ABSTRACT

Using the framework of conversation analysis, this paper examines aided-speaking students’ unsolicited speech-generating device (SGD)-mediated questions in teacher-fronted classroom talk. The analysis draws on a corpus of 18 h of video-recorded classroom interactions including 23 aided-speaking students using SGDs or picture-based communication boards. In all, 5% of the students’ contributions were unsolicited questions, produced by three students. The students were found to orient to turn transition relevance places, but due to prolonged production time their questions risked sequential and topical misplacement in the ongoing classroom talk and were vulnerable to misunderstandings. To address this problem, students activated the synthetic voice before finalising the question, claiming the interactional floor while securing time to complete their utterance. They also refrained from activating the synthetic voice and instead made the question visually available for the teacher to read, thereby transferring the responsibility for answering the question to the teacher when sequentially and topically relevant. The study demonstrates the complex interactional process of formulating SGD-mediated questions, sometimes requiring that the teacher, assistants, and students engage in repair work and scaffolding to establish the meaning of a student’s utterance. The findings imply that the treatment of non-speaking students’ contributions as questions requires designated teacher work.

1. Introduction

Students’ questions play an important role in the learning process for students as well as for teachers (Chin and Osborne Citation2008). By asking questions, students may articulate and self-evaluate their own understanding of a subject. They may search for knowledge, elicit explanations, and offer solutions to problems as they suggest possible ways of reasoning and make hypotheses. Asking questions in class may also stimulate other students’ thinking and understanding. Questions may moreover work as a clue for teachers to determine students’ comprehension, motivation, and interest (Chin and Osborne Citation2008).

Students’ questions can be solicited (following invitations from teachers) or unsolicited (without invitations from teachers) (Jacknick Citation2009, 69). In this study, students’ unsolicited contributions are in focus, or what Waring (Citation2011) defines as ‘learner-initiatives’, that is, ‘any learner attempt to make an uninvited contribution in the ongoing classroom talk, where “uninvited” may refer to (1) not being specifically selected as the next speaker or (2) not providing the expected response when selected’ (Waring Citation2011, 204). Unsolicited initiatives gain the main interactional floor (i.e. take the turn) in teacher-fronted classroom talk and have been shown to do different social actions, such as (dis)agreement, hypothesis testing, counter-response, and requesting information or confirmation (Duran and Sert Citation2021; Garton Citation2012; Sert Citation2017; Solem Citation2016a, Citation2016b; van Balen et al. Citation2022; Waring Citation2011).

The data analysed in this article, are drawn from a study documenting interaction in classrooms populated with children who, due to severe physical impairments and lack of speech, communicate through speech-generating devices (SGDs), which they operate through eye-gaze technology. An SGD is an electronic speech output system that can be used to replace speech. The children in this study have severe physical impairments, which means that they cannot use iconic gestures, nodding or vocalisation. Their body movements are to a high degree involuntary: their gaze, non-iconic gestures etc. are limited, delayed, and distorted. Children with speech and language difficulties, have been shown to find it challenging to participate in whole-class interaction (e.g. Ekström et al. Citation2023) and children with a combination of lack of speech and severely limited repertoire of embodied resources rarely provide unsolicited contributions (Tegler et al. Citation2020). Building on the theoretical and analytical approach of Conversation Analysis (CA; e.g. Schegloff Citation2007), this study hence addresses the following research questions: How do aided-speaking students produce unsolicited questions in whole-class interactions? What interactional challenges are encountered by these children as they engage in teacher-fronted classroom talk? What methods do the students, the teacher and the assistants use to address the interactional challenges?

1.1. Student questions in teacher-fronted classroom talk

One of the basic assumptions of CA, is that talk-in-interaction is organised in sequences of turns or actions (Harvey, Schegloff, and Jefferson Citation1974; Schegloff Citation2007). A turn may consist of one or more turn-constructional units (TCUs) that are built and recognised through their grammatical and prosodic features as well as pragmatic actions (e.g. a question). As speakers approach the possible completion of a TCU, transition to a next speaker may become relevant, within what is called a transition-relevance place (TRP). A basic unit of sequence construction is the adjacency pair that is composed of two turns by different speakers and where a first action, a first pair part, initiates an exchange (e.g. a question) that is responded to in a second pair part (e.g. an answer) (Schegloff Citation2007).

Questions can be recognised by their grammar or by their prosody (Hayano Citation2012). Grammatically, questions can include a question-word, such as an interrogative pronoun (e.g. who) or an interrogative adverb (e.g. how, when, where). Questions can also be identified by their interrogative syntax, i.e. often initiated with an auxiliary verb (e.g. do, could, was) followed by a subject (e.g. you, we) and then the main verb (e.g. get) (Couper-Kuhlen and Selting Citation2018). Interrogatives are often polar questions in the shape of yes/no questions, which make relevant a narrower range of answers than question-word questions (Stivers Citation2010). Moreover, questions can be recognised by their prosodic features, most importantly final pitch rise (Couper-Kuhlen and Selting Citation2018), although studies of Swedish indicate that prosody is subordinate to syntax for the identification of turn-transition relevance places (TRPs; Bockgård Citation2007).

So far, research on students’ unsolicited questions in teacher-fronted classroom talk has concerned speaking students. Most research is on university students’ second language acquisition (Dolce and van Compernolle Citation2020; Duran and Sert Citation2021; Garton Citation2012; Merke Citation2018) or subject studies (Lindwall and Lymer Citation2014). Analysis shows that adult students’ unsolicited questions can work as confirmation checks, information requests, and hypothesis testing. They often include a pre-sequence (e.g. ‘I have a question’) that works to claim the turn in which the student can ask the question.

