Abstract

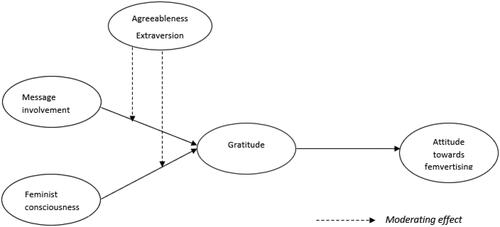

The raised awareness of women’s rights has resulted in their significant contribution to economic and societal advancement in the contemporary global paradigm. The promotion of female empowerment by various corporations has led to the emergence of femvertising as a significant trend in the media. The current research attempts to empirically examine the relationship between the message involvement of consumers and their attitude towards femvertising. The present study further investigates the potential mediating role of gratitude in the relationship between message involvement and attitude towards femvertising among consumers. Moreover, this study provides additional evidence supporting the notion that gratitude serves as a mediator in the association between feminist consciousness and attitude towards femvertising. In addition, the moderating influence of personality traits, specifically extraversion and agreeableness, on the indirect association between message involvement/feminist consciousness and attitude towards femvertising through the mediating mechanism of gratitude has been tested. The data collection process involved the utilization of a survey instrument, while the hypotheses were subjected to testing through the use of PROCESS macros for SPSS.

Reviewing Editor:

Introduction

Advertising has emerged as a significant medium for generating awareness and addressing social issues. The increasing pressure from consumers has prompted numerous business organizations to respond positively and align themselves with socially conscious consumers and other stakeholders in order to address social issues through advertising (Champlin et al., Citation2019; Moorman, Citation2020; Patel et al., Citation2017; Taylor et al., Citation2016). By utilizing advertising imagery, businesses have the ability to establish a favorable association between their brand and pertinent societal concerns, thereby augmenting their capacity to reach a wider audience (An & Kim, Citation2007). The utilization of brand activism by business organizations can serve as a crucial mechanism in raising awareness regarding pertinent social issues, including but not limited to environmental concerns, racism, and gender equality (Ganz & Grimes, Citation2018; Li et al., Citation2020; Middleton & Turnbull, Citation2021). To address gender equality, primarily female empowerment, femvertising has emerged as a significant facet of advertising in recent times (Åkestam et al., Citation2017; Castillo, Citation2014), garnering substantial attention from organizations as a crucial component of brand activism (Dans, Citation2018; Drake, Citation2017; Kapoor & Munjal, Citation2017). The motivation for business organizations take a stance against gender-based injustice and adhere to a set of core values, rather than solely pursuing capitalistic motives, can be ascribed primarily to the expectations of consumers (Abitbol & Sternadori, Citation2020; Bissell & Rask, Citation2010; Pérez & Gutiérrez, Citation2017). Against this backdrop, femvertising not only enables businesses to combat the stereotypes and prejudices connected with women, but also aids them in attracting and retaining customers by enhancing their sense of accomplishment and affirmation (Sobande, Citation2019; Sterbenk et al., Citation2022).

The feminist movement has prompted advertisers to reexamine the traditional portrayal of women as subordinate, decorative, and objectified individuals (Feng et al., Citation2019). As a result, a shift towards more empowering representations of women has been observed in the advertising industry over the past decade (Cheng & Wan, Citation2008; Grau & Zotos, Citation2016; Varghese & Kumar, Citation2022). The utilization of power portrayals has been found to be effective in altering the mindset of consumers (Turner & Maschi, Citation2015). Specifically, research revealed that commercials that promote female empowerment have the ability to enhance customers’ perception of corporate social responsibility, thereby leading to a more favorable attitude towards the advertisement (Teng et al., Citation2021). The growing scholarly attention towards Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) (Kotler & Lee, Citation2005), and the integration of progressive social concerns in contemporary capitalist communication culture have led to a surge in research on femvertising (Campbell, Citation2007; Champlin et al., Citation2019; Taylor et al., Citation2016). Gender progressive advertising initiatives are predicated on the reliance of popular consumer opinions and the moral conscience of advertisers (Eisend et al., Citation2014). Consequently, innovative marketing logics are engendered, which serve to facilitate the success of these pioneering advertising campaigns (Middleton & Turnbull, Citation2021). Petty and Cacioppo (Citation1996) assert that brands utilize persuasive communication tactics to capture the interest of consumers and effectively involve them with the message, resulting in a profound consideration of the advertisements. The foremost aim preceding the anticipated consequences of advertising, such as purchase intent and word of mouth, is to captivate the audience’s attention to efficiently comprehend advertisements that are linked to message effects, including ad recall or advertising message involvement (Wang, Citation2006; Wojdynski & Evans, Citation2020).

The level of involvement with advertising messages can exert a prompt impact on consumers following message exposure, potentially resulting in attitudinal and behavioral consequences (Bartsch & Kloß, Citation2018; Krugman, Citation1965). Various research models have been developed to investigate message involvement in advertising research. According to prior research, the level of ad message involvement in green advertising has a notable impact on both brand attitude and purchase intent (Yu, Citation2021). Similarly, previous research in context of charity marketing also demonstrated that a heightened level of involvement with advertising messages could result in an increased propensity to make donations (Van Steenburg & Spears, Citation2021). Despite the existence of a well-established body of literature on the function of advertising message involvement in various ad appeals, the motivational construct of advertising message involvement has yet to be examined in relation to femvertised ads. In the same vein, while the research in femvertising has witnessed extensive investigation of constructs like, brand-cause fit, self-consciousness and hostile sexism, a significant gap remains in understanding the role of feminist consciousness in shaping the consumers behavior (Abitbol & Sternadori, Citation2019; Champlin et al., Citation2019; Kapoor & Munjal, Citation2017; Teng et al., Citation2021). In the light of this context, inclusion of feminist consciousness as a main construct is imperative to comprehend the intricate consumer dynamics that underlie their responses to femvertised advertising.

Drawing on the extant literature, a number of significant factors have been examined in relation to femvertising such as the mediating effect of presumed influence on others, ad reactance, and brand loyalty on brand related outcomes (Abitbol & Sternadori, Citation2019; Åkestam, Citation2018). Prior research has examined the potential of femvertising to elicit positive emotions (Kapoor & Munjal, Citation2017). Given this, it is reasonable to posit that consumers may experience feelings of gratitude (Septianto & Garg, Citation2021). Gratitude is a positive moral and emotional response that arises from the constructive actions of companies (Kim & Park, Citation2020). Drawing on the social judgement theory, it is reasonable to suggest that consumers may experience a sense of gratitude towards companies that actively advocate for social issues such as gender equality. This gratitude towards socially responsible companies may have an impact on various consumer outcomes (Kim et al., Citation2018). Gratitude felt by consumers because of company’s female empowering advertising campaigns is due to the perceived relevance and consistency of the brands messages with that of consumer values (Romani et al., Citation2013). Consequently, the present study aims to investigate the mediating role of gratitude in the relationship between message involvement, feminist consciousness and attitude towards femvertising is studied.

