ABSTRACT

Worldwide, countries are constantly exposed to the effects of global political and economic changes owing to benefit-sharing connections, whereby changes in the forms of relationships and sanction impositions can put pressure on countries’ financing systems, including the healthcare sector. This study examines the effects of economic sanctions on government healthcare spending. Quantitative data on government healthcare spending from the WHO covering the 2000–2020 period were evaluated using the Wilcoxon – Mann – Whitney test. The results showed that government healthcare spending in Iraq, Libya, and Iran did not respond to economic sanctions but it did decline significantly in Venezuela, suggesting a limited effect on countries with long economic sanction experiences. With the world’s continuous political and economic uncertainty, countries worldwide should not focus on short-term plans but regularly revise and bolster their healthcare financing pool and maintain financing strategies that limit the effect of global political and economic changes.

HIGHLIGHTS

The tension in countries’ relationships and the use of sanctions as escalation have potential ramifications on government healthcare finances.

The effect of the economic sanctions on government healthcare financing was examined.

Majority of government healthcare spending did not respond to the economic sanctions.

Economic sanctions have a limited effect on government healthcare spending in countries with a long history of sanctions compared to those that do not have such an experience.

Introduction

Countries across the world are continuously exposed to the effects of the global deteriorations that result from various reasons including the spread of diseases, economic fluctuations, wars, and geopolitics. The economic sanctions used by powerful countries as a tool to alter foreign policies are another reason that could have moderate-to-severe effects on countries’ economies (Peksen, Citation2019). For example, on the one hand, the economic sanctions imposed on Venezuela in 2006 reduced its gross domestic product (GDP) growth by 1.1% point in 2007 (International Monetary Fund, Citation2023; Seelke, Citation2020). On the other hand, the economic sanctions imposed on Iraq in 1990 (Dyson & Cetorelli, Citation2017) was followed by a 64% fall in its GDP the following year (World Bank, Citation2023a). In 1980, the economy of Iran posed a 21.6% drop in its GDP after the imposition of sanctions in 1979 (Aloosh et al., Citation2019; International Monetary Fund, Citation2023), and the economy of Libya reported a 14.7% decline in its GDP in 1987, a year after sanctions were imposed thereon, while the sanctions imposed in 1992 were followed by a 5.5% reduction in its GDP (Collins, Citation2004; International Monetary Fund, Citation2023). An area that could be significantly affected by economic sanctions is healthcare financing, which in one way or the other has long-term ramifications.

The literature is rich with evidence of the indirect effects of economic sanctions on healthcare financing, including the effect on child mortality (Dyson & Cetorelli, Citation2017; Gibbons & Garfield, Citation1999), mental health (Aloosh et al., Citation2019), life expectancy (Gutmann et al., Citation2021), health of patients with cancer (Shahabi et al., Citation2015), pharmaceutical (Bastani et al., Citation2022; Setayesh & Mackey, Citation2016), COVID-19 (Karimi & Turkamani, Citation2021), and access to healthcare (Asadi‐Pooya et al., Citation2022; Sen et al., Citation2013). Some studies have highlighted the potential effect on government and general healthcare spending (Akbarialiabad et al., Citation2021; Asgardoon & Hosein, Citation2022), while others have investigated the effect of economic sanctions on government healthcare spending (Faraji Dizaji & Ghadamgahi, Citation2019). Moreover, many studies have investigated the effect of the economic sanctions on healthcare with a focus on specific countries such as Syria (Moret, Citation2015), Cuba (Roshan & Abbasir, Citation2014), Haiti (Gibbons & Garfield, Citation1999), and Yugoslavia (Garfield, Citation2001), whereas others have studied the effect among a variety of nations (Faraji Dizaji & Ghadamgahi, Citation2019; Garfield et al., Citation1995; Peksen, Citation2011).

Given the valuable contribution of the literature on the effect of economic sanctions on healthcare, it was found that the immediate effect of sanctions was mostly dismissed, whereby only the periods coming years after the imposition of the sanctions were investigated, and such periods were long enough to imbue effects other than sanctions. Investigations on the periods preceding the imposition of sanctions are also absent, as only one side effect has been the main focus in the literature, that is, the periods after imposing the sanctions. Moreover, the sanction-ending effects still lack considerable evidence in the literature. Furthermore, the effect was investigated among countries with different economic features, some of which had the potential to mitigate the effect by investing more in their main source of financing, such as oil, that other countries lacked, thereby making the effect on countries incomparable.

The paucity of research on the effects of economic sanctions on government healthcare spending creates a scientific gap, and contributing to the literature by investigating them can potentially facilitate the bridging of certain knowledge gaps. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the effect of economic sanctions on government healthcare spending, while considering the immediate impact of sanctions, the effect of terminating sanctions, the periods preceding sanctions, and the effect within countries with similar economic features and sources of financing.