Studies of children’s and teenagers’ unsolicited questions are rare. The identified studies show that teachers, by use of scaffolding practices, can increase students’ opportunities to ask unsolicited questions. For example, Church and Bateman (Citation2019) showed how pre-school teachers’ expansions, instead of minimal acknowledgements, created opportunities for pre-school children to ask unsolicited question in pedagogical activities. Studies on students in middle school (grade 5–8), show that teachers’ practices of ignoring questions out of topic and scaffolding prolonged time can elicit unsolicited questions (Kardas Isler, Ufuk, and Sahin Citation2019). Furthermore, teachers’ practice of displaying that a question is contextually relevant through a combination of visual (gestures and gaze) and auditive (final falling pitch and silence) practices may also elicit unsolicited questions (Kääntä and Kasper Citation2018). Findings from research on (upper) secondary students resemble research on university students: students’ unsolicited questions work as requests for clarification, displays of understanding and ways of expressing subjectification (Solem Citation2016b; van Balen et al. Citation2022). Taken together, these studies evidence that unsolicited student questions frequently occur in regular classrooms and that they play an important role for active student participation, understanding and learning. We now turn to research on aided-speaking students, first introducing some of the circumstances of interaction using speech-generating devices.

1.2. Interaction using speech-generating devices

Approximately 8% of school-aged children have speech and language difficulties, a disability that correlates with enhanced risk of academic failure and socio-emotional problems (Ekström et al. Citation2023; Norbury et al. Citation2016). In an interview study, children with speech and language difficulties reported that they ‘find it challenging to talk in class, both when assigned specific tasks involving formal presentations, and more informal activities, for example, raising their hand to take part in classroom interaction or ask for help’ (Ekström et al. Citation2023, 5). A subgroup of these children has such severe speech and language difficulties that they need augmentative and alternative communication (e.g. a speech-generating device) to replace speech.

Speech-generating devices (SGDs) range from simple battery driven one-message devices to computers with software programs that offer synthetic speech connected to picture-based symbols, letters or words on the screen. The aim of an SGD is to meet an aided-speaking individual’s daily communicative needs by replacing natural speech with synthetic speech (Light and McNaughton Citation2013). SGDs provide individuals with a voice, which can contribute to enhanced opportunities for participation.

Even though teachers report on the benefits of SGD-mediated interaction in educational contexts, they also report on the difficulties and barriers using SGDs in multiparty classroom talk (Andzik, Chung, and Kranak Citation2016; Chung, Carter, and Sisco Citation2012; Walker and Chung Citation2022). Previous research points out two major challenges: the prolonged production-time and the restricted vocabulary. Compared to speech, the production-time is prolonged (Higginbotham, Fulcher, and Jennifer Citation2016; Savolainen et al. Citation2020) and an SGD-mediated contribution easily becomes sequentially misplaced in ways that may aggravate understanding. Consequently, aided-speaking students have to prioritise between speed (i.e. delivering a contribution that is sequentially fitted) and accuracy (i.e. producing a comprehensible and grammatically correct contribution) (Auer and Hörmeyer Citation2017). Demands on speed may result in what (Auer and Hörmeyer Citation2017) describes as ‘incomplete utterances’ (i.e. unfinished contributions that lack linguistic units or consist of single words that work as semantic hints). The second challenge, restricted vocabulary, applies to illiterate students who use graphic symbols and not letters (Light and McNaughton Citation2012). Identifying a vocabulary that meets all needs in a variety of contexts is, if not impossible, very difficult. Accordingly, illiterate students will have access to a limited vocabulary that is determined by someone else, which in turn means that both students and communication partners (e.g. teachers and assistants) have to use synonyms and combinations of words/symbols in a creative way (e.g. combining two symbols to create a new concept). Research has shown that even when children have a large picture-based AAC system, they tend to use single-word messages and their sentences are often grammatically incorrect. Their contributions are typically shorter and less advanced than expected given their level of language comprehension (Binger and Light Citation2008).

Research on naturally occurring SGD-mediated interaction in classroom talk is scarce. The majority of studies are experimental and have examined the outcomes of specific interventions for students’ use of SGDs in classrooms (Bourque and Goldstein Citation2020; Lorah, Miller, and Griffen Citation2021; Thiemann-Bourque, McGuff, and Goldstein Citation2019). A few studies have used CA to investigate naturally occurring interaction in the school setting, but none have focused on unsolicited initiatives in teacher-fronted classroom talk. Instead, they have for example examined dyadic interaction outside the classroom (Clarke and Wilkinson Citation2007, Citation2008; Norén, Svensson, and Telford Citation2013). We have only found one study that investigates SGD-mediated interaction in teacher-fronted classroom talk, by focusing on SGD-mediated responses (Tegler et al. Citation2020). The analysis revealed that the responses were preceded by explicit turn allocation. None of the aided-speaking students in the study responded to questions that were posed to the whole group of students. The interactional pattern resembled typical IRE-sequences (Mehan Citation1979) in which the teacher initiated the interaction with a question that the student responded to, whereupon the teacher evaluated the response. Consequently, the students’ contributions consisted of solicited scaffolded second pair parts of question-answer sequences. SGD-mediated responses were co-constructed between the aided-speaking students, the teacher’s (or the assistant’s) scaffolding practices and the classmates. The teacher’s embodied actions (i.e. gaze orientation and pointing towards the SGD screen) and verbal guiding (e.g. commenting the process on the screen) worked to prolong the response space, as well as the classmates’ practice of waiting in silence (Tegler et al. Citation2020). In light of the limited research on interaction in classrooms populated by aided-speaking children, in combination with results from research on regular classrooms indicating the significance of student initiatives for active participation and learning, we set out to investigate the as yet unexplored area of unsolicited questions involving students who lack speech.

2. Method: empirical setting, data, and analytic approach

The present study is based on 18 hours of multiparty classroom interaction (26 lessons) recorded in 2018 and 2022 in nine Swedish schools, of which seven were special needs schools for children with intellectual disability and two were national upper-secondary schools for students with severe physical disabilityFootnote1. The inclusion criteria of the study were: (1) students (7–21 years old) who lacked speech and used an SGD or a communication boardFootnote2 for interaction in classrooms and (2) their teachers, (3) assistants and (4) classmates. In all, 119 individuals participated in the study. There were 23 aided-speaking students (7–19 years of age) in nine different schools and their 32 classmates, 15 teachers and 49 assistants. The majority of students (n = 15) followed the curriculum with five subject areas (i.e. physical coordination, aesthetics, everyday activities, communication and perception of reality). The remaining eight followed the curriculum that includes for, example, reading, writing and mathematics. Twelve students used an SGD and 13 used a picture-based communication board in paper. Four students were literate. Depending on the number of participating aided-speaking students per class, two to five cameras were used in order to capture the participants and the screen of their devices.

