ABSTRACT

The quality of teacher-student relationships (TSRs) has been shown to predict various academic and social, emotional, and behavioral outcomes for adolescent students and is also one of the most important aspects of teacher wellbeing. Therefore, measures of TSRs are essential for schools as they provide insight into the quality of these relationships. Many theoretical frameworks have been used to explain the importance of TSRs, yet conceptualizations of TSRs in the literature have narrowly focused on Western cultures. Thus, the purpose of this study was to explore the varied conceptualizations of TSRs across cultures by examining the items across student and teacher-reported measures of adolescent TSRs. A review of the literature identified 25 rating scale measures of TSRs that had been specifically developed and validated for use with adolescents across Asia, Europe, and North America. Thematic analysis suggested six major themes that are relevant to adolescent TSRs: positive teaching qualities; negative interpersonal interactions; classroom management; instructional methods; positive student qualities, and classroom climate. How these themes were conceptualized, however, varied by geographic region.

Abstracto

Se ha demostrado que la calidad de las relaciones entre profesor y alumno predice diversos resultados académicos, sociales, emocionales y de comportamiento para los alumnos adolescentes y también que es uno de los aspectos más importantes del bienestar de los profesores. Por lo tanto, las medidas de las relaciones profesor-alumno (RPAs) son esenciales para las escuelas, ya que brindan información sobre la calidad de estas relaciones. Se han utilizado muchos marcos teóricos para explicar la importancia de estas relaciones, pero las conceptualizaciones en la literatura se han centrado limitadamente en las culturas occidentales. Por lo tanto, el propósito de este estudio fue explorar las conceptualizaciones variadas de las RPAs en varias culturas examinando las preguntas en las medidas de RPAs informadas por alumnos y profesores. Una revisión de la literatura identificó 25 medidas de escala de calificación de RPAs que han sido desarrolladas y validadas específicamente para el uso con adolescentes en Asia, Europa y América del Norte. El anñlisis temático sugirió que hay seis temas principales que son relevantes para las RPAs adolescentes: cualidades de enseñanza positiva; interacciones interpersonales negativas; la gestión del aula; métodos de instrucción; cualidades positivas de los alumnos; y ambiente del aula. Sin embargo, la forma en que se conceptualizaron estos temas varió según la región geográfica.

As children transition into adolescence, they are expected to navigate the challenges that come with the physical (e.g., puberty, sexual maturation), emotional (e.g., self-esteem), behavioral (e.g., social relationships, engagement in problem behaviors), and structural changes (e.g., school transitions, learning expectations) typical of this developmental period (Gutman & Eccles, Citation2007). According to the stage-environment fit theory, adolescents’ environments must have sufficient structure and predictability while also allowing for opportunities for growth and independence (Eccles et al., Citation1996). Teachers must therefore be able to maintain this balance between providing structure and allowing for growth for students to remain academically engaged and motivated (Eccles et al., Citation1996, Zimmer-Gembeck et al., Citation2006). Unfortunately, however, it can be difficult to form positive teacher-student relationships (TSRs) that are necessary for adolescent success, with the rotating schedules and the increased teacher to student ratio that are standard of most secondary schools (McGrath & Van Bergen, Citation2015, Zandvliet et al., Citation2014). As a result, the quality of TSRs tends to decline as students move on to middle and high school, particularly within Western contexts (McGrath & Van Bergen, Citation2015, Spilt et al., Citation2011). This is unfortunate given the impact that the quality of TSRs can have on adolescent development.

Pianta and colleagues (Citation2003) define TSRs as dynamic and reciprocal systems that influence the development of a child. These systems can be shaped by the characteristics of the student and teacher, the representation of these relationships (i.e., role in the relationship, views on the relationship), the exchange of information (e.g., interactions, communication), and external influences (e.g., schools, classrooms, communities; Pianta et al. Citation2003). TSRs are considered to be positive when they are beneficial to the needs of those in the relationship (McGrath & Van Bergen, Citation2015). Research suggests that TSRs are reciprocal, in that a positive relationship may be beneficial for both students and teachers. The quality of TSRs has been shown to be an important predictor of various academic and social, emotional and behavioral outcomes for students including academic achievement (e.g., Crosnoe et al., Citation2004, Roorda et al., Citation2011), disciplinary problems (e.g., Crosnoe et al., Citation2004, Wang et al., Citation2013), and emotional functioning (e.g., Reddy et al., Citation2003, Wang et al., Citation2013). Furthermore, positive TSRs may also be beneficial for teachers’ professional wellbeing as they can typically find these relationships incredibly rewarding (Spilt et al., Citation2011). Having a positive relationship with students can be motivating, an important source of enjoyment, and is associated with greater job satisfaction and higher self-efficacy (Spilt et al., Citation2011, Taxer et al., Citation2019).

Measuring and conceptualizing teacher-student relationships

Measures of TSRs are essential for schools. Not only do these measures provide insight into the quality of these relationships, which can be used to predict student and teacher outcomes, but these measures may also be used to provide guidance for professional development to improve relationships between students and teachers (e.g., relationship building, classroom management). Although the literature on TSRs has largely focused on measuring dyadic (i.e., one-to-one) relationships between a single teacher and student (Pianta et al., Citation2003, Spilt & Koomen, Citation2022), measures of global level TSRs (i.e., one student’s relationship with multiple teachers) have also been found to be relevant to adolescent students as they are often interacting and building relationships with multiple teachers (Liu et al., Citation2018, Pianta et al., Citation2003). Throughout the literature, TSRs have been assessed in various ways including through the use of structured observations (e.g., Classroom Assessment Scoring System; Pianta et al., Citation2008) and drawing techniques (e.g., Student Teacher Relationship Drawings; Harrison et al., Citation2007). The use of rating scales (e.g. Student Teacher Rating Scale; Pianta, Citation2001), however, has been most common given the ability to efficiently collect information from both the perspective of the student and the teacher (Brinkworth et al., Citation2018, Mercer & DeRosier, Citation2010, Phillipo et al., Citation2017).

