Abstract

This study analyzed supply chain response frameworks (SCRFs). An SCRF that applies to any situation involving supply chain responses (SCRs) and facilitates the understanding of SCR as a process was proposed. The SCRF was designed based on a systematic review of the literature and thematic synthesis. Thirty-seven documents related to the SCR and SCRFs were selected for the literature review. The thematic synthesis identified the contexts in which the frameworks were designed, supply chain (SC) aspects comprising the framework, and coherence between the SCR definition and framework components. Consequently, a new SCRF based on the stimulus–organism–response (SOR) model was proposed. The stimuli that an SC responds to and the results it achieves with the response, response strategy, decision types, time horizon, relationship facilitators, and response feedback are the chain aspects comprising the framework. The new SCRF makes it easier for SC managers to identify the aspects encompassing the response to a stimulus in which managers should be trained to provide a better response. In addition, it extends the theory on the SCR.

IMPACT STATEMENT

Using the systematic literature review and the stimulus-organism-response model, this paper proposes a framework for planning the supply chain response to a stimulus. The response is given following a process that begins with the identification and detection of the stimulus, continues with the management of the response, then the results to be obtained are identified, and finally, the response process is evaluated, and feedback is provided. The framework is a guide so that the response to the stimulus, on the one hand, facilitates the achievement of the objectives of the chain and, on the other hand, satisfies the requirements of those who receive it.

1. Introduction

Supply chain response (SCR) is a constantly developing concept. According to Soni and Kodali (Citation2013), a supply chain (SC) management concept that is being theoretically designed and built should have an overall picture and structure for its implementation. The structure that facilitates the image of the concept is known as a framework. As explained by Grant and Osanloo (Citation2016), a framework shows ways in which the researcher addressed a problem and identifies the constructs or variables and the relationship between them.

Various frameworks have been proposed to facilitate rapid and effective SCR to changes in demand, supply, and the business. Wong et al. (Citation2006) evaluated the SCR for products with volatile and seasonal demands using a framework with strategic and operational decision components. The evaluation was performed by comparing the SCR to the changes in the demand for products with stable behavior in sales against those with volatile and seasonal behavior. Reichhart and Holweg (Citation2007) proposed a framework distinguishing the internal determinants, response requirements, and factors facilitating the relationships between the framework components. Based on systems and strategic collaboration, Kim and Lee (Citation2010) defined a conceptual framework to explain the influence of collaboration between companies on SCR. Mandal (Citation2015) proposed an SCR framework (SCRF) that includes relational factors such as trust, commitment, communication, cooperation, adaptation, and interdependence in SCR, improving SCR by promoting the development of relationships between SC members. Kim et al. (Citation2013) designed a framework for studying the influence of e-procurement, market flexibility, business environment, and advanced manufacturing technologies on SCR. Ghosh et al. (Citation2014) demonstrated through a framework that the integration between the chain links and coordination between the chain members influence SCR. Moradlou et al. (Citation2017) studied the SCR to the reshoring of Indian manufacturing companies in the United Kingdom (UK) by designing a framework that includes information technology (IT) solutions, manufacturing, and human factor teams. Gilal et al. (Citation2017) analyzed the impact of SC management practices and organizational structure on the SCR using a moderate mediation framework. The analysis showed that the organizational structure moderated the mediation between SC management practices and SCR. Davis-Sramek et al. (Citation2019) proposed a framework for determining the influence of factors, such as SC orientation and institutional distance, whether formal or informal, on the SCR. Richey et al. (Citation2022), understanding the SCR as a process, designed a framework that includes the concepts of flexibility, adaptability, agility, resilience, and improvisation. Xu et al. (Citation2022) proposed a framework for reforming SC management during pandemics, in which SCR improvements depend on factors, such as the attitudes of SC management, logistics, forecasting, and analytics.

Two insights can be identified from examining the SCRFs: (1) The proposed frameworks apply only to the response situation being addressed by the researcher, and (2) variables, such as strategic and operational planning, performance indicators, information technologies, management aspects, and relational factors, influence the SCR. However, three gaps were identified in the literature review: (1) No systematic literature review (SLR) of SCRFs has been performed; (2) the SCR literature lacks a framework for addressing response as a process; and (3) no SCRF that includes response feedback in its structure was identified. In this study, an SLR of the SCRF is performed, and a new one in which the SCR is considered as a process is proposed, to address the previously mentioned research gaps. The proposed SCRF has three benefits: (1) The framework will show the process that SC managers should follow to respond to a stimulus; (2) this framework can also be used to establish a training plan in aspects comprising the SCR process; and (3) the SCRF will identify lessons learned and options for improving the SCR.

The new framework is proposed in three phases. The first phase identifies documents addressing the SCR in which SCRFs have been proposed. Thus, an SLR is performed. The SLR is a review of existing research using explicit, accountable, rigorous research methods (Gough et al., Citation2017). Similarly, Malik et al. (Citation2022) stated that an SLR summarizes, synthesizes, and identifies the results of research conducted on a study topic. The documents selected in the first phase are analyzed in the second phase using thematic synthesis to identify the SC aspects comprising the SCRF structure. In the third phase, the stimulus–organism–response (SOR) model proposed by Mehrabian and Russell (Citation1974) is used for the first time to design the SCRF.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the research methodology; Section 3 deals with the SCRFs identified in the literature review; Section 4 analyzes the SCRFs; Section 5 proposes a new SCRF; Section 6 presents the discussions; and Section 7 concludes the study.

2. Research methodology

The SLR was performed to identify the documents facilitating the contextualization of this study and determine ways in which the SCR and SCRF concepts have been addressed in academic literature. The SLR method was adopted from Okoli (Citation2015).

Phase 1 involved selecting a database and defining the inclusion criteria. This study selected the multidisciplinary Scopus database. Documents with the terms ‘supply chain responsiveness and framework’, ‘supply chain responsive and framework’, or ‘supply chain response and framework’ in the title, abstract, keywords, or article body were selected. The documents were selected based on six inclusion criteria: (1) The publication year should be from 1996 to 2022; (2) the document should be discussing a topic that falls under business, management, accounting, engineering, or decision science; (3) the document should be an article or literature review; (4) the published version must be the final one; (5) the publication should be in English; and (6) the document should address the topic of SCR and present an SCRF.

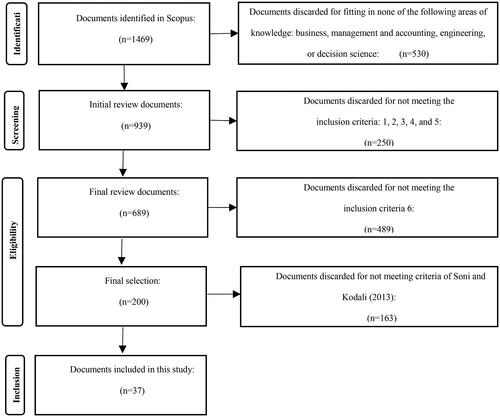

Subsequently, the identified SCRF was verified to fulfill the requirements proposed by Soni and Kodali (Citation2013) for a structure to be classified as a framework: the documents must show the relationships between the elements, describe the steps for using the framework, and show ways in which the activities are connected. shows the results of applying the inclusion criteria and Step 2 of the previously described SRL. Appendix A shows the list of documents analyzed in this study.

