Abstract

Drawing upon the resource-based view of the firm, this article employs this perspective to examine how new venture adaptiveness and innovative ambidexterity mediate the relationship between entrepreneurial bricolage and new venture growth within Bangladesh’s Ready-Made Garment Industry. The research employed purposive, convenience and snowball sampling techniques to gather data from 303 individuals engaged in wholesale and retail businesses. The study’s findings indicate a positive correlation between entrepreneurial bricolage and new venture growth. Moreover, the mediating effects of new venture adaptiveness and innovative ambidexterity in the relationship between entrepreneurial bricolage and new venture growth are statistically significant. This article proposes a set of tactics aimed at enhancing resource reconfiguration through adaptability and explores novel approaches to optimize resource effectiveness. The study offers substantial insights into new venture growth that could prove valuable to policymakers, entrepreneurs and authorities operating within Bangladesh’s Ready-Made Garment Industry.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

New enterprises play a pivotal role in creating job opportunities, fostering innovation and promoting regional progress. However, these initiatives often experience more significant fluctuations in growth rates compared to well-established organizations. Factors such as entrepreneurial bricolage, new venture adaptiveness and innovative ambidexterity significantly influence the growth of these new ventures (Khattak & Ullah, Citation2021; Wang et al., Citation2021; Wiratmadja et al., Citation2021; Yu et al., Citation2020). Nevertheless, the existing body of literature lacks depth in exploring the intricate decision-making processes that lead to diverse strategic options for the expansion of new ventures. This study aims to investigate the decision-making processes of new venture entrepreneurs and their significance in achieving growth. Yu et al. (Citation2020) emphasized the importance of new initiatives in propelling economic development in developing nations despite the prevalence of failures within this sector. According to a Startup Genome study, the failure rate among start-ups is notably high, with nine out of ten start-ups failing, while only two out of ten new firms face failure within their initial year of operation (Aryadita et al., Citation2023). Moreover, research conducted by Alva et al. (Citation2021) suggests that a lack of job prospects motivates individuals to engage in entrepreneurial endeavors, fostering job creation and contributing to the economic advancement of nations.

The pursuit of new initiatives is driven by the need to meet marketplace demands and overcome hurdles. In this context, the ability to develop and adapt becomes crucial in establishing a sustained competitive advantage for these ventures (Yu et al., Citation2020).

Organizations must adapt to survive during unpredictable crises, which often have widespread visibility and the potential for catastrophic consequences (Thakur & Hale, Citation2022). Adaptability is critical in all business activities, regardless of a company’s offerings. Entrepreneurial ecosystems showcase adaptability through continual modifications, whereas an organization’s adaptability ties strongly to its grasp of markets, technology, products, services and clientele. For new firms, adaptability and flexibility are vital in highly competitive environments shaped by technological revolutions and globalization (Wiratmadja et al., Citation2021). Additionally, innovation has emerged as a key factor for organizations to expand, evolve and endure in fiercely contested markets. Historical evidence highlights crises as catalysts for innovative ideas. Implementing these innovative solutions significantly contributes to well-being, both domestically and in professional settings. Resources play a pivotal role in facilitating sustainable innovation. The field of innovation management emphasizes integrating exploratory and exploitative breakthroughs for a sustained competitive advantage (Tu & Wu, Citation2021). Pro-environmental organizations possess commercial resources but encounter limitations in financial and technical resources for effective sustainability promotion (Iqbal et al., Citation2021). Consequently, the presence of sufficient tangible and intangible resources significantly influences the growth rate of a nascent enterprise (Khattak & Ullah, Citation2021). Similarly, newly founded ventures require substantial resources like financial capital, human capital, knowledge, information and specialized skills for viability and expansion (Davidsson & Honig, Citation2003). The Resource-Based View (RBV) enhances performance and competitive advantage by leveraging tangible and intangible resources (El Nemar et al., Citation2022). According to RBV, acquiring, bundling and effectively utilizing resources are essential for creating a competitive edge edge (Muneeb et al., Citation2023).

This research article asserts that entrepreneurial managers in nascent enterprises can strategically utilize entrepreneurial bricolage to overcome resource limitations and foster business growth. While the potential advantages of employing bricolage in competitive markets for nascent enterprises are recognized, there remains a gap in research examining the specific contributing factors to its overall impact (Singh et al., Citation2022). Adaptability’s importance transcends a company’s offerings; it’s crucial in all activities. Entrepreneurial ecosystems showcase adaptability by continually adjusting to their environment (Roundy et al., Citation2018). A company’s adaptability is closely linked to its understanding of markets, technology, products, services and customers (Chang & Hughes, Citation2012). Factors such as technological revolution, globalization and adaptability become paramount for new firms’ survival in highly competitive environments (Yu et al., Citation2020). The field of innovation management increasingly emphasizes integrating exploratory and exploitative breakthroughs for sustained competitive advantage (Zhang et al., Citation2023). ‘Ambidexterity’ refers to firms proficient in resource use, engaging in extensive exploration beyond their operational boundaries (Ceptureanu et al., Citation2022; Khan et al., Citation2021; Kortmann, Citation2015; Lin et al., Citation2013). This strategy significantly impacts company performance, fosters new product development and effectively manages supply chains (Khan et al., Citation2021). Innovation involves generating unique, hard-to-imitate concepts or products (Ceptureanu et al., Citation2022). Organizational structure indirectly influences firm performance, particularly in the context of exploratory and exploitative innovation (Chang & Hughes, Citation2012). Maintaining a balanced approach between exploitative and explorative learning activities mitigates the risk of continuous success or failure (Santos et al., Citation2021). Existing scholarly work on innovation ambidexterity primarily focuses on large-scale companies, with relatively limited attention given to small and medium-sized enterprises (Wiratmadja et al., Citation2021). Hence, this article aims to answer the question: ‘Under what conditions do bricolage, adaptability and innovative ambidexterity enhance or diminish the competitiveness of early-stage ventures?’ Building upon the work of (Davidsson et al., Citation2017; Jansen et al., Citation2009; Yu et al., Citation2020) on entrepreneurial bricolage’s role in new venture growth, we argue that RBV is crucial in sustaining competitive advantage for retail and wholesale firms through adaptiveness and innovative ambidexterity mediating new venture growth. Entrepreneurial bricolage aids entrepreneurs in devising novel solutions for sustainable new venture growth amid turbulent environments (Han & Xie, Citation2023). This study contributes insights on entrepreneurial bricolage, new venture adaptiveness and innovative ambidexterity in the context of the emerging economy’s ready-made garment industry (RMGI) to the existing literature.

The article is structured as follows: First, we review pertinent literature and formulate hypotheses. We commence with an examination of the RBV theory of sustainable competitive advantage (Barney, Citation1991, Citation2001) for new ventures, followed by an exploration of entrepreneurial bricolage, new venture adaptiveness and innovative ambidexterity. Second, we detail our methodology and present the outcomes of our data analysis. Subsequently, we discuss the implications of our findings, both theoretically and practically. Additionally, we acknowledge the limitations of our study and propose avenues for future research. Finally, we conclude our article by summarizing the key insights and contributions.

2. Literature review

2.1. New ventures

New enterprises, often termed ‘start-ups’, hold a pivotal role in driving innovation and fostering economic progress within societies (Modina et al., Citation2023). However, their establishment and longevity encounter challenges stemming from various factors such as insufficient resources, limited support systems, restricted flexibility, lack of innovativeness and a deficit in entrepreneurial attitude (Khattak & Ullah, Citation2021; Wang et al., Citation2021; Wiratmadja et al., Citation2021). Emerging economies are currently undergoing significant institutional transformations, characterized by legislative changes and the establishment of new market frameworks driven by increased economic development (Marquis & Raynard, Citation2015). Entrepreneurial enterprises, including nascent businesses, are recognized for their proactive and innovative nature, often identifying and exploiting opportunities ahead of competitors (Yu & Wang, Citation2021). There is no universally agreed-upon definition for the concept of a new enterprise, as highlighted by Khattak and Ullah (Citation2021). Typically, new ventures are small enterprises aiming to establish a competitive edge by utilizing resources and selling products within emerging industries, which frequently demand substantial resources, especially during their initial stages (Wang et al., Citation2021). Limited resources in nascent enterprises often lead to challenges in market competitiveness (Yu & Wang, Citation2021). Moreover, the survival challenges encountered in new entrepreneurial ventures necessitate a concentrated effort on knowledge acquisition, emphasizing both immediate and long-term perspectives (Patel et al., Citation2021). Ventures at any stage of their life cycle, as noted by Khattak and Ullah (Citation2021), require adequate tangible and intangible resources. For new ventures, the need for sufficient capital becomes even more critical to ensure their market longevity (Wu et al., Citation2023). Despite the notable failure rates of new initiatives, their significant role in the economic advancement of developing countries remains crucial (Yu et al., Citation2020). However, for new businesses to secure adequate resources, possessing certain capabilities like innovativeness, risk-taking and proactiveness is essential (Khattak & Ullah, Citation2021).