Although rating scales have most commonly been used to assess TSRs, the ways in which TSRs have been measured within the literature has certainly varied. Arguably the most referenced framework for conceptualizing TSRs comes from Pianta (Citation2001), who, drawing from attachment theory (Bowlby, Citation1969), identified three dimensions of closeness, conflict, and dependency. Closeness (Pianta, Citation2001) refers to the warmth, affection, and open communication that is experienced in the relationship, which allows students to feel comfortable seeking support from their teacher. Similarly, within interpersonal theory, it is suggested that the degree to which there is communion (i.e., cooperation, agreeableness, connection) between teachers and students is an important predictor of student outcomes (Horowitz & Strack, Citation2010, Wubbels & Brekelmans, Citation2005). A relationship characterized by conflict (Pianta, Citation2001), or low communion (i.e., quarrels, opposition; Wubbels & Brekelmans, Citation2005), tends to be negative and discordant and can result in resistance in relationship-building from both the student and the teacher. Finally, dependency (Pianta, Citation2001), or over-reliance on a teacher, can be an important indicator of students’ school adjustment among Western contexts (Roorda et al., Citation2021). The importance of affective qualities in TSRs has also been emphasized through other theoretical lenses, including nurturance (i.e., Baumrind’s (Citation1967) parenting style theory; see also, Walker (Citation2009), emotional and instrumental support (i.e., House’s (Citation1981) framework of social support; see also Malecki and Demaray (Citation2003), and involvement (i.e.,Skinner and Belmont’s (Citation1993) model of motivation).

Beyond the affective quality of the relationship between a student and their teacher(s), however, there are other dimensions of these relationships that have been emphasized as playing an important role in student development that seem to relate to teaching and classroom management. For example, House’s (Citation1981) framework of social support also identifies more practical forms of support for learning including providing a student with information (i.e., informational support) and evaluative feedback (i.e., appraisal support). Skinner and Belmont’s (Citation1993) model of motivation, which is based in self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, Citation1985), refers to the importance of providing choice and connecting students to activities that align with their interests (i.e., autonomy support). The importance of establishing and communicating clear and consistent demands of students, and increasing these demands according to maturity and capacity, is also referenced in this model of motivation (i.e., structure; Skinner & Belmont, Citation1993) and in parenting style theory (i.e., control, Baumrind, Citation1967). Similarly, interpersonal theory highlights the extent to which teachers exhibit agency (i.e., the extent to which teachers are more dominant or submissive) as an important aspect of how teachers and student interact (Horowitz & Strack, Citation2010, Wubbels & Brekelmans, Citation2005).

The degree to which inconsistencies exist across measures of TSRs was recently highlighted by a systematic review of the literature conducted by Phillipo and colleagues (Citation2017). In reviewing 66 studies utilizing adolescent self-report measures of TSRs between 1989 and 2013, the authors found that over half of the measures contained items assessing the degree to which students feel that their teacher cares about and listens to them. A great deal of inconsistency, however, was identified across studies with regard to both the domains included and the items used to measure those domains. Phillipo et al. (Citation2017) also found that many of the studies did not describe or address the validity or reliability of the data obtained. Their review was limited, however, in its focus on self-report measures completed by students in North America. As a result, the perspectives of teachers and those outside of the North American continent are missing.

Understanding TSRs cross-culturally

How TSRs are understood and measured can vary by local cultural context as cultural factors are likely to influence how teachers and students interact with one another. Hofstede (Citation1983) suggested that cultures can vary along four dimensions, three of which may be of particular relevance to understanding TSRs. The first is power distance, which refers to the extent to which there is hierarchy in relationships (Hofstede, Citation1983). In countries where there tends to be a smaller power distance (e.g., Denmark, Netherlands, United States), teachers may try to minimize the differences between teachers and students (Hofstede, Citation1983, Kirkebæk et al., Citation2013). Conversely, in countries where there tends to be a greater power distance (e.g., China, Mexico, Philippines), a hierarchical relationship between teachers and students may be expected, where teachers are positioned as experts or role models (Hofstede, Citation1983, Li, Citation2012).

The second dimension presented by Hofstede (Citation1983) is the extent to which cultures identify as individualistic or collectivistic. Among more individualistic cultures, as is typical of many Western countries, there tends to be a greater focus on achieving independence and expression of one’s uniqueness, whereas in more collectivistic cultures, there is more interdependence in social relationships and a motivation to fit in with others (Markus & Kitayama, Citation1991). Consequently, these differences in the perception of the self are likely to influence the interpersonal qualities students and teachers value in one another.

Finally, Hofstede (Citation1983) proposed that countries vary according to the extent to which they value traditionally masculine qualities, such as recognition, challenges, and advancement. Countries such as Japan, India, Canada, and Venezuela tend to have high masculinity index scores while Sweden, France, and Chile tend to have lower scores (Hofstede, Citation1983). This may influence teachers’ and students’ expectations of one another regarding their approach to academics.

Focusing on North American measures alone limits our overall understanding of TSRs because, ultimately, cultural norms and values inform the behaviors we expect from students and from teachers. Therefore, it is important to consider how diverse perspectives can inform our conceptualization of TSRs (Aldhafri & Alhadabi, Citation2019, Ang, Citation2005, Sun et al., Citation2017).

