Abstract

Over the vast list to resolve, the Indonesian banking sector has proven its capabilities to strive and succeed in post-crisis existence. Since it indicates continuous organizational agility, this study proposes redefining strategic management practices through literature exploration and semi-structured interviews to sustain organizational agility. To confirm the valuable insights provided by the literature, interviews were conducted with five bank practitioners and a representative of the regulator who possesses relevant expertise and experience in the topic area, providing the nuance of the relevance of conceptualizing continuous organizational agility in the factual banking sector. The results highlight the importance of cultivating agility across entrepreneurial leadership, digital culture, and capability, arguing for using routine dynamics for stability and change while dynamic capabilities for efficient organizational agility. The proposed model aims to provide an initial attempt to stimulate discussion and further investigation on this subject that empowers bank practitioners to maintain organizational agility continuously and recognize the need for future studies to enhance understanding in an area that has gained significant interest in recent years due to rapid environmental changes.

Introduction

In the face of fast change and an uncertain atmosphere, many firms battle, adapt and reorient their strategic objectives, market goals, and workforce. This might fundamentally reshape the business landscape, with specific industries and organizations thriving in the new digital environment and others struggling (Jovanović-Milenković et al., Citation2020). Leading businesses have learned that change is constant and rushed for transformation. It is crucial to understand that being agile, which blends both adaptability and resilience (Liu et al., Citation2023), can determine whether organizations thrive or struggle in this constantly evolving landscape. Relevant to the phenomenon, recent studies indicate that organizational agility promotes organizational crisis preparedness (El Idrissi et al., Citation2023), survival strategies (Rahman et al., Citation2022), and sustainability (Tufan & Mert, Citation2023). However, scaling up for agility is still challenging since it concerns business models in strategy, managing changes, leaders, and architecture (Holbeche, Citation2019). Organizations must redefine their strategic management to achieve organizational agility (Meinhardt et al., Citation2018).

The financial service sector, led by banks, plays a crucial role in boosting the economy and stabilizing the industry. Banks’ success in strategic decision-making is closely tied to their response to government policies in the highly regulated industry. As Indonesia is an emerging market and economy (IMF, Citation2023) characterized by rapidly changing economic, technological, and social conditions (The World Bank, Citation2022), stakeholders’ expectations of the Indonesian Bank’s future role have also risen. Moreover, Indonesia’s bank was a close-knit club of bureaucratic institutions despite being highly advanced and networked relative to other middle-income countries outside of the industrial wake of globalization. Indonesia’s banks will confront various hurdles in the next ten years, while at the same time, the sector must comply with all increasing laws and regulations (Tan et al., Citation2020). The Indonesian Financial Services Authority (OJK) serves as the governmental representative for the Indonesia Bank and prioritizes the Financial Service Sector’s resilience and competitiveness across digitalization and innovation (Indonesia Financial Services Authority [OJK], Citation2020). Organizational agility is a critical factor for a thriving Bank, as it allows banks to encourage flexibility to comply with changing rules and take advantage of financial industry opportunities, assisting Banks in improving economic resilience through swift adjustments like revolutionary digital banking acceleration (OJK, Citation2021).

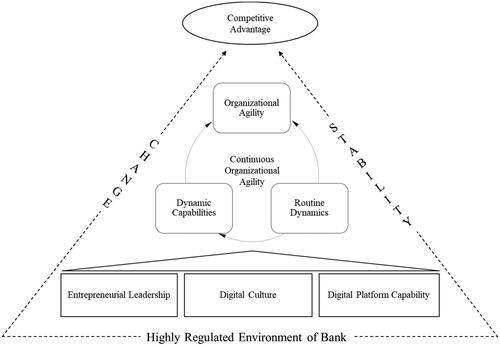

While some perceive highly regulated sector legacy systems as rigid and difficult to update, resulting in a lack of agility, this study shows that these standardized systems, in fact, contribute to stability, making continuous agility. As Wouter et al. (Citation2015) stated, ‘Agility should rhyme with stability’, this highlights making banks relevant to the context. Organizations must balance company consistency and stability with flexibility and change to sustain agility (Lindskog & Netz, Citation2021; Prange, Citation2021). Tallon et al. (Citation2019) also questioned how organizations achieve this balance. To elaborate, the theory of routine dynamics exists at the intersection of stability and change (Feldman & Pentland, Citation2003). Continuity through routine dynamics is a process driven by desired outcomes that endure rather than an object that stays steady and comparable (Feldman et al., Citation2022). Continuity emerges through connected steps that become pathways, adjusting patterns, and taking logical steps in response to a changing situation.

Furthermore, although agility promotes adaptability in addressing needs, short-term agility will burden the company with a costly strategy (Ajgaonkar et al., Citation2022; Teece et al., Citation2016; Werder et al., Citation2021). Complementing the focus on continuity, surviving firms tend to understand how agility and efficiency are related (Teece et al., Citation2016). Adopting a dynamic capability approach to their business strategy will allow organizations to stay current by quickly accessing and accurately reconfiguring the most recent information (Medeiros & Maçada, Citation2022). Dynamic capability also helps the company decide the right time to implement organizational agility, thus optimizing the efficiency-organizational agility trade-off (Teece et al., Citation2016). The need for speed is not temporary, and the forces of change will continue accelerating. Given the advantages of organizational agility, it is necessary to consider strategies to foster agility while simultaneously considering how to maintain it efficiently for a long time.

Research on continuous organizational agility is limited (Gölgeci et al., Citation2019), with few studies addressing its importance and feasibility. Prior studies tend to overlook the significance of routine dynamics in achieving a balance between stability and change within agile organizations (Crick & Chew, Citation2020). Also, the existing literature often fails to consider the specific context of highly regulated banks (Aburub, Citation2015), as most studies focus on agility in the manufacturing industry (Tanushree et al., Citation2023). Therefore, a comprehensive investigation is necessary to identify and clarify the key factors and relationships that influence continuous organizational agility (Gölgeci et al., Citation2019). Knowing that fundamental organizational elements such as leadership, culture, and technological advancement are common in predicting organizational agility (Arunprasad et al., Citation2022; Franco et al., Citation2022) requires scholars to bring fresh discussion on their microelements, specifically in response to the unavoidable digital environment. In such a scenario, the organization already has a source of competitive advantage that arises equally from what it does (routines) and what it owns (elements), as defined by Charan and Willigan (Citation2020).

Empirical evidence is needed to establish the integrated routine dynamics, dynamic capabilities, and organizational agility relationships, which still need to be found, mainly to build continuity concepts. By focusing on this context, this study aims to fill the gaps in understanding how the regulatory environment affects and shapes continuous organizational agility within the Indonesian banking sector. Addressing these research gaps will advance the knowledge and understanding of organizational agility, providing valuable insights for academia and practitioners.

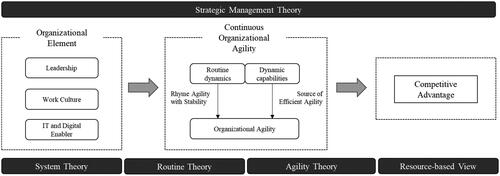

Theoretical basis

This research is motivated by the interaction of some critical theories under strategic management theory, which have evolved into other theoretical specifications over the decades. The resource-based view is believed to be the source of dynamic capabilities (Eisenhardt & Martin, Citation2000) and a sustainable competitive advantage (Barney, Citation1991). Organizational agility is one of the consequences of the contingency theory (Darvishmotevali et al., Citation2020; Mao et al., Citation2021), which requires a business to be more adaptive to the environment. Rooted in the theory of the firm, system and modern organization theory contribute to organizational elements and routine variables. Ultimately, these well-known theories are supposed to manage resources to gain a competitive advantage optimally.

