Abstract

This research explores the relationship between liquor brand representatives and bartenders, its effects on the bartenders’ profession and subsequent theoretical implications from a Persuasion Knowledge Model perspective. Seven senior craft cocktail bartenders who act as both ‘agent’ and ‘target’ in the sale of alcohol were interviewed. As the ‘target’, they work with brand representatives who try to persuade them to purchase the brand’s product(s) for resale. As the ‘agent’, they then persuade their customers to purchase products. This study uses a grounded theory approach with a thematic analysis to examine the experiences of craft cocktail bartenders. Four themes emerged that were categorized as (1) passion, (2) purism, (3) storytelling and (4) personal branding. Findings were put into the Persuasion Knowledge Model, adding depth to our understanding of the model when someone with high topic, agent, and persuasion knowledge is both an ‘agent’ and a ‘target’. Results showed: bartenders’ high knowledge (topic, agent and persuasion) leads to both skepticism or trust in the brand representatives, depending on the level of knowledge the brand representative displays and whether or not that satisfies the bartender’s expectations; when a ‘target’ is an expert, ‘agent’ attitude is second to topic knowledge; bartenders use the same persuasion attempts as the ‘agent’ that are effective on them as the ‘target’; when bartenders felt validated, this aided in persuasion; when ‘targets’ are passionate, they respond more favourably to ‘agents’ they perceive as passionate; bartenders actively seek topic knowledge through internal motivations; and bartenders’ passion informs their persuasion attempts.

SUBJECTS:

Introduction

Bartenders have a unique, and sometimes overlooked, role in society. On the front lines of alcohol sales, bartending is sometimes seen as a temporary job for young people or aspiring artists to undertake before settling down in a chosen career path, as often portrayed in media tropes. Less obvious is their service as cultural intermediaries between the alcohol industry and the consumer, whereby bartenders mediate the presentation and representation of the spirits themselves (Ocejo, Citation2012). For many, bartending is a rewarding career with a level of autonomy in the position that allows for personal expression, creativity and the individualized dissemination of the information collected through tastings, competitions, seminars, research, conferences, purchasing and other methods and experiences. As the cultural intermediary of spirits and cocktails, bartenders also become practical intermediaries in a chain of communication, connecting the final consumer and the brand representative. Brand representatives work closely with bartenders in a direct-sales capacity, typically presenting a large portfolio encompassing many different spirits. In this study, ‘brand representative’ is used as a catch-all term to include other similar positions such as brand ambassador or liquor rep. As a middleperson, a bartender’s passion and perspectives may alter how they proceed as someone who both persuades and is persuaded in the alcohol industry.

The industry

In times of celebration or times of sorrow, alcohol has been a pervasive part of the human experience for thousands of years (Phillips, Citation2014), during which society has continued to refine the process of fermentation and distillation. The result is a modern global industry dedicated to the production of spirits, beer, wine, and everything in between. Despite temperance movements and prohibitions, the sale and consumption of alcohol has endured. However, public perception continues to shift, largely due to concerns about the public health effect of alcohol and the influence of advertising. For this reason, academic research focusing strictly on this industry is not often undertaken from a marketing or consumer behaviour perspective. Also, alcohol is subject to stringent advertising guidelines that control where, when and how spirits may be promoted, which can act as a deterrent for advertisers.

Canada’s alcohol industry is currently exhibiting increased sales by revenue but decreased sales by volume. In the fiscal year ending 31 March 2022, Canadian liquor authorities and other retail outlets sold $26.1 billion worth of products, which marks a 2.4% increase in revenue sales over the previous year. However, Canadians purchased 1.2% less alcohol-by-volume, which is the largest decline in over a decade (StatCan, Citation2023). As of 2023, there are approximately 3,965 bars (IBIS World, Citation2023) and 79,931 full-service restaurants (IBIS World, Citation2022) in Canada, though only a small percentage of these offer craft cocktails.

It is relevant to note there are industry restrictions around how they can legally advertise to encourage growth, which can be used to help increase both monetary sales, as well as increase the amount of alcohol-by-volume sold. In Canada, advertising is not strictly regulated at the federal level. Existing regulations are mostly found in the Competition Act, which legislates against ‘deceptive marketing practices’. These regulations can be broken down into practical rules of telling the truth and not misleading the audience with false claims, be they about pricing, warning or efficacy. This extends to the general impression given by the marketing and not just what is overtly stated (Competition Act, Citation1985). These laws aim to provide an equitable platform for organizations of all sizes to compete fairly and are enforced by the Competition Bureau.

In addition to the Competition Act, Canada has a non-profit organization called Ad Standards (formerly Advertising Standards Canada), which acts as a self-regulatory body for the Canadian advertising industry. It created the Canadian Code of Advertising Standards to guide advertisers, though the code is not legally binding. This code is sometimes referred to in provincial-level alcohol advertising legislation, as is the case for The Liquor, Gaming and Cannabis Control Act in Manitoba (The Liquor & Gaming & Cannabis Control Act, 2013). The code makes no mention of specific provisions for the marketing of alcohol or other controlled substances, with the exception that products prohibited to minors should not be advertised in a way that appeals to minors, and those in the advertisements must clearly be of legal age (Ad Standards, Citation1963).

