ABSTRACT

Codesigning public library spaces is often limited to consulting with end-users rather than giving them a role as actual co-designers. This article advocates for more genuine codesign of public library spaces and critically examines the prevalent challenges in achieving true codesign in public library developments. The article introduces a two-year Australian Research Council Linkage research project, ‘Designing for Communities with Communities’. The project aims to provide public library staff with a set of codesign tools they can adapt for their own particular projects. Using comparative case studies, the project will also identify the challenges of integrating codesign into the development of public library spaces, and key factors in the effectiveness of projects that seek their communities’ inputs and engagement. This article introduces the theory of participatory and codesign, and sets out the basic conceptual framework for the project. It also reports on its initial stages, including preliminary interviews with key protagonists and preliminary user surveys about existing spaces. Moreover, the article discusses the design of the case studies’ community workshops, where most of the actual codesigning will take place, with an extensive discussion and analysis of the activities that could be included in these workshops.

Introduction

Few library staff would dispute that it is generally beneficial to involve end-users in the design of new libraries, or new library services for that matter, but the concept of codesign goes further than this, and while library managers sometimes claim that their new space, or their new service, has been ‘codesigned’, it is not always clear that the actual designing has in fact been done by the users as much as by the library staff and other professionals, such as architects. Indeed, the evidence often suggests otherwise. For instance, in our preliminary research (Wakeling et al., Citation2022), we found that end-user involvement in a sample of public library development projects was mostly limited to a consulting role in their early or later stages, while library staff were more likely to be given the opportunity to suggest design changes at various points in the design process, but even they were unlikely to have an equal say in the final decisions and rarely would they codesign in the purer sense of initiating, or co-initiating, the design itself. Although the cases fell at different points on the consultation-codesign continuum (see e.g. below), mostly it was the architects who directed the process that occurred between them obtaining their design brief and them signing off on their solution to it. In between, end-users might be surveyed early on, and/or asked, as represented perhaps by a focus group, for feedback on a prototype, while the library staff might discuss progress with the architect on a more frequent basis, but generally the design professional would be the primary ‘gatekeeper’, with this power linked to their contractual responsibility to deliver the design, not merely to help deliver it.

However, the theory of participatory design or codesign (for the purposes of this paper, we use the terms codesign and participatory design interchangeablyFootnote1) does not delegate all responsibility, and authority, to the design professional. Instead, the professionals share power with the users and potential users of the thing-to-be-designed, and with its other stakeholders: they are all co-designers (Bratteteig & Wagner, Citation2014). Professionals and non-professionals can both make valuable contributions, based on complementary knowledge and skills: the design professionals’ process and design knowledge provide frames of reference, while users bring their ‘basic’ knowledge of the thing-to-be-designed to bear on the project (Drain & Sanders, Citation2019). In collaboration, experts in design and experts in use can produce a better, more user-oriented design, as well as one with which its users are likely to be more engaged (Simonsen & Robertson, Citation2012).

As Simonsen and Robertson (Citation2012) outline, the participatory design movement can be traced back to the political and technological developments of the 1960s, when increasingly mechanised and corporate work environments were seen to be at odds with growing demands for people to have more of a say in how they worked, as well as how they lived more generally; the codesign of new work environments that prioritised the user rather than the technology has since been followed by a vast array of other participatory design applications, including many outside of the work environment, be they products, services, systems or spaces: most things that can be designed, seemingly. The democratic dimension of participatory design, however, has made public-oriented projects a particular target of participatory design. Examples include the design of a wide range of public services and systems, as well as instances from the built environment, such as certain public housing developments and community spaces (Luck, Citation2018), as well as a few public libraries (see e.g. our literature review below), notwithstanding the observation above that most public libraries have not been codesigned to this degree.

The philosophy behind participatory design might be thought to especially fit with the mission of the public library. While it may legally belong to a local government, in a broader sense it belongs to the community it serves, and in this sense the community and its members should have, according to the philosophy, a direct say in its design and creation, even more so than the library staff, who can be viewed as the ‘custodians’ of the library. Moreover, the public library mission typically involves (amongst other things) the fostering of community engagement and participation, through the provision of inclusive, democratic spaces for social interaction, knowledge sharing and civic engagement (Johnston et al., Citation2023). The design of such spaces would thus seem to virtually necessitate participation.

However, there is theory, and then there is practice. The fairly large body of literature concerned with the implementation of participatory design is itself indicative of the challenges it entails (Bjögvinsson et al., Citation2012; Simonsen & Robertson, Citation2012). Participatory design is not simply design with a high degree of citizen participation. Traditional design methods do not always ‘make sense’ to non-professional participants, and since its inception participatory design has been occupied with developing new methods that do, with ‘engaging hands-on design devices, like mock-ups and prototypes and design games that helped maintain a family resemblance with the users’ everyday practice, and that supported creative, skillful participation and performance in the design process’ (Bjögvinsson et al., Citation2012, p. 105). Accordingly, it has evolved its own epistemological worldview, which is reflected and supported by an extensive catalogue of activities and methods (Clarke, Citation2020).

Nevertheless, lay participation can be easier to facilitate in some cases than in others. Ultimately, the thing to be designed is going to be a major factor. It may be easier to involve end-users if the thing is relatively straightforward for the non-professional to comprehend; a codesign project is also likely to be more successful if the end-users are heavily invested in the new thing, be it a product or service. In the corporate context, collaborators have more of an obligation to participate (staff are paid to do so). Things that are, or can be, very multi-faceted and are, or can be, used in many different ways are more likely to generate conflicting approaches and solutions, particularly if a wide cross-section of users are involved in the codesign.

Given these and other factors, it is perhaps not all that surprising that the design of public library spaces tends to sit more toward the consultation end than the pure codesign end of the continuum. Public libraries are increasingly complex ecosystems, used in many different ways for many different purposes. Models for the design of learning environments alone need to factor in a large number of inter-related qualities (Mäkelä & Helfenstein, Citation2016), and public libraries aim to provide other kinds of spaces as well as learning environments. Yet, they also tend to be used in relatively casual ways, and there is sometimes a tendency for patrons to take their library for granted, something is just there (on the way to the shops or after the school pickup, for instance). In any case, buildings take a long time (and plenty of money) to construct and cannot be readily pulled down and started again; they also rely on a high degree of professional expertise to ensure they are safe and functional.

There are also other reasons why things like public libraries may be challenging to codesign, beyond the nature of the thing itself. Botero et al. (Citation2020) have pointed out that it often takes much more than effective methods ‘to get participatory and co-design done’, citing a case study involving the design of a public library to demonstrate this. Ultimately, the success of such large-scale projects also depends very much on the effectiveness of a good deal of ‘mundane and routine work’, including the logistical work needed to support the actual codesign activities, such as the recruitment of the participants and the selection of the venue, as well as the effectiveness of certain ‘strategic work’, which may involve aligning the project with the strategic goals of the (parent) organisation, effecting organisational change, and achieving suitable power-sharing arrangements. Much of this work is unlikely to be straightforward in the case of the public library environment, with cash-strapped paymasters and diverse stakeholder interests. In the case of the design of public library spaces, the ‘professionalism’ of both the library staff and the architect may make the power-sharing arrangements a particular challenge: in some circumstances, there may be a reluctance to share power with non-professionals, with this being viewed as a relinquishing of hard-earned professional status (Johnston et al., Citation2023). As well as the context of the codesign, and the methods employed, it should also be noted that the effectiveness of the codesign will additionally depend on the protagonists themselves, according to the skills, knowledge and outlooks they bring to the process (Drain & Sanders, Citation2019).

