Abstract

Deliberate practice (DP) is well established and widely accepted in expert performance research within a variety of fields. Recently, researchers have started to examine if the same training principles can be applied to psychotherapists. The aim of this study was to examine the impact on intrapersonal skills and the experiences of a six-week DP intervention on seven therapist trainees (n = 7). To do this, a single-case research design was used, combining weekly repeated measurements and pre- and post-intervention measurements as well as a qualitative study analyzed by inductive thematic analysis. The results from our measurements indicate mixed results, where three out of seven participants achieved a significant positive intervention effect and we can see that most participants change in the hypothesized direction on mindful attention (MAAS), experiential avoidance (MEAQ), emotional processing (EPI), and self-compassion (SCS). The participants described gains on increased self-awareness, more compassionate treatment of oneself, increased tolerance of unpleasant feelings as well as a sense of being able to use their own experiences to understand their relationship to other people. The intervention also gave the participants an ability to hold contrasting thoughts and emotions and provided an increased sense of hope for their own future development. The findings of our study should be interpreted in light of its pilot nature and the limited extent of our design. However, it indicates that it seems possible to achieve positive results on intrapersonal skills from a relatively short period of training.

Introduction

Neither professional experience (Goldberg et al., Citation2016b) nor level of education (Erekson et al., Citation2017) seems to be factors that has been proven to lead to better treatment outcomes. Adding to that, research suggests that no specific therapeutic methods have been able to consistently produce better results (Wampold & Imel, Citation2015). Still, there are notable differences in treatment outcomes between therapists (Baldwin & Imel, Citation2013). These results indicate that there may be specific therapeutic skills or characteristics that generate the differences in outcome. During the past decades, parts of the psychotherapy research community have been committed to find out what these might be (Wampold et al., Citation2017).

Individual differences in treatment outcomes

It has been shown in several meta-analyses that successful therapists have greater ability to establish a therapeutic relationship with patients (Horvath et al., Citation2011) and studies have found that a common feature of successful therapists is to possess good interpersonal relational skills (Anderson et al., Citation2009). For a therapist to be able to use interpersonal skills optimally, it has been suggested that it is important to deal with one’s own reactions (Gelso & Perez-Rojas, Citation2017), such as tolerating aggression, hostility and intense displays of dysphoric affect in the therapy room (Heinonen & Nissen-Lie, Citation2019). How therapists handle unpleasant reactions and their level of awareness depends on intrapersonal skills, and the importance of these skills has been highlighted in almost every therapeutic orientation over the years. Over a century ago, Freud (Citation1977) wrote about the therapist’s countertransference raised in the meeting with the patient and the importance of being able to recognize and master the countertransference. Since then, the importance of being aware of one’s own reactions as a therapist has been emphasized in orientations such as client-centered therapy (Rogers, Citation1961), gestalt therapy (Perls, Citation1975), emotion-focused therapy (Greenberg & Paivio, Citation1997), existential psychotherapy (Spinelli, Citation2007) and CBT (Bennett-Levy & Finlay-Jones, Citation2018).

Four intrapersonal skills

Mindfulness can be defined as “a moment-to-moment awareness of one’s experience without judgment” (Davis & Hayes, Citation2011, p. 198). Developing mindfulness has been shown to increase a number of skills important to psychotherapists, such as empathy, decreased stress and increased information processing speed (Davis & Hayes, Citation2011) and facilitate effective emotion regulation (Corcoran et al., Citation2010). Grepmair et al. (Citation2007) even found mindfulness training to improve treatment outcome.

Experiential avoidance is defined as “attempts to reduce distressing thoughts, feelings, or other negative subjective experiences even when doing so is ineffective and causes problems” (Scherr et al., Citation2015, p. 22). Waller (Citation2009) discussed how avoiding immediate patient distress to relieve the therapist’s own anxiety makes it harder to reach the long-term goals of therapy. A study by Scherr et al., (Citation2015) indicated that therapists with higher experiential avoidance tended to use less session time for exposure elements of OCD treatments.

Emotional processing means that a person is able to return to his normal routine behavior after being affected by disturbing emotional experiences, e.g. unpleasant intrusive thoughts, excessive fears, or behavioral disruption. When the symptoms are intense or fail to subside, the emotional processing is considered unsatisfactory (Rachman, Citation1980). In a qualitative study (Gross & Elliott, Citation2017) shows that therapists, meeting difficult patients, tend to over-identify, become overwhelmed, frustrated or take too much responsibility, and that this often leads to problems with their own emotional regulation. Therapists acting based on intense and unpleasant emotions, which tend to arise in therapy, have less desirable treatment outcomes (Hayes et al., Citation2011).

Self-compassion involves one’s sympathetic concerns and acceptance of one’s own shortcomings and has been suggested as a factor in effective psychotherapy (Gilbert, Citation2006). It has also been suggested as an important skill to cultivate in order to prevent fatigue and burnout among health care practitioners (Dorian & Killebrew, Citation2014).

Deliberate practice

To enhance these intrapersonal factors in therapists, and thereby improve treatment outcomes, some researchers have suggested that psychotherapists need to engage in deliberate practice (Miller et al., Citation2008; Rousmaniere, Citation2016; Rousmaniere, Citation2019; Rousmaniere et al., Citation2017). The term was introduced by Ericsson et al. (Citation1993) after they investigated what distinguishes expert violinists. The techniques of DP have been used in a wide variety of fields ranging from sports and music to medicine and is defined as “Individualized training activities especially designed by a coach or teacher to improve specific aspects of an individual’s performance through repetition and successive refinement.” (Ericsson & Lehmann, Citation1996, pp. 278–279). The theory suggests that the amount of time one is involved in repeated, specific and feedback provided training just over one’s present capacity, explains a person’s expertise in an area. Self-monitoring and continuous evaluation of one’s performance is also included in the concept of DP (Ericsson, Citation2004). Even though the psychotherapeutic skills targeted for improvement should be decided individually, DP for psychotherapists have so far mainly investigated the possibility of improving intrapersonal skills. The hypothesis in this fairly new area of DP for psychotherapists is that intrapersonal skills will impact the more visible and behavioral interpersonal skills and thereby improve therapy outcomes (Rousmaniere, Citation2019).