2.2. Entrepreneurial bricolage

The limitations posed by restricted resources underscore the importance of incorporating resourceful behavior in entrepreneurial endeavors within entrepreneurship theories (Steffens et al., Citation2022). Bricolage has been identified as a viable strategy enabling entrepreneurs to achieve financial gains while effectively navigating resource constraints and enhancing their psychological capital (Alva et al., Citation2021; Purnamawati et al., Citation2022; Wang et al., Citation2021). Utilizing bricolage enables firms to capitalize on emerging opportunities despite having minimal resources, as highlighted by Iqbal et al. (Citation2021). Baker and Nelson (Citation2005) emphasized the significance of entrepreneurial bricolage within this context, prioritizing resource orchestration to restructure and redistribute existing resources to achieve objectives. The study by Yu et al. (Citation2020) unpacked considerable practical significance, offering guidance for new businesses in developing economies to use entrepreneurial bricolage for growth and effective responses to environmental volatility. Similarly, Cai et al. (Citation2019) suggested that leveraging limited resources for emerging opportunities enhances an organization’s adaptive capacities, and thus, enables effective competitiveness to resource-abundant international organizations. Additionally, organizations with high bricolage capability, as noted by Iqbal et al. (Citation2021), benefit from improvisation and experimental learning strategies, generating cost-effective solutions with added value. Alva et al. (Citation2021) argued that entrepreneurship involves strategically navigating resource limitations and exploiting possibilities through effective resource utilization. Steffens et al. (Citation2022) highlighted bricolage as a contributing factor to the competitiveness of fledgling initiatives, especially for operational ventures anticipating expansion. Entrepreneurial bricolage has emerged as a pertinent approach to exploring the interplay between limited resources and entrepreneurial capacity (Bhardwaj et al., Citation2023). To delve deeper into the entrepreneurial bricolage perspective in varied situations, business scholars and practitioners should examine both exploratory and exploitative innovation processes in the growth of new ventures. This comprehensive approach is crucial as the adaptability of new ventures significantly impacts their success.

2.3. New venture adaptiveness

The concept of adaptation, initially introduced by Charles Darwin in 1859 (Peltoniemi & Vuori, Citation2014), holds paramount importance for organizations in navigating environmental shifts and acquiring knowledge through experiential methods. This process involves adjusting to circumstances while acknowledging the entity’s constraints (Zapata-Cantu et al., Citation2022). To effectively adapt, organizations must meticulously evaluate specific components of their environment requiring modification to accommodate new circumstances (Tabas et al., Citation2020). The actions of individual agents, enhancing their adaptability to various external circumstances, demonstrate the potential adaptability within entrepreneurial ecosystems (Roundy et al., Citation2018). A positive correlation exists between an organization’s adaptability level and the knowledge possessed by management and employees concerning the company’s markets, technology, products, services and clients (Chang & Hughes, Citation2012). Emerging firms need to adjust their resource allocation and operational strategies to effectively respond to external environmental shifts. The convergence of technological advancements and globalization is expected to usher in a paradigm shift in the competitive landscape, emphasizing the critical role of adaptation for the sustainability of nascent firms (Yu et al., Citation2020).

2.4. Innovative ambidexterity

Academic research on innovation management and strategy has increasingly emphasized the significance of blending exploratory and exploitative breakthroughs for sustained competitive advantage (Kortmann, Citation2015). In parallel, ‘ambidexterity’ characterizes companies effectively utilizing resources while conducting extensive investigations beyond their operational boundaries (Ceptureanu et al., Citation2022; Khan et al., Citation2021; Kortmann, Citation2015; Lin et al., Citation2013). This approach has garnered attention for its impact on critical aspects such as knowledge acquisition, enhancing firm performance, fostering product innovation and streamlining supply chain management (Khan et al., Citation2021). Innovation encapsulates the iterative process of generating original ideas or developing new products that outpace rivals (Ceptureanu et al., Citation2022; Yodchai et al., Citation2022). There’s a growing body of literature exploring innovation ambidexterity, reflecting a firm’s capacity to pursue both exploratory and exploitative activities at heightened levels (Ceptureanu et al., Citation2022; Chang & Hughes, Citation2012; Khan et al., Citation2021; Kortmann, Citation2015; Lin et al., Citation2013). Exploration-driven innovation aims at enhancing existing resources or technology, while exploratory innovation focuses on acquiring novel knowledge and intelligence for integrated systems (Ceptureanu et al., Citation2022; Haider et al., Citation2023). To avoid being trapped in a cycle of success or failure, maintaining a well-balanced strategy that integrates both exploitative and explorative learning activities is crucial for organizational entities (Chang & Hughes, Citation2012; Santos et al., Citation2021). Striking a balance between exploration and exploitation in innovation enables firms to adapt to dynamic environments and refine existing competencies. While firms emphasizing exploitation might encounter challenges due to limited competencies and knowledge resources, a focus on exploration could lead to success in competitive markets (Khairuddin et al., Citation2021). The adoption of ambidexterity is anticipated to enhance the innovation process significantly and strongly support an organization’s innovation endeavors (Ceptureanu et al., Citation2022). However, existing research on innovation ambidexterity has predominantly centered on large and multiunit organizations, overlooking small and medium-sized enterprises (Wiratmadja et al., Citation2021). Therefore, this research initiative aims to play a crucial role in contributing novel ideas and perspectives within the scholarly literature.

2.5. Theoretical background

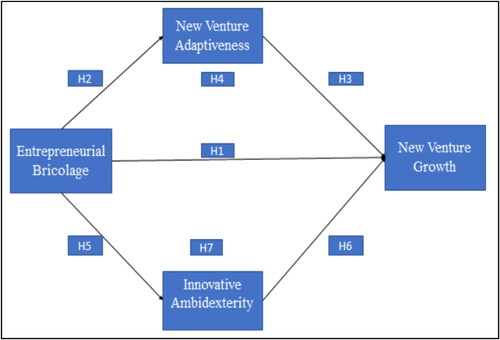

The theoretical framework of this study, grounded in the Resource-Based View (RBV) theory, centers on the correlation between performance and an organization’s resources, which contribute to its strengths and weaknesses, ultimately shaping the organization’s boundaries. RBV theory posits that both tangible (e.g. finance, technology, machinery) and intangible (e.g. human capital, information, skills) resources can bolster performance and competitive advantage (Barney, Citation1991, Citation2001; Wernerfelt, Citation1984). Over the last three decades, scholars in strategic management and business have underscored the significance of RBV in fostering innovative performance and influencing outcomes, particularly in understanding the role of tangible and intangible resources in firm growth and survival (Khattak & Ullah, Citation2021). As per Wang et al. (Citation2021), effectively acquiring, bundling and utilizing resources are pivotal in establishing a competitive edge. Newly established ventures necessitate significant resources like financial backing, human capital, knowledge, information and specialized skills for their sustenance and expansion (Khattak & Ullah, Citation2021). The genesis of new ventures primarily focuses on precise resolutions to discern the requirements and challenges in the marketplace (Waqar et al., Citation2020). Given this focus, both growth and adaptiveness serve as crucial indicators of sustainable competitive advantage for new ventures (Yu et al., Citation2020). Prior research also highlights bricolage as a systematic approach to resource reconfiguration, leveraging scientific cognition—referred to as the ‘science of the concrete’—based on intuitive investigation and analogies to forecast outcomes (Tsilika et al., Citation2020). Resources, whether tangible or intangible, are within the organization’s control. To secure enduring competitive advantages, possessing both types of resources is essential (Greco et al., Citation2013). The current study’s framework establishes a correlation between the potency, capacity and proactive utilization of resources, culminating in the development of enduring competitive advantages that enhance overall competitiveness. These discussions have led to hypotheses reflected in the proposed conceptual model depicted in .

