?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

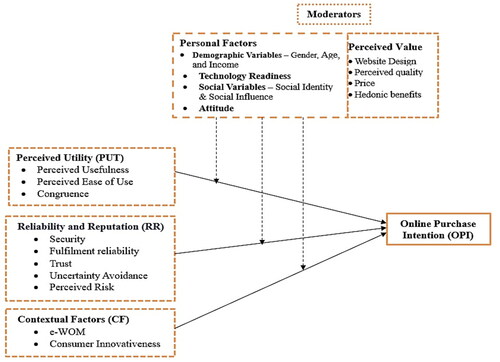

This meta-analytic review conceptualises and synthesises the study factors related to this phenomenon to effectively comprehend online purchasing intention. This study’s "online purchase intention" concerns consumers’ propensity or likelihood to purchase via online channels. This review develops a conceptual framework that clarifies the aspects influencing online purchase intention by analysing pertinent data. The variables under investigation encompass usefulness, ease of use, congruence, trust, security, e-WOM and many other demographics and contextual factors. The potential moderators were also identified, and the moderating effect is validated in the study variable as framed in the conceptual framework. This review contributes to the field by offering valuable insights into the determinants of online purchase intention, enabling marketers and researchers to devise effective strategies to optimise consumer behaviour in the online shopping domain.

1. Introduction

The growing popularity of online platforms and shopping has rapidly increased with time. The proliferation of the Internet and mobile phones has completely changed the online scenario. The Internet’s rapid penetration has massively turned around business activities, and Internet-enabled business has become a new phenomenon (Ruiz Mafé & Sanz Blas, Citation2006). Considering the massive set of advantages that the business offers online, consumers have also shifted their base towards online shopping and started exploring the diverse avenues of the business. Online shopping is one aspect the present-day customer is hooked on (Deng et al., Citation2021). The variety of offers in the forms of coupons, sales, lucrative discounts, and features of instantaneity, localisation, and super-personalisation have attracted many customers to these platforms and to shop online (Pan et al., Citation2017). Online shopping is not restricted to electronics, apparel, or basic needs. The periphery of online shopping has expanded its limits to every avenue. From basic needs to food, travel, bookings, and other desires, humans can think can be done and preferred online (Teo, Citation2002; Wani & Wajid, Citation2016). The benefits, the flexibility, and the broader possibilities have made this the most feasible option among the consumer. The recent COVID-19 pandemic has also enhanced online shopping owing to increased sales (Soares et al., Citation2023). The spending and purchase habits have changed after the massive pandemic hit (Alvarez-Risco et al., Citation2022; Truong & Truong, Citation2022).

However, along with the wide range of apparent benefits of internet-enabled online transactions, it also counters the fear of trust, anxiety, risk, and fraud, which results in an unwillingness. It refrains consumers from making that final purchase online. Hence, the consumer becomes reluctant to engage in online transactions (Jaradat et al., Citation2018). Owing to the advent of online platforms, the risk of fraudulence has also increased; hence, consumers usually search for goods and services online to understand the scenario while refraining from the final purchase (Bauman & Bachmann, Citation2017). As a result, it is now crucial for academics and practitioners to examine the aspects that impact the choice to purchase anything online. The meta-analytic review in this article is focused on comprehending the study factors related to online purchasing intention. As a statistical technique for blending the findings of multiple investigations, meta-analysis is an excellent tool to compile and analyse a considerable body of data systematically and impartially (Amos et al., Citation2014). This review tries to provide a thorough knowledge of the underlying elements influencing customers’ desire to purchase online by looking at a wide range of studies. This study aims to offer a thorough assessment of the existing knowledge base about purchase intention research in the context of online shopping and to provide a thorough grasp of the research that has happened so far in this field.

The research attempts to collate and segregate all the previous studies and perform a meta-analysis to help understand the antecedents and the determining factors that finally govern the online purchase intention studies. Additionally, the current meta-analysis, apart from investigating the distinct roles of the impactful variables, in coherence with the argument put forward by previous researchers, also put forth an exclusive grouping of the prevalent study variables which were earlier studied in silos. This research fills the gap by putting forth this unique categorisation of the study variables by bringing them together and further establishing their conceptual distinctions among the constructs. This unique categorisation of the study variables has emerged from past studies of diverse temporal trends in geographical areas and widely considered theoretical frameworks. Hence, identifying and validating them in this unique standpoint will offer a distinctive direction to future studies in online purchase intention.

The research article follows the subsequent structure. The first section of this article highlights the increasing significance of comprehending the factors that shape consumers’ decision-making processes in the online environment. The crucial factors examined concerning online purchase intention are included in the following sections. This review explores these variables’ relative significance and the potential mechanisms that affect online purchase intention. Then, in the next step, the study identified potential moderators from several research, offering insightful information that might affect the relationship between the study variables. This review presented a nuanced knowledge of the existing literature in the subsequent section by presenting various methodological criteria, such as sample characteristics, measurement scales, and data coding methods. The results of this meta-analytic review are provided with probable managerial and conceptual implications. Finally, the study’s limitations and future directions are discussed for greater comprehension. The insight gained from this review has significant implications for academics and business, enabling a more profound comprehension of online customer behaviour and guiding evidence-based choices in the ever-changing e-commerce environment.

2. Literature review and hypothesis development

Previous studies in this area have used several theories, majorly including the Technology Adoption Model (TAM), Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA), Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB), and Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use Of Technology (UTAUT) and its derivatives (Akhlaq & Ahmed, Citation2015; Har Lee et al., Citation2011; Isaac et al., Citation2017; Kaur & Thakur, Citation2019; Keisidou et al., Citation2011; Law et al., Citation2016; Ranaweera et al., Citation2008; Venkatesh & Morris, Citation2000). As antecedents of online purchase intention, previous researchers have looked mainly at the technological acceptance criteria such as perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, perceived behavioural control, perceived risk, subjective norms, enjoyment, attitude, and perceived risk. This derivative has been looked at frequently, along with a few additional derivatives of external factors such as e-WOM, cultural norms, platform diversity, social influence, and innovations. Apart from all these, past studies have also identified a few mediators and moderators that play a crucial role in driving purchase intention online. For this meta-analysis study, the frequently and repeatedly used study variables were segregated to put together in groups and then showcased in a well-structured conceptual framework to understand the body of work that has happened so far and which also gives a clear and expressive dimension in context to online purchase intention. The study variables were put together considering their coherence, and they established their role in online purchase intention. The identified study variables from the past studies were clubbed into three categories: Perceived Utility (PUT), Reliability and Reputation (RR), and Contextual Factors (CF) that lead to Online Purchase Intention (OPI). Additionally, the mediators/moderators considered in the past studies were categorised into two categories – Personal factors (PF) and Perceived Value (PV) driving the purchase intention online.

2.1. Perceived utility (PUT)

2.1.1. Perceived usefulness

TAM states that a technology’s intended adoption is based on how useful people perceive it (Fortes & Rita, Citation2016). The subjective probability that an individual will think shopping online is more practical than in-person shopping can be used to determine the perceived usefulness of online buying (Chiu et al., Citation2014; Koufaris, Citation2002; Law et al., Citation2016). Perceived usefulness assesses how much Internet usage will enhance purchasing power (e.g., convenience, agility, and time). According to the literature, perceived usefulness positively correlates with purchase intention (Law et al., Citation2016). E-commerce is viewed as more affordable and practical than in-person transactions (Ventre & Kolbe, Citation2020). The customer will likely have a better opinion of the website and return to it if they feel that using it and that particular site to make their purchases is beneficial (Koufaris, Citation2002; Moslehpour et al., Citation2018). Unlike offline purchases, online platforms typically offer various products, increasing the likelihood that customers will find the desired item (Chiu et al., Citation2014). The Internet’s frequency, duration, and use increased when users perceived it as a helpful tool, changing the platform on which customers purchase (Isaac et al., Citation2017). Internet use is positively impacted by perceived usefulness (Isaac et al., Citation2017), and prior research has found substantial positive relations between perceived usefulness and attitudes toward online shopping (Celik & Yilmaz, Citation2011; Chiu et al., Citation2005; Law et al., Citation2016; Moslehpour et al., Citation2018; Sukno & Pascual del Riquelme, Citation2019). In this approach, the hypothesis framed is as follows:

H1a: Perceived usefulness significantly and positively impacts OPI.