Based on system theory, management views organizations as dynamic systems of interrelated elements (Siggelkow, Citation2002) that use routines as temporal structures to achieve goals (Feldman & Pentland, Citation2003). In 2022, Feldman et al. (Citation2022) embraced the concept of patterning in routine dynamics to promote continuity. This field examines how organizational members restore and extend action patterns from daily demands to corporate strategy adjustment (Mirc et al., Citation2023). Simple understanding, Weick (1979, Citation1995) said organizations are founded on interrelated actions, not people, making his contingency approach differ from conventional theories. Langley et al. (Citation2013) and Hernes (Citation2014) also used this perspective to define process theory continuity. attempts to illustrate the continuous construction of continuous organizational agility.

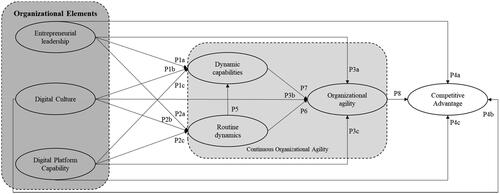

Derived from the foundation of an organization are its people, practices, and technologies (Crick & Chew, Citation2020), that is also mentioned in the blueprint for the digital transformation of Indonesian banking (OJK, Citation2021); this study combines leadership, organizational culture, and technological enabler, as the top three most often mentioned in agility literature (Arunprasad et al., Citation2022; Franco et al., Citation2022). From these macro-organizational elements, further literature investigation is made to find the specifically suitable sub-elements of Banking. The interaction between variables should lead to a competitive advantage.

Regarding leadership, it is worth noting that transactional leadership and contingency leadership have been found to have connections with firm values. Transactional leadership involves exchanging rewards for achieving goals, while contingency leadership focuses on adapting leadership styles to fit specific situations, which could offer valuable insights, yet only a dearth of agility studies highlights their importance on organizational agility. Transformational (Golgeci et al., Citation2020), Adaptive (Susanty et al., Citation2022), and Entrepreneurial Leadership (Teece, Citation2016) are some of the types mentioned in organizational agility research. Although analytically separable, a strong correlation exists between entrepreneurial and transformational leadership (Renko et al., Citation2015); their goals and traits may overlap in one person and can be beneficially blended (Teece, Citation2016). Entrepreneurial leaders will likely have the vision, creativity, and risk-taking mentality necessary to drive organizational agility, thus, may assist banks in improving market and brand orientation, innovativeness, and performance (Djalil et al., Citation2023) by supporting the performative aspects of routine dynamics (Parmentier-Cajaiba et al., Citation2021).

However, agile companies require a digital-embracing culture to facilitate change, promoting innovation and digital transformation while developing essential capabilities (Troise et al., Citation2023) to successfully utilize packaged digital capabilities, platform orchestration, and data utilization. Especially for non-digitally native companies that face challenges in establishing digital assets, resources, channels, records data, and integrating processes that enable agility (Li & Chan, Citation2019). Historically, banks have shown a lack of organizational agility in reacting to such changes, leading to a rising perception that banks may become obsolete while digital banking functions are required (Gomber et al., Citation2018). Digital culture in banks can make firms more flexible by helping them respond swiftly to market and business innovations (Campanella et al., Citation2020). It can help banks build a culture of experimentation and innovation, which can help them stay ahead of the competition.

The need for digital elements was highlighted in agility literature in the last three years. Most importantly, Liu et al. (Citation2023) and Troise et al. (Citation2022, Citation2023), referring to Ravichandran (Citation2018), revealed the positive influence of digital platform capability, which facilitates organizations with IT infrastructure flexibility and the span of digital applications that can be implemented to promote agility in the current digital challenge. New technologies provide business advantages since firms may produce IT-based business innovations cheaper than their rivals by adopting flexible IT infrastructures and digitizing business processes. Lee et al. (Citation2016) suggest that an excellent IT infrastructure enables an organization to add new capabilities swiftly and cost-effectively by offering established technical specifications and interfaces. summarizes the macro and micro elements relevant to agility in the banking sector.

Table 1. Organizational element extended variables.

Despite what has been mentioned in organizational agility literature, entrepreneurial leadership, digital culture, and digital platform capability characteristics represent their importance for promoting banks’ organizational agility. Entrepreneurial leadership encourages manageable risk-taking and creative problem-solving, leading to new products and services that generate additional revenue streams and create competitive advantages (Djalil et al., Citation2023). The trend toward digitalization is set to continue (Selimović et al., Citation2021), with the emergence of open banking, blockchain, and artificial intelligence driving new opportunities for financial services (Das et al., Citation2018). Umans et al. (Citation2018) introduced a new method of operationalizing digitalization in banks through organizational culture. A digital culture fosters learning agility in Indonesian commercial banks (Setiadi et al., Citation2022), resulting in enhanced work efficiency, increased accessibility, fostered innovation and flexibility, and broadened business networks and coverage. Finally, the digital banking transformation plan (OJK, Citation2021) raises the Banks’ need for IT infrastructure flexibility and a range of digital platform implementation; digital platform capabilities address this issue.

From organizational agility to continuous organizational agility

The organization is dedicated to establishing and extending a new agile architecture across the organization, where agility should be harmonized throughout organizational elements. Since then, organizations should further analyze the best combination of organizational elements supporting the conceptualization concerning continuous organizational agility. Routine dynamics serve as a foundation for both stability and change, whereas dynamic capabilities are essential for achieving efficient organizational agility.

This understanding is essential for maintaining continuity. Creating value together through a set of organizational activities provides the foundation for how an organization behaves in repeated actions crucial to any company’s smooth operation. Strong businesses balance various dimensions of agility to ensure both changes and stability (Prange, Citation2021). Identifying the core agility of organizational elements, well-established routines, and the ability to capitalize on dynamic capabilities will help to ensure that agility can be maintained over time. Organizations should track the performance of the patterns and activities over time to identify any areas for improvement or opportunities for further optimization and regularly review and refine the patterns and activities to ensure they remain aligned with the organization’s goals and objectives.

This aligns with Worley and Pillans (Citation2019), who suggest that the more likely it is to accept change as routine, the more agile an organization is. Adopting agile approaches does not solely build organizational agility, dynamic change efforts should be interwoven into typical workdays rather than being designed as unusual activities.

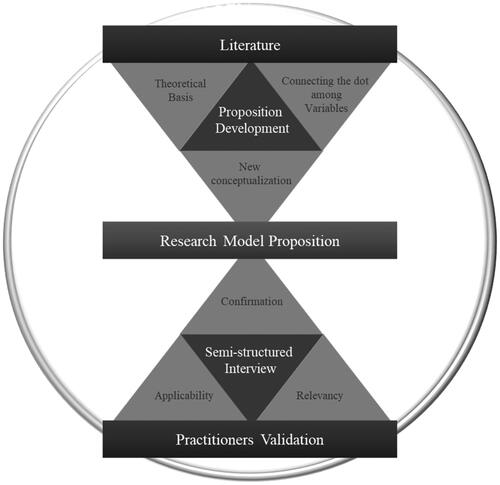

Method

This study employed a qualitative, theory-building research approach in response to existing (Zorzini et al., Citation2015). The framework development was derived from a structured model outlining continuous organizational agility dimensions. It incorporates some crucial theories and is further validated by practitioners regarding its applicability to industry practice. A literature search was conducted to identify relevant research on the linkages among the variables investigated and formed the basis for developing the conceptual model. Empirical data was collected via semi-structured interviews with six Bank practitioners. The objective was to gather literature-based and practitioner points of view to support the argument, practice, and evaluation of benefits related to continuous agility. The heuristic model is supported by a set of propositions derived from the discussed theory and concepts. shows a research design consisting of multiple phases of this study.