This study focused on entrepreneurs within Bangladesh’s ready-made garments (RMG) industry, specifically in the retail and wholesale sectors, owing to the industry’s significant role in the country’s economy. The RMG industry has been instrumental in propelling Bangladesh’s economic growth and the ‘Made in Bangladesh’ label has bolstered the international reputation of its products. Despite resource constraints, Bangladesh has sustained an average annual GDP growth rate of 6% and has notably improved social and human welfare indicators. Emerging four decades ago, the RMG industry has evolved into Bangladesh’s primary economic engine. Contributing 11.2% to the country’s GDP, it generates 84% of revenue through exports, totaling $31.45 billion in 2020–2021. With approximately 4.2 million employed in RMG, of which 1.8 million are men and 2.5 million are women, it significantly contributes to women’s economic empowerment (Hossain et al., Citation2021; Islam & Halim, Citation2022). According to the Bangladesh Bank’s quarterly review on RMG for April-June FY’22, the industry accounted for 9.25% of the overall GDP in FY22. Moreover, Bangladesh’s RMG exports generated USD 42,613.15 million, marking a substantial 35.47% increase from the previous fiscal year. Bangladesh’s export-oriented industrialization, heavily reliant on RMG, introduces macroeconomic risks despite a shift from agricultural to manufactured raw materials in the import basket. The Bangladesh Bank’s quarterly review on RMG indicated that the United States, Germany, UK, Spain, France, Italy, Netherlands, Canada and Belgium were key RMG export markets. These nine countries accounted for 90.43% of April–June FY22 exports, totaling USD 9,084.71 million. Although RMG export sales to these nations decreased by 2.45% from the previous quarter, they surged by 40.81% from the preceding fiscal year. The recent growth and profit gains in Bangladesh’s RMG sector are promising. Encouraging innovation and digitization within the RMG sector could bolster export competitiveness and further development.

2.6. Development of hypotheses

2.6.1. Impact of entrepreneurial bricolage on new venture growth

The term ‘Entrepreneurial Bricolage’ (EB) describes a resourceful approach used by new and expanding businesses to thrive in their ventures (Fu et al., Citation2020). It involves skilfully utilizing existing resources to tackle novel challenges, often stretching the conventional boundaries of these resources (Davidsson et al., Citation2017). This method empowers organizations to address a wide array of new challenges by cleverly leveraging existing resources and ingeniously integrating additional resources for cost-effective solutions (Davidsson et al., Citation2017). Prioritizing and employing entrepreneurial bricolage can significantly facilitate the successful initiation of a new venture. The practice of bricolage aids new ventures in seizing expansion opportunities, thereby accelerating their growth (Scuotto et al., Citation2023). Several factors support the strong link between entrepreneurial bricolage and the evolution of new ventures. Yu et al. (Citation2020) identified two critical requirements for achieving growth in new ventures: enhancing the novelty of opportunity creation and alleviating resource constraints while capitalizing on opportunities. Entrepreneurial bricolage enables the integration of existing and external resources, often low-cost or free, amplifying the competitive advantage of businesses (Baker & Nelson, Citation2005). Accumulating an essential resource base and restructuring it to enhance organizational capacity is vital for businesses to augment their competitive advantage (Steffens et al., Citation2022). In underdeveloped countries, newly established enterprises face a higher likelihood of failure compared to those in developed countries, primarily due to constraints in underdeveloped strategic factor markets hindering business expansion and fulfilling resource needs for pursuing new business prospects (Yu et al., Citation2020). Entrepreneurial bricolage thus becomes instrumental in fostering the growth of new firms by providing supplementary opportunities for expansion. Beyond addressing resource constraints, it actively contributes to the growth and success of new enterprises (Bhardwaj et al., Citation2023). Entrepreneurs can capitalize on entrepreneurial opportunities to further develop their firms as part of the final phase of the bricolage process (Alva et al., Citation2021). Therefore, our hypothesis is:

H1: Entrepreneurial bricolage positively influences new venture growth.

2.6.2. Impact of entrepreneurial bricolage on new venture adaptiveness

In the business realm, ‘bricolage’ embodies the process of innovating new approaches by adapting existing ones and devising fresh procedures to effectively leverage available resources. This strategy seamlessly integrates diverse resources, enabling inventive responses to emerging problems or opportunities (Davidsson et al., Citation2017). In entrepreneurship, bricolage prompts action and active engagement in opportunities, motivating new businesses to thrive in dynamic environments (Frese & Gielnik, Citation2023). Employing entrepreneurial bricolage aids in the development of service-based businesses by leveraging connections with a diverse array of stakeholders, fostering ongoing engagement to gain a comprehensive understanding of necessary environmental changes (Arslan et al., Citation2023). This approach encourages young businesses to expand their horizons, proactively seeking changes in their surroundings and identifying potential customers (Yu et al., Citation2020). It involves prompt action initiation fuelled by the belief that viable solutions can be discovered (Davidsson et al., Citation2017). Contrarily, adaptability refers to a company’s capacity to adjust resource allocation and operational routines in response to external changes (Zhou et al., Citation2022). Given the imminent technological revolution and globalization, adaptability becomes indispensable for the survival of new businesses (Akpan et al., Citation2022). Entrepreneurial bricolage demonstrates a positive impact on adaptability, notably in its ability to embrace market unpredictability. Therefore, entrepreneurial bricolage can serve as a catalyst for promoting adaptability in new businesses, enabling effective responses to emerging challenges and opportunities in the dynamic business landscape (Yu et al., Citation2020). Enhancing environmental monitoring efficacy and the agility to respond swiftly to changing circumstances are pivotal to achieving this goal. Building on previous research recognizing the significance of bricolage in fostering competitiveness across various enterprises, Steffens et al. (Citation2022) emphasized its central role in enabling ventures to remain competitive. Based on this understanding, the primary focus of this study centers on establishing a positive association between entrepreneurial bricolage and the adaptiveness of new ventures. Therefore, it is hypothesized.

H2: Entrepreneurial bricolage positively influences new venture adaptiveness.

2.6.3. Impact of new venture adaptiveness on new venture growth

The adaptability of a firm’s new venture involves actively embracing evolving opportunities, strategically aligning actions with available resources, seizing favorable conditions swiftly and avoiding limited paths (Weiss et al., Citation2023). This multifaceted strategy ensures the firm’s agility, responsiveness and strategic acumen while navigating the complexities of a dynamic business environment (Yu et al., Citation2020). Resource replacement stands as a strategic approach utilized by companies to overcome challenges or seize new opportunities that may otherwise be unfeasible, ultimately enhancing organizational competence (Santos et al., Citation2021). Adaptiveness, conversely, refers to the capability of new ventures to adjust their resource allocation and operational routines in response to environmental changes (Yu et al., Citation2020). The liabilities associated with newness often elevate the risks of failure for young ventures when they experiment with new products and markets, leading to potential inefficiencies and hurdles in establishing new rules and routines (Patel et al., Citation2021). The process of establishing a new business encompasses a multifaceted and interconnected set of organizational activities (Hopp & Sonderegger, Citation2015). In this light, a venture must continuously adapt to the evolving competitive landscape through experimentation (Patel et al., Citation2021). When faced with environmental shifts, a business ecosystem responds by displaying emergent properties, engaging in co-evolutionary processes and undergoing self-organization (Peltoniemi & Vuori, Citation2014). Moreover, Yu et al. (Citation2020) anticipated that the technological revolution and globalization would usher in a new competitive landscape, emphasizing the necessity for adaptiveness in ensuring the survival of new ventures. Given that competitive advantages significantly contribute to a firm’s favorable performance and growth (Fu et al., Citation2020), Our hypothesis proposes that new venture adaptiveness positively influences new venture growth.

