ABSTRACT

The neoliberal turn has driven attempts to marketize education, but how does marketization occur? In this article I draw on ethnographic and linguistic-ethnographic methods to investigate marketization through a microanalytic lens. My investigation focuses on a team of educational professionals, who participated in a workshop led by an organizational consultant named Eric. During the workshop, Eric successfully encouraged the educators to adopt some key business terms that he imported from the high-tech sector. My findings indicate that the marketization of education was not straightforward. Rather, the process encountered some resistance and sowed confusion before a business discourse ultimately took hold. The process of marketization became entangled with the power dynamics shaped by group members’ positioning vis-à-vis one another; and furthermore, it required the group to negotiate the meaning of some key terms. Marketization was ultimately mediated by a cognitive device called the Business Model Canvas and it relied on some pre-existing neoliberal tendencies among the workshop’s participants.

Neoliberal theory posits that human prosperity is best achieved through free and competitive markets. Efforts to translate this theory into policy have led governments across the globe to reduce their direct involvement in sectors that were traditionally government-run, including education systems (Harvey, Citation2005). The emergence of neoliberal policies can usually be linked to parallel processes, whereby neoliberal discourses also take hold. Thus, as educational institutions are privatized and redesigned to compete with one another, so too do educational scholars, practitioners, and other stakeholders develop new ways of talking about education, which are inspired by the business world. Building on the existing literature, I refer to this process as the marketization of education (e.g. Fairclough, Citation1993).

In Israel, where I conducted this study, the marketization of education has been underway for decades. Prior research has revealed various ways in which Israel’s education system has been marketized. These include a shift in the locus of educational knowledge, from academe to business and strategic philanthropy (Resnik, Citation2011); and also, a deep fascination with the high-tech sector, which enjoys a unique status in Israel – a country that is known as the ‘startup nation’ (Ramiel, Citation2019; Citation2021; Senor & Singer, Citation2009). Empirical research on the rise of neoliberalism – in Israel and elsewhere – has scrutinized government policy, institutional change, and popular discourse. Yet to date, there have not been any microanalytic investigations chronicling the moment-to-moment dynamics that unfold amid the marketization of education.

In this article, I provide a microanalytic account of one case in which educational discourse in Israel was marketized. I draw on linguistic-ethnography (Rampton, Maybin, & Roberts, Citation2015) and on more traditional ethnographic methods (Agar, Citation1986; Blommaert & Jie, Citation2020) to investigate a series of interactions between a team of educational professionals and an organizational consultant named Eric (I use pseudonyms throughout), who encouraged the team to talk about education in business terms. Eric was ultimately successful in his attempt to marketize the team’s educational discourse. But as my analysis shows, the process of marketization was less than straightforward. In some cases, it raised opposition from team members; and in other cases, it sowed confusion. My primary aim is to describe how the process of marketization occurred, including the obstacles it faced and the conditions whereby a business discourse ultimately took hold.

Background

Big-D Discourses

Big-D Discourses are ‘ways of combining and integrating language, actions, interactions, ways of thinking [etc.] … to enact a particular sort of socially recognizable identity’ (Gee, Citation2011, p. 201).Footnote1 Scholars, lovers, and recovering alcoholics all use language and other means of interaction in ways that position them as recognizable types of people and that reflect the rights and duties associated with the identity they are inhabiting at any given moment of interaction (Harré, Citation2012). Big-D Discourses are co-constructed by individuals and communities over time, as they negotiate what it means to be a certain type of person, and how that type of person is expected to interact with others. For instance, individuals draw on the resources that are available to them through their social identities and discursive repertoires to reimagine and recreate what it means to belong to a certain professional community. Sometimes, when an individual belongs to multiple communities, she can broker key elements of a Big-D Discourse across cultural boundaries, so that they come to ‘infect’ another Big-D Discourse (Gee, Citation2011, p. 38).

The education system can be construed in various ways, depending on which Discourses come into play when it is enacted in any particular setting. In recent decades, the neoliberal turn has led to a process of marketization, whereby education has increasingly been construed in terms drawn from business Discourses, and thus ‘infected’ by them. In the next section, I explain what is meant by the term marketization of education, and I discuss the central role that Discourses can play in the process of construing education as a competitive market.