2.1.2. Perceived ease of use

The TAM dimension, "perceived ease of use," measures how much a person thinks utilising a particular technology will be effortless (Davis & Venkatesh, Citation1996). According to the reviewed studies, a person’s attitude toward and desire to use a particular technology are influenced by how simple it is (Law et al., Citation2016). The literature also highlights how perceived ease of use affects utility, contending that the more a given technology is viewed as valuable by a consumer, the more user-friendly it is (Isaac et al., Citation2017). Nevertheless, compared to other studies (Chiu et al., Citation2005; Law et al., Citation2016), this research aims to determine the range and validity of the framework in which the perceived ease of purchase is expressed, which affects the dimension’s focal point. As a result, the belief that an online purchase will require less effort than an offline physical transaction constitutes the perceived ease of purchase (Koufaris, Citation2002; Law et al., Citation2016). Because online users are becoming more accustomed to using online platforms easily, the dimension can be considered an extension of the previous construct. Celik and Yilmaz (Citation2011) reported that innovative and effective online purchasing techniques, such as apps, have been widely adopted due to the Internet and e-commerce. Therefore, the ease of use of technology affects the user’s perception of its usefulness and tendency to use it more frequently (Sukno & Pascual del Riquelme, Citation2019). As a result, the perceived ease of use is crucial to the online shopping experience and is closely tied to the intentions to purchase (Moslehpour et al., Citation2018). Additionally, numerous research studies have already examined and determined the connection between perceived utility and perceived ease of use, as well as how those two factors relate to the intention to purchase (Celik & Yilmaz, Citation2011; Chopdar et al., Citation2022; Kim, Citation2012; Manis & Choi, Citation2019; Sukno & Pascual del Riquelme, Citation2019) which brings us to frame the hypothesis of the study as:

H1b: Perceived ease of use significantly and positively impacts OPI.

2.1.3. Congruence

Fit and congruence are separate things, as Bezes (Citation2013) explains. Congruence is based on impressions of similarities between ideas about two different things. If there is a high level of congruence between the customer brand expectations about the new channel, then consumers will rely on a more thorough approach to evaluate the new channel, and they may even mimic their behaviours in the new online context, including loyalty patterns. This processing leads to quicker transmission attitudes (Wang & Herrando, Citation2019). Nevertheless, what if there is a disparity? (i.e., perceived incongruence). In that instance, this direct and comprehensive transfer might not occur, resulting in a more involved and time-consuming evaluation procedure and, possibly, a more unfavourable inclination from the consumer’s standpoint (Badrinarayanan et al., Citation2014). Most studies have examined how well offline and online retailers’ images align (Wu et al., Citation2018) or conceived congruity as a one-dimensional concept (Badrinarayanan et al., Citation2014; Wang et al., Citation2009). A few studies have also compared congruity attribute by attribute (e.g., Badrinarayanan et al., Citation2014; Verhagen & van Dolen, Citation2009). Badrinarayanan et al. (Citation2014), as a reference work, conceptualised as a higher-order factor with the following sub-dimensions: environment, service, pricing orientation, security, transaction convenience, and aesthetic appeal for a multichannel retailer’s online and physical storefronts. These characteristics can be contrasted between online and brick-and-mortar retailers, including experiential (visual appeal, atmosphere) and functional (navigation, convenience) elements. Verhagen and van Dolen (Citation2009) revealed that a critical predictor of consumers’ intention to make an online purchase is the atmosphere of the online store (as assessed by fun, pleasure, and attractiveness).

H1c: Congruence significantly and positively impacts OPI.

2.2. Reliability and reputation (RR)

2.2.1. Security

Through website features that offer accurate product details, transactional and competent service quality and delivery capacity, customers can learn about the value of products. Without adequate knowledge of the security measures, purchase intent will be deterred. According to Azizi and Javidani (Citation2010), disclosure of financial details, such as credit card numbers, account numbers, and PINs, is associated with security. Security concerns are acknowledged as a hindrance to internet shopping (Teo, Citation2002). Although consumers can buy and use things more easily online, the lack of security measures will negatively impact consumers’ purchase intentions (Meskaran et al., Citation2013; Tsai & Yeh, Citation2010). Consumers are reluctant to make online purchases, enter their credit card information, and even ship information (Leeraphong & Mardjo, Citation2013). However, when customers shop online, It is necessary to provide more personal data, such as the delivery address, personal preferences, and numerous other specifics (Dai et al., Citation2014). According to Hsu and Bayarsaikhan (Citation2012), security issues negatively affect online purchase plans. Customers uncomfortable with an online site will refrain from providing their personal information and are more likely to offer inaccurate or erroneous information (Kayworth & Whitten, Citation2010). Online purchase chance correlates significantly with security issues (Teo & Liu, Citation2007). According to Martín and Camarero, (Citation2009), consumers avoid Internet shopping because they are concerned about having their personal information stolen, not because it is inconvenient. Thus, they conclude that security risk significantly affects the intention to shop online. Adnan (Citation2014) said that privacy measures are necessary to lower customers’ perceived security risk and increase their propensity to purchase online clothing. Considering the preceding discussion, the hypothesis is suggested:

H1d: Security significantly and positively impacts OPI.

2.2.2. Fulfilment reliability

According to Wolfinbarger and Gilly (Citation2003) definition of fulfilment reliability, this involves both the timely delivery of the appropriate goods within the predetermined time range as well as the accuracy of product descriptions offered on the website so that customers may acquire what the online retailer promised them for their order. Although it is appropriate for online shopping, customers wait a few days or weeks before receiving their purchases once they place orders (Kautish et al., Citation2021). When establishing a long-term relationship with an e-tailer, customers are most considerate about fulfilment reliability (Kautish et al., Citation2021; Keeling et al., Citation2013). Therefore, a necessary condition to ensure fulfilment reliability is to fulfil the product assurances, service promises, and customers’ orders following the product/service information displayed. Customers’ positive responses concerning aspects of shopping assistance are positively impacted by putting more effort into performance and focusing on the quality of e-tail services within a reasonable time frame, receiving the right product ordered, and receiving the product in its proper form (Peinkofer et al., Citation2016). Customers’ attitudes toward online purchases were strongly affected by prompt, encouraging, and time-bound responses to their queries (Mishra, Citation2017; Pahari et al., Citation2023). The findings of Wolfinbarger and Gilly (Citation2003) and Peinkofer et al. (Citation2016) state that Fulfillment reliability was determined to be the most significant factor in referring to favourable customer replies and in online purchases, according to study results from Wolfinbarger and Gilly (Citation2003) and Peinkofer et al. (Citation2016). Thus, fulfilment reliability was the most crucial element driving online purchases based on references to favourable customer reviews (Peinkofer et al., Citation2016; Wolfinbarger & Gilly, Citation2003). Given the discussion above, the subsequent hypotheses were proposed:

H1e: Fulfilment reliability significantly and positively impacts OPI.