Furthermore, the investigation also incorporated an examination of the moderating influence of personality traits. This is a crucial aspect of comprehending the fundamental cognitive processes of consumers, which in turn facilitates an understanding of their reactions to advertising communication. The examination of personality traits is deemed essential in comprehending advertising tactics that align with the personality of the target audience (Hirsh et al., Citation2012; Petty & Cacioppo, Citation1996; Ruiz & Sicilia, Citation2004; Uribe et al., Citation2022). The analysis of personality traits within the aforementioned scenario will yield valuable insights into the development of effective message design strategies that are tailored to the individual characteristics of the intended recipient. The impact of personality traits on consumers’ attitudes, behavior, and beliefs has been demonstrated to be significant (Han et al., Citation2018; Landers & Lounsbury, Citation2006). Subsequently, agreeableness and extraversion are two personality traits that signify a positive orientation towards other individuals, among other traits (Carlo et al., Citation2005). The previously suggested processes that are believed to enhance prosocial ideas and acts have been found to be associated with agreeableness and extraversion (Habashi et al., Citation2016; Snippe et al., Citation2018). The direct correlation between extraversion and agreeableness and the promotion of altruistic concepts in advertising has been observed previously (Tang & Lam, Citation2017), the current investigation contributes to the extant literature by examining the moderating impact of agreeableness and extraversion personality traits on individuals’ Attitude towards femvertising.

The current study aims to close a gap in the literature by illuminating how people’s attitudes toward femvertising are influenced by their involvement in advertising messages (Grau & Zotos, Citation2016; Varghese & Kumar, Citation2022). This study builds upon previous research that has explored the relationship between self-identified feminists and their positive attitudes towards femvertising, as driven by emotions (Kapoor & Munjal, Citation2017; Sternadori & Abitbol, Citation2019). Specifically, this study seeks to investigate the impact of consumer feminist consciousness, which refers to an individual’s awareness of gender equality (Cook, Citation1989; Duncan, Citation2010; Sowards & Renegar, Citation2004), adding to the literature on advertising, consumer behaviour and feminism.

Theory and hypothesis development

The current study, which relies on the theory of social judgment (SJT), argues that when people encounter advertising messages, they assess them in the context of their underlying attitudes and then categorize them according to their perceived level of acceptability (Sherif & Hovland, Citation1961). It goes on to say that, communications that mirror people’s initial attitudes have a greater impact on them (Freedman, Citation1964; Whittaker, Citation1965). This is known as the "latitude of acceptance" regarding social judgment theory (Arora, Citation1985; Siero & Doosje, Citation1993; Smith et al., Citation2006). So perceptions and the corresponding attitudinal shift in the context of femvertised ads may be explained by studying an individual’s involvement with and feminist consciousness toward a femvertised message.

Gratitude

Only recently have marketing academics recognized the importance of gratitude in everyday life experiences, making it a critical aspect of building a positive brand association (Huggins et al., Citation2020; Mishra, Citation2016; Palmatier et al., Citation2009). Gratitude is a state of mind that inspires moral sensibility and is the foundation for mutual connection between a sender and a recipient (Kim & Park, Citation2020). Marketing scholars have addressed gratitude in the context of CSR and relationship marketing in the consumer behaviour literature, yet they overlooked the role of gratitude in advertising (Bock et al., Citation2018; Bridger & Wood, Citation2017). The concept of gratitude has been subject to further theoretical exploration, with particular emphasis on four distinct facets, intensity, frequency, span, and density, as posited by McCullough et al. (Citation2002). Individuals who exhibit gratitude experience heightened positive affect with greater frequency, duration, and intensity, ultimately leading to a more favourable outcome. Prior research proposed a novel perspective on gratitude, which extends beyond the conventional notion of experiencing positive emotions in response to benevolent acts from others. Rather, their approach emphasizes recognizing and appreciating the positive aspects of one’s life that contribute to personal well-being (Wood et al., Citation2010). Previously, gratitude is characterized as an adaptive sensation that arises when a person receives a favorable outcome because of situational actions taken by external entities (McCullough et al., Citation2001). In this context, it is noteworthy that when consumers and corporations reach an agreement, it can increase the consumers’ sense of gratitude towards the brand. This is because the brand is perceived as committed to values that align with the consumers (Wannow et al., Citation2023; Xie et al., Citation2015). Consequently, several studies confirm that when brands take a stand on sociopolitical issues, it is likely that the positive moral emotions generated by meaningful brand actions result in consumer’s positive shift toward the brand and related outcomes (Romani et al., Citation2013; Thomson & Siegel, Citation2017; Xie et al., Citation2015;). As a result, we suggested that in reaction to femvertised advertising depicting progressive gender concepts, a consumer might feel grateful to the company for championing societal issues through their brand communication.

The mediating role of gratitude between message involvement and attitude towards femvertising

Advertising specifically encompasses the consumer’s involvement with the advertising’s media, message and creative components (Spielmann & Richard, Citation2013). Message involvement is "a motivational construct that influences consumers’ motivation to process information at the time of message exposure" (Baker & Lutz, Citation2000). It is experienced as a distinct condition elicited by a specific message at a certain time (Andrews et al., Citation1992; Batra & Ray, Citation1986; Laczniak et al., Citation1989; Zaichkowsky, Citation1985). Greenwald and Leavitt (Citation1984) framework elaborated on audience involvement in advertisements by introducing psychological theories of attention and audience processing levels. The four classified stages were pre-attention, focal attention, comprehension, and elaboration. Given that, message involvement reflects active consumer engagement and attentiveness towards the message content and the information provided in the ad. When consumers are highly involved in advertising messages, they are more likely to interpret and comprehend messages, resulting in stronger cognitive processing and attitudinal effects (Schmidt & Eisend, Citation2015). Previous research has shown that advertising message involvement increases consumers’ drive to proceed through information, stimulating consumers to develop a favourable attitude toward persuasive marketing messages (Andrews et al., Citation1990; Kwon & Nayakankuppam, Citation2015; Lee, Citation2000).

The said approach involves utilizing the message involvement construct to capture the interactive responses of consumers to brand actions, including marketing content and advertising.

The present investigation centers on message involvement, emphasizing the substance of the advertising message as opposed to particular products. The concept of involvement in advertising research has been widely utilized to elucidate the consumer’s reaction to advertisements (Belanche et al., Citation2017; Fernando et al., Citation2016). Prior research has utilized message involvement as an independent variable to forecast attitudes towards direct-to-consumer and green advertising (Fernando et al., Citation2016; Varnali et al., Citation2012). Message involvement is important in marketing research as it pertains to the consumer’s relevance to a particular issue, product, or campaign. This factor shapes the consumer’s information processing, decision-making, and behavioural outcomes (Greenwald & Leavitt, Citation1984; Laczniak et al., Citation1989; Li et al., Citation2020; Petty & Cacioppo, Citation1996).

Consequently, it is posited that the scope of message involvement in femvertising initiatives may impact consumers’ attitudes towards the femvertised ad. The present study posits that increased message involvement among consumers concerning brand communication that promotes social causes may engender cognitive processing of the content, fostering a greater appreciation for the brand’s initiatives about social issues such as female empowerment. Consequently, the favourable affective reaction elicited by advertising content augments the consumer’s general disposition towards female-empowering advertisements. The present study posits that gratitude is a good stimulus that facilitates consumers’ cognitive processing and attitude formation.

