, grammar, and pragmatics. The question that must be constantly asked by the translator is ‘What is the text saying?’. A sample task is provided in .

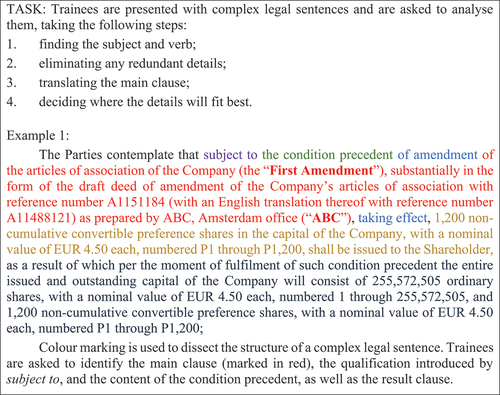

3.2. Exercise 2: dissecting complex syntax

Complex sentence structures are a typical feature of legal language in general, and English legal language in particular, with sentences showing ‘considerable complexity and length’ (Cao Citation2007, 21). The complexity is given both by a high number of qualifications and frequent syntactic discontinuities (cf. Bhatia Citation1993, 110–113). Very often, it is difficult for trainees to identify the basic structure,Footnote8 but structural interpretation of a text genre is – according to Bhatia (Citation1993, 29) – important since it highlights the cognitive aspects of language organisation. When trainees learn to cope with the structural organisation of legal texts, it will help them in translation jobs they may be assigned in the future since specialist writers tend to organise the genres in a fairly consistent way (cf. Bhatia Citation1993, 29).

By way of introduction to the analysis of complex legal sentences, trainees are presented with the sentence from the previous exercise and its atomisation, with different structural elements highlighted in different colours. This example is then used to discuss how trainees should proceed when translating the sentence into their TL. This is followed by a series of exercises in which trainees are asked to perform such dissection themselves (see for a sample task).

A variety of tools is used to analyse the complex structure of an ST. For example, Chromá (Citation2008, 305) talks about sentence patterns visualising information. Other methods include an analysis of the syntactic constituents following Lehto (Citation1992, 199–200), or analysis of cognitive structuring, proposed by Bhatia (Citation1993, 32–33). Using a legislative provision, Bhatia identifies two types of moves, namely legislative provisions and specifying provisions that show both high complexity and variety since they interact with the main legislative provision in various positions and answer a number of questions that may be asked in the respective context. In addition to qualifications, such an analysis may also be used to tackle binomials and multinomials as, in fact, shown in , which contains an example of sentence visualisation. The presentation of model analyses is followed by exercises in which trainees are asked to analyse the structure themselves (see for a sample task).

Figure 5. Long sentence analysis (Matochová Citation2018, 21).

Such exercises also teach trainees to approach complex texts with more liberty and confidence, and to get rid of the idea that the structure of the ST must always be closely followed, which is in line with the importance of reformulation as stressed above.

3.3. Exercise 3: cross-referencing

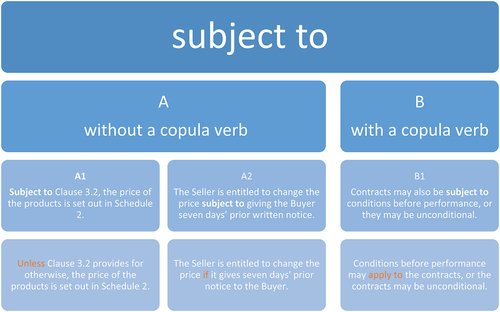

Anyone interpreting a legal text must have an understanding of the relations between individual statutory or contractual provisions and the linguistic devices employed to express such relations, the translator being no exception in this respect. In fact, their interpretation may be more difficult for translators since Bhatia (Citation1998) argues that legal specialists may find such devices relatively manageable to cope with thanks to their extensive training and experience. One such cross-referencing expression, also called limiting clauses by Cao (Citation2007, 95), or devices for defining legal scope, is subject to. The difficulty in grasping and translating this kind of expression can be compounded by its polysemous nature. The exercise in is designed to make trainees aware of the usage of subject to, and its translation into their TL.

Whereas the first use is a case of cross-referencing, which signals that Clause 2.2 introduces an exception,Footnote9 the latter use means is governed by, etc. is used to present a strategy for establishing the meaning. First, the differentiation between the use of subject to with or without a copula verb must be established (A or B). Then trainees are asked to rephrase all the sentences in the example. This should enable them to see that the sentences under A may be rephrased as a conditional clause, whereas the sentences under B may be rephrased using the verb apply, as shown in . The rephrased sentences are then used as a basis for eliciting possible translations into Czech. Other reformulation strategies are available, and may be useful for translators. Aitken and Butt (Citation2004, 90) give the example shown in .