The documents selected in the SLR were analyzed in Phase 2 through thematic synthesis. According to Gough et al. (Citation2017) in the thematic synthesis, the framework emerges from the primary studies as the steps of the synthesis unfold. The thematic synthesis is performed in three steps: 1) The topics that were analyzed in all the documents selected in the SLR were defined; the themes in the thematic synthesis aroused either as the synthesis was made or they were previously defined; 2) The themes were related to each other; and 3) Each theme was described. The previously mentioned steps are described below.

To comply with the first step of the thematic synthesis, four themes were defined, which were analyzed in each document: i) The context of the investigation, ii) aspects of the SC that comprise the SCRF, iii) coherence between the definition of the SCR and the components that are part of the framework structure, and iv) ways in which the concept of the SCR was understood in the documents that are part of this study. Each topic is detailed below.

The research context: This encompassed the SC and industry issues that were addressed in the research in which an SCRF was proposed.

Aspects of the SC that comprise the SCRF: The level of the SC addressed and the scope of the framework were analyzed. According to Halldórsson and Arlbjorn (Citation2005), SC is analyzed as a function, company, dyad, chain, or network. The scope of the framework was analyzed based on the type of SC decision in which the framework was proposed, whether strategic, tactical, or operational.

Coherence between the definition of the SCR and the components that are part of the framework structure: To analyze this, the SC’s aspects that constitute the definitions were first identified, later, it was verified if these aspects were part of the structure of the SCRF.

Ways in which the SCR concept was understood in the documents in which the SCRF was proposed: This involves understanding the SCR concept through five words that should appear in the definition: (i) ability; (ii) capacity; (iii) scope; (iv) speed; and (v) process.

To comply with Step 2 of the thematic synthesis, the information on the topics identified in Step 1 was related. Here are two such examples: i) relating the type of industry that was addressed in the research made it easier to identify that 90% of the SCRFs proposed were in response to the manufacturing process and 10% were in response to the service industry; ii) relating the definitions of SCR and the components of the SCRF line-by-line helped determine the coherence between them which was incorporated into the frame structure.

With the description of each of the themes shown in Section 4, called SCRF analysis, Step 3 of the thematic synthesis was fulfilled.

In Phase 3, the SOR model was used to design the new SCRF. According to Matos and Krielow (Citation2019), the SOR model assumes stimuli as factors influencing the organism (for example, an individual or company) to emit a response. The vision of the SOR model, which was discussed previously, made it easier to understand the response of the SC as a process in which the input to the process is the stimulus; the SC (organism) internally processes the stimulus and issues a response.

3. Literature review

Kritchanchai and MacCarthy (Citation1999) proposed a framework for evaluating the SCR to fulfill a manufacturing order. The framework was used to answer questions associated with response aspects, such as the stimulus, impact of the stimulus on the SC goal, and capacities that the SC must develop to respond. Catalan and Kotzab (Citation2003) evaluated the SCR of mobile devices using a framework with demand transparency, effective product flow time, and information components. Salam and Banomyong (Citation2003) determined the influence of aspects, such as buyer behavior, operational accuracy, delivery time, organizational culture, and collaboration on the SCR in the textile industry using a framework. Eng (Citation2005) designed a framework for studying the influence of the orientation toward collective work among various functions in the chain on the response to supply change. Kim et al. (Citation2006) studied the influence of information exchange and coordination between companies on the response capacity of the chain members using a framework. Information exchange involves sharing knowledge, such as environmental changes, new customer preferences, and social changes, among SC members to satisfy customer requirements. Coordination between companies is defined as the management of activities between the SC members. Wong et al. (Citation2006) evaluated the SCR of toys using a framework with forecast uncertainty, demand variability, contribution margin, and delivery time window components. Homburg et al. (Citation2007) proposed a conceptual framework distinguishing between a cognitive and an affective organizational system as two important antecedents of organizational responsiveness. Reichhart and Holweg (Citation2007) studied the SCR to the customer. They designed a framework identifying four types of responsiveness, including product, volume, mix, and delivery. All this can be related to different time horizons and presented as potential or demonstrated responsiveness. Saad and Gindy (Citation2007) used a framework to present factors influencing the response transformation of manufacturing systems in the aerospace industry. Gunasekaran et al. (Citation2008) aimed to improve speed, flexibility, and cost reduction in a responsive SC. They developed a framework encompassing virtual enterprise, strategic planning, knowledge information management, and responsive outputs. Kim and Lee (Citation2010) designed a framework for understanding the influence of collaborative systems and strategic collaboration on the SCR. They reported that systems collaboration is the extent to which the SC members strive to make communication systems compatible with each other to share information and management activities to develop demand forecasting. Strategic collaboration is the extent to which SC partners plan and share the goal of improving long-term relationships. Hence, it includes the sharing of information for demand forecasting and planning across SC partners. Bode et al. (Citation2010) identified options for strategic responses to SC based on information processing and the resource-dependency theory. Using a conceptual framework, Sinkovics et al. (Citation2011) studied the influence of trust and the integration of interorganizational relationships on a the decision of a company to cooperate and control while stimulating the response capacity of the SC. Hayat et al. (Citation2012) investigated the improvement of the SCR based on coordination, considering the concept of coordination as the management of dependencies and efforts among SC members to achieve mutually defined goals. They designed a framework including aspects, such as management commitment, organizational factors, mutual understanding, information flow, relationship, and decision-making. Kim et al. (Citation2013) studied the impact of advanced manufacturing systems, online sourcing, market flexibility, and business environment on supply responsiveness. Thatte et al. (Citation2013) confirmed the influence of management practices, such as the strategic association of suppliers, client relationship, and information exchange, on the SCR. Thatte (Citation2013) determined the relationships between modularity-based manufacturing and SCR using a framework. The analyzed modularity practices were product modularity, process modularity, and dynamic work teams. Qrunfleh and Tarafdar (Citation2013) demonstrated the influence of supplier relations and postponement strategy on SCR using a framework. Tiwari et al. (Citation2013) proposed an SCR framework based on the following perspectives: First, the SC requires flexibility and responsiveness to satisfy changing market and customer requirements. Second, the SC that decreases the time to market for a new product can gain an advantage over the competition and conquer a new market. The six components of the framework are strategic planning, virtual enterprises, knowledge and IT, SC integration, external drivers, and operational factors. Nehzati et al. (Citation2014) adapted the framework proposed by Reichhart and Holweg (Citation2007) to identify the factors requiring and facilitating responsiveness in a multisite production network system in the fast-moving consumer goods sector. Ghosh et al. (Citation2014) demonstrated the effects of integrating chain responsiveness with chain processes, coordination, and performance using a framework validated in the garment industry. To optimize the performance of an SC, Sinha et al. (Citation2015) designed a framework combining the components of the frameworks proposed by Reichhart and Holweg (Citation2007) and Gunasekaran et al. (Citation2008) and aspects, such as flexibility, agility, demand, and speed. Mandal (Citation2015) proposed a framework for studying the influence of attributes such as trust, commitment, communication, cooperation, adaptation, and interdependence on the SCR using a resource-based approach. Rana et al. (Citation2016) designed a framework for empirically testing the influence of agile and lean SC on the SCR and weak influence of hybrid strategy combining agile and lean SC. Rajagopal et al. (Citation2016) verified the importance of lean, agile, supplier relations, and postponement strategies in the SCR. Bode and Macdonald (Citation2017) demonstrated the SC response to disruptions using a framework with four stages: 1) recognition of the response disruption, (2) diagnosis, (3) development, and (4) response implementation. Gilal et al. (Citation2017) analyzed the impact of SC management practices and organizational structures on the SCR using a moderate mediation framework. The analysis showed that the organizational structure moderates the mediation between SC management practices and SCR. Considering the definition of reshoring as bringing manufacturing back home, Moradlou et al. (Citation2017) investigated the reshoring of Indian companies from two perspectives. First, the factors influencing the relocation of Indian companies to the UK were understood. Second, the factors improving SCR in Indian companies were identified. Accordingly, they proposed an SCR framework with IT solutions, manufacturing equipment, and human factor components. Davis-Sramek et al. (Citation2019) used the middle-range theory to explore the facilitation of the response of the global SC by the SC orientation. The components of the framework are formal and informal distance and SC orientation. Yu et al. (Citation2018) explored the effect of data-driven SC capabilities on financial performance based on the resource theory view. They analyzed the SCR capacity, defined as a capacity that fosters coordination and integration between partners to develop collaborative processes. Yu et al. (Citation2019) studied the influence of environmental scanning on the SCR, considering the definition of environmental scanning as ‘scanning for information about events and relationships in a company’s outside environment, the knowledge of which would assist top management in its task of charting the company’s future course of action’. Sharma et al. (Citation2020) proposed two SCRFs based on an SLR of responsiveness. In the first framework, the response is influenced by innovation, collaboration, and process flexibility. In the second, it is influenced by service, customer relationship management, and customer commitment. Asamoah et al. (Citation2021) designed a framework for determining the influence of SCR on the ability of companies to attract, satisfy, and retain customers based on the idea that the response capacities of the operation system and supplier network drive the response capacity of the company logistics system. Raghuram and Saleeshya (Citation2021) designed a framework for examining the effect of combining material flow, information flow, delivery time, and general capabilities on the response capacity of a textile SC. The framework was designed with a holistic view of the SC—improving responsiveness. The response concept visions were studied from the perspectives of logistics and SC using a framework proposed by Richey et al. (Citation2022). The study concluded that SCR is a multidimensional concept encompassing the adaptability, flexibility, agility, improvisation, and resilience of the SC. Saïah et al. (Citation2022) studied the contribution of modular processes to the SCR of Médecins Sans Frontières during the COVID-19 pandemic. Aspects, such as architecture, interfaces, and standardization of modules facilitated the response. By contrast, resource orchestration influences the visibility, alignment, and impact of modularity on the SCR. Xu et al. (Citation2022) laid the foundations for reforming the global SC after the COVID-19 pandemic. They designed a framework in which management attitudes, the improvement of logistics processes, demand forecasts, and data analysis influence the SCR.

