ABSTRACT

Australian universities are mandated to implement non-academic on-entry evaluations for all initial teacher education candidates. Universities have introduced interviews, written applications, psychometric tests, and more recently, simulation. This research sought to determine if simulation as an evaluation tool had utility as a measure of teaching dispositions and its utility in measuring candidates’ pre-existing dispositions such as self-confidence, resilience, and conscientiousness during and after a classroom simulation evaluation session. The mixed method design explored students’ perceptions of the effectiveness of the simulation tool and evaluation of their own on-entry performance. The findings showed that the utility, fairness and validity of on-entry assessments of this entry requirement were justified and candidates’ self-confidence as a distal measure of classroom preparedness was affirmed. The implications of these data and findings include the refinement of processes and tools for assessing non-academic teaching dispositions and an expanded evidence base for assessing the suitability of candidates for initial teacher education.

Implications for policy and practice

Simulation is an effective on entry screening tool for measuring the disposition of initial teacher education (ITE) candidates.

Simulation exposes ITE candidates to authentic classroom dynamics and a safe learning environment.

ITE candidates perceive simulation as an effective means to evaluate their on-entry performance.

Simulation offers candidates the opportunity to practice teaching techniques to improve self-efficacy.

Introduction

The selection of prospective teachers is heavily influenced by government policy, social expectations, and economic costs (Goss and Sonnemann Citation2019; Hanushek and Rivkin Citation2012; McDonough et al. Citation2021). Current selection processes in Australian initial teacher education (ITE) rely heavily on proxies for academic ability, like the Australian Tertiary Admission Rank (ATAR), even though only 37% of ITE students enter through an ATAR pathway (Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership [AITSL Citation2019). More research is needed in relation to the link between intellectual capacity and teacher effectiveness (Bardach and Klassen Citation2020). The selection process and the release of graduates into Australian schools are supercharged with social and political debate arising from keen interest that stakeholders such as parents, schools and policymakers take around this issue (Pelliccione et al. Citation2019). Attracting high-quality candidates into ITE programmes and preparing them to be effective teachers are the two pillars of a new review of Australian ITE (Department of Education Skills and Employment Department of Education Skills and Employment Citation2021a, Citation2021b). The terms of reference were framed by how to encourage more high performing and highly motivated school leavers into ITE (Department of Education Skills and Employment Citation2021b). The review’s report now reiterates previous reviews (see Craven et al. Citation2014) to better prepare preservice teachers for the classroom (Louden et al. Citation2023); however, despite the scrutiny of their preparedness for the workforce and quality of their teaching, one group of key stakeholders remains absent in this issue, namely the ITE candidates themselves. They have not been engaged in these reviews, evaluations and re-alignments of ITE, including on-entry selection processes. This study captures the perceptions of ITE candidates on the effectiveness of simulation as an on-entry screening process in terms of being fair, robust and authentic. There is limited literature that investigates this perspective due to the recency of the introduction of screening into ITE protocols and the rather limited use of simulation in ITE preparation and education in Australia (Dieker et al. Citation2016; Ledger and Fischetti Citation2020).

Simulation affords what Gulikers, Bastiaens and Martens (Citation2005) describe as an authentic learning-related environment. It provides a context that reflects ‘the way knowledge and skills will be used in real life’ (p. 509). Simulation includes a physical or virtual environment that resembles the real world with all its complexity and limitations and provides exposure to the dynamics of the environment that are also present in real life (Herrington and Oliver Citation2000). Recent emphasis has been placed on using simulation as a pedagogical approach in ITE. It builds on the success of simulated clinical immersion (Tremblay et al. Citation2019), and simulation-based education used to prepare other professionals in the health system, military, mining and hospitality (Gough, Jones, and MacKinnon Citation2012). Simulation allows students to repeat practice in a safe and realistic learning environment, thus improving learning and providing opportunities to develop competencies to handle problems and situations in real time as if they would in the real world (Dieker et al. Citation2016; Kaufman and Ireland Citation2016; Keskitalo Citation2012; Ledger and Fischetti Citation2020). Simulation exposes students to experiences that are tailored to their professional field to test their ability to respond and make sound judgements. The perceptions and interpretations displayed by students within these simulations are shown to be valid predictors of later performance within work settings (Klassen et al. Citation2020). The Australian Government has expressed its concern that ‘not all entrants to initial teacher education are the best fit for teaching’ (Parker Citation2018, 4) with the need to balance academic skills with non-academic attributes and characteristics required in suitable ITE candidates (Craven et al. Citation2014). Simulation therefore offers a solution to this concern, by providing an authentic learning experience that can capture and measure the non-academic attributes and characteristics required to engage with students.

Literature review

Teacher selection

A review of literature by Menter et al. (Citation2010) identified a wide range of testing policies for selection of ITE candidates. The array of practices included processes to assess basic skills; pedagogical and content knowledge; application of knowledge; performance against standardised criteria; portfolios; and, performance-based measures. The authors reported that ‘there was little evidence to distinguish between ITE candidates who are competent to teach and those who are not’ (Menter et al. Citation2010, 27). More recently, AITSL and Australian teacher regulatory authorities have scrutinised university ITE programmes (AITSL Citation2019) to ensure that programme selection criteria and processes were sufficiently rigorous to deliver the necessary outcomes, building on Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency (TEQSA) recommendations (TEQSA Citation2020). These on-entry processes are associated with the complex task of identifying appropriate ITE candidates who are likely to become highly effective teachers (Klassen et al. Citation2020). The non-academic capabilities emphasised by AITSL’s mandate for strengthened programme selection processes include motivation to teach; strong interpersonal and communication skills; willingness to learn; resilience; self-efficacy; conscientiousness; organisational and planning skills (AITSL Citation2015).