With the Competition Act governing advertising at a federal level and Ad Standards self-regulating the industry, the next layer of protection from deceptive or harmful alcohol advertising is provincial. It is common for provinces to create regulatory bodies to oversee and enforce various legislation and licensing, from psychology to alcohol. This creates a wide array of additional laws that govern each province’s alcohol advertising. Some provinces such as Alberta, whose legislation is enforced by the Alberta Gaming, Liquor and Cannabis Commission, have very little in the way of regulations (Gaming & Liquor & Cannabis Act, Citation2000), while others such as Ontario, whose Liquor Licence Act is overseen by the Alcohol and Gaming Commission of Ontario, have a more comprehensive set of policies (Liquor License Act, Citation1990).

These various governing bodies, both regulatory and self-regulatory, work together to dictate what is acceptable for liquor advertisers and to protect vulnerable populations. This concern for public health in relation to alcohol is echoed in current research that pertains to alcohol advertising, often focusing on unhealthy alcohol-consumption habits (Noel et al., Citation2018), violence (Trangenstein et al., Citation2020) or how advertising may reach and affect children (Aiken et al., Citation2018; McClure et al., Citation2020). This type of public-health research extends to the profession of bartenders, who have a high rate of hazardous drug and alcohol consumption (especially men; Bell & Hadjiefthyvoulou, Citation2022).

Each customer is unique and so is their experience with the bartender, who has a level of discretion in his or her service style. Bartenders work closely with both customers and the spirits themselves in a job akin to direct sales. This puts bartenders on the front lines, interacting directly with consumers, potentially persuading them to purchase specific spirits or brands. Due to these interactions, bartenders have been likened to street-level bureaucrats (Buvik & Tutenges, Citation2018). A brand may try to increase sales through brand representatives that provide knowledge, training and direct sales to the bartenders, creating an indirect link to the consumer. To do this, the brand must first persuade the bartender, who in turn persuades the consumer.

Theoretical framework

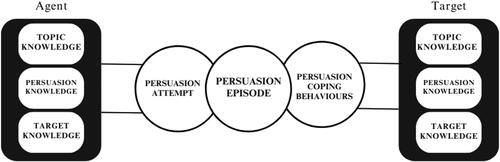

In the modern day, marketing is rarely covert. Consumers are aware that they are being sold to or persuaded, throughout their day. This can take place digitally, as targeted ads on Instagram, influencers, sponsored and appropriately hash-tagged user generated content, email newsletters or in the physical world such as billboards on the street, a full-page spread in a magazine or a salesperson offering samples at the mall. With this at the forefront of their daily lives, consumers build an understanding of these persuasion attempts, which grows and changes with social influence and the collection of information – a general tendency known as the Persuasion Knowledge Model (). Labeled as ‘targets’, consumers each possess a unique combination of topic knowledge, ‘agent’ knowledge and persuasion knowledge that results in their own persuasion coping behaviour. During a persuasion episode, this is matched against the agent’s own knowledge of the topic, persuasion and the target, culminating in the agent’s persuasion attempt. However, each of these types of knowledge is malleable and can change over the course of the persuasion episode (Friestad & Wright, Citation1994).

Figure 1. Persuasion Knowledge Model (Friestad & Wright, Citation1994).

Persuasion knowledge is the most studied aspect of the Persuasion Knowledge Model, though the quantitative research does not use a set method of measurement (Ham et al., Citation2015). Persuasion knowledge can be broken down into two subcategories: conceptual persuasion knowledge, which includes a person’s comprehension of intent and strategy, and evaluative persuasion knowledge, which is swayed by skepticism, personal morals and whether or not one deems the persuasion attempt appropriate. These categories make up the five determinants of persuasion knowledge, which are (1) beliefs about psychological mediators, (2) beliefs about marketers’ tactics, (3) beliefs about one’s own coping tactics, (4) beliefs about the effectiveness and appropriateness of marketers’ tactics, and (5) beliefs about marketers’ persuasion goals and one’s own coping goals (Friestad & Wright, Citation1994).

Targets can react negatively to persuasion attempts if they are cognizant of their occurrence (Wei et al., Citation2008). For this reason, editorial persuasion attempts resulted in a higher purchase intent than advertorial or advertising in one study (Attaran et al., Citation2015). Distrust of advertising can be mitigated through different types of covert marketing such as user-generated content, a popular feature of social media marketing campaigns (Mayrhofer et al., Citation2020). However, paid sponsorship on social media that is denoted with a disclaimer can activate conceptual persuasion knowledge among consumers who now recognize that they are being persuaded (Boerman et al., Citation2017).

A target with a heightened level of persuasion knowledge is not always detrimental for a persuasion episode. Substantial persuasion knowledge can lead to a higher perceived credibility of the agent (Isaac & Grayson, Citation2016). If the agent is seen as authentic, affirmative coping mechanisms may be used, such as a willingness to rely on the agent’s persuasion attempts (Borchers et al., Citation2022). High persuasion knowledge may also mitigate the extent to which a target perceives sales pressure, allowing them to better cope (Zboja et al., Citation2021). Psychological mediators, such as building trust or communicating other positive emotions, can also lead to positive coping behaviours for targets (Mohr & Kühl, Citation2021).

It is assumed that consumers hold valid topic attitudes; however, targets, with less topic knowledge more readily admit that they cannot rely on their own knowledge of the product and therefore are more likely to require additional resources to make a purchasing decision (Friestad & Wright, Citation1994). This allows for experts of a given topic, such as bartenders, to provide this knowledge to the consumer, bridging the divide.