There are examples in the literature of several training methods that focus on the therapist’s internal reactions and experiences, including alliance-focused training (Safran et al., Citation2014), self-practice/self-reflection (SP/SR; Bennett-Levy & Finlay-Jones, Citation2018), and programs that focus on mindfulness, compassion and loving kindness (Boellinghaus et al., Citation2013), and they all have in common that they aim to improve useful therapeutic skills. While research suggests that DP is an important factor in expert performance (Miller et al., Citation2008; Tracey et al., Citation2015), it is not until recently that DP was applied to psychotherapy training (Rousmaniere, Citation2016). So far, the research on the amount of time therapists spend outside of treatment targeted at improving therapeutic skills have shown promising results (Chow et al., Citation2015; Goldberg et al., Citation2016a) and a few recent studies of DP interventions indicate preliminary positive results on facilitative interpersonal skills and immediacy (Anderson et al., Citation2019; Hill et al., Citation2019).

This study is intended to see what impact a short-term DP intervention has on psychologist trainees. Since the research field is in the beginning stages of development and our study is an early contribution to this field, we also want to get a more nuanced indication on how this training is experienced and how it can be further adjusted to maximize the effect. With this in mind, we formulated one hypothesis and one research question:

We hypothesize that deliberate practice enhances the intrapersonal skills of therapist trainees.

How is deliberate practice experienced in therapist trainees?

Method

Design

Quantitative method—single-case multiple-baseline design

A single-case multiple-baseline design was conducted and replicated across seven subjects. This design is well suited for unexplored phenomena and allows for large amounts of data within few subjects (Morley et al., Citation2018). It also has a built-in control function since each participant has a baseline phase with which their intervention phase is compared (Barlow et al., Citation2009). The participants started the baseline phase at the same time and were then randomized to different intervention starting points in a sequential fashion with one-week intervals. This made it possible to control for factors over and beyond the intervention, and thereby with greater certainty draw conclusions that possible changes can be explained by the intervention (Kazdin, Citation2011). Repeated measurements were made during a baseline phase (6–12 week) and during the six-week intervention phase. In addition to the repeated measurements, pre- and post-intervention measurements were conducted.

Qualitative method—inductive thematic analysis

The qualitative method is well suited for new unexplored areas and can support measurement-oriented research by introducing the participants experiential perspective and by representing complex phenomena. Due to the flexibility of inductive thematic analysis it is possible to get hold of a rich, detailed and complex account of the data (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006).

The setting

In Sweden, psychologist training is a five-year university program. The last two years of training involve providing psychological treatment at the university clinic and these patient sessions are being videotaped for pedagogical purposes. All participants of this study were simultaneously having supervision at the clinic as well as theoretical clinical courses.

Participants

Trainees

Students in the last year of a Swedish master’s program in psychology (n = 58) were offered to participate in the study. In this last year, students did clinical work under supervision. We made a purposeful selection (Hill, Citation2012) from the thirteen students that signed up, aiming for equal number of men and women, and both the included semesters. This resulted in a final sample of seven participants (four men and three women). The number of participants was decided due to the project’s time limit and the possibility of combining qualitative and quantitative data. The participants were between 26 and 34 years old, with a mean age of 30.9 (SD = 2.7) years. All completed the intervention. No form of compensation was offered for their participation.

Trainer

One of the authors, a white, male, American clinical psychologist specialized in DP ran all individual feedback sessions and has previous experience of conducting DP training.

Design

We employed an AB multiple-baseline single case experimental design. Single case design is suitable when investigating unexplored phenomena due to its clinical feasibility and flexibility (Barlow et al., Citation2009; Morley et al., Citation2018). The purpose of multiple baselines is to control for threats to the internal validity. If an observed change in close relation to the start of the experimental phase is repeated independent of length of baseline, a conclusion regarding the effect of the intervention is warranted (Morley et al., Citation2018). Each participant was followed before the training period had started (A: baseline phase; 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 or 12 wk, respectively) and during the training period (B: intervention phase; 6 wk). Each participant’s intervention phase was then compared with the baseline phase to detect change in the dependent variables. These were both repeated measurements that were made continuously during the baseline phase and the intervention phase, as well as pre- and post-intervention measures immediately before and after the intervention as secondary outcomes. Participants were interviewed after they had completed the intervention phase.

Intervention—six weeks of deliberate practice training

The participants engaged in six weekly individual training sessions led by an American clinical psychologist specialized in DP. The training sessions were conducted online in a secure video conference. In each session, the participants were guided through a DP exercise that lasted about 20–40 min and that followed a DP manual (Rousmaniere, Citation2019). Participants were asked to identify an intrapersonal challenge that they were experiencing in relation to a current client. For example, one participant had noted that she got disappointed and demoralized when trying to help a client who was not responding quickly to therapy. Another participant experienced strong anxiety in sessions with his client. A third participant had noticed that it was hard for her to accept clients who had differing political views.

With the help of the trainer, participants retrieved video stimuli related to the self-identified problem and that was personally evocative. For example, the disappointed and demoralized participant watched recordings of sessions with her own client not responding quickly to therapy. The participant with anxiety watched clips from the movie The Shining. The participant who had trouble accepting clients with differing political views watched speeches by politicians with whom she did not agree.

The trainer guided the participant through DP exercises that involved repetitive and individualized behavioral rehearsal with the evocative video stimuli to provide state-dependent learning. Exercises were crafted to target each participant’s individual skill threshold and aimed for high levels of sustained effort. Exercises typically involved identifying and labeling three internal processes/experiences: (a) thoughts/feelings, (b) bodily sensations, and (c) behavioral urges. All exercises included an emphasis on self-compassion and patience with oneself. At the end of each session, the participant was assigned homework to do before the next meeting (taking about 20 min to complete).