Nevertheless, we take the view that public library spaces could be more codesigned, even if there is a practical and political limit to the ideal. Accordingly, we applied for and were successful in obtaining a Linkage Project grant from the Australian Research Council to conduct a two-year project, titled ‘Designing for Communities with Communities’, to investigate how public libraries, at least in Australia, could accommodate more community input (i.e. participation) into the design of their new and refurbished spaces. Partnering with the Public Library Services team at the State Library of New South Wales, and three public library networks from across the state, we will be road-testing various codesign activities that will go beyond, if successful, the usual level of community input in library development projects.

We should point out here that we are not aiming to provide a ‘silver bullet’ for all library co-designers, nor to identify the ‘best’ and most magical of codesign formulae, as the design of codesign, just like codesign itself, is an art more than a science, and different codesign interventions will work better in some particular cases than they will in others, even amongst projects focusing specifically on public library spaces. We do aim, however, to provide public library staff with a set of tools they can adapt for their own particular projects, and to identify key factors in the success or otherwise of projects that seek both their communities’ inputs and engagement. While the codesign of libraries, even in a purer sense, is not a completely new topic, the amount of research into its implementation is quite sparse, and especially so in relation to Australian library projects. Taking a comparative case studies approach, our project’s formal objectives are, as per the project’s website (https://librariesresearchgroup.csu.domains/current-projects/co-designing-public-libraries), to:

map the challenges of integrating codesign into the development of public library spaces

road-test the application of codesign activities to the design of public library spaces

identify the factors that affect the codesign of public library spaces of different scope or scale

explore community members’ visions for public library spaces in a COVID-changed world.

By addressing these objectives, the project aims to develop a framework for the codesign of public library spaces in Australia, containing, as per its website, ‘the principles and tools needed for public library managers to raise the level of community involvement in the development of future library spaces from that of consultation to that of co-design’. The project’s three case studies involve quite different scales of spatial development: a library refurbishment that could perhaps be termed an ‘update’; a refurbishment for a library that has not been reconfigured for a long time, and that might be termed an ‘overhaul’; and a brand new building for a library that serves an entire local government area, a project of a different scale and size altogether. The three cases also vary in relation to their communities and user base. One is a branch library covering a particular district in western Sydney; another a library serving a larger suburban area, also located in western Sydney; and the third is a branch library serving a suburb of a regional city in western New South Wales. This article introduces the theory of participatory and codesign, and sets out the basic conceptual framework our project will be using, with reference to this theory and to design theory more generally. It will provide a review of the research literature on public library codesign, and an overview of the ways and extent to which the professional guides on library planning cover end-user involvement. It then reports on the initial stages of our project, including the preliminary interviews with the key protagonists in the two library refurbishments, the corresponding preliminary user surveys about the existing spaces, and, in an extensive discussion, the design of the community workshops, in which, for our project, most of the actual codesigning will take place. The discussion of the workshops is based on an extensive environmental scan and analysis of codesign activities that could be applied to public library space development, identifying the various functions of these activities and various criteria for their selection, with reference to our conceptual framework and model of the design process. This initial development of a ‘toolkit’ of codesign activities will provide not only an application specifically for public libraries, but also a deeper analytical understanding of its components than has typically been offered. (Dogunke (Citation2020), for instance, has recently provided a very brief ‘catalogue’ of activities that could be used in academic library settings, and indicates in which stages of her model of the codesign process they could be applied, but does not distinguish between different functions within or around these basic stages, nor discusses the activities’ applicability in a comparative framework.) We conclude by outlining our plans for the remaining stages of the project.

Participation and the Design Process

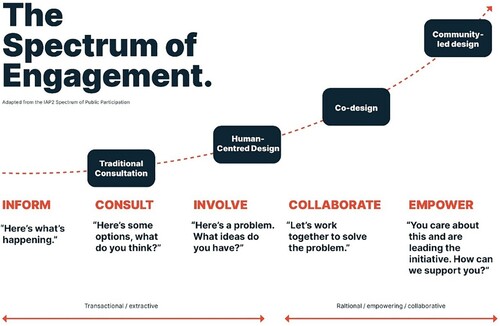

Participation can be an element of many processes that might otherwise be given over completely to professionals. This includes the process of design itself, as well as activities that occur beforehand (e.g. establishing the design brief) and afterwards (e.g. evaluating the realised design). It can also involve different kinds of non-professionals, so that, for instance, library staff involvement in architectural design can be regarded as participatory, in as much as their involvement in this activity, while it pertains specifically to their role, is not as a professional designer. However, participatory design is more commonly associated with the involvement of the end-user, which in the case of public libraries, is the public. This kind of participation is sometimes termed ‘community participation’ or ‘citizen participation’ (Caixeta et al., Citation2019). Participation, especially community participation, also varies considerably in its degree. One of the first attempts to categorise the different levels was Arnstein’s ‘ladder’ (Citation1969) of citizen participation, which has as its bottom rung manipulatory practices aimed at educating participants to achieve public support. The middle rungs are degrees of participatory tokenism, informing, consultation and placation, in which a few representatives of the public are co-opted as advisors, leaving to the power holders the right to judge a design’s legitimacy or feasibility. The top rungs involve partnerships and genuine collaborations, delegated power, and citizen control. The International Association for Public Participation (Citation2018) has constructed its own ‘spectrum of public participation’, which distinguishes five levels of participation: informing, consulting, involving, collaborating, and empowering. It has been adapted by Portable Australia for its ‘spectrum of engagement’, as per . A review of the different participation scales has been published by Caixeta et al. (Citation2019).

Although the levels of participations may well vary across an entire library planning project, in general we are aiming to take public library codesign to the level of collaboration. At present, we contend that participation in these projects tends to go no higher than ‘involvement’, at best.

