ABSTRACT

While the years spent in college or graduate school have traditionally been viewed as demanding, current students face financial, emotional, and mental health stressors that interfere with their success at alarming rates. Undoubtedly social issues, cultural challenges, and economic realities complicate these experiences for students. At the same time, the negative effects of stress on learning capacity can prompt a blurring of the traditional line between educator and supporter, especially for social work educators. One hundred twenty-eight social work educators responded to a survey questionnaire about what helps or hinders their efforts to support student wellness. Inductive content analyses were conducted with seven themes identified around what supports educators and five themes identified around barriers that interfere with educators in their efforts to address student wellness needs. Major factors influencing educator effects include resource availability, educator-student partnerships, wellness-centered pedagogy, environmental culture, and oppressive forces. Implications for social work educators and administrators are explored.

At the heart of social work is the mission to promote social justice and ameliorate problematic conditions in service to the most vulnerable. At the heart of social work education is the responsibility to effectively prepare students to support clients and alter systems. These two missions demand particular attention when the students we are training are experiencing social, economic, and personal stressors that can complicate learning.

Students can face challenges to their overall wellness that complicate their academic success and professional preparation, such as financial issues, mental health challenges, and housing instability (Haskett et al., Citation2021; Leung et al., Citation2021). For instance, inconsistent access to food negatively affects physical health and mental health (Kim et al., Citation2022; Livingstone et al., Citation2023) and is associated with impaired concentration, lowered GPAs, and leaving school (Hege et al., Citation2021). Severe mental health distress in students is correlated with impaired academic success (Jeffries & Salzer, Citation2022). When students are simply too overwhelmed with stressors, they are less likely to be able to engage in deep learning experiences (Hews et al., Citation2022). Struggling students can also feel negatively (anger, sadness, irritation) toward their academic institution and resent their peers (Meza et al., Citation2019), further complicating the motivation to engage with the learning material. Researchers emphasize the need to explore how students’ emotional experience interacts with their learning readiness (Shine et al., Citation2021).

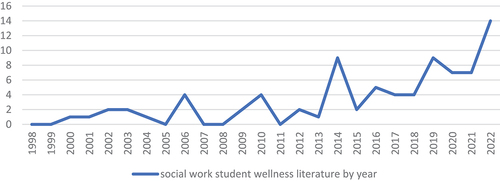

Social work educators and researchers are focusing more attention on addressing student wellness. A literature search conducted in August 2023 within relevant databases (Academic Search Complete, Education Source, APA PsycArticles, APA PsychInfo, Social Sciences Full Text, and Social Work Abstracts) using the terms “self-care” OR “self care” OR “wellness” OR “well-being” OR “wellbeing” OR “stress” OR “distress” AND “social work student” revealed increasing publication frequency around aspects of social work student stress and wellness. After the articles were reviewed for relevance and to eliminate redundancy, was created to chart the changing literature focus.

This recent social work literature demonstrates increasing awareness of the interconnections between student wellbeing and effective social work education. This commitment to student wellbeing is even being integrated directly into classroom learning and curricular goals such as in the following examples. Responding to concerns about student stress and burnout, Ogden and Rogerson (Citation2021) infused positive education practices (including assignments to recognize and discuss personal strengths, practice gratitude, and intentionally apply humor into MSW courses as ways to build resilience). These positive education practices were associated with increased optimism and sense of meaning for these MSW students. Numerous social work educators and researchers have demonstrated the value of incorporating mindfulness-based strategies into their courses to strengthen their students’ wellbeing or self-care into the curriculum (Gockel et al., Citation2019; Grise-Owens et al., Citation2018; Maddock et al., Citation2022; Notar, Citation2022; Warren & Deckert, Citation2020). Learning from the trials of practicing social work during the pandemic, Clary and Hernandez (Citation2022) discuss centering work-life integration and self-care into an undergraduate social work syllabus.

Additional indicators of this movement in social work education are the initiatives social work institutions are creating to address wellness needs of students and professionals. Social work departments and schools are assisting with the creation or maintenance of campus food pantries, such as University of Texas at Austin or the University of Maryland at Baltimore (Cortina, Citation2022; Steve Hicks School of Social Work, Citation2023). The University of Buffalo School of Social Work offers free self-care resources and related skills training for students and professionals (University of Buffalo School of Social Work, Citation2023) and the University of Kentucky Self Care Lab studies best practices in self-care for helping professionals (University of Kentucky College of Social Work, Citation2023). Florida State University College of Social Work developed a Professional Certification in College Student Wellbeing, Trauma and Resilience to train higher education professionals to better work with distressed students (Florida State University, Citation2023).

Social work educators have responsibilities to provide strong learning environments for all their students many of whom are struggling to meet their basic emotional and physical needs. This balance of prioritizing student wellness and effectively preparing future social workers can be challenging. Based upon the reviewed literature, we know that compromised wellbeing negatively affects students, that educators are trying to alter their teaching practices to support students, and that social work educational institutions are trying to create larger interventions to address student need and distress. There is, however, limited research on factors that help or impede individual social work educator efforts to address student wellness needs. In the spirit of a call for contextual investigation of methods to better support students (Trawver et al., Citation2020), this study considers social work educator perspectives on factors that facilitate and interfere with efforts to support student wellness needs. Two questions were asked that served as both research questions and survey questions: 1) What helps you when supporting social work student wellness needs? and 2) What barriers do you face when supporting social work student wellness needs? Rather than limit the focus to curricular content, the questions were broad enough to elicit a range of ways that educators think about the diverse ways instructors attempt to strengthen student wellness. Examining supports and barriers can strengthen pedagogical practices amid diverse student needs.