Interviews

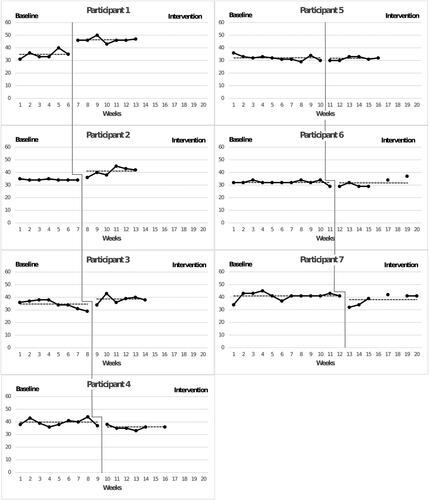

After completion of the intervention, semi-structured interviews were conducted with all participants covering experiences of the training and the training process. An example of a question was: “In what way has the training touched on areas that might be important for your future therapeutic work?”. All interviews were made face to face, except one who had to be made over telephone due to logistical reasons, with an average interview time of 60 min. All interviews were made with one interviewer, with the two first authors splitting up the interviews evenly among each other. The interviewer also brought the participants graph (see ) from the repeated measurements to get a comment on the transferability of the experience and the measurements.

Measures

Repeated measurements

Creating individualized, idiographic target measures is common in single case research (Morley et al., Citation2018). Following the criteria of Kazdin (Citation2011), six items were put together to measure intrapersonal skills. This collection of items, named the “Brief Inventory for Therapeutic Intrapersonal Skills (BITIS) was short enough to be used on a weekly basis as well as inclusive enough to cover the area of interest. The participants were asked to answer the BITIS once every week throughout the baseline and intervention phase, and they were asked to consider the statements in relation to their therapeutic intrapersonal skills during the past week. All six items were rated on a scale between 1 to 10 (1 = strongly disagree, 10 = strongly agree), resulting in a total score ranging between 6 and 60. Improvement is indicated by increased scores. Four of the questions were reversed, and the order of the items were randomized each week. shows an overview of the BITIS.

Table 1 Brief inventory for therapeutic intrapersonal skills (BITIS).

Pre- and post-intervention measurements

Immediately before and after the six-week intervention, four instruments were administered to the participants.

Mindful attention

The Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS; Brown & Ryan, Citation2003) is a 15-item, self-report questionnaire intended to measure the ability to be aware and to attend to the present moment. The scale has showed good convergent and discriminant validity, and good test-retest reliability with an intraclass correlation of .81 and a Cronbach’s alpha of .81 (Brown & Ryan, Citation2003).

Experiential avoidance

The Multidimensional Experiential Avoidance Questionnaire (MEAQ; Gámez et al., Citation2011) is a measure of 62 items divided into 6 subscales: behavioral avoidance, distress aversion, procrastination, distraction & suppression, repression & denial, and distress endurance. MEAQ has a Cronbach’s alpha of .95, has good construct validity, and can be discriminated from trait neuroticism (Rochefort et al., Citation2018).

Self-compassion

Participants’ degree of self-compassion was measured using the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS), which is a 26-item self-report measure divided into six factors: self-kindness, self-judgement, common humanity, isolation, mindfulness and over-identification. The SCS has shown good test-retest reliability (r=.93) and high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α=.92). Moreover, content validity as well as construct validity in terms of convergent and discriminant validity has been demonstrated (Neff, Citation2003).

Emotional processing

The Emotional Processing Inventory (EPI; Reid & Harper, Citation2008, as cited in Montagno et al., Citation2011) was used to measure participants’ self-reported degree of emotional processing. The scale consists of 26-items which are divided into three subscales: appraisal, expression and stability of emotions. The EPI has demonstrated good psychometric properties, both in terms of test-retest reliability (rs=.78 to .82) and regarding its internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha=.91; Reid & Harper, Citation2008, as cited in Montagno et al., Citation2011).

Quantitative data analysis

Repeated measurements

Visual inspection

To determine if the intervention had an effect, we compared the mean of the baseline phase to the mean of the intervention phase for each individual participant. Such a difference would suggest that there was an effect of the intervention for that participant.

However, we also needed to consider other aspects of the data that could contradict such a conclusion. In doing this, we studied the individual participants’ graphs (Kazdin, Citation2011). First, we determined if there was a pattern evident already in the baseline phase (a so called “trend”). Such a pattern would suggest that the mean difference between baseline and intervention phase is best attributable to other factors than the intervention. Second, we compared the last measurement point of the baseline phase to the first measurement point of the intervention phase (a so called “change of level”). If they were close, that would also suggest that the mean difference between baseline and intervention phase is best attributable to other factors than the intervention. Third, we investigated when (if ever) the effect of the intervention appeared in the intervention phase (the so called “latency”). If the change in the intervention phase was late, that would also suggest that the mean difference between baseline and intervention phase is best attributable to other factors than the intervention.

To decrease subjectivity and bias, visual inspection was first carried out by the two main authors, followed by two independent raters with previous experience of visual analysis. In addition to visual inspection, we also used two statistical methods developed to analyze data from single case design: Nonoverlap of All Pairs (NAP) and Tau-U. Calculations for both these methods were done using a free online calculator available online at http://www.singlecaseresearch.org (Vannest et al., Citation2016).

Nonoverlap of All Pairs (NAP)

First, we used the Non-Overlap of All Pairs (NAP) (Parker & Vannest, Citation2009). For each data point in the intervention phase, the researchers determined if it was larger than the corresponding data point in the baseline phase (i.e. nonoverlapping). An index was calculated by dividing the number of nonoverlapping pairs with the total number of pairs. This index was used as an effect size. Parker and Vannest (Citation2009) suggested that NAP between 0–.65 equals a weak effect, 66–.92 equals a medium effect, and.93–1.0 equals a strong effect.

Tau-U

Trends in the baseline phase can inflate the NAP (Kazdin, Citation2011; Kratochwill & Levin, Citation2010). To adjust for trends in the baseline phase, the Tau-U effect size was used (for calculations, see Parker et al., Citation2011). Vannest and Ninci (Citation2015) suggested that Tau-U of 0–.20 equals a small effect, .20–.60 equals a moderate effect, .60–.80 equals a large effect, and .80–1.0 equals a large to very large effect depending on the context.