Following the literature review, practitioners’ interviews have been done to confirm the construct and relationship proposed in the research model. The interviewer asked semi-structured questions in a drive to confirm the use of variables to support agility continuity. The interviewer followed the interviewees attentively and asked questions most relevant to where the conversation was headed (Charmaz, Citation2014). Thematic analysis (Miles et al., Citation2019) helped identify recurrent topics within qualitative data. Once novel, meaningful findings were no longer available, data gathering for each case stopped (Yin, Citation2017). A minimum department head position from five large national banks with many branches nationwide was interviewed. Interviewing large companies that covered various markets ensured that business dynamics (Loebbecke & Picot, Citation2015) were present. Also, the government representative (OJK) was invited to the interview to give the regulator perspective on the research model. Therefore, this interview is expected to validate the construct and relationship required to improve the continuous conceptualization based on its applicability to Indonesian banking practice. describes the interviewees’ profile and work background.

Table 2. Interviewee for proposed model validation.

All 45- to 60-minute interviews were transcribed. The interview consisted of a phone call and an in-person meeting in Bahasa (Indonesian language). During the initial phase, the researchers analyzed the interview manuscripts and separately selected quotes that described the highlights of the factual banking phenomenon. The results were subsequently analyzed and compared by the researchers. The second phase of the analysis involved applying the concept of analytical induction to develop conclusions about the validated propositions (Yin, Citation2017). The quotes were translated before being categorized based on potential connections between issues and other factors. The quotation refers to the verbatim document with the format of ‘(Filename/page/line number)’. A combination of selection criteria and a detailed multi-step process were employed to reduce the impact of social desirability bias and ensure the correctness of the interpretations derived from the data. Nevertheless, the presence of biases, such as interviewer and response bias, is unavoidable due to the various ways of articulating interviewees’ nonverbal cues and different approaches to conducting interviews (by phone and face-to-face interactions), regardless of their minimum probability.

Proposed model development

Since there is no perfectly fit dynamic and situational organizational agility solution, the business is dedicated to implementing and scaling the new agile structure across the enterprise (Werder et al., Citation2021), where the ability to be agile must be developed under the functioning organizational elements in the specific business context. For the Bank, growing literature promotes the uniqueness of entrepreneurial leadership (Dabić et al., Citation2021), the importance of digital culture (Grover, Citation2022), and the unavoidable existence of digital platform capability (Troise et al., Citation2023). Collaborating effectively can create dynamism in routine (Crick & Chew, Citation2020) and capabilities (Bitencourt et al., Citation2020). This enables the organization to continuously respond to challenges and uncertainty using an established internal system. The notion of organizations as systems makes organizational agility implementation necessitates the integration of numerous organizational elements (Baloch et al., Citation2018; Jafari-Sadeghi et al., Citation2022; Walter, Citation2021) to be embedded into daily activities and achieve continuity. In the end, Banks must react rapidly to several disruptive trends and unforeseen risks in the coming years (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., Citation2021) and be agile to stay agile ahead in a competitive climate (Sumiyana and Hanani, Citation2021). visualizes the conceptualization.

The main objective of a practitioner interview is to recheck or reconfirm the construct, relationship, and conceptualization found in the literature review to finalize the research model built on the propositions. All interviewees agreed that banks must be more agile after digitalization, especially when dealing with a pandemic. In the new normal, most of the large banks in Indonesia are starting to offer two ways of working. The employee can have flexible hours at a nearby workplace. Regulators and banks collaborate as service partners. With the current structure and design of the company, cross-collaboration and communication between divisions are more common, especially when formulating strategies when new regulations are issued. The organization becomes adaptive and quick to respond through various perspectives, determining the risk level to provide the best service for customers and stakeholders.

Entrepreneurial leadership and dynamic capabilities

Despite the lack of literature on the micro-process of how leaders might foster dynamic talents, many studies have shown a positive association between entrepreneurial leadership and dynamic capabilities (Nguyen et al., Citation2021). Top management’s entrepreneurial and leadership skills around sensing, seizing, and transforming are required to sustain dynamic capabilities (Teece, Citation2012). Entrepreneurial management involves identifying business opportunities, integrating resources to pursue new innovative paths, and planning to optimize the organization and its business model, which are crucial to the firm’s dynamic capabilities and organized across the organization (Teece, Citation2016) and is a necessary supplement for strong dynamic capabilities (Schoemaker et al., Citation2018).

Interviewees practically encounter similar business challenges when adapting their operations to address uncertainty within highly regulated environments. Simultaneously, it is imperative for them to seize any opportunities that arise amidst difficulties. Leaders must possess creativity and a willingness to take risks to navigate market acquisitions and comply with increasing regulations, as expressed by the statement of the first practitioner.

As previously mentioned, the leaders within this organization are experiencing fatigue (chuckles), and optimizing the risk appetite is imperative to enhance customer benefits. We passionately measure this aspect to dynamically adjust the operational approach, which naturally necessitates a high degree of creativity. (PCT/2/35-37)

Practitioners two and three add that commonly well-established banks already have a system for capturing the external change to seize and transform into action promoting performance (MIT/5/23-39). Entrepreneurial leadership indeed has the capacity to encourage effort. In this way, entrepreneurial leadership contributes to dynamic capabilities through the following proposition:

P1a. With their uniqueness, entrepreneurial leadership significantly impacts the Bank’s sense, seize, and reconfigure capability.

Entrepreneurial leadership and routine dynamic

Glaser (Citation2017) develops a theoretical model explaining how people in organizations use a continuous redesign to create a performance that affects routine dynamics. In an entrepreneurial setting, employees must be flexible in their routines and able to change them as needed (Dittrich & Seidl, Citation2018). Lack of entrepreneurial vision and leader dependence make operational and resource procurement decisions unclear. Parmentier-Cajaiba et al. (Citation2021) provide empirical data from a paradigm conflict analysis of entrepreneurial behaviors that lead to a new routine. They analyzed entrepreneurial processes related to classic and modern heuristics and helped explain the essential aspects that encourage creating and validating the new routine. The primary argument here is that semi-continuous asset orchestration and renewal, which includes the redesign of routines, cannot be attained without senior management’s entrepreneurial and leadership skills (Teece, Citation2012).

While the third practitioner highlights how entrepreneurial leaders are regarded as esteemed figures, particularly among the current generation dominating the job market that perceives a lack of hierarchical barriers and is enthusiastic about interacting with peers rather than engaging in bureaucratic processes (MIT/3/19-22), this viewpoint was not generally accepted. This character trait appears to manifest at an operational level, as Practitioner 1 emphasized that entrepreneurial approaches in the banking industry need to be adjusted to align with regulatory constraints.

BCA members seem to have always been enterprising. However, if the OJK sets constraints, we must find ways to maximize consumer advantages while complying with regulations. The leader holds the direction. (PCT/2/33-34)

Furthermore, entrepreneurial leaders, characterized by their creativity and willingness to take risks, support the Second Bank to thrive in highly regulated environments. This is especially true in branch units, where their ability to identify and capitalize on market gaps leads to enhanced performance and market expansion (MIT/3/24-26). These are summarized in the following proposition:

P2a. Knowing they have creative ideas and the courage to take risks, entrepreneurial leaders will have a way to improvise in performing work while complying with the written standard of the routine.

