Abstract

The research conducted to study the impact of customers’ perceptions of corporate social marketing (CSM) on the multidimensions of brand equity in the case of dairy products in Vietnam. Research data was collected, through direct interviews, from 780 valid questionnaires responsed by customers living in Ho Chi Minh City and Ha Noi. The study found that CSM is an important factor in brand equity creation, and more effective than distribution intensity and advertising in building a dairy product brand. The results confirm that CSM initiatives positively effect on the five CBBE dimensions (brand awareness, brand associations, perceived quality, brand trust, and brand loyalty) and show causal order among the CBBE dimensions. Futhermore, the research findings enrich the theory of CSM and brand equity and support the Theory of Planned Behavior.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

Research background

Business organizations are operating in a quickly changing and unpredidictable environment. The change of business environment impacts their decisions and actions directly or indirectly. From a marketing perspective, changing customer attitudes and perceptions is a top concern. How to respond appropriately to change to achieve the desired results is a major challenge. Today, customers are more and more informed about health problem driven from food production, social issues, and environmental problems in the media. This requires business organizations engaged with social responsibility and toward social marketing to provide support for solving problems that customers are preoccupied with. Therefore, marketing should contribute to the formation of sustainable social behavior, and support sustainable economic development, or proactively implement corporate social marketing (CSM) as a sustainable marketing form (Emery, Citation2012; Gordon et al., Citation2011; Martin & Schouten, Citation2012). CSM refers to implementing firms’ responsibility for social issues such as economic, ethical, philanthropic responsibilities (Kotler, Citation2009, Citation2011).

CSM influences the perceptions and behaviors of target audiences (e.g. community, supplier, consumer) to form sustainable social behaviors; thereby it benefits both society and firms (Emery, Citation2012; Gordon et al., Citation2011; Lefebvre, Citation2012). Many empirical studies showed that consumer perception of environmental issues significantly affect their buying intention (Dilotsotlhe, Citation2021; Ellen et al., Citation1991; Kim & Choi, Citation2005; Li & Jaharuddin, Citation2021; Wheale & Hinton, Citation2007; Young et al., Citation2010). Consumers tend to buy products/services offered by reputable and socially responsible companies (Vo & Le, Citation2016). Numerous studies of corporate responsibility initiatives for social issues (education, public health, social security and welfare, etc.) found three positive outcomes of consumer perception toward corporate social responsibility: the increase of buying intention (Brown & Dacin, Citation1997; Lee et al., Citation2011; Sen & Bhattacharya, Citation2001; Thanh et al., Citation2021), customer loyalty (Barone et al., Citation2000; Bhattacharya & Sen, Citation2003; Lichtenstein et al., Citation2004), and consumer satisfaction (Luo & Bhattacharya, Citation2006). The relationship between CSM and brand equity represents an area that requires further investigation within the field of marketing. The purpose of CSM is to serve the interests of the public and their real needs, as well as to increase the common wellbeing of society (Hoeffler & Keller, Citation2002). One crucial research gap lies in understanding the mechanisms through which CSM activities influence brand equity. While it is widely acknowledged that corporate social responsibility initiatives can positively affect brand equity, there is a need for more empirical research to uncover the underlying processes and mechanisms involved. Specifically, exploring how different dimensions of CSM impact various aspects of brand equity (e.g. brand awareness, brand loyalty, perceived quality) can provide valuable insights for marketers and help them design effective CSM strategies that enhance brand equity. The second research gap is examining the impact of CSM on brand equity for businesses operating in specific industries or regions. Investigating the unique dynamics and challenges faced by these entities in implementing CSM initiatives and their subsequent impact on brand equity can provide valuable insights for a wider range of businesses. Moreover, there have been no empirical studies to assess the effectiveness of CSM initiatives based on consumer perspectives (Deshpande, Citation2016; Hoeffler et al., Citation2006; Inoue & Kent, Citation2014), and its association with brand equity. The research and experimental study of customer-based brand equity (CBBE) is an important issue for both scholars and marketers (Aaker, Citation1991, Citation1996; Kapferer, Citation2008; Kartono & Rao, Citation2009a; Keller, Citation2008; Keller & Lehmann, Citation2006). However, they continue to face challenges in broaden the perspective and empirical approach to CBBE, across different industries and in different countries (Bick, Citation2009; Christodoulides & De Chernatony, Citation2010; Hsieh, Citation2004; Koçak et al., Citation2007; Oliveira et al., Citation2015; Washburn & Plank, Citation2002). Therefore, studying how CSM impact on various aspects of CBBE in a specific industry in a country is essential.

The dairy industry has made important contributions to the economy, sustainable economic development, and human nutrition and health (FAO). Vietnamese dairy industry has grown rapidly with the average growth rate reached 12.6% per year, considered one of the industries with high and stable growth in the FMCG industry. The dairy industry has been contributed to the growth rate of livestock sector around 10% per year; therefore, considered as a potential dairy consumption market (VIRAC, Citation2019, VIRAC, Citation2020); and Vinamilk, Nutifood, IDP and Moc Chau Milk have been in the top 25 Vietnamese brand list in F&B industry, according to Vietnam (Citation2022). The situation motivated us to conduct this study to measure the impact of CSM from the perception of consumers on CBBE components in Vietnamese dairy industry. The focusses of this study are on the effect of CSM on consumer perceptions towards dairy’ brands, and the relationships between CBBE dimensions. The following sections will be literature review, research hypothesis development and research model, data collection and processing, findings’ discussion, recommemdation, and limitations.

Literature review

Theoretical background

To achieve the research objective mentioned above, the research model was developed from the two basic models - Theory Reasoned Action (TRA), and Theory Planned Behavior (TPB). The TRA Model (Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation1975) argues that attitude towards behavior and subjective norms are two basic groups of factors that form individual behavioral intention and actual behavior. Subjective norms elements belong to individual perception and influenced by society; attitude towards the behavior as elements belonging to the impact from the object (Bray, Citation2008). The TPB model (Ajzen (Citation1985, Citation1991, Citation2019) argues that behavioral intention is explained by three groups of factors: attitude towards behavior, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control and actual behavior, but is regulated to a certain extent by variables of perceived behavioral control (Ajzen, Citation1991, Citation2019). To improve behavioral predictability in specific contexts, the TPB model is continuously adjusted by Ajzen (Citation2011, Citation2019), namely, cognitive variables that control behavior not only directly impacting intentions but also regulating attitudes and subjective norms.

Corporate social marketing (CSM)

The social marketing concept was first introduced by Kotler and Zaltman (Citation1971) as the design, implementation, and control of marketing programs with the main goal to achieve the success of an organization by balancing the short-term needs of individuals and the long-term benefits of society (Kotler, Citation1972). CSM is an extension of social marketing to a corporate context (Hoeffler et al., Citation2006; Kotler et al., Citation2012) to take on more social responsibility (Kotler, Citation2011). CSM applies marketing principles to better shape marketplace be more efficient and sustainable and increase people’s well-being and social welfare (Phils et al., Citation2008); and the fact that CSM has been constantly adjusted to the innovation of society (Lefebvre, Citation2012). CSM can be approached as a firm actively or voluntarily uses its business resources and/or its partners to develop, sponsor, conduct campaigns/programs to care for and improve education, public health, community well-being and/or social welfare; environmental protection; thereby it makes a change in perceptions and behaviors voluntarily of the target audience (local communities, partners, customers), and creates practical benefits for both society and company. Applying CSM has been an inevitable trend due to it connecting the social marketing purpose of a firm with the desired development of a society (Kotler et al., Citation2012). CSM aims to transform perception and voluntary behavior of target audiences, thereby it forms sustainable social behaviors to bring benefit to both society and business (Emery, Citation2012; Gordon et al., Citation2011; Lefebvre, Citation2011, Citation2012). Though, few empirical studies on CSM have focused on the perspective of consumers (Deshpande, Citation2016; Hoeffler et al., Citation2006; Inoue & Kent, Citation2014; Truong & Hall, Citation2016).

Customer–based brand equity (CBBE)

A brand can be thought of as a group of unique functional and emotional values and can provide customers with a favorable experience (De Chernatony et al., Citation2006). Branding promotes an increase in the customer’s perceived value of the product (Mizik & Jacobson, Citation2009). Brand as a competitive advantage, which is difficult for competitors to imitate or replace (Baldauf et al., Citation2003; Slotegraaf & Pauwels, Citation2006).