Initial teacher education providers consider combinations of non-academic capabilities when selecting entrants into their programmes then collect evidence to justify a focus on these specific capabilities and the approaches taken to assess them. Within the context of ITE, testing candidates’ dispositions can add validity as a predictor of success in the ITE programmes; however, further research is needed to determine which tests offer the best predictive validity (Klassen and Kim Citation2019; Palmer, Bexley, and James Citation2011).

While tests of aptitude and preparedness are commonly held to be an objective predictor for success at university, evidence shows that the most commonly used tests have only moderate predictive power for university success (Craven et al. Citation2014). Craven et al. (Citation2014) also cite evidence that non-academic teaching qualities, namely teaching dispositions (such as self-efficacy, motivation and resilience), need to be evaluated and developed in preservice teachers in order for them to succeed in the teaching profession. While the literature refers to the effect of pre-ITE skills, abilities and dispositions on both ITE students’ success in their programme and on pupils’ achievement once teachers enter the profession (Parker Citation2018), more research is needed (Bardach, Klassen, and Perry Citation2021). This study seeks to offer concrete support for the use of classroom simulation technology to identify and evaluate ITE candidates’ dispositions prior to the commencement of the teaching programme. This has utility as a self-assessment tool for candidates and as an evidence-based selection tool for ITE programme leaders.

Authentic learning environments

Simulation has been identified as a valuable experiential and authentic learning practice that can increase student engagement in the learning activities and is more likely to promote deeper learning (Mattar Citation2018). For preservice teachers, like other novice learners, immersive technologies can be valuable tools in early candidacy evaluation, development and training. Ledger and Fischetti (Citation2020) suggest that the virtual simulated classroom affords teacher educators a controlled learning space that offers consistency in moderation and diagnosis of students’ practice (p. 37). For candidates and preservice teachers, simulated classrooms offer safe spaces for them to receive immediate and ongoing feedback about their teaching practice and timely opportunities to implement change (Dieker et al. Citation2016). Simulated teaching experiences can also offer preservice teachers the opportunity to attempt and rehearse new practices and skills without fear of negative repercussions or consequences (McGarr Citation2021).

The opportunities and challenges presented by simulations within ITE are set within the context of considerable disruption to traditional pedagogies and evolving understandings of the benefits they offer (Mulvihill and Martin Citation2023). Some adoption of teaching simulations within ITE has been in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (Keane and Chalmers Citation2023), whereas others, like what is reported on here, are the result of sophisticated pedagogical innovations aimed at developing preservice teachers (Goff Citation2023). Aligned to the latter, our research sought to determine if evaluation of the on-entry simulation tool had utility as a measure of 1) teaching dispositions within a safe, exploratory teaching environment, and 2) it’s utility in measuring candidates’ pre-existing dispositions such as self-confidence, resilience, and conscientiousness during and after a classroom simulation evaluation session.

Simulation technology

Simulation technology offers a blend of virtual reality technology and live human performance that creates powerful and immersive learning simulations for ITE teaching candidates. This mixed reality learning environment (or MRLE) technology is playing an important role in ITE programmes (Kaufman and Ireland Citation2016; Ledger and Fischetti Citation2020) with recent advances that include sophisticated avatars as virtual students in a virtual classroom delivering synchronous responses (Dalinger et al. Citation2020).

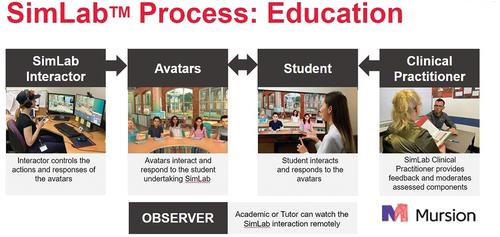

One of the latest mixed reality learning environment options is SimLab™, a Mursion product, which builds on work developed at the University of Central Florida. It offers technology that is not in the classroom but rather, it is the classroom (Ledger and Fischetti Citation2020). The SimLabTM technology provides a ‘real time’ mixed reality learning environment with classroom pupils being represented by avatars. A human looped ‘interactor’ manipulates five avatars in a similar manner as a ‘puppeteer’. Each avatar is personalised in form, voice, and persona and their identities are cognitively and behaviourally modelled on the work of psychologist William Long’s (Citation1989) categorisation of adolescent personalities.

This smart learning platform offers ITE candidates a safe, non-judgemental, synchronous and interactive environment to undertake their first foray into the world of teaching, as seen in . Students enter the mixed reality learning environment and are faced with authentic classroom scenarios in which they have to engage and interact. Authenticity is promoted where perception of the environment inevitably leads to specific courses of action (see Situated Learning Theory; Lave and Wenger Citation1991). The student avatars are created to personify students that are likely to attend a class for that candidate based on the candidate’s identified teaching level or age group. All other dispositions and environmental factors have been included in the programming of the classroom based on simulation research that has informed the development of the avatars and ITE teaching requirements (Dieker et al. Citation2016). Moreover, a differentiating factor in the SimLabTM on-entry evaluation tool is its synchronous capabilities which provides real-time feedback as a critical element of the authentic learning process (González-Martínez, Martí, and Cervera Citation2019).