The teachers provided students and caregivers with written and oral information about the research project. Students with intellectual disability received easy-read information with pictures. Teachers, assistants, and students 18 years or older provided written consent. Younger students, and students who were not literate, consented by proxy (i.e. their caregiver consented). All names, places and other characteristics have been changed to ensure anonymity (Swedish Ethical Review Authority, reference number 2023-01166-01).

A comprehensive analysis showed that the 23 students provided 245 SGD- or communication board-mediated contributions (). Thirty-five contributions were categorised as questions. Twenty-two were solicited pre-stored questions (e.g. ‘what’s your name?’ or ‘what did you do yesterday?’) that the student asked after a prompt from the teacher. These contributions were excluded since the focus of this study is unsolicited questions.

Table 1. The 23 aided-speaking students’ SGD- or communication board mediated contributions in teacher-fronted classroom talk.

The theory and methodology of conversation analysis (CA) was used to analyse data (Sidnell and Stivers Citation2014). The basic objective is to describe the procedures deployed by interactants to produce actions, and to interpret the actions of others, as they build shared understanding on a turn-by-turn basis (Heritage Citation1984b). The analytic process began with a verbatim transcription of all data. Next, all SGD- or communication board mediated contributions were categorised into unsolicited or solicited questions, answers, requests, or comments ().

Thirteen unsolicited questions () were identified, transcribed according to Jefferson (Citation2004) (see Appendix A for symbols used here), and analysed in more detail. Of these, four excerpts, representative of the identified interactional patterns of the larger data set, were selected to demonstrate the interactional challenges that arise as aided-speaking students produce unsolicited SGD-mediated questions in whole-class interaction. The language spoken in the data is Swedish, and the excerpts have been translated into English.

Table 2. Maria’s, Vera’s and Nicholas’ unsolicited questions.

The 13 unsolicited questions were produced by three students – called Maria, Vera and Nicholas in the study – in two natural science lessons (). They were 19 years of age and had severe physical impairments, which meant that they lacked speech, were transported by wheelchairs, and could not use their hands or fingers to access their SGDs. Instead, they relied on eye-gaze technology, which meant that an infrared light on the SGD captured their eye movements and transformed their eye movements into the cursor on the screen. While Maria and Vera were literate and used letters and word prediction, Nicholas used Blissymbolics, a semantic graphic language (see Excerpt 4, ) (BCI Citation2023). It was not possible to configure the quality of the synthetic voice, such as adding prosodic features. The students’ language comprehension was assessed by a speech and language pathologist using the Test for Reception of Grammar- second edition (Bishop Citation2020). Maria’s language comprehension was age appropriate, Nicholas’ equalled typically developed 14-year-old children and Vera’s equalled typically developed 4-year-old children. None of them had an intellectual disability. In addition, there was a speaking classmate Lova (also 19-year-old), a personal assistantFootnote3 and a teacher in the classroom. Lova’s language comprehension was not assessed because she did not meet the criterion of inclusion. Nicholas had one personal assistant in the first lesson and another in the second lesson. Both personal assistants were men, 25–30 years of age. The teacher was a 60-year-old man with several years’ experience of teaching.

3. Analysis: aided-speaking unsolicited questions in teacher-fronted classroom talk

In the following section we will show how the SGD-mediated unsolicited questions selected for closer analysis emerged and developed in teacher-fronted classroom talk. The analysis is presented in two sections. The first section shows the students’ orientations to sequential placement and topical relevance when producing questions as well as the participants’ methods for dealing with the prolonged production time of the SGD (Excerpts 1–3). The second section demonstrates how the lack of a question word or interrogative syntax may affect the process of meaning-making. It explores how a student, assistant, and teacher work collaboratively to identify what the student is wondering about and shows the complex interactional process of scaffolding the formulation of an SGD-mediated question (Excerpt 4). The lessons were about the reproduction of plants, animals, and humans.

3.1. Sequential placement of SGD-mediated questions

The time producing a question ranged from 5 seconds to 5 minutes and 7 seconds with an average time of 1 minute and 44 seconds (). This meant that all questions were produced in parallel with the teacher’s talk. Consequently, there was a constant risk that questions would receive a sequentially misplaced position in relation to the ongoing classroom interaction and that this could obstruct understanding.

3.1.1. Orienting towards a transition relevance place

Before looking at the challenges resulting from the prolonged production process, we will focus on the students’ orientation towards a possible transition relevance place (TRP) when activating the synthetic speech by gazing at the symbol ‘speak’ on the screen. The analysis showed that the students often coordinated their questions with the teacher’s talk and searched for a relevant place for turn transition (Harvey, Schegloff, and Jefferson Citation1974). By doing this, they showed recognition of typical turn-taking practices. Excerpt 1 is a case in point.

When Excerpt 1 starts, the teacher (T) is telling the class about a hormone called LH, which is an abbreviation of luteinising hormones that play an important role in the female reproduction system. Maria (M) starts to compose her question (line 2) in overlap with the teacher’s talk. She operates her SGD by eye-gaze technology and looks at the symbol ‘abc’ that is linked to the keyboard with letters.

Excerpt 1 Why can become miscarriage or get little oxygen

May 5th (00:11:05- 00:12:17)

Maria continues to compose her question in parallel with the teacher’s talk about luteinising hormones and adds the last word ‘oxygen’ to her question in line 31. However, she does not activate ‘speak’ but waits until the teacher approaches turn completion, which is seen in line 34 when he says ‘and sinks back then’.