4. SCRF analysis

The context of the research in which SCRF were proposed covers strategic, operational, SC process, and chain management support issues. The strategic themes in which SCRFs were identified were customer and competitor response, response assessment, and manufacturing plant reshoring. Operational issues, such as order fulfillment, response to disruptions, and operational performance have been addressed. The chain processes in which frameworks have been proposed were research and development, supplier, manufacturing, retail, and logistics, as well as lean, agile, flexible, and modular processes. Regarding support for response management, frameworks have been proposed on issues, such as chain management, response determinants, the functional orientation of the chain, communication systems, data management, integration, coordination, organizational structure, and aspects affecting the response and relational capabilities of the chain. Column 3 of Appendix B shows the theme of the chain in which the frameworks analyzed in this study were proposed.

Ninety percent and 10% of the research conducted on the SCR have been in the manufacturing and service sector industries, respectively. The manufacturing industries included electrical, textile, automotive, and chemical. The service industries included consulting, logistics service providers, and product consumer companies. Column 4 of Appendix B indicates the industry sector covered in the research that proposed the frameworks analyzed in this study.

Regarding the level of SC addressed and the scope of the framework, it was identified that 32 and five SCRFs were analyzed as a chain and function, respectively. Chain analysis was performed because the use of the research methods, such as surveys, questionnaires, interviews, case studies, and focus groups, involved members of various functions of the chain. Column 5 of Appendix B shows the level of analysis of the SC. Concerning the scope of the frameworks, 62% of the frameworks were identified as strategic, 19% were operational, and 19% combined strategic and operational SC aspects. Column 6 of Appendix B shows the scope of the frameworks analyzed in this study.

The coherence between the SCR definitions and SCRF structure was analyzed to verify that the SC aspects comprising the SCR definition also comprise the framework. Accordingly, based on the definitions of the SCR, the SC responds to changes in the demand, market, business conditions, and environment. However, among the SCRFs examined in this study, 36 did not have components identifying what the SC responds to; only the framework proposed by Kritchanchai and MacCarthy (Citation1999) had a component called stimulus. The word stimulus broadens the SCR to the previously mentioned changes and encompasses the response to threats, opportunities, and SC disruptions.

Moreover, the objectives that the SC intends to achieve with the response differed in definition and SCRF. For example, in the SCR definition proposed by Kritchanchai and MacCarthy (Citation1999), the goals that the SC intended to achieve with the response were not identified, whereas the framework included a component for SC goals. Saad and Gindy (Citation2007) included the goals component of the SC in their framework. However, in their SCR definition, they did not identify what objective the SC intends to achieve with the response. Gunasekaran et al. (Citation2008) included the objective of creating wealth for shareholders in their SCR definition; however, this objective did not appear in the SCRF. Regarding the SCR evaluation, Wong et al. (Citation2006) did not define the SCR, making it difficult to understand the factor being evaluated.

Based on the outlined information, it can be inferred that the lack of coherence between the definitions and SCRF components could imply that the response does not contribute to achievement of the SC objectives, and the response given using the framework does not coincide with the concept of response in the definition.