Brand equity (BE) is one of the popular and importanct concepts in marketing (Christodoulides & De Chernatony, Citation2010; Davcik et al., Citation2015; Keller, Citation1993, Citation2008), reflecting the added value a brand creates for its products, derived from brand marketing efforts to reach potential and/or target customers (Aaker, Citation1991, Citation1996; Anderson, Citation2007; Bick, Citation2009; Keller & Lehmann, Citation2006; Netemeyer et al., Citation2004). BE can be measured from three different aspects (Baalbaki & Guzmán, Citation2017; Keller & Lehmann, Citation2003, Citation2006): Consumer-level measures (e.g. Aaker & Joachimsthaler, Citation2000; Baker et al., Citation2005; Bendixen et al., Citation2004; Chen, Citation2001; Keller, Citation1993; Lassar et al., Citation1995; Shocker & Weitz, Citation1988; Tong & Hawley, Citation2009a, Citation2009b,…), Market-level measures (e.g. Cobb-Walgren et al., Citation1995; Doyle, Citation2001; Dyson et al., Citation1996; Farquhar et al., Citation1991; Kapferer, Citation1997; Kim et al., Citation2003), and Financial-level measures (e.g. Aaker & Jacobson, Citation1994; Barth et al., Citation1998; Simon & Sullivan, Citation1993). In addition, many authors have developed commercial asset measurement models that incorporate all these measurement systems (e.g. Epstein & Westbrook, Citation2001; Keller & Lehmann, Citation2006).

CBBE has been discussed by researchers; however, there is no consensus on its definition, or management (Keller, Citation1993, Citation2008; Oliveira et al., Citation2015; Vázquez et al., Citation2002) due to its two measurement approaches - financial and marketing (Christodoulides & De Chernatony, Citation2010; Hsieh, Citation2004). Some researchers assume that CBBE expresses selectively wills and emotions of consumers for the brand in a set of competing brands available in marketplace (Kartono & Rao, Citation2009b; Keller & Lehmann, Citation2006). Others believe that CBBE results from marketing efforts of a company to build positive awareness, attitude, behavior of consumers towards a brand (Bick, Citation2009; Hsieh, Citation2004; Keller, Citation2008) and create brand value based on increasing consumers’ buying intention for the brand (Keller, Citation2008).

Research hypothesis development and research model

The research hypotheses and research model were developed based on the TPB model adjusted by Ajzen (Citation2011, Citation2019), and the selected empirical studies on CBBE such as Buil et al. (Citation2013b) evaluated the effect of promotion and advertising on CBBE dimensions in the UK beverage, apparel, home appliances and car industries; Saydan (Citation2013) assesses the impact of goods origin on CBBE components in the household electrical goods industry in the UK market; Su and Tong (Citation2015) evaluated the impact of brand personality on CBBE components in the sportswear industry in the US market; Jafari Drabjerdi et al. (Citation2016) evaluated the impact of advertising costs, attitudes towards advertising, money promotions, non-monetary promotions, product packaging and distribution intensity on CBBE components in dairy products in the Iranian market; Abril and Rodriguez-Cánovas (Citation2016) evaluate the impact of distribution intensity, promotion and in-store communication on CBBE of private label - yogurt in the Spanish market, etc.

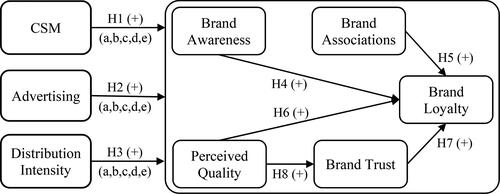

In this study, the CBBE dimensions of milk products and marketing mix activities applying by dairy milk firms popularly were explored through the direct expert interview and focus group discussion based on Aaker’s CBBE model (Aaker, Citation1991, Citation1996); and resulted in five dimensions of CBBE: brand awareness, brand associations, perceived quality, brand loyalty, and brand trust. The interrelationship among these CBBE dimensions were discussed, the two most popular marketing mix activities - advertising and distribution intensity - were identified. Twenty research hypotheses with the research model were proposed and presented in .

Brand awareness (AW) represents the ability of a (potential) buyer/user to recognize and recall a brand as an integral part of a particular product (Aaker, Citation1996; Keller, Citation2008). Brand awareness demonstrates the power of a brand existing in the minds of consumers (Hoang et al., Citation2010; Nguyen et al., Citation2011), plays an important role in purchasing and using decisions (Keller, Citation2008), helps consumers to distinguish a brand from a group of competing brands (Nguyen & Nguyen, Citation2011). Brand awareness is conceptualized as a component of CBBE demonstrated by many researchers such as Keller (Citation2008), Buil et al. (Citation2008, Citation2013a, Citation2013b), Tong and Hawley (Citation2009b), Calvo-Porral et al. (Citation2013), Ebeid (Citation2014), Su and Tong (Citation2015), and Shariq (Citation2018). Milk (product) brand awareness mentions the ability of buyers/users to recognize and recall a dairy brand through the product’s appearance (packaging, logo, label), product characteristics (flavor, taste, nutritional content) and distinguishable from other competing brands of the same type (fresh milk and/or powdered milk) available on the market through characteristics such as natural origin, organic, processing technology. Brand associations (AS) is anything related to a brand that is associated in the consumer’s mind (Aaker, Citation1991). Brand associations include all the thoughts, feelings, perceptions, impressions, experiences, beliefs, and attitudes of consumers towards a brand (Keller, Citation2006). Brand associations is conceptualized as a component of CBBE demonstrated by many researchers such as Aaker (Citation1996), Keller and Lehmann (Citation2006), Atilgan et al. (Citation2005, Citation2009), Buil et al. (Citation2008, Citation2013a), Tong and Hawley (Citation2009a, Citation2009b), Calvo-Porral et al. (Citation2013), Ebeid (Citation2014), Su and Tong (Citation2015), Shariq (Citation2018). Milk brand associations represent associations in the minds of consumers about a particular brand of milk (fresh and/or powdered) through its appearance (packaging, logo), internal characteristics (nutrition content, taste), and characteristics of dairy enterprises (constantly improving quality, caring – increasing social welfare and welfare). Perceived quality (QL) is considered as consumers’ unique perception of product quality (Netemeyer et al., Citation2004; Zeithaml, Citation1988), the subjective perception of the characteristics that a product brand gives them (Nguyen et al., Citation2011). Perceived quality is considered as a factor forming consumers’ beliefs about the brand (Cai et al., Citation2014; Kumar et al., Citation2013), is the basis for consumers to buy and use as well as compare brands (Nguyen & Nguyen, Citation2011), are reasons leading consumers to choose to buy a product brand (Hoang et al., Citation2010; Nguyen et al., Citation2011; Yoo et al., Citation2000). The perceived quality of a milk brand is considered as consumers’ subjective perception of a particular milk brand through the characteristics of a milk brand (eye-catching packaging, attractive taste, optimal nutritional content and of natural origin). Consumers perceive the quality of milk brand as superior (higher or best), that forms consumers’ beliefs, preferences, and choice (intentional decision) using the brand. Brand trust (BT) is defined as a consumer’s willingness to trust a brand’s performance (Chaudhuri & Holbrook, Citation2001), referring to the reasons consumers trust the brand that has the ability and intention to fulfill its promised requirements (Delgado-Ballester et al., Citation2003). Brand trust is derived from consumers’ experiences and interactions with the brand (Naggar & Bendary, Citation2017). It can affect branding performances directly (trial or usage) or indirectly (advertisement or word of mouth) (Keller, Citation1993; Krishnan, Citation1996), and can improve or destroy the brand-customer relationships (Keller, Citation2003). Brand loyalty (LO) implies that a particular product brand comes first in the consumers’ mind when they make a purchase decision (Gremler & Brow, Citation1996); indicates a consumer’s sympathy for the brand and will not intend to switch to another (expressed through the behavior of using, purchasing, or re-purchaing a specific product brand (Keller, Citation2008; Saydan, Citation2013). Brand loyalty should be considered in both cognitive and behavioral aspects because it represents a brand becoming the consumer’s first choice and this consequent leads to the brand being recognized and purchased again and agian (Keller, Citation2008), even when the brand changes in price or other product characteristics (Aaker, Citation1991; Chaudhuri & Holbrook, Citation2001).