Conceptual Framework

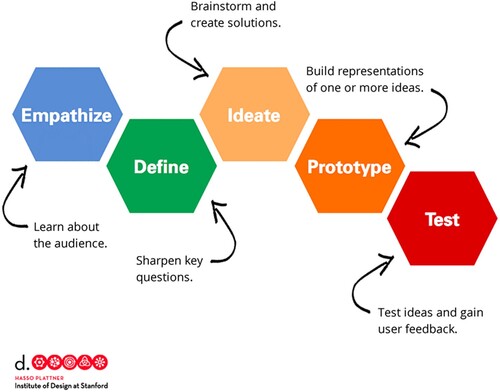

To provide a framework for our project’s codesigning processes, we have decided to adopt a standard model of the design process, or at least of the ‘design thinking’ process. The design thinking movement has quite close ties with the codesign and participatory design traditions, and usually involves a strong element of what design thinkers often term ‘human-centred design’. The term was popularised in the 1990s and 2000s by a number of advocates, including the founders of the IDEO company, which has continued to be influential in the movement’s development and reach. Indeed, the company has developed a design thinking toolkit specifically for libraries (http://designthinkingforlibraries.com), which includes activities and advice for the development and redevelopment of library services generally (including their spaces), although not all of the activities are necessarily participatory at the level of the end-user (e.g. that described at http://designthinkingforlibraries.com/journey-mapping). Nevertheless, all the activities are focused on thinking about the human needs for, and impact of, whatever is being designed. As well as an emphasis on the users and indeed all the human stakeholders associated with a given design (users or otherwise), design thinking also stresses the importance of iteration throughout the design process, and the idea that it is an ongoing process. Probably most design theorists would not much dispute the basic tenants of design thinking in relation to what it says about the process; its impact has been more around its application to a wide range of problems, including so-called ‘wicked problems’, in domains that have not traditionally embraced design-based approaches, such as business and public administration, and, to a much more modest degree, librarianship (Clarke, Citation2020). In relation to libraries, design thinking has been advocated by a number of commentators, including Blair (Citation2023), Bignoli and Stara (Citation2020), Clarke (Citation2020), and Meier and Miller (Citation2016), as an approach that can be effectively applied to librarianship in general. In that vein, the IDEO ‘Design Thinking for Libraries’ toolkit (Citation2015) contains case studies describing its use for the development of both services and spaces. As a toolkit, it appears to be aimed at ‘infrastructuring’, or design-after-design (Bjögvinsson et al., Citation2012), and the modification of services, spaces, and technology, rather than for, say, large-scale construction. There are a number of models of the design thinking process, all of which map quite closely, consisting of between three and six distinct design phases (Clarke, Citation2020). We adopted one of the most popular for our project, namely the model developed by the Stanford d.school (https://dschool.stanford.edu/resources), which is presented in . Bearing in mind that the progression should ultimately be circular, with the last phase feeding into a new first phase, we see that the first phase of a new design project should, according to the model, be about deep diving into what the end-users are currently experiencing. As well as empathy, this is typically going to involve research, and is sometimes labelled ‘discovery’. It is about getting into the user’s mind, and identifying the problems from their point of view, which leads onto the second phase in the process, i.e. ‘define’. Here, the problem or task crystalises, and sets the objective for the designing itself. Next, comes the ideation phase, in which ideas to solve the problem are generated and considered. Then, prototypes are created based on the favoured ideas, to explore their efficacy. Finally, once a prototype is settled upon, the design is implemented, and tested. It is important to note that the whole process can involve many iterations, so that the sequencing is usually not unilinear: prototypes may fail, for instance, in which case the designer would need to return to an earlier phase.

Figure 2. Design thinking phases.

Source: Stanford d.school. Accessed via https://dschool.stanford.edu/resources. Used with permission.

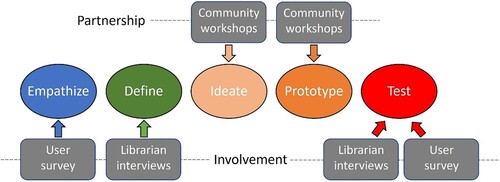

In theory, end-users can participate in all phases, to some level, although in conventional design they do not necessarily participate at all in certain phases. Outside of participatory design, user input is typically minimal in the prototyping phase and can often be minimal in the ideation and ‘define’ phases too. On the other hand, users are generally quite heavily involved in the first and last phases, where their inputs can be more easily captured. In our project, however, we will be looking to make community members ‘partners’ across the central two phases of the process, i.e. the ideation and prototyping phases, as well as involve them heavily in the first and last phases (see ). For the first two of our case studies, we have already conducted preliminary user surveys that directly support the discovery or ‘empathise’ phase, whilst the preliminary interviews we have conducted with the library staff involved in these case studies have explored the second phase, i.e. in which the task is defined. Later, at the other end of the project, we will be conducting another round of user surveys to evaluate (or ‘test’) the designs, and their realisations, as well as following up with the library staff, in further interviews, to gauge their own assessments. In between, we will be hosting a program of community workshops in each of the cases, to facilitate a collaborative approach to both the ideation and prototyping phases of the process.

Literature Review

The scholarly literature is not replete with discussions of how to codesign libraries. Nonetheless, a smattering of case studies of participatory design projects involving library users have been published, though the majority of these pertain to the development of particular library services or to academic libraries (or both), rather than public library spaces. More likely is the construction of a new public library building to be reported in the professional literature, in which case ‘codesign’ might be mentioned as a feature of the planning process, but rarely in a way that reveals exactly what is meant by this or what was done in its name. Yet even its mention suggests that some community input may well have been involved, which does not appear to always be the case: remarkably, Ferguson (Citation2017) found that 32% of public library projects between 2009 and 2011 that he sampled did not attempt to solicit any input from users. Those case studies of public library design and development that have been published in LIS journals have addressed various topics, including, for instance, the development’s functional innovations, but others have considered the project’s process and its management, and of these most have had something to say about the involvement of end-users. It is these case studies that we summarise here, but after first providing an overview of the treatment of codesign and ‘participation’ more broadly in the guides on library planning aimed at professional librarians and library managers. This initial overview will serve as a indicator of the extent to which library staff tend to incorporate participatory elements into these projects (noting that their use of codesign methods for the development of things other than, primarily, spaces may be different, and probably is in the case of, for example, their application of user experience methods for online services).

Library Planning Guides

Handbooks and guides on planning new public library buildings have been available to library staff for many years. They usually note various general principles to consider, including the centrality of the visitor experience, balancing collection and non-collection space, the importance of ‘ambience’, integrating the digital and physical, giving users autonomy (e.g. by incorporating self-service options), and designing for broad societal goals, such as social justice and inclusion, accessibility, and sustainability. Perhaps most of all, given the diversity of user needs and activities, there is an emphasis on creating flexible, multi-purpose spaces. Here we briefly survey notable publications from over the past two decades, but with particular reference to their recommendations concerning community involvement in the planning processes.

Writing for the American Library Association (ALA), McCarthy (Citation2007), an architect, advocates the forming of a building committee comprised of librarian, several board members, and several other staff members, but not community members per se. Neither are details provided as to the extent or nature of the committee’s participation, other than to note that its purpose is to assemble in the early project stages of information gathering and again in the later stages for approving expenditure.

From the United Kingdom, Kahn (2009) headlines a building project’s stages as: schematic design, design development, construction documents, bidding, and construction. He advocates ‘in-depth consultation’, at the pre-building stage, through questionnaires, open days, exhibitions, and public meetings. Consultation is to be replaced in later stages with ‘broader-based engagement and dialogue with the wider community’ (Khan, Citation2009, p. 77).

Community participation through advisory or focus groups is recommended by Warpole (Citation2013) and by Piotrowicz and Osgood (Citation2010), for the purposes of needs assessment, during programming and architectural brief formulation. The group recommended by Piotrowicz and Osgood (Citation2010) consists of library director, staff representatives, governing board members, friends of the library, and local government officials; that recommended by Warpole (Citation2013) is comprised of key library staff, representatives of key community interests, architectural consultants, and people with business planning and management, disability, or sustainability expertise.

Like Khan (Citation2009), Dewe (Citation2016) describes how the different phases of the project can involve different participants: in the pre-planning stage, the librarian participates in needs assessment, evaluation of building alternatives, and securing the budget; in the planning stage, the librarian, architect and the community in consultation participate in the writing and developing the architect’s brief, the selection of the architect and other specialists, and in influencing aspects of the proposed building; and in the design stage, the architect and librarian participate in developing the concept into working drawings.

