ABSTRACT

Theory-informed practice has a long tradition within the profession of early childhood education in Australia and internationally. Aligned with longstanding policy and curriculum in Australia, the profession has seen a prominence of resources informed by biological, behaviourism/socio-behaviourist, social learning, psycho-genetic, cultural-historical, critical and poststructuralist theories. Despite the plethora of theories being supported within early childhood education and care, little research has been directed to determining if and how educators use theory to inform their play practices. This paper takes up the challenge by surveying 200 Australian early childhood educators about the theories that were most relevant to their practices and the models of play that informed their day-to-day work in centres. Higher qualified educators were informed most by cultural-historical theory whilst technically qualified educators were more guided by social learning theory. Playwork was the model of play found to be most familiar to all educators. However, the results also show a limited alignment between theories of learning and development and models of play, suggesting an interesting contradiction in understandings of educators that is worthy of further research.

Introduction

Research and economic modelling have overwhelmingly shown the impact of quality early experiences in early childhood on long-term outcomes for children and society (Heckman & Masterov, Citation2007). The resultant professionalisation of early childhood education and care has also been informed by a series of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) policy reports (e.g. OECD, Citation2001) and ongoing research on continuous quality improvement (Australian Government Department of Education [AGDE], Citation2022).

Increased attention on evidence-informed practice has been mirrored by localised reforms (e.g. Victorian State Government, Citation2023) and the development of supporting resources (e.g. Victorian State Government, Citation2023). For example, in the first Australian Early Years Learning Framework (EYLF; Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations for the Council of Australian Governments [DEEWR], Citation2009) is presented a choice of child development theories, including biological, behaviourism/socio-behaviourist, social learning, psycho-genetic, cultural historical, critical and poststructuralist theories. But, little attention is given to models of play. However, the perceived gaps have been supported through resources and state-based curricula development. For instance, the Victorian Early Years Learning and Development Framework (VEYLDF) offers guidance to educators by including a triple helix model of play (guided play, adult-led, child-led) to support practice, possibly because of differing views on the degree of conceptual compatibility between play and learning (Bubikova-Moan et al., Citation2019). The second version of the EYLF (AGDE, Citation2022) offers little guidance on child development theory or models of play but provides detailed explanations on intentionality in play-based learning. Educators’ intentionality in play-based learning is defined as a teacher’s active role in supporting learning in children’s play, for instance, planning play both indoors and outdoors to bring children’s active engagement, agency, problem-solving, curiosity, creativity, and exploration (AGDE, Citation2022). But ongoing research shows that there are challenges faced by educators in Australia (Colliver, Citation2022; Thomas et al., Citation2011) and elsewhere (Grieshaber et al., Citation2021) into how to be intentional in play-based learning (AGDE, Citation2022). Intentional teaching with its international providence of sustained shared thinking (Siraj et al., Citation2022) has been most influential in Australia.

Although child development theories and models of play abound in the literature (Salamon et al., Citation2014), we appear to know little about the beliefs of early childhood educators, even though knowledge of child development and how it informs play-based programmes are viewed as the cornerstones of quality practice in early childhood education (OECD, Citation2001; Wood, Citation2020), and where the theory of child development held by the educator directly informs their observations of if and how a child’s play develops (AGDE, Citation2022; Fleer, Citation2021). For example, if a biological theory of child development is held, the educator would expect play to follow a set of predetermined milestones (infants explore objects, preschoolers engage in imaginary play). In contrast, a cultural-historical theory of child development would determine play as developing as a relation between the child and their social and material environment (Vygotsky, Citation1998). We suggest that the alignment between theories of child development and models of play that were originally cemented in biological child study research and practice (McCoy, Citation2022) may have become lost as more theories and models have emerged in the literature in recent times (O’Sullivan & Ring, Citation2021). Additionally, the field of early childhood education has expanded with a plethora of differently qualified staff as private and not-for-profit centres have become established across Australia (AGDE, Citation2022). Therefore, we expect that early childhood educators may well hold different beliefs of theories and models of play to support practices which may or may not be aligned and hypothesise that these could be based on the differing levels of their educational qualifications (technical certificates and diplomas, university degrees).

To examine this hypothesis, we designed a study to investigate educators’ beliefs about what theory of child development informed them and what model of play they used in their practice. From a selection of child development theories that were presented in the first version of the curriculum (DEEWR, Citation2009) and models of play that were identified by Early Childhood Australia (professional association of educators) in focus groups across Australia as widely discussed in the profession (risky play, Playwork, Conceptual PlayWorld), educators were asked how each model and theory was relevant to their current practice. Despite curricula and resourcing available in Australia on theories of child development and play models, the current study shows a contradiction between theory and models of play practice used by educators to inform their work. We suggest that knowing about educator beliefs about how theory of child development and models of play inform practice is an important baseline in the roll-out of the second version of the curriculum where limited detail on child development theories are provided (AGDE, Citation2022). But also, a lack of theoretical alignment is worrying for a professional field experiencing reform. This could be explained as an outcome of professional knowledge and new practices of intentionality being in constant flux, as the profession is expected to become more evidence-based as stated in the curriculum: ‘They critically reflect on their own views and understandings of theories, worldviews, evidence-based research, and practice’ (AGDE, Citation2022, p. 26). Therefore, the results of our study could nuance professional development and better support educators at a time of curriculum change.

We begin this paper with a review of what is known about teacher beliefs about theory, philosophy, and practice. Because this literature base is limited, we specifically reviewed studies of teacher beliefs and practices associated with intentional teaching because this can act as an indicator of beliefs about theories (Grieshaber et al., Citation2021) that we suggest are also associated with models of play being enacted in practice. We then introduce the details of the study, the results, discussion, and conclusion.