Upon first entering a persuasion episode, targets and agents have a ‘get-acquainted opportunity’ according to Friestad and Wright (Citation1994), where they develop their knowledge. Targets’ perception of the appropriateness of the persuader’s actions can have long-term effects on their attitude toward the agent. Salespeople who apply too much pressure may find that it results in negative satisfaction and trust outcomes (Zboja et al., Citation2016).

The source of the persuasion attempt can also change the perceived credibility of an agent. A prior study showed that despite having more knowledge of internet advertisements, consumers found newspapers to be the most credible source among newspapers, radio, internet, television and magazines (J. J. Moore & Rodgers, Citation2005).

Not considered in the original Persuasion Knowledge Model are additional factors that might affect a persuasion attempt such as who is with the target. Relevant to this study, social influences can have an effect on a consumers’ intentions to purchase premium alcohol, especially for those who are brand conscious or status-driven (Cunningham, Citation2023).

For bartenders who act as both agent and target in their work, what effect do the persuasion attempts from brand representatives have on their work experience and subsequent persuasion attempts with the final consumer? How does the Persuasion Knowledge Model function in this context? As the target, bartenders work closely alongside brand representatives who manage their accounts and use various forms of overt persuasion. Due to their high topic knowledge, as well as the potential for an ever-increasing agent knowledge, bartenders may not be influenced by persuasion attempts in a typical fashion. As the agent, bartenders use various forms of persuasion with the customer. Their vast topic knowledge and target knowledge may allow them to leverage genuine and passionate persuasion attempts with consumers. This research explores the Persuasion Knowledge Model from the perspective of someone who acts as both agent and target in the service industry.

Methodology

Qualitative data collection was chosen to allow participants to describe their experiences as broadly as possible and to share stories in their own words, enabling richer insights into this phenomenon. In-depth, semi-structured interviews were appropriate for this research to best understand the lived experiences of bartenders. The use of qualitative interviews facilitated a thematic analysis to allow theory-driven findings to potentially emerge from the research questions (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006).

Participants

In total, seven in-depth, qualitative interviews were conducted with bartenders from different bars across Canada. The interviews involved six males and one female (Appendix A). The recruited participants were chosen for their prominence in the Canadian cocktail industry. Purposive sampling technique, using select criteria, was used for this study. Criteria for participation included being a well-established bar tender in Canada, they had to work in an acclaimed bar with a craft-cocktail heavy menu, and have experience working directly with brand representatives. After we received study approval from the institution’s Human Ethics Review Board (Protocol # HE18392), participants were recruited through Instagram Direct Messages. Upon agreeing to be interviewed, participants were invited to a private Zoom call. They were entered into a draw for a $200 gift card. Written consent was provided via email through a signed consent form before the individual interviews commenced. Names of participants have been changed in this journal article to allow for anonymity. Purposive sampling was used as this was a very specific homogenous group being explored and a limitation of this type of sampling is it can be ineffective for large populations. As well, it is important to note that this type of sampling can also manipulate the data being collected which could potentially be seen in the personal branding theme that emerged, as participants were all recruited through social media.

Data collection

The interview questions were based on a literature review on persuasion and Consumer Style Inventory (Sprotles & Kendall, Citation1986). The interview guide was created to allow for theoretical exploration of persuasion, as well as for participants to share broad thoughts and feelings for further assessment. The interview questions were semi-structured, and participants were encouraged to share their story about how they became a bartender and any and all experiences they have had with brand representatives, relationship development, and thoughts on persuasion as both the one being persuaded to purchase alcohol for their bar and the one persuading consumers to purchase alcohol. Before their interview participants were informed of the purpose of the study and signed the consent form. Each interview was audio and/or video recorded and later digitally transcribed. Interviews lasted between 33 and 85 minutes, not including briefing prior to and debriefing following the interview. As thematic analysis can use the foundation of grounded theory method (Charmaz, Citation2006), each interview was analyzed before moving on to the next. This provided an opportunity to adapt questions. After the fourth interview, the research team began seeing themes emerge and adapted the queries to dive deeper into the research question and findings.

Data analysis

A thematic analysis, employing the seven-phase strategy, was used to analyze the data (Lochmiller & Lester, Citation2017). This allowed for the creation of broad descriptive themes that reflect the overall understanding of the data in relation to the Persuasion Knowledge Model. Phase one included conducting the interviews, gathering the audio/video files into one location, a structured naming protocol, and all documentation of creator, date of collection and storage location. For phase two, automated verbatim transcription was conducted. For phases three and four, to become familiar with the data, both members of the research team read the transcripts, creating observation notes and writing detailed memos of their thoughts. The team met after each interview to review these memos together. Phase five was coding the data, where key statements and experiences of analytical importance were identified. This was also done separately and then discussed jointly by the researchers, where connections between interviews began to form. Phase six involved the researchers using their coded sections to determine the general themes they were seeing in the data, exploring how the codes were relating to or contrasting with each other. This again was done through ongoing meetings. Phase seven involved ensuring transparency in the analytic process, accomplished through the ongoing collaborative discussions of every interview, the adaptation of interview questions as information from the data emerged and ongoing documentation of the process.

Interview questions were initially structured to build a foundation of knowledge of the practical relationship between the bartenders and brand representatives and touched on the perception of being marketed to versus marketing to customers (Appendix B). Questions were adjusted as data collection continued to account for thematic development, allowing further analysis into the bartenders’ perception of these relationships. Questions ranged from their experience behind the bar, their feelings about persuasion attempts as both the target and agent and their preferences for qualities amongst brand representatives.

