?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Purpose

To translate and culturally adapt the Swedish version of the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire into Dutch and to examine the validity and reliability aspects of the Dutch version.

Methods

The ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire was translated and culturally adapted to the Dutch situation. A total of 58 participants filled in the first questionnaire at baseline and 51 participants filled in the second questionnaire sent two weeks later. The data of the participants who filled in the first questionnaire was used to determine internal consistency, structural validity and concurrent validity. The data of the participants who filled in both questionnaires was used to determine test-retest reliability.

Results

The internal consistency was good with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.83. The structural validity was satisfactory with a Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test of 0.75 and a significance of p < .001 for the Bartlett’s test. Four factors were extracted using principal component analysis (PCA) with varimax rotation with an explained total variance of 70.8%. Spearman’s rho for concurrent validity was 0.68 (p < .001). The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for test-retest was 0.80 (p < .001) for the total score.

Conclusions

The Dutch version of the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire showed good internal consistency, satisfactory structural validity, strong concurrent validity (with mixed item representation results) and strong reliability.

Introduction

In March 2020, only 3.3% of the Dutch working population was unemployed [Citation1]. This means that over nine million people were in paid employment. The work environment can affect physical and mental health, work performance and absenteeism [Citation2,Citation3]. Almost a quarter of the Dutch employees who reported absenteeism (absent from work due to illness/disability) indicated that the reason for their absence was partly or even mainly related to working conditions [Citation4–6]. This is in line with research which shows that individuals working in demanding or stressful environments are more likely to experience negative mental and physical health symptoms [Citation7]. For example high job demands and bullying can lead to poorer health of employees [Citation8,Citation9].

Many patients with work-related complaints are seen in primary care, including physiotherapy practices [Citation10]. A negative perception of the work environment is a prognostic factor for delayed recovery [Citation11]. Factors, such as high demands, low rewards and the absence of social support are associated with stress for employees [Citation12,Citation13]. Research has shown that stress due to the work environment can delay the recovery time for any pathological complaint or injury [Citation14]. Moreover, the treatment effectiveness of physiotherapy is partly dependent on the social situation of the patient, including their working conditions and experienced level of stress [Citation15]. Therefore, it is important to screen for work-related psychosocial risk factors.

One way to specifically focus on work-related conditions in physiotherapy treatment is by determining the presence of blue flags. Blue flags are defined as the patient’s perception of occupational factors, including work-related psychosocial factors, that can lead to a higher level of stress and disability [Citation10,Citation16]. Examples of these conditions are poor relationships with supervisors/colleagues, job discontent and high demands [Citation12,Citation16]. The presence of blue flags is an indicator of a stressful, unsupportive and excessively demanding workplace from the patient’s perspective [Citation17]. Blue flags, together with red, yellow, orange and black flags constitute the Flags Framework. The concept of the Flags Framework is used to distinguish between various risk factors for chronicity [Citation18]. The presence of red flags can indicate serious underlying medical conditions, whereas one of the other flags (yellow, orange, blue and black) can point towards a prognostically relevant factor [Citation11].

Early identification of blue flags is important for physiotherapists and patients, because the presence of blue flags can be a prognostic factor which can lead to delayed recovery [Citation11]. The presence of work-related psychosocial conditions can be determined by using a questionnaire. Existing questionnaires focus on a broad domain, including education, work and economic life [Citation19–25]. Examples of Dutch questionnaires focussing on work-related factors are the Work Ability Index (WAI) [Citation19,Citation20], the Questionnaire on the Experience and Evaluation of Work (QEEW) (in Dutch: Vragenlijst Beleving en Beoordeling van de Arbeid (VBBA)) [Citation21], the Dutch version of the Work Limitations Questionnaire (WLQ) [Citation22], the Dutch version of the Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ) [Citation23], the Questionnaire Work Reintegration (QWR) (in Dutch: Vragenlijst ArbeidsReintegratie (VAR)) [Citation24] and the Groningen Work experience Screening list (GWS) (in Dutch: Groninger Werkbeleving Screeningslijst (GWS)) [Citation25]. However, these questionnaires cover more factors than blue flags alone. Moreover, the number of questions included in these questionnaires varies between 25 and 243. Therefore, administering a questionnaire during a consultation usually takes a lot of time. This is often a problem, because the time available for a physiotherapy consultation is limited.