Table 2. Reformulation of sentences with subject to.

Once subject to has been mastered, trainees are introduced to other cross-referencing expressions such as notwithstanding or without prejudice to, as well as provisos. Trainees are also made aware of their inconsistent use, even in EU documents, as noted by Štědrá (Citation2017).

3.4. Exercise 4: complex conjunctions

Cross-referencing words are not the only issue when trying to understand legal texts. Legal language is also rich in conjunctions that are otherwise not used frequently in everyday language. Alcaraz Varó and Hughes (Citation2002, 20) argue that translators should pay special attention to complex conditions with a number of hypotheses and a mix of negative and positive possibilities. Conjunctions posing interpretative problems include, without limitation, to the extent that, provided that, or except as ().

3.5. Exercise 5: understanding provisos

A provision which causes significant trouble is what is called the proviso. They are considered by some authors as a traditional feature of legal drafting (e.g. Aitken and Butt Citation2004, 86) and, as argued by Bhatia (Citation1993, 118), they are an example of a lack of consistency in using linguistic resources where a more consistent use would ‘create fewer problems of interpretation both for specialist and non-specialist readers’. Fox (Citation2008, 97) defines a proviso as a clause which begins with ‘provided’ or ‘provided, howeverFootnote10; its purpose is to override the concept that immediately precedes itFootnote11 or make a phrase conditional upon what follows after it (cf. Wiggers Citation2011, 103). The problem with provided that is the fact that it is not used strictly in this sense, but also to introduce exceptions, limitations, or qualifications of the preceding phrases, or even a new provision independent of the main clause as illustrated in . Fox (Citation2008, 97) also notes, however, that very often provisos are used incorrectly in conditional clauses as a substitute for ‘to the extent that’ or ‘if’.

Table 3. Overview of the use of provisos in legal drafting.

The example in shows a strategy promoted by Aitken and Butt (Citation2004, 87) according to which any exceptions should appear in the part of the sentence to which they relate. The last sentence could thus be rephrased as A member, other than a member of 40 years’ standing, must pay … and its translation from English could go along these lines.

3.6. Exercise 6: interpretation and construction provisions

Many contracts, as well as other binding legal texts, also include a number of definitions and interpretation/construction provisions. Sometimes, such provisions define metalanguage used throughout the legal document or stipulate interpretative rules for such metalanguage.Footnote12 In these cases, they may require a specific strategy on the part of the translator. While for the recipients of the ST, such provisions amount to an instruction as to how to read (or interpret) the language of the ST, for the translator, such provisions also amount to an instruction as to how to deal with such language in the translation, and render it accordingly in the TL, which might require a certain level of adaptation. Translators thus need to be aware of both perspectives.

In , it makes no sense to translate the part in bold into the TL and it would, in fact, be impossible to do so unless the TL also makes use of equivalent referencing words. Rather, the clause must be seen by the translator as an instruction to identify all instances of such here-referencing words in the SL and translate them according to the instruction, i.e. as a reference to the contract as a whole, rather than a single clause. There are no such pro-formas other than possessive pronouns used in Czech, and their meaning must, therefore, be made explicit in translation. For example, hereunder in an assignment clause (‘None of the Parties hereto shall be entitled to assign any of its rights and delegate any of its obligations hereunder without the prior written consent of the other Parties’.) must be translated as závazky z této smlouvy (under this Agreement), rather than závazky podle tohoto článku (under this clause).

Similarly, the following provisions include a number of hints to be used by the translator:

In each Contract Document: (i) ‘include(ing)’ means ‘include, but are not limited to’ or ‘including, without limitation’; (ii) ‘or’ means ‘either or both’ (‘A or B’ means ‘A or B or both A and B’); (iii) ‘e.g’. means ‘for example, including, without limitation’; and (iv) ‘written’ or ‘in writing’ includes email or facsimile communication, in the absence of any express statement otherwise.

The words ‘to the extent’ when used in this Agreement shall be deemed to be followed by the phrase ‘and only to the extent’. Unless the context requires otherwise, references in this Agreement to Articles, Sections, Exhibits, and Schedules shall be deemed to be references to Articles and Sections of, and Exhibits and Schedules to, this Agreement and Exhibits and Schedules to this Agreement shall be deemed to form part of this Agreement.

