Abstract

The development of novel adsorbents for water treatment has become a significant branch of materials science and environmental engineering, with annual research output growing exponentially. New adsorbents, however, are typically not developed beyond the laboratory scale, creating a discrepancy between research volume and commercial adoption. This study analyzes the development of adsorbents using a productization framework. Three types of companies (adsorbent manufacturers/dealers, consultants/process designers, and treatment plant operators) were interviewed to understand the challenges for up-scaling and ultimately commercializing new adsorbents, and the requirements for treatment processes and the expectations of customers (adsorbent users), adsorbent producers, and service providers were determined. A framework for developing optimal business models, strategies, and approaches for productizing adsorbents was also created. The main challenges for commercializing adsorbents include their properties (such as quality, availability, lifespan, and adaptability), profitability issues (regeneration, disposal, and logistics cost), and activities related to environmental legislation, testing, and verification.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

Adsorption is a fundamental surface chemistry phenomenon in which dissolved substances adhere to the interface of condensed and liquid or gaseous phases due to surface forces. In water treatment, adsorption using activated carbon has been employed for over 100 years to remove odor- and taste-causing natural organic matter from drinking water (Worch, Citation2021). Other important uses of adsorption processes in water treatment include removing certain potentially toxic naturally occurring elements from groundwater (such as arsenic or fluoride), water softening, and producing ultrapure water for industrial applications (Clifford, Citation1990; Sylvester, Citation2015). The demand for water and wastewater treatment is increasing due to growth in world population, changes in the dynamics of the global water cycle due to climate change, and pollution of water resources.

Adsorption technology, in general, should carry a very attractive value proposition for water treatment plants, as its frequently mentioned benefits include good treatment performance, low costs, simple operation, robustness against changes in physicochemical conditions or influent water quality, and the possibility to recover the removed substances (Babel & Kurniawan, Citation2003). Nevertheless, only a handful of adsorbent materials other than activated carbon are widely used on an industrial scale, namely zeolites, activated alumina, and synthetic ion-exchange resins. At the same time, using the number of annual scientific journal publications as a measure, it can be observed that the research activities related to the development of new adsorbent materials are increasing exponentially (over 5000 papers were published in 2021 and have been indexed in the Scopus database). Thus, there is a striking discrepancy between the research volume and commercial adoption of adsorbent materials.

The introduction of new materials and technologies is occurring faster than ever, and their development is typically technology-driven. This has resulted in the associated businesses and commercialization receiving less attention (Paulin et al., Citation2012). From a business perspective, den Ouden (Citation2006) reports that, in principle, the viability of the business model of every product development project should be evaluated to determine whether there is a requirement for a new business model or existing ones can be used (Kinnunen et al., Citation2014). Regardless of whether the business model changes, the most important aspect is to analyze the requirements of the operative business processes (Simula et al., Citation2008; Suikki et al., Citation2006). Product design and business model strategies are also vitally important in the sustainability and circularity transition (Bocken et al., Citation2016).

Productization integrates customer needs and requirements into the product by combining its commercial and technical elements to make it commercially viable (Härkonen et al., Citation2015). Commercialization is that stage in the development process of a new product that involves its introduction to the market (i.e. profit-making position; Simula et al., Citation2008; Suominen et al., Citation2009). Commercialization is a multi-stage process (beginning with research and concluding with marketing) that entails introducing a product, service, or technology offering from the point of innovation or conceptualization to the market for commercial success. Acknowledging the various factors that contribute to success in various industries and tackling the numerous obstacles that businesses encounter at all phases of the development process (from ideation to accomplishment), can help commercialization be more successful (Spilling, Citation2004). In the current highly competitive business world, the success of a company relies on its ability to commercialize its products or services and, thereby, gain financial and strategic advantages (Pellikka & Malinen, Citation2014).

Productization enhances the commercial feasibility, competitiveness, and delivery efficacy of the offering by making it more distinct and practical, whereas commercialization identifies the customer value, develops capabilities that fulfil the needs of the customer, builds the market, and offers the product to the targeted customers with a price that is based on the quality of the offering (Kuula et al., Citation2018; Payne et al., Citation2008). Both processes aspire to be profitable, but there is a significant distinction between them. While productization clarifies the offering (service, product, or innovation) for commercialization, the goal of commercialization is to enter the market and achieve competitive advantage.

An appropriate business model is essential for successfully commercializing and fully comprehending the commercial viability of a novel product, service, or technology (Corkindale, Citation2010; Pellikka & Malinen, Citation2014). Business models represent the underlying logic operations of a company through a standardized framework of objects, processes, and interactions (Osterwalder et al., Citation2005). Understanding the customers’ demands, decision making, and organization to meet their needs while maximizing revenue and profit are all elements of a business model (Osterwalder et al., Citation2005; Teece, Citation2010). Hence, a well-designed business model that guarantees the coordination of business strategy and procedures is crucial for the continued existence and success of a commercial organization (Al-Debi et al., Citation2008).

Material development is usually fostered with a ‘technology push’, which is also the case with materials related to water treatment. In the business-to-business market, it might be more challenging to achieve a full ‘market pull’; however, it is evidently critical for the success of a business that the stakeholders, requirements, and potential of the operative business processes be analyzed during the technology development phase. Therefore, this study aims to establish a method for the commercialization of the adsorbent materials used in water treatment through a business model and productization approach. It addresses the following research questions: (1) What type of framework should be used for productizing the adsorbent materials for water treatment? (2) What opportunities and challenges are associated with the adsorbent materials productization? (3) How can the commercialization be advanced through productization?

The first objective is to develop a framework for productizing the adsorbent materials utilized for water and wastewater treatment based on literature, while the second objective is to examine the existing productization concepts and business strategies employed by the case companies (i.e. adsorbent manufacturers/dealers, consultants/process designers, and treatment plant operators) included in this study. Building a descriptive framework for business model and productization is the third objective, which will help make novel adsorbent materials more commercially viable.