Maria activates ‘speak’ (line 35), but due to the 0.5 second gap between activating the symbol on the SGD and the sound of the speech output voice, the question is produced in the midst of the teacher’s prolonged turn that is cut off (line 36). With her question ‘why can become miscarriage or get little oxygen’ (line 37), Maria both displays knowledge of foetal and birth related complications and searches for additional knowledge that will support a deeper understanding of the subject. The teacher acknowledges with a minimal agreement token ‘yeah’ (Schegloff Citation2007, 95–96) and reorients towards the planned progression of the lesson ‘we’ll get to that later’. Maria’s contribution starts with an interrogative adverb, a question-word that indicates request for information. The teacher responds to the question without delay, displaying that the question-word and the two content words ‘miscarriage’ and ‘little oxygen’ are enough for understanding the question, and for deciding that the subject of the question will be dealt with at a later stage.

In sum, the analysis shows that the students oriented to typical turn-taking rules. However, this turn-taking competence was often hidden because of the time gap between activating a symbol and the synthetic voice output.

3.1.2. Holding the turn by activating ‘speak’ before completing the question

As demonstrated, the students oriented to TRPs when producing their contributions. Data also shows that they sometimes activated ‘speak’ during the teacher’s turn before completing the question: a practice for dealing with the slow production time that worked to hold the turn and to pause the progression of the lesson.

In Excerpt 2, the teacher talks to the class about three methods for internal fertilisation, here insemination. He explains that this method is very common in cattle breeding and that the insemination is done with the help of a semen applicator.

Excerpt 2 What does it look like syringe

May 5th (00:44:42 – 00:45:38)

The teacher explains the procedure of insemination (lines 1–11). The teacher’s explanation includes details that Maria responds to with a non-lexical interjection ‘ae:j’ (line 7) resembling a response cry (Goffman Citation1978), details that she will ask a question about further on. After a gap of 3.5 seconds, the teacher states ‘that was number two’ (line 13), preparing to move forward with the third method. At this stage, Maria starts to compose a question starting with an interrogative adverb ‘how’ (line 14), followed by ‘look’ (not in excerpt) and ‘it’ (line 21).

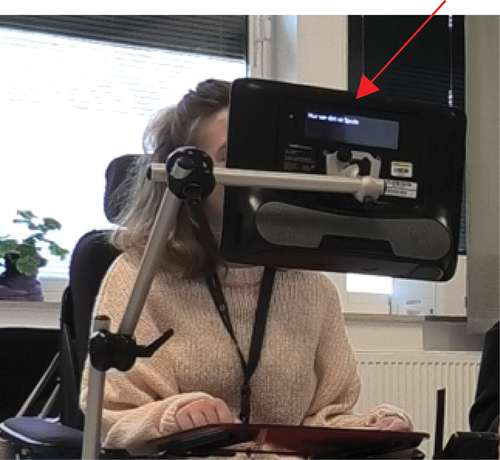

Figure 2. The partner window at the back of Maria’s speech-generating device.

The teacher shifts to the third fertilisation method (line 20) and asks the class ‘do you know what that is’ (line 22). Toward the end of the teacher’s turn Maria activates ‘speak’ and one second later the SGD produces the utterance ‘what does it look’ (line 25). By posing an unfinished question, Maria claims the interactional floor and displays an orientation towards stopping the progression of teacher talk. The contribution includes an interrogative adverb that signals that the contribution is a question although it lacks specification. When the unfinished question is produced, the teacher is writing on the white board with his back to the class (line 26). There is a 4 second silence during which the teacher continues to write and Maria adds ‘like’ and again activates ‘speak’. When the synthetic voice produces the complete sentence ‘what does it look like’ the teacher immediately responds by requesting clarification. He suggests ‘the semen applicator’, linking her question to the previous topic and invites Maria to specify her question. He turns to her and monitors the partner window (line 33, ). It takes Maria 12.2 seconds to write ‘syringe’, which is misspelt but comprehensible (line 34), and the teacher offers a candidate understanding ‘you’re interested in what the semen applicator looks like’. He acknowledges her request for information ‘yes of course we will find that out’ and pauses the lecture to initiate a search for an image of a semen applicator on the computer.

To conclude, the production of an unfinished contribution worked to claim the turn and create an interactional space for the student to produce a question before it became sequentially and topically unrelated.

3.1.3. Leaving to the teacher to integrate the question in the lesson

The analysis also revealed that students sometimes did not activate ‘speak’ after composing a question. This meant that some questions were only made available for the teacher who could read them on the partner window. Instead of activating the synthetic voice, the student waited for the teacher to incorporate the question in the lesson.

When Excerpt 3 starts, the teacher has asked the class if they know for how long women are pregnant. Vera (V) responds nine months and Maria (M) 40 weeks. In a third turn, the teacher problematises the answers and responds that nine months equals 37–38 weeks (not in excerpt). He invites them to reflect on this difference and states that the midwife should know (line 1).

Excerpt 3 If I am pregnant in May which month will I give birth this just was an example.

May 5th (01:02:43)

Vera starts composing her question (line 4) when the teacher initiates closure of the lesson. She continues to formulate her question in parallel with the teacher’s talk during 3 min and 38 seconds.

During the omitted interaction, Vera finishes her hypothetical question ‘If I am pregnant in May which month will I give birth this just was an example’. In Swedish, Vera has written ‘födda’ (i.e. born), which we, in this context, have interpreted as a miss spelling of ‘föda’ (i.e. give birth). The contribution has a recognisable interrogative syntax as it starts with the conditional ‘if’, and requests information. Vera does not activate ‘speak’.

The teacher continues his talk about midwives’ calculation of pregnancy. By saying ‘haven’t you done the mathematics’ (line 86) the teacher stages an imaginary conversation with a midwife. Indirect reported speech is often deployed as a climax of a telling (Holt and Clift Citation2006), and here takes the shape of an enactment. It displays the teacher’s somewhat ironic attitude and takes a critical stance towards the imagined midwives (‘one may think’). At this time, he stops in front of Vera, and gazes at the partner window (line 88). He acknowledges her question ‘yeah’ and reformulates it stressing ‘if’ rather than ‘you’ and substituting ‘when will I give birth’ with ‘when is the child due’. Thereby, he emphasises the factual rather than personal perspective of the question, which was also indicated in the student question’s final part ‘this just was an example’.