Marketizing education

The neoliberalization and marketization of education

Neoliberal theory posits that ‘human well-being can best be advanced by liberating individual entrepreneurial freedoms and skills within an institutional framework characterized by strong private property rights, free markets, and free trade’ (Harvey, Citation2005, p. 2). Translating neoliberal theory into government policy typically means deregulation, privatization, and a withdrawal of the state from areas that were previously state-run. Inasmuch as the state does have a role, it is to establish and maintain free markets, and to support the institutions required to operate them. Neoliberalism thus involves marketization processes, in which ‘needs formerly met by public agencies … or through personal relationships in communities and families, are now met by companies selling services’ (Connell, Citation2013, p. 100).

The effects of neoliberalism over the past half-century have reverberated throughout society and reshaped many institutions, including education systems. For instance, Connell (Citation2013) argued that the adoption of neoliberal policies in Australia in the 1980s was followed by a cascade of reforms, which included redefining education as an industry. This led to policies that limited access to educational resources and simultaneously forced educational institutions ‘to conduct themselves like profit seeking firms’ (p. 102) to create a market where none previously existed. Educational institutions came to be viewed as service providers that were expected to compete with one another, while the idea of education itself was redefined as ‘human capital formation’ (p. 104).

Existing scholarship has implicated policy and discourse as two devices by which marketization is accomplished (Ball, Citation1993; Citation2007). Overt and explicit policy agendas are driven by value systems that are legitimated through public and professional discourse, amid processes that are usually implicit (Harvey, Citation2005). For example, Ball (Citation2007, p. 1) argued that adoption of a neoliberal Discourse is ‘fundamental to the production of an obviousness, a common sense … an inevitability of reform’ (p. 1). This suggests that the use of terms drawn from a business Discourse in reference to education can shape interlocutors’ assumptions about what constitutes legitimate educational goals and desired outcomes. Indeed, Fairclough (Citation1993). showed how the process of marketization can occur as a neoliberal Discourse colonizes new realms. For instance, he drew on the neoliberal notion of a consumer culture (also tied to a promotional culture) to show how discourse is used to ‘sell’ goods, services, ideas, or people that were not previously viewed as consumer products. In the next section, I review some of the ways in which education is being marketized in Israel, where I conducted this study, by means of Big-D Discourses that are imported from the business world.

Marketizing education through Discourse in Israel

As part of the marketization of Israel’s education system by discursive means, Resnik (Citation2011). traced the emergence of a new managerial Discourse that has shaped government policy since the turn of the century. Her analysis showed that the locus of knowledge production in the context of Israel’s educational policy partially shifted from academe to business and strategic philanthropy, thus validating an entirely new type of knowledge: ‘the managerial practical knowledge – meaning the practical knowledge top managers developed in their professional lives’ (p. 255, italics in the original). Resnik (Citation2011) also showed how several key educational constructs, including evaluation and measurement, achievement on standardized international tests, and empowerment of principals,Footnote2 which have deeply impacted Israel’s education Discourse, and by extension also its policies, were imported from the worlds of business and strategic philanthropy.

Due to the prominence of the high-tech industry within the Israeli economy, and Israel’s renown as the ‘startup nation’ (Senor & Singer, Citation2009), marketization of Israel’s education has been especially influenced by the high-tech sector. Ramiel’s (Citation2019; Citation2021) ethnographic work demonstrated how some Israeli actors are intent on reforming the education system by drawing on orders of discourse and discursive practices that originated in the startup companies typically associated with the high-tech industry (see also Tamir & Davidson, Citation2020). For instance, Ramiel (Citation2019) showed how redefining learners as users, a term that is unique to human–computer interaction and positions people in relation to technology, can have far-reaching consequences when it is applied to education: ‘The user language of technology universalizes the teacher, student and schools, … tends towards “global uniformity” or a “one size fits all” approach [and] unifies all students under an uncritical technological solutionism (p. 11)’. Similarly, Ramiel (Citation2021) also showed how silicone-valley culture, mediated by the notion of disruption and its corresponding disruptive logic, has led to a new form of policy intervention in Israel’s education system. The theory of ‘disruptive innovation’, which holds that businesses succeed either by designing cheaper products that give customers only what they need or products that give customers what they don’t yet know they need, became ‘a moral tale of salvation by the market’ (Ramiel, Citation2021, p. 24) within the high tech industry (one of the high-tech industry’s premier conferences is simply called ‘Disrupt’). In a compelling case study, Ramiel (Citation2021) described an edtech incubator that was established by the Center for Educational Technology, Israel’s largest NGO. One of the primary purposes of the incubator was to intentionally marketize Israel’s education system by discursive means: to blur ‘the boundaries between education and techno-business, public and private, through the creation of techno-social visions and storytelling’ (p. 10) that embody the neoliberal values underlying the high-tech market, with a particular emphasis on the notion of disruption.