H3: New venture adaptiveness positively influences new venture growth.

2.6.4. Mediating impact of venture adaptiveness

Numerous studies on bricolage highlight its crucial role in enabling survival under adverse conditions. Furthermore, bricolage proves to be a valuable approach in coping with the vulnerability of nascent ventures, as it creatively utilizes low-cost and underutilized resources to generate new value and gain a competitive advantage (Fu et al., Citation2020). This adaptive approach helps individuals facing crises comprehend their surroundings, fuse cognition and action for prompt responses and adapt despite constraints (Alva et al., Citation2021). Success against even a small number of incumbents by a resource-constrained company demonstrates effective bricolage (Steffens et al., Citation2022). Entrepreneurial bricolage (EB) strategically aids nascent enterprises in navigating challenges stemming from resource scarcity, enhancing adaptability and fostering growth potential (Yu & Wang, Citation2021). The extent to which a new business modifies its resource allocation and operational routines to align with evolving environmental conditions serves as an indicator of its adaptability (Makkonen et al., Citation2014). EB presents a unique resource utilization approach crucial for new ventures’ success (Fu et al., Citation2020). EB demands continuous environmental monitoring and resource rearrangement to adapt to changes (Ma & Yang, Citation2022). Yu et al. (Citation2020) argued that entrepreneurial bricolage challenges established norms regarding resource utilization and integration, potentially leading to the emergence of new norms and rules. The resource allocation and integration method of entrepreneurial bricolage could yield varying impacts on the growth rate of new ventures (Fu et al., Citation2020). Past studies affirm that entrepreneurial bricolage positively influences the expansion of new firms and their ability to adapt to environmental changes, especially in emerging economies (Alva et al., Citation2021). Hence, our hypothesis suggests that new venture adaptiveness mediates the influence of entrepreneurial bricolage on new venture growth.

H4: New venture adaptiveness mediates the influence of entrepreneurial bricolage on new venture growth.

2.6.5. Impact of entrepreneurial bricolage on innovative ambidexterity

The majority of nascent firms aim to bolster their competitiveness against established counterparts (Steffens et al., Citation2022). Entrepreneurial bricolage stands as a resourceful process involving the creative combination of available resources, disregarding environmental limitations to maximize their utility (Ciambotti et al., Citation2021). It is a dynamic problem-solving approach marked by resourceful creativity (Davidsson et al., Citation2017). Although not creating additional resources, entrepreneurial bricolage fosters innovative resource combinations through creative utilization (Fu et al., Citation2020). Innovation represents a process enabling companies to attain sustained competitive advantages through unique products or services, distinct capabilities and knowledge acquisition (Ceptureanu et al., Citation2022). Wang et al. (Citation2021) highlighted how entrepreneurial bricolage aids new ventures in overcoming resource constraints and enhancing innovation. Conversely, innovation ambidexterity caters to companies seeking a balance between incremental innovation, refining existing offerings and pursuing new opportunities (Khairuddin et al., Citation2021). It is a dynamic capability positioning firms advantageously in terms of competitive edge (Jansen et al., Citation2009; Wiratmadja et al., Citation2021). Without innovation ambidexterity, firms may struggle to adapt to evolving market demands or forge new avenues for enhanced performance (Chang & Hughes, Citation2012). Past studies indicated that entrepreneurial bricolage fosters innovation in new ventures, suggesting a positive impact (Fu et al., Citation2020). Consequently, we posit that entrepreneurial bricolage positively influences innovative ambidexterity.

H5: Entrepreneurial bricolage positively influences innovative ambidexterity.

2.6.6. Impact of innovative ambidexterity on new venture growth

Innovation stands as a strategic process enabling firms to gain sustainable competitive advantages by creating unique products or services, distinct capabilities and advancements in knowledge and development (Ceptureanu et al., Citation2022). Innovation ambidexterity involves the pursuit of both incremental innovation and the exploration of new prospects (Khairuddin et al., Citation2021). The absence of innovation ambidexterity might hinder firms’ ability to respond to changing market needs or carve new paths for performance improvement (Chang & Hughes, Citation2012). Previous studies have highlighted that small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) face challenges in achieving innovation ambidexterity due to limited managerial expertise, unstructured procedures and less formal coordination systems (Wiratmadja et al., Citation2021). However, the level of innovation that can be fostered heavily relies on top management’s vision, support for experimental approaches and endorsement of sustainable ideas (Iqbal et al., Citation2021). Innovation ambidexterity assumes different roles in new ventures compared to established firms (Ceptureanu et al., Citation2022). It is level within an organization largely hinges on primary resources and the effectiveness of technological, human resources and environmental factors (Wiratmadja et al., Citation2021). Adaptability within a firm appears to be linked to its capacity to achieve innovation ambidexterity (Khairuddin et al., Citation2021). According to Jansen et al. (Citation2009), innovation ambidexterity encompasses exploratory and exploitative innovation. Exploratory innovation involves meeting demands beyond current offerings by introducing novel products and services through inventive distribution channels (Bachmann et al., Citation2021). Exploitative innovation, conversely, focuses on continuous improvement of existing products, operational efficiency and expanding services for current clients (Jansen et al., Citation2009). Our hypothesis offers that innovative ambidexterity is positively associated with new venture growth.

H6: Innovative ambidexterity positively influences new venture growth.

2.6.7. Mediating impact of innovative ambidexterity

Entrepreneurial bricolage emerges as a critical facilitator for new ventures, aiding in performance enhancement by alleviating resource constraints and identifying novel opportunities (Wang et al., Citation2021). This resourceful approach to utilizing available resources fosters competitive advantages through the creation of diverse resource combinations and innovative factors that bolster exploratory processes (Fu et al., Citation2020). The innovative potential that arises is significantly shaped by top management’s strategic vision, encouragement of experimental approaches, recognition of innovative solutions and support for sustainable ideas (Iqbal et al., Citation2021; Jansen et al., Citation2009). Despite the substantial resource demands of innovation, firms employing bricolage strategies can augment their innovation outcomes by reconfiguring available resources, even within constraints (Yu & Wang, Citation2021). Entrepreneurial bricolage optimizes resource utilization, fostering diversity and sustained capabilities through consistent application (Fu et al., Citation2020). This approach often involves on-the-spot improvisation and idea generation, encouraging ventures to blend resources creatively without immediate concerns about feasibility (Yu et al., Citation2020). Increased growth expectations widen the resource gap, opening up greater possibilities for resource collaboration and substitution (Steffens et al., Citation2022). However, Alva et al. (Citation2021) cautioned against relying solely on bricolage for improvisation, as excessive use might lead to low-quality innovations. Previous studies suggest that innovation ambidexterity mediates the relationship between contextual attributes and firm performance (Chang & Hughes, Citation2012). Furthermore, CD and BD of ambidexterity mediate the positive link between EB and new venture growth (Fu et al., Citation2020). Therefore, our argument shows that innovative ambidexterity serves as a mediator in the positive association between EB and new venture growth.

H7: Innovative ambidexterity mediates the influence of entrepreneurial bricolage on new venture growth.

3. Methodology

3.1. Sampling method and procedure

A comprehensive survey instrument was utilized to collect data from our target respondents, focusing on entrepreneurs within the retail and wholesale sectors operating in the Ready-Made Garment Industry (RMGI) specifically in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Given the specific criteria required for our study and the need for a substantial sample size, relying on a single sampling strategy would have been impractical. Thus, we opted for a combination of sampling methods to ensure the collection of accurate and representative data. Convenience sampling was initially employed to identify individuals who were easily accessible to us (Hossain et al., Citation2023). Subsequently, purposive sampling was used to select individuals who best aligned with the criteria necessary for our study (Maganga & Taifa, Citation2023). Finally, we incorporated snowball sampling (Zickar & Keith, Citation2023) by encouraging participants from our purposive samples to recommend other suitable individuals for participation. This amalgamation of sampling strategies was aimed at assembling a larger and more diverse sample, thereby bolstering the applicability and comprehensiveness of our findings. Previous studies have also acknowledged the effectiveness of employing various non-probability sampling techniques based on the specific requirements of the research (Budin et al., Citation2013; Chong, Citation2012). This combination approach offers a means to gather a more diverse and representative sample, thereby enabling a deeper and more nuanced understanding of the research problem.