2. Literature review

2.1. Business model

A business model is the plan that a company follows to generate revenue and profit from its operations by answering four primary questions: (1) Who are the customers of the company? (2) What does the company provide for sale? (3) How are the products produced? (4) How does the company generate revenue? (Osterwalder et al., Citation2005; Teece, Citation2010). The term business model is widely used, but in order to get the benefits from it companies must define what the business model concept means for them and how they utilize it in their strategies (Magretta, Citation2002). According to Lambert (Citation2008), a conceptual framework provides business model concepts with a structure for growth by enabling a discussion of the areas of mutual understanding and possible disagreement and suggests connection points as future focus areas.

Suikki et al. (Citation2006) introduced two frameworks: the first one is utilized to define and create business models and the second one is used for business concept analysis. The elements of the model are divided into the following groups: value creation, offering, and revenue model. With regard to the offering category, a company should identify its clients, analyze its deliverables to them, and specify how its sales will generate capital for the business. Regarding value creation, the participants, investors, suppliers, and buyers should be defined in relation to the main offering. The revenue model, in turn, depicts the pricing, profit channels, market data, and the value that the network creates (Osterwalder & Pigneur, Citation2010; Suikki et al., Citation2006). The aforementioned framework is described in .

Table 1. Framework for business model (modified from Suikki et al. [Citation2006]).

The comprehensive business model framework presented by Lambert (Citation2008) focus on value-adding processes, resource availability, offerings, and value propositions. The framework provides a structure for the business model concept utilization. According to Osterwalder and Pigneur (Citation2010), a business model can be characterized through nine key elements (key activities, key resources, key partners, value propositions, customer segments, customer relationship, channels, cost structure, and revenue streams) that demonstrate the logic of how a company aims to generate revenue and profit. Teece (Citation2010) argues that to be successful, a business model must be more than just a good, realistic plan for running a company. Rather, it must meet the customers’ unique requirements.

Adsorbent firms provide a new technology that cannot dominate markets without effective business models. To construct business models, it is necessary to define the products and services that will be offered, how those goods and services will be produced and delivered, and how the value will be commercialized (Budzianowski & Brodacka, Citation2017). The shift toward minimum operational costs and profit maximization is a significant component of the business model approach (Rao et al., Citation2015). It is important to identify the key commercial actors involved in developing, delivering, and commercializing the products and services related to environmental treatment products and to create sustainable business model (Daou et al., Citation2020).

2.2. Productization

Härkonen et al. (Citation2015) defined productization as ‘the process of analyzing the need, defining and combining appropriate tangible and intangible elements into a product-like object that is standardized, repeatable, and understandable’. The productization process is generally linked to the concept of product structure (commercial and technical perspective), which refers to planning or organizing a system for a product (Härkonen et al., Citation2015; Simula et al., Citation2008; Suominen et al., Citation2009). According to Kropsu-Vehkapera and Haapasalo (Citation2011), the product structure is a model that can standardize how a product is understood, what information is linked to or conveyed by it, and how its elements are interrelated.

According to Suominen et al. (Citation2009), quality, value creation, market orientation, and customer demand should be prioritized at every stage of the productization process. This begins with the brainstorming phase of the development process for a new product and continues till commercialization. Productization process involves carefully designed and well-organized stages to decrease the time used for product marketing and sales activities, identifying customer needs, and creating profitable strategy to satisfy the customer needs (Jaakkola, Citation2011).

Creating unique offerings in a competitive market, performing market research, and renewing and improving offerings to address the changes in customer needs are the major benefits of productization (Simula et al., Citation2008). Companies are constantly increasing the number of products they offer (Mustonen, Citation2020), resulting in a lack of thinking skills with respect to their product portfolio, reduced focus on the development of new products, and challenges regarding regular portfolio renewal during productization activities (Tolonen et al., Citation2014). At the beginning of productization, the product structure concept is utilized to conduct analysis of products (offering) from both commercial and technical perspectives (Mustonen et al., Citation2019; Tolonen et al., Citation2014). The commercial side of the product structure categorizes products into product families and configurations that are sold to the customers. The features and functions that can change based on customer needs should be viewed as different items (Mustonen et al., Citation2019). The most notable differences in productizing physical products and services are seen in the technical product portfolio. The physical product’s technical structure includes components, subassemblies, and assemblies. For services, the technical structure includes service tasks, subprocesses and processes (Mustonen et al., Citation2019).

2.3. Commercialization

Commercialization is a process that begins with identifying the customer and market needs and concludes with providing a product with sustainable economic features that is competitive in the market (Spilling, Citation2004). To introduce a product to market, the commercialization team must first recognize, analyze, implement, and sustain the relevant technological know-how (Al Natsheh et al., Citation2015). Therefore, it is important to properly plan, manage, resource, and network throughout the commercialization process. In the rush to meet the customer demand, product developers often fail to take technological advances into account. To bridge the gap between technology and market transfer, Kim et al. (Citation2019) designed a three-stage technology-product-market model outlining the technology development, product development, and marketing phases of the technology commercialization process. For product, service, or technology to be commercialized successfully, a market-oriented (market involvement throughout the development) process must be followed in order to increase product performance in relation to pricing and specifically target customers.

Kirkegaard Sløk-Madsen et al. (Citation2017) propose a typology of commercialization defined by two aspects: a continuous improvement approach derived from innovative business purpose and how opportunities are evaluated. The presented typology shows commercialization on a range from research to utilization in relation to the entrepreneurial motivation that prompts strategic activity, while the opportunity is seen as existing on a concept from being discovered to being delivered. Similarly, Gbadegeshin (Citation2018) presented a lean commercialization framework to aid technology entrepreneurs and technology-based firms in commercializing new technology through the transformation of innovative knowledge and resources into the products or services.

While numerous challenges must be addressed, many companies view the commercialization phase as their first real chance to establish the strategy and market position of the company. According to Pellikka and Malinen (Citation2014) the major challenges in commercialization include establishing a connection between new technologies and market opportunities, defining technologies to the users, implementing technologies, securing sufficient resources for effective demonstrations, gaining commercial success, and choosing the most innovative business strategies. Al Natsheh et al. (Citation2015) state that the most regular barriers to the commercialization of any technology are originality and apparent valuation, product or services performance characteristics, certification requirements or recognition, the appropriate strategy, sufficient budget allocation, a strong business roadmap, and a well-thought-out manufacturing and maintenance strategy. While these barriers are specific to the commercialization of technology, the aforementioned difficulties impact the market introduction of any new product or service.