One group of countries with members that have received economic sanctions is the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). In 1960, OPEC was founded with a mission to regulate the oil production policies of its members to stabilise the global oil market and ensure efficient and regular supply to consumers (Kisswani et al., Citation2022). This is accomplished by limiting the oil production of OPEC members to specific levels, where an increase and decrease in their production is subjected to a revision of the market changes and negotiations with the group members (Kisswani et al., Citation2022). Currently, there are 13 official OPEC members, and three more countries have suspended their membership for some time or permanently (OPEC, Citation2023b).

More than half of the active members of OPEC have received economic sanctions (defined as those imposed on governments but not individuals). For example, the earliest economic sanctions imposed on Iran were in 1979 (Aloosh et al., Citation2019), Libya in 1986 (Collins, Citation2004), Iraq in 1990 (Dyson & Cetorelli, Citation2017), Nigeria in 1992 (Sklar, Citation1997), Angola and Congo in 1993 (European Commission, Citation2023; Reliefweb, Citation2000), and Venezuela in 2006 (Seelke, Citation2020). The sanctions on some of these countries were lifted, such as those on Libya, Iraq, and Angola (The United States Department of the Treasury, Citation2023; United Nations; United Nations, Citation2002, Citation2010). Other sanctions were suspended for some time and then resumed again, as was the case of Iran (Aloosh et al., Citation2019). Some countries received it once, such as Venezuela (Seelke, Citation2020), while others received it multiple times, such as Angola, Congo, and Nigeria (Human Rights Watch, Citation1997; Lazanyuk & Diu, Citation2022).

Financing healthcare services in these countries differ but tend to be more privately financed. For example, in Iraq, the public sector provides free healthcare services to citizens, where the constitution ensures citizens’ universal right to healthcare (Jaff et al., Citation2018), and the private sector sublimates curative care but now finances the majority of the system (Al Hilfi et al., Citation2013; World Health Organization, Citation2023b). In Iran, the system is financed via public funds, social healthcare insurance, private insurance, and out-of-pocket (OOP) payments (Dizaj et al., Citation2019; Zare et al., Citation2014), but more than half is privately financed, with OOP payments accounting for a large share (World Health Organization, Citation2023b; Zakeri et al., Citation2015). The healthcare system in Venezuela is financed publicly and privately, with a growing share of OOP payments, which is one of the highest in the world (Atun et al., Citation2015; Roa, Citation2018), same as the healthcare system in Nigeria, where it is financed in different ways, but mostly via OOP payments (Uzochukwu et al., Citation2015). In Libya, the state has been responsible for providing free healthcare services to all citizens since the 1970s, whereafter further regulations took place later to involve the private sector (El Taguri et al., Citation2008); however, since the revolution in 2011, the healthcare system has suffered poor funding and a deep shortage of resources (El Oakley et al., Citation2013), with public finance derived from different governments (Frontieres, Citation2016). In Congo, a variety of actors are involved in financing, including the government, donors, implementing partners, and facilities, but its healthcare system is primarily financed via OOP payments (Laokri et al., Citation2018; Le Gargasson et al., Citation2014). The healthcare system in Angola is principally financed by the government, representing 10% of the government’s total budget, but it is also financed by non-governmental organisations, donors, and private companies (Craveiro & Dussault, Citation2016; International Trade Administration, Citation2022).

Methodology

This study used data from the Global Health Expenditure Database of the WHO. The database provides healthcare data from 2000 to 2020 at the time of this study (World Health Organization, Citation2023b). Within this timeframe, this study investigated the effect of economic sanctions on government healthcare spending, depending on the countries available sanction actions. The sanction actions in this study are defined as the major actions to governments’ sanction programmes imposed, lifted, or both by one or more entities of the United States Department of the Treasury, the UN, or the European Union.

To better capture the effect of economic sanctions on government healthcare spending and ensure reasonable comparison, the study includes OPEC members that meet two criteria: i) received or lifted sanctions while holding an active membership with OPEC in the 21 years covered by the WHO data, and ii) had a minimum of two years before the year of the sanction action and two years after, where all the countries must be active OPEC members during this period. This will allow for the testing of the effect while ensuring that any encountered response to the sanctions by countries, such as overreliance on their main source of income, for example, oil overproduction, is controlled so as not to offset the actual effect of the sanction, a scenario that could otherwise crucially bias the effect of the economic sanctions on government healthcare spending.