Pre- and post-intervention measurements

Reliable change index (RCI)

To investigate whether the trainees had any reliable difference on our pre- and post-measurements, we calculated RCI (Jacobson & Truax, Citation1991) by using the standard deviation (SD) and test-retest reliability from previous research (Klatt et al., Citation2009; Irons & Heriot-Maitland, Citation2021). This was possible to do on MAAS and SCS.

Percentage of change

On MEAQ and EPI, the percentage of change between pre- and post-measurement was calculated by dividing the post-measurements’ score with the pre-measurements’ score. This was done when no test-retest reliability (MEAQ) or standard deviation (EPI) was available. Since our pre- and post-measurements were relatively extensive, they helped us to observe general patterns and suggest hypotheses to be tested in future research. This type of analysis cannot rule out many of the threats to validity and its ability to draw causal conclusions is weak (Morley et al., Citation2018).

Qualitative data analysis

Inductive thematic analysis

The interviews were first transcribed into text and as second step all parts of the text were marked and divided into 1241 quotations using the software ATLAS.ti (Citation2019). Second, all the quotations were examined anew to assign them to codes along with other quotations on the same topic. These groups of codes were then given names a final list of 99. These were coded in a semantic fashion (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006), meaning that no deeper abstract interpretation of the material felt necessary to answer our research question. Instead, the themes were coded in a way that was close to the original data. Third, these codes were grouped 15 subthemes. Finally, those subthemes were categorized into four main themes, capturing the essence of our findings. The themes were then defined and given a title. A member checking was made with the participants where they were given a chance to comment on the analysis. No corrections were made after this meeting.

Ethical considerations

This study has been approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority in Uppsala [dnr 2019-00543]. There were no affiliations between researchers and participants. The authors declare no conflicts of interest with respect to their authorship or the publication of this article.

Results

Quantitative measures—changes in intrapersonal skills

Repeated measurements

The weekly report (BITIS; see ) was rated on a scale between 1 and 10 (1 = strongly disagree and 10 = strongly agree), and a total score ranging between 6 and 60. shows the results from these measurements. For our first two participants we can see a change in mean level in the hypothesized direction between the baseline phase and intervention phase, which is confirmed by our NAP scores, indicating a strong effect size for both (see ). Visual inspection does not reveal any great differences in mean value for participant 3. However, a change in level can be observed for participant 3, which is also true for participant 1.

Table 2 Results from repeated measures on psychological capacity.

Participant 4 shows variability in the baseline but no trend. There is a decrease in mean level, which indicates an effect opposite that of the hypothesized intervention direction. This is also confirmed by NAP scores indicating a medium negative effect.

For participant 5, the baseline has a slight downward slope, which according to Tau is significant. After correcting for baseline trend, the result is significant and indicates a positive intervention effect. Participant 6 shows a stable baseline without trend. We see no difference in mean value for participant 6 but the latency effect suggests a possible delayed incremental increase. Participant 7 starts off with some variability but stabilizes by the end of the baseline. No mean level change is observed, but we see a decreased change in level after the intervention sets in. Participants 6 and 7 show no significant intervention effect.

In summary, three participants show a positive intervention effect, one participant show a negative intervention effect, and for three participants we cannot observe a change between baseline and intervention phase in mean difference. The NAP and Tau scores are shown in .

Pre- and post-intervention measurements

shows the pre- and post-intervention scores. Six out of seven participants showed an increase in mindful attention from pre-intervention to post-intervention. Participant 1 is the only one showing a decrease in mindful attention. Moreover, six out of seven participants showed a decrease in experiential avoidance from pre-intervention to post-intervention, which is in line with the hypothesized direction. Participant 5 is the only participant showing an increase in experiential avoidance at post-intervention.

Table 3 Perceived mindfulness (MAAS), experiential avoidance (MEAQ), emotional processing (EPI) and self-compassion (SCS) at pre- and postintervention.

The results on emotional processing suggest no changes. Participants 1 and 5 reports a decrease in emotional processing and participants 3, 4, 6 and 7 reports an increase, while no change is observed for participant 2. Regarding self-compassion, participants 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 indicate increases from pre- to post-intervention, and the other two have a decreased score.

Overall, the results are mixed. A reversed effect is observed on some measures for three participants. However, with these exceptions, the intervention seems to have had a positive effect on the desired outcome dimensions.

Experiences of deliberate practice training—Four main themes

Main theme 1—Prerequisites—promoting and aggravating factors

The analysis indicated several factors that can influence the result and experience of DP training. The threshold for getting started with DP was perceived as low. The training method was experienced as comprehensible and it was easy to construct exercises. The following quote captures the simplicity of the training: You’d be able do this with quite low level of mental capacity […] It felt to simple, It was like, should I just sit down and watch clips? […] But that was exactly the strength of it. This simplicity.

The participants highlighted the importance of understanding the principles and underlying structure of DP to enhance motivation of the training, one participant described those as intuitive. Another motivating factor was to find exercises that suit the needs of the participant and that the training was in sync with one’s personal goals and aspirations, both privately and professionally. To customize the training based on personal preferences, area of focus and level of tolerance was challenging but considered as one of the most fruitful aspects. The flexibility was a positive element. One participant stated: The more I started to understand about it and the more I tried to see that now something’s happening, the more interested I became.

One important aspect was to focus on self-care within the training. The participants mentioned the importance of being able to handle self-criticism or self-doubt, regardless of whether they existed earlier or if they arose in connection with the training. The training resulted in a development towards becoming more forgiving to themselves. The participants stated that even though the self-critical thoughts have not disappeared, they do not let themselves be affected by them as much as before.

One challenge was the search for the right stimulus on sufficient emotionally level. One participant stated: While the first was more dryland swimming, that it was like 'yeah, this is good’ a bit more neutral ground you know, but watching your own patient gets more charged, or it was for me anyway. The participants stated that it initially felt weird to watch video clips and notice your own feelings or to talk in front of a screen. The following quote is an example of the uncertainty about how to carry out the training: It’s a bit diffuse to sit down and watch a film and notice things within you. If you’ve never done it before it’s quite difficult to know exactly what to do. It turned out that the participants felt somewhat confused and doubted their own reactions during the exercises: I thought it was difficult, it felt like you got very self-conscious but on the wrong stuff. Instead of sensing how it felt in the body, it was more like 'Am I really feeling correctly what I feel?'.