Materials and methods

The Indiana University Human Subjects Review Board reviewed the submitted protocol and approved the research [#13560]. An anonymous Qualtrics survey was developed to understand social work educators’ views about student wellness needs. A study information sheet in the survey informed the possible participants of the nature of the research including risks and benefits, and respondents indicated agreement with this in order to gain access to the survey. The survey consisted of demographics and closed- and open-ended questions to gather improved understanding of how social work educators thought about student wellness. The college wellness literature was reviewed and used to inform some of the questions. Two open-ended questions explored social work educator perspectives on supports and barriers they face when trying to support student wellness needs. The survey was shared with social work educator colleagues of the researchers for feedback and then revisions were made to improve clarity of the survey. The researchers collected a convenience sample of United States social work educators by distributing the survey through social work education e-mail distribution lists and colleague connections in Spring 2022. Respondents could separately submit their e-mail for a chance to win an e-gift card.

Participants

There were 128 respondents answering at least one of the two questions on supports and barriers. Their ages ranged from 31 to 75 years, with a mean of 51.14 (10.52). The number of years as an educator ranged from 1 to 37 years, with an average of 14.12 (9.18) years. The majority of respondents identified as female (78.9%), 19.5% identified as male, and less than 1% identified as transgender. The racial and ethnic identities of respondents were 83.6% White, 7.0% Black, 3.1% Asian, 2.3% Hispanic or Latino, 1.6% Multiracial, and 2.3% preferred not to share. Most respondents had a doctoral degree (68.8%) or Master’s degree (30.5%). Over half of the respondents were tenure line (63.3%), 11.8% were full-time non-tenure track or advisors, 10.2% were field educators, 7.1% were part-time, adjunct, or doctoral students, 4.7% were administrators or program directors, and 3.1% were staff members.

Analysis

Researchers applied an inductive content analysis (ICA) to categorize the qualitative responses following Vears and Gillam (Citation2022). ICA allows the researcher to identify codes from within the text rather than a pre-ordained theory and to keep the focus on the respondents’ data rather than requiring a more interpretative approach. The responses to each open-ended question were analyzed separately. The initial step of ICA involved reviewing and gaining familiarity with all the responses. Then the coding was done in several rounds, with similar responses being labeled, synthesized, and differentiated with subsequent re-reads. When a single response reflected several different codes, each phrase was coded and tallied distinctly. The response frequency indicates what percentage of respondents endorsed each code. The trustworthiness of these results were established with attention at each phase of the process, the preparation stage, organization phase, and reporting phase (Elo et al., Citation2014). In the preparation of the survey, feedback from colleagues provided insight into improving clarity in the questions. During the organization phase in the analysis the researchers repeatedly reviewed the concepts so the coded themes were as concise as possible when demonstrating common ideas. In the reporting phase, each theme is presented with exemplar quotations to ground the concepts readily in the data.

Results

Of the 128 survey respondents, 119 answered the question about supports and 127 answered the question about barriers. The results will first present factors that support educators in addressing student wellness needs and will then discuss barriers that interfere with supporting students.

Supporting student wellness needs

Respondents identified 166 factors that help them support student wellness needs. Seven themes emerged and are presented with quotations. See for an overview of the themes.

Table 1. What helps you when supporting social work student wellness needs?

The most identified theme was Access to Resources (26.5%). Unsurprisingly, easy access to student supports was a primary factor helping educators address student wellness. One respondent explained:

Having a well-resourced University-community that has supports in place to help support students. (such as: a food bank, information on financial help for them that I can point to, housing information and help I can point them to, a robust mental health resource on campus that does not have long wait times)

Educators recognized the crucial importance of these resources. Some respondents emphasized the ready availability of resources at their institution such as the educator who said, “The huge number of resources of all types offered by my institution.” Other participants acknowledged their absence, such as this educator described, “When the school actually has resources (rarely).” One respondent stated, “Knowledge of new campus based resources and knowledge of community based resources,” highlighting that it is not enough for a school to have resources for students, but it is necessary that the faculty be well aware of them.

Faculty & Departmental Support (25.3%) was also a factor aiding educators. While respondents valued colleagues who were similarly invested in student wellness, their reasons varied. For some, it was about the student having multiple supports and flexibility, even beyond the educator’s own classroom. A participant acknowledged the value of “Colleagues -especially nonsocial work – who recognize when students need support, so the student has a safety net of caring across their different courses.” Other respondents benefitted from collegial support. One participant described, ” Brainstorming, venting, and sharing the work with colleagues.” This seemed to provide both normalization of the efforts and validation of the importance. Respondents also felt supported when their larger department or university had practices that aligned with addressing student needs such as the educator who wrote, “my university is very student-centered so this is valued within the department, school, and university.”

Over 15% of respondents described Fostering a Culture of Care as helping them support student wellness needs. A primary focus was relationship building with students, as the following educator described:

Simply being focused on each student and intentionally reaching out to them particularly when you know they are under a unique type of stress. This also seems to really have positive outcomes - it fosters trust and faith in me as a source of support as they go through their educational program. By creating that trustful and affirming space for students, they are more likely to reach out when they have needs and you can more effectively support them.

Respondents described specific methods they used to demonstrate their care for students, such as expressing empathy and showing authentic interest in the students. One educator stated:

Being open and honest with them and also doing frequent check-ins to make sure they are doing okay. It’s also helpful to have a relationship with them so that they feel comfortable sharing times when they do not feel well.

Educators fostered a sense of care and concern between students. One respondent stated, “I train social work students to support their colleagues and other college students.” They perceived that students benefited from learning from each other, such as this respondent who wrote, “Hearing each other talking about their struggles helps them realize that they do need help.” Sometimes educators directly encouraged wellness, such as the respondent who stated, “I will engage students in discussions about how they are doing and have a self-care moment every class.” Respondents also nurtured partnerships of care within the department. One participant described, “Mentoring new faculty and teaching them my approach from the beginning.” Another respondent wrote, “Making students aware that they can actually come to faculty members to discuss their personal wellness. Expressing that we care about them, beyond their classroom performance.” These efforts fostered caring environments, which respondents believed helped them support student wellness.