2.2.3. Trust

Online trust is the most critical component of corporate strategy, according to Bauman and Bachmann (Citation2017), as it reduces perceived risk and generates favourable word of mouth. Predictability, dependability, and fairness are the three critical components of the word "trust," in which the values are examined by comparing the expenses of establishing and maintaining the relationship with their real value to the client (Yuen et al., Citation2018). In their study, Kim and Park (Citation2013) discussed that "perceived ability, perceived benevolence/integrity, perceived critical mass, and trust in a website were the four major antecedents of trust" relating to social networking site product recommendations. Prior studies have also pointed out that online businesses try to reduce risk at first, which enhances customer trust and subsequently raises purchase intention for online goods and services. Other essential components of trust in online buying include shared values, website privacy, and security features (Katta & Patro, Citation2017; Mukherjee & Nath, Citation2007). The significance of trust in online purchases is a crucial predictor of a person’s attitude and purchase intention (Ashraf et al., Citation2014; Hassanein & Head, Citation2007; Hsu et al., Citation2013; Lin, Citation2011). Online buying is thought to have higher risks for customers because there is no direct contact or engagement (O'Cass & Carlson, Citation2012; Pavlou et al., Citation2007). This signifies that perceived trust is the main factor influencing online shoppers’ sentiments about a product or service (Van der Heijden et al., Citation2003). In this regard, Lin (Citation2011) suggests that attitudes regarding e-shopping were significantly influenced by online trust due to the increasing level of uncertainty and dynamic nature of cyberspace. Therefore, the following hypothesis is:

H1f: Trust significantly and positively impacts OPI.

2.2.4. Uncertainty avoidance

According to Nath and Murthy (Citation2004), those with high levels of uncertainty avoidance consider online platforms as a riskier process, which causes them to reject them. On the other hand, people who do not perceive risk in these transactions are more likely to innovate and adopt them (Agarwal & Wu, Citation2018). Uncertainty avoidance appears to be the individual aspect that is most pertinent to consumer acceptance and use of online shopping (Magnusson et al., Citation2014). The uncertainty-avoidance dimension is also the most frequently used in the research on online consumer behaviour. This is due to the simplicity with which it can be interpreted in the context of the online market, as well as the fact that the existing research indicates that personality traits like perceived risk and trust are among the most significant factors influencing consumers’ purchasing decisions (Cheung et al., Citation2005). According to other researchers working in the digital and online context, uncertainty is always associated with ambiguity about how a decision will turn out (Hyun et al., Citation2022; Jordan et al., Citation2018). It is broadly recognised that the probability of an online transaction success is low as the uncertainty level increases. It is common to think of uncertainty avoidance in terms of the probability of avoiding the risk of getting a negative outcome.

H1g: Uncertainty avoidance significantly and positively impacts OPI.

2.2.5. Perceived risk

In the terminology of Schierz et al. (Citation2010), the expectation of losses is perceived risk. According to Laroche et al. (Citation2005), perceived risk refers to the unfavourable perceptions of unpredictable and changing outcomes from purchased products. Consumer purchase intentions are significantly influenced by perceived risk. According to Lee and Lin (Citation2005), customers who perceive more significant risks are less inclined to make online purchases. (Kim and Park (Citation2013) argued that the consumer’s online purchase intentions are weaker the higher the perceived risk of shopping at online retailers. Akhlaq and Ahmed (Citation2015) highlighted that customer intentions to make online purchases are negatively impacted by perceived risk. This shows that when consumers learn that an online transaction is risky, their desire to purchase is suppressed. Previous findings show a negative relationship between online purchasing intentions and perceived risk (Akhlaq & Ahmed, Citation2015; Zhao et al., Citation2017). Performance, financial, time, safety, social, and psychological risks are all included in perceived risk, as per Featherman and Pavlou (Citation2003).

In contrast, Bhukya and Singh (Citation2015) findings on purchase intention looked at four categories of perceived hazards: functional, financial, physical, and psychological. Han and Kim (Citation2016) investigated a multidimensional perceived risk in the setting of an online marketplace, including financial, privacy, product, security, social/psychological, and time dimensions. Çera et al. (Citation2020) underline that product, financial, and security concerns are the most significant in the perceived risk category, with the framework of online purchasing being more intensive than other dimensions.

H1h: Perceived risk significantly and positively impacts OPI.

2.3. Contextual factors (CF)

2.3.1. e-WOM

Erkan and Evans (Citation2016) stated that online reviews play an important role in covering the anonymity issue of online reviews on shopping websites. See-To and Ho (Citation2014) mentioned that electronic word of mouth (e-WOM) is one of the inexpensive online reviews which affect the purchase intention in social network sites (SNSs). Previous research stated that positive e-WOM increases purchase intention, and negative e-WOM reduces purchase intention. According to Chan and Ngai (Citation2011) and See-To and Ho (Citation2014), e-WOM influences purchase intention through the impact of e-WOM on consumers’ trust and value co-creation. The findings showed that the impact of e-WOM in SNS is an essential proposition for marketers, which can help marketers design a better method to propagate the marketing messages through SNS and develop positive e-WOM for the firms and the products and services. As more people use social media and the Internet to find relevant information, e-WOM has become increasingly popular. Online users think online opinions are trustworthy and credible (Dwidienawati et al., Citation2020; Ventre & Kolbe, Citation2020). Previous research on online shopping emphasised the importance of e-WOM in building online trust (Awad & Ragowsky, Citation2008; Dwidienawati et al., Citation2020; Wang et al., Citation2009). Consumers develop credibility in e-WOM platforms and the content they offer by reading and frequently interacting with e-WOM sources like blogs and websites. Trust formation is also greatly influenced by prior interactions (Hsu et al., Citation2013) in online platforms. Online reviews and recommendations are crucial for consumers looking for new details about goods and services and information on service quality (Chevalier & Mayzlin, Citation2006). As a result, e-WOM significantly influences online consumers’ attitudes and perceptions (Rana et al., Citation2023; Ventre & Kolbe, Citation2020). Positive e-WOM improves online shoppers’ attitudes and trust by lowering their perceived risk and uncertainty (Rana et al., Citation2023; Ventre & Kolbe, Citation2020). Considering the discussion above, the following hypotheses are put forth:

H1i: e-WOM significantly and positively impacts OPI.

2.3.2. Consumer innovativeness

Consumer innovativeness is "the degree to which an individual can embrace new knowledge and make innovative decisions without the influence of others," according to Midgley and Dowling (Citation1978, p. 3). Consumer innovativeness was similarly defined by Goldsmith and Hofacker (1991) as "consumers’ inclination to acquaint and accept a new product, procedure, or a delivery channel. “Consumer innovativeness may be innate or actualised (Zhang et al., Citation2020). While actualised Innovativeness is related to behavioural manifestations of Innovativeness (Zhang et al., Citation2020), which are reflected through decisions to buy or try new products or technologies (Rašković et al., Citation2016), innate Innovativeness is related to personality traits and psychological aspects (Bartels & Reinders, Citation2011; Chang & Chen, Citation2021). “Technological innovativeness” (Zhang et al., Citation2020) is the expression of innovation (willingness to take risks) when using technology, whereas “product innovativeness” is the reflection of innovation when choosing new products or services (Al-Jundi et al., Citation2019). The current study defines consumer innovativeness as an actualised innovation more specific to a product and technology. Customers’ tendency to acquire or test new products online is, thus, the precise understanding of consumer innovativeness in the current study. Consumer innovativeness affects the decision of which online platform to use and the intention to purchase products (Fatima et al., Citation2017; Fowler & Bridges, Citation2010; Noh et al., Citation2014). Innovative customers prefer novelty to tradition and are more willing to embrace global trends than the latter (Rašković et al., Citation2016). High-innovative consumers take greater chances to distinguish themselves from low-innovative consumers (Das et al., Citation2021). Since customers cannot physically see, touch, or feel the products online before buying them, more perceived risks are involved (Nawi et al., Citation2019; Thakur & Srivastava, Citation2015). On the other hand, online methods guarantee quicker availability than offline. As a result, highly innovative clients are expected to choose online purchases over in-store ones, enabling them to distinguish themselves from the rest of society by adopting cutting-edge technologies.

H1j: Consumer innovativeness significantly and positively impacts OPI.

3. Potential moderators

Based on theoretical arguments, the following possible moderators were found.