Recently, Swedish researchers developed a short clinical questionnaire on work-related psychosocial risk factors: the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire. It is important to note that these psychosocial factors are only one part of the occupational factors. The Swedish researchers examined the validity of this questionnaire and the results showed that the overall validity was acceptable [Citation10]. The ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire is based on ‘The General Nordic Questionnaire for Psychosocial and Social Factors at Work’ (QPSNordic). The QPSNordic can be used to determine psychological, social and organisational working conditions including work-related attitudes [Citation26,Citation27].

The selection of the questions used in the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire was based on scientific literature and the clinical experience of the Swedish researchers who developed the questionnaire [Citation10]. The questions from the QPSNordic which focussed the most on work-related psychosocial risk factors were selected. The ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire covers four content areas and consists of fourteen questions: seven questions cover job demands, two are about social interactions, two are about quantitative demands, two are about equality and the last question focuses on the area of bullying and harassment [Citation10]. The overall validity of the Swedish ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire was considered acceptable [Citation10]. The test-retest reliability of the Swedish ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire has not yet been investigated.

To the best of our knowledge, no short Dutch questionnaire is available for screening for blue flags. Because limited time is available in physiotherapy consultations, it is important to have a short questionnaire to investigate the presence of blue flags. Therefore, the aim of this study was to translate and culturally adapt the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire for use in the Netherlands and to examine the validity and test-retest reliability aspects of the Dutch version.

Methods

The study was conducted in two phases. In the first phase, the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire was translated into Dutch using the guidelines developed by Beaton et al. [Citation28]. The second phase consisted of determining the internal consistency, concurrent validity, structural validity and test-retest reliability of the Dutch ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire using the COSMIN criteria [Citation29–31]. We assumed that the content validity of the original questionnaire would not change during this process. Therefore, we did not assess the content validity of the Dutch version of the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire.

Phase 1: translation and cultural adaptation of the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire

The developers of the original ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire were contacted in order to obtain permission to translate the Swedish questionnaire. Permission was granted and the developers were included in the project group of this project.

In this project, we used the English translation of the validated Swedish ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire [Citation10]. First, three persons independently translated the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire into Dutch. During translation, the questions were culturally adapted to the Dutch situation where needed. However, no specific cultural adaptation was needed. The translators had a background in physical therapy (WO), occupational therapy (SvH) and human movement sciences (YH). All three translators had expertise in occupational healthcare. The three translations were compared to each other to check for potential discordances. A consensus round was conducted with the translators and an independent researcher (NH) to obtain a consensus version. Subsequently, three professional English translators independently translated the questionnaire back into English. Moreover, the consensus version of the Dutch translation was also verified by comparing the original Swedish questionnaire and the English translation made by the Swedish researchers to the newly developed Dutch version. All discrepancies were discussed with the Dutch translators, and consensus was reached about the final version of the Dutch version of the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire (Appendix I). This version was pilot-tested by four people and no further adaption was needed.

Phase 2: determination of the internal consistency, concurrent validity, structural validity and test–retest reliability of the translated questionnaire

Participants

All participants were patients treated by a physiotherapist in the Netherlands. They were recruited from three different Dutch physiotherapy practices, from May to July 2020. The physiotherapy practices were approached by the researchers and asked to participate in this study. Patients were asked to participate by their own physiotherapist. Patients were eligible for participation if they: 1) were between 16 and 67 years old (working age), 2) were being treated by a physiotherapist and 3) were in paid employment 12 h/week. Participants were excluded from participation if they: 1) were on 100% sick leave at the time of recruiting (absenteeism) and/or 2) were insufficiently proficient in Dutch to be able to complete the questionnaire.

Patient recruitment and informed consent

Patients who requested physiotherapy at one of the three different practices and met the inclusion criteria were asked to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria were considered before asking about participation. Patients received a leaflet with information about the study, including an informed consent form, from their physiotherapist. The informed consent form included explanations of the following: the anonymous processing of their data, the voluntary basis of their participation, and the possibility to withdraw from the study at any time without consequences for their treatment. Furthermore, patients were told that the study was being conducted to examine whether the translated questionnaire could be used in the Dutch situation. Participants were asked to complete two online questionnaires about their own experiences regarding their work conditions. At baseline (T0) they were asked to fill in the first questionnaire and approximately two weeks later (T1) they were asked to fill in the second questionnaire.