Research shows that users of the technology become empathetic to the emotions, abilities and circumstances of the avatar (Dieker et al. Citation2016). The simulation process, as seen in , identifies the agents in the simulation and offers a visual representation of the graphical view of the interface between the candidate and the avatars.

Figure 2. Components of SimLabTM HITL simulation at Murdoch University (Ledger Citation2017).

The approach and resources detailed here have enabled this university to position itself as a leader in simulation within Australia, being the first in the southern hemisphere to introduce mixed-reality learning environments into ITE to practice and prepare its graduates as they transition into the workforce. In response to AITSL Program Standard 3.2, the university requires the applicant to successfully respond to a five-minute SimLabTM experience. Consistent with contemporary descriptors of effective twenty-first century teachers, the evaluation protocols seek to “… develop links between content knowledge, skills, attitudes and application criteria (Casey and Childs Citation2011, 2). There are four evaluation criteria for judging dispositions. The applicant must achieve success in at least three of the four criteria:

Language and discourse: Classroom appropriate words; Comprehension; Coherence and Fluency; Clarity

Improvisation: Initiative; Resourcefulness; Timely; Appropriate Responses

Rapport building: Interpersonal skills (communication, engagement, active listening, caring); Questioning skills (questioning range, coherence, for understanding/learning)

Teaching self-efficacy: Command (self-confidence, personal and situation control); Organisation (level of effective preparation)

While these dispositions are evaluated as students enter ITE programmes at the university, this interaction marks their first foray into simulation and their first introduction to reflective practice as a future educator.

Current study

A key area of our research interest is students’ perception of the utility of the SimLabTM on-entry evaluation for ITE selection. Their perceptions of its fairness and validity in measuring their self-confidence as a distal measure of classroom preparedness are of particular research value. We sought to explore students’ views on their learning environment (Devlin Citation2002) and to gain understanding of how the on-entry simulation laboratory experience exposed candidates to classroom dynamics that prompted them to demonstrate the required teaching dispositions.

Research questions

What were the candidates’ perceptions of the on-entry simulation evaluation session?

In what ways did the candidates perceive on-entry evaluations as a reliable measure of their dispositions for teaching?

Did the candidates’ demonstration of the AITSL dispositions predict their self-confidence in the on-entry evaluation experience?

Methodology

This study forms one of a series that represent a research project that employs quantitative and qualitative data collection at different points of time to investigate an underlying phenomenon (Creswell et al. Citation2011). It is anticipated that the exploratory design will provide a better understanding of on-entry screening and how it is perceived by teaching candidates. It also goes some way to providing data on the development of the instrument. This paper uses quantitative methods to inform the next iteration of the screening process. The survey, as a quantitative instrument, was used to capture the responses of ITE students’ global perceptions of the evaluation tool. Future phases of the research will include qualitative, semi-structured interviews with preservice teachers following their on-entry screening. This qualitative phase will seek to capture participants’ perspectives and insights close to the point of participation in the screening process and early in their ITE programme.

The context

As a prerequisite to enter into the ITE programme at the host university, candidates are required to participate in a 5-minute classroom simulation session prior to commencement of their first semester of their programme. The candidates are instructed to prepare for this session by reviewing the SimLabTM instructions, video example, dispositions of interest, and operational guidelines. As part of their preparation, candidates are encouraged to focus their attention on identified dispositions during the five-minute lesson.

The process

On the day, candidates are given an option to undertake their on-entry evaluation either as an on-campus or online experience. The candidate is asked to present at the Simulation laboratory session at their appointed time. They are greeted by the SimLabTM Clinical Practitioner who revises the technology ‘how to’ protocols. During and immediately post-lesson, the interactor and the clinical practitioner independently evaluate and score the presentation on the four dispositions and apply an overall rating of the candidate’s presentation (five scores). A Pass/Fail grade is determined. A Fail grade is recorded when two or more dispositions are deemed unsatisfactory. If a Fail grade is recorded for this first session, a repeat evaluation session is scheduled. Before undertaking a repeat evaluation, coaching is provided by an academic staff member. Moreover, the initial evaluation is used as an identifier of the candidate needing additional support during their first year of ITE.

The simulation session

In the on-entry session, the simulation is operationalised as shown in . There are four key agents involved in the process. These include the candidate, the avatars, the interactor, and the clinical practitioner. The candidate is the individual entering the ITE programme (and completing the on-entry screening as an early engagement process). The avatars are five virtual child characters representing school-aged students within a simulated learning environment. The interactor is a professional improvisation actor responsible for controlling the behaviour and interaction of the avatars. The clinical practitioner is a qualified and highly experienced teacher who facilitates the on-entry screening and liaises between the candidate and interactors during the screening process. The session involves the candidate teaching the five avatars within a defined programme – introduction, teach something, engage, reflect on process. Post-simulation, the candidate is advised that their pass/fail feedback will be delivered via phone or email within two working days and will determine the next stage of the process, particularly if they have not passed this evaluation. At this point, if the candidate has met all the ITE programme entry requirements, they are advised of their successful progress into the ITE programme. Should the candidate require further evaluation, they will be advised of this along with their feedback and the process going forward. A whole of cohort summary of results across the four dispositions is provided to the programme coordinators and offers good insight into the incoming cohort.