Following each interview, the recordings were viewed individually for initial thoughts, then analyzed by both researchers together, looking for emerging themes that related participants’ answers to one another. Noticeable themes appeared quickly, with the bartenders echoing very similar sentiments about many topics. In the end, four major themes were ubiquitous in the interviews and were applied to the existing framework of the Persuasion Knowledge Model.

Themes

Passion

One of the first themes to emerge was the passion that defined the bartenders’ genuine love for their craft and career. Many had degrees and careers that they left behind to pursue bartending, such as marketing, music and sociology. Others had found their passion early and pursued this career since early adulthood. Hunter spoke of this passion: ‘I always had a love for bartending. Always, always, always’. He was not the only one to use the word ‘love’. ‘I love bartending. Like, I love to be there and have a guest interaction’, said Adam. This passion is a tangible feeling for the bartenders. Brandon said, ‘I get a genuine rush’.

Passion is a highly desirable trait in brand representatives. The bartenders were passionate, and they wanted to see that same passion in their brand representatives. Becca spoke about the importance of passion for a brand representative to adeptly persuade her, saying, ‘Passion begets passion’. For Hunter, this passion changed his perception of the brand representative from the outset, priming him to be persuaded; he said, ‘I can tell when someone is going to successfully sell me something because they’ve made it their job to be in love with or to be passionate about the thing that they are now bringing to sell me’.

While the participants all considered passion to be a trait that they found important in their perception of a brand representative, their passion for spirits did not motivate them to want to become a brand representative themselves. Adam mentioned he was deterred from being a brand representative because he preferred ‘to not be beholden to one spirit or the other’ and added ‘there’s not a brand that I’m passionate enough’ to become a representative for. Brandon expressed similar sentiments, saying, ‘I would never want to sort myself to something particular and then kinda like pigeonhole in a particular spirit or direction. I like to be flexible’. The bartenders appreciate the creative and autonomous nature of bartending.

This passion is especially notable when you consider some of the less-than-ideal parts of the role. In past qualitative studies, bartenders have pointed to stress from the position as one of the reasons that they drink, oftentimes to what is considered a hazardous level (Buvik & Scheffels, Citation2019). Other factors bartenders must deal with on a daily basis are increased instances of sexual harassment (Klein et al., Citation2021) and non-traditional work hours (R. S. Moore et al., Citation2009).

Purism

In our context, purism refers to a focus on product quality and the experience of the consumer, and not what the ‘seller’ gets out of the relationship. A participant self-described his approach to the profession as ‘purism’. Daryl said, ‘I try to be a purist and I do love the product first’. This informed his relationships with both brand representatives and customers. His motivation came from a desire to give the best possible product and experience to the customer. Though other bartenders did not use this terminology, the sentiments were echoed in their desire to first and foremost generate an ideal experience for the customer. Becca said, ‘I pour spirits but I’m actually providing an experience’.

We heard through all the interviews how the bartenders listened to their customers, sometimes covertly, to ensure that they were giving personalized service – a service that partially relied on the knowledge and products provided to them by the brand representatives. For some, this was regarded as a major benefit of the relationship. However, if the brand representative was unable to impart useful knowledge, the bartenders were more dismissive of them. Daryl noted he would forgo potential benefits offered by brand representatives, such as merchandise or discounts, in order to bring in the best product if it was not in the brand representative’s portfolio.

When discussing whether the participants engaged in persuasion, the answer was often that they did so subconsciously. When asked if he uses persuasion skills, Brandon said, ‘Possibly unintentionally. Yes. I like to think that I just provide what people want or I help them arrive at a destination to what they want’. This purism leads to a motivation to provide this service for reasons other than financial gain. While the bartenders are paid for their expertise, both in wage and tips, few try to inflate the bill specifically to get a larger tip.

Persuasion was often acknowledged only as something the bartenders engaged in when they thought it was beneficial to the customer. While the bartenders agreed they had a higher level of expertise than the consumers, they noted that the consumers were experts in their own personal taste. No matter the quality of a spirit or cocktail, what was most important was catering to the taste of the customer, even if it meant using an objectively worse spirit. Hunter said, ‘If I’m pushing anything, it’s because I genuinely think that the person needs it or will enjoy it’. This speaks to their purist motivations in how and when they choose to persuade their customers.

Storytelling

When the participants did engage in conscious persuasion attempts, they often employed the use of storytelling. Adam stated, ‘It’s the story that sells it’. The participants shared stories during the interviews that had changed how they perceived products. ‘I’ve never cared for the flavour of Ouzo in my life until I had a Greek tenant talk to me about his love for Ouzo, and how his family used to drink it, and why they drink it’, Hunter mentioned.

In some instances, the persuasion did not always centre on the quality of the spirit. ‘You have some of the palate stuff but again it usually stands out more, the stories, than the actual palate stuff’, said Daryl, especially when the participant knew that they carried more expertise than their ‘target’. The use of storytelling works in conjunction with the purist approach in creating a unique and rewarding customer experience.

Storytelling was something they enjoyed when they were the target of a persuasion attempt by a brand representative. This type of persuasion empowered the bartenders with information that they could then share with their customers. Although bartenders can draw their own conclusions on the quality and flavour profiles of the spirits, the storytelling of the distillery’s practices and history was a component that they were more reliant on the brand representative for.

Hearing the brand representative relay stories really drove the point home about the importance of passion, knowledge and personality, all of which the bartenders deemed important in the makeup of a brand representative. While qualitative studies have shown that storytelling can bolster corporate pride for internal stakeholders (Nyagadza et al., Citation2020), the bartenders show that this pride can have a spillover effect, as they respond positively to the brand representatives’ storytelling.