H1: Consumer’s feelings of gratitude will mediate the relationship between message involvement and attitude towards femvertising

Feminist consciousness

Much of the critic on women’s objectification or suppressed role portrayal in advertisements came from the advocates of feminist perspectives (Taylor et al., Citation2016). Evidence suggests that a person’s level of feminist consciousness determines how they perceive women’s roles in media and that feminist consciousness displays an individual’s sense of autonomy from stereotypical societal characteristics (Ford & LaTour, Citation1996; Ford et al., Citation1999; Paek et al., Citation2011). Advertisements showcasing social movements are seen to aid in establishing and developing identity and consciousness, as well as being a component in keeping the movement’s purpose alive (Choi et al., Citation2020; Taylor et al., Citation2016). Customers’ lifestyles are often reflected in advertisements, as the goal is to engage the customer and shape future purchasing patterns through strategic communication (Stern, Citation1992). Advertisers have been criticized by feminists for commodifying feminist values for financial benefit, leading to the terms like faux activism, femwashing, and genderwashing (Hainneville et al., Citation2022; Pérez & Gutiérrez, Citation2017; Walters, Citation2021). In contrast, the Dove real beauty campaign aided in societal transformation by promoting feminist awareness and consciousness towards body positivity, preventing stereotypical beliefs about women’s bodies, and fostering positive associations with self-care and acceptance (Johnston & Taylor, Citation2008). Earlier femvertising research has shown that self-identifying feminists and self-conscious consumers are extremely receptive to femvertised adverts (Kapoor & Munjal, Citation2017; Sternadori & Abitbol, Citation2019), however there is a clear gap in addressing the effect of feminist consciousness on individuals’ attitudes toward femvertising. Feminist consciousness is equated with an individual’s knowledge of inequities in gender relations, as well as an awareness of the need for structural changes to promote more gender equality, and also perhaps supporting imageries and activism aimed towards women’s empowerment (Sweetman, Citation2013). As feminist consciousness expands the horizon and overturn, the normative beliefs that controls and stereotypes the appearance of women (Cornwall, Citation2016) hence the ads promoting female empowerment would be well received and a positive attitude towards such adverts can be predicted.

Given that, felt gratitude is a positive emotion evoked as a result of a company’s commitment to a social cause (i.e., femvertising), it is suggested that consumers who are grateful are more likely to have a positive attitude toward femvertising. More involved individuals in the message content and those having feminist consciousness would have positive attitude towards ad when their cognitive emotions are stimulated by the feeling of gratitude. As a result of the theoretical framework outlined above, the following hypothesis have emerged.

H2: Consumer’s feelings of gratitude will mediate the relationship between feminist consciousness and attitude towards femvertising

Moderating role of agreeableness and extraversion

Personality traits are cognitive, emotional, and behavioral tendencies that remain consistent across time and in a variety of settings (Hampson, Citation2012; Mowen et al., Citation2004; Shaffer, Citation2000). These traits are critical part of a person’s behavior because they govern one’s values, actions, and attitudes (Landers & Lounsbury, Citation2006; Myers et al., Citation2010). Personality is operationalized as "the dynamic organization within the individual of those psychophysical systems that determine his/her unique adjustments to his/her environment" (Allport, Citation1937, p. 48). Conveniently, Costa and McCrae (Citation1995) big five personality traits have received worldwide recognition and are regarded as a coherent framework for determining an individual’s personality (Goldberg & Saucier, Citation1995; Wiggins & Trapnell, Citation1997). The five personality traits are: extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, openness, and neuroticism. Adapting persuasive communication according to the personality traits of the viewers can highlight the latent worth of personality-based communication tactics while increasing the message impact in an effective method contributing towards a positive attitude towards advertisements (Dodoo & Padovano, Citation2020). Additionally, studying the moderating influence of personality traits in the context of prosocial advertising research can have important ramifications, especially when the two personality qualities in question, extraversion and agreeableness, are studied. While extraversion reflects cheerful, gregarious, sociable and enthusiastic trait the agreeableness refers to good natured, empathetic, forgiving and soft-hearted person who is warm and considerate (Brown et al., Citation2002; Graziano & Eisenberg, Citation1997; Martins, Citation2002; Trapnell & Wiggins, Citation1990). People who are agreeable are sensitive to others’ prosocial behavior (Habashi et al., Citation2016). Prosocial acts are evaluated more positively by agreeable people, while antisocial behaviors are judged more adversely (Kammrath & Scholer, Citation2011). Prior research also demonstrated, agreeableness is systematically linked to a wide spectrum of prosocial activities and social acceptance (Haas et al., Citation2015; Jani & Han, Citation2015; Joshanloo et al., Citation2012). While agreeableness and extraversion remained significantly positively related with consumers’ attitudes and behavior in the case of hotels green initiatives, which appeared to be a prosocial act (Tang & Lam, Citation2017). Given the premise that femvertising entails a socially beneficial practice aimed at empowering women through advertising, and building upon the established association between personality traits and prosocial behaviors as evidenced by previous research (Carlo et al., Citation2005; Tang & Lam, Citation2017). This study posits that agreeableness and extraversion may serve as moderators in the prediction of consumer attitudes towards femvertising, specifically through the mediating role of gratitude. Notably, the remaining personality traits of conscientiousness, openness, and neuroticism have not been included in the present investigation due to the inherent nature of the study.

Previous research has recognized the importance of examining personality traits in the context of advertising (Abitbol & Sternadori, Citation2020; Kulkarni et al., Citation2019; Myers et al., Citation2010). The moderating influence of personality traits will aid marketers in making informed choices regarding the ad type that will best match the personalities of target markets. Individuals show a preference for ad messages that are consistent with their personality qualities, thus they are compelled to express good feelings about them (Choi, Citation2020). Hence, given the previous argument, the following assumptions are developed ().

H3: The relationships of message involvement with attitude towards femvertising via gratitude is moderated by personality traits (a) agreeableness (b) extraversion, such that the relationship will be stronger when (a) agreeableness (b) extraversion would be high verses low.

H4: The relationships of feminist consciousness with attitude towards femvertising via gratitude is moderated by personality traits (a) agreeableness (b) extraversion via gratitude, such that the relationship will be stronger when (a) agreeableness (b) extraversion would be high verses low.

Methodology

Utilizing a quantitative research methodology, data was gathered from a sample of participants who were 18 years of age or older. This was accomplished through online platforms such as emails, social media platforms, and direct messaging. Individuals were issued invitations to participate in the study. Before commencing the survey, the participants were provided with a thorough introduction to the term of femvertising, based on a well-established definition presented by Åkestam et al. (Citation2017). This measure was implemented to guarantee that all participants had an in-depth knowledge of the phenomenon being examined.

The researchers employed convenience sampling as a result of the unavailability of an appropriate sampling frame, aligning with the prevalent approach in consumer research (Jani & Han, Citation2015). The survey instrument’s content validity was established through an advisory panel of academic specialists who conducted a thorough assessment to eliminate any unnecessary details and address grammatical errors. A survey was circulated across a population consisting of 500 individuals, resulting in the receipt of 420 responses. The ultimate sample size of 402 participants was determined by excluding respondents who completed the questionnaire in less than five minutes. The study included participants from a variety of demographic backgrounds, with the goal of achieving sufficient representation and inclusion. A diverse sample was selected, comprising individuals of both male and female genders.