To ensure linguistic compatibility, the survey was crafted in Bengali, the predominant language among entrepreneurs in Bangladesh’s Ready-Made Garment Industry (RMGI). The data collection phase spanned the fourth quarter of 2022, specifically from October to December. We enlisted the assistance of five Bangladeshi undergraduate students, whom we trained as enumerators proficient in employing a mix of convenience, purposive and snowball sampling techniques to identify suitable respondents. These enumerators possessed the requisite skills to effectively approach and gather data from the specified participants. Our data collection methods comprised drop-off/pick-up and face-to-face interactions, chosen for their efficacy in maximizing response rates and mitigating non-response bias. Respondents provided comprehensive and easily understandable responses to a standardized questionnaire administered during face-to-face encounters. The enumerators offered real-time support, clarifying any questions or uncertainties respondents had regarding the questionnaire. Moreover, the drop-off/pick-up approach, where surveys were hand-delivered to respondents’ offices, garnered the highest response rates (Allred & Ross-Davis, Citation2011). Face-to-face interactions proved invaluable in conveying the study’s purpose and the significance of participation in both data collection methods. Verbal instructions, detailed in the questionnaire cover letter, contributed to enhanced clarity and compliance. This direct interaction also aided in confirming respondents’ eligibility for the survey (Allred & Ross-Davis, Citation2011). Before the final data collection, a pre-test involving four professionals was conducted to ensure the questionnaire’s quality and clarity. Additionally, a pilot test with 30 participants was undertaken to assess the questionnaire’s reliability and validity. These steps confirmed the content validity and reliability of the data, ensuring the integrity of the final data collection from the targeted respondents.

Out of the 420 targeted respondents identified, 347 responded to the survey, resulting in a total of 303 completed and suitable responses for further analysis after eliminating 44 incomplete surveys. This yielded a response rate of 72.12%, meeting the criteria deemed adequate for PLS-SEM data analysis, as indicated in Hair et al.’s sample size Table (2013). To mitigate the potential issue of common method bias, which can arise in cross-sectional data collection, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted using SPSS. This test assessed all items related to entrepreneurial bricolage, new venture growth, innovative ambidexterity and new venture adaptiveness (Aguirre-Urreta & Hu, Citation2019). The results revealed that the first factor accounted for a variance of 23.44%, well below the 50% cut-off used to detect common method variance (CMV). Among the respondents, a significant portion had 4 to 6 or more than 6 years of work experience and held positions as business owners. Their demographic profile, encompassing gender, age and education, is detailed in .

Table 1. Respondents’ demographic profile.

3.2. Measures

This research utilized a questionnaire-based data collection method, employing reliable and validated questions derived from prior studies. Participants responded on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). presents the list of questions used to measure each research variable. Entrepreneurial bricolage was evaluated using Davidsson et al.’s (Citation2017) nine-item scale, with statements such as ‘We usually find workable solutions to new challenges by using our existing resources’. All items within this scale displayed sufficient factor loadings, warranting no elimination of variables. New venture adaptiveness was assessed via Yu et al.’s (Citation2020) four-item scale, including statements like ‘We allow the business to evolve as opportunities emerge’. No elimination of variables was required as all items showed adequate factor loadings. The assessment of innovative leadership ambidexterity utilized Li et al.’s (Citation2015) eight-item scale, incorporating statements such as ‘Our organization responds to demands that go beyond existing products’. Similarly, all items within this scale displayed satisfactory factor loadings, requiring no elimination. New venture growth was measured through Yu et al.’s (Citation2020) three-item scale, with an example statement being ‘Sales growth’. No variables were eliminated from this scale, as all items demonstrated sufficient factor loadings. Although procedural measures were implemented to mitigate common method variance (CMV), its potential presence was acknowledged due to the use of the same participants across all variables. To evaluate CMV’s impact, the Dziuban and Shirkey’s (Citation1974) ‘Correlation Matrix Process’ (CMP) statistical method was employed. As the major variables displayed correlations below 0.90, CMV was not detected using this method. Additionally, a comprehensive collinearity assessment strategy was employed to further scrutinize CMV.

Table 2. Measurement model.

4. Data analysis and results

Initial descriptive statistics encompassing the organization and respondent characteristics were analyzed using SPSS software. Subsequently, to assess the current study hypotheses, Partial Least Squares-Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) was conducted in SmartPLS version 4, involving two primary components (Becker et al., Citation2023). The first component, the measuring model or external model, represents the initial segment of a measurement system. It delineates the interrelationships among variables within the model. Conversely, the second component, the structural model or internal model, illustrates the connections between two constructs. This can involve exogenous constructs, which are independent variables denoted without arrows pointing towards them, and endogenous constructs, explained by other variables (with arrows pointing towards them). When an endogenous construct falls between two variables, it is transformed into an independent variable in the model.

4.1. Measurement model

Cronbach’s alpha (α) and Composite Reliability (CR) are fundamental measures used to evaluate the reliability and internal consistency of constructs in both formative and reflective models (Hair et al., Citation2021). In this study, all constructs exhibited Cronbach’s alphas above the recommended threshold of 0.70, ranging from 0.781 to 0.903. Additionally, the Composite Reliability scores, ranging between 0.851 and 0.922, exceeded the minimum benchmark of 0.50, indicating robust reliability across all constructs (Hair et al., Citation2021).

To assess the validity of the indicators, factor loadings were computed. demonstrates the convergent validity of the reliability indicators, showcasing item loadings within the range of 0.371 and 0.866. According to Hair et al. (Citation2013), factor loadings between 0.30 and 0.70 should only be removed if doing so improves the Average Variance Extracted (AVE). Furthermore, AVE values should surpass the established threshold of 0.50 for acceptability (Hair et al., Citation2021). Consequently, all constructs within this investigation demonstrated significant convergent validity, ensuring the reliability and accuracy of the measurement model.

The Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) technique, proposed by Henseler et al. (Citation2015), was utilized in this study to assess discriminant validity in two distinct settings. Initially, HTMT was used to establish a threshold value; however, it remains ambiguous when the correlation nears one. Some researchers suggest a threshold value of 0.90, while others propose 0.85 (Roemer et al., Citation2021). Upon determining the threshold value, if the HTMT score exceeds this designated value, it implies a lack of discrimination. Subsequently, discriminant validity was evaluated by examining HTMT values alongside a confidence interval of less than one. When the interval does not encompass one, it indicates clear empirical differentiation between constructs. As depicted in , the HTMT values between the constructs were found to be less than 0.85. Consequently, this study acknowledges and affirms the presence of discriminant validity among the examined constructs.

Table 3. Heterotrait-monotrait ratio.

4.2. Structural equation model

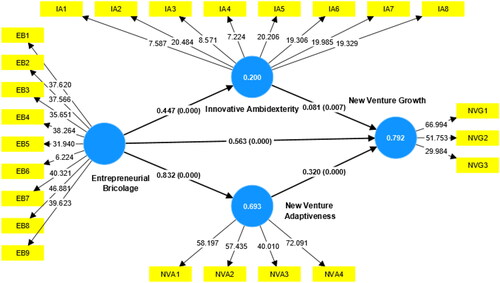

Upon completion of the measurement model, the structural equation model (SEM) was utilized to illustrate the proposed relationships among the constructs. A complete bootstrapping method with 5000 subsamples, a significance threshold set at 5% (β = 0.05) and a two-tailed test were employed to assess the significance level through t-statistics for all paths. Four criteria were used to evaluate the direct and indirect impacts within the SEM framework (Becker et al., Citation2023). To understand the variation across all variables, the R2 values for endogenous latent components were calculated. According to Hair et al. (Citation2021), R2 values of 0.26, 0.13 and 0.09 represent high, moderate and low variations, respectively, depending on the research context. The direct effect model of the present study indicated that innovative ambidexterity (IA) and new venture adaptiveness (NVA) had R2 values of 0.200 and 0.693, respectively, for the endogenous variables. This implies that entrepreneurial bricolage predicted a 20% change in IA and a 69.3% change in NVA. Additionally, the R2 value for new venture growth (NVG) was 0.792, indicating that EB, IA and NVA could predict a 79.2% change in NVG. The model exhibited high predictive accuracy, as illustrated in .