2.4. Productization framework for adsorbent materials

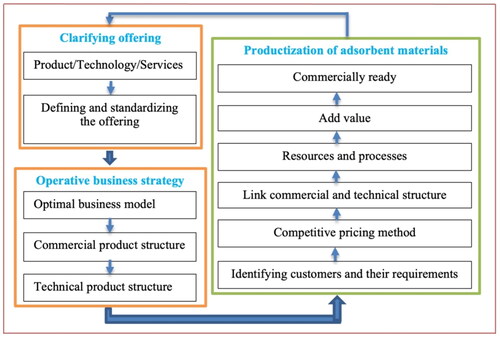

Based on the above theoretical discussion, the water treatment-related adsorbent materials productization framework is proposed, which is illustrated in .

The framework includes two main areas: offering clarification and formulating a business strategy as a foundation to productize the adsorbent materials. The figure illustrates the interrelationship between the development process for the product or service of the company and the business strategy for its productization. Productization aims to integrate the offering (service or product) into a format that simplifies the conveyance of its contents to the targeted customers.

The first phase is the offering definition. There are two options – a product (adsorbent materials) and a service. This definition helps in more precisely define and standardize the offering. It also helps companies communicate and convince the customers of performance of novel offerings. In the second phase, the aim is to fit the offering into the company’s strategy. An optimal business model, and a technical and commercial product structure are developed based on the resources, strengths, and processes of the company. The productization covers the identified customers and their requirements, resources, process, as well as cost drivers. Thanks to this integration, value is added to the offering and the commercialization readiness is improved. In line with Al Natsheh et al. (Citation2014), we can conclude that the business model is a part of both the productization and commercialization processes.

3. Methodology

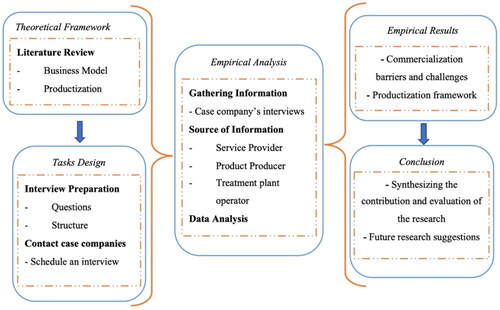

This study used a qualitative approach, and the research process is shown in . The research began with developing a theoretical framework based on a thorough literature assessment of the business model and productization concepts. The empirical part of the research was then conducted by interviewing the employees of the companies included in this study. A more thorough understanding of the commercialization and productization activities of the adsorbent materials used for water and wastewater treatment was gained through the interviews. The research questions were addressed after the data was analyzed following the interviews.

The topics discussed in the literature review defined the structure of the interview questions, which are presented in . The interviewees were briefed on the topic and purpose of the study and were sent a structured questionnaire via email before the interview. Participant anonymity and consent guidelines were followed during the interviews and the data processing.

Table 2. Interview questionnaire structure.

The primary sources of information for this research were (1) companies operating in water and wastewater treatment consultancy and process design, (2) those that produce or distribute adsorbent materials, and (3) those that operate water or wastewater treatment plants. Individuals from seven companies took part in the interviews, as shown in . All the companies were based in Finland. These companies were chosen because of their knowledge and their roles (consultancy and process design, production and distribution of adsorbents, and water and wastewater treatment) in the value chain. The chosen companies were also receptive and willing to engage in the study, which ensured gaining rich empirical data for the analysis.

Table 3. Case companies and interviewees.

A qualitative content analysis method was utilized in the data analysis. The data was first extracted from the recorded interviews and transcribed into the text. The transcripts were read several times to identify the emerging themes and concepts. The theoretical framework was also utilized to analyze the results, discuss the findings, and create the conclusions.

4. Results

4.1. Adsorbent material considerations for commercialization

Five key factors were identified in relation to the challenges and opportunities associated with commercializing the adsorbent materials that are used in water and wastewater treatment during the interviews. These are described in the following subsections.

4.1.1. Legislation and standards

The development of adsorbent materials should reflect the various applicable laws and other requirements (such as the standards or recommendations provided by national or international organizations). Legal requirements are mandatory; thus, an adsorbent cannot be used unless it complies with the regulations. Often, the raw materials utilized for adsorbents are classified as by-products or waste. The European Waste Framework Directive 2008/98/EC defines waste as ‘any substance or object which the holder discards or intends or is required to discard’ and a by-product as ‘a substance or object, resulting from a production process, the primary aim of which is not the production of that item’ (European Union, Citation2008). In the case of raw materials classified as waste, the end-of-waste protocol must be implemented before their utilization. The end-of-waste criteria specify the requirements that a material stream must meet to exit the definition as waste to minimize the adverse effects on human health and the environment (Villanueva et al., Citation2010). Recyclable materials should be considered waste according to the end-of-waste criteria only if regulatory measures under waste laws are necessary to ensure the safety of the environment and the public (Villanueva & Eder, Citation2014).

According to an interviewee from a manufacturing company (company D), the possibilities of using adsorbent materials effectively might be negatively affected because of the rigid legal restrictions and standards. For instance, some adsorbents may require evaluation under REACH (Registration, Evaluation, Authorization, and Restriction of Chemicals) according to European Regulation EC 1907/2006 (European Union, Citation2006), which could lead to significant additional costs. The aim of the REACH legislation is to reduce the risks to human health and the environment from chemicals and enhance the competitiveness of European chemical producers. The legislation requires the registration of all chemicals produced in or transported into the region (Petry et al., Citation2006; Williams et al., Citation2009). However, some materials, such as polymer adsorbents, are exempt from REACH, while monomer raw materials may still require registration if they have not been evaluated before. If the REACH legislation is to be followed, the procedure is costly for adsorbent manufacturers, and most end users are reluctant to bear the associated expenses. While the legal measures may increase competitiveness in the long term, they may also delay adsorbent commercialization.

4.1.2. Treatment costs

The initial research and development (R&D), testing of adsorbents, the operation and maintenance involved in the water treatment process, and the regeneration or disposal of used adsorbents are costs driver in the adsorbent industry. Adsorbent manufacturers must estimate the combined costs. These include raw material costs, production costs, shipping and handling costs, and so forth. Each water quality issue requires a unique assessment to select the optimum treatment process, which affects operating expenses and selling costs. Further, customers seek the lowest prices, which often leads to them using established materials, mainly activated carbon, instead of novel adsorbents.

