ABSTRACT

Although several studies underline the importance of a successful opening of a school lesson to spur students’ interest and facilitate learning, we have limited knowledge about how openings are enacted in classrooms. This study contributes to the sparse research by asking: What characterizes the openings of 58 reading lessons in Norwegian language arts 8th grade classrooms? A key finding is that in most openings, the teachers make academic cognitive moves which help create an academic frame around students’ learning. This mostly entails consolidation moves, where the lesson content is connected to prior knowledge, while explicit learning goals and agendas are provided to a limited degree. Second, few openings contain academic affective moves, where teachers use appetizers to facilitate engagement for the topic. Third, the teachers often engage in formal general pedagogical moves relevant for classroom management and organizational and emotional support. We discuss these findings and their implications for researchers and practitioners.

Introduction

“The beginning is the most important part of the Work,” Plato wrote (The Lancet Microbe, Citation2020). The beginning is also considered an important text section in narrative, dramaturgical, and rhetorical traditions, where it is often referred to as exposition, prologue, exordium, or introduction (Engelstad, Citation2007; Svensen, Citation1985; Torvik, Citation1973). Across the different traditions, the main functions of the opening are to spur interest and prepare the spectator, listener, or reader for what is to come. In a dramaturgical context, the purpose of the opening is to “hook” the viewer (Østern, Citation2014, p. 40), and in a rhetorical context, Gjerde (Citation2016, p. 42) noted that although a successful introduction does not guarantee a successful speech, poor quality introductions are almost always followed by poor quality speeches. Openings in general seem to have a great impact on the spectator, listener, or reader. Thus, the first part of a school lesson can play a vital role for students to engage in the learning activities that follow.

In a school context, Aung and Tepsuriwong (Citation2017) have defined the opening as “the first structure of the lesson” (p. 252). Although a number of studies underline the importance of a successful lesson opening, we have limited knowledge about how openings are enacted in classrooms. However, leaning on Wagenschein, Graf (Citation2013, pp. 60–61) has pointed to “the right beginning” as a strongly underestimated issue in didactics, and Slot (Citation2020) has described the opening as a “critical place” (p. 81) in the dramaturgy of the lesson, but also an “overlooked” (p. 80) phenomenon.

Lesson openings are highlighted as important for several reasons. First, openings are considered valuable for creating engagement. Aung and Tepsuriwong (Citation2017) claimed that this seems “to be the moment that the teacher can decide whether the learners would be engaged in the lesson or not” (p. 252), and Velandia (Citation2008) concluded that engaging warm-up activities increased learners’ attention. Renninger and Hidi (Citation2019) underlined interest as an important component for learning, but there is a need for more knowledge about how teachers facilitate this in lesson openings. In addition, some studies have highlighted the openings’ potential for establishing a safe classroom climate. Hattie (Citation2023) claimed that: “The highest classroom effects relate to classroom cohesion, management, teacher-student relations, friendship, and a sense of belonging” (p. 182). In this regard, Slot (Citation2020) stated that the opening “sets a frame, a tone, and an expectation that are carried into the rest of the instruction” (p. 79, out translation). However, we need more knowledge of how teachers facilitate this in the start of the lesson. Also, several studies have pointed to the opening as an important moment to guide the lesson into an academic track. Markussen and Seland (Citation2013) described the first few minutes after a clear, formal opening as “golden” (p. 45), as such starts often generate student attention which many teachers use to introduce the lessons topics and activities. As a part of this, Hattie (Citation2023) has also emphasized “goal-directedness” (p.202) as an important key factor for learning. Introducing learning goals in the lesson opening, can give students a clear idea of what they are expected to learn and why (Seidel et al., Citation2005; Slot, Citation2020). Guiding the students into an academic track, may also involve activation of students’ prior knowledge on a topic or summarizing what they have learned in previous lessons (Klette, Citation2023; Tierney & Cunningham, Citation1984). Statement of goals and review of previous learning are also highlighted as important steps in explicit instruction (Rosenshine, Citation1986, p. 1). In sum, lesson openings are not only about starting class. Leaning on Perrott (Citation1982), McGrath et al. (Citation1992) states that openings concern “the procedures teachers use to get learners into a state of readiness for learning” (p. 95), and further, it can be a strategic tool that can impact students’ engagement and understanding throughout the lesson.

In this study, we are interested in how teachers open lessons where reading is at the center of instruction. A key factor in all schooling endeavors is equipping students with adequate reading competence to navigate a complex textual landscape (Weyergang & Magnusson, Citation2020). Previous research has identified a strong connection between reading skills and motivation (Anmarkrud & Brandmo, Citation2021; Guthrie et al., Citation2013), while noting that students’ motivation for reading often declines across grade levels (Parsons et al., Citation2018). Moreover, studies have shown that Norwegian adolescents are generally less engaged in reading now than before (Jensen et al., Citation2019; Roe, Citation2020). Lesson openings can therefore be especially important in reading lessons to establish a motivating learning environment and facilitate the lesson’s reading activities.

Despite the importance we attribute to lesson openings as critical stepping stones for further student engagement and learning, we know, as already stated, little about how teachers facilitate lesson openings. In areas where little research has been done, there is often a need for descriptive investigations. Descriptive studies can provide valuable insight that functions as a springboard for further causal investigations (Larsen, Citation2017, p. 22). The aim of this study is thus to contribute to the knowledge base by examining openings of reading lessons in a Norwegian lower-secondary school context by asking: What characterizes openings of reading lessons in Norwegian language arts 8th grade classrooms? When using the term lesson opening, we restrict our analyses to the first 10 minutes of the lesson, starting when the teacher addresses the whole class for the first time.

Research on lesson openings

In this section, we report on findings in previous studies of lesson openings and other relevant classroom research, with a particular focus on language arts (L1), Language 2 (L2), and Language 3 (L3) instruction. The aim is to present relevant key findings rather than to complete a systematic review (Grant & Booth, Citation2009, pp. 94–95). First, we report on studies that have explicitly positioned themselves as studies of lesson openings. Second, we examine dramaturgical studies relevant when discussing aspects of lesson openings. Third, we review key findings in studies of instructional quality and student engagement in general.