Relationships between CSM and CBBE dimensions

Applying CSM is a clear trend because it connects the marketing purpose of the business with the practical requirements of the society (Andreasen, Citation1994, Citation2002; Kotler et al., Citation2012); CSM generates social and business benefits (Du et al., Citation2008); CSM increases the impression of businesses on consumers (Lichtenstein et al., Citation2004); CSM clearly demonstrates the moral function of the brand (Kapferer, Citation1997, Citation2008). CSM supports market development, increase sales or improve corporate impression (Bhattacharya et al., Citation2005; Bloom et al., Citation1997; Kotler & Lee, Citation2005); CSM differentiates businesses from competitors by forging both emotional and emotional connections with customers (Meyer, Citation1999); enhancing consumer confidence and loyalty (Inoue & Kent, Citation2012, Citation2014).

The results of the case study by Hoeffler and Keller (Citation2002) have shown that CSM initiatives can help build CBBE such as building brand awareness, enhancing brand image/associations, establishing brand credibility/trust, evoking brand feelings, creating a sense of brand commuity, and liciting brand commitment. Based on the above evidence from the literature, the following hypotheses H1 was proposed:

H1a: CSM has a significant effect on brand awareness.

H1b: CSM has a significant effect on brand association.

H1c: CSM has a significant effect on perceived quality.

H1d: CSM has a significant effect on brand trust.

H1e: CSM has a significant effect on brand loyalty.

Relationships between advertising and CBBE dimensions

Advertising is defined as any paid form of nonpersonal presentation and promotion of ideas, goods, or services by an identified sponsor via media (Kotler et al., Citation2021; Kotler & Keller, Citation2016). Advertising is a popular marketing communication tool, created to inform, remind or persuate the receiver to take some actions now or in the future (Buil et al., Citation2013b; Kotler et al., Citation2021; Kotler & Keller, Citation2016). Advertising perceived by consumers can depends on the amount of advertising investment (determined by how often the customer sees an advertisement), and the attitude towards the the advertisement (referring to the perception of the target audience of advertising messages) (Buil et al., Citation2013b; Kotler & Keller, Citation2016; Ramos & Franco, Citation2005).

Advertising has a positive relationship with brand recall, helping customers increase brand awareness (Deighton, Citation1984; Hoyer & Brown, Citation1990). Brand awareness created through marketing communications, especially advertising, is considered the main communication tool for products/services in the consumer goods market (Ailawadi et al., 2002; Ambler et al., Citation2002; Bravo et al., Citation2007; Rajh & Ozretić Došen, Citation2009).

Awareness of high ad spend helps develop higher brand awareness (Bravo et al., Citation2007, Buil et al., Citation2013b; Cobb-Walgren et al., Citation1995; Simon & Sullivan, Citation1993; Yoo et al., Citation2000). In other words, spending on brand advertising can increase brand exposure, and therefore, increased brand awareness (Keller, Citation2008). In addition, through fresh, innovative, and disruptive advertising messages, firms can attract more customers, leading to higher brand awareness (Aaker, Citation1991; Buil et al., Citation2013b).

Many research results show that the higher the advertising spend for the brand, the better associations will be formed in the customer’s mind (Bravo et al., Citation2007; Yoo et al., Citation2000). Furthermore, the company can develop strong, favorable, and unique brand associations through creative messaging (Aaker. 1991; Buil et al., Citation2013b). Several previous studies have shown a link between advertising and perceived quality (Aaker & Jacobson, Citation1994; Kirmani & Wright, Citation1989; Milgrom & Roberts, Citation1986). Spending ‘heavy’ on advertising demonstrates that an organization is investing in a brand, which creates a perceived superior quality (Kirmani & Wright, Citation1989; Ramos & Franco, Citation2005; Yoo et al., Citation2000).

In addition, companies can increase perceived quality through original, creative, and novel advertising messages (Aaker, Citation1991; Buil et al., Citation2013b); and subsequently, advertising helps support purchasing decisions by increasing brand equity (Karunanithy & Sivesan, Citation2013). Advertising increases the probability of a brand being selected from a pool of alternatives; thus, the decision-making process is simplified at the same time, as customer habits are created and lead to brand loyalty (Shimp, Citation1997; Yoo et al., Citation2000; and Ramos & Franco, Citation2005). Furthermore, the level of advertising spend increases the value of the product, supporting the purchase decision of the consumer (Archibald et al., Citation1983; Yoo et al., Citation2000).

Kirmani and Wright (Citation1989) emphasized the direct positive effect of advertising on brand trust by focusing on the importance of spreading accurate and honest messages. Through advertising, people get a sense of ‘guaranteed’ for the brand being sold in the market; Once customers see the ad, they gain a sense of confidence and develop expectations and beliefs about the brand (Kotler et al., Citation2021). Based on the above evidence from the literature, we hypothesized H2 as follows:

H2a: Advertising has a positive effect on brand awareness.

H2b: Advertising has a positive effect on brand associations.

H2c: Advertising has a positive effect on perceived quality.

H2d: Advertising has a positive effect on brand trust.

H2e: Advertising has a positive effect on brand loyalty.

Relationships between distribution intensity and CBBE dimensions

In marketing (consumer goods), there are many studies showing that distribution channel expansion/development contributes to branding process, increasing brand equity (Dodds et al., Citation1991; Grewal et al., Citation1998; Kim & Hyun, Citation2011; Nguyen Viet & Nguyen Anh, Citation2021; Nguyen et al., Citation2011; Yoo et al., Citation2000). Distribution intensity refers to the number of outlets used by a producer in its commercial area; considered as a product that is available in a large number of stores to satisfy a customer’s purchase (Yoo et al., Citation2000). High distribution intensity has a positive effect on the increase of CBBE because it increases the probability of buying the brand wherever and whenever the consumer wants (Farris et al., Citation1989; Yoo et al., Citation2000, Kim & Hyun, Citation2011).

High distribution intensity enhances brand awareness and recognition (Ebeid, Citation2014; Nguyen et al., Citation2011; Srinivasan et al., Citation2005). The increase in distribution intensity reduces the effort of consumers in finding and buying the brand, they perceive the brand as more valuable, thereby increasing satisfaction and brand loyalty. Yoo et al., Citation2000). Increased distribution intensity leads to higher customer satisfaction, perceived quality and brand loyalty, and ultimately, higher brand equity (Heidarzadeh & Zarbi, Citation2008).

Several previous studies have shown that distribution intensity has a positive impact on perceived quality and brand loyalty (Ebeid, Citation2014; Kim & Hyun, Citation2011; Yoo et al., Citation2000). In addition, Huang and Sarigöllü (Citation2012) found that increasing distribution intensity gives consumers repeated exposure to the product brand, which in turn leads to increased awareness and hence increased awareness. improve brand associations. It can be argued that distribution intensity has a positive effect on the formation and enhancement of brand associations.

Distribution intensity provides added value through a reduction in the costs consumers have to trade in order to obtain the product (Yoo et al., Citation2000). On the other hand, as De Chernatony and Cottam (Citation2006) mentioned, trust acts as a tool to help reduce risk – helping to reassure customers. It can be argued that the wider the distribution channel (increasing the intensity), the greater the opportunity for consumers to recognize, interact with or come into contact with the brand, which can form brand trust, leading to purchase intention or repurchase. Based on the above evidence, the following hypothesis H3 was proposed:

H3a: Distribution intensity has a positive effect on brand awareness.

H3b: Distribution intensity has a positive effect on brand associations.

H3c: Distribution intensity has a positive i effect on perceived quality.

H3d: Distribution intensity has a positive effect on brand trust.

H3e: Distribution intensity has a positive effect on brand loyalty.

Relationships among CBBE dimensions

For consumers to have brand loyalty, the first things are that they must have brand knowledge, be able to aware or distinguish a particular brand from other brands (with the same product) present in the market (Aaker, Citation1991, Citation1996; Pappu et al., Citation2005). Brand associations are the key antecedent for consumers to make their purchasing decisions and create their loyalty to the brand (Aaker, Citation1991; Atilgan et al., Citation2005). Once consumers perceive a brand to be of higher quality than other brands (with the same product) available on the market, it will make them decide to buy or repurchase that product brand (Nguyen et al., Citation2011), leading to enhanced brand loyalty (Yoo et al., Citation2000; Buil et al., Citation2013b).