Participants

All candidates applying for mid-year entrants formed the surveyed sample (n = 104). The aim was to investigate their perceptions on the utility of SimLabTM as an evaluation tool for entry selection into the university. The sample was cleaned and reviewed, with the final dataset as n = 68 (f = 55, m = 13). Ages ranged from 18 and 30+; however, no further information was requested regarding how much older than 30 years of age each relevant respondent was at the time of data collection.

Data collection

Regard for student wellbeing underpinned project development. While all ITE programmes set entry criteria, simulated on-entry evaluation of ITE candidates’ teaching dispositions potentially amplifies the challenge of commencement. Applying a research focus to these entry processes has the potential to further exacerbate ITE candidates’ concerns within the screening itself. The research team engaged in rigorous project development and human research ethics processes to develop data collection methods that would minimise the potential risks to commencing participating ITE candidates. The research team acknowledged the inherent relationships of power existing between commencing ITE candidates and educational researchers and incorporated steps into participant recruitment, selection and participation to mitigate the impact wherever possible. Approval was sought from the university’s human research ethics committee prior to participant recruitment, and project approval was obtained on the basis of these embedded safeguards (approved human research ethics protocol no. 2020/147). Information about the study and confidentiality statements were provided to commencing ITE candidates prior to data collection. Once candidates accessed the survey portal (Qualtrics Citation2021), participant consent was obtained as a forced response within the first item on the survey. Participants then responded to a series of items relating to their perceptions of the evaluation process.

The survey questions

The survey was constructed intuitively by the researchers and aligned directly to the AITSL recommended non-academic dispositions (AITSL Citation2015) and the purpose designed screening assessment rubric. First, following the stem ‘SimLab entry screening is a good measure of my …’ candidates recorded their perceptions of the utility of the on-entry screening experience through the lens of their pre-entry dispositions. Second, candidates rated the experience as an opportunity to display four teaching qualities (language and discourse, improvisation, confidence, and rapport building) that framed the assessor’s rubric. Respondents were asked to reply on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) with a neutral option.

Data analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS v24 to model the relationship between the AITSL non-academic dispositions measured and the outcome variables. Accordingly, the study employed a multiple linear regression analysis because the independent, predictor variables and the dependent, criterion variable were all continuous and normally distributed. All other relevant assumptions were deemed to have been met. Pearson product moment correlation coefficients were obtained to assess the strength of the association between the variables and possible multicollinearity (Coakes, Steed, and Ong Citation2009). First, we tested the correlations between the 11 variables, of which seven items were identified by AITSL as key capabilities associated with successful teaching: self-efficacy (self-confidence), motivation to teach, willingness to learn, resilience, conscientiousness and organisational and planning skills, and four were the programme-specific variables used to evaluate candidate performance. Age and gender were explored as covariates in this analysis to establish group differences for perceived self-confidence in the pre-entry ITE cohort. Next, multiple regression analyses were conducted to assess the predictive strength and importance of the relationship between the outcome variable: motivation to teach, resilience and self-confidence and the predictor variables as seen in in a two-model process. In model 1, we tested the project-specific variables as predictors of perceived self-confidence. Model 2 included all predictor variables as shown in . We draw from the analysis to make inferences and recommendations.

Table 1. Survey items derived from AITSL recommended non-academic dispositions and ratings for each item.

Results

The findings centre around the AITSL-recommended non-academic dispositions and ratings for each item (see ) and the survey items derived from the dispositions demonstrated in the on-entry evaluation experience (see ). In combination, the correlations highlight the strong and positive relationship between the two sets of measures. Participants' responses indicate strong support for the use of the evaluation tool to measure AITSL dispositions: self-confidence (M = 4.04, SD = .81), motivation (M = 4.19, SD = .86), resilience (M = 3.79, SD = .80), conscientiousness (M = 4.03, SD = .80) and organisational and planning skills (M = 4.24, SD = .65). Performance measures were reported as follows: language and discourse skills (M = 4.09, SD = .75), improvisation skills (M = 4.22, SD = .67) and rapport-building skills (M = 3.96, SD = .75).

Table 2. Survey items derived from the dispositions demonstrated in the on-entry evaluation experience.

Findings

Correlations

The linear relations between the variables recommended by AITSL (see ) were found to be strongly, positively and significantly correlated. Willingness to learn, r = .47, and conscientiousness, r = .64, p < .01 were most significantly and positively associated with self-confidence as the criterion variable. Resilience was most strongly associated with conscientiousness, r = .62, p < .01. The linear relations between variables evaluated in the classroom simulation (see ) were found to also positively correlate with self-confidence as a criterion variable. Language and discourse skills, r = .42 and improvisation skills, r = .37, p < .001 are considered positive, moderate associations with the candidates’ self-confidence.

Age and gender

There was no significant age difference in candidates’ perceived self-confidence after their first on-entry session, F (3,63) = 1.786, p = .159. Further, there were also no significant gender differences, F (1,65) = .025, p = .874 for this sample. This supports our premise that the on-entry evaluation process serves all candidates equally.

