Abstract

Propositions in favor of biophysical environmental sustainability have proliferated governance, business and academic debates globally. Initiatives promoting consumer health and environmental preservation have been epitomised through production and marketing of green products. However, the establishment of green brand equity to expedite green purchase has been a widely observed obstacle for most green brands. The study examined the antecedents of green brand equity for organic foods in Zimbabwe. The paper proposed that green satisfaction stimulates development of green trust, green brand image and green brand equity. It also hypothesized that green brand image influences green trust. Green brand image and green trust were modelled to affect green brand equity. The study targeted green consumers who purchased organic foods in the upmarket suburbs in Harare (n = 319). Model validation through Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and covariance based Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) revealed that green satisfaction positively affected green brand image, green trust and green brand equity. Green brand image and green trust also positively influenced green brand equity. The relationship between green brand image and green trust was also positive and significant. The paper flags the multifaceted role of green satisfaction in the development of green brand equity. Findings suggest that green satisfaction provides key leverage for reducing consumer perceived risk and green phobias through green trust and green brand image. Organic food marketers were urged to design a two-fold green value proposition that delivers both functional satisfaction and green fulfilment as drivers for cultivating sustainable green brand equity.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

Sustainability concerns have overwhelmed governance, business and academic discussions in most recent decades (Bekk et al., Citation2016; Butt et al., Citation2016; Ha, Citation2021). Global initiatives that promote consumer health and environmental preservation have been envisaged and operationalised through production and marketing of green products (Shakir et al., Citation2021; Zia et al., Citation2021). Central to green marketing obstacles has been widespread consumer skepticism and low green product uptake (Akturan, Citation2018; Muposhi et al., Citation2015). Most green marketers have faced the challenge of establishing brand equity for their products (Qayyum et al., Citation2022). Notwithstanding, Bekk et al. (Citation2016) and Ha (Citation2021) commend that green brand equity acts as a lever that green brands can utilize to create a sustainable competitive advantage as enables them to attract brand preference and charge a premium.

Green brand equity refers to the intangible assets associated with a green brand, arising from the consumer’s perception of its superior pro-sustainability initiatives (Akturan, Citation2018; Chen & Chang, Citation2013; Ha, Citation2021). There has been protracted claims of green washing on green products amid green marketing efforts (Akturan, Citation2018). Green washing has been defined as consumer misinformation by non green firms that leads to purchase of products that do not fulfill their pro-life and environmental promises at high prices (Chen & Chang, Citation2013). Whilst green brand equity underpins intangible brand value that attracts brand preference, green washing and green confusion significantly diminish green brand equity for green products especially in food markets. This paper examines the key role of green satisfaction in developing green trust and green brand image as important levers for nurturing green brand equity in organic food markets.

Organic foods are one category of green brands confronted with the challenge of consumer skepticism and low product uptake (Janssen & Hamm, Citation2012; Matharu et al., Citation2022; Van Loo et al., Citation2013). The term organic refers to the way that these products are raised and processed. Whilst the parameters vary from country to country, these products must be produced without the use of synthetic herbicides, pesticides, fertilisers and bioengineered genes (Wee et al., Citation2014). Organic food consumption has been strongly urged in order to preserve consumer health through strengthening the immune system, containing natural nutritional properties, improving metabolic processes, improving digestive efficiency and suppressing the development of disease causing organisms (Matharu et al., Citation2022; Rahman et al., Citation2016; Voona et al., Citation2011). Wee et al. (Citation2014) support that organic foods have been recommended pursuant to environmental sustainability, health preservation, better consumer welfare and consumer longevity. Like other green products, organic foods are recognised with green tags, green packaging, green branding or eco branding that distinguishes them from generic products as green brands (Akturan, Citation2018; Ha, Citation2021; Polonsky, Citation1994; Shakir et al., Citation2021).

At the height of the green revolution, proponents of green marketing have extensively recommended consumption of organic foods projected to improve consumer health, life expectancy and keeping a safe physical environment (Misra & Panda, Citation2017; Papista & Dimitriadis, Citation2019; Qayyum et al., Citation2022; Wu et al., Citation2016). To expedite purchase and consumption of organic foods amid intense market competition, green washing, sophisticated, more knowledgeable and health conscious consumers, green brand equity is a key requisite (Butt et al., Citation2016; Reisch & Thogersen, Citation2015). Green brand equity has been cited as a key source of repeat patronage and premium pricing, enhancing sales, profits and competitive advantage (Ha, Citation2021). Consumer purchase preferences towards green brands are enhanced when consumers have perfect knowledge of green brands that offer a unique value proposition embedded in the fulfillment of their pro-health and environmental preservation initiatives (Akturan, Citation2018; Ha, Citation2021; Janssen & Hamm, Citation2012).

Several studies have investigated the antecedents of green brand equity in extant literature (Bekk et al., Citation2016; Butt et al., Citation2016; Esch et al., Citation2006; Fong et al., Citation2014; Ha, Citation2021; Pappu & Quester, Citation2006). However, most of the studies examined the direct effects of green trust, green satisfaction and green brand image on green brand equity. Grounded in the disconfirmation paradigm (Oliver, Citation1980), trust-commitment theory (Morgan & Hunt, Citation1994) and the Consumer Based Brand Equity Model (CBBE) (Keller, Citation1993), this study proposed an integrated framework to determine the antecedents of green brand equity in the context of organic food brands. This study predicted that green satisfaction influences green brand equity directly and through the mediation effects of green brand image and green trust. More so, whilst most researchers examined the effect of brand image on green satisfaction, for example, Shakir et al. (Citation2021) and Wu et al. (Citation2016), this paper proposed that a reciprocal effect of green satisfaction on green brand image exists in organic food markets.

Fewer studies have been conducted within the organic food domain, a distinct market of a credence product category associated with high consumer involvement when selecting brands (Rahman et al., Citation2016). This connotes that consumer behavior in organic food markets may vary relative to other conventional product markets. The objective of this paper was to examine the antecedents of green brand equity in organic food markets, modelling a multifaceted role of green satisfaction. Whilst proposing a direct effect on green brand equity, the key proposition in this paper modelled the effects of green satisfaction on the development of green trust and green brand image.

Amid protracted challenges of green uptake in most consumer markets (Shakir et al., Citation2021; Zia et al., Citation2021), this research brings findings of practical and theoretical significance. Firstly, the study can enlighten green food producers and marketers on the pivotal importance of green value in food products. The paper reminds green marketing firms that the essence of green consumption remains the uptake of the green benefits (good health and environmental preservation). This research can educate organic food marketers on the importance of developing, communicating and fulfilling green value propositions within consumer markets, a multifaceted lever on green brand equity. More so, the findings of this research can be useful to regulators of food products as they seek to scrutinize food quality and enhance consumer protection.