For example, the rule under (ii) is an instruction for a translator translating the document into Czech not to use commas preceding nebo (the Czech equivalent of or) since it has a conjunctive meaning.

3.7. Exercise 7: interpreting the verb to deem

Although it has been argued above that translators are usually not required to have the interpretation skills of lawyers, there are instances where such skills may be useful, not to say indispensable. This exercise aims to raise trainees’ awareness of one such case. Legal theory both in civil law and in common law draws a distinction between rebuttable and conclusive (irrebuttable) presumptions and legal fictions. shows the definitions and examples of each of these as presented to trainees.

Table 4. Overview of legal presumptions and legal fictions and the corresponding linguistic forms.

The problem which requires the translator’s interpretation, or understanding of the differences, is caused by the fact that documents and legislation drafted in English do not use a single verb to express presumptions or legal fictions, and some verbs, such as deem, may be used to express any of these. Therefore, legal translators working from English into Czech, or another TL, must understand the difference, and choose the TL verb accordingly ().

To reinforce the trainees’ ability to distinguish between the individual cases, other verbs from (e.g. to be regarded as) may also be used, as well as examples from contracts where deem may also carry a number of meanings, as discussed by Aitken and Butt (Citation2004, 91). A sample task is shown in .

4. Conclusions

This paper has presented a step-by-step approach to teaching legal translation, taking understanding of English legal texts as a case in point. It illustrates the relevance of understanding and interpretation in the process of legal translation, and how much interpretation is actually expected on the part of translators, by proposing a series of exercises that may help trainees understand complex legal sentences better, as well as raise their awareness of a number of legal expressions that may be tricky in translation, but could go unnoticed if not explicitly brought to the trainee’s attention. The variety of the issues tackled is not exhaustive and other functional elements could be included (e.g. expressing lists). In a way, the approach proposed in this paper may also be seen as a response to Biel (Citation2011, 165), who called for ‘more exchange of best practices’ to ‘serve as a point of reference or benchmark for legal translation teachers’.

Trainers may use the material directly, adapt it to their language pair, or possibly develop similar exercises for other legal language features they, or the trainees, may find challenging. The proposal may also be viewed as a menu from which trainers may cherry-pick ideas and exercises depending on their teaching context and needs.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. The paper is based on a chapter of an unpublished doctoral dissertation defended by the author (Klabal Citation2020).

2. Unless expressly specified otherwise, the examples used in this paper come from authentic documents translated by the author.

3. This is a view often held by legal professionals, who, as noted by Bestué Salinas (Citation2019, 144), ‘tend to oversimplify the task and consider that legal hermeneutics only comes into play once the translation is completed’. This paper tries to show that hermeneutics is an intrinsic part of the legal translation process.

4. The importance of such a process as part of legal translation is emphasised by other authors as well, e.g. Smith (Citation1995) refers to intralingual translation as a process of translating the legal language into the standard language.

5. The label ‘English legal texts’ is used in this paper to refer to any legal texts drafted in English both by native and non-native authors.

6. To support the argument in the classroom, a parallel could be drawn to the concept of deverbalisation in interpreting. While the terms of art in a legal text are transposed into the TL using conceptual analysis or established equivalents, the rest of the ST language is deliberately forgotten and the meaning is recreated in the TL using authentic TL language, which may eliminate SL interference (see Lederer Citation2003).

7. The exercise type is merely a recommendation based on the author’s experience. Depending on the trainees’ level and expertise as well as the classroom dynamics, individual exercises may be used for pair work, or assigned as individual homework to be discussed in pairs or groups in class.

8. This also becomes evident in the process of specialised translation as described by Grygová (Citation2010, 207), who identifies the following stages: (1) global understanding of the ST, followed by its atomization into (small) translation units, (2) drafting a ‘raw’ target text (TT), and finally (3) adjusting the TT to the needs of the readers.

9. Cao (Citation2007, 95–96): relationship between master provision and subject provision.

10. Aitken and Butt (Citation2004, 86) note that provided always that and provided nonetheless that are also found.

11. In this respect it is similar to notwithstanding.

12. Construction provisions in contracts are not the only context where legal translation trainees may encounter the use of metalanguage. Similar situations may also appear when translating multilingual legislation, or case-law involving a linguistic issue. Parallels may be drawn and comparisons established to make trainees aware of the strategies that are available to deal with such issues in different genres and for different purposes.

References

- Aitken, J. K., and P. Butt. 2004. Piesse: The Elements of Drafting. 10th ed. Pyrmont: Lawbook.