Brand representatives also gave them opportunities to create their own stories. Brand-sponsored trips are one way that bartenders can create unique stories surrounding a brand and building brand loyalty. ‘It’s part of its education and when you have all that education, I mean, it definitely influences your understanding of the product and you’re more willing to use it’, said Thomas. Trips are sometimes given as prizes for cocktail competitions. ‘I can do a side-by-side tasting of, you know, two products and I can talk more about their product and the taste profile than the other one. Just purely because I spent three days out at the distillery and I did tastings with all the right people’, said Max about his ability to sell Patron over other brands of tequila, thanks to a brand-sponsored trip.

Personal branding

Another theme that arose from the interviews was the concept of personal branding. Whereas the bartenders are employed by the bars they work in, we discovered that they often act as separate entities from the bar. When speaking, the bartenders separated themselves from their bar. For example, when asked if brand representatives have done them a favour, Brandon clarified they did the bar a favour, not him. He also said, ‘I have a vision of what I want to do, and I live to serve the vision’. Other participants were more direct when talking about their personal branding. Max said, ‘I try to build a brand around myself’.

The term personal branding, coined in 1997 in the publication Fast Company (Peters, Citation1997), is not a new concept in marketing. The term can be defined as a ‘strategic process of creating, positioning, and maintaining a positive impression of oneself, based in a unique combination of individual characteristics, which signal a certain promise to a target audience through a narrative and imagery’ (Gorbatov et al., Citation2018, p. 6). Consciously or not, the bartenders displayed tactics that align with this definition.

The bartenders serve as micro-influencers, putting their work on social media. Each features pictures of their cocktails on their social media feed, with two participants consistently making bar-related content in an influencer fashion. One of the influencer-type participants, Adam, said he is requested to shout out products on his personal account but not the bar he manages. ‘They’ll give me a bottle, say, “Hey, like, why don’t you play with this if you want and do some stuff on your social media”.’ Social media is one medium that bartenders can progress their personal brand through narrative and imagery.

As in other niche communities, competent personal branding efforts can transform bartenders into influencers. In these cases, not only are they influential to consumers, whose lack of expertise may leave them more easily influenced, but they also reach the more discerning experts such as other craft cocktail bartenders. The promise that the bartenders signal to their target audience is the promise of high product knowledge.

The participants spoke generally favorably about influencers. Hunter described influencers as ‘someone that has a set of either skills, opportunities or contacts, resources if you will, really, and someone that they can connect to those resources’. In discussions about influencers, he suggested that influencers will change how brands interact with bartenders: ‘Brand ambassadors will not be a thing as we know it, because already the game has changed so much’. Brandon also noted, ‘I don’t think reps really know what’s trending in cocktails’. He cited knowledge, skill and aesthetics as what he appreciated about cocktail influencers.

The act of personal branding is not limited to social media. The bartenders are also able to cultivate their unique brand at their establishments, building rapport with customers in person. The bartenders described their service styles, which ranged from subdued with a focus on listening, to integrating magic and showmanship. Each participant was able to articulate their service style, implying a level of consciousness of how they position themselves in these interactions.

Through personal branding craft cocktail bartenders are able to harness their passion, purism and storytelling to differentiate themselves from other bartenders in the industry and to reach a wider audience than those sitting on the opposite side of the bar.

Persuasion Knowledge Model

As bartenders, the participants exist in a chain of communication between brand representatives and the final consumer – the patrons at the establishment. These expert bartenders are poised as both target and agent for spirits-based persuasion episodes. Their unique perspective, informed by passion and purism, shapes their topic, agent/target and persuasion knowledge.

Persuasion episodes between brand representatives and bartenders typically happen at the bar itself, usually at a previously agreed upon time. Brand representatives have been known to just drop in, according to the participants, but this is not well received by the bartenders.

When bartenders are participating in a persuasion episode as a target with a brand representative as an agent, the episode involves two competing experts. Although the participants noted that not all brand representatives are experts (despite knowledge being the most desired trait in a brand representative), they often acknowledged the brand representatives have a deep, albeit narrow, topic knowledge. The participants shied away from using the word ‘expert’ but described themselves as highly knowledgeable when it came to spirits. Their knowledge came from their own research, mentors in the industry as well as knowledge provided by the brand representatives.

Their own high topic knowledge as a target allowed them to respect the topic knowledge of the agent, when applicable, but left room for distrust to fester if they thought the brand representative did not, in fact, know their products, which made the bartenders dismissive of them. This makes their topic knowledge a double-edged sword for the agents, which can make or break a persuasion episode.

As a target, the bartenders are well aware these scheduled meetings with the brand representatives are persuasion episodes, and they are able to describe the agent’s methods and what they bring to the table during these episodes such as storytelling, discounts, trips, and merchandise. These tactics are generally accepted by the bartenders and deemed appropriate. Storytelling was an effective form of persuasion for the bartenders, as it signaled both passion and knowledge. The bartenders’ coping goal was often to maintain their purism by bringing in products from the brand representatives that aligned with what they thought the consumer would like, as well as products that aligned with their own preferences.

The knowledge the bartenders had of the agent, and vice versa, also varied. Some participants described close relationships with brand representatives akin to friendships; others noted they kept a more professional relationship with them. The knowledge of their counterparts can be built over time. Participants spoke highly of having brand representatives come to their bars for leisure and not just for work. This made the participants feel validated and to think the brand representatives were being authentic. Though frequenting the establishment is not a persuasion attempt, this can aid brand representatives in future persuasion attempts. This networking opportunity with the brand representatives can also be beneficial for the bartenders’ personal brands as they build connections.