Purpose of study

Given the predominance that Western perspectives appear to have on our understanding of TSRs in adolescence, the purpose of this study was to explore the varied conceptualizations of TSRs across psychometrically defensible rating scales specifically designed for adolescents. For the purpose of this review, psychometrically defensible rating scales are defined as measures for which reliability and/or validity is reported. The following research questions were used to guide the present review: (a) What psychometrically defensible rating scales exist to assess TSRs in grades 6 through 12, globally? (b) What constructs are explored in the identified measures? (c) Is there a consensus across geographical regions as to how TSRs in grades 6 through 12 are conceptualized?

Method

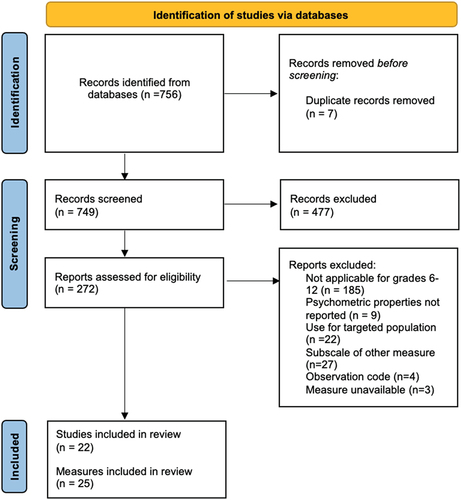

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were followed to identify empirical, peer-reviewed studies or dissertations reporting on the psychometric properties of TSR measures (see ).

Eligibility criteria and search strategy

The following criteria were used to identify articles for inclusion. First, the articles had to be published in English and either in a peer-reviewed journal or available through ProQuest Dissertations. Second, the article had to report on the initial development of a rating scale primarily designed to measure dyadic or global TSRs, or related components of TSRs (e.g., teacher caring, support), from the perspective of a teacher and/or a student. Third, the rating scale had to be developed for and validated with students in grades 6 through 12. We excluded measures that were initially developed for another population but validated with adolescents given our interest in identifying those components of TSRs most relevant to adolescent development. Fourth, the study had to be empirical in nature, in that it reported on the psychometric properties (e.g., reliability, validity) of the rating scale. The goal of this inclusion criterion was to ensure that all identified measures had some level of psychometric evidence. Fifth, the study was included if the rating scale was designed for the general population as opposed to a target population (e.g., students with autism, students in specific classroom subjects). This focus on the general population was determined to be relevant given that unique aspects of TSRs may be emphasized when focused on specific populations. Finally, the study was included if the items for the rating scale were available, as these items would be used for qualitative analysis.

A search was conducted on the PsycINFO and ERIC electronic databases between August 18, 2021 and January 31, 2022 using a combination of the following search terms: “teacher-student relation*,” “teacher-student interaction*,” “teacher-child relations*,” “test validity,” “test reliability,” “psychometric*,” “dependability,” “factor analysis,” and “measure*.” No restrictions were put on the year in which the article was published. The articles identified were exported onto a shared server to be coded later.

Data coding

Once the authors determined that the article met the eligibility criteria, descriptive information was extracted from each study into an Excel spreadsheet within each geographic region that was identified from the measures (i.e., Asia, Europe, North America). Demographic information coded included: (a) the informant (i.e., teacher, student, or both) and (b) age and/or grade level of student participants. Information on the composition of the measure coded included: (a) the name of the measure, (b) country of origin, (c) intended language, (d) the subscales included in each measure (if applicable), and (e) the items included within each subscale. Finally, evidence of reliability and validity was collected for both the overall measure and/or the individual subscales. Specifically, we sought to determine whether the study reported on the reliability (e.g., internal consistency, test-retest, inter-rater agreement) and/or validity (e.g., concurrent, discriminative validity, predictive) of the obtained data.

Data analysis

To address our first research question of what psychometrically defensible measures exist to assess TSRs globally, descriptive information was compiled for each of the measures that met inclusion criteria (e.g., name of the measure, country of origin, intended language). To address our second research question of what constructs are measured amongst the identified measures of TSRs the item-level data were qualitatively analyzed. Using the item-level information, two members of the research team independently conducted a thematic analysis, following procedures outlined by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006), to inductively identify themes within each geographical region. First, we used the information that was gathered regarding the country in which the measure was developed and organized the measures by geographical regions. The authors determined by consensus that a minimum of two measures were needed for a particular region to be included in this region-level analysis. Second, all items within the geographical region were randomized and then organized into initial themes. For items to be considered a theme, at least two items were needed that either used similar terminology or described a similar concept (e.g., “Teachers should care about me” and “Teachers should be considerate and thoughtful of me” describe a similar concept, “Caring Teacher”). Next, these initial subthemes were reviewed and combined, when appropriate, to establish larger themes (e.g., “Compassionate Teacher” and “Caring Teacher” are both positive, affective qualities). Finally, each of the themes identified were defined. After each researcher independently completed the thematic analysis, two of the authors met to cross-check the coding, resolve any discrepancies, and finalize the themes. Items with multiple or unclear interpretations were excluded from the analysis (e.g., “Comments on students’ ideas only after more thorough exploration”). Finally, to address our third research question related to whether there was consensus across regions as to how TSRs are conceptualized, the authors examined the extent to which any of the identified themes were common across at least two of the regions.

Results

Identified measures

A total of 25 rating scale measures of TSRs published between 1999 and 2020, from both the teacher and the student perspectives, were identified through the current study (see and ). The greatest number of measures was identified in North America (n = 12), followed by Asia (n = 8), and then Europe (n = 5). Most of the measures included the student as the informant to assess their relationship with their teacher (n = 16; 64%) and were originally designed for participants whose primary language was English (n = 15; 60%). In Europe, there was one measure that was developed from the teacher’s perspective, whereas half (n = 4) of the measures developed in Asia were from the teacher’s perspective (20%). In North America, one measure was developed from the teacher’s perspective and three (12%) measures were designed for both the student and teacher’s perspectives. Some level of reliability evidence was provided for each of the measures reviewed; however, validity evidence was less consistently reported. More detailed information regarding the quality of psychometric evidence reported for each measure and/or constructs within that measure is presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Table 1. Teacher-student relationship: measure composition for teacher report.