In another ALA book, Schlipf (Citation2020) also advocates for a focus group to cover needs assessment during the programming and architectural brief formulation stages. He recommends this focus group be comprised of up to about a dozen people with ‘similar interests’, a recommendation that is somewhat inconsistent, however, with his later statement that such a focus group offers everyone in the community a chance to be heard.

In Australia, the Public Library Services team at the State Library of New South Wales (Citation2023) maintains a website that provides guidance to council and library staff looking to develop a new or existing site. It recommends that for both designing new library services and for preparing a library development plan, a working group be established, comprising a project officer/manager, councillors, the library manager and key library staff, council officers from the departments (as applicable) of finance, planning, engineering, information technology, community services, facilities management, etc., community representatives, and any external project manager. This set of stakeholders is expected to evolve over the course of the project and become smaller during the later stages.

The State Library’s website also proposes a ‘community engagement strategy’ framework be implemented, focused on the needs assessment phase of the library development project. The first part of this phase, i.e. that the identification of needs, involves participation. Methods here could include community meetings, consultation websites, e-newsletters, discussion papers and inviting feedback, displays and exhibits in council facilities and public venues, phone surveys and phone-ins, questionnaires and interviews, and focus groups. For focus groups, it is recommended that the following are included: library staff, young people, older residents, parents, play groups, and representatives from multicultural and Indigenous organisations, the Chamber of Commerce, life-long learning organisations, community-based charities, etc. (State Library of New South Wales, Citation2023).

In summary, these guides generally advocate community participation in certain stages of the planning process for new library developments, mainly through the use of focus and advisory groups, but do not advocate participation in the actual design of the new library, nor do they discuss how the participation is elicited in much detail.

Reported Participatory Case Studies

Despite the lack of advocacy in the professional literature for participatory public library design (as opposed to participation in the planning process more broadly), this does not mean that it has never occurred, nor that the ways in which participation can be incorporated into public library projects has never been researched. We summarise in this section key case studies that have involved varying degrees of community or ‘citizen’ participation, as well as a relatively recent survey of participatory elements in American public library projects. The studies are reported chronologically with the aim of outlining a trajectory in the nature and extent of the methods of participation.

One relatively early case of participation was reported by Dudeck (Citation1980), who described users’ involvement in the renovation and expansion of the Toronto Public Libraries. Each branch had co-opted citizen users onto its building committee, which then selected the architect and approved the schematic and final designs. Decisions required a double majority whereby both the resident and citizen components of the committee had to reach a majority vote. Public meetings were then held for both users and non-users to select, but not to participate in developing, design proposals. A lesser level of participation was reported by Oberdorfer (Citation1988), the architect of the Boulder Creek public library in Santa Cruz California. In response to the project’s requirement for community participation an advisory committee was formed with citizens, library staff and county officials.

Washington-Blair in her 1992 dissertation on ‘The Scope and Methods of Citizen Participation in the Planning and Designing Public Library Facilities’ observed that although interest in citizen participation in design and planning had waned since the 1960s and 1970s, many public buildings had been designed using participatory methods. She found attitudes to citizen participation in the planning and designing of public libraries were more favourable among those who has used it than among those who had not, and that participation was generally thought to enhance public relations. Nevertheless, she noted that case studies of public library design had mostly been reported in the professional literature, or not reported at all due to the unavailability of the associated documentation: ‘there appears to be a paucity of material on citizen participation in the literature of library science’ (Washington-Blair, Citation1992, p. 9).

For Washington-Blair’s own case study, the architects, library directors, and library building consultants were sent questions about citizen participation in the design and planning of Denver Public Library (Washington-Blair, Citation1992). Typically, participation was realised through meetings, but use was also made of the design charrette, with one architect having used charrettes to design several other public libraries. (A design charrette is a short, intense period of design or planning activity, often involving a cohort of stakeholders, which may be broken up into subgroups. It is quite commonly employed in certain kinds of traditional design projects, but can also be adapted for codesign (Hughes, Citation2021)). While Washington-Blair reported some communication barriers with the public, the participation was, again, considered to have generally improved public relations.

Mattern (Citation2003) reports on the extent, but not the specific details, of participation in the design of the large Seattle Public library. Participation occurred via ten workshops, townhalls of over 1000 people, led by the architect Rem Koolhaus, and through 37 staff-based working groups organised by the head librarian. Mattern (Citation2003) found that all this participation had had, however, only a limited effect on the architect’s final design, which she attributed to the ‘discursive system’ that had framed the design’s public involvement.

Dalsgaard (Citation2012) uses the phases of a project as a framework to analyse participation that commenced during 2009, for the design of Mediaspace, a large shared library and citizens’ services department in Aarhus, Denmark. Participatory methods were applied across the design phases, from those which articulated central values and visions, through process planning and the establishment of stakeholder networks, for the purposes of developing a program for an architectural competition, to the selection of the winning design.

The redesign of Auraria Library in Denver, Colorado, as reported by Howard and Somerville (Citation2014), adopted a participatory action research approach for two design charrettes. Both charrettes used the same methods for the same sequence of information sharing, ideation and prototyping, but varied in their leadership and execution.

Vold and Evjen (Citation2016) describe Biblo Tøyen as a public library designed specifically for 10–15 year olds in a relatively socio-economically disadvantaged area of Oslo, Norway. Teens participated in the inspiration, ideation and needs analysis stages of design, which resulted in an interesting, brightly coloured interior featuring a kitchen in a truck, a gymnastic floor, and ski elevators. It is not clear to what extent, or if the teens were also involved in the design prototyping, although they were given complete control to devise their own method of organising the books, which the authors describe as ‘serendipitous’.

Dewe’s handbook (Citation2016) for public library planning includes brief, case-study examples from the Camden City Council library service in NSW and the Cambridge library in Western Australia, where library stakeholders were involved in developing the architectural brief and also in the design of the furniture and fit-out, and from the Hikawa Library in Japan, where the community was involved in the entire design process and a webpage was established to document it.

The most extensive discussion of participation in public library planning and design can be found in Ferguson’s PhD dissertation (Citation2017), which surveyed, initially, participatory processes and their occurrence in the various stages of 162 public library projects in the United States. The most common processes involved architect presentations, building committees, and Q&A sessions, which he rated as ‘consultation’, i.e. rung #4 on Arnstein’s ladder (Citation1969) of participation. This kind of participation tended to occur in the earliest phases of the design process, i.e. preliminary design, programming, and design development. Ferguson (Citation2017) notes that these stages can be where participatory inputs are most needed, and cites Chiu (Citation2002, p. 192), who argues that the ‘early design phases [are when] collaboration is the most important [and are] critical to the evolution and quality of the final design’.

Ferguson (Citation2017) also notes, however, that the breadth of the participation reported to have occurred at this and other stages of the design process was quite variable, while its quality and depth could not be reliably established, regardless of the particular methods used. At one library, participation during the design and planning phase did not involve the public, but only library staff and a consultant. At another, the librarian was not involved in the programming, and participation was very compartmentalised, with the public deciding on the site, but not being consulted again until after preliminary planning.

Participation in the early stages of a design also occurred during the design of the Helsinki Public Library. Friends of the library met regularly with architects and staff over a three-month period for a needs analysis (Miettinen, Citation2018). Finally, Lesneski and Bray (Citation2023) report the use of an array of participatory design methods for the Missoula Public Library in Montana, covering visioning, ideation and prototyping, and including adjacency diagrams, user journey mapping and research, and precedent images, in the development of a building program.