Further, this research hitherto becomes the first to propose a framework that examines the multi-dimensional effect of green satisfaction on green trust, green brand image and green brand equity, through direct and indirect causal relationships. The research connects key theoretical insights from the disconfirmation theory (Oliver, Citation1980), trust-commitment theory (Morgan & Hunt, Citation1994) and the consumer based brand equity model (Keller, Citation1993). Thus, the paper advances empirical green literature on the importance of green satisfaction, green trust, green brand image and subsequent green brand equity in organic food markets. In an under-researched yet important subject area in subsistence markets, this study can provide a key impetus for the advancement of green marketing literature and organic food uptake in subsistence markets. The subsequent sections of this paper cover literature review, materials and methods, results and discussion, conclusions and implications of the study.

2. Literature review

2.1. Green brand equity

Brand equity refers to the added value with which a given brand endows a product (Rossenbaum-Elliot et al., Citation2011, p. 89). Whilst a product offers functional benefits, a brand is a name, symbol or design that enhances the value of a product beyond its functional purpose (Biel, Citation1992). Green brand equity has been defined as the intangible assets of a green brand in terms the embedded value in its pro-health and environmental initiatives (Ha, Citation2021). The added value defines its assets that consumers perceive to be associated with a green brand (Akturan, Citation2018; Bekk et al., Citation2016). Green brand equity reduces consumer perceived risk, enhances brand preference and loyalty, provides meaningful differentiation, attracts a premium price and enhances competitive advantage (Butt et al., Citation2016; Esch et al., Citation2006).

Marketing literature provides several drivers of brand equity across consumer markets. Common in most green marketing studies are green brand image, green trust, and green satisfaction as key determinants of green brand equity (Bekk et al., Citation2016; Butt et al., Citation2016; Ha, Citation2021). To demonstrate that green brand equity and green buying behavior are closely intertwined, the same constructs have also been operationalized as drivers of green buying behavior (Shakir et al., Citation2021). Consumer skepticism, green phobias, lack of trust, green washing and green confusion have been cited as the main reasons for non-purchase of green brands world over (Chen & Chang, Citation2013; Muposhi et al., Citation2015; Rahman et al., Citation2016). Thus, the development of green brand equity can help to induce added value and stimulate brand preference for green brands, especially organic foods. Green brand equity acts as a lever for promoting green product uptake and hence it enhances sales volumes, brand loyalty and adds competitive advantage (Butt et al., Citation2016; Ha, Citation2021).

2.2. Antecedents of green brand equity

Several studies have examined the antecedents of green brand equity in literature (Butt et al., Citation2016; Chen & Chang, Citation2013; Esch et al., Citation2006; Ha, Citation2021). This paper evaluates the effects of green satisfaction, green brand image and green trust in influencing green brand equity of organic foods.

2.2.1. Green satisfaction and green brand image

Green satisfaction refers to the subjective and positive brand judgements by the consumer as a result of fulfilment of pro-environmental initiatives and health promises by a green brand (Ha, Citation2021; Shakir et al., Citation2021). Learning from the disconfirmation theory (Oliver, Citation1980), positive disconfirmation evokes feelings of pleasure, delight, likeness, attachment and preference towards a brand (Chen & Chang, Citation2013; Muposhi et al., Citation2015). Brand performance directly influences customer satisfaction with a brand (Kotler et al., Citation2002). Green performance leads to green satisfaction with a green brand and this creates inextinguishable brand memories which develop into mental images (Butt et al., Citation2016).

Brand experience and brand knowledge are key aspects of brand image (Biel, Citation1992; Rossenbaum-Elliot et al., Citation2011). Green brand image is composed of all brand memories through experiential learning, that a consumer holds with respect to a green brand (Ha, Citation2021; Shakir et al., Citation2021). This includes experiential effects, functional knowledge, performance and related memories held from previous brand engagements (Bekk et al., Citation2016; Keller, Citation1993). These mental images stimulate brand association and purchase intentions whenever the consumer has an encounter with the brand (Pappu & Quester, Citation2006). Thus, green customer satisfaction is positively associated with the development of green brand image. According to Ha (Citation2021), green brand image is the mental perception of a green brand from a customer perspective based on its ability to deliver its green promises. In other words, green brand image is a culmination of green brand positioning over time because it reflects the mental perceptions held by a customer against a green brand.

It conveys green brand image as an experiential outcome which develops over successive interactions with a green brand (Chen & Chang, Citation2013; Shakir et al., Citation2021). Thus, this paper views green brand satisfaction as a key antecedent of green brand image. As a customer builds positive green memories with more green fulfillment and green satisfaction with a brand, positive emotions are triggered when they encounter the green brand and this stimulates purchase intentions (Akturan, Citation2018). Whilst Delafrooz and Goli (Citation2015) revealed the effect of green brand quality on green brand image, their conclusions supported Upamannyu and Bhakar (Citation2014), who confirmed the positive effect of customer satisfaction on green brand image. Thus, with successive experiences of green delight and fulfilment of a green brand’s pro-health promises, favorable green brand memories develop. Given the standpoint, this paper hypothesized that;

H1: Green satisfaction positively influences the green brand image of organic food brands.

2.2.2. Green satisfaction and green trust

Grounded in the trust-commitment theory of relationship marketing (Morgan & Hunt, Citation1994), trust is a key ingredient of any dual value exchange relationship. It is defined as the willingness to commit and a belief that one party will always perform its obligations despite chances of exploiting an opportunistic behavior (Delgrado-Ballester & Munuera-Alemán, Citation2005; Morgan & Hunt, Citation1994; Williamson, Citation1986). According to the social exchange theory (Thibaut, Citation2017), people act in accordance of expectations of associated rewards. In Zimbabwe, trust is a key aspect of the Ubuntu or Huntu cultural domain, a native cultural orientation premised on reciprocation of good deeds and standards of expected behaviors which form the foundations of social and para-social relationships (Nyathi, Citation2008). Thus, in both contexts, trust is a cumulative outcome of past experiences with an object or person. Green trust is a commitment held by a consumer to a green brand, constantly believing that it will always fulfil its pro-health and environmental promises in good faith (Butt et al., Citation2016; Ha, Citation2021).

Based on the transactional cost theory, Williamson (Citation1986) posits that encounters of mutual satisfaction over time strengthen bonds of trust between two exchange parties as they also attempt to reduce brand switching and associated transactional costs. Prior experiences with a green brand create important foundations for the development of green trust (Ha, Citation2021). Successive positive disconfirmation from past green brand experiences can help to develop green brand trust (Bekk et al., Citation2016; Chen & Chang, Citation2013; Ha, Citation2021). Thus, positive past encounters with organic food brands have a high propensity to reinforce of green trust towards them.