Entrepreneurial leadership and organizational agility

Through their empirical research in the context of social enterprise, Jan and Maulida (Citation2022) and Sari and Ahmad (Citation2022) proved that entrepreneurial leadership positively impacts agility. The relevance of competent entrepreneurial management is critical when there is a greater need to achieve organizational agility to make appropriate decisions in severe uncertainty (Teece et al., Citation2016). Entrepreneurial leadership’s traits—innovativeness, proactiveness, competitive aggressiveness, and risk-taking—improve organizational agility (Dabić et al., Citation2021), and especially for the highly regulated sector, entrepreneurial leadership helps banks to be agile while complying with regulations. Moreover, Fontana and Musa (Citation2017) and Utoyo et al. (Citation2020) also provide empirical evidence that entrepreneurial leadership encourages innovation processes and performance to keep an organization agile and adaptable in a disruptive environment. Others discovered that entrepreneurial leadership is critical for organization-level strategic agility analysis (Sari & Ahmad, Citation2022).

The first bank promptly convenes a collaborative meeting to assess and establish necessary adjustments in response to regulatory changes. An entrepreneurial leader with a high-risk tolerance strives to optimize customer benefits through implemented changes. Through his creative prowess, he adeptly adapts and devises novel approaches to optimize productivity, effectively capitalizing on all available opportunities despite inherent constraints.

In such cases, the leader must increase our risk tolerance to assess it carefully. This will improve our agility, requiring a creative attitude. (PCT/2/38-39)

However, the perspective of practitioners from the regulatory body (OJK) presented a different viewpoint on the situation. She revealed that principle-based regulations allow banks with entrepreneurial leaders to improvise and be more agile in responding to regulatory changes (MIT/4/17-20) yet did not explicitly suggest the level of flexibility implied. This implies the importance of an entrepreneurial leader who can creatively interpret and navigate regulatory boundaries, allowing for a level of improvisation. Expanding on the findings, this research sets the following proposition:

P3a. In a growing regulation, entrepreneurial leadership has the capability to adjust operations and capitalize on the market quickly in response to business change.

Entrepreneurial leadership and competitive advantage

Previous research has confirmed the relationship between leadership styles and organizational competitive advantage (Lapshun & Fusch, Citation2023). In another search for empirical evidence, Jan and Maulida (Citation2022) and Nguyen et al. (Citation2021) found that entrepreneurial leadership directly impacts competitive advantage in different contexts. Entrepreneurial leaders seek new opportunities and build the methods and abilities to explore them. Inspiring their colleagues to think outside the box, take the initiative, and bring a unique viewpoint and deep consumer understanding, enabling more creative, customer-focused solutions. Niemand et al. (Citation2021) found that entrepreneurial approaches and strategies help German, Swiss, and Liechtenstein banks perform successfully.

The first practitioner contends that the present challenge lies in sustaining a competitive stance, enhancing capabilities, and aligning with the evolving trends observed in other banks (PCT/4/19-22). It is imperative to preserve existing infrastructure while adapting to external transformations. Ultimately, entrepreneurial leadership ultimately confers a competitive advantage, fostering creativity, innovation, and agility.

Entrepreneurial leaders are known for their innate ability to think creatively and take calculated risks. … These individuals possess a unique skill set that enables them to enhance their performance by identifying and capitalizing on untapped opportunities for market expansion. (MIT/3/24-26)

A leader will contribute through their leadership style. According to Ximenes et al. (Citation2019), entrepreneurial leadership strengthens the relationship between high-performance work systems, employee innovation, and performance. In the end, this would affect the company’s competitiveness under high regulation. The following proposition will confirm this relationship:

P4a. Entrepreneurial leaders encourage changes and create competitiveness.

Digital cultures and dynamic capabilities

Organizational culture is crucial in digitalization (Chernyavskaya et al., Citation2021; Grover et al., Citation2022; Wang et al., Citation2022) and, at the same time, is the antecedent of dynamic capabilities (Shuaib et al., Citation2021). Fostering a digital culture may be linked to management control, specifically performance management, which highlights the importance of organizations adapting to dynamic external and internal environments through modifications to their values, attitudes, and structures (Batko et al., Citation2018). Organizations with a common language for digitalization can overcome certain cognitive biases that hinder their ability to respond effectively to disruptions (Gomber et al., Citation2018; Karimi & Walter, Citation2015). Establishing a digital mindset and culture across the organization is crucial in developing sensing capabilities that enable incumbents to capitalize on emerging trends (Warner & Wäger, Citation2019). A digital culture provides the motivation and energy to explore new ideas and opportunities; therefore, it will support dynamic capabilities, enabling the organization to capitalize on those ideas and optimize them.

For some interviewees (practitioners 2, 5, and 6), the organizational culture topic is their expertise. Concerning dynamic capabilities’ sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring, the sixth practitioner explicitly tells the following statement:

Digital culture has become a big part of our organization, especially with everything going on with Covid-19. It has become ingrained in how we do business and run things. So basically, implementing it helps us adapt and deal with changes while also making it easier for us to work in new ways. (TBNI/1/17-20)

P1b. The internalization process of digital culture helps the company to successfully sense, seize, and reconfigure the rapid digital change.

Digital cultures and routine dynamic

The routine’s components were formed by familiar cultural approaches as several studies show that cultural impacts on people’s behavior during daily chores often deviate from idealized patterns and thus improve workplace flexibility (Bertels et al., Citation2016). Routine dynamics must be able to adapt to shifting situations and requirements; hence, they must be built to do so. Culture is considered a unifying force that enables effective control, manipulation, and optimal organizational performance through increased uniformity.

Kitsios et al. (Citation2021) noted the multiplying effect of company culture on managing digital transformation in the banking sector on how employees will incorporate digitalization into their daily work practices. In the disrupted business world where digital tools are mandatory, empirical research has demonstrated that digital culture benefits individuals’ cognitive processes, specifically in their ability to conceptualize and incorporate technology advantages into their routine practices and integrate it into daily activities to create profit (Martínez-Caro et al., Citation2020). Thus, a firm’s technological orientation embedded in culture may encourage innovative thinking and show workers that their ideas are valued and, in turn, can facilitate a culture of sustained creativity and change to promote routine dynamics.

However, organizational culture becomes ingrained and integrated into daily work practices. The implementation of digital culture aims to support adopting digital work practices. In this regard, the sixth bank provides employee-friendly application software, hardware, co-working space, digital training, and conferences. These resources are designed to facilitate the practical aspects of digital routines (TBNI/1/25/31-TBNI/2/1-11). The fifth practitioner agrees and says:

In our case, (through digital culture) we create a pattern of running operations using digital resources to optimize work results. (TMDR/1/13-15)

P2b: Digital culture facilitates particular acts and may affect the formation or repression involving new activity patterns in routine dynamics.

Digital cultures and organizational agility

Some key literature on organizational agility development involves corporate culture (Carvalho et al., Citation2021; Felipe et al., Citation2017; Nink, Citation2019) as well as how digitalization impacts organizational agility (Levallet & Chan, Citation2022; Pinsonneault & Choi, Citation2022; Škare & Soriano, Citation2021) including in the context of the financial service sector (Pourmohammad et al., Citation2016; Shaikh et al., Citation2017). A digital culture covers the values and ideas that inspire businesses to engage in digital innovation (Grover, Citation2022; Wang et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, it promotes creativity, receptivity to new ideas, and decision-making flexibility (Martínez-Caro et al., Citation2020). Digital culture is required to respond to digitalization and create a digital mindset, which is still challenging for businesses (Merkt et al., Citation2021).

The new normal business condition no longer separates banking core business and digital implementation. As the third practitioner expressed:

Yeah, digitalization has definitely made a big impact after COVID, hasn’t it? Now we have more flexibility with our working hours and the option to work remotely, which is pretty cool, right? (MIT/3/13-15)

P3b. With the benefit of digital culture, the bank will promote organizational agility.