Countries that met these criteria included Iran, where sanctions were lifted in 2015 and resumed in 2018 (Aloosh et al., Citation2019); Libya and Iraq, where sanctions were lifted in 2004 and 2010, respectively (United Nations, Citation2010; The United States Department of the Treasury, Citation2023); and Venezuela, which received economic sanctions in 2006 (Seelke, Citation2020). The study is aware that some of these countries have received or have had some sanctions lifted before or after these stated periods, such as those lifted in Iraq in 2003 by the UN (European Commission, Citation2023). However, this study focusses on the major action on sanctions. Moreover, the sanctions imposed on Angola were placed in 1993 (Reliefweb, Citation2000), and more changes on lifting the sanctions were made in 2002 (United Nations, Citation2002), but the country has been an active member of OPEC since 2007 (Kisswani et al., Citation2022); thus, it was excluded for not meeting the study inclusion criteria. Congo was also excluded because sanctions were imposed on it in the 1990s and changes to the sanctions took place in different years before becoming an active OPEC member in 2018 (European Commission, Citation2023; Kisswani et al., Citation2022). In addition, within the WHO 21 covered period, no major actions on the Nigerian sanction programme were observed; thus, it was excluded.

For statistical analysis, the study data were categorised into two groups: pre- and post-economic sanction action. The data turning point was the year when sanctions were imposed or lifted, which was not included in the analysis. Involving this year could have biased either period – pre- or post-sanction – because the timing of the sanction actions within the included countries occurred more often in the middle of the year. Therefore, that part of the year might have included the effect, and the other one might have not. According to the available period of data from the WHO and to equalise periods before and after the sanction actions, the present study investigated the effect of economic sanctions from the perspective of lifting the sanctions in Iraq and Libya. Therefore, the pre-lifting period of the sanctions in Iraq is from 2004 to 2009, and the post-lifting period is from 2011 to 2016, with 2010 as the turning point. In Libya, pre-lifting period is from 2000 to 2003, while post-lifting period is from 2005 to 2008, and 2004 is the turning point. In Venezuela, the study investigated the imposition of sanctions, where the period from 2000 to 2005 is pre-imposing, 2007 to 2012 is post-imposing, and 2006 is the turning point. This study investigated the imposition and lifting of sanctions in Iran. The period from 2013 to 2014 is pre-lifting and that from 2016 to 2017 is post lifting, with 2015 as the turning point. Moreover, 2016 to 2017 is the pre-sanction period, while 2019 to 2020 is the post-sanction period, and 2018 is the turning point.

This study used government healthcare spending as a percentage of total government spending as the primary indicator, reflecting the capacity to demonstrate government spending on healthcare after the sanction action compared to the period before the action. Moreover, the aggregation of government spending on healthcare is appropriate, as it yields a comparison among countries, which permits the investigation of different explanatory variables and institutional systems (Gerdtham & Jönsson, Citation2000). This is different from using absolute values which do not permit such an investigation and is more often used to investigate one country or specific illness (Turner, Citation2017; Zhang et al., Citation2010). In addition, the ratio of government healthcare spending to total government spending is a core indicator of healthcare financing systems, which contributes to explaining the relative weight of total government spending (World Health Organization, Citation2023a). It has also been used extensively in the literature to measure the impact of a policy on health and has been seen as an important variable for policymakers to observe policy effectiveness, efficiency of healthcare programmes, and the development of health outcomes (Edeme et al., Citation2017; Kim & Lane, Citation2013).

This study employed descriptive analysis to analyse the mean changes in government healthcare spending post-sanction actions with spending before the sanction actions. The Wilcoxon – Mann – Whitney test was used to assess the differences in government healthcare spending during the aforementioned periods. This test can measure the significance of the difference between the means within two independent groups even if the sample size is relatively small (Happ et al., Citation2019; Nachar, Citation2008), as is the case in this study. The present study employed a two-sided t-test with significance levels indicated in the results at 1%, 5%, and 10%. The significance value (p-value) of the difference between the two independent samples is reported to indicate the probability of a difference between the two samples if the null hypothesis is true, which is the hypothesis that the difference between samples is zero. The effect of economic sanctions was reported if a significant result was observed in either case of imposing or lifting the sanctions. Statistical analysis was performed using the STATA software version 14.0.

The present study also performed a further analysis on the mean changes in government healthcare spending to GDP in the aforementioned countries, while covering the same periods, which were then compared to the study’s primary indicator to identify any patterns in government healthcare spending. Descriptive analysis was also conducted on government healthcare spending to total government spending and to GDP to analyse the trend in healthcare spending post-sanction actions compared to pre-sanction actions (Haralayya, Citation2021).

Results

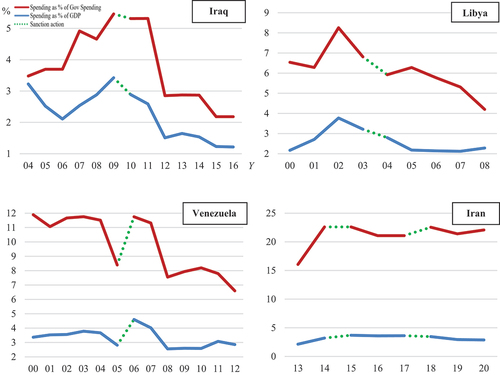

The results of the mean comparison of government healthcare spending to total government spending gave broadly similar significant results to those shown by government healthcare spending to GDPs among all the study countries (see ). Moreover, both indicators showed the same trends within the investigated period for each country (see ).