Over 11% of respondents described their Personal Convictions, beliefs the social work educators had that motivated them to address student wellness needs. Some educators derived their energy for student wellness interventions from their beliefs around the positive changes they could affect. One respondent wrote, “Remembering that I have ability to use my authority and power to make a difference” and another educator stated, “Knowing that even just being a voice, naming the challenges, encouraging open dialogue, and working to reduce stigma at least moves the needle, even if it’s just a little bit……” For other educators their wellness efforts aligned with their perceptions of themselves as social workers, such as the educator who described, “My own passion for staying excited about social work.” Several educators named pedagogical reasons fueling their efforts. An educator stated, “Thinking about how their overall well-being impacts their work/learning in the class.”

About 9% of respondents described that Professional Experience, Skills, or Knowledge helped them support student needs. They applied their expertise and training to assisting students. One educator stated “my skills as a social worker” and another noted, “clinical background.” Educators felt their social work skills helped them connect in the classroom, such as the educator who stated, “My ability to establish rapport with students.” Respondents also incorporated their professional expertise into their teaching. One responded asserted, “I have been learning about trauma informed teaching and integrating it into my teaching style.” Another respondent described, “my personal and professional experiences allow me to develop coping skills in students.” Educators experience making referrals was also beneficial. A participant stated, “I can make all the connections to community agencies I’d make when I was a community social worker.”

Over 6% of the respondents described Student Openness as helping them address student wellness. Student openness and communication style made it easier for instructors to respond, such as this educator described:

It is essential that students talk to me. I have students who will get behind and stop doing assignments or do several poorly and then expect me to go back and allow them to redo things because they were struggling. I tell students repeatedly that they need to reach out when difficulties start, but they often do not.

Some respondents perceived that students needed to take action to help themselves. Educators recognized that student willingness to be open could be limited by concern about their privacy. A participant stated, “Oftentimes students are reluctant to use campus based resources because they fear being seen by other students or social work interns they know going into various offices.” Another respondent demonstrated that student priorities could limit their willingness to make wellness changes, “The student caring about his/her wellness needs more than a grade or getting a degree by a certain time at all cost.”

Several (5%) respondents described their Personal Wellness as helping them address student wellness needs. They shared intentional efforts made to strengthen personal self-regulation. One educator stated, “my own mindfulness practice,” and another described, “managing my own self-care.” Another educator noted, “materials about inner peace that have kept me from burning out.” Personal wellness can alter one’s capacity to be present for not only clients, but also students.

Barriers to supporting student wellness needs

The 127 participants who responded to the barriers question identified 194 factors interfering with supporting student wellness. These were grouped into five themes separated into additional subthemes. presents an overview of themes and frequencies of these barriers.

Table 2. What barriers do you face when supporting social work student wellness needs?

Limitations were identified as barriers to supporting student wellness by 45% of respondents. Limitations included three insufficiencies that prevented educators from assisting students, a lack of resources, a lack of time, and a lack of personal capacity. Almost a quarter of the respondents (24.2%) indicated that insufficient resources were an issue. One respondent expressed, “I am stymied when student issues are financial. I have no resources to connect student with,” and another respondent described, “long wait lists at counseling services.” Educators described limited student capacity to use resources. A participant explained, “even when campus and community referral sources are available students may not have resources (e.g., money, insurance, time, transportation, technology, child-care, etc.) to access them.” Educators also identified limited time (12.9%) as a challenge. One respondent noted, “I think the biggest barrier is time,” and another explained, “Time to create engagement/relationships that allow for student sharing.” Most of the respondents described their own limited time, but they also recognized that students have limited time to help themselves. Limited educator capacity was a concern for 8.8% of the respondents. A respondent shared, “So many of them and not so much of me…” Often this was about the educator’s personal wellbeing or emotional response such as the respondent who stated, “It can seem very overwhelming and daunting,” and the educator who explained, “It seems that there is little attention paid to faculty members’ own wellness, which causes a trickle-down effect for faculty members to offer support to students.” Capacity was also limited by other work demands as one educator explained, “work-life balance, too many students to prioritize.” Educators also recognized personal inability to help students, such as the participant who stated, “Most of what they need is not in my toolbox.”

Balancing Educator Role & Boundaries was identified by 16% of the respondents as a barrier to supporting student wellness. Respondents could perceive the educator role as incompatible with addressing wellness needs of students, such as the educator who stated, “I’m their teacher not their parent, friend or partner,” and the respondent who described, “boundaries, and not treating my students as my clients.” For others it was more of a struggle to find the right boundaries, even if they felt the same clarity of role. One educator shared, “I am trying to find a balance in educating, ensuring students have the tools they need to succeed but also holding a standard of care and expectations of performance. This is a personal barrier I am working through while developing my teaching philosophy” and another educator explained, “boundaries … I feel okay supporting them and providing resources, but possibly a barrier to them is that I maintain boundaries with my role.” Educators described internal struggles about the extent they should accommodate students. One respondent stated, “Balanced with supporting student wellness is the need to support student responsibility both part of professional practice, but occasionally these two pieces of the balance conflict.” One educator described concern about whether informal accommodations help or interfere with student learning:

I find that their school work often takes the backseat and at times I see them using my flexibility as a way to prioritize other areas. I feel conflicted about this because their learning is important but I also know that if I allow them an extension then they are likely going to do better work which is why I usually grant the extension. I do think we need to help students with time management skills as a means of supporting their wellness.