More so, the popularity of health conscious consumers amid escalating food borne diseases has invited concerted efforts to improve food safety (De Boeck et al., Citation2017; Rahman et al., Citation2016). Given these trends, consumer sensitivity with food products has been intensified and this suggests that the key role of green satisfaction in building green trust with organic foods has been heightened. Past studies have reported the positive effect of green satisfaction on green trust (Bekk et al., Citation2016; Butt et al., Citation2016; Chen & Chang, Citation2013; Esch et al., Citation2006). Thus, learning from this, the paper also hypothesised that;

H2: Green satisfaction positively influences green trust for organic food brands.

2.2.3. Green satisfaction and green brand equity

Product satisfaction has been the most cited determinant of brand patronage and brand equity (Gronroos, Citation2002; Ha, Citation2021; Kotler et al., Citation2002). Based on the disconfirmation theory (Oliver, Citation1980, Citation1997), green consumers develop positive or negative emotions when they compare their perceived green performance against prior green expectations (Ha, Citation2021; Shakir et al., Citation2021). Thus, with positive experiential effects, green satisfaction can help improve green brand equity. Green satisfaction can help build intangible assets that help reinforce brand favorability through green brand equity (Yasin et al., Citation2007). Against the background of slowly growing confidence in green brands in consumer markets, green satisfaction presents a huge opportunity for developing green brand equity (Chang & Fong, Citation2010; Shakir et al., Citation2021; Zia et al., Citation2021).

Studies by Esch et al. (Citation2006), Chen and Chang (Citation2013), Ha (Citation2021) and Wu et al. (Citation2016) have investigated the influence of green satisfaction on green brand equity. Their findings revealed the positive impact of green satisfaction on green brand equity. They concurred that green satisfaction is a key antecedent of green brand equity and hence it promotes green product uptake. Their findings concurred with Bekk et al. (Citation2016) as well as Pappu and Quester (Citation2006). Based on these claims, green satisfaction can be used to induce green brand preference through the influence of green brand equity in organic food markets. Thus, the study also hypothesised that;

H3: Green satisfaction positively influences green brand equity for organic food brands.

2.2.4. Green brand image and green trust

Customers develop brand knowledge and mental images through their positive experiences with a green brand and they build feelings of trust towards the brand (Padel & Foster, Citation2005; Shakir et al., Citation2021). Key theoretical frameworks, for example, Aaker (Citation1991) and Keller (Citation1993) pinpoint the important role of brand associations in building brand equity, hence brand associations represent the nexus between green brand image and green trust. Reisch and Thogersen (Citation2015) postulate that brand image gives an inference on the magnitude of pleasure, safety and assurance that green customers associate the green brand with, based on their past experiences. This paper views both green brand image and green trust as cumulative and experiential outcomes of green satisfaction. Thus, development of green brand image may be used as a proxy for determining brand positioning over time and customers’ trust with the green brand (Ha, Citation2021; Shakir et al., Citation2021; Voona et al., Citation2011). In contrast, negative brand image correlates with brand mistrust (Pivato et al., Citation2008). It is hence imperative to view green brand image as a determinant of green trust.

The challenge with most green brands has been overcoming green washing by marketers who promise green products and yet fail to fulfil their green promises (Polonsky, Citation1994; Qayyum et al., Citation2022). Given the premium prices of most green products, the notion further distances the conception of building green trust even for genuine green brands. Literature suggests organic foods are credence products to connote the high levels of consumer involvement when selecting amongst competing products (Janssen & Hamm, Citation2012; Rahman et al., Citation2016). Thus, credible information is needed prior to consumers purchasing them. Green brand image also leads to customer recommendations and they are a springboard for building green trust and reducing consumer perceived risk. Several studies have maintained that lack of trust impedes consumers’ preference for organic foods (Ha, Citation2021; Janssen & Hamm, Citation2012; Van Loo et al., Citation2013). Their findings have been confirmatory of the positive effect of green brand image on green trust. As a result, this paper also hypothesized that;

H4: Green brand image positively influences green trust for organic food brands.

2.2.5. Green brand image and green brand equity

The Consumer Based Brand Equity (CBBE) model identifies the role of brand imagery and brand judgements in building brand resonance (Keller, Citation1993). Furthermore, several studies suggest that green brand image is a key antecedent of green brand equity (Fong et al., Citation2014; Ha, Citation2021; Lin et al., Citation2017; Nysveen et al., Citation2018). The brand image of the green product is key in determining its green brand equity. Brand image develops over successive purchases and consumption experiences (Kotler et al., Citation2002). Green consumers develop a green image profile for a green brand over time (Akbar & Azhar, Citation2020; Ha, Citation2021; Shakir et al., Citation2021). This paper views green brand image as the consumers’ subjective perception of an organic food brand based on its pro-health initiatives and environmental fulfilment.

The relationship between brand image and brand equity has been reported in a number of contexts (Buil et al., Citation2013; Cretu & Brodie, Citation2007; Delafrooz & Goli, Citation2015; Faircloth et al., Citation2001; Fong et al., Citation2014; Namkung & Jang, Citation2013). Their findings supported the positive effect of green brand image on green brand equity. The findings have also been affirmed by Bekk et al. (Citation2016) and Butt et al. (Citation2016). Green brand equity can reduce green confusion amid green misconceptions and green washing. Thus, within an organic food context, green food brands need to possess a positive green image in the minds of consumers to develop green brand equity. This paper also hypothesized that;

H5: Green brand image positively influences green brand equity for organic food brands.

2.2.6. Green trust and green brand equity

Brand trust has been a widely cited determinant and deterrent of brand success (Chen & Chang, Citation2013; Ha, Citation2021). The ultimate goal of marketing is to develop an inseparable bond between the consumer and the brand, and the main ingredient of this bond is trust (Hiscock, Citation2001). The influence of trust in catalyzing business relationships has been emphasised in marketing literature (Dwyer et al., Citation1987; Hunt et al., Citation2006). Morgan and Hunt’s (Citation1994) theory of trust and commitment epitomizes the key role of trust between businesses, people and brands. Familiarity is a precondition of trust and this confirms the significance of experiential effects with a brand (Rossenbaum-Elliot et al., Citation2011, p. 33). Although past studies (Giannakas, Citation2002; Padel & Foster, Citation2005; Rahman et al., Citation2016) have shown that trust influences consumer behavior on food products, Reisch and Thogersen (Citation2015) contend that trust is still an understudied construct in sustainable consumption despite its effect on the actual uptake of green food brands.