As shown, since the teacher could read the contributions in the partner window on the SGD, the students sometimes transferred responsibility to the teacher for embedding the question in the progression of the lesson. This interactional practice can be compared to typically speaking students’ practice of asking questions in the chat in digital teaching (Sørum, Raaen, and Gonzalez Citation2021). Both types of questions are produced in a written format in parallel with teacher talk and it is up to the teacher to decide when to respond. Similar to questions posed in a chat box, the analysis demonstrates how the questioner hands over to the teacher to incorporate the question sequentially and to make it topically relevant. The question is made available for the teacher to relate to regardless of its sequential placement.

3.2. Collaborative and scaffolded production of an SGD-mediated question

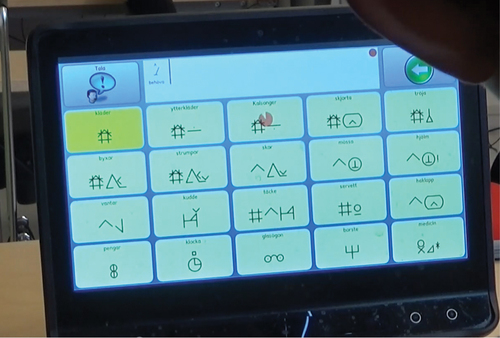

We will now analyse the trajectory of an unsolicited student contribution that initially took the shape of a semantic hint that did not contain a question word, and that in its sequential context posed problems of understanding for the assistant and teacher. As will be shown, the participants engage in considerable repair work and scaffolding, thereby working to collaboratively formulate a question. Nicholas is the student who makes the contribution. He is not literate and uses Blissymbolics. This means that there is a limited number of words for Nicholas to choose from and that he cannot easily include morphological units (e.g. tense, number). Nicholas personal assistant sits next to him, supervising the production on the screen ().

Figure 3. Blissymbols on the speech-generating device screen.

The interaction in Excerpt 4 follows upon Excerpt 2, in which Maria asked ‘What does it look like syringe’. When the Excerpt starts, the teacher is projecting a photo of a semen applicator on the Smartboard and describes how it is used (line 1).

Excerpt 4 Need underpants. How fish in needle.

May 5th (00:46:54 – 00:50:20)

Nicholas starts composing his contribution (line 2) simultaneous to the teacher’s explanation. The teacher is describing the semen applicator as someone enters the classroom. Eighteen lines are omitted during which a side-sequence develops in which the researcher (R) informs person (X) about the current study.

Nicholas observes the side-sequence that develops (lines 22–23) and waits until the researcher ends it by apologising to the teacher (line 24), before he activates the SGD (line 26). Due to the delay between activating a symbol and the speech output, the contribution ‘need underpants’ (line 28) is heard after the teacher’s response to the researcher. Nicholas selects the teacher as next speaker by gaze orientation (Rossano Citation2013) in synchrony with the synthetic voice output (line 28). Despite the unmistakable turn-allocation, the teacher does not respond and a 5 second gap of silence develops, indicating that the teacher and the assistant (A) treat Nicholas’ contribution as difficult to understand in relation to its sequential and topical context.

After the 5 seconds gap, the assistant produces an other-initiated other-repair, offering Nicholas a chance to explain himself ‘what do you mean now?’ (line 30). The final pitch rise downgrades the possible reproach and displays wondering (Couper-Kuhlen and Selting Citation2018). Nicholas does not respond but remains still, shifting his gaze back and forth between the SGD and the assistant. The assistant initiates an unfinished question suggesting an alternative understanding of what Nicholas might want to ask ‘do you mean under’ (line 32) and Nicholas orients to the SGD again.

During the omitted lines (34–79), Nicholas reformulates his contribution. He removes ‘need underpants’ and includes a question-word and a referent ‘How fish needle’ (line 80). The assistant requests further clarification with meta-comments ‘you’ve got to add something Nicholas’ and ‘it’s not really clear’ (lines 81, 83). Nicholas initiates repair in overlap with the assistant’s second meta-comment. He erases the symbol ‘needle’ and continues to formulate an alternative version of the question for 8.2 seconds. During this time, the classmates, teacher, and assistant wait in silence.

The assistant supervises Nicholas’ search for the symbol on the screen. When Nicholas adds the preposition ‘inside’ (line 85), the assistant asks a clarifying multi-unit question, which resembles a recast, a form of adult language scaffolding that has been shown to occur sequentially after a trouble source turn (Clarke, Soto, and Nelson Citation2017). It incorporates elements of the trouble source and provides an enhanced version of the turn. In this excerpt, the recast includes two questions in a row: the first incorporates elements of Nicholas’ turn (‘how fish’) with an expansion (‘sperm’) and the second is an understanding check ‘is that what you mean?’ (line 87). However, Nicholas does not activate speech but during 11 additional seconds continues to search for a symbol. Finally, the assistant utters ‘Ah’: as Nicholas has added ‘needle’ on the message row. The response is produced with prolonged duration and mid-level falling pitch, indicating a change-of-state (Heritage Citation1984a) in his understanding of what Nicholas is wondering about. At this time Nicholas activates ‘speak’ and the SGD produces ‘how fish in needle’. The assistant utters two reformulations of the question, the first replacing ‘fish’ with ‘sperms’ (‘how sperms get into the needle’) and the second replacing ‘needle’ with ‘semen applicator’ (‘how sperms get into the semen applicator’ (lines 93 and 95). After this long process, when the assistant and student have worked collaboratively to establish what the student is asking, it is the teacher who produces an affirmative yes/no question (Koshik Citation2002) ‘is that what you’re wondering’ that works as an understanding check. Nicholas’ confirmation (light smile and backwards push of his torso) is a positive response, a go-ahead marker.