Table 2. Teacher-student relationship: measure composition for student report.

Thematic analysis

The subthemes and themes that were identified from the thematic analysis conducted across Asia, Europe, and North America can be found in . Across all regions, six themes were identified: Positive Teacher Qualities, Negative Interpersonal Interactions, Classroom Management, Instructional Methods, Positive Student Qualities, and Classroom Climate. Each is described below.

Table 3. Results from the Thematic Analysis on measures of teacher-student relationships.

Positive Teacher Qualities

Across all three regions, Positive Teacher Qualities was one of the most robust themes, with 14 subthemes in this category. Positive Teacher Qualities refers to the affective, interpersonal qualities that teachers bring into the relationship. Within this theme, there were two subthemes that were consistent across all three regions. Likable Teacher includes items assessing whether teachers are liked by students, use humor, and have a friendly demeanor whereas Trusting Relationship refers to the extent to which a student feels as though they are able to confide to their teacher about personal problems and that their teachers will be sympathetic. Next, there were three subthemes that were common across two regions. The two subthemes shared across Asian and European measures were (a) Compassionate Teacher, which refers to the extent to which teachers know how their students feel and can respond to students with compassion and (b) Provides Help, which refers to the extent to which teachers help students, particularly with personal problems. Caring Teacher was a subtheme identified in the Asian and North American measures; it is defined as the extent to which teachers care about students and know about their interests, goals, and life outside of school.

Nine additional subthemes were only identified within one particular region. The three subthemes unique to the Asian measures were Social Teacher (i.e., a teacher who enjoys talking to others, is willing to share personal information, and is in communication with students and families), Conflict Resolution (i.e., the extent to which teachers avoid or resolve conflict with students), and Non-Verbal Communication (i.e., ability of teachers to read social cues and use non-verbal forms of communication to communicate empathy and support). Within Europe, the two unique subthemes were Student Seen as an Individual (i.e., extent to which students feel that teachers respect their students’ opinions and know the student as an individual) and Student at Ease (i.e., extent to which students feel comfortable around their teacher’s presence). Finally, the four subthemes unique to North America were Active Listening (i.e., teachers who carefully listen to their students when they have something to say), Patience (i.e., extent to which teachers are patient while teaching students and whether students feel comfortable asking questions and expect that their teachers will answer them), Teacher Availability (i.e., extent to which the teacher spends sufficient time with students and is available to talk when needed), and Respect and Fairness (i.e., extent to which students feel they are treated with fairness and respect by their teachers).

Negative Interpersonal Interactions

Although common across all three regions, Negative Interpersonal Interactions was one of the smaller themes to emerge, and it refers to the interpersonal qualities that contribute to negative TSRs from both the teachers’ and students’ perspectives. Conflict was a subtheme that was identified across all three regions and refers to teachers being perceived as unfair and behaving in a way that results in student anger and/or frustration. Additionally, Teacher Dependency was identified as a subtheme in Europe, and is defined as students who heavily rely on their teacher for validation.

Classroom Management

Classroom Management was another theme that was shared across all regions. This theme refers to the strategies teachers use to respond to student behavior and to ensure that classes run smoothly. Specifically, Asian and North American measures included items relating to Behavior Expectations and European measures included items on Behavior Management, which not only refers to teachers setting clear behavior expectations that students are expected to follow but also the extent to which teachers feel capable of responding to disruptive behaviors. Additionally, Flexible Teacher was unique to Asia, referring to teachers who are flexible about rules and schedules and can adapt their behavior. Classroom Management was only identified in North America and refers to the extent to which teachers are well-prepared for the day, remain on task, and set clear classroom expectations.

Instructional Methods

The second largest theme identified across all three regions was Instructional Methods, with seven distinct themes in this category. Instructional Methods refers to the strategies teachers use to ensure that students are actively engaged in learning and achieving their highest academic potential. Within this theme, Effective Teaching Strategies was the only subtheme that was consistent across all three regions. This is defined as teachers using a variety of teaching strategies that help students learn and understand the material and stay engaged. Additionally, consensus was found for three themes, which were common across Asian and North American measures. The first, Academic Expectations, refers to teachers setting high academic expectations for student success. The second, Recognition and Merit, refers to the extent to which teachers recognize student achievement. Finally, when teachers Challenge Student Academically, they encourage students to be independent thinkers and learners and to apply what they have learned in different ways.

Additional subthemes were unique to a particular geographic region. First, Fostering Confidence, which was unique to the Asian measures, refers to the extent to which teachers encourage students to be proud of their achievements and to learn from failure. Second, there were two additional themes unique to the North American measures. Encouraging Teacher refers to the extent to which teachers provide students with words of encouragement, whereas Provides Academic Help refers to the extent to which teacher help students with school related problems.

Positive Student Qualities

Positive Student Qualities refers to the interpersonal qualities that students bring into the relationship and contribute to positive TSRs. It was a relatively small theme that was identified in Asian and North American measures. The subtheme Likable Student was identified in Asian measures, which refers to the extent to which teachers are happy with their relationship with a student and that the student is generally liked. The one subtheme identified in the North American measures was Teacher’s Trust, which is defined as teachers trusting their students.

Classroom Climate

Classroom Climate was another relatively small theme identified across all three regions. It generally refers to a teacher’s ability to create a learning environment where students are valued. Both Asian and European measures included items relating specifically to Classroom Climate, or a teacher’s ability to create a pleasant and friendly environment where positive interaction between peers are encouraged and teachers value students’ opinions. In North America, measures included items specifically relating to Belonging, which is defined as the extent to which students feel that they liked by their teachers and peers.