Furthermore, the complexity of trust is that any elements of mistrust along the supply chain can transcend to affect consumers’ brand preference at the retail outlets (Voona et al., Citation2011). This suggests even stronger implications on food products. Green trust acts as a lever that promotes brand equity in organic brands within consumer food markets (Esch et al., Citation2006; Ha, Citation2021). Consumers need the conviction that organic products will always meet their expectations and satisfy their pro health objectives (Butt et al., Citation2016; Ha, Citation2021). Studies by Akturan (Citation2018), Butt et al. (Citation2016), Chang and Fong (Citation2010) and Ha (Citation2021) investigated the influence of green trust on green brand equity. Their findings confirmed the positive effect of green trust on green brand equity. These results support Janssen and Hamm (Citation2012), Pivato et al. (Citation2008), Van Loo et al. (Citation2013). Based on the empirical evidence, following hypothesis was also formulated;

H6: Green trust positively influences green brand equity for organic food brands.

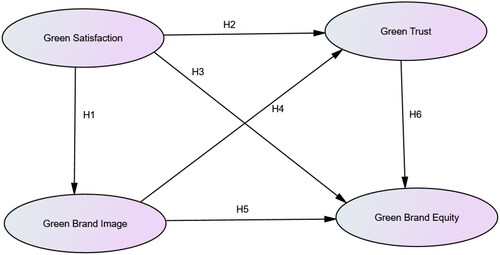

2.3. Conceptual framework

The study developed a research model that proposed the multifaceted effect of green satisfaction as (1) a direct antecedent of green brand equity, (2) an antecedent through green brand image and (3) an antecedent via the mediation of green trust. illustrates the hypothesized research model.

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Design, population and sampling

A cross sectional study was conducted to examine the proposed antecedents of green brand equity in organic food markets. Consistent with positivism, quantitative approaches through deductive methods were employed (Saunders et al., Citation2018). The study adopted a causal research design which enabled proposition and examination of the research hypotheses in a structural model. The study targeted green consumers in Harare’s premier markets who purchased organic food products in the last six months (June to November 2022). Using convenience sampling and person administered questionnaires, data was collected in Avondale, Belgravia, Borrowdale, Chisipite, Glen Lorne, Mt Pleasant and Westgate, where more health conscious consumers are found. Customers were selected for participation outside these food retail chains; Bon Marche, Food Express, Food Lovers, Food World, OK Zimbabwe, Spar and TM Pick n Pay.

3.2. Measures

The measurement scales were developed from past studies (Butt et al., Citation2016; Ha, Citation2021). Apart from the demographic questions and constructs’ items, filter questions were used to screen out consumers who did not reasonably indicate their familiarity and actual purchase of organic foods. The main constructs were measured on a seven (7) point likert scale from Strongly Disagree (SD = 1) to Strongly Agree (SA = 7) and these were operationalised as Green Satisfaction (GSA), Green Brand Image (GBI), Green Trust (GTR) and Green Brand Equity (GBE). A pilot test was conducted with fifteen (15) finalist students at a local university in Harare.

3.3. Data collection procedures and ethical compliance

The main objective of the study was shared with consumers prior to response solicitation. Participants were also informed that their participation was voluntary. In line with the Research Council of Zimbabwe’s ethical guidelines, the study ensured informed consent, information safety, privacy and confidentiality of participants. Participants were also informed not to disclose their names, addresses and other personally identifiable information.

3.4. Data analysis methods

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was used to assess unidimensionality, construct validity and reliability of the measurement model. To estimate parameters and examine research hypotheses, covariance based Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) was used. The model fit indices used in this study were the absolute and relative fit indices. The absolute fit indices were the Chi Square (CMIN/x2), Normed Chi Square (x2/df), Goodness of Fit (GFI), Standardised Root Mean Residual (SRMR) and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). The relative or incremental fit indices were the Incremental Fit Index (IFI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Tucker Lewis Index (TLI).

4. Results

4.1. Sample characterisation

The gender composition of the sample was even as evidenced by 51.1% female participants relative to 48.9% on their male counterparts (n = 319). The age distribution showed that 21.3% were between 16 and 20 years, 38.9% were in the 21–25 years, 18.8% were aged between 26 and 30 years, 15.4% were in the 30–35 years group whilst the 36–40 age group had the modest participants (5.6%). This suggests that the generations Y and Z are more health conscious and prefer organic foods as more consumer awareness and education has been heavily targeted on these groups (Muposhi et al., Citation2015). In terms of education, 19.7% had Master’s degrees and above, 46.7% had Bachelor’s degrees, 24.8% had completed their professional diplomas, whilst 8.8% had completed their ordinary level education. These results suggest that higher consumer literacy enhances health consciousness and green adoption (Cheng et al., Citation2011).

4.2. Assessment of the measurement model

Following the recommendations of Anderson and Gerbin (Citation1988), a two-step procedure was done to examine the findings. A Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) procedure was used to examine the measurement model and Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) was used to test research hypotheses (Hair et al., Citation2010). Confirmatory Factor Analysis involves examining a priori hypothesized factor structure against the sample variance-covariance factor matrix (Byrne, Citation2013; Kline, Citation2016).

On the initial estimation, the CFA model produced a mediocre model fit. The latent factors were allowed to covary and the model fit improved. After inspection of the Modification Indices (MI), error terms (e2-e5, e1-e2, e8-e11, e14-e15 and e14-e16) between items measuring the same construct were allowed to covary (Kline, Citation2016). Inspection of the standardised residual covariance matrix also resulted in deletion of item GBI5 because it had huge absolute values greater than 1, thus it was a misfit in the model (Byrne, Citation2013). The result was a good fitting model within recommended fit thresholds. illustrates the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) model fit before and after respecification.

Table 1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) model fit.

Using Maximum Likelihood estimation, all factor loadings obtained significant values and t-values were statistically significant (p < 0.001) (Hair et al., Citation2010). The lowest loading was 0.681 on item GSA5 whilst the highest loading was 0.901 on item GTR3, although Kline (Citation2016) recommends loading of 0.7 and above, GSA5 was retained since it did not affect the Average Variance Extracted (AVE). Hair et al. (Citation2010) argues that item loadings should be at least 0.5 in the measurement model. The squared multiple correlations were above 0.5 (Holmes-Smith, Citation2001), except for item GSA5 (0.462). However, Hair et al. (Citation2010) recommend deletion only for values below 0.25, thus GSA5 was retained for further analysis.

To examine convergent validity, Average Variance Explained (AVE) was used. According to Hair et al. (Citation2010), AVE is the mean of squared variances per factor which denotes the amount of variance that is shared between items measuring one construct. To confirm convergent validity, the scores of AVEs in a measurement model should be at least 0.5, denoting at least 50% shared variance between the variables (Anderson & Gerbin, Citation1988; Hair et al., Citation2010). The lowest AVE in the model was 0.655 (Green Satisfaction) whilst the highest was 0.768 (Green Trust). Thus, the requirement of convergent validity was satisfied.