In our study, we define teacher beliefs as a broad concept which can be described as educators’ suppositions and understandings that guide their teaching decisions and actions. These may include beliefs about their professional and instructional practices, learning processes, interactions with students, and collaborations with their peers, among others (AGDE, Citation2022). In this paper, a model of play is conceptualised as a set of pedagogical characteristics defined through teacher beliefs about how children develop, and this model guides how teachers plan their play-based programme (Fleer, Citation2021).

Teacher beliefs about teaching, play and learning

It was not easy to find studies explicitly on teacher beliefs about theories of child development and models of play. Therefore, we looked closely at what is known about teacher beliefs after a period of reform, because new curriculum and quality improvement guidelines bring challenges and make conscious underlying beliefs about theory and practice (Colliver, Citation2022). Due to reforms in early childhood education associated with quality improvement through the introduction of intentional teaching into the EYLF in Australia (DEEWR, Citation2009), we were able to identify studies investigating teacher beliefs associated with play and learning that are relevant to the context of this paper. We examined the literature on teacher beliefs and practices associated with intentional teaching in play-based settings and found teachers struggled with the practice of how to bring into play the teaching of concepts detailed in curriculum guidelines and frameworks. A set of three struggles were identified.

First, many of the studies into intentional teaching showed positive outcomes for children in different discipline areas, such as mathematics (Thomas et al., Citation2011; Yang et al., Citation2022) and more broadly, such as Executive Functions (Banse et al., Citation2021; Fleer et al., Citation2020) or symbolic objects (Maita et al., Citation2014). But this research also identified pre-conditions in knowledge and interactional practices of teachers needed for intentional teaching. It was suggested that intentionality in play-based learning related to child outcomes was associated with:

focusing more on teacher participation in play-based practices where concepts can aid children’s play (Fleer et al., Citation2020);

teacher talk that is rich with the language of concepts (Thomas et al., Citation2011);

interactions that are oriented to intentional interaction of sustained shared thinking of different concepts/skills in contexts that build early knowledge (Yang et al., Citation2022);

teacher subject knowledge (Wu & Goff, Citation2021); and

teacher theoretical knowledge impacting on how learning was understood, measured and articulated (Grieshaber et al., Citation2021).

Second, we identified that teachers found it difficult to reconcile the focus on following children’s interests and intentionally teaching concepts from the curriculum (Lewis et al., Citation2019). It was noted in a single case study of two teachers focused on intentionally teaching over five weeks that a strong discord in beliefs and intentionality was evident. Even though the teachers understood the conceptual outcomes detailed in the curriculum, they experienced role confusion. That is, teachers’ philosophy of a child-centred approach to programming which involved following children’s interests, a focus on the child’s voice, and planning based on children’s intentions only, were central to their beliefs. Teachers could not reposition themselves from following children’s interests to leading and introducing new content to children. They expressed beliefs about traditional Piagetian practices to follow and match curriculum needs to children’s existing development, whilst trying to reconcile being more active in their role as a teacher of content. Past beliefs about child development theory were a strong pull, generating a contradiction as teachers engaged with the new expectations and practice principles for more intentional teaching. This finding is consistent with a review of the literature by Grieshaber et al. (Citation2021) who suggested that teachers had difficulties with reconciling intentional teaching and child-led learning through play.

Third, we also noted that whilst many studies reported that teachers positively support the concept of learning through play (Bubikova-Moan et al., Citation2019), an ethnographic study of five educators’ beliefs and practices associated with learning through play by Colliver (Citation2022) identified that educators attributed learning from play associated with teachers’ passive rather than active practices. That is, teachers considered that the children can learn the content of the curriculum by themselves. Analyses of practices suggest that the learning was more coincidental rather than intentional by the educators. Consistent with Lewis et al. (Citation2019), Colliver (Citation2022) concluded that the teachers were torn between the demands of the curriculum for more adult-driven outcomes and a pedagogy of play. He noted that ‘educators were adept at justifying child-determined learning in relation to adult-determined curricula demands’, and that they lacked support in knowing ‘how to actively engage with and extend child-initiated play for learning’ (p. 182). Yet this finding sits within a context where, as Wallace and Hesterman (Citation2021) argue:

The importance of play-based learning (PBL) remains anchored deeply in contemporary Western Australian Early Childhood Education (WA ECE) philosophy (Hesterman & Targowska, Citation2019): it is studied extensively in ECE teacher education courses (Robinson et al., Citation2018); is embedded in the ACECQA (Citation2019) teacher accreditation requirements; and, is relevant to university teacher performance assessment – a requirement for graduation (Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership, Citation2017). Theoretically speaking, children learning through play is considered the cornerstone of Australian ECE. (Edwards, Citation2017, p. 7)

These findings are indicative of a more active role for the educator, which are thereby more oriented towards contemporary theories of child development, such as cultural-historical theory, critical theory, and social learning theory. But these findings of educator intentionality in play-based learning are not associated with child development theories that are biological or developmental. From our review, we concluded that, whilst intentional teaching in play-based programmes has been theorised (Edwards, Citation2017; McLaughlin et al., Citation2016) and studied (Grieshaber et al., Citation2021) as leading to quality improvement of practices (Thomas et al., Citation2011; Yang et al., Citation2022) and child outcomes (Yang et al., Citation2022), teacher beliefs framed in relation to teacher knowledge of theory (Grieshaber et al., Citation2021) and discipline content (Wu & Goff, Citation2021) appear to be critically important for determining if and how educators use theory to inform their play practices for the three- to five-year age group (Grieshaber et al., Citation2021). This appears to be reflective of the revision of the EYLF in Australia where more detail on intentionality in play-based learning is given. However, with less guidance given on theories of child development and models of play, the new curriculum could leave the field vulnerable in moving forward. Whilst there are many factors that contribute to teacher beliefs, the early childhood profession has traditionally been strongly grounded in a belief that knowledge of child development and play pedagogy are the cornerstone of their practice (OECD, Citation2001). The relations between play and intentionality in play-based learning (AGDE, Citation2022) and intentional teaching (DEEWR, Citation2009) may have disrupted beliefs and practices (Grieshaber et al., Citation2021). Therefore, we suggest that knowing about the beliefs and practices of educators in Australia in relation to child development theories and well-known models of play is important for supporting the field as they transition into being more intentional in play-based learning.