Digital cultures and competitive advantage

Despite an increasing number of empirical studies examining the link between digital culture and performance (Hadi & Baskaran, Citation2021; Pangarso et al., Citation2022; Pradana et al., Citation2022), it is undeniable that digital culture plays a crucial role in a firm’s competitive advantage (Grover et al., Citation2022). Porter (Citation1985) initiated the idea of how technology promotes competitiveness. However, developing competitive advantage entails possessing resources and capabilities that enable an organization to produce superior products and offer exceptional value to customers relative to its competitors, fueled by institutionalizing a digital mindset and behavior through organizational culture (Grover et al., Citation2022). A series of literature has investigated and revealed that organizational culture impacts competitive advantage directly and through the mediating role of innovation (Azeem et al., Citation2021), ambidexterity (Ramdan et al., Citation2022), but still lacks attention to specific digital culture impact on competitive advantage.

The first practitioner believes that, in the end, the digital investment should be paid off by the benefit (PCT/3/17-18). The internalization of digital culture fosters worker creativity in digital innovation, increasing productivity with the optimum utilization of digital resources and finally leading to cost leadership compared to competitors. The second practitioner statement validates this:

.companies must internalize digitalization in every business process that has been running to cut costs, time, and increase productivity. (TBRI/1/20-23)

While Suraji (Citation2022) provided a shred of empirical evidence that showed the direct significant impact of digital culture on MSME’s competitiveness, additional evidence also showed the impact of digital transformation (Shehadeh et al., Citation2023) and technological orientation (Yang et al., Citation2022) on competitive advantage. Considering they were a product of digital culture (Chernyavskaya et al., Citation2021; Wang et al., Citation2022), the proposition is formulated:

P4b. Digital culture creates a mindset and behavior to catch up with the digital business world that will help the Bank win the market competition.

Digital platform capability and dynamic capabilities

Digital technology enables innovative services and transformation; thus, enterprises are improving their product cycle (Ranta et al., Citation2021). Using digital platforms allows companies to promptly identify alterations in the surrounding context and promptly adapt to evolving customer demands and heightened processing capacities at a reduced cost. The ability to respond quickly and make sound decisions relies on a solid foundation of information (Sedera et al., Citation2016). Constantiou and Kallinikos (Citation2015) believed that the capabilities of digital platforms could facilitate the development of dynamic capabilities since these platforms provide access to digital information and collective wisdom, which includes the experience, opinions, and knowledge of members within digital platform ecosystems.

All interviewees concur that the utilization of digital technology predominantly drives contemporary banking practices. Machine learning is employed to analyze credit card transaction records and gain insights into customer lifestyles. This information aids the promotion division in making informed decisions regarding allocating resources to the most effective promotional items. Also, the product development division used the data to attract potential customers to build the most up-to-date and suitable innovations. One of their statements is quoted below.

…. especially in the credit department, algorithms are now employed to gain insights into customer requirements, enabling accurate targeting and effective expansion and promotional strategies. (PCT/2/14-16)

Banks get more accessible to sense, seize, and transform customer demand into their service with the existing digital platform capabilities. When it comes to regulatory concerns, despite supporting the idea, they consistently warning that Banks should balance digital banking innovation and prudential aspects to maintain prudent, safe, sound performance and public trust in banks’ digital services (MIT/3/4-5). Among the absence of empirical evidence of this relationship, Xiao et al. (Citation2020) found that digital platform capabilities directly and positively affect dynamic capabilities, indicating that it might be a new antecedent to dynamic capabilities:

P1c. Banks will gain better dynamic capabilities with IT infrastructure flexibility and a wide span of digital platform implementation.

Digital platform capability and routine dynamic

Volberda et al. (Citation2021) propose a framework for devising strategies in the contemporary digital competitive environment that highlights the significance of the interplay among three factors, one of which is the requirement to restructure and expand digital routines. Digital platform capability covers the IT infrastructure flexibility and the digital platform scope, including the firm’s digital technology adoption, such as big data analytics, Blockchain, Cloud computing, IoT, Business Intelligence, Artificial Intelligence, etc. (Troise et al., Citation2022). Specific co-production methods are needed to adapt technological solutions to the dynamics of other organizations’ routines before they can be transferred, replicated, or adopted. For example, the co-creation of technological solutions utilizing artificial intelligence is situated within specific actions and integrated into a cognitive distribution system, resulting in automated and enhanced routine processes (Lepratte & Yoguel, Citation2023).

To understand routine dynamics, studies must include elements outside the routine (Wegener & Glaser, Citation2021). Digital platform capabilities exist to support the operational routine. In the implementation, IT infrastructure flexibility and the number of digital platforms used will define daily work’s speed, efficiency, and accuracy, including the standard and performance.

In general, everyone is using the system now; they are leaving manual work… (PCT/2/9-10)

Being more specific, practitioner 3 clarify that the need of bank’s digital capability exponentially increases at the moment of Covid-19 where remote and flexible working hours are rushed to be supported (MIT/3/13-15). This is particularly relevant considering the increased reliance on digital channels for financial transactions, which has become the primary mode of payment in communities during the pandemic-induced shift towards a cashless culture. Adding to the debates, digital platform capability is argued to have a positive relationship with Banks’ routine dynamics:

P2c. Since digital platform capability improves daily performance and operation, it will also improve routine dynamics.

Digital platform capability and organizational agility

Organizations can better establish, combine, and use digital platforms and technologies with higher digital platform capability since digital platform capability optimizes decision-making and business processes (Cenamor et al., Citation2019). These digital systems can detect market trends, seize possibilities, increase resource flexibility, and react quickly, allowing firms to quickly implement shift resources to capitalize on market possibilities strategically, thus improving agility (Ahmed et al., Citation2022; Ravichandran, Citation2018; Troise et al., Citation2022). The number of digitized processes and various process digitization applications in an organization are positively connected with digital platform capability. In this case, the ability to integrate technology into company activities is more important than their existence (Ahmed et al., Citation2022). Banks implementing machine learning, artificial intelligence, blockchain, cloud computing, IoT, and other business intelligence systems may have more digitized processes than those implementing only a subset. Digital platform capability can enhance organizational agility, facilitate resource management, and identify opportunities for improvement (Ravichandran, Citation2018).

Regulatory updates are also keeping up with the demands of digitization. The development of a blueprint for the digital transformation of Indonesian banking involves formulating a principle that embodies the concept of digital platform capability, as explained by the regulator representative during the interview.

Technology neutrality means that we do not rely on just one technology. It is all about finding a balance and sticking to safe and sound banking practices. Banks should definitely use these two principles to become more agile. (MIT/2/36-38)

Moreover, starting the pilot project to measure bank digital maturity (BRI is a participant) to legalize the measurement indicators in the third quarter of 2023 for other banks to follow (MIT/3/9-10) ensures that regulators are concerned about digitalization. This directs banks to build digital capabilities in their operations in response to rapid digitalization change. Although using different naming, the digital technologies capability used by Troise et al. (Citation2022) is referred to as Ravichandran’s (Citation2018) digital platform capability. It has been empirically proven to impact organizational agility positively and significantly. Ahmed et al. (Citation2022) also reached the same statistical result with slightly different measurements. Little more than a consequence, digital platform capability is a crucial predictor of organizational agility as well:

P3c. Digital platform capability has a direct impact on Organizational agility.

Digital platform capability and competitive advantage

Cenamor et al. (Citation2019) defined digital platform capability as an organization’s capacity to employ the most advanced digital tools and technology as competitive weapons. Improved awareness can facilitate competitive actions, enable firms to adapt to changes in their competitive environments, and promote market sustainability. The platform architecture of the digital platform capability facilitates flexible linkages and information sharing among service firms, suppliers, customers, competitors, and marketing, technical, or financial partners. This optimization enhances the quality of relationships among all parties involved (Raassens et al., Citation2022). Conceptually, the digital platform capability enables the organization to stay ahead of the competition by better understanding customer needs and meeting them swiftly and effectively.