4.1.3. Water quality

Degradation of water quality cannot be risked, as this would severely impact productivity and result in enormous losses in industrial plants that utilize the treated water. On the other hand, operators of municipal water and wastewater treatment plants must take extra precautions to ensure the safety of the public and the environment. Therefore, the operators expect all adsorbent materials to be verified, cost-effective, thoroughly tested, and have a previous track record of successful use.

4.1.4. Relationships with customers

Customers of the adsorbent material producers and service providers include companies that operate water or wastewater treatment plants. These include, for example, paper, chemical, and mining companies, as well as municipalities. The products and services are provided on a demand basis. Customers who experience water-related problems contact the manufacturers or service providers for consultation. In addition, the customers are frequently informed by the adsorbent producers or service providers during site visits of any additional aspects of water treatment that might need improvement. Further, if customers agree and give permission, the upgrading of the existing treatment process or the planning of new ones begins.

The customers typically have no desire to try out novel adsorbent materials with a short or non-existent track record. Generally, the adsorbent producers or service suppliers already have enough customers without advertising, who have established long-term relationships with them and have no interest in repeating their testing and piloting processes with novel materials. This demonstrates that buyers are reluctant to switch from one adsorbent provider to another or from one product to another. Furthermore, water or wastewater treatment is not usually the main business for industrial companies, which may lead to them dedicating minimum resources to that function.

4.1.5. Variation in customer requirements

The requirements of customers vary in different markets and customer segments, as well for different functionalities and applications. Municipal and industrial water or wastewater treatment plants mostly prefer activated carbon, as it can meet many of the conventional treatment requirements. One interviewee, a treatment plant operator (company F), remarked, ‘We are not keen on adopting novel adsorbent materials. We are constantly relying on the known and proven ones—basically previously used products’. This indicates that companies that have responsibility of providing safe drinking water are averse to experimenting with new technologies and products. Industrial effluents, in turn, may contain various recalcitrant pollutants that must be removed from the effluent discharged, and, therefore, industrial plant operators may be more open to new adsorbents that are more affordable. This is especially the case if those contaminants are controlled in the water quality limits set by the environmental permit of the plant. Overall, wastewater treatment plants are more likely to adopt new adsorbent materials than plants that produce drinking or process water.

4.2. Expectations, opportunities, and challenges

4.2.1. Expectations of customers from adsorbent producers or service providers

One of the most important aspects for customers is the assurance that the product or service meets all the necessary standards. The obligation to comply with all the applicable laws and regulations should be fulfilled by the producers or material providers. Regenerating novel adsorbent materials is the provider’s responsibility. If the material cannot be reused, the provider should provide a disposal plan. This implies that customers expect a detailed product lifecycle strategy in advance.

New materials should be cost-effective, have superior performance in comparison to alternative processes, and include clear information with regard to labor-intensive operations and maintenance. An interviewee from the treatment plant operator sector (company G) stated that more effort should be put into advertising both new and old adsorbent materials because the company experienced difficulties with finding suppliers for activated carbon when upgrading its water treatment plant. In addition, the handling of logistics by the adsorbent provider (i.e. transportation of the new and end-of-life adsorbents) is a significant expectation from customers. Customers in the adsorbent materials market expect a transparent business model that details products’ technical performance, lifespan, and price.

4.2.2. The expectations of adsorbent producers or service providers from customers

Advertisement of adsorbent materials based on actual application data is normally not possible due to confidentiality reasons. Hence, treatment plant operators must contact the producer or service provider to obtain product information. Environmental legislation and logistics are considered the primary areas that generate extra costs, and, thus, the issue of whether the adsorbent provider or the end user pays or whether the payment is shared between the two should be clearly defined.

4.2.3. Productization opportunities and challenges

The analysis of the case companies showed that novel adsorption materials should be acceptable from economic, environmental, and social perspectives, and they need to be tested and proven in practice. Water and wastewater treatment plants are reluctant to become the first to adopt a novel adsorbent unless the producers or suppliers can convincing illustrate its technical efficiency, life span, regeneration, disposal, availability, and cost information. It was observed that the lack of information from manufacturers or providers, the consumer need for references, and a proven history of the adsorbent materials significantly affect commercialization. A comprehensive grasp of productization and viable business strategies is required to introduce new products or services to the market successfully.

Productization as a concept was unfamiliar to the companies included in the study; they were concerned that incorporating productization could impede their manufacturing processes and require more time and effort. However, according to the literature review, productization activities necessitate a skilled workforce for engineering and managing product requirements and customer expectations. The adsorbent products and services are described on their websites, which show the names of the adsorbent materials manufactured by that company and the services it offers (i.e. testing, piloting, operation and maintenance, and water treatment planning). No information is provided on the websites regarding who has bought which product in the past and how effectively it addressed their water problems. There is a lack of practical information on the adsorbents through which the treatment plant operators and designers can deeply comprehend the commercial structures of the products and services.

Productization is almost non-existent in terms of the product structure concept and strategic planning, process improvement, business model, and ownership of the products or services. The companies included in the study face challenges regarding how their products or services can be productized. Every company follows a similar process (i.e. water treatment problem analysis, research to find the most appropriate solution, piloting, testing, designing, and consulting). This demonstrates that it is not often clear which components should be seen as commercial and which ones should be classified as technical. The product structure concepts are used in manufacturing companies, but the common challenge is that the structures are not connected. The studied adsorbent materials user company (company F) assumes the producer or service provider to clearly productize their offerings in an easy-to-understand manner to promote novel adsorbent materials. Productization is viewed as marketing, so companies disregard it because they believe marketing or promoting adsorbent materials is unnecessary.

The productization of adsorbent materials presents several prospects that offer up exciting new possibilities for business. Productization:

Provides the pricing structure, specification, and product systemization. A uniform product description can be used for cost and performance projections.

Joins the product’s technical and commercial structures to enable improved capabilities to deliver products, services, and primary applications. The concept can be used to meet the customers’ needs better.