Brand trust is the trigger for consumers’ commitment to choose, use and repurchase a brand (Delgado-Ballester et al., Citation2003; Yannopoulou et al., Citation2011), an important element in creating successfully build and maintain the strong link between consumers and brands (Atilgan et al., Citation2009; Hiscock, Citation2001; LaBahn & Kohli, Citation1997). In other words, brand trust is an actecedent for increasing brand loyalty (Chaudhuri & Holbrook, Citation2001; Kumar et al., Citation2013; Power et al., Citation2008). In addition, some authors argue that once customers experience the more engaged with the brand, the better the perceived quality, the good experiences will form brand trust, thereby leading to brand loyalty (Kumar et al., Citation2013; Nguyen Viet & Nguyen Anh, Citation2021). The following hypotheses were summarized the arguments above:

H4: Brand awareness has a significant effect on brand loyalty.

H5: Brand association has a significant effect on brand loyalty.

H6: Perceived quality has a significant effect on brand loyalty.

H7: Brand trust has a significant effect on brand loyalty.

H8: Perceived quality has a significant effect on brand trust.

Data collection and processing

The data used in this study collected from survey questionnaires; thereore, the development of the measurement scales of latent variables needed to be conducted. To develop the measurement scales of 8 latent variables in the research model, focus group and pilot test were conducted. Two focus group discussions with 13 customers who over 18 years old, and often purchase directly and use dairy products at popular shopping points in Ho Chi Minh City were conducted and resulted in 51 items (statements). To test the reliability of the measurement scales, the pilot test was carried out on 100 survey questionnaires by using exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and calculating Cronbach’ Alpha coefficient. Finally, 35 observable items were found which were used to develop the official survey questionnaire to collect data to test the twenty research hypotheses presented in the proposed research model.

According to reports by EVBN (EU-Vietnam Business Network) (Citation2016) and Kanta WorldPanel (Citation2016/2019), urban areas in Vietnam have about 3 times more spending on dairy products than rural areas; Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC) and Hanoi are the two largest consumption markets, with the total annual spending on dairy products accounting for more than 20% of the whole country, in which, the total expenditure on dairy products of Hanoi people are about 70% compared to HCMC.

The convenience sampling technique was applied. The participants of this study were consumers, both men and women over 18 years old, who have been living and working in two big cities in Vietnam (Ho Chi Minh and Hanoi), in 2020. The population was limited to only who directly and regularly purchase/use powdered milk and/or fresh milk brands from dairy companies in Vietnam. The face-to-face interviews took place at supermarkets, shops specializing in selling dairy products, and convenience stores. The entire research sample was conducted through the Vietnam Advertising Research and Training Institute (ARTI Vietnam). About 500 people (in HCMC) and 350 people (in Hanoi) were approached through direct interviewing by the survey questionnaires designed on 5-point Likert scale, and resulted in 780 valid questionnaires. shows the characteristics of the research sample.

Table 1. Sample characteristics.

Data processing was carried out through 3 steps: data screening, measurement assessment, and evaluation of the structural model. As a preliminary step, the data screening process included visually inspecting data for identifying missing data and testing violations of normality statistical assumptions. The next step employed are Exploring Factor Analysis (EFA) and Confirm Factor Analysis (CFA) for measurement assessment.

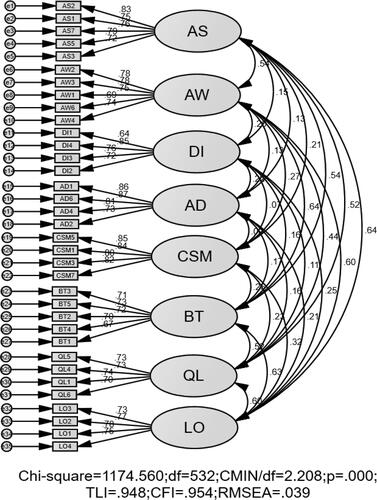

The internal consistency of the items of each construct was measured using Cronbach’s α with minimum requirement of Cronbach’s α coefficients is 0.6 (Hair et al., Citation2010). The Cronbach’s α coefficients ranged from 0.815–0.897 in this study. The minimum requirement of composite reliability is 0.6 (Hair et al., Citation2010), and the value of the construct reliability ranged from 0.815–0.897. The minimum requirement of factor loading was 0.5 (Hair et al., Citation2010). The value of the factor loading ranged from 0.689–0.888 in this study. All indicators of composite reliability (CR), ranged from 0.815–0.897 in this study, are higher than minimum requirement of 0.6 (Hair et al., Citation2010). To test the validity of the measurements, we used average variance extracted (AVE) to evaluate the discriminant validity of the measurements (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). In this study, the average variance extracted (AVE) are greater than the criterion of 0.5 (Hair et al., Citation2010) for all constructs. The measurement scales meet the criteria of discriminant value, unidimensional, convergence value as shown in and .

Table 2. Results of Exploring Factor Analysis (EFA).

Table 3. Results of reliability, construct validity of research concepts.

Testing measurement model (CFA) resulted in that all criteria meet standards of the model good fit indicators (Chi-square χ2 = 1174.560 (p =.000); CMIN/df = 2.208 (< 5 (Schumacker & Lomax, Citation2004)), TLI =.948 (> 0.9 (Hair et al., Citation2010)), CFI =.954 (> 0.9 (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999), and RMSEA = .039 (< 0.07 (Hair et al., Citation2010)) are accepted (shown in ).

Figure 2. Testing CFA results.

Notes: Cmin/df < 5 (Schumacker & Lomax, Citation2004), TLI > 0.90 (Hair et al., Citation2010), CFI > 0.90 (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999), RMSEA < 0.07 (Hair et al., Citation2010).

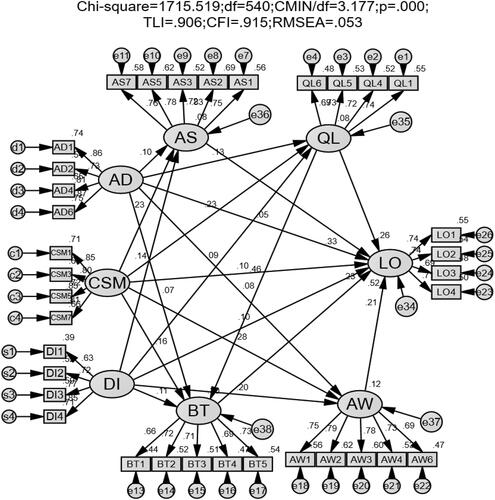

The results of the linear structure analysis (SEM) presented in show that the model is compatible with market data because of Chi-square χ2 = 1715,519, degrees of freedom df = 540 (p - value = 0.000), Cmin/df = 3.177 (< 5), TLI = 0.906 (> 0.9), CFI = 0.915 (> 0.9), and RMSEA = 0.053 (< 0.07).

The results of testing research hypotheses

Testing the research hypotheses () showed that the relationship between AD and LO is not accepted at the significance level of 0.05 (P-value = 0.151). Hypothesis H2d assumes the relationship between AD and BT is accepted at 10% significance level (P = 0.062). The remaining 18 hypotheses are accepted at 5% significance level.

Table 4. Results of testing research hypotheses.

Multigroup analysis for difference

To test the differences between groups, multigroup analysis was used, including variable and partial invariant models. In the variable method, the estimated parameters in each model of the groups are not constrained. In the partial invariant method, the measurement components are not constrained, but the relationships between the concepts in the research model are fixed to be the same for all groups. Chi-squared test was used to compare the two models. If the chi-square test shows that there is no difference between the invariant and the variable model (p-value > 0.05), the invariant model will be chosen because it has higher degrees of freedom. Conversely, if the Chi-square difference is significant (p - value < 0.05), the variable model is chosen because of its higher compatibility (Nguyen & Nguyen, Citation2009, Citation2011). The results of testing the difference of compatibility criteria () showed that there is no difference between the invariant (partial) and variable models (P - value > 0.05) or confirmed that the impacts of CSM, distribution intensity and advertising on CBBE components are not affected by different consumer groups in purchasing different categories milk with different brand origin.