In sum, the SGD-mediated unsolicited question in Excerpt 4 started with a semantic hint ‘need underpants’. Although the lexical meaning of the phrase appears as topically unrelated to the ongoing talk, it opened up a space for the construction of a question. The teacher paused the progression of the lesson and the assistant offered the student repeated opportunities to repair and reformulate his contribution. The prolonged and collaborative composition process ended with a topic relevant question seeking knowledge.

4. Discussion

This study has examined aided-speaking students’ unsolicited questions in teacher-fronted classroom talk. In previous research, aided-speaking students’ contributions in whole-class interactions have been shown to be rare and to mainly occur in response turns preceded by explicit turn allocation (Tegler et al. Citation2020). Somewhat nuancing these results, our study has identified one classroom in which aided-speaking students did produce unsolicited contributions. The students were shown to orient to a turn-taking organisation by attempting to produce their utterances in sequentially relevant places, that is, in proximity to a TRP, in order for their contributions to be heard as both sequentially and topically relevant. In line with previous research on SGD-mediated interaction (Auer and Hörmeyer Citation2017; Higginbotham, Fulcher, and Jennifer Citation2016; Savolainen et al. Citation2020), producing an SGD-mediated contribution was however time consuming which led to that student contributions often being heard in a sequentially misplaced position. Due to severely restricted embodied resources (i.e. absent, delayed, or distorted body movements) and no option to add prosodic elements to the utterances, the students moreover had to rely upon grammar and vocabulary to make their contributions recognisable as questions (cf. Hayano Citation2012). This study confirms that illiterate students with access to a limited set of symbols or vocabulary are faced with a huge challenge in using synonyms and associations creatively (cf. Light and McNaughton Citation2012).

The participants were found to address these challenges in various ways. Unlike typically speaking students, aided-speaking students are often faced with the choice between speed and accuracy (Auer and Hörmeyer Citation2017). In our data, the students for example produced unfinished contributions or semantic hints to claim the interactional floor, thereby prioritising speed. By activating the speech output before finalising the question, the students could provide a semantic hint or an unfinished contribution that the teacher and assistants could follow up on (cf. Auer and Hörmeyer Citation2017). These contributions worked to create a space for the formulation of a question, either individually (i.e. the student continued formulating the question to activate ‘speech’ again once it was completed) or collaboratively (i.e. the assistant, teacher and student collaboratively working to establish what the student was wondering about). Activating the speech output before finalising a question thus worked to hold the turn, a practice that did similar interactional work as pre-announcements such as ‘I have a question’ in typical classrooms (Duran and Sert Citation2021). Another method for posing unsolicited questions in ways that circumvent the limitations of the SGD-devices, was to use the design of the technology and the fact that the teacher was able to see the partner window of the device, in order to transfer responsibility for embedding the question in the lesson to the teacher. Rather than making the question publicly hearable through activating ‘speech’, the student would make the utterance visually available to the teacher, a method that also afforded the production of grammatically complete, that is, accurate in Auer and Hörmeyer’s (Citation2017) terms, contributions.

The analyses show that the aided-speaking students’ unsolicited contributions were however vulnerable to problems of understanding. The fact that the contributions could take the shape of unfinished phrases where the delay in production time caused them to be heard in a sequentially misplaced position, sometimes meant that extensive collaborative work was required in order to establish the meaning of a student utterance. This was accentuated when the student was illiterate and communicated using a restricted set of symbols. Similar to what Tegler et al. (Citation2020) found, the co-participants’ (assistants, teachers and classmates) collaborative and active work to prolong the interaction space, in this case for formulating a question and to engage in processes of repair and reformulations, was crucial in order for the aided-speaking students to be able to pose questions. The analysis of the whole data set revealed that only 5% (13 out of 245) of the SGD- or communication board mediated contributions, produced by 3 out of 23 students, were treated as unsolicited questions. None of them had an intellectual disability and two were literate. The low number of unsolicited questions might not be surprising given the considerable challenges producing an SGD-mediated question, the fact that aided-speaking illiterate students predominantly produce one or two-symbol contributions (Binger and Light Citation2008) and few study-included illiterate participants. The combination in our data of the aided-speaking students’ interactional and linguistic skills and the teacher’s and the assistant’s supportive practices, underline the students’ communicative and interactional competences (cf. Clarke and Ray Citation2013; Light and McNaughton Citation2013). The results mirror the study of Kääntä and Kasper (Citation2018) who found that a teacher in a regular classroom treated typically speaking students’ interruptions as contextually relevant and desirable actions even when they paused the progression of the lecture. In fact, key to the aided-speaking students’ ability to ask questions was that the teacher and the assistant oriented towards the students’ contributions as relevant and as questions.

Kardas Isler et al. (Citation2019) found that the teacher oriented to students’ topically relevant unsolicited contributions but disregarded questions out of topic. In so doing, the teacher created a classroom in which students could reflect, share thoughts, knowledge, and experiences on a teacher-chosen learning object. Similarly, our study shows that designated teacher work is required to address aided-speaking students’ unsolicited contributions as questions and to evaluate if they are topic relevant or something that can be responded to later on (rather than disregarding them). The pedagogical implication of the study thus concerns the significance of teachers’ active work to create a classroom culture with an interactional architecture that shows an expectation that aided-speaking students can produce unsolicited contributions and that these in turn may be questions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. According to Swedish law (SFS Citation2010, 800), special education schools should be avoided in favour of inclusive education in regular school. Schools are responsible for supervising that necessary adaptations and support are implemented to enable learning and participation for all students in the regular classroom. Special needs education schools with small classes should only be an alternative when these adaptations and support are insufficient.

2. Communication boards are paper-based devices unlike SGDs that are digital.

3. According to the Swedish Act concerning Support and Service for Persons with Certain Functional Impairment (LSS), individuals with severe and permanent disability are entitled support that meet their daily needs to guarantee good life quality (SFS Citation1993, 387).

References

- Andzik, N. R., Y.-C. Chung, and M. Kranak. 2016. “Communication Opportunities for Elementary School Students Who Use Augmentative and Alternative Communication.” Augmentative and Alternative Communication 32 (4): 272–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/07434618.2016.1241299.