The significance of the research model was further assessed using PLS-predict (Q2) analysis, following the approach outlined by Hair et al. (Citation2021). PLS Predict, a holdout-sample-based method developed by Shmueli et al. (Citation2019), was employed with 10-fold cross-validation and 10 repetitions, resembling real-world use for predicting unobserved variables. This approach allows for item- or construct-level predictions utilizing a boosted logistic regression model. PLS Predict offers a means to gauge a model’s out-of-sample predictive power or accuracy in forecasting outcomes, distinct from conventional measures like predictive significance R2 and predictive relevance (Q2) (Hair et al., Citation2021). In this study, the PLS LV Prediction Residuals exhibited asymmetry. To address this, mean absolute error (MAE) was utilized instead of root mean squared error (RMSE) for comparing PLS with naive linear regression (LM), aligning with the recommendation by Shmueli et al. (Citation2019). All PLS items associated with endogenous variables displayed Q2 values above 0, demonstrating superior predictive power compared to the naive linear regression (LM) benchmark, as illustrated in . Additionally, a model is considered to possess good predictive potential if its MAE (or RMSE) values for all indicators in the PLS-SEM study are lower than those of the naive LM benchmark. In this case, all indicators in PLS exhibited lower MAE values than LM, affirming the robust predictive power of the model. This strong predictive ability suggests its suitability for addressing new cases.

Table 4. PLS predictive relevance (Q2).

presents the direct effect findings, which show that Entrepreneurial Bricolage is positively and significantly associated with linked with new venture growth (β = 0.563, t = 12.626, p < .05). Hence, a 1-unit change in EB leads to a 56.3% change in NVG. Furthermore, the EB on IA (β = 0.447, t = 9.129, p < .05), EB on NVA (β = 0.832, t = 50.199, p < .05), IA on NVG (β = 0.081, t = 2.722, p < .05) and NVA on NVG (β = 0.320, t = 6.311, p < .05) all were positive and significant. Therefore, result revealed that all direct hypotheses H1, H2, H3, H5 and H6 were accepted. Hair et al. (Citation2021) suggested using a cut-off value of 0.02 for a small effect size (f2), 0.15 for a medium and 0.35 for a large. shows that EB has a large influence on NVG (0.465), NVA (2.252) and IA (0.250). However, the mediating variable NVA has medium effect on NVG (0.143), whereas IA has small f2 size (0.024) on NVG.

Table 5. Results of the structural equations model.

Finally, the model also predicted and confirmed that IA and NVA would act as a mediator on the relationship between EB and NVG. shows that the indirect effect of EB on NVG through mediator NVA (β = 0.266, t = 6.246, p < .05) and IA (β = 0.036, t = 2.607, p < .05) both were positive and significant. The results revealed that NVA (26.6%) put high impact than IA (3.6%) on the relationship between EB and NVG. Hence, Hypotheses H4 and H7 both were accepted.

5. Discussion

The purpose of this study is to examine under what conditions bricolage enhance or attenuate the competitiveness of early-stage ventures. Thus, this study seeks to measure entrepreneurial bricolage through the lens of RBV that enhance or attenuate new venture growth mediated by new venture adaptiveness and innovative ambidexterity. Results contribute to the lacuna of the entrepreneurship literature by examining understudied mechanisms following the context of ready-made garment industry (RMGI) businesses in Bangladesh. Our results provide substantial support for the RBV which emphasises the role of NVA and IA as mediators between bricolage and new venture growth. NVA and IA represent resource heterogeneity and the strategic deployment of resources, respectively, to reinforce the RBV’s central notion that competitive advantage and development stem not only from resource acquisition, but also from their dynamic planning, adaptability and innovative use of resources. Aligning closely with the fundamental principles of RBV, the findings deepen our understanding of resource-driven routes to business growth by highlighting how bricolage enables the creative assembly of diverse resources and how NVA and IA are crucial mechanisms for firms to effectively leverage these resources in the context of RMGI. This study showcases the role of entrepreneurial bricolage, new venture adaptiveness and innovative ambidexterity in the ready-made garment industry (RMGI) of developing nations, based on data obtained in Bangladesh. Results shed light on the factors that have contributed to the rapid business expansion in Bangladesh, including the nation’s entrepreneurial spirit.

However, the results indicate that new venture business growth remains a significant challenge that requires extensive research in the context of the RMGI. In this challenging environment, our analysis shows that entrepreneurial bricolage, new venture adaptiveness and innovative ambidexterity can shed light on how emerging economies can thrive by launching new firms. This study is an effort to contribute to the literature on bricolage and dual-skilled entrepreneurs in low-income nations. This study also responds to Fu et al. (Citation2020) call for an in-depth exploration of additional entrepreneurship scenarios with mediating variables between entrepreneurial bricolage-new venture business growth relationship. Thus, we have studied two mediators namely new venture adaptiveness and innovative ambidexterity for entrepreneurial bricolage-new venture business growth relationship.

As hypothesised the positive impact of entrepreneurial bricolage on new venture business growth (H1), the current study’s finding revealed the significant positive influence of entrepreneurial bricolage on new venture business growth, thus, H1 is supported which is in line with many other studies that have found same result in various contexts (Fu et al., Citation2020; Yu & Wang, Citation2021; Yu et al., Citation2020). Likewise, H2 and H3 are related to positive impact of entrepreneurial bricolage on new venture adaptiveness and its impact on new venture business growth, respectively. Previous literature supports these findings that show positive influence of entrepreneurial bricolage on new venture adaptiveness (Yu & Wang, Citation2021; Yu et al., Citation2020), and subsequently, new venture adaptiveness on new venture business growth (Fu et al., Citation2020; Martin et al., Citation2018). Similarly, H4 was also supported in this study because of positive mediation of new venture adaptiveness for entrepreneurial bricolage-new venture business growth relationship. This finding is also consistent with other existing research studies that had concluded or found similar result in various contexts (Fu et al., Citation2020). Moreover, our findings help to bridge the gap between the RMGI and entrepreneurship literatures and provide direction for future studies on new venture adaptiveness and entrepreneurial bricolage in the context of RMGI.

Similarly, H5 was also supported because entrepreneurial bricolage was found to create positive and significant impact on innovative ambidexterity, aligning with findings from similar studies in the field. (Fu et al., Citation2020; Lee & Kreiser, Citation2018). Moreover, innovative ambidexterity was also found to have its positive and significant impact on new venture business growth, thus, H6 was also supported. This finding is also congruent to some other relevant studies as well (Balboni et al., Citation2019; Kurniawan et al., Citation2020; Sijabat et al., Citation2020). H7 was also supported due to positive and significant meditating impact of innovative ambidexterity in entrepreneurial bricolage-new venture business growth relationship. This result is also similar to some other researchers’ studies who reported same result in various contexts (Chang & Hughes, Citation2012; Fu et al., Citation2020). Consequently, our findings opened the black box of relationships between entrepreneurial bricolage and new venture growth. They revealed the crucial roles of new venture adaptiveness and innovative ambidexterity as mediators. This bridges the gap between RMGI and entrepreneurship literature and guides future studies on innovative ambidexterity and entrepreneurial bricolage in the RMGI context.