3.1. Personal factors (PF)

3.1.1. Demographic variables – gender, age, and income

3.1.1.1. Gender

In marketing, a particular focus has been on how gender affects decision-making and purchase behaviour. It has also been examined in terms of the procedure for accepting new technologies, with the conclusion that depending on the person’s gender, distinct technology adoption features and uses are assessed (Gefen & Straub, Citation1997; Venkatesh & Morris, Citation2000). In addition, the current study has not revealed any statistically significant variations in internet usage between males and females (Shin, Citation2009; Zhang, Citation2005). Men and women exhibit the same interest in adopting technology regarding their degrees of experience (Teo, Citation2002). As a result, gender inequalities become less pronounced due to specialised technological experience or technology adoption (Sobieraj & Krämer, Citation2020). Previous studies have revealed minimal gender-derived differences among a sample of persons who have used technology before (Cai et al., Citation2017; Shaouf & Altaqqi, Citation2018).

3.1.1.2. Age

Similarly, the traditional literature is reviewed to highlight the significance of users’ ages in understanding their behaviour (Shaouf & Altaqqi, Citation2018; Teo, Citation2002). Age has been considered an essential element in many studies to explain internet shopping behaviour (Mummalaneni & Meng, Citation2009; Noh et al., Citation2014; Shaouf & Altaqqi, Citation2018). According to Venkatesh and Morris (Citation2000), Age is closely linked with the difficulty of interpreting inputs and significantly correlated with the amount of time it takes for untrained individuals to get comfortable using online platforms (Hernández et al., Citation2011; Laroche et al., Citation2005). Age impacts consumers’ first decision to shop online but not their subsequent behaviour, such as the number of transactions or amount spent (McCloskey, Citation2006).

3.1.1.3. Income

Another factor that has gained much academic interest in technology acceptability is income, which may promote or discourage the use of e-commerce (Allard et al., Citation2009; Shin, Citation2009). Numerous research studies have used it to explain shopping behaviour. However, the findings are mixed in their significance (Al-Somali et al., Citation2009; Lu et al., Citation2003; Miyazaki & Fernandez, Citation2001; Raijas & Tuunainen, Citation2001). Internet users with higher incomes perceive fewer implicit risks while making transactions online, affecting their demand for Internet goods and services. Online purchases are discouraged by low income, and when incomes increase due to the capacity to tolerate potential financial losses, views of self-efficacy, simplicity of use, and usefulness should also increase. Since high-income consumers perceive less risk in adopting technology, studies have shown that user income impacts the Internet and e-commerce (Lu et al., Citation2003; Ranganathan & Grandón, Citation2002). Nevertheless, after users gain some experience, their use of technology is not as affected by their income. Therefore, the perceptions, attitudes, and behaviours of seasoned technology users are not significantly influenced by income (Al-Somali et al., Citation2009). This notion is shared by the current study, which has proven that all seasoned internet buyers exhibit similar purchasing behaviours, regardless of their income. Consequently, we formulate the following hypotheses:

H2: Demographic variables significantly influence PUT, RR and CF’s impact on OPI.

3.2. Technology readiness

Technology readiness is the capacity of individuals to adapt and utilise new technologies for accomplishing tasks at home and in the workplace (Parasuraman, Citation2000, p. 308; Parasuraman & Colby, Citation2014). Technology readiness precedes an intention to shop online since it performs a knowledge function in particular and a utilitarian function. Maximising individual usefulness, or satisfying personal needs and desires, is the goal of utilitarian functions (Kumar & Kashyap, Citation2018; Lee & Wu, Citation2017). When something benefits or rewards us, we tend to have positive attitudes. The knowledge function aids people in establishing some stability, clarity, and order in their context. So, the more comfortable people feel using the Internet and other modern technologies, the more enthusiastic they are about online shopping. It stimulates knowledge and utilitarian function, creating the right attitude. The following hypothesis expresses this proposition:

H3: Technology readiness significantly influences PUT, RR and CF’s impact on OPI.

3.3. Social variables

3.3.1. Social identity

Social identity is a psychological notion that describes how individuals act when motivated to maintain their sense of self as a group member (Ely, Citation1994; Kwon & Wen, Citation2010). According to Pan et al. (Citation2017), social networking sites bring individuals with similar interests together in online communities where they can interact and create strong friendships. Users of social networking sites can make frequent use of them by reading messages and exchanging comments with other users. Additionally, they can perform various tasks by utilising characteristics like social commerce, referred to as diverse use. Since consumers can benefit from frequent and varied use, the decision to utilise social media depends on individual factors and concepts of one’s sense of self-based on group memberships that emerge within social networking sites (Ray et al., Citation2014). Social factors serve as a moderator (Pan et al., Citation2017). People with various levels of social identification will, therefore, have various perspectives.

3.3.2. Social influence

Social influence is the propensity for someone to conform their behaviour to that of the group or society (Kahan, Citation1997). Reciprocity, scarcity, social validation, authority, likability and commitment, and consistency are the six components of social influence (Cialdini & Goldstein, Citation2004; Guadagno et al., Citation2013). These concepts, mirrored in the social influence theory, are crucial for persuading behaviour in various contexts (Venkatesh & Morris, Citation2000). Internalisation, identification, and compliance are the three basic processes that social influence frequently depends on when users learn information that advances their knowledge beyond reference groups (Kelman, Citation1961). The processes of identification and compliance result in normative influence. Compliance happens when a user complies with another’s expectations to gain favour or avoid rejection and hostility. In contrast, identification happens when a user embraces a viewpoint held by others out of concern for presenting themselves as group members (Hsu & Lu, Citation2004).

H4: Social variables significantly influence PUT, RR and CF’s impact on OPI.

3.4. Attitude

Online shopping environments consolidate the complete sales process into a single platform, in contrast to traditional physical shopping settings, which is convenient for the consumers and also generates the attitude towards online shopping and sets the purchase intention (Baytar et al., Citation2020; Dharmesti et al., Citation2019; Mummalaneni & Meng, Citation2009). Online shopping provides consumers with greater convenience because it is open to more than time or space (Dharmesti et al., Citation2019; Gawor & Hoberg, Citation2019). However, the fact that individuals cannot physically touch, taste, or feel the tangible benefit they are acquiring online might occasionally deter consumers’ attitudes towards online shopping (Silva et al., Citation2020). Consumer attitudes are difficult to ascertain using conventional web marketing measures (Bala & Verma, Citation2018). However, attitudes—a person’s generally consistent thoughts, inclinations, and judgments toward a thing or idea—greatly influence a consumer’s purchase decision (Peña-García et al., Citation2020; Tormala & Rucker, Citation2017; Wang et al., Citation2018; Wu, Citation2003). Prior studies on attitudes in the context of online purchases have only looked at technology and customer demographics (Ahn et al., Citation2007; Lissitsa & Kol, Citation2016; Wu, Citation2003). Consumers’ perceptions and experiences regarding the advantages and disadvantages of online purchasing influence are critical enablers in setting their attitudes and intentions (Ahn et al., Citation2007; Van der Heijden et al., Citation2003; Wu, Citation2003). Millennials, in general, have a greater awareness of the advantages and disadvantages of online buying than earlier generations, and due to their propensity for being astute in avoiding the risks associated with internet buying, millennials have a favourable perception of online shopping (Obal & Kunz, Citation2013; Sorce et al., Citation2005). According to prior studies on online purchasing behaviour, attitudes regarding online shopping and intentions to purchase positively correlate (Ghosal, Citation2015; Khare & Rakesh, Citation2011; Sorce et al., Citation2005; Van der Heijden et al., Citation2003). Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H5: Attitude significantly influences PUT, RR and CF’s impact on OPI.