These reviewed cases are in line with our perception that participation occurs in public library planning most often in the early stages of projects, but the later cases also reflect an increased use of actual participatory design methods. What they also reveal, however, is a paucity of research into the efficacy of these methods as applied to the design of public library spaces. We have found no researched case studies of Australian public library design, nor any studies comparing results across different cases. Our project would appear to constitute one of the largest and most detailed studies of collaborative ideation and prototyping of a range of public library projects to have been conducted. We report next on the preliminary research we have conducted involving two of our three case studies, before discussing in depth the codesign we are planning in these two cases.

Project’s Preliminary Interviews

With the aim of exploring their understanding of the concept of codesign, as well as what they had in mind for their library development projects, semi-structured online interviews have been conducted with key library staff from the ‘update’ and ‘overhaul’ case study sites (the interviews with staff concerned with the third case, i.e. the project for the brand-new library, and with any design professionals subsequently engaged for any of the projects, will be conducted later). Four staff (referred to as A-D below) were interviewed, two at each site, for between 20 and 40 min. The interview transcripts were coded thematically, with the five authors independently coding some transcripts in common with each other and some not, after which a coder conference was held to settle on a provisional codebook, that was then tested on two of the transcripts: after discussing differences and amending the codebook via the coding of the first of these transcripts, two of the authors independently coded the second transcript with a level of inter-coder agreement of 69.6%. This was deemed a sufficiently high level, for qualitative analysis, to allow one of the authors to then complete the coding of the transcripts, using NVivo software and the amended version of the codebook. The results are summarised below.

The library staff for both cases were able to express their understanding of their development project goals. These goals include making better use of existing spaces, improving visibility and access from the street and car parks, and finding ways to furnish spaces that would allow a flexible use of them. The staff at both sites recognise that although libraries are no longer silent places, there was a need for the flexible use of space that allowed some separation of noisy activities, particularly those involving children.

When asked about their understanding of codesign, the library staff saw the value of the approach as a means of identifying users’ needs, and as a way of allowing those needs to ‘shape the direction that you will take the design for the library’ (interviewee D). The benefits of codesign were also understood to support user engagement and a sense of ownership on the part of the community, resulting in ‘the community as a whole realizing that this space is their space’ (D). Additional benefits of codesign were identified as the community ‘seeing what value for money they’re getting’, and ‘increased community and council satisfaction’ (B). To be successful in using codesign as a means of understanding user needs, the library staff interviewed recognised the importance of operating at a starting point where they are ‘not assuming that [we] know best for your library space, but [are] consulting with them, listening to them’ (C).

The methods of codesign suggested as useful in gathering user ideas are based around recognising the diversity of library users, and finding ways to engage with a broad range of user groups to ensure all needs and ideas are captured. Techniques suggested as useful included ‘town hall meetings’ for a broad range of users, hosting morning teas with specific user groups to talk about their needs, and hanging butchers paper on library walls and encouraging users to draw or write what they would like to see in their library. One interviewee mentioned the possibility of asking users to build models of library spaces they wanted by using ‘Duplo and Lego [so] they can build a little library’ (B). There was also an understanding of the value of ‘involving the … community at … all the development stages. Bringing them in and testing, testing … Does this work? Does this not work?’ (C).

Project’s Preliminary User Surveys

We have already conducted a questionnaire survey amongst users of the libraries in the cases involving the ‘update’ and ‘overhaul’ refurbishments. The questionnaire was devised in consultation with the staff of the two libraries as well as our project’s reference group; essentially the same questions were included in the surveys for the two cases, with slight variations related to differences in the libraries’ circumstances and projects. The intention was to find out what the users did in the existing library spaces, what they thought of them, and how they thought they could be improved (a combination of discovery and ideation).

For both libraries, both online and print versions of the survey were distributed, the former via the libraries’ social media platforms and email lists, the latter by inviting library visitors to fill out and deposit a paper copy. The surveys were anonymous, with respondents needing to be over 18. The online survey used the Survey Monkey platform, into which the responses in the completed paper copies were subsequently manually input. Users were given three weeks to complete the survey, in July 2023. The survey for the third case study will be conducted nearer to the time of its community workshops. The results of the first two surveys are summarised below.

‘Update’ Case

A total of 126 responses (67 online and 59 on paper) were collected. Most adult age groups were represented by the respondents’ sample, though most were of working age, with no respondent over 85. Over two-thirds of respondents were female, less than a third male. Just over half reported English as being an additional language. The breakdown of library visits could be considered reasonably representative of users, with both occasional and frequent users strongly represented. A majority of the respondents tended to visit the library for longer than 30 min, though a large minority visited for less than this amount.

While respondents visited the library to carry out a wide range of activities, and often multiple activities, they noted some common reasons for their visits, including: to utilise the library’s collections; for its quiet environment, which was often linked to being conducive for study/work; due to other favourable aspects of its environment, such as its welcoming and comfortable nature; for its children’s activities and spaces; for certain adult programs and activities it hosted; and to utilise the library’s computers and devices. They were mostly satisfied with the spaces in the library that they used, though not entirely. In fact, over 20% of respondents rated the library’s space overall as either ‘fair’ or ‘poor’, although almost as many rated it ‘excellent’. A large majority usually felt safe in the library and could usually find their way around, though only 55% always felt welcome.

Survey participants were asked to comment on what they liked about the library’s existing spaces. A wide range of aspects were covered in their responses. Most of all, respondents appreciated the comfortable nature of the environment and its furnishings; related to this, there were comments about the library’s bright, but also quiet spaces. On the one hand, the library was open and spacious, on the other it afforded privacy, particularly with its meeting rooms and other more enclosed areas and features. Another relatively popular feature was its power/charging points.

Respondents also suggested various ways in which the library’s spaces could be improved, including by: making the kids’ area bigger, and less linear, and more comfortable and engaging for the children, and separate, but also with a clear line of sight from across the rest of the library; making the computer area bigger and less cramped; soundproofing the meeting rooms and study area; adding separate rooms for quiet study; increasing the number of booths and the size of the tables; adding more armchairs near the collections; adding more shelving along the walls, etc.; adding more lighting, and making the spaces more open; reducing the size of the service desks; installing a water fountain; adding a new carpet (or something other than a carpet), and a 24/7 book returns chute. Other suggestions for new features included: a lounge area; an area for ‘tweens’; music rooms; a board games section; pot plants; and a water dispenser. A café was also proposed.

‘Overhaul’ Case

A total of 67 responses (57 online and 10 on paper) were collected. Most adult age groups were represented in the sample of respondents, though there was no representation from the 18 to 24 age bracket. About two thirds of respondents were female, about a third male. About a fifth reported English as being an additional language. Most respondents visited the library once or twice a month or less frequently, but about a third visited the library more often. About half of the respondents tended to spend more than 30 min per visit in the library, about a quarter usually less than 30 min, and another quarter sometimes more and sometimes less.