In what follows, I offer a microanalytic account of another attempt in Israel to introduce a business Discourse imported from high-tech as part of an effort to marketize education. Specifically, in this case study I ask how the business Discourse came into play in an educational setting, how the realm of education was construed in response to it, what challenges faced those engaged in marketization, and how, ultimately, the business Discourse took hold.

Methods

Context

The data for this article were collected from an ethnographic study that I conducted at the INBAR Institute, a ‘national intercollegiate center for the research and development of curricula and programs in teacher education’ (INBAR website), in the 2021–2022 academic year. INBAR employs educational researchers and practitioners alongside other professionals with little or no experience in education. Its units are loosely organized into three groups with partially overlapping missions: academic research, professional development, and R&D. For example, INBAR publishes an academic journal and holds an annual academic conference, runs professional development courses for teachers, and operates a teacher training program for people who wish to change careers and become teachers. In addition to self-run activities, INBAR also partners with all of Israel’s teacher training colleges and with the Ministry of Education on various projects.

At the time of my investigation, the Institute’s leadership was dissatisfied with intra-organizational coordination and knowledge sharing between INBAR’s various educational programs. To address this organizational challenge, INBAR established a team comprising nine professionals representing six different divisions at the institute, who met bi-weekly to explore a theme that occupied most of the divisions at INBAR: teacher inquiry. Previous and subsequent iterations of the intraorganizational team were dedicated to other themes, such as online learning, social emotional learning, etc. In addition to 18 shared bi-weekly meetings that ran between November 2021 and June 2022, the team also met for a series of three two-day seminars, in November, February, and June, which marked the beginning, middle, and end of their yearlong collaboration. These seminars were led by Eric, an experienced organizational consultant who used to work as a software developer. In the sessions he led at the seminars, Eric imported discursive tools and terms from high-tech that were business-oriented to improve the group’s work and outcomes. These sessions offered me a unique glimpse into an attempt to intentionally marketize education by discursive means, in real time.

Analysis

To analyze the data, I drew on ethnographic methods (Agar, Citation1986; Blommaert & Jie, Citation2020), and particularly on linguistic ethnography, which combines the rigor of linguistics with the situatedness of ethnography (Rampton et al., Citation2015). Data analysis involved a review of my entire corpus of field notes; several iterative rounds of coding, which I discussed multiple times with Itai, Liat, and Dan, three INBAR employees who co-managed the teacher inquiry team; selection of a sequence of interactions that was theoretically telling (Mitchell, Citation1984); and finally, detailed transcription and discourse analysis to investigate the emergence of interactive meaning in the sequential unfolding of the interactions.

My turn-by-turn analysis of the sequences applied Gee’s (Citation2014). approach to discourse analysis, and particularly the view that in addition to conveying ideas, language also functions as means of engaging in socially recognizable activities and identifying as certain types of people. Hence, I asked about each turn at talk: (1) What ideas did interlocutors convey? (2) What socially recognizable activities did they engage in, or encourage others to engage in? And (3) what socially recognizable identities did they assume? Furthermore, I asked (4) How was the realm of education being construed? And (5) what Discourses were drawn upon to construe education in such a way? Answering these questions involved selecting the appropriate ‘tools’ from Gee’s (Citation2014) discourse analysis ‘toolbox’. For example, focusing on how interlocutors use language and other means to connect between people, ideas, or phenomena (the connection building tool); or on the situated meanings that interlocutors attributed to certain words and phrases that were specific to their local context (the situated meaning tool).

Data sources

As participant-observer, I attended all team meetings, which ran from 9 am to 4 pm, documenting them through video recordings and field notes, and conducted 16 semi-structured interviews with the team members. My analysis centers on a sequence of three interactions that was purposefully selected because it was especially telling vis-à-vis the process of marketization (Mitchell, Citation1984). My interpretations were informed by a broader ethnographic analysis grounded in my experiences as participant-observer. This broader ethnographic view was crucial to the microanalytic analysis because it provided the frames of meaning that bounded my analytic work (Giddens, Citation1993).

The case study

Setting the stage

In the next section, I analyze a sequence of three interactions that occurred during the teacher inquiry team’s second two-day seminar in February 2022. The sequence portrays a shift in the team’s discourse, which constituted a real-life case of marketization through discourse, the process that this article is intended to illuminate. To help capture the group dynamics and discursive moves that lie at the heart of the linguistic ethnographic analysis (in the next section), I begin with a more general ethnographic account, which provides some important prior knowledge.