Educators also expressed concern that a focus on wellness could detract from learning. One respondent explained:

I find that some students can have very high needs and expect a lot of accommodations for those needs. This can be disruptive to the class flow as they complete things at different times. I also get students who want less work due to outside needs. While I want to be understanding of course, the course is set up for students to learn the material and when students want less work in order to focus on their wellness, they do not learn what they need to.

Respondents (21.1%) identified Environment Factors complicating efforts to address student wellness needs. 7.2% noted that the policies of the department, university, or government presented challenges. An educator explained, “institutional structures (semesters, pre-requisites, scholarship rules that require completion of 30 credit hours per year) can become barriers to success.” Respondents recognized the social work programs themselves could contribute to student distress. One educator wrote, “Often it is the design of our program itself that is causing stress but I feel as though I can only help in very limited ways that are very specific to class.” Another educator asserted that “School policies are often rigid and are not friendly to being flexible in modifying academic plans or extending time to complete a degree.” Some educators described a lack of support by those in leadership for wellness efforts. One educator blamed a “lack of having the work valued by upper administration,” and another noted, “Often students and the larger administration put the burden of student wellness on faculty members, who are often underpaid and have multiple jobs/responsibilities.” Respondents’ professional demands limited their focus on student wellness. A respondent claimed, “Our workloads keep increasing.”

Fellow faculty’s influence on the environment could also complicate educator efforts to support students (5.2%). Some respondents perceived colleagues as unnecessarily rigid, such as the educator who explained, “Other faculty who see giving legitimate accommodations as loosening academic rigor.” Respondents thought colleagues has unreasonable expectations. One educator described, “The institutional/academic culture within the professoriate which is evidenced by frequent ‘busy work’ for students along with the sense that students need to jump through the same hoops that we had to jump through when going through school.” Another educator recognized colleagues not considering diverse student experiences, “Cultural Humility in my area (or lack thereof).”

Several respondents (4.6%) credited the online class environment as complicating attention to student wellness. Virtual classrooms could limit spontaneous communication. One educator stated, “online learning offers little in the way of those informal before and after class moments” and another educator wrote, “teaching online- less conducive for many of these discussions.” Some respondents noted that online students did not have access to local wellness resources available for in person students, such as the educator who said, “For our online programs the students don’t have access to the same resources the campus students do.”

Multiple respondents (4.1%) recognized structural oppressions as the main barrier to student wellness. Respondents named systemic oppressive factors interfering with student wellness. One educator explained, “the hoops were unrealistic, rooted in white supremacy and often times meant to disadvantage or keep women and/or scholars of color excluded,” and another noted, “Institutional barriers are the greatest barriers to wellness, namely racism, misogyny, transphobia, homophobia, ableism, etc. These barriers all get tethered to one another in and through racial capitalism, of course, which subjugates humans into producers.” These social work educators emphasized that the issues need to be addressed on a large scale, such as the respondent who stated, “Students are poor and there is little faculty can so in the classroom or a university food pantry can do to change the structural and generational issues of poverty.” They also expressed concern that emphasizing individual supports could interfere with larger changes, such as the educator who wrote, “These kinds of individual requests can muddy the waters for creating systemic change – that’s the kind of change we need.” Several faculty mentioned that stigmatized systems interfere with students being willing to seek help. A participant noted, “There is a stigma with mental health, asking for help, etc.”

Faculty (9.3%) described Students Interactions as complicating their efforts to support student wellness. 6.2% of the respondents described students being unwilling to seek assistance. One educator noted, “The student not taking ownership or being proactive in their own wellbeing/needs,” and another educator asserted, “Sometimes students are reluctant to share what they need.” Respondents described students refusing to adjust their course plan. One participant described, “I encourage them to take a LOA so that they do not fail, they often refuse BUT want faculty to continue to accommodate,” and another educator stated, “Student wellness sometimes conflicts with the student’s desire to graduate by a certain time.” A few educators described student reluctance to learn about wellness as interfering. A respondent wrote, “Student willingness to take part in self-care or wellness. Some see a day or time spent talking about taking care of self as a waste and not part of what they are supposed to be learning.”

Another barrier described by faculty (2.6%) was not being aware of student wellness needs. Sometimes educators attributed this to workload such as the educator who described, “With a large number of advisees and students in the overall program, I often am not aware of student specific needs.” At other times they attributed this to student choice, such as the participant who stated, “Sometimes students are reluctant to share what they need.”

One respondent noted that it may be the cultural differences between themselves and students that could interfere with supporting student wellness.

The Complexity of Student Challenges (5.2%) itself was a barrier to helping student wellness. Educators recognized the multiple pressures students face which could make it harder to help students focus on wellness. An educator stated, “Most students work and go to school. In addition, many care for families. These competing demands make it hard for students to focus on self.” Respondents noted that students’ personal challenges could be a barrier. A respondent described, “their lives are so complicated. They have many competing responsibilities, past traumas, and social struggles.” Respondents recognized a plurality of issues could make it difficult for students to attend to learning. One educator noted, “Many students are struggling with multiple issues, including financial and personal, which make it difficult to engage them at times.” Sometimes the extent of these student issues could discourage educators. A respondent stated, “the reality that these students have an incredible amount of demands and sometimes there is only so much you can do when the circumstances are just really hard.”

A few respondents (2.6%) reported experiencing no barriers when supporting student wellness.