When asked to specify the main reasons for visiting the library, respondents gave a wide range of answers, including: to utilise the library’s (physical) collections, especially its books; for its children’s activities and spaces (as parents, grandparents, etc.); for certain adult programs and activities it hosts; and for various aspects of its environment, such as its ‘relaxing’ nature. Many of the library’s areas were heavily used, and most respondents were quite satisfied with them. They were also mostly positive about the library in general, including about how welcoming and safe it was, though almost 40% of respondents did not always find it easy to find their way around. There were nevertheless quite a number of suggestions made for its improvement. These included a more child-inviting and comfortable kids’ area; a closed-off, small meeting room to serve as a ‘safe space’; more dedicated study and computer spaces; more book displays; more comfortable and cosier seating; and a ‘quiet area’. Other specific features they recommended included: a section providing international newspapers; more regular cycling of public art displays of a local nature; more plants; more cosy spots to read to infants and small children; and a breastfeeding area or changing spot. As in the other case study, a coffee shop was also suggested.

Workshop Design

The heart of the codesign in our project will be the community workshops in which the third and fourth design phases, according to our model, will take place, i.e. the ideation and the prototyping. At the beginning of the program of workshops, in each case, we will summarise the research from the first phase, including the results of the preliminary user surveys, to inform the workshop participants’ thinking about their task, which will also be defined in the workshops’ introduction. (We will additionally provide this information to the recruited participants online via the emails we will send them confirming their participation a few weeks prior.) One other piece of research that will feed into the workshops will be a head count of users in the different areas of the existing libraries.

In summary, the workshop participants’ task (or ‘problem’), in the case of the refurbishments, will be to redesign the existing space, given certain constraints (such as fixtures, a certain amount of required shelving, spaces for the library staff, etc.), in a way that is, for example, as functional and welcoming as possible. The task in the case of the brand-new library will naturally be far less constrained, but nevertheless framed similarly. Given the greater scope for creativity, however, the workshops of the third case will be longer and designed differently. In this article, we will focus on the design of the first two cases; the workshops for the third case will be designed later in 2024, closer to the time of the workshops and after the preliminary user survey has been conducted.

For the refurbishments, we have formed the view that about six hours of workshops may be the limit that one can reasonably expect volunteer community members to undertake, and so we have devised activities to fit into three two-hour workshops, that will be held one or two weeks apart. They will be conducted in the existing library spaces, as these are the spaces the co-designers will still need to work with, though much of the workshop activity will take place specifically in each library’s large meeting room (partly for practical reasons, but also to provide participants with a relatively neutral environment in which to ideate and prototype).

The relatively small amount of codesign time we have for these cases means that iteration, particularly across phases, may be somewhat limited, but we had to balance this with our aim of progressing further through the design phases than is the norm for codesign, especially in relation to the codesign of public library spaces. In fact, we could have given over most of the six hours just to ideation, or to ideation and only certain of the prototyping elements, or to have accommodated ‘rapid prototyping’ through activities that would have resulted in less fully formed solutions to the task in hand. However, given the physical and economic constraints of the refurbishment projects, we believe that our more ambitious approach is still feasible, with the number of possible solutions being far less multitudinous than in the case of the project for a brand-new library with a far larger budget. Nevertheless, we have built in as much scope as possible for iteration, particularly within activities.

Another key consideration for the workshops was that of the composition of the cohort, and also its number. Originally, we envisaged conducting repeat workshops to cater for community members’ different availability, but the literature advises against a large number of codesign participants (Efeoğlu & Møller, Citation2023), and so, ultimately, we opted for a single cohort participating in weekly or fortnightly sessions on a day and time that would best allow for representation across key demographic groups, including younger adults, parents, and seniors, as well as both genders. We are recruiting partly through the preliminary user survey, with respondents being invited to register their interest in participating in the workshops after submitting their responses, and partly by soliciting interest directly from representatives of key community interest and user groups. The aim is for the cohort to comprise about 12 community members, bearing in mind the likelihood of some attrition across the series of workshops, along with the library staff and designers directly involved in the library’s project. We decided not to offer the community members cash incentives to participate, as we wanted to ensure that participants are motivated primarily by their interest in improving their library’s space (though the libraries are providing refreshments in each of the workshops).

As one of the libraries had a particular interest in redesigning their children’s and teens’ areas, we have also planned additional sessions and activities specifically for this element of this library’s redesign, which will feed into the main program of workshops (i.e. the series of three workshops for the overall library codesign). One of the teenagers from the dedicated teens’ workshop will be drafted into the main workshop program to help feed the teens’ workshop’s outcomes into the subsequent workshops and to represent the age group.

Workshop Activities

There are many documented (though not necessarily researched) codesign and participatory design activities intended for workshops, and that could be used in workshops involving community members, and so rather than invent new ones (especially as our product, i.e. a physical space, is not especially unusual as a kind of thing to be codesigned), we considered those (or the descriptions of those) that we could find from various sources, including websites and databases made available by companies specialising in codesign, codesign toolkits and guides emanating from particular projects, and written-up case studies. Of course, not all codesign activities are going to be equally suited to our codesign context. We looked in particular for activities that a broad cross-section of community members could readily undertake in a face-to-face workshop setting (with assistance from the facilitator), and that would be replicable (perhaps with some adaptation) for other public library development projects (so e.g. those not requiring very expensive materials or equipment). Moreover, the activities needed to be suitable for the thing being codesigned, which in our cases is primarily an indoor, public space for a range of activities carried out by a wide range of community members, some self-directed, others coordinated and organised. It should be noted here that public library development projects generally afford, as in our cases, some scope also for new or different services and/or content (e.g. new collection items or equipment for users) to be introduced into the new spaces, although this scope tends to be relatively limited for branch libraries working with existing spaces (in the case of refurbishments) and modest budgets.

As many codesign activities are primarily geared to the design or redesign not of physical spaces, but of products that do not resemble spaces, or of services, or of online ‘spaces’, such as websites and online systems, or other kinds of system, we set aside a large number of the less suitable activities we found. Whilst some activities are relatively generic in nature, others tend to be domain specific and more specialised. Of the 76 collaborative ideation toolkits and the like that Peters et al. (Citation2021) found in their own searching, they deemed 37 to domain specific (but not specific to the domain of architecture or interior design).

We also noticed that descriptions for some differently named activities suggested they were variants, and indeed in some cases this was explicitly acknowledged. We treated activities as separate entries in the table we compiled, however, unless their distinction was not one that would be commonly made; we also noted the descriptions of different activities with the same name in one or two cases.

Activities that focused more on the prototyping phase of the design process were harder to pin down as specifically codesign activities. For one thing, codesign less often reaches this stage of the design process; for another, ‘making’ tends to be more dependent on particular materials, and the things being created, than does ideation, and thus the domain tends to be prioritised over the codesign aspect. For this later stage, we therefore sought out suitable design activities regardless of whether they were billed explicitly as being for codesign.

Kinds of Workshop Activity

Many of the activities that we found facilitated the ideation phase of our design thinking model, but we also we noticed that a fair proportion of the activities recommended for codesign projects and workshops do not function primarily in a way that directly represents any phases in our model of the design process. Instead, they are used to support the workshopping itself, or to help prepare participants for ideation, etc., or to help participants evaluate outputs. To support the workshopping in general, a very common activity is the ‘icebreaker’, of particular importance, perhaps, in the context of a community workshop: some of the participants might happen to know each other, but it is likely that most will know only a few, if any, of their fellow participants. There are many sources for workshop icebreakers, and we will select and adapt one for each of our cohorts. Other activities supportive of the workshopping in general include ‘team building’ exercises, which would be more appropriate for cohorts working together for longer periods of time, and ‘leg stretchers’ (which essentially serve as breaks).