Predictive effects on dispositions

We used standard regression (see ) to predict candidates’ self-confidence as a key criterion of teaching using the combination of the six remaining AITSL dispositions in one model. In combination, the predictor variables accounted for a significant 46% of variance in candidates’ perceived self-confidence, R2 = .461, adjusted R2 = .41, F (6,60) = 8.56, p =.000.

Table 3. Unstandardised (B) and standardised (β) regression coefficients, squared semi-partial correlations (sr2) for each predictor in a hierarchical regression model predicting candidates’ perceived self-confidence.

We then used hierarchical regression to predict candidates’ self-confidence as a key criterion for teaching using the combination of the six remaining AITSL dispositions and the four items used in the evaluation tool in a two-step model. In combination, the predictor variables accounted for a significant 75% of variance in candidates’ perceived self-confidence, R2 = .560, adjusted R2 = .48, F (6,56) = 4.960, p =.000. Significant uniquely contributing predictors include rapport-building skills, resilience and conscientiousness. Applying statistical power conventions, a combined effect size of f =.50 can be considered ‘large’ in magnitude (Cohen Citation1988).

Discussion

This study explored teaching candidates’ perceptions of on-entry simulation, if the experience was a reliable measure of their dispositions for teaching, and if their predicted self-confidence aligned to the AITSL dispositions.

The first research question captured the perceptions of ITE students on the utility of simulation as an on-entry screening process in terms of fairness and reliability and its impact on self-confidence. Teaching candidates reported strong and positive perceptions for the on-entry evaluation tool. The strong and positive correlations highlighted associations between the AITSL recommended dispositions and the performance measures (dispositions) in the evaluation session. We can conclude from the findings that ITE candidates perceive simulation as an effective means to evaluate their on-entry performance.

The perceptions and beliefs preservice teachers bring with them into ITE influence how they understand themselves and how they engage with learning to teach (Fajet et al. Citation2005). Teaching candidates perceive teaching to be relational and interpersonal and place significant emphasis on their own non-academic qualities as indicators of being a good fit for teaching. How preservice teachers perceive their capacity to integrate personal qualities with teaching roles and responsibilities is fundamental to learning to teach (Flores Citation2020). This professional identity work is a critical part of being and becoming a teacher (Lutovac and Assunção Flores Citation2021). Beauchamp and Thomas (Citation2009) argue that this identity work needs to be an intentional and core component of ITE.

Preservice teachers’ professional identity work incorporates evolving understandings of self as teacher and perceived capacity to respond to the roles and responsibilities of teaching (Gracia et al. Citation2021). This identity work is underpinned by retrospective thinking, reflection on teaching and reflection in action, which happens in the course of learning to teach (Beauchamp and Thomas Citation2010). Importantly, ITE provides the circumstances and opportunities for preservice teachers to experience a range of interactions and experiences essential for learning about oneself in relation to teaching (Lutovac and Assunção Flores Citation2021). How our participants (our teaching candidates) engaged with and reflected on the experience of on-entry screening through simulated teaching is aligned to this agenda and fundamental to initiating this identity work at commencement of their ITE programme. Their perceptions about this process highlight the significance and effectiveness of it. How preservice teachers respond to simulated and virtual teaching through digital technologies reflect the beliefs they hold about their capacity to work in new and unfamiliar ways and how these experiences are embedded within ITE. In particular, preservice teachers’ concern for adopting and engaging with new technologies within ITE is connected to existing perceptions and beliefs about what learning and learning environments should look like (Cooper et al. Citation2019) and the age and developmental needs of their students (Dong and Mertala Citation2021). Preservice teachers’ experiences within ITE provide the basis for disrupting, consolidating, extending and replacing beliefs and perceptions about oneself and the realities of teaching (Chong, Low, and Goh Citation2011). Failure and complexity are a valuable component of this process (Lutovac and Flores Citation2021). As a result, the participants’ views highlight the on-entry screening through simulated teaching as a valuable, effective process for helping candidates better understand themselves, early experiences within ITE, and to develop confidence to approach their future work.

Connected to this, the second question in this study is answered by the relatively strong predictive value of the dispositions on candidates’ perceived self-confidence as a key outcome of simulation sessions used in teacher preparation programmes (Kaufman and Ireland Citation2016). Rapport-building skills, resilience and conscientiousness significantly and positively predicted candidates’ self-confidence (self-efficacy) in their evaluation session.

The third question related to the candidates’ demonstration of the AITSL dispositions to predict their self-confidence in the on-entry evaluation experience. Significant uniquely contributing predictors included rapport-building skills, resilience and conscientiousness. The simulated environment afforded an authentic, safe learning experience for the students to display these key dispositions. Typically, opportunities to observe these dispositions has been in real classroom settings (Ledger and Fischetti Citation2020).