The INBAR Institute

The INBAR Institute is uniquely positioned in-between the public and private sectors. On the one hand, it is publicly funded by Israel’s Ministry of Education, and most of the organizations that it collaborates with, including universities, colleges, and schools, are public. But on the other hand, INBAR’s staff are not employed directly by the government, which lightens the bureaucracy related to employment and also translates into less benefits and reduced job security. One result is that the work ethic, ethos, and language at INBAR are atypical of most government-run educational institutions in Israel. INBAR is a relatively competitive and agile workplace, where employees strive to prove themselves, managers encourage creativity and innovation, and outputs are regularly and transparently measured at the individual and program levels. This unique position between the public and private sectors proved an important mediating factor in the process of marketization described in this article.

The teacher inquiry team

Itai held a Ph.D. in business management, and in addition to his work at INBAR, he also taught part time at a large Israeli university. As the person responsible for all intra-organizational networking at INBAR, he held a senior role and reported directly to INBAR’s director. In the 2021–2022 academic year, Itai established the teacher inquiry team and viewed it as his most significant project at the time. He had worked hard to secure funding for the team, after previous efforts to improve communications between representatives of the institute’s various divisions had fared badly. Itai told me several times that participation in the previous teams he had established was not well funded, meaning that employees were expected to participate on their own time. This lowered their motivation to join and meant that their managers were not enthusiastic about their taking on a new project. But this time, the institute’s management had agreed for each participant in the teacher inquiry team to dedicate 10% of their working hours to the team (an entire workday every other week), and Itai saw this as a massive investment of resources and as vote of confidence in the project.

The notion of teacher inquiry itself was relatively insignificant to Itai, given that his primary concern was to establish a forum for INBAR employees to forge new and/or deeper relationships and improve intra-organizational ties. In an interview, Itai told me that because his expertise was in business management, he wasn’t well-versed enough in contemporary scholarship on teaching and learning to determine what the team’s focus should be. From his perspective, the team could just as well focus on online learning or socioemotional learning.

Liat and Dan co-managed the teacher inquiry team with Itai and worked together in a division at INBAR that supported teacher communities (Liat was Dan’s manager). Unlike Itai, they both held Ph.Ds in education and specialized in teaching and learning. Dan and Liat were familiar with the academic literature surrounding teacher inquiry, which they viewed as fundamental to their work with teacher communities. Their participation in the team was motivated primarily by their interest in teacher inquiry, and for them the question of intra-organizational communication was secondary.

Shortly after I began attending the meetings at INBAR, I learned that the entire teacher inquiry team was split between a group of five highly educated academics, who all held PhDs, four of whom were quite senior, and four less educated employees, whose roles at INBAR were administrative (e.g. marketing, project management). Furthermore, I learned that this split was typical of the organizational hierarchy at INBAR, where academics and non-academics were unofficially positioned quite differently. Academics with PhDs were considered more senior, had more job stability, and were highly regarded. In contrast, other employees typically held more junior roles, were let go more readily, and their status was generally lower. Anat and Amir, two non-academic members of the teacher inquiry team, sometimes referred to ‘the doctors’ in a playful-cum-derogatory way.

The seminars

Itai, Liat, and Dan, who all managed the team together (note: the non-academics were not represented in this group), agreed that the teacher inquiry team had to produce something tangible to show for its work, which would advance at least one of INBAR’s primary aims: academic research, professional development, or educational R&D. To help guide this process, they recruited Eric, an experienced organizational consultant, to lead three two-day seminars at the beginning, middle, and end of the academic year, respectively. Based on previous collaborations, Itai was very confident in Eric’s ability to attain this goal – in one of their planning meetings, Itai told Liat and Dan that Eric had successfully led other groups Itai had organized, and that he was confident in Eric’s ability to lead the seminars.

Before turning to consultancy, Eric worked at several hi-tech firms as a software developer, and the knowledge-building infrastructure and culture he had encountered there featured in most of the workshops and discussions he led. He was well-versed in business management literature, and supremely confident in the effectiveness of the business Discourse he relied on. Like many other Israelis, Eric’s personal experience (e.g. as a student and parent) led him to criticize the education system, which was not focused enough on measurable results in his opinion. Ambiguous educational goals tied to community, ethics, or identity, which are especially prominent in Israel, struck Eric as irrelevant to teaching, inasmuch as teaching is defined in professional terms.