Discussion

The relationships that teachers co-create with adolescents can be a formative experience for students. The quality of these relationships can not only predict students’ academic success, but can also be an important aspect of student, and teacher, emotional wellbeing (Crosnoe et al., Citation2004, Reddy et al., Citation2003, Spilt et al., Citation2011). Therefore, it is important to have measures that accurately capture the quality of these relationships by examining the dimensions that are important to adolescent TSRs. Our conceptualization of TSRs remains unclear, however, and often centers on Western perspectives. Therefore, the purpose of this systematic review was to take a cross-cultural approach to understand how TSRs are measured, and thus conceptualized.

Through this study, a total of 25 rating scales were identified that (a) were designed to assess TSRs in grades 6 through 12 in Asia, Europe, and North America and (b) provided some level of psychometric evidence. The greatest number of measures was identified in North America and the fewest number of measures was identified in Europe. Across all regions, it was common to measure the quality of TSRs from the perspective of the student. However, half of the measures developed in Asia were from teachers’ perspectives. Additionally, North America was the only region to include student and teacher versions of the same measure within the study. Results from the thematic analysis suggests that there were six overall themes that can define TSRs in adolescence.

Positive Teacher Qualities was the most robust theme, which suggests universal agreement that measuring the extent to which teachers exhibit positive qualities (e.g., caring, compassionate, patient) is an important indicator of the quality of TSRs. Subthemes within this theme align with constructs across multiple theories (e.g., emotional involvement from models of motivation, Skinner & Belmont, Citation1993; nurturance from parenting-style theory, Baumrind Citation1967). What the item-level thematic analysis revealed, however, was that the specific Positive Teacher Qualities emphasized varied by region. For instance, although all regions included items relating to the extent to which teachers are generally liked by students and that students feel that they can confide in their teacher about personal problems, only the Asian and European measures included items assessing the extent to which teachers help students and respond to them with compassion. Furthermore, Asian measures uniquely included items relating to the extent to which teachers attempt to avoid or resolve conflict with students, only European measures included items relating to the extent to which teachers saw students as individuals, and only North American measures included items relating to the extent to which teachers were perceived to treat students with respect.

The Negative Interpersonal Interaction and Classroom Management themes were notably smaller than the Positive Teacher Qualities theme; however, the subthemes that made up both of these themes were relatively consistent across all regions. Within Negative Interpersonal Interactions, both subthemes aligned with the conflict and dependency dimensions derived from attachment theory (Bowlby, Citation1969, Pianta, Citation2001). While all regions included items relating to teachers being perceived as unfair and behaving in a way that results in student anger and/or frustration, items relating to the extent to which students relied on their teachers for validation were only identified in European measures. Among many Western cultures, where autonomy and independence are highly valued, an adolescent’s dependency on their teacher may be perceived as maladaptive (Spilt & Koomen, Citation2022). Conversely, among collectivist cultures, which tend to value interdependence, and countries where there tend to be a greater power distance, there may be greater acceptance of a student’s dependency on their teacher, regardless of age (Hofstede, Citation1983, Markus & Kitayama, Citation1991, Spilt & Koomen, Citation2022). This may explain why items relating to this subtheme were not identified in Asian rating scales.

Similarly, items relating to Classroom Management, specifically how teachers prevent and respond to problem behaviors, were identified across all regions. Subthemes within this theme aligned with constructs derived from parenting style theory (i.e., control; Baumrind, Citation1967), Skinner and Belmont’s (Citation2010) model of motivation (i.e., structure), and interpersonal theory (i.e., agency; Horowitz & Strack, Citation2010; Wubbels & Brekelmans, Citation2005). In North American measures, additional items relating to the extent to which teachers are well-prepared and organized were included, whereas in Asian measures there were items relating to the extent to which teachers exhibited flexibility.

Although Instructional Methods was the second largest theme identified in the analysis, this construct was less commonly found in European measures and notably only one subtheme was common across all three regions. Across North American and Asian measures, instructional methods that are valued include setting high academic expectations, using various teaching strategies to ensure that students are learning and engaged, recognizing student achievement, and encouraging students to be independent thinkers. This theme seemed to highlight the importance of providing students with autonomy in learning, which is referenced in models of motivation (i.e., autonomy support; Skinner & Belmont, Citation1993). Although not all subthemes related directly to autonomy, there were a fair number of items relating to the importance of using of various strategies to keep students actively engaged in learning and encouraging students to achieve their highest academic potential. This suggests that although this is not strongly emphasized in theory, how teachers interact with students through the instructional methods they use can provide some insight into the quality of TSRs, particularly among cultures that tend to place greater value on achievement.

Positive Student Qualities was another theme that was unique to measures that were developed in Asia and North America, although how this theme was conceptualized differed. In Asia, the focus was on the extent to which teachers liked their students whereas in North American measures the items related to the extent to which teachers trusted their students. This theme considers the interpersonal qualities that students bring into the relationship and contribute to positive TSRs. This finding can, in part, be explained by the fact that these regions were more likely to include measures where the teacher was the informant. This theme also addresses the reciprocity that exists in TSRs (Pianta et al., Citation2003). Brinkworth et al. (Citation2018) define TSRs as “teachers’ and students’ aggregated and ongoing perceptions of one another, affect toward each other, and interactions over time” (p. 25) and argue for a more holistic measure of TSRs as it can improve our prediction of various student outcomes. While measuring students’ perceptions of social support from non-parental adults has been shown to predict skills needed for academic achievement (e.g., engagement and motivation), self-esteem, and behavioral and emotional problems (Sterrett et al., Citation2011). A teacher’s perception of a student has also been associated with student’s adjustment to school and can predict conflict in the TSR (Brinkworth et al., Citation2018, Mercer & DeRosier, Citation2010).