Table 5. Analysis results for difference between groups.

Finding discussion, recommendations, and limitation

Firstly, the research results show that CSM activities have a positive impact on consumers’ perception, attitude, and intention - behavior. The results imply that, nowadays consumers using dairy products identify and differentiate forms of CSM; they have been very interested in CSM, supporting brands. The results support the recommendation on CSM from the perspective of consumer perception and behavior of many authors (e.g. Deshpande, Citation2016; Hoeffler et al., Citation2006; Inoue & Kent, Citation2014; Truong & Hall, Citation2016). The results reinforced the conclusions of many authors such as CSM is increasingly widely applied (Drumwright, Citation1996; Drumwright & Murphy, Citation2001); the tendency to use CSM is increasing (Hoeffler & Keller, Citation2002; Truong & Hall, Citation2013, Citation2016); application of CSM is a clear trend because it connects the marketing activities of the business with the practical requirements of society (Andreasen, Citation1994, Citation2002; Kotler et al., Citation2012); CSM generates social benefits and business profits (Du et al., Citation2008); CSM increases both emotional and mental association with customers (Meyer, Citation1999), and impressions (associations) of businesses (Lichtenstein et al., Citation2004), etc.

Secondly, the positive impact of CSM, advertising, and distribution density on CBBE components imply that brand marketing program of dairy businesses should combine CSM programs with traditional marketing activites such as advertising and distribution density to incresase the effect of marketing activities on CBBE, due to the impact of CSM on CBBE components is stronger than that of advertising and distribution density supported by standardized beta coefficient (see ). This result encourages dairy businesses to invest more in CSM initiatives/programs – consistent with the assertions – CSM of a business can create advantages to brand to win the heart and mind of skeptical consumers in hypercompetitive marketplace (Hoeffler et al., Citation2006, p. 55); CSM supports market development, increase sales or improve corporate impression (Bhattacharya et al., Citation2005; Bloom et al., Citation1997; Kotler & Lee, Citation2005); CSM differentiates a business from its competitors by forging emotional and spiritual bonds with consumers (Meyer, Citation1999); enhance credibility (perception and belief about attributes or characteristics of the business) and consumer loyalty towards the business (Inoue & Kent, Citation2012, Citation2014).

Thirdly, for dairy industry in Vietnam market, brand loyalty is directly affected by 04 other components of CBBE: brand awareness, brand association, perceived quality, brand trust implies that customers are loyal with milk brands having superior quality; good taste, beautiful, and eye-catching packaging. Their loyalty will increase the CBBE of that dairy product.

The concept of brand trust is first tested in the dairy industry in Vietnam, and exists in the perception of Vietnamese consumers (Nielsen, Citation2017), because it is closely related to the success of brands and businesses (Interbrand, Citation2018), and creates an opportunity for businesses to develop their brands (Bainbridge, Citation1997); as a mean to build, maintain and upgrade the perception of consumers to brand equity (Atilgan et al., Citation2009; Hiscock, Citation2001; Keller, Citation2003; LaBahn & Kohli, Citation1997); and then impact on consumption behavior (Keller, Citation1993; Krishnan, Citation1996).

The study findings contribute to some of the theorical implications. This study adds to the existing literature in several ways: (1) propose a research model to evaluate the impact of marketing on five dimensions of CBBE based on the perspective of Cognitive Consumer Behavior, namely the TPB model (Ajzen, Citation1985, Citation1991, Citation2019), (2) identify factors building CBBE which represents a key priority for academics and marketers (Baldauf et al., Citation2009). From practical perspective, this study confirmed to role of CSM in building the dairy brand by investigating how CSM initiatives, one of the effective sustainable marketing strategies for boosting firms’s concerns and consumers engagement, affects towards CBBE dimensions. The study finds the five dimensions of CBBE and the causal relationships among these dimensions, which provides useful insights in the brand marketing tasks of companies (Buil et al., Citation2013b; Lehmann et al., Citation2008).

The research’ results have supplemented and reinforced the findings and comments from previous studies; thereby, the empirical evidence of the impact of CSM based on consumer perception on CBBE in dairy industry in a transition market like Vietnam has been found, however, the generalizability of the research’s findings may be low because the study was conducted in a specific industry. Further research suggested should be a comparative study between different industries in the same country, or between different countries with the same industry. It is expected that the further research’s findings will bring more insights into the role of CSM in company branding.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Thi Quy Vo

Thi Quy Vo, School of Business, International University, Vietnam National University, HCM, Quarter 6, Linh Trung Ward, Thu Duc City, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. She is working for International University being university member of Vietnam National University Ho Chi Minh (VNUHCM) as a senior lecturer. Currently, she is the Director of Academic Programme and key trainer of SMEI Vietnam for training professional certification in Sales & Marketing International in Vietnam. She completed her master’s and Ph.D. Degrees from the Asian Institute ofTechnology (AIT) specialized in International Business. She was promoted to associate professor in 2012. She has been the holder of CME® - Certified Marketing Executive® from 2011 to the present. She has published more than 50 publications in both international journals and domestic journals. Her scientific articles focus on firm performance, bank efficiency, and customer behavior. She also wrote business cases book in Vietnamese published by VNU Press (2019), a domestic prestigious publisher and they have been used to teach students specialized in business administration major.

Tuan Nguyen-Anh

Tuan Nguyen-Anh, Marketing Faculty, University of Finance – Marketing, Ho Cho Minh City, Vietnam; He have been working for University of Finance – Marketing (UFM) as a lecturer in field marketing from 2004 to now. He completed his MBA (in 2004) and degree of Ph.D in Management (in 2021) from the University of Economics, HCM. He is actively involved in research, particularly in the field of marketing, suatainable marketing, brand management and public relations. He has published many research papers in various journals of National and International repute. He is co-author Marketing Management book in Vietnamese published by VNU Press (2016), and they have been used to teach students specialized in marketing major, UFM.

References

- Aaker, D. A. (1991). Managing brand equity. The Free Press.

- Aaker, D. A. (1996). Building strong brands. The Free Press.

- Aaker, D. A., & Joachimsthaler, E. (2000). Brand Leadership. The Free Press.

- Aaker, D. A., & Jacobson, R. (1994). The financial information content of perceived quality. Journal of Marketing Research, 31(2), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224379403100204

- Abril, C., & Rodriguez-Cánovas, B. (2016). Marketing mix effects on private labels brand equity. European Journal of Management and Business Economics, 25(3), 168–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redeen.2016.09.003

- Ailawadi, K., Lehmann, D., & Neslin, S. (2003). Revenue premium as an outcome measure of brand equity. Journal of Marketing, 67(4), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.67.4.1.18688

- Ajzen, I. (2019). The Theory of Planned Behavior. http://www.people.umass.edu/aizen/tpb.html.

- Ajzen, I. (2011). The theory of planned behaviour: Reactions and reflections. Psychology & Health, 26(9), 1113–1127. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2011.613995

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behaviour. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Ajzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: a theory of planned behavior. In J. Kuhl and J. Beckman (Eds.), Action-control: From Cognition to Behaviour (pp. 11–39). Springer.

- Ambler, T., Bhattacharya, C. B., Edell, J., Keller, K. L., Lemon, K. N., & Mittal, V. (2002). Relating brand and customer perspectives on marketing management. Journal of Service Research, 5(1), 13–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670502005001003

- Anderson, J. (2007). Brand Equity: The Perpetuity Perspective [Paper presentation]. Winter 2007 Proceedings of the American Marketing Association.

- Andreasen, A. R. (2002). Marketing social marketing in the social change marketplace. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 21(1), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1509/jppm.21.1.3.17602

- Andreasen, A. R. (1994). Social marketing: Its definition and domain. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 13(1), 108–114. https://doi.org/10.1177/074391569401300109

- Atilgan, E., Akinci, S., Aksoy, S., & Kaynak, E. (2009). Customer-based brand equity for global brands: A multinational approach. Journal of Euromarketing, 18(2), 115–132. https://doi.org/10.9768/0018.02.115

- Atilgan, E., Akinci, S., Aksoy, S., & Kaynak, E. (2005). Determinants of the brand equity: A verification approach in the beverage industry in Turkey. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 23(3), 237–248. https://doi.org/10.1108/02634500510597283

- Archibald, R. B., Haulman, C. A., & Moody, C. E. J. (1983). Quality, price, advertising and published quality ratings. Journal of Consumer Research, 9(4), 347–356. https://doi.org/10.1086/208929

- Baalbaki, S., & Guzmán, F. (2017). Customer-base brand equity. Routledge Companion Chapter.