For Indonesia to benefit from economic integration, the national Bank must increase efficiency and product and service diversity, including new technology (The World Bank, Citation2022). All the interviewees agreed, as represented by the second practitioner statement.

…Everything is almost systemized, …. the next challenge is how can also ultimately create digital products that are safe and competitive… (MIT/2/41-42)

Under the principles of digital transformation in the blueprint prepared by the OJK (Citation2021), banking implements various technologies (technology neutrality) that require IT infrastructure’s readiness in its application (MIT/3/1-3). Moreover, in a post-crisis situation, service firms, including banks, can enhance their competitiveness by creating digital platforms with versatile, compatible, and augmenting features through careful design (Liu et al., Citation2023). Adopting flexible IT infrastructure and digitizing business processes enables firms to develop IT-based business innovations at a lower cost than their competitors (Ravichandran, Citation2018; Troise et al., Citation2022). This is because of the ability to adapt systems and processes cost-effectively to accommodate changing conditions.

P4c. Digital platform capability enables banks to improve their products or services in a competitive market quickly.

Routine dynamics and dynamic capabilities

From the earliest moments, the dynamic capabilities literature has frequently involved the concept of routines. As a collaborative management approach, dynamic capabilities require new product development, quality control, and technology/knowledge transfer routines (Eisenhardt & Martin, Citation2000) and necessitate investment and commitment to higher-level change routines (Winter, Citation2003). Changing routines (e.g., new products across a specified track) and analytical procedures (e.g., spending decisions) are a complete portfolio for dynamic capabilities building (Teece, Citation2007; Wenzel et al., Citation2021). Thus, the Biesenthal et al. (Citation2019) study indicates that ostensive and performative routine aspects influence the role of dynamic capabilities in modifying operational capabilities. However, organizational capabilities result from the recollection of executing organizational routines (Miller et al., Citation2012; Worley & Pillans, Citation2019), and at this stage, splitting components between routine dynamics and dynamic capabilities may help build bridges across areas (Salvato, Citation2021).

Bank employees, particularly those in frontline roles, are encouraged to proactively propose and implement initiatives to enhance their daily work processes. Nevertheless, they often directly interact with current clients, who could be converted into prospective customers for additional banking offerings. According to the second practitioner’s experience, it was revealed that:

It is definitely possible for a teller to transition into a business feeder role for marketing. Being close to customers can really pay off, especially in branch work units. It is great when workers can think on their feet and adapt to different situations. (MIT/5/1-5)

When it comes to collaboration, we often have impromptu meetings with other divisions to tackle unexpected changes. During these meetings, we all work together to figure out how to adapt and develop new solutions. We make sure to include new team members and trust them to learn and contribute to the improvisation process…. (through their work initiatives) employees can more quickly grasp the customer’s needs, basically because they are engaged with the customer. (PCT/3/39-42 and PCT/4/1-6)

By defining the effect of routine dynamics on dynamic capabilities, dynamic capabilities scholars hope to clarify what makes organizational capabilities dynamic (Salvato, Citation2021), with the need for more empirical research conducted. The following hypotheses are proposed:

P5. Dynamic capabilities are typically influenced by consistent, recurring actions to handle highly dynamic conditions as represented by routine dynamics.

Routine dynamics and organizational agility

An ostensive routine can provide a foundation for organizational agility by providing structure and consistency. Well-defined routines can facilitate efficient communication and collaboration, allowing the organization to anticipate and respond to changes in the environment in terms of speed and efficiency (Feldman, Citation2000; Feldman & Pentland, Citation2003). Performative routines that provide adjustable actions allow the organization to remain agile in changing conditions. Organizations can increase their organizational agility and impede the inertia of routine by adjusting their ostensive routine to suit the demands of the business market better (Zhen et al., Citation2021) and optimizing performative routines with their improvisational characteristics (Rosales et al., Citation2022). Thus, routine dynamics, which constitute both the ostensive and performative parts, will support organizational agility since its superior speed and flexibility characterize it; obtaining these qualities effectively and managing change efficiently leads to maintaining continuity.

In a competitive landscape where companies possess similar capabilities, the differentiating factor lies in acting quickly and accurately. The first practitioner believed that technological advancements and systems possess the potential for replication, thereby emphasizing the significance of actors’ execution as the differentiating factor, which is the performative part of routine dynamics.

We need to make sure we take care of what we have built while keeping up with the changes happening around us. The more we get used to this, the easier it will be for us to make transformations in the future. It is like we are getting accustomed to having meetings, adapting to changes, and implementing new things. (PCT/4/20-22, 25-28)

Interaction and teamwork can be improved by clearly stated routines, which allows the organization to quickly adjust to changes in the external environment (Feldman, Citation2000; Feldman & Pentland, Citation2003). When there is consistency, repeated interpretations are produced, which assist employees in adjusting to change and produce visible patterns of flexibility; in turn, consistent patterns of flexibility are required to establish consistency when dealing with changing circumstances (Turner and Rindova, Citation2012). While Wouter et al. (Citation2015) suggest the agile company to rhythm with stability, Lindskog and Netz (Citation2021) and Prange (Citation2021) agree that organizations should balance stability and change to promote agility. As illustrated by the third practitioner statement:

The organizational structure is now more matrixed and systemized. So, if there is a sudden problem or a need to hurry up, it becomes more of a routine for us to meet and address it. (MIT/5/11-14)

P6. The Routine Dynamics as the source of stability and change will pattern the continuity for organizational agility

Dynamic capabilities and organizational agility

Dynamic capabilities enable the organization to be more agile and adaptable to changing market conditions (Teece et al., Citation2016) since they offer the ability to sense and respond to changes in the environment, enable an organization to respond swiftly to changes in the external environment, and enable the organization to adjust its strategy, structure, and processes to better compete in a rapidly changing environment. Management must prepare the organization for sensing, seizing, and transforming and match the correct strategy to its organizational agility (Teece et al., Citation2016). The third practitioner believes that the surviving company is not by chance; they must have the existing system regarding business uncertainty that makes them ready to react and respond to any sudden crisis, including regulatory changes, as her statement:

…the strategic hierarchy from seizing opportunities threats, making plans, etc. to evaluation, If the company manage to survive and thrive, it is a clear sign that it has got such capabilities… (MIT/5/23-25)

P7. Dynamic capabilities enhance decision-making efficiency by enabling a precision exploitation strategy that enhances banks’ organizational agility.

Organizational agility and competitive advantage

Baškarada and Koronios (Citation2018) continue what has been proposed earlier by Singh et al. (Citation2013), defining organizational agility as a quick, continuous evolutionary adjustment and entrepreneurial innovation to obtain and sustain competitive advantage. Agile organizations can quickly and effectively respond to environmental changes, allowing them to stay ahead of their competitors (Cegarra-Navarro et al., Citation2016) since only when strategy and agility work together can value be built and everlasting competitive advantage attained (Teece et al., Citation2016). Companies can quickly identify and capitalize on opportunities with an agile organization before their competitors. They can also quickly adapt to new challenges and develop innovative solutions to stay ahead of the competition (Franco et al., Citation2022). Additionally, organizational agility can help organizations stay ahead of the curve by anticipating customer needs, developing new products or services to meet those needs (Do et al., Citation2021), and implementing Industry 4.0 (Mrugalska & Ahmed, Citation2021). When competitors find it challenging to fight and replicate, organizational agility can become a source of competitive advantage. Despite such perceived, although more on performance, empirical evidence supported the significant effect of organizational agility on competitive advantage (Jan & Maulida, Citation2022; Medeiros & Maçada, Citation2022; Qosasi et al., Citation2019). As the second practitioner said:

Yes, it is true, agility is no longer negotiable,. It is important to stay ahead of your competitors and keep moving forward. (MIT/5/41-43)

Because agility cannot stand alone, it needs synergy; if you are agile, you will be superior to others. (MIT/6/15-17)

No wonder banking become the second leading industry that is doing agile transformation (Aghina et al., Citation2021) since their environmental demand required them to do so to win the competition. Even though these relationships have been updated regularly, the proposition goes to:

P8. Organizational agility supports banks with a quick response to change compared to their competitors.