3.5. Perceived value

3.5.1. Website design

For any online store to attract customers, the quality of the website design is crucial (Ashraf et al., Citation2019; Rita et al., Citation2019). In their study, Cho and McCoy identified a connection between customer satisfaction in online shopping and the quality of website design. Website design is how the website’s material is structured (Ranganathan & Grandón, Citation2002). According to Wolfinbarger and Gilly (Citation2003), customers prefer to deal with an online store through the technical interface. Therefore, the interface—the website—and its design would significantly impact customers’ satisfaction, leading to purchases (Prashar et al., Citation2017). The design of websites has a beneficial impact on overall customer happiness and perceived service quality (Lee & Lin, Citation2005; Rita et al., Citation2019). Additionally, Ranaweera et al. (Citation2008) empirically tested and established that website design influences purchase intention favourably. To aid buyers in determining the quality of a product, sellers employ various cues, such as an appealing and user-friendly design for the interface of e-commerce platforms (Ganguly et al., Citation2010; Mavlanova et al., Citation2016).

H6: Website design significantly influences PUT, RR and CF’s impact on OPI.

3.5.2. Perceived quality

There needs to be a clear definition of perceived quality in the existing literature because it depends on the situation and the setting (Snoj et al., Citation2004). Zeithaml (Citation1988), one of the key authors who analyse this idea, describes perceived quality as the consumer’s approach regarding a product’s level of perfection or superiority. Additionally, he claims that it is consistent with the consumer’s mental evaluation and views perceived quality as an amorphous idea closely related to individual attitudes. Therefore, perceived quality (also referred to as subjective quality) can be described as the value judgments customers make regarding a product’s quality (Espejel et al., Citation2007). Moreover, a person’s perception of quality may vary depending on various variables, including the time they learn about a product’s characteristics, the location of the purchase, and the goods consumed (Fandos & Flavián, Citation2006). Therefore, perceived quality can be defined as the subjective evaluation that customers make of a brand, a product, or the performance of both (Salem & Alanadoly, Citation2022; Yu et al., Citation2018). As a result, consumers will judge the usefulness or functionality of a good or service based on their preferences or requirements (Fandos & Flavián, Citation2006). In conventional marketplaces, customers can directly evaluate a product’s quality using their senses by touching, testing, and visually scrutinising it (Jiang & Benbasat, Citation2004). However, in a technology-mediated market, consumers cannot assess product quality similarly, brewing uncertainty and encouraging product rejection (Wells et al., Citation2011).

H7: Perceived quality significantly influences PUT, RR and CF’s impact on OPI.

3.5.3. Price

E-commerce offers customers a visual representation of the products distinct from actual shop fronts. Given that all prices in online channels are more competitive, the price, in this case, may influence how consumers perceive the product (Reinartz et al., Citation2019). Price is viewed as a significant extrinsic value of the product’s quality in this domain; hence, there is a close relationship between price and product quality (Zhao et al., Citation2021). As per some studies, this relationship gets impacted if more options are available. Pricing continues to be a reliable signal of quality even in the presence of other external criteria like brand name (Reinartz et al., Citation2019; Zeithaml, Citation1988; Zhao et al., Citation2021). Therefore, without intrinsic characteristics in online purchases, price should usually be a positive indicator (Teas & Agarwal, Citation2000). Cost savings are acknowledged as one primary reason customers purchase online (Keeney, Citation1999). The study discussed that those online purchases result in immediate cost savings on both the product’s price and the cost of web browsing. When consumers use online shopping, they may see cheaper pricing due to more providers being able to compete in the electronically open market. (Turban et al., Citation2015).

H8: Price significantly influences PUT, RR and CF’s impact on OPI.

3.5.4. Hedonic benefits

Hedonic benefits are one of the concepts connected to affective commitment. Hedonic benefits, as opposed to affective commitment, reflect the emotional benefits that an individual experiences due to such involvement. Marketing literature categorises consumer benefits as utilitarian and hedonistic (Akram et al., Citation2021). Chandon et al. (Citation2000) state that hedonic benefits are emotive, experiential, and non-instrumental, while utilitarian benefits are cognitive, functional, and instrumental. Hedonic benefits meet customers’ emotional demands (Tyrväinen et al., Citation2020), whereas utilitarian benefits satisfy consumers’ rational expectations during a purchase (Hepola et al., Citation2020). Hedonic benefits involve motivation, satisfaction, and pleasure (Luk & Yip, Citation2008). Benefits from choosing online platforms may include both hedonic and utilitarian benefits. Hedonic benefits in a purchase setting include enjoyment from purchasing the products and surroundings of a store (in-store or online) (Carpenter & Fairhurst, Citation2005). The notions of affect heuristics can also be used to explain the role of hedonic benefits in online platforms. According to Finucane et al. (Citation2000), an effect heuristic-based decision evaluates the risks and advantages of a course of action rather than weighing them separately. It comes with more considerable hedonic benefits than risks. Therefore, utilising affect heuristics as an underpinning, it is possible to state that someone with a highly expressive online purchase intention is expected to prioritise hedonic benefits like delight, pleasure, excitement, and fun over potential risks.

H9: Hedonic benefits significantly influence PUT, RR and CF’s impact on OPI.

4. Methodology

4.1. The search process for meta-analysis

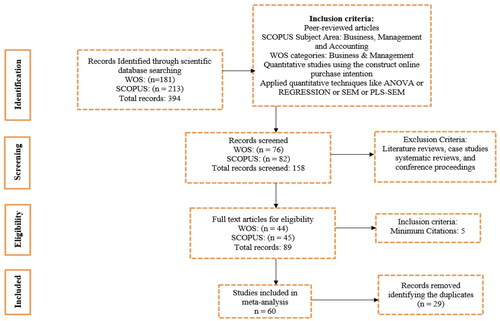

The study used a systematic search procedure across the scientific databases of Web of Science (WOS) and Scopus to find and choose the relevant studies. With a comprehensive worldwide and regional coverage of scientific journals, conference proceedings, and books and a strict content selection process, Scopus and WOS are among the largest multidisciplinary databases that curate abstracts, citation databases, and information (Pranckute, Citation2021). The reliability of both of these databases has led to their usage as the data source for extensive analysis in research assessments, landscape studies, science policy evaluations, and university rankings, in addition to enriched metadata records of scientific articles (Baas et al., Citation2020; Pranckute, Citation2021). The searched keywords are “online purchas*”, “behavio*”, “ANOVA OR REGRESSION OR SEM OR PLS-SEM” in each of these databases. The different stages of the literature search process are detailed in a PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flowchart shown in (Moher et al., Citation2009). Articles published between 2004 and 2023 were extracted for this review. A total of 394 articles were found after the initial database screening with the keywords mentioned above and operators and only considering articles on business and management as a subject. The next phase involves screening the articles by limiting or excluding the prefaces, editorials, news, opinions, reviews, and pieces written in languages other than English. This further resulted in 158 articles passing this filtration. The peer-reviewed articles with a minimum of five citations are included in the subsequent filtering round. This round of filtering could include a total of 89 records. Excluding duplicate articles during the last and final stage produced a final sample of 60 articles.

Also, the following criteria were checked while considering these studies for the meta-analysis.

The studies were empirical studies that quantitatively tested online purchase intention.

The papers must have a reported sample size.

The formulae suggested in Peterson and Brown (Citation2005) Other meta-reviews in the marketing literature used a technique described in this paper to estimate correlations from standardised regression coefficients (beta). It was based on their suggestion that the maximum number of effect sizes should be included to permit the generalisability of the findings (Blut et al., Citation2016). The formulae used are r = 0.98β + 0.05λ, where λ is a variable that equals 1 when β is nonnegative and 0 when β is negative. 13 research (21.66%) of the total 60 investigations in the data set were completed using correlation derived from the standardised beta coefficient. In contrast, 47 studies (74.8%) included reported correlation coefficients. The articles’ combined sample size is 29,139, with an average sample size of 486. shows the study selection process following PRISMA. The details of the papers are also given in the Appendix.