Patients who were willing to participate in the study filled in the informed consent form at the relevant physiotherapy practice. The completed informed consent forms, including an email address of the participants, were sent to the researchers. As soon as the researchers received the completed informed consent forms, the participants received an email including a link to fill in the first online questionnaire. The questionnaire was developed using the Qualtrics survey tool (https://www.qualtrics.com/). The methods of this study meet the criteria of the Declaration of Helsinki (Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects) [Citation32]. The Medical Ethical Committee of the Radboud University medical centre declared (Registration no. 2020-6820) that no ethical approval was required, because the study did not fall under the Dutch Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act.

Procedures

Patients who were willing to participate and signed the informed consent form were invited to complete the online questionnaire at baseline (T0) and again two weeks later (T1). The participants received an email from the researchers including a link to the online questionnaire. At T0, the questionnaire consisted of the demographic characteristics of the participant, the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire, and selected categories of the QEEW. The categories of the QEEW were included to determine the concurrent validity. At T1, the questionnaire contained only the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire to assess the test–retest reliability. The second questionnaire was sent 14 days after completing the first questionnaire. The exact number of days between T0 and T1 was dependent on how long it took for the participant to fill in the second questionnaire.

The data of all the participants who filled in the questionnaire at T0 was used to determine the validity of the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire (internal consistency, concurrent validity and structural validity). The data of the participants who filled in both questionnaires (T0 and T1) was used to determine the test-retest reliability of the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire. The data of the participants who filled in the questionnaire at T1 was only included in the analysis if they completed the second questionnaire within 22 days after completing the first questionnaire.

Measurements

Demographic data of the participants

The following demographic data of the participants were assessed: age, gender, complaint(s) (type and duration), number of working hours per week, profession, time in current profession and status of current sick leave. Demographic data were collected at T0.

The ‘blue flags’ questionnaire

The ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire consists of fourteen statements [Citation10]. All statements are scored on a five-point scale (0–4). The questionnaire consists of positive and negative statements about work conditions (). The negatively worded statements are scored from ‘totally disagree’ = 0 to ‘totally agree’ = 4. The positively worded statements are scored in the opposite way from ‘totally agree’ = 0 to ‘totally disagree’ = 4.

Table 1. The fourteen questions of the Swedish ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire (unrevised English version) linked to the selected categories of the Questionnaire on the Experience and Evaluation of Work (QEEW).

The questionnaire consists of four factors: job demands (questions 3, 7, 9 and 11), job tasks (questions 1, 2, 4, 8 and 10), equality (questions 12 and 13) and one mixed factor (questions 5, 6 and 14) [Citation10]. The sum of the scores ranges from 0 to 56. The total score of the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire is the sum of all the individual fourteen scores The total score ranges between 0 and 100%. A higher score is associated with a more negative perception of the working conditions and thus with a higher indication for blue flags.

The questionnaire on the experience and evaluation of work (QEEW)

The QEEW consists of 210 individual questions [Citation21]. For this study, specific categories of the QEEW which correspond to the questions of the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire () were selected. The selection of the corresponding questions was based on clinical experience and was done by two authors (AW and NH). The nine selected categories were: ‘task clarity’, ‘problems with the task’, ‘self-reliance at work’, ‘mental stress’, ‘complexity of work’, ‘relationship with direct management’, ‘relationship with colleagues’, ‘work rate and quantity’, and ‘care for well-being’. The selected questions from the first eight categories are scored on a four-point scale. The positively worded questions are scored as follows: ‘never’ = 4; ‘sometimes’ = 3; ‘often’ = 2; ‘always’ = 1. The negatively worded questions are scored in the opposite way: ‘always’ = 4; ‘often’ = 3; ‘sometimes’ = 2; ‘never’ = 1. The last category ‘care for well-being’ is scored on a five-point scale in the same way as the negatively worded statements in the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire: from ‘totally disagree’ = 0 to ‘totally agree’ = 4. The total score ranges from 38 to 172. The total QEEW score is: A higher score is associated with worse working conditions and thus a higher indication for blue flags.

Statistical analysis

The participants’ responses were entered into a database. Statistical analyses were performed using SPPS version 26.0 (SPPS Inc., Chicago, IL) with a level of significance of p < .05. The demographic data of the participants collected at T0 was described by means, standard deviations (SD) for continuous variables and percentages (%) for dichotomous variables.