The discursive shift

Prior to the February seminar, the Discourses employed by the team and the identities assumed by its members were primarily academic, which was par for the course at INBAR. Led by Liat and Dan, team members typically spoke in terms of theories, data, and research methods; and they conducted literature reviews and interviews to advance their understanding of teacher inquiry. Yet in his workshops at the seminar, Eric encouraged everyone to forgo their academic Discourse, and adopt elements drawn from the business Discourse that he associated with high-tech culture, instead. Although he coordinated this shift with Itai, Liat, and Dan to ensure that the goal of developing a tangible product would be attained, and despite the fact that Itai and Eric had collaborated on prior occasions, these team members had a hard time with the shift Eric advanced. The first interaction in the following sequence of three shows that when Eric’s efforts were overt, the group resisted them. The second interaction reveals some tensions and obstacles that emerged when there were multiple and incompatible Discourses at play. And finally, the third interaction shows how the use of a cognitive tool mediated a process of marketization, as the team adopted a business Discourse to engage in their educational pursuits.

Interaction 1: resistance

During the first day of the seminar, Anat and Amir claimed that none of the units at INBAR used protocols for evidence-based reflective inquiry of the sort that they encouraged K-12 teachers to adopt in their programs. In response, Eric argued that the business Discourse found in high-tech was superior to the practices in educational settings such as the INBAR Institute because reflective inquiry was part of the organizational DNA at high-tech firms. He claimed that reflective inquiry is part of the ‘KaizenFootnote3 culture found in high-tech firms’ (line 211 in our transcript). When Itai challenged Eric and argued that in many cases such practices in industry were superficial, the following interaction ensued:

In this interaction, Eric sought to outline a hierarchy, whereby the work ethics and culture found in high-tech, as expressed through the business Discourse he intended to import to the teacher inquiry team, are superior to what is commonly found in education. According to Eric, while Kaizen culture allows industry to see ‘far beyond the decimal point’ (line 246), education falters because it does not ascribe enough value to measurement (line 248). This has hindered the INBAR team members’ ability to move forward and will continue to do so (line 248).

Yet the team resisted Eric’s view. Dan argued that Eric had failed to consider the messiness of education, which stands in contrast to the simplicity of LEGOs, thus undermining such a naïve comparison (line 247). Itai argued that contrary to Eric’s claim (‘you’re wrong’), the Ministry of Education does in fact measure ‘loads of things’ (line 251). Later in the conversation, Michal recounted an example from education, where measurement did not contribute to success.

Throughout the interaction, Eric never walked back on his initial claim that due to its reliance on hard data, business Discourse is superior to the typical educational Discourse. However, a closer reading that draws on discourse analysis tools (Gee, Citation2014) indicates an important shift that occurred, which was meaningful in terms of the social identity Eric took on and in terms of how he positioned himself vis-à-vis the group. Initially, Eric’s use of the terms ‘Kaizen’ and ‘beyond the decimal point’ (line 246) identified him as a software engineer with a specialized language that enables him to maximize productivity in ways that educators typically cannot. At the outset, Eric supposed that by using such a vocabulary to identify in this way, he could position himself as an authoritative figure who possessed crucial expertise that other group members did not.

However, Dan’s resistance (line 247) called the superiority of Eric’s specialized vocabulary into question: these terms and the epistemology they embodied were irrelevant to any discussion of ‘messier’ educational aims, which required more nuance and uncertainty. As a result, Eric reverted to an everyday vocabulary, relinquishing the software engineer identity that was deemed irrelevant in favor of an ‘everyday person’ (Gee, Citation2011). Simultaneously, Eric also forwent his bid for a position of authority in the group: ‘this is my opinion as Eric not as the group moderator’ (lines 248, 250).

Interaction 2: incompatibility

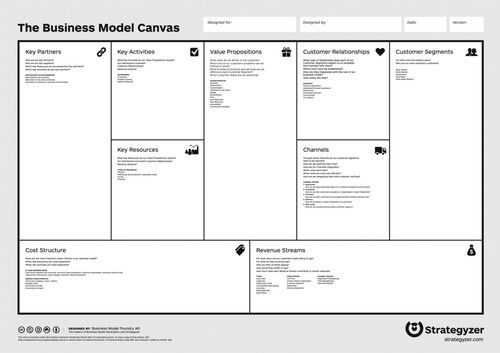

After a brief interlude, Eric introduced the Business Model Canvas (Osterwalder & Pigneur, Citation2010; see ) – a logic model from his days as a software engineer, which is designed to scaffold product development. The canvas is essentially a large poster where developers can brainstorm and discuss the key elements required for successful product development. The following text appears in separate fields on the poster, so that developer teams can address each prompt:

Key partners: Who are our key partners? Who are our key suppliers? Which key resources are we acquiring from partners? Which key activities do partners perform?