Other activities we found are designed to facilitate the evaluation of the findings, ideas or designs produced by the discovery, ideation or prototyping activities, ultimately to progress the process toward a particular solution (i.e. ‘convergence’ in common codesign parlance). Whilst these activities were sometimes classed as ideational (when associated with the evaluation of outcomes from ideation), we categorised them separately, as evaluative. A prime example is an activity involving some form of voting (on particular ideas or prototypes, etc.). They may also help participants organise outputs from previous activities as a way of facilitating the evaluation. We have incorporated two evaluative activities into the workshop design for our first two case studies, and discuss this group of activities further below.

Other ‘ancillary’ activities include those that help prepare participants for their actual design efforts. Some activities, for instance, ‘warm up’ participants so that they have heightened awareness of certain aspects of the design goal. In the case of a physical space, for example, the activity might encourage participants to start thinking specifically about spaces and their sensory nature. Or they might encourage a creative mindset more generally. Biskjaer et al. (Citation2017) label this function as ‘framing’ in their analysis of ‘creativity methods’ in design.

We should note here the overlap between our categorisations of the activities we compiled. Some of the activities could be used, and are used, to perform multiple functions. For example, an icebreaker could also be used as a warm-up activity to foster participants’ creativity, or a brainstorming, ideation exercise could include an evaluative element. However, for the purposes of organising our table of activities, we classified those activities we considered to be predominantly ancillary activities as such, as distinct from predominantly ideational or prototyping activities, as defined in our model.

After quite extensive searching, we ended up with 76 activities altogether, excluding icebreakers and other generic ancillary activities, at which point we were often finding the same activities, or variants of them. We do not claim that ours is an exhaustive list even of activities suitable for our project, but we were reasonably confident that we had found most of those suitable activities commonly recommended for codesign projects such as ours, particularly with respect to ideation. However, codesign workshops do not, or should not, simply consist of an array of activities taken arbitrarily from a list. We have already alluded to the importance of ancillary activities, while some activities are going to be more suitable for a particular project context than are others. Some may also fit better in combination with some others. To consider which activities to include in our workshops, we needed first to work out what room there was for different activities, and different kinds of activities, given the time constraints.

Structure of Workshop Program

We did not expect to arrive at a blueprint for each library by the end of each series of workshops, but we were aiming to get as close to this stage as possible, so at least to some point in the prototyping phase, for the designers and/or library staff to then take through to the final phase of our model (i.e. ‘test’, after the realisation of the design). In our design context, prototyping involves making ideas generated from the previous phase tangible in either 2D or 3D form. It was not realistic to expect actual 3D prototypes of the refurbished spaces, even rough ones, to be constructed by the participants within six hours of workshops, but various computer applications have been developed to assist both with the drawing up of 2D plans for buildings and interior designs, and also to render them as 3D visualisations. Whilst applications such as computer-aided design (CAD) software are aimed at the professional market, there are others, such as Floorplanner (https://floorplanner.com), that cater more for hobbyists and non-professionals, but nevertheless do an impressive job at allowing users to create quite detailed interior designs to scale. The structural elements of most spaces, and their fixtures and fittings, can be drawn up using the tool, without the need for any special training, and then a wide range of furniture and other content can be added to the floor plan, from the ‘style board’, with instant 3D rendering allowing users to edit their designs confidently and quickly. Floorplanner is currently offered gratis to single users and charges only a fairly modest subscription fee for multiple users.

After a pilot run of our initial workshop design, we concluded that it would not be realistic to aim for convergence of the participants’ opinions, in six hours of workshops, on the aesthetics of the interior redesign, but that we may be able to achieve consensus on the layout of the refurbished libraries, and we intend to use the Floorplanner application specifically to create a finalised floor plan, sans specific furniture and finishes. This would nevertheless represent a much more advanced outcome than what might be obtained by the end of the ideation phase, such as a pen-and-paper sketch or a Lego-based model.

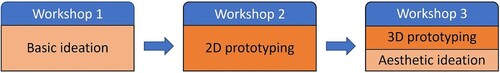

Again, working backwards, in order to be in a position to edit draft floor plans in applications such as Floorplanner, the cohort needs to have iterated different arrangements, and shapes and sizes, of the various areas they want for their new library space, and to have added at least some standard content (e.g. chairs, tables, shelving, etc.) they want in those areas. Before that, they need to have thought about what areas they want, and what they want them to look like and be like, and, more generally, about what they want to see in their new library and how it should function. Clearly, all these activities are linked, and we wanted to allocate as much time as we could for all of them, but the activities that were part of the prototyping phase of the process were of a relatively technical nature, which we did not think could be streamlined any more than what we ended up with, that is, one and a half workshops’ worth of activities. As we also wanted the codesign process to at least produce ideas for the aesthetics of the new library spaces, based on the desired layout, an additional activity based on ‘mood boards’ was also included, following the Floorplanner activity at the end of the workshop program. Both the Floorplanner and mood board activities require a fair amount of time, and thus constituted most of the third workshop. This meant that the preliminary, ideational activities were assigned the whole of the first workshop, with the prototyping activities feeding into the Floorplanner application filling up the second workshop. The three workshops’ basic sequencing is outlined in .

Ideation Activities

Looking through our 56 ideation activities (out of the 76 activities altogether that we compiled), we identified three subcategories of activity: those primarily designed to elicit new ideas, which we called brainstorming activities by way of shorthand (a fair number of these activities were either called some form of brainstorm, e.g. ‘3-12-3 brainstorm’, or were described as such); those that not so much generate new ideas as develop them, typically using some sort of conceptual template, which we called developing; and those designed to elicit ideas about the current product, situation, etc., which we called critiquing (potentially in positive as well as negative ways). It could well be argued that the critiquing activities are in fact part of the first phase of our model, associated with analysis and so forth, and at one level they are, but as codesign workshop activities they can also generate ideas about how to improve on the thing being (re)designed, including potentially new ideas. One commonly used activity that falls into this subcategory is the SWOT analysis (Nutt & Backoff, Citation1993), while ‘My favourite place’ (Hwang & Fellow, Citation2012, p. 18) could be adapted to our context by asking participants to nominate and discuss their favourite spaces within the existing library. Another activity, that we are looking to use, is a cognitive mapping exercise (Guelton, Citation2023), in which, in our adaptation, participants are asked to map a generalised visit to their library, on a blank piece of paper, indicating critical points in their visit, that might elicit either positive or negative emotions. As these critiquing activities represent a bridge between the analyse/define and ideate phases, logically they tend to be undertaken prior to the brainstorming and developing ideation activities, as we can see in those participatory design methods in which a current situation is critiqued before a future situation is imagined (Brandt et al., Citation2012). We have followed suit in our workshop design.