Table 1. Wilcoxon – Mann – Whitney test results for changes in government healthcare spending.

In Iraq, the results showed that the share of government healthcare spending to total government spending after lifting sanctions declined significantly by 1.2% (p = 0.03) compared to the pre-lifting period (see ). Meanwhile, the proportion of government healthcare spending to Iraq’s GDP declined significantly by 1.1% (p = 0.01) relative to the pre-lifting period. Moreover, the trend of government healthcare spending in both indicators declined after the lifting compared to the prior period (see ).

In Libya, the ratio of government healthcare spending to total government spending in the post-lifting sanction period declined significantly by 1.6% (p = 0.02) compared to the pre-lifting period. Concurrently, the ratio of government healthcare spending to GDP declined significantly by 0.8% (p = 0.08) compared to the pre-lifting period. In addition, the period after lifting the sanctions showed downward trends compared to the prior period.

In Venezuela, the ratio of government healthcare spending to total government spending declined significantly in the post-sanction period by 2.8% (p = 0.01) compared to the pre-sanction period. Meanwhile, the ratio of government healthcare spending to GDP declined significantly by 0.5% (p = 0.10) compared to the pre-sanction period. Moreover, government healthcare spending for both indicators showed declining trends after the sanctions.

In Iran, the ratio of government healthcare spending to total government spending increased by 1.7% (p = 1.00) in the period after lifting sanctions in 2015 compared with the prior period. At the same time, the ratio of government healthcare spending to GDP increased by 0.9% (p = 0.12) compared to the pre-lifting period. In addition, the ratio of government healthcare spending to total government spending increased by 0.6% (p = 0.12) in the post-sanction period in 2018 compared with the prior period. In the same period, the ratio of government healthcare spending to GDP declined by 0.7% (p = 0.12) compared to the pre-sanction period. In addition, both indicators showed increasing trends after the 2015 lifting of sanctions; however, after the 2018 sanctions, only the ratio of government healthcare spending to total government spending increased.

Discussion

The study results showed that the effect of economic sanctions on healthcare spending differed among the countries investigated. With the expected pressure of sanctions or the release of lifting sanctions on government healthcare spending, surprisingly, the majority of the countries have not responded to the economic sanction actions. In Iraq and Libya, the ratio of government healthcare spending to total government spending and GDP showed significant declines in the post-lifting period, while Iran showed stability given the decisions to lift the sanction and impose it afterwards. The only country whose healthcare spending has been affected by the sanctions is Venezuela. This suggests that sanction actions have a limited effect on government healthcare spending in countries with an extensive experience with economic sanctions, which could have allowed them to implement strategies that abate the effects of the world’s ongoing political and economic changes compared to those without experience.

For example, the government healthcare spending in Iran during the period of investigation went through three periods of economic sanctions. However, the ratio of government healthcare spending to total spending and GDP mostly showed stability from 2013 to 2020, ignoring the world rebound after the global financial crisis and the subsequent changes in the petroleum industry (The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, Citation2023a) (see ). The ratio of government healthcare spending to total spending and GDP did not even respond to the outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic that affected the global healthcare system (Ceylan et al., Citation2020; Qin et al., Citation2021), neither did the country’s GDP respond, which unexpectedly increased by 3.3% in 2020 (World Bank, Citation2023a). These suggest that government healthcare spending has become more resilient to global changes, as it has been under sanctions in the past 40 years (Aloosh et al., Citation2019).

In Iraq, the lifting of sanctions was expected to yield an opportunity to increase the ratio of government healthcare spending to total government spending and GDP in the subsequent years. This might be due to its being ranked as one of the highest oil producers among the OPEC members (Statista, Citation2023) and having the world’s highest share of oil revenue to GDP (The Global Economy, Citation2023; World Bank, Citation2023b), especially as its post-lifting period coincided with the world economies rebounding after the global financial crisis. However, no response was reported, which could be attributed to the country’s experience with economic sanctions since 1990 (Dyson & Cetorelli, Citation2017). In addition, the transition of its healthcare system to a more privately funded model that includes individuals could be a contributor to this situation, which has surged significantly since 2012 (Al Hilfi et al., Citation2013; World Health Organization, Citation2023b). The limited response could also be due to the political instability that started in 2011 and escalated in the following years, which prevented its economy from reaching its full potential capacity for production, thereby causing fragility in public financing (Thgeel, Citation2021).

Libya’s government healthcare spending also had a limited response to the lifting of sanctions despite the chance to increase government healthcare spending or achieve more stability before the outbreak of the global financial crisis. The country was also going through more stabilised political and economic conditions after the lifting (Kreiw, Citation2019). However, unexpected declines were observed in both indicators. This may be because government healthcare spending has been in economic sanctions since 1987, thereby strengthening its resilience to political and economic changes at national and international levels (Collins, Citation2004).