The present study

This study aims to understand educators’ beliefs about what theory of child development informed them and what model of play they used in their practice in the context of directions given in the EYLF since 2009 in Australia. As foundational to early childhood education, we were particularly interested to know what contributing factors, such as teacher qualifications, could impact on their beliefs about child development in relation to their selection of play models.

Methods

Participants and procedure

We secured human ethics approval from our institution before data collection. Invitations to participate in the survey were distributed through social media channels and e-newsletter. Data were collected using an online survey platform during June–September 2022. The online survey took about 5–10 minutes to complete (see Appendix).

The study sample consisted of 200 early childhood educators across Australian states and territories. Approximately one third (n = 64, 32.0%) were located in New South Wales, 61 (30.5%) in Victoria, 21 (10.5%) in Queensland, 18 (9.0%) in the Australian Capital Territory, 17 (8.5%) in Western Australia, 15 (7.5%) in South Australia, two participants in Tasmania, one participant in Northern Territory, and one participant did not indicate their work location.

Nearly half (n = 85, 42.5%) worked as teachers/educators, 57 (28.5%) held director/manager/principal roles, 41 (20.5%) worked in other early childhood settings (e.g. consultants, lecturers, educational leaders), and 17 (8.5%) were room/team leaders. Most participants teach three-, four-, and five-year-old children (46.5%, 61.5%, and 43.0%, respectively; see ).

Table 1. Distribution of participants across teaching experience (N = 200).

In Australia, all educators working in children’s education and care services must have at least one of the following qualifications: an early childhood teaching qualification from university, a diploma, or a Certificate III qualification from a Technical and Further Education (TAFE) institution (AGDE, Citation2022). Response options for educational qualifications in the survey consist of a TAFE certificate, TAFE diploma, bachelor’s degree, graduate diploma, Master of teaching, Master of education, doctoral degree in education, and other post-secondary degrees. Half of the participants in this study (n = 102, 51.0%) were bachelor and graduate diploma graduates, 51 (25.5%) had completed TAFE certificates and diplomas, and 47 (23.5%) had completed Masters or doctoral degrees. In terms of their work settings, more than one third (n = 73, 36.5%) worked in long day care, 42 (21.0%) taught in kindergarten, 32 (16.0%) worked in pre-school, 31 (15.5%) worked in other settings (e.g. library, children’s hospital); other participants worked in family day care (n = 9, 4.5%), primary school (n = 7, 3.5%), preparatory year of full-time schooling (prep) to year 6 (n = 5, 2.5%), and one participant worked in an Outside School Hours Care (OSHC). Participants’ teaching experiences varied between six months and 40 years (M = 18 years; ).

Measures

There are three sections in the survey. The first section consists of six demographic questions (participants’ role, age group they currently teach, level of educational qualification, workplace settings, years of teaching experience, and work location as indicated by postcode). The second section comprises 10 closed-ended questions on models and theories and play. The subsequent section includes four open-ended questions investigating participants’ views on key benefits of play for children, challenges they face in planning and implementing play, their role and involvement in children’s play. They were also asked to indicate whether they had completed professional development on play. These findings are discussed elsewhere.

This paper focuses on findings from section two where participants were presented with a collection of models and theories of play; they were then invited to reflect on how each model and theory was relevant to their current practice. Response options were provided in a Likert scale ranging from (1) not at all like me to (7) very much like me.

The survey questions about child development and play were developed based on the Self-assessment of play beliefs and practices (Fleer, Citation2021) and closely aligned with the child development theories listed in the EYLF (DEEWR, Citation2009). We included three models of play in the survey: Playwork (Play Scotland, Citation2023), Conceptual PlayWorld (Fleer, Citation2023) and risky play (Sandseter, Citation2010). These models were selected because they were identified in previous focus groups to be the most prevalent models of play (Playwork, risky play)Footnote1 as well as a contrasting model of play less well known, but based solely on a cultural-historical theory of play (Conceptual PlayWorld). We were unable to find other evidence-informed cultural-historical models of play to reference in the survey.

Risky play is defined as being a part of children’s natural ways of playing, where they are motivated and excited to be taking risks associated with physical injury (Sandseter, Citation2010). It is suggested that in risky play children are able to test their own limits as they climb trees, use dangerous tools, for instance, and in so doing explore boundaries and learn about injury risk. In this model of play, the educator’s role ‘is to ensure that children have opportunities to enjoy all the benefits of risky play, but without any serious injuries taking place’ (Care for Kids, Citation2022, para. 10). Therefore, we suggest that risky play is based on a developmental theory of child development. A developmental perspective means that educators follow a set of expected milestones related to the age of the child, such as toddlers are walking, preschoolers can run. By understanding the developmental trajectory, risks can be provided based on the age of the child and their expected capacity.

Playwork as a model of play is detailed by Play Scotland on their website (https://www.playscotland.org/get-involved/playwork-professionals/information-on-playwork/). Play Scotland states that what underpins this model is that the impulse to play is innate and this suggests it is biologically determined. This positions educators as supporters of children’s intentions in play and as the vehicle through which children ‘naturally learn and develop’. This is noted on their website:

Playwork is an approach to working with children in which children determine and control the content and intent of their play, rather than it being led or directed. The play process for children includes exploration, trying out things, testing boundaries of ability as they grow, learning from successes and mistakes to build resilience and adaptability. Playwork is a service delivered by adults for children, either through people, places or a combination of both.

Therefore, this model of play has its foundations in developmental theory. That is, expectations of natural development by the child are directly related to age-related milestones in children’s development.