Enables buyers to obtain the necessary information (e.g. technical performance, lifecycle, and costs) via a pictorial illustration of the commercial structure.

Demonstrates the product creation processes, cost factors, management of time, and use of resources.

Provides an outlook of sales and customer requirements and how they are connected to resources and manufacturing processes. This helps production planning.

Promotes the market introduction of products through tasks that are needed on top of product design and production to increase the value for customers.

Forms basis for standard operations, productivity enhancement, and tangibility increase.

Adsorbent materials have promising productization potential. However, there are several challenges to overcome for further commercialization.

Users (especially drinking or process water providers) are reluctant to switch away from traditional adsorbent materials, such as activated carbon, because of their long-time use.

Productization was found to be a new concept among the interviewees, and they feared that the use of productization would cause more work and hamper manufacturing processes.

In many cases, adsorbent materials (and the related services) are manufactured and delivered according to customer demand and not according to a standardized structure.

The requirements of the customers vary which causes the commercial and technical structures to differ. Thus, it becomes difficult to generalize the adsorbent product (i.e. the material and related services).

The water treatment costs vary significantly and increase as more advanced treatment processes are adopted. However, end users are rarely willing to pay more. Besides additional costs, the cost of productization is also a concern.

4.3. Productization of adsorbent materials

4.3.1. Business model framework

The interviews revealed that customers were unwilling to use new products due to a lack of information about such products and a proper business plan. Thus, a new business model framework based on the literature review and interviews has been recommended (). The framework helps the company describe the offering (configuration, customer, and sales approach), the system for creating value (identify value-adding activities and customers), and revenue model (costs, pricing, and market size). Furthermore, the framework enables the evaluation of business models. In the adsorbent materials domain, the framework evaluation parameters assess the business model elements that fulfill the requirements of water and wastewater treatment and the customers’ wishes.

Table 4. Business model framework in the adsorbent materials domain.

This framework has been used to describe the reference business model (). The following questions are answered:

Table 5. Adsorbent materials for water and wastewater treatment business model.

How can customers learn about the product and purchase it?

What type of common requirements do the customers have?

How are the product sales, distribution, and invoicing managed?

What type of cost structures are needed for production and generating profit?

What is the market that is served? How large is the market?

The R&D of novel adsorbents is increasing rapidly, and, thus, it is possible that significantly improved materials are introduced. illustrates a reference business model that can be used in the adsorbent materials market.

4.3.2. Framework for productization

Since most of the adsorbent materials manufactured by the studied companies are produced upon customer request, the results of the present research indicate that heeding to customer needs should be prioritized. Thus, the practical information required by the customers about the adsorbent materials should be available from the commercial structure of the product. While the technical approaches of companies change in response to customer needs, a consistent description technique should be developed to thoroughly comprehend the associated research, planning, testing, and resource allocation. Therefore, product development, production, service operations, and cost-driving factors should all be included in the technical components to estimate the development time, resource allocation, and internal process management for the adsorbent materials. The prominent resources for adsorbent development include the equipment used and customer feedback. The proposed framework will help company representatives understand the factors that affect costs and the technical components that represent the methods and processes used by the company. In addition, the commercial structure can be used to promote and sell the adsorbent materials.

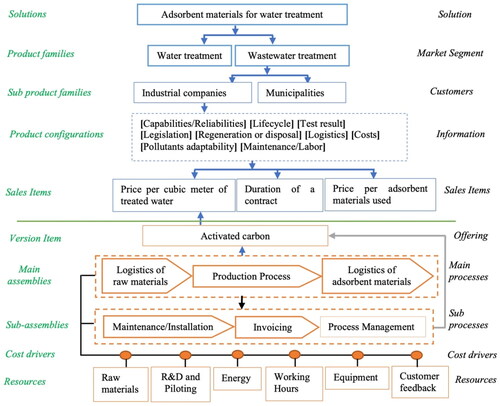

The results and analysis of the empirical research indicates that adsorbent materials can be sold either through a product-oriented item approach (i.e. selling the adsorbent materials) or through a result-oriented item approach (i.e. customers pay based on the result of the water treatment).

4.3.3. Product-oriented sales item

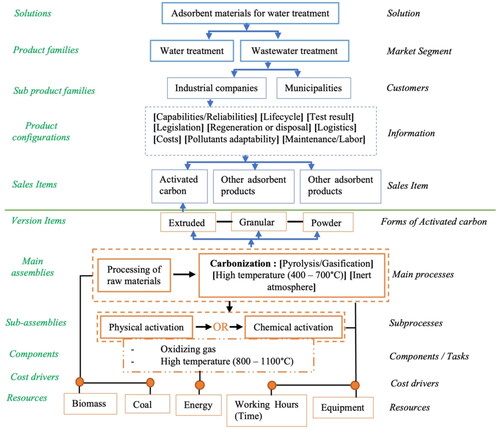

illustrates the productization of adsorbent materials in a product-oriented item approach. Several adsorbent materials are used in highly variable production methods for water treatment. Here, the most commonly used adsorbent material, activated carbon, is selected as an example in .

Figure 3. Productization framework of adsorbent material as product-oriented sales item using activated carbon as an example.

In the example, the customer has chosen extruded activated carbon as the adsorbent material for wastewater treatment for an industrial company. All the information about the material is obtained from the information section of the commercial structure, and each sales item has a respective preparation description in the technical framework. The technical part describes the main processes and subprocesses with individual tasks for producing extruded activated carbon. The internal connection between the price of a sales item and its manufacturing cost can be used to calculate the related profit margin. The price may vary depending on the tasks and cost drivers (the price of energy, the working hours considered, and the tools used).

Customers can choose to buy the adsorbent materials as a physical product (product-oriented), depending on the market segment, based on the detailed information that the manufacturer provides in the commercial structure. The commercial structure is linked to the technical structure, which helps manufacturers price their product competitively, estimate manufacturing costs, and adjust production tasks according to customer requirements. The main processes, sub-processes, and tasks based on cost drivers and the resources available for producing the adsorbent materials are described and categorized in the technical framework. Due to the differences in the production processes of the adsorbents, production costs also vary. The manufacturing cost for each item and its selling price can be used to determine profitability.