Internal consistency

Internal consistency of the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire was assessed by calculating Cronbach’s alpha. The size of alpha depends on the mean inter-item correlation and on the number of questions in the questionnaire [Citation33]. Internal consistency is rated based on the interpretation of Cronbach’s alpha. Internal consistency is considered good when Cronbach’s alpha 0.7 [Citation34,Citation35]. The internal consistency was not examined for the subdomains individually, because the questionnaire is intended to be used in its entirety.

Structural validity

Structural validity was assessed by determining the coherence of the individual questions of the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire. It is necessary to know if all the questions measure the same constructs as the original ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire: job demands, job tasks, equality and mixed. To investigate the structural validity, a factor analysis was performed using principal component analysis (PCA) with varimax rotation. The factor loading criterion was set at 0.5, the iterate criterion at 25 and the minimum eigenvalue criterion was set at 1. To assess the factorability of the data, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test and Bartlett’s test of sphericity were performed. A KMO outcome is considered good when the value exceeds 0.6 [Citation36], and Bartlett’s test when the significance is p < .05.

Concurrent validity

Concurrent validity was assessed by determining the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient between the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire and the QEEW. The correlation was assessed for the total score of the questionnaires. Moreover, the item representation was examined. Item representation showed whether the categories of the QEEW correspond well to the questions of the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire and therefore whether the categories were well chosen. The Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was assessed to determine the relationship between the clustered questions of the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire and the related categories of the QEEW (). For example the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was assessed for questions 2 and 3 of the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire and the corresponding category ‘problems with the task’ of the QEEW. The absolute correlation of the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient can be considered weak (0.0–0.3), moderate (0.3–0.5) or strong (0.5–1.0) [Citation37,Citation38]. We expected strong correlations between the clustered questions of the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire and the related categories of the QEEW, because we think the two questionnaires measure the same construct, namely psychosocial risk factors.

Test–retest reliability

The data of the two completed ‘Blue flags’ questionnaires (T0 and T1) was used to determine the test–retest reliability. Based on COSMIN’s recommendations, the elapsed time between T0 and T1 was approximately two weeks [Citation29–31]. The test-retest reliability was assessed by determining the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) between the total score of the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire at T0 and the total score of the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire at T1. Moreover, the ICC was determined for the thirteen questions separately and the individual subdomains by comparing the participants’ scores at T0 and T1. The ICC can be indicative of poor reliability (<0.5), moderate reliability (0.5–0.75), good reliability (0.75–0.9) or excellent reliability (>0.9) [Citation39].

Results

Participants could only submit the questionnaire as completed if they had answered every question. As a result, the data of all participants is complete and there are no missing elements.

Participants

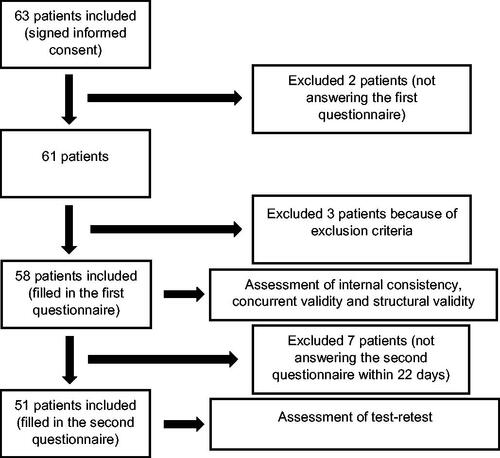

Patients from three different physiotherapy practices participated in the study. In total, 63 patients signed the informed consent form and were invited for the first questionnaire at T0. Three participants were excluded due to the exclusion criteria. One participant was on 100% sick leave and the two other participants did not complete the full questionnaire at T0. Of the remaining 60 potential participants, 58 participants filled in the first questionnaire (T0) containing both the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire and the QEEW (response rate 97%) and 51 of these participants also filled in the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire two weeks later (T1; response rate 88%). shows an overview of the flow chart of participating patients in the study. shows an overview of the demographic characteristics of the study population.

Table 2. Baseline characteristics of participants who completed T0 (n = 58) and who completed T0 and T1 (n = 51).

Revision

In both the Swedish study [Citation10] and our study, question 6 showed a negative correlation with the factor ‘mixed’ in the original study and the factor ‘work climate’ in our study of approximately −0.5. This means that question 6 measures the exact opposite of the extracted factor (‘mixed’/‘work climate’). Moreover, question 6 is the only question in the questionnaire that consists of two separate questions, making it difficult to interpret. Therefore, we decided to run all analyses without question 6.