In the 22 documents defining the SCR concept and proposing SCRFs, the response was understood as an ability in 14 definitions, an extent in four, a speed in three, and a process in one. SCR as an ability implies that the SC can develop the ability to respond. SCR as an extent or a speed facilitates the assessment and evaluation of the response. SCR as a process is based on the concept that the SC adapts processes, such as design, supply, manufacturing, transportation, and distribution to respond to a stimulus. In addition, it includes the previously mentioned notions and implies that SC managers establish relationships to plan, execute, evaluate, and improve their responses.

5. Proposal of a conceptual framework for SCR

The first part of this section shows the process followed by the authors to select the components of the new SCRF. The second part describes each of the components. Components are understood as SC aspects comprising the framework.

5.1. Components of the new SCRF

The SCRF components were defined based on the three criteria emerging from the analysis of the documents described in Section 4: (1) The SC aspects comprising the SCR definition will also be part of the framework; (2) the SCR is a process; and (3) the SCRF is usable in any SCR situation.

To fulfill criterion 1, the SCR was first defined, and then the SC aspects comprising the definition were identified. This study used the SCR definition proposed by Díaz Pacheco and Benedito (Citation2022)—the ability to respond to the stimuli received by one or more members of the chain by applying reactive and/or proactive strategies to adapt their activities within a given time frame, in a way that allows evaluation and the achievement of certain goals. Based on this definition, the authors of this study identified six SC aspects as components of the new SCRF: (1) the stimulus to which the SC responds; (2) the strategy that the SC uses to respond, whether reactively or proactively; (3) strategic, tactical, or operational decisions that managers make to adapt the SC activities such that it can respond to the stimulus; (4) the time horizon in which the response is given (long-, medium-, or short-term); (5) the goals that the SC intends to achieve with the response; and (6) the evaluation of the response.

The concept of an SCR process was developed based on the SOR framework. According to Mehrabian and Russell (Citation1974), the SOR model suggests that the environment stimulates the organism. The organism, accepting such stimuli, produces a response through an internal process. In this study dealing with SCR, the three components of the SOR framework were understood as follows: (1) Stimulus is defined as the factors, events, and issues that have or could have an impact on system activities and expected or desired goals. Stimuli are the major factors driving any firm to respond and hence provide the impetus to develop responsiveness capabilities (Kritchanchai & MacCarthy, Citation1999); (2) Stephens et al. (Citation2022) stated that in the SOR framework, the organism acts in a dynamic and constantly changing environment comparable to the execution of SC processes by companies; and (3) the SC responds to a stimulus through an internal decision-making process.

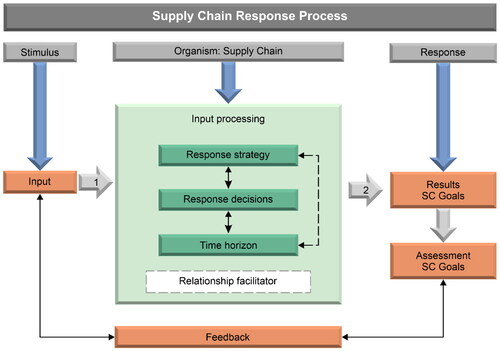

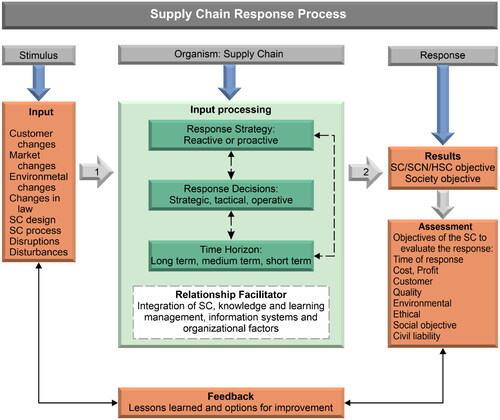

The response process is based on six steps: (1) process input, (2) input processing, (3) process output, (4) process evaluation, (5) process feedback, and (6) relationship facilitators. All stimuli to which the SC responds comprise the process input. The input processing is performed based on three aspects: (i) the response strategy with which the SC will respond; (ii) decisions that will be made in the response; and (iii) the time horizon in which it will respond. The goals that the SC intends to achieve with the response comprise the outcome and evaluation of the response process. The feedback components of the response process include positive or negative experiences and response improvement options. Considering that executing a process implies that the SC managers establish relationships either between the SC members, between the SC and providers, or between the SC and clients, the new framework included a relationship-facilitator component. The SC aspects facilitating decision-making in the SCR process are identified through the relationship facilitator. shows the complete structure of the proposed SCRF.

The following describes the SCR process based on the frame structure shown in . The response process begins when the SC managers detect a stimulus to which they must respond. Detection is done based on the analysis of internal and external information to the SC. Based on the results of the information analysis, the managers will decide on three aspects of the response process: (1) the reactive or proactive strategy that the SC will use in the response; (2) the level of decisions that the response requires (strategic, tactical, or operational); and (3) the time horizon in which the response will be given (long-, medium-, or short-term). The SC managers establish relationships in this decision-making process. Therefore, the relationship facilitator component shows SC aspects that help establish and improve relationships between SC members to facilitate decision-making in the SCR process. Executing these three decisions produces a result. The result is linked to the goals that the SC intends to achieve with the response. The response is evaluated based on the results obtained. The response is evaluated with SC indicators and indicators of the SC processes involved in the response. The indicators used in the response evaluation are qualitative or quantitative. Feedback on the response process is made after evaluating the response. Feedback implies identifying the positive or negative experiences occurring in the response and represents the options for improving future SC responses.

In , arrow 1 indicates that the decision-making of the response process is performed using the information with which the stimulus is detected. In the decision-making, the double-arrow-headed lines indicate that one decision influences the others. Arrow 2 indicates that a result is obtained by executing the decisions made to respond. The results obtained with the response are the fulfillment of the objectives of the SC and the impact on society of the response.

The response is then evaluated based on the results; therefore, an arrow leaves the results and reaches the evaluation. The arrow that leaves the evaluation and arrives at feedback and the arrow that leaves feedback and arrives at stimulus detection show that feedback is made on the entire response process.

5.2. Description of the components of the new SCRF

This section describes the components of the proposed SCRF.

5.2.1. Input

The input to the SCR process is the stimulus affecting the SC. According to Bak (Citation2021), the stimulus affects the internal states of the individual business and asks ‘why the supply chain must transform?’ The SC responds to internal and external stimuli. External stimuli include changes in government laws, suppliers, the SC of the competition, customer requirements, demand, and helping people affected by disasters, such as earthquakes, tsunamis, epidemics, or financial crises. Internal stimuli include unforeseen machine failure, changes in raw materials and supplies, absence of personnel from the company, and loss of contact with the client. shows some stimuli that affect the SC. Column 1 of shows the name of the stimulus; Column 2 shows the type of stimulus, whether external or internal to the SC; and Column 3 shows the impact of the stimulus on the chain.