5. Measurement

Although the measures utilised throughout the analysed research vary, their measuring criteria and abstract concepts are broadly consistent, a method used in many meta-analyses in the marketing literature (Amos et al., Citation2014; Tan & Sousa, Citation2015). Each construct’s contents are summarised in the conceptual framework along with the scales utilised in various research and as a unified framework to ease understanding. For instance, in the conceptual framework, perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use and congruence are stated as Perceived Utility (PUT). Similarly, trust, security, perceived risk, uncertainty avoidance and fulfilment reliability are put as Reliability and Reputation (RR). e-WOM and consumer innovativeness are put together as Contextual Factors (CF). Likewise, the potential moderators were also clubbed into two groups.

Personal Factors, which also include two sub-groups

Demographic Variables (DV) comprise the constructs of Gender, Age and Income.

Social Variables (SV) are constituted of Social Identity and Social Influence.

Technology Readiness and

Attitude

Perceived value is the second group of a moderator, which includes the construct of

Website design

Perceived quality

Price

Hedonic Benefits

6. Coding procedure

From every publication, the crucial data for the study was meticulously retrieved. The author’s name, publication date, publications, analysed countries or regions, sample size, significant factors, and stated effect sizes are all key pieces of information. The notions with related meanings were grouped after considering numerous constructs with different names communicating the same notion. Following the recommendations of Rana et al. (Citation2013), only those relationships were chosen for the meta-analysis examined three or more times in the literature. Finally, 18 relationships were identified. All studies included in the meta-analysis were split into two main groups for the moderator analysis: Personal Factors (PF) and Perceived Value (PV). A few research only provided the standard regression coefficient rather than the correlation coefficient. We considered the standard regression coefficient in this instance as the effect size. Few research provided f-value. We calculated the effect size for these studies using Wolf’s (Citation1986) formula: , where F is the F-value of the path and is the degree of freedom (df).

7. Results

7.1. Descriptive analysis

A summary of the findings from the meta-analysis of the OPI antecedents is shown in . The analysis was based on 60 papers, 40 published in reputable journals. The studies were from 16 nations (Africa, Bangladesh, Brazil, Canada, India, Indonesia, Iran, Korea, Malaysia, Pakistan, Philippines, Pan-European nations, South America, Singapore, USA, and the UK). The total number of samples is 29,139. A reliability rating of 0.7 and 0.9 indicates good internal consistency for each reported antecedent of the online purchase intention construct. The integrated effect size for each element considered in the study shows medium-to-large mean effects. The Q-test result () showed considerable effect size heterogeneity, supporting, in this investigation, the random-effects model. Additionally, all the relationships have significant heterogeneity, as seen by the significant Q-values in . The DerSimonian-Laird estimator was used to create the tau2 estimator in the random-effects model. Additionally, the statistic I2 is a percentage measure of the variance between studies, indicating a sizable amount of research heterogeneity (DerSimonian & Laird, Citation1986). The correlation coefficient and sample size were utilised in the study to analyse the relationship between OPI and the factors PUT, RR, CF, PF, and PV. The random-effect model is selected to calculate the combined effect considering the sample differences. The combined effect sizes, according to Cohen (Citation1988), can be divided into three categories: small effect size (between 0.2 and 0.5), medium effect size (between 0.5 and 0.8), and big effect size (> 0.8). The findings indicate that the overall effect size of the reported studies is generally low. Additionally, the analysis’s findings indicate that there is a statistically significant correlation between each factor in the categories of perceived utility (PUT), reliability and reputation (RR), contextual factors (CF) and online purchase intention (OPI), supporting the study’s hypotheses. displays the full meta-analysis findings.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and correlational analysis.

7.2. Publication bias assessment

To assess the results’ robustness, a publication bias assessment was conducted. Three tests were run: the Rank correlation, the Failsafe N calculation, and Egger’s regression. To evaluate the publishing bias, Failsafe N is reported for each relationship (Kraemer & Andrews, Citation1982; Rosenthal, Citation1979). These studies show no publication bias. and presented the test findings. A publishing bias evaluation was conducted to demonstrate the results’ reliability. A fail-safe N was determined for each association, calculating the number of studies that would need to be unavailable or inconsequential to reduce the cumulative effect size to a non-significant value. The "file drawer problem" is what this means (Rosenthal, Citation1979). The fail-Safe N for each of the

Table 2. Publication bias assessment.

Combined effect sizes are shown in . For the perceived usefulness - OPI relationship, a fail-safe N of 32,586 suggests that more than 30,000 studies presenting null results would be required to meet the just significant level (α = 0.05). Even the lowest number of N (838) for the relationship between fulfilment reliability and OPI is very high, indicating that it is unlikely that the mean effect sizes for each of these taken-into-consideration factors will be zero.

Additionally, Egger’s regression test (Egger et al., Citation1997) and the rank correlation test (Begg & Mazumdar, Citation1994, p. 1088) were used to determine objective measures of potential bias. Table C above represents the p-values for the tests in each case. For most cases, neither the rank correlation nor Egger’s regression test was statistically significant. Except for perceived ease of use, Egger’s p-value = 0.022 and rank test p-value = 0.047. The extremely low likelihood of publishing bias is implied by the elevated fail-safe N of 12,809. Overall, these tests have not found any significant evidence of publication bias.

8. Moderator analysis

Further, the researcher also analysed the variables that might have moderated the impact of each of these antecedents on OPI.

8.1. Univariate meta-regressions

Univariate meta-regressions are performed as suggested in earlier meta-analytical investigations (Massey et al., Citation2018; Wood et al., Citation2015). For each of the eight remaining antecedents in the two major categories of PF and PV, univariate meta-regressions were used to account for potential moderators that might be used to explain the difference in effect sizes. The moderators tested were (1) Demographic variables, (2) Social variables, (3) Technology Readiness, (4) Attitude, (5) Website Design, (6) Perceived Quality, (7) Price, and (8) Hedonic Benefits. To find additional effects beyond the given hypotheses, each of these moderators was evaluated for the three antecedent groups of Perceived Utility (PUT), Reliabilty and Reputation (RR) and Contextual Factors (CF).

8.2. Results

The outcomes of the univariate meta-regressions are presented in . The findings followed the moderating effects suggested in hypotheses H2, H3, H4, H5, H6, H7, H8, and H9. The summary of supported and non-supported hypotheses is shown in . An interesting finding was identified through the analysis of the study factors that were used as moderators. The Demographic variables, the cumulative aggregation of Gender, Income and Age, are not supported as the moderator. However, other antecedents such as Technology Readiness, Attitude, Perceived Quality, Hedonic Benefit and Website Design appear to be strong moderators that created a more visible impact on the OPI. Moreover, the other moderators, such as Price and Social Variable, which again is a cumulative integration of social identity and social influence, also significantly impact the OPI ().

Table 3. Moderation analysis.

9. Discussion

The current meta-analysis provides a quantitative consolidation of the antecedents of OPI. Online purchase has become an everyday phenomenon in our daily lives owing to many conveniences offered by various online platforms (Deng et al., Citation2021); a meta-analysis will help to understand and identify the patterns in online consumption. It can act as a symbolic driver, providing a foundation for comprehending heterogeneous online shopping motivations across the globe. Based on 60 selected prior empirical studies on online purchase behaviour/intention influencing factors. This study used a meta-analysis to investigate the 18 key variables influencing online purchasing intent. The identified factors considered and analysed in this meta-analysis study are the factors that emerged multiple times in the prior studies considering this subject. A correlation analysis is performed in the first stage of meta-analysis, where each factor considered in the study’s conceptual framework (as shown in ) is tested to check the statistical significance with OPI. The result presented in depicts that each of the factors under the three categories of Perceived Utility (PUT), Reliability and Reputation (RR) and Contextual Factor (CF) are supported and state that they are positively and significantly impacting the Online Purchase Intention (OPI).

H1a–H1c considered the overall utility and how a consumer perceives online shopping/purchase as applicable. The factors under this category are perceived usefulness, ease of use and congruence. These factors were sufficiently considered in the prior studies (Badrinarayanan et al., Citation2014; Law et al., Citation2016; Moslehpour et al., Citation2018) and looked for in detail to get an in-depth understanding. The study’s hypotheses’ significant results are consistent with previous studies. Overall, the factors under the Perceived utility categories are the most fundamental factor that builds up a strong foundation of intention to purchase online.