- Baldauf, A., Cravens, K. S., Diamantopoulos, A., & Zeugner-Roth, K. P. (2009). The impact of product–country image and marketing efforts on retailer-perceived brand equity: An empirical analysis. Journal of Retailing, 85(4), 437–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2009.04.004

- Bainbridge, W. (1997). The Sociology of Religious Movements. Routledge.

- Baker, C., Nancarrow, C., & Tinson, J. (2005). The mind versus market share guide to brand equity. International Journal of Marketing Research, 47(5), 525–542.

- Baldauf, A., Cravens, K. S., & Binder, G. (2003). Performance consequences of brand equity management: evidence from organizations in the value chain. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 12(4), 220–236. https://doi.org/10.1108/10610420310485032

- Barone, M. J., Miyazaki, A. D., & Taylor, K. A. (2000). The influences of cause-related marketing on consumer choice: does one good turn deserve another? Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28(2), 248–262. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070300282006

- Barth, M. E., Clement, M. N., Foster, G., & Kasznik, R. (1998). Brand values and capital market valuation. Review of Accounting Studies, 3(1/2), 41–68. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009620132177

- Bendixen, M., Bukasa, K. A., & Abratt, R. (2004). Brand equity in the business-to- business market. Industrial Marketing Management, 33(5), 371–380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2003.10.001

- Bhattacharya, C. B., & Sen, S. (2003). Consumer-company identification: a framework for understanding consumers’ relationships with companies. Journal of Marketing, 67(2), 76–88. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.67.2.76.18609

- Bhattacharya, C. B., Du, S., & Sen, S. (2005). Convergence of Interests–Producing Social and Business Gains Through Corporate Social Marketing, Center for Responsible Business, Working Paper Series, Paper 29, University of California.

- Bick, G. N. C. (2009). Increasing shareholder value through building customer and brand equity. Journal of Marketing Management, 25(1-2), 117–141. https://doi.org/10.1362/026725709X410061

- Bloom, P. N., Hussein, P. Y., & Szykman, L. R. (1997). The benefits of corporate social marketing initiatives. In M. E. Goldberg, M. Fishbein, and S. E. Middlestadt (Eds.), Social Marketing: Theoretical and practical perspectives (pp. 313–331). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Bray, J. (2008). Consumer Behavior Theory: Approachs and Models. Bournemouth University. Discussion Paper.

- Bravo, R., Fraj, E., & Matinez, F. (2007). Family as source of consumer-based brand equity. The Journal of Product and Brand Management, 16(3), 188–199.

- Brown, T. J., & Dacin, P. A. (1997). The company and the product: corporate associations and consumer product responses. Journal of Marketing, 61(1), 68–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299706100106

- Buil, I., Martínez, E., & de Chernatony, L. (2013a). The influence of brand equity on consumer responses. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 30(1), 62–74. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363761311290849

- Buil, I., de Chernatony, L., & Martínez, E. (2013b). Examining the role of advertising and sales promotions in brand equity creation. Journal of Business Research, 66(1), 115–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.07.030

- Buil, I., de Chernatony, L., & Martínez, E. (2008). A Cross-National Validation of the Consumer-Based Brand Equity Scale. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 17(6), 384–392. https://doi.org/10.1108/10610420810904121

- Cai, Y., Zhao, G., & He, J. (2014). Influences of two modes of intergenerational communication on brand equity. Journal of Business Research, 68(3), 553–560. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.09.007

- Calvo-Porral, C., Bourgault, N., Calvo Dopico, D. (2013). Brewing the Recipe for Beer Brand Equity. European Research Studies Journal, XVI (Issue 2), 82–97. https://doi.org/10.35808/ersj/390

- Chen, A. C. H. (2001). Using free association to examine the relationship between characteristics of brand associations and brand equity. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 10(7), 439–451.

- Chaudhuri, A., & Holbrook, M. B. (2001). The chain of effects from brand trust and brand effect to brand performance: the role of brand loyalty. Journal of Marketing, 65(2), 81–93. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.65.2.81.18255

- Christodoulides, G., & De Chernatony, L. (2010). Consumer – based brand equity conceptualisation and measurement: A literature review. International Journal of Market Research, 52(1), 43–66. https://doi.org/10.2501/S1470785310201053

- Cobb-Walgren, C. J., Ruble, C., & Donthu, N. (1995). Brand Equity, Brand Preference, and Purchase Intent. Journal of Advertising, 24(3), 25–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.1995.10673481

- Davcik, N. S., Vinhas da Silva, R., & Hair, J. F. (2015). Towards a unified theory of brand equity: conceptualizations, taxonomy and avenues for future research. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 24(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-06-2014-0639

- De Chernatony, L., & Cottam, S. (2006). Why are financial services brands not great? Journal of Product & Brand Management, 15(2), 88–97. https://doi.org/10.1108/10610420610658929

- De Chernatony, L., Cottam, S., & Segal-Horn, S. (2006). Communicating services brands’ values internally and externally. The Service Industries Journal, 26(8), 819–836. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642060601011616

- Deighton, J. (1984). The interaction of advertising and evidence. Journal of Consumer Research, 11(3), 763–770. https://doi.org/10.1086/209012

- Delgado-Ballester, E., Munuera-Aleman, J. L., & Yague, M. J. (2003). Development and validation of a brand trust scale. International Journal of Market Research, 45(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/147078530304500103

- Deshpande, S. (2016). Corporate social marketing: Harmonious symphony or cacophonous noise? Social Marketing Quarterly, 22(4), 255–263. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524500416674291

- Dilotsotlhe, N. (2021). Factors influencing the green purchase behaviour of millennials: An emerging country perspective. Cogent Business & Management, 8(1), 1908745. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2021.1908745

- Dodds, W. B., Monroe, K. B., & Grewal, D. (1991). Effects of price, brand, and store information on buyers’ product evaluations. Journal of Marketing Research, 28(3), 307–319. https://doi.org/10.2307/3172866

- Doyle, P. (2001). Shareholder-value-based brand strategies. Journal of Brand Management, 9(1), 20–30. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.bm.2540049

- Drumwright, M. E. (1996). Company advertising with social dimension: The role of noneconomic criteria. Journal of Marketing, 60(4), 71–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299606000407

- Drumwright, M. E., & Murphy, P. E. (2001). Corporate societal marketing. In P. N. Bloom and G. T. Gundlach (Eds.), Handkook of Marketing and Society (pp. 162–183). Sage Publications.

- Du, S., Sen, S., & Bhattacharya, C. B. (2008). Exploring the social and business returns of a corporate oral health initiative aimed at disadvantaged Hispanic families. Journal of Consumer Research, 35(3), 483–494. https://doi.org/10.1086/588571

- Dyson, P., Farr, A., & Hollis, N. S. (1996). Understanding, measuring, and using brand equity. Journal of Advertising Research, 36(6), 9–21.

- Ebeid, A. Y. (2014). Distribution intensity, advertising, moneytary promotion, and customer-based brand equity: An applied study in Egypt. International Journal of Marketing Studies, 6(4), 113–122. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijms.v6n4p113

- EVBN (EU-Vietnam Business Network). (2016). Vietnam Diary Report 2016.

- Ellen, P. S., Wiener, J. L., & Cobb-Walgren, C. (1991). The role of perceived consumer effectiveness in motivating environmentally conscious behaviors. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 10(2), 102–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/074391569101000206

- Emery, B. (2012). Sustainable Marketing. Pearson.

- Epstein, M. J., & Westbrook, R. A. (2001). Linking actions to profits in strategic decision making. MIT Sloan Management Review, 42(Spring), 39–49.

- Farquhar, P. H., Julia, Y. H., & Yuji, I. (1991). Recognizing and measuring brand assets. Marketing Science Institute Working Paper Series, Report No. 91–119. Marketing Science Institute.