Table 1. Classification and impact of stimuli that affect the SC.

The aforementioned stimuli do not constitute the totality of the stimuli to which the SC responds; however, they make it easier to demonstrate that the SC responds to stimuli other than demand changes.

5.2.2. Response strategy

The SC responds to the received stimuli either reactively or proactively (Sharifi and Zhang, Citation1999). A proactive strategy is executed when the SC managers apply their knowledge and experience to force changes both inside and outside the SC. For example, based on the lessons learned in the SCR to the increased demand for personal protective equipment (PPE) during the COVID-19 pandemic, the SC applies proactive strategies to improve the design, manufacture, and distribution of PPE to respond to future epidemics. By contrast, a reactive strategy is executed when the SC managers do not anticipate the stimuli that will affect the SC. The SC responds reactively to sudden disasters and unexpected production line stoppages.

5.2.3. Response decisions

The decisions made to respond to a stimulus are linked to the types of decisions made in the SC, whether strategic, tactical, or operational. Ivanov (Citation2010) stated that planning decisions must be interrelated at all decision-making levels. Strategic decisions define the future of the SC. An example of a strategic decision in response to increased demand in geographical areas that are not currently covered by the SC is deciding between installing a new production plant or establishing a new distribution center. Tactical decisions allow the allocation of resources to implement strategic decisions. A continuation of the example of a tactical decision is assigning customers to production plants or assigning customers to be supplied by a specific distribution center. Operational decisions make it easier to perform day-to-day work. An example of an operational decision is assigning order delivery routes to drivers. In response to unforeseen stimuli, such as a natural disaster, decisions are made in line with government entities, the military, Red Cross, and other aid and cooperation entities.

5.2.4. Time horizon

According to Meyr et al. (Citation2008), SC processes are planned in the long-, medium-, and short-term. Long-, medium-, and short-term planning cover periods of over three years, between three months and three years, and between a few hours and several weeks, respectively, depending on the context in which the SC executes its processes. Examples of applying the SCR time horizon are described as follows: The SC responds in the long- and medium-terms to stimuli, such as changes in customer preferences, leading to the development of a new product. By contrast, a short-term response is given to a change requested by the client, either in the number of units to be produced or delivery time. Lotfi et al. (Citation2022) used a short-term strategy called ‘vendor inventory management’ in planning the response to uncertainties and disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic in a hospital SC.

5.2.5. Relationship facilitator

SC members establish relationships that facilitate decision-making in response to a stimulus. Khouja et al. (Citation2021) defined facilitator as ‘factors, environmental or intrinsic to the company, that facilitate the development and empowerment of interorganizational relationships’. Four relationship facilitators were included in the proposed framework: (1) SC integration, (2) knowledge and learning management, (3) information systems (ISs), and (4) organizational factors.

SC integration facilitates interaction and collaboration between SC members to unite efforts that guarantee the fulfillment of the decisions made to respond to a stimulus. SC integration occurs with suppliers, customers, and between SC processes. In all three cases, integration implies coordinating and sharing of resources.

Knowledge and learning management facilitates further development of the following three SC aspects for SC managers: (1) applying the knowledge accumulated in previous responses to the response given to a stimulus, (2) promoting the assimilation and dissemination of new knowledge generated in the SCR, and (3) facilitating the adaptation of knowledge to various responses provided by the SC. Knowledge and information management also contribute to consensus decision-making among SC members and encourage SC learning to improve the response to the stimuli it receives.

ISs facilitate information exchange between SC managers to adjust SC activities to the response to a stimulus. ISs capture, store, manipulate, and communicate data converted into information used by managers in the SCR. The visibility and transparency of information strengthen relationships between members participating in the response.

Organizational factors facilitate relationships between SC managers involved in the response to a stimulus because they promote values, such as truth, commitment, agreements, and cooperation, among SC members. Based on organizational factors, SC managers establish relationships to share goals, decisions, and ways of evaluating their responses.

An example of using relationship facilitators was observed in the SCR to the requirement to ensure food distribution during the COVID-19 pandemic. Distribution and retail processes were integrated in response to this requirement. The processes were integrated through information sharing between retailers and distributors. The information shared by the retailers with the distributors included sales data and storage capacity information. Organizational factors, such as trust and cooperation, also contributed to establishing food-delivery schedule agreements. The managers of the distribution processes and retailers trusted and cooperated with each other to comply with the agreements in line with protection measures against the spread of COVID-19. Knowledge and learning management occurred from two perspectives: (1) SCs that shared their experience in response to previous epidemics, such as H1N1 and the Ebola virus and (2) SCs that shared their experience with other SCs in decision-making to preserve the health of delivery vehicle drivers. The IS of the SC supported information sharing on the demand, consumption, perishability of products, and availability of vehicles and drivers. The veracity of the information provided by each SC member, fulfillment of commitments in the purchase and delivery of products, and cooperation between the SC members are the organizational factors contributing to a timely SC response.

5.2.6. Results

The results obtained by the SC with the response to a stimulus are associated with the fulfillment of certain objectives. In this regard, Corominas (Citation2013) reported that there are many kinds of SCs with different objectives, and many objectives as partners may coexist in the SC. For example, Lotfi et al. (Citation2021) included objectives such as, minimizing costs, environmental emissions, energy consumption, and employment in the results obtained from the response to challenges and disruptions in the SC of a car assembler. Therefore, the results achieved with the response are divided into two categories. (1) results contributing to the fulfillment of the objectives of the SC, SC network (SCN), or humanitarian SC (HSC), and (2) results that impact society. shows the results of the SCs identified in the documents presenting SCRFs. Columns 1 and 2 show the results associated with the SC. Column 3 shows the results that impact society. However, the list of results can be increased in each category according to the context to which the responses are made.

Table 2. Results of the SCR.

5.2.7. SCR evaluation

Von Falkenhausen et al. (Citation2017) stated that responsiveness is a suitable measure for assessing the ability of an SC to contribute to the bottom line or for setting customer-related performance targets. Accordingly, the SCR is evaluated from two perspectives: (1) fulfillment of the objectives of the SC, SCN, or HSC and (2) fulfillment of social objectives. Evaluating the fulfillment of the SC objectives after responding to a stimulus depends on the objectives set by the SC managers in strategic, tactical, and operational planning. For example, strategic objectives evaluated after a response to a stimulus are profit maximization, cost minimization, CO2 emission minimization, and customer service maximization. Objectives to be evaluated in tactical planning include production and inventory turnover maximization. Operational planning objectives include minimizing the amount of defective product per shift, maximizing package delivery per route, and reducing the time of nonactivity of an IS. SC managers evaluate the response to stimuli, such as changes in customer preferences, by analyzing the fulfillment of sales and repurchase goals for a product or service. In addition to the fulfillment of the SC objectives, satisfaction of objectives, such as satisfying urgent demands for water, food, clothing, and shelter for those affected by events, such as disasters, is also evaluated.