Lesson openings

A limited number of studies have examined lesson openings from a L1, L2 and L3 perspective. However, a particularly central small-scale study was conducted by McGrath et al. (Citation1992) in the United Kingdom (UK). Through video observation, surveys, and teacher and student interviews, McGrath et al. investigated how 10 foreign language teachers began their lessons, as well as the adult students’ attitudes to these openings. In this regard, they suggested an analytical framework highlighting five main functions of lesson openings: (1) an affective function related to the teacher’s establishment of an appropriate social classroom climate and stimulation of students’ interest, (2) a cognitive function to stimulate cognitive awareness and help the students to relate to previous knowledge, (3) an encouraging functionFootnote1 to facilitate student responsibility and independence, (4) a pragmatic functionFootnote2 to fulfill a required institutional role achieved by giving relevant information and checking on previous learning, and (5) a pragmatic functionFootnote3 to overcome difficulties, such as handling students who arrive late (McGrath et al., Citation1992, p. 102). One main finding was that the teachers seemed to place more emphasis on affective than cognitive aspects, although the authors identified differences in the teachers’ individual opening repertoires. Another finding was that the students were satisfied with how the openings were carried out.

Several other studies on lesson openings have referenced the framework of McGrath et al. (Citation1992). For example, Aung and Tepsuriwong (Citation2017) built on this frameworkFootnote4 in their interview and video study of the lesson openings of five English language teachers teaching undergraduate students in Thailand. They found that affective and cognitive perspectives were particularly emphasized in addition to the teachers’ fulfillment of the institutional role.

In the Scandinavian context, Slot (Citation2020) analyzed the openings of 89 lessons in different subjects with students aged 14–18. She considered the opening a “frame” and found that teachers often clarified some central cognitive terms in the openings. However, she determined that other factors, such as learning goals, differentiation, and evaluation moves, did not seem to be much in focus. Graf (Citation2021) has also studied Danish teachers’ framing of students’ learning processes across different subjects in elementary classrooms. He found that teachers spent about 11% of the lessons on openings (initial framing). The teachers stated learning goals in 23% of the openings, addressed academic content in 67%, and framed student activities in 80%.

In addition, a few international small-scale studies have explored “warming up activities,” “ice-breakers,” and “instant activities.” Drawing on research from physical education, Rauchenbach and Vanoer (Citation1998) argued to start lessons immediately with “instant activities” that quickly engage the students, particularly younger students, as opposed to traditional warm-up routines, where the teacher makes “jogs around the learning area” (p. 7) and spends time on organization. Velandia (Citation2008) conducted an action research study of “warming up activities” in 7th-grade English teaching at a Colombian school. The purpose was to compose openings consisting of activities that instantly caught the students’ attention. Based on surveys, field notes, and students’ diary notes, he found that well-planned, well-instructed, and engaging warm-up activities increased students’ attention and engagement. Similarly, Akther (Citation2014) emphasized the effectiveness of warm-up activities in the opening in language teaching at the university level. On the basis of a rather large-scale survey study involving 247 students and 10 teachers at five universities in Bangladesh, Akther claimed that warm-up activities can help establish a friendly classroom climate, create interest and focus, increase student participation, and elicit background knowledge.

Few studies have focused on lesson openings in Norwegian classrooms. However, Markussen and Seland (Citation2013) investigated lesson openings in four junior high schools, based on interviews with the principals and observations of 40 lessons across subjects in 10 classrooms. One main finding was that the principals stressed the importance of clarifying learning goals in openings, yet observations revealed that teachers rarely presented clear goals (p. 47). Moreover, teachers usually provided agendas, but the agendas were often vaguely communicated like “Today we will practice for the test” (p. 45). Yet another finding revealed that the teachers, to a small degree, facilitated cognitive aspects in the openings, like connecting the topic to previous knowledge. Another prevalent finding was that the teachers often opened the lessons with explicit greeting rituals and gained control of the class rather quickly. In a broader Nordic context, Saloviita (Citation2016) made a similar conclusion in his study of classroom management in Finnish schools. By analyzing 130 lessons across different subjects, he concluded that openings were “generally orderly” and that teachers used effective tools to manage events (p. 60).

Dramaturgical perspectives

Allern (Citation2010) and Østern (Citation2014) argued that dramaturgical thinking is relevant for teaching. In a Norwegian context, Bakke and Lindstøl (Citation2021) have developed a method for conducting dramaturgical analysis of lesson structures in three different phases: beginning, middle, and end. Leaning on Østern (Citation2014), they describe beginnings as:

An opening is likely to have a presentation and / or a prelude. The presentation will often consist of answers to didactical ‘what’, ‘how’ and ‘why’ questions, while a prelude creates an atmosphere. The prelude will give the pupils a taste of what they are going to experience (Bakke & Lindstøl, Citation2021, p. 290).

Research on instructional quality

Classroom research on instruction and management processes has also contributed important knowledge relevant to lesson openings. Klette (Citation2017) summarized the key trends and findings in classroom research. First, studies have emphasized the importance of the balance and variation of teaching situations. Drawing on Meichenbaum and Biemiller (Citation1998) and Meyer and Alexander (Citation2011), Klette distinguished between (1) settings where the students observe or listen to the teachers’ explanations and demonstrations, (2) settings where the students engage in activities while the teacher guides their work, and (3) settings of self-reflection where the teacher facilitates meta-perspectives on learning (p. 180–181). Findings from Norwegian classrooms have shown that teachers have primarily used settings where students are engaged in listening to the teacher or working on different tasks, while they have spent little time on activating students’ meta-reflection (Klette et al., Citation2017). Klette (Citation2017) asserted that no preferred methods or settings exist; rather, the most important factor is variation.

Second, classroom research has pointed to the importance of the teacher’s support functions (Klette, Citation2017). In this regard, researchers have highlighted organizational and educational support connected to clear learning goals and relevant cognitive challenges as being important. How learning goals are articulated in classrooms, may impact students’ learning processes and motivation (Boden et al., Citation2019; Seidel et al., Citation2005). According to Aung and Tepsuriwong (Citation2017), Lindsay (Citation2006) suggested that in addition to goals and linking to previous knowledge, the opening should also contain information about student activities. In addition, Klette (Citation2017) underlined the importance of emotional perspectives connected to the social classroom climate. Hence, researchers have highlighted affective “appetizers” (p. 186) as an effective tool to create engagement and activate prior knowledge. Ødegaard and Arnesen (Citation2010) defined an “appetizer” as when “the teacher makes a demonstration, shows artefacts or uses a story, joke, story or something like that, to motivate interest in a topic” (p. 23, our translation). We have limited knowledge about appetizers in Norwegian classrooms, but Ødegaard and Arnesen found that appetizers were rarely used in science teaching, although their use generated positive student engagement (p. 26).