Internal consistency was examined using both Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability. According to Kline (Citation2016), composite reliability should be used where Confirmatory Factor Analysis is employed. Composite reliability is calculated as total score variance minus error variance, thus it gives the true score variance (Byrne, Citation2013). The scores for composite reliability ranged from 0.703 (Green Brand Equity) to 0.904 (Green Satisfaction). Thus, using the threshold of 0.7 (Byrne, Citation2013; Hair et al., Citation2010), the requirements of construct reliability were met. The reliability scores using Cronbach’s alpha were also above 0.7 (Hair et al., Citation2010; Nunnally & Bernstein, Citation1994), ranging from 0.874 to 0.929. shows the psychometric properties of the measurement model.

Table 2. Psychometric properties of the measurement model.

Discriminant validity was defined as the extent to which measures of different constructs are dissimilar (Zikmund et al., Citation2013). This paper examined discriminant validity using the criteria by Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981). They postulated that to establish distinct constructs, the square root of the AVE of the construct should be greater than any of its correlations with other variables in the model. All correlations were below the square roots of their AVE values. The Maximum Shared Variance (MSV) values were also less than the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values (), to confirm that discriminant validity was present (Hair et al., Citation2010). illustrates the assessment of discriminant validity.

Table 3. Assessment of discriminant validity.

4.3. Assessment of the structural model

In order to examine the hypothesized theoretical model, Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) was used. The three criteria were used to evaluate the structural model. The model fit examined how much the hypothesized model reproduces sample data, the model fit (Anderson & Gerbin, Citation1988; Hu & Bentler, Citation1999). Secondly, the path estimates were used to assess the causal effect between variables in the structural model (Hair et al., Citation2010; Kline, Citation2016). Third, the explanatory power of the model was evaluated (the variability in the endogenous variables explained by the model) (Al-Fraihat et al., Citation2020; Hair et al., Citation2010). Lastly, the nomological validity of the model was also examined in order to assess the relevance of the structural relationships to established theory (Hagger et al., Citation2017).

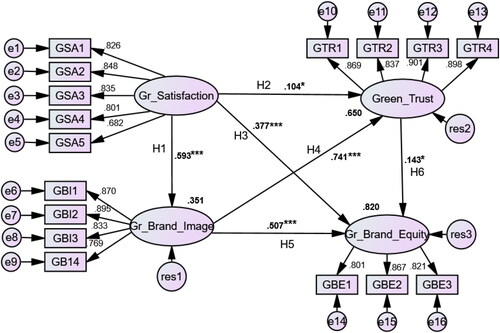

Following the recommendations of Anderson and Gerbin (Citation1988), Byrne (Citation2013) and Kline (Citation2016), the model fit of the structural model was assessed. Although the Chi Square was significant, the use of the normed Chi Square (Chi Square normalised by degrees of freedom or x2/df) is normally used. The normed Chi square was 2.372, a reflection of a good fitting model (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999). In other absolute fit indices, the GFI was 0.918, whilst the RMR= 0.049, and RMSEA = 0.067. In incremental fit indices the IFI= 0.970, TLI= 0.954 and CFI= 0.962. As a result, the model reflected a good fit (Byrne, Citation2013; Hu & Bentler, Citation1999; Kline, Citation2016). illustrates the structural model.

Figure 2. The structural model.

Notes: *** denotes p < 0.001; *denotes p < 0.05; Gr = Green.

Source: AMOS Graphics (survey data).

Secondly, the parameter estimates between the latent constructs in the model were assessed (Hair et al., Citation2010). In order to examine causal effects between variables in the model and test research hypotheses, coefficients estimated using the Maximum Likelihood method were used. Hypothesis H1 had proposed a positive relationship between green satisfaction and green brand image. The resulting estimate (β) was 0.593, with a t-statistic of +9.962, and p < 0.001. This confirmed the positive effect of green satisfaction on green brand image. Green satisfaction also positively influenced green trust (β = 0.104, t = +1.996 and p = 0.042), confirming the role of green satisfaction in building green trust with organic foods. Green satisfaction also had a positive and significant direct effect on green brand equity directly (β = 0.377, t = +7.550, p < 0.001). Results confirm the key role of green satisfaction in the development of green brand equity in organic food markets, directly and indirectly through green brand image and green trust. Resultantly, hypotheses H1, H2 and H3 were supported.

The paper had also proposed that green brand image positively influenced green trust with organic food brands. The results reflected an estimate of 0.741, supported by a t-statistic of +12.356 and p < 0.001. This relationship was confirmed and hypothesis H4 received empirical support. More so, the study proposed that green brand image positively affects green brand equity in H5. This hypothesis was supported as the path estimate was 0.507, supported by a t-statistic of +6.854, p < 0.001. Finally, hypothesis H6 had proposed that green trust positively influences green brand equity. The path estimate between green trust and green brand equity was 0.143, its t-statistic was +2.136 and p = 0.033. The results confirmed empirical support for the relationship between green trust and green brand equity, thus H6 was also accepted. shows the results of hypothesis testing.

Table 4. Outcomes of hypothesis testing.

The structural model was also assessed based on it explanatory power (Al-Fraihat et al., Citation2020). Green satisfaction explained 35.1% variability in green brand image (R Square = 0.351). An R Square (R2) of 0.65 confirmed that green satisfaction and green brand image explained 65% of the variability in green trust. The structural model also reflected that through effects of green satisfaction, green brand image and green trust, 82% of the variability in green brand equity (R Square of 0.820) was accounted for. The model reproduced structural relationships grounded in established theory, thus its nomological validity was confirmed (Hagger et al., Citation2017).

4.4. Discussion of findings

The study hypothesized the effect of green satisfaction on green brand image (H1). Interestingly, the study found that cumulative satisfaction with organic foods enhances development of positive green mental images, experiential knowledge about the green brand. As a result, H1 gained empirical support and the influence of green satisfaction on green brand image was confirmed. From the structural model, 35.1% of the variability in green brand image was explained by green satisfaction. Green satisfaction forms the basis on which customers create memorable mental images which help in the development of green brand image (Butt et al., Citation2016; Chen & Chang, Citation2013). These findings support the claims by Upamannyu and Bhakar (Citation2014) who also revealed that customer satisfaction influences brand image, albeit, in generic markets outside green contexts. These findings present important findings especially in the context of green food brands.

The study also examined the influence of green satisfaction on green trust. This relationship was confirmed and H2 received empirical support. The results suggest that given marked skepticism and consumer hesitancy to try green foods, green satisfaction provides an opportunity for organic food brands to build green trust. Green consumers are inclined to develop trust for brands that fulfill their green promises. Furthermore, green satisfaction helps to cultivate green trust, which however builds over successive encounters with a green brand, thus it also confirms the positive role of green brand image in enhancing green trust (Akturan, Citation2018; Morgan & Hunt, Citation1994; Thibaut, Citation2017) and green buying behavior (Shakir et al., Citation2021; Zia et al., Citation2021). Amid green washing and green confusion in most green markets, green satisfaction provides a springboard for developing green trust. The findings concur with several studies trust (Bekk et al., Citation2016; Butt et al., Citation2016; Esch et al., Citation2006).