Key activities: What key activities do our value propositions require? Our distribution channels? Customer relationships? Revenue stream?

Key resources: What key resources do our value propositions require? Our distribution channels? Customer relationships? Revenue stream?

Value propositions: What value do we deliver to the customer? Which one of our customer’s problems are we helping to solve? What bundles of products and services are we offering each customer segment? Which customer needs are we satisfying?

Customer relationships: What types of relationships does each of our customer segments expect us to establish and maintain with them? Which ones have we established? How are they integrated with the rest of our business model? How costly are they?

Channels: Through which channels do our customer segments want to be reached? How are we reaching them now? How are our channels integrated? Which ones work best? Which ones are the most cost efficient? How are we integrating them with customer routines?

Customer segments: For whom are we creating value? Who are our most important customers?

Cost structure: What are the most important costs inherent to our business model? Which key resources are most expensive? Which key activities are most expensive?

Revenue streams: For what value are our customers really willing to pay? For what do they currently pay? How are they currently paying? How would they prefer to pay? How much does each revenue stream contribute to overall revenues?

Eric’s initial survey of the Business Model Canvas was followed by this exchange:

Eric was interrupted by Liat, who requested ‘to talk for a moment about what we consider a product’ (line 306). In line with the academic Discourse that had dominated the group’s interactions up to this point, Liat suggested that perhaps the team’s intellectual growth was an outcome that qualified, in and of itself, as a product:

Eric’s body language (lines 307, 323) indicated that he was stumped by Liat’s question and incapable of defining what type of product the team should develop, although his verbal response maintained that the team’s learning process did not qualify:

A close reading of this second interaction, highlighting the connections drawn by the interlocutors and the situated meanings they were negotiating, is revealing. In particular, the disputed meaning of the term ‘product’ was key. Early on, Eric defined the group’s goal: to ‘create some sort of product’ (line 305). Liat and Michal were not opposed to the notion of product development per-se, so long as their intellectual growth could also be defined as a product. Stated otherwise, their response constituted a call to reconsider the meaning of the term ‘product’ and agree on a new, expansive, and locally generated definition (lines 311, 321).

The new meaning that they proposed was intended to connect two Discourses: business and academe. However, to Eric, a product required more than personal knowledge; it needed to be tangible and have value for someone else. Hence, in his view, the connection and definition they were proposing was incomprehensible. This left Eric confused, as reflected in his cautious reply and hesitant body language (line 323).

Liat and Michal’s attempt to redefine the meaning of the term ‘product’ foregrounded the tension between the academic and business Discourses and the fact that the different Discourses employed by Eric and by the INBAR employees, respectively, reflected contradictory value systems. The chasm between the two Discourses, which became more apparent amid this interaction, further weakened Eric’s status as group moderator.

Interaction 3: adoption

Despite any initial resistance, confusion, or doubts, the teacher inquiry team spent the rest of the day using the Business Model Canvas per Eric’s instructions. In Interaction 1, when Eric had voiced the values underlying the logic model embodied by the Canvas along with a deep-seated criticism of typical, non-business, educational Discourses, he encountered resistance. Yet, these values were not explicitly articulated on the Canvas’s text, nor did the Canvas include any direct critique of other Discourses, which is likely what spared it from a similar fate. The Canvas led the group to adopt a new way of talking about teacher inquiry that drew heavily on the business Discourse, which Eric thought would bolster the team’s knowledge building capabilities. This became evident in a third interaction at the beginning of the second day of the seminar, when Shani presented her group’s progress to the rest of the team.

The new way of talking about teacher inquiry became evident when Shani defined the product they wanted to develop as ‘a tool for mapping obstacles and problems’ that teachers encounter when implementing teacher inquiry (line 401), and especially when she focused on the ‘target audience’ (line 402), which included leaders of communities of teachers and other professionals. This was a way of translating the conceptual mapping – which Eric had rejected a day earlier – into a tangible product with value for others, so that it was in line with the business Discourse he had advanced. Shani continued:

In this interaction, the group members marketized education by enacting a business Discourse. This was accomplished by a variety of means, first and foremost of which is the adoption of the specialized vocabulary that was drawn directly from the Business Model Canvas. Their conversation here focused on the tool’s ‘added value’ (line 423), and who the team’s main partners would be in developing, marketing, and rolling out the product (line 428) to serve customers (line 431).