Discussion

Amid calls in the literature to thoughtfully address social work student mental health (Todd et al., Citation2019), efforts to improve student self-care (Grise-Owens et al., Citation2018), and to provide greater financial stability for students (Trawver et al., Citation2020), this study helps focus on what educators encounter when trying to address these concerns. By understanding what motivates educators and what is getting in their way, social work educators and administrators can alter systems to provide effective support for students and clarity for their faculty. The findings demonstrate that similar issues were articulated from the perspective of what supports educators and from the perspective of what impedes educators’ efforts. Mindful of respondents’ perception of both supports and barriers, five considerations from this analysis will be explored in depth: resource availability, environmental culture, student partnership, wellness centered pedagogy, and oppressive forces.

Resource availability

The presence or absence of resources (including personal capacity and wellness) was the most prominently discussed factor. Access to resources to support students aligns with limitations of resources as a barrier and is consistent with other literature emphasizing the need for universities to assist with addressing basic needs (Martinez et al., Citation2021). Researchers also recommend universities collaborate with local community resources to enhance opportunities for students to pursue and obtain appropriate assistance in whatever way works better for them (Haskett et al., Citation2021). The great extent to which college students are struggling with food insecurity demands institutional interventions to ameliorate these educational barriers (Lanza et al., Citation2022). Studies have shown that when students perceive they have resources available to them at a university, their sense of wellbeing increases (Shine et al., Citation2021). In our study, it was not just whether a university had scholarships, food pantries, and counseling available, but also whether educators had the time or personal capacity to get involved. Literature demonstrates that students are more likely to effectively access resources if they have supportive relationships with university employees who help make the referral (Crutchfield et al., Citation2020a); however, most educators do not have time secured for such activities. As some of our participants noted, the resources that need enhancing may also be the wellbeing of the social work educators themselves, since we cannot teach self-care if we are not effectively modeling self-care (Clary & Hernandez, Citation2022) and current social work educators are at great risk for burnout (Chiarelli-Helminiak et al., Citation2022).

Environmental culture

The environment was a major factor for participants in facilitating or interfering with instructor efforts to support student wellness, primarily whether these efforts were supported by their peers, the department, and university leadership. This aligns with research by Travia et al. (Citation2022) documenting that when leadership supports wellbeing initiatives they are embraced more broadly across campus. Colleagues in our study were viewed as helpful when validating struggles, supporting each other’s efforts, and contributing to a culture of care and similarly problematic when dismissive of efforts or rigid in expectations. However, it is not surprising to find among our participants clashes in views when efforts some educators make to address student wellness are perceived as violations to the boundary of the educator role by other educators. This boundary struggle may require direct exploration within social work academia. Todd et al. (Citation2019) article on social work education’s response to student mental health needs recommend strategies that schools employ to effectively support students so that responses are a part of our regular functioning, rather than an adjustment made for an atypical student. Addressing all student wellness needs in a way that effectively integrates with competency-based learning may require more consistency of expectations around who is or is not responsible to respond to student needs. Because educators are also trying to maintain their own wellbeing while teaching and supporting students, how the environment of the school or department addresses faculty and staff wellbeing is also relevant.

Student partnership

Our participants recognized the importance of student receptivity and action. Students (like all of us) will be in various stages of change when thinking about seeking help. Likely factors influencing student communication could include personal style, cultural norms, and self-awareness as well as a student’s comfort level with an educator. Measurements of student learning during the pandemic demonstrated a positive correlation between student engagement and their view of instructor concern (Hews et al., Citation2022). In Guzzardo et al. (Citation2021) qualitative study of students experiencing food or housing insecurity, students preferred more pedagogical flexibility and choice, they responded when faculty communicated a sense of belonging regardless of circumstance, they liked when instructors showed they were actively engaged and invested in student success, and they valued faculty who provided support beyond teaching. When students feel instructors care they may be more likely to consider disclosing difficulties or be more open to instructor suggestions.

Wellness-centered pedagogy

Many of the social work educators viewed rapport building and fostering community as an integral component of how they support student wellness needs. They are not perceiving these efforts as distinct from their knowledge sharing and skill building, but instead as a part of their teaching. Livingstone et al. (Citation2023) found that instructor flexibility and a sense of community with classmates were two inclusive teaching practices that helped students academically as they navigated the pandemic. Shine et al. (Citation2021) demonstrated that when students feel they matter to their peers, their sense of wellbeing increases. Students who have positive relationships with both their peers and their instructors describe more effective learning and better wellbeing (Pasquale & Pickerd, Citation2022; Upsher et al., Citation2022). Literature written as educators were supporting virtual students during the pandemic emphasized the boundary challenging narrative that showing love for students is a part of the teaching (Gates et al., Citation2022). Creation of community to support learning is not limited to what occurs within the classroom. When students perceive their university as providing financial support or food access, they believe that their faculty and administrators care about them (Crutchfield et al., Citation2020a). This goodwill can enhance student investment in learning.

Beyond general concern for student wellbeing, educators calling for self-care integration into social work education keeps growing (Griffiths et al., Citation2019; Grise-Owens & Miller, Citation2021; Newell, Citation2020; Xu et al., Citation2019). This effort is supported by the Council on Council on Social Work Education (CSWE) Citation2022 Educational Policy and Accreditation Standards (EPAS) which require that social work students be taught about self-care and the 2021 revisions to the National Association of Social Workers Code of Ethics National Association of Social Workers (NASW) Citation2021 which directs social workers to practice self-care. Our respondents’ description of fostering students’ coping strategies and time management skills suggests educators are assisting students develop capacities to manage life challenges. This is necessary education since students’ usage of negative coping strategies to respond to college pressures can exacerbate the distress for the students (Stallman et al., Citation2022).