On the contrary, Venezuela was the only country that showed a decline in the ratio of government healthcare spending to total government spending and GDP after the lifting of the sanctions. Conversely, the share of private healthcare spending to total healthcare spending increased simultaneously (World Health Organization, Citation2023b). This showed that the government financing system was rather unable to maintain the healthcare spending during economic sanctions. This could be attributed to the government has had no experience in dealing with economic sanctions. Although the effect could also be due to the global financial crisis, the government healthcare spending of the two study indicators did not report higher spending throughout the six years after the sanction compared to the prior period, even before the outbreak of the crisis and at the time when the world started to recover.

Some previous studies have referred to the increase in government healthcare spending as a percentage of the GDP to the decrease in GDP, which can be contrariwise to government healthcare spending (Faraji Dizaji & Ghadamgahi, Citation2019). First, this study controlled for such an effect by evaluating the ratio of government healthcare spending to total government spending and GDP, where the results were approximately the same (see ). Moreover, the study conducted a further investigation on both indicators of the present study with governments’ actual healthcare spending and countries’ GDP. The investigation revealed that actual government spending and GDP had a limited effect on the trends of government healthcare spending to total government spending and GDP (The Country Economy, Citation2023; World Bank, Citation2023a; World Health Organization, Citation2023b). The only government healthcare spending that responded differently to the government’s total spending was Libya, although the contrary response was very low due to small changes in total government spending (The Country Economy, Citation2023; World Health Organization, Citation2023b). Moreover, the contrary response of the ratio of government healthcare spending to GDP was also low and limited to the pre-lifting period of the sanctions (World Health Organization, Citation2023b); World Bank, Citation2023a).

In Iran, the ratio of government healthcare spending to total government spending between 2013 and 2020 mostly remained at a 20% level with marginal increases or decreases, given that the government showed high and continuous increases in its total spending in that period (The Country Economy, Citation2023; World Health Organization, Citation2023b). Meanwhile, the ratio of government healthcare spending to GDP was mostly stable at levels between 3% and 3.5%, given the fluctuation of the GDP, where spending did not follow contrary trends (World Bank, Citation2023a; World Health Organization, Citation2023b). Similar results were observed in Iraq. The ratio of government healthcare spending to total government spending and GDP mostly followed the same trend as the government’s total spending and GDP or reported no changes, except in 2012, when the ratio of government healthcare spending to total government spending decreased by 2.5% due to the high increase in total government spending (see ) (The Country Economy, Citation2023; World Bank, Citation2023a; World Health Organization, Citation2023b). The same finding was observed in the government healthcare spending to GDP ratio in 2012 and 2016, where spending increased at a slower pace (1% for both) due to the high increase in GDP. In Venezuela, government healthcare spending also had no clear contrary response to the government’s total spending and GDP trends but followed the same trend or reported no changes (The Country Economy, Citation2023; World Bank, Citation2023a; World Health Organization, Citation2023b).

Conclusion

This study examined the effect of the economic sanction actions on OPEC countries’ government healthcare spending, of which had received economic sanctions. It was evident in the study that Iraq, Libya, and Iran did not respond to the sanction actions, which was attributable to their long experience with economic sanctions, where government healthcare spending either declined after the lifting of the sanctions or maintained nearly the same levels as of the time of imposing or lifting sanctions. These countries could have had the opportunity, at the time of being under sanctions, to set strategies that yielded them the resilience to be less affected by the surrounding political and economic changes. In contrast, Venezuela was the only country that struggled to maintain its levels of government healthcare spending post-sanction compared to its pre-sanction period, as it was the country’s first experience with sanctions. Consequently, government healthcare spending declined after the sanctions, with an increased share of private spending at the same time. Such increases in private spending might have temporarily alleviated the pressure on government spending, which would have had adverse long-term consequences. The short-sighted nature of government financing without continuous revision measures to resources in line with the surrounding political and economic changes is likely to make government healthcare spending sometimes fragile to the world’s ongoing changes and exposed to shocks that may worsen healthcare conditions over time, unless such patterns are reversed. The global economic uncertainty caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine, and the rising world inflation with its respective effects on global financial systems might put governments’ healthcare spending under more strain. Economies may also face more challenges as the demand for healthcare increases owing to ageing, an increase in chronic diseases, and population growth, which would require more healthcare financing. The results of this study suggest that countries worldwide, especially those with a high percentage of government healthcare spending, should consciously revise and bolster their government healthcare financing pools. The present study also cautions against focusing on short-term plans by transferring healthcare spending burdens to the private sector and over-relying on few unsustainable resources but maintaining more financing strategies that reinforce their resilience to the world’s continuous political and economic changes.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Salem Al Mustanyir