- Alcaraz Varó, E., and B. Hughes. 2002. Legal Translation Explained. Manchester: St. Jerome.

- Almlund, Å. 2000. “Semantic Roles in Expert Texts - Exemplified by the Patient Role in Judgments.” In Language, Text, and Knowledge: Mental Models of Expert Communication, edited by L. Lundquist and R. J. Jarvella, 83–96. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Bestué Salinas, C. 2019. “A Matter of Justice: Integrating Comparative Law Methods into the Decision-Making Process in Legal Translation.” In Research Methods in Legal Translation and Interpreting: Crossing Methodological Boundaries, edited by Ł. Biel, J. Engberg, R. M. Ruano, and V. Sosoni, 130–147. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Bhatia, V. K. 1993. Analysing Genre: Language Use in Professional Settings. London: Longman.

- Bhatia, V. K. 1998. “Intertextuality in Legal Discourse.” The Language Teacher 22 (11): 13–18.

- Biel, Ł. 2011. “Professional Realism in the Legal Translation Classroom: Translation Competence and Translator Competence.” Meta: Translators’ Journal 56 (1): 162–178. https://doi.org/10.7202/1003515ar.

- Cao, D. 2007. Translating Law. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Cao, D. 2014. “Teaching and Learning Legal Translation.” Semiotica 2014 (201): 103–119. https://doi.org/10.1515/sem-2014-0022.

- Chromá, M. 2008. “Semantic and Legal Interpretation: Two Approaches to Legal Translation.” In Language, Culture and the Law: The Formulation of Legal Concepts Across Systems and Cultures, edited by V. K. Bhatia, C. N. Candlin, and P. E. Allori, 303–316. Bern: Peter Lang.

- Chromá, M. 2009. “Semantic or Legal Interpretation: Clash or Accord?” In Legal Language in Action: Translation, Terminology, Drafting and Procedural Issues, edited by S. Šarčević, 27–42. Zagreb: Nakladni zavod Globus.

- Chromá, M. 2011. “Synonymy and Polysemy in Legal Terminology and Their Applications to Bilingual and Bijural Translation.” Research in Language 9 (1): 31–50. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10015-011-0004-2.

- Chromá, M. 2014. Právní překlad v teorii a praxi: Nový občanský zákoník. Prague: Karolinum.

- Djovčoš, M. 2008. “Pragmatika prekladu právnych textov.” In Od textu k prekladu II, edited by A. Ďuricová, 23–29. Prague: Jednota tlumočníků a překladatelů.

- Falzoi, C. 2003. “Consideraciones teóricas para la elaboración de un proyecto didáctico de la traducción jurídica.” Revista de Lenguas para Fines Específicos, (10): 99–114.

- Fox, C. M. 2008. Working with Contracts: What Law School Doesn’t Teach You. 2nd ed. New York: Practising Law Institute.

- Grygová, B. 2010. “Překlad odborného textu.” In Překlad a překládání, edited by D. Knittlová, B. Grygová, and J. Zehnalová, 203–212. Olomouc: Univerzita Palackého v Olomouci.

- Jack, R. C., and T. S. Rodgers. 2014. Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Janigová, S. 2023. “The Governing-Law Anchor in Legal Translation-A Homicide Case Study.” International Journal for the Semiotics of Law - Revue Internationale de Sémiotique Juridique 36 (4): 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11196-023-09992-z.

- Joseph, J. E. 1995. “Indeterminacy, Translation and the Law.” In Translation and the Law, edited by M. Morris, 13–36. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Kiraly, D. 2010. A Social Constructivist Approach to Translator Education. Manchester: St. Jerome Publishing.

- Klabal, O. 2018. “Shall We Teach Shall: An Attempt at a Systematic Step-By-Step Approach.” Studies in Logic, Grammar and Rhetoric 53 (66): 119–139. https://doi.org/10.2478/slgr-2018-0007.

- Klabal, O. 2020. “Developing Legal Translation Competence: A Step-By-Step Approach”. Unpublished diss., Palacký University Olomouc.

- Klabal, O. 2022. “Teaching Comparative Conceptual Analysis to Legal Translation Trainees.” In Proceedings of Translation and Interpreting Forum Olomouc. Olomouc Modern Language Series, 47–68. Olomouc: Palacký University.

- Kocbek, A. 2005. “Potential Problems of Using English As a Lingua Franca in Business Communication.” In Managing the Process of Globalisation in New and Upcoming EU Members: Proceedings of the 6th International Conference of the Faculty of Management Koper, 413–424. Koper: Faculty of Management.