Summary of the significance of lesson openings

Lesson opening is not a clear-cut term and could include different cognitive, affective, institutional, structural, and pedagogical aspects. Openings also seem to play a pivotal role in student learning for several reasons. First, it is about “setting the stage” in a way that can provide context for what the students will be learning, for example preparing them for new material by activating students’ prior knowledge (e.g. Aung & Tepsuriwong, Citation2017; Tierney & Cunningham, Citation1984). Second, openings can contribute to establish relevance. Effective lesson openings can relate the lesson’s topic to students’ everyday lives, helping them see the importance and applicability of what they are learning (Bransford et al., Citation2000). In addition, openings can spark student engagement (e.g. Rauchenbach & Vanoer, Citation1998; Velandia, Citation2008). If students’ interest is stimulated from the start, they are more likely to be motivated for learning. Openings can also involve clarifying learning objectives for the students (e.g. Klette, Citation2017). Introducing learning goals can give students a clear idea of what they are expected to learn and why it is relevant, which also involve a student motivation perspective. And last, openings can build a safe environment (e.g. Slot, Citation2020). Starting a lesson with a positive tone, can create a positive environment, which may encourage students to participate in the lesson activities.

Study design

Data material

We retrieved the data material for this study from a large-scale video study; Linking Instruction and Achievement (The LISA-project) (Klette et al., Citation2017). The study is approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data, and the data in our study is treated according to the ethical guidelines. During one school year (2014–2015), the project collected video data from 46 Norwegian language arts classrooms across different parts of Norway, with a total of 178 videotaped lessons. The schools were sampled to include a geographic and demographic distribution; hence, the sample should reflect a broad range of Norwegian classrooms. For the aim of the present study, we identified lessons that centered on reading instruction, which constituted 58 lessons from 34 classrooms and teachers. The recordings allowed us to conduct systematic and detailed analyses of classroom instruction (cf. Blikstad-Balas, Citation2017). The lessons were not designed with a particular focus on openings or reading instruction, and our findings may thus reflect key trends in how Norwegian language teachers in lower-secondary school begin reading lessons.

Operationalization of lesson openings

We operationalized lesson opening as the first 10 minutes, starting when the teacher addresses the whole class for the first time (Aung & Tepsuriwong, Citation2017; McGrath et al., Citation1992; Mesiti et al., Citation2006). Typically, the starting point is verbal communication with greetings such as “good morning,” but it may also take other communicative forms, such as a music performance.

McGrath et al. (Citation1992) noted that the concept of lesson opening is difficult to operationalize, but they suggested a main distinction between pragmatical and temporal definitions. Within dramaturgical studies, the opening is usually pragmatically defined based on the content characteristics of the lesson’s first phase (Allern, Citation2010; Bakke & Lindstøl, Citation2021; Østern, Citation2014). However, it might be difficult to decide when the beginning ends and when the middle phase begins. Thus, most studies on lesson openings have defined the opening sequence temporally. For example, Mesiti et al. (Citation2006) operationalized the opening sequence as the first 10 minutes, and Aung and Tepsuriwong (Citation2017) included the first 15 minutes.

We have chosen a temporal definition for two main reasons. First, we consider a temporal definition to be easier to operationalize as it involves a low inference decision. Second, even though a temporal definition in itself may undermine the importance of compositional or functional aspects, we assume that most teachers will have finished the beginning phase after 10 minutes, including creating an atmosphere and introducing the what, how, and why of the lesson (Bakke & Lindstøl, Citation2021, p. 290). A typical Norwegian school lesson lasts 45–60 minutes, thus, the first 10 minutes will cover at least 16% to 22% of the lesson.

Analytical framework

We developed our framework for analyzing how teachers in Norwegian language arts enact lesson openings in several steps by combining theory-driven and inductive approaches (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005). We have built on previously developed frameworks presented in the review section, in particular McGrath et al. (Citation1992) and Aung and Tepsuriwong (Citation2017). However, we developed these frameworks further in line with our in-depth analyses of lesson openings, as some of the categories related to cognitive, affective, institutional, structural, and pedagogical aspects were challenging to separate and to operationalize on our data. In addition, we wanted to reduce the number of main categories to focus on different types of academic moves relevant for the lessons topics. Three main categories were generated: (1) academic cognitive moves, (2) academic affective moves, and (3) general pedagogical moves (see ).

Table 1. Analytical framework.

Academic cognitive moves and academic affective moves, both include moves connected to the subject content of the lesson. Academic cognitive moves include four subcategories: learning goal, agenda, consolidation, and introduction of new content. Such cognitive framing has been underlined as important for learning (see the review section). The first two subcategories are related to the extent to which the teacher provides clear learning goals and an agenda for the lesson. Consolidation covers moves that contextualize learning, such as relating the subject content of the lesson to previous academic knowledge or relating relevant terms, content, or concepts to students’ everyday lives, personal, and/or cultural experiences for academic purposes. The introduction of new content points to new academic content in the lesson opening, for example, when the teacher moves to assumed unknown topics by lecturing or facilitating tasks on new academic knowledge. From a dramaturgical perspective, this move implies that the teacher is shifting from the beginning phase to the middle phase before the first 10 minutes have passed.

The second main category, academic affective moves, includes moves the teacher makes to create motivation and curiosity for the subject content, such as engaging in warm-up activities or appetizers relevant to the academic topic, to create engagement for the subject content.

Third, general pedagogical moves include moves that are not explicitly related to the subject content, but involve general moves that are highlighted as important for learning (see the review section). We further divided this category into three subcategories: administrative tasks, relationship-building moves, and general affective moves. Administrative tasks involve actions like general welcome rituals, registration of students’ attendance, and general information not connected to the specific lesson. Such moves are highlighted as important to classroom management, and also, it is relevant to examine how much focus is spent on such non-academic moves. Relationship-building moves involve sharing personal information connected to students’ well-being, for example, general talk about the weekend, while general affective moves, includes general moves to create a good atmosphere that are not relevant to the subject content (e.g., playing calming music when the students enter the classroom). Such moves are also underlined as an important prerequisite for learning (see the review section).