More so, the study had hypothesized the direct effect of green satisfaction on green brand equity within organic food markets (H3). This relationship was supported and H3 was accepted. The findings suggest that green fulfillment through green satisfaction provides important leverage for developing brand equity, preference and likeness. Green brands are evaluated on their ability to satisfy their pro-health and environmental promises to consumers, thus confirming this through green satisfaction provides the rationale for development of brand value through green brand equity. These results also add a new layer to existing literature from an organic food context. They concur with previous studies (Bekk et al., Citation2016; Esch et al., Citation2006; Ha, Citation2021; Pappu & Quester, Citation2006).

In H4, the study proposed the effect of green brand image on green trust. This hypothesis was supported and the findings also suggest that green positive mental images created over successive interactions with a green brand help in cultivating green trust. Emotional associations with brands grow out of experiences and they are linked in memory to those brands, when a memory is recalled, the component parts of the memory, emotional associations are reunited (Rossenbaum-Elliot et al., Citation2011). Green trust has been observed to reduce perceived risk in purchasing green brands. The importance of building green brand trust has been observed in a number of studies (Ha, Citation2021; Janssen & Hamm, Citation2012; Rahman et al., Citation2016; Van Loo et al., Citation2013; Voona et al., Citation2011). Current findings support that green brand image will build feelings of trust over successive encounters with a green brand. Green brand image and green satisfaction explained 65% of the variability in green trust (R square = 0.65).

The study also hypothesized that green brand image influences green brand equity in H5. This relationship was observed and H5 was confirmed. This paper views green brand image as a proxy of green brand positioning within organic food markets. Organic food brands that carry positive brand image positioned themselves in green markets as reliable in fulfilling their green promises. Consumers value the net benefits on the biophysical environment that a green brand delivers (Zia et al., Citation2021) and this positively influence green buying behavior (Shakir et al., Citation2021). Thus, the findings support that green brand image positively improves green brand equity for organic food brands. These results concur with a plethora of studies in literature (Buil et al., Citation2013; Cretu & Brodie, Citation2007; Delafrooz & Goli, Citation2015; Faircloth et al., Citation2001; Fong et al., Citation2014; Namkung & Jang, Citation2013).

The last hypothesis (H6) proposed the positive effect of green trust on green brand equity. Interestingly, this hypothesis was also supported. The findings emphasise the key role of green trust on building green brand value, especially of food brands. Trust acts as a key lever in most food markets and it serves as a reliability metric for food brands. Trusted brands earn brand value, consumers tend to share their green brand experiences with other consumers, and this implies that green trust reduces perceived risk, attracts new purchases, generates green word of mouth and reinforces green brand equity. The current findings lean on several studies in extant literature (Esch et al., Citation2006; Ha, Citation2021; Janssen & Hamm, Citation2012; Pivato et al., Citation2008; Van Loo et al., Citation2013). These results suggest that the ability of the green brand to deliver its green promises (pro health and pro environmental promises) is critically important for leveraging green brand equity, hence green buying behavior (Shakir et al., Citation2021). The validated model explained 82% of the variability (R Square = 0.82) in green brand equity, confirming the multifaceted role of green satisfaction in organic foods, directly and indirectly through green brand image and green trust.

5. Conclusions, implications and recommendations

5.1. Conclusions

The study sought to evaluate the antecedents of green brand equity in the organic food markets in Harare, Zimbabwe. The paper examined the key role of green satisfaction in influencing green brand image, green trust and green brand equity. The key revelation of the study was green satisfaction underpins the development of green brand equity directly and indirectly through its positive influence on green brand image and green trust. Green satisfaction also strengthens the effect of green brand image on green trust in organic food markets. The study also confirms the importance of brand image and brand trust especially in food markets where consumer sensitivity, hesitancy and skepticism to green brands is very high. The paper learns rising consumer awareness in line with sustainable consumption especially within the generations Y and Z, who represent a substantial consumer segment as well as important reflections of long-term consumption behaviors. The study brings a key emphasis on using green satisfaction to leverage green brand equity for organic food brands.

5.2. Theoretical implications

The study brings important implications for theory. Firstly, the study was not based an intuitive research framework based on a stand-alone theoretical model. An integrated model was proposed in this research grounded in the disconfirmation theory (Oliver, Citation1980), trust-commitment theory of relationship marketing (Morgan & Hunt, Citation1994) and the consumer based brand equity model (Keller, Citation1993). In addition, the social exchange theory (Thibaut, Citation2017) and the transactional cost theory (Williamson, Citation1986) also lent imperative insights in predicting causal relationships in the proposed model. As shown in , the validated structural model explained 82% of the variability in green brand equity in organic food markets (R square = 0.82). The study becomes the first to explore a key multifaceted role of green satisfaction in developing brand equity for green brands in the organic food context. Most studies have operationalized green satisfaction as the outcome variable. However, this study confirmed the key antecedent role of green satisfaction in the development of green brand image, green trust and subsequent green brand equity. It can therefore be drawn that in organic food markets, green satisfaction precedes the development of green trust and green brand equity, a novel theoretical contribution that has been overlooked in prior research.

Amid consumer hesitancy on green products, especially food products, the research reveals the importance of green satisfaction, green brand image and green trust on building green brand equity. Although these have been examined in prior research, the study also reiterates the key roles of green trust and green brand image in organic food context. Thus, the study validates a model that can be used to examine green brand equity in other markets outside Zimbabwe. This research can be a key theoretical springboard for the development of alternative decomposed frameworks that attempt to evaluate the antecedents of green brand equity in diverse consumer markets, as a pathway to catalyse the uptake of green products, especially food products.

5.3. Practical implications

With biophysical environmental concerns proliferating, this research brings important implications for both green producers and marketers, particularly in the food markets. Given the protracted consumer hesitancy with green foods in most consumer markets, especially in developing economies, green trust and green brand image emerge as strong catalysts to expedite the development of green brand equity in green food markets. The paper demonstrates how green marketers can utilise green satisfaction to eliminate consumer skepticism, mistrust and green phobias on green brands. Based on the findings of this research, green satisfaction presents an opportunity to fulfil both core product or functional performance and its embedded pro-health and environmental preservation promises. Green food marketers can use green satisfaction to build green brand image, green trust and ultimately green brand equity, hence green buying behavior in consumer markets.

Further, the study connotes key issues for green regulation especially quality control in green food production and marketing. This can help in mitigating green washing, enhancing environmental preservation and protecting consumer health. When organic food produces and marketers commit to developing, communicating and fulfilling their green value propositions through green satisfaction, the future green consumption prospects are enhanced and this can present a milestone success in the quest for biophysical sustainability.