The final theme identified in this review was Classroom Climate, which was identified across all regions, with some variation. For instance, whereas Asian and European measures included items relating to a teacher’s ability to create friendly environments for students to interact and share their opinions, North American measures focused more on the extent to which students feel liked by their teachers and their peers.

Although there were many commonalities among these themes, the more robust themes seem to vary by region. These differences speak to the influence that local cultural context and norms have on the expectations of TSRs and the interpersonal qualities that are valued. For instance, in Northern and Western Europe, equality and homogeneity are highly valued, so teachers may try to minimize power between teachers and student by encouraging students to ask questions and challenge their teacher (Kirkebæk et al., Citation2013). This minimization of power difference may explain why items relating to teachers respecting their students’ opinions and ensuring that students feel comfortable around them were uniquely identified in European measures. However, in East Asia, where there tends to be a greater power distance, Confucian tradition, which distinguishes “affect-respect” and “ought-respect,” appears to have had some influence on expectations of TSRs (Li, Citation2012, Sun et al., Citation2017). Whereas affect-respect is described as an emotion, ought-respect is described as the respect that everyone deserves. The latter tends to be more common in Western countries, which might explain why this was identified in North American and European measures. East Asian learners, however, tend to experience deep, affect-respect for their teachers, viewing them as role models of virtuous qualities (e.g., providing help, caring, avoiding conflict) and they may expect their teachers to take the lead in classroom (Kirkebæk et al., Citation2013, Li, Citation2012). Finally, in collectivist cultures, there tends to be greater sensitivity to conflict in relationships; thus, individuals are often encouraged to avoid direct confrontation (Abu Rahmoun et al., Citation2021, Li, Citation2012). This cultural norm might explain why the ability to resolve or avoid conflict was identified in Asian measures and not in North American and European measures.

Limitations

First, the search criteria excluded measures that were not available in English or were adapted into another language from previously developed measures. Similarly, measures that were originally designed for younger ages but had been adapted for use in adolescence, were also excluded from the study. Second, regions where only one measure was identified were not included in the analysis. For example, because of this criterion, specific geographical regions across Africa, the Americas, Asia, Europe, among others, were not represented in this thematic analysis. Third, because the search was confined to identifying measures published in peer-reviewed journals or available through ProQuest Dissertations, gray literature and unpublished measures were not included in this review.

Finally, it is imperative to acknowledge that although the regions identified in this study were based on geographical location, cultures may vary significantly within these regions. Not all countries within these geographical regions, or within other regions, were represented in this analysis. Therefore, the subthemes that were identified in the thematic analysis should not be used to make broad generalizations of the culture and values of countries within these regions. Rather, perspectives across various cultures should be used to provide a rich conceptualization of what aspects of TSRs are relevant to the relationships that teachers and adolescents are creating.

Implications for research and practice

Because of the limitations identified in this study, recommendations for future research are made. First, it is likely that there are additional themes and subthemes that are relevant to adolescent TSRs that were not identified in the current review, which would add to our conceptualization of these relationships. Therefore, future researchers are encouraged to translate other measures of TSRs, when appropriate, and to conduct a comprehensive and representative thematic analysis with translated and adapted measures. Additionally, future researchers should consider organizing measures into more specific geographical regions (e.g., South Asia, East Asia, Central Asia, West Asia), when possible, to provide in-depth analysis on the similarities and differences that exists not only across, but within, regions.

Findings from the systematic review also have several implications for schools. First, because of the impact of TSRs on adolescent academic success and well-being, it important that school personnel consider the quality of these measures. Although the existing evidence-base for psychometrically sound measures of TSRs is limited, schools should consider selecting measures with the strongest evidence. When assessing the quality of TSRs, schools should also consider the extent to which the instrument measures constructs that are relevant to adolescent students (e.g., trusting and compassionate teachers, setting clear expectations, etc.).

Although there are structural barriers (e.g., rotating schedules, increased teacher-student ratio, competing priorities) to forming relationships with middle and high school students, teachers are strongly encouraged to form positive relationships with all their students. In addition, relationships are inherently personal and unique due to the qualities and lived experiences that adolescents bring into these relationships. Nevertheless, findings from this study can be used to inform teacher training programs, professional development, and consultation. For instance, it may be helpful to build teacher awareness across these six dimensions and the influence that each domain has on the development of TSRs. Additionally, strategies can be developed that align with each of the six dimensions to support teachers in developing positive relationships with adolescent students. Equipping teachers with various strategies will likely increase their capacity to develop positive and meaningful relationships with middle and high school students.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (35.2 KB)Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/21683603.2024.2328834.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Data availability statement

The datasets generated during and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Arabiye Artola Bonanno

Arabiye Artola Bonanno MHS is a doctoral student in the Department of Applied Psychology at Northeastern University and is pursuing her PhD in school psychology. She earned her master’s in health science degree in mental health from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, where she also received a certificate in adolescent health. Her research interests include teacher-student relationships in adolescence, adult social-emotional learning, and sense of school belonging.

Amy M. Briesch

Amy M. Briesch PhD is a Professor in the Department of Applied Psychology at Northeastern University. Her primary research interests involve the development of feasible and psychometrically sound measures for the assessment of student behavior in multi-tiered systems of support.

Karin Lifter

Karin Lifter PhD is a Professor in the Department of Applied Psychology at Northeastern University. She earned a PhD in developmental psychology from Columbia University, and she pursued a postdoctoral specialization in developmental disabilities from the University of Massachusetts – Amherst. Dr. Lifter conducts both descriptive and intervention studies on the play, language, and social development of young children with and without disabilities, bridging cognitive and behavioral theories.

Paige Kemerer

Paige Kemerer M.S. is a graduate student in the Department of Applied Psychology at Northeastern University and is pursuing her CAGS degree in school psychology. Her research interests involve teacher-student relationships and supporting student well-being and learning.