The results that impacted society during the COVID-19 pandemic were evaluated. For example, the confinement caused by the spread of COVID-19 created the fear of food and beverage shortages in supermarkets. The company evaluated whether there was a shortage at the time of purchasing these products. The social recognition of an SC, SCN, or HSC was evaluated by the SC managers through opinions and comments extracted from social networks, web pages, and opinion columns published in magazines and newspapers.

5.2.8. Feedback

Feedback is a positive or negative criticism of the response of an SC to a stimulus. The feedback components are the lessons learned (lele) and options for improvement. In the context of the SCR, lele is the knowledge that SC managers acquire through reflection on the factors contributing to positive or negative responses to stimuli. According to Hannan et al. (Citation2021), lele further enhance the ability to respond to everyday challenges. Therefore, lele encourage identifying success factors, deficiencies, and problems of the response, show the strategies that can be repeated in other SC responses, and save time and money for the SC. Improvement options are opportunities for the SC to increase responsiveness. Improvement options come from various sources, such as observations, data analysis, process design, attention to suggestions, and expertise.

An example of lele is that of the automotive SC that recognized that the best strategies to mitigate the risk caused by COVID-19 were to develop localized supply sources and use advanced Industry 4.0 technologies. Both strategies were executed in other responses. The automotive SC also learned that cooperation among SC members contributed to the business survival. In addition, an improvement option was identified in the mass customization process and coordination between the company and supplier. Both enhancement options increased market responsiveness. shows the detailed components of the SCR process, as previously described.

6. Discussion

Proposing an SCRF applied in response to any stimulus implied understanding the concept of the SCR as a process. According to Richey et al. (Citation2022), SCR is a process that entails adaptations within the chain. In the response process used to create the framework, tailoring was performed in response strategies, decisions, and the time horizon to simultaneously reach SC objectives and response recipient expectations. Understanding the response as a process extends the conclusion of Qrunfleh and Tarafdar (Citation2013) that SCR is an important indicator of how well the SC strategy fulfills its objectives. The response understood as a process shows that it is dynamic and occurs according to the characteristics of the stimulus to which it responds; the indicator shows the response as a static number. Ebrahim et al. (Citation2014) studied the manufacturing response based on the concept of input and output systems. The system components included drivers, enablers, measures, and impacts of the response. However, the framework lacked aspects, such as input processing, evaluation, feedback, and relationships between system components. The SCRF proposed in this study addresses these deficiencies. Bode and Macdonald (Citation2017) stated that the response stages are recognition, diagnosis, development, and implementation. By contrast, in the proposed framework, the response stages include recognition and detection of the stimulus, adaptation of the chain aspects to respond, results, evaluation, and feedback of the process. The authors believe that evaluation and feedback are significant for improving the response process.

Concerning the components comprising the framework, it was observed that the frameworks proposed by Reichhart and Holweg (Citation2007) and Sinha et al. (Citation2015) indicated that the response to any stimulus is given using the same chain aspects. By contrast, the proposed framework facilitates using various chain aspects in the response. The aspects to be used to respond are selected according to the strategy type, decisions, and time horizon that the response requires, strengthening the view of organizational response. Díaz Pacheco and Benedito (Citation2023) confirmed that the response that the SC provided to the increased demand for alcohol and antibacterial gel during the COVID-19 pandemic implied using various strategies, decisions, and time horizons. Moreover, the entire organization participated in the response. Accordingly, Cai et al. (Citation2016) suggested that organizational response facilitates rapid reaction to changes affecting the SC. Do et al. (Citation2021) stated that the reactions of the SC are either threats or opportunities implying the modification of the SC processes. The frameworks proposed by Catalan and Kotzab (Citation2003) and Wong et al. (Citation2006) evaluated the response based on the manufacturing process and demand components. By contrast, in the proposed framework, the response evaluation includes environmental, ethical, civil, and social responsibility aspects. Therefore, the new aspects incorporated in the response evaluation facilitate the fulfillment of the internal and external objectives of the chain. The 37 frameworks analyzed in this study lacked a component dealing with lele and response improvement. The lele from responses given to a stimulus identify practical and useful actions that can be replicated in other responses in the chain. The improvement options increase the efficiency and quality of the SCR and help achieve the objectives of the chain and response beneficiaries.

7. Conclusions

This study analyzed 37 documents defining SCR and proposing SCRFs. A new framework with the following characteristics was proposed based on the analysis results: First, is the coherence between the SC aspects comprising the definition and framework components; Second, the SCR is regarded as a process; and Third, the framework applies to any response situation addressed by the SC. In addition, the framework extends the theory of SCR and serves as a guide for SCR planning.

This study is limited in the following aspects: (1) the criteria used to select the documents, because some documents contributing to the identification of SCRF could have been omitted; and (2) the criteria used to analyze the documents identified in the SLR, because some SC aspects could have been biased or omitted, which should have been part of the SC components of the proposed SCRF. The following scopes for future research are proposed to overcome these limitations: (i) multicriteria techniques must be used to select the documents that propose SCRFs; (ii) text analysis techniques must be applied to identify the SCRF components; (iii) the usefulness of the SCRF in SC processes must be verified, such as product design, retail, distributor–retailer dyads, or product design–manufacturing; (iv) a procedure that facilitates the use of the SCRF must be designed; and (v) alternatives for evaluating the usability of the SCRF must be proposed.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Scopus database.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Raúl Antonio Díaz Pacheco

Raúl Antonio Díaz Pacheco is an associate professor at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Palmira campus. He holds a Master’s degree in engineering. His areas of interest in teaching and research are operations management, operations research, and supply chains. His research is conducted in the society, economy, and public policy research groups. The subject investigated in this document paves a way for research on the concept of supply chain response understood as a process that includes evaluation and feedback on the response.

Ernest Benedito

Ernest Benedito has focused his research on modeling and solving supply chain design and management problems related to strategic capacity planning, green logistics, urban logistics, and quality control.