When question 6 is deleted from the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire, internal consistency rises from 0.78 to 0.83. The structural validity remains the same with a KMO of 0.75, a Bartlett’s test with a significance level of p < .001 and an explained total variance of 70.8%. The same applies for the concurrent validity (from 0.69 to 0.70) and the test-retest reliability (from 0.81 to 0.80).

Due to the negative correlation, the increased internal consistency, the difficult interpretation of question 6, and the fact that the structural validity, concurrent validity, and test–retest reliability do not change when question 6 is deleted, we present these revised results after deleting question 6 from the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire as the final results.

Internal consistency

Cronbach’s alpha for the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire was 0.83. For this reason, the internal consistency is considered good.

Structural validity

The structural validity was satisfactory with a KMO of 0.75 and a significance of p < .001 for the Bartlett’s test of sphericity. All questions in the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire showed satisfactory loadings between 0.53 and 0.85. Four factors were extracted by the analysis. The factors explained 36.7, 14.5, 10.5 and 9.2% of the variance. In summary, the four-factor model explained 70.8% of the total variance. The four factors with corresponding satisfactory loadings are summarised in .

Table 3. The four factors and satisfactory loadings of the ‘Blue Flags’ questionnaire (n = 58).

Concurrent validity

Spearman’s rho between the 13 questions of the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire and the 39 corresponding questions of the QEEW was 0.70 (p < .001). The four QEEW questions regarding mental stress were linked to question 6 and therefore excluded from further analysis. The concurrent validity for the total score was strong. Moreover, the item representation was determined. Spearman’s rho between the clustered questions of the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire and the corresponding categories of the QEEW is summarised in . All correlations are significant (p < .05). The correlations with their corresponding categories of the QEEW were weak for questions 12, 13, 14, moderate for questions 1, 4, 5 and 7 and strong for questions 2, 3, 8, 9, 10 and 11.

Table 4. The ICC for the total score and the individual subdomains between the ‘Blue Flags’ questionnaire at T0 and T1 (test–retest reliability) and the Spearman’s correlation between the ‘Blue Flags’ questionnaire at T0 and the Questionnaire on the Experience and Evaluation of Work (QEEW) at T0 (item representation).

Test–retest reliability

The ICC between the total score of the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire at T0 and the total score of the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire at T1 was 0.80 (p < .001). The test-retest reliability for the total score was good. contains a summary of the ICC for the separate thirteen questions of the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire and the individual subdomains between T0 and T1.

Discussion

This study describes the translation, cultural adaptation and validity and test-retest reliability aspects of the Dutch version of the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire. The Dutch ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire shows good internal consistency, strong concurrent validity and good test–retest reliability. Nevertheless, the factors extracted in the structural validity did not correspond to the factors of the original ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire. This study resulted in a short and easy to use Dutch questionnaire for the assessment of work-related psychosocial risk factors. Generally, the Dutch version of the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire shows satisfactory psychometric properties.

This study confirms the satisfactory internal consistency of the original Swedish version of the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire [Citation10]. In addition, this is the first study to investigate the test–retest reliability of the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire; the study indicates a good test–retest reliability of the Dutch version (ICC 0.80). This signifies that the internal validity of the Dutch version of the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire is good and ensures that the answers to the questionnaire are stable and representative [Citation40].

Post Sennehed et al. [Citation10] developed the original ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire based on the content areas of the QPSNordic questionnaire and also used the QPSNordic questionnaire to examine the concurrent validity. They showed a Spearman’s correlation of 0.87. We used a similar method to determine the concurrent validity. However, no Dutch version of the QPSNordic questionnaire exists, so we selected constructs from the validated Dutch questionnaire named QEEW instead of the QPSNordic. In this study, Spearman’s rho was 0.70. The difference between the extracted Spearman’s rho in this study and the results of Post Sennehed et al. [Citation10] can be explained by the mixed results of the item representation. In addition, questions 12, 13 and 14 in the Dutch version of the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire show a low Spearman’s rho for the item representation with ‘welfare orientation’ (0.27). The low correlation is not surprising since the ‘welfare orientation’ questions of the QEEW are formulated more generally and therefore are not fully comparable with questions 12, 13 and 14. Moreover, the high correlation of Post Sennehed et al. [Citation10] is not surprising since they selected the questions of the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire from the QPSNordic. However, both Spearman’s correlations are considered strong. Moreover, our results show an internal consistency of 0.83, which is comparable to the results of the original Swedish ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire.