5.4. Recommendations

This study recommends the development of green food brands that have a unique value proposition in terms of their functional (primary or core product) satisfaction and fulfilment of its pro-health and environmental preservation initiatives. The paper urges green marketers to avoid temptations of green washing by simply delivering the right green brand, the first time. This may bridge the gap between green promises and green fulfilment, a key impetus for brand positioning and strengthening green brand equity. Green washing, the tendency to overpromise on green benefits yet not delivering any, has been strongly cited as one of the reasons why green adoption has been slower than anticipated in most consumer markets.

5.5. Limitations and future study

Although the objective of the study was accomplished, the study was subject to a few limitations, which create avenues for future research. Although the effect of green satisfaction on green brand image was strongly confirmed, this relationship is yet to gain extensive empirical support within consumer markets. Future studies may consider cross validating this model in diverse geographical and market contexts.

Secondly, the study was conducted in the upmarket urban food markets in Harare, Zimbabwe. Consumer behavior may vary due to contextual factors. Future studies may investigate the determinants of green brand equity in rural markets and smaller towns alike. More so, the study was a cross sectional survey and consumers may change their beliefs, knowledge and behaviors on green food brands. Future studies may conduct longitudinal studies to evaluate the findings over a protracted period of research.

The paper also presents a limitation on the mono quantitative methods to examine the antecedents of green brand equity. Future studies may explore qualitative methods that garner deeper insights about motivations underlying consumer green purchase behaviors and brand value perceptions.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank all participants who took part in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data used in this research is available at: https://doi.org/10.17632/hmwsrp22yk.1

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Phillip Dangaiso

Phillip Dangaiso is a lecturer at Chinhoyi University of Technology, Zimbabwe. His research interests are in Green Marketing, Social Marketing, Services Marketing, Higher Educational Technology and Brand Management. This research was motivated by the topical green marketing imperatives meant to expedite environmental preservation and enhance long-term consumer health.

References

- Aaker, D. A. (1991). Managing brand equity. Free Press.

- Akbar, U. S., & Azhar, S. M. (2020). The drivers of brand equity: Brand image, brand satisfaction and brand trust. The South Asian International Conference (SAICON), December. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/324518044%0AThe.

- Akturan, U. (2018). How does greenwashing affect green branding equity and purchase intention ? An empirical research. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 36(7), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1108/MIP-12-2017-0339

- Al-Fraihat, D., Joy, M., Masa’deh, R., & Sinclair, J. (2020). Evaluating E-learning systems success: An empirical study. Computers in Human Behavior, 102, 67–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.08.004

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbin, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modelling in practise: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

- Bekk, M., Spörrle, M., Hedjasie, R., & Kerschreiter, R. (2016). Greening the competitve advantage: Antecedents and consequences of green brand equity. Quality & Quantity, 50(4), 1727–1746. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-015-0232-y

- Biel, A. L. (1992). How brand image drives brand equity. Journal of Advertising Research, 36(2), 6–12.

- Buil, I., Martínez, E., & de Chernatony, L. (2013). The influence of brand equity on consumer responses. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 30(1), 62–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.07.030

- Butt, M. M., Mushtaq, S., Afzal, A., Khong, K. W., Ong, F. S., & Ng, P. F. (2016). Integrating behavioral and branding perspectives to maximize green brand equity: A holistic approach. Business Strategy and the Environment, 26(4), 507–520. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.1933

- Byrne, B. M. (2013). Structural equation modelling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications and programming. Routledge Taylor and Francis.

- Chang, N. J., & Fong, C. M. (2010). Green product quality, green corporate image, green customer satisfaction, and green customer loyalty. African Journal of Business Management, 4(13), 2836–2844. http://www.academicjournals.org/AJBM

- Chen, Y. S., & Chang, C. H. (2013). Greenwash and green trust: The mediation effects of green consumer confusion and green perceived risk. Journal of Business Ethics, 114(3), 489–500. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1360-0

- Cheng, H., Kotler, P., & Lee, N. (2011). Social Marketing in public health: Global trends and success stories. Jones & Bartlett.

- Cretu, A. E., & Brodie, R. J. (2007). The influence of brand image and company reputation where manufacturers market to small firms a customer value perspective. Industrial Marketing Management, 36(2), 230–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2005.08.013

- De Boeck, E., Mortier, A. V., Jacxsens, L., Dequidt, L., & Vlerick, P. (2017). Towards an extended food safety culture model: Studying the moderating role of burnout and job stress, the mediating role of food safety knowledge and motivation in the relation between food safety climate and food safety behavior. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 62(April), 202–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2017.01.004

- Delafrooz, N., & Goli, A. (2015). The factors affecting the green brand equity of electronic products : Green marketing. Cogent Business & Management, 2(1), 351. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2015.1079351

- Delgrado-Ballester, E., & Munuera-Alemán, J. (2005). Does brand trust matter to brand equity? Journal of Product & Brand Management, 14(3), 187–196. https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000006475

- Dwyer, F. R., Schurr, P. H., & Oh, S. (1987). Developing buyer-seller relationship. Journal of Marketing, 51(2), 11–27. https://doi.org/10.2307/1251126

- Esch, F., Langner, T., Schmitt, B., & Geus, P. (2006). Are brands forever? How brand knowledge and relationships affect current and future purchases. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 15(2), 98–105. https://doi.org/10.1108/10610420610658938

- Faircloth, J. B., Capella, L. M., & Alford, B. L. (2001). The effect of brand attitude and brand image on brand equity. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 9(3), 61–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/10696679.2001.11501897

- Fong, P., Butt, M. M., Khong, K. W., Ong, F. S., Journal, S., May, N., Fong, P., Muhammad, N., & Butt, M. (2014). Antecedents of green brand equity: An integrated approach antecedents of green brand equity . Journal of Business Ethics, 121(2), 203–215. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1689-z

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. (1981). Evaluating Structural Equation Models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3150980

- Giannakas, K. (2002). Information asymmetries and consumption decisions in organic food product markets. Canadian Journal of Agricultural Economics/Revue Canadienne D’agroeconomie, 50(1), 35–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-7976.2002.tb00380.x

- Gronroos, C. (2002). Service management and marketing. John Wiley & Sons.

- Ha, M. (2021). Optimizing green brand equity : The integrated branding and behavioral perspectives. SAGE Open, 11(3), 215824402110360. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211036087

- Hagger, M. S., Gucciardi, D. F., & Chatzisarantis, N. L. D. (2017). On nomological validity and Auxilliary Assumptions: The importance of simultaneously testing effects in social cognitive theories applied to health behavior and some guidelines. Personality and Social Psychology, 8, 933. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01933

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Prentice Hall Upper Saddle River.

- Hiscock, J. (2001). Most trusted brands. Marketing, 32–33. www.campaignlive.co.uk.