6. Theoretical implications

Precisely, this study evolves with three theoretical contributions. First, we study entrepreneurial bricolage in the emerging context of retail and wholesale firms operating in RMGI at Dhaka, Bangladesh, which contrasts but enriches the current literature on entrepreneurial bricolage. Although Baker and Nelson (Citation2005) introduced bricolage to strategic research, empirical exploration remains constrained. The impact of entrepreneurial bricolage on new venture growth is also not explicitly examined. But the theoretical model of our study demonstrates how entrepreneurial bricolage, facilitated by combination of existing and other inexpensive (e.g. no or low cost) resources and creative reconfiguration, leads to develop innovative workable solutions which are valuable to encounter a broad range of new challenges. This enhances the rareness and value of resources within the RBV framework by showcasing how retail and wholesale firms can harness combinations of both existing & inexpensive resources to achieve sustainable growth in emerging economies. Additionally, this study enhances our comprehension of the effects of entrepreneurial bricolage by exhibiting its capacity to foster the expansion of new business ventures (An et al., Citation2018; Duymedjian & Rüling, Citation2010; Guo et al., Citation2016; Yu et al., Citation2020). Thus, our study makes an inclusive attempt through integrating entrepreneurial bricolage, new venture adaptiveness, innovative ambidexterity and new venture growth to elucidate the impact of entrepreneurial bricolage on business growth in emerging economies.

Second, our analysis extended the shortcomings of the RBV theory that contributes to the entrepreneurship literature through the impact of entrepreneurial bricolage on new venture business growth by examining the underlying mechanisms, specifically the roles of new venture adaptiveness and innovative ambidexterity, which are critical for achieving business growth in the face of limited resources. This is consistent with previous research by Fu et al. (Citation2020) and Senyard et al. (Citation2010), highlighting the importance of resource allocation for entrepreneurial business growth. Our empirical model emphasizes new venture adaptiveness as a key driver of non-substitutability of resources. Retail and wholesale businesses that skilfully adapt their resource configurations during turbulent periods, showcasing non-substitutable capabilities crucial for new venture, contribute to sustainable future growth. Furthermore, by integrating innovative ambidexterity our model emphasizes the importance of a blend of exploratory and exploitative resource configurations and capabilities to facilitate innovation in production’s efficiency of products and services, new distribution channels and increase economics of scale to capture the existing as well as new opportunities in new markets. This contributes to the theory by suggesting that the simultaneous pursuit of distinct innovation strategies creates complex resource configurations that are imperfectly imitable by competitors, as they need to balance conflicting demands for exploration and exploitation.

Third, our study contributes to the existing research conducted in the ready-made garment industry (RMGI) by investigating the mechanisms of new venture business growth in this industry, which has been under-studied. It is crucial to analyse how new ventures in the RMGI cope with limited resources. By incorporating entrepreneurial adaptiveness and ambidexterity and shedding light on entrepreneurial bricolage in the RMGI, we bridge the gap between entrepreneurship and RMGI studies. Our findings are not limited to the field of RMGI entrepreneurship but are also relevant in various contexts. Entrepreneurial bricolage’s ability to address resource limitations and its effects through ambidexterity and adaptiveness offers promising outcome for entrepreneurship research.

7. Practical implications

The findings of this study have significant implications for entrepreneurs in the ready-made garment industry seeking to leverage entrepreneurial bricolage for new venture growth via the mediating effects of new venture adaptiveness and innovative ambidexterity. The ability of entrepreneurs to reconfigure available resources through specific mechanisms is crucial for new venture growth. This study offers three practical recommendations for entrepreneurs aspiring to grow new ventures in developing economies. First, it demonstrates the efficacy of entrepreneurial bricolage as a growth strategy, particularly for new ventures in developing countries (Yu et al., Citation2020). New businesses should make effective use of the resources that are already available to them and should move quickly into action (rather than persisting over queries about whether an ideal outcome can be produced) by combining and reusing resources that are either already available to them or can be acquired at a low cost (Prabhu & Jain, Citation2015; Yu et al., Citation2020).

Second, this study suggests that the efficacy of entrepreneurial bricolage is contingent upon mediating mechanisms such as new venture adaptiveness and innovative ambidexterity. New venture adaptiveness leads to sustainable competitive advantage because enterprises that can withstand unforeseen challenges and adapt to them have a significantly greater chance of attaining long-term growth. Despite having well-defined plans, unforeseen circumstances can arise, making it crucial for organizations to comprehend how to adapt and be prepared for any challenges. Adopting various business adaptation tactics, such as experimentation, product development and diversification of manufacturing and distribution channels, can prove to be advantageous for organizations operating in any industry, including the ready-made garment industry. The adaptation of a business model necessitates a strategic market plan, an agile organisational structure and efficient transactional capabilities. These flexible characteristics equip businesses to confront a diverse range of commercial challenges. In a dynamic economic environment, enterprises can experiment and adapt in order to remain relevant. As technology scales and becomes more efficient, business adaptation strategies and approaches become increasingly popular and innovative. Similarly, innovative ambidexterity enables organizations to cater to customers’ demands beyond their existing products and successfully commercialize new ones. In addition, organizations can explore new opportunities and distribution channels, make incremental improvements to their products, increase economies of scale in current markets and expand services for current clients. Therefore, entrepreneurs must consider both adaptiveness and innovative ambidexterity in addition to entrepreneurial bricolage to achieve new venture growth.

Third, while both NVA and IA are beneficial, our findings suggest that when firms have the option of pursuing both concurrently, NVA should be prioritised due to its greater impact on new venture growth. Prioritising new venture adaptability (NVA) over innovative ambidexterity (IA) for new venture growth is based on the realisation that adaptability is frequently more important than multitasking. NVA enables a business to rapidly adapt to changing circumstances and capitalise on emerging opportunities. This agility assists in maintaining relevance and capitalising on favourable conditions. IA, conversely, necessitates both the exploration of new ideas and the exploitation of existing strengths, which can squander resources and impede the ability to adapt quickly. In dynamic environments, the capacity to adapt and evolve in response to shifting conditions becomes a crucial success factor. Therefore, emphasising on NVA enables a business to navigate obstacles effectively and maximise available resources, resulting in more sustainable and consequential growth. Adaptability in RMGI industry can be improved by the implementation of government policies that promote adaptability, the development of skills and an openness to change. In addition, encouraging collaborations and the exchange of information among firms operating within RMGI industry could enhance the sector’s overall adaptability and promote opportunities for business growth.

8. Limitations and future research directions

The results of the present study should be considered within the context of its limitations and sets the stage for future studies. First, we operationalized the mechanisms of entrepreneurial bricolage supporting new venture growth using a measure that encompasses exploration and exploitation related to new venture growth, mediated by new venture adaptiveness and innovative ambidexterity. Future investigations could examine additional measures to capture different elements, including cognitive flexibility, emotional flexibility and dispositional flexibility of adaptiveness. Furthermore, it is crucial to consider dimensions of ambidexterity competencies and practices and develop operationalizations for these innovative strategies that are not exaggeratedly specific, warranting their applicability and generalizability in diverse contexts other than individualistic culture. Second, the future research can examine additional mediating variables to further understand the bricolage-new venture growth relationship. For instance, entrepreneurial orientation, network competence, entrepreneurial competencies could be studied as potential mediators between bricolage and new venture growth. These variables provide multiple avenues for bricolage’s resourcefulness and creativity to affect business growth. Such studies would develop theory and help entrepreneurs to enhance sustainable growth strategies in dynamic situations. Third, this study did not consider factors that influence the environment of the emerging context such as security, economic stability, entrepreneurial competencies, innovation enablers and competitive intelligence to analyse mechanisms for the sustainable growth of the new venture. To address this issue, we encourage future researchers to include those factors to generate the outcome. Birkinshaw et al. (Citation2016) suggests that executives should adapt their focus on exploration and exploitation to effectively respond to changing environmental demands. Consequently, we encourage further research into the dynamic balance between exploration and exploitation and its impact on new venture adaptiveness and innovative ambidexterity, ultimately contributing to sustainable new venture growth. Fourth, our results may have limitations in terms of generalizability to enterprises of different sizes and contexts. Therefore, future research could explore different empirical settings, such as large enterprises or other emerging economies where it sustained collectivist culture. Additionally, our sample is predominantly from the garment sector, so further studies are encouraged to investigate the implications of new venture adaptiveness and innovative ambidexterity in firms operating in other economic sectors. Finally, this study was only conducted across Bangladeshi Ready-Made Garments Industry. However, other sectors and matured firms were not included in unit of analysis. Thus, the future researchers should investigate other matured firms in their study operating in different sectors to investigate the predicting and mediating roles of current study’s variables for achieving their growth. Similarly, a comparative study could be more useful across diverse types of firms such as mature firms versus new ventures and microfirms versus small firms etc.