References

- Asamoah, D., Nuertey, D., Agyei-Owusu, B., & Akyeh, J. (2021). The effect of supply chain responsiveness on customer development. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 32(4), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLM-03-2020-0133

- Bak, O. (2021). Understanding the stimuli, scope, and impact of organizational transformation: The context of eBusiness technologies in supply chains. Strategic Change, 30(5), 443–452. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsc.2466

- Bode, C., & Macdonald, J. R. (2017). Stages of supply chain disruption response: Direct, constraining, and mediating factors for impact mitigation. Decision Sciences, 48(5), 836–874. https://doi.org/10.1111/deci.12245

- Bode, C., Wagner, S. M., Petersen, K. J., & Ellram, L. M. (2010). Understanding responses to supply chain disruptions: Insights from information processing and resource dependence perspectives. Academy of Management Journal, 54(4), 833–856. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23045114 https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.64870145

- Cai, Z., Huang, Q., Liu, H., & Liang, L. (2016). The moderating role of information technology capability in the relationship between supply chain collaboration and organizational responsiveness: Evidence from China. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 36(10), 1247–1271. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-08-2014-0406

- Catalan, M., & Kotzab, H. (2003). Assessing the responsiveness in the Danish mobile phone supply chain. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 33(8), 668–685. https://doi.org/10.1108/09600030310502867

- Corominas, A. (2013). Supply chains: What they are and the new problems they raise. International Journal of Production Research, 51(23–24), 6828–6835. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2013.852700

- Davis-Sramek, B., Omar, A., & Germain, R. (2019). Leveraging supply chain orientation for global supplier responsiveness: The impact of institutional distance. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 30(1), 39–56. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLM-09-2017-0225

- Díaz Pacheco, R. A., & Benedito, B. E. (2022). An evolutionary concept analysis of the supply chain response. In F. Chakherlouy & M. Habib (Eds.), The 2nd International Conference on Advanced Research in Supply Chain Management. Diamond Scientific Publishing. https://doi.org/10.33422/2nd.supplychainconf.2022.08.010

- Díaz Pacheco, R. A., & Benedito, E. (2023). Supply chain response during the COVID-19 pandemic: A multiple-case study. Processes, 11(4), 1218. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr11041218

- Do, Q., Mishra, N., Wulandhari, N. B. I., Ramudhin, A., Sivarajah, U., & Milligan, G. (2021). Supply chain agility responding to unprecedented changes: Empirical evidence from the UK food supply chain during COVID-19 crisis Item. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 26(6), 737–752. https://doi.org/10.1108/SCM-09-2020-0470

- Ebrahim, Z., Ahmad, N. A., & Muhamad, M. R. (2014). Understanding responsiveness in manufacturing operations. Science International (Lahore), 26(5), 1663–1666.

- Eng, T.-Y. (2005). The Influence of a firm’s cross-functional orientation on supply chain performance. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 41(4), 4–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-493X.2005.04104002.x

- Ghosh, A., Das, S., & Deshpande, A. (2014). Effect of responsiveness and process integration in supply chain coordination. IUP Journal of Supply Chain Management, 11(1), 7–17.

- Gilal, F. G., Zhang, J., Gilal, R. G., Gilal, R. G., & Gilal, N. G. (2017). Supply chain management practices and product development: A moderated mediation model of supply chain responsiveness, organization structure, and research and development. Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Systems, 16(01), 35–56. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219686717500032

- Gough, D., Oliver, S., & Thomas, J. (2017). An introduction to systematic reviews (2nd ed., J. Seaman & A. Owen, Eds.). SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Grant, C., & Osanloo, A. F. (2016). Understanding, selecting, and integrating a theoretical framework in dissertation research: Creating the blueprint for your “house”. Administrative Issues Journal, 4, 12–26. https://doi.org/10.5929/2014.4.2.9

- Gunasekaran, A., Lai, K. H., & Edwin Cheng, T. C. (2008). Responsive supply chain: A competitive strategy in a networked economy. Omega, 36(4), 549–564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omega.2006.12.002

- Halldórsson, Á., & Arlbjorn, J. S. (2005). Research methodologies in supply chain management-What do we know? In H. Kotzab, S. Seuring, M. Müller, & G. Reiner (Eds.), Research methodologies in supply chain management: In collaboration with Magnus Westhaus (pp 107–122). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/3-7908-1636-1_8

- Hannan, R. J., Lundholm, M. K., Brierton, D., & Chapman, N. R. M. (2021). Responding to unforeseen disasters in a large health system. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy: AJHP: Official Journal of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, 78(8), 726–731. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajhp/zxaa358

- Hayat, K., Abbas, A., Siddique, M., & Cheema, K. U. R. (2012). A study of the different factors that affect supply chain responsiveness. Academic Research International, 3(3), 345–357.

- Homburg, C., Grozdanovic, M., & Klarmann, M. (2007). Responsiveness to customers and competitors: The role of affective and cognitive organizational systems. Journal of Marketing, 71(3), 18–38. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.71.3.18

- Ivanov, D. (2010). An adaptive framework for aligning (re)planning decisions on supply chain strategy, design, tactics, and operations. International Journal of Production Research, 48(13), 3999–4017. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207540902893417

- Khouja, A., Lehoux, N., Cimon, Y., & Cloutier, C. (2021). Collaborative interorganizational relationships in a project-based industry. Buildings, 11(11), 502. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings11110502

- Kim, D., Cavusgil, S. T., & Calantone, R. J. (2006). Information system innovations and supply chain management: Channel relationships and firm performance. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 34(1), 40–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070305281619

- Kim, D., & Lee, R. P. (2010). Systems collaboration and strategic collaboration: Their impacts on supply chain responsiveness and market performance. Decision Sciences, 41(4), 955–981. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5915.2010.00289.x

- Kim, M., Suresh, N. C., & Kocabasoglu-Hillmer, C. (2013). An impact of manufacturing flexibility and technological dimensions of manufacturing strategy on improving supply chain responsiveness: Business environment perspective. International Journal of Production Research, 51(18), 5597–5611. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2013.790569

- Kritchanchai, D., & MacCarthy, B. L. (1999). Responsiveness of the order fulfillment process. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 19(8), 812–833. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443579910274419

- Lotfi, R., Kargar, B., Rajabzadeh, M., Hesabi, F., & Özceylan, E. (2022). Hybrid fuzzy and data-driven robust optimization for resilience and sustainable health care supply chain with vendor-managed inventory approach. International Journal of Fuzzy Systems, 24(2), 1216–1231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40815-021-01209-4

- Lotfi, R., Sheikhi, Z., Amra, M., AliBakhshi, M., & Weber, G. W. (2021). Robust Optimization of Risk-Aware, Resilient and Sustainable Closed-Loop Supply Chain Network Design with Lagrange Relaxation and Repair and Optimization. International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications. https://doi.org/10.1080/13675567.2021.2017418

- Malik, M., Gahlawat, V. K., Mor, R. S., Dahiya, V., & Yadav, M. (2022). Application of optimization techniques in the dairy supply chain: A systematic review. Logistics, 6(4), 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics6040074

- Mandal, S. (2015). An empirical-relational investigation on supply chain responsiveness. International Journal of Logistics Systems and Management, 20(1), 59–82. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJLSM.2015.065964

- Matos, C. A. d., & Krielow, A. (2019). The effects of environmental factors on B2B e-services purchase: Perceived risk and convenience as mediators. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 34(4), 767–778. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBIM-12-2017-0305

- Mehrabian, A., & Russell, J. A. (1974). An approach to environmental psychology. In An approach to environmental psychology. The MIT Press.