All the categories are prototypical, meaning that some moves may have different functions at the same time. For example, a general pedagogical move like wishing the students good morning, is categorized as an administrative task because the main function is to mark the start of the lesson. However, greeting also have a relationship-building aspect, and may therefore partially be overlapping with relationship-building moves.

In the analysis process, author 1 and author 2 tested the framework in several steps. We began by coding and discussing three video-recorded lesson openings. Then, we separately analyzed 29 lesson openings. To strengthen the reliability, we double-coded 10% of the lesson openings. The double coding showed a high degree of agreement, and in the rare cases of disagreement, we discussed the opening sequences until we reached agreement.

Results

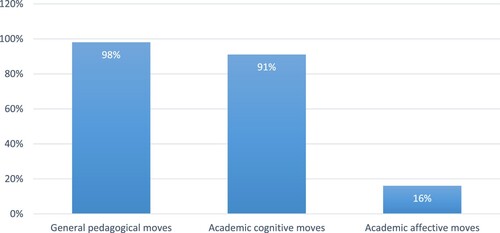

Based on our analyses of lesson openings in 58 videorecorded lessons, a main finding is that teachers engaged in academic cognitive moves in 91% of the lessons, academic affective moves in 16% of the lessons, and general pedagogical moves in 98% of the lessons (see ).

Category 1: academic cognitive moves

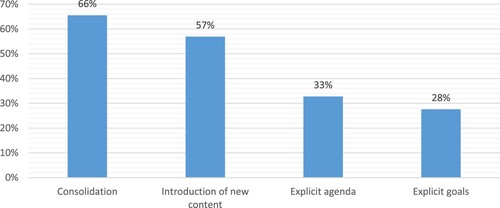

Cognitive framing is highlighted as important for learning (see the review section). In 91% of the lessons, the teachers employed some kinds of academic cognitive moves in the opening, such as consolidating academic content (66%), introducing new academic content (57%), providing an explicit agenda (33%), and/or explicit learning goals (28%) ().

Explicit agenda and learning goals

Both goal-directedness (Hattie, Citation2023) and information about the lessons activities (Lindsay, Citation2006) are underlined as important for learning. However, in only 19 lesson openings (33%), the teachers provided an explicit agenda and directly addressed the lesson activities connected to the development of reading skills or understanding of literature, as in the following example:

Today, we will work on Chapter 2.4 called “After Reading: Edit.” Then, we will repeat important concepts that we have worked with, and then we will play the word game Alias. Then, we will read from [the novel] Barsakh.

In 16 lessons (28%), the teachers provided explicit learning goals that clearly articulated a reading-related purpose and related to the particular lesson and/or the learning period. For example, in one of the lessons, the teacher explicitly stated:

When the lesson is over, you should understand why it is smart to use pre-reading activities, such as the purpose of reading, get an overview of the reading material, and find out whether you already know something about it.

Consolidation of academic content

In 66% of the lessons, the teachers initiated academic consolidation as an opening move. In these cases, the teachers typically connected new material to the students’ previous academic knowledge by referring to an earlier lesson or learning period and eliciting the students’ prior knowledge on this topic. In one lesson, the teacher started by asking the students, “What topic did we start on yesterday?” The students then provided some answers involving fiction and stories, and the teacher followed up by saying, “Yes, what is fiction? What is a story? Explain it to each other.” In other lessons, the consolidation move entailed eliciting students’ prior knowledge on a topic that was relevant for the text they were about to read, in which the connections made between prior knowledge and the text were explicitly tied to the new material (Grossman, Citation2015). For example, in a lesson in which the class was reviewing reading strategies, the teacher tasked students with a prereading activity about what they knew about a topic before reading a nonfictional text on this topic (for a more thorough explanation of this example, see Magnusson et al., Citation2019). The consolidation moves in these openings thus involved situations where a topic or new information was introduced, which provided an opportunity for students to prepare for, query, and clarify academic-related questions.

In a few of the openings involving consolidation (7 out of 38), the consolidation involved relating to students’ personal and/or cultural experiences outside of school. These linkages potentially engage students in relating to textual content and pique their interest in a text. For example, in one lesson, the class was preparing to read a short story involving a frightening stay at a bed and breakfast; The landlady by Roald Dahl. The teacher asked the students questions like: “How many have stayed at hotels before?” and “How many have stayed in a place where you have to pay, but which is not a hotel where there is a reception and you are waited on?” The students then shared their experiences of staying in different, also in places that felt a bit scary. The teacher linked these thoughts to the text: “And that is exactly what Roald Dahl explores in this short story we are going to read.” This example suggests that the students were provided with an opportunity to reflect on and connect their own out-of-school experiences to new learning material, in which the connections made were seemingly specific enough to enable a deeper understanding of the text.

Introduction to new content

In 57% of the lessons, the teachers moved on to introduce new academic content before the opening sequence was over. This finding may be related to the fact that we have operationalized the opening to the first 10 minutes. From a dramaturgical perspective, the lesson proceeded from the beginning phase to a main activity in the middle phase. However, moving on to new content may also indicate that the teachers spend less time on reviewing previous learning.

In our study, the introduction of new content in the opening, typically included providing new information about an author, genre, or content elements of a particular text prior to reading. For example, in one of the openings, the teacher introduced disciplinary content about what characterizes poems as a genre and briefly explained the composition and course of action in the poem “Terje Vigen” by Henrik Ibsen. The class read the poem later in that particular lesson. In another example, the teacher handed out a copy of a new story in the lesson opening, and explained that the modes of narration that were used, had been written in the margins. The teacher then asked the students to work together in pairs and to highlight examples of the different ways of telling stories.

Category 2: academic affective moves

Previous research has underlined stimulation of students’ interest and a safe classroom climate as important for learning (Akther, Citation2014; Hattie, Citation2023). However, the main category of opening moves that we observed least frequently, was academic affective moves that may appeal to students’ engagement related to the academic content. We observed this move in only 9 out of 58 lesson openings (16%). However, when the teachers used this move, it exhibited creativity and seemed to spur engagement and/or curiosity. For example, as a thematic connection to the content of a short story that a class was about to read, the teacher introduced a handwritten letter with red kiss marks that she allegedly had received:

The short story we are going to read will be handed out to you, but first I thought I would show you something. I have received a letter. Did you see that I fussed with the letter when you came in? I think I have to open it. [The teacher looks excited and opens the letter.] Oh, it’s a nice letter! Look here! What kind of letter is this? Is there anyone who can imagine what the content of this letter might be?

aves

Waves [in the handwriting]—But that’s not the content; that’s the writing. What is written here? (…) Hm? Perhaps none of you have received such a letter?