This shift in the group’s Big-D Discourse endured throughout the academic year and the process of marketization went on to encompass much more than the group’s vocabulary. Indeed, this third interaction was a watershed moment that also marked the adoption of a new value system, culture, and technological tools. Between the months of February and June 2022, the learning community functioned primarily as a development team focused on product design that aimed to develop and launch a marketable product that would provide tangible benefits to a broad audience. Along these lines, the final two-day seminar, which was held in June 2022 and concluded the team’s work, was designed by Eric as a hackathon in which the members worked to test and launch a new website dedicated to teacher inquiry, slated to serve teachers and other INBAR contacts.

Discussion

In this article, I have taken a microanalytic approach to understand how the process of marketization through discourse unfolded in the moment-to-moment interactions between Eric, who represented the business world, and INBAR’s teacher inquiry team. In this case, the process of marketization was hardly a straightforward one. Initially, efforts at marketization were interpreted as an attempt to disrupt the power dynamics of the group and disempower Itai and Dan, whose positioning hinged on the academic discourse Eric was trying to supplant. Later on, there was confusion surrounding the question of how that Discourse might be employed, as Michal and Liat set out to renegotiate the meaning of the term ‘product’ in a way that would connect the academe and business, rather than replace one with another. Despite all of this, the community ultimately succumbed to Eric’s efforts, raising the question: Why? My analysis suggests that the Business Model Canvas played a crucial mediating role in the process of marketizing the teacher inquiry team’s discourse, where a direct approach fell short. There are at least three distinct ways in which this cognitive tool contributed to Eric’s efforts to supplant a Big-D Discourse that he imported from the high-tech sector into an educational setting.

The first interaction that I analyzed above highlighted how marketization is inseparable from power dynamics (see also Gramsci, Hoare, & Nowell-Smith, Citation1971). Underlying Dan and Itai’s initial resistance to Eric’s efforts to introduce a business discourse to education was a comparison that they viewed as unwarranted. Accepting Eric’s overt and explicit claim that the business discourse is superior to what is currently found in education required them to accept the notion that they – highly accomplished education professionals, and senior figures at INBAR – understand the education system poorly compared to a computer programmer. They were asked to acknowledge an equivalence between the two contexts; namely, that both fields ought to deal with measurable outcomes. Overtly, this was an equivalence that Dan and Itai rejected because in their eyes, Eric simply did not recognize the complexities of education; and in some cases, he was uninformed. On a less visible plane, Eric’s efforts had serious implications in terms of the other group members’ positioning and status within the group. So long as the academic Discourse was in play, Itai, Dan, and the other academics in the group were empowered and agentive. But as soon as that Discourse was compromised, their positions were threatened. The Business Model Canvas thus mediated the transition to a business Discourse because it was able to present itself as neutral and subvert the hierarchy, equivalence, and repositioning that some team members were unwilling to accept.

Second, as my analysis of the next interaction showed, Eric’s attempt at marketization through discourse sowed confusion. The confusion arose when Liat, Michal, and Eric could not fully agree on what constitutes an educational ‘product’. Liat and Michal were unwilling to forgo an academic Discourse when they made the case for defining their intellectual progress as a product. Eric rejected their approach and upheld a definition that construed education in terms of a business that creates products that are used by someone else. Here too, the Business Model Canvas played a key role in bridging the gap between the interlocutors because it allowed Liat and Michal to move forward in applying the business Discourse to the realm of education without explicitly foregoing their position. Indeed, when Shani revealed that the units at INBAR – i.e. members of the team and the units they represent – were their target audience (line 431), her view of what constitutes a product positioned her somewhere in between Liat and Michal on the one hand, and Eric on the other. The Canvas played a mediational role in translating their conceptual mapping into a tangible and usable product.

Finally, my fieldnotes also led me to conclude that the success of the Business Model Canvas stemmed from the fact that it met a willing audience. Despite any resistance and/or confusion that surfaced when the teacher inquiry team encountered Eric’s overt efforts at marketization, the INBAR institute itself was already geared towards the business Discourse that featured on the canvas. INBAR’s position in between the private and public sectors meant that the Institute saw itself as a service provider, and its employees measured their output in terms of well-defined KPIs dictated by managers. I therefore understood the team’s openness to the Business Model Canvas and the process of marketization mediated by it as part of a broader trend that had taken hold over the course of several years, perhaps dating back to INBAR’s establishment, decades ago.