Main theme 2—increased understanding as a basis for change

The participants described an increased sense of control when experiencing strong feelings, and that they got better equipped to down-regulate themselves. They expressed that DP has paved the way for a new way of thinking about their experiences in the therapy room and increased therapeutic presence and awareness. The first step in this process has to do with the capacity to observe one’s own thoughts, feelings, physical reactions and urges and to be able to stay present in the moment. The participants mentioned progress within this area: …from the first time to the last time as I could get more out of that video and notice what I feel in relation to the patient in another way. My progress has felt pretty distinct. The participants also talked about the experience of being able to observe one’s own defensive reactions while they happened and the importance of being able to notice not only thoughts and feelings, but also the absence of an expected experience, such as a lack of empathy.

Second, after observing their reactions, the participants faced the challenge of tolerating these experiences and thus became more tolerant of self-criticism. These challenges could be to deal with emotions that arise when a patient is dissatisfied with the therapy, or to tolerate emotions raised when a patient targets aggression against oneself as a therapist. DP was compared with exposure training and over time developing a tolerance to unpleasant feelings and no need to avoid certain situations that evoke those reactions and being able to witness emotions without changing them and accepting several thoughts and feelings at the same time.

Third, with this basis of being able to notice one’s own experiences, tolerating and accepting whatever comes up, participants mentioned the new experience of being able to use this knowledge as a basis for making more active and informed choices in the therapy room. The participants also mentioned an increased ability to be able to separate their own feelings from those of the patient. Acting on the countertransference could be managed more easily. One participant mentioned being calmer, another was able to time interventions better, and a third mentioned being able to focus more on the patient. The participants also talked about an increased sense of being able to use themselves as a useful tool, both as a holding and containing agent and use their own felling as an important source of information to understand the patient.

Main theme 3—gains beyond the therapy room

The skills practiced during the intervention could also be applied in the private lives of the participants. For example, they considered themselves better at noticing their own and other people’s feelings Participants describe personal insights because of the training. For example, realizing that it was more difficult than previously experienced to identify feelings or accepting that being able to control one’s emotions is an unattainable goal to strive for. The participants described the feedback sessions as therapeutic. They explained that the training had contributed to an increased awareness and a more realistic self-perception. One participant commented a lack of self-insight and an overestimation of their ability in the following way: So, I think that might be an explanation to why my numbers dropped. You get a bit of insight into, well I’ve probably had these shortcomings all along, but maybe I haven’t been fully conscious of them.

Main theme 4—Looking ahead

Even though the participants have generated positive experiences from these weeks, the participants mentioned the need for further training. As one participant put it: These are not abilities that like ‘now I know this’, but it’s something that takes time to develop. Development takes time. The participants had some faith in long-term effects of the training but stressed the need for further and continuous training before they could reliably evaluate the impact of the training. They described the importance of the weekly feedback sessions for keeping focus and staying on track and being a valuable way to keep the training level within the helpful limits. Important characteristics for the DP trainer was an ability to increase reflection, give support, normalize doubts, show genuine interest, serve a role-modeling function and having personal experience of the benefits and difficulties of the exercises.

The participants mentioned the difficulties of handling the personal responsibility of maintaining a regular training routine. The difficulty of self-discipline was one part of the potential problem, as well as the trouble of continuing to evolve the practice as the intrapersonal skill level increases. The participants seemed to enjoy the collaborative elements of the practice, and for some participants isolated training without support by a mentor or a community was a difficult undertaking.

However, the empowering feeling of being in control of one’s own development and having the knowledge of how to expand one’s skills and capacity further. The knowledge of how to design custom made exercises seems to have been important to move forward. Being exposed to one’s own difficulties within a therapeutic framework seemed as important as being given the tools of how to take it further and increased a sense of hope about the ability to actually improve on these difficult domains within psychotherapy: Well, I think that it’s given me some hope that it’s actually possible to practice these things. That I can put myself in a situation that at least reminds me of what might happen in real life.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to examine the effects and experiences of a short DP intervention for therapist trainees. The pre- and post-intervention measurements show a pattern suggesting an intervention effect, where most participants moved in the expected direction on all four instruments. However, the results from the repeated measurements (BITIS) were mixed, where only three out of seven participants showed significant improvement. In addition, in the interviews, participants described important gains from the training that not only influenced clinical practice, but also their personal lives. The results provide clues to effective DP interventions, such as individualizing the training, collaborating with the DP trainer and having an understanding of the underlying aspects of the intervention.

Discussion of the results

Quantitative results

Of the pre- and post-intervention measurements, the most positive results were obtained from the participants’ perceived mindfulness (MAAS) and experiential avoidance (MEAQ). This may indicate that these two constructs are the central components of the skills possible to develop with DP training. Some participants attained improvements on BITIS but not on the pre- and post-intervention measurements and vice versa. This could possibly be explained by the fact that some participants had a broad effect of the training and thereby a tendency to score higher on the pre- and post-intervention measurements. Others may have obtained a more isolated effect on specific therapeutic skills and thus had a tendency to score higher on BITIS, an instrument asking specifically for gains in the therapy room.

Qualitative results

One similarity between the experiences of SP/SR, as presented in McGillivray et al. (Citation2015), and our participants’ descriptions of DP was a progression towards increased self-awareness and that the interventions appear to lead to a development towards interpersonal skills. The experiences of SP/SR and DP also differ in several ways. While participants who completed SP/SR reported an increased understanding of therapeutic methods and being better equipped with specific therapeutic techniques, our participants described a process that has more to do with using themselves as a tool in the therapy room. Our participants emphasized that interpersonal skills were the result of having focused on their own intrapersonal skills.

Individualizing the training made it both enjoyable and effective. The importance of personalization based on specific needs and current skill level has previously been described to be important in psychotherapy supervision (Goodyear & Bernard, Citation1998). The intrapersonal focus of the exercises transferred into the participants interpersonal abilities, both professionally and in their private lives, manifested as an increased sense of being able to use their own internal experiences to understand the relationship to other people. This connection has been found in a previous study (Safran et al., Citation2014) where therapists engaging in alliance-focused training (AFT) reported a greater understanding of how to use themselves to pick up on inner signals in the relationship to patients. A good collaboration with the supervisor was seen as key, and this has been highlighted in AFT (Eubanks et al., Citation2019) and in a study on DP (Hill et al., Citation2019).