Maybe a love letter

You think it’s a love letter? What kind of hint can we see here that makes us think this is a love letter?

Kiss marks

I agree. And the reason why I am teasing you with this is that the short story we are going to read is called “Red Kiss Marks in a Letter.”

In another lesson, the teacher used a famous Norwegian rap song as an introduction to learning about poetry. This could be a way of getting the students’ attention by relying on their acquaintance with and emotions toward this music genre and connecting it to the academic content in focus. We also see examples of more playful activities, such as solving a word bingo with Neo-Norwegian words as an entrance to reading a text in the Neo-Norwegian language.

In other lessons, some teachers also shared their own emotional experiences related to the texts they were about to read. For instance, in the abovementioned lesson, where a class was going to read the creepy short story by Roald Dahl, the teacher also shared his own experience about how scary it was for him to read texts by this author as a child. These examples show that teachers enacted the academic affective opening moves in quite different ways, pointing to a creative aspect of teaching.

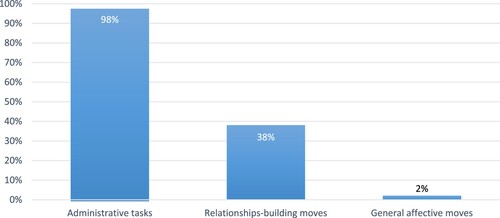

Category 3: general pedagogical moves

Previous research has underlined classroom management and organizational and emotional support as important for learning, even if this is not directly related to the academic topic of the lesson (see the review section). Our analyses showed that the teachers often make general pedagogical moves related to practical issues, relations and students’ well-being in the opening sequences; teachers engaged in administrative tasks in 98% of the openings, relationship-building moves in 38%, while general affective moves were rare (2%) ().

Administrative tasks

Administrative tasks involve general actions important to classroom management and non-academic information. The teachers made such moves in almost all the openings; clearly greeting the students (98% of the lessons), taking attendance (26%), and conveying practical messages (50%). The practical communication entailed either very short messages to students, such as fetching their textbooks or starting their laptops, or instructions that took up more time and focus. For example, in one lesson, the teacher went through the schedule for the entire day and provided information about an upcoming day when the students were going to collect money for a charity organization. Thus, in medias res openings, where the teachers surprisingly jumped into the middle of an academic narrative without any initial general pedagogical moves, were not common.

Relationship-building moves

We also relatively frequently (41%) observed general relationship-building moves, in which the teachers showed emotional support and concern for the students’ well-being. For example, the teachers asked general questions to the class about whether they were doing well, provided feedback to the class on non-curricular events or actions, or showed sympathy for how hard the students were working. More specifically, one teacher expressed concern for the students by asking if they were tired after the previous day, when they walked over a mile on a school trip. Several lesson openings also included the teacher leading the class in singing birthday songs for students. Such emotional support is highlighted as important for learning (Klette, Citation2017).

General affective moves

In only one lesson, we observed a non-academic affective move through which the teacher facilitated a good and safe learning environment. In this lesson, the teacher played calming music from the speakers while the students entered the classroom. The music seemed to have the function of creating a calming atmosphere rather than constituting a learning goal in itself or being relevant to the academic topic.

Discussion

In the following sections, we will discuss the key findings and highlight implications for researchers and practitioners, as well as creating a springboard for further casual investigations between lesson openings and students learning.

An important finding, is that in most lessons, the teachers made academic cognitive moves in the opening sequence. The most common move was consolidation, in which the teachers made short or more detailed references to prior knowledge or everyday experiences to frame the lesson’s academic content. First, connecting the topic to experiences outside of school might be important in making the topic or text relevant to the students. Many studies have reported a gap between students’ learning inside and outside of school, and explicit connections between everyday life and academic knowledge may help students to bridge this gap (Gee, Citation2007; Silseth et al., Citation2017; Teo, Citation2008). Second, previous research has underlined the importance of connecting new and previous academic knowledge in learning processes. Both types of consolidation (i.e., connection to prior knowledge and connection to students’ everyday experiences) are also relevant for reading strategies and reading comprehension (Brevik, Citation2019; Magnusson et al., Citation2019). In line with our findings, some previous studies have found that teachers seem to be aware of consolidation moves in lesson openings, for example Aung and Tepsuriwong (Citation2017) concluded that “most of the teachers focused on establishing the appropriate cognitive framework in the opening stage” (p. 259). However, they defined a “cognitive framework” broadly as providing an organizing framework and stimulating awareness of needs in addition to eliciting relevant linguistic knowledge and relevant experience (p. 259). However, in a Norwegian context, Markussen and Seland (Citation2013) have found rather few examples of teachers making connections to prior knowledge in lesson openings; specifically, they said, “We did not hear that content that students had been engaged with in earlier lessons was made relevant to today’s lesson” (p. 46, our translation). One explanation for this could be that teachers have become more aware of the importance of activating students’ prior knowledge. This is also highlighted as a central reading strategy in the research field (Roe & Blikstad-Balas, Citation2022).

However, other academic cognitive moves, such as providing explicit learning goals and agendas, were rather vague or missing in many of the openings. More precisely, the teachers provided explicit agendas in 33% of the openings and explicitly communicated learning goals in 28% of the opening sequences. The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training (Citation2022) stated that involving students in the development of learning goals is important so they can be aware of what and how to learn. Despite a classroom study conducted by Hodgson et al. (Citation2012, p. 81, 186) pointed to a growing awareness among teachers of goal-oriented instruction, several Nordic studies have found that teachers provide clear learning goals to a limited degree (Graf, Citation2021; Markussen & Seland, Citation2013; Slot, Citation2020; Svanbjornsdottir et al., Citation2022). Thus, we believe there is greater potential for communicating agendas and learning goals as part of the openings’ cognitive framing. However, we also believe that a repetitive practice of providing learning goals in the same way at the same time in every lesson opening, may not be effective, but rather procedural. Learning goals and agendas are needed to create a supportive cognitive frame around the topic or lesson, but goals and agendas may be provided in many forms and may not be necessary in every single lesson opening. They may also be stated after an engaging in medias res-opening.