9. Conclusion

This article seeks to enhance the expanding literature by integrating entrepreneurial bricolage, new venture adaptiveness, innovative ambidexterity and new venture growth. It examines the substantial link between entrepreneurs in the retail and wholesale sector of the ready-made garment industry (RMGI) and how entrepreneurial bricolage impacts new venture growth in an emerging economy. Overall, our findings provide a richer breath & depth view into the extent and benefits of bricolage behavior in retail and wholesale sector of RMGI, highlighting the strong relevance of RBV theory in comprehending resource characteristics such as rareness, value, imperfect inimitability and non-substitutability within the unique context of an emerging economy.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Shehnaz Tehseen

Shehnaz Tehseen an Associate Professor at Sunway Business School, Sunway University, Malaysia, holds a Ph.D. in Management. Her extensive academic career is marked by prolific research contributions, with over 90 papers published in various esteemed journals, conferences, and book chapters. She has collaborated with more than 90 researchers worldwide, showcasing her international network and influence in the academic community. Tehseen’s research primarily revolves around Entrepreneurship, Ethnic Entrepreneurship, SMEs, Entrepreneurial Competencies, Women Entrepreneurs, and Entrepreneurial Intention. Additionally, she has made notable contributions to other disciplines such as Marketing, Hospitality, IT, and Human Resource Management. Her work has been published in prestigious journals indexed in Scopus, including the Journal of Small Business Management, Business Process Management Journal, Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration, and more. Noteworthy accolades include receiving the Best Paper Award at ICBSI 2018 and the Emerald Literati Award for Outstanding Paper in the 2020 Emerald Literati Awards, both acknowledgments of her significant contributions to the field of entrepreneurship.

Umar Nawaz Kayani

Umar Nawaz Kayani is currently working as an Assistant Professor at Al Ain University, United Arab Emirates. He is a versatile academician with over a decade of teaching, administrative, and regulatory experience, in tertiary programs. He graduated from Lincoln University, New Zealand with a Ph.D. in Accounting and Finance. Recently, he completed his post-doctoral fellowship at Lincoln University, New Zealand. He has published refereed articles in leading international accounting and finance journals. Besides academia, he also worked as a Quality Assurance and Accreditation Expert for more than 10 years at the Higher Education Commission of Pakistan (HEC).

Syed Arslan Haider

Syed Arslan Haider is a PhD scholar in the Department of Management at Sunway University Business School, Malaysia. He received his BS in Computer Science and Master in Project Management from the Capital University of Science and Technology, Pakistan. He is active in research in the areas of Knowledge management, Innovation, Leadership, Organizational Culture and Project Complexity. His research appeared in good journals such as Journal of Knowledge Management, European Journal of Innovation Management, Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, Journal of Measuring Business Excellence and many others Scopus indexed journals. He is a Project Manager of Soulmate Construction Company in Pakistan.

Ahmet Faruk Aysan

Ahmet Faruk Aysan is a full Professor, Associate Dean for Research at Hamad Bin Khalifa University. He has been the Board Member and Monetary Policy Committee Member of the Central Bank of the Republic of Turkiye and served as a consultant at various institutions such as the World Bank, the Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey, and Oxford Analytica. Dr. Aysan, who has many articles published in reputable academic journals, is a recipient of the Boğaziçi University Awards, and the MEEA Ibn Khaldun Prize. Dr. Aysan is also a Research Associate at the University College London Centre for Blockchain Technologies (UCL CBT), a Research Fellow at the Economic Research Forum, and a Non-resident fellow at the ME Council.

Fatema Johara

Fatema Johara PhD, has been working as an Associate Professor at Bangladesh Army International University of Science & Technology. She did her Ph.D. from Universiti Sains Malaysia, Malaysia. Dr. Johara also did her Master of Philosophy in Management and MBA in Accounting from the University of Chittagong, Bangladesh. Her research interests lie in the areas of Entrepreneurship Development, Talent Management, Employee Engagement, Management Accounting, Strategic management, Organizational behavior, and Islamic Work Ethics. She published a good number of publications in peer reviewed journals and conference proceedings, including in the Journal of Economic Cooperation & Development, International Journal of Sustainable Strategic Management, Journal of Sustainability Science & Management, Global Business and Management Research, etc. She has been acting as a regular reviewer and editor for many international conferences and Journals including International Journal of Islamic Marketing. She can be accessed at [email protected].

Syed Monirul Hossain

Syed Monirul Hossain serves as a Lecturer at the Department of Management within Sunway Business School, Malaysia. Previously, he held faculty positions at Stamford University in Bangladesh and served as a Guest Lecturer at Naresuan University’s Faculty of Business, Economics, and Communication in Thailand. Dr. Hossain holds a BBA degree from Bangladesh, a Master’s degree from the University of Wollongong, Australia, and a PhD in Business Administration from Naresuan University, Thailand. His academic contributions include publications in esteemed journals, book chapters, and paper presentations at national and international conferences such as the Academy of International Business (AIB) and the British Academy of Management (BAM). Dr. Hossain’s research centers on managerial competencies and the impact of informal social networks on human resource management. Additionally, he explores the developmental effects of entrepreneurship and family business, integrating design thinking to facilitate various forms of innovation, establish sustainable new ventures, and promote generational well-being.

Saddam Khalid

Saddam Khalid is an associate professor at the School of Economics and Management, University of Hyogo, Japan, since 2019. He completed his Ph.D. in Business Administration from Osaka University, Japan, in 2019. His research interests include the psychology of entrepreneurship, international entrepreneurship, and entrepreneurship in emerging markets. His research has been published in numerous journals, including the Journal of Business Venturing Insights, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, and the International Journal of Emerging Markets. He is also a member of the Academy of Management, Academy of International Business, and Asia Academy of Management.

References

- Aguirre-Urreta, M. I., & Hu, J. (2019). Detecting common method bias: Performance of the Harman’s single-factor test. ACM SIGMIS Database: The DATABASE for Advances in Information Systems, 50(2), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1145/3330472.3330477

- Akpan, I. J., Udoh, E. A. P., & Adebisi, B. (2022). Small business awareness and adoption of state-of- the-art technologies in emerging and developing markets, and lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 34(2), 123–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/08276331.2020.1820185

- Allred, S. B., & Ross-Davis, A. (2011). The drop-off and pick-up method: an approach to reduce nonresponse bias in natural resource surveys. Small-Scale Forestry, 10(3), 305–318. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11842-010-9150-y

- Alva, E., Vivas, V., & Urcia, M. (2021). Entrepreneurial bricolage: crowdfunding for female entrepreneurs during COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 15(4), 677–697. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEEE-12-2020-0464

- An, W., Zhao, X., Cao, Z., Zhang, J., & Liu, H. (2018). How bricolage drives corporate entrepreneurship: The roles of opportunity identification and learning orientation. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 35(1), 49–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12377

- Arslan, A., Al Kharusi, S., Hussain, S. M., & Alo, O. (2023). Sustainable entrepreneurship development in Oman: a multi-stakeholder qualitative study. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 31(8), 35–59. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOA-11-2022-3497

- Aryadita, H., Sukoco, B. M., & Lyver, M. (2023). Founders and the success of start-ups: An integrative review. Cogent Business & Management, 10(3), 2284451. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2284451

- Bachmann, J. T., Ohlies, I., & Flatten, T. (2021). Effects of entrepreneurial marketing on new ventures’ exploitative and exploratory innovation: The moderating role of competitive intensity and firm size. Industrial Marketing Management, 99, 87–100.

- Baker, T., & Nelson, R. E. (2005). Creating something from nothing : resource construction through entrepreneurial bricolage. Administrative Science Quarterly, 50(3), 329–366. https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.2005.50.3.329

- Balboni, B., Bortoluzzi, G., Pugliese, R., & Tracogna, A. (2019). Business model evolution, contextual ambidexterity and the growth performance of high-tech start-ups. Journal of Business Research, 99(August 2018), 115–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.02.029