Conclusion

Marketization is a complex process that involves reimagining education in new terms. When business or high-tech Discourses ‘infect’ (Gee, Citation2011, p. 38) or ‘colonize’ (Fairclough, Citation1993) education, this also translates into a new value system. Thus, one result of imagining education in business terms is that knowledge for its own sake is no longer a worthwhile pursuit, because it does not qualify as a product. In contrast, ‘knowledge in the form of an informational commodity’ (Lyotard, Bennington, & Massumi, Citation1984, p. 5) is valuable, because it is useful to others, and thus marketable.

Previous research has implicated discourse as key to the process of marketization. This article’s contribution lies in its microanalytic focus on the moment-to-moment interactions that unfolded among a group of educators who were presented with a Discourse that was imported from the business world and asked to adopt and apply it to their work. My findings problematize the process of marketization and highlight the complex interactive dynamics that characterized it. Far from being linear or straightforward, marketization in this case became entangled with the group’s power dynamics, sowed confusion, and ultimately relied on a cognitive tool to take hold.

Ethics statement

Approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee (Request #211201).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 From this point onwards, I distinguish between Big-D Discourses, spelled with a capital D, and all other uses of the term discourse.

2 In Hebrew, the same word denotes both manager and principal.

3 Kaizen is a Japanese term indicating a process of continuous improvement of the standard way of work that is popular in many businesses (Singh & Singh, Citation2009).

References

- Agar, M. (1986). Speaking of ethnography. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- Ball, S. J. (1993). What is policy? Texts, trajectories, and toolboxes. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 13(2), 10–17. doi:10.1080/0159630930130203

- Ball, S. J. (2007). Education plc: Understanding private sector participation in public sector education. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Blommaert, J., & Jie, D. (2020). Ethnographic fieldwork. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Connell, R. (2013). The neoliberal cascade and education: An essay on the market agenda and its consequences. Critical Studies in Education, 54(2), 99–112. doi:10.1080/17508487.2013.776990

- Fairclough, N. (1993). Critical discourse analysis and the marketization of public discourse: The universities. Discourse & Society, 4(2), 133–168.

- Gee, J. P. (2011). An introduction to discourse analysis: Theory and method (3rd ed.). New York: Routledge.

- Gee, J. P. (2014). How to do discourse analysis: A toolkit (2nd ed.). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Giddens, A. (1993). New rules of sociological method. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Gramsci, A., Hoare, Q., & Nowell-Smith, G. (1971). Selections from the prison notebooks of Antonio Gramsci. New York: Lawrence and Wishart.

- Harré, R. (2012). Positioning theory: Moral dimensions of social-cultural psychology. In J. Valsiner (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of culture and psychology (pp. 191–206). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Harvey, D. (2005). A brief history of neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lyotard, J.-F., Bennington, G., & Massumi, B. (1984). The Postmodern condition: A report on knowledge (Paperback edition). Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Mitchell, J. C. (1984). Case studies. In R. F. Ellen (Ed.), Ethnographic research: A guide to general conduct (pp. 237–241). London: Academic Press.

- Osterwalder, A., & Pigneur, Y. (2010). Business model generation: A handbook for visionaries, game changers, and challengers. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

- Ramiel, H. (2019). User or student: Constructing the subject in edtech incubator. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 40(4), 487–499. doi:10.1080/01596306.2017.1365694

- Ramiel, H. (2021). Edtech disruption logic and policy work: The case of an Israeli edtech unit. Learning, Media and Technology, 46(1), 20–32. doi:10.1080/17439884.2020.1737110

- Rampton, B., Maybin, J., & Roberts, C. (2015). Theory and method in linguistic ethnography. In J. Snell, S. Shaw, & F. Copland (Eds.), Linguistic ethnography: Interdisciplinary explorations (pp. 14–50). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Resnik, J. (2011). The construction of a managerial education discourse and the involvement of philanthropic entrepreneurs: The case of Israel. Critical Studies in Education, 52(3), 251–266. doi:10.1080/17508487.2011.604075

- Senor, D., & Singer, S. (2009). Start-up nation: The story of Israel’s economic miracle. New York: Twelve.

- Singh, J., & Singh, H. (2009). Kaizen philosophy: A review of literature. IUP Journal of Operations Management, 8(2), 51–72.

- Tamir, E., & Davidson, R. (2020). The good despot: Technology firms’ interventions in the public sphere. Public Understanding of Science, 29(1), 21–36. doi:10.1177/0963662519879368