Another main finding is that affective moves did not constitute a frequent practice among the teachers. Previous studies have underscored the importance of affective elements in opening sequences to stimulate students’ interest and engagement (Akther, Citation2014; Aung & Tepsuriwong, Citation2017; McGrath et al., Citation1992; Rauchenbach & Vanoer, Citation1998; Velandia, Citation2008). In our study, we found just one example of a general affective move, where the teacher played calm music in the opening with no particular relevance to the academic topic. However, we found a few more examples of academic affective moves which prepared the reading of short stories, for example by introducing a love letter or telling stories about stays at hotels and bed and breakfasts as pre-reading activities. There may be several reasons why teachers rarely make academic affective moves. One reason may be that such affective activities require creative planning, and some teachers may not have a large repertoire of appetizing activities on which to build on in their instructional design. Moreover, teachers may perceive creative planning to be time-consuming, and viewing creative activities in the classroom as one more responsibility adding to their workload (Rinkevich, Citation2011). We believe there is potential for making more affective academic moves to capture the students’ attention and stimulate interest, and as Klette (Citation2017) points to, in general there is a need for variation in lessons. This affective aspect is particularly important in relation to reading, as recent PISA reports have shown that lower-secondary students’ interest in reading is decreasing across Nordic countries (Jensen et al., Citation2019; Roe, Citation2020). In addition, affective moves may also be relevant to the classroom climate, especially for ice-breaking and breaking of the “sound barrier” (Hoel, Citation1999, p. 40). Further, we believe that if teachers spend time on affective moves in the opening sequence, the focus should primarily be on appetizers that explicitly prepare the academic content of the lesson.

Another main finding, is that almost all the teachers used some general pedagogical moves in the lesson openings before moving to the academic content. More specifically, greeting rituals (administrative task) served as the first common act in many openings. Markussen and Seland (Citation2013) claimed that some sort of action from the teacher is required to mark the beginning of the lesson, and they found that greetings functioned as a clear starting point which often generated some “golden” focused minutes with student attention (p. 40). We found that greetings in many cases were followed by other general pedagogical moves, such as taking attendance and/or giving general information. Many teachers also spent time on general relationship-building moves in the openings, like questions about students’ well-being and happenings inside and outside of school. Care dimensions and safe relations between teachers and students may affect students’ academic interests and results (Hattie, Citation2023; Maursethagen & Kostøl, Citation2010). Although these general, traditional start-up moves contributed to an orderly start of the lesson (Markussen & Seland, Citation2013; Saloviita, Citation2016), we underline the potential for more variation. Despite formal and ritual opening moves may help students prepare for the rest of the lesson, this does not have to be the first part of the opening sequence in all lessons. We follow Rauchenbach and Vanoer (Citation1998, p. 7) and Velandia (Citation2008, p. 9), who claim that “traditional” opening routines may sometimes be varied and replaced by “instant” and surprising warm-up activities, to increase students’ attention and engagement.

Conclusion

The function of lesson openings is to spur interest and prepare students for learning. An opening may include a range of different cognitive, affective, and general pedagogical moves. We find that general pedagogical moves are common as a clear and friendly starting point, often followed by cognitive consolidation moves, while affective moves were less frequent. We acknowledge the potential for strengthening cognitive academic moves by providing clearer goals and agendas, and to include more affective academic moves in the openings to spur interest in the academic content. In general, we see the potential to vary the combination of moves in the lesson openings.

Limitations and research needs

The present study draws on data from a representative sample of classrooms (Klette et al., Citation2017; Klette et al., Citation2021), where we have systematically analyzed 58 lessons with regards to their opening sequences. In our approach to analyze key features of the openings, we have focused on general patterns across classrooms and teachers, summarizing our findings on an aggregated level. There were variations between the lessons and teachers, thus for a next phase of analyses, we will identify typologies among the teachers and see how they might vary over time and across lessons. At this point, we found it, however, useful to a map an aggregated pattern of variations of typical opening sessions.

A second limitation is linked to the problem of quantity versus quality when analyzing features in classroom teaching and learning (Lahn & Klette, Citation2022). In this study, we applied the three broad categories (academic cognitive moves, academic affective moves and general pedagogical moves) to look for patterns and frequencies in lesson openings. Although the presence and frequency of an activity is important, the duration and the quality of the different activities might be just as critical. The reported frequency of consolidation moves, for example, convey both short and rather superficial summaries as well as in depth discussion and elaborations when summarizing students’ prior knowledge. Thus, presence and frequency might be a first step when trying to understand qualities of classroom openings, duration and depth are equally important. As such, further analyses are required.

How lesson openings affect students’ learning is yet an area that calls for further investigations. Studies from lower secondary mathematics and science classrooms suggest a close relationship between lessons goals and student learning (Seidel et al., Citation2005; Selling Alexander et al., Citation2023). However, what this looks like in language and language learning is yet not well documented, and further analysis is required.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Our label.

2 Our label.

3 Our label.

4 Cf. framework on p. 254–255.

References

- Akther, A. (2014). Role of warm-up activity in language classroom: A tertiary scenario. Thesis. BRAC University. https://api.core.ac.uk/oai/oai:localhost:10361/3553

- Allern, T. H. (2010). Dramaturgy in teaching and learning. In M. Björkgren, B. Snickars-von Wright, & A. L. Østern (Eds.), Drama in three movements: A Ulyssean encounter (pp. 95–111). Åbo Akademi University.

- Anmarkrud, Ø, & Brandmo, C. (2021). Engasjerende leseundervisning [Engaging reading instruction]. In V. Grøver & I. Bråten (Eds.), Leseforståelse i skolen. Utfordringer og muligheter [Reading Comprehension in School. Challenges and Opportunities] (pp. 227–240). Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

- Aung, K. S. M., & Tepsuriwong, S. (2017). Lesson openings: How teachers begin lessons in an English class. Online Proceedings of the International Conference: DRAL 3/19th ESEA 2017. Lesson Openings: How Teachers Begin Lessons in an English Class (kmutt.ac.th).