References

- Abu Rahmoun, N., Goldberg, T., & Orland-Barak, L. (2021). Teacher evaluation policy in Arab-Israeli schools through the lens of micropolitics: Implications for teacher education. European Journal of Teacher Education, 44(3), 348–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2021.1947238

- *Aldhafri, S., & Alhadabi, A. (2019). The psychometric properties of the student–Teacher relationship measure for Omani grade 7–11 students. Frontiers in Psychology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02283

- *Ang, R. P. (2005). Development and validation of the Teacher-student relationship inventory using exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. The Journal of Experimental Education, 74(1), 55–74. https://doi.org/10.3200/JEXE.74.1.55-74

- *Ang, R. P., Ong, S. L., & Li, X. (2020). Student version of the Teacher–student relationship inventory (S-TSRI): Development, validation and invariance. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01724

- Baumrind, D. (1967). Child care practices anteceding three patterns of preschool behavior. Genetic Psychology Monographs, 75(1), 43–88.

- *Berman-Young, S. B. (2014). (2022), December 19 Teacher-Student Relationships: Examining Student Perceptions of Teacher Support and Positive Student Outcomes [ *, University of Minnesota]. http://www.proquest.com/docview/1614471854/abstract/BD8102B453934AB0PQ/1

- Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment: Vol. I. Basic Books.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- *Brinkworth, M. E., McIntyre, J., Juraschek, A. D., & Gehlbach, H. (2018). Teacher-student relationships: The positives and negatives of assessing both perspectives. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 55, 24–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2017.09.002

- *Cipriano, C., Barnes, T. N., Kolev, L., Rivers, S., & Brackett, M. (2019). Validating the emotion-focused interactions scale for teacher–student interactions. Learning Environments Research, 22(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-018-9264-2

- Crosnoe, R., Johnson, M. K., & Elder, G. H. (2004). Intergenerational bonding in school: The behavioral and contextual correlates of student-teacher relationships. Sociology of Education, 77(1), 60–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/003804070407700103

- *De Bruyn, E. H. (2004). Development of the mentor behaviour rating scale. School Psychology International, 25(2), 185–192. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034304043686

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Springer.

- Eccles, J. S., Lord, S. E., & Roeser, R. W. (1996). Round holes, square pegs, rocky roads, and sore feet: The impact of stage–environment fit on young adolescents’ experiences in schools and families. In D. Cicchetti & S. L. Toth (eds.), Adolescence: Opportunities and challenges (pp. 47–92). University of Rochester Press.

- *Freese, S. F. (1999). The relationship between teacher caring and student engagement in academic high school classes [ Ed.D., Hofstra University]. http://www.proquest.com/docview/304505672/abstract/17EF946279B14F9EPQ/1

- *García-Moya, I., Brooks, F., & Moreno, C. (2021). A new measure for the assessment of student–teacher connectedness in adolescence. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 37(5), 357–367. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000621

- Gutman, L. M., & Eccles, J. S. (2007). Stage-environment fit during adolescence: Trajectories of family relations and adolescent outcomes. Developmental Psychology, 43(2), 522–537. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.43.2.522

- Harrison, L. J., Clarke, L., & Ungerer, J. A. (2007). Children’s drawings provide a new perspective on teacher-child relationship quality and school adjustment. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 22(1), 55–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2006.10.003

- *Havik, T., & Westergård, E. (2020). Do teachers matter? Students’ perceptions of classroom interactions and student engagement. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 64(4), 488–507. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2019.1577754

- Hofstede, G. (1983). National cultures in four dimensions: A research-based theory of cultural differences among nations. International Studies of Management and Organization, 13(1/2), 46–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/00208825.1983.11656358

- Horowitz, L. M., & Strack, S. (2010). Handbook of interpersonal psychology: Theory, research, assessment, and therapeutic interventions. John Wiley & Sons.

- House, J. S. (1981). Work stress and social support. Addison-Wesley.

- Kirkebæk, M. J., Du, X., & Jensen, A. A. (2013). Teaching and learning culture: Negotiating the context. BRILL. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/northeastern-ebooks/detail.action?docID=3034903

- *Koomen, H. M. Y., & Jellesma, F. C. (2015). Can closeness, conflict, and dependency be used to characterize students’ perceptions of the affective relationship with their teacher? Testing a new child measure in middle childhood. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 85(4), 479–497. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12094

- Li, J. (2012). Cultural foundations of learning East and West. Cambridge University Pres.

- *Liu, P. P., Savitz-Romer, M., Perella, J., Hill, N. E., & Liang, B. (2018). Student representations of dyadic and global teacher-student relationships: Perceived caring, negativity, affinity, and differences across gender and race/ethnicity. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 54, 281–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2018.07.005

- Malecki, C. K., & Demaray, M. K. (2003). What type of support do they need? investigating student adjustment as related to emotional, informational, appraisal, and instrumental support. School Psychology Quarterly, 18(3), 231–252. https://doi.org/10.1521/scpq.18.3.231.22576

- Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98(2), 224–253. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224

- McGrath, K. F., & Van Bergen, P. (2015). Who, when, why and to what end? Students at risk of negative student–teacher relationships and their outcomes. Educational Research Review, 14, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2014.12.001

- Mercer, S. H., & DeRosier, M. E. (2010). A prospective investigation of teacher preference and children’s perceptions of the student–teacher relationship. Psychology in the Schools, 47(2), 184–192. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20463

- *Pham, Y. K., Murray, C., & Gau, J. (2022). The inventory of teacher-student relationships: Factor structure and associations with school engagement among high-risk youth. Psychology in the Schools, 59(2), 413–429. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22617

- Phillipo, K., Conner, J. O., Davidson, S., & Pope, D. (2017). A systematic review of student self-report instruments that assess student-teacher relationships. Teachers College Record, 119(9).