To summarize, lists the proposed relationship described before.

Table 3. Summary of research propositions.

This research involves seven constructs: organizational elements as the antecedent, the conception of continuous organizational agility, and competitive advantage as the outcome. The model’s first phase examines the impact of entrepreneurial leadership, digital culture, and digital platform capability in direct and indirect relationships with all other variables. Then, focus on how organizations can develop and maintain continuous organizational agility through the relationship among routine dynamic, dynamic capabilities, and organizational agility. The constructions of the framework presented in the model agree with Singh et al. (Citation2020), which will explain how a company’s elements must all be in sync to digitally transform and concentrate on the structural dimension of organizational design.

Discussion

The interviews confirmed the research model, including the roles and relationships of each construct. Organizational elements (entrepreneurial leadership, digital culture, and digital platform capability) are indeed related and crucial in patterning activities and creating capabilities that promote organizational agility and competitive advantage, thus contributing to the possibility of continuity. One related subject that has emerged prominently in the discussion is that everything is closely intertwined with the support of regulators. OJK delivers blueprints for banking and digital transformation. Moreover, the regulations are divided into rule-based regulations (comply or pay the penalty) and principle-based regulations (comply or explain), allowing banks to improvise (MIT/4/16-20). During the COVID crisis, the government and OJK devised policies on credit relaxation, subsidies, and other policies that aided the rise of Indonesian banking.

Zhou et al. (Citation2021) and Sirén et al. (Citation2017) used the standpoint of inertia to examine how automation, entrepreneurial orientation, stretched resources, and organizational legitimacy affect incumbents in the financial service sector. They found that while digitalization alone does not improve incumbent performance, the interaction between digitalization and entrepreneurial orientation can improve performance, as entrepreneurial orientation strengthens incumbents since it encourages experimentation and a higher risk appetite as an antidote to this inertia. Change can occur beyond the individual level to examine the organizational context and facilitate a culture of growth and transition toward a digital cultural mindset (Merkt et al., Citation2021). Flashback to the global financial crisis, bank management should consider how focusing more and changing organizational culture could benefit it (Sheedy & Griffin, Citation2018). Culture produces social relational anthropology, which is crucial for banks’ operations (Ojong, Citation2018).

In factual Indonesian bank practice, digital platform capability is strengthened. Digital platforms like artificial intelligence (Fares et al., Citation2022), cyber security (Akhtar et al., Citation2021; Atkins & Lawson, Citation2021), machine learning (Dawood et al., Citation2019), robotic process automation (Thekkethil et al., Citation2021), and big data (Hassani et al., Citation2018) support bank in improving the speed, efficiency, and effectiveness of its current business processes. In practice, these technology-based support systems minimize manual work (and the risk of human error), capture opportunities faster, and produce more precise and futuristic analyses and decisions. For example, using artificial intelligence in clustering and profiling customers (Fares et al., Citation2022) and machine learning to capture their live behavior (Dawood et al., Citation2019) will help the Bank’s direct targeted promotional strategies, reducing the cost of failure. New technologies provide business advantages, as firms may produce cheaper IT-based business innovations than their rivals by adopting flexible IT infrastructure and digitizing business processes.

Work culture is built on how all company members do business with one frequency to achieve common goals. Innovation, believed to be one of the drivers of agility, is instilled into habits through various culture activation programs. Thus, it can become the top-of-mind for every employee and bank activity. All other elements become stronger when entrepreneurial leaders are open to setting concrete examples and taking relevant risks (PCT/1/30-31). Today’s bank leaders can no longer choose to escape risk completely. They encourage collaboration to establish a manageable risk appetite. Tuominen et al. (Citation2020) conceptual framework shows how value co-creation happens during service company change, how the ostensive, performative, and artefactual parts of institutional rules and routines must align for any change to happen, and this alignment is made through planned and practice-based activities throughout the institutional change. Highly regulated institutions are commonly perceived to be associated with hierarchical organizational structures. Improvisation accelerates innovation in decentralized but regulated enterprises that maximize resource flexibility (Liu et al., Citation2018) and clarifies relational governance and firm performance (Yeniaras et al., Citation2021). Based on the practitioner’s statement, agility training is also given periodically to implement changes quickly (MIT/6/23-24).

Employees were trained to perform good improvisations under any limitations (moreover, during the pandemic). The interviewees believed that this improvisation made the changing atmosphere less resistant, and employees tended to be creative in proposing alternative solutions when facing problems. New workers are involved in the project as much as possible outside the training program, especially those facing regulatory problems. They are entrusted with handling it, so they gain direct experience and, with their seniors’ guidance, can be creative in finding solutions (PCT/4/3-6). Routine dynamics, with its performative part, helps the business unit sense the opportunities and any other changes. Routines are viewed as relationships between input and output and as emerging practices that evolve over their performances and, as a result, generate changes (Feldman et al., Citation2016). As building blocks of capabilities, routines show businesses how to utilize their existing assets best or repurpose them to generate new ones that add value to the company’s operations (Bredillet et al., Citation2018). Instead of seeing stable routines and improvisation as a trade-off, organizations must deliberately seek harmony and manage them together (Carvalho, Citation2023). Lepratte and Yoguel (Citation2023) suggest using routine dynamics as an emergent way to create novel concepts related to the dynamic capabilities-building approach.

The shift from traditional to new banks is unavoidable as banks must adapt to disruptions, pandemics, and unpredictable business uncertainties. Agile newcomers who prioritize customer experiences pose a threat to traditional banks. Incumbents attempt to stay efficient while competing with challenger banks that offer more adaptable, individualized services. These legacy systems are often inflexible and difficult to update, which results in a lack of agility and responsiveness. Wardhana et al. (Citation2022) suggested that adaptive organizations minimize technology disruption and facilitate transformation as the core elements and transformation catalyst. Competition in the financial sector is notoriously fierce, and most successful institutions have learned to anticipate and respond to potential threats effectively. Banks with superior managerial or technological capabilities have long-term competitiveness (Saeidi et al., Citation2019). Financial service firms can differentiate themselves from their competitors by offering personalized services, tailored advice, and providing customers with unique and valuable experiences.

Finally, speed and flexibility in organizational agility determine the edge over the competition. Banks should efficiently have this capacity over the other things that can be imitated. In her framework, Walter (Citation2021) conceptually put organizational agility between the organizational agility dimensions and competitive advantage, describing that agility capabilities are applied across multiple dimensions, leading to an overall increase in high organizational agility and, thus, can enhance competitiveness. In that case, it can respond to market changes faster than its competitors through organizational agility and synergizing external and internal resources and capabilities to boost performance and competitiveness (Liu and Yang, Citation2020). With organizational agility, companies can quickly develop new products and services, develop new ways to solve problems, and respond quickly to problems that come out of the blue. Organizations that demonstrate high levels of agility can capitalize on emerging opportunities and avoid potential threats more effectively, enabling them to gain a competitive advantage over their less agile competitors.

Each element’s functions are implemented daily into a corporate routine that produces its current capabilities and characteristics on how the five banks become that big with a competitive advantage that has been proven to be able to go through several crisis phases in Indonesia. From the global crisis to the pandemic, all responding banks have gone through it well and survived with their current excellent performance. The proposed model combines variables and relationships that bank practitioners validate to unveil the key factors influencing Indonesian banks’ continuous organizational agility.