The bartenders are open to these persuasion attempts and employ few persuasion coping behaviours besides initial skepticism. They are able to be won over, given that the agent works to ensure the target has a positive agent attitude. This positive agent attitude is granted to brand representatives who are knowledgeable and can demonstrate passion, though the value added through discounts and merchandise is still appreciated.

When the bartenders become the agent, they bring their high topic knowledge to the persuasion episode. The bar patron, who is the target in this scenario, is considered to have a low topic knowledge, according to the participants. They do acknowledge this is unimportant, as the targets know what they like, making them experts in their own tastes and preferences. This is where the participants then leaned into their own purism for the profession. They shared that they do not wish to persuade the customers to purchase something for the sake of increasing sales, tips, or appeasing a brand representative but rather to improve the experience for the bar patron. This in turn can assist in increasing the targets’ agent attitude, as they should not feel like they are being persuaded.

Bar patrons represent a wide swath of people, meaning the target can have varied levels of experience with persuasion knowledge. The bartenders spoke about persuasion methods but did not usually describe them as such. One of their favourite methods of persuasion was storytelling and being able to provide knowledge to the target, sharing their expertise. This tied into their desire to make the customers’ time at the bar more of an experience, beyond just consumption of the product.

Agent and target knowledge can also vary greatly in these bartender/patron persuasion episodes. Bartenders are equipped with a general knowledge of their targets, with the participants sometimes describing archetypes in their interviews. They can build this knowledge throughout the interaction or over an ongoing relationship if the patron continues to frequent the establishment. In turn, the targets can build their specific agent attitude over time, though they may enter the persuasion episode with preconceived opinions based on what they already know about the establishment. This is their get-acquainted opportunity, according to Friestad and Wright (Citation1994). The bartender’s passion, purism and storytelling can help build a positive agent attitude during these encounters; however, personal branding on public platforms such as Instagram and TikTok may allow the target to begin forming an agent attitude before even entering the bar.

In these persuasion episodes, the target might be on-guard for persuasion attempts with which they are familiar, such as upselling, that may trigger a negative reaction. If the agent defies those expectations, such as by showing true passion and purism, this can change how the target views the interaction, resulting in a positive attitude change.

General discussion

Theoretical implications

This study resulted in important theoretical contributions related to the Persuasion Knowledge Model, using qualitative data to add depth to our understanding of the model when someone with high topic knowledge, high agent knowledge and high persuasion knowledge ends up being both an agent and a target. This study contributed to academic research by producing empirical evidence to further understand the Persuasion Knowledge Model in a unique context.

We know that targets can react negatively to persuasion attempts if they are cognizant of their occurrence and interventions include editorial persuasion, user generated content, or even disclaimers. This research adds to those interventions by demonstrating the role that genuine passion for the topic plays in persuasion attempts and how this can allow a very cognizant persuasion attempt (ie. brand representative there to sell their goods) to still be very effective when the agent is seen to have purity for the topic and genuine passion for the item being sold.

Further understanding of the Persuasion Knowledge Model includes demonstration that when a target has ‘high knowledge’ (topic, agent and persuasion) it can lead to both skepticism and trust in the agent. This demonstrates the importance of the agent not only having awareness of the target’s knowledge but also the self-awareness of their own knowledge and how that can affect the persuasion attempt. This research also adds in some new components to consider in the theory such as when a target feels important or validated persuasion outcomes increase, along with the role that genuine passion plays in the persuasion process.

Managerial implications

Bar owners and managers should take into consideration how their bartenders persuade as an agent and are persuaded as a target. This will help them harness the innate passion that many bartenders possess for their work. If managers feel their bartenders are not in fact passionate, hiring practices may be skewed to favour displays of passion as opposed to exclusive experience or skills. A passionate bartender may make up for lack of experience in time, but a dispassionate employee might lag behind when it comes to providing an engaging guest experience.

One such way that the bar can help nurture their employees’ passion and sense of purism, while providing the necessary knowledge for storytelling, is by including employees at all levels in workshops, seminars and tastings instead of just senior staff. Promote this practice of storytelling among staff also through internal tastings or competitions. Allowing less-senior staff the opportunity to contribute to the menu will foster their creativity and autonomy at the bar, growing passion and job satisfaction.

From the perspective of spirit brands, storytelling is also of importance. Smaller craft brands may benefit from having a brand representative be their liaison with bartenders, as some participants noted they had never been visited by local craft distilleries. Brands of all sizes can benefit from the use of bartenders as influencers. This allows the brands to tap into the creativity and passion of the bartenders without stripping the bartenders of their autonomy and creativity by locking them to a single portfolio, while still playing into their strengths according to the Persuasion Knowledge Model.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. As it exclusively featured Canadian bartenders, the bartender and brand representative relationship may differ in other countries where the brand representative might be able to offer different benefits than in Canada, creating a different power dynamic between the two. The participants were mostly male, save for a single female. Craft cocktail bartending is typically skewed towards more male representation at the higher levels. For example, the 2023 Diageo World Class Canada competition has been won by a woman only once in its 10 years. However, interviewing mostly men fails to honour the unique experiences of women in a male-dominated space and how that might change their persuasion episodes, either as the target or agent. The single female participant noted she felt she sometimes had to work harder to earn her customers’ trust and be treated as an expert.