Conceptual PlayWorld builds on a cultural-historical model of play called playworlds (Lindqvist, Citation1995) where children and teachers encounter the drama of a story that they imagine and live through role-playing the story. In a Conceptual PlayWorld, the practices are more oriented to bringing concepts into children’s play. Like Lindqvist (Citation1995), Conceptual PlayWorld begins with a narrative from a storybook, where children and their teachers go on adventures by imagining they are characters in the story. Closely aligned with intentionality in play-based learning (AGDE, Citation2022), in a Conceptual PlayWorld children meet problems that need concepts to solve them so that the play can continue. Educators are play partners and plan their interactions. In this cultural-historical model of play, concepts act in service of children’s play. A cultural-historical theory of child development is conceptualised as a unity between the child and their social and material environment. Play acts as the source of the child’s development where there is an active role for the educator to plan interactions and conditions to be above a child’s current development. Educators support mature play conditions that develop the psychological function of imagination. In these imaginary situations, children’s visual field (they see a stick) is imagined as something else (as a horse), giving new conditions for children’s actions (child becomes a rider).

The child development theories we referenced in our survey were the ones presented in EYLF (DEEWR, Citation2009). In the survey, participants were provided with an explanatory audio recording for each theory, where one of the researchers read the vignette, along with a link to a relevant reading. The vignettes were prepared and tested in Australia with early childhood leaders, policymakers, and educators as part of a series of five-day professional development sessions on child development theories in curriculum (DEEWR, Citation2009) and well-known play models (Fleer, Citation2021). The theories of child development include biological (e.g. Gesell, Citation1925), behaviorism/socio-behaviourist (e.g. Skinner, Citation1957), social learning (e.g. Bandura, Citation1986), psycho-genetic (e.g. Piaget, Citation1950, Citation1952), cultural-historical (e.g. Vygotsky, Citation1998; or Rogoff, Citation2003), Critical and poststructuralist theories (e.g. Blaise, Citation2005).

Analysis

We removed incomplete responses in the dataset and only complete responses were retained for further analysis. Participant responses on closed-ended questions were analysed using SPSS. Participants’ beliefs of the model of play and theory of child development were compared based on their role (i.e. director/manager/principal, room/team leader, and teacher/educator) and educational qualification (i.e. TAFE certificate and diploma, Bachelor and graduate diploma, Masters and doctoral). Descriptive statistics including means were presented in the next section. Pearson Product-Moment Correlation was performed to examine the relationships between models and theories selected by participants (Pallant, Citation2020).

Results

We were interested to know about educators’ beliefs surrounding the theory of child development that informed them and what model of play they used in their practice. We present the responses to the surveys by bringing together early childhood educators’ views on both, as well as how, if at all, their views are theoretically aligned. We expected that educators who adopt a particular view of child development would also draw on a model of play that was conceptualised from that particular theoretical stance. We also looked closely at beliefs in relation to teacher qualifications, as we expected that qualifications would act as a proxy for knowledge about pedagogy, play models and theories. The results of our survey are presented in three key sections: (1) models of play; (2) theories of child development; and (3) correlation between models of play and theories of child development.

Models of play

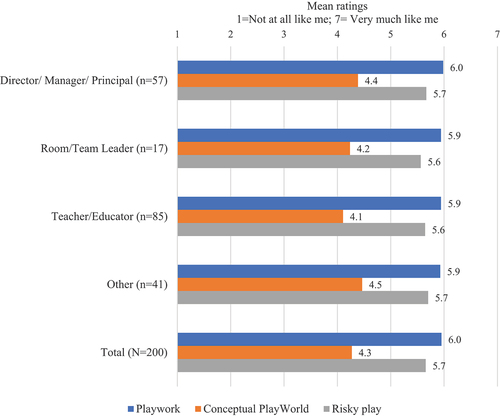

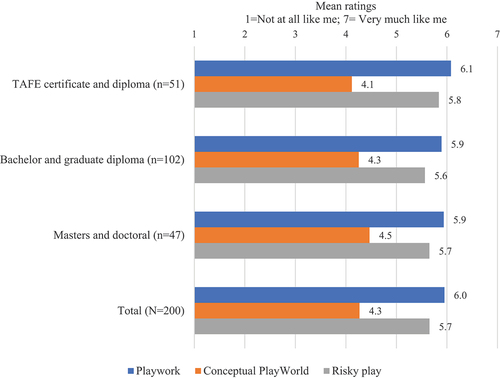

Participants were asked to indicate the extent to which the presented models of play were relevant to their current practices. In general, from 1 (not at all like me) to 7 (very much like me), participants perceived that the Playwork model was the most relevant to their current practice (M = 6.0) followed by the risky play model (M = 5.7) and Conceptual PlayWorld model (M = 4.3).

Similarly, this trend was also found when the participants were broken down into their respective roles () and educational qualifications (). The Playwork model was the most relevant to all participants’ current practice regardless of their roles and educational background, followed by risky play and Conceptual PlayWorld models.

Theories of child development

We asked participants to indicate the extent to which the presented child development theories were relevant to their current practices, from 1 (not at all like me) to 7 (very much like me) and then we examined the qualification of each respondent.

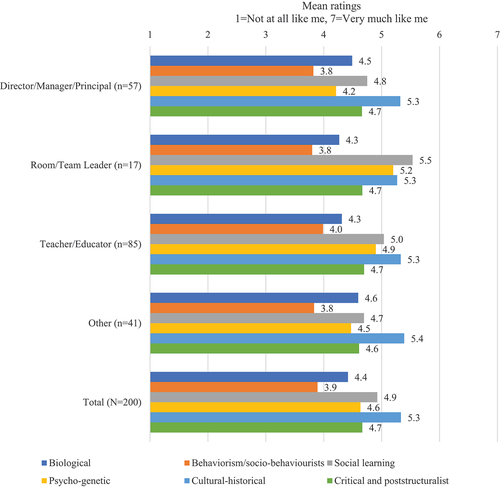

Theory relevance for informing practices by current role

In general, we found that participants perceived their practices to be most connected with cultural-historical theory (M = 5.3). An exception is room/team leaders who related the most with social learning theory than other theories of child development. The second relevant theory among participants was social learning theory, followed by psycho-genetic, critical and poststructuralist and biological or developmental theories. Participants were least connected with behaviourism/socio- behaviourist theories ().