- Farris, P., Olver, J., & De Kluyver, C. (1989). The Relationship between distribution and market share. Marketing Science, 8(2), 107–128. https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.8.2.107

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Addison-Wesley.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Gordon, R., Carrigan, M., & Hastings, G. (2011). A framework for sustainable marketing. Marketing Theory, 11(2), 143–163. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593111403218

- Gremler, D., & Brow, S. W. (1996). The Loyalty ripple effect: apreciating the full value of customers. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 10(3), 271–293. https://doi.org/10.1108/09564239910276872

- Grewal, D., Krishnan, R., Baker, J., & Borin, N. A. (1998). The effect of store name, brand name and price discounts on cosumer evaluation and purchase intentions. Journal of Retailing, 74(3), 331–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4359(99)80099-2

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Prentice Hall.

- Heidarzadeh, K., & Zarbi, S. A. (2008). The affect of selected marketing mix elements on brand equity. Jounal of Marketing Management, 3(5), 21–58.

- Hiscock, J. (2001). Most trusted brands. Journal of Marketing, 1(March), 32–33.

- Hoang, T. P. T., Hoang, T., & Chu, N. M. N. (2010). Developing measurements of brand equity in the service market. University of Economics Ho Chi Minh City.

- Hoeffler, S., Bloom, P., Keller, K. L., & Meza, C. E. (2006). How social–cause marketing affects consumer perceptions. MIT Sloan Management Review, 47(2), 49–55.

- Hoeffler, S., & Keller, K. L. (2002). Building brand equity throught corporate societal marketing. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 21(1), 78–89. https://doi.org/10.1509/jppm.21.1.78.17600

- Hoyer, W. D., & Brown, S. P. (1990). Effects of brand awareness on choice for a common repeat purchase product. Journal of Consumer Research, 17(2), 141–148. https://doi.org/10.1086/208544

- Hsieh, M. (2004). Measuring global brand equity using cross–national survey data. Journal of International Marketing, 12(2), 28–57. https://doi.org/10.1509/jimk.12.2.28.32897

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Huang, R., & Sarigöllü, E. (2012). How brand awareness relates to market outcome, brand equity, and the marketing mix. Journal of Business Research, 65(1), 92–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.02.003

- Inoue, Y., & Kent, A. (2014). A conceptual framword for understanding the effects of corporate social marketing on consumer behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 121(4), 621–633. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1742-y

- Inoue, Y., & Kent, A. (2012). Investigating the role of corporate credibility in corporate social marketing: A case study of environtmental initiatives by professional sport organizations. Sport Management Review, 15(3), 330–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2011.12.002

- Interbrand. (2018). Brave Brands are Trust Brands. https://www.interbrand.com/best-brands/best-global-brands/2018/articles/brave-brands-are-trusted-brands/.

- Jafari Drabjerdi, J., Arabi, M., & Haghighikhah, M. (2016). Identifying the Effective Factors on Brand Equity from Consumers Perspective Using Aaker Model: A Case of Tehran Dairy Products. International Journal of Business and Management, 11(4), 265–273. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijbm.v11n4p265

- Kanta WorldPanel. (2016/2019). 2109. Insigh Hanbook 2016; Insigh Hanbook 2019.

- Kapferer, J.-N. (2008). The New Strategic Brand Management: creating and sustaning brand equity long (4th ed). Kogan Page.

- Kapferer, J.-N. (1997). Strategic Brand Management., Great Britain, Kogan Page.

- Kartono, B., & Rao, V. R. (2009a). Linking consumer-based brand equity to market performance: An integrated approach to brand equity management. Johnson School Research Paper Series No. 23–09.

- Kartono, B., & Rao, V. R. (2009b). Brand equity measurement: Comparative review and a normative guide. Johnson School Research Paper Series No. 24–09.

- Karunanithy, M., & Sivesan, S. (2013). An empirical study on the promotional mix and brand equity: mobile service providers. Industrial Engineering Letters, 3, 1–9.

- Keller, K. L., & Lehmann, D. R. (2006). Brands and branding: Research findings and future priorities. Marketing Science, 25(6), 740–759. https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.1050.0153

- Keller, K. L., & Lehmann, D. R. (2003). How do brands create value? Marketing Management, 12(3), 26–31.

- Keller, K. L. (2003). Brand synthesis: The multidimensionality of brand knowledge. Journal of Consumer Research, 29(4), 595–600. https://doi.org/10.1086/346254

- Keller, K. L. (2008). Strategic Brand Management: Building, Measuring and Managing Brand Equity., (3rd ed.). Prentice Hall.

- Keller, K. L. (2006). Measuring brand equity. In R. Grover and M. Vriens (Eds.), Handbook of marketing research – Do’s and don’ts. Sage.

- Keller, K. L. (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing consumer-based brand equity. Journal of Marketing, 57(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299305700101

- Kim, J. H., & Hyun, Y. J. (2011). A model to investigate the influence of marketing-mix on brand equity in the IT software sector. Industrial Marketing Management, 40(3), 424–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2010.06.024

- Kim, H-b., Gon Kim, W., & An, J. A. (2003). The Effect of Consumer- Based Brand Equity on Firms’ Financial Performance. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 20(4), 335–351. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363760310483694

- Kirmani, A., & Wright, P. (1989). Money talks: Perceived advertising expense and expected product quality. Journal of Consumer Research, 16(3), 344–353. https://doi.org/10.1086/209220

- Koçak, A., Abimbola, T., & Özer, A. (2007). Consumer brand equity in a cross- cultural replication: An evaluation of a scale. Journal of Marketing Management, 23(1-2), 157–173. https://doi.org/10.1362/026725707X178611

- Kotler, P. (2011). Reinventing marketing to manage the environmental imperative. Journal of Marketing, 75(4), 132–135. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.75.4.132

- Kotler, P. (2009). Marketing management (1st ed.). Prentice Hall International.

- Kotler, P. (1972). What consumerism means for marketers. Harvard Business Review, 50(May/June), 48–57.

- Kotler, P., Armstrong, G., & Opresnik, M. O. (2021). Principles of marketing (18th ed.). Pearson Education, Ltd., Prentice Hall.

- Kotler, P., & Keller, K. L. (2016). Marketing management (15th ed.). Pearson Education, Ltd., Prentice Hall.

- Kotler, P., Hesseikel, D., & Lee, N. (2012). Good Works! Marketing and Corporate Initiatives That Build a Better World … and the Bottom Line. Wiley.

- Kotler, P., & Lee, N. (2005). Best of breed: When it comes to gaining a market edge while supporting a social cause, ‘‘corporate social marketing’’ leads the pack. Social Marketing Quarterly, 11(3-4), 91–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/15245000500414480

- Kotler, P., & Zaltman, G. (1971). Social marketing: An approach to planned social change. Journal of Marketing, 35(3), 3–12.

- Kim, Y., & Choi, S. M. (2005). Antecedents of Green Purchase Behavior: An Examination of Collectivism, Environmental Concern, and PCE. Advances in Consumer Research, 32, 592–599.

- Krishnan, H. S. (1996). Characteristics of memory associations: a consumer-based brand equity perspective. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 13(4), 389–405. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-8116(96)00021-3

- Kumar, R., Dash, S., & Purwar, P. (2013). The nature and antecedents of brand equity and its dimensions. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 31(2), 141–159. https://doi.org/10.1108/02634501311312044

- LaBahn, D. W., & Kohli, C. (1997). Maintaining client commitment in advertising agency-client relationships. Industrial Marketing Management, 26(6), 497–508. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0019-8501(97)00025-4

- Lassar, W., Mittal, B., & Sharma, A. (1995). Measuring consumer-based brand equity. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 12(4), 11–19. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363769510095270

- Lee, E. M., Park, S. Y., Rapert, M. I., & Newman, C. L. (2011). Dose perceived consumer fit matter in corporate social responsibility issues? Journal of Business Research, 65(11), 1558–1564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.02.040

- Lefebvre, R. C. (2012). Transformative social marketing: co-creating the social marketing discipline and brand. Journal of Social Marketing, 2(2), 118–129. https://doi.org/10.1108/20426761211243955

- Lefebvre, R. C. (2011). An integrative model for social marketing. Journal of Social Marketing, 1(1), 54–72. https://doi.org/10.1108/20426761111104437

- Lehmann, D. R., Keller, K. L., & Farley, J. U. (2008). The structure of survey–based brand metrics. Journal of International Marketing, 16(4), 29–56. https://doi.org/10.1509/jimk.16.4.29

- Li, S., & Jaharuddin, N. S. (2021). Influences of background factors on consumers’ purchase intention in China’s organic food market: Assessing moderating role of word-of-mouth (WOM). Cogent Business & Management, 8(1), 1-26. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2021.1876296

- Lichtenstein, D. R., Drumwright, M. E., & Braig, B. M. (2004). The effects of corporate social responsibility on customer donations to corporate-supported nonprofits. Journal of Marketing, 68(4), 16–32. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.68.4.16.42726

- Luo, X., & Bhattacharya, C. B. (2006). Corporate social responsibility, customer satisfaction, and market value. Journal of Marketing, 70(4), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.70.4.001

- Martin, D., & Schouten, J. (2012). Sustainable Marketing. Peason.