Salem Al Mustanyir, a senior economist, brings a wealth of experience from diverse national and international organizations, universities, and companies. His extensive expertise encompasses a range of fields, including economics, accounting, finance, investment, insurance, risk management, business intelligence, data analytics, and artificial intelligence. Dr. Al Mustanyir’s research spans a broad spectrum, addressing key areas such as health economics, sustainable finance, economic of data, energy and oil markets, smart cities, artificial intelligence investment, labor market dynamics, policy impact assessment, and the formulation of performance indices for both public and private sectors

References

- Akbarialiabad, H., Rastegar, A., & Bastani, B. (2021). How sanctions have impacted Iranian healthcare sector: A brief review. Archives of Iranian Medicine, 24(1), 58. https://doi.org/10.34172/aim.2021.09

- Al Hilfi, T. K., Lafta, R., & Burnham, G. (2013). Health services in Iraq. The Lancet, 381(9870), 939–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60320-7

- Aloosh, M., Salavati, A., & Aloosh, A. (2019). Economic sanctions threaten population health: The case of Iran. Public Health, 169, 10–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2019.01.006

- Asadi‐Pooya, A. A., Nazari, M., & Damabi, N. M. (2022). Effects of the international economic sanctions on access to medicine of the Iranian people: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics, 47(12), 1945–1951. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpt.13813

- Asgardoon, M. H., & Hosein, M. (2022). Adverse impacts of imposing international economic sanctions on health. Archives of Iranian Medicine, 25(3), 182–190. https://doi.org/10.34172/aim.2022.31

- Atun, R., De Andrade, L. O. M., Almeida, G., Cotlear, D., Dmytraczenko, T., Frenz, P., Garcia, P., Gómez-Dantés, O., Knaul, F. M., Muntaner, C., de Paula, J. B., Rígoli, F., Serrate, P. C. F., & Wagstaff, A. (2015). Health-system reform and universal health coverage in Latin America. The Lancet, 385(9974), 1230–1247. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61646-9

- Bastani, P., Dehghan, Z., Kashfi, S. M., Dorosti, H., Mohammadpour, M., & Mehralian, G. (2022). Challenge of politico-economic sanctions on pharmaceutical procurement in Iran: A qualitative study. Iranian Journal of Medical Sciences, 47(2), 152.

- Ceylan, R. F., Ozkan, B., & Mulazimogullari, E. (2020). Historical evidence for economic effects of COVID-19 (Vol. 21). Springer.

- Collins, S. D. (2004). Dissuading state support of terrorism: Strikes or sanctions? (An analysis of dissuasion measures employed against Libya). Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 27(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/10576100490262115

- The Country Economy. (2023). General Government expenditure. The Country Economy. Retrieved March 24, 2023, https://countryeconomy.com/government/expenditure

- Craveiro, I., & Dussault, G. (2016). The impact of global health initiatives on the health system in Angola. Global Public Health, 11(4), 475–495. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2015.1128957

- Dizaj, J. Y., Anbari, Z., Karyani, A. K., & Mohammadzade, Y. (2019). Targeted subsidy plan and Kakwani index in Iran health system. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 8(1), 98. https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_16_19

- Dyson, T., & Cetorelli, V. (2017). Changing views on child mortality and economic sanctions in Iraq: A history of lies, damned lies and statistics. BMJ Global Health, 2(2), e000311. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000311

- Edeme, R. K., Emecheta, C., & Omeje, M. O. (2017). Public health expenditure and health outcomes in Nigeria. American Journal of Biomedical and Life Sciences, 5(5), 96–102. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajbls.20170505.13

- El Oakley, R. M., Ghrew, M. H., Aboutwerat, A. A., Alageli, N. A., Neami, K. A., Kerwat, R. M., Elfituri, A. A., Ziglam, H. M., Saifenasser, A. M., Bahron, A. M., Aburawi, E. H., Sagar, S. A., Tajoury, A. E., & Benamer, H. T. S. (2013). Consultation on the Libyan health systems: Towards patient-centred services. Libyan Journal of Medicine, 8(1), 20233. https://doi.org/10.3402/ljm.v8i0.20233

- El Taguri, A., Elkhammas, E., Bakoush, O., Ashammakhi, N., Baccoush, M., & Betilmal, I. (2008). Libyan national health services the need to move to management-by-objectives. Libyan Journal of Medicine, 3(3), 113–121. https://doi.org/10.4176/080301

- European Commission. (2023). EU Sanctions Map. Estonian Presidency of the Council of the EU. Retrieved March 23, 2023, https://www.sanctionsmap.eu/#/main/page/legend

- Faraji Dizaji, S., & Ghadamgahi, Z. S. (2019). The impact of economic sanctions on public health expenditure (evidence of developing resource-exporting countries). Economics Research, 19(75), 71–107.