- Meyr, H., Wagner, M., & Rohde, J. (2008). Structure of advanced planning systems. In Stadtler, H., & Kilger, C. (Eds.), Supply chain management and advanced planning (pp. 109–115). Berlin Heidelberg: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-74512-9_6

- Moradlou, H., Backhouse, C., & Ranganathan, R. (2017). Responsiveness, the primary reason behind re-shoring manufacturing activities to the UK: An Indian industry perspective. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 47(2–3), 222–236. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPDLM-06-2015-0149

- Nehzati, T., Dreyer, H. C., Strandhagen, J. O., Gotteberg Haartveit, D. E., & Romsdal, A. (2014). Exploring responsiveness and flexibility in multisite production environments: The case of Norwegian dairy production. Advanced Materials Research, 1039, 661–668. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.1039.661

- Okoli, C. (2015). A guide to conducting a standalone systematic literature review. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 37(1), 879–910. https://doi.org/10.17705/1CAIS.03743

- Qrunfleh, S., & Tarafdar, M. (2013). Lean and agile supply chain strategies and supply chain responsiveness: The role of strategic supplier partnership and postponement. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 18(6), 571–582. https://doi.org/10.1108/SCM-01-2013-0015

- Rajagopal, P., Azar, N. A. Z., Bahrin, A. S., Appasamy, G., & Sundram, V. P. K. (2016). Determinants of supply chain responsiveness among firms in the manufacturing industry in Malaysia. International Journal of Supply Chain Management, 5(3), 18–24.

- Raghuram, P., & Saleeshya, P. G. (2021). Responsiveness model of textile supply chain-a structural equation modelling-based investigation. International Journal of Services and Operations Management, 38(3), 419–440. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJSOM.2021.113605

- Rana, S. M. S., Osman, A., Abdul Manaf, A. H., Solaiman, M., & Abdullah, M. S. (2016). Supply chain strategies and responsiveness: A study on retail chain stores. International Business Management, 10(6), 849–857. https://doi.org/10.3923/ibm.2016.849.857

- Reichhart, A., & Holweg, M. (2007). Creating the customer‐responsive supply chain: A reconciliation of concepts. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 27(11), 1144–1172. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443570710830575

- Richey, R. G., Roath, A. S., Adams, F. G., & Wieland, A. (2022). A responsiveness view of logistics and supply chain management. Journal of Business Logistics, 43(1), 62–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbl.12290

- Saad, S. M., & Gindy, N. N. Z. (2007). The future shape of the responsive manufacturing enterprise. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 14(1), 140–152. https://doi.org/10.1108/14635770710730982

- Saïah, F., Vega, D., de Vries, H., & Kembro, J. (2022). Process modularity, supply chain responsiveness, and moderators: The Médecins Sans Frontières response to the Covid-19 pandemic. Production and Operations Management, 32(5), 1490–1511. https://doi.org/10.1111/poms.13696

- Salam, M. A., & Banomyong, R. (2003). An investigation of supply chain responsiveness in the Thai Textile Industry. In 8th Logistics Research Network Conference (pp. 29–36). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/229005387

- Sharma, D., Taggar, R., Bindra, S., & Dhir, S. (2020). A systematic review of responsiveness to develop future research agenda: A TCCM and bibliometric analysis. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 27(9), 2649–2677. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-12-2019-0539

- Sharifi, H., & Zhang, Z. (1999). A methodology for achieving agility in manufacturing organisations. International Journal of Production Economics, 62(1–2), 7–22. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443570010314818

- Sinha, A., Swati, P., & Anand, A. (2015). Responsive supply chain: Modeling and simulation. Management Science Letters, 5(6), 639–650. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.msl.2015.4.001

- Sinkovics, R. R., Jean, R. J. B., Roath, A. S., & Cavusgil, S. T. (2011). Does IT integration enhance supplier responsiveness in global supply chains? Management International Review, 51(2), 193–212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-011-0069-0

- Soni, G., & Kodali, R. (2013). A critical review of supply chain management frameworks: Proposed framework. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 20(2), 263–298. https://doi.org/10.1108/14635771311307713

- Stephens, A. R., Kang, M., & Robb, C. A. (2022). Linking supply chain disruption orientation to supply chain resilience and market performance with the stimulus–organism–response model. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 15(5), 227. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm15050227

- Thatte, A. A. (2013). Supply chain responsiveness through modularity based manufacturing practices: An exploratory study. Journal of Applied Business Research (JABR), 29(3), 743–764. https://doi.org/10.1049/ic:19980093

- Thatte, A. A., Rao, S. S., & Ragu-Nathan, T. S. (2013). Impact of SCM practices of a firm on supply chain responsiveness and competitive advantage of a firm. Journal of Applied Business Research (JABR), 29(2), 499–530. https://doi.org/10.19030/jabr.v29i2.7653

- Tiwari, M. K., Mahanty, B., Sarmah, S. P., & Jenamani, M. (2013). Modeling of responsive supply chain (1st ed.). Taylor and Francis Group.

- von Falkenhausen, C., Fleischmann, M., & Bode, C. (June 6, 2017). Performance outcomes of responsiveness: When should supply chains be fast? Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2985445 or https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2985445

- Wong, C. Y., Stentoft Arlbjørn, J., Hvolby, H. H., & Johansen, J. (2006). Assessing responsiveness of a volatile and seasonal supply chain: A case study. International Journal of Production Economics, 104(2), 709–721. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2004.12.021

- Xu, X., Sethi, S. P., Chung, S. H., & Choi, T. M. (2022). Reforming global supply chain management under pandemics: The GREAT-3Rs framework. Production and Operations Management, 32(2), 524–546. https://doi.org/10.1111/poms.13885

- Yu, W., Chavez, R., Jacobs, M. A., & Feng, M. (2018). Data-driven supply chain capabilities and performance: A resource-based view. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, 114, 371–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tre.2017.04.002

- Yu, W., Chavez, R., Jacobs, M., Wong, C. Y., & Yuan, C. (2019). Environmental scanning, supply chain integration, responsiveness, and operational performance: An integrative framework from an organizational information processing theory perspective. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 39(5), 787–814. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-07-2018-0395

Appendix A

shows the documents selected using the SLR. Column 1 indicates the author, Column 2 the year of publication, and Column 3 the academic journal in which the document was published. Each row represents a single document.

Table A1. Documents that discuss SCR and propose SCRF.

Appendix B

shows the SCRF aspects that were analyzed. Columns 1 and 2 show the author of the document and publication year. Column 3 lists the topics of the chain in which the frameworks analyzed in this study were proposed. Column 4 shows the industries studied in the investigations in which the SCRFs were proposed. Column 5 shows the level of analysis of the SC. Column 6 shows the scope of the frameworks investigated in this study.

Table B1. Analysis of frameworks for SCR.