The findings to our research question have synergy with the work of Ferguson (Citation2017) and Dalinger et al. (Citation2020) who reported that participants expressed a sense of preparedness to handle situations they had experienced in the simulation session should they encounter similar situations in the future. These strong and significant predictors of important classroom skills support the use of tools such as the SimLabTM on-entry evaluation. As a consequence of the SimLabTM evaluation, and as evidenced through their responses, preservice teachers were able to reflect on their experience and identified the simulation session as valuable for ongoing practice, reflection and classroom preparedness. These sentiments affirm Zeichner’s (Citation1994) call for the inclusion of reflective practice strategies in ITE programmes and for ITE candidates to begin to hone their reflective practices early in their preparation. The utility of the evaluation tool helps both teaching candidates to recognise and develop their teacher efficacy (self-confidence) and allows the evaluators to diagnose and support candidates to further fine-tune less developed dispositions as they progress through their ITE programme. Whilst speculative, the benefits of the on-entry simulation session and its evaluative process have the capacity to impact multiple stakeholders: preservice teachers’ improved confidence, resilience and classroom skills such as rapport-building; and, a diagnostic tool for academics and for AITSL and government policymakers – all potentially serving to support better prepared teaching graduates for the workforce.

Limitations

Specific limitations exist for two questions within the survey instrument, and steps have been taken to ensure that these issues do not undermine the reliability and rigour of analysis and interpretations of data within the research. Two questions contained within the survey instrument are compound (double-barrelled) items, meaning data from these are unreliable. While the questions have been retained within the tables to demonstrate the survey items in their original form, these data have been removed from analysis and do not feature within interpretation or discussion of findings.

Question 2,

(The SimLab entry evaluation was a good measure of my interpersonal and communication skills) conflates interpersonal skills with the capacity to communicate them. While interpersonal skills are considered essential non-academic capabilities for teachers and are expressed through teachers’ disposition and communication, framing the question in this way (and by doing so making this a double-barrelled question) means the data are unreliable. In response, related data have been excluded from interpretation of analysis and discussion of findings.

Question 3,

(The On-Entry SimLab evaluation was a good measure of my confidence and skills to teach) conflates participants’ perceptions about confidence to teach with their perceptions about their developing skills to teach. While these are understood to be interrelated, linking them within the same survey item means the data from this item is unreliable and unusable. In response, related data have been excluded from interpretation of analysis and discussion of findings.

It is important to note, self-confidence was investigated independently (, Question 5) and so the above limitation should not be applied to this measure.

Certain limitations preclude the generalisability of this study’s findings and the results should be interpreted with caution. We acknowledge the limitations of self-reporting, such as bias, selective recall, question phrasing and social desirability responses; however, self-reporting is considered an essential methodology to capture the self-efficacy of preservice teachers and its utility enabled a greater number of participants to be included. It should be noted that there were only 13 male participants in this sample, which is consistent with the ratio of female to male teaching candidates in other ITE research (Dalinger et al. Citation2020). These insights were considered through a critical lens, to identify the benefits and challenges of the evaluation tool through justified interpretations of participants’ shared perspectives.

Future research

As a research team, we have identified a need to prioritise student voice in relation to on-entry screening processes. As such, future work is planned to interview preservice teachers within six months of their first on-entry simulation session to explore their affective and psychological reactions to the on-entry session and to better understand the utility of the evaluation on their subsequent learning, simulation sessions, and school-based practicum.

Conclusion

Educators continue to seek opportunities to use emerging technologies to enhance learning environments (Power Citation2015). In this instance, teacher educators have conceptualised an on-entry learning environment and measure to evaluate preservice teachers entering ITE programmes. This on-entry measure presents the perspectives of preservice teachers for the effectiveness of this smart assessment tool and its ability to measure their individual dispositions for teaching as aligned to the AITSL recommended selection skills. Students reported positive perceptions of the utility of the SimLabTM on-entry evaluation for ITE selection and their perception of its fairness and validity in measuring candidates’ self-confidence as a distal measure of classroom preparedness. Students perceived the on-entry SimLabTM evaluation as a good measure of their improvisation skills, rapport building and discourse. Moreover, analysis confirmed that rapport-building skills, resilience and conscientiousness provide significant contributing predictors of self-confidence to teach.

This paper supports teaching simulations as an effective, fair, valid and robust tool for identification of preservice candidates’ dispositions to teach. Simulated teaching as an on-entry screening tool provides preservice teachers with authentic real-life experiences in which they can begin their reflective practice and diagnostic journey into teacher education. This process also offers ITE educators diagnostic data on on-entry dispositions of candidates. As such, we recommend more studies on the affordances of simulation in on-entry evaluation and mainstream teacher education programmes. We see a need for comparative studies and further investigation of on-entry evaluation tools being used to capture the non-academic qualities of teaching candidates in universities across Australia. We also see an opportunity for further research into on-entry screening through teaching simulations to establish a basis for predicting candidates’ self-confidence to teach and preservice teachers’ future performance within practicum settings.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- AITSL (Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership). 2015. Action Now: Selection of Entrants into Initial Teacher Education – Guidelines - Factsheet. Melbourne, Australia: AITSL.

- AITSL (Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership). (2019). Initial Teacher Education: Data report 2019. Melbourne, Australia: AITSL.

- Bardach, L., and R. M. Klassen. 2020. “Smart Teachers, Successful Students? A Systematic Review of the Literature on teachers’ Cognitive Abilities and Teacher Effectiveness.” Educational Research Review 30 (100312): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2020.100312.

- Bardach, L., R. M. Klassen, and N. E. Perry. 2021. “Teachers’ Psychological Characteristics: Do They Matter for Teacher Effectiveness, teachers’ Well-Being, Retention, and Interpersonal Relations? An Integrative Review.” Educational Psychology Review 34 (1): 259–300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-021-09614-9.