The strengths of this study include the rigorous translation and cultural adaptation of the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire for the Netherlands. Moreover, we included patients from three different physiotherapy practices located in different areas of the Netherlands, which enhances the generalisability of the study results. Generalisability is also enhanced by inviting patients regardless of their complaints, while Post Sennehed et al. [Citation10] included only patients with acute or subacute non-specific back pain participating in a randomised controlled trial. This study provides ratification of the psychometric properties of the original ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire. Moreover, this is the first study to investigate the test-retest reliability of the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire. This study resulted in, as far as we know, the first Dutch short questionnaire for the assessment of work-related psychosocial risk factors.

This study also has some potential limitations. With regard to test–retest reliability, we chose an interval of two weeks, based on COSMIN’s recommendations [Citation29–31]. The interval between T0 and T1 varied from 14 to 22 days. This could have influenced the results of the test–retest reliability. The time interval should be long enough to prevent recall, but short enough to ensure that the work environment and the patients remain stable [Citation29,Citation41]. We expect that the patients’ situation concerning work-related psychosocial risk factors was generally stable throughout this 22-d period. However, we did not use any method to ensure this stability. Another limitation of this study could be the influence of the COVID-19 crisis on the work situation of the participants. The questionnaire was filled in between May and July 2020. During this period, many people were working from home. However, some participants might have resumed working at their workplace from the end of June. This could have had a negative impact on the test–retest reliability. Nevertheless, the test–retest reliability was considered as good. Another limitation of this study is the absence of patient involvement during the translation process. Last of all, our sample of participants differs from the sample of Post Sennehed et al. [Citation10] with regards to the sick leave. Within our sample, 8% of the participants was on current sick leave while in the sample of Post Sennehed et al. 35% was on sick leave. People on 100% sick leave are excluded, because they are not working when filling in the questionnaire.

Post Sennehed et al. [Citation10] extracted a four-factor model in their study, using PCA with varimax rotation. We also found a four-factor model in this study with a significant Bartlett’s test and a KMO value above 0.6. However, the clustering of questions is different compared to the original study [Citation10]. In the original questionnaire, the extracted factors consisted of questions 3, 7, 9 and 11, questions 1, 2, 4, 8 and 10, questions 12, 13 and questions 5, 6 and 14. Our study extracted factors which represent questions 4, 5, 7, 8 and 9, questions 2, 12, 13 and 14, questions 1 and 10 and questions 3 and 11. The extracted factors in the original study represented job demands, job tasks, equality and mixed [Citation10]. In this study, we can interpret the factors we found differently: as support and control, work climate, job tasks and work demands. The factors of the Dutch ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire cannot be recognised in the factors of the Swedish ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire. It should be noted that the outcomes of the structural validity in the original study of Post Sennehed et al. [Citation10] also did not result in the factors on which the development of Swedish the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire is based. The factors on which the Swedish ‘Blue flags’ questionnaires is based are job demands, social interactions, quantitative demands, equality and bullying and harassment. The difference in the results may be due to the translation into a different language and different culture, different patient groups and different settings of patient inclusion. Moreover, it should be noted that the Dutch version of the ‘Blue Flags’ questionnaire was based on the English translation of the validated Swedish questionnaire. The structural validity is also more open to interpretation. We included a total of 58 participants in our study to determine the validity and 51 participants to determine the reliability. The COSMIN checklist takes the sample size into account when judging the adequacy of the validity and reliability [Citation29]. According to this checklist, the internal consistency of our study is adequate, the structural validity is inadequate, the concurrent validity is very good and the reliability is adequate. For an adequate structural validity, at least 78 participants should be included. Further research should focus on a large sample to examine the structural validity.

This study will have direct implications on physiotherapy. Up until now, no short Dutch questionnaire has been available to measure work-related psychosocial risk factors during a consultation. This study shows that the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire can be used in physiotherapy practices, without question 6. Moreover, the questionnaire can also be used by other healthcare providers and in research. It should be noted that the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire is not suitable for independent entrepreneurs as some questions are about colleagues and the employer. Future research is recommended to examine the responsiveness and predictive validity of the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire. Moreover, the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire would benefit from a few additional questions on ergonomics or the physical work environment. In that way, the questionnaire would not only measure work-related psychosocial factors, but all aspects of occupational factors.