An important topic from our interviews has been the need for self-care while engaging in DP. This both had to do with the need for a more compassionate treatment of oneself in order to maintain the energy of the psychologically demanding clinical work itself (Wise & Barnett, Citation2016), but also to stay motivated enough to keep up the training. Identifying this need may be an important step in order to make DP an effective individualized long-term project. The results from our pre- and post-intervention measurements on self-compassion indicate a positive intervention effect. Nissen‐Lie et al. (Citation2017) have highlighted how the balance of professional self-doubt and self-affiliation is related to patient outcomes, and this could prove important for DP as well, where the shortcomings of the therapist are put on full display.

Inconsistencies among data

When we look at the results of the repeated measurements, we see three participants without an intervention effect and one participant with a deterioration in intrapersonal skills, which seems to deviate from the participants’ reported experiences in the interviews of the intervention as successful. This may be understood through the participants’ descriptions of an increased self-awareness and a more realistic view of their own capabilities as a result of the intervention. The difficulty experienced by our participants of correctly estimating one’s own capacity has been highlighted in many studies and is often referred to as the Dunning-Kruger effect (Kruger & Dunning, Citation1999). This effect partly has to do with the fact that individuals with poor ability tend to overestimate themselves, a tendency that mainly occurs in areas when the ability that the person intends to assess is the same as the ability required to make the assessment itself.

We have received somewhat mixed results from our data. Generally, the data that generated the most promising signs of an intervention effect was the interviews. This may have to do with the difficulty of accurately self-assessing mentioned above or by a wish to please the researchers and DP trainer during interviews. Another possibility is that the questionnaires pick up on actual change more accurately than the interviews and better reflect the true impact of the intervention.

Methodological considerations

In interpreting the results of the repeated measurements, it is important to consider how an intervention is supposed to work (Kazdin, Citation2011). Even though a rapid development is possible in DP, early progress usually plateaus (Ericson, 2004) and extensive training is required to keep developing. Thus, the brevity of this intervention stands in contrast with the long-term nature that characterizes DP in the literature (Ericsson & Lehmann, Citation1996), and the results should be interpreted considering this fact. The intervention deviates from how DP is supposed to work with regard to the amount of time that is expected to be invested (Ericsson et al., Citation1993), whereas each of our participants in total spent about five hours of training during a period of six weeks, including feedback sessions. The qualitative aspects of our study were not affected by this time constraint, but the measured effects should be interpreted with some caution based on these facts. The intervention has consisted of both solitary practice and feedback sessions. The feedback sessions with the DP trainer has been an important part of the training, and even if we aimed to measure the effects of DP itself, we cannot rule out the possibility that the positive results can be attributed to a trainer-effect.

One potential limitation threatening the internal validity, is that the participants in parallel with the intervention had theoretical clinical courses and underwent clinical training with supervision at the university clinic. Thus, an increase in intrapersonal skills could be explained by these factors and not by the intervention itself. We protect ourselves against this threat by using a multiple baseline design which makes it possible to control for factors over and beyond the intervention. Also, the participants were recruited by personal interest, which may impact the motivation of the students. It could have been helpful to match the qualitative answers to each specific participant to better be able to compare their perceived effect to the measurements and to get a better sense of what worked, what did not and why some people improved more than others. However, we made the decision to use a group level analysis on our qualitative data for the ethical reason that it otherwise would be too difficult to anonymize the results. Another limitation is the lack of measurements of interpersonal abilities and treatment outcomes. However, this was decided to lay beyond the scope of this pilot study. Since we only used seven participants, the generalizability of our study is low.

Implications and future research

This study has been an attempt to investigate the effects of a short-term DP intervention for therapist trainees. Although DP is a well-studied construct, its application for psychotherapy is still in the beginning stages. Further investigation is needed, and if DP is proven to yield good results in the long-term, an implementation of the training methods should be considered for therapist training institutions as well as for supervision. This would mean an increased focus on individualized experience-based learning as a complement to general theoretical knowledge.

Future research should attempt to find accurate ways of measuring progress within the areas that DP aim to improve. It would be helpful with a more detailed case by case analysis to understand why some therapists seem to benefit from the training while others do not. That would require a deeper case by case analysis, which leaves us with only speculations. One possible answer could be the motivation of the participants. Another could be that DP needs even further individualization to be helpful, such as focusing on other skills that inner emotional obstacles (communication skills, building expectations, noticing subtle changes in the patient etc.) Being able to measure therapeutic outcome for therapists engaging in DP would of course be optimal but involves difficulties regarding the amount of time needed and how to control for factors over and beyond the training. It would also be interesting to see how an intervention similar to ours would impact experienced therapists in comparison with therapist trainees. Following a larger sample of therapists over time, while collecting data on treatment outcomes and DP routines would be a major contribution to the literature, especially compared to standard psychotherapy training. As we have already mentioned, this kind of training requires commitment over time and our contribution should be seen as a starting point in what to expect and have in mind when using DP as a way of becoming a better therapist.

Conclusions

This study is a contribution to the expanding field of how DP can be used to help psychotherapists develop. The intervention provided some of the participants with increased intrapersonal skills, indicated by both repeated measurements and pre- and post-intervention measurements. Participants experienced gains on mindful attention, experiential avoidance, emotional processing and self-compassion. However, the findings are not consistent in all participants and needs replication and long-term follow-up. The results of our investigation indicate reasons to be optimistic about the potential of this form of training. However, the results have to be interpreted with caution, due to the pilot nature and the limited extent of our research design. We hope that our study launches further exploration.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Anderson, T., Ogles, B. M., Patterson, C. L., Lambert, M. J., & Vermeersch, D. A. (2009). Therapist effects: Facilitative interpersonal skills as a predictor of therapist success. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65(7), 755–768. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20583

- Anderson, T., Perlman, M. R., McCarrick, S. M., & McClintock, A. S. (2019). Modeling therapist responses with structured practice enhances facilitative interpersonal skills. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 76(4), 659–675. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22911

- ATLAS.ti. (2019). ATLAS.ti 8 [Computer software]. Retrieved from: http://atlasti.com

- Baldwin, S. A., & Imel, Z. E. (2013). Therapist variables in psychotherapy research. In M. J. Lambert (ed.), Bergin and Garfield’s Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change (6th ed.). Wiley.