Various brainstorming activities could have been selected for our main ideation activity in the first workshop, but the multifaceted and complex nature of our thing to be designed, i.e. a library space, made simply generating a list of ideas less useful than in other codesign contexts. It is not as if there is any chance that any of the library spaces will be turned into one new thing, such as a tower of books or a dance floor. Rather, lots of good ideas need to be integrated into an optimal solution. Thus, there is an emphasis here, bearing in mind the workshop’s limited timeframe, on the development of ideas, and so we favoured an activity that started by generating ideas and then took them to a further stage, although a short brainstorming activity followed by a developing activity could also be a viable option. If we were to include a purely brainstorming activity, there are several commonly used ones to choose from, such as ‘Crazy 8s’ (Stevenson, Citation2019) and Post-Up (Gray, Citation2010b). Some trigger ideas by encouraging participants to think laterally, by means of, for example, analogy, as in the case of ‘Brainstorming in an analogous context’ (Celikoglu et al., Citation2017), in which participants actually visit an analogous space for inspiration. Other brainstorms encourage thinking ‘outside the box’, as with ‘Opposite thinking’ (Thinking wrong exercise, Citationn.d.), in which participants are asked to ignore certain assumptions about the situation and think of how things might be. A more specific variation on this is ‘Billionaire dream’ (Panchenko, Citationn.d.), where participants are asked to imagine they have an unlimited budget. Open-ended scenarios are used as the basis for many brainstorms, as they are for many of the developing activities. A common mechanism is to transport the participants into the future, divorced (at least to some extent) from the constraints of the current situation. If more visual ideas are desired, brainstorming activities like ‘Flip and rip’ (Flip and rip, Citationn.d.), in which participants find inspiring pictures in magazine and relate them to what they want to see (in our case, in their new library space), are often used. If other sensory facets of the thing being designed are also important, then another option is ‘Sensorial’ (Digital Society School, Citationn.d.), in which participants are asked to generate ideas for all five senses (vision, scent, feeling, hearing, and tasting).

The developing ideation activities we found, progressed ideas, but to a point at which they remained ideas, or sets of ideas, rather than became any kind of prototype, facilitating the refinement and integration of different ideas, after which prototypes can be created. One of these activities that we picked out as being particularly applicable to our context is ‘Cover story’ (Gray, Citation2010d), in which participants are asked to create an article, for the front page of e.g. their local newspaper, about their new product (in this case their library’s refurbishment). A quite similar exercise is ‘The pitch’ (Gray, Citation2010a), in which groups work on a pitch to sell their new product. An advantage of ‘Cover story’, however, is its greater accommodation of multiple ideas (a cover story could include different sections and images highlighting different aspects of the library refurbishment). Another kind of developing activity is one in which different participants take turns to develop the idea(s); an example of this is ‘Brainwriting’ (Athuraliya, Citation2023), in which they expand on each other’s contributions in written form, on passed-around pieces of paper. More tactile and visual developing activities includes ‘The dollhouse’ (Sanders, Citation2019, p. 50), in which a customised toolkit is created for participants to explore their space, as a 3D model, and the possibilities it affords. Another exercise, which we plan to use in the third workshop, as noted above, is that of creating ‘Mood boards’ (Celikoglu et al., Citation2017), through which participants explore the different feelings and emotions evoked by a wide range of images and objects made available to them, ultimately assembling a representation of a visual and atmospheric theme for, in our case, their library. Many of these activities combine brainstorming and the development of the ideas brainstormed, though there are also generic tools (i.e. activities) specifically used for ideational development, and that can be used in many codesign contexts, including storyboarding (Gray, Citation2010c) and concept mapping (Gibbons, Citation2019).

Ancillary Activities

Along with the icebreaker, we will be looking to bring about a degree of convergence at the end of the first workshop and the ideation phase, through an evaluative activity. We identified ten for consideration, including generic ones such as ‘Dotmocracy’ (Hidalgo, Citation2018), in which participants use green, yellow and red stickers to vote on their cohort’s various ideas, solutions, etc. Another filtering activity is ‘The idea vault’ (Robertson, Citationn.d.). Other activities guide the participants’ assessments by focusing on particular qualities. An example of this is ‘Heart, hand, mind’ (Gray, Citation2011b), where participants are asked about the emotional, practical and conceptual merits of each solution. Sometimes the guidance comes with an explicit framework, as in the activity, ‘How-Now-Wow matrix’ (Gray, Citation2011c), where participants vote for different ideas or solutions, but after discussing where they sit within the two axes of feasibility and originality. Some activities supporting evaluation encourage the participants to work out for themselves what qualities in the solutions they should be looking for, as with ‘20/20 vision’ (Gray, Citation2011a), which simply invites participants to arrange them in order of ‘priority’.

Finally, we were interested in including an activity that would encourage the workshop participants to start thinking specifically about physical spaces, and what makes some spaces good and other less so, in preparation for the ideation. Of particular applicability to our context is the ‘Qualities of space’ activity, in which participants are asked to note down things they like and dislike about the spaces conveyed in particular images; we are using spaces to be found in the local community area, with which participants may be familiar and be able to particularly relate to. This we classified as a ‘supportive’ activity, and, in the first workshop, have it preceding the ideation activities themselves.

Prototyping Activities

As noted earlier, prototyping methods depend to a fair extent on the thing being prototyped. When the thing is predominantly a physical indoor space, or a building, there are both 2D and 3D ways of making the ideas for it tangible. The basic 2D approach is to create a floor plan (or a plan for multiple floors), if the focus is on the refurbishment of an existing space, or an architectural plan for a building, if the whole building is going to be new; 3D approaches involve either constructing, by hand, a mock-up of the space or building, or using a computer application to render a 2D plan into a 3D visualisation of the design. We believe it feasible for a cohort consisting of community members, library staff, and professional designers to translate their ideas for a library refurbishment into a basic floor plan using rudimentary versions of the standard, manual techniques used by interior designers and architects for creating such a plan (see e.g. Karlen & Fleming, Citation2016). The details of the resulting paper-based plan can then be fed into the Floorplanner application between the second and third workshops, for our case studies, so that the cohort then can view a 3D rendering of their plan and make adjustments to it as they see fit (in the third workshop). While we intend to have the participants add standard furniture to the floor plan, we are not aiming for the final version of this plan to specify the particular furniture and finishes; these will need to be settled upon by the library staff and/or designers, according to budget and other parameters, although the participants’ mood boards, that they will create in the second part of the third workshop, will be utilised for this post-workshop stage.

Standard space planning usually breaks down the process of creating a floor plan into a few sequenced activities. Like many other spaces, libraries tend to be divided into various areas, for different activities, content (e.g. shelving), and so on. The main object here is to work out the arrangement and size of these areas, in relation to the underlying space and structure. Before starting on this task, however, we must have a provisional list of the areas, and an idea of what they should look like. This is the ultimate objective of the ideation phase and, in our case, the first workshop. Bubble diagramming is a standard way of working out the optimal arrangement of the desired areas, but before this is carried out, a useful preparatory activity is to consider the areas’ affinities with each other, in other words, whether their adjacency (or proximity) would be a good or bad thing. We are therefore planning on starting the second workshop with an exercise involving the completion of a basic, spatial affinity chart, which serves this purpose and can be referred to in the subsequent activity. As such, it might be viewed as an activity that supports the actual prototyping and creation of the floor plan.

Bubble diagramming essentially involves designers (or co-designers) arranging and rearranging ‘bubbles’ that stand for the various areas of the space. We will be using pre-cut cards, with the names of the various desired areas written on them, and sheets of paper printed with the outlines and fixtures of the library spaces, to scale. Participants continue arranging the bubbles until satisfied they have achieved their optimal layout, referring to the spatial affinity chart as needed.