In conclusion, the results of the study show that the Dutch translation of the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire has good internal consistency, strong concurrent validity and good test–retest reliability. The extracted factors in the structural validity do not correspond to the extracted factors of the original ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire. The translation and cultural adaptation of the Swedish ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire for the Netherlands can be considered successful and has resulted in a short and easy to use 13-question (without question 6) Dutch questionnaire for the assessment of work-related psychosocial risk factors. However, further research on the structural validity is recommended. This is the first study which examines the reliability of the ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire and translates the Swedish version into another language. Due to the sufficient results, future research can also translate the Swedish version into other languages.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The Medical Ethical Committee of the Radboud university medical centre declared (Registration no. 2020-6820) that no ethical approval was required, because the study did not fall under the Dutch Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. The informed consent contained consent to participate and consent to publish the study results.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all patients and physiotherapists involved in the study.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Data availability statement

This data is not publicly available, but is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Centraal Bureau Voor de Statistiek (CBS). Labor participation; key figures. 2020 [accessed 9 Mar 2020]. Available from: https://opendata.cbs.nl/statline/#/CBS/nl/dataset/82309ned/table?fromstatweb

- Bond MA, Punnett L, Pyle JL, et al. Gendered work conditions, health, and work outcomes. J Occup Health Psychol. 2004;9(1):28–45.

- Ose SO. Working conditions, compensation and absenteeism. J Health Econ. 2005;24(1):161–188.

- Fransen L. Work and health in interaction. Mijn Gezondheidsgids. 2018. Available from: http://resolver.tudelft.nl/uuid:9ee8a817-497a-4b24-820f-276b958ae7ba

- Douwes M, Genabeek J, van den Bossche S, et al. Health and safety balance 2016: quality of work, effects and measures in the Netherlands. Leiden: De Nederlandse organisatie voor toegepast-natuurwetenschappelijk onderzoek (TNO). 2016.

- Schultz AB, Chen CY, Edington DW. The cost and impact of health conditions on presenteeism to employers: a review of the literature. Pharmacoeconomics. 2009;27(5):365–378.

- Duffy RD, Kim HJ, Gensmer NP, et al. Linking decent work with physical and mental health: a psychology of working perspective. J Vocation Behav. 2019;112:384–395.

- Leijten FR, van den Heuvel SG, van der Beek AJ, et al. Associations of work-related factors and work engagement with mental and physical health: a 1-year follow-up study among older workers. J Occup Rehabil. 2015;25(1):86–95.

- Dehue F, Bolman C, Völlink T, et al. Coping with bullying at work and health related problems. Int J Stress Manag. 2012;19(3):175–197.

- Sennehed CP, Gard G, Holmberg S, et al. “Blue flags”, development of a short clinical questionnaire on work-related psychosocial risk factors-a validation study in primary care. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017;18(1):318.

- Swaan J, Preuper HS, Smeets R. Multifactorial analysis in specialist medical rehabilitation. In: Handboek Pijnrevalidatie. Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum; 2019. p. 69–85.

- Siegrist J, Starke D, Chandola T, et al. The measurement of effort–reward imbalance at work: European comparisons. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(8):1483–1499.

- Jayaratne S, Himle D, Chess WA. Dealing with work stress and strain: Is the perception of support more important than its use? J Appl Behav Sci. 1988;24(2):191–202.

- Lemyre L, Chair MR, Lalande-Markon MP. Psychological stress measure (PSM-9): Integration of an evidence-based approach to assessment, monitoring, and evaluation of stress in physical therapy practice. Physiother Theory Pract. 2009;25(5–6):453–462.

- Landsman-Dijkstra JJ, van Wijck R, Groothoff JW. Improvement of balance between work stress and recovery after a body awareness program for chronic aspecific psychosomatic symptoms. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;60(2):125–135.

- Shaw WS, Van der Windt DA, Main CJ, et al. Early patient screening and intervention to address individual-level occupational factors (“blue flags”) in back disability. J Occup Rehabil. 2009;19(1):64–80.

- Nicholas MK, Linton SJ, Watson PJ, et al. Early identification and management of psychological risk factors (“yellow flags”) in patients with low back pain: a reappraisal. Phys Ther. 2011;91(5):737–753.