Despite its importance, the Indonesian banking landscape may face particular challenges when implementing the proposed model. First, the antecedents employed by the model, including entrepreneurial leadership, digital culture, and digital platform capability, are not universally standardized across all banks. Some banks already have one, while others are currently in the development or planning stages. Banks must allocate resources to construct and maintain them regardless of the stage. Second, as the Indonesian banking industry is currently influenced by three generations (Gen X, Y, and Z) of talents, bringing their unique characteristics to the table, banks are also confronted with the challenge of harmonizing their operational procedures, performance standards, and modes of communication in adopting new approaches that necessitate shifts in mindset, culture, and established ways of working. Third, due to periodic reporting pressure, Indonesian banks, at a specific time, prioritize achieving short-term financial targets rather than long-term strategic plans. As outlined in the model, this may impede any decision in fostering related variables. Lastly, although the issue regarding digital infrastructure has been regulated and standardized by OJK, after the implementation stage of digitalization, there is a clear requirement to enhance Indonesian banking professionals’ digital skills and mindset. Developing a robust digital culture and capabilities can be hindered by the lack of digitally talented workers and conservative organizational mindsets.

Conclusion

Organizational agility studies on banking are still relatively rare, especially in Indonesia, an emerging economy. This contrasts with the fact that Indonesia’s Bank, compared to those in other industries, has maintained its continuous post-crisis existence, which should be considered agile in a continuous way. This study aims to develop a model that identifies and validates the key factors and relationships that impact a bank’s continuous organizational agility. The outcome sparks a new conversation about the critical components of entrepreneurial leadership, digital culture, and digital platform capability, particularly concerning the Indonesian banking industry’s inevitable digital landscape. The variables specifically add more key terms relevant to the agility literature. Furthermore, continuous organizational agility will follow as a manifestation of the intertwined routine dynamics, dynamic capabilities, and organizational agility relationships motivated by the collaboration of various aspects of strategic management theory. Finally, the model assists businesses in comprehending the impact of the regulatory environment on organizational agility in the Indonesian banking sector, ensuring the power to create stability within banks’ dynamics.

Direction for further research

Although this goal has been successfully achieved, this study has some limitations. First, a literature review was conducted based on a theory-matching approach. It is challenging for future researchers to explore systematically under framework-based literature reviews, such as the ADO-TCM or 5W1H approaches. Second, the practitioners’ validation of this study is limited to the Indonesian banking context, which has a particular country and economic condition that only applies to emerging countries. Thus, further studies can expand to other levels of country characteristics and obtain new conceptual insights. To replicate and enhance the significance of the findings, further research may also broaden the scope of data. This could involve expanding the sample to include small and medium banks, incorporating low and mid-level professionals, and considering the inclusion of Non-Bank Financial Institutions such as insurance companies. Finally, the use of organizational elements and routine dynamic variables represents the internal aspects of the organization. However, future studies should include external factors in the model to complete the scope of strategic management. This has the potential to provide additional insights into the concept of continuous organizational agility. As this study is conceptual, future research should aim to empirically test the proposed research model and contribute to the existing literature by providing quantifiable evidence.

Author’s contribution

All authors agree to be accountable for the following aspects of the work.

Inta Hartaningtyas Rani: Conception, design, data preparation, main analysis and interpretation, initial draft, and funding awardee.

Rhenald Kasali: Conception, supervision, and the final approval to publish the article.

Ratih Dyah Kusumastuti: Conception, providing feedback, and revising for content.

Sri Rahayu Hijrah Hati: Conception, providing feedback, and revising for content.

Research material availability

As the participants in this study did not provide an explicit agreement for the public sharing of their complete data, the supporting data is unavailable owing to the confidential content of the research.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge appreciation for the financial support from the Indonesian Ministry of Finance’s Endowment Fund for Education (LPDP) and the positive collaboration with the bank practitioner participants.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Inta Hartaningtyas Rani

Inta Hartaningtyas Rani is a doctoral student at the Graduate School of Management Science, University of Indonesia. She is also a Lecturer in Accounting and Management at Ahmad Dahlan Institute of Business and Technology, Jakarta, Indonesia.

Rhenald Kasali

Rhenald Kasali is a Professor at the Department of Management, Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Indonesia. He is also the founder of the Indonesian Management Association, the founder and president of the Indonesian Marketing Association, and the author of several books on marketing and business topics.

Ratih Dyah Kusumastuti

Ratih Dyah Kusumastuti is an Associate Professor at the Department of Management, Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Indonesia. Her research context primarily concerns sustainable supply chain management, disaster management, and sustainable development goals.

Sri Rahayu Hijrah Hati

Sri Rahayu Hijrah Hati is a Professor at the Department of Management, Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Indonesia. Her research interests focus on marketing management and the halal industry.

References

- Aburub, F. (2015). Impact of ERP systems usage on organizational agility. Information Technology & People, 28(3), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-06-2014-0124

- Aghina, W., Handscomb, C., Salo, O., & Thaker, S. (2021). The impact of agility: How to shape your organization to compete. McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/people-and-organizational-performance/our-insights/the-impact-of-agility-how-to-shape-your-organization-to-compete

- Ahmed, A., Bhatti, S. H., Gölgeci, I., & Arslan, A. (2022). Digital platform capability and organizational agility of emerging market manufacturing SMEs: The mediating role of intellectual capital and the moderating role of environmental dynamism. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 177, 121513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2022.121513

- Ajgaonkar, S., Neelam, N. G., & Wiemann, J. (2022). Drivers of workforce agility: A dynamic capability perspective. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 30(4), 951–982. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOA-11-2020-2507

- Akhtar, S., Sheorey, P. A., Bhattacharya, S., & Ajith Kumar V. V. (2021). Cyber security solutions for businesses in financial services.International Journal of Business Intelligence Research, 12(1), 82–97. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJBIR.20210101.oa5

- Arunprasad, P., Dey, C., Jebli, F., Manimuthu, A., & El Hathat, Z. (2022). Exploring the remote work challenges in the era of COVID-19 pandemic: Review and application model. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 29(10), 3333–3355. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-07-2021-0421

- Atkins, S., & Lawson, C. (2021). Cooperation amidst competition: Cybersecurity partnership in the US financial services sector. Journal of Cybersecurity, 7(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1093/cybsec/tyab024

- Awwad, A. S., Ababneh, O. M. A., & Karasneh, M. (2022). The mediating impact of IT capabilities on the association between dynamic capabilities and organizational agility: The case of the Jordanian IT sector. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 23(3), 315–330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40171-022-00303-2

- Azeem, M., Ahmed, M., Haider, S., & Sajjad, M. (2021). Expanding competitive advantage through organizational culture, knowledge sharing and organizational innovation. Technology in Society, 66, 101635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101635

- Baloch, M. A., Meng, F., & Bari, M. W. (2018). Moderated mediation between IT capability and organizational agility. Human Systems Management, 37(2), 195–206. https://doi.org/10.3233/HSM-17150

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700108

- Baškarada, S., & Koronios, A. (2018). The 5S organizational agility framework: A dynamic capabilities perspective. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 26(2), 331–342. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOA-05-2017-1163

- Batko, R., Ćwikła, M., Szopa, A., & Zawadzki, M. (2018). Organizations in era of digital culture. In Advances in ergonomics of manufacturing: Managing the enterprise of the future. Springer. (pp. 63–73). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-60474-9_6

- Bechtel, J., Kaufmann, C., & Kock, A. (2023). The interplay between dynamic capabilities’ dimensions and their relationship to project portfolio agility and success. International Journal of Project Management, 41(4), 102469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2023.102469

- Bertels, S., Howard-Grenville, J., & Pek, S. (2016). Cultural molding, shielding, and shoring at oilco: The role of culture in the integration of routines. Organization Science, 27(3), 573–593. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2016.1052