- Barlow, D., Nock, M., & Hersen, M. (2009). Single case experimental designs: Strategies for studying behavior for change (3rd ed.). Pearson/Allyn and Bacon.

- Bennett-Levy, J., & Finlay-Jones, A. (2018). The role of personal practice in therapist skill development: A model to guide therapists, educators, supervisors and researchers. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 47(3), 185–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2018.1434678

- Boellinghaus, I., Jones, F. W., & Hutton, J. (2013). Cultivating self-care and compassion in psychological therapists in training: The experience of practicing loving-kindness meditation. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 7(4), 267–277. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033092

- Braun, V., &Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822

- Chow, D. L., Miller, S. D., Seidel, J. A., Kane, R. T., Thornton, J. A., & Andrews, W. P. (2015). The role of deliberate practice in the development of highly effective psychotherapists. Psychotherapy, 52(3), 337–345. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000015

- Corcoran, K. M., Farb, N., Anderson, A., & Segal, Z. V. (2010). Mindfulness and emotion regulation: Outcomes and possible mediating mechanisms. In A. M. Kring & D. M. Sloan (Eds.), Emotion regulation and psychopathology: A transdiagnostic approach to etiology and treatment (pp. 339–355). Guilford Press.

- Davis, D. M., & Hayes, J. A. (2011). What are the benefits of mindfulness? A practice review of psychotherapy-related research. Psychotherapy (Chicago, Ill), 48(2), 198–208. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022062

- Dorian, M., & Killebrew, J. E. (2014). A study of mindfulness and self-care: A path to self-compassion for female therapists in training. Women & Therapy, 37(1–2), 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/02703149.2014.850345

- Erekson, D. M., Janis, R., Bailey, R. J., Cattani, K., & Pedersen, T. R. (2017). A longitudinal investigation of the impact of psychotherapist training: Does training improve client outcomes? Journal of Counseling Psychology, 64(5), 514–524. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000252

- Ericsson, K. A. (2004). Deliberate practice and the acquisition and maintenance of expert performance in medicine and related domains. Academic Medicine, 79, S70–S81. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200410001-00022

- Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R. T., & Tesch-Römer, C. (1993). The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychological Review, 100(3), 363–406. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.100.3.363

- Ericsson, K. A., & Lehmann, A. C. (1996). Expert and exceptional performance: Evidence of maximal adaptation to task constraints. Annual Review of Psychology, 47(1), 273–305. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.47.1.273

- Eubanks, C. F., Muran, J. C., Dreher, D., Sergi, J., Silberstein, E., & Wasserman, M. (2019). Trainees’ experiences in alliance-focused training: The risks and rewards of learning to negotiate ruptures. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 36(2), 122–131. https://doi.org/10.1037/pap0000233

- Freud, S. (1977). Den psykoanalytiska terapins framtidsutsikter [The future prospects of psychoanalytic therapy]. Prisma. (Original work published 1910).

- Gámez, W., Chmielewski, M., Kotov, R., Ruggero, C., & Watson, D. (2011). Development of a measure of experiential avoidance: The multidimensional experiential avoidance questionnaire. Psychological Assessment, 23(3), 692–713. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023242.supp

- Gelso, C. J., & Perez-Rojas, A. E. (2017). Inner experience and the good therapist. In L. G. Castonguay & C. E. Hill (Eds.), How and why are some therapists better than others?: Understanding therapist effects (pp. 101–115). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000034-007

- Gilbert, P. (2006). Compassion: Conceptualizations, research and use in psychotherapy. Routledge.

- Goldberg, S. B., Babins-Wagner, R., Rousmaniere, T., Berzins, S., Hoyt, W. T., Whipple, J. L., Miller, S. D., & Wampold, B. E. (2016a). Creating a climate for therapist improvement: A case study of an agency focused on outcomes and deliberate practice. Psychotherapy (Chicago, Ill.), 53(3), 367–375. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000060

- Goldberg, S. B., Rousmaniere, T., Miller, S. D., Whipple, J., Nielsen, S. L., Hoyt, W. T., & Wampold, B. E. (2016b). Do psychotherapists improve with time and experience? A longitudinal analysis of outcomes in a clinical setting. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 63(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000131

- Goodyear, R. K., & Bernard, J. M. (1998). Clinical supervision: Lessons from the literature. Counselor Education and Supervision, 38(1), 6–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.1998.tb00553.x

- Greenberg, L. S., & Paivio, S. C. (1997). Working with emotions in psychotherapy. Guilford Press.

- Grepmair, L., Mitterlehner, F., Loew, T., Bachler, E., Rother, W., & Nickel, M. (2007). Promoting mindfulness in psychotherapists in training influences the treatment results of their patients: A randomized, double-blind, controlled study. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 76(6), 332–338. https://doi.org/10.1159/000107560

- Gross, B., & Elliott, R. (2017). Therapist momentary experiences of disconnection with clients. Person-Centered & Experiential Psychotherapies, 16(4), 351–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/14779757.2017.1386588

- Hayes, J. A., Gelso, C. J., & Hummel, A. M. (2011). Managing countertransference. Psychotherapy (Chicago, Ill.), 48(1), 88–97. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022182

- Heinonen, E., & Nissen-Lie, H. A. (2019). The professional and personal characteristics of effective psychotherapists: A systematic review. Psychotherapy Research: Journal of the Society for Psychotherapy Research, 30(4), 417–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2019.1620366

- Hill, C. E. (2012). Consensual qualitative research: A practical resource for investigating social science phenomena. American Psychological Association.