Theory relevance for informing practices by qualification

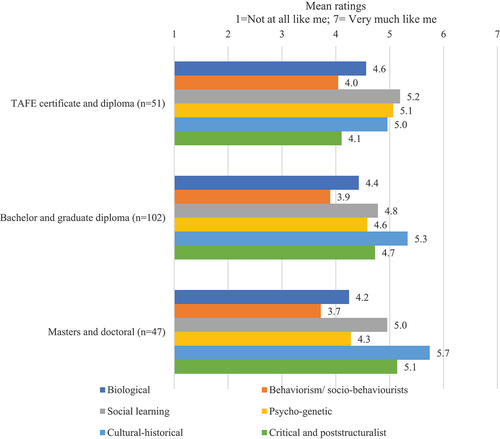

We were interested to know if participants’ qualifications made any difference to their rating of the relevance of the child development theory. shows the results of the relevance of the child development theory in relation to the role the participants held in the centre, and shows the participants’ level of education/qualifications in relation to their beliefs about the relevance of the child development theories.

Figure 4. Mean ratings for most relevant theory of child development by participants’ educational qualification.

We found that participants with TAFE qualifications were more informed by social learning (M = 5.2), psycho-genetic (M = 5.1), and cultural historical theories (M = 5.0), than biological (M = 4.6), critical and poststructuralist (M = 4.1), and behaviourism/socio-behaviourist theories (M = 4.0). Participants with a bachelor and graduate diploma, as well as Masters and doctoral qualifications perceived cultural-historical theory as the most relevant theory to their practices (M = 5.3 and M = 5.7 respectively) than other theories. The next relevant theory for bachelor and graduate diploma participants was social learning theory (M = 4.8) followed by critical and poststructuralist (M = 4.7). This was slightly different for Masters and doctoral participants, with the second relevant theory being critical and poststructuralist (M = 5.1), followed by social learning theory (M = 5.0). For the remaining theories, similar patterns were found for participants with bachelor, graduate diploma, Masters and doctoral qualifications: psycho-genetic (M = 4.6 and M = 4.3), biological (M = 4.4 and M = 4.2), and behaviourism/socio-behaviourist (M = 3.9 and M = 3.7).

Correlation between models of play and theories of child development

To investigate the discrepancy between models of play and the lack of alignment with child development theories, we conducted a correlation analysis between the participants’ beliefs about the relevance of the models of play and the child development theories (see ).

Table 2. Correlation between models of play and theories of child development.

Pearson correlation coefficients were computed to assess linear relationships between models of play and theories of child development. There were significant weak positive correlations between Playwork model and biological theory, r (187) = .180, p = .013; Playwork model and social learning theory, r (184) = .165, p = .025; Playwork model and psycho-genetic theory, r (184) = .194, p = .008; as well as Playwork model and critical and poststructuralist theories, r (184) = .223, p = .002. Participants whose practices were informed by the Playwork model were more likely to perceive biological, social learning, psycho-genetic and critical and poststructuralist theories as relevant to their practice.

There were significant weak positive correlations between Conceptual PlayWorld model and biological theory, r (187) = .269, p < .001; Conceptual PlayWorld model and behaviourism/socio-behaviourist theory, r (184) = .247, p < .001; Conceptual PlayWorld model and cultural-historical theory, r (184) = .250, p < .001; as well as Conceptual PlayWorld model and critical and poststructuralist theories, r (184) = .278, p < .001. This can be interpreted that participants who perceived the Conceptual PlayWorld model as relevant to their practice tended to relate more to biological, behaviourism/socio-behaviourist, cultural-historical, and critical and poststructuralist theories in their current practice.

There were significant weak positive correlations between risky play model and social learning theory, r (184) = .171, p = .002; risky play model and cultural-historical theory, r (184) = .169, p = .021; risky play model and critical and poststructuralist theories, r (184) = .271, p < .001. Participants who chose the risky play model as relevant to their practice tended to relate more to social learning, cultural historical and critical and poststructuralist theories.

A limitation of the survey design was the pre-determined categories of theories of child development and models of play. However, those child development theories selected were in keeping with EYLF (DEEWR, Citation2009) and the models of play were theoretically diverse to give maximum scope for strength of belief. There could be other models of play and theories of child development that participants could have considered as relevant in their practice but which they were unable to report.

Discussion

We studied early childhood educators’ beliefs of theories and models of play to support practices to find out if they aligned. We hypothesised that alignment could be associated with the differing levels of educational qualifications (technical certificates and diplomas, university degrees). Although the Early Years Learning Framework in Australia (AGDE, Citation2022) provides principles, practices, and expected learning outcomes, we anticipated that early childhood educators’ beliefs are influenced by the materials (including theories and models of play) they learn when they complete their early childhood qualification/education.

We found that first, the clustering of responses around cultural-historical theory to be the most relevant theory of child development for degree qualifications and above. Master degree qualified participants of the survey had the highest scores for cultural-historical theory. Technically educated respondents did not select this theory of child development as the most relevant for them. It was third in their selection for relevance to their practice. Technically educated respondents found social learning theory to be the most relevant for them.