- Bakke, J. O., & Lindstøl, F. (2021). Chasing fleeing animals – on the dramaturgical method and the dramaturgical analysis of teaching. Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance, 26(2), 283–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569783.2021.1885370

- Blikstad-Balas, M. (2017). Key challenges of using video when investigating social practices in education: Contextualization, magnification, and representation. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 40(5), 511–523. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743727X.2016.1181162

- Boden, K. K., Zepeda, C. D., & Nokes-Malach, T. J. (2019). Achievement goals and conceptual learning: An examination of teacher talk. Journal of Educational Psychology, 112(6), 1221–1242. https://doi-org.ezproxy.uio.no/10.1037/edu0000421

- Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L., & Cocking, R. R. (Eds.). (2000). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school. National Academy Press.

- Brevik, L. M. (2019). Explicit reading strategy instruction or daily use of strategies? Studying the teaching of reading comprehension through naturalistic classroom observation in English L2. Reading and Writing, 32, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-019-09951-w

- Engelstad, A. (2007). Fra bok til film: om adaptasjon av litterære tekster [From book to movie: On the Adaption of literary texts]. Cappelen Akademisk Forlag.

- Gee, J. P. (2007). Situated language and learning: A critique of traditional schooling. Routhledge.

- Gjerde, O. A. (2016). Taler og retorikk - håndbok i taleskriving [Speeches and Rhetoric – Handbook in Speech writing]. Gyldendal Akademisk.

- Graf, S. T. (2013). Det eksemplariske princip i didaktikken. En historisk-systematisk undersøgelse af Martin Wagenscheins, Wolfgang Klafkis, Oskar Negts, lærekunstdidaktikkens og Günther Bucks konceptioner af eksemplarisk belæring og læring [The exemplary principle in didactics. A historical systematic study of Martin Wagenscheins, Wolfgang Klafkis, Oskar Negts, didactics of teaching and Günter Bucks conceptions of exemplary teaching and learning]. Thesis. Institut for Kulturvidenskaber, Syddansk Universitet.

- Graf, S. T. (2021). Et komparativt blik på de frie grundskolers undervisning [A comparative look at instruction in primary schools]. In S. T. Graf & S. S. Mikkelsen (Eds.), Digital projektdidaktik [Digital project didactics]. Århus Universitetsforlag.

- Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91–108. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

- Grossman, P. (2015). Protocol for Language Arts Teaching Observations (PLATO 5.0). Stanford University.

- Guthrie, J. T., Klauda, S. L., & Ho, A. N. (2013). Modeling the relationships among reading instruction, motivation, engagement, and achievement for adolescents. Reading Research Quarterly, 48(1), 9–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.035

- Hattie, J. (2023). Visible learning: The sequel. A synthesis of over 2,100 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Routledge.

- Hodgson, J., Rønning, W., & Tomlinson, P. (2012). Sammenhengen Mellom Undervisning og Læring. En studie av læreres praksis og deres tenkning under Kunnskapsløftet [The connection between teaching and learning. A study of teachers’ practice and their thinking during Kunnskapsløftet]. Nordlandsforskning. https://kudos.dfo.no/documents /11981/files/12106.pdf

- Hoel, T. L. (1999). “Den første gang, den første gang … ”. Bygging av munnleg klasseromskultur i norskfaget [The first time,, the first time … building an oral classroom culture in Norwegian language arts]. In F. Hertzberg & A. Roe (Eds.), Muntlig norsk [Orality in Norwegian Language arts] (pp. 37–53). Tano Aschehoug.

- Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

- Jensen, F., Pettersen, A., Frønes, T. S., Kjærnsli, M., Rohatgi, A., Eriksen, A., & Narvhus, E. K. (2019). PISA 2018 - Norske elevers kompetanse i lesing, matematikk og naturfag [PISA 2018 – Norwegian students’ competence in reading, mathematics and science]. https://www.udir.no/contentassets/2a429fb8627c4615883bf9d884ebf16d/kortrapport-pisa-2018.pdf

- Klette, K. (2017). Hva vet vi om god undervisning? Rapport fra klasseromsforskningen. [What do we know about good instruction? Report from classroom research]. In I. R. J. Krumsvik & R. Säljö (Eds.), Praktisk pedagogisk utdanning. En antologi [Practic pedagogical education. An anthology] (3rd ed., pp. 173–201). Fagbokforlaget.

- Klette, K. (2023). Classroom observation as a means of understanding teaching quality: Towards a shared language of teaching. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 55(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2023.2172360

- Klette, K., Blikstad-Balas, M., & Roe, A. (2017). Linking instruction and student achievement. A research design for a new generation of classroom studies. Acta Didactica Norge, 11(3), 10. https://doi.org/10.5617/adno.4729

- Klette, K., Roe, A., & Blikstad-Balas, K. (2021). Observational scores as predictors for student achievement gains. In M. Blikstad-Balas, K. Klette, & M. Tengberg (Eds.), Analysing teaching quality: Perspectives, principles and pitfalls (pp. 173–203). Scandinavian Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.18261/9788215045054-2021-06

- Lahn, L. C., & Klette, K. (2022). Reactivity beyond contamination? An integrative literature review of video studies in educational research. International Journal of Research and Methods in Education, 46(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743727X.2022.2094356

- The Lancet Microbe. (2020). The beginning is the most important part of the work. Lancet Microbe, 1, e308. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2666-5247(20)30204-4

- Larsen, A. K. (2017). En enklere metode. Veiledning i samfunnsvitenskapelig forskningsmetode [A simpler method. Guidance in social science research method]. Fagbokforlaget.

- Lindsay, C. (2006). Learning and teaching English: A course for teachers. Oxford University Press.

- Lindstøl, F. (2017). Fra tekst til episode – en dramaturgisk analyse av lærerens undervisning [From text to episode a dramaturgical analysis of the teacher’s instruction]. In K. Kverndokken, N. Askeland, & H. Siljan (Eds.), Kvalitet og kreativitet i klasserommet – ulike perspektiver på undervisning [Quality and Creativity in the Classroom – Different Perspectives on Instruction] (pp. 145–170). Fagbokforlaget.