Survey instruments

The study variables were measured by adopting scales from prior research. The survey focused on two prominent dimensions of personality, namely extraversion and agreeableness. Message involvement, feminist consciousness, gratitude, attitude towards femvertising along with demographic variables of the respondents was included. The items were assessed using a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The construct of gratitude was investigated in this study by employing a three-item scale adapted from the research conducted by Kim and Park (Citation2020). In order to assess agreeableness and extraversion, a concise iteration of the Big Five Personality Traits Scale developed by Yoo and Gretzel (Citation2011), was opted. This particular version was chosen due to its straightforward narrative structure, which facilitated comprehension for the participants. Message involvement was measured through the utilization of a four-item scale, as devised by Laczniak et al. (Citation1999). The scale utilized to measure feminist consciousness in this study was derived from the work of Wilcox (Citation1991). The present study incorporated a set of 11 items, derived from Wells’ seminal work in 1964, to assess the prevailing attitude towards femvertising. The existing body of research indicates that consumer attitudes towards femvertising exhibit variability contingent upon age, gender, and education. This observation implies that age, gender, and education possess the potential to introduce confounding factors into our findings. Consequently, in order to mitigate the influence of these variables, they were meticulously controlled for in the present study (Elhajjar, Citation2021; Teng et al., Citation2021).

Results

Testing reliability and validity

demonstrates the means and standard deviation of all the study variables. Cronbach alpha values for the variables analyzed were all higher than the recommended bottom line of 0.7 (Nunnally, Citation1978). As expected, the inter construct correlations among the variables were consistent. Message involvement and feminist consciousness was positively correlated with gratitude. Similarly, gratitude showed a significant positive correlation with attitude towards femvertising.

Table 1. Means and correlations.

Measurement model

A series of Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed using AMOS, to examine the model fitness and establish convergent and discriminant validities (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999). The results () revealed that the proposed six factor model including message involvement, feminist consciousness, gratitude, attitude towards femvertising and the two personality traits (extraversion and agreeableness) demonstrated a suitable fit- χ2 = 795.00, df = 449, χ2/df = 1.77, RMSEA= 0.04, SRMR = 0.04, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.95-as compared to the four factor, two factor and single factor alternative models indicating poor fit.

Table 2. Confirmatory factor analysis of discriminate validity.

Hypothesis testing

Mediation analysis

Using Hayes Process Macros (Hayes, Citation2016), the results () showed that the relationship between message involvement and attitude towards femvertising is mediated by the feeling of gratitude, supporting hypothesis 1. Similarly, gratitude mediates the relationship between feminist consciousness and attitude towards femvertising (), hence hypothesis 2 is supported.

Table 3. Results of bootstrapped mediation analysis.

Table 4. Results of bootstrapped mediation analysis.

Moderated mediation analysis

The results indicated that the conditional indirect effect of message involvement on attitude towards femvertising via gratitude was significant when the personality traits, extraversion and agreeableness were higher as compared to low ( and , respectively). The LL=-0.044 and UL = 0.038 at −1 SD, whereas at +1 SD the LL = 0.099 and UL = 0.222 at 95% confidence interval indicates the conditional effect of extraversion (). Similarly, the LL = −0.0327 and UL = 0.056 at −1 SD, whereas LL = 0.089 and UL = 0.209 at +1 SD, 95% confidence interval showing conditional effect of agreeableness. Hence, the hypothesis 3 is supported. Further demonstrating the significant conditional indirect effect of feminist consciousness on attitude towards femvertising via gratitude when extraversion and agreeableness are higher as compared to low, and shows the results. For extraversion the LL = −0.254 and UL = 0.088 at −1 SD, and LL = 0.096 and UL = 0.221 at +1 SD, 95% confidence interval showing that when extraversion is higher the moderated mediation relationship is significant. Moreover, for agreeableness the LL = −0.047 and UL= 0.608 at −1 SD, and LL = 0.110 and UL = 0.248 at +1 SD with 95% confidence interval, shows that significant indirect effect of feminist consciousness on attitude towards femvertising via gratitude when agreeableness was higher. Hence, hypothesis 4 is supported.

Table 5. Indirect effects of message involvement on attitude towards Femvertising.

Table 6. Indirect effects of message involvement on attitude towards femvertising.

Table 7. Indirect effects of feminist consciousness on attitude towards femvertising.

Table 8. Indirect effects of feminist consciousness on attitude towards femvertising.

Discussion

This study aimed at extending the femvertising literature by investigating the impact of message involvement and feminist consciousness on customers’ attitudes toward femvertising via gratitude. Due to a rise in brand activism and conscious capitalism, there has been a significant increase in research interest towards femvertising (Abitbol & Sternadori, Citation2019; Champlin et al., Citation2019; Varghese & Kumar, Citation2022). The effect of personality traits (agreeableness and extraversion) as a moderating factor between the indirect relationship of message involvement, feminist consciousness, and attitude toward femvertised commercials via gratitude was still not investigated. This study contributes to the body of knowledge by providing a framework focusing on missing mediator, which includes gratitude. Additionally, two personality traits, agreeableness and extraversion, as moderators has been presented in response to prior calls for examining missing factors to examine the response to femvertised adverts (Abitbol & Sternadori, Citation2020; Grau & Zotos, Citation2016; Varghese & Kumar, Citation2022).

Drawing on social judgement theory (Arora, Citation1985; Sherif & Hovland, Citation1961) and in line with previous findings, message involvement in femvertised advertising may lead to a positive attitude via gratitude, as femvertised ads are centered on empowering portrayals of women, which fosters an emotional connection with consumers (Åkestam, Citation2018; Kapoor & Munjal, Citation2017). Additionally, as feminist consciousness is raised through, popular media channels (Harrington, Citation2020); hence the empowering portrayal of women in ads depicted a positive attitude towards femvertising. This study also shows that there was a significant association between feminist consciousness and attitude toward femvertised commercials due to the presence of positive emotion of gratitude. Considering femvertising reduces ad reactance (Åkestam et al., Citation2017; Vadakkepatt et al., Citation2022) and positive feelings are formed as a result of watching femvertised ads, customers feel grateful to the brands, which elicits pleasant emotions.

In contrast to previous advertising research that used personality traits as antecedents of ad attitudes (Choi, Citation2020; Fazli-Salehi et al., Citation2022), this study found that personality traits can moderate the indirect relationship between message involvement, feminist consciousness, and attitude toward femvertising via gratitude. As a result, the symbolic representation of current female related empowering portrayals in advertisements aligns with consumers’ views and tends to boost positive attitudes toward femvertising. Individuals with agreeableness and extrovert traits are more likely to respond positively to advertising that elicit positive feelings (Kulkarni et al., Citation2019; Orth et al., Citation2010), such as femvertising, which focuses on reducing the gender gap., Hence the moderating role of agreeableness and extraversion was found significant.

Theoretical contributions

Firstly, by establishing a relationship between message involvement and attitude towards femvertising through the mediating mechanism, this study contributes to the literature of message involvement, gratitude and the advertising related consumer outcome. This sheds light on the underlying mechanism of gratitude, which enhances the relationship between an individual’s message involvement and the subsequent attitudes. Secondly, the present study expands upon existing literature by providing the relationship between feminist consciousness and attitude towards femvertising through the mediator gratitude. This thereby proposes that the attitudes in question are contingent upon the fundamental emotional mechanisms related to individuals.