Regardless of the reasons for the educators’ qualifications impacting on their perceptions of the relevance of the theory of child development, the difference found among the respondents is an interesting finding and has not been previously reported in the literature. Closest is a study undertaken two years before the release of the EYLF, where university students were expanding their repertoire of child development theories to include cultural-historical theory. In that study of 40 final-year university students enrolled in a four-year Bachelor of Education Childhood Education degree, the researchers identified that student teachers experienced discontinuity between their newfound knowledge of cultural-historical theory, and what was being supported within the field – constructivist-developmental theories (biological) of child development (Fleer & Robbins, Citation2007). Similarly, Edwards (Citation2006) studied beliefs and practices related to theories of child development but focused on teachers and assistant teachers and noted a four-phase transitioning into understandings of cultural-historical theory. The teachers initially conceptualised cultural-historical theory as multiculturalism. This changed in the second phase to a belief that the theory foregrounded cultural differences in relation to Western culture. In the third phase, the teachers considered cultural-historical theory in relation to developmental context, and finally, they thought it was a ‘predominately developmental approach to recognizing value in understanding the sociocultural dimensions of development’ (Edwards, Citation2006, p. 244). What these studies show is that cultural-historical theory of child development at the university level and in the field context requires a transition. Further, Salamon et al. (Citation2014) suggested that beliefs and practices can be traced back to ‘implicit theories and “naïve” beliefs of ECEs [early childhood educators] arising from past experiences, personal values and common sense’ (p. 1). They suggest that with educational reform, such as that seen through the introduction of the EYLF in 2009 where a broader set of child development theories were presented, requires early childhood educators to increasingly ‘articulate their professional knowledge and expertise’ (p. 10).

In hypothesising that differing levels of educational qualifications impact on educator perceptions about the relevance of child development theory, the patterns noted in our study, where the responses clustered around cultural-historical child development theory for university-educated and social learning theory for technically qualified educators, suggest that the clustering gives confidence that educators can positively respond to the demands of discussing the theory of child development. The pattern of theories related to educational qualifications suggests they are indeed associated with the training received.

This result could suggest that there is less coverage of cultural-historical theories in the technical courses or it could be that this theory is less well understood in relation to how it supports educator practices of observing and planning for children’s development. Cultural-historical theory has a shorter history for informing early childhood practice than social learning theory and is much more complex and challenging to understand. However, it could also be tied to the length of the courses, where degree qualifications take a minimum of four years, and technical courses are from one to three years. Shorter courses may not have enough time to fully explore a cultural-historical theory of child development for informing educator practices.

Second, whilst we expected that early childhood educators who hold different beliefs of theories and models of play to support practices could be different, we thought that the theories of child development and models of play would be aligned. However, what we found was that when the responses to theory of child development were correlated with the most relevant model of play, we identified a surprising contradiction for university-qualified teachers, but not so for technically qualified educators.

The university degree-qualified teachers who identified with cultural-historical theory of child development as being the most relevant for informing their practice also selected Playwork as the most relevant model of play. As shared on the official home of Playwork, Play Scotland advocates on its website for a more biological developmental perspective on play as ‘The impulse to play is innate’ (Play Scotland, Citation2023). This is suggestive of a developmental view of play and not a cultural-historical view where the latter has at its core adults who are more actively and socially engaged in children’s play. Therefore, it was surprising that these same participants thought that a biological developmental view of child development was least relevant for them. This shows a lack of alignment between models of play and child development theory for this particular group. We wondered why. We think that whilst there is now more knowledge of cultural-historical theory of child development specific for early childhood education, there is a limited number of evidence-informed models of play. Only one evidence-informed model of play that has been researched empirically and which draws on cultural-historical theory is available to the sector. Whilst this model is known through professional development, it may not be as well- known as Playwork. Another reason might be that child development theories are explicitly discussed in courses, whereas models of play may not be discussed in such an explicit way. It is also possible that those who have undertaken recent higher-level qualifications may well have shifted towards cultural-historical theories, but may not have yet looked closely at the principles underpinning Playwork, and therefore may not have noted any mismatch.

Although we did find some theoretical alignment with the Conceptual PlayWorld model of play and cultural-historical theory in general, we also found significant weak positive correlations between the Conceptual PlayWorld model and biological theory; Conceptual PlayWorld model and behaviourism/socio-behaviourist theory; as well as Conceptual PlayWorld model and critical and poststructuralist theories. This overall finding is suggestive that there was some confusion, and we think this could be related to the complexity of cultural-historical theory generally (Fleer & Robbins, Citation2007). But also, we know that research has shown that there is a need to transition into how this theory informs practices (Edwards, Citation2006), where there is a lack of play models specifically tied to cultural-historical theory.

In contrast to the university-qualified teachers, we did find an alignment in models of play and child development theory most relevant for practice for the technically qualified respondents to the survey. For instance, a significant weak positive correlation between the Playwork model and biological theory was found. Playwork has its foundations in a biological developmental theory of child development and therefore selecting this theory and corresponding model of play shows a complete alignment for technically qualified respondents.

But surprisingly, we also found that those technically qualified participants who chose the risky play model as relevant to their practice tended to relate more to social learning, cultural-historical and critical and poststructuralist theories. That is, risky play appeared to relate more to contemporary theories of child development, rather than biological and developmental theories of child development which has been questioned for its relevance over the past 20 years (see Wood, Citation2020 for a deep analysis of EYFS in England). This result shows a lack of alignment and therefore suggests that the participants did not understand the model of play, or they were unsure about theories of child development in relation to their chosen models of play.

Overall, despite the findings from our study not showing theoretical alignment between the theories of child development and models of play primarily for the degree qualified respondents, and a subset of technically qualified respondents who chose contemporary theories aligned with risky play, the results do suggest some development of the field from when developmental theories dominated the discourse of the early childhood profession (Fleer & Robbins, Citation2007). In line with Edwards (Citation2006) and Fleer and Robbins (Citation2007), we think our findings show how challenging it is for a profession to make a step-change from earlier and outdated theories and models (Wood, Citation2020) to more contemporary and evidence-informed practices that align child development with models of play. Play and child development as the cornerstones of early childhood education appear to still need to be supported. Therefore, we think that dropping from the second version of the curriculum details on a range of theories, and not including evidence-informed play models, may well have been premature.