- Frontieres, M. S. (2016). Health system in a state of hidden crisis. Medecins Sans Frontieres. Retrieved March 23, 2023, https://www.msf.org/libya-health-system-state-hidden-crisis

- Garfield, R. (2001). Economic sanctions on Yugoslavia. The Lancet, 358(9281), 580. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05713-0

- Garfield, R., Devin, J., & Fausey, J. (1995). The health impact of economic sanctions. Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 72(2), 454.

- Gerdtham, U.-G., & Jönsson, B. (2000). International comparisons of health expenditure: Theory, data and econometric analysis. In Anthony J. Culy & Joseph P. Newhouse (Eds.), Handbook of health economics (Vol. 1, pp. 11–53). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1574-0064(00)80160-2

- Gibbons, E., & Garfield, R. (1999). The impact of economic sanctions on health and human rights in Haiti, 1991–1994. American Journal of Public Health, 89(10), 1499–1504. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.89.10.1499

- The Global Economy. (2023). Oil revenue - country rankings. The global economy. Retrieved March 24, 2023, https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/rankings/oil_revenue/

- Gutmann, J., Neuenkirch, M., & Neumeier, F. (2021). Sanctioned to death? The impact of economic sanctions on life expectancy and its gender gap. The journal of development studies, 57(1), 139–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2020.1746277

- Happ, M., Bathke, A. C., & Brunner, E. (2019). Optimal sample size planning for the Wilcoxon‐Mann‐Whitney test. Statistics in medicine, 38(3), 363–375. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.7983

- Haralayya, B. (2021). Study on trend analysis at John Deere. Iconic research and engineering journals, 5(1), 171–181.

- Human Rights Watch. (1997). The role of the international community. Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/legacy/reports/1997/nigeria/Nigeria-10.htm

- International Monetary Fund. (2023). Real GDP growth, annual percent change. IMF. Retrieved March 22, 2023, https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDP_RPCH@WEO/OEMDC/ADVEC/WEOWORLD

- International Trade Administration. (2022). Angola – country commercial guide, infrastructure in healthcare sector. International trade administration. Retrieved March 23, 2023, https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/angola-infrastructure-healthcare-sector

- Jaff, D., Tumlinson, K., & Al-Hamadan, A. (2018). Challenges to the Iraqi health system call for reform. Journal of health systems, 3(2), 9–12.

- Karimi, A., & Turkamani, H. S. (2021). US-imposed economic sanctions on Iran in the COVID-19 crisis from the human rights perspective. International journal of health services, 51(4), 570–572. https://doi.org/10.1177/00207314211024912

- Kim, T. K., & Lane, S. R. (2013). Government health expenditure and public health outcomes: A comparative study among 17 countries and implications for US health care reform. American international journal of contemporary research, 3(9), 8–13.

- Kisswani, K. M., Lahiani, A., & Mefteh-Wali, S. (2022). An analysis of OPEC oil production reaction to non-OPEC oil supply. Resources policy, 77, 102653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2022.102653

- Kreiw, R. (2019). Impact of the political instability on the Libyan economy. Knowledge-international journal, 31(1), 61–67. https://doi.org/10.35120/kij310161k

- Laokri, S., Soelaeman, R., & Hotchkiss, D. R. (2018). Assessing out-of-pocket expenditures for primary health care: How responsive is the democratic Republic of Congo health system to providing financial risk protection? BMC health services research, 18(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3211-x

- Lazanyuk, I. V., & Diu, D. M. (2022). Angola’s economy under sanctions: Problems and solutions. R-economy, 8(3), 208–218. https://doi.org/10.15826/recon.2022.8.3.017

- Le Gargasson, J.-B., Mibulumukini, B., Gessner, B. D., & Colombini, A. (2014). Budget process bottlenecks for immunization financing in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Vaccine, 32(9), 1036–1042. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.12.036

- Moret, E. S. (2015). Humanitarian impacts of economic sanctions on Iran and Syria. European security, 24(1), 120–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/09662839.2014.893427

- Nachar, N. (2008). The Mann-Whitney U: A test for assessing whether two independent samples come from the same distribution. Tutorials in quantitative methods for psychology, 4(1), 13–20. https://doi.org/10.20982/tqmp.04.1.p013

- The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries. (2023a). OPEC basket price. OPEC. Retrieved March 23, 2023, https://www.opec.org/opec_web/en/data_graphs/40.htm

- The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries. (2023b). OPEC brief history. OPEC. Retrieved February 23, 2023, https://www.opec.org/opec_web/en/about_us/24.htm

- Peksen, D. (2011). Economic sanctions and human security: The public health effect of economic sanctions. Foreign policy analysis, 7(3), 237–251. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-8594.2011.00136.x