- Auer, P., and I. Hörmeyer. 2017. “Achieving Intersubjectivity in Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC): Intercorporeal, Embodied, and Disembodied Practices.” In Incorporeality: Emerging Socialities in Interaction, edited by C. Meyer, J. Streeck, and S. Jordan, 323–360. New York: Oxford University Press.

- BCI. 2023. “Blissymbolics.org.” https://www.blissymbolics.org/.accessed2023.04.04.

- Binger, C., and J. Light. 2008. “The Morphology and Syntax of Individuals who use AAC: Research Review and Implications for Effective Practice.” Augmentative and Alternative Communication 24 (2): 123–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/07434610701830587.

- Bishop, D. 2020. Test for Reception of Grammar (TROG-2). Enschede, the Netherlands: Pearson.

- Bockgård, G. 2007. “Syntax och prosodi vid turbytesplatser. Till beskrivning av svenskans turtagning.” In Interaktion och kontext. Nio studier av svenska samtal, edited by E. Engdahl and A.-M. Londen, 139–183. Lund: Lunds studentlitteratur.

- Bourque, K., and H. Goldstein. 2020. “Expanding Communication Modalities and Functions for Preschoolers with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Secondary Analysis of a Peer Partner Speech-Generating Device Intervention.” Journal of Speech, Language, & Hearing Research 63 (1): 190–205. https://doi.org/10.1044/2019_JSLHR-19-00202.

- Chin, C., and J. Osborne. 2008. “Students’ Questions: A Potential Resource for Teaching and Learning Science.” Studies in Science Education 44 (1): 1–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057260701828101.

- Chung, Y.-C., E. Carter, and L. Sisco. 2012. “Social Interactions of Students with Disabilities Who Use Augmentative and Alternative Communication in Inclusive Classrooms.” American journal on intellectual and developmental disabilities 117 (5): 349–367. https://doi.org/10.1352/1944-7558-117.5.349.

- Church, A., and A. Bateman. 2019. “Children’s Right to Participate: How Can Teachers Extend Child-Initiated Learning Sequences?.” International Journal of Early Childhood 51 (3): 265–281. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-019-00250-7.

- Clarke, M., and W. Ray. 2013. “Communicative Competence in Children’s Peer Interaction.” In Aided Communication in Everyday Interaction, edited by N. Norén, C. Samuelsson, and C. Plejert, 23–57. Guildford: J & R Press Ltd.

- Clarke, M., G. Soto, and K. Nelson. 2017. “Language Learning, Recasts, and Interaction Involving AAC: Background and Potential for Intervention.” Augmentative and Alternative Communication 33 (1): 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/07434618.2016.1278130.

- Clarke, M., and R. Wilkinson. 2007. “Interaction Between Children with Cerebral Palsy and Their Peers 1: Organizing and Understanding VOCA Use.” Augmentative and Alternative Communication 23 (4): 336–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/07434610701390350.

- Clarke, M., and R. Wilkinson. 2008. “Interaction between Children with Cerebral Palsy and their Peers 2: Understanding Initiated VOCA Mediated Turns.” Augmentative and Alternative Communication 24 (1): 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/07434610701390400.

- Couper-Kuhlen, E., and M. Selting, eds. 2018. Interactional Linguistics: Studying Language in Social Interaction. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

- Dolce, F., and R. van Compernolle. 2020. “Topic Management and Student Initiation in an Advanced Chinese-as-a-Foreign-Language Classroom.” Classroom Discourse 11 (1): 80–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/19463014.2018.1563799.

- Duran, D., and O. Sert. 2021. “Student-Initiated Multi-Unit Questions in EMI Classrooms.” Linguistics & Education 65:100980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2021.100980.

- Ekström, A., O. Sandgren, B. Sahlén, and C. Samuelsson. 2023. “‘It Depends on Who I’m with’: How Young People with Developmental Language Disorder Describe their Experiences of Language and Communication in School.” International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12850.

- Garton, S. 2012. “Speaking Out of Turn? Taking the Initiative in Teacher-Fronted Classroom Interaction.” Classroom Discourse 3 (1): 29–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/19463014.2012.666022.

- Goffman, E. 1978. “Response Cries.” Language 54 (4): 787–815. https://doi.org/10.2307/413235.

- Harvey, S., E. A. Schegloff, and G. Jefferson. 1974. “A Simplest Systematics for the Organization of Turn-Taking for Conversation.” Language 50 (4): 696–735. https://doi.org/10.2307/412243.

- Hayano, K. 2012. “Question Design in Conversation.” In The Handbook of Conversation Analysis, edited by J. Sidnell and T. Stivers, 395–414. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- Heritage, J. 1984a. “A Change-of-State Token and Aspects of its Sequential Placement.” In Structures of Social Action: Studies in Conversation Analysis, edited by J. M. Atkinson and J. Heritage, 299–345. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Heritage, J. 1984b. Garfinkel and Ethnomethodology. Camebridge: Polity Press.

- Higginbotham, J., K. Fulcher, and S. Jennifer. 2016. “Time and Timing in Interactions Involving Individuals with Als, their Unimpaired Partners and their Speech Generating Devices.” In The Silent Partner?: Language, Interaction and Aided Communication, edited by M. Smith, 199–227. New Jersey, UK: J & R Press Limited.

- Holt, E., and R. Clift, eds. 2006. “Reporting Talk : Reported Speech in Interaction.” In Studies in Interactional Sociolinguistics. Vol. 24. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Jacknick, C. 2009. “A Conversation-Analytic Account of Student-initiated Participation in An Esl Classroom.” Education in Teachers College, PhD thesis, Columbia University.

- Jefferson, G. 2004. “Glossary of Transcript Symbols with an Introduction.” In Conversation Analysis: Studies from the First Generation, edited by G. H. Lerner, 13–31. Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins Publishing.

- Kääntä, L., and G. Kasper. 2018. “Clarification Requests as a Method of Pursuing Understanding in CLIL Physics Lectures.” Classroom Discourse 9 (3): 205–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/19463014.2018.1477608.