Thirdly, by providing an indirect relationship between message involvement and attitude towards femvertising via gratitude when personality traits serve as a boundary condition in the given relationships, this study adds to the existing literature of femvertising and personality traits. In previous studies, personality traits were found to have a considerable impact on the ad-evoked feeling (Hirsh et al., Citation2012; Kulkarni et al., Citation2019; Mooradian, Citation1996). We examined agreeableness and extraversion because they have a proclivity towards prosocial actions (Carlo et al., Citation2005; Tang & Lam, Citation2017). Explaining the moderating impact of these attributes among the many constructs can aid in broadening understanding of strategic advertising research, particularly in third-world economies.

Furthermore, previous research has studied the effect of feminist self-identification with the attitude towards femvertising (Sternadori & Abitbol, Citation2019), however in this study the effect of consumers overall feminist consciousness on attitude towards femvertising via gratitude has been studied, when the personality traits serve as a boundary condition in the relationship. This underscores the significance of comprehending the impact individual’s personality traits in molding and cultivating consumers’ inclinations towards advertising campaigns, such as femvertising, which are designed to influence consumers’ cognitive mechanisms. Hence, it can be stated that, consumers are more likely to reciprocate by having a favorable attitude toward femvertised advertisements if the symbolic portrayal of contemporary female-related societal concerns in adverts is consistent with their feminist held beliefs.

Practical implications

The evidence has demonstrated academic scholarship regarding femvertising is still in its initial stages. It has a broader spectrum in marketing research because social stakeholders primarily influence a company’s strategic communication (Åkestam et al., Citation2017; Champlin et al., Citation2019; Varghese & Kumar, Citation2022). Because of its prominence, profit-driven businesses must incorporate social marketing strategies into their advertising campaigns as part of their corporate social responsibility, resulting in favourable attitudes toward brands (Campbell, Citation2007). Women in important jobs balancing work and family life have been a key part of advertising ideas, moving away from showing women as beautiful icons (Teng et al., Citation2021). For marketing and advertising professionals, this study has practical implications, as it suggested that marketers should look beyond traditional demographical boundaries and consider the personality traits of customers when using innovative advertising themes like femvertising, reinforcing the importance of preliminary market research. The findings further suggest that tailoring marketing communications to the personality traits of the intended audience can be a valuable strategy to enhance their impact, as well as illustrating the possible role of personality-based efficient communication. Advertisers use business intelligence (e.g., site visits, purchasing patterns thorough artificial intelligence) to obtain personal information about individuals to frame adverts according to consumers potential needs. Not only can these information cues be used, but inferences can also be drawn from the language (Hirsh & Peterson, Citation2009) consumer’s use on social media platforms to understand the personality of individuals and frame femvertised messages accordingly.

Limitations and future research

This research provided considerable additions to the femvertising literature, yet research is not without limitations. One of the limitations was the use of online sampling, which resulted in convenience rather than representative sample. Second, this research was done with educated people, however future research may be done with a different population sample. Finally, we showed stimuli advertisements that offered a gender neural product; however, future research could focus on specific types of femvertising, such as body positive messaging, workplace equality, and so on. This indicates that adapting strategic femvertising messages to the customer’s personality and common interests of both the company and the consumer might be an effective way to establish underlying ties. For this study, we focused on two personality traits: agreeableness and extraversion; however, a comprehensive examination of the big five personality traits (conscientiousness, neuroticism, openness, agreeableness, and extraversion) will provide a detailed individual level analysis of attitudes toward femvertising in terms of negative and positive personality traits.

Conclusion

Advertising creatives have been enthusiastic to address women-related topics and empowering imagery in their brand communications since the term femvertising was devised. Although feminists have criticized corporations for using feminist discourse to increase profits, consumers have praised femvertising because it promotes the best gender-based narratives that can promote societal wellbeing. Because of the rise of social media movements such as #Metoo and #TimesUp, consumers are more conscious of the need for brand activism from the corporate sector, and as a result, consumers have shown a favourable attitude toward female-empowering advertising.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Amber Waqar

Dr. Amber Waqar is an Assistant Professor of Entrepreneurship at Faculty of Knowledge Unit of Business, Economics, Accounting and Commerce, University of Management and Technology, Sialkot. Her major research interests focus on Social Entrepreneurship, New Venture Creation, Sustainability and Family Business.

Mahwish Jamil

Dr. Mahwish Jamil is an Assistant Professor of Entrepreneurship at the Department of Business Administration, University of South Asia, Raiwind Campus. Her major research interests focus on Entrepreneurship, Strategic Management, Family Business, Social Entrepreneurship and Marketing.

Nabil Mohemmed AL-Hazmi

Dr. Nabil M. Al-hazmi is an Associate Professor of Marketing at the Department of Marketing College of Business Administration, Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University. His major research interests focus on e-marketing, e-commerce, e-business, marketing, Total quality Management, Tourism Marketing, e-CRM, service quality, and Sales Management.

Aleena Amir

Aleena Amir is currently working toward a Doctor of Philosophy degree at the Department of International Business & Marketing, National University of Sciences and Technology, H-12 Islamabad campus. Her primary research interests focus on social marketing, advertising, consumer behavior, and brand activism.

References

- Abitbol, A., & Sternadori, M. (2019). Championing women’s empowerment as a catalyst for purchase intentions: Testing the mediating roles of OPRs and brand loyalty in the context of femvertising. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 13(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2018.1552963

- Abitbol, A., & Sternadori, M. M. (2020). Consumer location and ad type preferences as predictors of attitude toward femvertising. Journal of Social Marketing, 10(2), 179–195. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSOCM-06-2019-0085

- Åkestam, N. (2018). Caring for her: The influence of presumed influence on female consumers’ attitudes towards advertising featuring gender-stereotyped portrayals. International Journal of Advertising, 37(6), 871–892. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2017.1384198

- Åkestam, N., Rosengren, S., & Dahlen, M. (2017). Advertising "like a girl": Toward a better understanding of "femvertising" and its effects. Psychology & Marketing, 34(8), 795–806. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21023

- Allport, G. W. (1937). Personality: A psychological interpretation. Holt.

- An, D., & Kim, S. (2007). Relating Hofstede’s masculinity dimension to gender role portrayals in advertising. International Marketing Review, 24(2), 181–207. https://doi.org/10.1108/02651330710741811

- Andrews, J. C., Akhter, S. H., Durvasula, S., & Muehling, D. D. (1992). The effects of advertising distinctiveness and message content involvement on cognitive and affective responses to advertising. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising, 14(1), 45–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/10641734.1992.10504979

- Andrews, J. C., Durvasula, S., & Akhter, S. H. (1990). A framework for conceptualizing and measuring the involvement construct in advertising research. Journal of Advertising, 19(4), 27–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.1990.10673198

- Arora, R. (1985). Consumer involvement: What it offers to advertising strategy. International Journal of Advertising, 4(2), 119–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.1985.11105055

- Baker, W. E., & Lutz, R. J. (2000). An empirical test of an updated relevance-accessibility model of advertising effectiveness. Journal of Advertising, 29(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2000.10673599

- Bartsch, A., & Kloß, A. (2018). Personalized charity advertising. Can personalized prosocial messages promote empathy, attitude change, and helping intentions toward stigmatized social groups? International Journal of Advertising, 38(3), 345–363. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2018.1482098

- Batra, R., & Ray, M. L. (1986). Affective responses mediating acceptance of advertising. Journal of Consumer Research, 13(2), 234–249. https://doi.org/10.1086/209063