- Mulders N, Boersma R, Ijntema R, et al. Professional competence profile Psychosomatic Physiotherapy. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Fysiotherapie volgens de Psychosomatiek. 2009. Available from: https://www.kngf.nl/binaries/content/assets/kngf/onbeveiligd/vakgebied/vakinhoud/beroepsprofielen/beroepsprofiel-psychosomatisch-fysiotherapeut.pdf

- Radkiewicz P, Widerszal-Bazyl M, NEXT-Study Group. Psychometric properties of Work Ability Index in the light of comparative survey study. Int Congress Series. 2005;1280:304–309.

- De Zwart B, Frings‐Dresen M, Van Duivenbooden J. Test–retest reliability of the Work Ability Index questionnaire. Occup Med. 2002;52(4):177–181.

- Meijman T, Broersen J, Fortuin R. Manual VBBA. Amsterdam: SKB Vragenlijst Services; 2002.

- Lerner D, Amick III BC, Rogers WH, et al. The work limitations questionnaire. Medl Care. 2001;28:72–85.

- Karasek R, Brisson C, Kawakami N, et al. The Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ): an instrument for internationally comparative assessments of psychosocial job characteristics. J Occup Health Psychol. 1998;3(4):322–355.

- Vendrig A. De vragenlijst arbeidsreïntegratie. Diagnostiek-wijzer. 2005;8:27–39.

- Heinen S, Bakker R, Brouwer S, et al. Betrouwbaarheid en validiteit van de Groninger Werkbeleving Screeningslijst (GWS). Tbv - Tijdschrift Voor Bedrijfs- en Verzekeringsgeneeskunde. 2014;22(1):15–21.

- Lindström K. Review of psychological and social factors at work and suggestions for the General Nordic Questionnaire: Description of the conceptual and theoretical background of topics selected for coverage by the Nordic questionnaire (QPSNordic). Copenhagen, Denmark: Nordic Council of Ministers. 1997.

- Wännström I, Peterson U, Åsberg M, et al. Psychometric properties of scales in the General Nordic Questionnaire for Psychological and Social Factors at Work (QPS): confirmatory factor analysis and prediction of certified long-term sickness absence. Scand J Psychol. 2009;50(3):231–244.

- Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, et al. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine. 2000;25(24):3186–3191.

- Mokkink L, Prinsen C, Patrick D, et al. COSMIN study design checklist for patient-reported outcome measurement instruments. 2019. Available from: https://www.cosmin.nl/wp-content/uploads/COSMIN-study-designing-checklist_final.pdf

- Mokkink LB, De Vet HC, Prinsen CA, et al. COSMIN risk of Bias checklist for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(5):1171–1179.

- Terwee CB, Prinsen CA, Chiarotto A, et al. COSMIN methodology for evaluating the content validity of patient-reported outcome measures: a Delphi study. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(5):1159–1170.

- Association WM. World medical association declaration of Helsinki. Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Bull World Health Organization. 2001;79(4):373.

- Gliem JA, Gliem RR. editors. Calculating, interpreting, and reporting Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient for Likert-type scales. Midwest Research-to-Practice Conference in Adult, Continuing, and Community. 2003. Available from: http://pioneer.netserv.chula.ac.th/∼ppongsa/2013605/Cronbach.pdf

- Tavakol M, Dennick R. Making sense of Cronbach's alpha. Int J Med Educ. 2011;2:53–55.

- Adamson KA, Prion S. Reliability: measuring internal consistency using Cronbach's α. Clinical Simulation in Nursing. 2013;9(5):e179–e180.

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS, Ullman JB. Using multivariate statistics Boston (MA): Pearson; 2007.

- Mukaka MM. A guide to appropriate use of correlation coefficient in medical research. Malawi Med J. 2012;24(3):69–71.

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Cambridge (MA): Academic Press; 2013.

- Koo TK, Li MY. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J Chiropr Med. 2016;15(2):155–163.

- Heale R, Twycross A. Validity and reliability in quantitative studies. Evid Based Nurs. 2015;18(3):66–67.

- Altman DG. Practical statistics for medical research. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press; 1990.

Appendix I.

The final version of the Dutch ‘Blue flags’ questionnaire. Please note that question 6 was deleted and that the questions were re-numbered

Instructie: Bekijk de antwoordmogelijkheden voor elke vraag. Lage scores betekenen niet altijd goede omstandigheden.