- Beauchamp, C., and L. Thomas. 2009. “Understanding Teacher Identity: An Overview of Issues in the Literature and Implications for Teacher Education.” Cambridge Journal of Education 39 (2): 175–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057640902902252.

- Beauchamp, C., and L. Thomas. 2010. “Reflecting on an Ideal: Student Teachers Envision a Future Identity.” Reflective Practice 11 (5): 631–643. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2010.516975.

- Casey, C., and R. Childs. 2011. “Teacher Education Admission Criteria as Measure of Preparedness for Teaching.” Canadian Journal of Education 34 (2): 3–20.

- Chong, S., E. L. Low, and K. C. Goh. 2011. “Emerging Professional Teacher Identity of Pre-Service Teachers.” Australian Journal of Teacher Education 36 (8): 50–64. https://doi.org/10.14221/1835-517X.1530.

- Coakes, S. J., L. G. Steed, and C. Ong. 2009. SPSS: Analysis without Anguish: Version 16 for Windows. Milton, Australia: John Wiley & Sons Australia.

- Cohen, J. 1988. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. New York: L. Erlbaum Associates.

- Cooper, G., H. Park, Z. Nasr, L. P. Thong, and R. Johnson. 2019. “Using Virtual Reality in the Classroom: Preservice teachers’ Perceptions of Its Use as a Teaching and Learning Tool.” Educational Media International 56 (1): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523987.2019.1583461.

- Craven, G., K. Beswick, J. Fleming, M. Green, B. Jensen, E. Leinonen, and F. Rickards 2014. Action Now: Classroom Ready Teachers (Teacher Education Ministerial Advisory Group Final Report). Department of Education and Training.

- Creswell, J. W., A. C. Klassen, V. L. Plano Clark, and K. Clegg Smith. 2011. Best Practices for Mixed Methods Research in the Health Sciences. Bethesda, Maryland: National Institutes of Health.

- Dalinger, T., K. B. Thomas, S. Stansberry, and Y. Ying Xiu. 2020. “A Mixed Reality Simulation Offers Strategic Practice for Pre-Service Teachers.” Computers & Education 144 (103696): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103696.

- Department of Education Skills and Employment. (2021a). Quality Initial Teacher Education Review - Discussion Paper. Australian Government.

- Department of Education Skills and Employment. 2021b. Quality Initial Teacher Education Review - Terms of Reference. Canberra, Australia.

- Devlin, M. 2002. “An Improved Questionnaire for Gathering Student Perceptions of Teaching and Learning.” Higher Education Research & Development 21 (3): 289–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/0729436022000020788.

- Dieker, L., B. Lignugaris-Kraft, M. Hynes, and C. Hughes. 2016. “Mixed Reality Environments in Teacher Education: Development and Future Applications.” In Online in Real Time: Using Web 2.0 for Distance Education in Rural Special Education, edited by B. L. Ludlow and B. C. Collins, 122–131. Morgantown, West Virginia: American Council on Rural Special Education.

- Dong, C., and P. Mertala. 2021. “It is a Tool, but Not a ‘Must’: Early Childhood Preservice teachers’ Perceptions of ICT and Its Affordances.” Early Years 41 (5): 540–555. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2019.1627293.

- Fajet, W., M. Bello, S. A. Leftwich, J. L. Mesler, and A. N. Shaver. 2005. “Pre-Service teachers’ Perceptions in Beginning Education Classes.” Teaching and Teacher Education 21 (6): 717–727. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2005.05.002.

- Ferguson, K. 2017. “Using a Simulation to Teach Reading Assessment to Preservice Teachers.” The Reading Teacher 70 (5): 561–569. https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1561.

- Flores, M. A. 2020. “Feeling Like a Student but Thinking Like a Teacher: A Study of the Development of Professional Identity in Initial Teacher Education.” Journal of Education for Teaching 46 (2): 145–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2020.1724659.

- Goff, W. 2023. “VR Simulations to Develop Teaching Practice with Pre-Service Teachers.” In Technological Innovations in Education, edited by S. Garvis and T. Keane. Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-2785-2_2.

- González-Martínez, J., M. C. Martí, and M. G. Cervera. 2019. “Inside a 3D Simulation: Realism, Dramatism and Challenge in the Development of students’ Teacher Digital Competence.” Australasian Journal of Educational Technology 35 (5): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.3885.

- Goss, P., and J. Sonnemann. 2019. Raising the Status of Teaching: Submission to the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Education and Employment. Carlton, Australia: Grattan Institute.

- Gough, S. M., H. N. Jones, and R. MacKinnon. 2012. “A Review of Undergraduate Interprofessional Simulation-Based Education (IPSE).” Collegian 19 (3): 153–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2012.04.004.

- Gracia, E. P., R. S. Rodríguez, A. P. Pedrajas, and A. J. Carpio. 2021. “Teachers’ Professional Identity: Validation of an Assessment Instrument for Preservice Teachers.” Heliyon 7 (9): e08049. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08049.

- Gulikers, J. T. M., T. J. Bastiaens, and R. L. Martens. 2005. “The surplus value of an authentic learning environment.” Computers in Human Behavior 21 (3): 509–521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2004.10.028.