Additionally, except for the gender of the participant, demographics details such as marital status, income or ethnicity were not logged. While this leaves the participants largely anonymous in a small, niche community, it also means that additional data cannot be extrapolated from these demographics.

The study also featured a small sample of bartenders. The community of craft cocktail bartenders, especially those with experience working directly with brand representatives, is small. As this study focused on bartenders with that level of experience and responsibility, it leaves out bartenders that are newer to this career. These less experienced bartenders may be less passionate, changing how they act as agents.

Lastly, the study comes exclusively from the bartender’s perspective. In this chain of persuasion, they are only a single link. This leaves out the perception of the persuasion episodes from the perspective of both the customer as the target and the brand representative as the agent. While the bartenders may feel one way, customers and brand representatives may feel differently.

Future research

Future research may look at this chain of persuasion from other angles. As previously stated, this study has left out the perspectives of both the customer and the brand representative. The perspective of the customer might be especially interesting. While bartenders loved being on the receiving end of storytelling and employed it in their own persuasion attempts, the effectiveness of this technique for the customer is unknown. It could be that bartenders are waxing on to a disinterested audience, unbeknownst to them. This unknown effectiveness is also applicable to whether or not bartenders’ passion, or job satisfaction, is perceivable to the target or if an apathetic bartender would rate similarly in agent attitude from the target.

Another topic that could be explored more thoroughly is how personal branding evolves in niche communities. The participants all had Instagram presences that tied into their identity of being a craft cocktail bartender. One noted that doing so felt like a necessary evil for him. Additional research may hone in on motivations to personal brand on social media and how this affects one’s career, and further explore how experts perceive influencers in their niche.

Further areas for future research could include looking at this phenomenon and seeing if there are any differences or boundary conditions related to the establishment in which the bartender works. Would size, location, or style of bar have an effect on this type of persuasion? As well, future research could include exploring other differences such as culture where there could be different norms around asking, sharing or reciprocating knowledge in a persuasion attempt. Lastly this research could be explored in other contexts to see if the results transfer to other work environments to further explore the role of persuasion events in job satisfaction.

Conclusion

Bartenders are cognizant of where they exist in the chain of communication from spirit brands down to the final consumer. Due to their comparable expertise to brand representatives, who act as agents in the persuasion episodes that exist between them, they find themselves on relatively equal footing. This both helps and hinders the brand representatives in their persuasion attempts, depending on the level of trust that is built. For the bartenders, a brand representative’s passion, expertise and personality can make or break the persuasion attempt. While bartenders appreciate passion in their brand representatives, their own passion keeps them from wanting to pursue a career as one. This passion instead drives them towards personal branding, which gives them the autonomy and creativity they seek.

When bartenders become the agent in a persuasion attempt, they are motivated by their passion and purism to use storytelling to help provide an enhanced customer experience. This storytelling may sidestep the target’s persuasion knowledge, creating an experience similar to user-generated content, where the persuasion attempt is not acknowledged as one. These persuasion attempts are saved for helping the customer arrive at a decision that solely benefits them, not a decision that may result in higher tips for the bartender, though that may be an indirect benefit.

Authors’ contributions

Lauren Wagn, Sara Penner: conception, design, analysis and interpretation of the data, review and editing, and final approval. Lauren Wagn: drafting of the paper. Sara Penner: reviewing for important intellectual content.

Consent for publication

Authors have permitted this manuscript to be submitted to this journal.

Statements and declarations

There is no funding provided for this manuscript. The authors declare they have no financial interests and have no competing interests to declare relevant to the content of this manuscript.

Disclosure of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data will be made available as per request to authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Lauren Wagn

Lauren Wagn, Bachelor of Business Administration from the University of Winnipeg.

Sara Penner

Sara Penner, PhD from the University of Manitoba, Asper School of Business and is Associate Professor at the University of Winnipeg in the Faculty of Business and Economics.

References

- Ad Standards. (1963). The Canadian Code of Advertising Standards. https://adstandards.ca/code/.

- Aiken, A., Lam, T., Gilmore, W., Burns, L., Chikritzhs, T., Lenton, S., Lloyd, B., Lubman, D., Ogeil, R., & Allsop, S. (2018). Youth perceptions of alcohol advertising: Are current advertising regulations working? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 42(3), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.12792

- Attaran, S., Notarantonio, E. M., & Quigley, C. J.Jr. (2015). Consumer perceptions of credibility and selling intent among advertisements, advertorials and editorials: A persuasion knowledge model approach. Journal of Promotion Management, 21(6), 703–720. https://doi.org/10.1080/10496491.2015.1088919

- Bell, D., & Hadjiefthyvoulou, F. (2022). Alcohol and drug use among bartenders: An at risk population? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 139, 108762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2022.108762

- Boerman, S. C., Willemsen, L. M., & Van Der Aa, E. P. (2017). “This post is sponsored”: Effects of sponsorship disclosure on persuasion knowledge and electronic word of mouth in the context of Facebook. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 38(1), 82–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2016.12.002

- Borchers, N. S., Hagelstein, J., & Beckert, J. (2022). Are many too much? Examining the effects of multiple influencer endorsements from a persuasion knowledge model perspective. International Journal of Advertising, 41(6), 974–996. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2022.2054163

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Buvik, K., & Scheffels, J. (2019). On both sides of the bar. Bartenders’ Accounts of work-related drinking. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 27(3), 221–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687637.2019.1601160

- Buvik, K., & Tutenges, S. (2018). Bartenders as street-level bureaucrats: Theorizing server practices in the nighttime economy. Addiction Research & Theory, 26(3), 230–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066359.2017.1350654

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage Publications.