- Belanche, D., Flavián, C., & Pérez-Rueda, A. (2017). Understanding interactive online advertising: Congruence and product involvement in highly and lowly arousing, skippable video ads. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 37(1), 75–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2016.06.004

- Bissell, K., & Rask, A. (2010). Real women on real beauty: Self-discrepancy, internalization of the thin ideal, and perceptions of attractiveness and thinness in Dove’s campaign for real beauty. International Journal of Advertising, 29(4), 643–668. https://doi.org/10.2501/S0265048710201385

- Bock, D. E., Eastman, J. K., & Eastman, K. L. (2018). Encouraging consumer charitable behavior: The impact of charitable motivations, gratitude, and materialism. Journal of Business Ethics, 150(4), 1213–1228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3203-x

- Bridger, E. K., & Wood, A. (2017). Gratitude mediates consumer responses to marketing communications. European Journal of Marketing, 51(1), 44–64. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-11-2015-0810

- Brown, T. J., Mowen, J. C., Donavan, D. T., & Licata, J. W. (2002). The customer orientation of service workers: Personality trait effects on self-and supervisor performance ratings. Journal of Marketing Research, 39(1), 110–119. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.39.1.110.18928

- Campbell, J. L. (2007). Why would corporations behave in socially responsible ways? an institutional theory of corporate social responsibility. Academy of Management Review, 32(3), 946–967. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2007.25275684

- Carlo, G., Okun, M. A., Knight, G. P., & de Guzman, M. R. T. (2005). The interplay of traits and motives on volunteering: Agreeableness, extraversion and prosocial value motivation. Personality and Individual Differences, 38(6), 1293–1305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2004.08.012

- Castillo, M. (2014). These stats prove femvertising works. http://www.adweek.com/news/technology/these-stats-provefemvertising-works-160704.

- Champlin, S., Sterbenk, Y., Windels, K., & Poteet, M. (2019). How brand-cause fit shapes real world advertising messages: A qualitative exploration of ‘femvertising. International Journal of Advertising, 38(8), 1240–1263. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2019.1615294

- Cheng, H., & Wan, G. (2008). Holding up half of the “ground?” Women portrayed in subway advertisements in China. In K. Frith & K. Karan (Eds.), Commercializing women: Images of Asian women in the media (pp. 11–32). Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

- Choi, C. W. (2020). The impacts of consumer personality traits on online video ads sharing intention. Journal of Promotion Management, 26(7), 1073–1092. https://doi.org/10.1080/10496491.2020.1746468

- Choi, H., Yoo, K., Reichert, T., & Northup, T. (2020). Feminism and advertising: Responses to sexual ads featuring women: How the differential influence of feminist perspectives can inform targeting strategies. Journal of Advertising Research, 60(2), 163–178. https://doi.org/10.2501/JAR-2020-010

- Cook, E. A. (1989). Measuring feminist consciousness. Women & Politics, 9(3), 71–88. https://doi.org/10.1300/J014v09n03_04

- Cornwall, A. (2016). Women’s empowerment: What works? Journal of International Development, 28(3), 342–359. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3210

- Costa, P. T., Jr., & McCrae, R. R. (1995). Solid ground in the wetlands of personality: A reply to Block. Psychological Bulletin, 117(2), 216–220. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.2.216

- Dans, C. (2018). Commodity Feminism Today: An Analysis of the “Always #LikeAGirl” Campaign [Master’s thesis], West Virginia University Libraries. https://doi.org/10.33915/etd.5434

- Dodoo, N. A., & Padovano, C. M. (2020). Personality-based engagement: An examination of personality and message factors on consumer responses to social media advertisements. Journal of Promotion Management, 26(4), 481–503. https://doi.org/10.1080/10496491.2020.1719954

- Drake, V. E. (2017). The impact of female empowerment in advertising (femvertising). Journal of Research in Marketing, 7(3), 593–599.

- Duncan, L. E. (2010). Women’s relationship to feminism: Effects of generation and feminist self-labeling. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 34(4), 498–507. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2010.01599.x

- Eisend, M., Plagemann, J., & Sollwedel, J. (2014). Gender roles and humor in advertising: The occurrence of stereotyping in humorous and nonhumorous advertising and its consequences for advertising effectiveness. Journal of Advertising, 43(3), 256–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2013.857621

- Elhajjar, S. (2021). Attitudes toward femvertising in the Middle East: The case of Lebanon. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 13(5), 1111–1124. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIMA-04-2020-0108

- Fazli-Salehi, R., Torres, I. M., Madadi, R., & Zúñiga, M. Á. (2022). The impact of interpersonal traits (extraversion and agreeableness) on consumers’ self-brand connection and communal-brand connection with anthropomorphized brands. Journal of Brand Management, 29(1), 13–34. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-021-00251-9

- Feng, Y., Chen, H., & He, L. (2019). Consumer responses to femvertising: A data-mining case of Dove’s "campaign for real beauty" on YouTube. Journal of Advertising, 48(3), 292–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2019.1602858

- Fernando, A. G., Sivakumaran, B., & Suganthi, L. (2016). Message involvement and Attitude towards green advertisements. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 34(6), 863–882. https://doi.org/10.1108/MIP-11-2015-0216

- Ford, J. B., & LaTour, M. S. (1996). Contemporary female perspectives of female role portrayals in advertising. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising, 18(1), 81–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/10641734.1996.10505042

- Ford, J. B., LaTour, M. S., & Middleton, C. (1999). Women’ studies and advertising role portrayal sensitivity: How easy is it to raise "feminist consciousness"? Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising, 21(2), 77–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/10641734.1999.10505096

- Freedman, J. L. (1964). Involvement, discrepancy, and change. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 69(3), 290–295. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0042717

- Ganz, B., & Grimes, A. (2018). How claim specificity can improve claim credibility in Green Advertising: Measures that can boost outcomes from environmental product claims. Journal of Advertising Research, 58(4), 476–486. https://doi.org/10.2501/JAR-2018-001

- Goldberg, L. R., & Saucier, G. (1995). So what do you propose we use instead? A reply to Block. Psychological Bulletin, 117(2), 221–225. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.2.221

- Grau, S. L., & Zotos, Y. C. (2016). Gender stereotypes in advertising: A review of current research. International Journal of Advertising, 35(5), 761–770. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2016.1203556

- Graziano, W. G., & Eisenberg, N. (1997). Agreeableness: A dimension of personality. In R. Hogan, J. A. Johnson, & S. R. Briggs (Eds.), Handbook of personality psychology (pp. 795–824). Academic Press.

- Greenwald, A. G., & Leavitt, C. (1984). Audience involvement in advertising: Four levels. Journal of Consumer Research, 11(1), 581–592. https://doi.org/10.1086/208994

- Haas, B. W., Ishak, A., Denison, L., Anderson, I., & Filkowski, M. M. (2015). Agreeableness and brain activity during emotion attribution decisions. Journal of Research in Personality, 57, 26–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2015.03.001

- Habashi, M. M., Graziano, W. G., & Hoover, A. E. (2016). Searching for the prosocial personality: A Big Five approach to linking personality and prosocial behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 42(9), 1177–1192. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167216652859

- Hainneville, V., Guèvremont, A., & Robinot, É. (2022). Femvertising or femwashing? Women’s perceptions of authenticity. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 22(4), 933–941. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.2020

- Hampson, S. E. (2012). Personality processes: Mechanisms by which personality traits "get outside the skin”. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 315–339. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100419

- Han, E., Park, C., & Khang, H. (2018). Exploring linkage of message frames with personality traits for political advertising effectiveness. Asian Journal of Communication, 28(3), 247–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/01292986.2017.1394333

- Harrington, C. (2020). Popular feminist websites, intimate publics, and feminist knowledge about sexual violence. Feminist Media Studies, 20(2), 168–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2018.1546215

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. The Guilford Press.