- Kardas Isler, N., B. Ufuk, and A. E. Sahin. 2019. “The Interactional Management of Learner Initiatives in Social Studies Classroom Discourse.” Learning, Culture & Social Interaction 23:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2019.100341.

- Koshik, I. 2002. “A Conversation Analytic Study of Yes/No Questions which Convey Reversed Polarity Assertions.” Journal of pragmatics 34 (12): 1851–1877. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-2166(02)00057-7.

- Light, J., and D. McNaughton. 2012. “Supporting the Communication, Language, and Literacy Development of Children with Complex Communication Needs: State of the Science and Future Research Priorities.” Assistive Technology 24:34–44. 10.1080/10400435.2011.648717.

- Light, J., and D. McNaughton. 2013. “Putting People First: Re-Thinking the Role of Technology in Augmentative and Alternative Communication Intervention.” Augmentative and Alternative Communication 29 (4): 299–309. https://doi.org/10.3109/07434618.2013.848935.

- Lindwall, O., and G. Lymer. 2014. “Inquiries of the Body: Novice Questions and the Instructable Observability of Endodontic Scenes.” Discourse Studies 16 (2): 271–294. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445613514672.

- Lorah, E. R., J. Miller, and B. Griffen. 2021. “The Acquisition of Peer Manding Using a Speech-Generating Device in Naturalistic Classroom Routines.” Journal of Developmental & Physical Disabilities 33 (4): 619–631. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-020-09762-w.

- Mehan, H. 1979. ”“What Time Is It, Denise?”: Asking Known Information Questions in Classroom Discourse.” Theory into practice 18 (4): 285–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405847909542846.

- Merke, S. 2018. “Challenging and Objecting: Functions of Third Position Turns in Student-Initiated Question Sequences.” Hacettepe University Journal of Education 33:298–315. https://doi.org/10.16986/HUJE.2018038808.

- Norbury, C. F., D. Gooch, C. Wray, G. Baird, T. Charman, E. Simonoff, G. Vamvakas, and A. Pickles. 2016. “The Impact of Nonverbal Ability on Prevalence and Clinical Presentation of Language Disorder: Evidence from a Population Study.” Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 57 (11): 1247–1257. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12573.

- Norén, N., E. Svensson, and J. Telford. 2013. “Participants ’Dynamic Orientation to Folder Navigation when Using a VOCA with a Touch Screen in Talk-in-Interaction.” Augmentative and Alternative Communication 29 (1): 20–36. https://doi.org/10.3109/07434618.2013.767555.

- Rossano, F. 2013. “Gaze in Conversation.” In The Handbook of Conversation Analysis, edited by J. Sidnell and T. Stivers, 308–329. Chichester, West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Savolainen, I., A. Klippi, T. Tykkyläinen, J. Higginbotham, and K. Launonen. 2020. “The Structure of Participants’ Turn-Transition Practices in Aided Conversations that Use Speechoutput Technologies.” Augmentative and Alternative Communication 36 (1): 17–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/07434618.2019.1698652.

- Schegloff, E. A. 2007. Sequence Organization in Interaction: A Primer in Conversation Analysis Volume 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sert, O. 2017. “Creating Opportunities for L2 Learning in a Prediction Activity.” System 70:14–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2017.08.008.

- SFS. 1993. Lag (1993:387) om stöd och service till vissa funktionshindrade Sveriges riksdag. https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-och-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/lag-1993387-om-stod-och-service-till-vissa_sfs-1993-387/.

- SFS. 2010. Skollag (2010:800). Sveriges riksdag. https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-och-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/skollag-2010800_sfs-2010-800/.

- Sidnell, J., and T. Stivers. 2014. The handbook of Conversation Analysis. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Solem, M. S. 2016a. “Negotiating Knowledge Claims: Students’ Assertions in Classroom Interactions.” Discourse Studies 18 (6): 737–757. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445616668072.

- Solem, M. S. 2016b. “Displaying Knowledge through Interrogatives in Student-Initiated Sequences.” Classroom Discourse 7 (1): 18–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/19463014.2015.1095105.

- Sørum, H., K. Raaen, and R. Gonzalez. 2021. Can Zoom Replace The Classroom? Perceptions on Digital Learning in Higher Education Within It. 20th European Conference on e-Learning, Berlin, Germany: University of Applied Sciences HTW.

- Stivers, T. 2010. “An Overview of the Question–Response System in American English Conversation.” Journal of pragmatics 42 (10): 2772–2781. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2010.04.011.

- Tegler, H., I. Demmelmaier, M. Blom Johansson, and N. Norén. 2020. “Creating a Response Space in Multiparty Classroom Settings for Students using Eye-gaze Accessed Speech-Generating Devices.” Augmentative and Alternative Communication 36 (4): 203–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/07434618.2020.1811758.

- Thiemann-Bourque, K. S., S. McGuff, and H. Goldstein. 2019. “Training Peer Partners to Use a Speech-Generating Device With Classmates With Autism Spectrum Disorder: Exploring Communication Outcomes Across Preschool Contexts (vol 60, pg 2648, 2017).” Journal of Speech, Language, & Hearing Research 62 (4): 1015–1015. https://doi.org/10.1044/2018_JSLHR-L-18-0464.

- van Balen, M. N. G. Johanna, S. de Vries, and T. Koole. 2022. “Taking Learner Initiatives within Classroom Discussions with Room for Subjectification.” Classroom Discourse, 1–20. ahead-of-print (ahead-of-print). https://doi.org/10.1080/19463014.2022.2128689.

- Walker, V. L., and Y.-C. Chung. 2022. “Augmentative and Alternative Communication in an Elementary School Setting: A Case Study.” Language, Speech & Hearing Services in Schools 53 (1): 167–180. https://doi.org/10.1044/2021_LSHSS-21-00052.

- Waring, H. Z. 2011. “Learner Initiatives and Learning Opportunities in the Language Classroom.” Classroom Discourse 2 (2): 201–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/19463014.2011.614053.

Appendix A

Transcription conventions according to Jefferson (Citation2004).