H1d–H1h considered the overall Reliability and reputation of the online platform and the online shopping experience. If customers can rely on online platforms regarding security, trust, and risk, they find the platform more reliable. Also, factors such as uncertainty avoidance and fulfilment reliability are essential as they generate the impression/reputation of the platform. Suppose the consumer is satisfied with how the online channels mitigate the hazard/threat and how the business can deliver the order accurately and on time. These are crucial determinants in an online business and are an important deciding factor impacting online purchase intention. The significant impact of each factor very neatly depicted the study’s consistent reporting with the prior studies (Katta & Patro, Citation2017; Nath & Murthy, Citation2004; Peinkofer et al., Citation2016; Zhao et al., Citation2017).

H1i–H1j discusses the external/contextual factors that can effectively contribute to online purchase intention. The factors considered under the Contextual Factors (CF) category are e-WOM and consumer innovativeness. Customer online reviews are critical to creating a perception of the product or the online site (See-To & Ho, Citation2014). Previous studies have discussed the impact of online reviews or e-WOM on purchase intention (See-To & Ho, Citation2014; Zhang et al., Citation2020). Here, it is clubbed together with consumer innovativeness as the e-WOM, in many ways, also establishes the initial trust of the customer in the new product; hence, both these factors act as an external push for the purchase online. Moreover, the hypotheses support that the external push or the contextual factors significantly determine the intent to purchase online, which is also a consistent finding concerning the prior studies.

Finally, the moderator analysis is performed to understand and validate the indirect effect of study variables on OPI. Here again, the study’s moderators are also well-established moderators of multiple studies in this domain and hence put together to get a crisp and clear picture. The moderators were divided into Personal Factors (PF) and Perceived Value (PV) categories.

In the category of PF, we have again subcategories of Demographic Variables (DV), which comprises Gender, Age and Income, and Social Variables (SV), including social identity and social influence. H2 & H4 test the indirect effect of these factors on the OPI. Here, H4 (Social variables) supports their significant impact indirectly on the OPI, and H2 (Demographic variables) came non-significant. While prior studies (McCloskey, Citation2006; Al-Somali et al., Citation2009; Shaouf & Altaqqi, Citation2018) have reported the moderating effect of gender, Age, and income individually on the OPI, clubbing them together creates a significant difference in the magnitude of the factors. The combined effect size of –0.031 of this study factors signifies that all of them together as DV, not impacting the OPI.

H3 & H5, under the category of PF, put forth the technology readiness and attitude of the consumer towards OPI. Both these hypotheses have suggested a significant impact on OPI, and we can easily conclude that technology adaptiveness and attitude indirectly impact the OPI in line with the implications drawn by the previous studies (Lee & Wu, Citation2017; Parasuraman, Citation2000).

Moving to the category of PV, we have factors such as website design, perceived quality, price, and hedonic benefit under hypotheses H6–H9. All these hypotheses supported the factors’ indirect effect on the OPI. Interestingly, in this study, all these factors were categorised into Perceived Value (PV), which is assumed to bring a certain amount of value to the online shopping experience, leading to purchase. So, when a customer thinks about the value of the purchase, then price and quality are significant. However, the experience of the purchase also counts meaningfully. The website design and the pleasure derived through the shopping experience add to the value proposition, fulfilling the OPI significantly.

Thus, all the study hypotheses have justified their significance and relevance being considered and tested in the study, thus validating the study variables.

10. Theoretical and managerial implications

10.1. Theoretical implications

Consumer behaviour researchers from all around the globe have paid close attention to studies on online purchases/buying. In the current meta-analysis research on online purchase intention, the online scenario was primarily emphasised, and only a few studies included the distinctive features of comparison with the offline scenario. This study looks into the gap in the literature by concentrating on the factors that can be considered as possible antecedents that influence the intention to make an online purchase. Meanwhile, this study has broadened OPI's range of influences. This study included 60 empirical papers in a meta-analysis. To remove the research bias brought on by conflicting findings in the current research results on online purchase intention, it suggested a comprehensive framework of the influencing elements of online purchase intention based on quantitative statistical analysis. Eventually, the criteria were narrowed to 18 concepts, and the study variables were those examined three or more times in the research articles. These variables were further classified into five categories: Perceived Utility (PUT), Reliability and Reputation (RR), Contextual Factors (CF), Personal Factors (PF) and Perceived Value (PV).

The meta-analysis examining online purchasing intention offers a fresh approach to the studies in this domain. This study explores studies from researchers across the globe with a large sample size with an average sample of 486. It helps understand in-depth the implication of the study variables in detail. This meta-analysis helps identify the critical theories and constructs used in various studies on online purchase intention. It segregates them, giving them a unique structure and also helps to identify them. Conceptualising the study variables and studying them helps us comprehend that most studies have used TAM, TPB, TRA and UTAUT as their foundational theories (Fogel & Schneider, Citation2010; Keisidou et al., Citation2011; Akhlaq & Ahmed, Citation2015; Dewi et al., Citation2019; Kaur & Thakur, Citation2019). Although few studies have also discussed the amalgamation of some other theories along with these theories (Bianchi & Andrews, Citation2012; Wen, Citation2012; San-Martín et al., Citation2020), they form the core of most studies researching the OPI. In recent times, where Artificial Intelligence (AI) based technology has been the core of online platforms and enhancing customer experiences, it is imperative to assess and relook at the variables. On top of that, consumers of recent times are also more experienced with online platforms, owing to the pandemic; hence, relooking the existing frameworks has been of utmost importance. This study has aggregated the widely used variables of recent times that govern the OPI and recalibrated them to provide a more robust framework. The framework tested and established in this study will add to the existing theories, helping the researchers get a more holistic understanding due to a new normal period. Trust, risk, perceived value, ease of use, usefulness, attitude, easy website navigation, social references and many more have always been the driving force towards OPI. However, classifying them as homogenous categories and validating them with appropriate quantitative methods is an innovative perspective of this study. These categorisations of variables as PUT, RR, CF, PF and PV are also relevant in the era of smart technologies and add more relevance to the post-pandemic times. Existing studies and theories have investigated the interactive effects individually. Contrarily, the fine-tuned aspects of the variables used in this meta-analysis study acknowledge the complexity of the consumer decision-making process and support the cumulative impact of the identified categories on present-day consumers and their purchase intentions. These concepts can serve as a foundation for creating modern scales. The current paper also provides definitions of perceived utility, reliability and reputation, contextual factors, perceived value, and personal aspects that may help future research have greater conceptual clarity, adding value to the prior conceptual and empirical findings.

10.2. Managerial implication

This study identifies the key global factors and offers in-depth insights into the variances in consumer online shopping behaviours. For brand managers, market segmentation is a crucial subject of interest. Managers can use the current meta-analytic evaluation to guide market segmentation and identify the symbolic factors influencing online purchasing intentions. Such expertise is more important than ever, given that markets are expanding globally, businesses are adapting in the wake of the pandemic, and the Internet has become essential to every consumer’s life. Marketing managers can adapt or standardise their worldwide marketing strategy by being thoroughly aware of the factors that drive online purchasing habits across growing and developed regions. This study’s key points and conclusions may have various managerial implications for online businesses. Here are some significant ramifications:

Enhancing user experience: Understanding the characteristics that affect online purchase intention, such as usability and engagement, can be accomplished by meta-analysing several research. Managers can use these results to enhance the user experience overall and influence purchase intention.

Building credibility: Online purchase decisions are heavily influenced by dependability and reputation variables, including security, trust, fulfilment reliability, risk avoidance, and uncertainty avoidance. In the current era of innovative technologies like AI-embedded services, the study proposed a category of Reliability and reputation that can assist firms in identifying the credibility-building tactics most effectively influencing purchase intention. Reliability concerns can aggravate concerns about security, trust, and consumer expectations, just like with AI-based smart services. Businesses can use these insights to improve website credibility and strengthen purchase intent.