Oppressive structural forces

Our social work respondents who highlighted the systemic issues and oppressive structures resulting in financial and emotional burdens for students remind all educators to be looking for ways to address these issues broadly rather than limit efforts to immediate student need. As in all aspects of social work, the efforts made to strengthen and support individuals should not distract from opportunities to change systems and increase justice. When local or large-scale policies and practices are problematizing student access to resources, we have obligations to change those policies (Crutchfield et al., Citation2020a). A celebrated example is the No Excuses Poverty Initiative at Amarillo College which saw dramatic completion improvements once systematic poverty barriers were reduced for students and university departments focused more on contributing to a university-wide “culture of caring” (Lowery-Hart, Citation2020, p. 39). Another example is California’s decision to waive work requirements for college students seeking SNAP food support, leading to improved student retainment (Balzer Carr & London, Citation2020). A school-focused initiative conducted at Bunker Hill Community College, where students who were known to meet criteria were proactively offered meal voucher debit cards without needing to prove their eligibility, was also linked to improved student success (Broton et al., Citation2020a, Citation2022). While these examples are not eliminating fundamental inequities, they are finding broader ways to address them and reduce student burdens.

Recommendations for social work educators and administrators

Based upon this study and recent literature, the following recommendations are offered to social work educators and administrators thinking about the intersection between efforts to help students meet competencies and strengthen student wellness.

Create opportunities for faculty and staff to dialogue about wellness

Faculty have differing views on boundaries, wellness course content, appropriate efforts and styles of supporting students, and flexibility. Rather than inadvertently working at counter purposes, having a culture where faculty resent each other for differing views, or classrooms where students are confused because of inconsistent expectations, program directors and department chairs can help faculty articulate their shared goals in ensuring learning and promoting wellness. Working in solidarity on shared goals, faculty can develop policies and practices that interweave flexibility with accountability. When supporting student wellness is viewed as directly improving learning, then educators can document these efforts within their teaching portfolios and service to the school.

These dialogs also provide a platform for faculty to identify specific strategies in the workplace that can help them with their own wellness. Social work educators benefit from feeling their institutions promote their personal self-care (Myers et al., Citation2022). The more balanced and refreshed faculty and staff are, the more effectively they can train and support students.

Strengthen social work faculty and staff’s familiarity with available resources

Some faculty will be experts on resources and others will not be. Creating space where the experts can train peers, or inviting representatives from campus or community offices to educate faculty and staff on resource opportunities can increase the chance that students will receive effective referrals. As Crutchfield et al. (Citation2020a) recommend, faculty and staff need training on available resources and referral techniques to increase the chance that students will access them. Limited university employee awareness of resources directly impedes effective referrals (Karlin & Martin, Citation2020). Faculty and staff can explore ways to incorporate resource information into syllabi, e-mail signatures, class discussions, and student meetings, and normalize resource utilization.

Change policies, procedures, and systems in ways that will contribute to overall student wellness and reduce inequity

Mindful of the practices of our schools and issues in society that cause or contribute to student distress, social work’s commitment to micro and macro work can instigate both systemic and policy change and offer direct support to ameliorate student distress. As social work institutions integrate and expand their commitment to anti-racism, diversity, equity, and inclusion, altering educational policies can directly increase wellness through helping students feel more valued and appreciated. Faculty-developed policies around attendance, absences, late assignments, and similar factors could be created with consideration of student wellness needs and student growth. This offers consistency across classes making it simpler for students and faculty (especially part-time faculty).

Find ways to alleviate time burdens

Time constraints interfere with educators’ capacity to support student wellness and increase educator exhaustion. Meetings can be shortened, reduced in frequency, or limited to certain days. Exploring methods to reduce pressures on individual instructors could also open possibilities. Maybe an additional advisor or a student advocate could be hired as an alternate way to support students.

While not a direct finding of this study, part time faculty, adjunct faculty, and doctoral students contributed to the surveys. As many schools of social work rely upon part time faculty to help teach their classes, they should be included in the efforts to strengthen wellness.

Limitations

This study offers insights about minimally explored social work educator perspectives, yet a limitation is that it is a small study using a convenience sample. Response bias is likely as only educators who saw this study in an e-mail, wanted to complete a survey about student wellness, and had the time to participate, are represented in the results. Another limitation was that the majority of respondents were white and identified as female. According to the National Association of Social Workers (Citation2020), 90% of new social workers who enter the field are women and about 36% are Black/African American or Hispanic/Latino, demonstrating much greater racial diversity among social workers than were reflected in our respondents. Further research is needed to better understand how social work educators of color, social work educators who identify as male, and social workers with nonbinary gender identities experience addressing student wellness needs. Because oppressive systems are major factors negatively affecting students, and social work educators have experienced these systems in different ways, research is needed to explore the ways social work educator identities could influence personal efforts and views around supporting struggling students and addressing problematic educational systems.

Conclusion

Whether because of severity of student need, growing appreciation for how learning is negatively correlated with stress, or social justice convictions, there appears to be a growing focus on student wellness needs in social work education. As demonstrated in the study, social work educators do not all perceive student wellness needs in the same way and they face an assortment of challenges in trying to address them. Schools and departments of social work that discuss the ways wellness interacts with student learning and the practices they want to employ to balance learning and accountability have opportunities to intentionally build supports and reduce barriers their educators face when working with students. More effectively trained social workers will better impact our society.