- Hill, C. E., Kivlighan, D. M., III, Rousmaniere, T., Kivlighan, D. M., Jr., Gerstenblith, J. A., & Hillman, J. W. (2019). Deliberate practice for the skill of immediacy: A multiple case study of doctoral student therapists and clients. Psychotherapy (Chicago, Ill.), 57(4), 587–597. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000247

- Horvath, A. O., Del Re, A. C., Flückiger, C., & Symonds, D. (2011). Alliance in individual psychotherapy. Psychotherapy (Chicago, Ill.), 48(1), 9–16. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022186

- Irons, C., & Heriot-Maitland, C. (2021). Compassionate mind training: An 8-week group for the general public. Psychology and Psychotherapy, 94(3), 443–463. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12320

- Jacobson, N. S., & Truax, P. (1991). Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 59(1), 12–19. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-006x.59.1.12

- Kazdin, A. (2011). Single-case research designs: Methods for clinical and applied settings (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Klatt, M. D., Buckworth, J., & Malarkey, W. B. (2009). Effects of low-dose mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR-ld) on working adults. Health Education & Behavior: The Official Publication of the Society for Public Health Education, 36(3), 601–614. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198108317627

- Kratochwill, T. R., & Levin, J. R. (2010). Enhancing the scientific credibility of single-case intervention research: Randomization to the rescue. Psychological Methods, 15(2), 124–144. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017736

- Kruger, J., & Dunning, D. (1999). Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1121–1134. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.77.6.1121

- McGillivray, J., Gurtman, C., Boganin, C., & Sheen, J. (2015). Self‐practice and self‐reflection in training of psychological interventions and therapist skills development: A qualitative meta‐synthesis review. Australian Psychologist, 50(6), 434–444. https://doi.org/10.1111/ap.12158

- Miller, S. D., Duncan, B., & Hubble, M. (2008). Supershrinks: What is the secret of their success? Psychotherapy in Australia, 14(4), 14–22.

- Montagno, M., Svatovic, M., & Levenson, H. (2011). Short‐term and long‐term effects of training in emotionally focused couple therapy: Professional and personal aspects. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 37(4), 380–392. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2011.00250.x

- Morley, S., Materson, C., & Main, C. (2018). Single case methods in clinical psychology: A practical guide. Routledge.

- Neff, K. D. (2003). The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity, 2(3), 223–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309027

- Nissen‐Lie, H. A., Rønnestad, M. H., Høglend, P. A., Havik, O. E., Solbakken, O. A., Stiles, T. C., & Monsen, J. T. (2017). Love yourself as a person, doubt yourself as a therapist? Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 24(1), 48–60. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1977

- Parker, R. I.,Vannest, K. J.,Davis, J. L., &Sauber, S. B. (2011). Combining nonoverlap and trend for single-case research: Tau-U. Behavior Therapy, 42(2), 284–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2010.08.006 21496513

- Parker, R. I., & Vannest, K. (2009). An improved effect size for single-case research: Nonoverlap of all pairs. Behavior Therapy, 40(4), 357–367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2008.10.006

- Perls, F. (1975). Det gestaltterapeutiska arbetssättet. Ögonvittne till psykoterapi [The Gestalt Apporach & Eye Witness to Therapy]. Wahlström & Widstrand.

- Rachman, S. (1980). Emotional processing. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 18(1), 51–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(80)90069-8

- Reid, R., &Harper, J. (2008). The Emotional Processing Inventory. Unpublished Manuscript.

- Rochefort, C., Baldwin, A. S., & Chmielewski, M. (2018). Experiential avoidance: An examination of the construct validity of the AAQ-II and MEAQ. Behavior Therapy, 49(3), 435–449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2017.08.008

- Rogers, C. (1961). On Becoming a Person. Constable.

- Rousmaniere, T. G. (2016). Deliberate practice for psychotherapists: A guide to improving clinical effectiveness. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Rousmaniere, T. G. (2019). Mastering the inner skills of psychotherapy: A deliberate practice manual. Gold Lantern Books.

- Rousmaniere, T. G., Goodyear, R. K., Miller, S. D., & Wampold, B. E. (2017). The cycle of excellence: Using deliberate practice to improve supervision and training. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Safran, J., Muran, J. C., Demaria, A., Boutwell, C., Eubanks-Carter, C., & Winston, A. (2014). Investigating the impact of alliance-focused training on interpersonal process and therapists’ capacity for experiential reflection. Psychotherapy Research: Journal of the Society for Psychotherapy Research, 24(3), 269–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2013.874054

- Scherr, S. R., Herbert, J. D., & Forman, E. M. (2015). The role of therapist experiential avoidance in predicting therapist preference for exposure treatment for OCD. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 4(1), 21–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2014.12.002

- Spinelli, E. (2007). Practicing existential psychotherapy: The relational world. SAGE.

- Tracey, T. J. G., Wampold, B. E., Goodyear, R. K., & Lichtenberg, J. W. (2015). Improving expertise in psychotherapy. Psychotherapy Bulletin, 50(1), 7–13.

- Vannest, K. J., &Ninci, J. (2015). Evaluating Intervention Effects in Single‐Case Research Designs. Journal of Counseling & Development, 93(4), 403–411. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12038

- Vannest, K. J., Parker, R. I., Gonen, O., & Adiguzel, T. (2016). Single Case Research: Web based calculators for SCR analysis. (Version 2.0) [Web-based application]. Texas A&M University. Retrieved Sunday 20th November 2022. Available from singlecaseresearch.org

- Waller, G. (2009). Evidence-based treatment and therapist drift. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47(2), 119–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2008.10.018

- Wampold, B. E., Baldwin, S. A., Holtforth, M. G., & Imel, Z. E. (2017). What characterizes effective therapists? In L. G. Castonguay & C. E. Hill (Eds.), How and why are some therapists better than others?: Understanding therapist effects (pp. 37–53). American Psychological Association.

- Wampold, B. E., & Imel, Z. E. (2015). The great psychotherapy debate: The evidence for what makes psychotherapy work (2nd ed.). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Wise, E. H., & Barnett, J. E. (2016). Self-care for psychologists. In J. C. Norcross, G. R. VandenBos, D. K. Freedheim, & L. F. Campbell (Eds.), APA handbook of clinical psychology: Education and profession (Vol. 5, pp. 209–222). American Psychological Association.