- Holmes-Smith, P. (2001). Introduction to structural equation modelling using LISREL. ACSPRI-Winter Training Program.

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Hunt, S., Arnett, D., & Madhavaram, S. (2006). The explanory foundations of Relationship Marketing Theory. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 21(2), 72–87. https://doi.org/10.1108/10610420610651296

- Janssen, M., & Hamm, U. (2012). Product labelling in the market for organic food: Consumer preferences and willingness-to-pay for different organic certification logos. Food Quality and Preference, 25(1), 9–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2011.12.004

- Keller, K. L. (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. Journal of Marketing, 57(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.2307/1252054

- Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modelling (3rd ed.). Guilford Publication.

- Kotler, P., Armstrong, G., & Cunningham, P. G. (2002). Principles of marketing. Prentice Hall.

- Lin, J., Lobo, A., & Leckie, C. (2017). Green brand benefits and their influence on brand loyalty. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 35(3), 425–440. https://doi.org/10.1108/MIP-09-2016-0174

- Matharu, G. K., von der Heidt, T., Sorwar, G., & Sivapalan, A. (2022). What motivates young indian consumers to buy organic food? Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 34(5), 497–516. https://doi.org/10.1080/08961530.2021.2000919

- Misra, S., & Panda, R. K. (2017). Environmental consciousness and brand equity An impact assessment using analytical. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 35(1), 40–61. https://doi.org/10.1108/MIP-09-2015-0174

- Morgan, R., & Hunt, S. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 58(3), 20–38. https://doi.org/10.2307/1252308

- Muposhi, A., Dhurup, M., & Surujlal, J. (2015). The green dilemma: Reflections of a Generation Y consumer cohort on green purchase behaviour. The Journal for Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa, 11(4), 31–40. https://doi.org/10.4102/td.v11i3.64

- Namkung, Y., & Jang, S. C. (2013). Effects of restaurant green practices on brand equity formation: Do green practices really matter? International Journal of Hospitality Management, 33, 85–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2012.06.006

- Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory. McGraw-Hill.

- Nyathi, P. (2008). Zimbabwe’s Cultural Heritage. Amabooks Project MUSE. muse.jhu.edu/book/17135

- Nysveen, H., Oklevik, O., & Pedersen, P. E. (2018). Brand satisfaction: Exploring the role of innovativeness, green image and experience in the hotel sector. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30(9), 2908–2924. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-05-2017-0280

- Oliver, R. L. (1980). A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. Journal of Marketing Research, 17(4), 460–469. https://doi.org/10.2307/3150499

- Oliver, R. L. (1997). Satisfaction: A behavioral perspective on the consumer. The McGraw-Hill Companies.

- Padel, S., & Foster, C. (2005). Exploring the gap between attitudes and behaviour: Understanding why consumers buy or do not buy organic food. British Food Journal, 107(8), 606–625. https://doi.org/10.1108/00070700510611002

- Papista, E., & Dimitriadis, S. (2019). Consumer – green brand relationships: Revisiting bene fi ts, relationship quality and outcomes. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 28(2), 166–187. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-09-2016-1316

- Pappu, R., & Quester, P. (2006). Does customer satisfaction lead to improved brand equity? An empirical examination of two categories of retail brands. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 15(1), 4–14. https://doi.org/10.1108/10610420610650837

- Pivato, S., Misani, N., & Tencati, A. (2008). The impact of corporate social responsibility on consumer trust: The case of organic food. Business Ethics, 17(1), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8608.2008.00515.x

- Polonsky, M. (1994). An introduction to green marketing. Electronic Green Journal, 1(2), 177. https://doi.org/10.5070/G31210177

- Qayyum, A., Jamil, R. A., & Sehar, A. (2022). Impact of green marketing, greenwashing and green confusion on green brand equity marketing. Spanish Journal of Marketing, 27(3), 286–305. https://doi.org/10.1108/SJME-03-2022-0032

- Rahman, K. M., Azila, N., & Noor, M. (2016). In search of a model explaining organic food purchase behavior The overlooked story of Montano and Kasprzyk’s integrated behavior model. British Food Journal, 118(12), 2911–2930. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-02-2016-0060

- Reisch, L. A., & Thogersen, J. (2015). Handbook of research on sustainable consumption. Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

- Rossenbaum-Elliot, R., Percy, L., & Pervan, S. (2011). Strategic brand management (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Saunders, M. N. K., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2018). Research methods for business students (8th ed.). Pearson.

- Shakir, A. C., Mushtaq, N., Saeed, A., & Sarwar, G. (2021). Impact of green advertisement, green brand awareness, on green brand image on green satisfaction: The mediating role of green buying behavior. International Journal of Management, 12(1), 1757–1779. https://doi.org/10.34218/IJM.12.1.2021.154

- Thibaut, J. W. (2017). The social psychology of groups. Routledge.

- Upamannyu, N. K., & Bhakar, S. S. (2014). Effect of customer satisfaction on brand image & loyalty intention: A study of cosmetic product. International Journal of Research in Business and Technology, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.17722/ijrbt.v4i1.179

- Van Loo, E. J., Diem, M. N. H., Pieniak, Z., & Verbeke, W. (2013). Consumer attitudes, knowledge, and consumption of organic Yogurt. Journal of Dairy Science, 96(4), 2118–2129. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2012-6262

- Voona, J., Nguib, K., & Agrawalc, A. (2011). Determinants of willingness to purchase organic food: An exploratory study using structural equation modeling. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, 14(2), 103–120. https://www.academia.edu

- Wee, C. S., Ismail, K., & Ishak, N. (2014). Consumers perception, purchase intention and actual purchase behavior of organic food products. Review of Integrative Business & Economics, 3(2), 378–397. www.sibresearch.org

- Williamson, S. D. (1986). Costly Monitoring, Financial Intermediation, and Equilibrium Credit Rationing. Journal of Monetary Economics, 18(2), 159–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3932(86)90074-7

- Wu, H.-C., Ai, C.-H., & Cheng, C.-C. (2016). Synthesizing the effects of green experiential quality, green equity, green image and green experiential satisfaction on green switching intention. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 28(9), 2080–2107. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-03-2015-0163

- Yasin, N. M., Noor, M. N., & Mohamad, O. (2007). Does image of country-of-origin matter to brand equity. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 16(1), 38–48. https://doi.org/10.1108/10610420710731142

- Zia, S., Paracha, S. Z., Nadeem, S. H., & Mushtaw, N. (2021). Are Pakistani consumers ready to go green: A study of buying intentions of Pakistani consumers. Bulletin of Business and Economics, 10(4), 126–138. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6338683

- Zikmund, W. G., Babin, B. J., Carr, J. C., & Griffin, M. (2013). Business research methods (8th ed.). South-Western/Cengage Learning.