4.3.4. Result-oriented sales item

illustrates the productization of adsorbent materials from a result-oriented perspective. The materials are manufactured, in this case, for use in the services provided by the adsorbent manufacturer or some other company rather than for sale to the end user. The commercial logic here is similar to the structure of the product-oriented description given above. In such a scenario, the sales item for the adsorbent materials is the water treatment result (e.g. the volume of treated water). The services (usage of the adsorbent materials) can also be offered under a contract for a predetermined period, which entails full responsibility (e.g. maintenance, regeneration, disposal, etc.). The cost varies depending on the duration of the contract and the assigned responsibilities. The customer pays only for the result, for example, per volume of water treated to meet the quality requirements. The amount of treated water or the adsorbent materials required to treat the quantity of water determines how much the selling item will cost. In this situation, calculating the selling price may be difficult and represent a risk for the service provider; but precise manufacturing and internal processing costs can be analyzed using the technical structure. Before the agreement, both parties need to agree with regard to the price. The technical structure describes the processes and resources that are used in the production of the adsorbent material, which are internally connected to the sales items in the commercial structure (i.e. price per treated water or adsorbent material used). The production operations and billing are closely linked to the sales items. The technical process implementation and costs for the production of adsorbent materials the first time are driven mainly by R&D activities and customer feedback. After the product has been sold, the costs mainly come from manufacturing the adsorbent, handling the logistics, and running the services. Internal expenses can be calculated based on the completed tasks, allowing for a profit information that is related to the outcomes. Since the customer pays for the results, the service provider takes care of maintenance, owns the product, and provides other services, such as regeneration and disposal.

In , the customer pays based on the volume of industrial wastewater treated to the required quantity level. The information about adsorbent materials to be selected for wastewater treatment for industrial companies can be obtained from the commercial structure. Further, the commercial structure is linked to the technical one such that each process can be adjusted according to the selection of sales items. Supplementary services such as testing, logistics, and installation are added to the product, and customer feedback is implemented in the development activities of the adsorbent materials. By estimating the actual manufacturing cost, a competitive price can be determined for the sales items, and profitability can be calculated. Once the main process is performed and commercial delivery is made for the selected sales item, only sub-processes (maintenance, invoicing) are performed until the customer does not change the sales item.

5. Discussion and conclusions

This study aimed to develop a productization approach that facilitates the commercializing of novel adsorbent materials. The research results highlight the challenges and opportunities inherent in adsorbent materials productization. The empirical analysis illustrated the customers’ expectations from adsorbent manufacturers and the manufacturers’ expectations from the customers (adsorbent users) that should be considered for the novel adsorbent materials commercialization. Finally, based on the literature and empirical research, a business model and productization frameworks were formulated for adsorbent materials.

The amount of publications on the subject of adsorbent materials that examine preparation methods, chemical modification, and performance has grown exponentially (Mudhoo et al., Citation2021). Most of the publications (e.g. Al Natsheh et al., Citation2022; Han et al., Citation2021; Sivaprasad et al., Citation2022) have focused on adsorbent preparation materials, development of low-cost adsorbent materials, and their testing in laboratory-scale experiments. Very few publications (e.g. Ali & Gupta, 2007; Pillai, Citation2020) have addressed the commercialization of adsorption technology, and there is a considerable discrepancy between the research volume and the number of new commercial products introduced in the market. This is partly because practically no research is being conducted on the novel adsorbent materials commercialization aspects. Thus, a productization framework (the product’s commercial and technical structure) and a business model framework were proposed in this study to enhance the adsorbent materials commercialization.

According to Härkonen et al. (Citation2019), Mustonen et al. (Citation2019), and Härkonen (Citation2021) the most obvious result of productization is to describe a service or any other intangible deliverable as a tangible and standardized product as a part of a system where increasing competitiveness and efficiency are the two main drivers. In order to transform technological capabilities into economic and contextually suitable products and services, commercialization entails combining necessary resources, developing value for competing products and services, and launching these offerings into the marketplace (Frattini et al., Citation2012; Krishnan, Citation2013). The business model concept, in turn, is a strategy implementation tool that helps identifying and expressing a business idea or concept by mapping, designing, and discussing new business concepts in an efficient manner. This is accomplished by linking the company’s ability to produce value for customers, its internal strategy for productization, and its external network for commercialization. Under the same perspective, in this study, the following functions served as the foundation for the development of the business model and productization framework to enhance the commercialization of adsorbent materials used in water treatment: Offering (products or services), value creation system (identifying clients, their needs, and expectations), revenue model (pricing, market, and network), and product structure (commercial and technical).

We found five key factors (legislation and standards, treatment costs, water quality, relationships with customers, and variation in customer requirements) that should be considered during the commercialization of adsorbent materials. Additionally, we observed that expectations between adsorbent users and producers frequently fall short and appear to be very difficult to be met by these parties. Therefore, it is recommended to use the business model and productization framework that was developed in this study.

This study shows the technical and commercial product structure of the adsorbent materials used for water and wastewater treatment, demonstrating that the adsorbent materials productization can follow the same principles and procedures as those for productization processes in other domains (e.g. Leppänen et al., Citation2020; Mustonen et al., Citation2019; Simula et al., Citation2008). The productization of adsorbent materials opens up new possibilities for business, such as identifying appropriate pricing structures, adsorbent materials commercial information, cost drivers, and customer requirements. A commercial structure helps make adsorbent material products commercially viable. At the same time, the technical structure defines the processes required to manufacture the products. The productization framework (adsorbent materials as product-oriented or result-oriented sales items) that was created based on the literature and empirical research contributes to aiding companies with the commercialization of novel adsorbents.

We also identified challenges in commercialization that must be overcome. As observed in earlier studies, challenges arise in recognizing and communicating the critical needs of the business and its customers due to ambiguity and complexity in the nature of the work performed (Hänninen et al., Citation2012; Härkonen et al., Citation2015, Citation2019; Mustonen, Citation2020). In a similar view, our research showed that adsorbent materials commercialization is hindered by several factors, which include the properties of adsorbents (quality, availability, lifespan, and adaptability), profitability issues (regeneration, disposal, and logistics costs), and practices related to environmental legislation, testing, and verification. We also found that clients in this market are often satisfied with the existing adsorbent material, such as activated carbon, making the market relatively difficult to enter. We strongly recommend that commercialization strategies should be formulated early in the research and development process, in parallel with the technological development to result in economically efficient and sustainable value chains.