Conclusion

The study reported in this paper examined the beliefs of educators about the relevance of child development theories and models of play for supporting and explaining their practices. The findings suggest that educators engaged with all of the theories of child development outlined in the EYLF, but contemporary theories appeared to be more relevant, with cultural-historical theory selected for university-educated respondents and social learning theories for technically qualified educators. Interestingly, a general lack of alignment between theories and models was also identified for the university-qualified group, suggesting that, whilst the profession is engaged more with contemporary theories, understandings are still developing. However, technically qualified staff were more likely to align with models of play that are based on developmental theories, although these theories have consistently been criticised in the literature (McCoy, Citation2022; Salamon et al., Citation2014). We suggest the models of play found most relevant for the technically qualified staff limit the role of the educator to observer of children and provider of resources, thereby making it difficult to take a more active role and act intentionally in play-based learning as foregrounded in the revised EYLF (AGDE, Citation2022). Practices described in the EYLF that show being intentional in play-based learning, such as ‘extend children’s learning using intentional teaching strategies’ (p. 22) will sit uncomfortably with educators who find biological developmental theories of child development most relevant for informing their practice, whilst educators who draw on cultural-historical theories are less likely to struggle with taking a more active role. However, the lack of alignment between models and theories in this particular group suggests that more knowledge of evidence-informed models of play that draw on cultural-historical theory, for instance, the Conceptual PlayWorld model, are needed if the sector is to plan and implement programmes that support the educator to be more intentional in play-based learning. More research is needed into educators’ beliefs about play, and how they perceive their role in children’s play. Speaking from an international perspective, O’Sullivan and Ring (Citation2021) remind us, ‘Now, more than ever, we have a collective responsibility to clearly articulate the philosophical and research base that should propel high-quality early childhood education’ (p. 13).

These results are based on a sample of 200 Australian teachers/educators, who responded to a specific set of categories of theories and models. A larger sample and more opportunities for the selection of play models may well reveal different correlations. Ongoing research into how educators and teachers draw on evidence-based models of play, with more time for transitioning from longstanding biological to more contemporary cultural-historical theories of child development is still needed. A study of alignment between theory and models in relation to qualifications may well reveal different findings in the future as the sector uses the new version of the early childhood curriculum with concepts of intentionality and play-based learning. How technically qualified educators can be more intentional, when the theories of child development they draw upon position them as not taking an active intentional teaching role, is yet to be determined. Importantly, the level of confusion between child development theories and models of play found in our current study is suggestive of a need for ongoing professional development to support educators in a context of ongoing reforms (Victorian State Government, Citation2023) and a revised curriculum (AGDE, ,Citation2022) in Australia.

Ethics approval

Monash University Project Number 19778: STEM concept formation in homes and playbased settings.

Acknowledgements

Through Early Childhood Australia, the main professional association that supports educators and teachers, and the Australian Research Council Laureate Fellowship Scheme (FL180100161), we were able to prepare the survey and analysis associated with teachers’ view of play in Australia. Special mention is made of Dr Kate Highfield, Dr Dan Leach-McGill and Early Childhood Australia for contributing to survey questions and recruitment of participants. Additionally, Yuwen Ma and Yuejiu Wang, who supported the process of identifying the literature base for the problem examined in this paper, are acknowledged.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

Data not available due to ethics restrictions.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Anne Suryani

Anne Suryani is a Senior Research Fellow in the Faculty of Education, Monash University, Australia. She has extensive experience working in a range of government-funded, consultancy and grant-based educational research in the Asia-Pacific Region, including on teacher motivation, teacher education, teacher professional development, and educational policy.

Marilyn Fleer

Marilyn Fleer holds the Foundation Chair of Early Childhood Education and Development at Monash University, Australia. She was awarded the 2018 Kathleen Fitzpatrick Laureate Fellowship by the Australian Research Council and was a former President of the International Society of Cultural-historical Activity Research (ISCAR).

Notes

1. Early Childhood Australia (ECA) conducted a focus group discussion for Year of Play in 2021–2022 and found that these two models are the most discussed as the primary models.

References

- Australian Children’s Education & Care Quality Authority (ACECQA). (2019). Early childhood teaching qualifications.

- Australian Government Department of Education (AGDE). (2022). Belonging, being and becoming: The early years learning framework for Australia (V2.0). Australian Government Department for the Ministerial Council. https://www.acecqa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-01/EYLF-2022-V2.0.pdf

- Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership. (2017). Australian professional standards for teachers. Retrieved February 12, 2023, from https://www.aitsl.edu.au/teach/standards

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social formation of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prenteice-Hall.

- Banse, H. W., Clements, D. H., Sarama, J., Day-Hess, C., Simoni, M., & Joswick, C. (2021). Intentional teaching moments. YC Young Children, 76(3), 75–82.

- Blaise, M. (2005). Playing it straight: Uncovering gender discourses in early childhood classrooms. Routledge.