- Magnusson, C. G., Roe, A., & Blikstad-Balas, M. (2019). To what extent and how are reading comprehension strategies part of language arts instruction? A study of lower secondary classrooms. Reading Research Quarterly, 54(2), 187–212. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.231

- Markussen, E., & Seland, I. (2013). Den gode timen. En kvalitativ studie av undervisning og læringsarbeid på fire ungdomsskoler i Oslo [The good lesson. A qualitative study of instruction and learning at four secondary schools in Oslo]. Rapport. Utdanningsdirektoratet, NIFU. http://hdl.handle.net/11250/280395

- Maursethagen, S., & Kostøl, A. (2010). Det relasjonelle aspektet ved lærerrollen [The relational aspect of the teacher role]. Norsk pedagogisk tidsskrift, 94(3), 231–243. https://www.idunn.no/npt/2010/03/art02

- McGrath, I., Davies, S., & Mulphin, H. (1992). Lesson beginnings. Edinburgh Working Papers in Applied Linguistics, 3, 90–108. http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED353842.pdf

- Meichenbaum, D., & Biemiller, A. (1998). Nurturing independent learners: Helping students take charge of their learning. Brookline Books.

- Mesiti, C., & Clarke, D. (2006). Beginning the lesson: The first ten minutes. In D. Clarke, et al. (Ed.), Making connections (pp. 47–71). Brill.

- Meyer, R. E., & Alexander, P. A. (2011). Handbook of research on learning and instruction (2nd ed.). Routhledge.

- Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. (2022). Involver elever og lærlinger i vurderingsarbeidet [Involving students and apprentices in assessments] https://www.udir.no/laring-og-trivsel/vurdering/underveisvurdering/involvering/

- Ødegaard, M., & Arnesen, N. (2010). Hva skjer i naturfagklasserommet? – Resultater fra en videobasert klasseromsstudie; PISA+ [What happends in the science classroom? Results from a videobased classroom study PISA +). Nordic Studies in Science Education, 6(1), 16–32. https://doi.org/10.5617/nordina.271

- Østern, A. L. (2014). Dramaturgi i didaktisk kontekst [Dramaturgy in a didactic context]. Fagbokforlaget.

- Parsons, A. W., Parsons, S. A., Malloy, J. A., Gambrell, L. B., Marinak, B. A., Reutzel, D. R., Applegate, M. D., Applegate, A. J., & Fawson, P. C. (2018). Upper elementary students’ motivation to read fiction and nonfiction. The Elementary School Journal, 18(3), 505–523. https://doi.org/10.1086/696022

- Perrott, E. (1982). Effective teaching. Longman.

- Rauchenbach, J., & Vanoer, S. (1998). Instant activities: Active learning tasks that start a lesson out right. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 69(2), 7–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.1998.10605059

- Renninger, K. A., & Hidi, S. E. (2019). Interest development and learning. In K. A. Renninger & S. E. Hidi (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of motivation and learning (pp. 265–290). Cambridge University Press.

- Rinkevich, J. L. (2011). Creative teaching: Why it matters and where to begin. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 84(5), 291–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/00098655.2011.575416

- Roe, A. (2020). Elevenes lesevaner og holdninger til lesing [Students’ reading habits and attitudes towards readning]. In T. S. Frønes & F. Jensen (Eds.), Like muligheter til god leseforståelse? 20 år med lesing i PISA [Equal opportunities for good reading comprehension? 20 years of reading in PISA]. Universitetsforlaget.

- Roe, A., & Blikstad-Balas, M. (2022). Lesedidaktikk - etter den første leseopplæringen [Didactics of reading – after the first reading training]. Universitetsforlaget.

- Rosenshine, B. V. (1986). Synthesis of research on explicit teaching. Educational Leadership, 43, 60–69.

- Saloviita, T. (2016). What happens at the lesson start? International Journal of Pedagogies and Learning, 11(1), 60–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/22040552.2016.1187651

- Seidel, T., Rimmele, R., & Prenzel, M. (2005). Clarity and coherence of lesson goals as a scaffold for student learning. Learning and Instruction, 15(6), 539–556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2005.08.004

- Selling Alexander, J. V., Klette, K., & Nortvedt, G. A. (2023). Teacher enactment of goals in Nordic mathematics classrooms. Manuscript submitted for publication.

- Silseth, K., Wiig, C., & Erstad, O. (2017). Elevers hverdagserfaringer og kunnskaper som ressurser for læring [Students’ everyday experiences and knowledge as resourses for learning]. In O. Erstad & I. Smette (Eds.), Ungdomsskole og ungdomsliv. Læring i skole, hjem og fritid [Secondary school and youth life. Learning in school, at home and in spare time] (pp. 37–54). Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

- Slot, M. F. (2020). Ved undervisningens begyndelse [At the beginning of instruction]. In S. T. Graf & U. H. Jensen (Eds.), Efterskolens praksis under lup - undersøgelser af dannende undervisning og samvær [Post-school practice under the microscope – studies of formative teaching and socializing] (pp. 79–104). Klim.

- Svanbjornsdottir, B., Zophoníasdottir, S., & Gísladottir, B. (2022). Quality of the stated purpose and the use of feedback in Icelandic lower-secondary classrooms results from a video study. Teachers and Teaching, 121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2022.103946

- Svensen, Å. (1985). Tekstens mønstre: innføring i litterær analyse [The pattern of the text: introcuction to literary analysis]. Universitetsforlaget.

- Teo, P. (2008). Outside-in/inside-out: Bridging the gap in literacy education in Singapore classrooms. Language and Education, 22(6), 411–431. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500780802152721

- Tierney, R. J., & Cunningham, J. W. (1984). Teaching reading comprehension. In P. D. Pearson (Ed.), Handbook of research in reading. Longman.

- Torvik, A. (1973). Innføring i litterær analyse [Introduction to Literary analysis] (2nd ed.). Universitetsforlaget.

- Velandia, R. (2008). The role of warming up activities in adolescent students’ involvement during the English class. Profile Journal, 10, 9–26. http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/1692/169214143002.pdf

- Weyergang, C., & Magnusson, C. G. (2020). Hva er relevant lesekompetanse i dagens samfunn, og hvordan måles lesing i PISA 2018? [What is relevant reading competence in today’s society, and how is reading measured in PISA 2018?]. In T. S. Frønes & F. Jensen (Eds.), Like muligheter til god leseforståelse? Lesing i PISA i et 20-års perspektiv [Equal opportunities for reading comprehension? Reading in PISA in a 20-year perspective]. Universitetsforlaget.