The cornerstone for productization is a well-defined business model (e.g. Al-Debi et al., Citation2008; Casadesus-Masanell & Ricart, Citation2011; Osterwalder et al., Citation2005; Teece, Citation2010); therefore, adsorbent manufacturers should also invest in business model development as a part of their commercialization efforts. Based on the work of Suikki et al. (Citation2006) and empirical research, a framework for business model was developed to describe the value creation, offering, and revenue model aspects. The business model framework, along with the dimensions for evaluating business models, is used to describe the reference business model for commercializing adsorbent materials.

This study focused on the adsorbent materials used for water and wastewater treatment, but the proposed approach and the study outcomes can also be utilized for the commercializing other novel adsorbent materials. However, the limitations of this study must also be acknowledged. This study is examined only a small number of companies in a specific geographical area. Furthermore, the size and age of the analyzed companies range from small to large and from new to old, respectively. These issues limit the generalizability of the results. The future research needs, besides addressing these limitations, include topics, such as logistics of raw materials and adsorbents, large-scale production, and offering adsorbent materials as a service. We also encourage further empirical studies to validate and compare our findings.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the interviewees that participate in this research. They also acknowledge funding from the University of Oulu & The Academy of Finland Profi5 326291.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Al-Debi, M. M., El-Haddadeh, R., & Avison, D. (2008). Defining the Business Model in the New World of Digital Business. Proceedings of the Americas Conference on Information Systems, Toronto, 14-17 August 2008, 1–11.

- Al Natsheh, A., Gbadegeshin, S. A., Rimpilainen, A., Imamovic-Tokalic, I., & Zambrano, A. (2014). Building a sustainable start-up? Factors to be considered during the Technology Commercialization Process. Journal of Advanced Research in Entrepreneurship and New Venture Creation, 1(1), 4–19.

- Al Natsheh, A., A. Gbadegeshin, S., Rimpiläinen, A., Imamovic-Tokalic, I., & Zambrano, A. (2015). Identifying the challenges in commercializing high technology: A case study of quantum key distribution technology. Technology Innovation Management Review, 5(1), 26–36. https://doi.org/10.22215/timreview864

- Ai Natsheh, A., Gray, A., & Luukkonen, T. (2022). Drivers and barriers for productization of alkali-activated materials in environmental technology. In Alkali-activated materials in environmental technology applications (pp. 407–426). Woodhead Publishing.

- Ali, I., & Gupta, V. K. (2006). Advances in water treatment by adsorption technology. Nature Protocols, 1(6), 2661–2667. https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2006.370

- Babel, S., & Kurniawan, T. A. (2003). Low-cost adsorbents for heavy metals uptake from contaminated water: A review. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 97(1–3), 219–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-3894(02)00263-7

- Bocken, N. M., De Pauw, I., Bakker, C., & Van Der Grinten, B. (2016). Product design and business model strategies for a circular economy. Journal of Industrial and Production Engineering, 33(5), 308–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681015.2016.1172124

- Budzianowski, W. M., & Brodacka, M. (2017). Biomethane storage: Evaluation of technologies, end uses, business models, and sustainability. Energy Conversion and Management, 141, 254–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2016.08.071

- Casadesus-Masanell, R., & Ricart, J. E. (2011). How to design a winning business model. Harvard Business Review, 89(1/2), 100–107.

- Clifford, D. A. (1990). Water quality and treatment: A handbook of community water supplies. McGraw-Hill.

- Corkindale, D. (2010). Towards a business model for commercializing innovative new technology. International Journal of Innovation and Technology Management, 07(01), 37–51. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219877010001817

- Daou, A., Mallat, C., Chammas, G., Cerantola, N., Kayed, S., & Saliba, N. A. (2020). The Ecocanvas as a business model canvas for a circular economy. Journal of Cleaner Production, 258, 120938. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120938

- European Union. (2006). Regulation (EC) No. 1907/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 December 2006. Official Journal of the European Union, L 396, 1–849. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A02006R1907-20140410.

- European Union. (2008). Directive 2008/98/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 November 2008 on waste and repealing certain Directives (text with EEA relevance). Official Journal of the European Union, L 312, 3–30. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2008/98/oj.

- Frattini, F., de Massis, A., Chiesa, V., Cassia, L., & Campopiano, G. (2012). Bringing to market technological innovation: What distinguishes success from failure regular paper. International Journal of Engineering Business Management, 4(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.5772/51605

- Gbadegeshin, S. (2018). Lean Commercialization: A New Framework for Commercializing High Technologies. Technology Innovation Management Review, 8(9), 50–63. https://doi.org/10.22215/timreview/1186

- Han, B., Butterly, C., Zhang, W., He, J.-Z., & Chen, D. (2021). Adsorbent materials for ammonium and ammonia removal: A review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 283, 124611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124611

- Hänninen, K., Kinnunen, T., & Muhos, M. (2012). Rapid productization–empirical study on preconditions and challenges. Department of Industrial Engineering and Management, University of Oulu.

- Härkonen, J., Haapasalo, H., & Hanninen, K. (2015). Productisation: A review and research agenda. International Journal of Production Economics, 164, 65–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2015.02.024

- Härkonen, J., Mustonen, E., & Hannila, H. (2019). Productization and product structure as the backbone for product data and fact-based analysis of company products. In 2019 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management (IEEM), 474–478. https://doi.org/10.1109/IEEM44572.2019.8978845

- Härkonen, J. (2021). Exploring the benefits of service productisation: support for business processes. Business Process Management Journal, 27(8), 85–105.

- Jaakkola, E. (2011). Unraveling the practices of “productization” in professional service firms. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 27(2), 221–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2011.03.001

- Kim, M., Park, H., Sawng, Y. W., & Park, S. Y. (2019). Bridging the gap in the technology commercialization process: Using a three-stage technology–Product–Market Model. Sustainability, 11(22), 6267. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226267

- Kinnunen, T., Hanninen, K., Haapasalo, H., & Kropsu-Vehkapera, H. (2014). Business case analysis in rapid productisation. International Journal of Rapid Manufacturing, 4(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJRAPIDM.2014.062013

- Kropsu-Vehkapera, H., & Haapasalo, H. (2011). Defining product data views for different stakeholders. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 52(2), 61–72.