- Lederer, M. 2003. Translation: The Interpretive Model. Manchester: St. Jerome.

- Lehto, L. 1992. “Pedagogical Aspects of Legal Translation.” Translatologica Pragensia, (4): 191–203.

- Lisowska, M. 2019. “Developing Translation Competence Through Situated Learning in the Community of Practice: The Case of Polish–English, English–Polish Undergraduate BA Level Legal Translation Class.” Społeczeństwo Edukacja: Język, (9): 7–31. https://doi.org/10.19251/sej/2019.9(1).

- Martínez Carrasco, R. 2019. “Competencias para la traducción jurídica: Modelos, enfoques y percepción del profesorado.” Quaderns de Filologia - Estudis Lingüístics 24 (24): 267–290. https://doi.org/10.7203/qf.24.16311.

- Matochová, V. 2018. “Kontrastivní analýza licenční smlouvy s koncovým uživatelem v angličtině a češtině z pohledu překladu.” Bachelor’s thesis, Palacký University Olomouc.

- Northcott, J., and G. Brown. 2006. “Legal Translator Training: Partnership Between Teachers of English for Legal Purposes and Legal Specialists.” English for Specific Purposes 25 (3): 358–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2005.08.003.

- Ortega Arjonilla, E. 1996. “El proceso de traducción de documentos jurídicos“. In Introducción a la traducción jurídica y jurada (inglés–español): Orientaciones metodológicas para la realización de traducciones juradas y de documentos, edited by P. S. G. Aguilar. 75–83. Granada: Comares.

- Phillips, A. 2003. Lawyers’ Language: How and Why Legal Language Is Different. London: Routledge.

- Piecychna, B. 2013. “Legal Translation Competence in the Light of Translational Hermeneutics.” Studies in Logic, Grammar and Rhetoric 34 (47): 141–159. https://doi.org/10.2478/slgr-2013-0027.

- Prieto Ramos, F. 2011. “Developing Legal Translation Competence: An Integrative Process-Oriented Approach.” Comparative Legilinguistics: International Journal for Legal Communication 5 (5): 7–21. https://doi.org/10.14746/cl.2011.5.01.

- Prieto Ramos, F. 2014. “Legal Translation Studies As Interdiscipline: Scope and Evolution.” Meta: Translators’ Journal 59 (2): 260–277. https://doi.org/10.7202/1027475ar.

- Puig, R. 2017. “Enseñanza y evaluación de la traducción jurídica.” Anales de la Facultad de Ciencias Jurídicas y Sociales 47 (14): 886–904.

- Šarčević, S. 1997. New Approach to Legal Translation. Hague: Kluwer Law International.

- Škrlantová, M. 2005. “Preklad právnych textov na národnej a nadnárodnej úrovni.” Preklad právnych textov na národnej a nadnárodnej úrovni, Edited by Jana Rakšányiová, 7–114. Bratislava: AnaPress.

- Smith, S. 1995. “Cultural Clash: Anglo-American Case Law and German Civil Law in Translation.” In Translation and the Law, edited by M. Morris, 179–200. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Soriano Barabino, G. 2016. Comparative Law for Legal Translators. Oxford: Peter Lang.

- Sparer, M. 1988. “L’enseignement de la traduction juridique: Une formation technique et universitaire.” Meta: Translators’ Journal 33 (2): 320–328. https://doi.org/10.7202/004205ar.

- Štědrá, D. 2017. “Notwithstanding a without prejudice to jsou antonyma, nikoli synonyma.” Právní prostor. https://www.pravniprostor.cz/clanky/ostatni-pravo/notwithstanding-a-without-prejudice-to-jsou-antonyma-nikoli-synonyma.

- Stolze, R. 2011. The Translator’s Approach – Introduction to Translational Hermeneutics; Theory and Examples from Practice. Berlin: Frank & Timme.

- Tomášek, M. 1991. “Právo – Interpretace a překlad.” In Acta Universitatis Carolinae: Philologica; Translatologica Pragensia 5, edited by M. Hrala, 147–154. Prague: Karolinum.

- Tomášek, M. 2003. Překlad v právní praxi. 2nd ed. Prague: Linde.

- Way, C. 2014. “Structuring a Legal Translation Course: A Framework for Decision-Making in Legal Translator Training.” In The Ashgate Handbook of Legal Translation, edited by K. K. S. Le Cheng and A. Wagner, 135–152. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Wiggers, W. J. H. 2011. Drafting Contracts: Techniques, Best Practice Rules and Recommendations Related to Contract Drafting. Hague: Wolters Kluwer.