- Milgrom, P., & Roberts, J. (1986). Price and advertising signals of product quality. Journal of Political Economy, 94(4), 796–821. https://doi.org/10.1086/261408

- Mizik, N., & Jacobson, R. (2009). Valuing branded businesses. Journal of Marketing, 73(6), 137–153. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.73.6.137

- Meyer, H. (1999). When the Cause is Just. Journal of Business Strategy, 20(6), 27–31. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb040042

- Naggar, N. A., & Bendary, N. (2017). The Impact of Experience and Brand trust on Brand loyalty, while considering the mediating effect of brand Equity dimensions, an empirical study on mobile operator subscribers in Egypt. The Business and Management Review, 9(2), 16–26.

- Netemeyer, R. G., Krishnan, B., Pullig, C., Wang, G., Yagci, M., Dean, D., Ricks, J., & Wirth, F. (2004). Developing and validating measures of facets of customer-based brand equity. Journal of Business Research, 57(2), 209–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(01)00303-4

- Nguyen, D. T., Nigel, J. B., & Kenneth, E. M. (2011). Brand loyalty in emerging markets. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 29(3), 222–232. https://doi.org/10.1108/02634501111129211

- Nguyen, D. T., & Nguyen, T. M. T. (2011). Brand value in the consumer goods market. In Scientific Research Marketing: Application of SEM model (pp. 3–85). Labor Publishing House.

- Nguyen, D. T., & Nguyen, T. M. T. (2009). Scientific research in Business Administration. Statistical Publishing.

- Nguyen Viet, B., & Nguyen Anh, T. (2021). The role of selected marketing mix elements in consumer based brand equity creation: milk industry in Vietnam. Journal of Food Products Marketing, 27(2), 72–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/10454446.2021.1892007

- Nielsen. (2017). The Corporate Sustainability Report_ 2017. https://www.nielsen.com/vn/vi/insights/report/2017/nielsen-csr-2017/#.

- Oliveira, M. O. R., Silveira, C. S., & Luce, F. B. (2015). Brand equity estimation model. Journal of Business Research, 68(12), 2560–2568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.06.025

- Pappu, R., Quester, P. G., & Cooksey, R. W. (2005). Consumer-based brand equity: improving the measurement – empirical evidence. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 14(3), 143–154. https://doi.org/10.1108/10610420510601012

- Phils, J. A., Jr., Deiglmeier, K., & Miller, D. T. (2008). Rediscovering social innovation. Stanford Social Innovation Review,6(4), 34–43.

- Power, J., Whelan, S., & Davies, G. (2008). The attractiveness and connectedness of ruthless brands: the role of trust. European Journal of Marketing, 42(5/6), 586–602. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560810862525

- Rajh, E., & Ozretić Došen, Đ. (2009). The effect of marketing mix elements on service brand equity. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 22(4), 69–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2009.11517392

- Ramos, A. F. V., & Franco, M. J. S. (2005). The impact of marketing communication and price promotion on equity brand. Journal of Brand Management, 12(6), 431–444.

- Saydan, R. (2013). Relationship between Country of Origin Image and Brand Equity: An Empirical Evidence in England Market. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 4(3), 78–88.

- Schumacker, R. E., & Lomax, R. G. (2004). A beginner’s guide to structural equation modeling. Psychology Press.

- Sen, S., & Bhattacharya, C. B. (2001). Does doing good always lead to doing better? Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility. Journal of Marketing Research, 38(2), 225–243. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.38.2.225.18838

- Shariq, M. (2018). A study of brand equity and marketing mix constructs scales invariance in UAE. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, 8(4), 286–296.

- Shimp, T. A. (1997). Advertising, promotion and supplemental aspects of integrated marketing communications (4th ed.). Dryden.

- Shocker, A. D., & Weitz, B. (1988). A perspective in brand equity principle and issues. Vol. Report: 88–104. MSI (Ed.).

- Simon, C. J., & Sullivan, M. W. (1993). The measurement and determinants of brand equity: a financial approach. Marketing Science, 12(1), 28–52. https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.12.1.28

- Slotegraaf, R. J., & Pauwels, K. (2006). Growing small brands: does a brand’s equity and growth potential affects its long- term productivity?. Marketing Science Institute Working Paper Series., 06–004, MSI, 43-66.

- Srinivasan, V., Park, C. S., & Chang, D. R. (2005). An approach to the measurement, analysis, and prediction of brand equity and its sources. Management Science, 51(9), 1433–1448. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1050.0405

- Su, J., & Tong, X. (2015). Brand personality and brand equity: evidence from the sportwear industry. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 24(2), 124–133. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-01-2014-0482

- Thanh, T. L., Huan, N. Q., & Hong, T. T. T. (2021). Effects of corporate social responsibility on SMEs’ performance in emerging market. Cogent Business & Management, 8(1) https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2021.1878978

- Tong, X., & Hawley, J. M. (2009a). Creating brand equity in the Chinese clothing market: The effect of selected marketing activities on brand equity dimensions. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 13(4), 566–581. https://doi.org/10.1108/13612020910991411

- Tong, X., & Hawley, J. M. (2009b). Measuring customer – based brand equity: Empirical evidence from the sportswear market in china. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 18(4), 262–271. https://doi.org/10.1108/10610420910972783

- Truong, V. D., & Hall, C. M. (2016). Corporate social marketing in tourism: To sleep or not to sleep with the enemy? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(7), 884–902. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2016.1201093

- Truong, V. D., & Hall, C. M. (2013). Social marketing and tourism: What is the evidence? Social Marketing Quarterly, 19(2), 110–135. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524500413484452

- Vázquez, R., del Río, A. B., & Iglesias, V. (2002). Consumer-based brand equity: Development and validation of a measurement instrument. Journal of Marketing Management, 18(1-2), 27–48. https://doi.org/10.1362/0267257022775882

- Vietnam, F. (2022). https://forbes.vn/25-thuong-hieu-cong-ty-fb-dan-dau/>

- VIRAC. (2019). Vietnam Industry Research And Consultancy. https://viracresearch.com/industry/dairy-industry-comprehensive-report-q4-2018/.

- VIRAC. (2020). Vietnam Industry Research And Consultancy. https://viracresearch.com/industry/vietnam-dairy-industry-comprehensive-report-q4-2019/.

- Vo, T. Q., & Le, V. P. (2016). Consumers’ perception towards corporate social responsibility and repurchase intention. Industrial Engineering and Management Systems, 15(2), 174–181.

- Washburn, J. H., & Plank, R. E. (2002). Measuring brand equity: An evaluation of a consumer-based brand equity scale. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 10(1), 46–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/10696679.2002.11501909

- Wheale, P., & Hinton, D. (2007). Ethical consumers in search of markets. Business Strategy and the Environment, 16(4), 302–315. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.484

- Yannopoulou, N., Koronis, E., & Elliott, R. (2011). Media amplification of a brand crisis and its effects on brand trust. Journal of Marketing Management, 27(5-6), 530–546. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2010.498141

- Yoo, B., Donthu, N., & Lee, S. (2000). An examination of selected marketing mix elements and brand equity. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28(2), 195–211. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070300282002

- Young, W., Hwang, K., McDonald, S., & Oates, C. J. (2010). Sustainable consumption: green consumer behaviour when purchasing products. Sustainable Development, 18(1), 20–31. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.394

- Zeithaml, V. A. (1988). Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: a means-end model and synthesis of evidence. Journal of Marketing, 52(3), 2–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224298805200302