- Pianta, R. C. (2001). STRS student-teacher relationship scale: Professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources.

- Pianta, R. C., Hamre, B., & Stuhlman, M. (2003). Relationships between teachers and children. Handbook of Psychology, 7(1–7), 199–234. https://doi.org/10.1002/0471264385.wei0710

- Pianta, R. C., La Paro, K. M., & Hamre, B. K. (2008). Classroom assessment scoring SystemTM: Manual K-3. Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.

- *Pössel, P., Rudasill, K. M., Adelson, J. L., Bjerg, A. C., Wooldridge, D. T., & Black, S. W. (2013). Teaching behavior and well-being in students: Development and concurrent validity of an instrument to measure student-reported teaching behavior. International Journal of Emotional Education, 5(2), 5–30.

- Reddy, R., Rhodes, J. E., & Mulhall, P. (2003). The influence of teacher support on student adjustment in the middle school years: A latent growth curve study. Development and Psychopathology, 15(1), 119–138. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579403000075

- Roorda, D. L., Koomen, H. M. Y., Spilt, J. L., & Oort, F. J. (2011). The influence of affective teacher–student relationships on students’ school engagement and achievement: A meta-analytic approach. Review of Educational Research, 81(4), 493–529. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654311421793

- Roorda, D. L., Zee, M., & Koomen, H. M. Y. (2021). Don’t forget student-teacher dependency! A meta-analysis on associations with students’ school adjustment and the moderating role of student and teacher characteristics. Attachment & Human Development, 23(5), 490–503. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2020.1751987

- *She, H.-C., & Fisher, D. (2000). The development of a questionnaire to describe science teacher communication behavior in Taiwan and Australia. Science Education, 84(6), 706–726. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-237X(200011)84:6<706:AID-SCE2>3.0.CO;2-W

- Skinner, E. A., & Belmont, M. J. (1993). Motivation in the classroom: Reciprocal effects of teacher behavior and student engagement across the school year. Journal of Educational Psychology, 85(4), 571–581. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.85.4.571

- *Soh, K.-C. (2000). Indexing creativity fostering Teacher behavior: A preliminary validation study. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 34(2), 118–134. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2162-6057.2000.tb01205.x

- Spilt, J. L., & Koomen, H. M. Y. (2022). Three decades of research on individual teacher-child relationships: A chronological review of prominent attachment-based themes. Frontiers in Education, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.920985

- Spilt, J. L., Koomen, H. M. Y., & Thijs, J. T. (2011). Teacher wellbeing: The importance of teacher–student relationships. Educational Psychology Review, 23(4), 457–477. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-011-9170-y

- Sterrett, E. M., Jones, D. J., McKee, L. G., & Kincaid, C. (2011). Supportive non-parental adults and adolescent psychosocial functioning: Using social support as a theoretical framework. American Journal of Community Psychology, 48(3–4), 284–295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-011-9429-y

- *Sun, B., Shao, Y., Richardson, M. J., Weng, Y., & Shen, J. (2017). The caring behaviour of primary and middle school teachers in China: Features and structure. Educational Psychology, 37(3), 362–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2016.1214688

- *Tan, Y. J., Quek, C. L. G., & Fulmer, G. (2019). Validation of classroom Teacher interaction skills scale. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 28(5), 429–446. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-019-00444-6

- Taxer, J. L., Becker-Kurz, B., & Frenzel, A. C. (2019). Do quality teacher–student relationships protect teachers from emotional exhaustion? The mediating role of enjoyment and anger. Social Psychology of Education, 22(1), 209–226. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-018-9468-4

- *Trahan, M. N. (2013). A conceptual and measurement model of student-Teacher classroom social capital: an exploration of relationships [ D.Ed., University of Louisiana at Lafayette]. In ProQuest Dissertations and Theses. http://www.proquest.com/docview/1524019270/abstract/AAC8CA9994174F6BPQ/1

- *Veldman, I., Admiraal, W., Mainhard, T., Wubbels, T., & van Tartwijk, J. (2017). Measuring teachers’ interpersonal self-efficacy: Relationship with realized interpersonal aspirations, classroom management efficacy and age. Social Psychology of Education, 20(2), 411–426. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-017-9374-1

- Walker, J. M. T. (2009). Authoritative classroom management: How control and nurturance work together. Theory into Practice, 48(2), 122–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405840902776392

- Wang, M.-T., Brinkworth, M., & Eccles, J. (2013). Moderating effects of teacher–student relationship in adolescent trajectories of emotional and behavioral adjustment. Developmental Psychology, 49(4), 690–705. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027916

- *Wilkins, J. (2007). An examination of the student and teacher behaviors that contribute to good student-teacher relationships in large urban high schools [ Ph.D., State University of New York at Buffalo]. http://www.proquest.com/docview/304944893/abstract/CEA03082DF3648CBPQ/1

- Wubbels, T., & Brekelmans, M. (2005). Two decades of research on teacher–student relationships in class. International Journal of Educational Research, 43(1), 6–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2006.03.003

- Zandvliet, Z., den Brok, P., Mainhard, T., & van Tartwijk, J. (2014). Interpersonal relationships in education: From theory to practice. Sense Publishers. https://link-springer-com.ezproxy.neu.edu/book/10.1007%2F978-94-6209-701-8

- *Zelyurt, H., & Koksalan, B. (2020). Development of the perceived middle school Teacher behavior scale. Educational Policy Analysis and Strategic Research, 15(1), 163–177. https://doi.org/10.29329/epasr.2020.236.9

- Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., Chipuer, H. M., Hanisch, M., Creed, P. A., & McGregor, L. (2006). Relationships at school and stage-environment fit as resources for adolescent engagement and achievement. Journal of Adolescence, 29(6), 911–933. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.04.008