Social workers do their best work when addressing both the micro- and the macro-finding ways to make classrooms and departments more supportive of student wellbeing and working to eliminate the inequities that contribute to these issues. The significance of the challenges wrought by impaired student wellbeing requires multiple types and layers of interventions (Coakley et al., Citation2022) especially as higher education reimagines ways to better meet the needs of today's diverse student body (Bahrainwala, Citation2020). These days social work educators are often considering the needs of their students beyond the classroom when preparing them to serve their communities and clients. Identifying ways social work educators feel supported when addressing student wellness needs will help educators and administrators strengthen their classrooms and policies for the good of future clients.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Bahrainwala, L. (2020). Precarity, citizenship, and the “traditional” student. Wicked problems forum: Student precarity in higher education. Communication Education, 69(2), 250–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634523.2020.1723805

- Balzer Carr, B., & London, R. A. (2020). Healthy, housed, and well-fed: Exploring basic needs support programming in the context of university student success. AERA Open, 6(4), 233285842097261. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332858420972619

- Broton, K. M., Goldrick-Rab, S., & Mohebali, M. (2020a). Fuel-ing success: An experimental evaluation of a community college meal voucher program. The Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice. https://hope4college.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/BunkerHill_Report.pdf

- Broton, K. M., Mohebali, M., & Goldrick-Rab, S. (2022). Deconstructing assumptions about college students with basic needs insecurity: Insights from a meal voucher program. Journal of College Student Development, 63(2), 229–234. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2022.0018

- Chiarelli-Helminiak, C. M., McDonald, K. W., Tower, L. E., Hodge, D. M., & Faul, A. C. (2022). Burnout among social work educators: An eco-logical systems perspective. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 32(7), 931–950. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2021.1977209

- Clary, K. L., & Hernandez, L. M. (2022). Dear social work educators, teach and model self-care. Reflections: Narratives of Professional Helping, 28(1), 7–20.

- Coakley, K. E., Cargas, S., Walsh-Dilley, M., & Mechler, H. (2022). Basic needs insecurities are associated with anxiety, depression, and poor health among university students in the state of New Mexico. Journal of Community Health, 47(3), 454–463. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-022-01073-9

- Cortina, L., (2022, May 11). Hunger gains: UMB student pantry takes a bite out of food insecurity.Catalyst. https://catalystmag.umaryland.edu/hunger-gains-umb-student-pantry-takes-a-bite-out-of-food-insecurity/

- Council on Social Work Education (CSWE). (2022). 2022 educational policy and accreditation standards. https://www.cswe.org/accreditation/standards/2022-epas/

- Crutchfield, R. M., Chambers, R. M., Carpena, A., & McCloyn, T. N. (2020a). Getting help: An exploration of student experiences with a campus program addressing basic needs insecurity. Journal of Social Distress and Homelessness, 29(1), 16–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/10530789.2020.1677010

- Crutchfield, R. M., Maguire, J., Campbell, C. D., Lohay, D., Valverde Loscko, S., & Simon, R. (2020). “I’m supposed to be helping others”: Exploring food insecurity and homelessness for social work students. Journal of Social Work Education, 56(1), S150–S162. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2020.1741478

- Elo, S., Kääriäinen, M., Kanste, O., Pölkki, T., Utriainen, K., & Kyngäs, H. (2014). Qualitative content analysis: A focus on trustworthiness. SAGE Open, 4(1), 215824401452263. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244014522633

- Florida State University. (2023, March 14). Professional certification in college student wellbeing, Trauma, and Resilience. https://learningforlife.fsu.edu/professional-certification-college-student-wellbeing/

- Gates, T. G., Ross, D., Bennett, B., & Jonathan, K. (2022). Teaching mental health and well-being online in a crisis: Fostering love and self-compassion in clinical social work education. Clinical Social Work Journal, 50(1), 22–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-021-00786-z

- Gockel, A., Deng, X., Gleeson, S., & Leamon, A. (2019). The serene student: Evaluating a group-based mindfulness training program for MSW students. Social Work with Groups, 42(4), 275–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/01609513.2019.1571759

- Griffiths, A., Royse, D., Murphy, A., & Starks, S. (2019). Self-care practice in social work education: A systematic review of interventions. Journal of Social Work Education, 55(1), 102–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2018.1491358

- Grise-Owens, E., & Miller, J. (2021). The role and responsibility of social work education in promoting practitioner self-care. Journal of Social Work Education, 57(4), 636–648. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2021.1951414

- Grise-Owens, E., Miller, J., Escobar-Ratliff, L., & George, N. (2018). Teaching note–teaching self-care and wellness as a professional practice skill: A curricular case example. Journal of Social Work Education, 54(1), 180–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2017.1308778

- Guzzardo, M. T., Khosla, N., Adams, A. L., Bussmann, J. D., Engelman, A., Ingraham, N., Gamba, R., Jones-Bey, A., Moore, M. D., Toosi, N. R., & Taylor, S. (2021). “The ones that care make all the difference”: Perspectives on student-faculty relationships. Innovative Higher Education, 46(1), 41–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-020-09522-w

- Haskett, M. E., Majumder, S., Kotter- Grühn, D., & Gutierrez, I. (2021). The role of university students’ wellness in links between homelessness, food insecurity, and academic success. Journal of Social Distress and the Homeless, 30(1), 59–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/10530789.2020.1733815

- Hege, A., Stephenson, T., Pennell, M., Revlett, B., VanMeter, C., Stahl, D., Oo, K., Bressler, J., & Crosby, C. (2021). College food insecurity: Implications on student success and applications for future practice. Journal of Student Affairs Research & Practice, 58(1), 44–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/19496591.2020.1726359

- Hews, R., McNamara, J., & Nay, Z. (2022). Prioritising lifeload over learning load: Understanding postpandemic student engagement. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 19(2), 128–146. https://doi.org/10.53761/1.19.2.9

- Jeffries, V., & Salzer, M. S. (2022). Mental health symptoms and academic achievement factors. Journal of American College Health, 70(8), 2262–2265. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2020.1865377

- Karlin, A., & Martin, B. N. (2020). Homelessness in higher education is not a myth: What should educators be doing? Higher Education Studies, 10(2), 164–175. https://doi.org/10.5539/hes.v10n2p164

- Kim, Y., Murphy, J., Craft, K., Waters, L., & Gooden, B. I. (2022). “It’s just a constant concern in the back of my mind”: Lived experiences of college food insecurity. Journal of American College Health. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2022.2064714