- Competition Act. (1985). R.C.S.C. Vol. C. C-34 § VII.1. https://laws.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/C-34/page-11.html#h-89169.

- Cunningham, N. (2023). The role of social group influences when intending to purchase premium alcohol. Cogent Business & Management, 10(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2174093

- Friestad, M., & Wright, P. (1994). The persuasion knowledge model: How people cope with persuasion attempts. Journal of Consumer Research, 21(1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1086/209380

- Gaming, Liquor and Cannabis Act. (2000). RSA Vol. C G-1.

- Gorbatov, S., Khapov, S. N., & Lysova, E. I. (2018). Personal branding: Interdisciplinary systematic review and research agenda. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2238. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02238

- Ham, C.-D., Nelson, M. R., & Das, S. (2015). How to measure persuasion knowledge. International Journal of Advertising, 34(1), 17–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2014.994730

- IBIS World. (2022). Full-Service Restaurants in Canada. 2022. https://www.ibisworld.com/canada/number-of-businesses/full-service-restaurants/1677/.

- IBIS World. (2023). Bars & Nightclubs in Canada. https://www.ibisworld.com/canada/number-of-businesses/bars-nightclubs/1685/#:∼:text=There%20are%203%2C965%20Bars%20%26%20Nightclubs,over%20the%20past%205%20years%3F.

- Isaac, M. S., & Grayson, K. (2016). Beyond skepticism: Can accessing persuasion knowledge bolster credibility? Journal of Consumer Research, 43(6), ucw063. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucw063

- Klein, O., Arnal, C., Eagan, S., Bernard, P., & Gervais, S. J. (2021). Does tipping facilitate sexual objectification? The effect of tips on sexual harassment of bar and restaurant servers. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion, 40(4), 448–460. https://doi.org/10.1108/EDI-04-2019-0127

- Liquor License Act. (1990). R.S.O. Vol. C. L. 19.

- Lochmiller, C. R., & Lester, J. N. (2017). An introduction to educational research. Sage Publications.

- Mayrhofer, M., Matthes, J., Einwiller, S., & Naderer, B. (2020). User generated content presenting brands on social media increases young adults’ purchase intention. International Journal of Advertising, 39(1), 166–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2019.1596447

- McClure, A. C., Gabrielli, J., Cukier, S., Jackson, K. M., Brennan, Z. L. B., & Tanski, S. E. (2020). Internet alcohol marketing recall and drinking in underage adolescents. Academic Pediatrics, 20(1), 128–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2019.08.003

- Mohr, S., & Kühl, R. (2021). Exploring persuasion knowledge in food advertising: An empirical analysis. SN Business & Economics, 1(8), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43546-021-00108-y

- Moore, J. J., & Rodgers, S. L. (2005). An examination of advertising credibility and skepticism in five different media using the persuasion knowledge model. Proceedings of American Academy of Advertising, 10–18. Houston, TX.

- Moore, R. S., Cunradi, C. B., Duke, M. R., & Ames, G. M. (2009). Dimensions of problem drinking among young adult restaurant workers. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 35(5), 329–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/00952990903075042

- Noel, J. K., Xuan, Z., & Babor, T. F. (2018). Perceptions of alcohol advertising among high risk drinkers. Substance Use & Misuse, 53(9), 1403–1410. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2017.1409765

- Nyagadza, B., Kadembo, E. M., Makasi, A., & Wright, L. T. (2020). Exploring internal stakeholders’ emotional attachment & corporate brand perceptions through corporate storytelling for branding. Cogent Business & Management, 7(1), 1816254. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1816254

- Ocejo, R. E. (2012). At your service: The meanings and practices of contemporary bartenders. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 15(5), 642–658. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549412445761

- Peters, T. (1997). The brand called you. Fast Company. https://www.fastcompany.com/28905/brand-called-you.

- Phillips, R. (2014). Alcohol: A history. University of North Carolina Press.

- Sprotles, G. B., & Kendall, E. L. (1986). A methodology for profiling consumers’ decision making styles. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 20(2), 267–279. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6606.1986.tb00382.x

- StatCan. (2023). ‘Control and Sale of Alcoholic Beverages and Cannabis, April 1, 2021 to March 31, 2022’. StatCan (blog). 2023. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/230224/dq230224a-eng.htm.

- The Liquor, Gaming and Cannabis Control Act. (2013). C.C.S.M. Vol. C. L153.

- Trangenstein, P. J., Greene, N., Eck, R. H., Milam, A. J., Furr-Holden, C. D., & Jernigan, D. H. (2020). Alcohol advertising and violence. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 58(3), 343–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2019.10.024

- Wei, M.-L., Fischer, E., & Main, K. J. (2008). An examination of the effects of activating persuasion knowledge on consumer response to brands engaging in covert marketing. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 27(1), 34–44. https://doi.org/10.1509/jppm.27.1.34

- Zboja, J. J., Brudvig, S., Laird, M. D., & Clark, R. A. (2021). The roles of consumer entitlement, persuasion knowledge, and perceived product knowledge on perceptions of sales pressure. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 29(4), 435–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/10696679.2020.1870239

- Zboja, J. J., Clark, R. A., & Haytko, D. L. (2016). An offer you can’t refuse: Consumer perceptions of sales pressure. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 44(6), 806–821. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-015-0468-z