- Lambert, S. (2008). A conceptual framework for business model research. BLED 2008 Proceedings, 18, 24.

- Kirkegaard Sløk-Madsen, S., Ritter, T., & Sornn-Friese, H. (2017). Commercialization in innovation management: Defining the concept and a research agenda. Academy of Management Proceedings, 2017(1), 15880. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMBPP.2017.15880abstract

- Krishnan, V. (2013). Operations management opportunities in technology commercialization and entrepreneurship. Production and Operations Management, 22(6), 1439–1445. https://doi.org/10.1111/poms.12012

- Kuula, S., Haapasalo, H., & Tolonen, A. (2018). Cost-efficient co-creation of knowledge intensive business services. Service Business, 12(4), 779–808. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11628-018-0380-y

- Leppänen, T., Mustonen, E., Saarela, H., Kuokkanen, M., & Tervonen, P. (2020). Productization of industrial side streams into by-products – Case: Fiber sludge from pulp and paper industry. Journal of Open Innovation, 6(4), 185. https://www.mdpi.com/919284. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc6040185

- Magretta, J. (2002). Why business models matter. Harvard Business Review, 80(5), 86–92, 133.

- Mudhoo, A., Mohan, D., Pittman, C. U., Jr., Sharma, G., & Sillanpää, M. (2021). Adsorbents for real-scale water remediation: Gaps and the road forward. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 9(4), 105380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2021.105380

- Mustonen, E., Härkonen, J., & Haapasalo, H. (2019). From product to service business: Productization of product-oriented, use-oriented, and result-oriented business. In 2019 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management (IEEM), 985–989. https://doi.org/10.1109/IEEM44572.2019.8978581

- Mustonen, E. (2020). Vertical Productisation over Product Lifecycle: Co-Marketing through a Joint Commercial Product Portfolio. University of Oulu.

- Osterwalder, A., Pigneur, Y., & Tucci, C. L. (2005). Clarifying business models: Origins, present, and future of the concept. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 16, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.17705/1CAIS.01601

- Osterwalder, A., & Pigneur, Y. (2010). Business model generation: A handbook for visionaries, game changers, and challengers. John Wiley & Sons.

- Ouden, den, P. H. (2006). Development of a design analysis model for consumer complaints: revealing a new class of quality failures. Doctor of Philosophy, Industrial Engineering and Innovation Sciences, Eindhoven. https://doi.org/10.6100/IR601501

- Paulin, W. L., Belt, P., Mottonen, M., Härkonen, J., & Haapasalo, H. (2012). Action research on high-tech SMEs entering the USA market. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management, 16(3/4), 209–225. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJEIM.2012.051901

- Payne, A. F., Storbacka, K., & Frow, P. (2008). Managing the co-creation of value. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36(1), 83–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-007-0070-0

- Pellikka, J., & Malinen, P. (2014). Business models in the commercialization processes of innovation among small high-technology firms. International Journal of Innovation and Technology Management, 11(02), 1450007. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219877014500072

- Petry, T., Knowles, R., & Meads, R. (2006). An analysis of the proposed REACH regulation. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology: RTP, 44(1), 24–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yrtph.2005.07.007

- Pillai, S. B. (2020). Adsorption in water and used water purification. In J. Lahnsteiner (Ed.), Handbook of water and used water purification. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-66382-1_4-1

- Rao, K., Hanjra, M., Drechsel, P., & Danso, G. (2015). Business Models and Economic Approaches Supporting Water Reuse. In: Drechsel, P., Qadir, M., Wichelns, D. (eds) Wastewater. Springer, Dordrecht, pp. 195–216. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9545-6_11

- Simula, H., Lehtimäki, T., & Salo, J. (2008). Re-thinking the product: From innovative technology to productized offering. In Proceedings of the 19th International Society for Professional Innovation Management Conference, Tours, France. 15–18.

- Sivaprasad, S., Jayaseelan, A., Kannappan Panchamoorthy, G., Gautam, R., Manandhar, A., & Shah, A. (2022). Biomass as source for hydrochar and biochar production to recover phosphates from wastewater: A review on challenges, commercialization, and future perspectives. Chemosphere, 286(1), 131490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.131490

- Spilling, O. R. (2004). Commercialization of knowledge–conceptual framework. In 13th Nordic Conference on Small Business (NCSB) Research.

- Suikki, R. M., Goman, A. M. J., & Haapasalo, H. J. O. (2006). A framework for creating business models a challenge in convergence of high clock speed industry. International Journal of Business Environment, 1(2), 211. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBE.2006.010685

- Suominen, A., Kantola, J., & Tuominen, A. (2009). Reviewing and defining productization. In 20th Annual Conference of the International Society for Professional Innovation Management (ISPIM 2009).

- Sylvester, P. (2015). Innovative Materials and Methods for Water Treatment: Solutions for Arsenic and Chromium Removal. CRC Press.

- Teece, D. J. (2010). Business models, business strategy, and innovation. Long Range Planning, 43(2–3), 172–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2009.07.003

- Tolonen, A., Härkonen, J., & Haapasalo, H. (2014). Product portfolio management – Governance for commercial and technical portfolios over life cycle. Technology and Investment, 05(04), 173–183. https://doi.org/10.4236/ti.2014.54016

- Villanueva, A., Delgado, L., Luo, Z., Eder, P., Catarino, A. S., & Litten, D. (2010). Study on the selection of waste streams for end-of-waste assessment. JRC Scientific and Technical Reports, EUR, 24362.

- Villanueva, A., & Eder, P. (2014). End-of-waste criteria for waste plastic for conversion. Institute for Prospective Technological Studies.

- Williams, E. S., Panko, J., & Paustenbach, D. J. (2009). The European Union’s REACH regulation: A review of its history and requirements. Critical Reviews in Toxicology, 39(7), 553–575. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408440903036056

- Worch, E. (2021). Adsorption technology in water treatment. In adsorption technology in water treatment. De Gruyter.