- Bubikova-Moan, J., Næss Hjetland, H., & Wollscheid, S. (2019). ECE teachers’ views on play-based learning: A systematic review. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 27(6), 776–800. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2019.1678717

- Care for Kids. (2022). Why risky play is important for young children. Retrieved February 9, 2023, from https://www.careforkids.com.au/child-care-provider-articles/article/189/why-risky-play-is-important-for-young-children

- Colliver, Y. (2022). Intentional or incidental? Learning through play according to Australian educators’ perspectives. Early Years, 42(2), 182–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2019.1661976

- Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations for the Council of Australian Governments (DEEWR). (2009). Belonging, being & becoming: The early years learning framework for Australia. Commonwealth of Australia. https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://www.acecqa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2018-02/belonging_being_and_becoming_the_early_years_learning_framework_for_australia.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwiIvfHDr7WFAxUuTEEAHZa3CgcQFnoECBUQAQ&usg=AOvVaw12V4CxFYMldavy2GqyEz36

- Edwards, S. (2006). ‘Stop thinking of culture as geography’: Early childhood educators’ conception of sociocultural theory as an informant to curriculum. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 7(1), 138–252. https://doi.org/10.2304/ciec.2006.7.3.238

- Edwards, S. (2017). Play-based learning and intentional teaching: Forever different? Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 42(2), 4–11. https://doi.org/10.23965/AJEC.42.2.01

- Fleer, M. (2021). Play in the early years (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Fleer, M. (2023). Conceptual PlayWorlds. Monash University Working Papers. https://www.monash.edu/education/research/projects/conceptual-playlab/publications

- Fleer, M., & Robbins, J. (2007). A cultural-historical analysis of early childhood education: How do teachers appropriate new cultural tools? European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 15(1), 103–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/13502930601161890

- Fleer, M., Walker, S., White, A., Veresov, N., & Duhn, I. (2020). Playworlds as an evidenced-based model of practice for the intentional teaching of executive functions. Early Years, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2020.1835830

- Gesell, A. (1925). The mental growth of the preschool child. Mcmillan.

- Grieshaber, S., Krieg, S., McArdle, F., & Sumsion, J. (2021). Intentional teaching in early childhood education: A scoping review. Review of Education, 9(3). https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3309

- Heckman, J. J., & Masterov, D. V. (2007). The productivity argument for investing in young children ( Discussion Paper 2725). Institute for Labour Study.

- Hesterman, S., & Targowska, A. (2019). The status-quo of play-based pedagogies in Western Australia: Reflections of early childhood education practitioners. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 45(1), 30–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/1836939119885305

- Lewis, R., Fleer, M., & Hammer, M. (2019). Intentional teaching: Can early-childhood educators create the conditions for children’s conceptual development when following a child-centred programme? Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 44(1), 6–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/1836939119841470

- Lindqvist, G. (1995). The aesthetics of play: A didactic study of play and culture in preschools (Upsala Studies in Education 62). Gotab.

- Maita, M. D. R., Mareovich, F., & Peralta, O. (2014). Intentional teaching facilitates young children’s comprehension and use of a symbolic object. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 175(5), 401–415. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.2014.941320

- McCoy, D. C. (2022). Building a model of cultural universality with specificity for global early childhood development. Child Development Perspectives, 16(1), 27–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12438

- McLaughlin, T., Aspden, K., & Snyder, P. (2016). Intentional teaching as a pathway to equity in early childhood education: Participation, quality, and equity. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 51(2), 175–195. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40841-016-0062-z

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2001). Starting strong I: Early childhood education and care.

- O’Sullivan, L., & Ring, E. (2021). A potpourri of philosophical and child development research-based perspectives as a way forward for early childhood curricula and pedagogy: Reconcilable schism or irreconcilable severance? Early Child Development and Care, 191(7–8), 1316–1329. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2020.1871334

- Pallant, J. (2020). SPSS survival manual. Routledge.

- Piaget, J. (1950). Psychology of intelligence. Kegan Paul.

- Piaget, J. (1952). The child’s conception of number. Kegan Paul.

- Play Scotland. (2023). Playworks principles - An overview. Retrieved February 1, 2023, from https://www.playscotland.org/get-involved/playwork-professionals/information-on-playwork/

- Robinson, C., Treasure, T., O’Connor, D., Neylon, G., Harrison, C., & Wynne, S. (2018). Learning through play. Oxford University Press.

- Rogoff, B. (2003). The cultural nature of human development. Oxford University Press.

- Salamon, A., Sumsion, J., Press, F., & Harrison, L. (2014). Implicit theories and naïve beliefs: Using the theory of practice architectures to deconstruct the practices of early childhood educators. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476718X14563857

- Sandseter, E. (2010). Scaryfunny: A qualitative study of risky play among preschool children. Norwegian University of Science and Technology. Retrieved February 24, 2023, from https://ntnuopen.ntnu.no/ntnu-xmlui/handle/11250/270413

- Siraj, I., Melhuish, E., Howard, S., Neilsen-Hewett, C., Kingston, D., De Rosnay, M., Huang, R., Gardiner, J., & Luu, B. (2022). Improving quality of teaching and child development: A randomised controlled trial of the leadership for learning intervention in preschools. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1092284. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1092284

- Skinner, B. F. (1957). Verbal behaviour. Appleton Century-Croft.

- Thomas, L., Warren, E., & DeVries, E. (2011). Play-based learning and intentional teaching in early childhood contexts. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 36(4), 69–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/183693911103600410

- Victorian State Government. (2023). Victorian state government roadmap to reform. Retrieved February 10, 2023, from https://www.dffh.vic.gov.au/publications/roadmap-reform-strong-families-safe-children

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1998). The collected works of L.S. Vygotsky. “Child Psychology.” (R.W. Rieber, Ed.; M.J. Hall, Trans., Vol. 5). New York: Kluwer Academic & Plenum Publishers.

- Wallace, R., & Hesterman, S. (2021). The nexus of play-based learning and early childhood education: A Western Australian account. Education & Society, 39(1), 5–24. https://doi.org/10.7459/es/39.1.02

- Wood, E. (2020). Learning, development and the early childhood curriculum: A critical discourse analysis of the early years foundation stage in England. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 18(3), 321–336. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476718X20927726

- Wu, B., & Goff, W. (2021). Learning intentions: A missing link to intentional teaching? Towards an integrated pedagogical framework. Early Years, 43(2), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2021.1965099

- Yang, W., Luo, H., & Zeng, Y. (2022). A video-based approach to investigating intentional teaching of mathematics in Chinese kindergartens. Teaching and Teacher Education, 114, 103716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2022.103716

Appendix.

Survey questions on models of play