- Hirsh, J. B., Kang, S. K., & Bodenhausen, G. V. (2012). Personalized persuasion: Tailoring persuasive appeals to recipients’ personality traits. Psychological Science, 23(6), 578–581. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611436349

- Hirsh, J. B., & Peterson, J. B. (2009). Personality and language use in self-narratives. Journal of Research in Personality, 43(3), 524–527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2009.01.006

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Huggins, K. A., White, D. W., Holloway, B. B., & Hansen, J. D. (2020). Customer gratitude in relationship marketing strategies: A cross-cultural e-tailing perspective. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 37(4), 445–455. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCM-08-2019-3380

- Jani, D., & Han, H. (2015). Influence of environmental stimuli on hotel customer emotional loyalty response: Testing the moderating effect of the big five personality factors. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 44, 48–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2014.10.006

- Johnston, J., & Taylor, J. (2008). Feminist consumerism and fat activists: A comparative study of grassroots activism and the Dove real beauty campaign. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 33(4), 941–966. https://doi.org/10.1086/528849

- Joshanloo, M., Rastegar, P., & Bakhshi, A. (2012). The Big Five personality domains as predictors of social wellbeing in Iranian university students. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 29(5), 639–660. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407512443432

- Kammrath, L. K., & Scholer, A. A. (2011). The Pollyanna Myth: How highly agreeable people judge positive and negative relational acts. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(9), 1172–1184. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167211407641

- Kapoor, D., & Munjal, A. (2017). Self-consciousness and emotions driving femvertising: A path analysis of women’s Attitude towards femvertising, forwarding intention and purchase intention. Journal of Marketing Communications, 25(2), 137–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2017.1338611

- Kim, J., & Park, T. (2020). How corporate social responsibility (CSR) saves a company: The role of gratitude in buffering vindictive consumer behavior from product failures. Journal of Business Research, 117, 461–472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.06.024

- Kim, Y., Smith, R. D., & Kwak, D. H. (2018). Feelings of gratitude: A mechanism for consumer reciprocity. European Sport Management Quarterly, 18(3), 307–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2017.1389973

- Kotler, P., & Lee, N. (2005). Corporate social responsibility: Doing the most good for your company. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Krugman, H. E. (1965). The impact of television advertising: Learning without involvement. Public Opinion Quarterly, 29(3), 349–356. https://doi.org/10.1086/267335

- Kulkarni, K. K., Kalro, A. D., & Sharma, D. (2019). Sharing of branded viral advertisements by young consumers: The interplay between personality traits and ad appeal. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 36(6), 846–857. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCM-11-2017-2428

- Kwon, J., & Nayakankuppam, D. (2015). Strength without elaboration: The role of implicit self-theories in forming and accessing attitudes. Journal of Consumer Research, 42(2), ucv019. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucv019

- Laczniak, R. N., Kempf, D. S., & Muehling, D. D. (1999). Advertising message involvement: The role of enduring and situational factors. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising, 21(1), 51–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/10641734.1999.10505088

- Laczniak, R. N., Muehling, D. D., & Grossbart, S. (1989). Manipulating message involvement in advertising research. Journal of Advertising, 18(2), 28–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.1989.10673149

- Landers, R. N., & Lounsbury, J. W. (2006). An investigation of Big Five and narrow personality traits in relation to internet usage. Computers in Human Behavior, 22(2), 283–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2004.06.001

- Lee, Y. H. (2000). Manipulating ad message involvement through information expectancy: Effects on attitude evaluation and confidence. Journal of Advertising, 29(2), 29–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2000.10673607

- Li, J. Y., Kim, J. K., & Alharbi, K. (2020). Exploring the role of issue involvement and brand attachment in shaping consumer response toward corporate social advocacy (CSA) initiatives: The case of Nike’s Colin Kaepernick campaign. International Journal of Advertising, 41(2), 233–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2020.1857111

- Martins, N. (2002). A model for managing trust. International Journal of Manpower, 23(8), 754–769. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437720210453984

- McCullough, M. E., Emmons, R. A., & Tsang, J. A. (2002). The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(1), 112–127. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.1.112

- McCullough, M. E., Kilpatrick, S. D., Emmons, R. A., & Larson, D. B. (2001). Is gratitude a moral affect? Psychological Bulletin, 127(2), 249–266. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.127.2.249

- Middleton, K., & Turnbull, S. (2021). How advertising got ‘woke’: The institutional role of advertising in the emergence of gender progressive market logics and practices. Marketing Theory, 21(4), 561–578. https://doi.org/10.1177/14705931211035163

- Mishra, A. A. (2016). The role of customer gratitude in relationship marketing: Moderation and model validation. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 24(6), 529–549. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965254X.2016.1148762

- Mooradian, T. A. (1996). Personality and ad-evoked feelings: The case for extraversion and neuroticism. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 24(2), 99–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070396242001

- Moorman, C. (2020). Commentary: Brand activism in a political world. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 39(4), 388–392. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743915620945260

- Mowen, J. C., Harris, E. G., & Bone, S. A. (2004). Personality traits and fear response to print advertisements: Theory and an empirical study. Psychology & Marketing, 21(11), 927–943. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20040

- Myers, S. D., Sen, S., & Alexandrov, A. (2010). The moderating effect of personality traits on attitudes toward advertisements: A contingency framework. Management & Marketing, 5(3), 3.

- Nunnally, J. (1978). Psychometric theory (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Orth, U. R., Malkewitz, K., & Bee, C. (2010). Gender and personality drivers of consumer mixed emotional response to advertising. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising, 32(1), 69–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/10641734.2010.10505276

- Paek, H. J., Nelson, M. R., & Vilela, A. M. (2011). Examination of gender-role portrayals in television advertising across seven countries. Sex Roles, 64(3-4), 192–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-010-9850-y

- Palmatier, R. W., Jarvis, C. B., Bechkoff, J. R., & Kardes, F. R. (2009). The role of customer gratitude in relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 73(5), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.73.5.1

- Patel, J. D., Gadhavi, D. D., & Shukla, Y. S. (2017). Consumers’ responses to cause related marketing: Moderating influence of cause involvement and skepticism on attitude and purchase intention. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 14(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-016-0151-1

- Pérez, M. P. R., & Gutiérrez, M. (2017). Femvertising: Female empowering strategies in recent Spanish commercials. Investigaciones Feministas, 8(2), 337–351.

- Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1996). Addressing disturbing and disturbed consumer behavior: Is it necessary to change the way we conduct behavioral science? Journal of Marketing Research, 33(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.2307/3152008

- Romani, S., Grappi, S., & Bagozzi, R. P. (2013). Explaining consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility: The role of gratitude and altruistic values. Journal of Business Ethics, 114(2), 193–206. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1337-z

- Ruiz, S., & Sicilia, M. (2004). The impact of cognitive and/or affective processing styles on consumer response to advertising appeals. Journal of Business Research, 57(6), 657–664. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(02)00309-0

- Turner, S. G., & Maschi, T. M. (2015). Feminist and empowerment theory and social work practice. Journal of Social Work Practice, 29(2), 151–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650533.2014.941282

- Schmidt, S., & Eisend, M. (2015). Advertising repetition: A meta-analysis on effective frequency in advertising. Journal of Advertising, 44(4), 415–428. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2015.1018460

- Septianto, F., & Garg, N. (2021). The impact of gratitude (vs pride) on the effectiveness of cause-related marketing. European Journal of Marketing, 55(6), 1594–1623. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-11-2019-0829

- Shaffer, D. R. (2000). Social and personality development (4th ed.). Wadsworth/Thomson Learning.

- Sherif, M., & Hovland, C. I. (1961). Social judgment: Assimilation and contrast effects in communication and attitude change. Yale University Press.

- Siero, F. W., & Doosje, B. J. (1993). Attitude change following persuasive communication: Integrating social judgment theory and the elaboration likelihood model. European Journal of Social Psychology, 23(5), 541–554. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420230510

- Smith, S. W., Atkin, C. K., Martell, D., Allen, R., & Hembroff, L. (2006). A social judgment theory approach to conducting formative research in a social norms campaign. Communication Theory, 16(1), 141–152. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2006.00009.x

- Snippe, E., Jeronimus, B. F., Aan Het Rot, M., Bos, E. H., de Jonge, P., & Wichers, M. (2018). The reciprocity of prosocial behavior and positive affect in daily life. Journal of Personality, 86(2), 139–146. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12299

- Sobande, F. (2019). Woke-washing: “Intersectional” femvertising and branding “woke” bravery. European Journal of Marketing, 54(11), 2723–2745. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-02-2019-0134

- Sowards, S. K., & Renegar, V. R. (2004). The rhetorical functions of consciousness-raising in third wave feminism. Communication Studies, 55(4), 535–552. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510970409388637

- Spielmann, N., & Richard, M.-O. (2013). How captive is your audience? Defining overall advertising involvement. Journal of Business Research, 66(4), 499–505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.12.002

- Sterbenk, Y., Champlin, S., Windels, K., & Shelton, S. (2022). Is Femvertising the new greenwashing? Examining corporate commitment to gender equality. Journal of Business Ethics, 177(3), 491–505. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-04755-x

- Stern, B. B. (1992). Feminist literary theory and advertising research: A new "reading" of the text and the consumer. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising, 14(1), 9–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10641734.1992.10504976

- Sternadori, M., & Abitbol, A. (2019). Support for women’s rights and feminist self-identification as antecedents of attitude toward femvertising. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 36(6), 740–750. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCM-05-2018-2661

- Sweetman, C. (2013). Introduction, feminist solidarity and collective action. Gender & Development, 21(2), 217–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552074.2013.819176

- Tang, C. M. F., & Lam, D. (2017). The role of extraversion and agreeableness traits on Gen Y’s attitudes and willingness to pay for green hotels. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(1), 607–623. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-02-2016-0048

- Taylor, J., Johnston, J., & Whitehead, K. (2016). A corporation in feminist clothing? Young women discuss the dove ‘Real beauty’ campaign. Critical Sociology, 42(1), 123–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/0896920513501355

- Teng, F., Hu, J., Chen, Z., Poon, K. T., & Bai, Y. (2021). Sexism and the effectiveness of femvertising in China: A corporate social responsibility perspective. Sex Roles, 84(5-6), 253–270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-020-01164-8

- Thomson, A. L., & Siegel, J. T. (2017). Elevation: A review of scholarship on a moral and other-praising emotion. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(6), 628–638. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1269184

- Trapnell, P. D., & Wiggins, J. S. (1990). Extension of the Interpersonal Adjective Scales to include the Big Five dimensions of personality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(4), 781–790. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.59.4.781

- Uribe, R., Labra, R., & Manzur, E. (2022). Modeling and evaluating the effectiveness of AR advertising and the moderating role of personality traits. International Journal of Advertising, 41(4), 703–730. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2021.1908784

- Vadakkepatt, G., Bryant, A., Hill, R. P., & Nunziato, J. (2022). Can advertising benefit women’s development? Preliminary insights from a multi-method investigation. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 50(3), 503–520. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-021-00823-w

- Van Steenburg, E., & Spears, N. (2021). How preexisting beliefs and message involvement drive charitable donations: An integrated model. European Journal of Marketing, 56(1), 209–251. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-01-2020-0031

- Varghese, N., & Kumar, N. (2022). Feminism in advertising: Irony or revolution? A critical review of femvertising. Feminist Media Studies, 22(2), 441–459. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2020.1825510

- Varnali, K., Yilmaz, C., & Toker, A. (2012). Predictors of attitudinal and behavioral outcomes in mobile advertising: A field experiment. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 11(6), 570–581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap.2012.08.002

- Walters, R. (2021). Varieties of gender wash: Towards a framework for critiquing corporate social responsibility in feminist IPE. Review of International Political Economy, 29(5), 1577–1600. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2021.1935295

- Wang, A. (2006). Advertising engagement: A driver of message involvement on message effects. Journal of Advertising Research, 46(4), 355–368. https://doi.org/10.2501/S0021849906060429

- Wannow, S., Haupt, M., & Ohlwein, M. (2023). Is brand activism an emotional affair? The role of moral emotions in consumer responses to brand activism. Journal of Brand Management, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-023-00326-9

- Wells, W. D. (1964). EQ, son of EQ and the reaction profile. Journal of Marketing, 28(4), 45–52. https://doi.org/10.2307/1249570

- Whittaker, J. O. (1965). Attitude change and communication-attitude discrepancy. The Journal of Social Psychology, 65(1), 141–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.1965.9919591

- Wiggins, J. S., & Trapnell, P. D. (1997). Personality structure: The return of the Big Five. In R. Hogan, J. Johnson, & S. Briggs (Eds.), Handbook of personality psychology (pp. 737–765). Academic.

- Wilcox, C. (1991). The causes and consequences of feminist consciousness among Western European women. Comparative Political Studies, 23(4), 519–545. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414091023004005

- Wojdynski, B. W., & Evans, N. J. (2020). The covert advertising recognition and effects (CARE) model: Processes of persuasion in native advertising and other masked formats. International Journal of Advertising, 39(1), 4–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2019.1658438

- Wood, A. M., Froh, J. J., & Geraghty, A. W. (2010). Gratitude and wellbeing: A review and theoretical integration. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(7), 890–905. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.005

- Xie, C., Bagozzi, R. P., & Grønhaug, K. (2015). The role of moral emotions and individual differences in consumer responses to corporate green and non-green actions. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(3), 333–356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0394-5

- Yoo, K. H., & Gretzel, U. (2011). Influence of personality on travel-related consumer-generated media creation. Computers in Human Behavior, 27(2), 609–621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.05.002

- Yu, J. (2021). A Cognitive Approach to the Argument Strength × Message Involvement Paradigm in Green Advertising Persuasion. In M.K.J. Waiguny & S. Rosengren (Eds.), Advances in Advertising Research (Vol. XI). European Advertising Academy. Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer Gabler. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-32201-4_23

- Zaichkowsky, J. L. (1985). Measuring the involvement construct. Journal of Consumer Research, 12(3), 341–352. https://doi.org/10.1086/208520