Targeting marketing efforts: The meta-analysis review identified variables, such as online reviews or e-WOM and consumer innovativeness tactics while handling the product in an online platform, that substantially impact online purchase intention. Marketers can use these contextual variables to create specialised social media marketing promotions and discounts. By concentrating on the tactics that have the most significant influence on purchase intention, this information can assist managers in more effectively allocating marketing resources.

Personalisation and Customisation: Businesses tailor and customise their services depending on client preferences by understanding the elements that drive online purchase intention. In the age of smart technologies, where these factors can be replicated to build and integrate hyper-personalisation, the meta-analysis review helped identify specific attributes or features that drive purchase intention, allowing managers to tailor their products or services more specifically and increase the likelihood of conversion.

Managing customer expectations: The dimension of perceived value identified in this study can assist businesses in aligning their offerings with customer expectations and, in turn, exceed those expectations by delivering high-quality goods and services, enhancing the pleasure and joy of the online shopping experience, and optimising delivery processes.

Mobile optimisation: As more people use mobile devices for online purchasing, meta-analysis can shed light on the elements affecting consumers’ decision-making, specifically on mobile platforms. Based on these findings, businesses can develop mobile-specific apps or optimise their websites for mobile users to improve the mobile shopping experience and strengthen purchase intent.

In general, managers can benefit from a meta-analysis study on online purchase intention to make wise choices on website design, trust-building tactics, marketing initiatives, personalisation, customer expectations, influencer marketing, and mobile optimisation. Businesses may improve their online presence and marketing strategy to boost client engagement and conversion rates by comprehending the significant factors influencing purchase intention.

11. Limitations and future propositions

A meta-analytic review can point out critical gaps in the incorporated literature. Several limitations apply to this study, which is detailed in this section.

Although limited by the exclusion of a few studies, considering the strict inclusion requirements, the sample size is equivalent to that in past meta-analysis papers.

Even though other factors may potentially have a substantial impact, this study concentrated on the determinants of online purchase intention because they had been the focus of the majority of studies in the meta-analysis. Future research may examine more factors.

This study is limited to a few specific quantitative methods. Future research can examine if it would be possible to conduct meta-analyses, especially on experimental studies. More robust evidence on the effects of interventions or manipulations on online purchase intention is provided by experimental designs since they allow for better control of variables and causal conclusions.

The meta-analysis only used quantitative studies. The incorporation of qualitative studies in weight analysis, which assesses the relationship between antecedents and consequences, should be considered in future research. Analysing intricate interactions between variables can be made possible by including structural equation modelling (SEM) in meta-analyses. Researchers can explore the underlying mechanisms and pathways that affect online purchase intention using SEM methodologies, giving them more in-depth insights into how various elements interact.

One significant limitation of this study is that it needs to consider the consequences of cross-platform and multichannel usage. Online shopping activity frequently happens across several platforms and channels. Future meta-analyses can examine the effects of cross-platform and multichannel interactions on the likelihood of online purchasing. By integrating studies that examine the impact of components across various platforms and channels (such as websites and mobile applications), researchers can provide insights into the complexities of the online consumer experience (such as social media and email marketing).

The fact that this study ignored changes in online purchase intention over time and in response to various stimuli is another one of its limitations. Future meta-analyses can explore the dynamic and time-varying impacts by incorporating articles that look at changes in online purchase intention under various circumstances or interventions. The temporal dynamics and fluctuations in consumer behaviour can be identified using this.

Future research could analyse how developing technologies affect the desire to purchase online in light of ongoing technological improvements. This involves looking into how technologies like virtual reality, AI, blockchain, and Internet of Things (IoT) gadgets have an impact. In this fast-developing subject, meta-analyses might aid in combining and synthesising the results from various investigations.

Cultural norms, values, and variables can affect the intention to purchase online. Future meta-analyses incorporating research from other nations and areas can investigate cross-cultural variations. This would give insight into how cultural influences influence the intention to make an online purchase and assist in identifying cultural similarities and variances.

Online purchasing experiences are significantly influenced by personalisation and recommendation algorithms. Meta-analyses can examine how tailored recommendations, product customisation, and targeted advertising affect the likelihood of an online purchase. This would make it easier to determine how well these strategies work and how they affect customer behaviour.

Authors’ contributions

The whole article is the sole author’s work

Consent for publication

I, Munmun Ghosh, give my consent for information about myself to be published in the Journal.

Appendix_RV1.docx

Download MS Word (51.4 KB)Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the journal, editor, reviewers and my organisation for supporting my work and allowing me to conduct my research.

Disclosure statement

No competing interests.

References

- Adnan, H. (2014). An analysis of the factors affecting online purchasing behavior of Pakistani consumers. International Journal of Marketing Studies, 6(5), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijms.v6n5p133

- Agarwal, J., & Wu, T. (2018). ECommerce in emerging economies: A multitheoretical and multilevel framework and global firm strategies. In J. Agarwal, & T. Wu (Eds.), Emerging issues in global marketing: A shifting paradigm (pp. 231–253). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/9783319741291_9

- Ahn, T., Ryu, S., & Han, I. (2007). The Impact of Web Quality and Playfulness on user acceptance of online retailing. Information & Management, 44(3), 263–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2006.12.008

- Akhlaq, A., & Ahmed, E. (2015). Digital commerce in emerging economies: Factors associated with online shopping intentions in Pakistan. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 10(4), 634–647. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJoEM-01-2014-0051

- Akram, U., Junaid, M., Zafar, A. U., Li, Z., & Fan, M. (2021). Online purchase intention in Chinese social commerce platforms: Being Emotional or Rational? Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 63, 102669. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102669

- Al-Jundi, S. A., Shuhaiber, A., & Augustine, R. (2019). Effect of consumer innovativeness on new product purchase intentions through learning process and perceived value. Cogent Business & Management, 6(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2019.1698849

- Allard, T., Babin, B. J., & Chebat, J.-C. (2009). When income matters: Customers evaluation of shopping malls’ hedonic and utilitarian orientations. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 16(1), 40–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2008.08.004

- Al-Somali, S. A., Gholami, R., & Clegg, B. (2009). An investigation into the acceptance of online banking in Saudi Arabia. Technovation, 29(2), 130–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2008.07.004

- Alvarez-Risco, A., Quipuzco-Chicata, L., & Escudero-Cipriani, C. (2021). Determinants of online repurchase intention in COVID-19 times: Evidence from an emerging economy. Lecturas de Economía, 96(96), 101–143. https://doi.org/10.17533/udea.le.n96a342638

- Amos, C., Holmes, G. R., & Keneson, W. C. (2014). A meta-analysis of consumer impulse buying. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 21(2), 86–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2013.11.004

- Ashraf, N., Faisal, M. N., Jabbar, S., & Habib, M. A. (2019). The role of website design artifacts on consumer attitude and behavioral intentions in online shopping. Technical Journal, 24(02), 50–60.

- Ashraf, A. R., Thongpapanl, N. ()., & S., Auh. (2014). The application of the technology acceptance model under different cultural contexts: The case of online shopping adoption. Journal of International Marketing, 22(3), 68–93. https://doi.org/10.1509/jim.14.0065

- Awad, N. F., & Ragowsky, A. (2008). Establishing trust in electronic commerce through online word of mouth: An examination across genders. Journal of Management Information Systems, 24(4), 101–121. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40398913 https://doi.org/10.2753/MIS0742-1222240404

- Azizi, S., & Javidani, M. (2010). Measuring e-shopping intention: An Iranian perspective. African Journal of Business Management, 4(13), 2668–2675.

- Baas, J., Schotten, M., Plume, A., Côté, G., & Karimi, R. (2020). Scopus as a curated, high-quality bibliometric data source for academic research in quantitative science studies. Quantitative Science Studies, 1(1), 377–386. https://doi.org/10.1162/qss_a_00019