- Peksen, D. (2019). When do imposed economic sanctions work? A critical review of the sanctions effectiveness literature. Defence and peace economics, 30(6), 635–647. https://doi.org/10.1080/10242694.2019.1625250

- Qin, X., Godil, D. I., Khan, M. K., Sarwat, S., Alam, S., & Janjua, L. (2021). Investigating the effects of COVID-19 and public health expenditure on global supply chain operations: An empirical study. Operations management research, 15(1–2), 195–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12063-020-00177-6

- Reliefweb. (2000). The UN sanctions committee on angola: Lessons learned? United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). Retrieved 23-03-2023, from https://reliefweb.int/report/angola/un-sanctions-committee-angola-lessons-learned

- Roa, A. C. (2018). Sistema de salud en Venezuela: ¿un paciente sin remedio? cadernos de saude publica, 34(3). https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311x00058517

- Roshan, N. A., & Abbasir, M. (2014). The impact of the US economic sanctions on health in Cuba. International journal of resistive economics, 2(4), 20–37.

- Seelke, C. R. (2020). Venezuela: Overview of US sanctions. Current politics and economics of south and central america, 13(1), 21–27.

- Sen, K., Al-Faisal, W., & AlSaleh, Y. (2013). Syria: Effects of conflict and sanctions on public health. Journal of public health, 35(2), 195–199. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fds090

- Setayesh, S., & Mackey, T. K. (2016). Addressing the impact of economic sanctions on Iranian drug shortages in the joint comprehensive plan of action: Promoting access to medicines and health diplomacy. Globalization and health, 12(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-016-0168-6

- Shahabi, S., Fazlalizadeh, H., Stedman, J., Chuang, L., Shariftabrizi, A., & Ram, R. (2015). The impact of international economic sanctions on Iranian cancer healthcare. Health policy, 119(10), 1309–1318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2015.08.012

- Sklar, R. L. (1997). An elusive target: Nigeria fends off sanctions. Polis: revue camerounaise de science politique, 4(2), 19–38.

- Statista. (2023). Daily production of crude oil in OPEC countries from 2012 to 2021. Retrieved March 23, 2023, https://www.statista.com/statistics/271821/daily-oil-production-output-of-opec-countries

- Thgeel, A. (2021). Ten years after the arab spring political and security refelction in iraq friedrich-ebert-stiftung. Retrieved March 24, 2023, https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/amman/17676.pdf

- Turner, B. (2017). The new system of health accounts in Ireland: What does it all mean? Irish journal of medical science, 1971(186), 533–540. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-016-1519-2

- United Nations. (2002). Angola: security council lifts sanctions against UNITA. https://news.un.org/en/story/2002/12/53702-angola-security-council-lifts-sanctions-against-unita

- United Nations. (2010). Security Council takes action to end iraq sanctions, terminate oil-for-food programme as members recognize ‘Major changes’ Since 1990. Retrieved March 23, 2023, https://press.un.org/en/2010/sc10118.doc.htm

- The U.S. Department of the Treasury. (2023). U.S. announces aasing and lifting of sanctions against libya treasury to issue general license lifting much of economic embargo. United States Department of the Treasury. Retrieved March 23, 2023, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/js1457

- Uzochukwu, B. S., Ughasoro, M., Etiaba, E., Okwuosa, C., Envuladu, E., & Onwujekwe, O. (2015). Health care financing in Nigeria: Implications for achieving universal health coverage. Nigerian journal of clinical practice, 18(4), 437–444. https://doi.org/10.4103/1119-3077.154196

- World Bank. (2023a). GDP growth (annual %). Retrieved March 22, 2023 https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG

- World Bank. (2023b). The world bank in iraq. Retrieved March 24, 2023, https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/iraq/overview

- World Health Organization. (2023a). General government expenditure on health as a percentage of total expenditure on health. World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved March 23, 2023, https://www.who.int/data/gho/indicator-metadata-registry/imr-details/92

- World Health Organization. (2023b). Global health expenditure database. World Health Organization (WHO). Retrieved March 23, 2023, https://apps.who.int/nha/database/Select/Indicators/en

- Zakeri, M., Olyaeemanesh, A., Zanganeh, M., Kazemian, M., Rashidian, A., Abouhalaj, M., & Tofighi, S. (2015). The financing of the health system in the Islamic Republic of Iran: A national health account (NHA) approach. Medical journal of the islamic republic of iran, 29, 243. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264183896-en

- Zare, H., Trujillo, A. J., Driessen, J., Ghasemi, M., & Gallego, G. (2014). Health inequalities and development plans in Iran; an analysis of the past three decades (1984–2010). International journal for equity in health, 13(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-13-42

- Zhang, P., Zhang, X., Brown, J., Vistisen, D., Sicree, R., Shaw, J., & Nichols, G. (2010). Global healthcare expenditure on diabetes for 2010 and 2030. diabetes research and clinical practice, 87(3), 293–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2010.01.026