- Hanushek, E. A., and S. G. Rivkin. 2012. “The Distribution of Teacher Quality and Implications for Policy.” Annual Review of Economics 4 (1): 131–57. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-economics-080511-111001.

- Herrington, J., and R. Oliver. 2000. “An Instructional Design Framework for Authentic Learning Environments.” Educational Technology Research & Development 48 (3): 23–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02319856.

- Kaufman, D., and A. Ireland. 2016. “Enhancing Teacher Education with Simulations.” Tech Trends 60 (3): 260–267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-016-0049-0.

- Keane, T., and C. Chalmers. 2023. “The Role of Virtual Reality Professional Experiences in Initial Teacher Education.” In Technological Innovations in Education, edited by S. Garvis and T. Keane. Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-2785-2_1.

- Keskitalo, T. 2012. “Students’ Expectations of the Learning Process in Virtual Reality and Simulation-Based Learning Environments.” Australasian Journal of Educational Technology 28 (5): 841–856. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.820.

- Klassen, R. M., and L. E. Kim. 2019. “Selecting Teachers and Prospective Teachers: A Meta-Analysis.” Educational Research Review 26:32–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2018.12.003.

- Klassen, R. M., L. E. Kim, J. V. Rushby, and L. Bardach. 2020. “Can We Improve How We Screen Applicants for Initial Teacher Education?” Teaching and Teacher Education 87 (102949): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.102949.

- Lave, J., and E. Wenger. 1991. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ledger, S. 2017. Learning to Teach with Avatars (Innovative Case Study). Murdoch, Australia: Murdoch University.

- Ledger, S., and J. Fischetti. 2020. “Micro-Teaching 2.0: Technology as the Classroom.” Australasian Journal of Educational Technology 36 (1): 37–54. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.4561.

- Long Jnr, W. A. 1989. “Personality and Learning. 1988 John Wilson Memorial Address.” Focus on learning problems in mathematics 11 (4): 1–16.

- Louden, B., M. Simons, J. Donovan, A. Peach, and R. West 2023. Strong Beginnings: Report of the Teacher Education Expert Panel. Australian Government. https://www.education.gov.au/quality-initial-teacher-education-review/resources/strong-beginnings-report-teacher-education-expert-panel.

- Lutovac, S., and M. Assunção Flores. 2021. “‘Those Who Fail Should Not Be teachers’: Pre-Service teachers’ Understandings of Failure and Teacher Identity Development.” Journal of Education for Teaching 47 (3): 379–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2021.1891833.

- Mattar, J. 2018. “Constructivism and Connectivism in Education Technology: Active, Situated, Authentic, Experiential, and Anchored Learning.” RIED Revista Iberoamericana de Educación a Distancia 21 (2): 201–217. https://doi.org/10.5944/ried.21.2.20055.

- McDonough, S., L. Papatraianou, A. Strangeways, C. F. Mansfield, and D. Beutel. 2021. “Navigating Changing Times: Exploring Teacher Educator Experiences of Resilience.” In Cultivating Teacher Resilience: International Approaches, Applications and Impact, edited by C. F. Mansfield, 279–294. Singapore: Springer.

- McGarr, O. 2021. “The Use of Virtual Simulations in Teacher Education to Develop Pre-Service teachers’ Behaviour and Classroom Management Skills: Implications for Reflective Practice.” Journal of Education for Teaching 47 (2): 274–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2020.1733398.

- Menter, I., M. Hulme, D. Elliott, and J. Lewin. 2010. Literature Review on Teacher Education in the 21st Century. Edinburgh, Scotland: The Scottish Government.

- Mulvihill, T. M., and L. E. Martin. 2023. “Exploring Virtual and In-Person Learning: Considering the Benefits and Issues of Both.” The Teacher Educator 58 (3): 245–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/08878730.2023.2213474.

- Palmer, N., E. Bexley, and R. James. 2011. Selection and Participation in Higher Education : University Selection in Support of Student Success and Diversity of Participation. Melbourne, Australia: AEI.

- Parker, S. 2018. Literature Review on Teacher Education Entry Requirements. Edinburgh, Scotland: University of Glasgow.

- Pelliccione, L., V. Morey, R. Walker, and C. Morrison. 2019. “An Evidence-Based Case for Quality Online Initial Teacher Education.” Australasian Journal of Educational Technology 35 (6): 64–79. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.5513.

- Power, C. 2015. The Power of Education: Education for All, Development, Globalisation and UNESCO. Netherlands: AEI.

- Qualtrics. 2021. Online Survey Software. Qualtrics. https://www.qualtrics.com/au/.

- TEQSA (Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency). 2020. Improving the Transparency of Higher Education Admissions. Melbourne, Australia: Australian Government.

- Tremblay, M‐L., J. Leppink, G. Leclerc, J.-J. Rethans, and D. H. J. M. Dolmans. 2019. “Simulation‐Based Education for Novices: Complex Learning Tasks Promote Reflective Practice.” Medical Education 53 (4): 380–389. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13748.

- Zeichner, K. M. 1994. “Research on Teacher Thinking and Different Views of Reflective Practice in Teaching and Teacher Education.” In Teachers’ Minds and Actions: Research on teachers’ Thinking and Practice, edited by I. Carlgren, G. Handal, and S. Vaage, 9–24. London: The Falmer Press.