- Lanza, S. T., Whetzel, C. A., Linden Carmichael, A. N., Newschaffer, C. J., & Kim, J. I. (2022). Change in college student health and well-being profiles as a function of the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE, 17(5), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0267724

- Leung, C. W., Farooqui, S., Wolfson, J. A., & Cohen, A. J. (2021). Understanding the cumulative burden of basic needs insecurities: Associations with health and academic achievement among college students. American Journal of Health Promotion, 35(2), 275–278. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890117120946210

- Livingstone, S., Adrian, J., & Heinrichsen, E. T. (2023). Translating student voices into action: A call for equitable teaching practices amidst growing basic needs challenges. Transformative Dialogues: Teaching & Learning Journal, 15(3), 33–54. https://doi.org/10.26209/td2023vol15iss31768

- Lowery-Hart, R. (2020). Love students to success: How a culture of caring closed equity gaps. Diverse Issues in Higher Education, 37(19), 39.

- Maddock, A., McCusker, P., Blair, C., & Roulston, A. (2022). The mindfulness-based social work and self-care programme: A mixed methods evaluation study. The British Journal of Social Work, 52(5), 2760–2777. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcab203

- Martinez, S. M., Esaryk, E. E., Moffat L., Ritchie, L. (2021). Redefining basic needs for higher education: It’s more than minimal food and housing according to California University students. American Journal of Health Promotion, 35(6), 818–834. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890117121992295

- Meza, A., Altman, E., Martinez, S., & Leung, C. W. (2019). “It’s a feeling that one is not worth food”: A qualitative study exploring the psychosocial experience and academic consequences of food insecurity among college students. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition & Dietetics, 119(10), 1713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2018.09.006

- Myers, K., Martin, E., & Brickman, K. (2022). Protecting others from ourselves: Self-care in social work educators. Social Work Education, 41(4), 577–586. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2020.1861243

- National Association of Social Workers. (2020, December 11). New report provides insights into new social workers’ demographics, income, and job satisfaction. NASW. https://www.socialworkers.org/News/News-Releases/ID/2262/New-Report-Provides-Insights-into-New-Social-Workers-Demographics-Income-and-Job-Satisfaction

- National Association of Social Workers (NASW). (2021). Code of ethics. https://www.socialworkers.org/About/Ethics/Code-of-Ethics/Code-of-Ethics-English

- Newell, J. M. (2020). An Ecological systems framework for professional resilience in social work practice. Social Work, 65(1), 65–73. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/swz044

- Notar, M. K. (2022). Mindfulness 101: MSW students’ reflections on developing a personal mindfulness meditation practice. Journal of Social Work Education, 58(4), 667–681. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2021.1943583

- Ogden, L. P., & Rogerson, C. V. (2021). Positive social work education: Results from a classroom trial. Social Work Education, 40(5), 656–670. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2019.1704723

- Pasquale, M., & Pickerd, B. (2022). Learning, student well-being, and the classroom: Reimagining a class through focus on community. InSight: A Journal of Scholarly Teaching, 17, 83–98. https://doi.org/10.46504/17202205pa

- Shine, D., Britton, A. J., Dos Santos, W., Hellkamp, K., Ugartemendia, Z., Moore, K., & Stefanou, C. (2021). The role of mattering and institutional resources on college Student well-being. College Student Journal, 55(3), 281–292.

- Stallman, H. M., Lipson, S. K., Zhou, S., & Eisenberg, D. (2022). How do university students cope? An exploration of the health theory of coping in a US sample. Journal of American College Health, 70(4), 1179–1185. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2020.1789149

- Steve Hicks School of Social Work. (2023, June 30). Food pantry. The University of Texas at Austin. https://socialwork.utexas.edu/student-resources/financial/food-pantry/

- Todd, S., Asakura, K., Morris, B., Eagle, B., & Park, G. (2019). Responding to student mental health concerns in social work education: Reflective questions for social work educators. Social Work Education, 38(6), 779–796. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2018.1563591

- Travia, R. M., Larcus, J. G., Andes, S., & Gomes, P. G. (2022). Framing well-being in a college campus setting. Journal of American College Health, 70(3), 758–772. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2020.1763369

- Trawver, K., Broton, K. M., Maguire, J., & Crutchfield, R. (2020). Researching food and housing insecurity among America’s college students: Lessons learned and future steps. Journal of Social Distress and the Homeless, 29(1), 39–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/10530789.2020.1678809

- University of Buffalo School of Social Work. (2023). Self-care starter kit. https://socialwork.buffalo.edu/resources/self-care-starter-kit.html

- University of Kentucky College of Social Work. (2023, March 14). Self care lab- university of Kentucky college of social work. https://socialwork.uky.edu/centers-labs/self-care-lab/

- Upsher, R., Percy, Z., Cappiello, L., Byrom, N., Hughes, G., Oates, J., Nobili, A., Rakow, K., Anaukwu, C., & Foster, J. (2022). Understanding how the university curriculum impacts student wellbeing: A qualitative study. Higher Education, 86(5), 1213–1232. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00969-8

- Vears, D. F., & Gillam, L. (2022). Inductive content analysis: A guide for beginning qualitative researchers. Focus on Health Professional Education, 23(1), 111–127. https://doi.org/10.11157/fohpe.v23i1.544

- Warren, S., & Deckert, J. C. (2020). Contemplative practices for self-care in the social work classroom. Social Work, 65(1), 11–20. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/swz039

- Xu, Y., Harmon-Darrow, C., & Frey, J. J. (2019). Rethinking professional quality of life for social workers: Inclusion of ecological self-care barriers. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 29(1), 11–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2018.1452814